Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) terminase complex entails a metal-dependent endonuclease at the C-terminus of pUL89 (pUL89-C). We report herein the design, synthesis, and characterization of dihydroxypyrimidine (DHP) acid (14), methyl ester (13), and amide (15) subtypes as inhibitors of pUL89-C. All analogs synthesized were tested in an endonuclease assay, a thermal shift assay (TSA), and subjected to molecular docking to predict binding affinity. Although analogs inhibiting pUL89-C in the sub-μM range were identified from all three subtypes, the acids (14) showed better overall potency, substantially larger thermal shift, and considerably better docking scores than the esters (13) and the amides (15). In the cell-based antiviral assay, six analogs inhibited HCMV with moderate activities (EC50 = 14.4–22.8 μM). The acid subtype (14) showed good in vitro ADME properties, except for poor permeability. Overall, our data support the DHP acid subtype (14) as a valuable scaffold for developing antivirals targeting HCMV pUL89-C.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infects most of the global population. Although the infection is typically inconsequential in healthy adults, congenital1, 2 and perinatal3 HCMV infections cause severe birth defects and pediatric morbidities and mortalities. HCMV infection also poses a major threat to individuals with weakened immunity, including human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) co-infected patients4, 5 and organ transplant recipients.6 Up until recently, direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for treating HCMV infections relied heavily on viral polymerase inhibitors (Figure 1) ganciclovir (GCV, 1),7 cidofovir (CDV, 2),8 and foscarnet (FOS, 3);9 particularly GCV which remains the primary treatment option.10 However, clinical use of these drugs is often limited by dose-related adverse effects and drug resistance.11 Recent HCMV drug discovery efforts driven by the pressing need for novel DAAs with distinct mechanisms of action and improved safety profiles have resulted in the FDA approval of letermovir (LTV) in 201712 and maribavir (MBV) in 2021.13 LTV (4) is a terminase inhibitor14 featuring a dihydroquinazoline chemical core (Figure 1), with key resistance mutations mapped to a component of the terminase complex, UL56.14 MBV (5) is a ribonucleoside analog featuring a benzimidazole base mimic (Figure 1).15 It is an ATP competitive inhibitor of the viral kinase pUL97 which phosphorylates viral and cellular proteins.16

Figure 1.

Structures of FDA-approved DAAs against HCMV. GCV (1), CDV (2) and FOS (3) target viral polymerase; LTV (4) targets pUL56 of the viral terminase complex; and MBV (5) targets viral kinase pUL97.

Our own efforts toward HCMV drug discovery have focused on the viral terminase complex,17 which is required for viral genome packaging, and represents a drug target18 clinically validated by LTV. Particularly, we have been interested in targeting the endonuclease activity provided by the C-terminus of the component protein pUL89 (pUL89-C).19 Toward this end, we have previously identified and characterized a few metal-binding chemotypes as pUL89-C inhibitors (Figure 2): hydroxypyridine carboxylic acid (HPCA, 6),20, 21 6-arylamino-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione (HPD-NH, 7),22 and the 6-arylthio-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione (HPD-S, 8).23

Figure 2.

Previously reported metal-binding inhibitor types of HCMV pUL89-C. The key chelating triads are highlighted in red. All inhibited pUL89-C in an ELISA biochemical assay with IC50 values in the low μM range.

Importantly, pUL89-C has an RNase H-like active site fold, and a metal-dependent catalytic mechanism similar to a few other integrase/RNase H-like viral metalloenzymatic functions24, 25 that we have targeted, including HIV-1 integrase strand transfer (INST),26–28 HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-associated ribonuclease H (RNase H),29–37 hepatitis B virus (HBV) RNase H,38 and hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5B.39, 40 To expand our medicinal chemistry efforts and gain understanding on the pharmacophore of metal-binding inhibitors, we surveyed metal-chelating inhibitor types of the aforementioned viral metalloenzymes. Among these, dihydroxypyrimidine (DHP) has served as a versatile and important scaffold in antiviral drug discovery, as exemplified by raltegravir41 (RAL, 9), the first FDA-approved HIV-1 INST inhibitor (Figure 3A). Key to the development of RAL was the intermediate DHP carboxamide lead 11,42 which was evolved from the prototypical DHP carboxylic acid 10,43 an inhibitor of HCV NS5B. In addition, C-2 modification of 10 generated 1244 as an inhibitor type of HIV-1 RNase H (Figure 3A). Interestingly, each DHP subtype appeared to confer highly specific inhibition against their intended target. For example, carboxamide 11 potently inhibited HIV-1 INST without significantly inhibiting HCV NS5B, whereas carboxylic acid 10 did not inhibit HIV-1 INST while effectively inhibiting HCV NS5B.42 As for ester derivatives, partial NS5B inhibitory activity was observed with the methyl ester of acid subtype 10.43 Similarly, both quinolinone carboxylic acids and ester derivatives were active inhibiting HIV-1 RNase H.45 However, methyl ester of another HIV-1 RNase H inhibitor type, DHP carboxylic acid 12 (Figure 3A), was only marginally active.44 Esterification of the prototypical diketoacid INST inhibitor also led to complete loss of activity.46 These structure-activity relationship (SAR) observations prompted us to synthesize and test three DHP subtypes as inhibitors of HCMV pUL89-C (Figure 3B): methyl carboxylate (13), carboxylic acid (14) and carboxamide (15).

Figure 3.

4,5-Dihydroxypyrimidine (DHP) carboxylic acids and derivatives as a major metal-binding chemotype in antiviral drug discovery. (A) RAL (9), the first FDA-approved HIV-1 INST inhibitor, was evolved from DHP carboxamide 10, which was derived from the prototypical DHP carboxylic acid HCV NS5B inhibitor 11. C-2 modification of 11 identified 12 as an inhibitor type of HIV-1 RNase H. (B) The three DHP subtypes synthesized and tested as inhibitors of HCMV pUL89-C: methyl carboxylate (13), carboxylic acid (14) and carboxamide (15).

Results and Discussion

Chemical synthesis.

The synthesis of the 5-hydroxypyrimidinone core (Scheme 1) began with the addition of hydroxylamine to various carbonitriles (16) to yield the corresponding amidoximes (17). The R1 from the starting material 16 provided the first point of structural diversification. The substituted amidoximes then participated in a Michael addition with dimethylacetylenedicarboxylate to yield intermediates 18, followed by a Claisen rearrangement under microwave radiation to afford the DHP methyl carboxylates (13). The subsequent saponification under LiOH or direct amidation of 13 produced the desired DHP carboxylic acids (14) and DHP carboxamides (15), respectively. During the amidation, the R2 of the amines allowed a second structural diversification. In the end, a total of 57 analogs of three subtypes were synthesized and analytically characterized.

Scheme 1a.

Synthesis of DHP subtypes 13-15.42, 43

a Reagents and conditions: (a) NH2OH, EtOH, 70 °C, 12 h, 70–90%; (b) dimethylacetylenedicarboxylate, MeOH, rt, 12 h, >99%; (c) o-xylene, 150 °C, 40 min, 35–50%; (d) LiOH, dioxane, 70°C, overnight, 55–65%; (e) R2NH2, DMF, 90°C, overnight, 55–65%.

Biological characterization.

Since compounds were designed to inhibit pUL89-C, biological characterization of the 57 synthetic analogs was highly target-centric and based primarily on a biochemical functional assay measuring the endonuclease activity of pUL89-C and a biophysical thermal shift assay (TSA) assessing target binding affinity. The endonuclease biochemical assay was first conducted at 5 μM for each analog to measure the percent inhibition, followed by the dose-response testing for most analogs, from which an IC50 value was calculated. The biophysical TSA was carried out at 20 μM, and the melting point change (ΔTm) of the target protein (pUL89-C) was used to assess binding affinity. In addition, we performed in silico molecular docking analysis under extra precision (XP) for each analog against a reported active site structure (PDB code: 6ey747), and the XP GScore for the energetically most favored pose was reported. Selected analogs were also tested in a dose-response fashion for antiviral potency and cytotoxicity.

All three HPD subtypes strongly inhibited pUL89-C.

In the functional assay measuring the endonuclease activity of pUL89-C, analogs showing significant inhibition at 5 μM were identified from all three subtypes: methyl carboxylates (13), carboxylic acids (14), and carboxamides (15). Of these, 9/19 ester analogs (IC50 = 0.59–5.0 μM), 18/18 acid analogs (IC50 = 0.54–3.8 μM), and 11/20 amide analogs (IC50 = 0.76–5.7 μM) were further evaluated in the dose-response testing, all displaying potency in the sub to low μM range (Table 1). The consistent inhibition of pUL89-C at sub μM range by a total of 13 analogs spanning all three subtypes (ester: 13c, 13d, 13h and 13n; acid: 14c, 12, 14j, 14l, 14p and 14q; amide: 15b, 15l and 15n) represents a significant potency improvement over previously known pUL89-C inhibitors and strongly validates the DHP chemotype as a valuable scaffold for designing pUL89-C inhibitors.

Table 1.

Biochemical inhibition of pUL89-C endonuclease activity by DHP methyl carboxylates (13), carboxylic acids (14) and carboxamides (15).

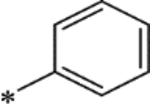

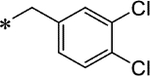

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | R1 | R2 | Inhibition % at 5 μM | IC50 (μM)a |

| 13a | Me | -- | 5.0 | -- |

| 14a | 44 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | ||

| 13b |

|

-- | 58 | 1.1 ± 0.41 |

| 14b | 65 | 4.5 ± 2.6 | ||

| 13c |

|

-- | 100 | 0.86 ± 0.66 |

| 14c | 94 | 0.54 ± 0.34 | ||

| 13d |

|

-- | 75 | 0.88 ± 0.13 |

| 10 | 89 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | ||

| 13e |

|

-- | 57 | -- |

| 14e | 85 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | ||

| 13f |

|

-- | 45 | -- |

| 14f | 58 | 2.7 ± 0.25 | ||

| 13g |

|

-- | 38 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| 13h |

|

-- | 89 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| 14h | 76 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | ||

| 13i | -- | 53 | -- | |

| 12 |

|

37 | 0.62 ± 0.11 | |

| 13j |

|

-- | 30 | -- |

| 14j | 69 | 0.92 ± 0.39 | ||

| 13k |

|

-- | 42 | -- |

| 14k | 73 | 1.3 ± 0.31 | ||

| 13l |

|

-- | 54 | -- |

| 14l | 91 | 0.74 ± 0.17 | ||

| 13m |

|

-- | 53 | -- |

| 14m | 70 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | ||

| 13n |

|

-- | 69 | 0.76 ± 0.24 |

| 14n | 71 | 1.4 ± 0.65 | ||

| 13o |

|

-- | 77 | 5.7 ± 0.85 |

| 14o | 78 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | ||

| 13p |

|

-- | 46 | -- |

| 14p | 77 | 0.87 ± 0.43 | ||

| 13q |

|

-- | 89 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| 14q | 100 | 0.67 ± 0.44 | ||

| 13r |

|

-- | 53 | -- |

| 14r | 61 | 1.7 ± 0.35 | ||

| 13s |

|

-- | 49 | -- |

| 14s | 86 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | ||

| 15a | Me |

|

18 | -- |

| 15b | Me |

|

35 | 0.59 ± 0.29 |

| 15c | Me |

|

30 | -- |

| 15d | Me |

|

35 | -- |

| 15e | Me |

|

38 | -- |

| 15f | Me |

|

35 | -- |

| 15g | Me |

|

34 | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| 15h |

|

|

60 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| 15i |

|

|

7.8 | -- |

| 11 |

|

|

58 | 1.4 ± 0.44 |

| 15j |

|

|

63 | 1.9 ± 1.5 |

| 15k |

|

|

63 | 3.0 ± 0.02 |

| 15l |

|

|

62 | 0.7 ± 0.01 |

| 15m |

|

|

79 | 1.3 ± 0.02 |

| 15n |

|

|

63 | 0.79 ± 0.31 |

| 15o |

|

|

74 | 5.0 ± 1.7 |

| 15p |

|

|

22 | -- |

| 15q |

|

|

34 | -- |

| 15r |

|

|

51 | 1.0 ± 0.18 |

| 15s |

|

|

28 | -- |

| 6 | -- | -- | -- | 4.2 ± 0.37 |

Concentration of a compound inhibiting pUL89-C by 50%, expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least two independent experiments. Previously published inhibitor 6 was used as the control (IC50 = 4.2 ± 0.37 μM).

The biochemical endonuclease assay also revealed a few important structure-activity relationships (SARs). 1) In general, acid analogs (14) inhibited better than ester analogs (13) and amide analogs (15), which is particularly evident by directly comparing the acid-ester pairs in Table 1. Since the carboxylic acid or its functional equivalent (ester or amide) constitutes the third prong of the DHP chelating triad, the difference in observed potency likely reflects the electronic properties required for effectively chelating the active site Mn2+. Against similar enzymes featuring two divalent metal ions at the active site, optimal inhibition of HIV-1 INST appears to strongly prefer carboxamide functionality,42 whereas the carboxylic acid functionality is favored for inhibiting HIV-1 RNase H44 and HCV NS5B.43 Although the ester functionality is typically undesired, analogs of certain chemotypes have been reported to potently inhibit HIV RNase H,45 congruent with the observation herein (Table 1). 2) With all three subtypes, the SAR seems to prefer an aryl or arylmethyl group at R1 over a methyl group (e.g. 13l / 13c vs 13a; 14l / 14c vs 14a; 15r / 15h vs 15c). 3) For the carboxamide subtype (15), the impact of R2 is not substantial when compared to that of R1 (Table 1).

The carboxylic acids (14) bound to pUL89-C with significantly higher affinity than the methyl carboxylates (13) and carboxamides (15).

Direct pUL89-C target binding was assessed with TSA, which measures the change of the target protein melting point upon ligand binding. A positive shift (ΔTm > 0) denotes a stabilizing effect by the ligand and a negative shift (ΔTm < 0) indicates a destabilizing effect. As shown in Table 2, compound 14h was associated with a very large negative shift (ΔTm = −14 °C) which is likely an outlier; and two other analogs, 14q (ΔTm = −0.50 ± 2.8 °C) and 15s (ΔTm = −0.63 ± 0.89 °C) displayed small negative shifts both well within the standard error. All other analogs produced positive shifts in the TSA. Overall, analogs of the carboxylic acid subtype (14) caused substantially larger shifts (ΔTm = 3.4–6.9 °C, Table 2) than the methyl carboxylate subtype (13, ΔTm = 1.2–3.9 °C) and the carboxamide subtype (15, ΔTm = 0.9–4.0 °C), largely consistent with the observed pUL89-C inhibitory potency shown in Table 1. The TSA observations were corroborated by molecular docking (Table 2) where analogs of subtype 14 docked with considerably lower energy than those of subtypes 14 and 15 (Table 2, comparing each pair of 13 vs 14). Collectively, data from Tables 1 and 2 suggest that the acid subtype (14) binds and inhibits pUL89-C better than the ester (13) and amide (15) subtypes.

Table 2.

Biophysical thermal shift assay (TSA) and in silico molecular docking results of DHP methyl carboxylates (13), carboxylic acids (14) and carboxamides (15).

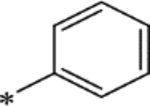

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | R1 | R2 | ΔTm (°C)a | XP GScore (kcal/mol)b |

| 13a | Me | -- | 1.7 ± 0.44 | −3.49 |

| 14a | 4.9 ± 0.43 | −9.21 | ||

| 13b |

|

-- | 3.4 ± 0.43 | −8.57 |

| 14b | 6.2 ± 0.47 | −10.55 | ||

| 13c |

|

-- | 3.7 ± 0.41 | −7.44 |

| 14c | 6.3 ± 0.40 | −10.52 | ||

| 13d |

|

-- | 3.7 ± 0.06 | −8.56 |

| 10 | 6.4 ± 0.64 | −10.74 | ||

| 13e |

|

-- | 3.8 ± 0.05 | −7.48 |

| 14e | 6.9 ± 0.92 | −10.68 | ||

| 13f |

|

-- | 3.6 ± 0.21 | −8.52 |

| 14f | 5.4 ± 0.01 | −9.36 | ||

| 13g |

|

-- | 2.6 ± 0.29 | −8.31 |

| 13h |

|

-- | 3.9 ± 0.32 | −8.88 |

| 14h | −14 ± 12 | −12.04 | ||

| 13i |

|

-- | 2.1 ± 0.49 | −7.52 |

| 12 | 5.9 ± 0.55 | −9.30 | ||

| 13j |

|

-- | 2.0 ± 0.47 | −7.98 |

| 14j | 5.1 ± 1.2 | −9.62 | ||

| 13k |

|

-- | 2.0 ± 0.44 | −10.05 |

| 14k | 6.0 ± 0.47 | −11.08 | ||

| 13l |

|

-- | 2.0 ± 0.4 | −7.40 |

| 14l | 5.1 ± 0.27 | −9.46 | ||

| 13m |

|

-- | 1.9 ± 0.16 | −6.71 |

| 14m | 3.4 ± 0.61 | −9.12 | ||

| 13n |

|

-- | 2.1 ± 0.09 | −7.59 |

| 14n | 3.8 ± 0.03 | −9.36 | ||

| 13o |

|

-- | 3.1 ± 0.09 | −7.53 |

| 14o | 1.6 ± 0.12 | −9.54 | ||

| 13p |

|

-- | 2.2 ± 0.14 | −7.69 |

| 14p | 4.0 ± 0.23 | −9.58 | ||

| 13q |

|

-- | 2.9 ± 0.33 | −7.37 |

| 14q | −0.50 ± 2.8 | −9.65 | ||

| 13r |

|

-- | 2.4 ± 0.10 | −7.73 |

| 14r | 5.3 ± 0.01 | −9.63 | ||

| 13s |

|

-- | 1.2 ± 0.38 | −7.40 |

| 14s | 5.1 ± 0.06 | −9.75 | ||

| 15a | Me |

|

1.7 ± 0.67 | −8.83 |

| 15b | Me |

|

2.5 ± 0.21 | −8.79 |

| 15c | Me |

|

2.3 ± 0.48 | −9.44 |

| 15d | Me |

|

1.6 ± 0.6 | −9.31 |

| 15e | Me |

|

2.5 ± 0.31 | −9.50 |

| 15f | Me |

|

2.1 ± 0.21 | −9.57 |

| 15g | Me |

|

2.6 ± 0.65 | −2.81 |

| 15h |

|

|

2.9 ± 0.32 | −6.55 |

| 15i |

|

|

0.93 ± 0.36 | −9.04 |

| 11 |

|

|

4.0 ± 0.06 | −7.06 |

| 15j |

|

|

3.1 ± 1.0 | −5.03 |

| 15k |

|

|

2.2 ± 0.21 | −7.38 |

| 15l |

|

|

2.8 ± 0.31 | −5.81 |

| 15m |

|

|

2.3 ± 0.01 | −7.08 |

| 15n |

|

|

3.5 ± 0.10 | −7.13 |

| 15o |

|

|

1.9 ± 0.46 | −7.33 |

| 15p |

|

|

0.90 ± 0.09 | −8.15 |

| 15q |

|

|

1.9 ± 0.38 | −8.11 |

| 15r |

|

|

1.1 ± 0.36 | −7.98 |

| 15s |

|

|

−0.63 ± 0.89 | −8.31 |

TSA: thermal shift assay. ΔTm: change of pUL89-C melting point in presence of a compound compared to 0.5% DMSO control. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from four independent biological experiments. RAL (9) was used as a control (ΔTm = 2.6 ± 0.38 °C).

Docking score of a ligand with extra precision (XP) against PDB 6ey7. Shown is the score for the most energetically favored pose. Control docking was performed with RAL (9, XP Gscore = −4.53 kcal/mol).

Analogs from all three subtypes moderately inhibited HCMV in the antiviral assay.

To assess the antiviral potential of these subtypes, we first screened all analogs at 10 μM in a cell-based antiviral assay in human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells using a GFP-expressing reporter virus, ADCREGFP. The HCMV polymerase inhibitor GCV was used as a positive control. These assays identified six analogs with significant (≥35%) HCMV inhibition and no cytotoxicity at 10 μM (data not shown). All six analogs were then further tested in a dose-response fashion. The results are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 4, along with the biochemical inhibitory data. Importantly, all six analogs moderately inhibited HCMV replication in cell culture in the μM range (EC50 = 14.4 –22.8 μM). In addition, the analogs did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 100 μM, with the exception of amide analog 15k (CC50 = 43 μM). Nevertheless, the consistent μM antiviral potencies, as well as the potent biochemical inhibition and confirmed target binding, collectively provide a solid validation for the DHP chemotype as a platform for developing pUL89-C targeting HCMV antivirals.

Table 3.

Dose-response testing of selected analogs in the antiviral and cytotoxicity assays.

| Cpd | Nuclease IC50 (μM) | Cell-based assays | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50a (μM) | CC50b (μM) | SIc | ||

| 13d | 0.88 ± 0.13 | 21.1 ± 1.1 | >100 | >4.7 |

| 10 | 1.2 ± 0.70 | 18.2 ± 6.1 | >100 | >5.5 |

| 13h | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 22.8 ± 0.05 | >100 | >4.4 |

| 13q | 2.1 ± 0.40 | 17.2 ± 0.6 | >100 | >5.8 |

| 14q | 0.64 ± 0.44 | 20.0 ± 2.5 | >100 | >5.0 |

| 15k | 3.0 ± 0.02 | 14.4 ± 4.0 | 43 ± 2.3 | 3.0 |

| 6 | 4.2 ± 0.37 | 4.9 ± 0.5d | >200d | >41 |

| 7 | 2.3 ± 0.58e | 7.9 ± 2.7e | >100e | >13 |

| 8 | 6.2 ± 3.6f | 2.9 ± 2.3f | 21 ± 10f | 7.2 |

| 1 | -- | 1.0 ± 0.24 | > 50 | >54 |

EC50: concentration of compound inhibiting HCMV replication by 50%, expressed as the mean ± SD from samples done in triplicate and at least two independent experiments. Known drug GCV (1) was used as the control (EC50 = 1.0 ± 0.24 μM).

CC50: concentration of compound causing 50% cell death, expressed as the mean ± SD from samples done in triplicate and at least two independent experiments. Previously reported pUL89 inhibitor 6 was used as the control.

SI: selectivity index, defined as CC50 / EC50.

Data taken from previous publication.20

Data taken from previous publication.22

Data taken from previous publication.23

Figure 4.

Dose-response testing of selected analogs. A) Representative dose-response curves of 10, 13d, 13h, 13q, 14q and 15k in the biochemical endonuclease assay. Previous pUL89-C inhibitor 6 was used as a positive control; B) dose-response antiviral testing of 10, 13d, 13h, 13q, 14q and 15k. GCV (1) was used as the control. All doses were analyzed in triplicate and each independent experiment performed at least twice.

In vitro ADME.

To help understand the discrepancy between the biochemical inhibition and the cell-based antiviral potency, we first measured permeability of selected analogs in a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA),48, 49 including two ester analogs (13d and 13q), six acid analogs (14j, 14c, 14h, 14r, 14q and 10) and two amide analogs (15l and 15b). Two acid analogs (10 and 14q), selected based on biochemical and antiviral activities, were further evaluated for aqueous solubility, plasma stability, and microsomal stability. These ADME results are summarized in Table 4. Strikingly, all six acid analogs showed no to marginal permeability in the PAMPA (Pe = 0–0.1 × 10−6 cm/s), whereas the ester and amide analogs displayed moderately low to very high permeability (Pe = 0.9–12.4 × 10−6 cm/s). These observations suggest that i) cellular uptake of the acid analogs via passive diffusion may be completely lacking, which could account for the potency difference in vitro vs in cellulo; and ii) ester prodrug approach could help mitigate the low permeability associated with the acid subtype. Other than the poor PAMPA permeability, excellent ADME properties were observed for 14q and 10 including very high aqueous solubility and extraordinary plasma and microsomal stability in both humans and mice (Table 4). It is noteworthy that many compounds with a carboxylic acid functionality are substrates for organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs), cellular transporters expressed in essentially every epithelium.50 To improve the overall antiviral potency, our future medicinal chemistry will explore enhancing PAMPA permeability and/or OATP-mediated cellular uptake.51

Table 4.

Solubility, permeability, and in vitro metabolic stabilities of selected analogs

| Cpd | Aqueous Solubility (μM)a, n=3 | Plasma Stability t1/2 (h), n = 3 | Microsomal Stabilityb t1/2 (min), n = 3 | PAMPA Permeability Pec (10−6 cm/s), n = 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Mouse | Human | Mouse | |||

| 13d | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| 13q | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| 14j | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.07 ± 0.1 |

| 14c | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0 |

| 14h | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.06 ± 0.03 | |

| 14r | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0 |

| 15l | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 12.4 ± 0.7 |

| 15b | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| 14q | ≥ 3173 | > 24d | > 24d | > 120e | > 120e | 0.05 ± 0.05 |

| 10 | 1478.0 ± 21.4 | > 24d | > 24d | > 120e | > 120e | 0 |

| VPM | -- | -- | -- | 11.1 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.02 | -- |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Aqueous solubility were determined in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS, pH 7.2).

CYP enzyme cofactor: NADPH. Verapamil (VPM) was used as the control.

Pe: The apparent permeability coefficient. High Permeability: >1.5 × 10−6 cm/s; Low Permeability: < 1.5× 10−6 cm/s.

Remaining percentage at 6h incubation > 94%.

Remaining percentage at the end of incubation (60 min) > 95%.

Molecular docking.

To further characterize target binding, we have performed molecular docking with all 57 analogs of the three DHP subtypes. Compounds were docked into the active site of HCMV pUL89-C (PDB code: 6EY747), which features a classic DDE motif (D463, E534, and D651) chelating two Mn2+ ions required for the endonuclease activity.19 For metal-binding chemotypes, a signature metal-binding network involving docked ligands, the two active site Mn2+ ions, and the DDE motif is expected. To analyze the binding modes of the DHP chemotype, we present here the docking poses of three analogs with the same R1 (R1 = 2-thiophene): acid 10, ester 13d, and amide 11 (Figure 5). Interestingly, energetically most favored poses of all three analogs feature a unique metal-binding mode in which the chelating triad consists of two oxygen atoms and one nitrogen atom, rather than the three oxygen atoms observed with previous metal-binding chemotypes.20, 23 In addition, each analog is predicted to use a distinct set of chelating atoms (Figure 5). Specifically, for acid analog 10 (cyan, XP GScore = −10.74 kcal/mol), the thiophene ring is situated in close proximity to K583 to allow a possible π-cation interaction (Figure 5A). The phenyl ring of the F466 is aligned in parallel to the central DHP core to potentially enable a π-π interaction. For ester analog 13d (light blue, XP GScore = −8.65 kcal/mol), the ligand is flipped compared to 10, such that the carboxylate group is pointing away from the metal which binds to the other two oxygen atoms (Figure 5B). As a result, the thiophene ring is situated too far away from K583 to confer the π-cation interaction (Figure 5B). The amide analog 11 (green, XP GScore = −7.81 kcal/mol) is predicted to bind to the metals in a mode to potentially allow both the thiophene ring and the amide phenyl ring to interact with K583, though the ordinary docking score suggests that both the metal chelation and the interactions with K583 may be suboptimal.

Figure 5.

Docking poses of selected DHP analogs into HCMV pUL89 active site (PDB code: 6EY7)52. (A) Predicted binding mode of acid analog 10 (cyan, XP GScore = −10.74 kcal/mol). (B) Predicted binding mode of ester analog 13d (light blue, XP GScore = −8.65 kcal/mol). (C) Predicted binding mode of amide analog 11 (green, XP GScore = −7.81 kcal/mol).

Conclusion.

We have explored three different DHP subtypes, the carboxylic acids (14), the methyl carboxylates (13), and the carboxamides (15), for their ability to inhibit the endonuclease activity of HCMV pUL89. Specifically, we have synthesized a total of 57 analogs and tested them in multiple biochemical, biophysical, in silico, antiviral and ADME assays. In the biochemical functional assay, 38 of the 57 analogs inhibited pUL89-C in the sub to low μM range, with 13 compounds displaying nM potencies. Biophysically, most analogs produced significant right shifts in the TSA and good scores when docked to the pUL89-C active site. In vitro and in silico characterization also showed that the acid subtype inhibited and bound pUL89-C better than the ester and amide subtypes. In the cell-based antiviral assay, six analogs demonstrated moderate potencies with EC50s in the low μM range, five of which exhibiting no cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 100 μM. In vitro ADME characterization revealed excellent aqueous solubility, plasma stability, and metabolic stability associated with the carboxylic acid subtype, though cellular uptake via passive diffusion appeared to be a barrier as indicated by the lack of permeability in the PAMPA permeability assay. Collectively, these biochemical, biophysical and antiviral results validate the DHP chemotype as a viable scaffold for developing pUL89-C targeting antivirals against HCMV. The in vitro ADME characterization also points to improving cellular uptake of the DHP carboxylic acid subtype as a focus of future medicinal chemistry efforts.

Experimental

Chemistry general procedures.

All commercial chemicals were used as supplied unless otherwise indicated. Flash chromatography was performed on a Teledyne Combiflash RF-200 with RediSep columns (silica) and indicated mobile phase. All moisture sensitive reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of ultra-pure argon with oven-dried glassware. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 600 or Bruker 400 MHz spectrometers. Mass data were acquired using an Agilent 6230 TOF LC/MS spectrometer. Melting points were taken using Electrothermal Mel-Temp melting point apparatus. Compound purity analysis was performed using Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC with an Eclipse C18 column (3.5 μm 4.6×100 mm). HPLC conditions: Flow rate = 1.0 mL/min; Solvent A = 0.1% TFA in water; Solvent B = 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile; Gradient (B %): 0–6 min (5–100); 6–8 min (100); 8–9 min (100–5). Determined purity was > 95% for all final compounds.

Synthesis of analogs of 17.

Analogs of 17 were synthesized according to a previously reported strategy.53 Briefly, an ethanol solution of the appropriate carbonitrile 16 was added hydroxylamine solution (50 wt.% in H2O). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at 70 °C. After this time, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue obtained was triturated with hexanes to afford the corresponding 17 analogs.

Synthesis of analogs of 13.

To a solution of analogs 17 in methanol was added dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate dropwise at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was then stirred at room temperature overnight. After this time, the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue obtained was suspended in o-xylene. The reaction mixture was irradiated at 140 °C for 40 min. After this time, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered. The residue obtained was triturated with diethyl ether and then purified by column chromatography (silica gel, CH2Cl2 to 90:10 CH2Cl2/MeOH, gradient elution) to afford the methyl carboxylate analogs of 13.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13a).

Yield: 50%. Off-white solid, m.p. 228–229°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.69 (br s, 1H), 10.12 (br s, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.3, 159.0, 147.6, 144.9, 128.5, 52.2, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C7H8N2O4 [M + H]+ 185.0562, found 185.0566.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-phenyl-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13b).

Yield: 30%. Brown solid, m.p. 228–229°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.10 (br s, 1H), 10.49 (br s, 1H), 8.01 (dd, J = 7.6, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.52−7.47 (m, 3H), 3.86 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.0, 159.5, 146.0, 145.4, 132.0, 130.7, 128.9, 128.7, 128.6, 127.1, 52.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H10N2O4 [M + H]+ 247.0719, found 247.0720.

Methyl 2-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13c).

Yield: 35%. Light brown solid, m.p. 254–255°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.10 (br s, 1H), 10.51 (br s, 1H), 8.06 (dd, J = 8.8, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.9, 164.8, 162.4, 159.5, 145.2 (d, JCF = 23.4 Hz), 129.7 (d, JCF = 8.9 Hz), 128.7 (d, JCF = 16.9 Hz), 115.6 (d, JCF = 21.9 Hz), 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H9FN2O4 [M + H]+ 265.0625, found 265.0630.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13d).

Yield: 44%. Brown solid, m.p. 259–260°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.24 (br s, 1H), 10.44 (br s, 1H), 7.99 (dd, J = 3.8, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 5.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (dd, J = 5.1, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.7, 159.1, 144.9, 142.0, 136.6, 131.0, 128.9, 128.3, 128.0, 52.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C10H8N2O4S [M + H]+ 253.0283, found 253.0285.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-2-(3-methylthiophen-2-yl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13e).

Yield: 35%. Pink solid, m.p. 194–195°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.79 (br s, 1H), 10.48 (br s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 5.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.8, 159.3, 138.8, 131.3, 127.7, 52.3, 15.0. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C11H10N2O4S [M + H]+ 267.0440, found 267.0419.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-3-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13f).

Yield: 40%. Off-white solid, m.p. 243–244°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.98 (br s, 1H), 10.39 (br s, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 7.66 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.9, 159.3, 148.3, 144.9, 141.4, 134.6, 127.4, 127.0, 126.6, 52.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C10H8N2O4S [M + H]+ 253.0283, found 253.0278.

Methyl 2-(furan-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13g).

Yield: 35%. Yellow solid, m.p. 247–248°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.10 (br s, 1H), 10.52 (br s, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 6.68 (s, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.8, 164.3, 158.9, 145.8, 145.3, 138.2, 128.8, 112.7, 112.3, 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C10H8N2O5 [M + H]+ 237.0511, found 237.0515.

Methyl 2-([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13h).

Yield: 22%. Red solid, m.p. 251–252°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.14 (s, 1H), 10.52 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.02 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.0, 164.4, 159.6, 145.6, 145.4, 142.2, 139.0, 130.9, 129.0, 128.6, 127.7, 126.9, 126.8, 126.8, 126.7, 52.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C18H14N2O4 [M + H]+ 323.1032, found 323.1035.

Methyl 2-benzyl-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13i).

Yield: 42%. Off-white solid, m.p. 233–235°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.94 (s, 1H), 10.24 (s, 1H), 7.33 − 7.21 (m, 5H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.2, 159.1, 149.4, 145.0, 136.6, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 126.8, 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H12N2O4 [M + H]+ 261.0875, found 261.0868.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-2-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13j).

Yield: 30%. White solid, m.p. 204–205°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.90 (s, 1H), 10.22 (s, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.75 (s, 2H), 2.25 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.2, 159.1, 149.6, 144.9, 135.8, 133.5, 129.0, 128.9, 128.5, 52.2, 20.6. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C14H14N2O4 [M + H]+ 275.1032, found 275.1013.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13k).

Yield: 60%. Brown solid, m.p. 254–255°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.85 (s, 1H), 10.20 (s, 1H), 9.29 (s, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.68 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.3, 159.2, 156.2, 150.0, 144.9, 129.8, 129.6, 129.6, 128.9, 126.7, 115.3, 52.8, 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H12N2O5 [M + H]+ 277.0824, found 277.0825.

Methyl 2-(4-fluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate ZW-1749 (13l).

Yield: 43%. White solid, m.p. 233–234°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.93 (br s, 1H), 10.26 (br s, 1H), 7.38 − 7.27 (m, 2H), 7.19 − 7.08 (m, 2H), 3.80 (s, 5H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.2, 162.4, 160.0, 159.1, 149.2, 145.1, 132.7 (d, JCF = 3.2 Hz), 130.6 (d, JCF = 8.1 Hz), 128.8, 115.2 (d, JCF = 21.3 Hz), 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H11FN2O4 [M + H]+ 279.0781, found 279.0769.

Methyl 2-(4-chlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13m).

Yield: 45%. White solid, m.p. 229°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.94 (s, 1H), 10.28 (s, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.1, 159.1, 149.0, 145.1, 135.6, 131.5, 130.7, 130.6, 128.8, 128.4, 128.4, 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H11ClN2O4 [M + H]+ 295.0486, found 295.0479.

Methyl 2-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13n).

Yield: 65%. White solid, m.p. 235–237°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.95 (s, 1H), 10.28 (s, 1H), 7.35 (td, J = 8.6, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (td, J = 9.9, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (td, J = 8.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (s, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.1, 162.2 (d, JCF = 12.8 Hz), 161.2 (d, JCF = 12.2 Hz), 160.6 (d, JCF = 12.8 Hz), 159.5 (d, JCF = 12.2 Hz), 159.1, 148.0, 145.1, 132.1 (dd, JCF = 9.7, 5.7 Hz), 128.8, 119.8 (dd, JCF = 15.8, 3.6 Hz), 111.4 (dd, JCF = 21.1, 3.6 Hz), 103.8 (t, JCF = 25.8 Hz), 52.2, 32.6 (d, JCF = 2.4 Hz). HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H10F2N2O4 [M + H]+ 297.0687, found 297.0674.

Methyl 2-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13o).

Yield: 67%. White solid, m.p. 249–251°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.97 (s, 1H), 10.30 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.1, 159.7, 155.5, 147.8, 145.1, 134.4, 133.6, 132.7, 132.5, 128.8, 127.5, 52.4, 37.1. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H10Cl2N2O4 [M + H]+ 329.0096, found 329.0093.

Methyl 2-(3,4-difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13p).

Yield: 60%. White solid, m.p. 229°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.91 (br s, 1H), 10.30 (br s, 1H), 7.39−7.34 (m, 2H), 7.15 − 7.09 (m, 1H), 3.82 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.1, 159.1, 150.0 (d, JCF = 12.7 Hz), 149.3 (d, JCF = 12.6 Hz), 148.6, 148.4, 148.3, 147.7, 147.6, 145.2, 134.1 (dd, JCF = 6.1, 3.8 Hz), 128.7, 125.6 (dd, JCF = 6.4, 3.4 Hz), 117.8 (d, JCF = 17.3 Hz), 117.4 (d, JCF = 17.1 Hz), 52.2, 38.8. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H10F2N2O4 [M + H]+ 297.0687, found 297.0680.

Methyl 2-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13q).

Yield: 32%. Off-white solid, m.p. 228–229°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.92 (s, 1H), 10.29 (s, 1H), 7.58−7.56 (m, 2H), 7.26 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.1, 159.1, 148.3, 145.3, 137.5, 131.1, 130.9, 130.6, 129.5, 129.2, 128.6, 125.7, 52.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H10Cl2N2O4 [M + H]+ 329.0096, found 329.0100.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13r).

Yield: 57%. White solid, m.p. 234°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.98 (s, 1H), 10.30 (s, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 4.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97−6.95 (m, 2H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.0, 159.0, 148.5, 145.1, 138.1, 128.7, 126.9, 126.4, 125.3, 52.2, 34.4. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C11H10N2O4S [M + H]+ 267.0440, found 267.0437.

Methyl 5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-3-ylmethyl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylate (13s).

Yield: 55%. White solid, m.p. 235–236°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.92 (s, 1H), 10.26 (s, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 6.0, 1H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.2, 159.1, 149.0, 145.1, 136.4, 128.7, 128.2, 126.3, 122.5, 52.2, 34.9. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C11H10N2O4S [M + H]+ 267.0440, found 267.0429.

Synthesis of analogs of 10, 12, and 14.

A solution of the methyl carboxylate analogs 13 in methanol was added 2 M LiOH. The reaction mixture was refluxed overnight. After this time, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and the pH was adjusted to 2–3 with 2 M HCl solution. The precipitate obtained was filtered and washed with water and diethyl ether to afford the carboxylic acid analogs of 10, 12, and 14. In the case when no significant precipitate was observed, the reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 to afford the carboxylic acid analogs of 10, 12, and 14.

5-Hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14a).

Yield: 61%. White solid, m.p. 225–226°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, dmso) δ 2.40 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.0, 159.0, 152.8, 149.2, 120.0, 17.40. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C6H6N2O4 [M + H]+ 171.0406, found 171.0402.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-2-phenyl-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14b).

Yield: 61%. Yellow solid, m.p. 201–202°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.05 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 7.52−7.47 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.1, 159.1, 147.3, 146.1, 132.0, 130.8, 128.7, 128.5, 128.2, 128.1, 127.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C11H8N2O4 [M + H]+ 233.0562, found 233.0546.

2-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14c).

Yield: 37%. White solid, m.p. 211–212°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.11 (dd, J = 8.6, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.1, 164.9, 162.4, 159.1, 147.3, 145.2, 129.8 (d, JCF = 8.9 Hz), 128.6 (d, JCF = 2.9 Hz), 128.1, 115.5 (d, JCF = 21.9 Hz). HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C11H7FN2O4 [M + H]+ 251.0468, found 251.0471.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (10).

Yield: 34%. Brown solid, m.p. 210–211°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.04 (br s, 1H), 7.99 (dd, J = 3.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 5.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (dd, J = 5.1, 3.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.9, 158.7, 146.7, 142.0, 136.8, 131.0, 128.8, 128.3, 127.9. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C9H6N2O4S [M + H]+ 239.0127, found 239.0129.

5-Hydroxy-2-(3-methylthiophen-2-yl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14e).

Yield: 70%. Dark brown solid, m.p. 221–222°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.66 (br s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.0, 158.9, 146.5, 143.4, 138.9, 131.3, 129.4, 128.9, 127.7, 15.0. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C10H8N2O4S [M + H]+ 253.0283, found 253.0270.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-3-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14f).

Yield: 60%. Yellow solid, m.p. 183–184°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.82 (br s, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.0, 158.9, 147.2, 142.4, 134.7, 128.1, 127.2, 127.1, 126.9. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C9H6N2O4S [M + H]+ 239.0127, found 239.0117.

2-([1,1’-Biphenyl]-4-yl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14h).

Yield: 49%. Orange solid, m.p. 185–186°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.06 (br s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.0, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.1, 165.3, 159.1, 147.4, 145.7, 142.2, 139.0, 130.9, 129.1, 129.0, 128.7, 128.3, 128.1, 127.9, 126.9, 126.8, 126.7. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C17H12N2O4 [M + H]+ 308.0797, found 308.0800.

2-Benzyl-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (12).

Yield: 41%. White solid, m.p. 188–189°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.33 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 4H), 7.26 (h, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.3, 159.1, 151.1, 149.6, 135.5, 128.7, 128.6, 127.1, 123.1, 37.8. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H10N2O4 [M + H]+ 247.0719, found 274.0715.

5-Hydroxy-2-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14j).

Yield: 70%. White solid, m.p. 200–202°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.22 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.91 (s, 2H), 2.26 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.2, 159.1, 151.2, 149.8, 136.3, 132.4, 129.2, 128.5, 122.8, 37.27, 20.61. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H12N2O4 [M + H]+ 261.0875, found 261.0866.

5-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14k).

Yield: 41%. Off-white solid, m.p. 229–230°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.37 (s, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.9, 159.2, 156.6, 151.6, 150.3, 129.8, 129.8, 125.3, 122.1, 115.4, 36.6. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H10N2O5 [M + H]+ 263.0668, found 263.0670.

2-(4-Fluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14l).

Yield: 47%. White solid, m.p. 199–200°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.38 (dd, J = 8.5, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.4, 162.6, 160.1, 159.1, 150.8, 149.4, 131.7 (d, J = 3.0 Hz), 130.7 (d, J = 8.1 Hz), 123.4, 115.4 (d, J = 21.3 Hz), 37.1. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H9FN2O4 [M + H]+ 265.0625, found 265.0625.

2-(4-Chlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14m).

Yield: 73%. White solid, m.p. 208–209°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.40 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.6, 159.1, 150.6, 149.1, 134.6, 131.8, 130.8, 130.6, 128.5, 128.5, 123.7, 37.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H9ClN2O4 [M + H]+ 281.0329, found 281.0323.

2-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14n).

Yield: 95%. Light brown solid, m.p. 167–168°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 3.93 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.2, 161.0, 160.7, 159.0, 149.2, 148.1, 132.0 (d, JCF = 7.3 Hz), 125.5, 119.4, 111.4 (d, JCF = 23.0 Hz), 103.8 (t, JCF = 25.7 Hz), 31.7. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H8F2N2O4 [M + H]+ 283.0530, found 283.0525.

2-(2,4-Dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14o).

Yield: 65%. Brown solid, m.p. 143–144°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.3, 159.1, 149.0, 147.8, 134.2, 133.2, 132.3 (d, J = 23.2 Hz), 128.7, 127.4, 125.9, 36.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H8Cl2N2O4 [M + H]+ 314.9939, found 314.9939.

2-(3,4-Difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14p).

Yield: 75%.White solid, m.p. 187–188°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.44−7.37 (m, 2H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 3.92 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.7, 159.1, 150.4, 150.0 (d, JCF = 12.9 Hz), 149.4 (d, JCF = 12.7 Hz), 148.8, 148.3 (d, JCF = 12.7 Hz), 147.8 (d, JCF = 12.7 Hz), 133.2, 125.7 (dd, JCF = 6.5, 3.4 Hz), 124.0, 117.7 (dd, JCF = 62.8, 17.1 Hz), 37.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H8F2N2O4 [M + H]+ 283.0530, found 283.0522.

2-(3,4-Dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14q).

Yield: 91%. Off-white solid, m.p. 200–201°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.64 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.8, 160.0, 159.1, 150.3, 148.5, 136.6, 131.0, 130.7, 129.8, 129.3, 124.2, 37.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C12H8Cl2N2O4 [M + H]+ 314.9939, found 314.9935.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14r).

Yield: 57%. White solid, m.p. 177–178°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.41 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.97 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.8, 159.0, 150.1, 148.7, 137.1, 127.0, 126.9, 125.7, 124.3, 33.0. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C10H8N2O4S [M + H]+ 253.0283, found 253.0277.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-3-ylmethyl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (14s).

Yield: 45%.White solid, m.p. 177–178°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.38 (s, 1H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 3.96 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.7, 159.6, 151.7, 149.7, 135.9, 128.6, 127.0, 123.6, 111.5, 33.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C10H8N2O4S [M + H]+ 253.0283, found 253.0279.

Synthesis of analogs of 11 and 15.

A solution of the dihydropyrimidinecarboxylic acid (10, 12 and 14) in N, N-dimethylforamide was added the appropriate amine. The reaction mixture was stirred at 90 °C overnight. After this time, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and acidified to pH 2–3 using 1 M HCl solution. The precipitate was isolated by filtration and washed with water and diethyl ether to afford the carboxamide analogs of 11 and 15.

N-Benzyl-5-hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15a).

Yield: 21%. White solid, m.p. 191–192°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.58 (s, 1H), 12.32 (s, 1H), 9.30 (s, 1H), 7.35−7.30 (m, 4H), 7.25 (h, J = 4 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.5, 158.0, 147.9, 147.2, 138.6, 128.3, 127.5, 127.0, 126.8, 42.1, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H13N3O3 [M + H]+ 260.1035, found 260.1006.

5-Hydroxy-N-(4-methoxybenzyl)-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15b).

Yield: 25%. White solid, m.p. 171–172°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.36 (s, 1H), 9.21 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.5 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.38 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 2.23 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.4, 158.4, 158.0, 147.9, 147.2, 130.5, 129.0, 128.8, 126.8, 113.7, 113.7, 55.1, 41.6, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C14H15N3O4 [M + H]+ 290.1141, found 290.1125.

5-Hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15c).

Yield: 73%. White solid, m.p. 184–185°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.57 (s, 1H), 12.34 (s, 1H), 9.23 (t, J = 6.7, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.40 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 2.24 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.5, 158.0, 147.9, 147.2, 136.1, 135.5, 128.9, 127.5, 126.8, 41.9, 20.7, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C14H15N3O3 [M + H]+ 274.1192, found 274.1157.

5-Hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15d).

White solid, m.p. 220–221°C. Yield: 60%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.60 (s, 1H), 12.20 (s, 1H), 9.44 (t, J = 6.0, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.2, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.2, 2H), 4.44 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.25 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.8, 158.0, 148.0, 147.3, 143.5, 128.1, 127.8, 127.5, 126.7, 125.7, 125.2 (q, JCF = 3.8 Hz), 125.2, 123.0, 41.9, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C14H12F3N3O3 [M + H]+ 328.0909, found 328.0998.

N-(4-Fluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15e).

Yield 32%. Off-white solid, m.p. 199–200°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.60 (s, 1H), 12.28 (s, 1H), 9.33 (t, J = 6.7, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 8.5, 5.7 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 4.41 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.6, 162.5, 160.1, 158.0, 147.9, 147.2, 134.8 (d, JCF = 3.1 Hz), 129.6 (d, JCF = 8.1 Hz), 126.8, 115.1 (d, JCF = 21.3 Hz), 41.5, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H12FN3O3 [M + H]+ 278.0941, found 278.0945.

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15f).

Yield: 63%. Off-white solid, m.p. 219–220°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.59 (s, 1H), 12.16 (s, 1H), 9.27 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (td, J = 8.6, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (td, J = 9.9, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (td, J = 8.5, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 4.47 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.7, 162.7 (d, JCF = 12.1 Hz), 161.2 (d, JCF = 12.4 Hz), 160.3 (d, JCF = 12.1 Hz), 158.7 (d, JCF = 12.4 Hz), 158.0, 147.6 (d, JCF = 78.0 Hz), 130.9 (dd, JCF = 9.9, 5.8 Hz), 126.7, 121.6 (dd, JCF = 15.0, 3.7 Hz), 111.4 (dd, JCF = 21.2, 3.6 Hz), 103.7 (t, JCF = 25.8 Hz), 35.6 (d, JCF = 4.0 Hz), 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H11F2N3O3 [M + H]+ 296.0847, found 296.0842.

N-(3,4-Dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-2-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15g).

Yield: 30%. White solid, m.p. 240–241°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.59 (s, 1H), 12.16 (s, 1H), 9.40 (t, J = 5.9, 1H), 7.60–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.25 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.7, 158.0, 148.0, 147.2, 139.9, 130.8, 130.6, 129.6, 129.6, 127.9, 126.7, 41.2, 20.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C13H11Cl2N3O3 [M + H]+ 328.0256, found 328.0254.

5-Hydroxy-N-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-2-phenyl-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15h).

Yield: 70%. White solid, m.p. 220–221°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.92 (s, 1H), 12.62 (s, 1H), 9.55 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.55−7.47 (m, 3H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.49 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.6, 162.3, 158.5, 148.1, 146.0, 136.1, 135.6, 131.7, 130.9, 128.9, 128.4, 127.5, 127.4, 127.0, 42.0, 20.7. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C19H17N3O3 [M + H]+ 336.1348, found 336.1345.

N-(3,4-Dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-phenyl-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15i).

Yield: 73%. White solid, m.p. 244–245°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.93 (s, 1H), 12.40 (s, 1H), 9.62 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, 2H), 7.63−7.57 (m, 2H), 7.51 (q, J = 6.9, 6.3 Hz, 3H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.9, 158.4, 148.0, 146.1, 139.9, 131.6, 130.9, 130.9, 129.6, 129.4, 128.4, 127.8, 127.5, 126.9, 41.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C18H13Cl2N3O3 [M + H]+ 390.0412, found 390.0401.

N-Benzyl-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (11).

Yield: 60%. Yellow solid, m.p. 277–278°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 12.53 (s, 1H), 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.35 (s, 4H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.17 (s, 1H), 4.54 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.5, 159.0, 147.1, 142.8, 138.6, 136.0, 134.2, 132.5, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 127.4, 127.0, 42.3. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C16H13N3O3S [M + H]+ 328.0756, found 328.0756.

5-Hydroxy-N-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15j).

Yield: 67%. Light yellow solid, m.p. 208–281°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 12.55 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.19 − 7.13 (m, 3H), 4.48 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.2, 158.0, 147.6, 142.2, 136.2, 135.5, 131.3, 128.9, 128.5, 128.3, 127.4, 126.9, 42.1, 20.7. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C17H15N3O3S [M + H]+ 342.0912, found 342.0895.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4carboxamide (15k).

Light yellow solid, m.p. 277–278°C. Yield: 58%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.07 (s, 1H), 12.40 (s, 1H), 9.29 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.62 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.5, 158.0, 147.6, 143.5, 142.3, 136.2, 131.3, 128.6, 128.3, 128.1, 127.8, 127.6, 127.0, 126.9, 125.3 (q, JCF = 3.8 Hz), 123.4, 42.1. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C17H12F3N3O3S [M + H]+ 396.0630, found 396.0628.

N-(4-Fluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15l).

Brown solid, m.p. 245–246°C. Yield: 70%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 12.49 (s, 1H), 9.18 (s, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.5, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.18−7.15 (m, 3H), 4.51 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.3, 162.1, 160.5, 158.0, 147.7, 142.2, 136.2, 134.8 (d, JCF = 3.0 Hz), 131.3, 129.5 (d, JCF = 8.5 Hz), 128.5, 128.3, 126.9, 115.1 (d, JCF = 21.3 Hz), 41.6. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C16H12FN3O3S [M + H]+ 346.0662, found 346.0661.

N-(4-Chlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15m).

Yield: 62%. Yellow solid, m.p. 270–271°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 12.46 (s, 1H), 9.21 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41−7.36 (m, 4H), 7.18 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.4, 158.0, 147.6, 142.3, 137.7, 136.2, 131.6, 131.3, 129.3, 128.6, 128.3, 128.3, 126.9, 41.7. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C16H12ClN3O3S [M + H]+ 362.0366, found 362.0362.

N-(3,4-Difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15n).

Yield: 62%. Light yellow solid, m.p. 261–262°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.06 (s, 1H), 12.39 (s, 1H), 9.21 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.42−7.38 (m, 2H), 7.21−7.17 (m, 2H), 4.51 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.4, 158.0, 150.0 (d, JCF = 12.8 Hz), 149.3 (d, JCF = 12.7 Hz), 148.4 (d, JCF = 12.6 Hz), 147.7 (d, JCF = 12.6 Hz), 147.6, 142.3, 136.4 (d, JCF = 4.4 Hz), 131.3, 128.4 (d, JCF = 41.7 Hz), 127.0, 124.2 (dd, JCF = 6.7, 3.5 Hz), 117.4 (d, JCF = 17.0 Hz), 116.5 (d, JCF = 17.3 Hz), 41.4. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C16H11F2N3O3S [M + H]+ 364.0567, found 364.0567.

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15o).

Yield: 60%. Light brown solid, m.p. 262–263°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.06 (s, 1H), 12.34 (s, 1H), 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.26−7.17 (m, 3H), 4.55 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.4, 162.3 (d, JCF = 12.0 Hz), 160.7 (t, JCF = 12.7 Hz), 159.1 (d, JCF = 12.4 Hz), 158.0, 147.6, 142.3, 136.1, 131.3, 130.8 (dd, JCF = 9.9, 5.8 Hz), 128.6, 128.3, 126.9, 121.7, 121.6 (d, JCF = 3.6 Hz), 111.5 (dd, JCF = 21.1, 3.6 Hz), 103.7 (t, JCF = 25.8 Hz), 35.8 (d, JCF = 4.0 Hz). HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C16H11F2N3O3S [M + H]+ 364.0567, found 364.0561.

N-(2,4-Dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15p).

Yield: 65%. Light yellow solid, m.p. 285–286°C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.09 (s, 1H), 12.23 (s, 1H), 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.05 (dd, J = 3.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.5, 158.0, 147.5, 145.9, 136.2, 134.7, 132.7, 132.4, 131.4, 129.9, 128.7, 128.6, 128.3, 127.5, 35.8. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C16H11Cl2N3O3S [M + H]+ 395.9976, found 395.9956.

5-Hydroxy-6-oxo-N-phenyl-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15q).

Yield: 67%. White solid, m.p. 260–161°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.17 (s, 1H), 11.69 (s, 1H), 10.13 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.78–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44−7.40 (m, 2H), 7.25 − 7.12 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.9, 161.0, 148.2, 141.9, 137.6, 136.9, 131.4, 130.9, 128.8, 128.7, 128.3, 125.0, 124.5, 121.2, 120.5. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C15H11N3O3S [M + H]+ 314.0599, found 314.0600.

2-Benzyl-5-hydroxy-N-(4-methylbenzyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15r).

Yield: 67%. White solid, m.p. 192–193°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.81 (s, 1H), 12.39 (s, 1H), 9.26 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39 − 7.28 (m, 4H), 7.23 (dd, J = 11.8, 7.4 Hz, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.43 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 2H), 2.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.4, 158.2, 149.5, 147.5, 136.5, 136.1, 135.5, 128.9, 128.6, 128.5, 127.5, 126.9, 126.8, 42.0, 20.7. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C20H19N3O3 [M + H]+ 350.1505, found 350.1500.

2-Benzyl-N-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-4-carboxamide (15s).

Yield: 61%. White solid, m.p. 194–195°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 12.83 (s, 1H), 12.20 (s, 1H), 9.41 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.41 − 7.28 (m, 5H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.47 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.7, 158.2, 149.6, 147.5, 139.8, 136.5, 130.9, 130.6, 129.6, 129.5, 128.6, 128.5, 127.9, 126.8, 126.8, 41.2. HRMS (ESI+): m/z calculated for C19H15Cl2N3O3 [M + H]+ 404.0569, found 404.0566.

In vitro pUL89-C endonuclease assay.

pUL89-C was expressed and purified as described.19 The pUL89-C bacterial expression plasmid was generated as described.21 The 60-bp ssDNA (5’-taatcgccttgcagcacatccccctttcgccagctggcgtaatagcgaagaggcccgcac) was labeled with a digoxigenin (DIG) tag at 5’ end; and the complementary ssDNA (5’-tcggtgcgggcctcttcgctattacgccagctggcgaaagggggatgtgctgcaaggcga) labeled with a 5’ biotin. Equal moles of ssDNAs were annealed to obtain the 60-bp dsDNA substrate at 1000 nM. pUL89-C was pre-incubated with compounds in DMSO (final concentration 5 μM) and reaction buffer (3mM MnCl2, 30 mM Tris pH 8 and 50 mM NaCl) for 15 min at room temperature (final DMSO concentration 1%). The reaction was initiated by 100 nM dsDNA substrate, incubated for 30 min at 37 °C and terminated with EDTA (final concentration 30 mM). The samples were transferred to streptavidin coated plates (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), incubated at room temperature with gentle shaking for 30 min and washed with 150 μL of wash buffer (25mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% BSA, and 0.05% Tween-20; pH 7.2) three times. Substrate was detected by adding 100 μL of anti-DIG- alkaline phosphatase (AP) conjugate antibody (0.15U/mL) (Roche Applied Sciences, Germany) to each well for 30 min, washing three times with 150 μL wash buffer, incubating with 100 μL of p-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) (1mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) for 30 min and the absorbance determined at 405 nm using BioTek Neo 2 plate reader, all at room temperature.

HCMV replication assay.

HFF cells (ATCC CRL-2088) were plated in 96-well plates (ThermoFisher) at 1.75 × 104 cells/well in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin streptomycin (P/S). Cells were inoculated the next day with HCMV ADCREGFP virus (obtained from Wade Bresnahan, University of Minnesota) at an MOI of 0.01 in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 1% P/S for 2 h. The inoculated cells were washed with 100 μL/well phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, media with test compounds in 0.5% DMSO, or 0.5% DMSO vehicle control, was added to each well and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 168 h. The infected cells were lysed to measure GFP fluorescence as an indication of the extent of virus replication. For lysis, 200 μl of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 2 mM trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N,N-tetraacetic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol) was added to each well and incubated for 10 min at 37°C, followed by a 30 min incubation at room temperature on a shaker. GFP relative fluorescence units were determined at excitation/emission 495/515 nm in a BioTek Neo2 plate reader. Compound doses were evaluated in triplicate and mean values of triplicate wells were determined and compared to the mean value for the wells that received vehicle control (DMSO alone). The EC50 was determined by comparing percent inhibition for nine serial dilutions of the compound and DMSO-treated cells using GraphPad Prism software. The EC50 value was defined as the compound concentration resulting in a 50% reduction in virus replication (GFP fluorescence) compared to DMSO.

Cell Viability Assay.

HFF cells were plated into 96-well plates at 1.75 × 104 cells/well in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. The next day cells were treated with compound in DMSO containing media (DMEM with 5% FBS and 1% P/S) at 37°C for 168 h (0.5% DMSO final concentration). Cellular viability was determined using the MTS-based tetrazolium reduction assay CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Compound doses were evaluated in triplicate and mean values of triplicate wells were to DMSO alone. The CC50 was determined by comparing cell viability for nine serial dilutions of the compound and DMSO-treated cells using GraphPad Prism software. The CC50 value was defined as the compound concentration resulting in a 50% reduction in viability compared to DMSO.

pUL89-C Thermal Shift Assay52, 54.

Test compounds (20 μM) were preincubated with 14.1μg of purified pUL89-C in reaction buffer (5mM MnCl2, 30 mM Tris pH 8 and 50 mM NaCl) for 15 min at room temperature. All reactions contained a final DMSO concentration of 0.5%. Sypro Orange Protein Gel Stain (Sigma Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 5X and samples were transferred to a 96-well PCR plate (Applied Biosystem, Catalog # 4306737). The plate was sealed with a Pure-AMP optically transparent plate seal (Catalog # P1001-Q) and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 3 min. A melt curve analysis was done by heating the samples from 25 to 99° C with a ramp rate of 0.015° C/s using a Quant Studio 3 PCR Machine (Applied Biosystems) with the fluorescence channel set for ROX. All samples were tested in triplicate. Data evaluation and melting point determination were done using the Protein Thermal Shift Software Version 1.4 from Applied Biosystems. The ΔTm for each sample was calculated by comparing the mean derivative Tm for the DMSO vehicle control to the mean derivative Tm of each test compound.

Aqueous solubility assay.

The aqueous solubility of each selected compound was determined in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) under thermodynamic solubility conditions. Briefly, a saturated solution was made by adding DPBS to excessive solid compound. The mixture was shaken at 200 rpm for 72h at ambient temperature to allow equilibrium between the solid and dissolved compound. The suspension was then filtered through a 0.45 μm PVDF syringe filter and the filtrate was collected for analysis using a LC-MS/MS system consisting of an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC (Agilent Technologie, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an AB Sciex QTrap 5500 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex LLC., Toronto, Canada).

Plasma stability assay.

The plasma stability assay was performed in triplicate by incubating each selected compound (1 μmol/L final concentration) in normal mouse (CD-1) or human plasma (Innovative Research, Novi, MI, USA) diluted to 80% with 0.1 mol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. At 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h, a 50 μL aliquot of the plasma mixture was taken and quenched with 150 μL of acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. The samples were then vortexed and refrigerated centrifuged (4 °C) at 15,000 rpm (Eppendorf centrifuge 5424R, Enfield, CT, USA) for 5 min. The supernatants were collected and analyzed by LC-MS/MS to determine the in vitro plasma half-life (t1/2).

Microsomal stability assay.

The in vitro microsomal stability assay was conducted in triplicate in commercially available mouse and human liver microsomes (Sekisui XenoTech, Kansas City, KS, USA), which were supplemented with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) as a cofactor. Briefly, a compound (1 μmol/L final concentration) was spiked into the reaction mixture containing liver microsomal protein (0.5 mg/mL final concentration) and MgCl2 (1 mmol/L final concentration) in 0.1 mol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The reaction was initiated by addition of 1 mmol/L NADPH, followed by incubation at 37 °C. A negative control was performed in parallel without NADPH to reveal any chemical instability or non-NADPH dependent enzymatic degradation for each compound. A reaction with positive control verapamil was also performed as in-house quality control to confirm the proper functionality of the incubation systems. At various time points (0, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min), a 50 μL of reaction aliquot was taken and quenched with 150 μL of acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. The samples were then vortexed and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and analyzed by LC-MS/MS to determine the in vitro metabolic half-life (t1/2).

Parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA).

The membrane permeability of selected compounds were evaluated using the Corning® BioCoat™ Pre-coated PAMPA Plate System (catalog. No. 353015, Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA). The pre-coated plate assembly, which was stored at −20°C, was taken to thaw for 30 min at room temperature. The permeability assay was carried out in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the 96-well filter plate, pre-coated with lipids, was used as the permeation acceptor and a matching 96 well receiver plate was used as the permeation donor. Compound solutions were prepared by diluting the 10 mmol/L DMSO stock solutions with 10% methanol in DPBS to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L. The compound solutions were added to the wells (300 μL/well) of the receiver plate and DPBS with 10% methanol was added to the wells (200 μL/well) of the pre-coated filter plate. The filter plate was then coupled with the receiver plate and the plate assembly was incubated at 25 °C without agitation for 5 h. At the end of the incubation, the plate was separated and the final concentrations of compounds in both donor wells and acceptor wells were analyzed using LC-MS/MS. Permeability of the compounds were calculated using the Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where A = filter area (0.3 cm2), VD = donor well volume (0.3 mL), VA = acceptor well volume (0.2 mL), t = incubation time (seconds), CA(t) = compound concentration in acceptor well at time t, CD(t) = compound concentration in donor well at time t, and Ceq was calculated using the Eq. (2):

| (2) |

A cutoff criteria of Pe value at 1.5 × 10−6 cm/s was used to classify the compounds into high and low permeability according to the literature report of this PAMPA plate system.48

Modeling and docking analysis.

Molecular modeling was performed using the Schrödinger small molecule drug discovery suite 2021–3,55 based on the crystal structure of HCMV pUL89-C bound with a diketoacid inhibitor (PDB code: 6EY747). Each compound was docked using Maestro56 (Schrödinger; LLC: New York, NY, USA) per standard protocols. 1) Protein preparation: the tetrameric protein was prepared using Protein preparation wizard57 (Schrödinger; LLC: New York, NY, USA), in which zero-order bonds to metals, missing hydrogen atoms, side-chains, loops were added using Prime; chain B, C, and D and waters beyond 5 Å were deleted; remaining four water molecules inside the active site were manually deleted to create space, and minimized using the OPLS3e force field58 to optimize the hydrogen bonding network and converge the heavy atoms to an RMSD of 0.3 Å. 2) Receptor grid generation: the active site around the native α, γ-diketoacid ligand was used to define the grid in Maestro covering all the residues within 12 Å, with the two active site Mn2+ions as constraints. 3) Ligand Preparation: all compound structres were drawn in ChemDraw and saved as sdf, which is subjected to LigPrep to generate conformers, possible protonation at pH of 7 ± 2, and metal binding states that serve as an input for docking process. 4) Ligand Docking: prepared ligands were docked using Glide XP59 (Glide version 8.2) with the van der Waals radii of nonpolar atoms for each of the ligands scaled by a factor of 0.8 to decrease penalties for the close contacts. All docked poses were subjected to post-docking minimization (PMD) to minimize a small number of poses within the field of the receptor to produce better poses. Each docked poses were further processed using PyMOL60 (Schrödinger; LLC: New York, NY, USA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health, grant number R01AI136982 (to RJG and ZW), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, grant number R35 GM118047 (to HA). We thank the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute for molecular modeling resources. The preparation of the structure data file (SDF) for molecular docking used JChem for Office licensed by ChemAxon.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- CDV

cidofovir

- DAA

direct-acting antivirals

- DHP

dihydroxypyrimidine

- FOS

foscarnet

- GCV

ganciclovir

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HPCA

hydroxypyridine carboxylic acid

- HPD-NH

6-arylamino-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione

- HPD-S

6-arylthio-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-dione

- INST

integrase strand transfer

- LTV

letermovir

- MBV

maribavir

- OATP

organic anion transporting polypeptides

- PAMPA

parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- pUL89-C

C-terminus of pUL89

- RAL

raltegravir

- RNase H

ribonuclease H

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- SD

standard deviation

- TSA

thermal shift assay

- XP

extra precision

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the methyl carboxylate catalogs (13, S2-S20), carboxylic acid analogs (10, 12, and 14, S21–38), and the carboxamide analogs (11 and 15, S39–58). HPLC traces for compounds 13d, 10, 13h, 13q, 14q and 15k. PDB coordinates for docked compounds 10, 13d and 11. Molecular formula strings (CSV). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Britt WJ Congenital Human Cytomegalovirus Infection and the Enigma of Maternal Immunity. J. Virol 2017, 91, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02392-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazzarotto T; Blazquez-Gamero D; Delforge ML; Foulon I; Luck S; Modrow S; Leruez-Ville M Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: A Narrative Review of the Issues in Screening and Management From a Panel of European Experts. Front. Pediatr 2020, 8, doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revello MG; Gerna G Pathogenesis and Prenatal Diagnosis of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. J. Clin. Virol 2004, 29, 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perello R; Vergara A; Monclus E; Jimenez S; Montero M; Saubi N; Moreno A; Eto Y; Inciarte A; Mallolas J; Martinez E; Marcos MA Cytomegalovirus Infection in HIV-Infected Patients in the Era of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. BMC Infect. Dis 2019, 19, doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4643-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gianella S; Letendre S Cytomegalovirus and HIV: A Dangerous Pas de Deux. J. Infect. Dis 2016, 214 Suppl 2, S67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limaye AP; Babu TM; Boeckh M Progress and Challenges in the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Cytomegalovirus Infection in Transplantation. Cli.n Microbiol. Rev 2020, 34, doi: 10.1128/CMR.00043-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faulds D; Heel RC Ganciclovir. A Review of Its Antiviral Activity, Pharmacokinetic Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy in Cytomegalovirus Infections. Drugs 1990, 39, 597–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Clercq E Clinical Potential of the Acyclic Nucleoside Phosphonates Cidofovir, Adefovir, and Tenofovir in Treatment of DNA Virus and Retrovirus Infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2003, 16, 569–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeichner SL Foscarnet. Pediatr. Rev 1998, 19, 399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martson AG; Edwina AE; Burgerhof JGM; Berger SP; de Joode A; Damman K; Verschuuren EAM; Blokzijl H; Bakker M; Span LF; van der Werf TS; Touw DJ; Sturkenboom MGG; Knoester M; Alffenaar JWC Ganciclovir Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Transplant Recipients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2021, 76, 2356–2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakki M Moving Past Ganciclovir and Foscarnet: Advances in CMV Therapy. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep 2020, 15, 90–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim ES Letermovir: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullard A FDA Approves Decades-Old Maribavir for CMV Infection. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov 2021, 21, doi: 10.1038/d41573-021-00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldner T; Hewlett G; Ettischer N; Ruebsamen-Schaeff H; Zimmermann H; Lischka P The Novel Anticytomegalovirus Compound AIC246 (Letermovir) Inhibits Human Cytomegalovirus Replication through a Specific Antiviral Mechanism That Involves the Viral Terminase. J. Virol 2011, 85, 10884–10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biron KK; Harvey RJ; Chamberlain SC; Good SS; Smith AA 3rd; Davis MG; Talarico CL; Miller WH; Ferris R; Dornsife RE; Stanat SC; Drach JC; Townsend LB; Koszalka GW Potent and Selective Inhibition of Human Cytomegalovirus Replication by 1263W94, a Benzimidazole L-Riboside with a Unique Mode of Action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 2365–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prichard MN Function of Human Cytomegalovirus UL97 Kinase in Viral Infection and Its Inhibition by Maribavir. Rev. Med. Virol 2009, 19, 215–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuber S; Wagner K; Goldner T; Lischka P; Steinbrueck L; Messerle M; Borst EM Mutual Interplay between the Human Cytomegalovirus Terminase Subunits pUL51, pUL56, and pUL89 Promotes Terminase Complex Formation. J. Viorl 2017, 91, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02384-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ligat G; Cazal R; Hantz S; Alain S The Human Cytomegalovirus Terminase Complex as an Antiviral Target: a Close-Up View. Fems. Microbiol. Rev 2018, 42, 137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadal M; Mas PJ; Blanco AG; Arnan C; Sola M; Hart DJ; Coll M Structure and Inhibition of Herpesvirus DNA Packaging Terminase Nuclease Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 16078–16083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kankanala J; Wang Y; Geraghty RJ; Wang Z Hydroxypyridonecarboxylic Acids as Inhibitors of Human Cytomegalovirus pUL89 Endonuclease. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 1658–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y; Mao L; Kankanala J; Wang Z; Geraghty RJ Inhibition of Human Cytomegalovirus pUL89 Terminase Subunit Blocks Virus Replication and Genome Cleavage. J. Virol 2017, 91, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02152-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y; Tang J; Wang Z; Geraghty RJ Metal-Chelating 3-Hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones Inhibit Human Cytomegalovirus pUL89 Endonuclease Activity and Virus Replication. Antiviral. Res 2018, 152, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L; Edwards TC; Sahani RL; Xie JS; Aihara H; Geraghty RJ; Wang ZQ Metal Binding 6-Arylthio-3-hydroxypyrimidine-2,4-diones Inhibited Human Cytomegalovirus by Targeting the pUL89 Endonuclease of the Terminase Complex. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2021, 222, 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]