Abstract

Rhizobium leguminosarum secretes two extracellular glycanases, PlyA and PlyB, that can degrade exopolysaccharide (EPS) and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), which is used as a model substrate of plant cell wall cellulose polymers. When grown on agar medium, CMC degradation occurred only directly below colonies of R. leguminosarum, suggesting that the enzymes remain attached to the bacteria. Unexpectedly, when a PlyA-PlyB-secreting colony was grown in close proximity to mutants unable to produce or secrete PlyA and PlyB, CMC degradation occurred below that part of the mutant colonies closest to the wild type. There was no CMC degradation in the region between the colonies. By growing PlyB-secreting colonies on a lawn of CMC-nondegrading mutants, we could observe a halo of CMC degradation around the colony. Using various mutant strains, we demonstrate that PlyB diffuses beyond the edge of the colony but does not degrade CMC unless it is in contact with the appropriate colony surface. PlyA appears to remain attached to the cells since no such diffusion of PlyA activity was observed. EPS defective mutants could secrete both PlyA and PlyB, but these enzymes were inactive unless they came into contact with an EPS+ strain, indicating that EPS is required for activation of PlyA and PlyB. However, we were unable to activate CMC degradation with a crude EPS fraction, indicating that activation of CMC degradation may require an intermediate in EPS biosynthesis. Transfer of PlyB to Agrobacterium tumefaciens enabled it to degrade CMC, but this was only observed if it was grown on a lawn of R. leguminosarum. This indicates that the surface of A. tumefaciens is inappropriate to activate CMC degradation by PlyB. Analysis of CMC degradation by other rhizobia suggests that activation of secreted glycanases by surface components may occur in other species.

Nodule morphogenesis on the roots of leguminous plants can be induced by chemical signaling molecules made by rhizobia. These morphogenetic signals (Nod factors) are oligomers of (usually four or five) β,1-4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues carrying an N-linked fatty acyl group on the terminal (nonreducing) sugar (8, 11). In several legumes, nodule morphogenesis can be induced by the purified signals in the absence of any bacteria (8, 11). For a successful symbiosis to be established between rhizobia and legumes, it is also necessary for the bacteria to invade the plant root. Invasion usually occurs via infection threads, which are intracellular tunnels made as a result of plant cell walls laid down within the cytoplasm of root hair epidermal and cortical cells. Although Nod factors induce the production of “cytoplasmic bridges,” intracellular structures thought to be precursors of the infection threads, the presence of bacteria is necessary for development of infection threads (46). Invasion is a clonal event, and the rhizobia grow at the tip of the infection thread; it is this growth (rather than bacterial migration) that enables the bacteria to reach the growing nodule meristem (16). The bacteria are released into nodule cells where they differentiate and induce those genes required for nitrogen fixation.

Selectivity during this infection process is important because it is crucial for the plant to exclude other potential invasive bacteria. Therefore, there are several checks and balances required to ensure that invasion is limited to the appropriate bacteria. It is evident that Nod factors play a role in recognition during invasion since bacterial mutants that make Nod factors, lacking host specific modifications, are unable to infect normally (1). There are several other factors that are necessary for infection. In some rhizobia there is clear evidence for a role for the secreted signaling protein NodO (13, 49) that forms cation-selective pores in membranes and has been proposed to act on the plant plasma membrane (42). It appears that at least in some situations NodO plays a role in the establishment of infection events (20). NodO is secreted via a type I protein secretion system encoded by prsD and prsE (14, 15), which also secretes enzymes involved in processing of the bacterial exopolysaccharide (EPS). The EPS is essential for invasion. Rhizobial mutants lacking EPS cannot invade (29). In some cases addition a low-molecular-weight fraction of an EPS-derived oligosaccharide can restore infection to EPS-deficient mutants, suggesting a signaling process (2, 10, 18). The role of EPS in infection is not well understood, although it does appear it may be required for maturation and elongation of infection threads (7). One proposal is that there may be a role for specific EPS fragments in suppressing plant defense responses during infection (34).

Low-molecular-weight EPS is produced in Rhizobium meliloti by two processes, a specific biosynthetic route and cleavage of a higher-molecular-weight form (19). A type I secretion system (encoded by the prsDE genes) is required for the secretion of the EPS-cleaving enzymes ExoK and ExsH (50), and PlyA and PlyB of R. leguminosarum are secreted similarly (14, 15). The mature EPS of R. meliloti is not cleaved by the ExoK and ExsH glycanases; these enzymes cleave nascent EPS chains (52), and the absence of the succinyl group decreased the susceptibility of succinoglycan to cleavage (51). It is not known if modification of the R. leguminosarum EPS confers resistance to cleavage by PlyA and/or PlyB.

The PlyA and PlyB glycanases from R. leguminosarum are not specific for the EPS polymer but can also degrade carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). These enzymes appeared to remain cell bound (14, 15) because degradation of CMC or EPS incorporated into agar plates only occurred directly below the colony and there was no halo of degradation beyond the colony, as is usually seen with many other enzymes secreted via type I secretion systems. Several groups have analyzed cellulases produced by rhizobia because many of the observations of infection appear to involve degradation of the plant cell wall (5, 21, 30, 39, 45). However, there was little or no cellulase activity in a cell-free culture supernatant from R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii (24, 33). These observations, together with the absence of a halo of CMC degradation around colonies of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae grown on CMC-containing plates, suggested that the CMC-degrading activity secreted via type I secretion system remains cell bound (15). In this study we demonstrate that CMC-degrading activity is released from the cell surface but is inactive. Activation only occurs when contact is made with the bacteria. This activation is specific for the cell surface and the enzymes secreted by R. leguminosarum cannot be activated by the surfaces of other species of rhizobia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbiological methods.

Rhizobium spp. were grown at 28°C in TY medium (3) with appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations (μg/ml): streptomycin, 400; kanamycin, 20; spectinomycin, 20; tetracycline, 10; lividomycin, 5. For polysaccharide preparation, bacteria were grown in Y medium (41) containing mannitol (0.2% [wt/vol]). Culture optical densities were measured at 600 nm with an MSE Spectro-Plus spectrophotometer. The bacterial strains and plasmids used are described in Table 1. Plasmids were transferred to Rhizobium spp. by triparental mating with a helper plasmid.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae isogenic strains | ||

| 8401 | R. leguminosarum lacking pSym, Strr | 28 |

| 8401/pRL1JI | Derivative of 8401 carrying the symbiotic plasmid pRL1JI | 12 |

| A168 | 8401/pRL1JI pssA1::Tn5 | 4 |

| A412 | 8401/pRL1JI prsD1::Tn5 | 14 |

| A507 | 8401/pRL1JI pss5::Tn5 | This work |

| A517 | 8401/pRL1JI pss6::Tn5 | This work |

| A550 | 8401/pRL1JI ΔplyA-prs-pss::nptII | This work |

| A600 | 8401/pRL1JI plyB1::Tn5 | 15 |

| A638 | 8401/pRL1JI plyA3::Spcr | 15 |

| A640 | 8401/pRL1JI plyA3::SpcrplyB1::Tn5 | 15 |

| Other strains | ||

| 1021 | R. meliloti | S. Long |

| 3855 | R. leguminosarum bv. viciae | 25 |

| ANU843 | R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii | 9 |

| ANU2840 | Tn5-induced EPS− mutant of ANU280 (Smr Rifr derivative of NGR234) | 6 |

| C58C1 | A. tumefaciens | 47 |

| CE3 | R. etli | 35 |

| CIAT899 | R. tropici | 32 |

| NZP2213 | R. loti | DSIR Culture Collection |

| RCR5 | R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii | 22 |

| Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 | Broad-host-range Rhizobium sp. | 44 |

| USDA193 | S. fredii | USDA-ARS National Rhizobium Culture Collection |

| VF39 | R. leguminosarum bv. viciae | 37 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ7298 | pLAFR1 cosmid carrying prsDE and plyA | 14 |

| pIJ7471 | HindIII deletion of pIJ7298 with the kanamycin resistance gene from Tn5 on a 3.4-kb HindIII fragment | This work |

| pIJ7709 | plyB cloned in pIJ1891 | 15 |

| pIJ7871 | plyA cloned behind a vector promoter in pKT230 | 15 |

| pRGC1 | pLAFR1 cosmid carrying the egl endoglycanase gene from A. caulinodans | 17 |

Construction of EPS mutants.

Plasmid pIJ7298 carries the polysaccharide synthesis genes pssFCDE linked to the protein secretion genes prsDE and the glycanase gene plyA (15). The EPS mutant strains A507 and A517 were generated by first mutagenizing pIJ7298 with Tn5. Several Tn5-containing derivatives of pIJ7298 were transferred to 8401/pRL1JI, and the Tn5 insertions were recombined into the genome by homologous recombination selecting for marker exchange as described previously (40). Two of the Tn5 mutations caused an EPS− phenotype when they were marker exchanged to make strains A507 and A517. The mutations in A507 and A517 were mapped 1.8 and 8.6 kb upstream of the start of pssF in what is thought to be a large cluster of genes required for EPS synthesis. To generate a mutant lacking both the prsDE secretion genes and the pss gene region, a deletion mutant was constructed. pIJ7298 carrying the prsDE and pssFCDE genes (15) was digested with HindIII. This results in the deletion of about 20 kb of DNA including prsDE, pssFCDE, and other unidentified EPS biosynthetic genes (see above) and leaves about 2 kb of DNA upstream of prsD and about 6 kb of DNA downstream of the pss gene cluster. The 3.4-kb HindIII fragment from Tn5 carrying nptII was cloned into the deleted derivative of pIJ7298 to form pIJ7471. The deletion allele was recombined into the genome of 8401/pRL1JI by marker exchange by using plasmid pPH1JI to select for recombinants essentially as described previously (40). A kanamycin-resistant, tetracycline-sensitive mutant was selected and called A550. This strain is EPS− and was confirmed to be defective for protein secretion by testing for the secretion of NodO as described previously (14). The mutant behaved as expected, in that it was complemented for protein secretion by pIJ7298, but not by the HindIII deleted derivative of it (pIJ7471) used to make the mutant.

Plate assays.

CMC was incorporated into the Y–0.2% mannitol agar plates at 0.1%. Colonies were grown for 3 days at 28°C and washed off with water. The plates were then flooded with 0.1% (wt/vol) Congo red in water (43) for 15 min, washed for 10 min with 1 M NaCl, and then washed for 5 min with 5% acetic acid. Degradation of CMC was observed as clearings (reduction of staining). To prepare a CMC plate containing a bacterial lawn, a sterile cotton tipped rod was dipped in a liquid suspension containing about 107 CFU/ml and used to spread a layer on the agar. To test the effect of a bacterial lawn on the ability of colonies to degrade CMC, 10 μl of a bacterial suspension (ca. 107 CFU/ml) was loaded on a plate to form a homogeneous colony. The plates were then incubated at 28°C for 4 days. For detection of EPS degradation activity, EPS was precipitated from a 5 days of culture of 8401/pRL1JI with 3 volumes of ethanol and then redissolved in sterile deionized water. The EPS was incorporated into Y-agar plates at about 2 mg/ml. Assays of EPS degradation by colonies and colonies grown on lawns was as described above for CMC degradation except that the plates were incubated for 2 days and the wash with 1 M NaCl was omitted.

RESULTS

Identification of diffusible glycanase activity.

R. leguminosarum bv. viciae produces two glycanases that are secreted in a prsD-dependent way. They were called PlyA and PlyB and are somewhat unusual because, although they are fully secreted, they appeared to remain attached to the bacterial cell surface. Generally, when bacterial proteins are secreted via a type I secretion system, the activity of the secreted protein (e.g., hemolysins, proteases, or lipases) can be detected beyond the area of growth of colonies grown on the appropriate indicator agar medium. This results in the formation of a “halo” of clearing of an appropriate substrate such as the lysis of red blood cells by hemolysin or degradation of milk proteins by secreted proteases.

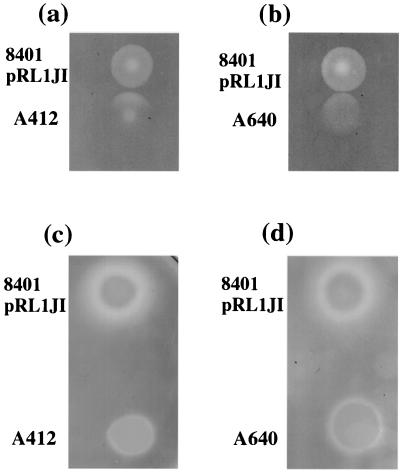

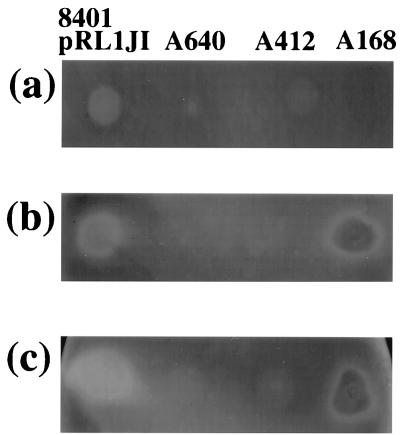

Although PlyA and PlyB are secreted by a typical type I secretion system (14, 15) and cleave the substrate CMC, the zone of CMC degradation with the wild-type strain 8401/pRL1JI does not extend beyond the edge of the colony (Fig. 1a). The protein secretion (prsD) mutant A412 does not induce such CMC degradation because neither PlyA or PlyB (the major enzymes that cleave CMC) are secreted. However, when we grew a colony of the prsD mutant (A412) in close proximity to the wild-type parent (8401/pRL1JI) a small zone of CMC cleavage could be detected below that part of the mutant colony which was closest to the colony of the wild type (Fig. 1a). Initially, we assumed that the partial zone of clearing below A412 was caused by cell lysis of A412, resulting in the release of PlyA and PlyB; this could, for example, have been caused by secretion of a bacteriocin or some other factor from 8401/pRL1JI. However, strain 8401 (lacking the indigenous plasmid pRL1JI, which carries the gene encoding bacteriocin), also activated CMC degradation below the colony of A412 (Table 2), demonstrating that it was not the bacteriocin that caused this effect.

FIG. 1.

Activation of glycanase by cells of mutants defective for extracellular glycanase production. In panels a and b, colonies of strain 8401/pRL1JI were grown adjacent to the protein secretion mutant A412 (prsD) or the glycanase mutant A640 (plyA plyB); the cells were grown for 3 days on Y medium containing CMC. In panels c and d, these strains were grown on the same medium that had been seeded with a lawn of A412 and incubated for 4 days. After growth, the cells were washed off, and the plates were stained with Congo red; the unstained regions correspond to areas where the CMC has been degraded.

TABLE 2.

Induction of a clearing on neighboring colonies

| Donor | Indicator | CMC degradation induced below adjacent indicator colony |

|---|---|---|

| 8401/pRL1JI | A412 (prsD) | + |

| 8401 | A412 (prsD) | + |

| 8401/pRL1JI | A640 (plyA plyB) | + |

| A168 (pssA) | A412 (prsD) | + |

| A550 (Δprs Δpss) | A412 (prsD) | − |

| 8401/pRL1JI | A168 (pssA) | − |

To determine if the induced degradation was related to release of PlyA or PlyB, we carried out a similar test using a plyA plyB double mutant (A640) grown adjacent to 8401/pRL1JI. We saw enhanced degradation below the colony of A640 in the zone closest to the colony of 8401/pRL1JI (Fig. 1b). This demonstrates that the cleavage of CMC induced by 8401/pRL1JI under the adjacent colony cannot be due to release of PlyA or PlyB following cell lysis. An alternative explanation is that PlyA and/or PlyB secreted by the wild-type strain could be present as a halo around the 8401/pRL1JI colony but that CMC degradation is not activated unless the secreted glycanase is in direct contact with the colony. Such a model could account for the lack of CMC degradation in the zones between the colonies (Fig. 1a and b).

If such a model holds true, it should be possible to demonstrate the presence of a halo of CMC degradation beyond the edge of the colony by activating the secreted enzyme. We devised an assay to test this; the prsD secretion mutant (A412) was inoculated as a lawn onto the CMC agar, and then strain 8401/pRL1JI was grown as a colony on the surface of the agar. This resulted in a clear halo of CMC degradation (Fig. 1c). With colonies of the prsD mutant A412 and the plyA plyB double mutant A640 grown on a lawn of A412, there was not a halo of CMC degradation typical of that seen with 8401/pRL1JI (Fig. 1c and d). When the lawn of A412 (prsD) was replaced with a lawn of A640 (plyA plyB), we also observed clear evidence of a halo of degradation around colonies of 8401/pRL1JI but not A412 or A640 (data not shown). These observations indicate that the halo around 8401/pRL1JI is due to the secretion of PlyA and/or PlyB.

Whereas there is very little CMC degradation below colonies of A640 or A412 grown alone, some CMC degradation is seen when these colonies are grown on a lawn of A412 (Fig. 1c and d) or A640 (data not shown), and this was somewhat enhanced at the perimeter of the colony. We are not sure as to why such an effect is seen only when these mutants are grown on a lawn of A412. It may be related to the fact that A412 itself can induce some CMC degradation as seen in the center of the colony of A412 in Fig. 1a. This CMC degradation may be due to lysis of some cells in the A412 lawn, resulting in the release of glycanases. Alternatively, this degradation could be due to the presence of another glycanase that has not yet been identified, but which accumulates as colonies get older. Even with the double mutant A640 we observe some CMC degradation (see, for example, Fig. 6a) which increases with time of incubation.

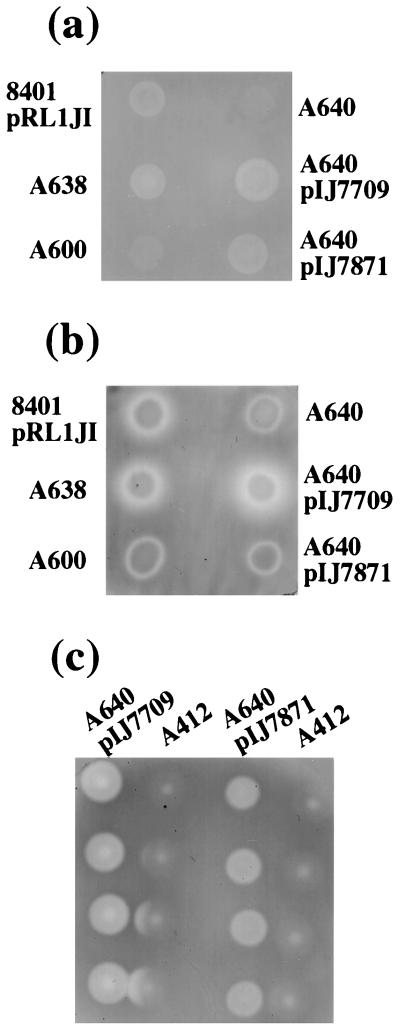

FIG. 6.

plyB but not plyA encodes a diffusible glycanase. CMC degradation was assayed using CMC-agar (a and c) or CMC agar seeded with a lawn of the protein secretion mutant A412 (b). Growth and staining were as in Fig. 1. The strains used are the parental strain 8401/pRL1JI and its derivatives carrying mutations in plyA (A638), plyB (A600), or both plyA and plyB (A640) and A640 derivatives carrying cloned plyA (on pIJ7871) or plyB (on pIJ7709). In panel c, the A640 cells carrying cloned plyA or plyB were cultured at various distances from A412 to get a measure of the relative distance of cross activation by PlyB.

EPS mutants do not activate CMC degradation.

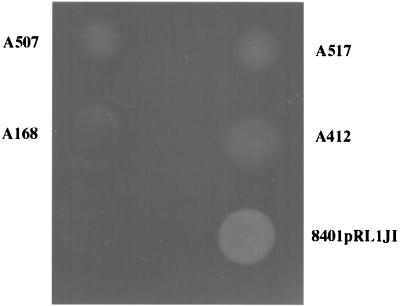

One of the substrates of PlyA and PlyB is the EPS, and we thought it possible that the EPS might activate PlyA and/or PlyB to degrade CMC. A simple prediction of such a model is that mutants defective for EPS production should be defective for CMC degradation even under the zone of colony growth. We tested several different EPS-deficient mutants for their ability to cleave CMC. As shown (Fig. 2), they are all significantly affected in their ability to degrade CMC. The mutant (A168), which was most severely affected for EPS production, carries a mutation in the pssA gene that encodes the first glycosyl transferase required for EPS biosynthesis (4, 23, 48). As shown (Fig. 2), this mutant has a very low background of CMC degradation similar to that seen with the secretion mutant A412. Other EPS mutants affected in EPS formation are also affected for CMC degradation (Fig. 2), although the pssA mutant seemed to be slightly more defective for CMC degradation than the other mutants. These observations suggest that the EPS plays a role in activation of CMC degradation by the secreted glycanases. However, this experiment does not eliminate the alternative explanation, that EPS mutants might be defective for secretion of PlyA and PlyB. We tested for secretion of these glycanases by growing a colony of the EPS mutant A168 (pssA) adjacent to a colony of the prsD secretion mutant A412. This cross-feeding resulted in activation of CMC degradation below the colony of A412 (Fig. 3). As a control we made a mutant (A550) that is defective for both protein secretion and for EPS production; this mutant (A550) induced no degradation below the adjacent colony of A412 (Fig. 3 and Table 2).

FIG. 2.

EPS− mutants are defective for CMC degradation. Growth and staining conditions were as in Fig. 1a and b. The EPS-defective mutants A168, A507, and A517 have much less CMC degradation than their parent 8401/pRL1JI and have similar or lower levels of CMC degradation than the glycanase secretion mutant A412.

FIG. 3.

The EPS-deficient mutant A168 can induce CMC degradation below an adjacent (EPS+) colony. Growth and staining conditions were as in Fig. 1a and b. Strain A168 produces no EPS, and A550 is defective for both EPS production and protein secretion. A168 but not A550 induced CMC degradation below part of the adjacent colony of the secretion mutant A412.

The secretion of CMC-degrading enzymes by the EPS mutant A168 can also be demonstrated by growing a lawn of the prsD mutant on CMC agar and then inoculating the EPS− mutant as a colony. In this case (Fig. 4b), the halo produced by the pssA mutant (A168) is similar to that produced by the control 8401/pRL1JI. This can be explained if the glycanase is secreted by A168 but is inactive for CMC degradation, unless there are EPS+ cells present (i.e., A412 in the lawn) (Fig. 4a and b). The observation that the plyA plyB double mutant, A640, does not form a diffusible halo (Fig. 1d) demonstrates that the halo of degradation is due to PlyA and/or PlyB. Similar observations to those in Fig. 4b were seen if the lawn was formed by A640 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cross-stimulation of glycanase activity among EPS−, glycanase secretion, and glycanase-defective mutants. Cells, as indicated, were grown on CMC-agar (a), CMC-agar seeded with a lawn of the secretion mutant A412 (prsD) (b), and CMC-agar seeded with the EPS− mutant A168 (pssA) (c). Growth and staining was as described for Fig. 1.

If the EPS defective mutant, A168, is grown as a lawn on the agar, typical CMC degradation is seen under a colony of 8401/pRL1JI, but there is no halo (Fig. 4c). The absence of a halo in this case can be explained on the basis that A168, which forms the lawn, produces no EPS and therefore degradation only occurs adjacent to the EPS produced by 8401/pRL1JI, indicating that the EPS plays a role in halo formation. Similar CMC degradation was seen when the prsD secretion mutant A412 and the plyA plyB double mutant, A640, were grown on a lawn of the EPS mutant A168 (Fig. 4c). In this assay it appears that it is the (EPS) surface of the colonies of A412 or A640 that activate CMC degradation by glycanases that are produced (but are inactive) in the lawn formed by A168. In these cases, however, the zone of CMC degradation is limited to the edge of the colony and no halo is formed. This fits with the model that the surface of the mutants A412 and A640 activates CMC degradation.

The results above indicate a role for EPS in the activation of CMC degradation. We prepared a crude EPS fraction from 8401/pRL1JI and from A412 by ethanol precipitation from culture supernatants. This EPS preparation was incorporated into CMC assay plates, which were then inoculated with strains 8401/pRL1JI (WT), A168 (pssA), and the protein secretion mutant A412 (prsD) as a negative control. No halo of CMC degradation was observed around 8401/pRL1JI or A168 (data not shown), indicating that the EPS precipitated from the growth medium is insufficient to activate CMC degradation. This implies that either another factor is required for activation of CMC degradation or that some EPS component not precipitated is required for activation. The results of these experiments with EPS incorporated into plates, are consistent with our earlier observations, which demonstrated that PlyA and PlyB degrade EPS incorporated into plates, but that the zone of degradation did not extend beyond the edge of the colony (reference 15 and Fig. 5a). When we incorporated EPS into agar plates and carried out EPS degradation assays in a similar way to the CMC degradation assays described in Fig. 1c and d and Fig. 4b (with colonies inoculated on a lawn of A412 or A640), we observed halos of degradation of EPS similar to those seen with CMC (Fig. 5b and c). Also shown in Fig. 5a is the observation that the EPS− mutant (A168) is defective for EPS degradation, even though this mutant produced glycanases that can be activated by the surfaces of A412 (Fig. 5b) or A640 (Fig. 5c).

FIG. 5.

Assays of EPS degradation by glycanase, secretion, and EPS− mutants. The assays were carried out as described for CMC degradation (Fig. 1), except that EPS replaced the CMC in the agar. In panel a the colonies were grown on EPS-agar. The degradation below 8401/pRL1JI did not extend beyond the colony; there was a low level of degradation seen with the glycanase mutant A640 (plyA plyB) and the secretion mutant A412 (prsD), but none was seen with the EPS− mutant A168. In panel b the EPS-agar was seeded with a lawn of A412 (prsD), and in panel c there was a lawn of A640 (plyA plyB).

PlyB is responsible for halo formation.

Are both secreted glycanases, PlyA and PlyB, activated by the presence of EPS+ bacteria and diffusible through the agar? To answer these questions, we analyzed the ability of plyA and plyB mutants to produce halos on CMC plates containing a lawn of A412 (Fig. 6b). The plyA mutant (A638) retained activity, but the plyB mutant (A600) did not (Fig. 6), demonstrating that PlyB is responsible for most of the diffusible activity. A limitation of this assay is that plyA seemed to be relatively weakly expressed (15), and so the apparent lack of a halo of PlyA activity (in the plyB mutant) could be due to insufficient expression of plyA. To compensate for this, we used the cloned plyA gene on pIJ7871, which confers good CMC degradation to the plyA plyB mutant A640 (Fig. 6a). A640/pIJ7871 did not induce halo formation on an A412-CMC layer (Fig. 6b), indicating that PlyA probably mostly remains cell bound. We also analyzed CMC degradation below colonies of A412 (prsD) in a neighboring colony assay by using strain A640 carrying cloned plyA (pIJ7871) or plyB (pIJ7709). The results of this assay (Fig. 6c) confirm that PlyB is diffusible but PlyA is not. However, PlyA does seem to require activation by an EPS-related component because no CMC degradation was observed by the EPS− mutant A168 (pssA) even when pIJ7871 was present (not shown).

Analysis of CMC degradation by LPS mutants.

We considered the possibility that activation of CMC degradation may also involve the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) surface layer. We tested the glycanase activity of several different mutants of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae affected for LPS biosynthesis (26, 31). Of those tested, only one mutant (B659) had reduced CMC degradation. This mutant retained the ability to secrete PlyB (and probably PlyA) because when it was tested for CMC degradation using a lawn of A412, a clear halo of degradation could be detected. Therefore, only this mutant behaved in a similar way to the EPS-defective mutants. B659 is somewhat different from the other LPS mutants tested, in that both its EPS and its LPS production are affected (38). Since the other LPS mutants retained normal levels of CMC-degrading activity, we conclude that the LPS is not necessary for the activation of CMC degradation by the secreted glycanases.

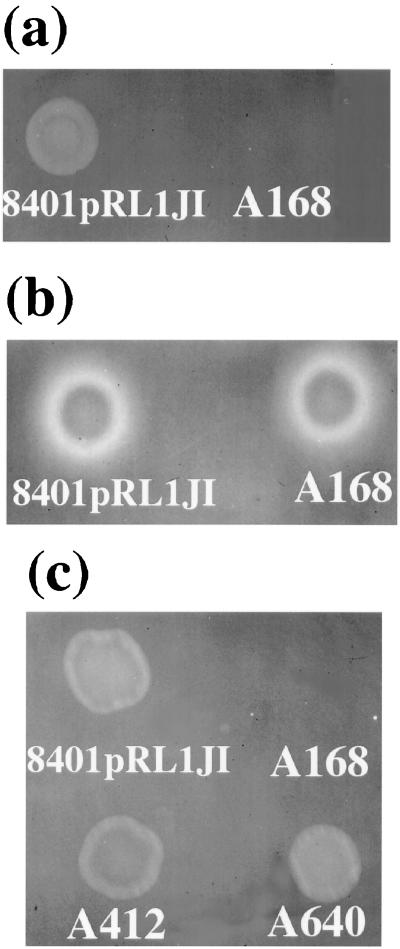

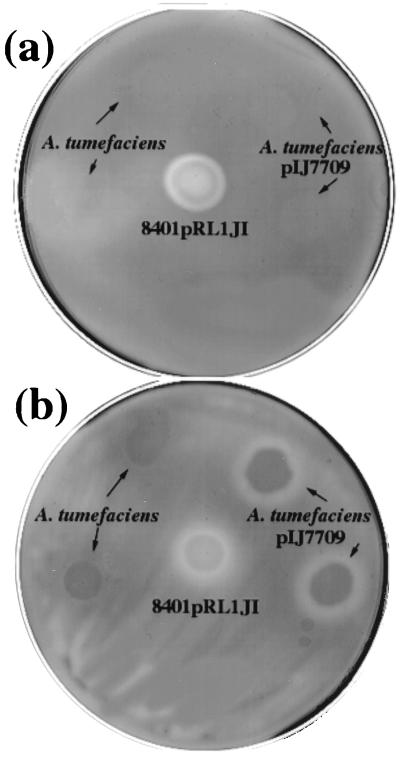

PlyB is not activated by surface oligosaccharides of related bacteria.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is closely related to R. leguminosarum, but it cannot degrade CMC (Fig. 7a). When plyB (on pIJ7709) was transferred to A. tumefaciens, the colonies remained unable to cleave CMC (Fig. 7a). An explanation for this lack of activity is that A. tumefaciens may not provide the appropriate factor that activates PlyB. When colonies of A. tumefaciens carrying pIJ7709 (plyB) were grown on CMC plates inoculated with a lawn of A412 (prsD), a halo of CMC degradation was clearly seen (Fig. 7b). Since no such CMC degradation occurred in the absence of either plyB (Fig. 7b) or added A412 (Fig. 7a), this demonstrates that PlyB can be secreted by A. tumefaciens but is inactive unless activated by the appropriate cell surface (in this case provided by A412 but not A. tumefaciens). The observation that A. tumefaciens does not induce CMC degradation enabled us to test whether the surface of this bacterium could activate PlyB. When 8401/pRL1JI was inoculated onto a CMC plate containing a lawn of A. tumefaciens no halo of CMC degradation was observed (data not shown). This reconfirms the observation that the surface of A. tumefaciens cannot activate PlyB.

FIG. 7.

plyB cloned in A. tumefaciens produces a glycanase that is not detected unless cells of R. leguminosarum are present. CMC degradation was assayed using CMC-agar (a) or CMC-agar seeded with a lawn of the protein secretion mutant A412 (b). In panel a, A. tumefaciens strain induces no CMC degradation even if it carries plyB cloned on pIJ7709, but plyB-dependent activity can be seen in panel b, where a lawn of A412 is present. Assay conditions are as described in Fig. 1.

Activation and inhibition of CMC degradation by other rhizobia.

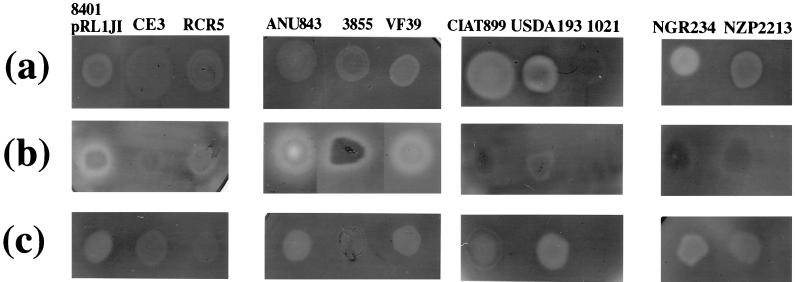

We extended the analysis of CMC degradation to other rhizobia. R. tropici CIAT899, R. fredii USDA193, and Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 induced CMC degradation at a level greater than that seen with R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 8401/pRL1JI; R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii RCR5 and ANU843, R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3855 and VF39, and R. loti NZP2213 were similar to 8401/pRL1JI; R. etli CE3 had somewhat less degradation than 8401/pRL1JI under the growth conditions tested, and R. meliloti 1021 as previously described (50) was unable to degrade CMC. In each case, CMC degradation was limited to the zone below the colony, and no halo of degradation was observed (Fig. 8a).

FIG. 8.

CMC degradation by various rhizobia. CMC degradation was assayed using CMC-agar (a), CMC-agar seeded with a lawn of the protein secretion mutant A412 (b), or CMC-agar seeded with a lawn of R. meliloti 1021 (c). The strains used are R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 8401/pRL1JI, R. etli CE3, R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii RCR5 and ANU843, R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3855 and VF39, R. tropici CIAT899, S. fredii USDA193, R. meliloti 1021, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, and R. loti NZP2213.

Since there is CMC degradation by several of these strains, we are in a position to test if there are diffusible enzymes that can be activated by the R. leguminosarum mutant A412 (prsD) that does not secrete glycanases. This was done by inoculating each strain onto a lawn of A412 on a CMC plate (Fig. 8b). As expected, R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains 3855 and VF39 produced a halo of CMC degradation, as did R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii RCR5 and ANU843. R. etli CE3 formed a weak halo that is correlated with the very low CMC degradation. None of the other strains (including R. tropici CIAT899, R. fredii USDA193, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, and R. loti NZP2213) produced a halo of CMC degradation. The absence of halos indicates that either the CMC-degrading enzymes produced by these strains are not released from the surface or that they are released but are inactive and are not activated by the surface of R. leguminosarum. In the absence of derivatives of these various strains defective for glycanase production or secretion, it is difficult to unambiguously determine whether the extracellular glycanase activity is only active if the appropriate cell surface is present. However, EPS-deficient mutants of NGR234 have been described (6). One such mutant (ANU2840), blocked in an early stage of EPS biosynthesis, was tested to determine if loss of EPS production in this strain is associated with loss of CMC degradation. No CMC degradation was observed directly below the colony, indicating that CMC degradation by NGR234 is activated by an EPS-related component. In contrast, the cloned endoglycanase egl gene (on pRGC1) from Azorhizobium caulinodans was transferred into the exopolysaccharide defective mutant of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae; a high level of CMC degradation was observed indicating that this glycanase is not activated by EPS.

We also tested if the surface of R. meliloti (which induces no CMC degradation) is able to replace the surface of A412 to activate glycanases by inoculating each strain on a CMC plate containing a lawn of R. meliloti. In this case, no halo of CMC degradation was observed around the colonies of all tested strains (Fig. 8c).

During the course of analysis of CMC degradation by various strains, we observed that R. leguminosarum bv. viciae A412 (prsD) strongly reduced CMC degradation below the colonies of those strains that could degrade CMC (Fig. 8b). This is most obvious with R. tropici CIAT899, R. fredii USDA193, and Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, which normally induce very strong CMC degradation (Fig. 8a). This mirrors the observation made with A. tumefaciens carrying PlyB (pIJ7709); this strain induces a halo of CMC degradation (Fig. 7b) caused by secreted PlyB, but there is little CMC degradation below the colony, indicating that PlyB activity may be inhibited by the surface of A. tumefaciens. A similar effect was seen with the EPS-deficient mutant (A168) of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae grown on a lawn of A412 (Fig. 4b).

DISCUSSION

Previously, Finnie et al. (15) concluded that the secreted glycanases encoded by plyA and plyB remain attached to the surface of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. This conclusion was drawn on the basis of the absence of CMC or EPS cleavage beyond the edge of agar colonies and was consistent with reports by others (24, 33) that there is cell-associated cellulase activity in different rhizobia, but there are extremely low levels of activity in the culture supernatants of strains that have cell-associated cellulase activity. The observations described here demonstrate that, at least for PlyB, our earlier conclusions are incorrect because PlyB is secreted and diffuses away from the cells but is inactive unless it is in contact with the cell surface. It is evident that some component associated with EPS biosynthesis is necessary for activation of PlyB since the EPS-defective mutants cannot induce activation. We were unable to activate PlyB with an ethanol-precipitated preparation of EPS, indicating that the mature EPS does not induce the activation. This result fits with our previous observation that colonies of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae grown on agar containing EPS can degrade the EPS below the colony, but there is no halo of EPS degradation extending beyond the edge of the colony. These observations are consistent with a model in which nascent EPS or an intermediate in EPS biosynthesis activates PlyB to cleave both CMC and EPS. Recent work with R. meliloti is pertinent to this point. The mature succinoglycan of R. meliloti is not cleaved by the secreted glycanases ExoK and ExsH (52). It was recently demonstrated that the levels of succinylation and acetylation strongly influence the susceptibility of nascent succinoglycan to glycanases (51). In light of the observations described here, there may be a possible alternative explanation of the observations made with R. meliloti, namely, that the mature succinoglycan can be cleaved but only, for example, if the glycanase is activated by an immature succinoglycan component.

The R. leguminosarum bv. viciae plyA gene product seems to behave somewhat differently from PlyB in that we did not observe CMC-degrading activity beyond the edge of the colony under any of the situations tested. Nevertheless, PlyA behaves like PlyB in that it is inactive in EPS-defective mutants and can be activated by the surface of glycanase-nonsecreting strains that make EPS. PlyA and PlyB are 71% identical, but PlyA contains an extra 50 amino acids near the C-terminal domain which could play a role in maintaining PlyA attachment to the cell surface.

Why should the glycanases PlyA and PlyB only be active in association with the rhizobial cell surface? This begs the question as to what their primary role or roles are in the life cycle of Rhizobium spp. One of the roles could be to cleave strands of EPS, which otherwise might be so long that they could impede bacterial movement. The observations presented here suggest a mechanism of limiting the degree of EPS degradation, if only those enzymes adjacent to the cell surface could cleave the mature EPS. Therefore, the EPS capsule, which may protect the bacteria from environmental stresses, would not be greatly degraded by glycanases released from the cell surface.

Since these glycanases have the ability to degrade CMC, they could in theory degrade cellulose-based polymers in plant cell walls. Could such degradative activity account in part for the observed degradation of legume root cell walls adjacent to the growth of rhizobia (5, 21, 30, 39, 45)? The observations that the glycanase activation can be species specific and that similar EPS-dependent activation occurs with Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 may suggest a role in invasion. However, the observation that prsD secretion mutants of R. leguminosarum biovars viciae and trifolii and R. meliloti form infected nodules (14, 27, 50) argues against an essential role for such secreted enzymes during the invasion process. There is of course the possibility that there are other glycanases secreted via a different exporter, and we have some indication that this may be the case since a plyA plyB double mutant does retain some residual CMC degradation that becomes more evident after prolonged growth of colonies on CMC-containing plates.

A key point that we have not yet addressed is the nature of the factor that activates PlyA and PlyB. The EPS or some derivative of it is clearly involved, at least in part. One attractive model is that it is a nascent EPS chain formed prior to modification. The EPS of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 8401/pRL1JI consists of a repeat unit of the β,1-4-linked residues glc, glcA, glcA, and glc with the first glucose residue carrying a β,1-6-linked side chain of three glucose residues terminated with a galactose. Three of the glucose residues are acetylated, and the side chain sugars are substituted with pyruvate and β-OH-butyrate groups (36, 48). In the absence of mutants defective in acetylation, pyruvylation, or OH-butyrylation it is difficult to test whether unsubstituted EPS polymers can activate the glycanase activity. It is important to note that whatever EPS-related component causes activation of PlyB, it enables this glycanase to degrade mature EPS. This conclusion can be drawn because when ethanol-precipitated EPS is included in the agar there is no halo of degradation, but the presence of a lawn of an EPS-producing strain (that lacks glycanases) can induce a halo of degradation of the EPS incorporated into the agar (Fig. 5). It remains to be demonstrated which cellulases, from rhizobia or other bacteria, are activated by their cell surfaces. We already know that the A. caulinodans endoglycanase EglI, which is secreted by the same type I secretion system as PlyA and PlyB, showed high CMC-degrading activity when expressed in an EPS mutant of R. leguminosarum, suggesting it is not specifically activated by an EPS component. Furthermore, it does not degrade R. leguminosarum EPS. Therefore, we believe that endoglycanases may fall into two groups that are or are not activated by a cell surface-related component.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Davies for help with bacterial strains and B. Rolfe and E. Gärtner for kindly sending strain ANU2840. M. Dow made constructive comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the BBSRC. A.Z. was supported by CONICET Argentina.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ardourel M, Demont N, Debelle F, Maillet F, de Billy F, Prome J-C, Denarie J, Truchet G. Rhizobium meliloti lipooligosaccharide nodulation factors: different structural requirements for bacterial entry into target root hair cells and induction of plant symbiotic developmental responses. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1357–1374. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battisti L, Lara J C, Leigh J A. Specific oligosaccharide form of the Rhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharide promotes nodule invasion in alfalfa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5625–5629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beringer J E. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;84:188–198. doi: 10.1099/00221287-84-1-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borthakur D, Barker R F, Latchford J W, Rossen L, Johnston A W B. Analysis of pss genes of Rhizobium leguminosarum required for exopolysaccharide synthesis and nodulation of peas: their primary structure and their interaction with psi and other nodulation genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;213:155–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00333413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callaham D A, Torrey J G. The structural basis for infection of root hairs of Trifolium repens by Rhizobium. Can J Bot. 1981;59:1647–1664. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Batley M, Redmond J W, Rolfe B G. Alteration of the effective nodulation properties of a fast-growing broad host range Rhizobium due to changes in exopolysaccharide synthesis. Plant Physiol. 1985;120:331–349. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng H-P, Walker G C. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5183–5191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5183-5191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dénarié J, Debellé F, Promé J-C. Rhizobium lipo-chitooligosaccharide nodulation factors: signalling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:503–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djordjevic M A, Schofield P R, Rolfe B G. Tn5 mutagenesis of Rhizobium trifolii host-specific nodulation genes result in mutants with altered host-range ability. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:463–471. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djordjevic S P, Chen H, Batley M, Redmond J W, Rolfe B G. Nitrogen fixation ability of exopolysaccharide synthesis mutants of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and Rhizobium trifolii is restored by the addition of homologous exopolysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:53–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.53-60.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downie J A. Functions of rhizobial nodulation genes. In: Spaink H P, Kondorosi A, Hooykaas P J J, editors. The Rhizobiaceae. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1998. pp. 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downie J A, Ma Q-S, Knight C D, Hombrecher G, Johnston A W B. Cloning of the symbiotic region of Rhizobium leguminosarum: the nodulation genes are between the nitrogenase genes and the nifA-like gene. EMBO J. 1983;2:947–952. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Economou A, Davies A E, Johnson A W B, Downie J A. The Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae nodO gene can enable a nodE mutant of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii to nodulate vetch. Microbiology. 1994;140:2341–2347. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finnie C, Hartley N M, Findlay K C, Downie J A. The Rhizobium leguminosarum prsDE genes are required for secretion of several proteins, some of which influence nodulation, symbiotic nitrogen fixation and exopolysaccharide modification. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:135–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4471803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finnie C, Zorreguieta A, Hartley N M, Downie J A. Characterization of Rhizobium leguminosarum exopolysaccharide glycanases that are secreted via a type I exporter and have a novel hepatapeptide repeat motif. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1691–1699. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1691-1699.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gage D J, Bobo T, Long S R. Use of green fluorescent protein to visualize the early events of symbiosis between Rhizobium meliloti and alfalfa (Medicago-sativa) J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7159–7166. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7159-7166.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geelen D, Van Montagu M, Holsters M. Cloning of an Azorhizobium caulinodans endoglucanase gene and analysis of its role in symbiosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3304–3310. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3304-3310.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez J E, Reuhs B L, Walker G C. Low molecular weight EPS II of Rhizobium meliloti allows nodule invasion in Medicago sativa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;9:8636–8641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez J E, Semino C E, Wang L-X, Castellano-Torres L E, Walker G C. Biosynthetic control of molecular weight in the polymerization of the octasaccharide subunits of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13477–13482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerts R, Heidstra R, Hadri A-Z, Downie J A, Franssen H, Van Kammen A, Bisseling T. Sym2 of pea is involved in a nodulation factor-perception mechanism that controls the infection process in the epidermis. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:351–359. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higashi S, Abe M. Scanning electron microscopy of Rhizobium trifolii infection sites on root hairs of white clover. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:1094–1099. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.6.1094-1099.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hooykaas P J J, Van Brussel A A N, den Dulk-Ras H, van Slogteren G M S, Schilperoort R A. Sym plasmid of Rhizobium trifolii expressed in different rhizobial species and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Nature. 1981;291:351–353. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivashina T V, et al. The pss4 gene from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae VF39: cloning, sequence and the possible role in polysaccharide production and nodule formation. Gene. 1994;150:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimenez-Zurdo J I, Mateos P F, Dazzo F B, Martinez-Molina E. Cell-bound cellulase and polygalacturonase production by Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium species. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:917–921. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagan S A, Brewin N J. Mutagenesis of a Rhizobium plasmid carrying hydrogenase determinants. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:1141–1147. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannenberg E L, Rathbun E A, Brewin N J. Molecular dissection of structure and function in the lipopolysaccharide of Rhizobium leguminosarum strain 3841 using monoclonal antibodies and genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2477–2487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krol J E, Skorupska A M. Identification of genes in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii whose genes are homologues to a family to ATP-binding proteins. Microbiology. 1997;143:1389–1394. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb J W, Hombrecher G, Johnston A W B. Plasmid-determined nodulation and nitrogen-fixation abilities in Rhizobium phaseoli. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;186:449–452. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leigh J A, Walker G C. Exopolysaccharides of Rhizobium: synthesis, regulation and symbiotic function. Trends Genet. 1994;10:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ljunggren H, Fåhraeus G. The role of polygalacturonase in root-hair invasion by nodule bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1961;26:521–528. doi: 10.1099/00221287-26-3-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas M M, Peart J L, Brewin N J, Kannenberg E L. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies reacting with the core component of lipopolysaccharide from Rhizobium leguminosarum strain 3841 and mutant derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2727–2733. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2727-2733.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez E, Pardo M A, Palacios R, Cevallos M A. Reiteration of nitrogen-fixation gene-sequences and specificity of Rhizobium in nodulation and nitrogen-fixation in Phaseolus vulgaris. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:1779–1786. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mateos P F, Jimenez-Zurdo J I, Chen J, Squartini A S, Haack S K, Martinez-Molina E, Hubbell D H, Dazzo F B. Cell-associated pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzymes in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1816–1822. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1816-1822.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niehaus K, Becker A. The role of microbial surface polysaccharides in the Rhizobium-legume interaction. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;29:73–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1707-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noel K D, Sáchez A, Fernandez L, Leemans J, Cevallos M A. Rhizobium phaseoli symbiotic mutants with transposon Tn5 insertions. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:148–155. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.148-155.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Neill M A, Darvill A G, Albersheim P. The degree of esterification and points of substitution by O-acetyl and O-(3-hydroxybutanoyl) groups in the acidic extracellular polysaccharides secreted by Rhizobium leguminosarum biovars viciae, trifolii, and phaseoli are not related to host range. J Biol Chem. 1991;25:9549–9555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Priefer U B. Genes involved in lipopolysaccharide production and symbiosis are clustered on the chromosome of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae VF39. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6161–6168. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6161-6168.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rae A E, Perotto S, Knox J P, Kannenberg E L, Brewin N J. Expression of extracellular glycoproteins in the uninfected cells of developing pea nodule tissue. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:563–570. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson J G, Wells B, Brewin N J, Wood E A, Knight C D, Downie J A. The legume-Rhizobium symbiosis: a cell surface interaction. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1985;2:317–331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1985.supplement_2.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruvkun G B, Ausubel F M. A general method for site-directed mutagenesis in prokaryotes. Nature. 1981;289:85–88. doi: 10.1038/289085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherwood M T. Improved synthetic medium for the growth of Rhizobium. J Appl Bacteriol. 1970;33:708–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1970.tb02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutton J M, Lea E J A, Downie J A. The nodulation-signalling protein NodO from Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae forms ion channels in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9990–9994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teather R M, Wood P J. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:777–780. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.4.777-780.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trinick M. Relationships amongst the fast-growing rhizobia of Lablab purpureus, Leucaena leucocephala, Mimosa spp., Acacia farnesiana, and Sesbania grandiflora and their affinities with other rhizobial groups. J Appl Bacteriol. 1980;49:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turgeon B G, Bauer W D. Ultrastructure of infection-thread development during the infection of soybean by Rhizobium japonicum. Planta. 1985;163:328–349. doi: 10.1007/BF00395142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Brussel A A N, Bakhuizen R, van Spronsen P C, Spaink H P, Tak T, Lugtenberg B J J, Kijne J W. Induction of pre-infection thread structures in the leguminous host plant by mitogenic lipo-oligosaccharides of Rhizobium. Science. 1992;257:70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5066.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Larebeke N, Engler G, Holsters M, Van den Elsacker S, Zaenen I, Schilperoort R A, Schell J. Large plasmid in Agrobacterium tumefaciens essential for crown gall inducing ability. Nature. 1984;252:169–170. doi: 10.1038/252169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Workum W A T, Canter-Cremers H C J, Wijfjes A H M, van der Kolk C, Wijffelman C A, Kijne J W. Cloning and characterisation of four genes of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii involved in exopolysaccharide production and nodulation. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:290–301. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vlassak K M, Luyten E, Verreth C, vanRhijn P, Bisseling T, Vanderleyden J. The Rhizobium sp. BR816 nodO gene can function as a determinant for nodulation of Leucaena leucocephala, Phaseolus vulgaris and Trifolium repens by a diversity of Rhizobium spp. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:383–392. [Google Scholar]

- 50.York G M, Walker G C. The Rhizobium meliloti exoK gene and prsD/prsE/exsH genes are components of independent degradative pathways which contribute to production of low molecular weight succinoglycan. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:117–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4481804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.York G M, Walker G C. The succinyl and acetyl modifications of succinoglycan influence susceptibility of succinoglycan to cleavage by the Rhizobium meliloti glycanases ExoK and ExsH. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4184–4191. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4184-4191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.York G M, Walker G C. The Rhizobium meliloti ExoK and ExsH glycanases specifically depolymerize nascent succinoglycan chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4912–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]