Abstract

Background:

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) plays an important role in neurological recovery after cardiac arrest (CA) resuscitation. However, variation of CBF recovery in distinct brain regions and its correlation with neurologic recovery after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) have not been characterized. This study aimed to investigate the characteristics of regional cerebral reperfusion following resuscitation in predicting neurological recovery.

Methods:

Twelve adult male Wistar rats were studied, 10 resuscitated from 7-min asphyxial CA and 2 uninjured rats as healthy control (HC). Dynamic changes in CBF in cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, brainstem and cerebellum were assessed by pseudo-continuous arterial spin-labeling magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), starting at 60-min after ROSC to 156-min (or time to spontaneous arousal). A blinded examiner evaluated outcomes using neurologic deficit scale (NDS) at 24-h post-ROSC. Correlations between rCBF and neurological recovery were undertaken.

Results:

All post-CA animals were found to be nonresponsive during the 60- to 156-min post-ROSC, with reductions in rCBF by 24 to 42% versus HC. Analyses of rCBF during the post-ROSC time window from 60- to 156-min showed the rCBF recovery of hippocampus and thalamus were positively associated with better neurological outcomes (rs=0.82, p=0.004 and rs=0.73, p<0.001, respectively). During 96 minutes before arousal, thalamic and cortical rCBF exhibited positive correlations with neurological recovery (rs=0.80, p<0.001 and rs=0.65, p<0.001, respectively); for predicting a favorable neurological outcome, the thalamic rCBF threshold was above 50.84 ml/100g/min (34% of HC) (AUC=0.96), while the cortical rCBF threshold was above 60.43 ml/100g/min (38% of HC) (AUC=0.88).

Conclusions:

Early MRI analyses showed early rCBF recovery in thalamus, hippocampus and cortex post-ROSC was positively correlated with neurological outcomes at 24-h. Our findings suggest new translational insights into the regional reperfusion and the time-window that may be critical in neurological recovery and warrant further validation.

Keywords: heart arrest, resuscitation, cerebrovascular circulation, brain ischemia, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Cardiac arrest (CA) affects more than 550,000 people each year and leads to considerably poor survival rates (10.4 to 30.4%) in the United States1,2. Only 8.4% out-of-hospital CA patients survive with good functional status at hospital discharge1. Global cerebral ischemia from CA is the crucial determinant functional outcome and neurological disability3. During CA and following the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), the disturbances of cerebral blood flow (CBF) are featured as the “no-reflow” phenomenon and prolonged hypoperfusion phase4. Highly metabolically active brain regions, such as cerebral cortex and hippocampus, are vulnerable to the brain injury due to a lower tolerance to prolonged durations of ischemic damage3,4. Selective neuronal damage was observed in the thalamus in the first hour post-CA and also in the cortex, hippocampus and striatum during the early 3 hours5. However, little is known regarding dynamic changes of regional CBF (rCBF) recovery and its timing during the post-CA hypoperfusion phase and its impact on the neurological outcome.

Asphyxial CA (ACA) rodent model has been validated in prior preclinical research6,7. Previously, we utilized laser speckle contrast imaging to report that therapeutic hypothermia promoted restoration of CBF of post-ACA rats to the baseline level in the very early stage after resuscitation, and the benefit of the restored blood flow was corroborated by improvements in brain electrical activity and neurological recovery8. Arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging (ASL-MRI) has been widely employed for assessing CBF as the technique provides useful information on rCBF9. Differential patterns of rCBF changes during hyperperfusion were confirmed in the ACA rodent model10. Still, the observed phenomenon of rCBF dynamics during the hypoperfusion phase following the hyperemia after resuscitation needs further investigation. The regional distribution and perfusion dynamics post-cardiac arrest and the occurrence of hypoperfusion and hyperemia during reperfusion are important to study as they are believed to be associated with brain injury and subsequent outcome11.

We recently demonstrated that global CBF, oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) had inclination to rise steadily during 1-3 hours post-ROSC, and a greater increase in cerebral oxygen consumption was linked to a better neurological outcome12. Here, we hypothesized that CBF dynamics vary among different key brain regions during the early stage of hypoperfusion after CA and this differential in rCBF recovery and the timing of reperfusion in different regions would be associated with differential neurological outcomes.

Methods

Animals

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute Animal Care and Use Committee. All procedures involved were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of animals and reported based on the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments) guidelines (https://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arrive-guidelines). The ACA rat model studied in this study has been validated previously8,13,14.

We have previously shown that 7 minute-arrest represents a duration where brain injury is significant to show alterations in physiology without causing a profound injury such that the majority of animals are still able to survive to assess neurological outcome8. As a translational study, the duration of 7 minutes ACA results in an average degree of brain injury in this pre-clinical model that will reflect a representative brain injury in an average human cardiac arrest.

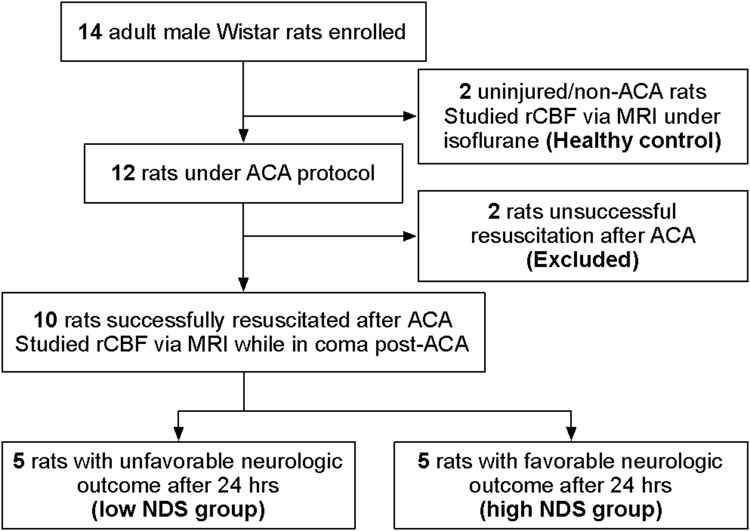

A total of 14 adult Wistar male adult rats (400-450 g; 11-12 weeks old; Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were studied. Two rats were used as uninjured healthy control (HC) under isoflurane anesthesia used for comparison. Twelve rats were subjected to 7-min CA protocol, 2 rats were not resuscitated successfully and were excluded subsequently. Ten rats completed the experimental protocol and formed the study cohort (see Figure 1). Our prior study showed a minimum of 5 rats (male) per group was needed to detect the difference in brain injury by CA duration15. This cohort size is adequate to account for the physiologic and pathologic variables in a study of thalamic somatosensory vulnerability in our model16. In a recent MRI study, we showed that the sample size of ten had sufficient statistical power to observe physiological alterations (OEF, CBF, or CMRO2) following resuscitation12.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study design. ACA, asphyxial cardiac arrest; NDS, neurologic deficit scale; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow.

ACA animal model

All animals were housed in a quiet environment with free access to food and water and 12-hour day/night cycles. Before the start of all experiments, animals were given one week for environmental adaptation.

The animals were subjected to 7-min asphyxia-induced CA. Our protocol has been previously described in details8,13,14. The rats were endotracheally intubated with 14 G catheters (Terumo SurFlash I.V. Catheter) and mechanically ventilated with 2% isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) in 50% oxygen and 50% nitrogen gas with a breath rate at 35 per minute using a small animal ventilator (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). The femoral artery and vein on the left side were cannulated with polyethylene tubing catheters (PE 50; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for recording the arterial pressure and medication administration. After the cannulation, a 5-min anesthesia washout period was given, starting with 2-min 100% oxygen without isoflurane and then 3-min 20% oxygen mixed with 80% nitrogen (room air). At the end of 2-min pure oxygen, Vecuronium bromide (2 mg/kg, I.V.; Abbott Labs, North Chicago, IL) was administered to induce muscle paralysis. Following the 5-min washout period, global asphyxia was induced by disconnecting the ventilator and clamping the tracheal tube for 7 minutes. CA was interpreted by pulselessness with mean arterial pressure < 10 mmHg with non-pulsatile-pressure wave. After the 7-min asphyxia period, the procedure of cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started by unclamping the tracheal tube, restarting mechanical ventilation with 100% oxygen, administering epinephrine (5 μg/kg, I.V; PAR Sterile Products, Rochester, MI) and NaHCO3 (1 mmol/kg, I.V.; Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) and applying sternal chest compressions with two fingers (about 200 compressions/min) till ROSC defined by mean arterial pressure > 50 mmHg. After successful resuscitation, mean arterial pressure was monitored for 15 minutes before all catheters were removed. Following that, the animals were extubated and allowed to recover spontaneously.

MRI imaging and analyses

After extubation, the animals were transported to the MRI suite and positioned on a temperature-controlled animal bed with bite bars and ear pins for immobilization. Then, the animal bed was placed in the center of the MRI magnet. Considering the continuous comatose state of post CA rats, anesthesia was not adopted during the MRI session while respiration rate was monitored throughout the scanning protocol and normothermia was maintained. This was also done to minimize pharmacologic effects on the post-CA recovery process. The MRI sessions were repeated in another two male Wistar rats without CA procedures to provide reference values of healthy control. For those non-CA rats, 2% isoflurane was used throughout the MRI scanning for anesthetic maintenance.

Detailed MRI set-up was elucidated in our previously published paper12. Briefly, MRI scanning was performed using an 11.7 Tesla (T) Bruker Biospec system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with a horizontal bore and actively shielded pulsed field gradients with a maximum intensity at 0.74 T/m. A 72-mm quadrature volume resonator was used as transmitter with a four-element (2×2) phased-array coil as the receiver. To improve the robustness of ASL17 against residual magnetic-field inhomogeneity at the high field (11.7T), a two-scan pCASL scheme18,19 was employed. The experimental parameters were: TR/TE = 3000/13.9 ms, FOV = 30×30 mm2, matrix size = 96×96, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, labeling-pulse width = 0.4 ms, inter-labeling-pulse delay = 0.8 ms, mean B1 amplitude = 2.5 μT, labeling duration = 2000 ms, post-labeling delay = 400 ms, receiver bandwidth = 300 kHz, number of average = 25, partial Fourier acquisition factor = 0.7, slice number = 15, and scan duration = 2.5 min. Due to the difficulty in estimating inversion efficiency of the labeling module, we applied a normalization method20 in the pCASL data processing to quantify the absolute-value regional perfusion, i.e., the global CBF values measured with phase-contrast MRI collected at each time point over the major feeding arteries were used for normalization. The phase-contrast MRI was performed with identical parameters as previously reported12. The pCASL images were obtained from 60-min after ROSC until the spontaneous arousal from a comatose state (156-min to 188-min post-ROSC) with a 16-min interval between two adjacent time points12. Regions detected for rCBF included cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum.

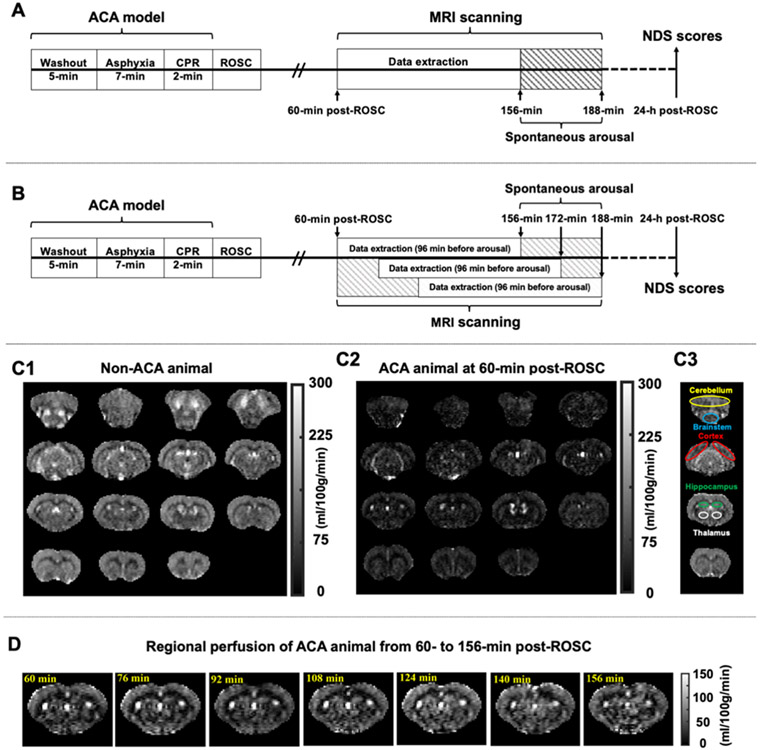

All MRI data were processed using custom-written MATLAB scripts (Math Works, Natick, MA) in a double-blinded fashion that personnel processing the data or performing the neurologic behavioral assessment had no access to results in the other session until they finished. The MRI session, as we described in our previous study, started around 25-min post-ROSC, following by another 35 minutes for adjusting the animal position, acquiring field map, shimming as well as anatomic scanning12. As a result, the dynamic MRI scanning began at 60-min after resuscitation. Each CA-subjected animal was allowed to wake up spontaneously, which meant that the total scanning time varied across rats. The ending point of scanning was chosen at 188-min post-ROSC or when the animal exhibited strong motions, whichever occurred first. In particular, 4 rats completed the scanning up to 156-min post-ROSC, 2 rats up to 172- min, and 4 rats up to 188-min. To study the rCBF alterations from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC, MRI data was extracted from all animals up to 156-min after resuscitation. The experimental protocol is exhibited in Figure 2A. At the same time, we believe that this variability in arousal recovery times has a significant biologic impact as far as brain injury is concerned. Hence, to study the rCBF changes before spontaneous arousal, MRI data was extracted based on different arousal times of CA rats with an equal time course of 96 minutes in total (see Figure 2B). Representative images of pCASL-MRI are shown as Figure 2C-D.

Figure 2.

Experimental protocols and representative rCBF images. A, Schematic diagram of experimental design for MRI data extraction from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC in ACA rats. B, Schematic diagram for MRI data extraction during 96 minutes before spontaneous arousal in ACA rats. C1-3, Representative rCBF maps, including C1 from non-ACA animals (as healthy control), C2 from ACA animals (at 60-min post-ROSC) showing a widespread reduction in CBF, and C3 shows reference locations of the five regions of interest, including cerebellum with yellow delineation, brainstem with blue delineation, cerebral cortex with red delineation, hippocampus with green delineation, and thalamus with white delineation. D, Representative dynamic images of regional perfusion in ACA animals from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC. ACA, asphyxial cardiac arrest; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; NDS, neurologic deficit scale; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Neurological evaluation

NDS has been extensively validated for correlation with neurological recovery observations in the subject after global cerebral ischemia in our model system7,8,15. The NDS scoring ranges from 0 to 80 (see Table 1) and was determined by an experienced observer at 24-h post-ROSC, who was not acknowledged by the details of MRI procedures. Median of NDS scores has been utilized to separate favorable and unfavorable neurological outcomes after CA insult12,21. For the final grouping in this study, we adopted the same method to divide post-CA rats into two groups (n=5 per group), namely low NDS group and high NDS group, for further analyses15.

Table 1.

Neurologic Deficit Scale for rats.

| A – Arousal (0 - 19) | |

| Alerting | Normal (10), stuporous (5), comatose (0) |

| Eye opening | Open spontaneously (3), open to pain (1), absent (1) |

| Spontaneous respiration | Normal (6), abnormal (3), absent (0) |

| B – Brainstem function (0 - 21) | |

| Olfaction | For each category: present (3), absent (0) |

| Vision | |

| Pupillary light reflex | |

| Corneal reflex | |

| Startle reflex | |

| Whisker stimulation | |

| Swallowing | |

| C – Motor assessment (0 - 6) | |

| Strength | Normal (3), weak movement (1), no movement (0) (Each side tested and scored separately) |

| D – Sensory assessment (0 - 6) | |

| Pain | Brisk withdrawal (3), weak movement (1), no movement (0) (Each side tested and scored separately) |

| E – Motor behavior (0 - 6) | |

| Gait coordinate | Normal (3), abnormal (1), absent (0) |

| Balance beam walking | Normal (3), abnormal (1), absent (0) |

| F – Behavior (0 - 12) | |

| Righting reflex | For each category: Normal (3), abnormal (1), absent (0) |

| Negative geotaxis | |

| Visual placing | |

| Turning alley | |

| G – Seizures (0 - 10) | |

| Seizures | No seizure (10), focal seizure (5), generalized seizure (0) |

| Normal condition = 80; Worst outcome = 0 | |

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by Graph Pad Prism 8.0 version (Graph Pad, San Diego, CA) and SPSS 26.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Independent-Samples T test or Mann-Whitney U test was utilized for the comparison between two groups. For rCBF temporal changes, repeated measures 1- or 2-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Bonferroni’s correction as the post hoc test. Spearman’s rank correlation was chosen to assess correlations between rCBF and neurological recovery. ROC curve combing concordance probability method22 was used to define the optimal cutoff value of rCBF. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. The statistical significance threshold was set at p<0.05.

Results

Ten animals were successfully resuscitated from ACA (asphyxial time to pulselessness: 258.70±8.61 sec; resuscitation time: 70.50±4.44 sec). Following the global cerebral ischemia, the animals showed post-CA neurological deficits at 24-h after ROSC with neurologic deficit scale (NDS) scores ranging from 0 to 78 (brain dead=0 and fully recovered=78) (median [interquartile range] 67 [59.75-74.75], n=10). Based on the median of NDS scores, the ten rats were divided equally into two groups (5 per group): low NDS group (NDS<67) and high NDS (NDS≥67) group. Differences between the two groups in body weight (low NDS vs. high NDS group: 423.40±10.37 g vs. 424.40±14.33 g, p=0.96), asphyxial time to pulselessness (244.80±9.44 sec vs. 272.60±12.17 sec, p=0.11), resuscitation time (64.0±6.20 sec vs. 77.0±5.39 sec, p=0.15) and the time to arousal from ROSC (median [interquartile range] 172 [172-188] min vs. 156 [156-188] min, p=0.50) were not statistically significant.

Regional CBF dynamics following resuscitation

MRI data from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC showed that rCBF dropped to 40% in cerebral cortex, 26% in hippocampus, 35% in thalamus, 24% in brainstem, and 42% in cerebellum compared to the control animals at the lowest level (Table 2). Figure 3A illustrates rCBF dynamics following CA-induced brain injury. The rCBF in the brainstem and the hippocampus increased significantly over time (p=0.029 and p<0.0001, respectively) and reached their peaks around 2-h after resuscitation. Although the thalamic rCBF showed a steady recovery, the recovery change was statistically non-significant in relation to time of recovery (p=0.215). The rCBF in the cerebellum exhibited a slightly decreasing, although not statistically significant, trend (p=0.410), and the rCBF in the cerebral cortex did not appear to be changing (p=0.968) during the same period. Moreover, comparing among rCBF in all areas studied, there was a significant overall difference from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC (p=0.033).

Table 2.

rCBF in rats subjected to global cerebral ischemia induced by asphyxial cardiac arrest.

| Regions | CBF from HC* |

CBF from ACA rats after ROSC (% of HC)† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 min | 76 min | 92 min | 108 min | 124 min | 140 min | 156 min | P (ANOVA) | ||

| Cortex | 159.40 | 63.78 ± 8.20 (40.01%)‡ |

69.29 ± 7.59 (43.47%) |

66.43 ± 6.47 (41.68%) |

71.30 ± 9.10 (44.73%) |

73.64 ± 13.64 (46.20%) |

67.34 ± 7.70 (42.24%) |

66.67 ± 9.07 (41.82%) |

0.968 |

| Hippocampus | 154.70 | 41.66 ± 5.55 (26.93%)‡ |

48.67 ± 5.52 (31.46%) |

56.51 ± 8.60 (36.53%) |

68.92 ± 6.25 (44.55%) |

81.68 ± 9.93 (52.80%) |

74.07 ± 6.57 (47.88%) |

71.61 ± 5.04 (46.29%) |

<0.0001 |

| Thalamus | 149.50 | 52.67 ± 6.38 (35.23%)‡ |

52.81 ± 5.64 (35.33%) |

52.73 ± 5.32 (35.27%) |

57.45 ± 5.78 (38.43%) |

60.19 ± 6.51 (40.26%) |

61.76 ± 7.51 (41.31%) |

66.07 ± 9.50 (44.19%) |

0.215 |

| Brainstem | 132.90 | 32.99 ± 10.08 (24.82%)‡ |

35.75 ± 9.22 (26.90%) |

40.38 ± 10.19 (30.38%) |

49.18 ± 10.51 (37.01%) |

48.94 ± 8.68 (36.83%) |

51.39 ± 10.71 (38.67%) |

42.19 ± 9.50 (31.74%) |

0.029 |

| Cerebellum | 153.40 | 78.13 ± 10.65 (50.93%) |

78.71 ± 7.83 (51.31%) |

76.08 ± 7.65 (49.60%) |

79.37 ± 9.40 (51.74%) |

82.98 ± 8.51 (54.10%) |

68.43 ± 8.20 (44.61%) |

64.83 ± 9.59 (42.26%)‡ |

0.410 |

| Regions | CBF from ACA rats before arousal† | ||||||||

| −96 min | −80 min | −64 min | −48 min | −32 min | −16 min | 0 min | P (ANOVA) | ||

| Cortex | 62.66 ± 5.10 | 62.45 ± 4.54 | 64.17 ± 5.60 | 74.45 ± 9.45 | 70.82 ± 13.99 | 61.32 ± 8.20 | 63.89 ± 10.47 | 0.727 | |

| Hippocampus | 54.69 ± 9.15 | 58.73 ± 7.71 | 73.11 ± 6.48 | 74.56 ± 9.37 | 67.91 ± 5.06 | 64.32 ± 5.73 | 71.61 ± 5.04 | 0.243 | |

| Thalamus | 52.23 ± 5.12 | 50.94 ± 4.88 | 61.08 ± 6.30 | 61.93 ± 9.16 | 58.54 ± 8.63 | 58.54 ± 8.63 | 58.74 ± 8.41 | 0.401 | |

| Brainstem | 38.11 ± 11.04 | 44.89 ± 11.56 | 44.91 ± 8.72 | 50.58 ± 8.34 | 47.18 ± 8.38 | 46.69 ± 11.34 | 37.78 ± 8.79 | 0.629 | |

| Cerebellum | 75.62 ± 7.47 | 78.77 ± 8.71 | 77.41 ± 7.14 | 74.48 ± 7.12 | 72.14 ± 10.49 | 63.87 ± 9.71 | 52.39 ± 8.01 | 0.122 | |

Data represents as mean (n=2) in unit ml/100g/min;

Data represents as mean ± SEM (n=10) in unit ml/100g/min;

The lowest rCBF during the whole period. ACA, asphyxial cardiac arrest; CBF, cerebral blood flow; HC, healthy control; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Figure 3.

rCBF dynamics and correlation between hippocampal rCBF and neurologic outcome. A1-5, rCBF dynamics from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC. Blue lines show rCBF values from non-ACA rats (healthy control). B, Scatter plot of the correlation between rate-of-change of rCBF in the hippocampus and 24-h NDS scores. Data represents as mean ± SEM. Comparisons among rCBF temporal changes performed with repeated measures 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; correlation between rate-of-change in hippocampal rCBF and NDS scores performed with Spearman’s rank correlation. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001. ACA, asphyxial cardiac arrest; CBF, cerebral blood flow; NDS, neurologic deficit scale; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Given the increasing rCBF in the brainstem and the hippocampus, we examined rate-of-change of rCBF in the two areas using a linear regression of CBF values from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC, as previously reported12. Results of Spearman’s correlation indicated that a significant positive association between NDS and the increasing rate of rCBF was found in the hippocampus (rs=0.817, p=0.004; Figure 3B) but not in the brainstem (rs=0.335, p=0.343).

When we compared the low NDS and high NDS groups, rCBF recovery appeared to be similar in all brain regions for both groups during 60- to 96-min after ROSC (Figure 4A). However, from 108 to 156 minutes post-ROSC, the rCBF in the high NDS (i.e. good outcome) group was remarkably increasing towards the HC level as compared to the low NDS (i.e. poor outcome) group. Notable of all regions was the rCBF in the thalamus where a 2-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the two groups (low NDS: 43.80±2.52 ml/100g/min vs. high NDS: 71.54±2.86 ml/100g/min, p=0.002) alongside an overall difference with time (p=0.004). In the hippocampus, however, there was a significant Time × Group interaction effect in the rCBF (p=0.042) but mainly due to a temporal change (p<0.0001). Spearman’s correlations were conducted between the thalamic rCBF and neurological outcomes (which were ranked as low NDS and high NDS). There were significant positive correlations between the thalamic rCBF and neurological recovery starting at 1.5-h post-ROSC (p<0.02) (see Table 3). Furthermore, the thalamic rCBF values of this entire period exhibited a strong overall correlation with NDS scores art 24 hours (rs=0.728, p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

rCBF dynamics in low and high NDS groups with ROC curve for thalamic rCBF. A1-5, Comparisons of rCBF between low and high NDS groups from 60- to 156-min after resuscitation in CA animals (n=5 per group). B, ROC curve for rCBF in the thalamus in the prediction of neurological outcome. Data represents as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between low and high NDS groups in rCBF performed with 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; ROC curve with concordance probability method used to determine the optimal cutoff value of rCBF in thalamus. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, **** p<0.0001. CA, cardiac arrest; CBF, cerebral blood flow; NDS, neurologic deficit scale; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Table 3.

Correlations between rCBF and 24-h NDS scores (ranked as low and high NDS).

| rCBF | After ROSC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 min | 76 min | 92 min | 108 min | 124 min | 140 min | 156 min | Overall | |

| Thalamus* | 0.522 | 0.522 | 0.731† | 0.870‡ | 0.801‡ | 0.731† | 0.870‡ | 0.728‡ |

| rCBF | Before arousal | |||||||

| −96 min | −80 min |

−64 min |

−48 min | −32 min | −16 min | 0 min | Overall | |

| Cortex* | 0.383 | 0.453 | 0.801‡ | 0.870‡ | 0.870‡ | 0.453 | 0.801‡ | 0.653‡ |

| Thalamus* | 0.661† | 0.870‡ | 0.731† | 0.870‡ | 0.870‡ | 0.661† | 0.870‡ | 0.802‡ |

| Cerebellum* | 0.454 | 0.454 | 0.524 | 0.733† | 0.873‡ | 0.105 | 0.105 | 0.473‡ |

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

p<0.05,

p<0.01. NDS, neurologic deficit scale; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

From the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve shown in Figure 4B, we found that the optimal cutoff value in differentiating good and poor outcomes to a thalamic rCBF is 50.84 ml/100g/min, and with this value, the sensitivity and the specificity were 91.4% and 88.6%, respectively (AUC=0.920, p<0.0001). This indicates that ACA-subjected animals achieved a better neurological outcome when the thalamic rCBF was above 50.84 ml/100g/min during 60- to 156-min post-ROSC.

Regional CBF dynamics before arousal

As arousal from coma or unresponsiveness is an important clinical marker of neurologic recovery23, we performed a detailed analysis on rCBF dynamics in relation to recovery of arousal. During the 96 minutes before spontaneous arousal, there were no significant temporal changes in rCBF of all regions (Table 2). We characterized rCBF recovery during the last 90 minutes prior to arousal. rCBF in these five regions appeared to be remarkably improved in high NDS groups in comparison with low NDS groups (Figure 5A). Particularly, the rCBF increased significantly in the high NDS group compared to low NDS group in the cerebral cortex (80.11±4.91 ml/100g/min vs. 51.25±2.39 ml/100g/min and p=0.014, or 50% vs. 32% of HC), in the thalamus (72.95±2.96 ml/100g/min vs. 40.67±1.69 ml/100g/min and p=0.0001, or 49% vs. 27% of HC), and in the cerebellum (82.39±4.08 ml/100g/min vs. 58.95±4.20 ml/100g/min and p=0.017, or 54% vs. 38% of HC) over the 1.5 hours before arousal. In the high NDS group, the rCBF is 1.8 times more than the low NDS group in the thalamus, 1.6 times more in the cortex, and 1.4 times more in the cerebellum. All the rCBF with high NDS scores were about 50% of normal rCBF at 1.5 hours prior to arousal.

Figure 5.

rCBF dynamic before arousal in low and high NDS groups and ROC curves for representative rCBF. A, Comparisons of rCBF between low and high NDS groups from (−96)- to 0-min before spontaneous arousal in CA animals (n=5 per group). B, ROC curves for rCBF, including cortex, thalamus, and cerebellum, in the prediction of neurological outcome. Data represents as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between low and high NDS groups in rCBF performed with 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; ROC curve with concordance probability method used to determine optimal cutoff values of rCBF in cortex, thalamus and cerebellum. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001. CA, cardiac arrest; CBF, cerebral blood flow; NDS, neurologic deficit scale; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow.

There were positive correlations between rCBF in the three regions and 24-h NDS scores. Results are summarized in Table 3. The thalamic rCBF was positively correlated with 24-h NDS during the entire time course and a strong correlation was confirmed by an overall analysis (rs=0.802, p<0.0001). Moderate correlations were found between neurological recovery and rCBF in the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex (rs=0.473 with p<0.0001 and rs=0.653 with p<0.0001, respectively).

ROC curves for rCBF in the cerebral cortex, the thalamus and the cerebellum, are illustrated in Figure 5B. As determined by concordance probability, optimal sensitivity and specificity were both 91.4% in the thalamus with a cutoff value at 50.84 ml/100g/min (34% of HC) (AUC=0.963, p<0.0001), both 82.9% in the cerebral cortex with a cutoff value at 60.43 ml/100g/min (38% of HC) (AUC=0.877, p<0.0001), and both 74.3% in the cerebellum with a cutoff value at 64.43 ml/100g/min (42% of HC) (AUC=0.773, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Our study shows that ACA resulted in a significant difference in rCBF recovery among key brain regions from 60- to 156-min post-ROSC. The recovery of thalamic rCBF had the strongest correlations with neurological outcome as well as arousal. The rCBF recovery in the cerebral cortex and specifically in the hippocampal area was also positively correlated with neurological recovery. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report focusing on rCBF reperfusion patterns assessed by pCASL-MRI during the first 1 to 2 hours post-ROSC in the thalamocortical regions in relation to neurological outcomes after CA. These observations present not only a regional area of reperfusion opportunity but also a temporal window to rescue critical care brain regions for improved functional recovery.

Global cerebral ischemia is a devastating consequence of CA leading to the brain injury. Following the immediate hyperemia after ROSC, the hypoperfusion phase starts at 15-60 min post-resuscitation and will last for hours or days9. During this phase, a mismatch between CBF and tissue metabolism are likely uncoupled and may cause a secondary ischemic brain injury. This characterization was suggested by the cortical hypoxia observed after pediatric ACA24. It was reported that CBF drops to 30 to 50% of the normal flow in the period of hypoperfusion25. In our study, we showed that rCBF drops as low as 25 to 40% of uninjured control during 1-3 h post-ROSC. There may, however, be confounding factors; it is known that high concentration of isoflurane (2%) may lead to remarkable increase in the rCBF in all subcortical structures as well as most cortical structures26. Hence, the rCBF obtained from uninjured control animals under the influence of isoflurane (2%) may result in greater reductions in the observed rCBF. In other words, hyperemia caused by isoflurane may lead to exaggerated differences between healthy and CA-subjected animals.

Previously, a study using ASL-MRI showed early hyperperfusion in the cortex and the thalamus when compared to the amygdala/piriform in an 8-min ACA rodent model during the first 15 minutes post-ROSC, but no difference in rCBF from 30- to 60-min after ROSC was noted10. In contrast, we showed regional differences in rCBF manifested at 1-3 h post-ROSC using pCASL-MRI. Among the brain regions, the cortical rCBF also presented a noticeable higher level over time, while the rCBF in the brainstem sustained as the lowest level during the 1-3 h post-ROSC. The cerebral cortex is also well-known for the regional susceptibility under CA-induced global ischemia27. Dynamic changes of neuronal destruction have been reported in the cortex during the very early stage post-CA5. In contrast, the brainstem is recognized as the most resistant brain region to global ischemic injury28. It was previously revealed in live brain slices that oxygen/glucose deprivation elicited acutely damaging anoxic depolarization through vulnerable brain regions, such as the neocortex, the hippocampus and the thalamus, although little damage was shown in adjacent brainstem nuclei29. Our study is the first report showing that vulnerable cerebral regions exhibited higher rCBF levels compared to the resistant brain region during the early hypoperfusion phase, which provides a new insight into the relationship between rCBF and regional susceptibility following CA insult.

Among the regions in the brain, the hippocampus is known for being one of the brain regions that is more susceptible to global ischemic insult, especially its CA1 segment30,31. Delayed neuronal death and the greatest magnitude and rapidity of neuronal loss have been found in the CA1 sector5,32,33. One possible underlying mechanism is that the hippocampus has a higher metabolic rate compared to other brain regions leading to an even lower tolerance to the ischemic damage25. This seems to suggest that higher metabolic demand may play a role and in early reperfusion of this region.

But the more important observation was the dynamic changes of rCBF in the thalamus and the cerebral cortex that showed the ability to predict neurological recovery status after the 96 minutes post ROSC period. ROC curves have been utilized in differentiating CBF thresholds of ischemic penumbra and infarction core in stroke patients34. We showed that ACA-subjected rats progressed to a favorable recovery when the thalamic rCBF was above 50.84 ml/100g/min during the 1.5-h before arousal with an AUC value above 0.90, indicating an outstanding discriminating ability of this prediction35. In a pediatric ACA rat model studying rCBF in cortex, thalamus, amygdala and hippocampus, only thalamic rCBF recovered to sham rCBF values at 24-h after ROSC36. The thalamus is well recognized as an essential subcortical region involved in regulation of the cerebral cortical arousal via both thalamocortical and intrathalamic interactions37. Using spectral features of electroencephalography, Forgacs et al.38 discovered that the neocortical activity linked to functional integrity of corticothalamic circuitry (which is related to the acute recovery of consciousness) was associated positively with clinical outcomes in post-CA patients. Thalamus is also a main relay center in the ascending reticular activation system, which plays a core role in integration and coordination of the interactions between the brainstem and cerebral cortex39,40. By diffusion tensor tractography, an impaired ascending reticular activation system was found in a CA survivor and the temporal changes of this system was correlated with the improvement of recovery41. The role of the thalamus in relation to the ascending arousal network and its critical role in the recovery from unresponsiveness42 has also been described in patients with traumatic brain injury43. These observations highlight the key role that thalamus plays in the ascending arousal system, which may provide additional support of our findings that a strong correlation exists between the thalamic rCBF and neurologic outcomes in post-CA animals.

Not only the thalamus but also the cerebral cortex demonstrated significant increases in the rCBF with high NDS scores during the 1.5-h before arousal. Our results showed that before arousal, improvement of the cortical rCBF had an excellent discriminating ability in the prediction of neurological recovery. A favorable recovery after resuscitation is heralded by restoration of cortical and subcortical reperfusion which may have contribute to functional recovery. It was reported that measuring early somatosensory evoked potentials, as an indicator of thalamocortical evoked response, presented reliable prognostic marker in CA patients following resuscitation44. Our finding adds vital mechanistic evidence with early restoration of subcortical (thalamic) and cortical rCBF during the early hypoperfusion phase leading to electrophysiologic finding in early somatosensory evoked response as a marker of favorable neurological recovery after resuscitation.

While we have shown the select areas of rCBF recovery, our study also highlights the time-window to achieve reperfusion in these key areas. While some studies show that brain and heart injury during reperfusion may worsen outcome, our study shows that timely reperfusion of strategic areas of the brain lead to earlier recovery. During the early reperfusion period, potentially avoidable pathologic process may be achieved, where viable cells are not entirely dead45. Many studies have focused on shortened arrest time and resuscitation time but the period critical to reperfusion of the brain has not been well defined11. Our study suggests that the earlier timeframe for reperfusion maybe contribute to favorable neurologic recovery.

On one hand we have obtained significance results from the animal model study, but on the other hand, it is difficult to directly compare our data to human studies mainly because of different timing of rCBF imaging. There are few studies assessing rCBF post-resuscitation in CA patients and even fewer showing dynamic rCBF changes during the early stage of hypoperfusion and investigating the relationship between rCBF reperfusion and outcomes. These studies assessed rCBF during the several days after ROSC at timeframes outside of period where ischemic brain may still be amenable to reversal of injury46,47. In fact, related clinical studies are highly restricted to the patients’ conditions and the possibilities of serial imaging. Despite these current challenges of using MRI after CA, our study makes the case for doing human studies during the very early phases compared with those reported in the literature. Indeed, these related animal studies provide a good argument for doing the translational human studies in future.

Our study is important for revealing the rCBF dynamics during 1-3h post-ROSC, but with limitations. Firstly, the time course of our MRI scanning was limited to 1-3h after resuscitation excluding rCBF alterations in the first hour post-ROSC. This limitation was unavoidable since we have to transfer the animal from the surgical area to the MRI scanner. However, our findings pointed out that after 1.5-h post-ROSC, rCBF started to manifest positive correlations with neurological outcomes. We reported previously that global CMRO2 was coupled with global CBF during the MRI scanning12, but regional variability of cerebral oxygenation was found between the cortex and the thalamus in a pediatric ACA model24. We also believe that this study provided encouraging directions for functional imaging further down the period with worsening secondary brain injury and clinical manifestation of disorder of consciousness (i.e. 24 to 72 hours). In the future, the acquisition of regional information on oxygen metabolism will enable a better understanding in CA-induced ischemic brain damage.

We have previously performed histological analysis and demonstrated injury in this ACA model14,48. From a histopathological perspective, this is important, but not such pathology is not readily translatable. As a translational model, our emphasis on functional outcome such as rCBF and arousal from coma with the preservation of structures by neuroimaging and physiologic recovery may be more readily clinically assessed and may be more relevant than histopathology, such as the number of necrotic cells that have been injured or dead. Furthermore, from a clinical perspective, it is more important to have functional endpoints that are close to human condition49 such as unresponsiveness and arousal and clinical assessments such as NDS scores for this basic research to have a translational potential. In fact, the temporal rescue window as revealed in the thalamic rCBF indicates that the neurons are less damaged, suggesting that neurons may be responsive to potential therapies and hold potential for reversing injury. Our observation that a thalamic cutoff value of 50.84 ml/100g/min is consistent with the seminal study by Hossmann50 that showed the CBF below 50 ml/100g/min may cause cells to have dysfunction of protein synthesis, leading to more cell injury and ultimately cell death. We will investigate the relationship between less injured neurons and more robust blood vessel responsiveness in our future study.

In addition, we recognize that our sample size was limited to ten for a general investigation of rCBF dynamics and five per subgroup for comparisons between poor and good outcomes, respectively. But we have shown in multiple previous publications that a sample size of ten was adequate to analyze CBF alterations following resuscitation12 and subgroups of five enabled us to detect the differential between neurological outcomes 15,16. Despite the small numbers of animals studied here, the robust results provide us key biologic insights on research directions as we validate these observations in a larger cohort and more functional imaging and clinical assessment.

Lastly, we were not able to measure post-ROSC MAP due to technical limitations of MRI incompatibility with our equipment. We acknowledge that while MAP will help us understand how systemic blood pressure serves as a contributor to cerebral blood flow and its impact on the outcome, this is still an indirect assessment. In using ASL and measuring regional CBF in our study, we have a direct determinant of perfusion to the brain. In doing this, we were also able to measure blood flow brain in regional areas that are critical to recovery of arousal. However, the translational value of investigating MAP changes to CBF is also obvious considering potential clinical applications.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that rCBF dropped substantially during 1-3 hours after resuscitation with a significant variability in the key regions of the brain. There was a positive correlation between rCBF alterations and neurological recovery at 1.5-h post-ROSC. A significant improvement of the rCBF in critical brain regions, including the thalamus, the hippocampus and the cortex at 1-3 hours post-ROSC, may play a key role in predicting favorable neurological outcome. While needing further validation, these observations may help guide the clinical application of MRI in studying early rCBF differentiation of CA patients and furthermore, possibly direct therapeutic approaches in targeting vulnerable regions, and the timing of modulating rCBF restoration leading to better neurologic outcomes. Future research on early recovery of rCBF, cerebral autoregulation function, reperfusion injury/recovery, tissue oxygenation in critical brain regions and their associations to long-term neurological outcome is necessary.

Source of support

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 HL071568-15, R01 HL139158-01A1, R01 AG064792, and R21 AG058413.

Footnotes

Declarations

The authors declare that the manuscript complies with all instructions to authors. Authorship requirements have been met and the final manuscript was approved by all authors. Also, this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal for publication. This study was in compliance with ethical standards for animal studies. The ARRIVE Compliance Questionnaire has been used as the reporting checklist for this manuscript.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet] 2019. [cited 2021 Jul 17];139(10). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallikethi-Reddy S, Briasoulis A, Akintoye E, et al. Incidence and Survival After In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Nonelderly Adults: US Experience, 2007 to 2012. Circ: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes [Internet] 2017. [cited 2021 Jul 17];10(2). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolan JP, Neumar RW, Adrie C, et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication: A Scientific Statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Stroke. Resuscitation 2008;79(3):350–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekhon MS, Ainslie PN, Griesdale DE. Clinical pathophysiology of hypoxic ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest: a “two-hit” model. Critical Care 2017;21(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawai K, Nitecka L, Ruetzler CA, et al. Global Cerebral Ischemia Associated with Cardiac Arrest in the Rat: I. Dynamics of Early Neuronal Changes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1992;12(2):238–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendrickx HHL, Rao GR, Safar P, Gisvold SE. Asphyxia, cardiac arrest and resuscitation in rats. I. Short term recovery. Resuscitation 1984;12(2):97–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz L, Ebmeyer U, Safar P, Radovsky A, Neumar R. Outcome Model of Asphyxial Cardiac Arrest in Rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1995;15(6):1032–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, Miao P, Modi HR, Garikapati S, Koehler RC, Thakor NV. Therapeutic hypothermia promotes cerebral blood flow recovery and brain homeostasis after resuscitation from cardiac arrest in a rat model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019;39(10):1961–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iordanova B, Li L, Clark RSB, Manole MD. Alterations in Cerebral Blood Flow after Resuscitation from Cardiac Arrest. Front Pediatr 2017;5:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drabek T, Foley LM, Janata A, et al. Global and regional differences in cerebral blood flow after asphyxial versus ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in rats using ASL-MRI. Resuscitation 2014;85(7):964–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil KD, Halperin HR, Becker LB. Cardiac Arrest: Resuscitation and Reperfusion. Circ Res 2015;116(12):2041–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei Z, Wang Q, Modi HR, et al. Acute-stage MRI cerebral oxygen consumption biomarkers predict 24-hour neurological outcome in a rat cardiac arrest model. NMR in Biomedicine 2020;33(11):e4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geocadin RG, Muthuswamy J, Sherman DL, Thakor NV, Hanley DF. Early electrophysiological and histologic changes after global cerebral ischemia in rats. Movement Disorders 2000;15(S1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modi HR, Wang Q, Gd S, et al. Intranasal post-cardiac arrest treatment with orexin-A facilitates arousal from coma and ameliorates neuroinflammation. PLoS ONE 2017;12(9):e0182707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geocadin RG, Ghodadra R, Kimura T, et al. A novel quantitative EEG injury measure of global cerebral ischemia. Clinical Neurophysiology 2000;111(10):1779–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthuswamy J, Kimura T, Ding MC, Geocadin R, Hanley DF, Thakor NV. Vulnerability of the thalamic somatosensory pathway after prolonged global hypoxic–ischemic injury. Neuroscience 2002;115(3):917–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2015;73(1):102–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirschler L, Debacker CS, Voiron J, Köhler S, Warnking JM, Barbier EL. Interpulse phase corrections for unbalanced pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling at high magnetic field. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2018;79(3):1314–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirschler L, Munting LP, Khmelinskii A, et al. Transit time mapping in the mouse brain using time-encoded pCASL. NMR in Biomedicine 2018;31(2):e3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aslan S, Xu F, Wang PL, et al. Estimation of labeling efficiency in pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2010;63(3):765–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geocadin RG, Sherman DL, Christian Hansen H, et al. Neurological recovery by EEG bursting after resuscitation from cardiac arrest in rats. Resuscitation 2002;55(2):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X Classification accuracy and cut point selection. Statistics in Medicine 2012;31(23):2676–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker LB, Aufderheide TP, Geocadin RG, et al. Primary Outcomes for Resuscitation Science Studies: A Consensus Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;124(19):2158–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manole MD, Kochanek PM, Bayır H, et al. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring identifies cortical hypoxia and thalamic hyperoxia after experimental cardiac arrest in rats. Pediatr Res 2014;75(2):295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busl KM, Greer DM. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury: pathophysiology, neuropathology and mechanisms. NeuroRehabilitation 2010;26(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C-X, Patel S, Wang DJJ, Zhang X. Effect of high dose isoflurane on cerebral blood flow in macaque monkeys. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2014;32(7):956–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geocadin RG, Koenig MA, Jia X, Stevens RD, Peberdy MA. Management of Brain Injury After Resuscitation From Cardiac Arrest. Neurologic Clinics 2008;26(2):487–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Björklund E, Lindberg E, Rundgren M, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Englund E. Ischaemic brain damage after cardiac arrest and induced hypothermia--a systematic description of selective eosinophilic neuronal death. A neuropathologic study of 23 patients. Resuscitation 2014;85(4):527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brisson CD, Hsieh Y-T, Kim D, Jin AY, Andrew RD. Brainstem Neurons Survive the Identical Ischemic Stress That Kills Higher Neurons: Insight to the Persistent Vegetative State. PLOS ONE 2014;9(5):e96585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito U, Spatz M, Walker JT, Klatzo I. Experimental cerebral ischemia in mongolian gerbils. I. Light microscopic observations. Acta Neuropathol 1975;32(3):209–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt-Kastner R, Freund TF. Selective vulnerability of the hippocampus in brain ischemia. Neuroscience 1991;40(3):599–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirino T Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Research 1982;239(1):57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadowski M, Wisniewski HM, Jakubowska-Sadowska K, Tarnawski M, Lazarewicz JW, Mossakowski MJ. Pattern of neuronal loss in the rat hippocampus following experimental cardiac arrest-induced ischemia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 1999;168(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandera E, Botteri M, Minelli C, Sutton A, Abrams KR, Latronico N. Cerebral Blood Flow Threshold of Ischemic Penumbra and Infarct Core in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review. Stroke 2006;37(5):1334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandrekar JN. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve in Diagnostic Test Assessment. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2010;5(9):1315–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foley LM, Clark RSB, Vazquez AL, et al. Enduring Disturbances in Regional Cerebral Blood Flow and Brain Oxygenation at 24 Hours after Asphyxial Cardiac Arrest in Developing Rats. Pediatr Res 2017;81(1–1):94–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiff ND. Central thalamic contributions to arousal regulation and neurological disorders of consciousness. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1129:105–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forgacs PB, Frey H-P, Velazquez A, et al. Dynamic regimes of neocortical activity linked to corticothalamic integrity correlate with outcomes in acute anoxic brain injury after cardiac arrest. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 2017;4(2):119–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 1993;262(5134):679–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edlow BL, Takahashi E, Wu O, et al. Neuroanatomic Connectivity of the Human Ascending Arousal System Critical to Consciousness and Its Disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012;71(6):531–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jang SH, Hyun YJ, Lee HD. Recovery of consciousness and an injured ascending reticular activating system in a patient who survived cardiac arrest. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet] 2016. [cited 2020 Jul 12];95(26). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4937947/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snider SB, Bodien YG, Frau-Pascual A, Bianciardi M, Foulkes AS, Edlow BL. Ascending arousal network connectivity during recovery from traumatic coma. NeuroImage: Clinical 2020;28:102503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snider SB, Bodien YG, Bianciardi M, Brown EN, Wu O, Edlow BL. Disruption of the ascending arousal network in acute traumatic disorders of consciousness. Neurology 2019;93(13):e1281–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunko E, de Beyl DZ. Prognostic value of early cortical somatosensory evoked potentials after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 1987;66(1):15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becker LB. New concepts in reactive oxygen species and cardiovascular reperfusion physiology. Cardiovascular Research 2004;61(3):461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollock JM, Whitlow CT, Deibler AR, et al. Anoxic Injury-Associated Cerebral Hyperperfusion Identified with Arterial Spin-Labeled MR Imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29(7):1302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manchester LC, Lee V, Schmithorst V, Kochanek PM, Panigrahy A, Fink EL. Global and Regional Derangements of Cerebral Blood Flow and Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging after Pediatric Cardiac Arrest. The Journal of Pediatrics 2016;169:28–35.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jia X, Koenig MA, Shin H-C, et al. Improving neurological outcomes post-cardiac arrest in a rat model: Immediate hypothermia and quantitative EEG monitoring. Resuscitation 2008;76(3):431–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, et al. Update of the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable Preclinical Recommendations. Stroke 2009;40(6):2244–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hossmann K-A. Viability thresholds and the penumbra of focal ischemia. Ann Neurol 1994;36(4):557–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]