Abstract

Objectives:

Polypharmacy and frailty are two common geriatric conditions. In community-dwelling healthy older adults, we examined whether polypharmacy is associated with frailty and affects disability-free survival (DFS), assessed as a composite of death, dementia, or persistent physical disability.

Methods:

We included 19,114 participants (median age 74.0 years, IQR: 6.1 years) from ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) clinical trial. Frailty was assessed by a modified Fried phenotype and a deficit accumulation Frailty Index (FI). Polypharmacy was defined as concomitant use of five or more prescription medications. Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine the cross-sectional association between polypharmacy and frailty at base line, and Cox regression to determine the effect of polypharmacy and frailty on DFS over five years.

Results:

Individuals with polypharmacy (vs. <5 medications) were 55% more likely to be pre-frail (Relative Risk Ratio or RRR: 1.55; 95%Confidenee Interval or CI:1.44, 1.68) and three times more likely to be frail (RRR: 3.34; 95%CI:2.64, 4.22) according to Fried phenotype. Frailty alone was associated with double risk of the composite outcome (Hazard ratio or HR: 2.16; 95%CI: 1.56, 2.99), but frail individuals using polypharmacy had a four-fold risk (HR: 4.24; 95%CI: 3.28, 5.47). Effect sizes were larger when frailty was assessed using the FI.

Conclusion:

Polypharmacy was significantly associated with pre-frailty and frailty at baseline. Polypharmacy-exposed frailty increased the risk of reducing disability-free survival among older adults. Addressing polypharmacy in older people could ameliorate the impact of frailty on individuals’ functional status, cognition and survival.

Keywords: ASPREE, Disability-free survival, Frailty index, Fried phenotype, Polypharmacy

1. Introduction

Geriatric syndromes, such as polypharmacy and frailty, are common in older adults and are associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes (Mehta, Kochar, Kennelty, Ernst & Chan, 2021) and reduced function and quality of life (Inouye, Studenski, Tinetti & Kuchel, 2007). Polypharmacy, usually defined as taking five or more medications, often includes potentially inappropriate medication (Gnjidic et al., 2012; Halli-Tierney, Scarbrough & Carroll, 2019). Although polypharmacy can be appropriate for some chronic conditions (Poudel et al., 2016), it has been associated with increased length of hospital stay, readmissions, falls, functional impairment, dementia, frailty and mortality (Leelakanok & D’Cunha, 2019; Midão, Giardini, Menditto, Kardas & Costa, 2018). The frailty syndrome, as assessed by Fried phenotype (Fried et al., 2001), or a deficit accumulation approach (Rockwood et al., 2005a), identifies older adults at a high risk of adverse health outcomes (Cesari et al., 2016), including recurrent falls, fractures, hospitalizations, institutionalization, disability (Makizako, Shimada, Doi, Tsutsumimoto & Suzuki, 2015), dementia (Li et al., 2020) and mortality (Kojima, Iliffe & Walters, 2018).

Although polypharmacy and frailty overlap in vulnerable older adults, the extent to which polypharmacy modifies frail older persons’ healthy independent life span is not clear. Furthermore, previous research has focused on the risks of individual adverse endpoints with each syndrome. The ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) clinical trial first registered “disability-free survival” (DFS) on clinicaltrials.com as a primary outcome in 2009 (ClinicalTrials.gov, 2009). The ASPREE protocol was available on the www.aspree.org website from 2010 and the methods paper from 2013 (ASPREE Investigator Group, 2013). Later Myles and colleagues (Boney, Moonesinghe, Myles & Grocott, 2016; Shulman et al., 2015) described the concept of DFS for surgical and intensive care treatments. Disability-free survival (DFS), defined as survival free of physical disability and dementia, was the primary outcome measure of the ASPREE trial conducted in community-dwelling older adults who were free of documented cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, dementia or significant physical disability on enrollment (McNeil et al., 2018). In this post-hoc analysis of ASPREE participants, we explored the relationship between polypharmacy and frailty. Furthermore, we evaluated the risk of a reduction in healthy life-span or DFS in pre-frail and frail older people exposed to polypharmacy, using the Fried phenotype and a deficit accumulation frailty index to characterize frailty.

2. Methods

2.1. ASPREE participants

Full details regarding the sampling procedure and study design of the ASPREE clinical trial have been published previously (McNeil et al., 2017). In brief, the ASPREE trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled primary prevention trial of 100 mg of aspirin daily in a population of relatively healthy community-dwelling older people in the United States (US) and Australia with a median follow-up of 4.7 years. In Australia, 16,703 eligible individuals aged 70 years and older (median 74.1 years, interquartile range or IQR: 6.0 years) were recruited through primary care/general practices across five states and territories. In the US, 2,411 participants (median 73.0 years, interquartile range or IQR: 7.2 years) were recruited through academic and clinical trial centers and focused on recruiting a representative sample of ethnic minorities aged 65 years or older (McNeil et al., 2017). The main exclusion criteria in both countries were a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or atrial fibrillation, dementia or a score of less than 78 on the Modified Mini--Mental State examination (3MS), physical disability as defined by severe difficulty, inability to perform, or requiring assistance to perform, any one of basic activities of daily living (ADL), a condition with high current or recurrent risk of bleeding, anemia, a condition likely to cause death within five years, current use of other antiplatelet or antithrombotic medication, current use of aspirin for secondary prevention, and blood pressure ≥180/≥105 mm Hg (McNeil et al., 2017).

2.2. Operationalization of polypharmacy

Concomitant prescription medications (ConMeds) were collected at baseline and each annual visit of study follow-up. Participants were asked to bring their prescription medications to their annual face-to-face visits for ASPREE staff to cross-check and record or bring a prescription list. The generic name of the prescription medication was also confirmed by reviewing the participant’s medical record held by the primary care physician (general practitioner). Along with prescription medications, ASPREE also recorded any regular (i.e., more than once per week for more than four weeks) use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs). For the present analysis, we categorized the number of prescription medications used into two categories: no polypharmacy (0 to 4 medications) and polypharmacy (5 or more medications) as entered at baseline. This definition did not include food supplements, homeopathic medicine, or over-the-counter non-prescription medications. The details of medications prescribed to the participants, polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy in the ASPREE study, have been published (Lockery et al., 2020).

2.3. Assessment of frailty

Fried phenotype (proposed and validated by Fried and colleagues in the Cardiovascular Health Study) (Fried et al., 2001) and deficit accumulation Frailty Index (proposed and validated by Rockwood and colleagues in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging) (Rockwood et al., 2005a) represent the most known operational definitions of frailty in older persons. These two instruments are different but complementary (Cesari, Gambassi, Abelian Van Kan & Vellas, 2014). As such, these two popular scales were used to assess frailty for the current analysis.

2.3.1. Modified Fried frailty phenotype

A modified version of Fried phenotype was used in this study (Fried et al., 2001; Wolfe et al., 2018). At baseline, participants were defined as frail if they satisfied at least three of the following five criteria, or pre-frail if they met one or two criteria: (1) body mass index (BMI) < 20 kg/m2 (“Shrinking”); (2) lowest 20% of grip strength taking into account sex and weight (“Weakness”); (3) the participant reported that “I felt that everything I did was an effort” and/or “I could not get going” for three or more days during the last week, according to a question on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D10) scale (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter & Patrick, 1994) (“Exhaustion”); (4) time to walk 3 m (10 feet) was in the lowest 20% taking into account sex and height (“Slowness”); and (5) no walking outside the home in the last two weeks, or the longest amount of time walking outside without sitting down to rest was less than 10 min, (“Low activity”) according to LIFE Disability questionnaire responses (Cornoni-Huntley, DB, AM, JO & Wallace, 1986; Foley, Berkman, Branch, Farmer & Wallace, 1986; Pahor et al., 2006).

2.3.2. Deficit accumulation frailty index (FI)

A deficit accumulation Frailty Index (FI) of 66 items was constructed using data collected at baseline across multiple domains, including socio-demographic factors, lifestyle factors, chronic medical conditions, morbidities, physical activity, functional engagement, mental health, cognition, laboratory/pathology values and self-rated health status (Ryan et al., 2021). This construct was based on methods from (Rockwood et al., 2005b), and the details of the items and the scales used are published elsewhere (Ryan et al., 2021). The list of items used in the FI for the present study provided as a supplementary material (Appendix A). The FI was calculated as the average number of deficits across all items. Participants were classified as non-frail (≤0.10), pre-frail (>0.10 and ≤0.21) or frail (>0.21), consistent with cut-offs used previously (Pajewski et al., 2016).

2.4. Disability-Free Survival (DFS)

The primary outcome in the ASPREE trial was DFS, a composite measure to capture life-span free from dementia and physical disability (McNeil et al., 2018). It was defined as the time to the first of any one of three events, including death, dementia (based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition [DSM-IV] criteria) or persistent physical disability (McNeil et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2020). Mortality was confirmed from death information collected from at least two independent sources (McNeil et al., 2018). Both immediate cause of death and major underlying illness causing the trajectory to death were adjudicated by an expert panel. According to DSM-IV criteria, the diagnosis of dementia was adjudicated by an international panel of clinicians (Guze (1995). Persistent physical disability was considered to have occurred when a participant reported having an inability to perform, severe difficulty in performing, or requiring assistance to perform, any one of six basic activities of daily living that had persisted for at least six months. In addition, the adjudicated eligibility for ‘admission to residential care’ was included in the definition of persistent physical disability endpoint to overcome the lack of ADL information directly from the participant or an appropriate surrogate (McNeil et al., 2018; Woods et al., 2020). The ASPREE study outcomes were evaluated by annual in-person visits, medical record reviews and by regular 6-month telephone calls (McNeil et al., 2017). Use of prescription medications was checked annually; physical functions (walk test and grip strength) and cognition were assessed every second year; questions about ADLs were collected six-monthly; dementia assessments were conducted as required in response to triggers; deaths were recorded and verified at any time.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The frequency of polypharmacy, non-frailty, pre-frailty and frailty was determined at baseline. Demographic data were described using means and standard deviations or percentages where appropriate and analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square, respectively. The adjusted association of polypharmacy, potential correlates and frailty category was determined using multinomial logistic regression and reported as relative risk ratios (RRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The potential correlates included in adjusted analyses were socio-demographic factors (age, sex, waist circumference, ethno-racial origin and education), lifestyle factors (smoking history and alcohol use) and chronic conditions/morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, depression and previous cancer). We assessed the collinearity between variables by running the variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis as well as examining the correlation matrix. There was no significant collinearity between variables. The association between frailty categories according to polypharmacy exposure at baseline and reducing DFS over the follow-up period was examined by Cox proportional hazards regression model and reported as the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. Proportional hazards assumptions were checked using Schoenfeld residuals. The final model was adjusted for socio-demographic factors, lifestyle factors and chronic conditions/morbidities. In the supplemental analyses of physical disability and dementia, all-cause mortality was treated as a competing risk as individual first events contributing to the composite, and Fine-Gray competing-risks regression analysis for sub-distribution hazards (SDH) and 95% CIs was performed. Cumulative incidences were used to show event risks based on regression models. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA, version 17 (StataCorp. (2021).

2.6. Ethics

The ASPREE clinical trial is registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN83772183) and clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01038583). All federal and local regulations on human subjects’ research were followed with institutional approvals. The Intellectual Property and Ethics Committee approved this current project of Monash University (Reference no. V6VVQTXZ; 29 November 2019) as well as by MUHREC (Ethics #2021/30,049).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of participants

The prevalence of polypharmacy and the distribution of the associated factors at baseline in the ASPREE trial (N = 19,114) are shown in Table 1. Of the total 19,114 participants enrolled (median age 74.0 years, IQR: 6.1 years), 5088 (26.6%) participants met the criteria for polypharmacy. Median numbers of medications were 2 and 6 among ‘no polypharmacy’ and ‘polypharmacy’ categories, respectively, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 2 for both categories. About one-third of pre-frail (33.1% of Fried pre-frail and 36.7% FI pre-frail) and more than half of the frail (55.1% Fried frail and 69.6% FI frail) participants had polypharmacy. In addition, higher age, female sex, higher BMI, higher waist circumference, lower education (≤12 years of education), African-American race, living alone, current smoking and chronic conditions/morbidities were common among participants with polypharmacy.

Table 1.

Number of Participants and the distribution of correlates of polypharmacy at baseline in the ASPREE trial (N = 19,114).

| Characteristics | Total | No polypharmacy (≤4 drugs) | Polypharmacy10 (≥ 5 drugs) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Number of Participants, n (%) | 19,114 | 14,026 (73.4) | 5088 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| Median no. of medications (IQR) | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 6 (2) | |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Fried Phenotype (n = 19,114) | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||

| Non-frail | 11,246 | 8854 (78.7) | 2392 (21.3) | |

| Pre-frail | 7447 | 4983 (66.9) | 2464 (33.1) | |

| Frail | 421 | 189 (44.9) | 232 (55.1) | |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Frailty Index (n = 19,110)1 | <0.001 | |||

|

| ||||

| Non-frail | 9794 | 8634 (88.2) | 1160 (11.8) | |

| Pre-frail | 7766 | 4917 (63.3) | 2849 (36.7) | |

| Frail | 1550 | 472 (30.4) | 1078 (69.6) | |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Age, y, median, (IQR)2 | 74.0 (6.1) | 73.8 (5.8) | 74.6 (6.7) | |

| Age group, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 65–74 y | 11,164 | 8442 (75.6) | 2722 (24.4) | |

| 75–84 y | 7218 | 5072 (70.3) | 2146 (29.7) | |

| >85 y | 732 | 512 (69.9) | 220 (30.1) | |

| Gender, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Women | 10,782 | 7391 (68.5) | 3391 (31.5) | |

| Men | 8332 | 6635 (79.6) | 1697 (20.4) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.1 (4.7) | 27.6 (4.4) | 29.5 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Waist circum, cm, mean (S.D.) | 97.1 (12.9) | 96.1 (12.4) | 100.1 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| Living status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Living alone | 6251 | 4335 (69.4) | 1916 (30.6) | |

| Living with others | 12,863 | 9691 (75.3) | 3172 (24.7) | |

| Ethno-racial origin, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Australian white | 16,361 | 12,093 (73.9) | 4268 (26.1) | |

| U.S. white | 1088 | 797 (73.3) | 291 (26.7) | |

| African-American | 901 | 579 (64.3) | 322 (35.7) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 488 | 352 (72.1) | 136 (27.9) | |

| Others | 275 | 204 (74.2) | 71 (25.8) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| ≤12 y, n (%) | 10,955 | 7761 (70.8) | 3194 (29.2) | |

| > 12 y, n (%) | 8159 | 6265 (76.8) | 1894 (23.2) | |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| Current | 735 | 521 (70.9) | 214 (29.1) | |

| Former | 7799 | 5641 (72.3) | 2158 (27.7) | |

| Never | 10,580 | 7864 (74.3) | 2716 (25.7) | |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Never drinker | 3337 | 2250 (67.4) | 1087 (32.6) | |

| Former drinker | 1135 | 780 (68.7) | 355 (31.3) | |

| Current moderate drinker3 | 14,166 | 10,658 (75.2) | 3508 (24.8) | |

| Current higher drinker4 | 476 | 338 (71.0) | 138 (29.0) | |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Chronic conditions/morbidities | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hypertension5, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 4919 | 4364 (88.7) | 555 (11.3) | |

| Yes | 14,195 | 9662 (68.1) | 4533 (31.9) | |

| Diabetes mellitus6, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 17,069 | 13,046 (76.4) | 4023 (23.6) | |

| Yes | 2045 | 980 (47.9) | 1065 (52.1) | |

| Dyslipidemia7, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 6647 | 5426 (81.6) | 1221 (18.4) | |

| Yes | 12,467 | 8600 (69.0) | 3867 (31.0) | |

| Chronic kidney disease8, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 13,024 | 9922 (76.2) | 3102 (23.8) | |

| Yes | 4740 | 3086 (65.1) | 1654 (34.9) | |

| Depression9, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 17,231 | 12,852 (74.6) | 4379 (25.4) | |

| Yes | 1883 | 1174 (62.4) | 709 (37.6) | |

| Previous cancer, n (%) | 0.284 | |||

| No | 15,454 | 11,366 (73.6) | 4088 (26.4) | |

| Yes | 3660 | 2660 (72.7) | 1000 (27.3) | |

Notes:

Four participants were excluded because they had recorded a response to less than the minimum of 50 items for deficit accumulation FI.

IQR: Interquartile Range.

Moderate alcohol drinker: no more than eight drinks a week and no more than four drinks on any one day.

Higher alcohol drinker: more than eight drinks a week and more than four drinks on any one day.

Hypertension: on treatment for high blood pressure or blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg at trial entry.

Diabetes mellitus: participant’s report of diabetes mellitus or a fasting glucose level of at least 126 mg per deciliter (≥7 mmol per liter) or receipt of treatment for diabetes.

Dyslipidemia: receipt of cholesterol-lowering medication or a serum cholesterol level of at least 212 mg per deciliter (≥5.5 mmol per liter) in Australia and at least 240 mg per deciliter (≥6.2 mmol per liter) in the U.S. or as a low-density lipoprotein level >160 mg per deciliter (>4.1 mmol per liter).

Chronic kidney disease: estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 or a ratio of urinary albumin (in milligrams per liter) to creatinine (in millimoles per liter) in the urine of 3 or more.

Depression was determined by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 10 (CES-D10) cut-off ≥8.

Polypharmacy: taking five or more prescription drugs at baseline.

3.2. Association between polypharmacy and frailty

Table 2 shows the association between polypharmacy and frailty categories at baseline. Those with polypharmacy were 55% more likely to be pre-frail according to Fried phenotype (RRR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.44, 1.68) and more than three times likely to be frail (RRR: 3.34; 95% CI: 2.64, 4.22) compared to those without polypharmacy after adjustment for covariates (Table 2, Model 2). In addition, the effect sizes for the association between polypharmacy and deficit accumulation FI-defined frailty were in the same direction but larger than those of Fried phenotype defined frailty categories.

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression showing the association between polypharmacy and frailty categories at baseline.

| Fried phenotype | Model 1 Unadjusted1 (n = 19,114) |

Model 2 Adjusted2 (n = 17,570) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

RRR3 (95% CI4) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | |

| No frailty | Pre-frailty | Frailty | Pre-frailty | Frailty | |

|

| |||||

| No polypharmacy | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Polypharmacy | Reference | 1.83 (1.71, 1.95) | 4.54 (3.73, 5.53) | 1.55 (1.44, 1.68) | 3.34 (2.64, 4.22) |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Frailty index | Model 1 Unadjusted (n = 19,110) |

Model 2 Adjusted (n = 17,568) |

|||

|

|

RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | |

| No frailty | Pre-frailty | Frailty | Pre-frailty | Frailty | |

|

| |||||

| No polypharmacy | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Polypharmacy | Reference | 4.31 (3.99, 4.66) | 17.00 (15.01, 19.25) | 3.24 (2.96, 3.55) | 11.51 (9.86, 13.44) |

Model 1: Unadjusted analysis.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, gender, waist circumference, ethno-racial origin, education, smoking history, alcohol use and chronic conditions/morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, depression, chronic kidney disease and previous cancer history).

RRR: Relative risk ratio.

CI: Confidence interval.

3.3. Association between polypharmacy-exposed frailty and DFS

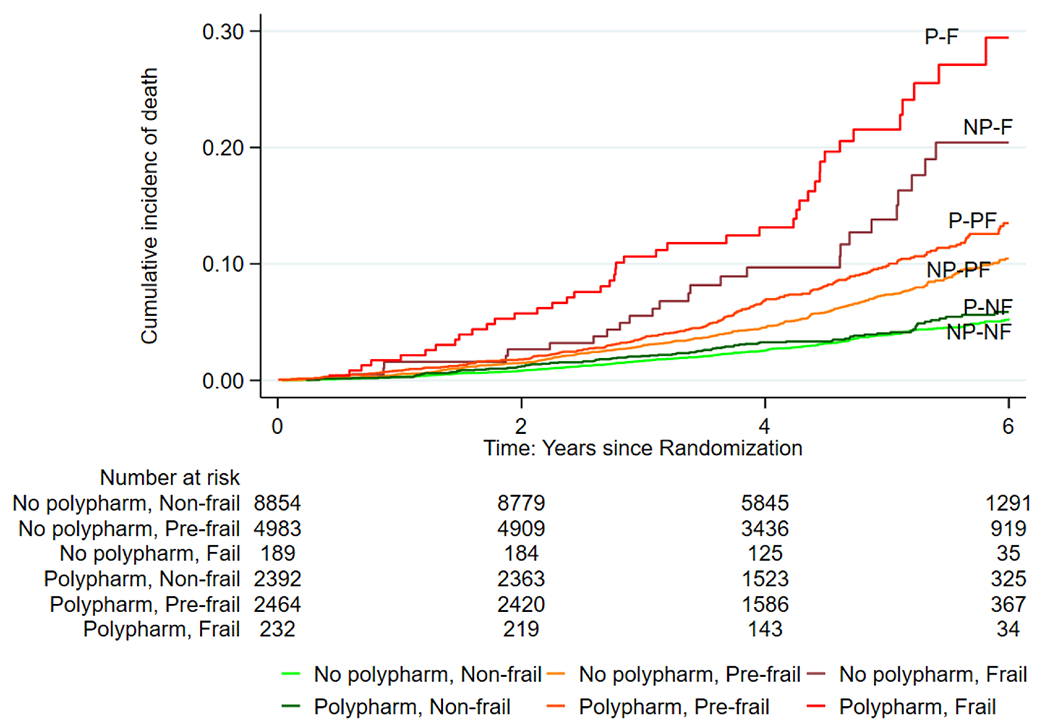

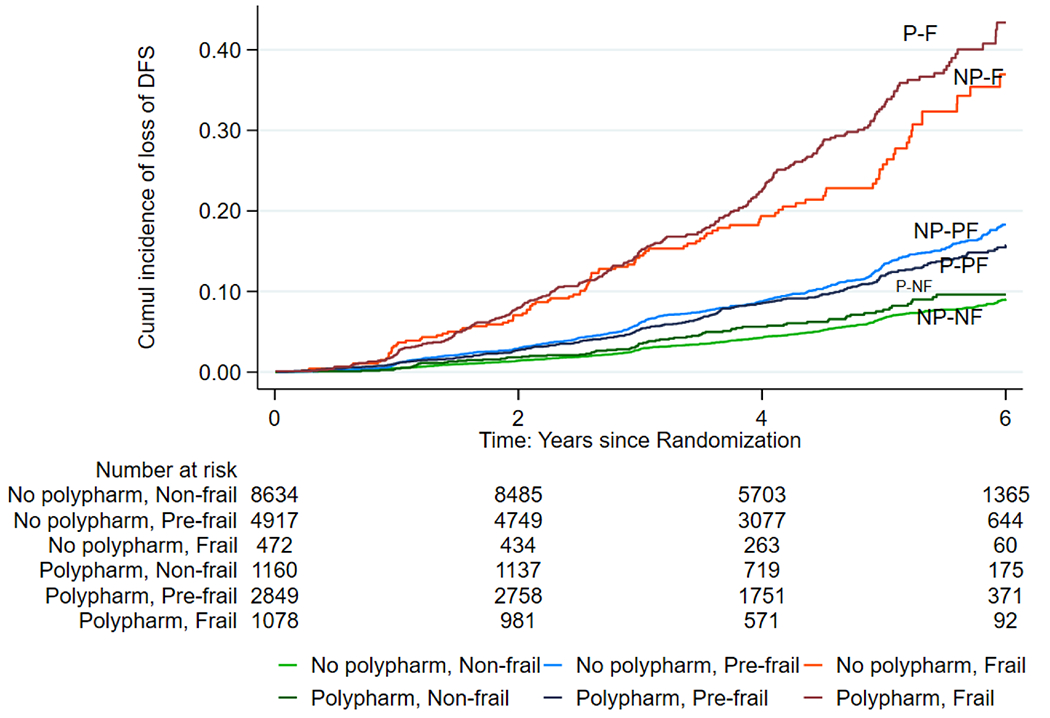

Table 3 shows the association between polypharmacy-exposed frailty at baseline and DFS, over a median of 4.7 years of follow-up. In adjusted analysis, polypharmacy-exposed frailty doubled the risk of a reduced DFS in pre-frail persons (Fried HR: 2.21; 95% CI: 1.91, 2.56; FI HR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.58, 2.19), while the risk increased more than four-fold among frail persons (Fried HR: 4.24; 95% CI: 3.28, 5.47; FI HR: 4.56; 95% CI: 3.78, 5.49) compared with those who were non-frail without polypharmacy. The cumulative hazard estimates of curtailing of DFS among polypharmacy-exposed Fried and FI-defined frail participants are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. Tables B.1, B.2 and B.3 and Figures A.1 to A.6 in the appendices show the associations between polypharmacy-exposed frailty at baseline and components of DFS individually (i.e., all-cause mortality, dementia and physical disability) according to both scales, over a median of 4.7 years of the follow-up period. The results indicate that polypharmacy-exposed frailty categories were associated with all three components of DFS, with physical disability having the highest risk association according to Fried phenotype and FI. Fine-Gray competing-risks regression analysis sub-distribution hazards of dementia and physical disability among polypharmacy-exposed pre-frail and frail persons compared with those who were non-frail without polypharmacy remained significant in adjusted analysis (Appendix Tables B.2 and B.3). In addition, the stratified analysis according to frailty categories showed a dose response effect, particularly from the results for Fried phenotype, where polypharmacy increased DFS loss in individuals who were pre-frail (38%) but even more in individuals who were frail (59%). In individuals who were not frail there was no significant association between polypharmacy and DFS (Appendix Table C).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards estimates for loss of disability-free survival (DFS) according to frailty categories exposed to polypharmacy.

| Fried phenotype | HR3; 95% CI4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n = 19,114; DFS=1835) | Non-frail | Pre-frail | Frail |

| No polypharmacy | Reference | 2.13 (1.89, 2.39) | 4.65 (3.46, 6.25) |

| Polypharmacy | 1.24 (1.04, 1.47) | 2.93 (2.57, 3.34) | 7.56 (5.98, 9.54) |

| Model 2 (n = 17,570; Failure=1705) | Non-frail | Pre-frail | Frail |

| No polypharmacy | Reference | 1.59 (1.40, 1.80) | 2.16 (1.56, 2.99) |

| Polypharmacy | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) | 2.21 (1.91, 2.56) | 4.24 (3.28, 5.47) |

|

| |||

| Frailty Index | HR; 95% CI | ||

|

| |||

| Model 1 (N = 19,110; DFS=1834) | Non-frail | Pre-frail | Frail |

| No polypharmacy | Reference | 2.05 (1.82, 2.31) | 4.25 (3.44, 5.25) |

| Polypharmacy | 1.18 (0.93, 1.50) | 1.85 (1.60, 2.13) | 5.08 (4.38, 5.88) |

| Model 2 (N = 17,568; Failure=1704) | Non-frail | Pre-frail | Frail |

| No polypharmacy | Reference | 1.85 (1.61, 2.11) | 3.25 (2.55, 4.14) |

| Polypharmacy | 1.27 (0.99, 1.63) | 1.86 (1.58, 2.19) | 4.56 (3.78, 5.49) |

Model 1: Unadjusted analysis.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, gender, waist circumference, ethno-racial origin, education, smoking history, alcohol use and chronic conditions/morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, depression, chronic kidney disease and previous cancer history).

HR: Hazard Ratio.

CI: Confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Nelson-Aalen Cumulative Hazard Estimates of the loss of disability-free survival among polypharmacy-exposed frailty according to Fried phenotype (Abbreviations: NP-NF= No Polypharmacy, Non-frail; NP-PF= No Polypharmacy, Pre-frail; NP-F= No Polypharmacy, Frail; P-NF = Polypharmacy, Non-frail; P-PF= Polypharmacy, Pre-frail; P-F = Polypharmacy, Frail).

Fig. 2.

Nelson-Aalen Cumulative Hazard Estimates of the loss of disability-free survival among polypharmacy-exposed frailty according to Frailty Index (Abbreviations: NP-NF= No Polypharmacy, Non-frail; NP-PF= No Polypharmacy, Pre-frail; NP-F= No Polypharmacy, Frail; P-NF = Polypharmacy, Non-frail; P-PF= Polypharmacy, Pre-frail; P-F = Polypharmacy, Frail).

4. Discussion

In this large cohort of 19,114 community-dwelling older people, more than 25% of the participants had polypharmacy on enrollment. Polypharmacy was significantly more prevalent among pre-frail and frail persons than non-frail. Furthermore, pre-frail and frail participants exposed to polypharmacy at baseline had an approximately double and four-fold increased risk of a reduction in DFS, respectively, than non-frail participants without polypharmacy.

Frailty and polypharmacy are two common geriatric conditions. A bidirectional relationship may exist between the two (Cesari, 2020; Nwadiugwu, 2020; Woolford, Aggarwal, Sheikh & Patel, 2021) as frailty and multimorbidity are related, and polypharmacy is common with multimorbidity. However, polypharmacy might contribute to the development of frailty, independent of multimorbidities, perhaps through adverse effects of medications (Saum et al., 2017). It is postulated that adverse drug reactions (ADRs) could become more severe and frequent in older people due to age-dependent pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic changes promoting drug-drug or drug-disease interactions (Gnjidic & Johnell, 2013). These ADRs could directly or indirectly facilitate the development of frailty, worsen the frailty state, or negatively impact frailty criteria (Gnjidic & Johnell, 2013). This might lead to a vicious cycle if ADRs are not identified and managed (Gnjidic & Johnell, 2013).

Although a common condition, polypharmacy has no universal definition (Masnoon, Shakib, Kalisch-Ellett & Caughey, 2017). Current numerical definitions vary from using two to at least 11 medications, including multiple descriptive definitions (Masnoon et al., 2017). Similarly, frailty has several scales to assess this geriatric syndrome with multiple domains. This makes it challenging to compare data from different studies of both polypharmacy and frailty, leading to a wide range of results. We found that 26.6% of our participants met the numerical criteria of polypharmacy, with a relatively higher proportion among participants categorized as pre-frail and frail. Previous studies showed a prevalence of polypharmacy ranging from 26.3% to 46% in community-dwelling older adults in different parts of the world (Fried et al., 2014; Midão et al., 2018). Our cohort displayed a prevalence of polypharmacy at the lower end of this range. The details of the overall medication burden, polypharmacy, hyperpolypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in the ASPREE study have been previously explored and published. Of the cohort, 27% had polypharmacy and 2% hyperpolypharmacy. Overall, cardiovascular drugs were the most common class in the cohort (64%) (Lockery et al., 2020). It is important to note that the presence of frailty, especially when assessed by the Fried phenotype, in the study population was low. The main reason is the inclusion criteria of the original ASPREE primary prevention clinical trial, which recruited only participants known to be free CVD, dementia, major physical disability or five-year life-limiting illness at enrollment, and thus, less likely to require multiple medications compared with the wider, older-age population.

Several studies have previously reported that polypharmacy is associated with frailty in older adults (Herr, Robine, Pinot, Arvieu & Ankri, 2015; Saum et al., 2017; Veronese et al., 2017; Woo, Zheng, Leung & Chan, 2015; Yuki et al., 2018). Nevertheless, previous studies did not use both methods of frailty assessment on the same cohort and other studies were not conducted using a healthy older community-dwelling population like the ASPREE trial. Furthermore, other studies did not look at polypharmacy-exposed frailty as a risk for reducing a healthy life span. Our current study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by confirming the association between polypharmacy and frailty, even among community-dwelling older adults who were generally healthy at baseline. Furthermore, the relationship between polypharmacy and frailty persisted after adjusting for potential confounding by socio-demographic factors, lifestyle factors, and several major chronic conditions/morbidities.

Previous studies (Almada, Brochado, Portela, Midao & Costa, 2021; Chen, Huang, Wen, Chen & Hsiao, 2020; Herr et al., 2015) mainly examined the relation between polypharmacy-exposed frailty with mortality risk. As mentioned already, those studies did not use a composite outcome like DFS, which is considered a better indicator of holistic health outcome, i.e., healthy aging (Shulman et al., 2015). The exchange of the primary endpoint in outcome-oriented clinical studies from mortality to DFS has been considered a paradigm shift (Lönnqvist (2017). In keeping with the changing trend of replacing only mortality as a study outcome, our findings add to the evidence that polypharmacy-exposed frailty is a risk for DFS, which is particularly relevant to geriatric research. Further analysis of the components of DFS favors the hypothesis that polypharmacy independently increases the risk of dementia, physical disability, and all-cause mortality among pre-frail and frail older persons who were free of major CVD, cognitive impairment or physical disability at baseline. Moreover, older individuals can develop multiple chronic conditions/morbidities, leading to polypharmacy exposure. Nevertheless, we have shown that polypharmacy-exposed older persons remain at a higher likelihood of frailty and a higher risk of a reduced healthy life-span even after adjusting for major chronic conditions and morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, depression, chronic kidney disease and previous cancer). The stratified analysis according to frailty categories also showed a dose response-like effect, particularly from the results for Fried phenotype where the presence of polypharmacy increased the loss of DFS in pre-frail individuals, and this loss was even greater in those who were frail.

Our current analysis noted a stronger relative risk ratio (RRR) for the association between frailty and polypharmacy using FI, which was not surprising given that the FI scale included more concomitant health conditions and morbidities many of which would be expected to have medications prescribed. However, overall, the risk of polypharmacy and frailty combined on reducing DFS was very similar with both frailty scales. In addition, as shown in the current analysis here and previously (Espinoza et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2022), the FI used a broader range of domains, resulting in more participants in pre-frail and frail groups than with Fried phenotype. So, our findings indicate that assessing and addressing polypharmacy in older people could be valuable on limiting the impact of frailty on individuals’ functional status, cognition and survival. The current findings are relevant to primary care physicians and general practitioners as they review medication use and consider adding or removing medications; furthermore, pharmacists can play a role in this assessment, particularly in the community setting when they dispense or review medications. To aid these strategies, deprescribing approaches need to be studied to better distinguish the improvements in health risks by reducing or preventing frailty development (Almada et al., 2021).

The strengths of our study stem from the inclusion of a large cohort of relatively healthy community-dwelling older men and women free of major CVD, dementia or physical disability; a standardized, comprehensive recording of all medications; assessment of frailty using two standard scales on the same cohort; and use of DFS as an outcome. In terms of limitations, there was no information regarding medication dosage nor prior exposure/history (e.g., dosage, cumulative exposure). We were also not able to assess participants’ adherence to medications and we did not consider over-the-counter medications in the current analysis. Furthermore, we used modified criteria for the Fried phenotype definition, as we have previously published (Espinoza et al., 2021) which included low BMI of <20 kg/m2 substituting for unintentional weight loss, slowest 20% in gait speed adjusted for height and gender and lowest 20% in grip strength adjusted for BMI and gender. Previous studies also used modified criteria depending upon the availability of data. A systematic review reported that BMI was a validated tool to determine weight loss criterion for Fried phenotype and at least 20 studies assessed shrinking or weight loss criterion by BMI (Theou et al., 2015). Finally, our selected healthy trial population with lower prevalences of frailty and polypharmacy might underestimate the strength of the relationship with loss of DFS across the general population of the same age.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, according to both frailty scales, the current study adds to evidence that polypharmacy is significantly associated with pre-frailty and frailty even among community-dwelling older people free of major CVD, dementia, or physical disability. Moreover, polypharmacy-exposed pre-frailty and frailty increased the risk of a reduced healthy life span among older adults. Addressing polypharmacy in older people could be valuable on limiting the impact of frailty on individuals’ functional status, cognition and survival. Further research should address the potential benefits of reducing polypharmacy and deprescribing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the dedicated and skilled staff in Australia and the United States for the trial’s conduct. The authors are also most grateful to the ASPREE participants, who willingly volunteered for this study, the general practitioners and the medical clinics that supported the participants in the ASPREE study.

Research funding

The ASPREE trial was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant numbers U01AG029824, U19AG062682); the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) (grant numbers 334047, 1127060), Monash University and the Victorian Cancer Agency. In addition, JR is supported by an NHMRC Leader Fellowship (APP1135727). JG-T is supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1107476). The sponsors had no role in the manuscript’s design, conduct, drafting, or publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Statement of ethics

The ASPREE clinical trial is registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN83772183) and clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01038583). The ASPREE clinical trial was conducted following the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki 1964 as revised in 2008, the NHMRC Guidelines on Human Experimentation, the Federal Patient Privacy (HIPAA) law and the International Conference of harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines and followed the Code of Federal Regulations. It was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) (IRB00002519; ethics #2006/745MC) and other allied institution ethics committees. In addition, the Intellectual Property and Ethics Committee (Reference no. V6VVQTXZ; 29 November 2019) and MUHREC (Ethics #2021/30049) have approved this current project of Monash University.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.archger.2022.104694.

References

- Almada M, Brochado P, Portela D, Midao L, & Costa E (2021). Prevalence of falls and associated factors among community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. The Journal of Frailty & Aging, 10, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale). American journal of preventive medicine, 10, 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASPREE Investigator Group. (2013). Study design of ASPirin in reducing events in the elderly (ASPREE): A randomized, controlled trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 36, 555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boney O, Moonesinghe SR, Myles PS, & Grocott MP (2016). Standardizing endpoints in perioperative research. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d’anesthesie, 63, 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M (2020). How polypharmacy affects frailty. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 13, 1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Gambassi G, Abelian Van Kan G, & Vellas B (2014). The frailty phenotype and the frailty index: Different instruments for different purposes. Age and Ageing, 43, 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Prince M, Thiyagarajan JA, De Carvalho IA, Bernabei R, Chan P, et al. (2016). Frailty: An emerging public health priority. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17, 188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YZ, Huang ST, Wen YW, Chen LK, & Hsiao FY (2020). Combined effects of frailty and polypharmacy on health outcomes in older adults: Frailty outweighs polypharmacy. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrials.gov, (2009). Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE).

- Cornoni-Huntley J, DB B, AM O, JO T, Wallace RB, et al. (1986). Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: Resource data book, vol 1. Bethesda, MD: Us department of health and human services, public health service, natioanal institutes of health; (pp. 86–2443). National Institute on Aging, 1986NIH publication no. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza SE, Woods RL, Ekram A, Ernst ME, Polekhina G, Wolfe R, et al. (2021). The effect of low-dose aspirin on frailty phenotype and frailty index in community-dwelling older adults in the ASPirin in reducing events in the elderly study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DJ, Berkman LF, Branch LG, Farmer ME, & Wallace RB (1986). Physical functioning, Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: Resource data book. US department of health and human services. Public Health Service, National Institute of Health, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. (2001). Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 56, M146–M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, & Martin DK (2014). Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, 2261–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, et al. (2012). Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 65, 989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnjidic D, & Johnell K (2013). Clinical implications from drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in older people. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 40, 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guze SB (1995). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV). American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 1228, 1228. [Google Scholar]

- Halli-Tierney AD, Scarbrough C, & Carroll D (2019). Polypharmacy: Evaluating risks and deprescribing. American family physician, 100, 32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr M, Robine J-M, Pinot J, Arvieu J-J, & Ankri J (2015). Polypharmacy and frailty: Prevalence, relationship, and impact on mortality in a French sample of 2350 old people. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 24, 637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, & Kuchel GA (2007). Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima G, Iliffe S, & Walters K (2018). Frailty index as a predictor of mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and ageing, 47, 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelakanok N, & D’Cunha RR (2019). Association between polypharmacy and dementia – A systematic review and metaanalysis. Aging & Mental Health, 23, 932–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Huang Y, Liu Z, Shen R, Chen H, Ma C, et al. (2020). The association between frailty and incidence of dementia in Beijing: Findings from 10/66 dementia research group population-based cohort study. BMC geriatrics, 20, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockery JE, Ernst ME, Broder JC, Orchard SG, Murray A, Nelson MR, et al. (2020). Prescription medication use in older adults without major cardiovascular disease enrolled in the aspirin in reducing events in the elderly (ASPREE) clinical trial. Pharmacotherapy, 40, 1042–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnqvist P-A (2017). Medical research and the ethics of medical treatments: Disability-free survival. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia, 118, 286–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, & Suzuki T (2015). Impact of physical frailty on disability in community-dwelling older adults: A prospective cohort study. BMJ open, 5, Article e008462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, & Caughey GE (2017). What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC geriatrics, 17, 230, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, Murray AM, Reid CM, Kirpach B, et al. (2017). Baseline characteristics of participants in the ASPREE (ASPirin in reducing events in the elderly) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 72, 1586–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, Reid CM, Kirpach B, Wolfe R, et al. (2018). Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. New England Journal of Medicine, 379, 1499–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta RS, Kochar BD, Kennelty K, Ernst ME, & Chan AT (2021). Emerging approaches to polypharmacy among older adults. Nature Aging, 1, 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midão L, Giardini A, Menditto E, Kardas P, & Costa E (2018). Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 78, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwadiugwu MC (2020). Frailty and the risk of polypharmacy in the older person: Enabling and preventative approaches. Journal of aging research, 2020, Article 6759521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahor M, Blair SN, Espeland M, Fielding R, Gill TM, Guralnik JM, et al. (2006). Effects of a physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance: Results of the lifestyle interventions and independence for elders pilot (LIFE-P) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 61, 1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajewski NM, Williamson JD, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Bolin LP, Chertow GM, et al. (2016). Characterizing frailty status in the systolic blood pressure intervention trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 71, 649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel A, Peel NM, Nissen LM, Mitchell CA, Gray LC, & Hubbard RE (2016). Adverse outcomes in relation to polypharmacy in robust and frail older hospital patients. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17, e713, 767,. e769–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, & McDowell I (2005a). A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Canadian Medical Association journal, 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. (2005b). A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 173, 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J, Espinoza S, Ernst ME, Ekram A, Wolfe R, Murray AM, et al. (2021). Validation of a deficit-accumulation frailty index in the ASPREE study and its predictive capacity for disability-free survival. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J, Espinoza S, Ernst ME, Ekram A, Wolfe R, Murray AM, et al. (2022). Validation of a deficit-accumulation frailty index in the ASPirin in reducing events in the elderly study and its predictive capacity for disability-free survival. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 77, 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J, Storey E, Murray AM, Woods RL, Wolfe R, Reid CM, et al. (2020). Randomized placebo-controlled trial of the effects of aspirin on dementia and cognitive decline. Neurology, 95, e320–e331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saum KU, Schottker B, Meid AD, Holleczek B, Haefeli WE, Hauer K, et al. (2017). Is polypharmacy associated with frailty in older people? Results from the ESTHER cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65, e27–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman MA, Myles PS, Chan MT, McIlroy DR, Wallace S, & Ponsford J (2015). Measurement of disability-free survival after surgery. Anesthesiology, 122, 524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp., (2021). Stata Statistical Software: Release 17., pp. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Theou O, Cann L, Blodgett J, Wallace LM, Brothers TD, & Rockwood K (2015). Modifications to the frailty phenotype criteria: Systematic review of the current literature and investigation of 262 frailty phenotypes in the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. Ageing Res Rev, 21, 78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese N, Stubbs B, Noale M, Solmi M, Pilotto A, Vaona A, et al. (2017). Polypharmacy is associated with higher frailty risk in older people: An 8-year longitudinal cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18, 624–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe R, Murray AM, Woods RL, Kirpach B, Gilbertson D, Shah RC, et al. (2018). The aspirin in reducing events in the elderly trial: Statistical analysis plan. International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society, 13, 335–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Zheng Z, Leung J, & Chan P (2015). Prevalence of frailty and contributory factors in three Chinese populations with different socioeconomic and healthcare characteristics. BMC geriatrics, 15, 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RL, Espinoza S, Thao LTP, Ernst ME, Ryan J, Wolfe R, et al. (2020). Effect of aspirin on activities of daily living disability in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolford SJ, Aggarwal P, Sheikh CJ, & Patel HP (2021). Frailty, multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Medicine (United Kingdom), 49, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yuki A, Otsuka R, Tange C, Nishita Y, Tomida M, Ando F, et al. (2018). Polypharmacy is associated with frailty in Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Gedatrics & gerontology international, 18, 1497–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.