Abstract

Purpose

This retrospective cohort study evaluated real-world data on relapses in adult patients with schizophrenia who transitioned to long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months (PP3M) following treatment with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M).

Patients and Methods

Data derived from the IBM® MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database were analyzed. Adults aged ≥18 years with ≥1 schizophrenia diagnosis claim and ≥12 months of continuous medical and prescription enrollment before and/or at index date of PP3M were eligible for inclusion. Patients were matched on propensity score to 2 PP3M cohorts: (1) adequately treated (AT), defined as patients treated with PP1M for ≥4 months, with the last 2 doses the same and a PP3M initiation dose meeting the corresponding PP1M-to-PP3M dose conversion, or (2) not adequately treated (NAT), defined as patients who received ≤2 or no PP1M doses. Relapse rates and time to relapse distributions based on the first occurrence of a qualifying event during the 2-year follow-up period were compared between PP3M cohorts using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log rank test statistics. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models. Two sensitivity analyses using different matched populations were performed to assess the robustness of the primary findings.

Results

Propensity score matching yielded a sample of 1314 patients (657 per group). Most patients were male (68.9%) and aged 25–64 years (90.1%). The relapse rate was significantly lower in the AT (18.4%) versus NAT cohort (26.8%), P = 0.0002. Risk of relapse decreased by 35% for AT versus NAT (HR: 0.65 [95% CI: 0.51–0.81]). Relapse reductions favored the AT cohort in both sensitivity analyses (HR: 0.67 [95% CI: 0.54–0.83] and HR: 0.74 [95% CI: 0.56–0.97]).

Conclusion

In this analysis of Medicaid claims data, patients adequately treated with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M demonstrated significantly lower relapse rates and delayed time to relapse.

Keywords: paliperidone palmitate, schizophrenia, real-world, relapse, long-acting injectable antipsychotic

Plain Language Summary

Paliperidone palmitate once-monthly (PP1M) and paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months (PP3M) are medicines given by injection to treat adults with schizophrenia. PP3M is used in people who have been adequately treated (their symptoms stabilized when taking the medicine) with PP1M for four or more months and who were taking the same dose of PP1M during the two months before transitioning medicines to PP3M. We wanted to study how many people with schizophrenia have a relapse and the time it takes to have a relapse when transitioned from PP1M to PP3M. The researchers compared people who were either adequately treated (AT) or not adequately treated (NAT) with PP1M before transitioning from PP1M to PP3M. People in the AT group were those who received four or more months of treatment with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M. People in the NAT group were those who received zero to two PP1M doses before starting PP3M. Over a two-year time period, the study showed that people who received four or more months of treatment with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M experienced fewer relapses than people who received less than two months of treatment with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M. These findings provide information for doctors that may aid in their decision-making if they treat people with schizophrenia who transition from PP1M to PP3M.

Introduction

Multiple therapeutic options are available to treat patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, including oral antipsychotics (OAPs) and long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs). Treatment with LAIs early in the course of illness, offering LAIs to patients who prefer injectable treatment options, and offering LAIs to patients who have a history of poor or uncertain adherence to OAPs is recommended to prevent nonadherence and negative outcomes.1–3 Paliperidone palmitate (PP) is an LAI that has been shown to be effective in maintaining symptom control, reducing the risk of relapse, and delaying time to relapse in schizophrenia.4–6 Transitioning patients between the 3 available extended-duration LAI formulations of PP, once-monthly (PP1M),7 once-every-3-months (PP3M),8 and the recently approved once-every-6-months formulation (PP6M),9 by following the label or product insert supports favorable patient outcomes.

Recent evidence highlights the potential benefits of transitioning from PP1M to PP3M, including improved adherence and persistence,10,11 a lower likelihood of hospitalization,11 and patient-provider preference for the 3-month formulation.12,13 Optimization of the PP1M dose prior to transitioning to PP3M is essential to prevent relapse or adverse events that may result from doses that are too low or too high, respectively.14 Because of the long-acting nature of PP3M, it may be difficult to adjust the dose after initiating treatment because changes in plasma concentration will not be fully evident for several months (compared with days or weeks for OAPs).15,16

Following the recommended prescribing information dosing plays a critical role in providing guidance to ensure the safe and appropriate administration of a therapeutic agent. The PP3M label advises that patients should be adequately treated with PP1M for ≥4 months before transitioning to PP3M, with the same dose of PP1M administered in the last 2 consecutive months.8 Adequate treatment with PP1M should be determined by stability of the dose and clinical symptoms before transitioning to PP3M. Instability of the dose could indicate progression of disease, a drug–drug interaction, inadequate efficacy, or tolerability problems. Clinical symptoms should also be assessed. Although not all symptomatic changes would require a dose change, emergence of a new symptom or progression of a previously stable symptom might require more investigation before transitioning a patient to PP3M. Finally, a careful examination and review of side effects should be completed to identify potential safety and tolerability issues before transitioning.

A recent post hoc analysis of a Phase 3 placebo-controlled trial of PP3M (NCT01529515) demonstrated that adequate, label-consistent stabilization with PP1M prior to transitioning to PP3M is crucial for optimizing treatment response.14 In the trial, only patients who continuously met Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)-based stabilization criteria before and 12 weeks after transition from PP1M to PP3M were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment, creating a proxy for the evaluation of “adequate treatment” (randomly assigned patients) versus “not adequate treatment” (nonrandomly assigned patients) with PP1M in the post hoc analysis. The results of the analysis demonstrated that adequately treated (AT) patients were more stable with respect to symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and overall clinical condition compared with not adequately treated (NAT) patients at all time points evaluated in a clinical trial setting where 1 of the objectives was to administer PP3M as indicated by the label. In clinical practice, clinicians adopt more varied prescribing patterns in the treatment of a more heterogeneous population of patients compared with randomized clinical trials.

Real-world data to inform clinical decision-making on the transition from PP1M to PP3M are limited. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate real-world data on relapses in adult patients with schizophrenia who transitioned to PP3M following AT versus NAT with PP1M. We focused on claims data from Medicaid, the largest payer in the United States for mental health services related to schizophrenia,8,17 for the present analysis.

Methods

Data Source

This retrospective cohort study utilized data derived from the IBM® MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database (IBM MDCD), a United States health claims database, from June 2015 to December 2020 (the study period). The IBM MDCD includes healthcare coverage eligibility and service use of individuals enrolled in State Medicaid programs and/or Medicaid managed care programs. The IBM MDCD contains records pertaining to enrollment (eg, medical and prescription records of enrollment including patient demographics and plan type), inpatient and outpatient services, long-term care (ie, medical and pharmacy claims), and financial information for more than 10 million Medicaid enrollees from approximately 10 states. The New England Institutional Review Board reviewed and determined the use of the IBM MDCD to be exempt from review board approval, as this study does not involve human subject research. All data were de-identified and fully complied with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations.

Patient Eligibility

Adults aged ≥18 years with ≥1 claim with a schizophrenia diagnosis before and/or at index date (ie, the first PP3M prescription record) were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Eligible patients also had ≥12 months of continuous medical and prescription enrollment before and after the PP3M index date. If a patient had enrollment periods with dual eligibility (ie, Medicaid and Medicare), these periods were excluded from the study. Patients with a dementia and/or autism diagnosis prior to the index PP3M injection or clozapine use during the baseline period were excluded from the analysis. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) procedure codes used for the assessment of outcomes (eg, hospitalization) are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. ICD diagnosis and procedure codes are poor proxies for complex conditions including, but not limited, to homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior, or hostility when access to data points from validated scales is not available.18

Propensity Score Matching

Patients were matched on propensity score to 2 primary PP3M patient cohorts: (1) AT, defined as patients treated with PP1M for ≥4 months (≥5 injections), of which the last 2 doses were the same and the PP3M initiation dose met the corresponding dose conversion from PP1M to PP3M, or (2) NAT, defined as patients who received ≤2 or no PP1M doses. To create the propensity score match, the eligible PP3M-treated population was stratified by lead-in PP1M injection categories (prior to the index PP3M injection): 0–2 injections, 3 or 4 injections, and ≥5 injections. Patients who received 0–2 injections or ≥5 injections were included in the analysis; the 3- or 4-injection patient stratum was excluded due to the small cohort size and to enable clear delineation of NAT and AT in analyses of relapse. In the ≥5 injection category, the last 2 PP1M dosages were required to be the same. The propensity score model included covariates that have been shown to affect both treatment assignment and outcome as predictors.19,20 Propensity scores were calculated using the following factors: PP3M dose, age category, sex, race, presence of baseline depressive disorder and/or mania/bipolar disorder diagnosis, baseline mental health hospitalization and emergency room (ER) visits, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score. Factors were chosen based on previous clinical findings that supported their relevance.19 Comorbidity scores were defined from ICD codes using the methods outlined in Quan et al.21 Patients were matched 1:1 using the nearest neighbor matching algorithm with a caliper set at 0.2 standard deviations and without replacement such that index PP3M dose, age category, and sex were an exact match. The quality of matching was assessed using the absolute standardized mean difference (ASMD) for each baseline factor. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were summarized with descriptive statistics for the AT and NAT cohorts before and after propensity score matching.

Relapse Analysis

First relapse was determined to have occurred if a patient had a claims record for any of the following during the 2-year follow-up period: mental health–related inpatient hospitalization, suicide attempt/self-inflicted harm/injury (undetermined intent), homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior, hostility, or incarceration. The events included in the definition of relapse represent poor real-world treatment outcomes with high public health impact that remain common with standard treatment approaches. The definition is also consistent with prior analyses. According to a systematic literature review of the definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia, hospitalization was the most frequently used factor in defining relapse.19 Time to first relapse distributions based on the first occurrence of any of the criteria listed above during the follow-up period were described using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, and reasons for relapses were summarized. Cohort differences in time to relapse were examined first using Log rank test statistics. Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated using Cox proportional hazards models.

Sensitivity Analyses

Two sensitivity analyses using different patient populations were carried out to assess the robustness of the main analysis. The first sensitivity analysis included patients with ≥6 months of follow-up data to observe patients with earlier relapses who were then lost to follow-up. The second sensitivity analysis included patients with ≥24 months of follow-up data to observe patients with longer follow-up time and treatment duration.

Results

Patient Selection

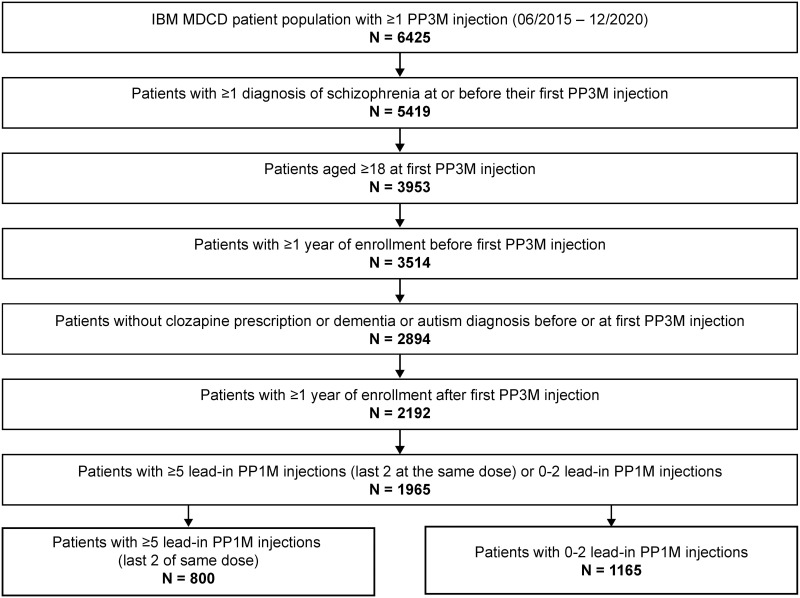

The patient selection flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. The subsequent propensity score matching resulted in a final sample of 1314 patients, with 657 patients in the AT group and 657 patients in the NAT group.

Figure 1.

IBM MDCD patient selection flow diagram.

Abbreviations: IBM MDCD, IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; PP3M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months.

Baseline Demographic and Disease Characteristics

The pre- and post-matching baseline demographics and disease state characteristics are reported in Table 1. After matching, the largest AMSD among the baseline characteristics was 0.066, indicating excellently matched cohorts. Post matching, most patients were male (68.9%) and aged 25–64 years (90.1%); cardiometabolic conditions, substance abuse, and depression were the most commonly documented comorbidities.

Table 1.

Baselinea Demographics and Disease State Characteristics for NAT and AT Cohorts Before and After Matching

| Propensity Score Matching Characteristics, n (%)b | Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAT Cohort | AT Cohort N = 800 | NAT Cohort | AT Cohort N = 657 | ||||

| N = 1165 | N = 657 | ||||||

| Age | ASMD 0.045 | ASMD 0.02 | |||||

| Mean (SD), years | 38.5 (11.93) | 38.0 (11.89) | 37.9 (11.48) | 38.2 (11.49) | |||

| Age category | ASMD 0.114 | ASMD 0.0 | |||||

| 18–24 years | 124 (10.6) | 95 (11.9) | 64 (9.7) | 64 (9.7) | |||

| 25–44 years | 683 (58.6) | 459 (57.4) | 394 (60.0) | 394 (60.0) | |||

| 45–64 years | 348 (29.9) | 242 (30.2) | 198 (30.1) | 198 (30.1) | |||

| 65+ years | 10 (0.9) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Sex | ASMD 0.099 | ASMD 0.0 | |||||

| Male | 742 (63.7) | 547 (68.4) | 453 (68.9) | 453 (68.9) | |||

| Female | 423 (36.3) | 253 (31.6) | 204 (31.1) | 204 (31.1) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ASMD 0.162 | ASMD 0.066 | |||||

| Black | 473 (40.6) | 370 (46.3) | 292 (44.4) | 307 (46.7) | |||

| White | 438 (37.6) | 269 (33.6) | 227 (34.6) | 220 (33.5) | |||

| Mixed/unknown | 144 (12.4) | 109 (13.6) | 88 (13.4) | 89 (13.5) | |||

| Other | 92 (7.9) | 40 (5.0) | 38 (5.8) | 32 (4.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 18 (1.5) | 12 (1.5) | 12 (1.8) | 9 (1.4) | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | ASMD 0.158 | ASMD 0.006 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.50) | 0.7 (1.25) | 0.6 (1.18) | 0.6 (1.21) | |||

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score | ASMD 0.234 | ASMD 0.001 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (2.41) | 3.1 (2.11) | 3.0 (2.13) | 3.0 (2.03) | |||

| Mania/bipolar diagnosis at baseline | ASMD 0.187 | ASMD 0.057 | |||||

| Yes | 387 (33.2) | 198 (24.8) | 170 (25.9) | 154 (23.4) | |||

| Depressive disorder diagnosis at baseline | ASMD 0.164 | ASMD 0.007 | |||||

| Yes | 368 (31.6) | 194 (24.3) | 151 (23.0) | 153 (23.3) | |||

| PP3M dose | ASMD 0.368 | ASMD 0.0 | |||||

| 273 mg | 46 (3.9) | 10 (1.3) | 8 (1.2) | 8 (1.2) | |||

| 410 mg | 122 (10.5) | 148 (18.5) | 83 (12.6) | 83 (12.6) | |||

| 546 mg | 344 (29.5) | 303 (37.9) | 238 (36.2) | 238 (36.2) | |||

| 819 mg | 653 (56.1) | 339 (42.4) | 328 (49.9) | 328 (49.9) | |||

| Inpatient mental health visit | ASMD 0.371 | ASMD 0.009 | |||||

| Yes | 345 (29.6) | 116 (14.5) | 90 (13.7) | 92 (14.0) | |||

| Mental health ER visit | ASMD 0.267 | ASMD 0.049 | |||||

| Yes | 274 (23.5) | 106 (13.3) | 94 (14.3) | 83 (12.6) | |||

| Additional Characteristics, n (%)b | |||||||

| Antipsychotic use, yes | 1119 (96.1) | 800 (100) | 622 (94.7) | 657 (100) | |||

| Post-index enrollment, days (SD) | 1080 (467.70) | 1101 (474.00) | 671.8 (92.28) | 668.1 (97.26) | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity categories | |||||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 299 (25.6) | 150 (18.7) | 131 (19.9) | 120 (18.2) | |||

| Diabetes without complications | 204 (17.5) | 128 (16.0) | 100 (15.2) | 104 (15.8) | |||

| Diabetes with complications | 65 (5.5) | 27 (3.3) | 23 (3.5) | 23 (3.5) | |||

| Elixhauser Comorbidity categories | |||||||

| Hypertension uncomplicated | 382 (32.7) | 228 (28.5) | 190 (28.9) | 189 (28.7) | |||

| Obesity | 225 (19.3) | 153 (19.1) | 112 (17.0) | 122 (18.5) | |||

| Alcohol abuse | 177 (15.1) | 121 (15.1) | 77 (11.7) | 103 (15.6) | |||

| Drug abuse | 384 (32.9) | 216 (27.0) | 173 (26.3) | 185 (28.1) | |||

| Psychoses | 1136 (97.5) | 772 (96.5) | 636 (96.8) | 636 (96.8) | |||

| Depression | 410 (35.1) | 234 (29.2) | 167 (25.4) | 184 (28.0) | |||

Notes: aData for the baseline period are derived from medical or prescription records within the year before the index PP3M injection.Variables listed in the table are either from index date (eg, age at first PP3M injection, PP3M dose at index) or from the 1-year baseline period (eg, Charlson/Elixhauser comorbidity scores, prescription classes, inpatient and ER visits). bUnless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: ASMD, absolute standardized mean difference; AT, adequately treated; ER, emergency room; NAT, not adequately treated; PP3M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months.

Relapse

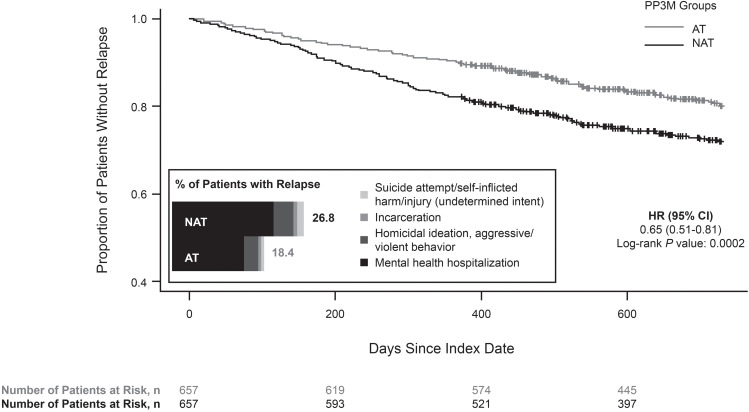

The relapse rate was significantly lower in the AT (18.4%) compared with the NAT cohort (26.8%), P = 0.0002 (Figure 2). The risk of relapse decreased by 35% for AT compared with NAT (HR, 0.65; 95% CI: 0.51–0.81) (Figure 2) Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization was the most common reason for relapse in each group (Figure 2). Reasons for relapse were not mutually exclusive because patients may have experienced more than one qualifying reason for a given relapse.

Figure 2.

Time to first relapse and reasons for relapsea among eligible IBM MDCD patients.

Note: aOne patient in the AT cohort had a relapse described as “incarceration; homicidal ideation”; this patient is included in both the “homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior” and “incarceration” bars.Abbreviations: AT, adequately treated; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NAT, not adequately treated; PP3M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months.

Sensitivity Analyses

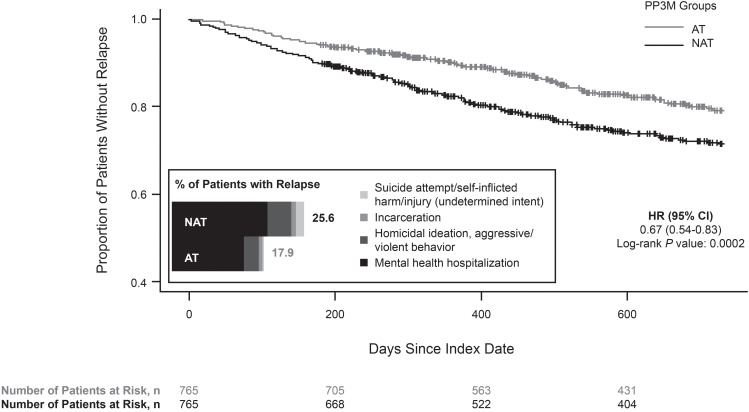

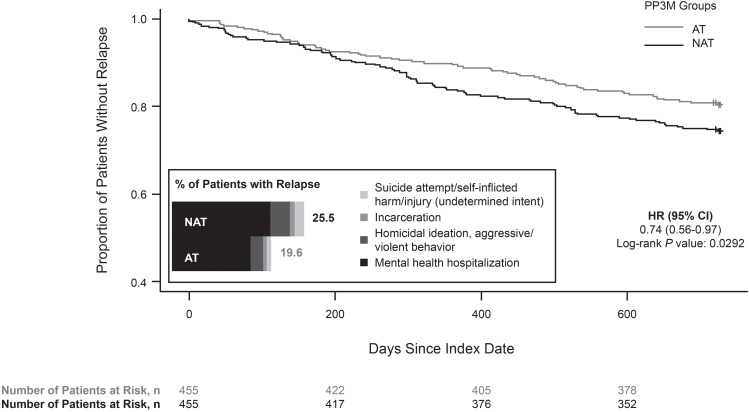

The sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the main analysis. The first sensitivity analysis allowed patients with ≥6 months of follow-up data to be included in the analysis set; these conditions allowed for capture of patients with earlier relapses who were then lost to follow-up. Propensity score matching for the first sensitivity analysis resulted in a final sample of 1530 patients, with 765 patients in each group. The second sensitivity analysis included patients with ≥24 months of follow-up data to capture patients with significant follow-up time. Propensity score matching for the second sensitivity analysis resulted in a final sample of 910 patients, with 455 patients in each group. The pre- and post-matching baseline demographics and disease state characteristics for both sensitivity analyses are reported in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Characteristics were similar to those observed in the primary analysis.

The relapse rates in both analyses were consistent wherein a significantly lower rate was observed in the AT compared with the NAT cohort (P = 0.0002 and P = 0.0292, respectively). In the first sensitivity analysis, risk of relapse was 33% lower in the AT compared with the NAT cohort (HR: 0.67 [95% CI, 0.54–0.83]) (Figure 3). The most common reason for relapse was inpatient psychiatric hospitalization in both AT and NAT groups (Figure 3). In the second sensitivity analysis, risk of relapse was 26% lower in the AT compared with the NAT cohort (HR: 0.74 [95% CI: 0.56–0.97]) (Figure 4). The most common reason for relapse was inpatient psychiatric hospitalization in both the AT and NAT groups (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis of time to first relapse and reasons for relapsea among patients with ≥6 months of follow-up data.

Note: aOne patient in the AT cohort had a relapse described as “incarceration; homicidal ideation”; this patient is included in both the “homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior” and “incarceration” bars. One patient in the NAT cohort had a relapse described as “suicide attempt/self-inflicted harm/injury (undetermined intent); homicidal ideation”; this patient is included in both the “homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior” and “suicide attempt/self-inflicted harm/injury (undetermined intent)” bars. Additionally, one patient in the NAT cohort had a relapse described as “hostility”; this patient was included in the “homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior” bar.Abbreviations: AT, adequately treated; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NAT, not adequately treated; PP3M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of time to first relapse and reasons for relapsea among patients with ≥24 months of follow-up data.

Note: aOne patient in the NAT cohort had a relapse described as “suicide attempt/self-inflicted harm/injury (undetermined intent); homicidal ideation”; this patient is included in both the “homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior” and “suicide attempt/self-inflicted harm/injury (undetermined intent)” bars.Abbreviations: AT, adequately treated; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NAT, not adequately treated; PP3M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-month.

Discussion

In this analysis of Medicaid claims data from real-world patients with schizophrenia, patients who were adequately treated with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M had a significantly lower risk of relapse (35% relative risk reduction) compared with patients who were not adequately treated. In both groups, the most common reason for relapse was mental health hospitalization. The sensitivity analyses confirmed findings of the main analysis, with a significantly lower risk of relapse observed in patients adequately treated with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M who were followed for ≥6 months (33% relative risk reduction) and ≥24 months (26% relative risk reduction) compared with patients who were not adequately treated.

In a key clinical study of PP3M, decisions regarding transition from PP1M to PP3M were required to occur within a fixed protocol-defined timeframe, resulting in the recommendation that patients be treated for ≥4 months with PP1M before switching to PP3M.4 The findings of this real-world analysis reinforce the recommendations of the PP3M product labeling, which stipulates that PP3M should be initiated after adequate treatment with PP1M for ≥4 months in adult patients with schizophrenia. The effects of >4 months of treatment with PP1M before initiation of PP3M on post-transition outcomes have not been systematically evaluated in real-world settings.

Results from this analysis align with a post hoc assessment of a phase 3 study determining the efficacy of PP3M for the treatment of schizophrenia.14 The post hoc analysis showed that adequate stabilization with PP1M prior to transitioning to PP3M is crucial for optimizing treatment response. In the phase 3 study, only patients who met stabilization criteria at 17 weeks after beginning open-label treatment with PP1M and at 12 weeks after the first dose of PP3M (week 29) were randomized to double-blind treatment with PP3M or placebo. This created a proxy for investigating the effects of adequate treatment (randomized) and inadequate treatment (nonrandomized) with PP1M prior to transition to PP3M in the post hoc analysis. In the analysis, improvements in symptoms (PANSS), functioning (Personal and Social Performance scale), and overall condition (Clinical Global Impressions-Severity scale) were observed in both groups during the 17-week open-label phase (PP1M treatment), although improvements were significantly greater in the AT group at all time points. Importantly, these improvements were maintained through week 29 (end of first cycle of treatment with PP3M) only in patients who were adequately treated/randomly assigned.

Collectively, these 2 analyses of patients treated with PP, 1 of data from patients in a controlled research setting and 1 of data from real-world patients, highlight the importance of adequate treatment with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M. These analyses have implications for thoughtful clinical decision-making. In a recent survey of psychiatrists and their patients with schizophrenia, patients with fewer relapses in the 12-month span prior to the survey experienced better quality of life, higher levels of employment, fewer symptoms, and greater participation in social interactions.22 Therefore, careful consideration of adequate treatment before transition between LAI formulations is important for preserving psychosocial functioning and improving clinical outcomes. As longer-acting LAIs, such as PP6M, become available for use, further investigations will be required to determine if a similar stabilization period may be required for optimal post-transition outcomes. Our findings suggest that prescribers should carefully review each potential candidate for transition to PP6M by examining stability of dose, symptoms, and side effects for adequate treatment.

Medicaid claims databases offer large sample sizes across geographically dispersed populations and are important sources for service utilization data. Patient-level claims files include linked inpatient, outpatient, long-term care, and pharmacy records. Medicaid claims are commonly analyzed in real-world studies of patients with schizophrenia;23 the selection is appropriate because Medicaid is the second largest payer in the United States for mental health services related to schizophrenia.8 The IBM MDCD collects administrative data from 10 states with varying sociodemographic compositions; therefore, the data analyzed in this study are likely representative of the broader US population. However, because the analysis was restricted to patients enrolled in Medicaid, findings may not fully generalize to commercially insured patients. Further, patients with schizophrenia with progressive functional impairment are more likely to fall into the Medicaid pool.

General limitations of claims database studies apply to this analysis and may contribute to the larger population of patients characterized as NAT in the dataset. Claims data are primarily used for billing and reimbursement purposes; therefore, the data may not completely identify all medical conditions and patient outcomes, and may not reflect how physicians follow the prescribing label. Further, administrative diagnostic codes are poor proxies for complex conditions, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, aggressive/violent behavior, or hostility. In addition, the single J-code for medical billing assigned for paliperidone palmitate LAIs may lead to an assumption that a patient was not transitioned between formulations properly. Other contributing factors are missing information, changes in patient healthcare coverage, and varying levels of coding practices among providers that may limit the interpretability of the study results. For example, documentation of dose administration among patients who initiated or maintained treatment while in an inpatient setting may not be comprehensive since some patients may receive their loading doses via a sample program, and hence may not be recorded for billing and reimbursement. In addition, hospital billings do not contain details of medication use during hospital stays. Patients continuing their treatment outside of the traditional healthcare system (long-term care institutions, jail, or prisons) may also result in missing data and can be erroneously interpreted as though a dose was missed. There are also potential gaps in prescriber knowledge in achieving adequate treatment among patients who transition between LAIs of longer duration that may also contribute as a limitation in the analysis. While closely adhering to the prescribing label is best practice, deviations may occur in real-life clinical practice and the frequency of these deviations is not captured in the database. Lastly, the analysis was also restricted to first relapse rather than cumulative relapses, which prevented assessment of annualized relapse rates. However, very few patients experienced more than one relapse during the follow-up period.

Conclusion

In this real-world analysis of claims data, adequate treatment with PP1M before transitioning to PP3M was associated with significantly lower relapse rates and delayed time to relapse among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. This real-world evidence is consistent with the PP3M product labeling and aligns with earlier findings in clinical trial participants, highlighting the importance of adequate initial treatment with PP1M in maximizing patient outcomes of subsequent treatment with PP3M.8 Adequate treatment with PP1M or PP3M is needed before transitioning patients to PP6M for optimal outcomes; however, continuous investigation of how patients are transitioned between formulations using real-world data is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Audrey Shor, PhD (Yardley, PA), Susanna Bae, PharmD, and Madeline Pfau, PhD, of ApotheCom (New York) for editorial and writing services, which were funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The study sponsor was involved in the design and conduct of the study and the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors made significant contributions to the development of the manuscript in accordance with ICMJE authorship criteria. Authors provided direction and comments on the manuscript, reviewed, and approved the final version prior to submission, made the final decision about where to publish these data, and approved submission to this journal. All authors had full access to the study data and take responsibility for data integrity and the accuracy of the analyses.

Abbreviations

ASMD, absolute standardized mean difference; AT, adequately treated; CI, confidence interval; ER, emergency room; HR, hazard ratio; IBM MDCD, IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotic; NAT, not adequately treated; OAP, oral antipsychotic; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PP, paliperidone palmitate; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; PP3M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-3-months; PP6M, paliperidone palmitate once-every-6-months.

Data-Sharing Statement

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Ethics Approval

The New England Institutional Review Board reviewed and determined the use of the IBM MDCD to be exempt from review board approval, as this study does not involve human subject research. All data were de-identified and fully complied with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations.

Disclosure

Ibrahim Turkoz and Mehmet Daskiran are employees of Janssen Research and Development, LLC, and hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. Dean Najarian, Oliver Lopena, Camilo Obando, Alexander Keenan, and Carmela Benson are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. H. Lynn Starr and Srihari Gopal were employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and Janssen Research and Development, LLC, respectively, at the time the study was conducted and hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.National Council for Behavior Health. Long acting medications. national council for behavior health; 2021. Available from: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/topics/long-acting-medications. Accessed January 14, 2021.

- 2.University of South Florida College of Behavioral and Community Sciences. 2019–2020 Florida best practice psychotherapeutic medication guidelines for adults. University of South Florida College of behavioral and community sciences; 2020. Available from: http://www.medicaidmentalhealth.org/_assets/file/Guidelines/2019%20Psychotherapeutic%20Medication%20Guidelines%20for%20Adults%20with%20References_06-04-20.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). 5th ed. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savitz AJ, Xu H, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation for patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, noninferiority study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(7):pyw018. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2015;72(8):830–839. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(2–3):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. INVEGA SUSTENNA® (Paliperidone Palmitate) Extended-Release Injectable Suspension, for Intramuscular Use. Titusville, NJ, USA: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. INVEGA TRINZA® (Paliperidone Palmitate) Extended-Release Injectable Suspension, for Intramuscular Use. Titusville, NJ, USA: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. INVEGA HAFYERA® (Paliperidone Palmitate) Extended-Release Injectable Suspension for Intramuscular Use. Titusville, NJ, USA: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edinoff AN, Doppalapudi PK, Orellana C, et al. Paliperidone 3-month injection for treatment of schizophrenia: a narrative review. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12:699748. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.699748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin D, Pilon D, Zhdanava M, et al. Medication adherence, healthcare resource utilization, and costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia treated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate or once-every-three-months paliperidone palmitate. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(4):675–683. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1882412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz EG, Hauber B, Gopal S, et al. Physician and patient benefit-risk preferences from two randomized long-acting injectable antipsychotic trials. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2127–2139. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S114172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathews M, Gopal S, Nuamah I, et al. Clinical relevance of paliperidone palmitate 3-monthly in treating schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1365–1379. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S197225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Donnell A, Rao S, Turkoz I, Gopal S, Kim E. Defining “adequately treated”: a post hoc analysis examining characteristics of patients with schizophrenia successfully transitioned from once-monthly paliperidone palmitate to once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1–9. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S278298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39–59. doi: 10.1007/s40263-020-00779-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopal S, Vermeulen A, Nandy P, et al. Practical guidance for dosing and switching from paliperidone palmitate 1 monthly to 3 monthly formulation in schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(11):2043–2054. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1085849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, Anthony CB, Daumit GL. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(8):830–834. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.8.830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong J, Abrahamowicz M, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R. Assessing the accuracy of using diagnostic codes from administrative data to infer antidepressant treatment indications: a validation study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(10):1101–1111. doi: 10.1002/pds.4436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olivares JM, Sermon J, Hemels M, Schreiner A. Definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alphs L, Nasrallah HA, Bossie CA, et al. Factors associated with relapse in schizophrenia despite adherence to long-acting injectable antipsychotic therapy. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(4):202–209. doi: 10.1097/yic.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin D, Joshi K, Keenan A, et al. Associations between relapses and psychosocial outcomes in patients with schizophrenia in real-world settings in the United States. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:695672. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.695672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li G, Keenan A, Daskiran M, et al. Relapse and treatment adherence in patients with schizophrenia switching from paliperidone palmitate once-monthly to three-monthly formulation: a retrospective health claims database analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:2239–2248. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S322880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]