Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) incidence and mortality is increasing in the United States.1 In spite of implementing screening and surveillance programs for the precursor lesion Barrett’s esophagus and greater recognition of this highly lethal cancer, most patients present with late-stage disease associated with a poor prognosis.

Although EAC typically affects older adults, recent data suggest EAC in young adults (younger than 50 years) presents at advanced stages and is associated with poorer survival compared with in older adults.2 These results raise the possibility of a distinct and more aggressive phenotype, which can mirror a well-described phenomenon observed in early-onset colorectal cancer. Using 2 large US cancer registries, we evaluated temporal trends in EAC incidence, and compared overall survival (OS) and stage-specific survival, by age. We hypothesized that incidence rates of EAC in young adults have increased during the past 2 decades, and that young adults would have worse OS and stage-specific survival compared with older age groups.

Methods

We used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to identify adults with EAC: young age (YA, age <50 years), middle age (MA, age 50–69 years), and older age (OA, age ≥ 70 years) (see Supplementary Methods for details). To examine temporal trends, we used SEER to estimate incidence rates (cases per 100,000) during approximate 3-year time periods (2000–2002, 2003–2005 … 2015–2017), overall and for each age group. Our primary outcome was a rate ratio (RR) quantifying relative change over time (2000–2002 vs 2015–2017). Using NCDB, we then compared OS and stage-specific survival by age during the period 2004–2016.

Results

Incidence Rates of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

From 2000–2002 to 2015–2017, incidence of EAC across all age groups increased from 2.9 to 3.3 per 100,000 (RR, 1.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–1.15) (Supplementary Figure 1). Incidence rates increased similarly in OA (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.09–1.22) and MA (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02–1.14); however, rates in YA did not increase over time (RR, 0.99; 95% CI 0.86–1.14).

Overall Survival: National Cancer Database

We identified 114,123 patients diagnosed with EAC (83% male, 86% White, 9% YA) in NCDB (Supplementary Table 1). Most patients were diagnosed at a late stage (53.6% stage III/IV). A higher proportion of YA were diagnosed with stage IV disease and a lower proportion with stage I compared with MA/OA (P < .01). Median survival was highest for YA (15.2 months) followed by MA (15.1 months), and was lowest for OA (10.4 months) (P < .01). In adjusted analyses, YA was associated with improved OS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92–0.96) and OA was associated with worse survival (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.21–1.26) compared with MA.

Predictors of Survival

Hispanic race/ethnicity predicted better survival (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91–0.96) and non-Hispanic Black patients had worse survival (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03–1.11) compared with non-Hispanic White patients. Treatment with surgery (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.49–0.51) or chemotherapy (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.56–0.58) was associated with improved survival, and radiotherapy was associated with worse survival (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05–1.09). Other factors associated with worse survival included stage IV (vs stage I: HR, 5.68; 95% CI, 5.52–5.84), poorly differentiated (vs well-differentiated: HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.62–1.75), and comorbidity score 3+ (vs 0: HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.43–1.56).

Stage-Specific Survival: National Cancer Database

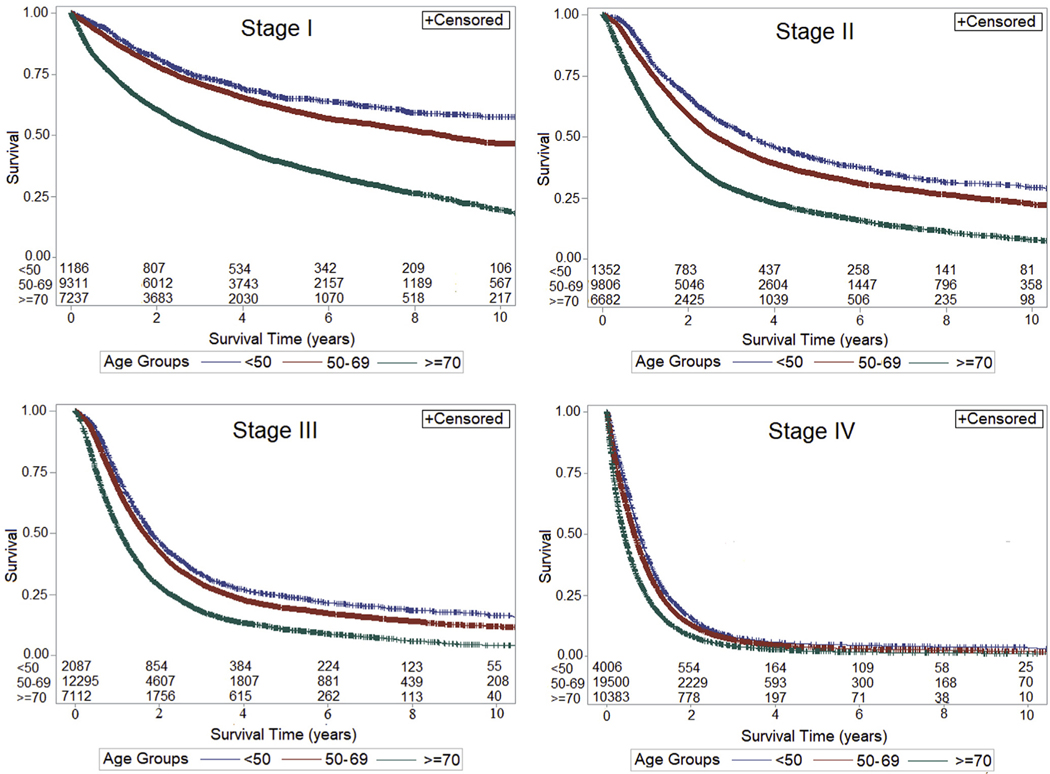

Stage-specific survival was greater for YA compared with MA and OA for all stages (P < .01 for all but stage III) (Figure 1). In adjusted analyses stratified by stage, YA had better, and OA had worse, survival compared with MA for stage III (YA: HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90–1.00; OA: HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.14–1.22) and stage IV (YA: HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90–0.97; OA: 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05–1.11). Differences in survival by age were more pronounced for stage I (YA: HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.80–0.98; OA: HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.49–1.65) and stage II (YA: HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82–0.95; OA: 1.25; 95% CI, 1.20–1.30).

Figure 1.

OS and stage-specific survival of EAC by age, National Cancer Database, 2004–2016. *Log rank for each stage, P < .0001.

When accounting for the interaction between EAC stage and treatment, the differences in survival by age remained similar to results from the primary analysis. After adjusting for this interaction, receipt of chemotherapy switched from a protective to a harmful effect (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.66–1.82) and radiation became a stronger negative predictor of survival (HR, 3.39; 95% CI, 3.23–3.55). The protective effect of surgery stayed the same (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.50–0.55).

Discussion

Our analysis of population-based cancer registry data found that the rising incidence of EAC in the United States is driven largely by older adults. EAC in young adults accounts for only 9% of all cases, and in contrast to increases in early-onset colorectal cancer in Western countries, our results showing stable rates of EAC in YA during the past 2 decades are reassuring. Although it is possible that the downstream effect of Barrett’s esophagus in younger adults3 has not yet been realized, at the present time, these findings do not point to a similar phenomenon in early-onset colorectal cancer.

A higher proportion of YA had advanced disease compared with other age groups, which might be explained by several factors, such as delays in diagnosis. In spite of having more advanced disease, we observed better OS and stage-specific survival among YA compared with MA and OA. These findings contrast smaller studies2 suggesting YA have more aggressive EAC that contributes to worse prognosis.4,5 Our study found that poor survival continues to be associated with histologic grade, comorbidity score, and stage.

In conclusion, increasing incidence rates of EAC are predominantly driven by rates in older adults. OS continues to be poor as most cases are diagnosed at a late stage. Our findings underscore the importance of improving outcomes related to screening and surveillance programs to detect EAC at an early, curable stage using endoscopic or minimally invasive surgical therapies. A higher proportion of YA present with advanced disease; however, YA demonstrated better OS and stage-specific survival. Future studies should focus on age-related survival differences in EAC and why YA present with more advanced disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following members of the Early Onset Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Study Group: Michael B. Cook, PhD, Charlie Fox, MD, Chloe Friedman, MPH, Martin McCarter, MD, Ravy Vajravelu, MD, MSCE, Christopher H. Lieu, MD, Ana Gleisner, MD, Gary W. Falk, MD, MS, and David A. Katzka, MD.

Funding

This article is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1 TR002535. Jennifer M. Kolb received funding from NIH T32-DK007038. Samuel Han received funding from NIH T32-DK007038. Frank I. Scott received research funding from the NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (K08-DK095951). Caitlin C. Murphy received funding from NIH KL2TR001103. Sachin Wani received funding from the University of Colorado Department of Medicine Outstanding Early Scholars Award. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Results of this study were accepted for presentation at the Digestive Disease Week 2020, Chicago, Illinois.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- CI

confidence interval

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- MA

middle age

- NCDB

National Cancer Database

- OA

old age

- OS

overall survival

- RR

rate ratio

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- YA

young age

Footnotes

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Jennifer M Kolb MD, MS (Conceptualization- Equal; Methodology- Equal; Formal Analysis- Lead; Writing- original draft, review & editing). Samuel Han MD, MS (Conceptualization- Equal; Formal Analysis- equal; Writing- review & editing). Frank I Scott MD, MSCE (Methodology- equal; Writing- review & editing). Caitlin C Murphy PhD, MPH (Methodology- equal; Writing- review & editing). Patrick Hosokawa PhD (Methodology- equal, Formal Analysis-Lead). Sachin Wani (Conceptualization- Lead; Supervision- Lead, Methodology- Equal; Writing- review & editing). Michael B. Cook PhD (Writing- review & editing), Charlie Fox MD (Writing- review & editing), Chloe Friedman MPH (Writing- review & editing), Martin McCarter MD (Writing-review & editing), Ravy Vajravelu MD, MSCE (Methodology- Equal; Writing-review & editing), Christopher H. Lieu MD (Writing- review & editing), Ana Gleisner MD (Writing- review & editing), Gary W. Falk MD, MS (Writing-review & editing), David A. Katzka MD (Conceptualization- Equal; Writing-review & editing).

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.002.

References

- 1.Rubenstein JH, et al. Gastroenterology 2015;149:302–317 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawas T, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17:1756–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamasaki T, et al. Esophagus 2020;17:190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boys JA, et al. Am Surg 2015;81:974–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nistelrooij AM, et al. J Surg Oncol 2014;109:561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.