Abstract

Venezuelans constitute the second largest displaced population globally. Most Venezuelans move to Colombia, where the government incorporates them through administrative legalization programs. While the international community has praised Colombia’s governmental response, this article demonstrates that these programs provide Venezuelans with liminal legality. Existing liminal legality research indicates that recipients are highly aware of the fragility of their legal status because they live in hostile political contexts with complicated legalization procedures. However, the present article argues that liminal legality in inclusive political contexts such as Columbia—with straightforward application procedures, pro-immigrant political discourse, and weak immigration enforcement—hide this legal status’ fragility and illegality production features. Empirically, the study draws on in-depth interviews with Venezuelan migrants in Bogotá, D.C. Findings show that most liminal legality recipients want to reside legally in Colombia and experience their legal status with a sense of state protection. Though, their sense of security inhibits their efforts to acquire legal permanent residency. Conversely, undocumented Venezuelans tend to have the fewest resources before emigrating, cannot meet the liminal legality requirements, and experience all forms of legality as unattainable. Broadly, governments who seek to legalize migrants need to include direct pathways to citizenship and lower the legal residency requirements.

Keywords: Liminal Legality, Venezuelan Migration, Immigration Policy and Administration, Colombia Immigration

INTRODUCTION

Over 5.9 million Venezuelans have been displaced, fleeing widespread human rights violations, food shortages, violence, economic deterioration, and a crumbling healthcare system (UNHCR 2018; R4V 2021). Currently, Venezuelans are the second largest population of forcefully displaced persons globally; Colombia is their leading destination (R4V 2021). As of 2021, Colombia hosts 1.7 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees (R4V 2021).

In response, Colombia’s migration authorities have used executive action to create seven distinct Special Residency Permits for Venezuelans (Permiso Especial de Permanencia, PEP) between 2017 and 2020 (see Appendix A). The PEPs provide Venezuelans with two years of legal residency, work authorization, and the right to public healthcare and education (Selee et al. 2020; Migración Colombia 2020). Moreover, the PEP applications are free and can be accessed online, with applicants receiving their permits automatically (Gandini, Ascencio, and Prieto 2019; Selee et al. 2019). Further, Colombian President Iván Duque announced the Temporary Protection Status for Venezuelan Migrants program (Estatuto de Protección Temporal para Migrantes Venezolanos, ETPV) in February 2021. PEP recipients who register for the ETPV census are given up to 10 years to figure out how to acquire legal permanent residency through a separate, high requirement, and more complex visa category (Migración Colombia 2021).

The international community has praised the Colombian government’s humanitarian response to the Venezuelan exodus, and prominent Colombian political leaders have expressed their commitment to continue welcoming Venezuelans (Restrepo, Jaramillo, and Torres 2018; Palma-Gutiérrez 2021). Despite the receptive political discourse and legalization opportunities, 59% (1 million) of Venezuelans in Colombia are undocumented (R4V 2021). The question remains: how do Venezuelan migrants experience their legalization process, and why are so many Venezuelans undocumented despite the appraised governmental policy welcome.

To answer this question, it is crucial to understand that the PEPs and ETPV programs only provide liminal legality. Cecilia Menjívar introduced the concept of liminal legality to capture how the United States’ Temporary Protection Status from deportation generates a tenuous in-between legal status—not documented but not undocumented—without a path to citizenship (2006). The renewal of liminal legality depends on executive officials’ discretion and recipients’ ability to pay high fees and navigate complex application procedures (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015; Menjívar, Agadjanian, and Oh 2020). The Colombian PEPs and ETPV do not provide a direct path to legal permanent residency or citizenship (Selee et al., 2019), and their renewal depends on executive discretion (Castro 2020). Therefore, the current or new Columbian presidents can eliminate both programs before the 10 years and leave beneficiaries undocumented (Migración Colombia 2020; Migración Colombia 2021). In places with anti-immigrant political discourse and high immigration enforcement, liminal legality recipients are highly aware of the fragility of their legal status and live with the threat of deportation (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015; Menjívar, Agadjanian, and Oh 2020).

However, migrants may experience and navigate the Colombian liminal legality differently because the applications are free and straightforward and coexist with pro-immigration political discourse and low immigration enforcement (Castro 2020; Global Detention Project 2020). Thus, the question remains: How do welcoming political and legal contexts impact immigrants’ understanding of the law and approach to their legalization process?

The present paper expands the concept of liminal legality by examining how liminal legality in welcoming contexts might produce illegality and shape migrants’ approach to their legalization. We know that migrants’ understanding of the law plays affects how they navigate legal institutions. In hostile immigration contexts, migrants with positive perceptions of the law tend to strategize and garner resources to resolve legal problems while those with negative perceptions do not (Abrego 2011, 2018; Solórzano 2021). Moreover, pro-immigration political discourse can coexist with exclusionary immigration policies and practices (Acosta and Freier 2015; Basok and Wiesner 2018). The requirements of legalization programs often leave migrants with the least resources undocumented (De Genova 2004; Menjívar and Kanstroom 2013). Thus, to examine how a welcoming governmental context affects how migrants understand and navigate liminal legality procedures, I draw on 30 in-depth and semi-structured interviews and 20 follow-up interviews with Venezuelan immigrants in Bogotá, Colombia. Approximately half of the respondents are PEP recipients; the other half are undocumented.

Findings show that Colombia’s political and legal contexts create an allure of safety that leaves PEP recipients at risk of illegality. Almost all PEP holders feel secure in their liminal legality and capable of navigating Colombia’s legal institutions to secure legal permanent status. However, due to officials’ ongoing patchwork of legalization programs, most PEP recipients are misinformed about the durability of their legal status, procedures to renew their permit, or legal permanent residency application process. Moreover, Venezuelans from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are derailed into illegality and feel stuck in this legal status because they did not have the resources to meet the requirements of any visa category. Broadly, I argue that the seemingly welcoming political and legal contexts hide the fragility and illegality production mechanisms of liminal legality programs.

In the following sections, I situate my contribution to the concept of liminal legality within the literature on Colombian governmental policy responses to Venezuelan immigration. Then, I provide an overview of the methods, present the main findings, and discuss the study’s implications.

THEORY AND BACKGROUND

Liminal Legality

Various concepts describe the uncertainty of temporary legal residency programs worldwide. Some immigrants in Mexico and Canada confront “precarious legality” because complicated application procedures and high requirements make legal permanent residency practically unattainable (Basok and Wiesner 2018; Goldring and Landolt 2021). Other migrants face “semi-legality” or “differential inclusion” because they have rights in some realms but not in others (Kubal 2013; Baban, Ilcan, and Rygiel 2017). These tenuous legal statuses are linked to precarity. Recipients often live in dense and crumbling housing, endure food shortages and exploitative work conditions, face exclusion within institutional settings, and experience stunted socioeconomic mobility (Kubal 2013; Abrego and Lakhani 2015; Baban et al., 2017; Basok and Wiesner 2018; Hamilton, Patler, and Savinar 2020; Menjívar et al., 2020). Although these concepts are insightful, they do not fully capture how state actors intentionally produce legal uncertainty for migrants.

The present article expands on the liminal legality concept because it illustrates how state actors use executive discretion to prevent the permanent settlement of immigrants (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015). Cecilia Menjívar defines liminal legality as a legal status “characterized by its ambiguity, as it is neither an undocumented status nor a documented one but may have the characteristics of both” (2006: 1008). She uses the concept to describe the situation of immigrants in the United States with Temporary Protected Status, or TPS (Ibid).

Broadly, liminal legality production consists of four characteristics. First, authorities at the executive branch of government have the discretion to create, change, and terminate liminal legality programs without congressional input (Chacon 2015; Menjívar et al., 2020). Second, liminal legality does not provide migrants a path to citizenship, and it is not a stage in a linear process from undocumented to documented (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015; Menjívar et al., 2020). However, having liminal legality is better than being undocumented (without work authorization or protection from deportation) and worse than having legal permanent residency and citizenship—which gives people the right to have rights (Menjívar 2006; Celbuko 2014; Menjívar et al., 2020). Third, liminal legality applications are highly inaccessible (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015; Menjívar et al., 2020). Immigration authorities announce renewal dates within short time frames, and migrants often need legal counsel to fill out the complicated application (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015). Moreover, liminal legality imposes an obligation on immigrants to pay high fees (e.g., US$495) for protection from deportation and maintain a clean criminal record to qualify for renewals (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015).

Finally, liminal legality recipients live with a threat of deportation and are highly aware of the fragility of their legal status (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015; Hamilton et al., 2020; Menjívar et al., 2020). The last two characteristics might work differently in other political and legal contexts. The concept of liminal legality was created to explain TPS in the United States, where the immigration enforcement apparatus is robust, anti-immigrant political discourse is prevalent, and application procedures are complicated (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015). Thus, we know less about how liminal legality works in more inclusive contexts to immigrants.

Liminal Legality in Inclusionary Governmental Contexts

The present study advances the concept of liminal legality by examining how this legal status operates within contexts with less robust immigration enforcement infrastructures, pro-immigration political discourse, and more accessible applications. Liminal legality within more welcoming contexts can change how immigrants perceive and navigate their legalization process. We know that migrants’ legal consciousness—or understanding of the law in everyday life—is shaped by their social position (Ewick and Silbey 1998; Abrego 2011, 2018) and political discourse (Solórzano 2021). Additionally, people’s legal consciousness shapes their behavior (Hernández 2010) and affects how migrants navigate their legalization opportunities (Abrego 2011, 2018). For instance, undocumented immigrants in the United States’ hostile context (along with other disenfranchised people) who fear and distrust legal institutions and actors refrain from mobilizing resources to resolve legal problems (Ewick and Silbey 1998; Hernández 2010; Abrego 2011; Solórzano 2021).

Conversely, when marginalized people experience positive social, political, and legal inclusion (such as access to liminal legality), come to understand the law as a game of skill (Hernández 2010; Abrego 2011, 2018; Solórzano 2021). Their “with the law” legal consciousness orientation motivates them to strategize and mobilize resources to resolve legal problems (Ibid).i We know less about how more welcoming contexts affect migrants’ legal consciousness. Thus, the study examines how the inclusionary political discourse, decreased threat of deportation, and straightforward liminal legality applications distinctly impact migrants’ legal consciousness and the ways they approach their legalization process.

Furthermore, there is reason to believe that liminal legality programs in more welcoming contexts also produce illegality—or how immigration policies’ restrictions create and sustain categories of undocumented immigrants (De Genova 2004; Alfonso 2013; Menjívar and Kanstroom 2013). In many Latin American countries, political leaders use pro-immigration discourse though they support policies that exclude some categories of immigrants from legal residency (Acosta and Freier 2015; Basok and Wiesner 2018). Across the Americas, legalization programs produce illegality among low-income immigrants when they have high fees, impose time limits, are not widely diffused, or require hard-to-access state-issued documentation (Menjívar and Kanstroom 2013; Sandoval 2014; Alfonso 2013; Gandini et al., 2019). Thus, this study examines how liminal legality requirements produce illegality in welcoming contexts and how migrants navigate these complications.

In the following sections, the paper describes how the Colombian government has responded to an unprecedented and rapid increase in Venezuelan migrants by creating liminal legality disguised as governmental welcome.

Background: Colombia’s “Welcoming” Liminal Legal Context for Venezuelan Migrants

According to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (UNHCR, 2018), Venezuelans are fleeing widespread human rights violations, crime, and crises. They represent the second-largest displaced population in the world and the biggest in Latin America’s history (Selee et al. 2019; R4V 2021). Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro (2013-present) and his administration have engaged in widespread human rights violations since 2017, including arbitrary detentions, torture, and excessive use of force against political opponents (UNHCR 2018). The country’s public healthcare system has collapsed, and the state has failed to provide medical staff with sufficient supplies to treat people (UNHCR 2018). Additionally, the government’s economic and social policies have resulted in an economic recession, hyperinflation, and widespread shortages of food and essential goods (UNHCR 2018). Consequently, millions flee the country because they do not have access to adequate food, healthcare, and safety (UNHCR 2018).

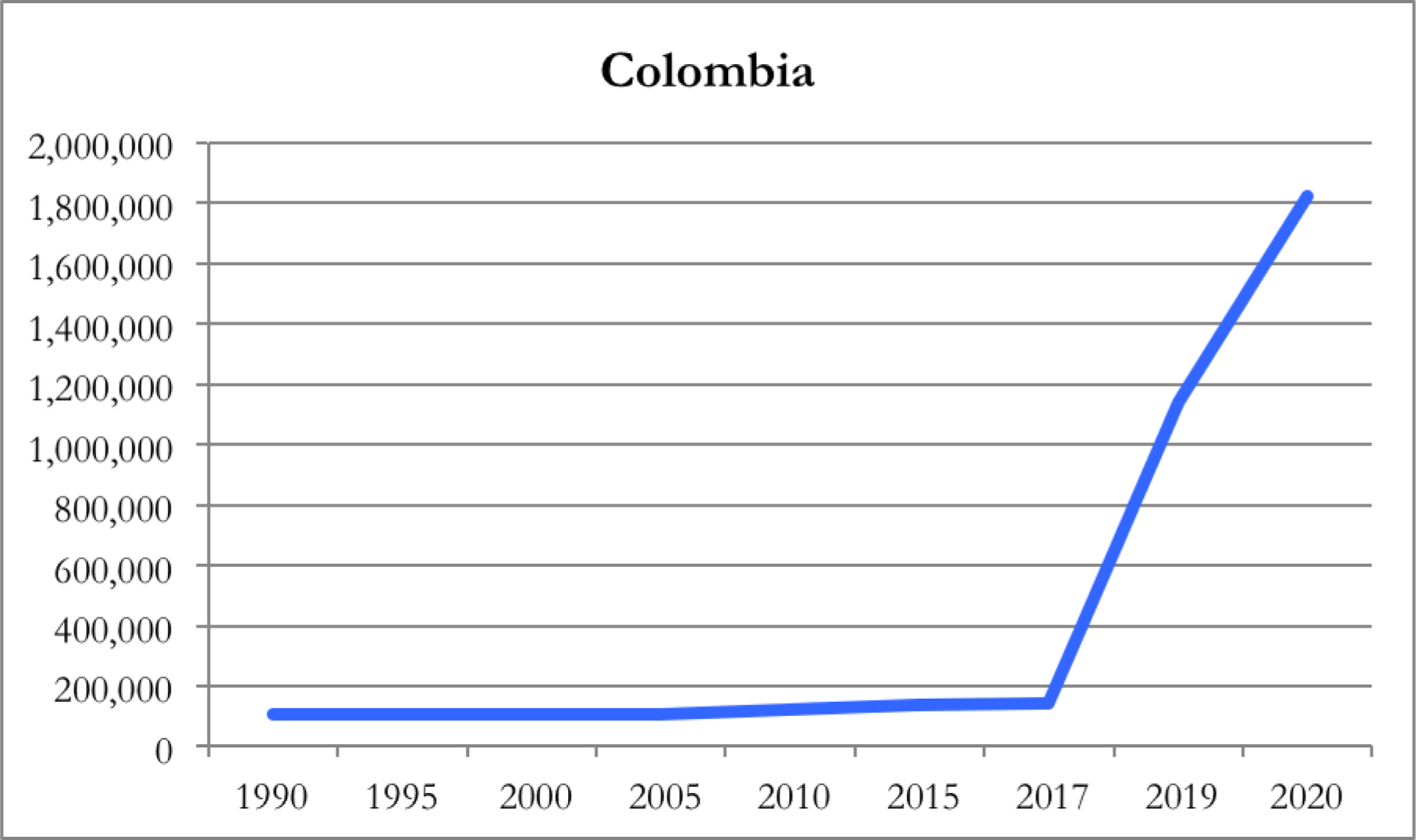

Colombia is the top destination for Venezuelans; 29% of migrants have moved there (R4V 2021). As seen in figure 1, Colombia’s international migrant stock multiplied between 2017 and 2020, an unprecedented increase. Until 2010, Colombians migrated to Venezuela, but the migration flow reversed due to the multiple crises that have recently unfolded (Alvarez 2007; Restrepo et al., 2018; Aliaga Sáez and Flórez de Andrade 2020). Currently, most Venezuelans relocate to Colombia because of its geographic proximity, cultural similarities, and historic migratory flows (Restrepo et al., 2018; Aliaga Sáez and Flórez de Andrade 2020).

Figure 1. International Immigrants in Colombia, 1990–2019.

Data from 1990–2020 is based on author’s analysis of the UN Migrant Stock data. The 2020 number is based on estimates from Migration Colombia and only counts international immigrants from Venezuela (2020).

The Colombian government mainly relies on its legal immigration system, instead of asylum, to legalize Venezuelans. Officials want to avoid the public and political costs of incentivizing more inflows through refugee resettlement support (Selee et al. 2019; Acosta, Blouin, and Freier 2019). Nonetheless, the Colombian government has ratified the United Nations’ Refugee Convention of 1951 and Protocol of 1967, which award refugee status to individuals who can prove they have a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”ii (Cancillería de Colombia 2020). The government also signed onto the Cartagena Declaration of Refugees of 1984, which expands the category of protection to people fleeing generalized violence, foreign invasions, domestic conflicts, human rights’ violations, and other circumstances (Ibid). Although most Venezuelans qualify as refugees under these agreements, officials do not widely apply them. As of December 31, 2020, the government had recognized only 771 Venezuelans as refugees, and only 19,600 asylum claims were pending review (R4V 2021).

Colombia’s legal immigration system was not prepared to process Venezuelan migrants because the country does not have an immigration law, so officials rely on executive discretion to manage migratory flows (Castro and Milkes 2018; Castro 2020). The last immigration law, N° 48 of 1920, was deemed unconstitutional in 2016iii because it contained invalidated eugenics-based requirements (Restrepo et al., 2018; Castro and Milkes 2018). Efforts to pass a new immigration law have failed due to a lack of funding and political will (Castro and Milkes 2018; Aliaga and Flórez de Andrade 2020).

For decades, agencies of the executive branch of government have managed immigration with high discretionary power (Ciurlo 2015). In 2011, Law N° 1465 created the Special Administrative Unit for Migration in Colombia—hereafter, Migration Colombia—under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Castro 2020). Authorities of Migration Colombia have the jurisdiction to manage immigration through administrative resolutions and directives and enforce these policies with administrative sanctions (Castro and Milkes 2018; Castro 2020). Currently, immigration authorities use Decree N° 1067 (2015) and the Resolution N° 6045 (2017) to regulate immigrant admissions, deportations, and expulsions (Circulo 2015; Castro and Milkes 2018). These administrative actions have visas with high requirements, are inflicted by legal ambiguity, and have limited articulation with other national laws (Castro and Milkes 2018; Castro 2020).

Furthermore, between July 2017 and February 2021, Colombian officials used their executive discretionary power to create eight programs to legalize Venezuelan immigrants. Seven programs are PEPs that provide migrants two years of temporary legal residency, work authorization, and the right to healthcare and education. To qualify for five PEPs, Venezuelans needed to have a passport stamp validating their legal entry, a clean criminal record, and no pending deportation order (Migración Colombia 2020; see Appendix A for detailed timeframes). Two other PEPs were designed for undocumented Venezuelans without valid passports. Specifically, between April 8 and June 8 of 2018, the government conducted a census of undocumented Venezuelans with state-issued identification cards and clean criminal records through the Administrative Registry of Venezuelan Migrants program (RAMV). Fearing a nativist backlash, the government did not announce that those who registered for the RAMV would qualify for liminal legal status via the RAMV-PEP. Thus, only 440,000 Venezuelans registered for the RAMV and only 272,000 obtained a RAMV-PEP (Selee et al. 2019).

Moreover, on January 28, 2020, the Ministry of Labor passed Decree N° 117 to give undocumented Venezuelans’ access to the PEP for the Promotion of Formalization (PEP-FF) if they secure a formal work contract, have a Venezuelan ID, and clean criminal record without a deportation order. However, most undocumented Venezuelans do not qualify because they cannot access the formal labor market (Chaves-González and Echeverría-Estrada 2020; Gandini et al., 2019). The PEPs, PEP-RAMV, and PEP-FF provide two-years of temporary legal residency to a limited number of Venezuelan immigrants while most Venezuelans remain undocumented (Gandini et al., 2019). To resolve this problem, Colombian President Iván Duque created the ETPV (2021) program to give PEP holders who register for a census up to 10 years to acquire legal permanent residency via the separate R-Visa application process (Migración Colombia 2021).

The PEPs and their extension via the ETPV provide liminal legality with a flavor of state inclusivity. Table 1 compares the characteristics of liminal legality programs in contrasting contexts. “Antagonistic contexts towards immigrants” refer to governments with high immigration enforcement and anti-immigrant political discourse. Conversely, “welcoming contexts towards immigrants” refer to governments (i.e., Colombia) with weak immigration enforcement and pro-immigrant political discourse. The rows represent the main characteristics of liminal legality and show that Colombia’s liminal legality shares some characteristics with other tenuous programs in hostile contexts. For example, Colombian Presidents and immigration authorities also have discretionary power to end, renew, or expand the PEPs and ETPV without congressional oversight and if their political calculations deem it necessary.iv Further, the PEPs and ETPV do not provide a direct pathway to citizenship; the ETPV only extends the liminal legality period by 10 years.

Table 1.

Liminal Legality in Restrictive versus Welcoming Immigration Legal Context

| Liminal Legality Characteristics | Antagonistic Context towards Immigrants | Welcoming Context towards Immigrants (Colombia) |

|---|---|---|

| Renewal depends on executive officials’ discretion | Yes | Yes |

| Temporary and without a path to citizenship | Yes | Yes |

| Applications are highly inaccessible | Yes | No |

| Recipients are aware of legal status’s fragility and the threat of deportation | Yes | Unknown (possible no) |

On February 8, 2021, President Iván Duque introduced Temporary Protection Status for Venezuelan Migrants (Estatuto de Protección Temporal para Migrantes Venezolanos, ETPV) and claimed that this program would give recipients ten years to secure legal permanent residency. However, the administrative action’s text does not specify the mechanism towards legal permanent resident status, and the program can end before the ten years, which will leave ETPV holders undocumented (Migración Colombia 2021).

However, migrants in welcoming contexts might experience liminal legality differently because applications are more accessible, political discourse is more favorable to immigrants, and the threat of deportation is lower than in hostile contexts. For example, Colombia’s PEP and ETPV applications are easy and accessible, with no fees. Venezuelan migrants fill out their PEP applications online and automatically receive a printable liminal residency card (Migración Colombia 2020). Furthermore, the Colombian border surveillance, detentions, and deportation infrastructure have less capacity and are significantly less intense than the United States (Global Detention Project 2020; Castro 2020). Finally, Colombian government officials claim they are committed to protecting Venezuelans’ legalization (Presidencia 2018; Restrepo et al., 2018; Palma-Gutiérrez 2021). For example, in his speech before the United Nations, Colombian President Duque committed to promoting Venezuelans’ legality and integration because the two countries are “united by fraternity” and a sense of kinship (Presidencia 2018). The international community has validated this pro-immigrant political discourse and applauded the Colombian government’s policy efforts (Restrepo et al., 2018; European Parliament 2018; Selee et al. 2019; Palma-Gutiérrez 2021). Thus, the PEPs and ETPV might create a resemblance of governmental receptivity and legal durability among Venezuelans. Some Venezuelan immigrant leaders believe that Colombian officials have done everything they could to support Venezuelans’ access to legal residency, the labor market, and other rights (Aliaga Saéz, Sicard, and Flórez de Andrade 2020).

Nonetheless, the positive governmental reception might overshadow the tenuousness and illegality production of the liminal legality programs. For example, even the recent and acclaimed ETPV has exclusionary features. This program is only available to recipients of existing PEPs, undocumented Venezuelans who can provev that they were in Colombia before January 31, 2021, and Venezuelans who enter the country between May 29, 2021, and May 28, 2023 with passports and through official border checkpoints (Migración Colombia 2021: 5; see Appendix A). Current and future Venezuelan migrants who do not meet these requirements will likely end up undocumented.

Moreover, immigration authorities burden Venezuelan migrants to figure out how to secure legal permanent residency via the Residency visa categories before the ETPV ends although most cannot meet this visa’s requirements (Gandini et al., 2019; Palma-Gutiérrez 2021; Migracíon Colombia 2021). For example, the fee is about US$252–300 (Resolution N° 6045 of 2017), which is more than the monthly minimum wage for a family of four (DANE 2019). Further, migrants who want access to legal permanent residency will need to study information in various parts of the Migration Colombia website and the “Decreto Unico.” This decree is challenging to navigate; it is 150 pages long and includes information about the causes for admission, deportation, expulsion, the cancelation of a visa, and other technical information about arms trafficking maritime relations (Castro 2020). In sum, the governmental welcome likely conceals the fragility and illegality production features of the liminal legality programs.

DATA AND METHODS

The present study draws on 50 semi-structured in-depth interviews (30 extended and 20 follow-up) with Venezuelan immigrants in Bogotá, Colombia, to examine how a welcoming political and legal context impacts the functions of liminal legality and migrants’ understanding of their legalization process. The follow-up interviews helped us deepen our understanding of themes that emerged inductively through the data collection process. Full-length interviews ranged from one to two-and-half hours; follow-up interviews tended to be approximately half an hour long. Data collection occurred between 2018 and 2020 with Venezuelan citizens over 18 years old who lived in Colombia for more than three months and were immigrants (I did not interview tourists). Sixteen of the 30 interviewees were undocumented, 12 had a PEP, and 2 were on the path to citizenship. Data collection took place in Bogotá D.C., Colombia, because Venezuelan immigrants tend to concentrate there (Gandini et al., 2020).

Respondents were recruited using a snowball-sampling frame. Two research assistants tapped into their social networks to increase sample variability. They helped recruit interviewees with different immigration legal statuses who lived in different neighborhoods and came from varying socioeconomic situations in Venezuela. Interviewees also helped to recruit other respondents by referring us to their family and friends. Between 2018 and March 2020, interviews occurred wherever respondents felt most comfortable, so locations included cafes, parks, libraries, and interviewee homes. During the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted over the phone.

As seen in Table 2, Venezuelan interviewees were, on average, 29 years old. Eighteen respondents identified as women, 12 as men, and none identified as non-binary. Approximately half of participants had a high school diploma or less, grew up in low socioeconomic households in Venezuela, and lived in households below the poverty line in Colombia.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Interviewees in Colombia (N=30)

| Demographic Characteristics | # or Mean (Range) |

|---|---|

| Total interviews | 30 |

| Average Age and Range | 29 (18 to 48) |

| Women | 18 |

| Men | 12 |

| Non-binary | 0 |

| Educational attainment | |

| High school or less | 14 |

| Some college or technical college degree | 4 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 12 |

| Socioeconomic background in Venezuela* | |

| Middle-high to high | 5 |

| Middle | 8 |

| Low | 17 |

| Average monthly household income in destination country |

US$217 (US$0 to US$547) |

| Monthly poverty line for a household of four** |

US$289 |

| Number households below the monthly poverty line |

16 |

Extreme hyperinflation makes quantitative measures of respondents’ household income in Venezuela obsolete. To gauge the respondents’ socioeconomic backgrounds in Venezuela, we examined neighborhood, household income, the respondents and their parents’ educational attainment, and their occupation and industry. Low socioeconomic situation captures Venezuelans who grew up in low-income neighborhoods and households that struggled to pay necessities even before the economic crisis (e.g., rent and utilities). Further, they and at least one parent had not attended college and worked in low-skill and poorly enumeration jobs (e.g., janitorial services). Conversely, Venezuelans from middle socioeconomic backgrounds grew up in middle-class neighborhoods and households that could pay for necessities and other luxury items and services (e.g., vacations within the country). Additionally, they and at least one parent had finished college, owned small businesses, or worked as professionals in the formal section. Finally, Venezuelans from upper-mid-upper- to upper-socioeconomic neighborhoods and households could purchase multiple luxury items and services. Moreover, they and their parents had university degrees and worked in high-skill and highly enumerated occupations and industries.

The estimates of the poverty line for a household of four refer to COP 1,112,516 for 2018 in Bogota, Colombia (DANE 2019).

The in-depth, semi-structured interview protocol was developed and modified as new themes emerged during the data collection process. Interviewees were asked to describe their socioeconomic situation in Venezuela, why they decided to emigrate, and how long they wanted to reside in Colombia. Also, interviewees were asked to describe how they entered Colombia, any interaction they have had with immigration personal, and their legalization process (or failed attempts to acquire legal residency). If interviewees had not initiated a legal residency procedure, I asked them to explain why. In follow-up interviews, I asked interviewees whether they felt welcomed by the Colombian government and to describe the requirements and procedures for the PEPs’ renewal, Migrant Visa, and naturalization. Finally, I asked participants how their immigration status affected their sense of safety, employment opportunities, and access to other services.

I analyzed interview data using an inductive process and with the HyperResearch software. I used pseudonyms and removed identifying information because interviews are confidential. First, I examined how informed PEP recipients are about their legal status’s liminality as well as the procedures and requirements they need to meet to acquire the Migrant Visa. This visa provides a mechanism for transitioning to permanent legal residency and citizenship. Respondents are coded as misinformed if they believed the PEP would translate into legal permanent residency, misunderstand PEP renewal procedures, or do not understand the requirements of the Migrant Visa. PEP recipients are considered informed if they are aware the PEPs do not provide a path to legal permanent residency, know their renewal depends on the grace of immigration authorities, and understand how to acquire the Migrant and Residency Visas. Furthermore, I coded interviews as either feeling mostly safe and secure with their PEP or mostly scared and uncertain about their ability to continue residing in Colombia with legal status.

Finally, for undocumented Venezuelans, the analysis focuses on their possibilities for acquiring legal residency status in Colombia. As of 2020, undocumented Venezuelans have one of four options. They can: (1) re-enter the country with a stamped passport to qualify for most PEPs or the Migrant Visa (the latter option also requires US$250–300); (2) acquire a formal labor contract to access the PEP-FF; (3) marry a Colombian citizen or have a child in Colombia to qualify for family reunification and save up US$250–300; (4) wait for a new regularization program. Respondents face various obstacles in meeting all requirements for one of these four possibilities. The analysis gauges respondents’ resources and ability to overcome these obstacles and access a path to legality. Moreover, I code how respondents feel about their possibility of having legal residency (mostly hopeful or hopeless).

RESULTS

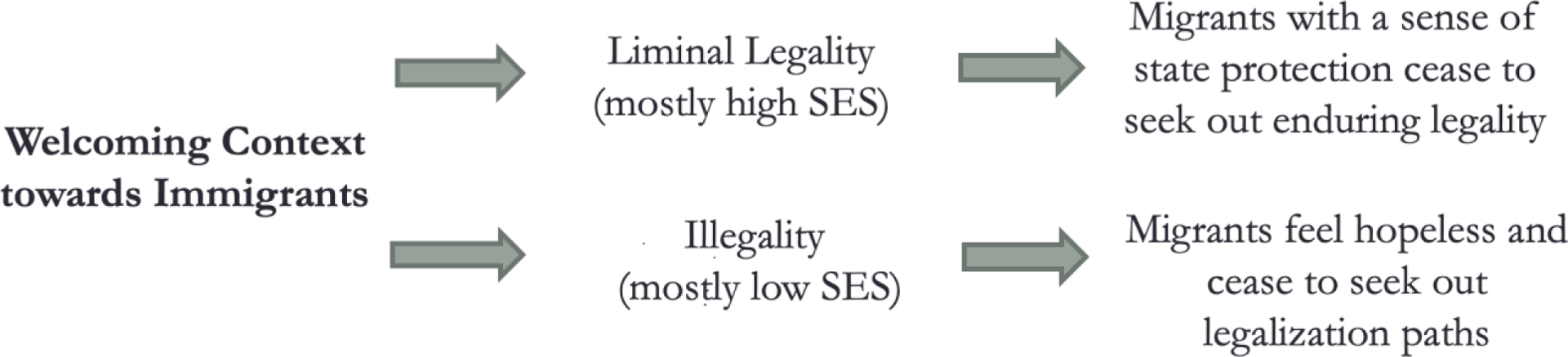

As seen in Figure 2, findings show that Colombia’s welcoming context affects Venezuelan migrants’ legalization in two ways. First, the pro-immigrant political discourse, low deportation threat, and straightforward applications obscured the fragility of the liminal legality among recipients. Most liminal legality recipients (9 out of 12) were from middle to high socioeconomic backgrounds in Venezuelan and had a “with the law” legal consciousness. However, the inclusive political context and feasibility of acquiring and renewing their PEPs created a sense of security that anesthetized their urgency to activate resources and strategies to secure more enduring legality. Second, the liminal legality programs produce illegality among the most vulnerable Venezuelan migrants. Most undocumented interviewees (14 out of 16) came from low socioeconomic backgrounds in Venezuela and did not have the resources to meet the requirements of any of the Colombian legal residency categories. Their exclusion in the backdrop of the seemingly inclusive governmental contexts fostered a sense of hopelessness about ever acquiring legal residency.

Figure 2.

The Impact of Welcoming Contexts on Immigrants’ access to Liminal Legality, Legal Consciousness, and Navigation of Legalization Possibilities

Liminal Legality with a False Sense of Security

Specifically, interview data shows that pro-immigrant political discourse, the feasibility of acquiring PEPs, and immigration authorities’ patchwork of legalization procedures create a false sense of safety, which leaves Venezuelan immigrants vulnerable to illegality. Most PEP recipients (9 out of 12) wanted to stay in Colombia indefinitely but had outdated or inaccurate information about their PEP’s longevity and renewal and how to acquire legal permanent residency and citizenship through the Migrant or Residency Visas. Only three PEP recipients knew how to acquire legal permanent residency in Colombia, but they felt stuck in liminal legality because they could not meet the Migrant Visa’s requirements.vi

Nonetheless, most PEP recipients did not feel a sense of urgency to figure out how to secure permanent legal residency or citizenship. The Colombian migration authorities had been automatically renewing their PEPs every 90 days for up to two years. The first recipients of this program were able to renew their PEPs after two years. Thus, most interviewees with PEPs assumed that such easy renewals would continue indefinitely and did not fear deportation. Almost all PEP holders believed the Colombian government welcomed them and would preserve their legal residency. In this manner, the PEP application and renewal’s feasibility coupled with the seemingly welcoming governmental reception foster a sense of security among PEP recipients, which obscures the liminal legality’s fragility.

PEP recipients ranged in their misinformation about how to acquire legal permanent residency. At one end of the misinformation continuum, some interviewees erroneously believed their PEPs provided a path to citizenship. Such was Julian Ortiz’s situation. He was 32 years old when he immigrated to Colombia through the official border checkpoint in San Antonio with his passport. Julian has a technician college degree in financial administration and decided to emigrate to Colombia because he did not earn enough to support himself. He also wanted to send his struggling parents remittances. Julian resides in Bogotá, where he works in a chocolate factory’s assembly line. He wants to stay in Colombia indefinitely and is confident he will do so with legal residency. Julian describes his PEP’s legalization process as a positive experience:

I completed the application at a cybercafé. They asked for basic information. … If your passport was stamped, … you get the permit. … I printed it, placed a photo … and got it laminated.

Julian quickly obtained liminal legality because he had money in Venezuelan to get a passport and enter Colombia legally. The PEP helped him find employment in the formal labor market and access healthcare. Thus, Julian felt welcomed in Colombia. Moreover, Julian wants to stay in Colombia, but when asked if he knew how to get permanent residency, he responded:

I don’t know. I have not researched anything. I think that I am ok with the [PEP] permit. …They [Migration authorities] are renewing my [PEP] residency. … I’ve heard that they did a census to legalize us. … I got an email questionnaire from Colombia Migration asking if I wanted to stay in the country and form a family. … The day I have to fill out the application [for a different visa], I will figure it out.

At the time of the interview, Julian must figure out how to apply to one of the Migrant Visa categories to remain in Colombia legally, as the renewal of his PEP was not guaranteed. Nonetheless, Julian believes the PEP will help him transition to permanent residency and citizenship. All of his interactions with Colombia’s immigration officials have been positive, he does not fear deportation, and he senses that authorities were already securing his transition into permanent residency.

Several other PEP recipients were aware that immigration authorities could use their discretion to stop renewing the PEPs but did not have adequate information about how to get the Migrant or Residency Visas to remain in Colombia with legal permanent status. However, they did not worry much about applying because they did not fear deportation and expected the Colombian government to provide them a path to citizenship. Such was the experience for Rocio Vargas who decided to emigrate when she was 31 years old because she struggled to find and buy food. She has a university degree in nursing and ran a small business in Maracaibo, Venezuela. Rocio wants to stay in Bogotá for the foreseeable future because she has a job as a nurse. She feels secure with her PEP and welcomed by the Colombia government because:

The PEP’s application is straightforward. … I applied in the Migration Colombia’s webpage. It has given me many benefits. … As long as I follow the laws here, I will be ok. … I feel welcomed by the government, and I think immigration will give us [PEP holders] permanent legal residency. … I’ve read the Venezuelan Consulate and the Migration Colombia websites. … To renew it [the PEP], I must let it expire, and then I reapply. Then, I must go to border checkpoints, reenter the country, and get my passport stamped again. … My goal is to become a naturalized citizen, so I do not have to continue renewing the PEP.

Interviewer: Have you read anything about the Migrant Visa?

Rocio: I have not seen anything about the Migrant Visa … I plan to figure out how to get citizenship.

The pro-immigrant political discourse and simplicity of acquiring the PEP makes Rocio feel welcomed and protected by the Colombian government and confident she can figure out how to get citizenship without legal counsel. She is aware that her PEP lasts two years and plans to renew it until she becomes a naturalized citizen. However, Rocio has confused several vital requirements and necessary steps needed to renew her PEP and become a naturalized citizen. According to Migration Colombia, PEP holders must apply for renewal for the 2021 program before the PEP expires (2020). Moreover, if her PEP expires and Rocio reenters the country, she will not qualify for different PEPs. According to Colombia’s immigration authorities, immigrants can only apply for one PEP program (Migración Colombia 2020).

Moreover, to acquire citizenship, immigrants without a Colombian parent or child need to first access legal permanent residency through the Residency Visa. However, Rocio knew nothing about the Migrant or Residency Visas and planned to apply for citizenship with her PEP, which would disqualify her automatically. Overall, knowing the PEP provided liminal legality did not shake Rocio’s sense of security. However, Rocio is at risk of becoming undocumented because of her misinformation about renewing her PEP and securing citizenship.

A few immigrants were highly informed about Colombian immigration legal residency and citizenship procedures and wanted to stay in Colombia legally, but they could not meet the Migrant or Residency Visas requirements. For them, liminal legality was their only option. For example, Mariana Gutierrez was a pharmacist in Venezuelan and enjoyed a comfortable socioeconomic lifestyle until the hyperinflation evaporated her salary. Worried about her children’s future, Mariana decided to immigrate to Colombia. Since she could not afford Venezuelan passports, she paid the bus driver extra to cross into Colombia without going through the official border checkpoints.

In 2018, Mariana and her children had been undocumented for a month in Cúcuta, Colombia, when she heard from other Venezuelans that the Colombian government had issued a census to register all undocumented Venezuelans who had an identification card. Though Mariana was not sure what the census would accomplish, she decided to participate because “everyone was talking about the census, and I thought, I should sign up; it sounds important. Thank God I did.” Mariana signed up mainly because it seemed important. Later, she learned that she and her children could get the RAMV-PEP due to her participation in the census.

When asked whether she felt supported and welcomed by the Colombian government, Mariana responded, “Yes, because I got that PEP permit even though I did not have a passport and applying for the PEP is easy. Then, they decided to renew the RAMV-PEP, and that was also very easy to do.” The ease of acquiring and renewing the PEP fosters a sense of security. Mariana feels gratitude towards and protected by the Colombian government.

This sense of gratitude obfuscates the limitations of the PEP. Mariana wants to remain in Colombia; she understands the process to become a permanent legal resident and naturalized citizen. Nevertheless, Mariana’s research has left her with a bitter realization that she does not have a clear path to more durable legality. During our interview, Mariana explained:

The PEP helps you get a job, but it does not help you acquire citizenship. … I have been researching the Colombian migration policies online. … I want to become a naturalized Colombian citizen, but it costs 1 million Colombian pesos [from US$250–300] to get the Migrant Visa. That is too much money.

The high cost of acquiring the Migrant Visa (US$250), the Residency Visa, and the fees associated with the naturalization application are significant deterrents. While informed, Mariana and a few others feel that the PEP’s liminal legality is their only tangible option. Thus, if the government decides to stop renewing PEPs or the new ETPV program, migrants who hope to stay in Colombia and know how to get on the path to legal permanent residency would likely end up undocumented because they cannot meet the high requirements of the Migrant and Residency Visas.

Stuck in Illegality

Broadly, most undocumented immigrants did not have any path to legal residency and felt stuck in illegality. Colombian immigration officials require Venezuelans to present a passport to enter through official legal channels and access most PEPs as well as the Migrant Visa. However, it is challenging for most Venezuelans to access a passport because passports are expensive, and SAIME (the agency that administers them in Venezuelan) often runs out of ink and paper; also, it takes a long time to get them processed. Most undocumented interviewees entered without authorization because they did not have passports or could not provide the Colombian border control officials additional documents requested to enter, such as round-trip travel tickets.

A few respondents obtained Colombia’s Border Mobility Cards to enter through official channels because they did not have a passport, and the cards are free. However, a legal entry with these cards disqualifies them from legal residency programs. Most undocumented respondents did not know about or qualify for the 2018 RAMV-PEP or the 2020 PEP-FF programs in Colombia, which were created to legalize undocumented Venezuelans. Thus, most interviewees remained undocumented because they experience the Colombian legalization programs as inaccessible.

For example, when Janet Rosales finished her high school education, she decided to emigrate to Columbia to reunite with her parents who had previously emigrated and because she could not find work to sustain herself in Venezuela. Since she could not afford a passport to enter legally, she has been undocumented in Colombia for five years. Janet could have gotten liminal legality through the regularization program RAMV-PEP, but she was unaware of its existence. Moreover, Janet lost her Venezuelan identification card; without it, she cannot apply for the PEP-FF or any other visa category. Further, Janet’s undocumented status made her vulnerable to ongoing exploitation by employers who refused to pay her the agreed wages and regularly fired her without notice. At the time of the interview, she was begging for money at a street corner. Janet explained, “I have tried to advocate for myself and legal residency, and it does not change anything because I am undocumented.” Janet’s attempts to claim her wages and find a way to legal residency have failed. In the process, she has come to experience legality in Colombia as unreachable and exclusionary.

Some undocumented interviewees had passports but entered without authorization because they did not have the resources to pay for additional requirements needed to cross the border regularly. For example, Carla Rodriguez emigrated with her sick father when she finished high school at only 17 years old. The devaluation of the Venezuelan bolívar had evaporated the family’s purchasing power. Because Carla was underage, the Colombian border control agents asked her to prove that her mother had authorized her to exit Venezuela. She did not have money to return to Caracas to get the permit, so Carla decided to pay smugglers 20,000 Colombian pesos to help her cross through a guerrilla-controlled territory. She used the few dollars she had left to travel to Bogotá with her father. Since moving to the capital, Carla has been unable to access legal residency. She explained:

I am scared of being deported. … It would be unjust because I came here to work. … My sister tells me that I can send my passport to somebody at the border checkpoint who will stamp it. She will pay half and I will pay the other half of the 200,000 Colombian pesos [about US$58] they charge. This is not legal, but I can’t afford to go there myself. … Though, I fear losing my passport and money.

Carla fears getting deported and has been unable to save enough money working informally at a bakery to travel six days (without any income) to Cúcuta and re-enter the country to get her passport stamped. She earns 820,000 Colombian pesos [US$236] per month, which is below the poverty line (DANE 2019). As Carla explained, her only feasible option is to pay a border patrol agent 200,000 Colombian pesos to stamp her passport. She can only afford to pay half of this fee, but Carla is hesitant to use this scheme because she will have to mail her passport and does not entirely trust that she will get it back. If she loses her passport, Carla cannot return to Venezuela and pay approximately US$300 or more to get a new one.

Moreover, Carla does not have a formal work contract and would have to find one to qualify for the Ministry of Labor’s PEP-FF. Broadly, Carla’s undocumented condition has forced her to work a low paying job at a bakery that does not allow her to cover the cost of getting her passport stamp through formal, safer channels. The limitations of her undocumented situation further derail Carlo into illegality.

Finally, some undocumented immigrants who entered legally with Border Mobility Cards did not know these cards disqualify them from the PEPs and Migrant Visa categories, which require proof of entry with a passport. These cards only help people who live along the Colombia-Venezuela border to transit freely. For example, Elvira Perez decided to emigrate when she finished high school because her family struggled to survive with her mother’s salary as a janitor. She lived near the border around Cúcuta, Colombia, and decided to get the Border Mobility Card online because it was free, and she could not afford a passport. During our interview, Elvira explained why it was so hard to access legal residency:

I entered with my Border Mobility Card because it is tough to get a passport. You must pay with dollars, the procedure is long and complicated, and it takes a long time to get it. … The Border Mobility Card permits you to enter Colombia legally for as long as you indicate. You can apply online via Migration Colombia. … I would like to get a PEP. However, when I have gone to Migration, they have told me to wait … [and] to keep checking for updates online. … So, I am waiting for a new measure. … I am also trying to figure out how to get a passport because it will be easier to get PEP with a passport; I would be more legal here.

Since Elvira immigrated after the RAMV program ended (which legalized undocumented Venezuelans), she struggles to find any job without legal residency. Thus, she does not qualify for the PEP-FF, which requires a formal work contract. Elvira plans to get a passport. Without more stable employment, she will have difficulties saving the money needed to return to Venezuela, pay for a passport, and re-enter legally. Despite her self-advocacy, the legal entry with a passport requirement and economic repercussions of being undocumented obstruct Elvira’s and other undocumented Venezuelans’ legalization options.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

I argue that Colombia’s pro-immigrant political discourse, weak immigration enforcement, and straightforward applications conceal the fragility and illegality production of the liminal legal programs. Most Venezuelan liminal legality recipients trust that the Colombian government will continue protecting them. Despite having the resources and knowledge to navigate legal systems, they do not feel a sense of urgency to find more durable legality. Nonetheless, the Colombian migration authorities use their executive discretion to change procedures and patch new legalization programs. Thus, most Venezuelans with liminal legality remain at risk of illegality because they have outdated, inaccurate information about how to maintain their PEPs or get on a path to legal permanent residency. The few PEP recipients who know how to acquire legal permanent residency cannot meet these visas’ high fees and requirements, which indicates the visa categories with pathways to citizenship remain inaccessible to many.

Moreover, although Colombian immigration authorities designed the liminal legality programs with few requirements and easy procedures (Palma-Guitérrez 2021), the most vulnerable Venezuelan immigrants are derailed into illegality. Undocumented Venezuelans tended to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds than the PEP holders and did not have the resources to meet the legal entry with a passport requisite of most PEPs and other legal residency categories. Thus, undocumented Venezuelans experience Colombia’s governmental welcome with a sense of hopelessness; most felt stuck in illegality.

These findings expand our understanding of how immigrants experience liminal legality in more inclusive governmental contexts. In more punitive contexts towards immigrants, recipients of liminal legality are aware of their status’ fragility and remain fearful of becoming undocumented or getting deported (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015; Hamilton et al., 2020; Menjívar, Agadjanian, and Oh 2020). Thus, when undocumented immigrants in antagonistic contexts experience some political or legal inclusion, they develop a “with the law” legal consciousness that prompts them to find ways to expand their legalization opportunities (Abrego 2011, 2018; Solórzano 2021). Only marginalized people who distrust the law avoid making such claims (Ewick and Silbey 1998; Hernández 2010; Abrego 2011, 2018; Solórzano 2021). While undocumented Venezuelans in Colombia followed these expected trajectories, surprisingly, liminal legality recipients did not. The governmental welcome fosters a different legal consciousness among liminal legality recipients. Migrants with liminal legality felt welcomed, legally included, and protected by the Colombian state, even when their tenuous legal status exposes them to similar vulnerabilities as those awarded to migrants in less receptive legal contexts.

Moreover, this study shows that liminal legality initial application’s requirements produce illegality. Existing illegality studies focus on how legalization programs and restrictive visa categories that provide pathways to citizenship exclude categories of migrants (De Genova 2004; Alfonso 2013; Menjívar and Kanstroom 2013). Liminal legality research focuses on the threat of illegality during status renewals (Menjívar 2006; Chacon 2015) but not during the initial application process. This study adds that access to liminal legality programs is stratified and produces illegality among the most disadvantaged members of the targeted population.

These findings have important implications for the ongoing incorporation of Venezuelans and other migrant populations. The recent Colombian ETPV (2021) program retains the liminality and illegality production mechanisms of the PEPs because it does not provide a pathway to citizenship, is not a law, and has legal entry requirements and limited eligibility timeframes (Migración Colombia 2021; see Appendix A). Many other Latin American governments, including other top destinations for Venezuelans (i.e., Ecuador and Peru), also use executive discretion to create temporary legalization programs (Acosta et al., 2019; Gandini et al., 2019; Selee et al., 2019) and pro-immigrant political discourse (Acosta and Freier 2015). Nonetheless, these other studies do not analyze how these contexts affect migrants’ legal consciousness or navigation of their legal status acquisition process. Thus, scholars can use this study’s conceptual connections between macro contexts, liminal legality, illegality, and migrants’ legal consciousness to explain dynamics in countries throughout Latin America. Moreover, the Colombian governmentvii and other countries, have closed their borders to contain the COVID-19 pandemic and are forcing migrants to enter undocumented. As this study shows, migrants without proof of legal entry struggle to access legalization opportunities. Thus, scholars are encouraged to examine how COVID-19 prevention measures undermine migrants’ access to legal residency worldwide.

Finally, the present study has several policy implications. Immigrant advocates can provide Venezuelans with legal aid and opportunities in the formal labor market to combat misinformation and expand access to visa categories with pathways to citizenship. Officials who seek to end illegality need to remove strenuous requirements to legal permanent residency, such as fees and legal entry requirements with a passport. Finally, policymakers are encouraged to create ongoing legalization programs that provide a path to citizenship through laws that are not vulnerable to political shifts.

Acknowledgements:

The author wishes to thank Felipe Corwhurst-Pons, Jennifer Cook, Estefanía Castañeda Pérez, Amy Zhou, Hajar Yazdiha, Eli Wilson, Niina Vuolajärvi, Vernetta Williams, Janeth Cabides, and Maria Camila Baquero for their insights and support in the development of this study and manuscript. All errors are mine.

Funding:

This work is supported by the MADRES Center for Environmental Health Disparities, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [#P50MD015705].

Biographical note

Dr. Deisy Del Real is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Southern California. Her research broadly examines the social construction of legal immigration systems and how legal immigration contexts, which range from enforcement- to rights-focused, affect immigrants’ lives. Her research projects have received support from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Health, among several other organizations.

Appendix A. Colombia’s Administrative Legalization Programs for Venezuelan Migrants, 2017–2021

| Legalization Programs | Requirements | Timeframes to Apply for Legal Residency |

|---|---|---|

|

1. PEP Resolutions 5797 (7.25.17) and 1272 (7.28.18) Renewal 1: Resolution 2634 (05.28.2019) Renewal 2: Resolution 2185 (08.28.2020) |

Must be in Colombia as of July 28, 2017 Venezuelan national Entered Colombia with a stamped passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia |

Initial application: August 3, 2017, to October 31, 2017 Renewal 1: June 4, 2019, to October 30, 3019 Renewal 2: September 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020 |

|

2. PEP

Resolutions 0740 (2.5.2018) and 0361 (2.6.2018) Renewal 1: Resolution 0740 (02.05.2018) Renewal 2: Resolution 2185 (08.28.2020) |

Must be in Colombia as of February 2, 2018 Venezuelan national Entered Colombia with a stamped passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia |

Initial application: February 7, 2018, to June 7, 2018 Renewal 1: December 23, 2019, to June 6, 2020 Renewal 2: September 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020 |

|

3. RAMV-PEP

Decree 1288 (7.25.2018) and Resolution 6370 (08.01.2018) Renewal: Resolution 1667 (07.02.2020) |

Step 1: RAMV census Requirements: Registered from April 6, 2018, to June 8, 2018 Venezuelan national Undocumented Venezuelan identification card or passport Step 2: PEP Requirements: Must be in Colombia as of August 2, 2018 Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia |

Initial application: August 2, 2018, to December 2, 2018 Renewal 1: July 4, 2020, to one day before RAMV-PEP ends |

|

4. PEP

Resolutions 10677 (12.18.2018) and 3317 (12.18.2018) |

Be in Colombia as of December 17, 2018 Venezuelan national Entered Colombia with a stamped passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia |

Initial application: December 27, 2018, to April 27, 2019 |

|

5. PEP-FF

Decree 117 (1.28.2020) |

Venezuelan national Undocumented Have a Venezuelan identification card or passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia Adult with formal job contract |

Initial application: February 3, 2020, to present Liminal legal status ends at end of labor contract |

|

6. PEP Resolutions 0240 (1.23.2020) and 0238 (1.29.2020) |

Be in Colombia as of November 29, 2019 Venezuelan national Entered Colombia with a stamped passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia |

Initial application: January 29, 2020, to May 29, 2020 |

|

7. PEP Resolutions 2502 (09.23.2020) and 2359 (10.06.2020) |

Be in Colombia as of August 31, 2020 Venezuelan national Entered Colombia with a stamped passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders Lives in Colombia |

Initial application: October 15, 2020, to February 15, 2021 |

|

8. ETPV Temporary Protection Status for Venezuelan Migrants Decree 216 (3.2.2021) and Resolution 0971 (4.28.2021) |

Venezuelan national Have a Venezuelan identification card or passport Clean criminal record No existing deportation or expulsion orders No ongoing administrative immigration investigations Does not have refugee status in Colombia or any other country and is not in the process of acquiring one Lives in Colombia Register for the Unique Register of Venezuelan Migrants (Registro Único de Migrantes Venezolanos, RUMV) and update their RUMV information every year or sooner if any information changes |

PEP recipients who sign up for the RUMV between May 5, 2021, and May 28, 2022 Undocumented Venezuelans must prove they were in Colombia before January 31, 2021, with a Colombian state-issued document and sign up for the RUMV between May 5, 2021, and May 28, 2022 Venezuelans who enter Colombia through official border checkpoints with passports between May 29, 2021, and May 28, 2023, and who sign up for the RUMV between May 28, 2021, and November 24, 2023 |

Source: Author’s compilation.

Footnotes

University of Southern California IRB Approval #: UP-20-00461

Declaration of Interests Statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Although not focusing on legal consciousness, see Goldring and Landolt (2021) for more examples.

Article (1)(A)(2).

Colombian Constitutional Court, Sentence C-256 (2016).

See Migración Colombia (2020) and Migración Colombia Resolution 0971 (Article 20).

They must prove with documents issued by the Colombian state, though the Colombian Border Mobility Card, which many undocumented respondents in this study have, does not count (Article 60 of Migración Colombia’s Resolution 0971).

Most interviewees applied for the PEPs independently or with limited guidance from immigration authorities, relatives, and friends, without help from non-governmental organizations.

Decree N. 593.

Data availability statement:

The in-depth interviews are part of an ongoing project and are not publically available.

REFERENCES

- Abrego Leisy J. 2011. “Legal Consciousness of Undocumented Latinos: Fear and Stigma as Barriers to Claims-Making for First-and 1.5-Generation Immigrants.” Law & Society Review 45(2):337–370. [Google Scholar]

- Abrego Leisy J. 2018. “Renewed Optimism and Spatial Mobility: Legal Consciousness of Latino Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Recipients and their Families in Los Angeles.” Ethnicities: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abrego Leisy J, and Lakhani Sarah M.. 2015. “Incomplete Inclusion: Legal Violence and Immigrants in Liminal Legal Statuses.” Law and Policy 37(4):265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta Diego, and Freier Luisa Feline. 2015. “Turning the Immigration Policy Paradox Upside Down? Populist Liberalism and Discursive Gaps in South America.” International Migration Review 49(3):659–696. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta Diego, Blouin Cécile, and Freier Luisa Feline. 2019. “La emigración venezolana: respuestas latinoamericanas.” Fundación Carolina. Retrieved August 5, 2020 (https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/DT_FC_03.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga Sáez Felipe, and de Andrade Angelo Flórez. 2020. Dimensiones de la migración en Colombia. Bogotá, D.C.: Ediciones USTA. [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga Saéz Felipe, Sicard Nadia García, and de Andrade Angelo Flórez. 2020. “La integración de los venezolanos en Colombia: discurso de líderes inmigrantes en Bogotá y Cúcuta.” Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 94:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso Adriana. 2013. “La experiencia de los países Suramericanos en materia de regularización migratoria.” International Organization for Migration. Retrieved August 20, 2021 (https://repositoryoim.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11788/1405/ROBUE-OIM_011.pdf?sequence=1). [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Raquel Flores. 2007. “Evolucion historica de las migraciones en Venezuela. Breve Recuento.” Aldea Mundo 22:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Baban Feyzi, Ilcan Suzan, and Rygiel Kim. 2017. “Syrian refugees in Turkey: pathways to precarity, differential inclusion, and negotiated citizenship rights.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43(1):41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Basok Tanya and Rojas Wiesner Martha L.. 2018. “Precarious legality: regularizing Central American migrants in Mexico.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41(7):1274–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Cancillería de Colombia. 2020. “Determinación de la Condición de Refugiado.” Bogotá D.C.: Cancillería de Colombia. Retrieved January 8, 2021 (https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/international/politics/refugee). [Google Scholar]

- Castro Alexandra Franco. 2020. “Régimen de Extranjería en Colombia.” Pp. 197–230 in Dimensiones de la migración en Colombia, edited by Sáez F. Aliaga and de Andrade A. Flórez. Bogotá D.C.: Ediciones USTA. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Alexandra Franco, and Sánchez Irit Milkes. 2018. “Potestad Sancionatoria y Politica Migratoria Colombiana.” Pp. 855–892 in El poder sancionador de la administración pública: discusión, expansión y construcción, edited by Plata A. Montaña and Córdoba J.I. Rincón. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Celbuko Kara. 2014. “Documented Undocumented and Liminally Legal Status During the Transition to Adulthood for 1 5 Generation Brazilian Immigrants.” The Sociological Quarterly 55:143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chacon Jennifer M. 2015. “Producing Liminal Legality.” Denver University Law Review 92(4):709–768. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-González Diego, and Echeverría-Estrada Carlos. 2020. “Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees in Latin America and the Caribbean a Regional Profile.” Washington D.C.: Fact Sheet in Migration Policy Institute and International Organization for Migration. [Google Scholar]

- Ciurlo Alessandra. 2015. “Nueva política migratoria colombiana: El actual enfoque de inmigración y emigración.” Revista Internacional de Cooperacióm y Desarrollo 2(2):205–242. [Google Scholar]

- DANE. 2019. “Pobreza monetaria por departamentos en Colombia.” July 12, 2019 DANE Boletín Técnico Pobreza Monitoria Departamental del; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Genova Nicholas. 2004. “The Legal Production of Mexican/Migrant “Illegality.”‘ Latino Studies (2):160–185. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2018. “European Parliament resolution on the migration crisis and humanitarian situation in Venezuela and at its terrestrial borders with Colombia and Brazil.” Belgium: European Parliament. Retrieved December 2, 2020 (http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+MOTION+P8-RC-2018-0315+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN). [Google Scholar]

- Ewick Patricia, and Silbey Susan S.. 1998. The Common Place of the Law: Stories from Everyday Life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gandini, Luciana, Fernando Lozano Ascencio, and Victoria Prieto. Crisis y migración de población venezolana. Entre la desprotección y la seguridad jurídica en Latinoamérica. Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Global Detention Project. 2020. “Detention Centers.” Global Detention Project. Retrieved February 3, 2021 (https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/detention-centres/map-view). [Google Scholar]

- Goldring Luin, and Landolt Patricia. 2021. “From illegalised migrant toward permanent resident: assembling precarious legal status trajectories and differential inclusion in Canada.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1866978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Eric R., Patler Caitlin, and Savinar Robin. 2020. “Transition into Liminal Legality: DACA’s Mixed Impacts on Education and Employment among Young Adult Immigrants in California.” Social Problems doi: 10.1093/socpro/spaa016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Diana. 2010. “I’m gonna call my lawyer”: shifting legal consciousness at the intersection of inequality.” Studies in Law, Politics, and Society 51:95–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kubal Agnieszka. 2013. “Conceptualizing Semi-Legality in Migration Research.” Law & Society Review 47(3):555–587. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia. 2006. “Liminal Legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ Lives in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 111(4):999–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia, and Kanstroom Daniel. 2013. Constructing Immigrant “Illegality.” Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar Cecilia, Agadjanian Victor, and Oh Byeongdon. 2020. “The Contradictions of Liminal Legality: Economic Attainment and Civic Engagement of Central American Immigrants on Temporary Protected Status.” Social Problems doi: 10.1093/socpro/spaa052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migración Colombia. 2020. “PEP.” Bogotá, D.C.: Migración Colombia. Retrieved September 22, 2020 (https://www.migracioncolombia.gov.co/venezuela/pep). [Google Scholar]

- Migración Colombia. 2021. “ABC Estatuto Temporal de Protección - Migrantes Venezolanos.” Bogotá, D.C.: Migración Colombia. Retrieved February 23, 2021 (https://www.migracioncolombia.gov.co/infografias/abc-estatuto-temporal-de-proteccion-migrantes-venezolanos). [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Gutiérrez Mauricio. 2021. “The Politics of Generosity. Colombian Official Discourse towards Migration from Venezuela, 2015–2018.” Colombia Internacional 106:29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Presidencia. 2018. ‘Palabras del Presidente Iván Duque en la reunión de alto nivel ‘Refugiados y migrantes de Venezuela: Hacia una respuesta regional.”‘ Presidencia Colombiana. [Google Scholar]

- R4V. 2021. “Response for Venezuelans.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and International Organisation for Migration, Retrieved October 30, 2021 (https://r4v.info/es/situations/platform). [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo Jair Pineda, Juliana Jaramillo Jaramillo, and Torres Manuela. 2018. Venezuelans in Colombia: understanding the implications of the migrants crisis in Maicao (La Guajira). Vienna,VA: SARAYA International. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval Carlos. 2014. “Public Social Science at Work: Contesting Hostility Towards Nicaraguan Migrants in Costa Rica,” Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace 9:351–363. [Google Scholar]

- Selee Andrew, Bolter Jessica, Muñoz-Pogossian Betilde, and Hazán Miryam. 2019. “Creativity amid Crisis: Legal pathways for Venezuelan Migrants in Latin America.” Migration Policy Institute and Organization of American States, January 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano Lizette G. 2021. “We are not the people they think we are: First-generation undocumented immigrant belonging and legal consciousness in the wake of deferred action for parents of Americans.” Ethnicities doi: 10.1177/14687968211041805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2018. “Human Rights Violations in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: a Downward Spiral with No End in Sight,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Retrieved January 15, 2021, Available at (https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/VE/VenezuelaReport2018_EN.pdf). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The in-depth interviews are part of an ongoing project and are not publically available.