Abstract

Background

Fracture fixation, in the present times, is classically done using mini plates. The position and number of plates to fixate a mandibular angle fracture have been and are still extensively researched and reported in the literature. A more recent addition is 3D mini plates.

Aim

To compare and evaluate the biomechanical behavior of one 2.0 mm titanium 3D miniplate fixation plate (4- hole) and one 2.0 mm titanium 4-hole miniplate in internal fixation of mandibular angle fractures.

Objective

To measure load at break, maximum load, and displacement at maximal load for internal fixation done with 3D mini plates and conventional mini plates respectively.

Methods

Five dry cadaveric mandibles were sectioned into 10 hemi-mandibles. Each cadaveric mandible was sectioned at the angle of mandible to simulate unfavorable mandibular angle fracture. The obtained hemimandible were divided into experimental groups (GROUP 1 and GROUP 2) with 5 samples in each group, plated with a linear miniplate and 3D miniplate respectively. Maximal load, Load at break, and displacement at maximum load were the only obtained parameters for comparison.

Results

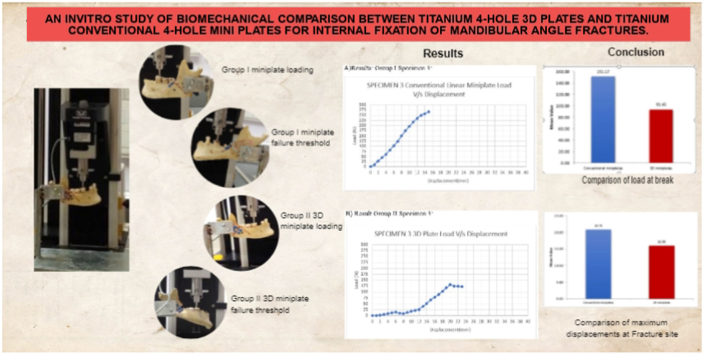

Conventional miniplate showed greater mean maximum load values of 174.93 N±54.45 compared to 3D mini plates which recorded a mean maximum load value of 106.96 N ± 23.86. Load at break and displacement at maximum load were found to be both insignificant.

Conclusion

The results in this study showed statistically no significant difference with any of the above parameters except maximal load, between the two groups evaluated. Conventional linear miniplate according to Champy's lines of osteosynthesis can be used successfully for providing satisfactory osteosynthesis with the definitive advantage of cost-effectiveness.

Keywords: Mandibular angle, Fracture, Cadaveric mandible, Champy's lines, Miniplate, 3D miniplate, In-vitro

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

An important clinical challenge and is one of the most discussed topics in maxillofacial traumatology is the treatment of mandibular angle fractures. Miniplate osteosynthesis is the standard treatment for the fractures of the mandibular angle. A major determinant of the clinical outcome and also a point of controversy, is the stability provided by miniplate fixation of mandibular angle fractures.

Michelet et al. (1973)1 and Champy et al. (1975)2 played a key role in making Miniplate osteosynthesis an important fixation method still in use today in maxillofacial and craniofacial surgery. Literature has extensively reviewed and reported the position and number of plates needed to fixate mandibular angle fractures. In the treatment of non-comminuted mandibular angle fractures, many investigators recommend a single non-compression miniplate at the superior border. Angle fractures are often treated with superior border plates, but several other options need to be studied and evaluated for comparison.

Three-dimensional (3D) mini plates have been developed by Farmand and Dupoirieux,3 by joining two mini plates with interconnected vertical cross-bars. The basic principle of the three-dimensional bone miniplate is the concept of a quadrangular configuration as a geometrically stable configuration. The geometric shape of the plate increases its stability rather than its thickness or length.

We hypothesized that 3D-miniplates would be more stable than conventional miniplates in the treatment of unfavorable mandibular angle fractures. A surgeon must have clinical data combined with biomechanical results in order to have a successful management and a good treatment outcome.

2. Materials and methods

5 dry cadaveric mandibles were used for the study. The inclusion criteria being, human Cadaver Adult mandibles and the presence of bilateral posterior teeth. The exclusion criteria were Atrophied mandibles, mandibles with obvious bony pathology, any evidence of mandibular fracture, and pediatric mandibles. The mandibles were collected from the Department of Anatomy, of a Tertiary care center, Trivandrum. The Ethical Committee Clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

These mandibles were sectioned in the midline using a rotary handpiece with a No. 703 bur to create 10 hemimandibles. The obtained hemimandibles were divided into experimental groups Group I and Group II, with five specimens from each mandible in each group (Table I).

Table 1.

Data on maximum load, displacement, and load at break between two groups.

| Sl. No. | Maximum Load (N) | Displacement (mm) | Load at break (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional linear miniplate Group I | |||

| 1 | 148.03 | 18.75 | 108.32 |

| 2 | 160.40 | 21.35 | 154.45 |

| 3 | 270.06 | 15.55 | 256.46 |

| 4 | 162.73 | 19.10 | 133.10 |

| 5 | 133.39 | 29.21 | 103.49 |

| 3D miniplate Group II | |||

| 1 | 88.78 | 12.78 | 63.58 |

| 2 | 97.27 | 18.32 | 89.52 |

| 3 | 135.81 | 20.60 | 125.65 |

| 4 | 129.03 | 16.65 | 114.60 |

| 5 | 83.88 | 11.65 | 73.88 |

Description Of Groups According To Plate Configuration And Location:

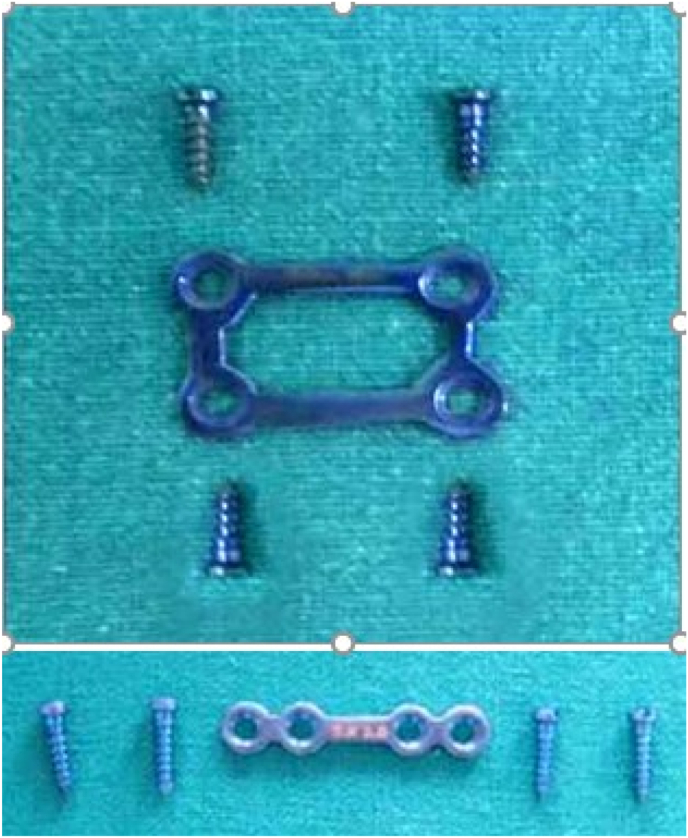

Group I: One 2 × 2.0 mm four holes with gap titanium miniplate and four 2 × 8 mm screws

Group II: One 2 × 2.0 mm four holes with gap titanium 3D plate and four 2 × 8 mm screws

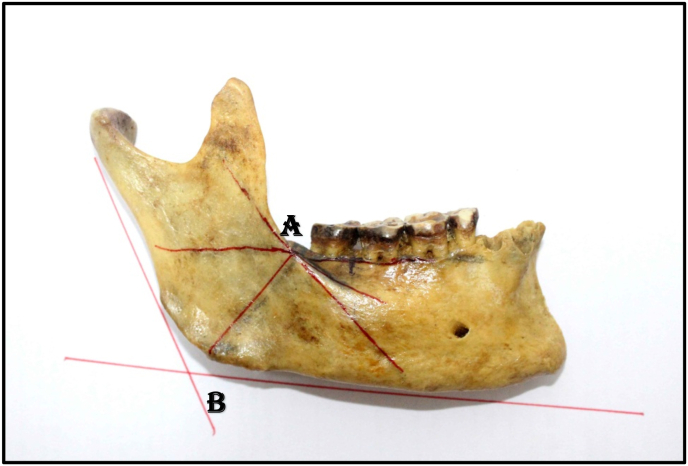

In each experimental hemi-mandible fracture line was simulated at the angle of mandible using standard landmarks and markings. Markings for angle fracture were made on the hemimandibles by joining the two points A and B (Fig. 1) and the cuts were made using a Gigli saw. Point A is the point of intersection of a tangent drawn along the external oblique ridge onto the lateral surface of the mandible and the line drawn on projecting the extension of a line drawn tangent to the alveolar bone level between the first and second molar. Point B is a point of intersection of a tangent to the inferior border of the mandible and a tangent drawn to the posterior border of the ramus of the mandible (Anatomic angle/Gonion angle). (Fig. 1). Fixation was done after passively adapting the 2 × 2 mm 4-hole with gap miniplate with 2 × 8 mm screws for Group I hemimandibles and 2 × 2 mm 4-hole 3D plate with 2 × 8 mm screws for Group II specimens (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Fracture line marking.

Fig. 2.

3D 4-hole titanium miniplate and screws and Conventional linear 4-hole titanium miniplate and screws.

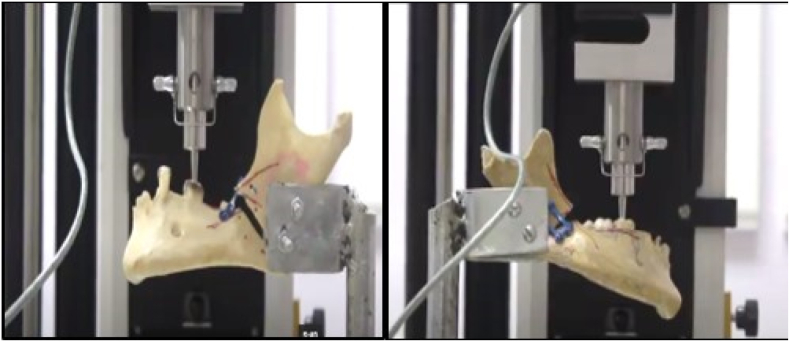

The test was performed using an Instron Corporation Series IX Automated Testing System®. In the mechanical testing, a bi-directional vertical increasing force on the hemimandible was applied with a biomechanical cantilever bending model. The specimen was fixed on a custom-made cradle in a cantilever model and loading was performed on the first molar with a crosshead speed of 3 mm per minute to obtain the parameters like the “load at break”, “displacement at maximum load” and “maximum load”. Loading was continued up to mechanical failure. The maximal load of mandibular fracture was determined and recorded in newtons. Displacement at maximal load measures the amount of vertical displacement present when mandible fracture occurs (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

After failure of fixation Group I and Group II.

3. Results

Testing of the two groups was performed following the proposed protocol. Load readings in Newtons were obtained for each sample in the mandibular angle fracture groups at the moment that rod displacement reached failure. The maximum load values (N) were obtained for the moment when the system still supported the load, but beyond which its resistance started to decrease showing that fixation failure had occurred.

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD, Median (Inter Quartile Range). Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative parameters between methods. For all statistical interpretations, p < 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed by using a statistical software package SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 20.0.

The results in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 show that the values obtained in the study presented considerable differences between the two groups. Data on maximum load are presented in Table II. When force was applied, Group - I showed greater mean maximum load values of 174.93 ± 54.45 and load at break of 151.17 ± 62.32 N compared to group II which recorded a mean maximum load value of 106.96 N ± 23.86 (Table II) and load at break of 93.45 ± 26.34 (Table III). The difference was found to be statistically significant with the p-value < 0.01 for the maximum load recorded in each group. The data on displacement (Table IV) indicated that on application of load, group - I showed greater displacement than group- II. The mean displacement recorded in group –I was 20.79 ± 5.14 at mean maximum load of while that recorded in group-II was 16 ± 3.75 at mean maximum load.

Table 2.

Comparison of Maximum Load(N) between 3D miniplates and conventional plates.

| Method | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Z# | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional miniplates | 174.93 ± 54.45 | 160.4 (140.71–216.4) | 2.4* | 0.0163 |

| 3D miniplates | 106.96 ± 23.86 | 97.27 (86.33–132.42) |

Table 3.

Comparison of Load at break (N) between 3D miniplates and conventional plates.

| Method | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Z# | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional miniplates | 151.17 ± 62.32 | 133.1 (105.91–205.46) | 1.78 | 0.0758 |

| 3D miniplates | 93.45 ± 26.34 | 89.53 (68.73–120.13) |

Table 4.

Comparison of Displacement at maximum load (mm) between 3D miniplates and conventional plates.

| Method | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Za | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional miniplates | 20.79 ± 5.14 | 19.1 (17.16–25.28) | 1.57 | 0.1172 |

| 3D miniplates | 16 ± 3.75 | 16.65 (12.22–19.46) |

Mann-Whitney U Test.

4. Discussion

Mechanical testing is one of the most efficacious means of evaluating osteosynthesis construct strength, revealing results that may suggest methods for clinical application.

Our investigation was completed in line with the established protocol. Five cadaveric specimens of human mandibles were obtained. Variables such as stabilization of mandible, orientation and path of a mandibular angle fracture line, fixation technique and measuring units were standardized.

According to the literature the ideal material for biomechanical loading tests is human mandibular bone.4 Synthetic human mandibles constituted of polyurethane have also been used by some investigators.5Although there exists some limitations in cadaveric human mandibles like standardisation of age of the specimen, the geographical or racial distribution of specimens being studied, degree of mineralisation and any chemical or caustic treatment subjected to obtain the dry mandible, these factors could not be ascertained but were not variables as the comparison was made among the two halves of the same mandible with a sample size of ten.

Mandibular angle fractures (MAFs) are biomechanically complex because they disrupt the main stress-bearing pathways in the mandible. Fracture line stability is considered one of the most important factors that determine clinical outcome. The choice of a linear section for mimicking the fracture was based on the fact that the both the Champy method and the grid plates are indicated for this type of fracture (Champy et al., 19756; Jain et al., 20107).

Load at break or yield load is the load at which a system fails. In all cases, the region around the screw hole yielded significantly. In contrast to what we hypothesized, the 3D miniplate's mean breaking load was significantly lower than the conventional miniplate. The tension band plating at the external oblique ridge stood the test of time which may be attributed to Champy's Line of osteosynthesis. The stability of single miniplate fixation of angle fractures was challenged by several biomechanical studies based on 3D models. According to Ellis,8 when a mandible angle fracture was treated with 3 different methods, the use of 1 single straight plate was the easiest plating technique with fewer complications, if indicated correctly. Using a randomized clinical trial, Jain et al.7 compared Champy's single plate at external oblique ridge technique with grid plates at the angle of mandible, describing their advantages and disadvantages. Straight plates had superior results and were easier to apply. Based on the applied methodology, Pereira-Filho VA et al. 9concluded that compared to single plates.at corresponding line of osteosynthesis, the grid plates are more susceptible to vertical displacement and that the resistance of the grid plates is unaffected by increasing the number of screws from four to eight.

In the present parameters, the maximum load of titanium conventional mini plates recorded in our study was 174.93 ± 54.45 whereas that of titanium 3D mini plates is 106.96 ± 23.86 which was of significant difference with a p-value of 0.01. The load at break and displacement at maximum load recorded, however, shows no significant difference statistically between the two plating systems/configurations.

According to Fedok et al.,10 at the first and sixth weeks after treatment of fractures of the angle,10 vertical bite forces were 31% and 52% of molar forces. In light of these findings, it is evident that the vertical forces applied in vitro studies were greater than the bite forces in patients with fractures of the mandibular angle.

Shetty et al. 11compared mandibular angle fractures fixation techniques on 6 sets of mandibular analog subjecting it to ipsilateral and contralateral occlusal unidirectional loading. A comparison of methods revealed that Champy's single plating over external oblique ridge had the resistant of the lowest bar although very reliable in clinical experiences. The mechanical testing by Feledy et al.12 compared unidirectional vertical load on grid plates and conventional miniplates for angle fractures of mandible showed remarkable stability and increased resistance in grid. Similarly in this study, the values suggest that although the threshold value of the load at break is demonstrated more in Group I, the maximum displacement as well is seen to be more in Group I. 3D plates demonstrated more resistance to displacement over the load strength of conventional mini plates at the external oblique ridge. As demonstrated in Alkan et al.,12 the 8-hole grid plates used on the mandibular angle fractures of sheep hemimandibles, at the neutral zone proved superior to a single straight plate used according to Champy's technique; however, it was inferior to the application of two plates. Recently, Al-Moraissi et al.13 conducted a meta-analysis that included only three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and three retrospective studies each published in 2012–2013, containing a relatively small sample size. Further research is needed to evaluate the differences in postoperative complications rates between these two techniques reliably.

Despite various studies comparing the effectiveness of the 3D plate with the standard miniplate in the management of angle fractures of mandibles and comparing fixation methods for angle fractures of mandibles, the optimum treatment method was not identified as a result of variable study designs, smaller sample sizes and other such factors. Our study is unique and novel in such a way that we are comparing the simplest form of angle fracture fixation versus 3D miniplate, a relatively newer introduction in terms of configuration and geometric advantage in force dissipation, as an in-vitro study on Human dry cadaveric mandibles. In Champy's line alignment as with conventional miniplate systems, there was no tensile stress transmission at the upper part, as it was re-joined through screws to move along the section. A plate screwed at the lower border, off the line of osteosynthesis does not re-establish the stress distribution existing before the section.2

Comparison of mechanical resistance between grid plates and conventional straight miniplate proved significant superiority of the latter, a result evidently different from the studies by the likes of Shetty et al., Feledy et al. and Alkan et al. The results of our study also were in contrast with Farmand's3 results. This observation is more of a factor dependent upon the position of plate placement despite the latter being acclaimed to have superior mechanics and geometric design. In this study, however, only the vertical loading forces were verified and assessed, with no addition of lateral or torsional forces. The lateral or torsional forces would possibly improve the performance of the grid plates. The proximity of vertical load with respect to fracture line was also a factor variable in-vitro studies, like those of contralateral or ipsilateral molar loading and even incisal loading in some studies. Rudderman and colleagues14 have also offered biomechanical explanations for the success of a single miniplate used to treat fractures of the mandibular angle. They feel that forces are not only distributed through the bones and fixation devices, but also through the soft tissues, creating circuits of force. Such a model explains why a single miniplate can be very successful in the management of fracture through the angle of the mandible.

Most studies were conducted mainly on polyurethane models, wherein the configuration is more homogenous or on the animal mandible, where the vagaries of anatomic variation are not completely taken into consideration. Comparing the animal mandible to the human mandible, the osteosynthesis lines and the trajectory of force are different.15 We compared hemimandibles from the same specimen in the two groups, so that the bias of variability between mandibles is eliminated, resulting in an appropriate choice of model.

5. Conclusion

In our study, the mechanical resistance to maximal load was less in 3D plate when compared to a single straight miniplate plated according to Champy's line of osteosynthesis. In vitro models and experimental setup, there is a limited ability to create conclusions angle fractures, like utilized in this study. It is not directly applicable to in vivo situations. A clinical study follows up of this biomechanical study with a larger sample size and meta-analysis of such researches can help curtail this controversy in the management of angle fractures of the mandible, which persists today among some surgeons.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Mathew Tharakan, Email: drcamt@gmail.com.

Surej Kumar L K, Email: surejkumarlk@gmail.com.

Meghna Chandrachood, Email: meghnachandrachood@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Michelet F.X., Dimes J., Dessus B. Osteosynthesis with miniaturized screwed plates in maxillo-facial surgery. J Maxillofac Surg. 1973;1:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(73)80017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champy M., Wilk A., Schnebelen J.M. Treatment of mandibular fractures by means of osteosynthesis without intermaxillary immobilization according to F.X. Michelet's technic. Zahn Mund Kieferheilkd Zentralbl. 1975;63:339–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmand M., Dupoirieux L. The value of 3-dimensional plates in maxillofacial surgery. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1992;93:353–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jambhulkar M, Gupta S, Gupta H, Mohammad S. Study of Comparison of Bite Force between Conventional and 3D Miniplate in Mandibular Fractures.

- 5.Bredbenner T.L., Haug R.H. Substitutes for human cadaveric bone in maxillofacial rigid fixation research. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:574. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champy M., Loddé J.P., Schmitt R., Jaeger J.H., Muster D. Mandibular osteosynthesis by miniature screwed plates via a buccal approach. J Maxillofac Surg. 1978;6:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(78)80062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain MK, Manjunath KS, Bhagwan BK, et al. Comparison of 3 dimensional and standard miniplate fixation in the management of mandibular fractures. JOralMaxillofacSurg2010; 68:1568–1572. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ellis E. A prospective study of 3 treatment methods for isolated fractures of the mandibular angle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2743–2754. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira-Filho V.A., de Gorla Oliveira L.F., Reis J.M., Gabrielli M.A., Neto R.S., Monnazzi M.S. Evaluation of three different osteosynthesis methods for mandibular angle fractures: vertical load test. J Craniofac Surg. 2016 Oct 1;27(7):1770–1773. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedok F.G., Van Kooten D.W., DeJoseph L.M., et al. Plating techniques and plate orientation in repair of mandibular angle fractures: an in vitro study. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1218–1224. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199808000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shetty V., McBrearty D., Fourney M., et al. Fracture line stability as a function of the internal fixation system: an in vitro comparison using a mandibular angle fracture model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:791–801. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feledy J., Caterson E.J., Steger S., et al. Treatment of mandibular angle fractures with a matrix miniplate: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1711–1716. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000142477.77232.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Moraissi E.À., El -Sharkawy T.M., El -Ghareeb T.I., Chrcanovic B.R. Three -dimensional versus standard miniplate fixation in the management of mandibular angle fractures: a systematic review and meta -analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43(6):708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudderman R.H., Mullen R.L., Phillips J.H., et al. The biophysics of mandibular fractures: an evolution toward understanding. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:596–607. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000297646.86919.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sittitavornwong S., Ashley D., Denson D., et al. Assessment of the integrity of Adult human mandibular angle. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction Open. 2019 Jan;3(1):s-0038. [Google Scholar]