Abstract

The advancement in systemic neoadjuvant therapy has significantly increased the pathological complete response (pCR) rate in breast cancer. As surgeries inevitably affect patients physically and psychologically and the accuracy of pCR prediction and diagnosis by minimal invasive biopsy is improving, the necessity of surgery in neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) patients who achieve pCR is under debate. Thus, we conducted a literature review of studies on the selective omission of breast surgery after NAC for breast cancer patients. We summarized the existing predictive models and technologies to predict and diagnose pCR after NAC. Our research indicates that, for nearly half a century, the extent of surgery on both breast and axillary lymph nodes is decreasing, while more precise systematic treatments are increasing. NAC has advanced significantly and its pCR rates have improved, so surgery may be omitted in certain patients. However, accurately predicting pCR after NAC is still a challenge. We also described the design for a randomized clinical trial and the potential problems of omitting surgical treatment after NAC. In summary, the decrease in breast cancer surgery is an unavoidable trend, and more high-quality clinical trials need to be conducted.

Keywords: Breast cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pathological complete response, surgery

Introduction

Breast cancer has surpassed lung cancer as the most diagnosed cancer in women globally [1]. Surgery is the commonly used multidisciplinary management for early breast cancer [2]; however, surgery can substantially affect patients physically and mentally, as up to 20% of the patients after breast-conserving surgery (BCS) experience unfavorable long-term aesthetic outcomes and an impaired quality of life [3,4]. To circumvent this, breast cancer treatment has advanced the surgical options from radical mastectomy and modified radical mastectomy to breast-conserving surgery and plastic/reconstruction surgery during the past half a century. This evolution process demonstrates that the quality of life has become a significant concern in the selection of treatment regimens.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is a well-established treatment option for patients with inoperable locally advanced breast cancer or for those who may benefit from size reduction. It is increasingly being used based in accordance with the clinicopathological features of the tumor [5]. NAC has significantly increased the percentage of patients who achieve pathological complete response (pCR) and dramatically shifted the local treatment regimen of breast cancer and the surgical option for axillary management. According to the consensus from St. Gallen and other expert panels, NAC reduces the extent of surgery and may avoid unnecessary axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) [6-9]. Since NAC has increased the rate of eliminating ALND for patients presenting with clinical node-positive (cN+) disease [10], surgical treatment of the breast is not a requirement. Determining whether surgery is necessary has inspired many investigations. In the study by Tadros et al. [11], the association between breast pCR and nodal pCR in patients with stages I and II triple-negative or HER2-overexpressing breast cancers was examined, and a parallel response between the breast and nodes was found. In the 116 patients with clinically negative nodes at presentation and a breast pCR, 100% had antagonistic nodes after NAC. In those with nodal metastases at diagnosis, 69 of 77 (90%) with a breast pCR had negative nodes compared with only 68 of 160 (43%) who had the residual disease in the breast.

For other types of cancer, such as rectal and esophageal cancer, a ‘watch-and-wait’ strategy has been proposed, and omitting surgery is chosen for cPR patients after NAC without local recurrence [12]. In breast cancer patients who achieved pCR after NAC, it may be reasonable to omit or postpone breast surgery and adopt a ‘watch-and-wait’ approach. At the 16th St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference, M. Morrow [13] suggested the exemption of breast cancer surgery [14]. However, surgery is currently the standard approach for the pathological diagnosis of the response to NAC. More nonsurgical tools such as imaging, minimally invasive needle biopsy, or a combination of diagnostic and predictive tools are urgently needed.

In this review, we first presented an overview of the current strategies of response evaluation and the corresponding surgical treatments after NAC. Then, the clinical trials and obstacles for patients with pCR after NAC to exempt from surgery were comprehensively discussed.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and pCR

NAC was initially applied to convert inoperable locally advanced breast cancer to operable status; however, it was used recently to shrink the tumor and increase the rate of breast-conserving surgery [15]. In the trials of NAC for breast cancer, pCR is the commonly used endpoint. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed that pCR rate can be used as a surrogate for evaluating the efficacy of neoadjuvant treatment because it reasonably predicts clinical benefit [16,17]. A large meta-analysis of 14,640 patients in 29 studies using neoadjuvant systemic therapies for patients with breast cancer has revealed that pCR potentially meets the criteria of a surrogate endpoint for disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) [18].

The definition of pCR is not consistent in history. Two different definitions of pCR are often adopted: ypT0 ypN0 (i.e., absence of invasive cancer and in-situ cancer in the breast and axillary nodes), and ypT0/is ypN0 (i.e., absence of invasive cancer in the breast and axillary nodes, regardless of ductal carcinoma in situ) [19,20]. In the CTNeoBC pooled analysis [21], the progression-free survival (PFS) and OS are similar. However, since the residual ypTis after NAC still has a high risk of local recurrence and needs surgical treatment, the more conservative definition of pCR should be limited to ypT0 [22,23].

The rate of pCR varies dramatically among breast cancer subtypes. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive tumors breast cancers can achieve pCR rates greater than 60% [24-27]. It is commonly acknowledged that pCR is associated with better long-term survival [21,28]. Based on the results of 12 international trials and 11955 patients, Cortazar et al. confirmed the strongest association between pCR and long-term outcomes in TNBC patients (event-free survival, EFS: hazard ratio = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.18-0.33; OS: hazard ratio = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.11-0.25) and in those with HER2-positive and hormone-receptor (HR)-negative tumors who received trastuzumab (EFS: hazard ratio = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.09-0.27; OS: 0.08, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.22) [21]. Similar results were obtained by von Minckwitz et al. [29]. These studies provide the information for selecting patients who are NAC-sensitive or even surgery-omissible after NAC. These increased pCR rates have also led to the studies on omitting surgery for a selected subgroup.

How to predict pCR?

Achieving pCR after NAC has prognostic significance to breast cancer patients, and the adjuvant treatment will be adjusted accordingly. Hence, it is critical to accurately predict pCR after NAC. Currently, the prediction of pCR is based on breast imaging, minimally tumor biopsy, and tumor biology [17,22,30,31]. Radionics features and deep learning models based on mammography, breast ultrasound, breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and PET have also been used for the prediction of the efficacy of NAC in breast cancer, but the model generalization ability remains to be confirmed.

The imaging examinations

Traditional imaging methods, such as breast molybdenum target mammography (MMG) and ultrasound, have limited accuracy in predicting the response to NAC, with the accuracy of 30% and 60%, respectively [32,33]. Breast MRI has a higher sensitivity to determine pCR, but its specificity is low, ranging from 60% to 83% [34,35], which makes MRI unreliable in determining whether a patient can be exempted from surgery [36-38]. Therefore, efforts have been made to identify reliable early markers for therapy response to individualized NAC. One of these studies was the trial conducted by the West German Study Group (WSG): the Adjuvant Dynamic Marker Adjusted Personalized Therapy Trial Optimizing Risk Assessment and Therapy Response Prediction in Early Breast Cancer (ADAPT), which was a prospective, controlled, randomized umbrella clinical trial. The primary objective of this analysis was to compare the value of MRI versus ultrasound performed at the end of NAC for the prediction of pCR and residual disease (RD). A total of 845 patients at 58 sites in Germany were enrolled. Overall, the negative predictive values (NPV, proportion of correctly predicted tumor size ≤ 10 mm) of MRI and ultrasound were 0.92 and 0.83, respectively, while the positive predictive values (PPV, correctly predicted tumor size >10 mm) were 0.52 and 0.61, respectively. MRI demonstrated a higher NPV and a lower PPV than ultrasound in HR+/HER2+ and HR-/HER2+ tumors. Both methods had a comparable NPV and PPV in HR-/HER2- tumors. Even trimodality imaging, including MMG, ultrasound, and MRI, could not provide adequate information for choosing patients with high correlation between complete clinical response (cCR, defined as no residual palpable disease in the breast, which was evaluated radiologically before surgery) and pCR, which was evaluated pathologically post-surgery [39]. The potential of machine learning with multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) for predicting pCR after NAC is still under exploration [40].

The invasive biopsy

Although the imaging examinations are not accurate [41-43], the minimally invasive biopsy (MIB) technique guided by breast imaging has the potential to accurately predict the complete remission of breast pathology after NAC, which makes the non-operative treatment of breast cancer a feasible choice. Heil et al. [44] first reported the application of MIB techniques in pCR prediction in patients with cCR to NAC, in which the needle biopsy by core-cut or vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) was used in patients with a cCR diagnosis after NAC. The pCR rate was the highest (74.2%) in patients with HER2+ tumors, followed by 67.3% in patients with TNBC. The NPV of the MIB diagnosis of pCR was 71.3%, and the false-negative rate (FNR) was 49.3%. None of the mammographically guided VABs showed a false-negative result (NPV 100%; FNR 0%), whereas the core cuts had 70.2% NPV and 60.9% FNR. The NPV of ultrasound guided VAB was 53.3%. In 2016, Heil et al. [45] further explored the ability of a MIB to predict pCR in breast cancer. This study enrolled 50 breast cancer patients diagnosed as cCR after NAC and received ultrasound guided VAB. In the entire cohort (n = 50), VAB yielded an NPV of 76.7% and an FNR of 25.9%. In a histopathologically representative VAB sample (n = 38), the NPV was 94.4%, and the FNR was 4.8%. This study concluded that VAB could accurately diagnose pCR when pathological evaluation showed a representative sample. Moreover, Heil et al. [23] designed a multicenter, confirmative, one-armed, intra-individually-controlled, open, diagnostic trial that enrolled 600 patients from 21 centers in Germany (NCT02948764). The purpose of this trial was to prove that the FNR of VAB was below 10% in pCR diagnosis. The results, which was published in 2020 [46], showed that in 398 patients with early stage 1-3 breast cancer, the FNR of image guided VAB alone was 17.8%. However, 51% of the patients with FNR had inconclusive features, such as multicentric lesions or recurrence, which did not meet the study’s enrollment criteria. Further analyses found that if no residual lesions were found in the imaging and VAB, the FNR could be reduced to 6.2%, or the FNR could be reduced to 0% by performing VAB with a thicker 7-gauge needle. This study proved the feasibility of VAB in evaluating pCR by optimizing the population selection and the adequate technology implementation.

In another study conducted by Kuerer et al. [47], Forty patients with T1-3N0-3 triple-negative or HER2-positive breast cancer underwent ultrasound-guided or MMG-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and VAB in the primary breast tumor region. VAB alone was more accurate than FNA alone (P = 0.011); however, combined FNA and VAB demonstrated an improved accuracy of 98% (95% CI, 87%-100%; FNR 5%; NPV 95%) in predicting residual breast cancer. Subgroup analyses showed that FNR could be further reduced to 3.2% when the admission criteria were more stringent. These studies demonstrated that biopsy accuracy could be improved by using thicker needle, applying multifocal MMG or MRI evaluation, increasing sample size, or expanding the sampling scope.

The MICRA trial (Minimally Invasive Complete Response Assessment of the breast after NST) [48,49] was a multicenter, prospective, single-arm study in three Dutch hospitals to determine the accuracy of ultrasound-guided biopsies in identifying breast pCR (ypT0) after NAC in 202 patients with radiologic partial or complete response (rCR) on MRI. The FNR of pCR assessed by biopsy- was 37% (29 out of 78; 95% CI 27-49). The sensitivity of the biopsies was 63% (49 of 78, 95% CI 51-74), and the specificity was 100% (89 of 89, 95% CI 0.96-1). The positive predictive value was 100% (49 of 49, 95% CI 0.93-1), while the negative predictive value was 75% (89 of 118, 95% CI 67-83). The MICRA trial showed that ultrasound-guided biopsies of the breast failed to detect residual disease in approximately one-third of patients with a pCR to NAC on MRI.

Anothetr important trial performed a multi-institutional pooled analysis [50] on data collected from 166 women who underwent post-NAC image-guided biopsy in Royal Marsden Hospital, Seoul National University Hospital, and MD Anderson Cancer Center. The overall pCR rate was 51.2% (16.1% for HR+/HER2-, 44.7% for HR+/HER2+, 69% for HR-/HER2+, and 66.1% for TN]. The FNR was 3.2% (95% CI 0-8.8), while the NPV was 97.4% (95% CI 84.6-99.6), with an overall accuracy of 89.5% (95% CI: 80.3-95.3). This large multicenter study suggests that a standardized protocol using image-guided VAB of a tumor bed measuring up to 2 cm with at least 6 samples could reliablly predicr the residual disease and pCR. Additionally, NOSTRA PRELIM [51] is an ongoing prospective study to explore the accuracy of minimally invasive biopsy in assessing pCR after NAC.

Nevertheless, the studies discussed above were focused on the accuracy of ultrasound guided biopsy and did not investigate the utilization of MRI or MRI-guided biopsy. MRI has demonstrated the highest sensitivity in detecting residual tumors and, hence, may show a superior performance. Sutton et al. [52] reported the results of using MRI-guided biopsy for pCR assessment, in which the negative predictive value was 92.8% (95% CI, 66.2%-99.8%), with an accuracy of 95% (95% CI, 75.1%-99.9%), and sensitivity of 85.8% (95% CI, 42.0%-99.6%), while the positive predictive value was 100%, with a specificity of 100%. This study suggested that the MRI-guided biopsy might be a viable alternative to surgical resection for the appropriately selected patients after NAC. Lee et al. [53] evaluated the accuracy of ultrasound-guided biopsy aided by MRI in predicting pCR in the breast after NAC. They found that a preoperative biopsy had an NPV, accuracy, and FNR of 87.1%, 90.0%, and 30.8%, respectively. Additionally, using at least 5 biopsy cores based on tumor size ≤ 0.5 cm and a lesion-to-background signal enhancement ratio (L-to-B SER) of ≤ 1.6 on MRI resulted in 100% NPV and accuracy. The studies on predicting pCR by VAB after NAC were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies on predicting pCR by VAB after NAC

| Study | Type | Inclusion | n | Means of prediction | FNR and NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heil 2015 [44] | prospective | cCR after NAC | 164 | 116 CCs; | mammographically guided VABs: NPV 100%, FNR 0%; |

| 46 VABs | ultrasound-guided VABs: NPV 53.3% | ||||

| CCs: NPV 70.2%; FNR 60.9% | |||||

| The existence of a clip marker tended to improve the NPV (odds ratio 1.98) | |||||

| Heil 2016 [45] | prospective | clinical/imaging partial or complete response, lesion visible in ultrasound | 50 | Ultrasound-guided VAB | NPV: 76.7% FNR: 25.9% |

| Given a histopathologically representative VAB sample (n =38), the NPV was 94.4%, and the FNR was 4.8% | |||||

| Heil 2020 [46] | prospective | T1-3 | 398 | Image-guided VAB | FNR 17.8% |

| If no residual lesions were found in imaging and VAB, the FNR could be reduced to 6.2%, or the FNR could be reduced to 0% by performing VAB with the giant needle by volume (7-gauge) | |||||

| Kuerer et al. [47] | prospective | T1-3, N0-3 TNBC or HER2-positive | 40 | ultrasound-guided or mammography-guided FNA and VAB | VAB alone was more accurate than FNA alone |

| Combined FNA/VAB demonstrated an accuracy of 98%, FNR was 5%, and NPV was 95% | |||||

| If the admission criteria are stringent, FNR could be further reduced to 3.2% | |||||

| MICRA study [48] | prospective | N0, radiologic partial or complete response on MRI | 525 | Ultrasound-guided 14 G biopsies targeted around pre-NAC-placed marker (four central; four peripheral) | The FNR was 37%. Sensitivity was 63%, specificity was 100%, PPV was 100%, and NPV was 75% |

| NOSTRA PRELIM study [51] | prospective | ER-negative or HER2-positive; lesion size >1 cm; cN+ | 150 | Ultrasound-directed biopsy | FNR < 10% |

| Sutton [52] | prospective | IA to IIIC; cCR on MRI | 20 | MRI-guided biopsy | NPV was 92.8%, accuracy was 95%, sensitivity was 85.8%, PPV was 100%, and specificity was 100% |

| Tasoulis MK [50] | pooled analysis | - | 166 | Image-guided biopsy | The FNR was 3.2%, NPV was 97.4%, overall accuracy was 89.5% |

| Lee [53] | prospective | cCR on MRI | 20 | Ultrasound-guided biopsy | NPV, accuracy, and FNR was 87.1%, 90.0%, and 30.8% |

Abbreviations: NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, complete pathological response; cCR, clinical complete response; CCs, Core-cut-MIB; VAB, Vacuum-assisted-MIB; TAD: targeted axillary dissection; FNR, false-negative rate, PPV, positive predictive values; NPV, negative predictive values; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The biological features of tumor

Multiple prediction models for evaluating the effectiveness of NAC were constructed based on the biological features, such as lymphovascular invasion, cell-free plasma DNA (cfDNA), cell-free circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), the expression level of estrogen receptor (ER) and Ki67, and NAC regimen [22,54,55]. Some studies [56,57] have proven that nomograms based on clinical and biological factors can predict the early response of NAC for breast cancer with high accuracy, while others studies [58,59] have revealed that ctDNA positivity before NAC is associated with a decreased possibility of pCR, and that increased ctDNA level after NAC is correlated with poor response.

The local treatment of breast after NAC

Breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy are the most common surgeries for breast cancers; however, invasive procedure-associated impact on breast image and aesthetics will affect patients physically and psychologically [60]. NAC can shrink the tumors in locally advanced breast cancer patients, thereby increasing the rate of breast-conserving surgery. However, since the shrink pattern of tumor after NAC tends to be a concentric or patch like contraction [61], it is challenging to ensure negative surgical margins in patients with multifocal residual tumors, which is one of the factors causing local recurrence [62-66].

Early attempts to forgo surgery and administer radiotherapy after a cCR date back to the late 1970s. Due to the unacceptable high locoregional recurrence rate (LRR) and the lack of precise imaging methods to predict pCR, this treatment approach was not actively pursued. As both cCR and pCR rates increase, the development of highly accurate imaging methods and biopsy techniques has revived the idea of omitting local surgical therapy.

Significant clinical trials

Ring et al. [67] conducted the most extensive retrospective analysis to date by enrolling 453 patients who received NAC between 1986 and 1999, and among them, 136 had reached cCR by ultrasound. Of the 136 cCR patients, 67 underwent surgery as their primary locoregional treatment modality, and 69 only had radiotherapy. After the median follow-up of 63 months in the surgery group and 87 months in the radiotherapy treatment (RT) group, there was no significant difference in DFS between these two groups (5-year, 74% vs 76%; 10-year, 60% vs 70%, P = 0.90), as well as the OS at 5 years (74% vs 76%). No significant difference was seen in LRR rates, but there was an upward trend in the LRR for the RT group (21% vs 10% at 5 years; P = 0.09).

Mauriac et al. [68] reported a randomized trial including 272 women with operable breast cancer. A total of 124 patients were initially treated by chemotherapy. After that, 44 patients with a cCR were treated with radiotherapy only (RT group), while 40 patients with residual tumors (< 20 mm) were treated with lumpectomy and axillary node dissection, and radiotherapy (BCS+RT group). Forty-nine patients with residual tumors (>20 mm) had mastectomies. After the median follow-up of 124 months, the LRR rate was slightly higher in the RT group than in both BCS+RT and mastectomy groups (34% for the RT group, 22.5% for the BCS+RT group, and 22.4% for the mastectomy group).

In the study by Touboul et al. [69], 97 patients with locally advanced non-metastatic and non-inflammatory breast cancer were treated between 1982 and 1990. Among them, thirty-seven patients (38%) were noted with residual tumor of >3 cm in diameter located behind the nipple or multicentricity during physical examination and underwent a mastectomy and axillary dissection. Thirty patients (31%) achieved cCR and had additional radiation boost without surgery. Twenty-seven patients (28%) who had a residual mass of ≤3 cm in diameter was treated with wide excision and axillary dissection followed by a radiation boost to the excision site. The 5-year LRR rate was 16% for radiotherapy only group, 16% for patients with wide excision and radiotherapy, and 5.4% for patients receiving mastectomy (P = 0.04). The local surgical treatment did not significantly influence the five-year and ten-year OS rates.

In the study by Scholl et al. [69], the response to radiotherapy was evaluated by clinical examination and MMG. Forty-five patients who achieved cCR underwent radiotherapy only, and 23 patients with partial response underwent surgery. The 5-year local recurrence-free survival was significantly different between the two groups (70% vs 84%, P < 0.05).

A recent large retrospective study by Daveau et al. [70] enrolled 165 patients who achieved cCR according to MMG and ultrasound after NAC. In this cohort, 65 (39%) patients were treated with breast surgery followed by radiotherapy, and 100 (61%) patients were treated with radiotherapy alone. There were no significant differences in OS and DFS rates between these two groups. Nevertheless, a trend toward lower locoregional control rates was observed in the non-surgery treatment group compared with the surgery group (77% vs 90% at 5 years and 69% vs 83% at 10 years; P = 0.06). This retrospective cohort study demonstrated that active surveillance or de-escalation therapy might be an option for patients who achieved cCR without impairing OS, DFS, or LRR.

Previous clinical trials

In the study by Clouth et al. [71], multiple core needle biopsies were applied to evaluate pCR after NAC. From 2000 to 2005, 101 patients with operable local-advanced breast cancer were treated with NAC. Notably, this study introduced radiological complete response (rCR), a new evaluation indicator defined as no evident tumor or malignant micro-calcifications on any imaging modality. Moreover, cCR was defined as no residual palpable disease in the breast. Twenty-six patients evaluated as both cCR and rCR were recommended for multiple core biopsies (six to ten per quadrant). Among them, 16 patients assessed as pCR by multiple core needle biopsy received radiotherapy only. Others underwent mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery. The mean follow-up was 33.5 months. There was no difference in DFS or OS between the surgery and non-surgery groups; however, there was a trend towards better survival in the patients of the non-surgery group compared to the surgery group. The overall LRR was 9.5% for the surgery group and 12.5% for the non-surgery group.

In the study by Ozkurt et al. [72], the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) was searched to identify 93,417 women aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and received NAC between 2010 and 2015. This study included 350 women with cT1-4, N0-3, and M0 tumors who underwent NAC and did not receive surgery (surgery-omission group). A matched surgical cohort with 3938 patients was extracted from the NCDB. The median follow-up time was 30 months. The 5-year OS was 74.8% for all patients in the surgery-omission group and 79% for the surgery group, and the 5-year OS rates for the patients with cCR in the surgery-omission and surgery group were 96.8% and 92.5%, respectively (P = 0.15).

On July 8, 2017, Marta et al. conducted a non-randomized trial of NAC followed by radiotherapy alone in breast cancer patients who achieved MRI-assessed cCR after complete NAC. In this study, radiotherapy was referred to as 3-dimensional (3D) conformal or intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). The definition of cCR was the absence of visible enhanced tumor on any serial images. Patients were 40-75 years old with unicentric invasive breast cancer. The study is still on going, and no results have been updated when this review is under preparation.

Kuerer et al. from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center also conducted a pilot study to identify breast cancer patients for the potential omission of surgery (NCT 02455791) [47,73]. The ultrasound-guided biopsy of the tumor site was applied to assess the response to NAC. The patients enrolled in this study had TNBC or HER2+ breast cancer. In 2018, they reported the first result on the accuracy of FNA and vacuum-assisted core biopsy (VACB) in assessing the presence of residual cancer in the breast after NAC. Their result was the foundation for further study and ensured that surgery-omitting patients could be identified safely and accurately. In 2021, Pfob et al. [73] developed and tested four multivariate algorithms using the clinical information, tumor, and VAB variables to identify patients with pCR. In the training set, FNR was 1.2%, while in the external validation set, the FNR was 0%, suggesting that this algorithm might accurately stratify breast cancer patients without residual disease after NAC for omitting surgery modality. This finding may pave the way for the future study of surgery omission in these patients. Table 2 summarized the studies that adopted radiotherapy instead of breast surgery after NAC.

Table 2.

Studies on radiotherapy alone instead of breast surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Study | Period | Type | n | Treatment | Follow-up | OS or DFS | LRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daveau [70] | 1985-1989 | retrospective | 165 cCR | 65 Surgery | 12 years | RT vs Surgery | RT vs Surgery |

| 100 RT | 5-year 91% vs 82% | 31% vs 17% | |||||

| 10-year 77% vs 79% | |||||||

| L.Mauriac [68] | 1985-1989 | retrospective | 272 | A: 138 initial surgery | 124 months | NS in DFS and RFS | 22.5% BCS+RT, |

| 44 cCR | B: 134 NAC: | 22.4% Mastectomy | |||||

| 40 BCS+RT, | 34% RT | ||||||

| 49 mastectomy | |||||||

| 44 RT | |||||||

| Ring [67] | 1986-1999 | retrospective | 453, | 69 RT | RT vs Surgery | RT vs Surgery | RT vs Surgery |

| 136 cCR | 47 Surgery | 87 months vs 67 months | DFS and OS. | 21% vs 10% | |||

| 5-year 76% vs 74% | |||||||

| 10-year 70% vs 60% | |||||||

| Perloff [92] | 1978-1983 | retrospective | 87 | 43 Surgery | 39 months | RT vs Surgery | RT vs Surgery |

| 44 RT | 63% vs 50% | 27% vs 19% | |||||

| Scholl [69] | 1986-1990 | retrospective | 200 | 36 mastectomy ± RT, | 66 months | - | - |

| 62 BCS+RT | |||||||

| 102 RT | |||||||

| Clouth [71] | 2000-2005 | retrospective | 101, | 16 RT | 33.5 months | NS in DFS or OS. | 9.5% surgery; |

| 16 pCR | 84 surgery | 12.5% non-surgery. |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; LRR, locoregional recurrence rate; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, pathological complete response; cCR, clinical complete response; RT, radiotherapy treatment; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; NS, no significant.

The omission of axillary lymph node dissection after NAC

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) instead of ALND has become the standard of care for patients with clinically lymph node-negative (cN0) breast cancer. Nevertheless, for those with cN+ breast cancer, ALND is still the standard local treatment for axillary regions. However, DiSipio et al. reported about 20% of ALND patients experience upper limb lymphedema, which causes arm pain, heaviness, swelling, and psychosocial morbidity during the two-year follow-up [74]. Other complications of ALND include shoulder joint dysfunction and numbness.

Before the general use of NAC, attempts have been made to avoid ALND with axillary radiotherapy in node-negative or node-positive patients [75,76]. The results demonstrated there was no significant difference in survival outcomes between these two treatment options, but there was a significantly different rate in developing upper limb lymphedema between patients in ALND and axillary radiotherapy groups. Thus, even without NAC, radiotherapy can also act as an alternative treatment of ALND, which can reduce the complications caused by axillary surgery. It is conceivable that NAC will have the similar beneficial effect.

Since NAC can eliminate occult axillary lymph node metastasis, studies on axillary omission management in patients with cN0 after NAC have been conducted. The SLNB after NACT in cN0 is widely adopted and regarded as the standard of care. In the SENTinel NeoAdjuvant (SENTINA) study [77], the detection rate of SLNB was reduced from 99.1% before NAC to 80.1% after NAC, and the FNR of SLNB after NAC was 14.2%. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z1071 clinical trial (Alliance) explored the FNR of SLNB in patients with initial biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer who received NAC [78-80] and found that the FNR was 12.6% for the patients in cN1 group and 0% for the patients in the cN2 group [79]. Furthermore, sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping with blue dye (isosulfan blue or methylene blue) and radiolabeled colloid mapping agents was recommended to maximize the detection rate of SLN identification and minimize FNR. However, NAC may affect the pathway of lymphatic reflux. Lymph node fibrosis and tumor cell obstruction of the lymphatic channel may affect the movement of tracers such as a dye or radioactive colloid, resulting in a decrease in the detection rate of SLNB and an increase in the false-negative rate. So, how to reduce the FNR of SLNB is an urgent issue that needs to be resolved.

Emerging evidence has indicated that surgery may not be the only choice for breast cancer patients with 1 or 2 axillary lymph node macro-metastases. Axillary radiotherapy instead of axillary lymph node dissection is feasible and can improve the quality of life without affecting DFS and OS [80]. Alliance A011202 and NSABP B-51/RTOG1304 (NRG9353) are two ongoing randomized controlled trials. Alliance A011202, registered in 2013, has planned to enroll 1660 patients to compare the long-term safety between ALDN plus radiotherapy and radiotherapy alone in SLN-positive patients (NCT 01901094). NSABPB-51/RTOG1304 (NRG9353), started in 2003 (NCT 01872975), aimed to study the safety and efficacy of local axillary radiotherapy.

The goal of the ongoing European Breast Cancer Research Association of Surgical Trialists (EUBREAST)-01 (NCT 04101851) trial [81] is to prove the oncological safety of the omission of axillary SLNB after pCR in the breast in response to NAC for TNBC and HER2+ disease in initially cN0 patients. In this prospective non-randomized, single-arm surgical trial, all patients with rCR at the end of NAC will be treated with BCS alone without axillary surgery. The main inclusion criteria are clinically and sonographically (iN0) negative axillary status before NAC and planned BCS with postoperative radiotherapy. For the cases with cN0 and iN+, a negative core biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the sonographically suspected lymph node is required. Studies on the omission of ALND were summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies on the omission of axillary lymph node dissection

| Study | Period | Type | Inclusion | n | Treatment of axillary | Follow-up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSABP B-04 [75] | 1971-1974 | prospective | primary operable breast cancer | 1765 | 1079 cN0 (1/3 ALND; 1/3 RT; 1/3 no surgery) | 25 years | NS in RFS, DFS, or OS |

| 586 cN+ (1/2 RT; 1/2 ALND) | |||||||

| AMAROS [93] | 2001-2010 | prospective | T1-2, cN0 | 4806 | 2402 ALND | 6.1 years | ALND vs RT: |

| 2404 RT | 5-year axillary recurrence | ||||||

| 1425 cN+ | 0.43% vs 1.19% | ||||||

| 744 ALND; 681 RT | DFS: 86.9% vs 82.7% | ||||||

| OS: 81.4% and 84.6% | |||||||

| ACOSOG Z0011 [94] | 1999-2004 | prospective | T1-2, cN0; | 891 | 446 SLND alone | 9.3 years | SLND vs ALND |

| N1-2 | 445 ALND | OS: 86.3% vs 83.6% | |||||

| DFS: 80.2% vs 78.2% | |||||||

| NS in LRR | |||||||

| Alliance A011202 | 2013- | prospective | T1-3, N1, M0 | 1660 | ALND vs RT. | - | No results |

| NRG9353 | 2003- | prospective | T1-3, N1, M0 | 1636 | ALND vs RT | - | No results |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; LRR, locoregional recurrence rate; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, pathological complete response; cCR, clinical complete response; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; SLND, sentinel lymph node biopsy; TAD, targeted axillary dissection; RT, radiotherapy treatment; NS, no significant.

Prediction of the axillary lymph node status after NAC

The traditional clinical evaluation of axillary lymph node status mainly relies on physical examination and breast imaging. When suspicious lymph nodes are found, fine needle aspiration or hollow needle biopsy will be used to obtain cytological or histological samples. Nevertheless, these traditional evaluations have an FNR of 5%-10% [82].

The results of the SENTINA study [77] showed that the detection rate of using combined tracer in SLNB was higher than using radionuclides alone (87.8% vs 77.4%). SENTINA study also showed that the FNR decreased when increasing the number of detected SLN. The results from the ACOSOGZ1071 study [79] also confirmed that with double tracer, the FNR decreased from 20.3% to 10.8%, and when more than 3 SLN were detected, the FNR further decreased to 9.1%. In addition, similar results were observed in the GANEA2 study [83]. Importantly, Caudle et al. from MD Anderson Cancer Center developed a novel surgical technique, targeted axillary dissection (TAD), which involved removing SLNs as well as the clipped lymph node by localization with iodine-125 (125I) radioactive seeds [84]. A total of 208 patients were enrolled in this study and had clips placed in nodes with biopsy-confirmed metastasis before initiating NAC. After NAC, 118 patients underwent SLND and ALND, and the FNR was 10.1%. Adding evaluation of the clipped node to the evaluation of the SLN(s) reduced the FNR from 10.1% for SLND alone to 1.4% (95% CI, 0.03 to 7.3) (P = 0.03). These results suggested that we could improve the accuracy of axillary staging in clinically node-positive patients who received neoadjuvant therapy by marking nodes with biopsy-confirmed metastatic disease.

Swarnkar et al. [85] systematically reviewed the FNR of marked lymph node biopsy (MLNB) alone and TAD (MLNB plus SLNB) in patients with biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer who received NAC. There were 9 studies of MLNB alone with 366 patients, which yielded a pooled FNR of 6.28% (95% CI: 3.98-9.43), while TAD had 13 studies including 521 patients, with an FNR of 5.18% (95% CI: 3.41-7.54). No significant difference in FNR was observed between MLNB alone and TAD (P = 0.48). This pooled analysis has confirmed that MLNB is an accurate technique in axillary staging after systemic therapy, and SLNB can be safely omitted from TAD.

In addition, Donker et al. [86] suggested marking the axillary lymph node with radioactive iodine (125I) seeds (MARI) procedure to assist the assessment of the pathological response of nodal metastases after NAC in breast cancer patients. It is technically possible to mark tumor-positive axillary lymph nodes with an iodine seed before initiating NAC. Indeed, the selective excision of the marked lymph nodes after NAC had a high identification rate of 97% and a low FNR of 7% [86]. Furthermore, Koolen et al. [87] combined pre-NAC positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) and post-NAC MARI procedures to potentially avoid ALND in 74% of patients.

Taken together, we can reduce FNR by combining double tracer (blue dye and radionuclide), removing more than 3 SLNs, and applying the TAD technique. These clinical studies provide a new direction for axillary management after NAC. Furthermore, they also provide a rationale for whether regional radiotherapy can minimize the extent of surgery or even safely avoid surgery. Studies on predicting the axillary lymph node status after NAC were shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Studies on predicting the status of axillary lymph nodes after NAC

| Study | Period | Type | Inclusion | n | Means of prediction | FNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAD [84] | 2011-2015 | prospective | cN+ post-NAC | 208 | 115 clipped node; | SLN alone: 10.1% |

| 118 SLND | SLN + clipped node: 1.4% | |||||

| SENTINA [77] | 2009-2012 | prospective | - | 1737 | arm A: cN0 SLND before | 1 SLN: 24.3%; |

| NAC | 2 SLNs: 18.5%; | |||||

| arm B: pN1 second SLND | more than 2 SLNDs: ≤10%. | |||||

| arm C: cN1 to ycN0 ALND+SLND | blue dye + radionuclide: 8.6% | |||||

| arm D: ycN1 ALND no SLND | radionuclide alone: 16.0% | |||||

| ACOSOG Z1071 [79] | 2009-2011 | prospective | T0-4, N1-2, M0 | 756 | 16.8% radiolabelled colloid; | 2 or more SLNs: ≤10% |

| 4.1% blue dye; | blue dye + radionuclide: 10.8% | |||||

| 79.1% combined | radionuclide or dye alone: 20.3% | |||||

| 12.0% 1 SLN; | ||||||

| 88.0% 2 or more SLNs | ||||||

| GANEA2 [83] | 2010-2014 | prospective | T1-3, N0-2, M0 | 957 | 419 cN0 SLND; | 1 SLN: 19.3% |

| 307 pN1 | 2 or more SLNs: 7.8% | |||||

| Donker [86] | 2008-2012 | retrospective | - | 100 | MARI node identified and ALND performed (n = 95) | FNR: 7%; NPV: 83% |

| sensitivity: 90% | ||||||

| specificity: 100% | ||||||

| Koolen [87] | 2008-2012 | prospective | T2-3, cN+ | 93 | - | Combining PET-CT before NAC and the MARI procedure after NAC has the potential for ALND to be avoided in 74% of patients |

| Swarnkar [85] | - | pooled analysis | - | MLNB, 366; TAD, 521 | MLNB and TAD | FNR was 6.28% for MLNB; FNR of 5.18% for TAD |

Abbreviations: NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, pathological complete response; ALND: axillary lymph node dissection, SLND: sentinel lymph node biopsy, RT: radiotherapy treatment, MARI: marking the axillary lymph node with radioactive iodine (125I) seeds, PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography, FNR: false-negative rate, NPV: negative predictive values, SLN: sentinel lymph node; MLNB: marked lymph node biopsy.

Controversial opinions

The consensus from the experts in the 17th St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Congress (SG-BCC2021) may be significant. However, no experts have elected for omitting surgeries in the case of cPR or rCR. Furthermore, only 14% of the experts have elected for omitting surgeries when pCR was proven by core biopsy.

Regarding whether RT could replace ALND for patients with cN0 and SLN with residual diseases after NAC, the opinions vary greatly. About 70% of experts agree on it when one of the 3 SLD has micro-metastases (0.2-2 mm); 88% of experts agree on the condition that one of the 3 SLD has isolated tumor cells (ITCs); 52% of experts agree on it when one of the 3 SLD has macro-metastases (>2 mm), while only 38% of experts believe RT could replace ALND when two of 3 SLN are positive, and at least one has macro-metastasis.

Regarding TAD, 60% of experts view it as an appropriate option for standard ALND, and 90% of experts propose that TAD could only be used on cN1 patients with marked, initially involved nodes and converted to cN0 before surgery.

For patients with cytologically/histologically proven cN1 at presentation and with an excellent clinical response to NAC and will receive RT, 41% of experts agree that ALND may be avoided if a clipped node is presented and all three SLN should be negative, and 37% of experts believe that single SLN should be negative.

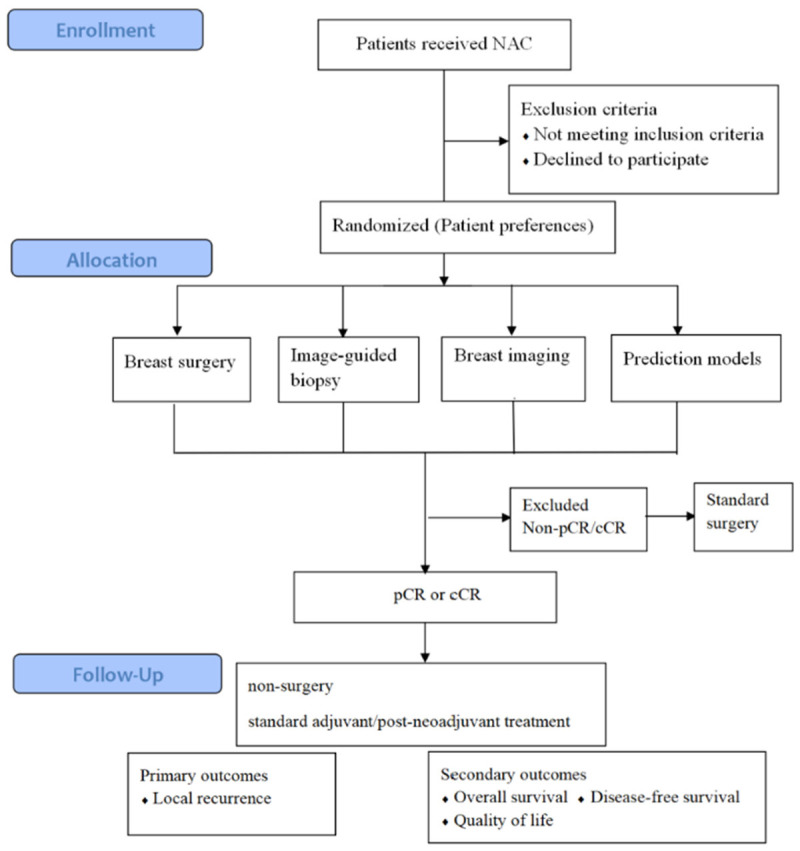

Future clinical trial design

How should we design and perform clinical trials to convincingly evaluate the feasibility of omitting surgery after NAC? The critical step is to gather sufficient evidence to predict pCR after NAC. We should design and support controlled clinical trials to address the significant question that whether we can predict pCR after NAC in non-invasive methods. A trial should compare predicting strategies discussed above: (i) breast surgery; (ii) vacuum-assisted, minimal invasive biopsy (VAB); (iii) breast imaging, such as MRI, ultrasound, and mammography according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 [88,89]; (iv) prediction models based on multiple clinical and biological features. The randomized controlled clinical trial is the gold standard level of proof. However, patient preferences cannot be overlooked, as patients may refuse non-surgery treatment. In addition, the eligibility criteria vary among different diagnostic tools and may be difficult to standardize. Therefore, patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and TNBC are the recommended target populations for primary prospective clinical trials. The primary endpoint should be locoregional or regional breast cancer recurrence. Secondary endpoints should include OS, DFS, and quality of life. The sample size should be calculated based on literature research using PASS software V.11.0. The parameter selection should be based on the results from the previous studies [23,37,58,90,91]. For exaple, if we assume that the NPV for invasive biopsy, imaging tools, and prediction models is 80%, 70%, and 75%, respectively, with the test power (1-β) of 0.90 and significance level (α) of 0.05, 198 participants are required. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, we estimate final sample size should be 250 patients.

Conclusions and perspectives

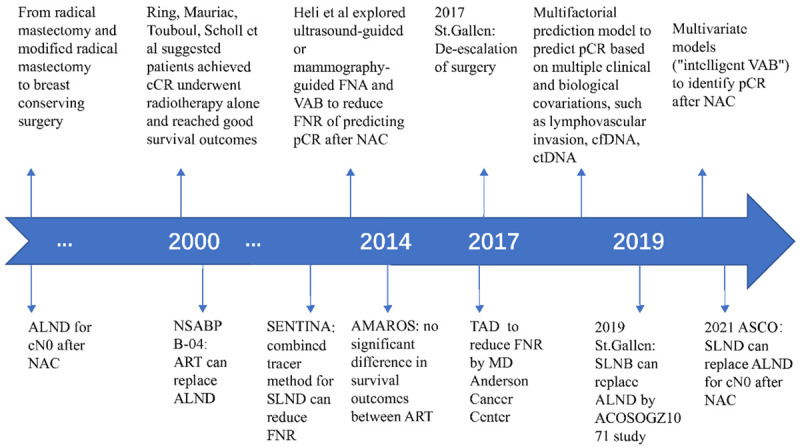

With the progress in adjuvant therapy and the prolonged patients’ survival time, the quality of life of patients has become one of the major concerns for doctors. Indeed, for nearly half a century, the extent of surgery on both breast and axillary lymph nodes has decreased, while more precise systematic treatments have increased. These trends reflect the realization that surgery is traumatic and may also be unnecessary in specific subgroups of patients. Thus, new therapeutic modalities should be promoted for patients with excellent response to NAC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The timeline of surgery strategies for breast and axillary after NAC. NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, pathological complete response; cCR, clinical complete response; VAB, vacuum-assisted biopsy; cfDNA, cell-free DNA; ctDNA, cell-free circulating tumor DNA; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; SLND, sentinel lymph node biopsy; TAD, targeted axillary dissection; ART, axillary radiotherapy.

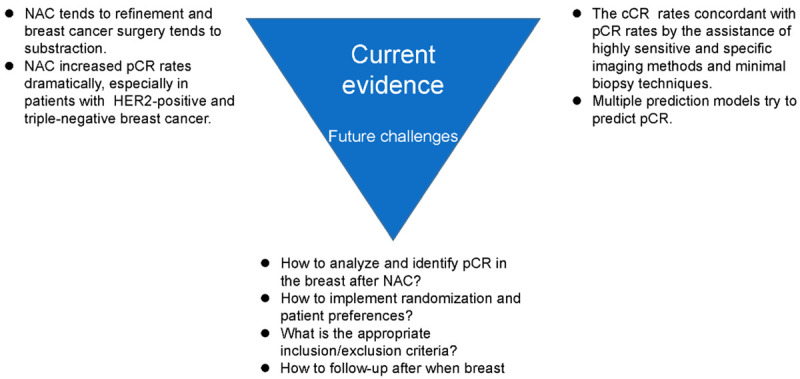

Over the recent decades, NAC has been improved considerably, and its pCR rates are improving, especially in TNBC and HER2-positive subgroups. Surgery may be avoided in these patients and replaced by radiotherapy; however, the main obstacle lies in the accuracy of pCR prediction of NAC. Current imaging methods lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity to select pCR patients. Ongoing trials using image-guided minimal biopsy were designed to test the safety of potential surgery omission in exceptional responders after NAC. There are also challenges in designing and performing randomized controlled trials. Patient preference may hinder enrollment as patients in the non-surgery group may psychologically feel unsettled and abandoned and ask for surgery. In addition, the appropriate patient enrollment criteria should also be investigated. Furthermore, how to follow up the patients who have omitted surgery is a clinical issue, as they may need follow-up imaging at shorter intervals than annually. Moreover, the actual treatment may not necessarily follow the standard protocols after local recurrence. All these issues need to be clarified in future clinical trials (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Current evidence and future challenges of omitting surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, pathological complete response; cCR, clinical complete response.

In summary, the forgoing of breast cancer surgery may be an unavoidable trend, therefore, more high-quality clinical trials should be conducted. Presently, most studies on the early assessment of breast cancer response to NAC are retrospective single center study with a relatively smaller sample size. In the future, multicenter, larger sample size, prospective studies are essential. Artificial intelligence methods can also be used to further establish a stable and efficient prediction model for predicting the efficacy of NAC on breast cancer. A randomized clinical trial design was illustrated by the diagram in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of a clinical trial design to evaluate the feasibility of omitting. Surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; pCR, pathological complete response; cCR, clinical complete response.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the authors of the previous studies involved in this review. This study was funded in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802669 to JL), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2020-I2M-C&T-B-068 to JL), the Beijing Hope Run Special Fund (LC2020B05 to JL), and the CAMS Initiative Fund for Medical Sciences (2016-I2M-1-001 to XW). All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Latest global cancer data: cancer burden rises to 19.3 million new cases and 10.0 million cancer deaths in 2020. IARC. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei X, Liu F, Luo S, Sun Y, Zhu L, Su F, Chen K, Li S. Evaluation of guidelines regarding surgical treatment of breast cancer using the AGREE Instrument: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014883. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlbäck C, Ullmark JH, Rehn M, Ringberg A, Manjer J. Aesthetic result after breast-conserving therapy is associated with quality of life several years after treatment. Swedish women evaluated with BCCT.core and BREAST-Q™. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164:679–687. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heil J, Czink E, Golatta M, Schott S, Hof H, Jenetzky E, Blumenstein M, Maleika A, Rauch G, Sohn C. Change of aesthetic and functional outcome over time and their relationship to quality of life after breast conserving therapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AM, Meric-Bernstam F, Hunt KK, Thames HD, Oswald MJ, Outlaw ED, Strom EA, McNeese MD, Kuerer HM, Ross MI, Singletary SE, Ames FC, Feig BW, Sahin AA, Perkins GH, Schechter NR, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Breast conservation after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: the MD Anderson cancer center experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:2303–2312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Gnant M, Dubsky P, Loibl S, Colleoni M, Regan MM, Piccart-Gebhart M, Senn HJ, Thürlimann B, André F, Baselga J, Bergh J, Bonnefoi H, Brucker SY, Cardoso F, Carey L, Ciruelos E, Cuzick J, Denkert C, Di Leo A, Ejlertsen B, Francis P, Galimberti V, Garber J, Gulluoglu B, Goodwin P, Harbeck N, Hayes DF, Huang CS, Huober J, Hussein K, Jassem J, Jiang Z, Karlsson P, Morrow M, Orecchia R, Osborne KC, Pagani O, Partridge AH, Pritchard K, Ro J, Rutgers EJT, Sedlmayer F, Semiglazov V, Shao Z, Smith I, Toi M, Tutt A, Viale G, Watanabe T, Whelan TJ, Xu B. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1700–1712. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burstein HJ, Curigliano G, Loibl S, Dubsky P, Gnant M, Poortmans P, Colleoni M, Denkert C, Piccart-Gebhart M, Regan M, Senn HJ, Winer EP, Thurlimann B. Estimating the benefits of therapy for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2019. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1541–1557. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufmann M, Morrow M, von Minckwitz G, Harris JR. Locoregional treatment of primary breast cancer: consensus recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Cancer. 2010;116:1184–1191. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchholz TA, Lehman CD, Harris JR, Pockaj BA, Khouri N, Hylton NF, Miller MJ, Whelan T, Pierce LJ, Esserman LJ, Newman LA, Smith BL, Bear HD, Mamounas EP. Statement of the science concerning locoregional treatments after preoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer: a National Cancer Institute conference. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:791–797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brackstone M, Baldassarre FG, Perera FE, Cil T, Chavez Mac Gregor M, Dayes IS, Engel J, Horton JK, King TA, Kornecki A, George R, SenGupta SK, Spears PA, Eisen AF. Management of the axilla in early-stage breast cancer: Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) and ASCO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;39:3056–3082. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tadros AB, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, Rauch GM, Smith BD, Valero V, Black DM, Lucci A Jr, Caudle AS, DeSnyder SM, Teshome M, Barcenas CH, Miggins M, Adrada BE, Moseley T, Hwang RF, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM. Identification of patients with documented pathologic complete response in the breast after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for omission of axillary surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:665–670. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS, Roxburgh CS, Lynn P, Eaton A, Widmar M, Ganesh K, Yaeger R, Cercek A, Weiser MR, Nash GM, Guillem JG, Temple LKF, Chalasani SB, Fuqua JL, Petkovska I, Wu AJ, Reyngold M, Vakiani E, Shia J, Segal NH, Smith JD, Crane C, Gollub MJ, Gonen M, Saltz LB, Garcia-Aguilar J, Paty PB. Assessment of a watch-and-wait strategy for rectal cancer in patients with a complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:e185896. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monica Morrow MD. Will surgery be a part of breast cancer treatment in the future? Breast. 2019;48(Suppl 1):S110–S114. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(19)31136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gnant M, Harbeck N, Thomssen C. St. Gallen/Vienna 2017: a brief summary of the consensus discussion about escalation and de-escalation of primary breast cancer treatment. Breast Care (Basel) 2017;12:102–107. doi: 10.1159/000475698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rastogi P, Anderson SJ, Bear HD, Geyer CE, Kahlenberg MS, Robidoux A, Margolese RG, Hoehn JL, Vogel VG, Dakhil SR, Tamkus D, King KM, Pajon ER, Wright MJ, Robert J, Paik S, Mamounas EP, Wolmark N. Preoperative chemotherapy: updates of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocols B-18 and B-27. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:778–785. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prowell TM, Pazdur R. Pathological complete response and accelerated drug approval in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2438–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1205737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esserman LJ, Woodcock J. Accelerating identification and regulatory approval of investigational cancer drugs. JAMA. 2011;306:2608–2609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berruti A, Amoroso V, Gallo F, Bertaglia V, Simoncini E, Pedersini R, Ferrari L, Bottini A, Bruzzi P, Sormani MP. Pathologic complete response as a potential surrogate for the clinical outcome in patients with breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy: a meta-regression of 29 randomized prospective studies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:3883–3891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufmann M, Hortobagyi GN, Goldhirsch A, Scholl S, Makris A, Valagussa P, Blohmer JU, Eiermann W, Jackesz R, Jonat W, Lebeau A, Loibl S, Miller W, Seeber S, Semiglazov V, Smith R, Souchon R, Stearns V, Untch M, von Minckwitz G. Recommendations from an international expert panel on the use of neoadjuvant (primary) systemic treatment of operable breast cancer: an update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:1940–1949. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Sun M, Chang E, Lu CY, Chen HM, Wu SY. Pathologic response as predictor of recurrence, metastasis, and survival in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy and total mastectomy. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:3415–3427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, Mehta K, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, Bonnefoi H, Cameron D, Gianni L, Valagussa P, Swain SM, Prowell T, Loibl S, Wickerham DL, Bogaerts J, Baselga J, Perou C, Blumenthal G, Blohmer J, Mamounas EP, Bergh J, Semiglazov V, Justice R, Eidtmann H, Paik S, Piccart M, Sridhara R, Fasching PA, Slaets L, Tang S, Gerber B, Geyer CE, Pazdur R, Ditsch N, Rastogi P, Eiermann W, von Minckwitz G. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. The Lancet. 2014;384:164–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denkert C, von Minckwitz G, Darb-Esfahani S, Lederer B, Heppner BI, Weber KE, Budczies J, Huober J, Klauschen F, Furlanetto J, Schmitt WD, Blohmer JU, Karn T, Pfitzner BM, Kümmel S, Engels K, Schneeweiss A, Hartmann A, Noske A, Fasching PA, Jackisch C, van Mackelenbergh M, Sinn P, Schem C, Hanusch C, Untch M, Loibl S. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:40–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30904-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heil J, Sinn P, Richter H, Pfob A, Schaefgen B, Hennigs A, Riedel F, Thomas B, Thill M, Hahn M, Blohmer JU, Kuemmel S, Karsten MM, Reinisch M, Hackmann J, Reimer T, Rauch G, Golatta M. RESPONDER - diagnosis of pathological complete response by vacuum-assisted biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast Cancer - a multicenter, confirmative, one-armed, intra-individually-controlled, open, diagnostic trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:851. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4760-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, Roman L, Tseng LM, Liu MC, Lluch A, Staroslawska E, de la Haba-Rodriguez J, Im SA, Pedrini JL, Poirier B, Morandi P, Semiglazov V, Srimuninnimit V, Bianchi G, Szado T, Ratnayake J, Ross G, Valagussa P. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broglio KR, Quintana M, Foster M, Olinger M, McGlothlin A, Berry SM, Boileau JF, Brezden-Masley C, Chia S, Dent S, Gelmon K, Paterson A, Rayson D, Berry DA. Association of pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer with long-term outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:751–760. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spring LM, Gupta A, Reynolds KL, Gadd MA, Ellisen LW, Isakoff SJ, Moy B, Bardia A. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1477–1486. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nanda R, Liu MC, Yau C, Shatsky R, Pusztai L, Wallace A, Chien AJ, Forero-Torres A, Ellis E, Han H, Clark A, Albain K, Boughey JC, Jaskowiak NT, Elias A, Isaacs C, Kemmer K, Helsten T, Majure M, Stringer-Reasor E, Parker C, Lee MC, Haddad T, Cohen RN, Asare S, Wilson A, Hirst GL, Singhrao R, Steeg K, Asare A, Matthews JB, Berry S, Sanil A, Schwab R, Symmans WF, van’t Veer L, Yee D, DeMichele A, Hylton NM, Melisko M, Perlmutter J, Rugo HS, Berry DA, Esserman LJ. Effect of pembrolizumab plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy on pathologic complete response in women with early-stage breast cancer: an analysis of the ongoing phase 2 adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:676–684. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Consortium IST, Yee D, DeMichele AM, Yau C, Isaacs C, Symmans WF, Albain KS, Chen YY, Krings G, Wei S, Harada S, Datnow B, Fadare O, Klein M, Pambuccian S, Chen B, Adamson K, Sams S, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Magliocco A, Feldman M, Rendi M, Sattar H, Zeck J, Ocal IT, Tawfik O, LeBeau LG, Sahoo S, Vinh T, Chien AJ, Forero-Torres A, Stringer-Reasor E, Wallace AM, Pusztai L, Boughey JC, Ellis ED, Elias AD, Lu J, Lang JE, Han HS, Clark AS, Nanda R, Northfelt DW, Khan QJ, Viscusi RK, Euhus DM, Edmiston KK, Chui SY, Kemmer K, Park JW, Liu MC, Olopade O, Leyland-Jones B, Tripathy D, Moulder SL, Rugo HS, Schwab R, Lo S, Helsten T, Beckwith H, Haugen P, Hylton NM, Van’t Veer LJ, Perlmutter J, Melisko ME, Wilson A, Peterson G, Asare AL, Buxton MB, Paoloni M, Clennell JL, Hirst GL, Singhrao R, Steeg K, Matthews JB, Asare SM, Sanil A, Berry SM, Esserman LJ, Berry DA. Association of event-free and distant recurrence-free survival with individual-level pathologic complete response in Neoadjuvant Treatment of Stages 2 and 3 breast cancer: three-year follow-up Analysis for the I-SPY2 adaptively randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1355–1362. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, Eidtmann H, Fasching PA, Gerber B, Eiermann W, Hilfrich J, Huober J, Jackisch C, Kaufmann M, Konecny GE, Denkert C, Nekljudova V, Mehta K, Loibl S. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bossuyt V, Provenzano E, Symmans WF, Boughey JC, Coles C, Curigliano G, Dixon JM, Esserman LJ, Fastner G, Kuehn T, Peintinger F, von Minckwitz G, White J, Yang W, Badve S, Denkert C, MacGrogan G, Penault-Llorca F, Viale G, Cameron D Breast International Group-North American Breast Cancer Group (BIG-NABCG) collaboration. Recommendations for standardized pathological characterization of residual disease for neoadjuvant clinical trials of breast cancer by the BIG-NABCG collaboration. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1280–1291. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Negrão EMS, Souza JA, Marques EF, Bitencourt AGV. Breast cancer phenotype influences MRI response evaluation after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Radiol. 2019;120:108701. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumgartner A, Tausch C, Hosch S, Papassotiropoulos B, Varga Z, Rageth C, Baege A. Ultrasound-based prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Breast. 2018;39:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang K, Li J, Zhu Q, Chang C. Prediction of Pathologic complete response by ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:2603–2612. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S247279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Los Santos JF, Cantor A, Amos KD, Forero A, Golshan M, Horton JK, Hudis CA, Hylton NM, McGuire K, Meric-Bernstam F, Meszoely IM, Nanda R, Hwang ES. Magnetic resonance imaging as a predictor of pathologic response in patients treated with neoadjuvant systemic treatment for operable breast cancer. Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium trial 017. Cancer. 2013;119:1776–1783. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eun NL, Kang D, Son EJ, Park JS, Youk JH, Kim JA, Gweon HM. Texture analysis with 3.0-T MRI for association of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Radiology. 2020;294:31–41. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019182718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marinovich ML, Sardanelli F, Ciatto S, Mamounas E, Brennan M, Macaskill P, Irwig L, von Minckwitz G, Houssami N. Early prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer: systematic review of the accuracy of MRI. Breast. 2012;21:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Partridge SC, Zhang Z, Newitt DC, Gibbs JE, Chenevert TL, Rosen MA, Bolan PJ, Marques HS, Romanoff J, Cimino L, Joe BN, Umphrey HR, Ojeda-Fournier H, Dogan B, Oh K, Abe H, Drukteinis JS, Esserman LJ, Hylton NM. Diffusion-weighted MRI findings predict pathologic response in Neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer: the ACRIN 6698 multicenter trial. Radiology. 2018;289:618–627. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sener SF, Sargent RE, Lee C, Manchandia T, Le-Tran V, Olimpiadi Y, Zaremba N, Alabd A, Nelson M, Lang JE. MRI does not predict pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:903–910. doi: 10.1002/jso.25663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gampenrieder SP, Peer A, Weismann C, Meissnitzer M, Rinnerthaler G, Webhofer J, Westphal T, Riedmann M, Meissnitzer T, Egger H, Klaassen Federspiel F, Reitsamer R, Hauser-Kronberger C, Stering K, Hergan K, Mlineritsch B, Greil R. Radiologic complete response (rCR) in contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer predicts recurrence-free survival but not pathologic complete response (pCR) Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:19. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-1091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tahmassebi A, Wengert GJ, Helbich TH, Bago-Horvath Z, Alaei S, Bartsch R, Dubsky P, Baltzer P, Clauser P, Kapetas P, Morris EA, Meyer-Baese A, Pinker K. Impact of machine learning with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the breast for early prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival outcomes in breast cancer patients. Invest Radiol. 2019;54:110–117. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Hattali S, Vinnicombe SJ, Gowdh NM, Evans A, Armstrong S, Adamson D, Purdie CA, Macaskill EJ. Breast MRI and tumor biology predict axillary lymph node response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2019;19:91. doi: 10.1186/s40644-019-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Del Prete S, Caraglia M, Luce A, Montella L, Galizia G, Sperlongano P, Cennamo G, Lieto E, Capasso E, Fiorentino O, Aliberti M, Auricchio A, Iodice P, Addeo R. Clinical and pathological factors predictive of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a single center experience. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:3873–3879. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tasoulis MK, Lee HB, Yang W, Pope R, Krishnamurthy S, Kim SY, Cho N, Teoh V, Rauch GM, Smith BD, Valero V, Mohammed K, Han W, MacNeill F, Kuerer HM. Accuracy of post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy image-guided breast biopsy to predict residual cancer. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:e204103. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heil J, Kummel S, Schaefgen B, Paepke S, Thomssen C, Rauch G, Ataseven B, Grosse R, Dreesmann V, Kuhn T, Loibl S, Blohmer JU, von Minckwitz G. Diagnosis of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer by minimal invasive biopsy techniques. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1565–1570. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heil J, Schaefgen B, Sinn P, Richter H, Harcos A, Gomez C, Stieber A, Hennigs A, Rauch G, Schuetz F, Sohn C, Schneeweiss A, Golatta M. Can a pathological complete response of breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy be diagnosed by minimal invasive biopsy? Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heil J, Pfob A, Sinn HP, Rauch G, Bach P, Thomas B, Schaefgen B, Kuemmel S, Reimer T, Hahn M, Thill M, Blohmer JU, Hackmann J, Malter W, Bekes I, Friedrichs K, Wojcinski S, Joos S, Paepke S, Ditsch N, Rody A, Große R, van Mackelenbergh M, Reinisch M, Karsten M, Golatta M. Diagnosing pathologic complete response in the breast after neoadjuvant systemic treatment of breast cancer patients by minimal invasive biopsy: oral presentation at the san antonio breast cancer symposium on Friday, December 13, 2019, Program Number GS5-03. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuerer HM, Rauch GM, Krishnamurthy S, Adrada BE, Caudle AS, DeSnyder SM, Black DM, Santiago L, Hobbs BP, Lucci A Jr, Gilcrease M, Hwang RF, Candelaria RP, Chavez-MacGregor M, Smith BD, Arribas E, Moseley T, Teshome M, Miggins MV, Valero V, Hunt KK, Yang WT. A clinical feasibility trial for identification of exceptional responders in whom breast cancer surgery can be eliminated following neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Ann Surg. 2018;267:946–951. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Loevezijn AA, van der Noordaa MEM, van Werkhoven ED, Loo CE, Winter-Warnars GAO, Wiersma T, van de Vijver KK, Groen EJ, Blanken-Peeters C, Zonneveld B, Sonke GS, van Duijnhoven FH, Vrancken Peeters M. Minimally invasive complete response assessment of the breast after neoadjuvant systemic therapy for early breast cancer (MICRA trial): interim analysis of a multicenter observational cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:3243–3253. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09273-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Noordaa MEM, van Duijnhoven FH, Loo CE, van Werkhoven E, van de Vijver KK, Wiersma T, Winter-Warnars HAO, Sonke GS, Vrancken Peeters M. Identifying pathologic complete response of the breast after neoadjuvant systemic therapy with ultrasound guided biopsy to eventually omit surgery: study design and feasibility of the MICRA trial (Minimally Invasive Complete Response Assessment) Breast. 2018;40:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tasoulis MK, Lee HB, Yang WT, Pope R. Abstract GS5-04: Accuracy of post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy image-guided breast biopsy to predict the presence of residual cancer: a multi-institutional pooled analysis. In Abstracts: 2019 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 10-14, 2019; San Antonio, Texas. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Francis A, Herring K, Molyneux R, Jafri M, Trivedi S, Shaaban A, Rea D. Abstract P5-16-14: NOSTRA PRELIM: a non randomised pilot study designed to assess the ability of image guided core biopsies to detect residual disease in patients with early breast cancer who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy to inform the design of a planned trial. Cancer Research. 2017;77:P5-16-14-P15-16-14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sutton EJ, Braunstein LZ, El-Tamer MB, Brogi E, Hughes M, Bryce Y, Gluskin JS, Powell S, Woosley A, Tadros A, Sevilimedu V, Martinez DF, Toni L, Smelianskaia O, Nyman CG, Razavi P, Norton L, Fung MM, Sedorovich JD, Sacchini V, Morris EA. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging-guided biopsy to verify breast cancer pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2034045. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee HB, Han W, Kim SY, Cho N, Kim KE, Park JH, Ju YW, Lee ES, Lim SJ, Kim JH, Ryu HS, Lee DW, Kim M, Kim TY, Lee KH, Shin SU, Lee SH, Chang JM, Moon HG, Im SA, Moon WK, Park IA, Noh DY. Prediction of pathologic complete response using image-guided biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients selected based on MRI findings: a prospective feasibility trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;182:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denkert C, Loibl S, Noske A, Roller M, Müller BM, Komor M, Budczies J, Darb-Esfahani S, Kronenwett R, Hanusch C, von Törne C, Weichert W, Engels K, Solbach C, Schrader I, Dietel M, von Minckwitz G. Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:105–113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bownes RJ, Turnbull AK, Martinez-Perez C, Cameron DA, Sims AH, Oikonomidou O. On-treatment biomarkers can improve prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:73. doi: 10.1186/s13058-019-1159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pu S, Wang K, Liu Y, Liao X, Chen H, He J, Zhang J. Nomogram-derived prediction of pathologic complete response (pCR) in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT) BMC Cancer. 2020;20:1120. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07621-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hwang HW, Jung H, Hyeon J, Park YH, Ahn JS, Im YH, Nam SJ, Kim SW, Lee JE, Yu JH, Lee SK, Choi M, Cho SY, Cho EY. A nomogram to predict pathologic complete response (pCR) and the value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4981-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magbanua MJM, Swigart LB, Wu HT, Hirst GL, Yau C, Wolf DM, Tin A, Salari R, Shchegrova S, Pawar H, Delson AL, DeMichele A, Liu MC, Chien AJ, Tripathy D, Asare S, Lin CJ, Billings P, Aleshin A, Sethi H, Louie M, Zimmermann B, Esserman LJ, van’t Veer LJ. Circulating tumor DNA in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer reflects response and survival. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magbanua MJM, Li W, Wolf DM, Yau C, Hirst GL, Swigart LB, Newitt DC, Gibbs J, Delson AL, Kalashnikova E, Aleshin A, Zimmermann B, Chien AJ, Tripathy D, Esserman L, Hylton N, van’t Veer L. Circulating tumor DNA and magnetic resonance imaging to predict neoadjuvant chemotherapy response and recurrence risk. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7:32. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Ritz LJ, Farrell JB, Sladek ML, Lally RM. Quality of life after breast carcinoma surgery: a comparison of three surgical procedures. Cancer. 2001;91:1238–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S, Zhang Y, Yang X, Fan L, Qi X, Chen Q, Jiang J. Shrink pattern of breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and its correlation with clinical pathological factors. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:166. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wimmer K, Bolliger M, Bago-Horvath Z, Steger G, Kauer-Dorner D, Helfgott R, Gruber C, Moinfar F, Mittlböck M, Fitzal F. Impact of surgical margins in breast cancer after preoperative systemic chemotherapy on local recurrence and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1700–1707. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08089-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ataseven B, Lederer B, Blohmer JU, Denkert C, Gerber B, Heil J, Kühn T, Kümmel S, Rezai M, Loibl S, von Minckwitz G. Impact of multifocal or multicentric disease on surgery and locoregional, distant and overall survival of 6,134 breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1118–1127. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tyler S, Truong PT, Lesperance M, Nichol A, Baliski C, Warburton R, Tyldesley S. Close margins less than 2 mm are not associated with higher risks of 10-year local recurrence and breast cancer mortality compared with negative margins in women treated with breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101:661–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeSnyder SM, Hunt KK, Dong W, Smith BD, Moran MS, Chavez-MacGregor M, Shen Y, Kuerer HM, Lucci A. American Society of Breast Surgeons’ Practice Patterns After Publication of the SSO-ASTRO-ASCO DCIS consensus guideline on margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2965–2974. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biglia N, Ponzone R, Bounous VE, Mariani LL, Maggiorotto F, Benevelli C, Liberale V, Ottino MC, Sismondi P. Role of re-excision for positive and close resection margins in patients treated with breast-conserving surgery. Breast. 2014;23:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ring A, Webb A, Ashley S, Allum WH, Ebbs S, Gui G, Sacks NP, Walsh G, Smith IE. Is surgery necessary after complete clinical remission following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer? J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:4540–4545. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mauriac L, MacGrogan G, Avril A, Durand M, Floquet A, Debled M, Dilhuydy JM, Bonichon F. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for operable breast carcinoma larger than 3 cm: a unicentre randomized trial with a 124-month median follow-up. Institut Bergonié Bordeaux Groupe Sein (IBBGS) Ann Oncol. 1999;10:47–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1008337009350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scholl SM, Pierga JY, Asselain B, Beuzeboc P, Dorval T, Garcia-Giralt E, Jouve M, Palangié T, Remvikos Y, Durand JC, et al. Breast tumor response to primary chemotherapy predicts local and distant control as well as survival. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1969–1975. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Daveau C, Savignoni A, Abrous-Anane S, Pierga JY, Reyal F, Gautier C, Kirova YM, Dendale R, Campana F, Fourquet A, Bollet MA. Is radiotherapy an option for early breast cancers with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clouth B, Chandrasekharan S, Inwang R, Smith S, Davidson N, Sauven P. The surgical management of patients who achieve a complete pathological response after primary chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Özkurt E, Sakai T, Wong SM, Tukenmez M, Golshan M. Survival outcomes for patients with clinical complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: is omitting surgery an option? Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:3260–3268. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pfob A, Sidey-Gibbons C, Lee HB, Tasoulis MK, Koelbel V, Golatta M, Rauch GM, Smith BD, Valero V, Han W, MacNeill F, Weber WP, Rauch G, Kuerer HM, Heil J. Identification of breast cancer patients with pathologic complete response in the breast after neoadjuvant systemic treatment by an intelligent vacuum-assisted biopsy. Eur J Cancer. 2021;143:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:500–515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:567–575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pilewskie M, Morrow M. Axillary nodal management following neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:549–555. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, Fleige B, Hausschild M, Helms G, Lebeau A, Liedtke C, von Minckwitz G, Nekljudova V, Schmatloch S, Schrenk P, Staebler A, Untch M. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boughey JC, Ballman KV, Le-Petross HT, McCall LM, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, Wilke LG, Taback B, Feliberti EC, Hunt KK. Identification and resection of clipped node decreases the false-negative rate of sentinel lymph node surgery in patients presenting with node-positive breast cancer (T0-T4, N1-N2) who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy: results from ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) Ann Surg. 2016;263:802–807. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]