Abstract

Objectives

To determine death occurrences of Puerto Ricans on the mainland USA following the arrival of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico in September 2017.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Participants

Persons of Puerto Rican origin on the mainland USA.

Exposures

Hurricane Maria.

Main outcome

We use an interrupted time series design to analyse all-cause mortality of Puerto Ricans in the USA following the hurricane. Hispanic origin data from the National Vital Statistics System and from the Public Use Microdata Sample of the American Community Survey are used to estimate monthly origin-specific mortality rates for the period 2012–2018. We estimated log-linear regressions of monthly deaths of persons of Puerto Rican origin by age group, gender, and educational attainment.

Results

We found an increase in mortality for persons of Puerto Rican origin during the 6-month period following the hurricane (October 2017 through March 2018), suggesting that deaths among these persons were 3.7% (95% CI 0.025 to 0.049) higher than would have otherwise been expected. In absolute terms, we estimated 514 excess deaths (95% CI 346 to 681) of persons of Puerto Rican origin that occurred on the mainland USA, concentrated in those aged 65 years or older.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest an undercounting of previous deaths as a result of the hurricane due to the systematic effects on the displaced and resident populations in the mainland USA. Displaced populations are frequently overlooked in disaster relief and subsequent research. Ignoring these populations provides an incomplete understanding of the damages and loss of life.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, International health services, Health & safety, Health economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

One of the first studies to examine excess mortality among migrant and displaced populations following a natural disaster.

Leverage comparison group mortality outcomes to control for seasonality and period-specific effects, minimising potential confounding.

As the mortality outcomes are aggregated at the Hispanic group and gender–age group stratum in each month, we are unable to precisely measure cause-specific mortality.

Our analysis does not allow us to disentangle the excess mortality of displaced populations as opposed to longer-term migrants or second or third-generation individuals of such ancestry.

Introduction

Extreme weather events such as hurricanes are growing in frequency and magnitude and are expected to affect a growing population due to migration patterns, ecosystem alteration and climate.1 2 The consequences for human lives and the economic costs associated with these disasters are high.3 4 While much research documents the direct impacts of natural disasters on the mortality, morbidity, and socioeconomic consequences of populations in affected areas, substantially less attention has been paid to the consequences for populations displaced as a result of these events.3 5 6

While all victims of natural disasters face common challenges, displaced populations undergo distinct experiences that are specific to their relocation—such as additional psychological stressors and disruption in access to healthcare services as well as changes in their living conditions and social networks; see Uscher-Pines and Frankenberg et al for systematic reviews of the literatures on the health effects of relocation following disaster and of the demographic consequences of disasters more generally.7 8 These circumstances can either compound or mitigate the effects of disasters for these populations. Consistent with the heterogeneity in the populations’ experiences, a growing body of research finds mixed evidence regarding the incidence and extent of higher mortality risk among displaced populations. In an early systematic review of the literature, Uscher-Pines documents neither short-term nor long-term consequences on mortality for displaced populations following postdisaster relocation.8 Subsequent studies find higher mortality risks for specific displaced subpopulations such as among relocated institutionalised elderly; see Willoughby et al for a systematic review.9

However, measuring the mortality consequences of disasters among these populations is inherently challenging due to the displacement that can take place before, during, or in the aftermath of an event. Most data on disasters are obtained from those who remain relatively near the site of the disaster or who have relocated to obvious camps and refugee settlements. The mortality of the rest of the displaced population may be missed if proper attention is not taken in the design of data collection efforts. Furthermore, displacement makes it difficult to know how completely those interviewed represent the underlying population exposed to the event, nor is it possible to benchmark respondents’ experiences during and after an event against their circumstances before the event, or against populations that were not exposed to the event but are otherwise similar.6 10 Few studies of displaced populations have analysed representative sample data before and after exposure to a disaster relative to comparable populations to be able to credibly measure the effects of these events. Specifically, studies of populations after large-scale disasters typically describe the experiences of particular groups of individuals—such as those displaced to specialised refugee locations—providing little information about individuals who settled elsewhere, although there are exceptions.6 7 10–16 In spite of these methodological limitations, this literature has shaped our understanding of mortality patterns among displaced populations. If conclusions about these forms of vulnerability do not transcend specific groups and cannot be replicated more generally, their informativeness in planning for or responding to the needs of at-risk populations—monitoring, assessment, programming of interventions, and the targeting of social safety nets—is compromised.

In this article, we contribute to research on the mortality consequences of extreme environmental hazards among displaced populations in host communities. We conceptualise postdisaster mobility as a coping strategy that occurs along a spectrum from forced displacement to largely voluntary migration.6 17–19 Our objective is to estimate the excess mortality experienced by Puerto Ricans in the mainland USA, following the devastation caused in Puerto Rico by Hurricanes Irma and Maria in September 2017. The consensus from existing research documenting excess mortality in the aftermath of the hurricanes—based on death occurrences that happened physically in the archipelago of Puerto Rico—is that well over one thousand people died in Puerto Rico and likely more than three thousand lost their lives (see online supplemental materials table A1).20–24 However, to date, no systematic attempt had been made to consider deaths that may have occurred on the mainland USA as a result of this natural disaster. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly examine the postdisaster death occurrences of Puerto Ricans in the mainland USA.

bmjopen-2021-058315supp001.pdf (440.3KB, pdf)

We combine administrative death records data from the US National Vital Statistics System together with population estimates using repeated cross sections of the Public Use Microdata Sample of the American Community Survey (ACS) to estimate monthly immigrant-origin group-specific mortality rates by age, gender, and educational attainment for the period 2012–2018 in the mainland USA. Using these data, which are representative of the at-risk population, we conduct analyses that measure outcomes consistently for individuals from the group affected by the disaster relative to those of comparable populations. We use an interrupted time series difference-in-differences design to examine patterns of all-cause mortality of Puerto Ricans in the USA during the months following the hurricane, using mortality trends for Cuban and Mexican populations in the mainland USA—whose countries of origin or ancestry were not affected by extreme hurricanes that year (or limited population displacement to the USA as a result of these events) and who had historically similar mortality trends preceding the event—as a comparison group.

Identifying the existence and magnitude of a period of excess mortality among Puerto Ricans in the USA in the months following the passage of Hurricane Maria over Puerto Rico would support the hypothesis that displaced and migrant populations also face a higher risk of mortality and possibly other health consequences from exposure to such natural disasters.

Methods

Data and descriptive statistics

We use publicly available microdata from the National Vital Statistics System of the National Center for Health Statistics to identify deaths of persons of Puerto Rican origin on the mainland USA between 2012 and 2018.25 The data also allow us to identify deaths of persons of other Hispanic origins, which we use as a comparison group. It also includes the month of occurrence, as well as several socioeconomic variables for each death, including the person’s age, gender, and educational attainment.

We use the Public Use Microdata Sample of the ACS of the US Census Bureau to estimate the annual population of each Hispanic origin, for each age group, gender, and educational attainment between 2012 and 2018.26 Following Santos-Burgoa et al, age was categorised in three groups: 0–39 years, 40–64 years and 65 years or older.20 For age groups 40–64 years and 65 years and older, we also stratified the sample in three groups based on individuals’ educational attainment: persons who did not complete high school, those with only a high school degree, and those with some higher education or more.

We employ a standard temporal disaggregation method for time series data based on dynamic models to generate stratum-specific population measures for each month.27 28 The technique exploits the time series relationship of the available low-frequency data using a regression model with autocorrelated errors generated by a first-order autoregressive process. The reference period of the ACS is the 12-month calendar year. As a result, we also restrict the 12-month average population estimate to equal the annual ACS-based population estimate; see online supplemental materials for details.

Because these data are publicly available and deidentified, this study is considered to be research not involving human subjects as defined by US regulation (45 CFR 46.102[d]).

Patient and public involvement

No patients involved.

Statistical analysis

Our empirical strategy consists of an interrupted time series/difference-in-differences design. We compare differences in the gender-by-age group stratum mortality rates of Puerto Ricans before and after September 2017 relative to that of Cubans and Mexicans, comparable Hispanic groups in the USA, during January 2012 to December 2018 time period. In doing so, we effectively use the mortality outcomes of the comparison groups to control for seasonality and period-specific effects. We make these comparisons by gender-by-age group, estimating a system of six (6) linear models of the form:

| (1) |

where dsgmt is the number of deaths of individuals from gender–age group stratum s and Hispanic group g in month m and year t; Mariamt is an indicator variable for the 6-month period from October 2017 to March 2018; PRsg is an indicator variable for Puerto Rican origin; Popsgmt is the population level estimate for each Hispanic group g over time; αsg are Hispanic group fixed effects; γmt are month-by-year fixed effects; and εsgmt is the error term. This model richly captures seasonality as well as other time trends for each gender-by-age stratum, and accounts for differences in the mortality rate levels between Puerto Ricans and other Hispanic groups. We estimate the models as a system of equations allowing for autocorrelation of the error terms by clustering standard errors at the Hispanic group level.29–31 This procedure also allows us to account for the correlation of mortality rates across age groups and gender within each Hispanic group as well as the autocorrelation of mortality for each group, and to generate estimates of aggregate excess mortality for the population based on the stratum-specific models.

We also report a series of estimates from an event study to document the month-specific effects of the Maria shock. Specifically, we estimate equation 2 to explore this:

| (2) |

where I{g=PRg} ∙ I{t=1,2,…,6} is a vector capturing the interaction of the PR indicator with an indicator variable for each month from October 2017 to March 2018, with September 2017—the month of the event—as the base period. All other variables are as defined above in equation 1. The vector θst captures the period-specific effects for each month during the 6-month window described earlier.

Our estimation procedure uses the observed age group-by-gender-specific deaths that occurred over the period of October 2017 until March 2018 as well as our estimated coefficients of the differential change in mortality rates of Puerto Ricans in the mainland USA (θs, θst), to construct estimates of excess mortality for each age group–sex combination and their corresponding 95% CI. We follow an analogous procedure to generate estimates of excess mortality for the population in overall terms. See online supplemental materials for details of the estimation and aggregation procedures.

An important consideration in this analysis is our need to estimate the degree of population displacement of the residents of Puerto Rico to the mainland USA following the hurricanes. We do so by measuring differential changes in population levels for the Puerto Rican population in the mainland USA relative to trends for the comparison groups throughout the period following the hurricanes. This methodology, described in more detail in the online supplemental materials, generates estimates of population displacement, or the population in excess of what would have otherwise been expected. This procedure allows us to both confirm independent estimates of population movements from the territory to the mainland USA during this period and to give confidence to the use of population estimates for the estimation of excess mortality rates.

Results

Overall, 14 010 individuals of Puerto Rican background died in the mainland USA between October 2017 and March 2018 (table 1); 7505 (53.6%) were men and 6505 (46.4%) were women (table 2); 9045 (64.6%) were adults aged 65 years or older (table 3). In contrast, between 10 866 and 12 832 deaths occurred among this population in the 6-month period between October and March in 2012–2013 to 2016–2017 years, the period of observation before the hurricane. We estimated that there were approximately 5.631 million individuals of Puerto Rican origin in the mainland USA in August 2017, and by March 2018, this number was 5.783 million—an increase of approximately 152 000 individuals, or a 2.7% population increase (table 1).

Table 1.

Excess Mortality of the Puerto Rican population in the mainland USA, overall and by month (October 2017 to March 2018)

| Observed deaths (1) | Δ mortality rate (95% CI) (2) | Population (100 000s) (3) | Expected deaths (4) | Excess deaths (95% CI) (5) | Ratio of observed to expected mortality (95% CI) (6) | |

| Panel A: month-specific estimates | ||||||

| October 2017 | 2093 | 0.022 | 56.596 | 2047 | 46 | 1.02 |

| (−0.006 to 0.051) | (−11.7 to 104.1) | (0.99 to 1.05) | ||||

| November 2017 | 2182 | 0.059 | 56.767 | 2056 | 126 | 1.06 |

| (0.041 to 0.078) | (87.1 to 164.7) | (1.04 to 1.08) | ||||

| December 2017 | 2551 | 0.065 | 56.974 | 2391 | 160 | 1.07 |

| (0.048 to 0.082) | (119.4 to 200.7) | (1.05 to 1.09) | ||||

| January 2018 | 2624 | 0.012 | 57.524 | 2592 | 32 | 1.01 |

| (−0.014 to 0.039) | (−36.1 to 100.5) | (0.99 to 1.04) | ||||

| February 2018 | 2275 | 0.059 | 57.708 | 2145 | 130 | 1.06 |

| (0.035 to 0.083) | (78.1 to 182.4) | (1.03 to 1.09) | ||||

| March 2018 | 2285 | 0.004 | 57.830 | 2276 | 9 | 1.00 |

| (−0.008 to 0.016) | (−19.1 to 36.8) | (0.99 to 1.02) | ||||

| Panel B: aggregate estimates | ||||||

| October 2017 to March 2018 | 14 010 | 0.037 | 57.233 | 13 496 | 514 | 1.04 |

| (0.025 to 0.050) | (346.5 to 681.0) | (1.03 to 1.05) | ||||

| October 2017 to December 2017 | 6826 | 0.037 | 56.779 | 6581 | 245 | 1.04 |

| (0.024 to 0.049) | (163.6 to 326.9) | (1.02 to 1.05) | ||||

Column 1 reports observed deaths of the Puerto Rican population in the mainland USA, and column 3 reports estimates of the overall population of Puerto Ricans in the mainland. Column 2 reports estimates of the difference in the natural logarithm of the mortality of Puerto Ricans relative to Cubans and Mexicans based on the aggregation of estimates from equation 2 (panel A) and equation 1 (panel B) estimated for each gender-by-age group, as well as 95% CIs in parentheses. Columns 4, 5 and 6 respectively report estimates of expected deaths, excess deaths and the ratio of observed to expected deaths calculated from observed deaths (column 1) and estimates of changes in mortality rates (column 2); 95% CIs of the level of excess deaths and of the ratio of observed to expected deaths are reported in parentheses.

Table 2.

Excess mortality of the Puerto Rican population in the mainland USA, by age group and sex (October 2017 to March 2018)

| Observed deaths (1) | Δ mortality rate (95% CI) (2) | Population (100 000s) (3) | Expected deaths (4) | Excess deaths (95% CI) (5) | Ratio of observed to expected mortality (95% CI) (6) | |

| Panel A: 0–39 years of age | ||||||

| Men | 936 | −0.023 | 18.782 | 957.6 | −22 | 0.98 |

| (−0.026 to –0.019) | (−23 to –20) | (0.98 to 0.98) | ||||

| Women | 433 | 0.011 | 17.635 | 428.2 | 5 | 1.01 |

| (−0.106 to 0.129) | (−18 to 28) | (0.96 to 1.07) | ||||

| Panel B: 40–64 years of age | ||||||

| Men | 2320 | −0.005 | 7.626 | 2332.5 | −12 | 0.99 |

| (−0.016 to 0.005) | (−24 to –1) | (0.99 to 1.00) | ||||

| Women | 1276 | −0.041 | 7.967 | 1329.1 | −53 | 0.96 |

| (−0.086 to 0.004) | (−80 to –26) | (0.94 to 0.98) | ||||

| Panel C: ≥65 years of age | ||||||

| Men | 4249 | 0.073 | 2.222 | 3950.9 | 298 | 1.08 |

| (0.008 to 0.137) | (182 to 414) | (1.04 to 1.11) | ||||

| Women | 4796 | 0.064 | 3.002 | 4498.0 | 298 | 1.07 |

| (0.041 to 0.088) | (250 to 346) | (1.05 to 1.08) | ||||

| Panel D: all | ||||||

| Men | 7505 | 0.036 | 28.630 | 7241.0 | 264 | 1.04 |

| (0.022 to 0.050) | (162 to 366) | (1.02 to 1.05) | ||||

| Women | 6505 | 0.039 | 28.604 | 6255.0 | 250 | 1.04 |

| (0.028 to 0.050) | (179 to 320) | (1.03 to 1.05) |

Column 1 reports observed deaths of the Puerto Rican population by gender and age group in the mainland USA, and column 3 reports estimates of the overall population of the respective group of Puerto Ricans in the mainland. Column 2 reports estimates of the difference in the natural logarithm of the mortality of Puerto Ricans relative to Cubans and Mexicans based on the aggregation of estimates from equation 1 estimated for each gender-by-age group, as well as 95% CIs in parentheses. Columns 4, 5 and 6 respectively report estimates of expected deaths, excess deaths and the ratio of observed to expected deaths calculated from observed deaths (column 1) and estimates of changes in mortality rates (column 2); 95% CIs of the level of excess deaths and of the ratio of observed to expected deaths are reported in parentheses.

Table 3.

Excess mortality of the Puerto Rican population ages 65 and older in the mainland USA, by education group and sex (October 2017 to March 2018)

| Observed deaths (1) | Δ mortality rate (95% CI) (2) | Population (100 000’s) (3) | Expected deaths (4) | Excess deaths (95% CI) (5) | Ratio of observed to expected mortality (95% CI) (6) | |

| Panel A: 65+ years of age, high school dropouts | ||||||

| Men | 1802 | 0.121 | 0.911 | 1597 | 205 | 1.13 |

| (−0.110 to 0.352) | (37 to 373) | (1.01 to 1.25) | ||||

| Women | 2232 | 0.115 | 1.168 | 1989 | 243 | 1.12 |

| (0.017 to 0.214) | (154 to 332) | (1.07 to 1.17) | ||||

| Panel B: 65+ years of age, high school graduates | ||||||

| Men | 1560 | 0.119 | 0.591 | 1385 | 175 | 1.13 |

| (0.044 to 0.195) | (127 to 223) | (1.09 to 1.17) | ||||

| Women | 1565 | 0.012 | 0.884 | 1546 | 19 | 1.01 |

| (−0.033 to 0.058) | (−13 to 51) | (0.99 to 1.03) | ||||

| Panel C: 65+ years of age, some college or more | ||||||

| Men | 774 | 0.082 | 0.700 | 712.8 | 61 | 1.09 |

| (0.015 to 0.150) | (39 to 83) | (1.05 to 1.12) | ||||

| Women | 896 | 0.121 | 0.929 | 794.2 | 102 | 1.13 |

| (0.087 to 0.155) | (89 to 114) | (1.11 to 1.15) | ||||

Column 1 reports observed deaths of the Puerto Rican population by gender, age and education group in the mainland USA, and column 3 reports estimates of the overall population of the respective group of Puerto Ricans in the mainland. Column 2 reports estimates of the difference in the natural logarithm of the mortality of Puerto Ricans relative to Cubans and Mexicans based on the aggregation of estimates from equation 1 estimated for each gender-by-age-by-education group, as well as 95% CIs in parentheses. Columns 4, 5 and 6 respectively report estimates of expected deaths, excess deaths and the ratio of observed to expected deaths calculated from observed deaths (column 1) and estimates of changes in mortality rates (column 2); 95% CIs of the level of excess deaths and of the ratio of observed to expected deaths are reported in parentheses.

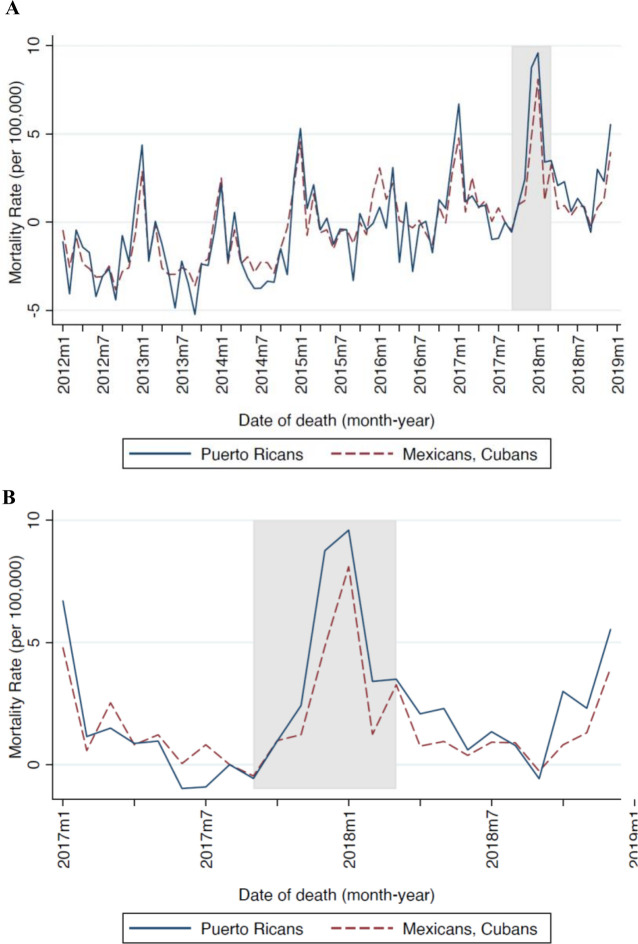

We compare mortality outcomes pre and post September 2017 among the Puerto Rican population in the mainland USA relative to other Hispanic groups in the country. In figure 1A, we examine trends in the overall mortality rate of Puerto Ricans in the mainland USA (blue solid line) during January 2012 to December 2018 and that of Cubans and Mexicans (red dashed line) throughout the same period. Between January of 2012 and August 2017, the mortality rate among individuals of Puerto Rican origin averaged 280.89 per 100 000. In contrast, the mortality rate among Cubans and Mexicans throughout this period was 232.17 per 100 000. In spite of this difference in mortality levels, the two groups experienced very similar mortality seasonal patterns and trends in the period up to September 2017, when Puerto Rico was severely affected by Hurricanes Irma and Maria (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Standardised monthly mortality from January 2012 to December 2018 (A) and from July 2017 to December 2018 (B). August 2017 is used as the standard mortality rate for both populations.

Following these events, we observe a modest trend break in the mortality rate of Puerto Ricans relative to that of Cubans and Mexicans, in the 0.08–4.03 deaths per 100 000 range (figure 1B). The figure helps validate the research design. In the online supplemental appendix, we include a series of placebo tests we performed to evaluate whether there are significant increases in mortality of the Puerto Rican population relative to that of the comparison group pre October 2017, which confirm the common trends assumption. Moreover, it reveals the mortality rate gap to be most pronounced during the October 2017 through March 2018; we use this post hurricane 6-month event window to capture estimates of excess mortality for the Puerto Rican population in the mainland USA.

Our results span the 6-month period following the passing of Hurricane Maria (October 2017 to March 2018). We find a statistically significant increase in the mortality rate for persons of Puerto Rican origin during this period of approximately 3.7% (95% CI 2.4% to 4.9%) higher than would have otherwise been expected (see table 1) (The results are robust to restricting the sample to start in later years (ie, 2013, 2014), but with somewhat lower levels of precision.). In absolute terms, this is equivalent to 514 excess deaths (95% CI 346 to 681) of persons of Puerto Rican origin that occurred on the mainland USA.

The month-specific estimates of the excess mortality increase gradually throughout the fourth quarter and peak at 6.5% (95% CI 4.8% to 8.2%) in December 2017 and fluctuate in a downward trajectory during the first quarter of year 2018 (table 1). These month-specific excess mortality rate estimates imply a pattern of excess death, starting just after the hurricanes in October 2017 with 46 excess deaths (95% CI −12 to 104), up to 160 (95% CI 119 to 201) in December 2017 and 9 (95% CI −19 to 37) in March 2018.

Table 2 reports estimates of excess mortality by age group and gender. Among the population aged 65 years or older, mortality was higher than the expected pattern for this population throughout the October 2017 to March 2018 period: 7.3% (95% CI 0.8% to 13.7%) for men and 6.4% (95% CI 4.1% to 8.8%) for women. This is equivalent to 298 excess deaths for men (95% CI 182 to 414) and the same amount for women (95% CI 250 to 346). When examining excess mortality by cause of death among this age group, we estimate these to be concentrated in deaths related to heart diseases, cancer and diabetes; see online supplemental materials for details.

We find no robust evidence of differences in mortality from the expected pattern for the younger age population throughout this period. The empirical models suggest mortality decreased marginally by 0.5% (95% CI −0.5% to 1.6%) and 4.1% (95% CI 0.4% to 8.6%) among, respectively, men and women aged 40–64 years and by 2.3% (95% CI 1.9% to 2.6%) among men aged 0–39 years.

The point estimates in table 3 suggest that populations from all educational levels were affected, but excess deaths were more evident in certain groups. For example, we found 243 excess deaths (95% CI 154 to 332) occurred among old age women with less than high school, 175 excess deaths (95% CI 127 to 223) among old age men with a high school diploma, and 61 (95% CI 39 to 83) and 102 (95% CI 89 to 114) excess deaths among old age men and women respectively with at least some higher education. We exclude deaths and population counts with missing educational attainment data from this particular analysis. Accordingly, excess mortality estimates for the group of individuals aged 65+ in table 3 do not sum to the estimates reported in panel C of table 2. Nevertheless, given the level of precision of our estimates, we cannot reject that these are in the same range.

Discussion

Main findings

Our study documents an increase in mortality for persons of Puerto Rican origin in the mainland USA during the 6-month period following Hurricane Maria (October 2017 through March 2018). Our findings indicate that measures of excess mortality based on death occurrences in Puerto Rico following the hurricane may be underestimating total excess mortality by an additional 514 deaths (95% CI 346 to 681) in the 6 months following the event, partly due to significant displacement of the Puerto Rican population to the mainland USA. Crucially, this increase in mortality was concentrated among the most vulnerable populations, with old age adults with lower levels of education seeing the largest increases. These patterns are consistent with excess mortality estimates obtained in Puerto Rico.23 24 Analyses of these data also provide a rich description of heterogeneity of the event’s impacts to yield generalisable knowledge.

Contribution, limitations and relationship to the literature

The study contributes to the literature documenting the mortality consequences of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Several previous attempts to estimate the mortality effects of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, including the official death toll estimate prepared by the Government of Puerto Rico, used Puerto Rico death registrar data and previous years’ mortality rate estimates as a benchmark to identify periods of excess mortality in Puerto Rico.20–24 Preferred mortality estimates for the 6-month and 7-month period following the disaster—which considered only deaths registered in Puerto Rico despite significant population displacement and excluding deaths among the population displaced to the mainland—were as high as 2975 and 3400, respectively.20 23 We present a summary of the data, techniques and treatment periods employed in this research in the online supplemental file 1. This focus on deaths occurring in the territory resulted in an underestimation of the death toll by approximately 14.7%, which we estimate occurred in the USA. In contrast, Kishore et al (2018) surveyed a representative sample of households, asking survivors to account for the whereabouts of all people who lived in their community prior to the hurricane irrespective of the location of the occurrences of death among community members (on the island or elsewhere).32 Accordingly, they found a mortality rate that yielded an estimate of 4645 excess deaths (95% CI 793 to 8498) on account of Hurricane Maria. Our finding of excess mortality among the population of Puerto Rican origin in the mainland USA contributes to explaining the difference in estimates from these two methodological approaches.

An additional contribution of the study is the use of a research design to credibly estimate the excess mortality of displaced and migrant populations during this period, while carefully accounting for population displacement following the disaster. Using comparator populations of Cubans and Mexicans in the mainland USA, our design robustly accounts for different population and mortality trends by age group and gender to account for both displacement and differential mortality among the Puerto Rican population. Our estimates of displacement of the population ages 65 and older of approximately 7.1% (40 700 individuals) is in line with the existing literature and supports the consensus using other methodologies that the natural disaster led to displacement in aggregate terms of approximately 4.1%–5.6% of the total population of Puerto Rico.33 34 This design, effectively used in related studies and other contexts to account for population movements, is broadly applicable both in other countries and in other disaster contexts (both natural and otherwise), particularly as displacement and mobility becomes an increasingly important feature of natural disasters.11

Our study is informative regarding the broad mortality consequences of the disaster among the displaced and migrant population of Puerto Ricans in the USA. This measure, however, limits our ability to quantify the elevated burden of disease from morbidity and disability among this population. We also face some limitations in our ability to precisely estimate cause-specific mortality or the causal pathways for such trends. Given the relatively small numbers of deaths in the population in the period under observation (monthly range 2119–2862), generating informative estimates of more finely defined cause-specific mortality is not feasible.

Finally, because we use the deaths of persons who are identified as Puerto Rican in their death certificate, our analysis does not allow us to disentangle the excess mortality of displaced populations as opposed to longer-term migrants or second or third-generation individuals of such ancestry. Information on the deaths of Puerto Rico residents in the continental USA may be incomplete and/or prone to undercounting if the Puerto Rico residency status of such individuals is under-reported on death certificates. This phenomenon is particularly exacerbated among vulnerable, geographically mobile, migrant populations (Our estimate also excludes persons exposed to the hurricane, who may have been displaced to other countries, most notably the neighbouring Dominican Republic. While not directly exposed, it is possible that longer-term migrants may have been psychologically or economically affected by the events in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, which may also have affected their mortality risk. At the same time, this approach excludes from the analysis individuals who are not of Puerto Rican origin but who nevertheless may have been in Puerto Rico at the time of hurricane, and who may have been displaced in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.). Nonetheless, the fact our estimated effects are concentrated among vulnerable populations—consistent with the excess mortality estimates obtained for death occurrences in Puerto Rico—supports the view that we mainly capture excess deaths among the sizeable population that was displaced to the mainland USA following the natural disaster. Future research could undertake epidemiological studies with microlevel data to precisely estimate cause-specific mortality, the causal pathways for such patterns, as well as mortality estimates that include all hurricane-related deaths according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for death occurrences in Puerto Rico and in the continental USA.

Policy implications

Our study emphasises the importance of considering displaced populations in the calculation of postdisaster excess mortality. These populations may suffer from relative inattention in the context of both needs assessment and disaster relief, and we argue that overlooking these provide an incomplete understanding of the magnitude of the health consequences of natural disasters.

This analysis suggests the need for not only equitable disaster preparedness but also the importance of cross-jurisdiction data sharing.20 These already vulnerable populations may face a number of additional hurdles on relocation, such as healthcare disruptions and psychological stressors, which may exacerbate health impacts of the disaster. Receiving jurisdictions would, thus, benefit from an improved understanding of both the dynamics of postdisaster displacement and its consequences.

Already important efforts exist among jurisdictions in the USA, such as the State and Territorial Exchange of Vital Events of the National Association for Public Health Statistics Information Systems, to facilitate vital records for use by other state-level and territorial public health organisations. However, more coordination is required to speed the flow of data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the scale of disasters in other countries. Moreover, even among jurisdictions within the USA, this process can take a considerable amount of time. The speed of flow of vital records depends on the effectiveness of local and county vital registrars to share this information. Ensuring timely exchange of death records among jurisdictions would ensure disaster death toll estimates based on vital records are complete, and would hence allow public authorities to have a comprehensive understanding of the scale of the disaster in a timely fashion.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MM: conceptualisation, data curation, supervision, validation, visualisation, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing. BM: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualisation, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing. GJB: conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualisation, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing, guarantor for the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data relevant to the study are publicly available (and detailed in the article and supplementary materials).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Iwan WD, Cluff LS, Kimpel JF. Mitigation emerges as major strategy for reducing losses caused by natural disasters. board of natural disasters. Science 1999;284:1943–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stocker TF D, Qin G-K, Plattner MT. IPCC, 2013: summary for policymakers. in: climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourque LB, Siegel JM, Kano M, et al. Weathering the storm: the impact of Hurricanes on physical and mental health. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 2006;604:129–51. 10.1177/0002716205284920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kousky C. Informing climate adaptation: a review of the economic costs of natural disasters, their determinants, and risk reduction options. SSRN Electronic Journal 2012;79. 10.2139/ssrn.2099769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol Rev 2005;27:78–91. 10.1093/epirev/mxi003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray C, Frankenberg E, Gillespie T, et al. Studying displacement after a disaster using large scale survey methods: Sumatra after the 2004 tsunami. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 2014;104:594–612. 10.1080/00045608.2014.892351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankenberg E, Laurito MM, Thomas D. Demographic Impact of Disasters. In: In: International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edn, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uscher-Pines L. Health effects of relocation following disaster: a systematic review of the literature. Disasters 2009;33:1–22. 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willoughby M, Kipsaina C, Ferrah N, et al. Mortality in nursing homes following emergency evacuation: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:664–70. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stallings RA. Methodological issues. In: Handbook of disaster research. Springer, 2007: 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groen JA, Polivka AE. Hurricane Katrina evacuees: who they are, where they are, and how they are faring. Monthly Labor Review 2008;131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halliday T. Migration, risk, and Liquidity constraints in El Salvador. Econ Dev Cult Change 2006;54:893–925. 10.1086/503584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankenberg E, Sumantri C, Thomas D. Effects of a natural disaster on mortality risks over the longer term. Nat Sustain 2020;3:614–9. 10.1038/s41893-020-0536-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen K, Landau LB. The dual imperative in refugee research: some methodological and ethical considerations in social science research on forced migration. Disasters 2003;27:185–206. 10.1111/1467-7717.00228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray C, Mueller V. Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Dev 2012;40:134–45. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray CL, Mueller V. Natural disasters and population mobility in Bangladesh. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:6000–5. 10.1073/pnas.1115944109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hugo G. Environmental concerns and international migration. Int Migr Rev 1996;30:105–31. 10.1177/019791839603000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter LM. Migration and environmental hazards. Popul Environ 2005;26:273–302. 10.1007/s11111-005-3343-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naik A. Chapter V: Migration and natural disasters. In: Migration, environment and climate change, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos-Burgoa C, Sandberg J, Suárez E, et al. Differential and persistent risk of excess mortality from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico: a time-series analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2:e478–88. 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30209-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivera R, Rolke W. Modeling excess deaths after a natural disaster with application to Hurricane Maria. Stat Med 2019;38:4545–54. 10.1002/sim.8314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos-Lozada AR, Howard JT. Use of death counts from vital statistics to calculate excess deaths in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria. JAMA 2018;320:1491. 10.1001/jama.2018.10929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acosta R, Irizarry R. Post-Hurricane Vital Statistics Expose Fragility of Puerto Rico’s Health System. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruz-Cano R, Mead EL. Causes of excess deaths in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria: a time-series estimation. Am J Public Health 2019;109:1050–2. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics . Mortality multiple cause files, 2012-2018. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_public_use_data.htm

- 26.United States Census Bureau . American community survey. Available: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/pums/

- 27.Chow GC, Lin A-loh, Lin A. Best linear unbiased interpolation, distribution, and extrapolation of time series by related series. Rev Econ Stat 1971;53:372. 10.2307/1928739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos Silva JMC, Cardoso FN. The Chow-Lin method using dynamic models. Econ Model 2001;18:269–80. 10.1016/S0264-9993(00)00039-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang K-YEE, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22. 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arellano M. Computing robust standard errors for Within-groups estimators. Oxford Bulletin of Economics & Statistics 1987;49. [Google Scholar]

- 31.White H. Asymptotic theory for Econometricians. Elsevier, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med 2018;379:162–70. 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Acosta RJ, Kishore N, Irizarry RA, et al. Quantifying the dynamics of migration after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:32772–8. 10.1073/pnas.2001671117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander M, Polimis K, Zagheni E. The impact of Hurricane Maria on Out‐migration from Puerto Rico: evidence from Facebook data. Popul Dev Rev 2019;45:617–30. 10.1111/padr.12289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058315supp001.pdf (440.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data relevant to the study are publicly available (and detailed in the article and supplementary materials).