Abstract

Objective

Prior studies have suggested that self-rated health may be a useful indicator of cardiovascular disease. Consequently, we aimed to assess the relationship between self-rated health, cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical cardiac disease in the Amazon Basin.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting, participants and interventions

In participants from the Amazon Basin of Brazil we obtained self-rated health according to a Visual Analogue Scale, ranging from 0 (poor) to 100 (excellent). We performed questionnaires, physical examination and echocardiography. Logistic and linear regression models were applied to assess self-rated health, cardiac risk factors and cardiac disease by echocardiography. Multivariable models were mutually adjusted for other cardiovascular risk factors, clinical and socioeconomic data, and known cardiac disease.

Outcome measures

Cardiovascular risk factors and subclincial cardiac disease by echocardiography.

Results

A total of 574 participants (mean age 41 years, 61% female) provided information on self-rated health (mean 75±21 (IQR 60–90) points). Self-rated health (per 10-point increase) was negatively associated with hypertension (OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.97), p=0.01), hypercholesterolaemia (OR 0.89 (95%CI 0.80 to 0.99), p=0.04) and positively with healthy diet (OR 1.13 (95%CI 1.04 to 1.24), p=0.004). Sex modified these associations (p-interaction <0.05) such that higher self-rated health was associated with healthy diet and physical activity in men, and lower odds of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in women. No relationship was found with left ventricular ejection fraction <45% (OR 0.97 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.23), p=0.8), left ventricular hypertrophy (OR 0.97 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.24), p=0.81) or diastolic dysfunction (OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.40), p=0.51).

Conclusion

Self-rated health was positively associated with health parameters in the Amazon Basin, but not with subclinical cardiac disease by echocardiography. Our findings are of hypothesis generating nature and future studies should aim to determine whether assessment of self-rated health may be useful for screening related to policy-making or lifestyle interventions.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04445103; Post-results

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, CARDIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This is the first study to examine self-rated health in a rural part of the Amazon Basin of Brazil using an internationally recognised questionnaire, EQ-5D-5L.

We applied a state-of-the-art echocardiographic imaging protocol to identify underlying cardiovascular disease.

Self-reported health behaviour could be subject to social and cultural biases.

Because no standard values of the EQ-5D-5L health instrument have been published for Brazil, it is not possible to compare our findings with other populations.

The study design was cross-sectional.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality worldwide and accounts for more than 31% of all deaths and 8% of public hospitalisations in Brazil.1 2 Since the 1960s, Brazil has experienced a transition in health behaviour and cardiovascular risk factors, where tobacco consumption has declined and obesity has increased.2 Approximately 35% of Brazilian adults suffer from hypertension,3 the prevalence of diabetes mellitus is rising4 and a high proportion of adults do not practise recommended levels of physical activity.2 Differences in perception of risk factors and variability in access to healthcare unequivocally affect health behaviour and the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease. In this regard, self-rated health is widely used as a health indicator in various populations,5 is strongly associated with cardiovascular morbidity6 7 and provides prognostic information on mortality.8 Self-rated health and cardiovascular risk factors are also both influenced by sex.9 10 Throughout the last decades, assessment of self-rated health has become increasingly important and is often used for healthcare surveillance and in policy-making.

To understand whether self-rated health in future studies may be used to screen for cardiac disease in low-income settings, we aimed to investigate the relationship with cardiovascular risk factors and disease in the general population from the Amazon Basin of Brazil. We hypothesised that higher self-rated health was associated with less cardiovascular risk factors and disease, and that these relationships were modified by sex.11

Methods

Study site

The study was conducted in the municipality of Cruzeiro do Sul, Acre (Northern Brazil; Amazon Basin). The prevalence for cardiovascular disease in Acre (5815 per 100 000 inhabitants) is below the average rate for Brazil (6025 per 100 000 inhabitants) and the region is considered to be one of the poorest in Brazil and has one of the lowest population densities.12 13

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the study design, recruitment to and conduct of the study nor reporting of results. All patients were informed of the results from their own examinations conducted in the study. Data will be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

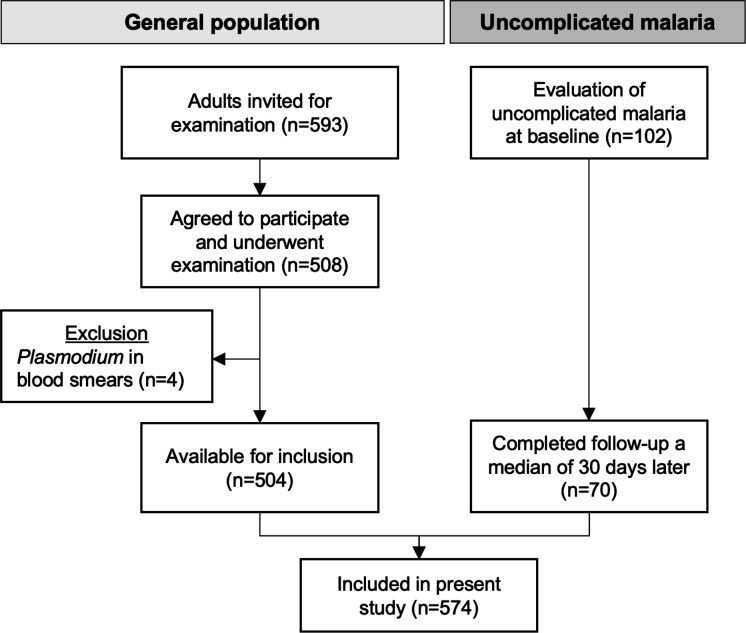

Sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted as a part of the Malaria Heart Study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04445103). Participants from the general population were enrolled from June 2020 to December 2020. Through randomisation, we selected 10 local healthcare clinics from Cruzeiro do Sul, equally distributed between rural and urban areas. Local healthcare agents provided lists of persons associated with each clinic, who we invited to participate in the study (figure 1). We included persons ≥18 years old who completed the examination programme and responded to all questionnaires. Exclusion criteria were ongoing pregnancy, ongoing infection as assessed by examination of a medical doctor and presence of Plasmodium in peripheral blood smears. A total of 504 participants from the general population were included from healthcare clinics. As a part of the main study, we also examined patients diagnosed with uncomplicated malaria in healthcare clinics. This group of participants underwent a follow-up examination a median of 30 days later, when they had completed treatment and had no symptoms of malaria. According to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 70 participants from this group were eligible for inclusion (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart. Inclusion of the study population in Cruzeiro do Sul, Acre.

Data collection

Two different questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers (ie, study personnel). These interviewers also filled out the questionnaires. The first was the EuroQol-5 Domain-5 Level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire, which is validated in Brazilian Portuguese (study registration no.: 28276).14 For the purpose of this study, we used data from theEuroQol Visual Analogue Scale, which provides a single estimate of self-rated health ranging from 0 to 100 points on a continuous scale. Zero represents the worst possible self-rated health and 100 represents ideal health. The second questionnaire was used to gather information about socioeconomic status, race, cardiovascular risk factors, known cardiac disease (prior myocardial infarction and heart failure) and current medications. Race was self-reported, and two persons did not answer this question. Afterwards, participants underwent a physical examination to measure height, weight and blood pressure. Fingerstick point-of-care blood draws were used to measure glucose levels and to obtain thick and thin blood slides. Giemsa stained thick and thin blood slides were analysed by two independent microscopists to detect Plasmodium. A medical doctor (PB) evaluated all patients. None of them displayed clinical signs or symptoms of heart disease (absence of shortness of breath, chest pain, swelling of legs and irregular heart rhythm). All data were quality controlled by AEH and PB on a daily basis.

Cardiovascular risk factors

We assessed seven different cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension was defined as a physician diagnosis of hypertension or intake of antihypertensive medication, hypercholesterolaemia as a physician diagnosis of dyslipidaemia or intake of lipid-lowering medication, and diabetes as a physician diagnosis of diabetes or fasting blood glucose >126 mg/dL.15 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as: body weight (kilograms)/height2 (metres), and obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Participants were classified as smokers if they were current smokers or had previously smoked. A healthy diet was defined as intake of any quantity of vegetables with a main meal ≥3 times/week. Physical activity was defined as participation in any kind of physical activity, on a weekly basis, during leisure time. We did not apply any time limit or threshold.

Biochemistry

Field procedures

During examinations, we collected peripheral venous blood samples in citrate, EDTA and serum-separator tubes, which were cooled at 2°C–8°C. Citrate plasma was immediately separated by centrifugation (12 min, 3200 rpm) in a mobile laboratory and transferred to Eppendorf tubes.

Laboratory

Serum-separator tubes underwent centrifugation (10 min, 3000 rpm) to extract serum which was subsequently stored at −20°C in Eppendorf tubes. Laboratory analyses were performed at Citolab and Centro de Diagnósticos, Cruzeiro do Sul, Acre, Brazil. Using EDTA blood, a complete blood count with a differential was conducted (NX-350, Sysmex, Japan; Citolab), and reticulocytes were counted manually (Citolab).16 Citrate plasma was used to analyse coagulation parameters (Coagmaster 2.0, Wama Diagnóstica, Brazil; Citolab). Serum was used to measure creatinine, bilirubin and C reactive protein (Cobas c111, Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland; Citolab and Centro de Diagnósticos). Analyses of C reactive protein were only available in a subset of participants (n=436).

Echocardiography

A single medical doctor either performed or supervised all echocardiographic examinations (PB). Quality control was conducted on a frequent basis in a central imaging laboratory (Herlev-Gentofte Hospital, Denmark) by an investigator certified in echocardiography by the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Examinations were performed bedside (Vivid-IQ, GE Healthcare, Norway), and images were stored offline for analysis in EchoPAC BT13 (V.203.82). Analyses were conducted by AW according to contemporary guidelines.17 Rheumatic heart disease was assessed by PB according to the World Heart Federation criteria.18 We assessed three categories of subclinical left ventricular (LV) cardiac disease, namely: (1) reduced contractile function defined as LV ejection fraction <45%, (2) LV hypertrophy defined as LV mass index >115 g/m2 for men and>95 g/m2 for women and (3) diastolic dysfunction determined according to existing guidelines.19 Classification of diastolic dysfunction involved assessment of early and late mitral inflow velocity, mitral annular early diastolic velocity, tricuspid regurgitation velocity and the left atrial volume index. Additional details are described in the online supplemental data methods.

bmjopen-2021-058277supp001.pdf (186.4KB, pdf)

Statistics

Baseline characteristics for the study population were stratified according to tertiles of self-rated health (cut-offs of 70 and 91 points) and sex. Due to the nature of the distribution, tertiles of self-rated health did not contain equal amounts of participants. P for trend was calculated using linear regression models and the Cuzick non-parametric test for trend.20 Differences between groups were compared using the χ2 test, Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Histograms were conducted to display the distribution of self-rated health. In all statistical tests, self-rated health was treated as a continuous variable. Logistic regression models were conducted to examine the relationship between self-rated health and cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Multivariable models were adjusted for core variables: clinical data (age, sex and race), socioeconomic data (work, family income and living area), known cardiac disease (prior myocardial infarction, heart failure and rheumatic heart disease). Included variables were selected based on prior studies of self-rated health21–23 and were defined prior to commencing data analyses. In addition, all associations with cardiovascular risk factors were mutually adjusted for all other risk factors. Interactions with sex were also examined. Family income was log-transformed to provide a normal distribution. The relationship between self-rated health and (1) the sum of cardiac risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, obesity and smoking) and (2) echocardiographic parameters were assessed in linear regression models, which were adjusted for the core variables. As this was a secondary study, no sample size calculation was conducted. All analyses were conducted in Stata V.14.2 (StataCorp) and RStudio V.1.3 (R, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

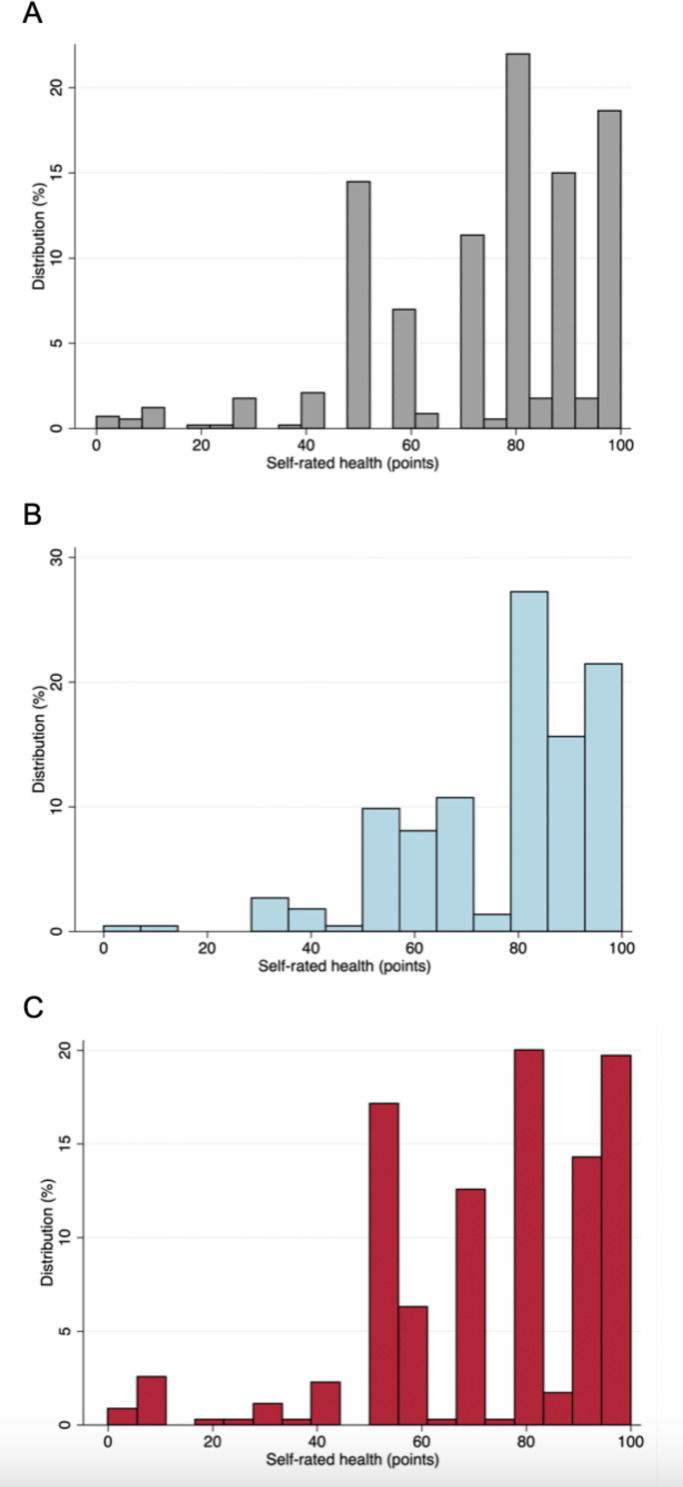

A total of 574 participants were assessed (mean age 41±15 years, 61% female). Mean self-rated health was 75±21 points (IQR 60–90 points) (figure 2A). Four participants (<1%) reported 0 points and 91 participants (16%) reported 100 points. The prevalences of cardiovascular risk factors were 20% for hypertension, 16% for hypercholesterolaemia, 6% for diabetes, 23% for obesity, 38% for current or prior smoking, 52% for unhealthy diet and 63% for absence of physical activity. Participants with lower self-rated health more frequently had all of the above risk factors and were older compared with participants with high self-rated health (p-trend <0.05; table 1). No differences were observed in socioeconomic characteristics, biochemistry or subclinical cardiac disease by echocardiography (reduced LV ejection fraction, hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction) across tertiles of self-rated health (table 1).

Figure 2.

Histograms of self-rated health. Distribution of self-rated health in the (A) entire study population (n=574), (B) in men (n=224) and (C) in women (n=350).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics by tertiles of self-rated health

| Tertiles of self-rated health | ||||

| 1st tertile (n=231) | 2nd tertile (n=226) | 3rd tertile (n=117) | P trend* | |

| 0 to 70 | 71 to 90 | 91 to 100 | ||

| Baseline | ||||

| Age, years | 46±16 | 38±13 | 39±15 | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 154 (67%) | 127 (56) | 69 (59) | 0.06 |

| Self-reported race, % | 0.51 | |||

| White | 33 (14) | 24 (11) | 20 (17) | |

| Mixed | 163 (71) | 175 (77) | 77 (66) | |

| Black | 32 (14) | 26 (12) | 18 (15) | |

| Indigenous | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28±6 | 27±5 | 26±4 | 0.002 |

| Abdominal circumference, cm | 90±14 | 87±12 | 84±11 | <0.001 |

| Asthma, % | 11 (5) | 8 (4) | 2 (2) | 0.36 |

| COPD, % | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.92 |

| History of MI, % | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Heart failure, % | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.47 |

| Rheumatic heart disease, % | 7 (3) | 7 (3) | 4 (3) | 0.97 |

| SBP, mmHg | 134±20 | 131±20 | 131±19 | 0.29 |

| DBP, mmHg | 83±12 | 81±11 | 82±12 | 0.17 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension, % | 66 (29) | 32 (14) | 14 (12) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, % | 52 (23) | 23 (10) | 14 (12) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 21 (9) | 6 (3) | 6 (5) | 0.012 |

| Obesity, % | 68 (29) | 45 (20) | 20 (17) | 0.012 |

| Smoking, % | 106 (46) | 65 (29) | 46 (39) | <0.001 |

| Healthy diet, % | 87 (38) | 130 (58) | 59 (50) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity, % | 64 (28) | 94 (42) | 53 (45) | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Work status, % | 0.09 | |||

| Employed | 77 (33) | 98 (43) | 53 (45) | |

| Self-employed | 20 (9) | 23 (10) | 9 (8) | |

| Other | 134 (58) | 105 (47) | 55 (47) | |

| Family income, BRL | 1250(800, 2000) | 1500(1000, 3000) | 1200(800, 2000) | 0.11 |

| Rural living area, % | 92 (40) | 78 (35) | 55 (47) | 0.08 |

| Biochemistry | ||||

| Blood sugar, mg/dL | 110±74 | 100±27 | 110±49 | 0.1 |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.3(0.2, 0.5) | 0.4(0.2, 0.5) | 0.4(0.2, 0.5) | 0.55 |

| Platelets, x 109/L | 229±76 | 240±67 | 234±66 | 0.28 |

| Leucocytes, x 109/L | 6.35±1.99 | 6.38±1.72 | 6.53±1.92 | 0.68 |

| Reticulocytes, % | 0.75±0.19 | 0.80±0.22 | 0.77±0.22 | 0.44 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 140±14 | 142±14 | 142±12 | 0.13 |

| C reactive protein, mg/L | 0(0, 0) | 0(0, 0) | 0(0, 0) | 0.44 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.59 |

| INR | 1.02±0.12 | 1.01±0.10 | 1.02±0.10 | 0.3 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LV ejection fraction <45%, % | 9 (4) | 6 (3) | 3 (3) | 0.69 |

| LV hypertrophy, % | 9 (4) | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | 0.39 |

| Diastolic dysfunction, % | 7 (3) | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.43 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 57±6 | 57±5 | 58±5 | 0.48 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 71±18 | 68±17 | 70±16 | 0.11 |

| E/e’ | 7.3±2.6 | 6.7±2.1 | 6.9±2.3 | 0.014 |

| E/A | 1.2±0.5 | 1.3±0.4 | 1.3±0.4 | 0.003 |

| Left atrial volume index, mL/m2 | 20±6 | 19±5 | 19±4 | 0.025 |

| TR velocity, m/s | 2.3±0.3 | 2.3±0.3 | 2.3±0.2 | 0.34 |

Normally distributed variables are displayed as mean±SD. Non-normally distributed variables are presented as median (IQR). Proportions are displayed as n (%).

*P for trend was calculated using linear regression models for normally distributed variables and Cuzick’s non-parametric test for trend for non-normally distributed variables.

A, late mitral inflow velocity; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; e', mitral annular early diastolic velocity; E, early mitral inflow velocity; INR, international normalised ratio; LV, left ventricular; MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

Cardiovascular risk factors

In unadjusted logistic regression models, better self-rated health was significantly associated with lower odds of all cardiovascular risk factors (p<0.05 for all; table 2). In adjusted models, self-rated health (per 10-point increase) was associated with lower odds of hypertension (OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.97), p=0.01), hypercholesterolaemia (OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.99), p=0.04) and higher odds of healthy diet (OR 1.13 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.24), p=0.004). In multivariable models, better self-rated health was also associated with the sum of cardiovascular risk factors (beta=−0.07 per 10-point increase (95% CI −0.10 to −0.03), p<0.001). The associations remained unchanged when we excluded participants recently treated for malaria (online supplemental table 1).

Table 2.

Association between self-rated health (per 10 increase), cardiovascular risk factors and disease in the entire population (n=574)

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR(95% CI)* | P value | P interaction sex | |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Hypertension | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) | 0.011 | 0.005 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.99) | 0.044 | 0.29 |

| Diabetes | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.97) | 0.021 | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.22) | 0.80 | 0.17 |

| Obesity | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.98) | 0.017 | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | 0.30 | 0.78 |

| Smoking | 0.86 (0.79 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | 0.39 | 0.003 |

| Heathy diet | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) | 0.008 | 1.13 (1.04 to 1.24) | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| Physical activity | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.26) | 0.001 | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 0.079 | <0.001 |

| Subclinical cardiac disease | |||||

| LV ejection fraction <45% | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.08) | 0.22 | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.23) | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| LV hypertrophy | 0.87 (0.72 to 1.07) | 0.19 | 0.97 (0.76 to 1.24) | 0.81 | 0.31 |

| Diastolic dysfunction | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.15) | 0.47 | 1.09 (0.85 to 1.40) | 0.51 | 0.63 |

*Multivariable models were mutually adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, obesity, smoking, healthy diet, physical activity) in addition to age, sex, work, family income, living area (rural/urban) and prior heart disease.

LV, left ventricular.

Subclinical cardiac disease by echocardiography

No significant associations were found between self-rated health (per 10-point increase) and subclinical cardiac disease by echocardiography: LV ejection fraction <45% (OR 0.88 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.08), p=0.22), LV hypertrophy (OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.07), p=0.19) or diastolic dysfunction (OR 0.92 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.15), p=0.47) (table 2). No individual echocardiographic parameters (assessed continuously) were significantly associated with self-rated health in multivariable models (p>0.05 for all; table 3).

Table 3.

Self-rated health (per 10 point increase) and echocardiographic parameters in the entire population (n=574)

| Unadjusted beta (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted beta (95% CI)* | P value | |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.04 (−0.16 to 0.25) | 0.67 | 0.04 (−0.17 to 0.25) | 0.71 |

| Left ventricular mass index | −0.46 (−1.12 to 0.21) | 0.18 | 0.12 (−0.46 to 0.70) | 0.69 |

| e’ | 0.40 (0.25 to 0.54) | <0.001 | 0.06 (−0.04 to 0.15) | 0.23 |

| E/e’ | −0.16 (−0.25 to −0.07) | 0.001 | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.09) | 0.76 |

| E/A | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) | <0.001 | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.99 |

| Left atrial volume index | −0.26 (−0.46 to −0.06) | 0.012 | −0.05 (−0.22 to 0.13) | 0.61 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity | −0.01(−0.02 to −0.01) | 0.21 | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.1) | 0.95 |

*Multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, work, family income, living area (rural/urban) and prior heart disease.

A, late mitral inflow velocity; e’, mitral annular early diastolic velocity; E, early mitral inflow velocity.

Interactions with sex

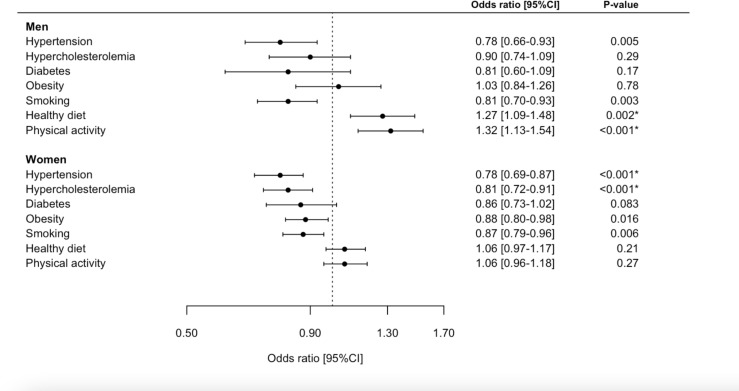

Self-rated health was higher in men than in women (77 vs 73 points) but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.09) (figure 2B–C). In general, women had higher BMI, lower income, less frequently smoked and were less physically active compared with men (p<0.05 for all; online supplemental table 2). Sex modified the associations with hypertension, smoking, healthy diet and physical activity, but not subclinical cardiac disease by echocardiography (table 2). Unadjusted associations with cardiovascular risk factors, stratified by sex, are presented in figure 3. For men, higher self-rated health (per 10-point increase) yielded greater odds of a healthy diet (adjusted OR 1.33 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.59), p=0.002) and physical activity (adjusted OR 1.24 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.50), p=0.02). For women, higher self-rated health (per 10-point increase) was associated with lower odds of hypertension (adjusted OR 0.85 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.97), p=0.016) and hypercholesterolaemia (adjusted OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.99), p=0.046). The associations remained unchanged when we excluded participants from the malaria group (online supplemental table 2 and figure 1).

Figure 3.

Forest plot. Association between self-rated health (per 10-point increase) and cardiovascular risk factors stratified by sex. *Indicates that the association persisted to be significant in multivariable models.

Discussion

This study has two principal findings. First, in a sample of the general population from the Amazon Basin, we found that self-rated health was significantly associated with cardiovascular risk factors and that these associations were modified by sex. Second, self-rated health was not associated with cardiac disease assessed by echocardiography. These findings indicate that in a low-income setting, self-rated health may to some extent provide information on cardiac risk profiles.

Self-rated health has previously been related to cardiovascular disease in various observational studies.24–26 Higher self-rated health is related to a lower burden of cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, obesity), associations that persist after accounting for sociodemographic characteristics and baseline cardiac disease. Proposed mechanisms involve (1) chronic elevation of inflammatory cytokines (‘immune-activated sickness’),27 (2) a poorly balanced activation of the autonomous nervous system and (3) glucose levels.28 Furthermore, self-rated health has been linked to subclinical cardiac alterations, for example, elevated coronary artery calcium score,24 cardiac biomarkers29 and reduced right ventricular function.30 We found no associations with left or right ventricular echocardiographic parameters, possibly because our sample was derived from an overall healthy general population, participants were young (mean age 41 years) and echocardiographic alterations may possibly occur later in the cascade of cardiac pathology compared with elevated calcium scores and biomarkers. Another potential reason could be low statistical power due to the limited size of the study population.

Importantly, women had somewhat lower self-rated health than men, and the relationship with cardiovascular risk factors was further modified by sex. Both findings are in line with previously published data.31–33 While the mechanisms for this remain unknown, women may be particularly sensitive to chronic health conditions, thus affecting self-rated health.34 Recent studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of cardiovascular disease is higher in women, emphasising that an appraisal of sex differences is necessary to obtain maximum benefit of lifestyle interventions for the prevention of cardiac disease.35

Throughout the last decades, quality of life has been used as a tool to measure outcome of healthcare interventions and guide healthcare policy making. Although self-rated health represents a generic measure that encompasses many dimensions of health, and as such, has limited sensitivity to address specific health issues, it is considered a reliable measure to compare health in different populations and to evaluate disease burden.36 Because classic risk tools for cardiovascular disease do not capture social determinants, it has even been argued that self-rated health, in addition to classic risk factors, may be more useful for cardiovascular risk prediction. The EuroQol visual analogue scale constitutes a widely used tool for this purpose.14 In the Amazon Basin, the average self-rated health score was 75 points, which is lower compared with other studies from Brazil, where average scores of 78–84 points have been reported.9 37 Notably, none of these studies were conducted in Northern Brazil, and the assessed populations were younger than our sample. In addition, differences in cultural, regional and disease patterns may partake in understanding this difference, and further explain why general life expectancy in the Amazon Basin is below the national average in Brazil.38

Self-rated health relies on patient-centred care, which integrates the patient’s environment, values and preferences, hence making it meaningful to the patient and the treating clinician. It is a reproducible and consistent measure across different populations and geographical regions,36 and it may potentially complement well-established risk scoring models for cardiovascular disease.39 Because self-rated health is easily obtained, it can help to facilitate risk assessment strategies. This is particularly important in areas such as the Amazon Basin where access to healthcare is highly variable and often limited. Considering the close relationship we found with several cardiovascular risk factors, self-rated health could be obtained by non-medical personnel and enable screening of remote communities. Consequently, selected individuals, that is, persons with low self-rated health and no known cardiovascular risk factors, could be referred for risk factor optimisation in healthcare facilities. Furthermore, it could be used as a measure for the effect of primary healthcare prevention strategies, similar to what has been reported previously.40 Whether self-rated health is linked to clinical outcomes in the Amazon Basin, and if improvement in self-rated health could improve prognosis, should be explored in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

Socioeconomic status is perceived to be associated with self-rated health and cardiovascular risk factors,41 42 and despite our multivariable adjustment, residual confounding may still exist. Interestingly, parameters of socioeconomic status did not vary significantly across tertiles of self-reported health (table 1), indicating that this relationship may differ in this region. Health-related behaviour, including healthy diet and physical activity, was self-reported and this could be associated with bias. Furthermore, it is a limitation that the questionnaire for health behaviour has not been validated in other studies or settings. We adjusted our models for cardiac disease at baseline in an attempt to limit reverse causation; however, some effect may persist. To reduce bias, we had a clear and predefined hypothesis prior to commencing data analyses and a rigorous design for the sequence of questionnaires. To increase the sample size, we included a subgroup of participants recently treated for malaria (n=70). As this group was derived from the same population, had completed treatment for malaria and all associations remained significant when excluded, we do not believe its inclusion affects the generalisability of our results. Because no standard data values of the EQ-5D-5L have been published in Brazil, we did not apply data from the five dimensions of quality of life in this study, nor calculate index scores. Data from this study represent an important first step in establishing EQ-5D-5L index values for the rural parts of the Amazon basin. Reference values for the EQ-5D-3L9 have been published, but cross-walk datasets are not available. To avoid the inclusion of white coat hypertension, we defined hypertension based on prior physician diagnosis and/or intake of anti-hypertensive medication. While the generalisability of our findings to other regions in the world may be disputed, the Amazon Basin covers eight other countries in addition to Brazil. Hence, our findings are likely to be applicable to populations in these areas or to populations who share similar environment and culture.

Conclusion

Self-rated health was positively associated with a healthy lifestyle, and this relationship was modified by sex. Conversely, self-rated health was not associated with cardiac disease by echocardiography. On a hypothesis-generating basis, healthcare policies could potentially use self-rated health for screening or as a target to improve health behaviour. Nevertheless, this should be investigated in future validation studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the help and guidance from Dr. Suiane da Costa Negreiros do Valle and Janaína Alencar. We thank the EuroQol organization for permitting us to use the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire.

Footnotes

Contributors: AEH, TBS, OMS and PB were responsible for the conception of the study and research question. AEH and PB acquired funding to conduct the study. AEH, LCG and PB planned the study and facilitated logistics. AEH, LCG, LOM, AW, KOL, IVMV and PB collected data from the field and prepared collected samples in the laboratory. AEH, AW, MDK and PB undertook data analyses while AEH conducted statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript with support from PB. MP, RMS and CRFM provided critical feedback for interpretation of the data. All authors critically reviewed the study findings and read and approved the final version before submission. PB is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: Funding specifically rewarded for the Malaria Heart Study: PB and AEH: Jette and Hans Henrik Jensen (No. N/A), The Independent Research Fund Denmark (0129-0003B), Dansk Medicinsk Selskab København (120620-kms), Julie von Müllens Fond (No. N/A), Knud Højgaards Fond (18-05-2487), A. P. Møllers Lægefond (18-L-0026), Reinholdt W. Jorck og Hustrus Fond (18-JU-0485), Eva og Henry Frænkels Mindefond (NLA-080919), Astra Zeneca/Danish Society of Cardiology (No. N/A), Internal Funds at Herlev-Gentofte Hospital (No. N/A), Torben og Alice Frimodts Fond (TA250419), Brorsons Fond (12038-1-hh), Lundbeckfonden (R373-2021-1201). AW: Danish Heart Association (20-R139-A9644-22165), William Demant (20-1257), Knud Højgaards Fond (20-01-1076), Reinholdt W. Jorck og Hustrus Fond (20-JU-0145). MK: Novo Nordisk Fonden (NNF20OC0062782). LCG: CNPq (142306/2020-7). Other sources of funding: CRFM: FAPESP (2020/06747-4) and CNPq (302917/2019-5).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional review committee at Federal University of Acre and University of São Paulo (CAAE: 26552619.6.0000.510 and 32947520.4.0000.5467), local health care authorities and leaders of health care clinics. The study complies with the second Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent on oral and written information given in Portuguese before taking part. Illiterate participants provided fingerprints instead of signatures. For ethical reasons a medical doctor evaluated all participants on-site, and in case of suspected heart disease participants were referred to a cardiologist.

References

- 1.Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2982–3021. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro ALP, Duncan BB, Brant LCC, et al. Cardiovascular health in Brazil: trends and perspectives. Circulation 2016;133:422–33. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chor D, Pinho Ribeiro AL, Sá Carvalho M, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and influence of socioeconomic variables on control of high blood pressure: results of the ELSA-Brasil study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127382–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saúde Mda. Vigitel Brasil 2019, 2020. ISBN: 9788533427655. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams J, Amin A, et al. Social determinants of self-reported health in women and men: understanding the role of gender in population health. PLoS One 2012;7:e34799. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Linde RM, Mavaddat N, Luben R, et al. Self-rated health and cardiovascular disease incidence: results from a longitudinal population-based cohort in Norfolk, UK. PLoS One 2013;8:2–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Møller L, Kristensen TS, Hollnagel H. Self rated health as a predictor of coronary heart disease in Copenhagen, Denmark. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996;50:423–8. 10.1136/jech.50.4.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Idler EL, Benyamini Y, Health S-R. Self-Rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos M, Monteiro AL, Santos B. EQ-5D Brazilian population norms. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021;19:1–7. 10.1186/s12955-021-01671-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonçalves RPF, Haikal DS, Freitas MI. Self-Reported medical diagnosis of heart disease and associated risk factors: National health survey. Rev Bras Epidemiol 2019;22. 10.1590/1980-549720190016.supl.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boerma T, Hosseinpoor AR, Verdes E, et al. A global assessment of the gender gap in self-reported health with survey data from 59 countries. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1–9. 10.1186/s12889-016-3352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira GMMde, Brant LCC, Polanczyk CA, et al. Cardiovascular statistics - Brazil 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol 2020;115:308–439. 10.36660/abc.20200812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, et al. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet 2011;377:1778–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. EuroQol. EQ-5D-5L questionnaire in Brazilian Portuguese. Available: https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/ [Accessed 29 May 2022].

- 15.American Diabetes Association . 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43:S14–31. 10.2337/dc20-S002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simionatto M, de Paula JP, Chaves MAF, et al. Manual and automated reticulocyte counts. Hematology 2010;15:406–9. 10.1179/102453310X12647083621128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:e14:1–39. 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297–309. 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;17:1321–60. 10.1093/ehjci/jew082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med 1985;4:87–90. 10.1002/sim.4780040112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gafarov V, Panov D, Gromova E, et al. Sex differences and trends of self-rated health in population aged 25-64 years from 1988 to 2017. Eur J Public Health 2021;31. 10.1093/eurpub/ckab165.231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achdut N, Sarid O. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: the mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Isr J Health Policy Res 2020;9:1–12. 10.1186/s13584-019-0359-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong W, Wan J, Xu Y, et al. Determinants of self-rated health among Shanghai elders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017;17:1–12. 10.1186/s12889-017-4718-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orimoloye OA, Mirbolouk M, Uddin SMI. Association between self-rated health, coronary artery calcium scores, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:1–11. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.8023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong W, Pan X-F, Yu C, et al. Self-rated health status and risk of ischemic heart disease in the China Kadoorie Biobank study: a population-based cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6. 10.1161/JAHA.117.006595. [Epub ahead of print: 22 Sep 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korhonen PE, Kautiainen H, Mäntyselkä P. Screening for cardiovascular risk factors and self-rated health in a community setting: a cross-sectional study in Finland. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e611–5. 10.3399/bjgp14X681769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lekander M, Elofsson S, Neve I-M, et al. Self-rated health is related to levels of circulating cytokines. Psychosom Med 2004;66:559–63. 10.1097/01.psy.0000130491.95823.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarczok MN, Kleber ME, Koenig J, et al. Investigating the associations of self-rated health: heart rate variability is more strongly associated than inflammatory and other frequently used biomarkers in a cross sectional occupational sample. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117196–19. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kananen L, Enroth L, Raitanen J, et al. Self-rated health in individuals with and without disease is associated with multiple biomarkers representing multiple biological domains. Sci Rep 2021;11:1–14. 10.1038/s41598-021-85668-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y-T, Lai J-Z, Zhai F-F, et al. Right ventricular systolic function is associated with health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study in community-dwelling populations. Ann Transl Med 2021;9:640. 10.21037/atm-20-6845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutledge T, Linke SE, Johnson BD, et al. Self-rated versus objective health indicators as predictors of major cardiovascular events: the NHLBI-sponsored women's ischemia syndrome evaluation. Psychosom Med 2010;72:549–55. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dc0259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Mendonça Freire L, Dalamaria T, de Aquino Cunha M, et al. Self-rated health in university students from Rio Branco in the Western Brazilian Amazon. Health 2014;06:2245–9. 10.4236/health.2014.616260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt M. Predictors of self-rated health and lifestyle behaviours in Swedish university students. Glob J Health Sci 2012;4:1–14. 10.5539/gjhs.v4n4p1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shadbolt B. Some correlates of self-rated health. Am J Public Health 1997;87:951–60. 10.2105/ajph.87.6.951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, ten Haaf ME, et al. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis 2015;241:211–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salomon JA, Tandon A, Murray CJL. Comparability of self rated health: cross sectional multi-country survey using anchoring vignettes. BMJ 2004;328:258–61. 10.1136/bmj.37963.691632.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menezes RdeM, Andrade MV, Noronha KVMdeS, et al. EQ-5D-3L as a health measure of Brazilian adult population. Qual Life Res 2015;24:2761–76. 10.1007/s11136-015-0994-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marinho F, de Azeredo Passos VM, Carvalho Malta D, et al. Burden of disease in Brazil, 1990-2016: a systematic subnational analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2018;392:760–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31221-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May M, Lawlor DA, Brindle P, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment in older women: can we improve on Framingham? British women's heart and health prospective cohort study. Heart 2006;92:1396–401. 10.1136/hrt.2005.085381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denman CA, Bell ML, Cornejo E, et al. Changes in health behaviors and self-rated health of participants in meta Salud: a primary prevention intervention of ncd in Mexico. Glob Heart 2015;10:55–61. 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFadden E, Luben R, Wareham N, et al. Occupational social class, risk factors and cardiovascular disease incidence in men and women: a prospective study in the European prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:449–58. 10.1007/s10654-008-9262-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaplan GA, Keil JE, Factors S. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation 1993;88:1973–98. 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058277supp001.pdf (186.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.