Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) target two seminal negative feedback loops in T cells, which are in place to avoid overactivation and uncontrolled immune responses, including those against self-antigens: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death 1 pathway (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Reversing this break and enabling tumor-directed immune activity has remarkably improved survival rates for various malignancies, including those historically considered to have a very poor prognosis. Despite their proven efficacy across a wide range of malignancies, ICI can cause a unique spectrum of autoimmune toxicities known as immune-related adverse events (irAEs). These irAEs can affect virtually any organ, including the kidneys as ICI-associated AKI, and can emerge as therapy-limiting side effects for ICIs.

Patients with cancer who developed severe irAEs, Grade 3 or 4 by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, are at risk of developing these very same toxicities on rechallenging with ICIs (1). Understandably, the medical team in charge of these patients can be quite hesitant to rechallenge with ICI, even if a therapeutic benefit is seen. With the expanding use of ICI, the outlined problem will continue to become more frequent. ICI-associated AKI (ICI-AKI) occurs in 2%–5% of patients receiving immunotherapy, but the incidence differs depending on the agent administered and the dose of the agent, with the highest incidences reported for anti–CTLA-4/anti–PD-1/PD-L1 combination therapy (2,3). Among ICI-AKIs, acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is the most common pathologic finding and it tends to respond quite promptly in the majority of patients by withholding ICI therapy and timely administration of corticosteroids. Rechallenge with ICI becomes a point of discussion for the multidisciplinary care team at the point resolution of AKI, weighing the risks and benefits. Initially, in clinical trials, when patients developed severe toxicity, resumption of ICI therapy was usually not allowed if disease progressed. As these drugs became more broadly available in real-world scenarios, centers with more experience learned to identify and manage ICI-AKI with declining fear of rechallenge, especially when an alternative anticancer therapy is not available. There are a few relevant studies that have looked at rechallenging patients who developed ICI-AKI (Table 1). One of the first studies was performed by our group, a retrospective observational cohort study of 1173 patients included 14 who were deemed to have ICI-AKI and four who underwent rechallenge (4). This study was further extended by Isik et al., who reported on 37 patients who developed ICI-AKI (6). All of them had their ICI therapy held and 92% were treated with corticosteroids. Rechallenge was attempted in 16 (43%) of the 37 patients approximately 2 months after the AKI event. Of these patients 15 (97%) were rechallenged with the same ICI agent (PD-1 inhibitor) implicated in the initial AKI episode, and in three (20%) patients, nivolumab ICI therapy was reduced from combination therapy with ipilimumab to monotherapy. There was only one (6%) patient who switched drugs (pembrolizumab to atezolizumab). A total of 13 (81%) patients were on corticosteroids at rechallenge. Recurrent ICI-AKI occurred in three (19%) of the rechallenged patients, and there was no difference of latency period between the initial AKI episode and rechallenge between those who developed recurrent AKI and those who did not. Because use of AIN-inducible drugs, such as proton pump inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, have been implicated in the increased risk of developing ICI-AKI (5), we looked at AIN drug subtype at rechallenge. No significant difference was found in patients with recurrent AKI and those without recurrent AKI, and there was no difference in the dose of corticosteroids (6).

Table 1.

Relevant retrospective studies evaluating kidney immune-related adverse events after immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge

| Study | No. of Patients with Initial Kidney Immune-Related Adverse Events | Number of Patients Rechallenged | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment Rotation | % of Patients on Immunosuppression at the Time of Rechallenge | % of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Acute Kidney Injury Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isik et al. (6) | 16 | Combination to anti–PD-1 Anti–PD-1 to same Anti–PD-1 to anti–PD-L1 |

81% |

n=3 (19%) 33% stage 1 33% stage 2 33% stage 3 |

|

| Cortazar et al. (7) | 138 Stage 3 (57%) Stage 2 (43%) |

31 | Most patients were rechallenged with the same ICI agent. Mostly anti–PD-1 | 39% |

n=7 (23%) 29% stage 3 71% stage ≤2 |

| Dolladille et al. (1) | 276 Stage N/A |

78 | Informative rechallenges mostly done with an anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy | N/A |

n=4 (5.1%) stage N/A |

| Hultin et al. (12) | 23 Average creatinine at peak 3.8 mg/dl |

5 | Four received anti–PD-1 monotherapy One patient received single anti– CTLA-4 |

60% (40% N/A) |

No recurrence of renal irAE |

| Espi et al. (9) | 13 Stage 1 (43%) Stage 2 (36%) Stage 3 (21%) |

5 | All patients were rechallenged with the same ICI all anti–PD-1 | 20% | n=1 (20%) stage 2 |

Acute kidney injury stage according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes clinical practice guidelines: 1.5–1.9 fold from baseline serum creatinine (SCr) (AKI stage 1); 2–2.9 fold from baseline SCr (AKI stage 2); and over threefold from baseline SCr (AKI stage 3). PD-1, programmed death 1 pathway; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; irAE, immune-related adverse event.

The above study findings were corroborated in a larger multicentre retrospective study by Cortazar et al. In this multicenter study with a total of 138 patients with ICI-AKI, 31 (22%) patients were rechallenged approximately 1.8 months after the diagnosis of ICI-AKI. Recurrence of ICI-AKI was noted in seven patients (23%). Most patients (85%) had partial or complete response after treatment. Like other studies discussed previously, most of the patients (87%) were rechallenged with the same ICI treatment received at initial AKI episode, and around 40% were still treated with corticosteroids at the time of rechallenge (7).

On the basis of the results of the studies performed to date, rechallenge is feasible and associated with a risk of recurrent ICI-AKI of approximately 20%. Importantly, Isik et al. did not find survival differences between patients rechallenged versus those who were not rechallenged with ICI therapy (6). An explanation for these results could be related to potential bias toward treating patients with more aggressive malignancies with ICI, again due to lack of an alternative treatment with other conventional therapies and potentially decreasing survival benefit. Given the relative low incidence of recurrent ICI-AKI, it seems reasonable to consider rechallenge in patients who present with tumor treatment response when on immunotherapy.

Therefore, the decision on whether to rechallenge patients after an episode of ICI-AKI will depend on a variety of considerations. These including the severity of renal irAE and if other risk factors were present at the time of development of ICI-AKI, such as use of ICI combination therapy or the use of AIN-inducible drugs, as these can be discontinued. Although robust evidence is lacking, clinicians may consider secondary prevention by use of corticosteroids when there is absence of other therapeutic alternatives, even for patients with more severe kidney toxicities such as Grade 3 or higher.

With all these factors in mind, there are few scenarios where rechallenge can be feasible and ICI therapy can be resumed as safely as possible, and independent of the severity of the initial renal irAE, once partial response or complete response is accomplished with immunosuppression therapy.

Rechallenge with Switching of the Class of ICI Therapy

For the patients who developed irAE and responded to ICI therapy, one alternative is to consider switching ICI classes, but only when appropriated after discussion with oncological team, because some ICI classes may not be approved for the specific type of cancer. Some organs seem to be affected by one class more than by another. Patients on anti–CTLA-4 agents may experience more colitis and hypophysitis, whereas patients on PD-1 blockade may develop more pneumonitis. One study reported an incidence of ICI-AKI of <1% with PD-L1 blockade, compared with an incidence of 2%–5% with other classes (2,8). This may be due to the lack of impairment of the PD-1/PD-L2 pathway. This approach can henceforth be considered in a number of patients, especially in the hands of an experienced team and in the absence of other available treatment options.

Rechallenge Using the Same Class of ICI Therapy

The use of combination ICI therapy increases the risk of ICI-AKI, therefore rechallenge with de-escalation to monotherapy is recommended in this setting. Often, anti–CTLA-4 therapy is discontinued, and anti–PD-1 monotherapy is resumed. As shown in the outlined retrospective studies, rechallenge is mostly done with the same ICI, and recurrence of ICI-AKI occurred in one in five patients in most of the studies. Close monitoring remains important in all patients undergoing rechallenge for early detection of AKI so that severe AKI events could be avoided.

Rechallenge with ICI Therapy Concomitantly or without Immunosuppressive Therapy

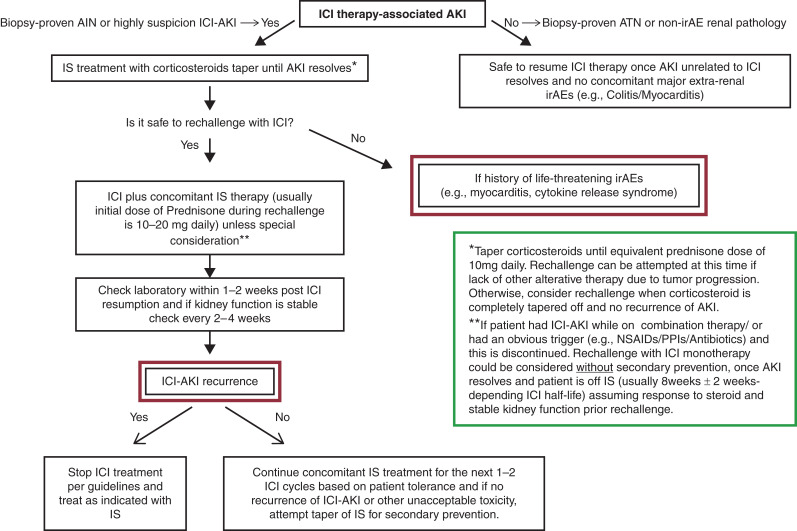

Concomitantly immunosuppressive therapy is a common scenario, as outlined in the aforementioned retrospective studies. After the initial episode of ICI-AKI, immunotherapy is resumed after AKI resolution concomitantly with low-dose steroids (usually 10–20 mg daily depending on other factors such as severity of AKI and concomitant extra renal irAEs), this secondary prevention can be maintained for the first month or cycle 1–2 after resumption ICI therapy before attempting tapering; recurrence of ICI-AKI in this setting is seen in 5%–25% (4,6,7,9). Although counterintuitive, the concomitant administration of corticosteroids and ICI therapy does not necessarily lead to poorer clinical cancer outcomes (10). Data supporting secondary prevention with corticosteroids are not as robust yet, but corticosteroids can be considerate in conjunction with ICI in the absence of other therapeutic alternatives. On the contrary, observations have shown that for some patients after resolution of ICI-AKI, once potential culprit drug (e.g., proton pump inhibitors/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) at the time of development of ICI-AKI is discontinued, these patients may not require secondary prevention with immunosuppression if kidney function remains is stable. Figure 1 shows a proposed algorithm for secondary prevention of ICI-AKI during rechallenge after thorough multidisciplinary discussion.

Figure 1.

Proposed flow chart approach for secondary prevention during immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after initial nephrotoxicity. IrAE, immune-related adverse event; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IS, immunosuppression; ATN, acute tubular necrosis; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

It is important to note the correlation of development of irAE and response to therapy has been consistently reported in different types of cancer (11). Given the reasonable risk profile, the benefit of resuming ICI therapy in selected patients despite initial nephrotoxicity can be quite attractive, and should be considered, especially when it is the only therapy option left.

Disclosures

S.M. Herrmann reports having patents and inventions with Pfizer, not related to this research.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK118120 and by a Mary Kathryn and Michael B. Panitch Career Development Award.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or Kidney360. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

S.M. Herrmann conceptualized the study, wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dolladille C, Ederhy S, Sassier M, Cautela J, Thuny F, Cohen AA, Fedrizzi S, Chrétien B, Da-Silva A, Plane AF, Legallois D, Milliez PU, Lelong-Boulouard V, Alexandre J: Immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 6: 865–871, 2020. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrmann SM, Perazella MA: Immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune-related adverse renal events. Kidney Int Rep 5: 1139–1148, 2020. 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortazar FB, Marrone KA, Troxell ML, Ralto KM, Hoenig MP, Brahmer JR, Le DT, Lipson EJ, Glezerman IG, Wolchok J, Cornell LD, Feldman P, Stokes MB, Zapata SA, Hodi FS, Ott PA, Yamashita M, Leaf DE: Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int 90: 638–647, 2016. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manohar S, Ghamrawi R, Chengappa M, Goksu BNB, Kottschade L, Finnes H, Dronca R, Leventakos K, Herrmann J, Herrmann SM: Acute interstitial nephritis and checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Kidney360 1: 16–24, 2020. 10.34067/KID.0000152019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seethapathy H, Zhao S, Chute DF, Zubiri L, Oppong Y, Strohbehn I, Cortazar FB, Leaf DE, Mooradian MJ, Villani AC, Sullivan RJ, Reynolds K, Sise ME: The incidence, causes, and risk factors of acute kidney injury in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1692–1700, 2019. 10.2215/CJN.00990119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isik B, Alexander MP, Manohar S, Vaughan L, Kottschade L, Markovic S, Lieske J, Kukla A, Leung N, Herrmann SM: Biomarkers, clinical features, and rechallenge for immune checkpoint inhibitor renal immune-related adverse events. Kidney Int Rep 6: 1022–1031, 2021. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortazar FB, Kibbelaar ZA, Glezerman IG, Abudayyeh A, Mamlouk O, Motwani SS, Murakami N, Herrmann SM, Manohar S, Shirali AC, Kitchlu A, Shirazian S, Assal A, Vijayan A, Renaghan AD, Ortiz-Melo DI, Rangarajan S, Malik AB, Hogan JJ, Dinh AR, Shin DS, Marrone KA, Mithani Z, Johnson DB, Hosseini A, Uprety D, Sharma S, Gupta S, Reynolds KL, Sise ME, Leaf DE: Clinical features and outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated AKI: A multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 435–446, 2020. 10.1681/ASN.2019070676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seethapathy H, Zhao S, Strohbehn IA, Lee M, Chute DF, Bates H, Molina GE, Zubiri L, Gupta S, Motwani S, Leaf DE, Sullivan RJ, Rahma O, Blumenthal KG, Villani AC, Reynolds KL, Sise ME: Incidence and clinical features of immune-related acute kidney injury in patients receiving programmed cell death ligand-1 inhibitors. Kidney Int Rep 5: 1700–1705, 2020. 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espi M, Teuma C, Novel-Catin E, Maillet D, Souquet PJ, Dalle S, Koppe L, Fouque D: Renal adverse effects of immune checkpoints inhibitors in clinical practice: ImmuNoTox study. Eur J Cancer 147: 29–39, 2021. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garant A, Guilbault C, Ekmekjian T, Greenwald Z, Murgoi P, Vuong T: Concomitant use of corticosteroids and immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with hematologic or solid neoplasms: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 120: 86–92, 2017. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das S, Johnson DB: Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 7: 306, 2019. 10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hultin S, Nahar K, Menzies AM, Long GV, Fernando SL, Atkinson V, Cebon J, Wong MG: Histological diagnosis of immune checkpoint inhibitor induced acute renal injury in patients with metastatic melanoma: A retrospective case series report. BMC Nephrol 21: 391, 2020. 10.1186/s12882-020-02044-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]