Abstract

Background

Interstitial pneumonia (IP) is a poor prognostic comorbidity in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and is also a risk factor for pneumonitis. The TORG1936/AMBITIOUS trial, the first known phase II study of atezolizumab in patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP, was terminated early because of the high incidence of severe pneumonitis.

Methods

This study included patients with idiopathic chronic fibrotic IP, with a predicted forced vital capacity (%FVC) of >70%, with or without honeycomb lung, who had previously been treated for NSCLC. The patients received atezolizumab every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was the 1-year survival rate.

Results

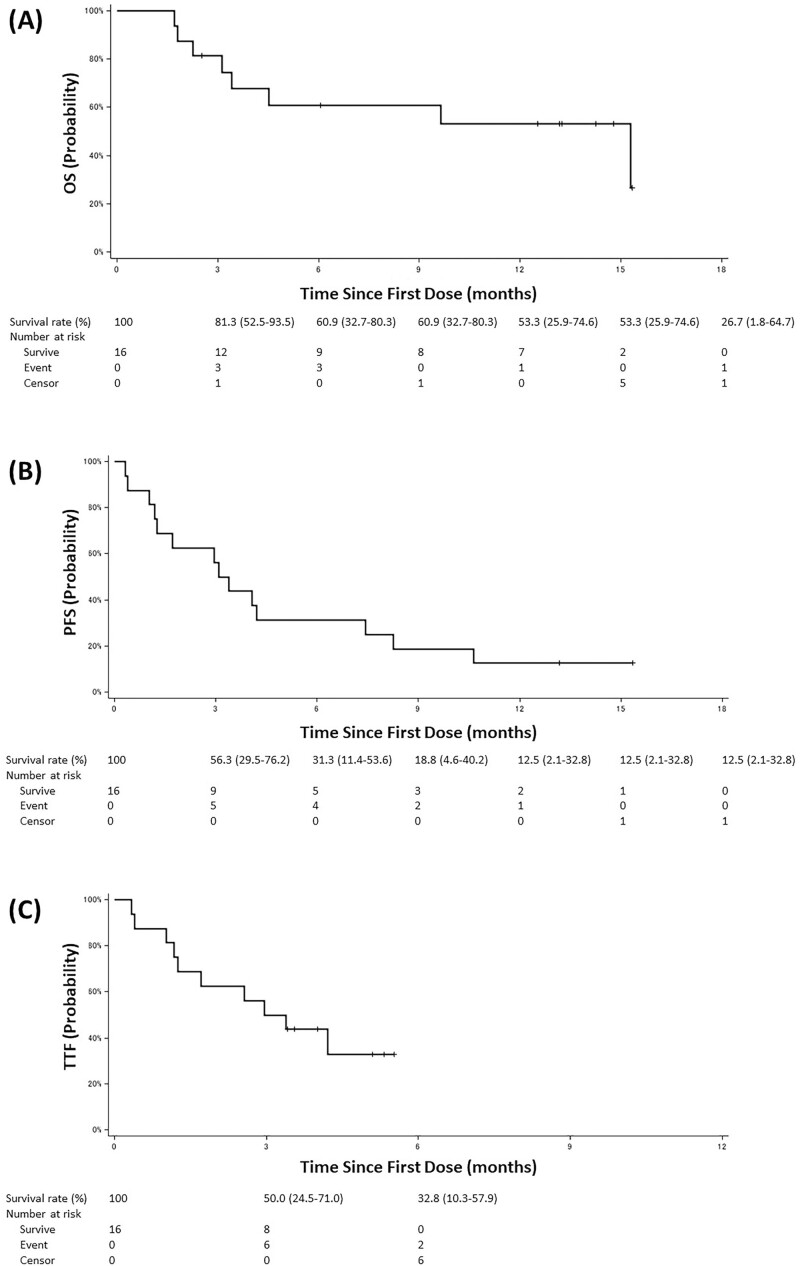

A total of 17 patients were registered; the median %FVC was 85.4%, and 41.2% had honeycomb lungs. The 1-year survival rate was 53.3% (95% CI, 25.9-74.6). The median overall and progression-free survival times were 15.3 months (95% CI, 3.1-not reached) and 3.2 months (95% CI, 1.2-7.4), respectively. The incidence of pneumonitis was 29.4% for all grades, and 23.5% for grade ≥3. Tumor mutational burden and any of the detected somatic mutations were not associated with efficacy or risk of pneumonitis.

Conclusion

Atezolizumab may be one of the treatment options for patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP, despite the high risk of developing pneumonitis. This clinical trial was retrospectively registered in the Japan Registry of Clinical Trials on August 26, 2019, (registry number: jRCTs031190084, https://jrct.niph.go.jp/en-latest-detail/jRCTs031190084).

Keywords: atezolizumab, non-small cell lung cancer, interstitial pneumonia, pneumonitis, immune checkpoint inhibitor

This phase II study evaluated the efficacy and safety of atezolizumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and comorbid interstitial pneumonia.

Lessons Learned.

This was the world’s first phase II study of atezolizumab in non–small cell lung cancer with interstitial pneumonia.

This study was terminated because 24% of patients developed pneumonitis grade ≥3.

Although the planned enrollment of 38 patients could not be completed and only 17 patients were enrolled, the primary endpoint of the 1-year survival rate was high at 53.3% (95% CI, 25.9-74.6).

Honeycomb lung on high-resolution computed tomography might be a candidate risk factor for pneumonitis.

Discussion

This was the first phase II study conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of atezolizumab in patients with NSCLC and comorbid IP. Although the planned enrollment of 38 patients could not be completed and only 17 patients were enrolled, the primary endpoint of the 1-year survival rate was 53.3% (95% CI, 25.9-74.6), and the lower limit of the 95% CI exceeded the threshold of 15% (Table 1, Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that although IP is a distinctly poor prognostic comorbidity in patients with NSCLC and pneumonitis of grade ≥3 developed frequently in this study, the efficacy and survival benefits of atezolizumab were comparable between patients with comorbid IP in this study and those without IP treated in previous prospective trials. Evidence on the efficacy of cytotoxic agents as second-line or later therapy in patients with comorbid IP is limited, and long-term survival can hardly be expected. Therefore, for patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP who have a poor prognosis and few treatment options, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) continues to hold promise as the only existing treatment option that can provide long-term survival.

Table 1.

Efficacy endpoints.

| (N = 16) | |

|---|---|

| One-year survival rate, % (95% CI) | 53.3 (25.9-74.6) |

| Median overall survival, months (95% CI) | 15.3 (3.1-not reached) |

| Median progression-free survival, months (95% CI) | 3.2 (1.2-7.4) |

| Median time to treatment failure, months (95% CI) | 3.2 (1.2-not reached) |

| Objective response | |

| Partial response, n (%) | 1 (6.3) |

| Stable disease, n (%) | 9 (56.3) |

| Progressive disease, n (%) | 6 (37.5) |

| Objective response rate, % (95% CI) | 6.3 (0.2-30.2) |

| Disease control rate, % (95% CI) | 62.5 (35.4-84.8) |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves: (A) overall survival, (B) progression-free survival, and (C) time to treatment failure. The vertical lines indicate censored events.

However, even if the balance between safety and efficacy of atezolizumab is considered, the 23.5% rate of developing grade ≥3 severe pneumonitis may be too risky. The logistic regression analysis suggested that honeycomb lung on chest computed tomography (CT) may be a risk factor for the development of pneumonitis. This result, however, was not significant, and the risk factor analysis was done post hoc on only a small number of cases, so no definitive conclusion can be drawn from these results alone. For appropriate patient selection, large observational and retrospective studies that include data, such as CT and pulmonary function tests, are needed to identify the risk factors for ICI-induced pneumonitis.

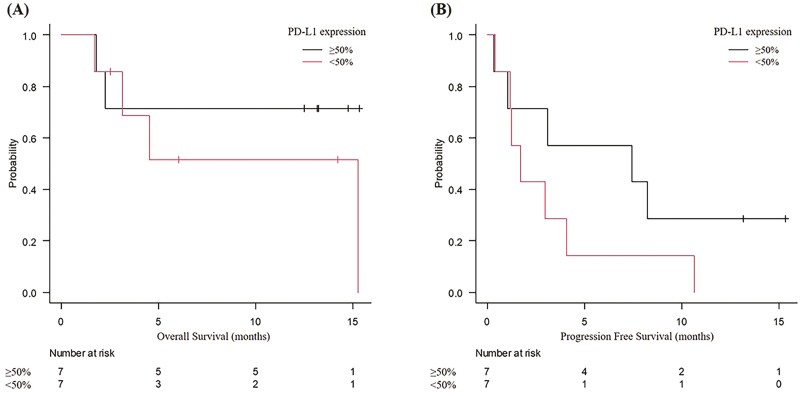

As biomarkers of efficacy, our post hoc analysis results showed a tendency for longer overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with PD-L1 ≥50% than in those with PD-L1 <50%. In practice, the decision to administer atezolizumab would need careful consideration of the risks (especially pneumonitis) and benefits, with reference to PD-L1 expression.

Trial Information

| Disease | Unresectable stage 3/4 or recurrent non–small cell lung cancer with comorbid chronic fibrotic interstitial pneumonia |

| Stage of disease/ treatment | Unresectable stage 3/4 or recurrent |

| Prior therapy | Received prior chemotherapy including platinum doublet |

| Type of study | Single arm, phase II study |

| Primary endpoint | One-year survival rate |

| Secondary endpoints | Incidence of pneumonitis (defined as the appearance of new interstitial shadows after atezolizumab administration that were judged by the investigator not to be infection, heart failure, or exacerbation of carcinomatous lymphangitis) within 1 year after treatment initiation, overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), time to treatment failure (TTF), mortality rate from pneumonitis during the observation period, and safety. |

| Investigator’s analysis | Active but too toxic as administered in this study |

Additional Details of Endpoints or Study Design

Exploratory Endpoints

Analysis of tumor mutational burden (TMB), somatic variations in 409 cancer-related genes, and microsatellite instability (MSI), exploratory study of efficacy by TMB, detected somatic mutations, and MSI

Inclusion Criteria

(1) Histologically or cytologically proven non–small cell lung cancer

(2) Unresectable stage 3/4 or recurrent

(3) Received prior chemotherapy including platinum doublet

-

(4) Chronic fibrotic interstitial pneumonia (the following 4 items must be met):

HRCT revealed reticular shadow with basal and peripheral predominance suggestive of UIP patterns, or peri-bronchovascular shadow suggestive of NSIP pattern

Without known etiology (eg, infection, pneumoconiosis, collagen vascular disease)

% Forced vital capacity >70%

% Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide >35%

(5) Age ≥20 years

(6) ECOG Performance Status 0-1

(7) With measurable or evaluable lesions according to RECIST Version 1.1

(8) Vital organ functions are preserved

(9) Received sufficient explanations about the name and severity of the illness

(10) Written informed consent

Exclusion Criteria

(1) History of acute exacerbation of IPF

(2) Treatment history with immune-checkpoint inhibitor

(3) Systemic treatment with steroids at a daily dose >10 mg of prednisolone equivalent or immunosuppressants

(4) Active autoimmune disease or history of autoimmune disease requiring treatment

(5) Symptomatic brain metastasis or spinal cord metastases

(6) Active viral hepatitis

(7) Active infection

(8) Synchronous or metachronous active double malignancies

(9) Pregnant or breastfeeding

(10) Disapprove of contraception during the protocol treatment period

(11) Treatment history with thoracic radiotherapy

(12) History of serious drug allergies

(13) Other conditions not suitable for the study

Criteria for Discontinuation of Study Treatment

(1) Disease progression

(2) Occurrence of acute exacerbation of preexisting interstitial pneumonia

-

(3) Occurrence of unacceptable immune-related adverse events with CTCAE grade ≥3

pneumonitis

hepatotoxicity

hepatitis

nervous system disorder

renal disorder

eye disorder

myocarditis

-

(4) Occurrence of unacceptable immune-related adverse events with CTCAE grade ≥2

colitis/diarrhea

pancreatitis

pan-hypopituitarism

skin disorder

-

(5) Occurrence of unacceptable immune-related adverse events with CTCAE grade ≥1

encephalitis, meningitis

Guillain–Barre syndrome

myasthenia gravis

Sample Size

In this study, we set the threshold for the primary endpoint of the 1-year survival rate at 15%. Assuming a clinically meaningful 25% increase and a set expected value of 40%, 36 patients were required in this study according to the exact binomial test (2-sided α = 0.05, 1 − β = 0.9). Considering patient ineligibility, a sample size of 38 was set.

Drug Information

| Generic/working name | Atezolizumab |

| Company name | Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Roche Holding AG |

| Drug type | Anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody |

| Drug class | Antineoplastic agent |

| Dose | 1200 mg |

| Unit | mg |

| Route | i.v. |

| Schedule of administration | every 3 weeks |

Patient Characteristics

| Number of patients, male | 16 |

| Number of patients, female | 1 |

| Stage (IIIA/IIIB/IIIC/IVA/IVB/recurrent) | 2/4/2/3/3/3 |

| Age: median [interquartile ranges] | 70.0 [66.0, 73.0] years |

| Number of prior systemic therapies: median [interquartile ranges] | 1 [1, 2] |

| Performance status: ECOG | 1-13 2-0 3-0 4-0 |

| Cancer types or histologic subtypes | Adenocarcinoma, 9 Squamous cell carcinoma, 7 Non–small cell lung cancer, not otherwise specified |

Study Details

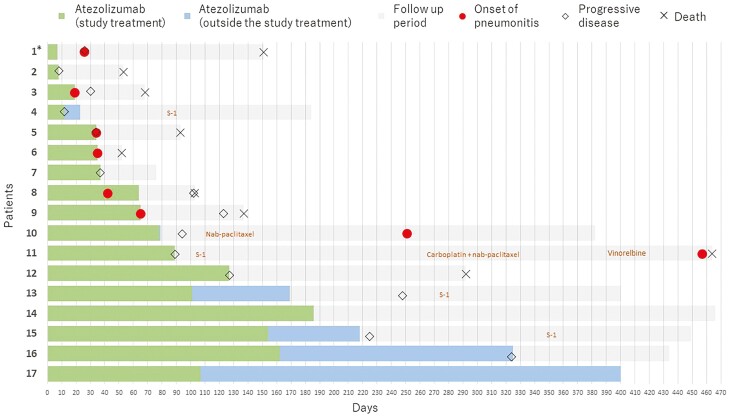

Registration began on September 2, 2019. At the time of enrollment of 15 patients, 3 patients (20%) developed grade 3 pneumonitis, so the new patient enrollment was interrupted on January 31, 2020. Two patients from whom consent had already been obtained were reintroduced, and a total of 17 patients were eventually registered (the last patient enrollment was on February 10, 2020). Subsequently, one patient with pneumonitis worsened from grade 3 to 5, and one new patient developed grade 3 pneumonitis. Therefore, the present study was terminated following the recommendation of the efficacy and safety evaluation committee.

PD-L1 expression, which was measured using the Dako PD-L1 immunohistochemistry 22C3 pharmDx assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA), was ≥50% in 7 patients (41.2%), 1-49% in 3 patients (17.6%), <1% in 4 patients (23.5%), and unknown in 3 patients (17.6%). The median %FVC and % diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide were 85.4% and 54.4%, respectively. Regarding the radiological findings of preexisting IP as judged by the central review committee, 6 patients (35.3%) had UIP patterns, 3 patients (17.6%) had probable UIP patterns, and 8 patients (47.1%) had indeterminate UIP patterns. Seven patients (41.2%) had honeycomb lung on HRCT.

The median number of delivered cycles of atezolizumab as the study treatment was 3 [interquartile range: 2, 5]. Five of 6 patients who were on treatment at the time the trial was terminated agreed to continue receiving atezolizumab as usual clinical treatment outside of this trial, with a median number of additional cycles of 3 [interquartile range: 3, 8].

For translational research on the predictive biomarkers of atezolizumab efficacy, we extracted deoxy-nucleic acids from archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissues and analyzed tumor mutational burden (TMB) and somatic variations in 409 cancer-related genes using the Oncomine Tumor Mutation Load Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US) and analyzed microsatellite instability (MSI) on a panel of Bethesda markers (BAT25, BAT26, NR21, NR24, and MONO27). In all 17 enrolled patients, consent for the use of archival tumor samples was obtained. However, due to the insufficient amount of residual tumor samples, not all items could be measured in 4 patients, and one patient could be analyzed only for MSI. For TMB, 33.3% (4/12) had ≥10 mutations per megabase (mut/Mb), and 66.7% (8/12) had <10 mut/Mb. TP53 mutation was detected in 50.0% (6/12), KRAS mutation in 25.0% (3/12), and abnormalities of RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway (including KRAS mutation) in 33.3% (4/12), and abnormalities of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in 25.0% (3/12). All cases were classified as microsatellite stable, and no cases were classified as MSI-high or MSI-low.

Primary Assessment Method

| Title | Efficacy endpoints |

|---|---|

| Number of patients screened | 17 |

| Number of patients enrolled | 17 |

| Number of patients evaluable for toxicity | 17 |

| Number of patients evaluated for efficacy | 16 |

| Evaluation method | RECIST 1.1 |

| Response assessment, PR | 1 (6.3%) |

| Response assessment, SD | 9 (56.3%) |

| Response assessment, PD | 6 (37.5%) |

| (Median) duration assessments, OS | 15.3 months (95% CI, 3.1-not reached) |

| (Median) duration assessments, PFS | 3.2 months (95% CI, 1.2-7.4 |

| (Median) duration assessments, TTF | 3.2 months (95% CI, 1.2-not reached) |

| Outcome notes | The 1-year survival rate (the primary endpoint of this study) was 53.3% (95% CI, 25.9-74.6) (Table 1). The ORR and disease control rate were 6.3% (95% CI, 0.2-30.2) and 62.5% (95% CI, 35.4-84.8), respectively. |

Secondary Assessment Method

| Title | Adverse events |

|---|---|

| Number of patients screened | 17 |

| Number of patients enrolled | 17 |

| Number of patients evaluable for toxicity | 17 |

| Number of patients evaluated for efficacy | 16 |

| Outcome notes | The updated results of major adverse events are presented in Table 2. The incidence of pneumonitis within 1 year after treatment initiation, one of the secondary endpoints, was 29.4% (95% CI, 10.3-56.0). According to the CTCAE grading, 23.5% of patients developed treatment-related pneumonitis of grade ≥3 and 5.9% of patients developed treatment-related pneumonitis of with grade 5. All 4 patients who developed grade ≥3 pneumonitis were started on high-dose corticosteroids immediately after diagnosis, with 3 patients on intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy and one on oral prednisolone 60 mg/day. The mortality rate from pneumonitis during the observation period was 17.6% (95% CI, 3.8-43.4). Except for pneumonitis, the most common grade ≥3 adverse event was dyspnea (23.5%), followed by lung infection (17.6%) and hypoalbuminemia (11.8%). |

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

| Completion | The study terminated prior to completion. |

| Investigator’s assessment | Active but too toxic as administered in this study. |

Approximately 5%-10% of patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have comorbid interstitial pneumonia (IP) at the time of diagnosis and are reported to have a poor prognosis.1 There is no significant difference in the proportion of patients with comorbid IP at diagnosis between Japan and the US. Among idiopathic IPs, the incidence of lung cancer complications varies, with Kreuter et al reporting 15.8% for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, 6.3% for nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, and 5.6% for cryptogenic organizing pneumonia.2 Common risk factors for the development of IPs and lung cancer have been reported to include smoking, environmental, and occupational exposure to toxic substances, bacterial and viral infections, and chronic tissue damage.3 In addition, microsatellite instability, loss of heterozygosity, p53 mutations, and fragile histidine triad mutations have been reported as common genetic alterations in the pathogenesis of lung cancer and IP.4,5 Pharmacotherapy for NSCLC can occasionally cause pneumonitis or acute exacerbation of preexisting IP (5%-20%), with a mortality rate of 30%-50%. Because there are only few prospective studies on patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP, there is an urgent need to establish a safe and effective pharmacotherapy, especially for second-line or later lines.

This was the first phase II study conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody in patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP. In this study, we distinguish between the terms “IP” for pre-existing interstitial lung disease and “pneumonitis” for new interstitial shadows that appeared after immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) administration. The term “pneumonitis” is usually used to refer to noninfectious causes of lung inflammation, such as those induced by anti-cancer drugs. Meanwhile, interstitial lung disease of unknown cause characterized by fibrosis and inflammation in the lung interstitium, that progresses in a chronic course, is usually described as “idiopathic IP.” In addition, when new interstitial shadows appear after ICI administration in patients with preexisting IP, it is difficult to distinguish between “pneumonitis as pure immune-related adverse events” and “acute exacerbation of pre-existing IP triggered by ICI administration.” Therefore, in this study, the appearance of new interstitial shadows after atezolizumab administration that was judged by the investigator not to be infection, heart failure, or an exacerbation of carcinomatous lymphangitis, was collectively defined as “(ICI-induced) pneumonitis.”

Because of the high incidence of severe pneumonitis, the present study was terminated and the planned enrollment of 38 patients could not be completed; therefore, only 17 patients were enrolled.6 However, the primary endpoint of 1-year survival rate was 53.3% (95% CI, 25.9-74.6), and the lower limit of the 95% CI exceeded the threshold of 15% (Table 1, Figs.1 and 2). In the OAK study on pretreated NSCLC without IP, the 1-year survival rate of atezolizumab was 55%, which was comparable with the results shown in this study.7 Furthermore, this study had comparable survival rates with the OAK study, which reported median overall survival (OS) of 13.8 months (95% CI, 11.8–15.7), median progression-free survival (PFS) of 2.8 months (95% CI, 2.6-3.0), objective response rate of 13.6%, and disease control rate of 48.9%. It is noteworthy that although IP is a distinctly poor prognostic comorbidity in patients with NSCLC,8 the efficacy and survival benefits of atezolizumab were comparable between the patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP in this study and those without IP in previous prospective trials. However, it should be considered that this study included a small number of patients.

Figure 2.

Swimmer’s plot. *, In this patient where the exclusion criteria were violated due to a history of thoracic radiotherapy, an adverse event determined by the central judgment to be “radiation recall pneumonitis” with a CTCAE grade 1 occurred.

Although no standard treatment has been established for pretreated NSCLC with comorbid IP, S-1 or docetaxel has been considered by retrospective studies to be relatively safe and has been often administered in clinical practice in Japan.9-11 However, all retrospective studies on cytotoxic agents as second-line or later therapy in patients with NSCLC and comorbid IP have shown a 1-year survival rate of at most 10%.9,12 These results were inferior to the data from the EAST-LC study on Asian patients with previously treated NSCLC without IP; that study reported a 1-year OS of 50% in both the S-1 and docetaxel groups, with a median OS of 12.8 months in the S-1 group and 12.5 months in the docetaxel group.13 Evidence on the efficacy of cytotoxic agents as second-line or later therapy in patients with NSCLC and comorbid IP is limited, and long-term survival can hardly be expected. Therefore, for patients with NSCLC with comorbid IP who have a poor prognosis and few treatment options, ICI holds great promise as the only existing treatment option that can provide long-term survival.

However, even if the balance between safety and efficacy of atezolizumab is considered, the 23.5% rate of developing grade ≥3 severe pneumonitis and the associated 17.6% mortality may be too risky (Table 2). Therefore, in order for atezolizumab to become a recommended treatment option for patients with NSCLC and comorbid IP, further investigation is required to clarify the following risk factors for the development of pneumonitis: severity, subtype, and specific radiologic findings of the preexisting IP; serum biomarkers; and the presence of specific genetic alterations. In the present report, to verify the risk factors for pneumonitis, we repeated the post hoc logistic regression analysis and included as new covariates the detected genetic alterations, such as TP53 mutation, which is a possible common etiology of lung cancer and IP.14 However, no new risk factors for pneumonitis were identified (Table 3). Although the presence of honeycomb lung on HRCT was suggested as a candidate risk factor, the result was not significant and the risk factor analysis was done post hoc on only a small number of cases. Therefore, no definitive conclusion can be drawn from these results alone. For appropriate patient selection, large observational and retrospective studies that include data, such as CT and pulmonary function tests, are needed to identify the risk factors for ICI-induced pneumonitis.

Table 2.

Updated results of major adverse events.

| CTCAE grade | All grade | Grade ≥3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | % | Total | % | |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 29.4 | 4 | 23.5 |

| Dyspnea | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 35.3 | 4 | 23.5 |

| Lung infection | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.6 | 3 | 17.6 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 11 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 94.1 | 2 | 11.8 |

| Hyponatremia | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 70.6 | 1 | 5.9 |

| Generalized fatigue | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 41.2 | 1 | 5.9 |

| Anemia | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 70.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Increased AST | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 64.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Increased ALT | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 58.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cough | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 47.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Appetite loss | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 41.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Increased ALP | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 41.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fever | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 35.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 35.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Increased creatinine | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 29.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Increased serum amylase | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 29.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hypereosinophilia | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 23.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 23.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Increased CPK | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Proteinuria | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Nausea | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hypokalemia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Palpitations | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Constipation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CPK, creatine phosphokinase.

Table 3.

Risk factors for pneumonitis.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lower limit) | (Upper limit) | |||

| Age ≥ 70 years old | 0.476 | 0.0568 | 3.99 | .494 |

| Body mass Index ≥25 | 0.350 | 0.0295 | 4.15 | .406 |

| SpO2 | 0.642 | 0.346 | 1.20 | .114 |

| % Forced vital capacity | 1.04 | 0.957 | 1.13 | .384 |

| % Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide | 0.967 | 0.886 | 1.05 | .425 |

| Indeterminate for usual interstitial pneumonia pattern1 | 0.667 | 0.0803 | 5.54 | .707 |

| Honeycomb lung on high-resolution computed tomography 2 | 12.0 | 0.936 | 154 | .056 |

| TP53 mutation 3 | 4.50 | 0.491 | 41.2 | .183 |

A univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to verify the risk of pneumonitis.

Regarding the radiological findings of pre-existing interstitial pneumonia as judged by the central review committee, 8 patients had indeterminate for usual interstitial pneumonia pattern.

Seven patients had honeycomb lung on high-resolution computed tomography.

TP53 mutations were detected in 6 patients and 11 were negative or unmeasured.

Biomarkers of efficacy are also important to consider when deciding on the choice of a high-risk treatment. Compared with previous prospective trials on NSCLC without IP, 2 previously reported trials on nivolumab in NSCLC with mild IP showed higher efficacy.15,16 The relatively high efficacy of ICI in patients with IP has been speculated to be associated with high tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI), which may also be related to the etiology of IP. However, this study did not demonstrate superior efficacy or survival benefit, compared with the data from previous studies on NSCLC without IP. Moreover, MSI was not observed in any of the cases, and TMB was not associated with efficacy (Table 4). On the other hand, our post hoc analysis results showed a tendency for longer OS and PFS in patients with PD-L1 ≥50% than in those with PD-L1 <50% (Fig. 3). On post hoc analysis, compared with patients with PD-L1 <50%, those with PD-L1 ≥50% had a tendency to have a higher 1-year survival rate (71.4% [95% CI, 38.0-not estimable] vs. 51.4% [95% CI, 11.5-91.4]), longer OS (median not estimable [95% CI, not estimable] vs. median 15.3 months [95% CI, not estimable], log-rank test P = .371) and longer PFS (median 7.4 months [95% CI, 3.7-18.6 months] vs. median 1.7 months [95% CI, 0.5-2.9 months], log-rank test P = .184). In practice, the decision to administer ICI would need careful consideration of the risks (especially pneumonitis) and benefits, with reference to PD-L1 expression.

Table 4.

Predictive biomarkers for the efficacy of atezolizumab.

| Overall survival | Progression free survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Tumor mutation burden≥ 10 mutations per megabase | 0.407 | 0.0414—4.01 | .441 | 0.687 | 0.168-2.81 | .602 |

| TP53 mutation | 1.537 | 0.212—11.14 | .671 | 1.64 | 0.422-6.38 | .475 |

| KRAS mutation | Not applicable | Not applicable | .998 | 0.215 | 0.0251-1.84 | .160 |

| Abnormality of RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway | Not applicable | Not applicable | .997 | 0.407 | 0.0812-2.04 | .274 |

| Abnormality of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway | 3.11 | 0.434-22.3 | .259 | 1.76 | 0.390-7.98 | .461 |

A univariate cox regression analysis was performed to verify whether tumor mutation burden, detected genetic mutations and pathway abnormalities could be predictive biomarkers of efficacy. Hazard ratios were calculated using patients with tumor mutation burden < 10 mutations per megabase and patients with no or unknown genetic mutations or pathway abnormalities as the control group, respectively. For tumor mutation burden, 4 patients had ≥10 mutations per megabase. TP53 mutation was detected in 6 patients, KRAS mutation in 3 patients, abnormalities of RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway (including KRAS mutation) in 4 patients, and abnormalities of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in 3 patients.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves by PD-L1 expression. Kaplan-Meier curves of (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival. Vertical lines show censored events. PD-L1 expression was assessed by the immunohistochemistry using 22C3 pharmDx assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Abbreviation: PD-L1, programmed cell-death ligand 1.

A limitation of this study was that it was a single-arm phase II trial with a small number of patients and was terminated prematurely. Therefore, definitive conclusions on both safety and efficacy cannot be drawn from the results of this study alone. In the future, accumulation of further knowledge is needed by conducting more studies on a large number of patients that have observational and retrospective designs, rather than prospective studies alone.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families, the Thoracic Oncology Research Group data center staff, and all the investigators who participated in the TORG1936/AMBITIOUS study. This study was sponsored by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). This clinical trial was retrospectively registered in the Japan Registry of Clinical Trials on August 26, 2019 (registry number; jRCTs031190084, https://jrct.niph.go.jp/en-latest-detail/jRCTs031190084). The Niigata University Certified Review Board of Clinical Research approved the protocol on July 23, 2019 (approval number, SP19005).

Contributor Information

Satoshi Ikeda, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Terufumi Kato, Department of Thoracic Oncology, Kanagawa Cancer Center, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Hirotsugu Kenmotsu, Division of Thoracic Oncology, Shizuoka Cancer Center, Shizuoka, Japan.

Takashi Ogura, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Yuki Sato, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan.

Aoi Hino, Department of Respirology, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine, Chuo-ku, Chiba, Chiba, Japan.

Toshiyuki Harada, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Japan Community Healthcare Organization Hokkaido Hospital, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan.

Kaoru Kubota, Department of Pulmonary Medicine and Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine, Nippon Medical School, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Takaaki Tokito, Division of Respirology, Neurology, and Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume, Fukuoka, Japan.

Isamu Okamoto, Research Institute for Diseases of the Chest, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Fukuoka, Japan.

Naoki Furuya, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Respiratory Medicine St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan.

Toshihide Yokoyama, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan.

Shinobu Hosokawa, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Japanese Red Cross Okayama Hospital, Kita-ku, Okayama, Okayama, Japan.

Tae Iwasawa, Department of Radiology, Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Rika Kasajima, Molecular Pathology and Genetics Division, Kanagawa Cancer Center Research Institute, Asahi-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Yohei Miyagi, Molecular Pathology and Genetics Division, Kanagawa Cancer Center Research Institute, Asahi-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Toshihiro Misumi, Department of Biostatistics, Yokohama City University School of Medicine, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Hiroaki Okamoto, Department of Respiratory Medicine and Medical Oncology, Yokohama Municipal Citizen’s Hospital, Kanagawa-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan.

Funding

This study was supported by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Conflict of Interest

Satoshi Ikeda: Chugai, AstraZeneca (RF), Chugai, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono, Taiho, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer (H); Terufumi Kato: Chugai, Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Merck Biopharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron (RF), Chugai, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck Biopharma, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda (H); AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck Biopharma, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda (SAB); Hirotsugu Kenmotsu: Chugai, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo (RF), Chugai, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Pfizer, Taiho; Takashi Ogura: Shionogi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai (H); Yuki Sato: Ono, Novartis, Taiho, Chugai, MSD, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Nippon Kayaku, Pfizer, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Takeda (H); Aoi Hino: Taiho (H); Kaoru Kubota: Taiho (C/A), Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono (RF); Taiho, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono, MSD, Chugai, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Bristol Myers Squibb, Taiho, Novartis, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Eisai (H); Takaaki Tokito: AstraZeneca, MSD, Novartis, Chugai (H); Isamu Okamoto: Chugai (RF, H); Naoki Furuya: Chugai (H); Toshihide Yokoyama: Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Chugai, Takeda, Eli Lilly, Delta-Fly Pharma (RF), Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Chugai, Takeda, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono, Taiho, Pfizer, Novartis, Nippon Kayaku (H); Shinobu Hosokawa: Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Novartis (H); Tae Iwasawa: CANON Medical Systems (RF), CANON Medical Systems, Boehringer Ingelheim (H). Hiroaki Okamoto: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, Taiho, Astellas, Eli Lilly, Merck (RF), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, MSD, AstraZeneca, Kyorin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- 1. Raghu G, Nyberg F, Morgan G.. The epidemiology of interstitial lung disease and its association with lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(Suppl2):S3-10. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kreuter M, Ehlers-Tenenbaum S, Schaaf M, et al. Treatment and outcome of lung cancer in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2015;31(4):266-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vancheri C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer: do they really look similar?. BMC Med. 2015;13:220. 10.1186/s12916-015-0478-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Demopoulos K, Arvanitis DA, Vassilakis DA, Siafakas NM, Spandidos DA.. MYCL1, FHIT, SPARC, p16(INK4) and TP53 genes associated to lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6(2):215-222. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uematsu K, Yoshimura A, Gemma A, et al. Aberrations in the fragile histidine triad (FHIT) gene in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cancer Res. 2001;61(23):8527-8533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ikeda S, Kato T, Kenmotsu H, Ogura T, et al. A phase 2 study of atezolizumab for pretreated NSCLC with idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(12):1935-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raghu G, Nyberg F, Morgan G.. The epidemiology of interstitial lung disease and its association with lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(Suppl 2):S3-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe N, Niho S, Kirita K, et al. Second-line docetaxel for patients with platinum-refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer and interstitial pneumonia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76(1):69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minegishi Y, Gemma A, Homma S, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias related to chemotherapy for lung cancer: nationwide surveillance in Japan. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(2):00184-02019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kakiuchi S, Hanibuchi M, Tezuka T, et al. Analysis of acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease associated with chemotherapy in patients with lung cancer: a feasibility of S-1. Respir Investig. 2017;55(2):145-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kato M, Shukuya T, Takahashi F, et al. Pemetrexed for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nokihara H, Lu S, Mok TSK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of S-1 versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (East Asia S-1 Trial in Lung Cancer). Ann Oncol. 2017;28(11):2698-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demopoulos K, Arvanitis DA, Vassilakis DA, Siafakas NM, Spandidos DA.. MYCL1, FHIT, SPARC, p16(INK4) and TP53 genes associated to lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6(2):215-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fujimoto D, Morimoto T, Ito J, et al. A pilot trial of nivolumab treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with mild idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fujimoto D, Yomota M, Sekine A, et al. Nivolumab for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with mild idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: a multicenter, open-label single-arm phase II trial. Lung Cancer. 2019;134:274-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.