Resumo

Com o aumento da expectativa de vida da população e a maior frequência de fatores de risco como obesidade, hipertensão arterial e diabetes, espera-se um aumento na prevalência de insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção preservada (ICFEp). Entretanto, no momento, o diagnóstico e o tratamento de pacientes com ICFEp permanecem desafiadores. O diagnóstico sindrômico de ICFEp inclui diversas etiologias e doenças com tratamentos específicos, mas que apresentam pontos em comum em relação à apresentação clínica e à avaliação laboratorial no que diz respeito aos biomarcadores como BNP e NT-ProBNP, à avaliação ecocardiográfica do remodelamento cardíaco e às pressões de enchimento diastólico ventricular esquerdo. Extensos ensaios clínicos randomizados envolvendo a terapia nesta síndrome falharam na demonstração de benefícios para o paciente, fazendo-se necessária uma reflexão acerca do diagnóstico, dos mecanismos de morbidade, da taxa de mortalidade e da reversibilidade. Na revisão, serão abordados os conceitos atuais, as controvérsias e, especialmente, os desafios no diagnóstico da ICFEp através de uma análise crítica do escore da European Heart Failure Association.

Keywords: Insuficiência Cardíaca/fisiopatologia, Diagnóstico por Imagem, Ecocardiografia/métodos, Peptídeos Natriuréticos

Introdução

Estima-se que, na maioria da população acima de 60 anos de idade, cerca de 5% dos pacientes apresentam diagnóstico de insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção preservada (ICFEp), sendo que a prevalência varia entre 3,8 a 7,4% entre os estudos realizados, considerando-se as diferentes metodologias no diagnóstico.1 Com o aumento da expectativa de vida da população e a maior frequência de fatores de risco como obesidade, hipertensão arterial e diabetes, espera-se um aumento na prevalência de ICFEp.2 - 4

Entretanto, até o momento, o diagnóstico e o tratamento de pacientes com ICFEp permanecem desafiadores. O diagnóstico sindrômico de ICFEp inclui diversas etiologias e doenças com tratamentos específicos, mas que apresentam pontos em comum em relação à apresentação clínica, à avaliação laboratorial no que diz respeito aos biomarcadores como BNP e NT-ProBNP e à avaliação ecocardiográfica do remodelamento cardíaco e das pressões de enchimento diastólico ventricular esquerdo.1 Ao contrário da IC-FEr, nenhum tratamento mostrou de forma convincente a redução da morbidade ou mortalidade na ICFEp, fazendo-se necessária uma reflexão acerca do diagnóstico, dos mecanismos de morbidade, da mortalidade e da reversibilidade nesta síndrome.5

Na revisão, serão abordados os conceitos atuais, controvérsias e, especialmente, os desafios no diagnóstico da ICFEp, analisando criticamente o escore da European Heart Failure Association .1

Escore da European Heart Failure Association para o diagnóstico da ICFEp

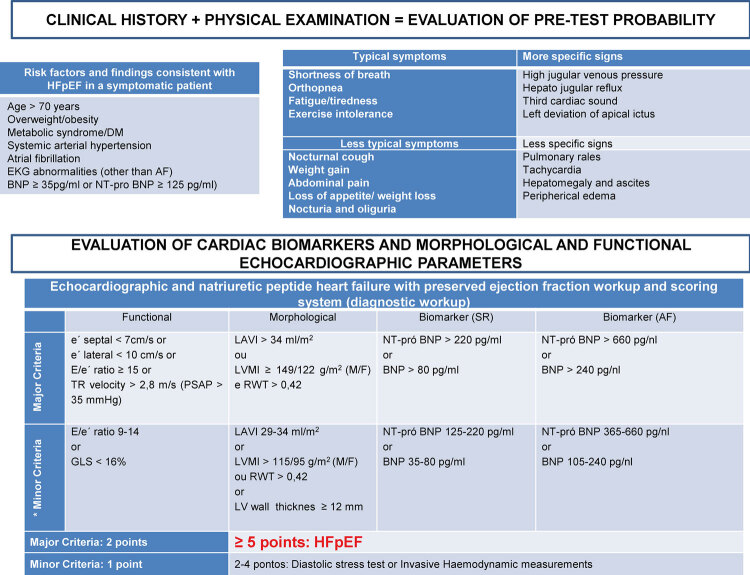

Em 2019, foi publicado pela Heart Failure Association (HFA), da European Society of Cardiology (ESC), um novo posicionamento para o diagnóstico de ICFEp, que inclui o papel das comorbidades clínicas e um sistema fundamentado em escore com valores atualizados dos critérios ecocardiográficos e a dosagem de biomarcadores, além do papel dos testes feitos sob esforço ( Tabela 1 ).6 - 8

Tabela 1. Algoritmo Heart Failure Association (HFA) para o diagnóstico de ICFEp, da European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

| P | Avaliação inicial |

|

| Passo 1 (P): avaliação pré-teste |

|

|

|

||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| E | Avaliação diagnóstica |

|

| Passo 2 (E): escore ecocardiográfico e peptídeos natriuréticos | ||

| F1 | Avaliação avançada |

|

| Passo 3 (F1): teste funcional em caso de incertezas |

|

|

| F2 | Avaliação etiológica final |

|

| Passo 4 (F2): Etiologia final |

|

|

|

||

| ||

|

IC: insuficiência cardíaca; CT: tomografia computadorizada; PET CT: Tomografia por Emissão de Pósitrons. Adaptado de Pieske B et al.1

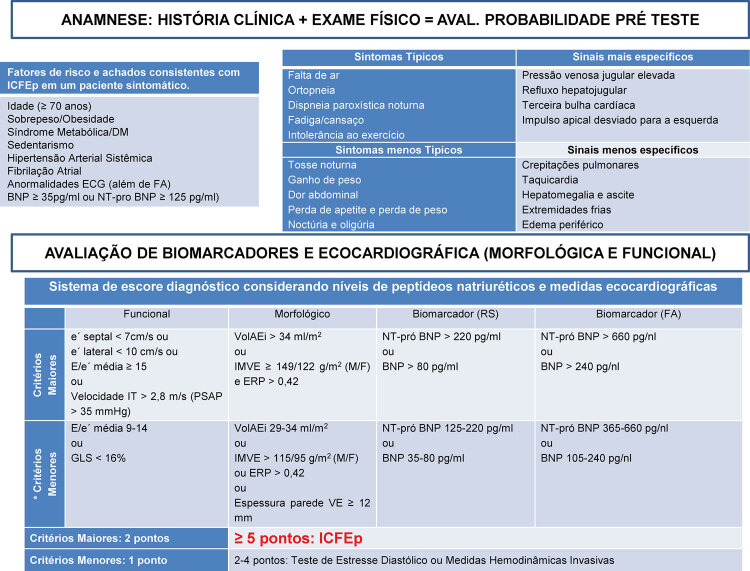

A avaliação inicial deve levar em consideração a anamnese, abordando os fatores de risco, as comorbidades, a presença de sintomas e os sinais relacionados ao exame físico de insuficiência cardíaca que sugiram o diagnóstico de ICFEp, conforme o diagrama a seguir ( Tabela 1 ). Nessa fase inicial, devem ser realizados exames de sangue, incluindo peptídeos natriuréticos (PN), eletrocardiograma, teste ergométrico, teste de caminhada de seis minutos e/ou teste cardiopulmonar, além de avaliação ecocardiográfica.1

O eletrocardiograma (ECG) pode evidenciar sinais de hipertrofia ventricular esquerda (índice de Sokolow-Lyon; índice ≥3,5 mV) e/ou sobrecarga atrial esquerda, mas sua principal indicação é detectar a presença de fibrilação atrial (FA), altamente preditiva de ICFEp subjacente.9 , 10

O racional para o emprego do escore baseia-se no fato de que nenhum critério não invasivo é suficiente de maneira isolada para o diagnóstico de ICFEp. Por isso, recomenda-se a avaliação integrada das informações clínicas, das medidas dos níveis séricos de PN e da estrutura e função cardíaca pela ecocardiografia.10 É importante lembrar que os valores de corte podem variar de acordo com a idade, gênero, peso corporal, função renal e presença de FA. Assim, são recomendados critérios menores e maiores de acordo com o grau de alteração na presença dos fatores modificadores acima descritos.1

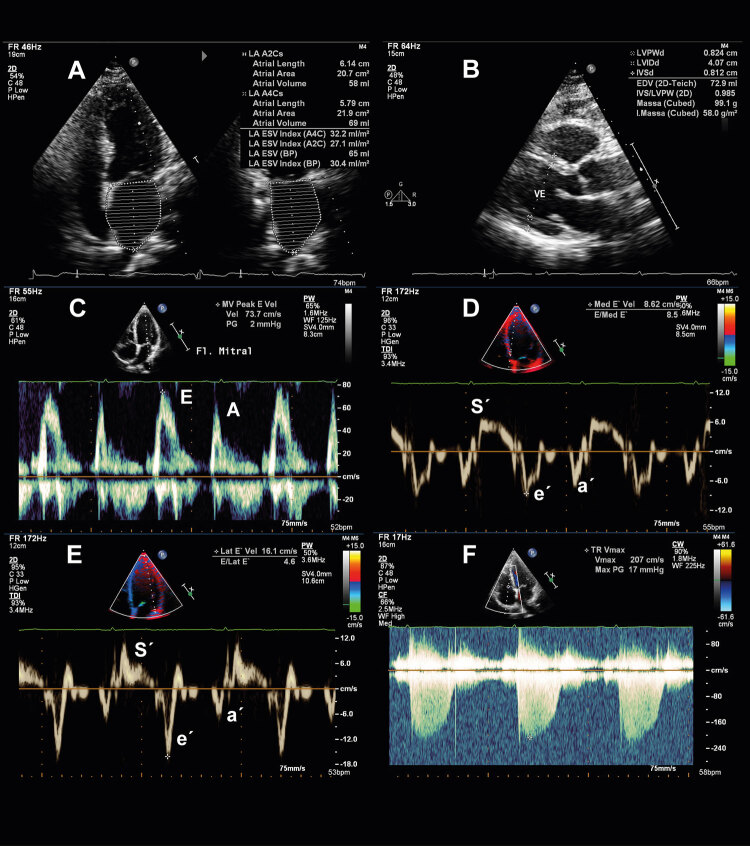

Valores de PN em pacientes em ritmo de FA podem ser até três vezes maiores do que em pacientes em ritmo sinusal. Por isso, os valores de corte são diferenciados para as duas populações de pacientes.11 , 12 Até o momento, valores de corte definitivos para o diagnóstico de ICFEp em pacientes em ritmo sinusal ou FA não foram bem estabelecidos.1 Os valores sugeridos para o diagnóstico de ICFEp são descritos na Figura 2 .

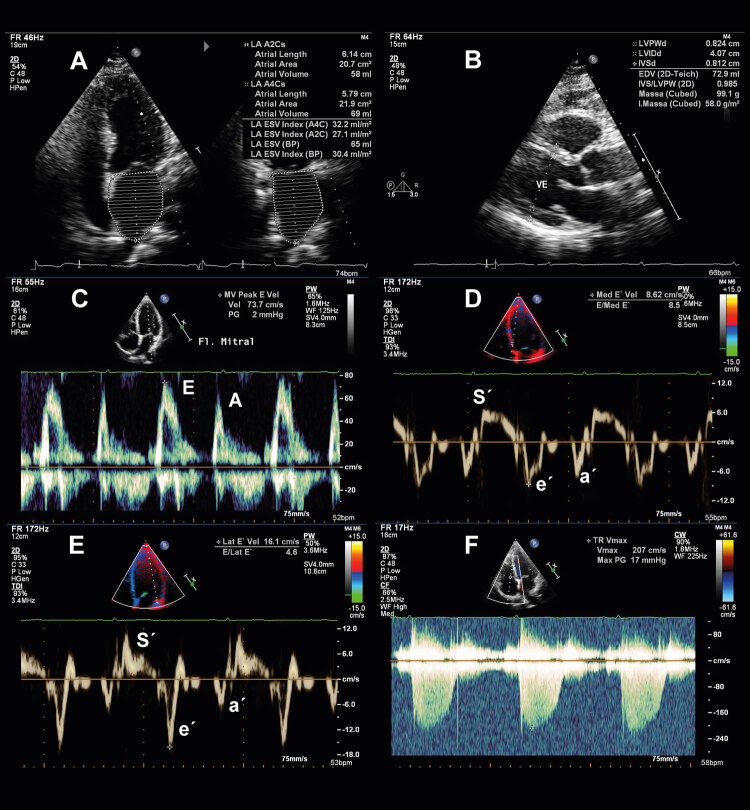

Figura 2. Critérios ecocardiográficos morfológicos (A e B) e funcionais (C a F) para aplicação do algoritmo diagnóstico para pacientes com suspeita de ICFEp. Os critérios morfológicos incluem a medida do volume indexado do átrio esquerdo (A), e o cálculo do índice de massa miocárdica e a espessura relativa de parede (B). Os critérios funcionais incluem a relação E/e’, calculada a partir da medida de onda E ao Doppler mitral (C) (v = 73,7 cm/s) e ondas e’ ao Doppler tecidual septal (D) (v = 8,6 cm/s) e lateral (E) (v = 16,1 cm/s), além da velocidade de pico do jato de regurgitação tricúspide (v = 2,07 cm/s) para estimar a medida da pressão sistólica de artéria pulmonar (F). v: velocidade.

Avaliação ecocardiográfica

A ecocardiografia é o método de imagem cardíaca de escolha na avaliação do paciente com sinais e sintomas de IC. O ecocardiograma permite a avaliação anatômica funcional pelas medidas dos diâmetros e volumes das cavidades cardíacas, estimativa da massa ventricular esquerda e análise da função sistólica pela fração de ejeção, além da função longitudinal global e segmentar miocárdica. É o método não invasivo de escolha para a análise da função diastólica e das pressões de enchimento ventricular esquerdo e da artéria pulmonar.1

Critérios morfológicos

Medidas do volume atrial esquerdo indexado (VolAEi)

O VolAEi está relacionado às pressões de enchimento do VE e a outros índices de função diastólica, sendo a medida mais acurada do remodelamento crônico do AE quando é comparada ao diâmetro e área do AE.13 , 14

Em pacientes sem FA ou doença valvar cardíaca, o VolAEi >34 ml/m2 é preditor independente de morte, IC, FA e acidente vascular encefálico isquêmico.15 , 16 Em pacientes com ICFEp e FA permanente, o VolAEi foi 35% maior do que nos pacientes com ICFEp em ritmo sinusal.11 Pacientes com FA permanente podem apresentar maiores VolAEi, mesmo na ausência de disfunção diastólica. Assim, recomenda-se valores de corte distintos de VolAEi para o diagnóstico de ICFEp de pacientes em ritmo sinusal e FA ( Figuras 1 e 2 ).15 , 16

Figura 1. Fluxograma para avaliação clínica, integrando fatores de risco, exame físico, avaliação de biomarcadores e análise ecocardiográfica. DM: diabetes mellitus; ECG: eletrocardiograma; FA: fibrilação atrial; IT: insuficiência tricúspide; PSAP: pressão sistólica em artéria pulmonar; VolAEi: volume do átrio esquerdo indexado; IMVE: índice de massa do ventrículo esquerdo; ERP: espessura relativa da parede ventricular; BNP: peptídeo natriurético atrial; GLS: strain global longitudinal; ICFEp: insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção preservada.* Critério menor não deve ser contabilizado dentro do mesmo domínio.

Medidas da espessura miocárdica e estimativa da massa ventricular esquerda

No escore da HFA, a espessura ventricular esquerda ao final da diástole das paredes septal e posterior foi considerada um critério morfológico para o diagnóstico de ICFEp.1 Preferencialmente, tais medidas devem ser obtidas

no modo 2D, ou no modo M guiado pelo 2D, de acordo com a fórmula recomendada pela Sociedade Americana de Ecocardiografia.17 , 18

O índice de IMVE é definido como a massa ventricular esquerda indexada pela superfície corpórea. A hipertrofia é o aumento do IMVE, de acordo com os seguintes valores de referência: ≥95 g/m2 em mulheres e ≥115 g/m2 em homens.17 , 18 É importante considerar o cálculo da espessura relativa de parede (ERP).17 , 18 A análise da IMVE e da ERP permite a categorização da hipertrofia em concêntrica (aumento do IMVE e ERP >0,42), excêntrica (aumento do IMVE e ERP <0,42) e remodelamento concêntrico (IMVE normal e ERP >0,42).17 , 18

Em pacientes com ICFEp, é possível observar os padrões de remodelamento ou hipertrofia concêntrica. No entanto, a ausência de hipertrofia ventricular esquerda não exclui o diagnóstico de ICFEp.1 Dessa forma, são considerados os critérios descritos na Figuras 1 e 2 .

Critérios funcionais

Medidas do Strain Sistólico Longitudinal Global (GLS) do VE

A medida da deformação miocárdica ( strain ) longitudinal global ventricular esquerda (GLS) pela técnica de speckle tracking independe do ângulo de insonação do ultrassom confere vantagem em relação à medida do strain obtida pelo Doppler e é considerada a técnica de eleição.19

É importante relatar que equipamentos de diferentes marcas podem apresentar variação entre os valores de GLS aferidos em um mesmo paciente. Um valor absoluto de GLS <16% pode ser considerado anormal e, ao mesmo tempo, um critério menor para o diagnóstico de ICFEp (ver Figura 2 ).1 Valores reduzidos de GLS são preditores de hospitalização por IC, morte cardiovascular ou parada cardiorrespiratória, apresentando boa correlação com a rigidez do VE e com biomarcadores.19 - 20

Medidas ao Doppler convencional

Ao Doppler convencional, são utilizadas as medidas da onda E ao Doppler pulsátil da valva mitral para o cálculo da relação E/e’ e a velocidade de pico do jato de insuficiência tricúspide (IT) ao Doppler contínuo. Tais medidas são importantes nas estimativas de elevação das pressões de enchimento e, consequentemente, para o diagnóstico de ICFEp.1 , 19 , 20

Medidas elevadas de pressão sistólica em artéria pulmonar (PSAP) e redução da função ventricular direita são importantes preditores de mortalidade em pacientes com ICFEp. Valores da velocidade de pico do jato de insuficiência tricúspide > 2,8 m/s são marcadores indiretos de disfunção diastólica e estão associados ao diagnóstico de ICFEp.21 - 24

Medidas ao Doppler tecidual

As medidas das velocidades de pico diastólicas precoces (ondas e’) nas paredes septal e lateral ao Doppler tecidual pulsátil são um parâmetro fundamental em pacientes com ICFEp.1 , 25 Todas as medidas devem representar a média de três ou mais ciclos cardíacos consecutivos, e, preferencialmente, devem ser realizadas as medidas das velocidades das ondas e’ septal e lateral, em particular para o cálculo da relação E/e’.25

O maior determinante da velocidade diastólica precoce da movimentação do anel mitral é o relaxamento do VE. A onda e’ reflete o relaxamento do VE e está influenciada pela pré-carga.26 , 27 A velocidade da onda e” diminui com a idade e, por isso, são recomendados valores de referência de acordo com a idade para o cálculo do escore para o diagnóstico de ICFEp ( Figuras 1 e 2 ).28

A relação E/e’ média das paredes septal e lateral reflete a pressão capilar pulmonar média e correlaciona-se com a rigidez ventricular esquerda e a presença de fibrose, além de ser menos dependente da idade e envelhecimento do que a onda e’.1 , 25 , 29 , 30 A medida também apresenta valor diagnóstico durante o esforço físico, sendo pouco influenciada por alterações volumétricas, mas influenciada pela gravidade da hipertrofia ventricular esquerda.1 , 31 - 33

Avaliação diagnóstica pelo escore ecocardiográfico e peptídeos natriuréticos

O escore apresenta domínios funcionais, morfológicos e relacionados aos biomarcadores, e cada critério maior atribui 2 pontos e cada critério menor 1 ponto ( Figura 2 ). É importante lembrar que nem todos os parâmetros de cada domínio podem ser analisáveis. Um escore total ≥5 pontos é considerado diagnóstico para ICFEP enquanto escores ≤1 ponto indicam o diagnóstico muito improvável e torna mandatória a investigação de diagnósticos diferenciais.1 Pacientes com pontuação intermediária necessitam de avaliação adicional complementar (passo 3), conforme a seguir. Na prática e de maneira estruturada, os passos 1 e 2 podem ser resumidos no fluxograma da Figura 2 .

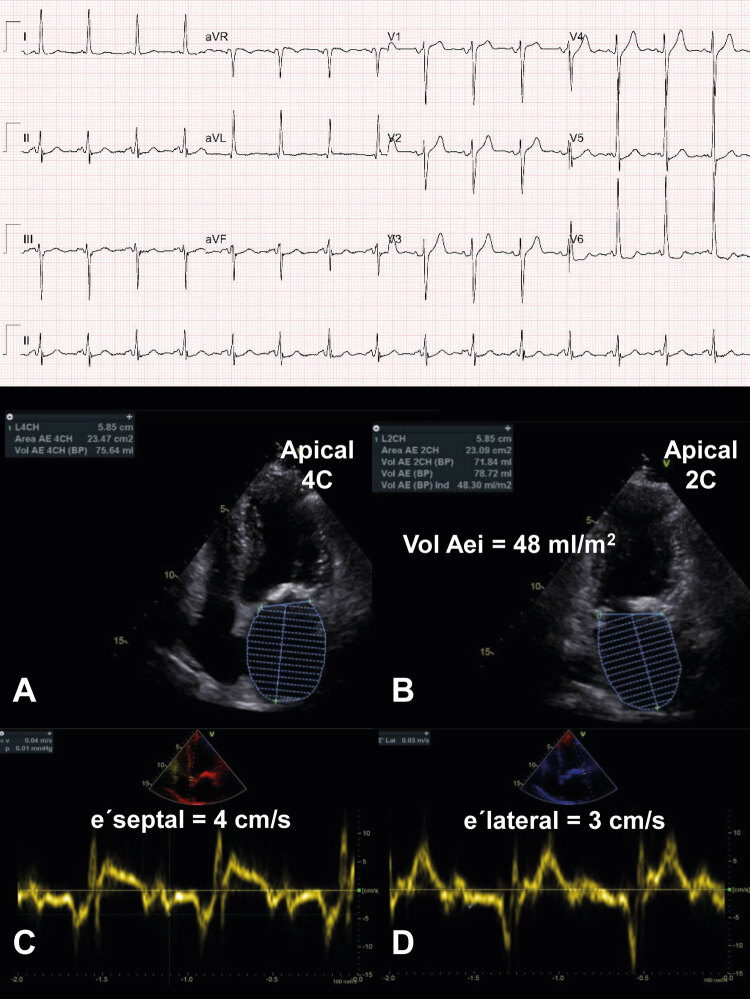

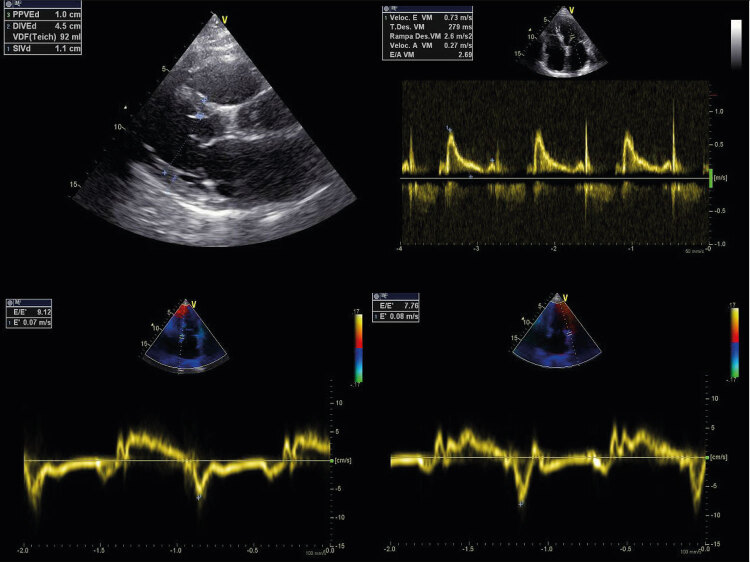

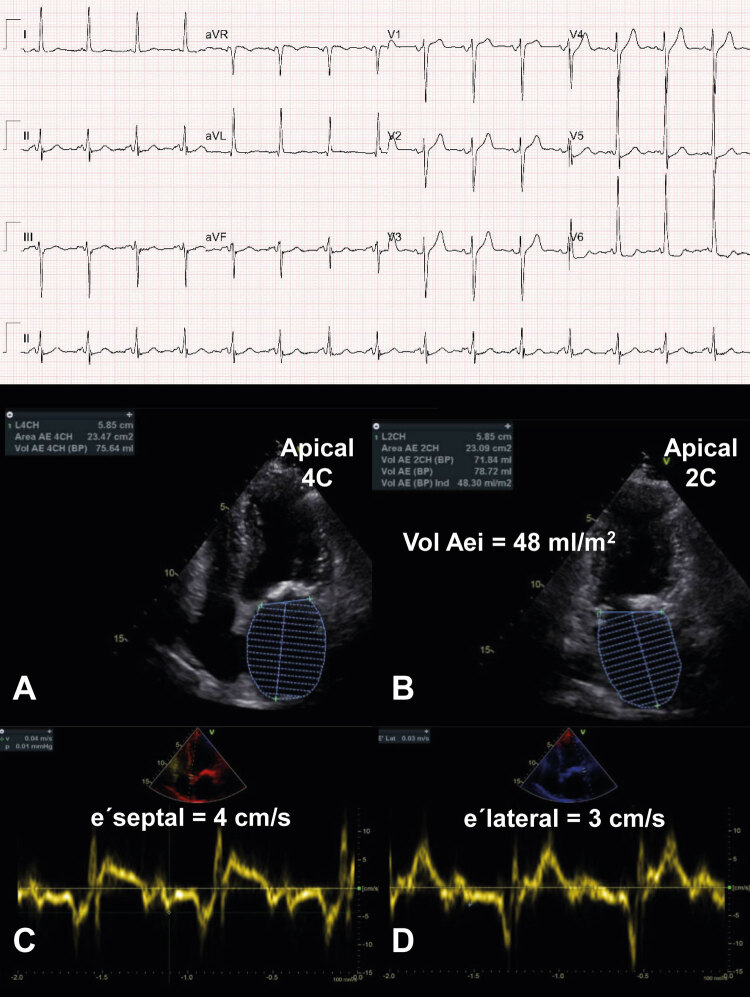

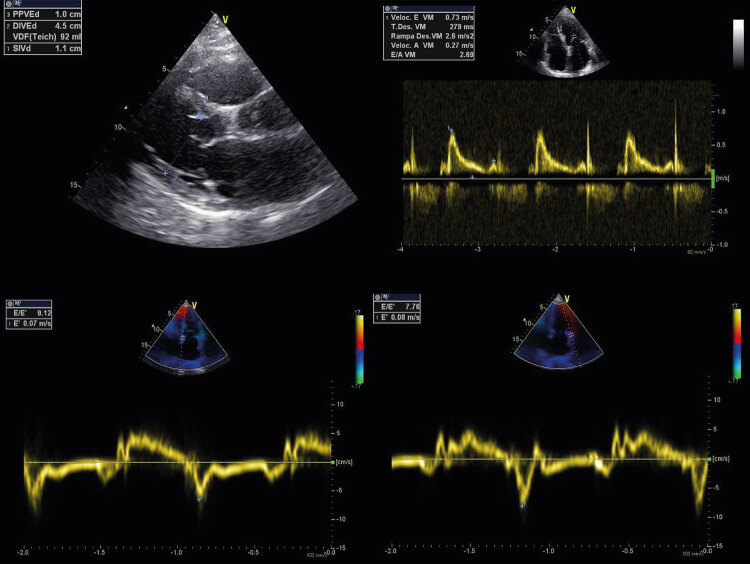

Nas Figuras 3 e 4 , seguem exemplos ilustrativos da aplicação do escore em casos reais.

Figura 3. Exemplo ilustrativo de aplicação do escore diagnóstico em indivíduo com suspeita de ICFEp. Paciente do sexo feminino, 64 anos, com antecedentes de síndrome metabólica (obesidade grau III – IMC: 35,6, HAS e DM) e queixa de dispneia aos mínimos esforços (CF III NYHA). Ao ECG (acima), observa-se sinais de hipertrofia ventricular esquerda pelos critérios de Sokolow-Lyon. Apresenta ao ETT espessura do septo interventricular e parede posterior de 12 mm e IMVE: 105 g/m2 (1 ponto). Volume indexado do átrio esquerdo estimado ao corte apical 4C (acima à esquerda) e apical 2C (acima à direita) em 48 ml/m2 (2 pontos). Doppler tecidual evidencia onda e’ septal = 4 cm/s (abaixo à esquerda) e onda e’ lateral = 3 cm/s (abaixo à direita) (2 pontos). Assim, aplicando-se o escore para o diagnóstico de ICFEp, a paciente apresenta 5 pontos e, portanto, diagnóstico de ICFEp. VolAEi: volume do átrio esquerdo indexado.

Figura 4. Paciente de 78 anos com obesidade, hipertensão arterial sistêmica, diabetes melito tipo 2 e fibrilação atrial paroxística em CF II NYHA. Ao ETT, apresenta AE = 50 mm, volume indexado de AE = 38 ml/m2 (2 pontos), índice de massa VE: 89 g/m2 e espessura relativa de parede = 0,47 e PSAP não analisável, relação E/e’ = 8,8 e BNP = 367 pg/ml (2 pontos). Aplicando-se o escore para o diagnóstico de ICFEp, paciente apresenta 4 pontos e, portanto, diagnóstico inconclusivo de ICFEp.

No caso real da Figura 3 , apesar de a paciente preencher critério menor morfológico de espessura relativa de parede >0,42, como já recebeu pontuação dentro do domínio morfológico por critério maior (2 pontos) pela dilatação do volume indexado, é importante salientar que o critério menor não é contabilizado dentro do mesmo domínio. A situação também é ilustrativa por evidenciar a limitação das medidas sugeridas em casos reais. Na paciente, não foi possível aferir a pressão sistólica de artéria pulmonar por conta da ausência de refluxo tricúspide, situação ocasional na prática diária.

Além disso, a paciente apresentava limitação para realizar teste sob esforço por conta de obesidade e alterações degenerativas articulares e não prosseguiu com a investigação etiológica sugerida pelo protocolo da HFA.

É importante considerar que, em pacientes com diagnóstico de estenose mitral, a onda E pode não refletir a função diastólica. Em pacientes com insuficiência tricúspide importante, a velocidade do jato de insuficiência tricúspide pode estar reduzida devido à equalização entre as pressões de VD e AD, subestimando a estimativa da PSAP.25

Passo 3 (F1): avaliação avançada – teste funcional em caso de incertezas

Em pacientes com pontuação intermediária no escore diagnóstico, é indicada uma avaliação complementar com ecocardiografia e sob esforço físico, pois muitos pacientes apresentam apenas sintomas relacionados aos esforços. Dessa forma, sintomas compatíveis com ICFEp podem ser confirmados a partir de anormalidades hemodinâmicas como reduções do débito cardíaco e do volume sistólico e a elevação das pressões de enchimento do VE em repouso ou durante o esforço físico.1 , 34

O ecocardiograma sob esforço pode revelar disfunção sistólica e diastólica durante o exercício. Os parâmetros mais empregados para essa análise na suspeita de ICFEp são a relação E/e’ e a velocidade de pico do jato de insuficiência tricúspide. Recomenda-se a realização do exame em repouso, durante todo o esforço, ou logo após o pico da atividade. Contudo, até o momento não existem protocolos universalmente aceitos, os exames são realizados de acordo com a disponibilidade e a experiência de cada serviço.1 , 34

A relação E/e’ e a velocidade de pico do jato da insuficiência tricúspide devem ser adquiridas no momento basal e em cada estágio, incluindo o pico do esforço, durante o estágio submáximo e/ou nos primeiros dois minutos da fase de recuperação.34

O ecocardiograma sob esforço deve ser considerado anormal quando a relação E/e’ obtida no pico do esforço for ≥15, com ou sem aumento da velocidade de pico da IT para um valor >3,4 m/s. Um aumento isolado na velocidade da IT não deve ser considerado para o diagnóstico de ICFEp, uma vez que essa alteração pode ser meramente causada por uma resposta hiperdinâmica normal ao exercício (aumento do fluxo pulmonar) e na ausência disfunção diastólica do VE. Uma relação E/e’ durante o esforço ≥15 soma 2 pontos ao escore da HFA. Uma relação E/e’ ≥ 15 e a velocidade de pico da IT >3,4 m/s acrescentam 3 pontos ao escore a partir do passo 2 (E). Então, a associação do escore combinado a partir dos passos 2 (E) e 3 (F1) ≥ 5 confirma o diagnóstico de ICFEp.1 , 34

Entretanto, algumas limitações são passíveis de ocorrer: a relação E/e’ pode não ser analisável em cerca de 10% dos pacientes durante o esforço submáximo (20W), a velocidade da IT ser mensurável em apenas 50% dos pacientes e cerca de 20% dos pacientes podem ser considerados “falsos positivos”.31 Além disso, em nosso país, a disponibilidade de serviços que realizam o ecocardiograma sob esforço físico é bastante escassa, mesmo em cidades com grandes serviços de referência em Cardiologia. No exemplo da Figura 4 , alguns pacientes não se mostram aptos a realizar o procedimento por limitação sintomática ou pela limitação funcional como a coexistência de doenças ortopédicas, articulares, vasculares ou neurológicas.34

Finalmente, os dados obtidos a partir da ecocardiografia sob esforço não são suficientes para substituir medidas hemodinâmicas invasivas. Quando o escore persistir <5 pontos ou o ecocardiograma sob esforço não puder ser realizado, recomenda-se a avaliação invasiva quando surgirem dúvidas.1 A última diretriz da EACVI25 sugere a avaliação hemodinâmica invasiva sob esforço; porém, em nosso país, essa é uma prática utilizada muito raramente e apenas em pacientes específicos. Na prática clínica, pode ser realizada a avaliação invasiva para confirmar a elevação das pressões de enchimento ventriculares esquerdas em repouso (pressão diastólica final do VE ≥16 mmHg) e o diagnóstico de ICFEp.1 A avaliação invasiva também deve ser considerada para a exclusão de doença coronária ou em populações específicas.35

Passo 4 (F2): etiologia final

A maioria dos casos de ICFEp está relacionado a fatores de risco e comorbidades comuns. Porém, a possibilidade de uma etiologia subjacente especifica deve sempre ser considerada: cardiomiopatia hipertrófica, miocardite, doenças autoimunes, cardiomiopatias infiltravas, doenças de depósito e endomiocardiofibrose são exemplos.36 - 38 Uma vez diagnosticada a ICFEP, a investigação de cada etiologia especifica deve ser pautada pela suspeição clínica e realizada de maneira direcionada na dependência do diagnóstico presuntivo. É fundamental detectar as etiologias específicas, uma vez que esses achados podem se traduzir em terapêuticas específicas. Também é importante considerar que as etiologias não relacionadas ao miocárdio podem apresentar quadro clínico semelhante à ICFEp, como pericardite constritiva, doenças valvares primárias e insuficiência cardíaca de alto débito.1

Limitações, perspectivas e considerações finais

A ICFEp é uma síndrome clínica com múltiplos fatores contribuintes, etiologias e mecanismos fisiopatológicos distintos, de maneira que é impossível a criação de um algoritmo único capaz de realizar o diagnóstico de um grupo tão diversificado de doenças.39 Além disso, os resultados dos testes podem ser limitados a este grupo de pacientes, em estágios diferentes da doença e com heterogeneidade de etiologias.1

O escore da HFA não atribui pontuação aos fatores de risco clínicos, e sinais e sintomas ao exame físico conforme proposto por autores americanos.10 É importante considerar estes fatores, uma vez que, isoladamente, os demais parâmetros dissociados do quadro clínico e exame físico perdem a acurácia diagnóstica. Além disso, outras situações clínicas que não a IC podem levar a elevações dos níveis séricos de biomarcadores como doenças crônicas renais, pulmonares e processos infecciosos, limitando sua aplicação no contexto do paciente com suspeita de IC, uma vez que neste grupo de pacientes a ocorrência destas doenças não é infrequente.40

Atualmente, fenótipos distintos tem sido reconhecidos na apresentação clínica dos pacientes com ICFEp, como em relação à caracterização da função atrial esquerda, pressões pulmonares e função ventricular direita.41 Nesse contexto, outros parâmetros ecocardiográficos em um futuro próximo poderão ser incorporados ao escore, aumentando a sensibilidade diagnóstica e o detalhamento da fisiopatologia da ICFEp.

Variáveis como os índices de deformação ou ( strain ) atrial esquerda apresentam importância crescente na avaliação da função diastólica e nas pressões de enchimento do ventrículo esquerdo. O desenvolvimento de softwares dedicados à avaliação do strain atrial tem permitido a avaliação mais detalhada da função atrial esquerda e também a análise da rigidez atrial esquerda. Este último é um parâmetro que apresenta correlação logarítmica com as pressões de enchimento do VE e melhor acurácia na predição de valores >15 mmHg da pressão diastólica final do VE em relação à relação E/e’.42 - 44 Adicionalmente, outros parâmetros como a deformação do ventrículo direito (global ou da parede livre) desempenham papel promissor no diagnóstico da ICFEp.45 - 46

Provavelmente, em um futuro próximo, será possível a análise morfológica não invasiva e relacionada a volumes das cavidades cardíacas, parâmetros hemodinâmicos como volume sistólico, débito cardíaco, pressões de enchimento em associação a novos marcadores de função sistólica e diastólica agregando valor diagnóstico e prognóstico ao significado da FEVE na caracterização da IC.47 - 49

O emprego dos métodos modernos para geração de imagem, de maneira integrada, pode fornecer os dados acima mencionados e análises dinâmicas sobre a função arterial, endotelial e perfusão miocárdica, que podem ser acopladas aos dados demográficos, incluindo fatores de risco clássicos e novos biomarcadores com dados sobre proteômica, metabolômica e genética. As informações poderão ser processadas por inteligência artificial, podendo ser úteis na definição de fisiopatologia, diagnóstico, direcionamento terapêutico e predição de desfechos.47 - 49

Assim, apesar da elaboração de escores atualizados para o diagnóstico da ICFEp à luz dos novos conhecimentos, principalmente em relação às técnicas ecocardiográficas e aos valores de biomarcadores, ainda são necessários refinamentos e incorporação de mais índices clínicos e ecocardiográficos que permitam não apenas o diagnóstico sindrômico, mas que também orientem a etiologia final dos pacientes com ICFEp.

Vinculação Acadêmica

Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este artigo não contém estudos com humanos ou animais realizados por nenhum dos autores.

Fontes de Financiamento: O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.Pieske B, Tschöpe C, de Boer RA, Fraser AG, Anker SD, Donal E. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz641Eur Heart J. 2019;40(40):3297–3317. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Riet EES, Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Limburg A, Landman MA, Rutten FH, et al. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. 10.1002/ejhf.483Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(3):242–252. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seferovic PM, Petrie MC, Filippatos GS, Anker SD, Rosano G, Bauersachs J, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. 10.1002/ejhf.1170Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(5):853–872. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. 10.1002/ejhf.592Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes SL, Carvalho RR, Santos LG, Sá FM, Ruivo C, Mendes SL, et al. Pathophysiology and treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: state of the art and prospects for the future. 10.36660/abc.20190111Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020;114(1):120–129. doi: 10.36660/abc.20190111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasan RS, Levy D. Defining diastolic heart failure: a call for standardized diagnostic criteria. 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2118Circulation. 2000;101(7):2118–2121. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yturralde RF, Gaasch WH. Diagnostic criteria for diastolic heart failure. 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.02.007Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;47:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulus WJ, Tschope C, Sanderson, Rusconi C, Flachskampf FA, Rademakers FE, et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2539–2550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Gersh BJ, Borlang BA. High prevalence of occult heart failure with preserved ejection fraction among patients with atrial fibrillation and dyspnea. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030093Circulation. 2018;137(5):534–535. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy YNV, Carter RE, Obokata M, Redfield MM, Borlang BA. A simple, evidence-based approach to help guide diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034646Circulation. 2018;138(9):861–870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam CS, Rienstra M, Tay WT, Liu LCY, Hammel YM, van der Meer P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: association with exercise capacity, left ventricular filling pressures, natriuretic peptides, and left atrial volume. 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.10.005JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKelvie RS, Komajda M, McMurray J, Zile M, Ptaszynska A, Donovan M, et al. Baseline plasma NT-proBNP and clinical characteristics: results from the irbesartan in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction trial. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.09.007J Card Fail. 2010;16(2):128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefano GT, Zhao H, Schluchter M, Hoit BD. Assessment of echocardiographic left atrial size: accuracy of M-mode and two-dimensional methods and prediction of diastolic dysfunction. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01643.xEchocardiography. 2012;29(4):379–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moya-Mur JL, Garcia-Martin A, Garcia-LLedo A, Ruiz-Leria S, Jimenes-Nacher Mejias Sanz A, Taboada D, Muriel A, et al. Indexed left atrial volume is a more sensitive indicator of filling pressures and left heart function than is anteroposterior left atrial diameter. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01216.xEchocardiography. 2010;27(9):1049–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Redfield MM, Bokeri R, Lin G, Borlang BA. Left atrial remodeling and function in advanced heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001667Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(2):295–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almeida P, Rodrigues J, Lourenco P, Mj Maciel, Bettencourt P. Left atrial volume index is critical for the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000651J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2018;19(6):304–309. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7(2):79–108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. 10.1093/ehjci/jev014Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(3):233–270. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugimoto T, Dulgheru R, Bernard A, Ilardi F, Contu L, Addetia K, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal left ventricular 2D strain: results from the EACVI NORRE study. 10.1093/ehjci/jex140Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18(8):833–840. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kocabay G, Muraru D, Peluso D, Cucchini U, Mihaila S, Padayattil JS, et al. Normal left ventricular mechanics by two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography. Reference values in healthy adults. 10.1016/j.rec.2013.12.009Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2014;67(8):651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Naamani N, Preston IR, Paulus JK, Hill NS, Roberts KE. Pulmonary arterial capacitance is an important predictor of mortality in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.01.013JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(6):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenkranz S, Gibbs JSR, Wachter R, De Marco T, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Vachiery JL, et al. Left ventricular heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv512Eur Heart J. 2016;37(12):942–954. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorter TM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Bauersachs J, Borlaug BA, Celutikiene J, Coats AJS, et al. Right heart dysfunction and failure in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: mechanisms and management. Position statement on behalf of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. 10.1002/ejhf.1029Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(1):16–37. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschuanacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(7):685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagueh SF, Smiseth AO, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. 10.1093/ehjci/jew082Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(12):1321–1360. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opdahl A, Remme EW, Helle-Valle T, Lyseggen E, Vatdal T, Pettersen E, et al. Determinants of left ventricular early-diastolic lengthening velocity: independent contributions from left ventricular relaxation, restoring forces, and lengthening load. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791681Circulation. 2009;119(19):2578–2586. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham RJ, Gelman JS, Donelan L, Mottram PM, Peverill RE. Effect of preload reduction by haemodialysis on new indices of diastolic function. 10.1042/CS20030059Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;105(4):499–506. doi: 10.1042/CS20030059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Bibra H, Paulus WJ, St John Sutton M, Leclerque C, Schuster T, Schumm-Draeger PM, et al. Quantification of diastolic dysfunction via the age dependence of diastolic function – impact of insulin resistance with and without type 2 diabetes. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.005Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasner M, Westermann D, Lopez B, Gaub R, Escher F, Kuhl U, et al. Diastolic tissue Doppler indexes correlate with the degree of collagen expression and cross-linking in heart failure and normal ejection fraction. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.024J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(8):977–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah AM, Claggett B, Kitzman D, Biering-Sorensen T, Jensen JS, Cheng S, et al. Contemporary assessment of left ventricular diastolic function in older adults: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024825Circulation. 2017;135(5):426–439. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obokata M, Kane GC, Reddy YN, Olson TP, Melenorsky V, Borlaug BA. Role of diastolic stress testing in the evaluation for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a simultaneous invasive-echocardiographic study. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024822Circulation. 2017;135(9):825–838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donal E, Galli E, Fraser AG. Non-invasive estimation of left heart filling pressures: another nail in the coffin for E/e’? 10.1002/ejhf.944Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(12):1661–1663. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitter SS, Shah SJ, Thomas JD. A test in context: E/A and E/e’ to assess diastolic dysfunction and LV filling pressure. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.037J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):1451–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancellotti P, Pellikka PA, Budts W, Chaudhry FA, Donal E, Dulgheru R, et al. The clinical use of stress echocardiography in non-ischaemic heart disease: recommendations from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. 10.1093/ehjci/jew190Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(11):1191–1229. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trevisan L, Cautela J, Resseguier N, Lairre M, Arques S, Pinto J, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of coronary artery disease in heart failure with preserved and mid-range ejection fractions: A systematic angiography approach. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111(2):109–118. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charron P, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Caforio ALP, Kaski JP, Tavazzi L, et al. The Cardiomyopathy Registry of the EURObservational Research Programme of the European Society of Cardiology: baseline data and contemporary management of adult patients with cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(20):1784–1793. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasner M, Aleksandrov A, Escher F, Al-Saadi N, Makawski M, Spillman F, Genger M, et al. Multimodality imaging approach in the diagnosis of chronic myocarditis with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (MCpEF): the role of 2D speckle tracking echocardiography. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.038Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leong DP, De Pasquale CG, Selvanayagam JB. Heart failure with normal ejection fraction: the complementary roles of echocardiography and CMR imaging. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.12.011JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(4):409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triposkiadis F, Butler J, Abboud FM, Armstrong PW, Adamopoulos S, Atherton JS, et al. The continuous heart failure spectrum: moving beyond an ejection fraction classification. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz158Eur Heart J. 2019;40(26):2155–2163. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia Comitê Coordenador da Diretriz de Insuficiência Cardíaca. Diretriz Brasileira de Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica e Aguda. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;111(3):436–539. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, van Heerebuk K, Zile MR, Kass DA, et al. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a multiorgan roadmap. Circulation. 2016;134(1):73–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cameli M, Sparla S, Losito M, Righini FM, Menci D, Lisi M, et al. Correlation of left atrial strain and Doppler measurements with invasive measurement of left ventricular end diastolic pressure in patients stratified for different values of ejection fraction. 10.1111/echo.13094Echocardiography. 2016;33(3):398–405. doi: 10.1111/echo.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braunauer K, Pieske-Kraigher E, Belyavskiy E, Aravind-Kumar R, Kropf M, Kraft R, et al. Early detection of cardiac alterations by left atrial strain in patients with risk for cardiac abnormalities with preserved left ventricular systolic and diastolic function. 10.1007/s10554-017-1280-2Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34(5):701–711. doi: 10.1007/s10554-017-1280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris DA, Belyavskiy E, Aravind-Kumar R, Kropf M, Frydas A, Braunauer K, et al. Potential usefulness and clinical relevance of adding left atrial strain to left atrial volume index in the detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.029JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(10):1405–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris DA, M, Gailani M, Vaz Perez A, Blaschke F, Dietz R, Haverkamp W, et al. Right ventricular myocardial systolic and diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. 10.1016/j.echo.2011.04.005J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24(8):886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris DA, Krisper M, Nakatani S, Kohncke C, Otsuji Y, Belyavskiy E, et al. Normal range and usefulness of right ventricular systolic strain to detect subtle right ventricular systolic abnormalities in patients with heart failure: a multicentre study. 10.1093/ehjci/jew011Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18(2):212–223. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Omar AMS, Narula S, Abdel Rahman MA, Pedrizzetti G, Raslan H, Rifaie O, et al. Precision phenotyping in heart failure and pattern clustering of ultrasound data for the assessment of diastolic dysfunction. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.10.012JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(11):1291–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah SJ, Katz DH, Selvaraj S, Burke MA, Yancy CW, Gheorghiade M, et al. Phenomapping for novel classification of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010637Circulation. 2015;131(3):269–279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanchez Martinez S, Duchateau N, Erdei T, Kunazt G, Aakhur S, Degiovanni A, et al. Machine learning analysis of left ventricular function to characterize heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(4):e007138. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]