Abstract

Objective:

Factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) receipt during pregnancy are largely unknown. We quantified the contribution of individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors to racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD during pregnancy and postpartum among Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study used regression and nonlinear decomposition to examine how individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors explain racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt among Medicaid-enrolled women with OUD who had a live birth from 2011-2017. The exposure was self-reported race and ethnicity. The outcomes were any MOUD receipt during pregnancy or postpartum. All factors included were identified from the literature.

Results:

Racial-ethnic disparities in individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors explained 15.8% of the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy and 68.9% of the disparity in the postpartum period. Despite comparable healthcare utilization, nonwhite/Hispanic women were diagnosed with OUD 37 days later in pregnancy, on average, than non-Hispanic White women, which was the largest contributor to the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy (111.0%). The racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy was the largest contributor (112.2%) to the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD in the postpartum period.

Conclusions:

Later diagnosis of OUD in pregnancy among nonwhite/Hispanic women partially explains the disparities in MOUD receipt in this population. Universal substance use screening earlier in pregnancy, combined with connecting patients to evidence-based and culturally competent care, is one approach that could close the observed racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, pregnancy, substance use, disparities

INTRODUCTION

Opioid use disorder (OUD) among pregnant women results in adverse maternal and child health outcomes.1-3 Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) with methadone or buprenorphine is recommended during pregnancy1,4-6 and the postpartum period. Despite these recommendations, prior research has found low rates of MOUD utilization among pregnant women with OUD in the United States with only 50-60% receiving any MOUD during pregnancy.2,7 Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women are less likely to receive, continue, and report consistent use of MOUD, defined as receiving MOUD for at least 6 months before delivery, compared with non-Hispanic White women.7-10 Among those who receive MOUD, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women have been found to receive lower doses of methadone during pregnancy than non-Hispanic White women.11

Factors contributing to the gap between treatment need and receipt among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women remain largely unknown. Systemic racism by the healthcare system, which maintains the privilege of non-Hispanic White groups, is exemplified by additional structural barriers that nonwhite or Hispanic groups face to healthcare. These include a shortage of healthcare providers serving nonwhite neighborhoods, cultural stereotypes that lead to lack of or poor quality of care from providers, and employment and housing policies driving socioeconomic inequities.12,13 To design interventions that address systemic racism and eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt during pregnancy and the postpartum period, we must first understand the extent to which modifiable factors explain these disparities, including those at the levels of the individual, healthcare system, and community. Thus, the objectives for this research were to 1) quantify the racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt during pregnancy and postpartum among Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD; and 2) identify the extent to which these disparities are explained by racial-ethnic disparities in individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors.

METHODS

Design

We used administrative healthcare data from Pennsylvania Medicaid to conduct a regression decomposition analysis to quantify factors that explain racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt during pregnancy and the postpartum period. These data contain a census of inpatient, outpatient, provider, and pharmacy records, including enrollment records which contain information regarding demographic characteristics, such as patient-reported race and ethnicity. Pennsylvania Medicaid provides reimbursement for both buprenorphine and methadone. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cohort studies and was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Our study included all Medicaid-enrolled women ages 15-44 years who had a live birth from October 1, 2011-September 30, 2017, and a diagnosis of OUD at any time in the 280 days prior to delivery. All women were followed from 280 days prior to date of delivery through twelve weeks after date of delivery (hereafter referred to as postpartum). To allow enough time in pregnancy to observe MOUD receipt, we required all women to have at least 8 weeks of enrollment in Medicaid during pregnancy. Methods for identifying live births have been described previously.7 We identified OUD using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM) and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes for OUD (see eTable 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which lists diagnosis codes). Our final analytic sample included 13,320 deliveries to 11,521 women.

Outcomes

There were two binary outcomes: 1) any MOUD (either methadone or buprenorphine) received during pregnancy and 2) any MOUD received in the twelve weeks after delivery. Buprenorphine use was defined as having at least one outpatient prescription fill for buprenorphine and was identified using National Drug Codes (NDCs) for buprenorphine formulations for OUD (a complete list of NDCs is available from the authors upon request). Methadone use was defined as having either procedure codes H0020 and/or J1230 in outpatient or professional claims.

Exposures

Definition of race and ethnicity

Medicaid enrollees are required to report their race and ethnicity upon enrollment, so there were no missing data for race or ethnicity. Reported race categories include White, American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and Other. Ethnicity is categorized as Hispanic or Latino/Latina and non-Hispanic or Latino/Latina, hereafter referred to as “Hispanic” and “Non-Hispanic”, respectively.

Because the sample sizes of Hispanic women (N=404) and non-Hispanic women who report their race as “other” (N=199) were significantly smaller than those of non-Hispanic White (N=9,982) and non-Hispanic Black (N=947) women, the race and ethnicity categories were combined to create a racial-ethnic category consisting of non-Hispanic White women or nonwhite/Hispanic women (i.e., women who reported their race as Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or women who reported their ethnicity as Hispanic). The distribution of race and ethnicity categories was consistent with similar studies of pregnant individuals diagnosed with OUD.2,14,15

Individual-level factors

Individual factors included demographic characteristics, medical comorbidities, and substance use during pregnancy. Demographic characteristics consisted of age at delivery (15–19, 20–34, or 35–44 years), and racial-ethnic category (non-Hispanic White, nonwhite/Hispanic). Based on previous studies of MOUD for this population7, we included the following medical comorbidity diagnoses: pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus, asthma, thyroid disorder, HIV, and HCV. In addition to opioids, studies have shown that pregnant women with OUD report tobacco, alcohol, and other substance use during pregnancy.16 Almost 35% percent of pregnant women with OUD screen positive for other substance use during pregnancy17 and have comorbid conditions including depression, anxiety, mood disorders, and other psychiatric conditions.18 Thus, we included diagnoses of anxiety disorder, mood disorder, or other psychiatric disorders, and reported tobacco use, alcohol use, or polysubstance use during pregnancy in the final adjusted model. Other psychiatric disorders included psychotic disorders and schizophrenia. Polysubstance use was defined as at least one co-occurring diagnosis of other substance use, excluding alcohol, tobacco, and opioids (e.g., amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, sedative, or hallucinogens). All comorbidities and substance use during pregnancy were identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (see eTable 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which lists diagnosis codes).

Healthcare access and quality19 factors

Weeks enrolled in Medicaid during pregnancy, the number of days between OUD diagnosis and delivery, and any behavioral health visits were included in the analysis as healthcare access and quality factors, consistent with previous studies of factors that impact MOUD utilization.9,20,21 Medicaid eligibility categories (i.e., pregnancy-related, disability, or income-related eligibility) were also included. Behavioral health visits during pregnancy were identified using procedure codes. In postpartum analyses, any MOUD received during pregnancy was also added as a healthcare access and quality factor.

Community factors

Previous studies on racial-ethnic disparities in substance use disorder treatment included measures of socioeconomic status, such as employment status, highest educational attainment, and federal poverty level.22-24 We included county-level measures of unemployment rates, percent living in poverty according to the federal poverty threshold, and housing unit density for all counties in Pennsylvania using information from the Area Health Resource File25, as individual level information for these variables were unavailable. The housing unit density is calculated as the number of housing units per square mile divided by the total population at the county-level based on census data.26 County of residence was categorized as urban or rural based on population density as defined by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania.27

Statistical Analysis

Pregnancy was the unit of analysis. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations between individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors and MOUD receipt during pregnancy or the postpartum period overall and by racial-ethnic category. To explain disparities in MOUD receipt by racial-ethnic group, we used the Fairlie nonlinear decomposition method.28 This is a nonlinear extension of the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition method, which breaks down the overall disparity in the average probability of an outcome between two groups into two components: group differences in the distributions of observable variables (i.e., the “explained” component) and group differences in the coefficients due to within group processes or unobserved variables (i.e., the “unexplained” component).28-30 In this study, the explained component reflects the contributions of racial-ethnic disparities in individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors towards the overall racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt during pregnancy and the post-partum period. The unexplained component represents the portion of the overall disparity that is not explained by factors in the model, such as unmeasured or unobserved variables, which cannot be easily distinguished.28

The explained component or explained MOUD disparity by the included factors is the sum of the contributions of all factors in the model, each of which is calculated as the change in the average predicted probability of MOUD receipt after replacing the nonwhite/Hispanic distribution of a factor with that of the non-Hispanic White distribution, assuming the distributions of the other factors are held constant.28-31 The process of estimating the contribution of a factor is described in the Supplemental Digital Content (see eAppendix Text, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which provides more details of decomposition). Stata version 16.1 was used to perform all analyses. Decomposition was performed using the ‘fairlie’ package in Stata.32

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

We identified 13,320 pregnancies to 11,521 women that resulted in a live or still birth from January 1, 2011-September 30, 2017, with a documented diagnosis of OUD (Table 1). Among these pregnancies, 7,754 women (58%) received any MOUD during pregnancy and 6,787 women (51%) received any MOUD postpartum. This differed significantly by racial-ethnic category, as 7,138 (61%) non-Hispanic White pregnant women received MOUD during pregnancy compared with 616 (37%) nonwhite/Hispanic pregnant women. In the postpartum period, 6,241 (54%) non-Hispanic White women received MOUD compared with 546 (32%) nonwhite/Hispanic women. Compared with non-Hispanic White women (178.4), nonwhite/Hispanic women (141.4) were diagnosed with OUD, on average, 37 days later.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Deliveries among Pregnant Women with OUD, Overall and by Racial-Ethnic Category, 2011–2017

| Deliveries, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (n=13320) | Non-Hispanic White (n=11635) |

Nonwhite/Hispanica (n=1685) |

| MOUD | |||

| Any MOUD during pregnancy | 7754 (58.2) | 7138 (61.4) | 616 (36.6) |

| Any MOUD 12 weeks after delivery | 6787 (51.0) | 6241 (53.6) | 546 (32.4) |

| Individual factors | |||

| Age at delivery, mean (SD) | 28.3 (4.7) | 28.3 (4.6) | 28.5 (5.1) |

| Medical comorbidities in pregnancy | |||

| Anxiety disorder | 4798 (36.0) | 4228 (36.3) | 570 (33.8) |

| Mood disorder | 6176 (46.4) | 5328 (45.8) | 848 (50.3) |

| Psychiatric disorderb | 376 (2.8) | 244 (2.1) | 132 (7.8) |

| HCV | 4030 (30.3) | 3799 (32.7) | 231 (13.7) |

| HIV | 73 (0.6) | 51 (0.4) | 22 (1.3) |

| Thyroid disorder | 571 (4.3) | 505 (4.3) | 66 (3.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 179 (1.3) | 138 (1.2) | 41 (2.4) |

| Asthma | 1930 (15.0) | 1553 (13.4) | 377 (22.4) |

| Gestational diabetes | 846 (6.4) | 734 (6.3) | 112 (6.6) |

| Non-opioid substance use in pregnancy | |||

| Alcohol | 942 (7.1) | 765 (6.6) | 177 (10.5) |

| Tobacco | 10194 (76.5) | 9052 (77.8) | 1142 (67.8) |

| Polysubstance usec | 7217 (54.2) | 6157 (52.9) | 1060 (62.9) |

| Healthcare access and quality factors | |||

| Days between OUD diagnosis and delivery, mean (SD) | 173.7 (99.4) | 178.4 (98.3) | 141.4 (101.3) |

| Weeks enrolled in Medicaid in pregnancy, mean (SD) | 37.3 (6.1) | 37.3 (6.1) | 37.5 (6.0) |

| Behavioral health visit (1 visit or more) | 5392 (40.5) | 4629 (39.8) | 763 (45.3) |

| Medicaid eligibility category | |||

| Disability-related eligibilityd | 2438 (18.3) | 2089 (18.0) | 349 (20.7) |

| Medicaid expansione | 2949 (22.1) | 2576 (22.1) | 373 (22.1) |

| Pregnancy or parental eligibilityf | 12299 (92.3) | 10806 (92.9) | 1493 (88.6) |

| Community factors | |||

| Unemployment rate | 6.4 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.5) | 6.7 (1.8) |

| Percent in poverty | 14.1 (5.5) | 13.6 (4.9) | 17.9 (7.4) |

| Housing densityg | 44.7 (4.6) | 44.9 (4.7) | 43.2 (3.2) |

| County of residence | |||

| Urbanh | 7603 (57.1) | 6266 (53.9) | 1337 (79.4) |

Includes non-Hispanic Black women, non-Hispanic Asian women, Hispanic women, and Native American women

Defined as any diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or schizophrenia

Defined as any co-occurring diagnosis of substance use during pregnancy other than alcohol, tobacco, or opioid use

Includes enrollees in Healthy Horizons, a Pennsylvania Medicaid program that primarily subsidizes Medicare premiums for elderly individuals and disabled individuals and individuals who are chronically disabled

Refers to Medicaid expansion after 2015

Includes low-income families and qualified pregnant women who meet Pennsylvania Medicaid eligibility criteria

Calculated as the number of housing units per square mile divided by the total population at the county-level based on census data

Urban and rural definitions are based on population density as defined by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

Adjusted odds ratios were estimated to understand how individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors are associated with MOUD receipt during pregnancy and the postpartum period across racial-ethnic categories and to inform the decomposition results (Table 2). Regression estimates for each racial-ethnic category can be found in the supplement (see eTables 2 and 3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which includes regression coefficients by racial-ethnic category). Non-Hispanic White women had 2.5 times the odds of receiving MOUD during pregnancy (95% CI: 2.24, 2.85) relative to nonwhite/Hispanic women (Table 2). Alcohol use (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.6 [95% CI: 0.52, 0.69]) and diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (aOR, 0.64 [95% CI: 0.51, 0.8]) were associated with lower odds of MOUD receipt during pregnancy. Pregnant women who received MOUD during pregnancy had 35 times the odds of receiving MOUD postpartum compared with women who did not receive MOUD during pregnancy (aOR, 35.14 [95% CI: 31.48, 39.23]). Other factors significantly associated with MOUD receipt included HCV diagnosis, gestational diabetes, reported polysubstance use during pregnancy, and urban county of residence, all of which were associated with greater odds of MOUD receipt in pregnancy and postpartum, except gestational diabetes, which was associated with reduced odds of MOUD receipt.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of MOUD receipt among non-Hispanic White and Nonwhite/Hispanica Pregnant Women with OUD, 2011–2017

| Any MOUD during pregnancy | Any MOUD postpartum (12 weeks after delivery) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Individual factors | ||

| Racial-ethnic category | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.53 (2.24, 2.85) | 1.61 (1.38, 1.88) |

| Nonwhite/Hispanic | 1 | 1 |

| Age at delivery (years) | 1.01 (1, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) |

| Medical comorbidities in pregnancy | ||

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.08 (0.99, 1.18) | 1.11 (1, 1.23) |

| No anxiety disorder diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Mood disorder | 0.87 (0.8, 0.95) | 0.97 (0.88, 1.08) |

| No mood disorder diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Psychiatric disorderb | 0.64 (0.51, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.53, 0.94) |

| No psychiatric disorder diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| HCV | 1.31 (1.2, 1.42) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.18) |

| No HCV diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| HIV | 0.91 (0.55, 1.5) | 1.08 (0.58, 1.99) |

| No HIV diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Thyroid disorder | 0.88 (0.74, 1.06) | 0.92 (0.72, 1.17) |

| No thyroid disorder diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.98 (0.7, 1.38) | 1.05 (0.68, 1.62) |

| No diabetes mellitus diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Asthma | 0.94 (0.84, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.16) |

| No asthma diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Gestational diabetes | 0.71 (0.6, 0.83) | 0.82 (0.68, 1) |

| No gestational diabetes diagnosis | 1 | 1 |

| Non-opioid substance use in pregnancy | ||

| Alcohol | 0.6 (0.52, 0.69) | 0.79 (0.66, 0.95) |

| No reported alcohol use | 1 | 1 |

| Tobacco | 1.16 (1.06, 1.27) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) |

| No reported tobacco use | 1 | 1 |

| Polysubstance usec | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) |

| No reported polysubstance use | 1 | 1 |

| Healthcare access and quality factors | ||

| Days between OUD diagnosis and delivery | 1 (1, 1) | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99) |

| Weeks enrolled in Medicaid in pregnancy | 1 (0.99, 1) | 0.99 (0.98, 1) |

| Any MOUD use during pregnancy | N/A | 35.14 (31.48, 39.23) |

| No MOUD use during pregnancy | N/A | 1 |

| Behavioral health visit (1 visit or more) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) | 1.15 (1.04, 1.27) |

| No behavioral health visits | 1 | 1 |

| Medicaid eligibility category | ||

| Disability-related eligibilityd | 0.98 (0.87, 1.1) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.3) |

| No disability-related eligibility | 1 | 1 |

| Medicaid expansione | 0.74 (0.67, 0.81) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.13) |

| No Medicaid expansion eligibility | 1 | 1 |

| Pregnancy or parental eligibilityf | 1.37 (1.17, 1.61) | 1.29 (1.07, 1.56) |

| No pregnancy or parental eligibility | 1 | 1 |

| Community factors | ||

| Unemployment rate | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.94 (0.9, 0.98) |

| Percent in poverty | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) |

| Housing densityg | 1 (0.99, 1) | 0.99 (0.97, 1) |

| County of residence | ||

| Urbanh | 1.21 (1.11, 1.31) | 1.2 (1.08, 1.34) |

| Rural | 1 | 1 |

Includes non-Hispanic Black women, non-Hispanic Asian women, Hispanic women, and Native American women

Defined as any diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or schizophrenia

Defined as any co-occurring diagnosis of substance use during pregnancy other than alcohol, tobacco, or opioid use

Includes enrollees in Healthy Horizons, a Pennsylvania Medicaid program that primarily subsidizes Medicare premiums for elderly individuals and disabled individuals and individuals who are chronically disabled

Refers to Medicaid expansion after 2015

Includes low-income families and qualified pregnant women who meet Pennsylvania Medicaid eligibility criteria

Calculated as the number of housing units per square mile divided by the total population at the county-level based on census data

Urban and rural definitions are based on population density as defined by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

Decomposition Results

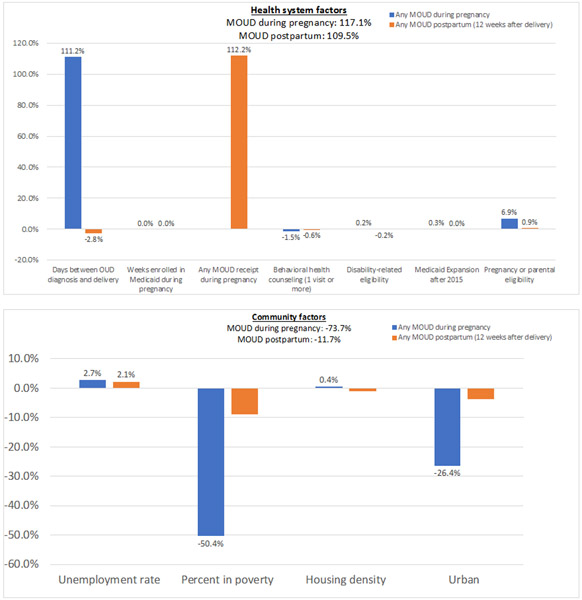

Results of the Fairlie decomposition are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. The overall disparity of MOUD receipt during pregnancy (0.25) is calculated as the difference in the average predicted probabilities of MOUD receipt during pregnancy between non-Hispanic White women and nonwhite/Hispanic women.28-30 This suggests that the total disparity in MOUD during pregnancy between these two racial-ethnic groups is 25 percentage points, favoring non-Hispanic White women.

TABLE 3.

Decomposition of Racial-Ethnic Disparities in MOUD Receipt among Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorder

| Any MOUD during pregnancy | Any MOUD postpartum (12 weeks after delivery) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overall disparitya | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| Explained componentb | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| % Explainedc | 15.8% | 68.9% |

| Contribution of each factor to the explained component (%) | ||

| Individual factors | ||

| Age at delivery | −1.6% (−2.7, −0.5) | −0.6% (−1.2, −0.1) |

| Medical comorbidities in pregnancy | ||

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.4% (−0.1, 3) | 0.2% (0, 0.5) |

| Mood disorder | 2.9% (0.9, 4.9) | 0% (−0.3, 0.5) |

| Psychiatric disorderd | 12.1% (6, 18.2) | 1.3% (0.1, 2.5) |

| HCV | 29.8% (20.4, 39.2) | 1.1% (−0.7, 2.9) |

| HIV | 0.4% (−1.9, 2.7) | 0% (−0.5, 0.4) |

| Thyroid disorder | −0.3% (−1.1, 0.3) | 0% (−0.1, 0.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0% (−2.1, 2.3) | 0% (−0.6, 0.4) |

| Asthma | 2.8% (−2.2, 7.9) | −0.1% (−1.2, 0.9) |

| Gestational diabetes | 0.8% (0, 1.7) | 0.1% (0, 0.3) |

| Non-opioid substance use in pregnancy | ||

| Alcohol | 11% (7.9, 14.2) | 0.7% (0.1, 1.3) |

| Tobacco | 8.3% (3.5, 13.1) | 0.6% (−0.1, 1.5) |

| Polysubstance usee | −11.3% (−15.4, −7.1) | −0.9% (−1.7, 0) |

| Healthcare access and quality factors | ||

| Days between OUD diagnosis and delivery | 111.2% (102.4, 120) | −2.8% (−4.7, −0.9) |

| Weeks enrolled in Medicaid in pregnancy | 0% (−0.4, 0.4) | 0% (−0.1, 0.1) |

| Any MOUD receipt during pregnancy | 112.2% (108.2, 116.3) | |

| Behavioral health visit (1 visit or more) | −1.5% (−3.9, 0.7) | −0.6% (−1.1, 0) |

| Medicaid eligibility category | ||

| Disability-related eligibilityf | 0.2% (−1.3, 1.7) | −0.2% (−0.5, 0) |

| Medicaid Expansion after 2015g | 0.3% (−0.4, 1.2) | 0% (−0.1, 0.1) |

| Pregnancy or parental eligibilityh | 6.9% (3.5, 10.4) | 0.9% (0.1, 1.6) |

| Community factors | ||

| Unemployment rate | 2.7% (−4.5, 9.9) | 2.1% (0.5, 3.7) |

| Percent in poverty | −50.4% (−72.1, −28.6) | −8.9% (−13.4, −4.4) |

| Housing densityi | 0.4% (−7.4, 8.3) | −1.2% (−2.8, 0.2) |

| County of residence | ||

| Urbanj | −26.4% (−37.4, −15.4) | −3.7% (−5.9, −1.5) |

Measures the overall disparity in any MOUD receipt during pregnancy or postpartum between non-Hispanic White women and nonwhite/Hispanic women

Reflects the contribution of racial-ethnic disparities in individual, healthcare system, and community factors towards the overall racial-ethnic disparity of MOUD receipt during pregnancy and postpartum. The unexplained component represents the portion of this overall disparity that is not explained by factors in the model, such as discrimination, personal preferences, or uncertainty due to residuals.

Measures the percentage of the explained component due to racial-ethnic disparities in a specific factor

Defined as any diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or schizophrenia

Defined as any co-occurring diagnosis of substance use during pregnancy other than alcohol, tobacco, or opioid use

Includes enrollees in Healthy Horizons, a Pennsylvania Medicaid program that primarily subsidizes Medicare premiums for elderly individuals and disabled individuals (Pennsylvania Department of Human Services 2019), and individuals who are chronically disabled

Refers to Medicaid expansion after 2015

Includes low-income families and qualified pregnant women who meet Pennsylvania Medicaid eligibility criteria

Calculated as the number of housing units per square mile divided by the total population at the county-level based on census data

Urban and rural definitions are based on population density as defined by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania

Note: The confidence intervals were derived from standard errors, which were estimated using the Delta method.

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

Figure.

Decomposition Results of Individual Factors to Racial-Ethnic Disparities in MOUD during Pregnancy and Postpartum

Panel A. Individual Factors

Panel B. Health system factors

Panel C. Community Factors

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

The factors included in the model explain 15.8% of the overall disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy between non-Hispanic White women and nonwhite/Hispanic women, indicating that most of the overall disparity is due to unobserved factors. The contribution of each factor is expressed as a percentage of the explained MOUD disparity, which represents the percentage of the MOUD disparity explained by the racial-ethnic disparity in the distribution of a factor. In other words, the explained component or MOUD disparity is decomposed into the racial-ethnic disparities in the distribution of each factor. A positive percentage for a factor indicates that eliminating the racial-ethnic disparity in that factor (i.e., the distributions in that factor between non-Hispanic White and nonwhite/Hispanic women are the same) would reduce the MOUD disparity. Conversely, a negative percentage suggests that eliminating the racial-ethnic disparity in that factor would increase the MOUD disparity. Thus, it is possible for percentages to be greater than 100% if there are negative percentages in the decomposition model. The sum of the percentages for each factor will be approximately 100.

Racial-ethnic disparities in the number of days between OUD diagnosis and delivery explained 111% of the MOUD disparity in pregnancy. This means that if nonwhite/Hispanic pregnant women were diagnosed with OUD at the same time as non-Hispanic White pregnant women, the explained disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy would substantially decrease, assuming the distributions of other factors are similar between both groups and there were no subsequent changes in the distributions of these factors as a result. Other factors that significantly explained the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy were diagnosis of HCV (30%), other psychiatric disorder (12%), alcohol use during pregnancy (11%), and tobacco use during pregnancy (8%). This is consistent with Tables 1 and 2, as there is a higher percentage of non-Hispanic White women than nonwhite/Hispanic women diagnosed with HCV or reported tobacco use during pregnancy, which are both associated with an increased odds of MOUD receipt in pregnancy, thereby increasing the racial-ethnic MOUD disparity. A higher percentage of nonwhite/Hispanic women were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder or reported alcohol use in pregnancy than non-Hispanic White women. These factors are associated with a decreased likelihood of MOUD receipt in pregnancy, which increases the MOUD disparity between non-Hispanic White and nonwhite/Hispanic women.

Conversely, polysubstance use (−11.3%), urbanicity (−26.4%), and percent living in poverty (−50.4%) contributed negatively to the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy between nonwhite/Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women. This means that if nonwhite/Hispanic women experienced the same rates of polysubstance use during pregnancy as non-Hispanic White women, the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD would be even greater than observed, holding other factors constant. In other words, these factors are protective for nonwhite/Hispanic women by mitigating the MOUD disparity between these two racial-ethnic groups.

Decomposition results for MOUD use in the postpartum period suggest that the factors explain almost 69% of the overall disparity between nonwhite/Hispanic and non-Hispanic White pregnant women. This is primarily due to the inclusion of any MOUD receipt during pregnancy as a healthcare access and quality factor, which was the largest contributor to the explained component (112%). These results indicate that the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt in the postpartum period is largely explained by the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD receipt during pregnancy. Decomposition estimates for individuals with one delivery during the measurement period (see eTable 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1) were similar to the main cohort, which included individuals with multiple deliveries. Decomposition estimates generated separately for non-Hispanic Black women, Hispanic women, and other non-Hispanic and nonwhite women (see eTables 5 and 6, Supplemental Digital Content 1) were also similar to the nonwhite/Hispanic racial-ethnic category, used in the main decomposition (Table 3).

Post hoc analyses

We performed post-hoc analyses to examine racial-ethnic disparities in healthcare visits during pregnancy, which could have contributed to disparities in the timing of OUD diagnosis, as pregnant women presenting later for prenatal care would have been diagnosed with OUD at a later gestational age. Specifically, we examined the median number of healthcare visits between the date of conception (280 days from the delivery date) and the date of OUD diagnosis by racial-ethnic category (Table 4). Compared with non-Hispanic White women, nonwhite/Hispanic women had a higher median number of office or outpatient visits (5 vs. 4), emergency department or urgent care visits (2 vs. 1), and psychiatric services visits (2.5 vs. 2). Nonwhite/Hispanic women also had the same median number of inpatient hospitalizations (n=2) and visits for substance use disorder services (n=3) as non-Hispanic White women. Thus, the later diagnosis of OUD during pregnancy for nonwhite/Hispanic women was not due to a later presentation for healthcare services during pregnancy.

TABLE 4:

Post-Hoc Analysis of Frequency of Healthcare Visits in Pregnancy Prior to OUD Diagnosis among Medicaid-Enrolled Women, by Racial-Ethnic Category

| Non-Hispanic White | Nonwhite/Hispanica | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of healthcare visit | Median number of visits (IQR) | Median number of visits (IQR) |

| Office/Outpatientb | 4 (2,8) | 5 (2,10) |

| Emergency Dept or Urgent Care | 1 (1,3) | 2 (1,3) |

| Inpatient Hospitalization | 2 (1,3) | 2 (1,4) |

| Substance use disorder servicesc | 3 (1,8) | 3 (1,8) |

| Psychiatric Servicesd | 2 (1,3) | 2.5 (1,4) |

Includes non-Hispanic Black women, non-Hispanic Asian women, Hispanic women, and Native American women

Includes encounters at physician’s offices, outpatient hospitals, independent clinics, ambulatory surgical centers, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and rural health clinics

Services received at residential and non-residential substance use treatment facilities

Includes inpatient psychiatric facility encounters, partial hospitalizations, and community mental health center encounters

Abbreviations: OUD, opioid use disorder

DISCUSSION

Among Medicaid-enrolled women with OUD in pregnancy, nonwhite/Hispanic women had a lower percentage of MOUD receipt during pregnancy and postpartum relative to non-Hispanic White women. The diagnosis of OUD at a later gestational age during pregnancy among nonwhite/Hispanic women relative to non-Hispanic White women was the primary factor that contributed to racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt during pregnancy. In turn, MOUD receipt during pregnancy was the largest contributor to racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt in the postpartum period. This is the first study to quantify the contributions of individual, healthcare access and quality, and community factors to racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt among Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD.

Prior research in non-pregnant populations indicates that racial-ethnic disparities in substance use disorder treatment are largely explained by factors related to social context and healthcare access and quality rather than an individual’s substance use history and age.22 As such, gaps in the delivery of healthcare services are estimated to contribute 10%-20% to health outcomes.33 Our results are consistent with these findings, as healthcare access and quality and community factors explained larger percentages of the racial-ethnic disparities in MOUD receipt during pregnancy and the postpartum period relative to individual factors. However, the factors evaluated in this analysis failed to explain most of the racial-ethnic disparity in MOUD during pregnancy. One unobserved factor may be a lack of substance use disclosure during pregnancy due to policies that criminalize substance use behavior and lead to loss of child custody, which disproportionately affect nonwhite/Hispanic women.34

Among observed factors, the racial-ethnic gap in MOUD receipt during pregnancy was largely explained by the timing of the diagnosis of OUD during pregnancy. On average, non-Hispanic White women were diagnosed 37 days earlier in pregnancy relative to nonwhite/Hispanic women, despite guidelines recommending universal screening for substance use when women first present for care during pregnancy. Notably, we found that nonwhite/Hispanic women report the same or a higher median number of healthcare visits than non-Hispanic White women prior to OUD diagnosis in pregnancy, which indicates that there are provider and system-level “missed opportunities” to screen for and identify OUD among nonwhite/Hispanic women who are presenting for healthcare services. Racial discrimination by clinicians may also contribute to lower initiation or adherence of MOUD receipt among nonwhite/Hispanic individuals during pregnancy or postpartum.35 Failure to identify OUD during pregnancy negates a critical window of opportunity for MOUD initiation and treatment engagement due to expanded insurance eligibility and more frequent healthcare interactions.

Our findings also suggest that if nonwhite/Hispanic pregnant women received MOUD during pregnancy at the same rate as that of non-Hispanic White women, this would substantially close the racial-ethnic gap in postpartum MOUD receipt. Other factors included in this decomposition model contributed significantly less than this factor (approximately −12%). This underscores the importance of screening and initiating MOUD during pregnancy for Medicaid-enrolled women to facilitate treatment engagement after delivery. These findings support ongoing quality improvement efforts by the Pennsylvania Perinatal Quality Collaborative (PA PQC), including data collection and reporting of SUD screening rates in pregnancy using a validated screening tool.36

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, decomposition analysis is sensitive to unobserved factors that might further explain the observed racial-ethnic gap, such as cultural norms, provider attitudes, or stigma. We used previous research7,9,16-18,20-24 to identify the primary explanatory factors in the models that would be relevant to this population. Second, our findings may not be generalizable to higher income women who are privately insured or have other types of insurance and to pregnant women in other states. However, Pennsylvania Medicaid is the fourth largest program in the U.S., with similar demographics to national averages and serves as the largest payer for pregnancy and births.26,37 Third, comorbidities, including HCV or other substance use disorders, may not have been identified in many individuals, which could result in underestimation or misclassification of these conditions. Racial-ethnic disparities in these conditions (Table 1) suggest this misclassification would differ by racial-ethnic category. However, the main exposure of racial-ethnic category and the outcomes, MOUD receipt during pregnancy and postpartum, are unlikely to be affected by this potential misclassification. Fourth, access to buprenorphine or methadone treatment programs may differ by race and ethnicity, as there are more programs in urban vs. rural areas. 38 Data on an individual’s access to treatment was unavailable in our dataset. While we do not explicitly include these access measures in the decomposition model, we account for these potential geographic differences in MOUD receipt by including a county-level indicator for urban or rural categorization based on population density.

CONCLUSION

Nonwhite/Hispanic women are less likely to receive MOUD during pregnancy and postpartum compared with non-Hispanic White women, partly because they are diagnosed with OUD later in pregnancy despite similar patterns of healthcare utilization between the two racial-ethnic groups. While findings support the implementation of universal screening protocols for substance use early in pregnancy, further interventions are needed to ensure that patients with OUD are connected with evidence-based and culturally competent care. Given the health benefits of MOUD in pregnancy and the postpartum period, reducing this disparity in MOUD receipt is an important step to achieve equity in health outcomes for pregnant and postpartum women with OUD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Award Number R01DA045675 (Krans and Jarlenski). This research was also supported by an inter-governmental agreement between the University of Pittsburgh and the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

Dr. Krans is an investigator on grants to Magee-Womens Research Institute from the National Institutes of Health, Gilead and Merck

Contributor Information

Yitong (Alice) Gao, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Coleman Drake, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Elizabeth E. Krans, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences, Magee-Womens Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Qingwen Chen, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Marian P. Jarlenski, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000-2009. Jama. 2012;307(18):1934–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Short VL, Hand DJ, MacAfee L, Abatemarco DJ, Terplan M. Trends and disparities in receipt of pharmacotherapy among pregnant women in publically funded treatment programs for opioid use disorder in the United States. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2018;89:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter LC, Read MA, Read L, Nicholas JS, Schmidt E. Opioid use disorder during pregnancy: An overview. Journal of the American Academy of PAs. 2019;32(3):20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(22):2063–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comer S, Cunningham C, Fishman MJ, et al. National practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. Am Soc Addicit Med. 2015;66 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaman SL, Isaacs K, Leopold A, et al. Treating women who are pregnant and parenting for opioid use disorder and the concurrent care of their infants and children: literature review to support national guidance. Journal of addiction medicine. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krans EE, Kim JY, James III AE, Kelley D, Jarlenski MP. Medication-Assisted Treatment Utilization Among Pregnant Women With Opioid Use Disorder. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019;133(5):943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo-Ciganic WH, Donohue JM, Kim JY, et al. Adherence trajectories of buprenorphine therapy among pregnant women in a large state Medicaid program in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2019;28(1):80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Hoeppner BB, et al. Assessment of racial and ethnic disparities in the use of medication to treat opioid use disorder among pregnant women in Massachusetts. JAMA network open. 2020;3(5):e205734–e205734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiff DM, Nielsen TC, Hoeppner BB, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine discontinuation among postpartum women with opioid use disorder. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal EW, Short VL, Cruz Y, et al. Racial inequity in methadone dose at delivery in pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2021;131:108454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR, Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health care financing review. 2000;21(4):75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen H, Braslow J, Rohrbaugh RM. From cultural to structural competency—training psychiatry residents to act on social determinants of health and institutional racism. JAMA psychiatry. 2018;75(2):117–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarlenski MP, Paul NC, Krans EE. Polysubstance Use Among Pregnant Women With Opioid Use Disorder in the United States, 2007–2016. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2020;136(3):556–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hand DJ, Short VL, Abatemarco DJ. Substance use, treatment, and demographic characteristics of pregnant women entering treatment for opioid use disorder differ by United States census region. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2017;76:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarlenski M, Barry CL, Gollust S, Graves AJ, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Kozhimannil K. Polysubstance use among US women of reproductive age who use opioids for nonmedical reasons. American journal of public health. 2017;107(8):1308–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keegan J, Parva M, Finnegan M, Gerson A, Belden M. Addiction in pregnancy. Journal of addictive diseases. 2010;29(2):175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krans EE, Cochran G, Bogen DL. Caring for opioid dependent pregnant women: prenatal and postpartum care considerations. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;58(2):370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP. Healthy People 2030. Accessed December 2, 2021, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nam E, Matejkowski J, Lee S. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Contemporaneous Use of Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment Among Individuals Experiencing Both Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2017/March/01 2017;88(1):185–198. doi: 10.1007/s11126-016-9444-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Center for Substance Abuse T. SAMHSA/CSAT Treatment Improvement Protocols. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saloner B, Cook BL. Blacks and Hispanics are less likely than whites to complete addiction treatment, largely due to socioeconomic factors. Health affairs. 2013;32(1):135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, Keefe K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. Journal of the american academy of Child & adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Fingerhood MI, Saloner B. Racial and ethnic differences in opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder in a US national sample. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017;178:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services OoDPaHP. Area Health Resources File (AHRF). Accessed May 20, 2019. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bureau USC. QuickFacts Pennsylvania 2019. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/42 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pennsylvania TCfR. Rural Urban Definitions. Accessed May 20, 2019. https://www.rural.palegislature.us/demographics_rural_urban.html [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairlie RW. An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. Journal of economic and social measurement. 2005;30(4):305–316. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahimi E, Hashemi Nazari SS. A detailed explanation and graphical representation of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition method with its application in health inequalities. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2021/August/06 2021;18(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12982-021-00100-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwiebert J A detailed decomposition for nonlinear econometric models. The Journal of Economic Inequality. 2015/March/01 2015;13(1):53–67. doi: 10.1007/s10888-014-9291-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairlie RW. Race and the Digital Divide. Contributions in Economic Analysis & Policy. 2004;3(1):1–38. doi:doi: 10.2202/1538-0645.1263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jann B Fairlie: Stata module to generate nonlinear decomposition of binary outcome differentials. 2006; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. American journal of preventive medicine. 2016;50(2):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders JB, Jarlenski MP, Levy R, Kozhimannil KB. Federal and state policy efforts to address maternal opioid misuse: gaps and challenges. Women's health issues. 2018;28(2):130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiff DM, Stoltman JJ, Nielsen TC, et al. Assessing stigma towards substance use in pregnancy: a randomized study testing the impact of stigmatizing language and type of opioid use on attitudes toward mothers with opioid use disorder. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collaborative PPQ. Pennsylvania Perinatal Quality Collaborative. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://whamglobal.org/papqc-docs/pa-pqc-homepage/385-pa-pqc-2021-initiatives-presentation/file [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton BP, Krans EE, Kim JY, Jarlenski M. The impact of Medicaid expansion on postpartum health care utilization among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Substance abuse. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein BD, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Where Is Buprenorphine Dispensed to Treat Opioid Use Disorders? The Role of Private Offices, Opioid Treatment Programs, and Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities in Urban and Rural Counties. Milbank Q. Sep 2015;93(3):561–83. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.