Abstract

Background

Concepts of moral distress (MD) among physicians have evolved and extend beyond the notion of psychological distress caused by being in a situation in which one is constrained from acting on what one knows to be right. With many accounts involving complex personal, professional, legal, ethical and moral issues, we propose a review of current understanding of MD among physicians.

Methods

A systematic evidence-based approach guided systematic scoping review is proposed to map the current concepts of MD among physicians published in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, SCOPUS, ERIC and Google Scholar databases. Concurrent and independent thematic and direct content analysis (split approach) was conducted on included articles to enhance the reliability and transparency of the process. The themes and categories identified were combined using the jigsaw perspective to create domains that form the framework of the discussion that follows.

Results

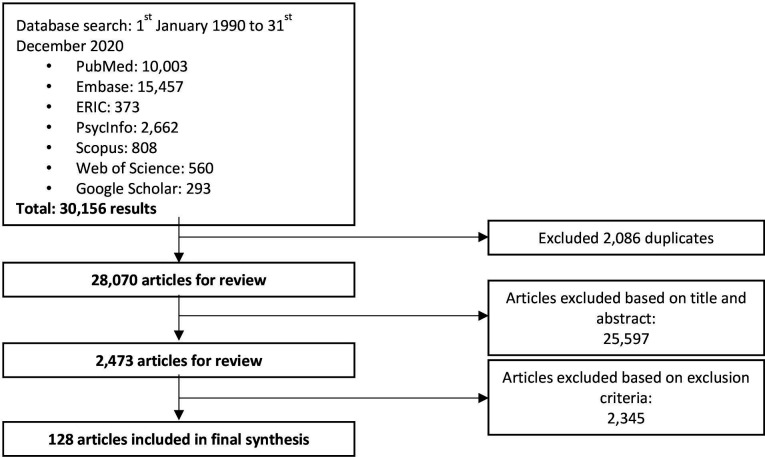

A total of 30 156 abstracts were identified, 2473 full-text articles were reviewed and 128 articles were included. The five domains identified were as follows: (1) current concepts, (2) risk factors, (3) impact, (4) tools and (5) interventions.

Conclusions

Initial reviews suggest that MD involves conflicts within a physician’s personal beliefs, values and principles (personal constructs) caused by personal, ethical, moral, contextual, professional and sociocultural factors. How these experiences are processed and reflected on and then integrated into the physician’s personal constructs impacts their self-concepts of personhood and identity and can result in MD. The ring theory of personhood facilitates an appreciation of how new experiences create dissonance and resonance within personal constructs. These insights allow the forwarding of a new broader concept of MD and a personalised approach to assessing and treating MD. While further studies are required to test these findings, they offer a personalised means of supporting a physician’s MD and preventing burn-out.

Keywords: medical education & training, mental health, education & training (see medical education & training)

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The systematic evidence-based approach (SEBA) methodology allows study of data from diverse methodological sources, settings, physician populations and specialties.

The SEBA methodology adopts the structure of systematic reviews and flexibility of narrative reviews to synthesis a reproducible and accountable evaluation of all sources of data.

The clinically evidenced ring theory of personhood (RToP) allows the transparent, reproducible and personalised analysis of concepts of moral distress (MD) among physicians.

Use of the RToP and the SEBA methodology to study MD is novel and require further study.

Introduction

Care and resource limitations and concerns over compromised patient care amidst the COVID-19 pandemic have fanned reports of moral distress (MD) among healthcare professionals (HCPs) in medicine, pharmacy, allied health, psychology and social work.1–11 However, while this increase in reports of MD is unsurprising, the diverse nature of accounts of MD among HCPs suggests that concerns extend beyond Jameton’s original notion of psychological distress caused by being in a situation in which one is constrained from acting on what one knows to be right.6–11

With data suggesting that concepts of MD may also differ between HCPs by virtue of their practice and settings, we focus on the study of MD as conceived by physicians. Indeed, current accounts of MD among physician12–27 suggest MD is a product of conflicts between prevailing values, beliefs and principles (personal constructs) drawn from self-concepts of personhood and ethical, practical,28 29 clinical, moral30 and professional31 influences within a particular setting or clinical interaction (situational constructs). To better appreciate conflicts between personal and situational constructs that predispose to burnout and compromised patient care a holistic appreciation of MD among physicians is required. It is hoped that better understanding of MD among physicians will help direct personalised, appropriate, timely and holistic support to physicians facing MD and thwart threats of burn-out and resignations among physicians.

Rationale for this review

A systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to map the diverse conceptions of MD among physicians. Indeed, the notion that MD may take a different shape among physicians than across other HCPs may not be surprising given that Jameton’s original concept was conceived within the nursing setting replete with its hierarchical and practice culture.6 A specialty-specific account of MD will guide timely, comprehensive, and personalised appraisal, and support for physicians in need.

Theoretical lens

Two considerations guided the selection of an appropriate theoretical lens for this review. One, MD is a sociocultural construct deserving of holistic study of the physician’s practice, cultural, social, professional, academic and research circumstances including their healthcare and education systems.2 32–34 Acknowledging MD as a sociocultural construct35 underlines the need to consider the individual physician’s moral, ethical and professional beliefs, values, and principles that underpin their thinking, attitudes, decision-making and actions.36 There must also be due consideration of their spiritual, emotional, relational and social considerations which similarly impact their sensitivity or awareness of occurrences and circumstances that could provoke MD in them. In addition, recognising MD’s complex sociocultural nature underscores the importance of appreciating the physician’s narratives, competencies, experiences, reflections, abilities and available coping and support mechanisms that provide MD with its personalised and evolving nature.

Two, with a physician’s personal, moral, ethical and professional beliefs, values, and principles informed by their self-concepts of identity and personhood or ‘what makes you, you’,36 the link between personalised concepts37–39 of MD and self-concepts of personhood become clearer. Ho et al38 Kuek et al3 Chan and Chia40 and Huang et al41 provide clinical evidence of these ties between self-concepts of personhood and identity using the ring theory of personhood (RToP) to study the experiences of physicians, nurses and medical students caring for terminally ill patients and confronting the death of their patients. Similarly Ho et al’s42 study of how senior palliative care and oncology nurses at a cancer centre cope with caring for dying patients and their distress in facing the death of their patients, suggest that psychological distress akin to recent accounts of MD may be better understood through the employ of the RToP framework.3 38 40 41

These two considerations underpin the reason for the employ of the RToP as the theoretical lens for this review.

The Ring Theory of Personhood

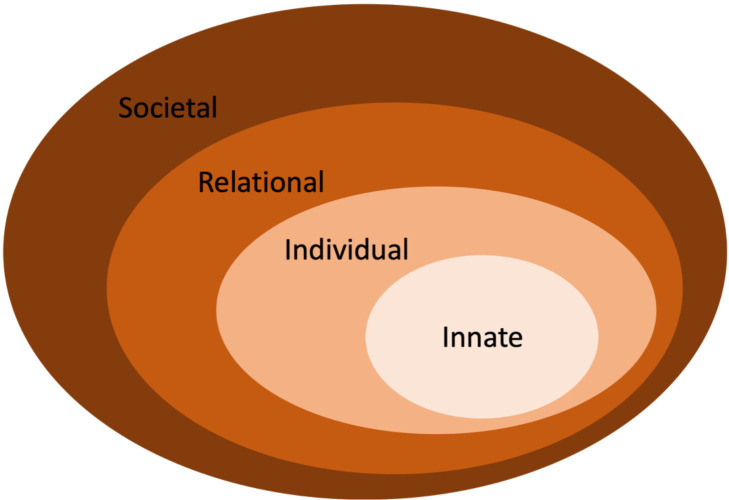

The RToP suggests that personhood is made up of four domains. These domains include the (1) innate ring, (2) individual ring, (3) relational ring and the (4) societal ring as shown in figure 1.36 Each ring contains a set of beliefs, values, principles, thoughts, attitudes, familial customs, cultural norms, roles and responsibilities that gives rise to corresponding identities. Though each of these identities is unique, how they are manifest in different settings and circumstances is dependent on the individual underlining the need to appreciate better the context and setting and the physician’s particular circumstances (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ring theory of personhood.

The innate ring builds on the notion that all human beings are deserving of personhood ‘irrespective of clinical status, culture, creed, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or appearance’ by their genetic propensity to being a human and or their divine connections.36 38 The innate ring gives rise to the Innate Identity that consists of one’s religious, cultural and societal-inspired values, principles and beliefs.3 19 26 30 43–45 These values dictate the individual’s perspective and expectations on care determinations, end-of-life care and withdrawing and withholding treatment.28 29 46

The individual ring represents the features of conscious functions, including their thoughts, feelings, actions and abilities.36 The identity formed within the individual ring is informed by the values, beliefs and principles based on conscious function and the other three rings. Balancing these factors in the face of perceptual, experiential, psychoemotional and contextual considerations; prevailing ethical, moral, legal, professional and sociocultural factors; as well as personal choices, biases and decision-making styles reveals the influence of individual circumstances, choices, values, beliefs, principles, biases, norms, mores and preferences. It also demonstrates that self-concepts of personhood and identity are deeply intertwined and highly individualised.

The relational ring comprises the close personal relationships that individuals hold dear to themselves. This may include family, friends and colleagues who play a vital role in their lives.36 The Relational Identity is shaped by the individual’s values, beliefs and principles derived from the nature, values, effects and ramifications of these relationships.46 47

The societal ring is the outermost ring that contains the Societal Identity formed by how the individual views their societal position, roles and responsibilities and societal expectations, professional standards and the norms, laws, and obligations of the roles that the individual plays.36

Kuek et al note that disharmony and dyssynchrony arise when values, principles and beliefs introduced within a ring or between the different rings are in ‘tension’ with current concepts, values, principles and beliefs driven by prevailing concepts of personhood. If disharmony and dyssynchrony are not addressed appropriately, timely and in a personalised manner distress can arise. It is posited that when the sources of disharmony and dyssynchrony are understood, the means to resolve MD become clearer.3 36

Methodology

Krishna’s systematic evidence-based approach (SEBA) is adopted to guide this SSR (SSR in SEBA) is used to map what is known about MD on physicians.48–51 This SSR aims to identify existing information, key characteristics and knowledge gaps in the concept of MD in current literature. This SSR in SEBA’s constructivist ontological perspective and relativist lens recognises MD as a sociocultural construct.52–55 It also facilitates the systematic extraction, synthesis and summary of application and actionable data across a variety of study formats and overcomes the absence of a common understanding of MD.

To provide a balanced review, this SSR in SEBA is overseen by an expert team comprised of medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), and local education experts and clinicians at NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School. The expert team guide, oversee and support the 6 stages of SEBA to enhance the reproducibility and accountability of the process.3 38 48–51 56–62

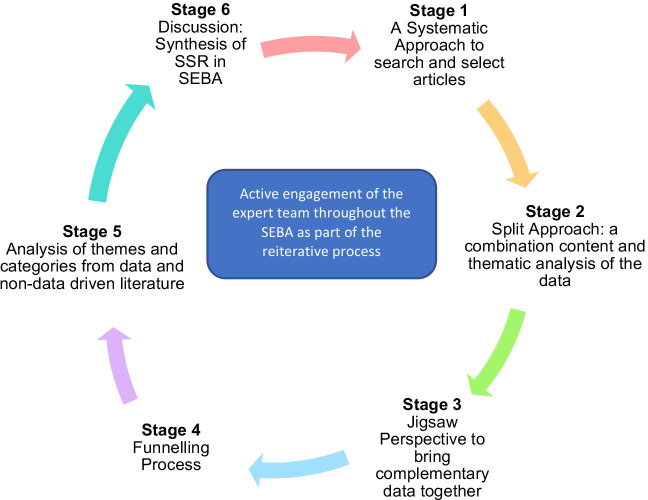

The SEBA process comprises of six stages, namely—(1) systematic approach, (2) split approach, (3) jigsaw perspective, (4) funnelling process, (5) analysis of data and non-data-driven literature and (6) discussion (figure 2).

Figure 2.

SSR in SEBA process. SEBA, systematic evidence-based approach; SSR, systematic scoping review.

Stage 1 of SEBA: systematic approach

Determining the title and background of the review

Guided by the expert team, the research team curated the primary research question to be ‘How do physicians conceptualise MD?’. The secondary research questions were ‘What are the characteristics of MD?’, ‘What are the sources and consequences of MD on physicians?’ and ‘What are the tools and interventions used to assess and manage MD on physicians?’. These questions were designed based on the population, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria (PICo), and were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist.63 64

Inclusion criteria

The PICo format (table 1) was employed to guide the research process.

Table 1.

PICo, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria applied to database search ring theory of personhood

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

| Population | All physicians | Healthcare professionals such as nurses, allied health workers and non-medical workers (eg, veterinary, dentistry, clinical and translational science, alternative and traditional medicine) |

| Interest | Reports of MD | Focus on phenomenon other than MD (eg, demoralisation) |

| Context | Clinical medicine | N/A |

| Study design | Articles in English or translated to English Time of publication between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2020 Mixed-methods research, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, descriptive papers, opinions, letters, commentaries and editorials |

Books, book chapters and or theses |

MD, moral distress.

Searching

Twelve members of the research team carried out independent searches that were conducted on seven bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, SCOPUS, ERIC and Google Scholar) between 17 December 2021 and 17 January 2022. The search process was guided by three experienced senior researchers who are well-versed in the use of the SEBA methodology and SSRs. Each senior researcher met with a team of four medical students to guide them on the search of the seven databases. This method was adopted to facilitate the training of amateur researchers and ensure that at least two independent teams were reviewing each database. Each team met regularly to discuss their findings. The senior researcher and medical students met online to compare their findings of the first 100 articles on their assigned database. Following this, teams met at specific time points after reviewing a predetermined number of included articles. Concerns and opinions were exchanged while simultaneously advancing the team’s knowledge of the area of study and the research process. Interrater reliability was not evaluated.

In keeping with Pham and Raji’s recommendations, searches were restricted to articles published from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2020 to sustain the research process and adapt to existing time and manpower limitations.65 Quantitative, qualitative and mixed research methodologies that met the inclusion criteria were included. The full search strategy can be found in online supplemental material A.

bmjopen-2022-064029supp001.pdf (113.5KB, pdf)

Extracting and charting

Each team reviewed the titles and abstracts and discussed their findings at regularly scheduled meetings. The teams employed Sandelowski and Barroso’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final list of titles to be reviewed.66 67 The teams repeated this process independently. They studied all the full-text articles on the final list of titles and curated their list of articles to be included. The findings were then discussed via online meetings and consensus was achieved on the final list of articles to be analysed.

Stage 2 of SEBA: split approach

To enhance the reliability of the data analysis, the ‘split approach’ was used.65–71 Three groups of researchers analysed the included articles independently.

The first team summarised and tabulated the included full-text articles in keeping with recommendations set out by Wong et al’s RAMESES publication standards and Popay et al’s ‘Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews’.72 73 The tabulated summaries functioned to ensure that important elements of the articles were not lost (online supplemental material B).

bmjopen-2022-064029supp002.pdf (898KB, pdf)

Simultaneously, the second team analysed the included articles using Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis.74 In phase 1, the team conducted independent reviews and ‘actively’ read the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data. In phase 2, ‘codes’ were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning and collated into a codebook to code and analyse the rest of the articles using an iterative step-by-step process.75 As new codes emerged, these were associated with previous codes and concepts. In phase 3, an inductive approach allowed themes to be ‘defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification’.76 In phase 4, the themes were refined to best represent the entire data set and discussed. In phase 5, the research team discussed their independent findings and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to determine the final list of themes (online supplemental material C).67

bmjopen-2022-064029supp003.pdf (226.1KB, pdf)

The third team employed Hsieh and Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis to analyse the included articles.77 This involved ‘identifying and operationalising a priori coding categories’.77–82 In the first stage, the team drew categories from ‘Understanding the fluid nature of personhood—the RToP’ to guide the coding of the articles in the next stage.36 Any data not captured by these codes were assigned a new code (online supplemental material C).81

Stage 3 of SEBA: jigsaw perspective

The expert and research teams reviewed the categories and themes as part of SEBA’s reiterative process. The themes and categories were viewed as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that saw overlapping/complementary pieces combined to create a bigger piece of the puzzle referred to as themes/categories.

The jigsaw perspective employed phases 4–6 of France, Uny’s adaptation of Noblit, Hare’s seven phases of meta-ethnography to create themes/categories.83 84 In keeping with phase 4 of France, Uny’s approach, the themes and categories identified during the split approach were grouped together according to their focus. These groupings of themes and categories were then contextualised through the review of articles from which they were drawn from. As per France, Uny’s approach, reciprocal translation was used to determine if the themes and categories could be used interchangeably.

Stage 4 of SEBA: funnelling

As per phases 3–5 of France’s approach, the funnelling process begins with juxtaposing the themes/categories identified in the jigsaw approach and the key messages identified in the tabulated summaries to create domains.83 The funnelled domains created from this process forms the basis of the discussion’s ‘line of argument’ in stage 6 of SEBA.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this study.

Results

A total of 30 156 abstracts were identified from 7 databases, 2473 articles were reviewed and 128 articles were included as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow chart.

The jigsaw process saw the themes identified which were characterisation, causes, influences, impacts, tools and interventions of MD combined with the categories identified which were the innate ring, the individual ring, the relational ring, the societal ring, disharmony and dyssynchrony. The five funnelled domains identified were as follows: (1) current concepts, (2) risk factors, (3) impact, (4) tools and (5) interventions.

The five funnelled domains provide a clinical depiction of current reports of the physician’s experience of MD and addresses the paucity of knowledge of MD through the lens of the RToP.

Domain 1: current concepts

Some included articles adopt Jameton’s definition, which assumes the physician has knowledge of the right course of action but is unable to follow through with that course of action.1 2 32 34 85–164

Most included articles however chose to adapt Jameton’s definition, due to contextual165 166 and practice differences between nurses and physicians.89 99 106 113 Greater awareness of MD, a general frustration with the medical hierarchy that often does not consider a nurse’s view or limits their input in care determinations2 98 119 124 129 161 167 and the presence of support mechanisms168 also encouraged nurses to report more episodes of MD2 85 88 89 98 99 112 116 119 121–126 129 161 169 170 than their physician colleagues.115 116 120 159 160 167

Still other included articles afforded alternate definitions.89 99 106 113 Abbasi et al’s89 definition of MD focused on personal powerlessness to ‘preserve all interests and values at stake’. Green et al106 suggest that MD was akin to ‘an attack on one’s integrity’ and is not just about ‘feeling badly’. Varcoe et al33 acknowledge the influence of the community and institution on MD. Other reasons for a new definition for MD include acknowledging resource limitations and allocations, concerns over the quality of care, ethical dilemmas such as prognostication and end-of-life matters, and confrontations with family, patients and other HCPs.2 33 98 116 118 119 124 129 161 167

Additionally, analysis of accounts of MD through the lens of the RToP15 highlights current failures to recognise conflict between the rings of personhood (dyssynchrony) or within a ring (disharmony) as a source of MD.3 38

Dyssynchrony

Perhaps the most common source of MD is dyssynchrony. The most common form of dyssynchrony is a conflict between personal and societal expectations, values, behaviours and practices. This may be a conflict between innate and/or individual rings nd the societal ring. Another example is when the healthcare team limits or withdraws care or facilitates abortions when it runs against the physician’s religious beliefs.105 139 166 171 Similarly, Daniel’s172 experiences rationing oxygen to the ‘most medically salvageable’ patient in the ICU after the 2010 Haiti earthquake saw her question whether her decision was ‘a medical judgement based on a comorbidity or a value judgement based on (her) own latent biases’.172 These accounts underline the influence of individual experiences, upbringing, religious beliefs and sociocultural background on the occurrence and or perception of MD among physicians.

Disharmony

Accounts of disharmony often revolve around conflicts between professional obligations. de Boer et al’s study of MD found disharmony arose physicians and nurses questioned the extent of care afforded patients at a neonatal ICU and if they were an example of overtreatment by the team.116 Brown-Saltzman’s qualitative study on MD reported disharmony within the innate rings where there was a conflict between ‘sanctity of life and the sanctity of choice’ in a patient’s care.113

Domain 2: risk factors

Risk factors for MD were also identified across the rings of personhood.

Innate ring

Women are more likely to report MD and also suffer greater emotional exhaustion and ethical issues.2 88 91 107 108 132 159 173 The propensity for younger physicians to report MD may relate their limited role in care determinations and treatment decisions within the medical hierarchy.88–91 108 174

Individual ring

Personality traits and values such as a deep sense of service and caregiving, a lack of assertiveness, poor self-esteem and lack of flexibility predispose to MD.1 94 117 150 151

Relational ring

Marital conflict, family disruption and feelings of isolation from family and friends lead to a poorly supported physician at risk of MD.88 102 113 139 160 175 176

Societal ring

Contextual factors such as the employ of perceived futile care,2 97 99 100 108 115 116 120 121 130 131 134 157 161 162 167 171 177–179 resource constraints leading to prioritisation of care between patients,4 85 91 97 99 100 107 108 114 116 117 121 132 135–137 140 143 144 164 166 167 180–185 institutional rules, policies and organisational pressures that prevent physicians from providing appropriate patient care,4 85 94 99 113 114 120 124 140 147 150 151 153 166 168 175 177 180 185 186 and the disconnect between perceived ethical practice and delivered clinical practice predispose to MD.97 109 112 152 160 187

Domain 3: impact

MD often manifests as anger, frustration, sadness, depression or guilt.1 89 90 94 97 104–107 113 115 119 120 122 123 136 137 143 151 154 157 160 164 168 173 188 A sense of powerlessness and the erosion of individual values and moral integrity may culminate in the intention or act of leaving one’s job,1 94 107 113 121 129 141 143 154 164 168 189 medical errors,1 2 88 89 96 98 99 101 107 108 112 113 115–117 119–126 136 148 151 155 159 161 164 167 168 170 176 190 191 a compromise in patient care1 34 90 111 112 116 119 120 122 124 144 151 159 160 165 169 192 or the transfer of the physician’s emotions onto patients.1 85 97 102 112 119 122 129 137 141 147 149 161 164 168 Multiple unresolved episodes of MD may lead to more severe consequences.85 86

Howe; however, proposes that MD could be an ‘alarm signal’ to alert physicians to reflect, develop and engage others for guidance and support32 104 114 and trigger more inclusive discussions and the re-evaluation of care plans.34 87 98 109 111 130 138 149 158 193

Domain 4: tools

The MD Scale and its successor the Standard Hamric MD Scale-Revised (MDS-R) is the most commonly used tool to evaluate MD.1 2 85 88–91 96 99–101 103 107 108 111 115 117 120 121 127 132 142 151 155 156 160 161 165 179 192 194 These tools have been employed in clinical situations, such as end-of-life care, staffing, resources, communication and decision-making to determine the presence and extent of a physician’s MD. Other tools such as the Measure of MD for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) determine the presence of MD while the MD thermometer assesses the intensity of MD.96 127 130 151 MDS-R and MMD-HP also evaluate the sources of conflict reviewing conflicts between personal and professional expectations on conduct, and professional and familial sources of MD.89 98 161 195

Domain 5: interventions

Management of MD may be categorised into individual coping mechanisms and organisational interventions. To counter negative coping strategies such as distraction and excessive alcohol consumption,97 119 132 mindfulness training, meditation, healing rituals, exercise, naming the feeling,97 119 129 132 175 189 193 rationalisation and positive reframing have employed to manage MD.87 106 126 129 153 158

Organisational interventions include team-based discussions,2 88 95 97 100 104 105 119 120 124 127 129 132 135 139 144 creating a conducive environment,158 196 increasing education and counselling,4 88–90 104 105 151 175 191 and providing an MD consultation service have been suggested.105 150

Stage 5 of SEBA: analysis of evidence-based and non-data-driven literature

The majority of included articles were data driven (83 out of 128). However, concerns that evidence taken from non-data-driven articles (position, perspective, conference, reflective and opinion papers, editorials, commentaries, letters, posters, oral presentations, forum discussions, interviews, blogs, governmental reports, policy statements and surveys) which are often neither evidenced-based nor quality assessed, could bias the discussion saw the team thematically analyse the data from data driven and non-data driven articles separately. The themes from both groups were similar emphasising that the non-data-based articles did not bias the analysis untowardly.

To further advance the transparency and accountability of this review quality appraisals using MERSQI and COREQ were conducted (online supplemental material B).197 198

Stage 6 of SEBA: synthesis of SSR in SEBA

The synthesis of the discussion was guided by the Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis statement and Best Evidence Medical Education Collaboration guide.199 200

Discussion

In answering its primary and secondary research questions, this SSR in SEBA suggests that physicians’ concepts of MD extends beyond Jameton’s notion of ‘(A) the psychological distress of; (B) being in a situation in which one is constrained from acting and (C) on what one knows to be right’.1 2 6–10 32 34 85–118 120–123 125–164 Indeed this SSR in SEBA reveals that physicians also include contextual, practice, environmental, cultural, community and institutional factors, resource limitations and allocations, quality of care and ethical dilemmas2 33 108 117 118 125 132 138 143 148 180 186 and personal factors including feelings of powerlessness and ‘attacks’ on their integrity,89 99 106 113 personal values,116 professional codes172 and existential beliefs105 139 166 171 as situational constructs that shape their personal constructs within their rings of personhood.3 38 Personal factors including gender, specialty, personality traits, principles, values, beliefs, experiences, circumstances and the availability of support mechanisms psychoemotional states, familial issues, and sociocultural factors also influences the perceptions and responses to MD.2 6–11 97 99 100 108 115 116 120 121 130 131 134 157 161 162 167 171 177–179 This combination of personal and situational constructs may explain the individual variations in the nature, intensity, duration and onset of anger, frustration, sadness, depression and or guilt1 89 90 94 97 104–107 113 115 119 120 122 123 136 137 143 151 154 157 160 164 168 173 188 and the presence of ‘distress’ even when the ‘right’ action is taken2 85 89 94 98 105 116 118 119 124 129 133 140 141 146 151 156 157 161 164 165 167 172 177 179 201 202 among reports of MD. Insights into the effects of personal and situational construct on the physician’s RToP and the resultant dyssynchrony and or disharmony also help early identification of risk factors for MD, guide personalised support, provide the selection of appropriate interventions to attenuate these issues and monitor the physician’s progress over time.

These insights allow the forwarding of a clinically relevant evidenced based definition that characterises MD among physicians as ‘cognitive, existential and or emotional distress that arises with recognition that patient care may or has been compromised. Sources of MD extend beyond organisational limitations and include dissonance between a physician’s values, beliefs and or principles and clinical, research, administrative practices that threaten the physician’s personal, professional, spiritual, moral, ethical, relational and societal identity and self-concepts of personhood. MD is also informed by individual narratives, personal characteristics, coping, abilities, reflections, emotional states, and relational, psychosocial, financial, societal and contextual considerations and circumstances’. We believe that this definition of MD for physicians and data from this SSR in SEBA allows the forwarding of a holistic and clinically relevant framework that could guide the design of a tool to better assess MD in the absence of a longitudinal assessment tool that considers environmental, contextual, experiential, personal and psychoemotional factors.32

The RToP-MD reflective tool

The data from this SSR in SEBA lays the foundation for a new approach to assessing MD. The RToP-MD reflective tool (table 2) acts as a stimulus for reflection on dyssynchrony and disharmony and personalised study of MD with a trusted and trained senior clinician. This will provide personalised and timely support to the physician as they reframe, reflect and integrate new insights into their practice (figure 4).

Table 2.

RToP-MD tool (with sample responses)

| Demographics | |

| Age | 27 years old |

| Years of clinical experience | 3 years |

| Gender | Female |

| Position | Medical officer |

| Department | Medical oncology |

| Brief summary of event that precipitated MD | |

| Patient is an elderly male who was revealed to have metastatic lung disease after initial presentation for shortness of breath. He actively seeks to know the diagnosis, but the family is not keen for the patient to know for fear of ‘losing the will to fight’. The team is currently withholding the diagnosis from the patient. | |

| Key factors in event that were at odds with personal values, beliefs or practices | |

| Factors | At odds with (in order of importance) |

| 1. Withholding of diagnosis from the patient | 1. Respect for patient’s autonomy |

| 2. Professional code of conduct by the hospital which directs us to disclose the diagnosis to the patient | |

| 3. Personal experiences with a serious illness in the past, when I had valued knowing the diagnosis to be more mentally prepared for the future. | |

RToP-MD, Ring Theory of Personhood-Moral Distress.

Figure 4.

Framework to understand MD. MD, moral distress.

There are two aspects to the RToP-MD reflective tool. The first considers demographical information and the reporting of physicians’ awareness of the key issues. An example is highlighted in table 2.

The second aspect of the tool is the data collected during the interview with the trained and trusted senior clinician. This qualitative aspect of the tool focuses on the physicians personal and situational constructs through the employ of the RToP.

The data collected represented by figure 4 focuses on three domains or rings acknowledging MD as a highly individualised sociocultural construct. The outer ring represents information on the macroenvironment. This includes the practical, ethical, legal, clinical, sociocultural and professional factors that influence thinking, decision making, practice and the conduct of the physician.

Elements within the macroenvironment also influences the mesoenvironment which is the middle ring. The mesoenvironment concerns the influence of the various stakeholders, and the organisation where MD occurred. This ring also concerns itself with the individual and the contextual factors.

The innermost ring or the microenvironment is influenced and influences the two outer rings. The microenvironment considers the physician’s narratives including their previous experiences,37 demographics, training, skills, personality, attitudes, resilience, current coping, and the values, beliefs,39 and principles10 62 within each of the 4 rings of the RToP.38 This ring also considers conflicts between and within the rings of the physician’s RToP. Here, the interview process will also seek to determine the relative weight afforded to each of the competing principles by the physician.

We believe that the findings of the RToP-MD tool203 will help direct a holistic, appropriate, accessible, personalised, longitudinal and timely support to physicians from members of a multidisciplinary mentoring,204 supervision205 and or coaching team which would also include a psychologist and or counsellor.206

The proposed framework for a RToP-MD tool also serves to highlight the shortfalls of the current management of MD (online supplemental materials D and E) that tends to be singular, short term and impersonal when what is required is a holistic, appropriate, accessible, personalised, longitudinal and timely approach to overcome MD.

bmjopen-2022-064029supp004.pdf (128.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064029supp005.pdf (80.9KB, pdf)

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. Despite vetting and evaluation of the search process by the expert team, the inclusion of only English language articles and the exclusion of grey literature precipitates a risk of failing to capture important articles.3 Concurrently focusing on publications in English focuses our attention on Western practice where distinct sociocultural, practice, education and healthcare considerations may limit the applicability of these findings in settings beyond the North American and European setting.

The purposeful selection of search terms and the employment of a wide range of databases broadened our approach to obtaining essential publications. However, the inclusion of articles that explicitly mention the term ‘MD’ and exclusion of non-healthcare settings, such as war, may limit our analysis of the conceptualisation of the phenomenon.

Although the thematic analysis was conducted by independent members of the team to improve the credibility and reliability of the data, inherent bias cannot be eliminated entirely.3 In addition, meetings were conducted at various time points of the coding and analysis process to enhance the consistency and validity of the data. However, articles that conflate the findings of MD in physicians and nurses still potentiates the risk of error in data extraction despite attempts to isolate the information.

Conclusion

In forwarding an evidence-based concept of MD among physicians and an accompanying framework, and RToP-MD tool, this SSR in SEBA reveals that this richer more complex concept of MD that extends beyond Jameton’s idea that suggests that other HCPs may have their distinct concepts of MD that ought to be studied separately. Even as these findings demand more attention to the timely, context-specific, culturally appropriate and personalised identification, assessment and support of MD among physicians, similar attention is owed other HCPs. In addition, with evidence acknowledging MD as a sociocultural construct future studies ought to be appropriately situated, longitudinal and holistic.

As we look forward to continuing our discourse on MD, we hope to share our findings into the further study, assessment and validation of this new definition, framework and tool with our research, education and clinical colleagues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna and A/Professor Cynthia Goh whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this review and Thondy and Maia Olivia whose lives continue to inspire us. The authors would also like to thank Alexia Sze Inn Lee for her help in searching and coding the articles and Nur Diana Abdul Rahman at the Division of Cancer Education, from National Cancer Centre, Singapore, for her contributions. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly enhanced this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: CWNQ, RRSO, RSMW, SWKC, AK-LC, GSS, AYTT, AP, NB, YAW, RCHC, CYLL, KWL, GHNT, REJL, NSYK, YTO, AMCC, MC, CL, XJZ, SYKO, EKO and LKRK were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript. LKRK accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants as it is a systematic scoping review. It analyses data from articles gathered from scholarly databases; no human participants were recruited in this study. Animals’ involvement: This study does not involve animals as it is a systematic scoping review. It analyses data from articles gathered from scholarly databases; no animal subjects were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Lamiani G, Dordoni P, Argentero P. Value congruence and depressive symptoms among critical care clinicians: the mediating role of moral distress. Stress Health 2018;34:135–42. 10.1002/smi.2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamrick A, Blackhall L. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in critical care units: collaboration, moral distress and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007;35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician’s personhood: a systematic scoping review. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2020;15:12. 10.1186/s13010-020-00096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossain F. Moral distress among healthcare providers and mistrust among patients during COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Dev World Bioeth 2021;21:187–92. 10.1111/dewb.12291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimmer A, Wilkinson E. What’s happening in covid-19 ICUs? An intensive care doctor answers some common questions. BMJ 2020;369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jameton A. Nursing practice: the ethical issues 1984.

- 7.Krishna LKR, Neo HY, Chia EWY, et al. The role of palliative medicine in ICU bed allocation in COVID-19: a joint position statement of the Singapore hospice Council and the chapter of palliative medicine physicians. Asian Bioeth Rev 2020;12:205–11. 10.1007/s41649-020-00128-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton S, Sarraf-Yazdi S, Rustandy F, et al. Medical students' preference for returning to the clinical setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Educ 2020;54:943–50. 10.1111/medu.14268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho S, Tan YY, Neo SHS, et al. COVID-19 — a review of the impact it has made on supportive and palliative care services within a tertiary hospital and cancer centre in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2020;49:489–95. 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2020224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiam M, Ho CY, Quah E, et al. Changing self-concept in the time of COVID-19: a close look at physician reflections on social media. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2022;17:1. 10.1186/s13010-021-00113-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim C, Zhou JX, Woong NL, et al. Addressing the needs of migrant workers in ICUs in Singapore. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2020;7:2382120520977190. 10.1177/2382120520977190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai HZ, Krishna LKR, Wong VHM. Feeding: what it means to patients and caregivers and how these views influence Singaporean Chinese caregivers' decisions to continue feeding at the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:166–71. 10.1177/1049909113480883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chong JA, Quah YL, Yang GM, et al. Patient and family involvement in decision making for management of cancer patients at a centre in Singapore. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:420–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foo WT, Zheng Y, Yang GM, et al. Factors considered in end-of-life decision-making of healthcare professionals. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:A45.2–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000196.131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marc Ho ZJ, Krishna LKR, Goh C, et al. The physician-patient relationship in treatment decision making at the end of life: a pilot study of cancer patients in a Southeast Asian Society. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:13–19. 10.1017/S1478951512000429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna L. Nasogastric feeding at the end of life: a virtue ethics approach. Nurs Ethics 2011;18:485–94. 10.1177/0969733011403557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishna L, Shirlynn AH. Reapplying the “argument of preferable alternative” within the context of physician-assisted suicide and palliative sedation. Asian Bioeth Rev 2015;7:62–80. 10.1353/asb.2015.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna LK. Decision-Making at the end of life: a Singaporean perspective. Asian Bioethics Review 2011;3:118–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radha Krishna LK, Krishna LK. Personhood within the context of sedation at the end of life in Singapore. Case Reports 2013;2013:bcr2013009264. 10.1136/bcr-2013-009264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishna LKR, Menon S, Kanesvaran R. Applying the welfare model to at-own-risk discharges. Nurs Ethics 2017;24:525–37. 10.1177/0969733015617340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishna LKR, Poulose JV, Goh C. Artificial hydration at the end of life in an oncology ward in Singapore. Indian J Palliat Care 2010;16:168. 10.4103/0973-1075.73668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishna LKR, Watkinson DS, Beng NL. Limits to relational autonomy—the Singaporean experience. Nurs Ethics 2015;22:331–40. 10.1177/0969733014533239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radha Krishna LK, Poulose JV, Tan BSA, et al. Opioid use amongst cancer patients at the end of life. Ann Acad Med Singap 2010;39:790–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lalit Krishna M. The position of the family of palliative care patients within the decision-making process at the end of life in Singapore. Ethic Med 2011;27:183. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radha Krishna LK, Poulose VJ, Goh C. The use of midazolam and haloperidol in cancer patients at the end of life. Singapore Med J 2012;53:62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radha Krishna LK. Accounting for personhood in palliative sedation: the ring theory of personhood. Med Humanit 2014;40:17–21. 10.1136/medhum-2013-010368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radha Krishna LK, Murugam V, Quah DSC. The practice of terminal discharge: is it euthanasia by stealth? Nurs Ethics 2018;25:1030–40. 10.1177/0969733016687155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishna LKR, Tay JT, Watkinson DS, et al. Advancing a Welfare-Based model in medical decision. Asian Bioeth Rev 2015;7:306–20. 10.1353/asb.2015.0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong EK, Krishna LK, PSH N. The sociocultural and ethical issues behind the decision for artificial hydration in a young palliative patient with recurrent intestinal obstruction. Ethic Med : Int J Bioeth 2015;31:39. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Huang Y, Radha Krishna L, et al. Role of the nasogastric tube and Lingzhi (Ganoderma lucidum) in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:794–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soh TLGB, Krishna LKR, Sim SW, et al. Distancing sedation in end-of-life care from physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. Singapore Med J 2016;57:220–7. 10.11622/smedj.2016086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prentice TM, Gillam L. Can the ethical best practice of shared decision-making lead to moral distress? J Bioeth Inq 2018;15:259–68. 10.1007/s11673-018-9847-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varcoe C, Pauly B, Webster G, et al. Moral distress: tensions as springboards for action. HEC Forum 2012;24:51–62. 10.1007/s10730-012-9180-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lievrouw A, Vanheule S, Deveugele M, et al. Coping with moral distress in oncology practice: nurse and physician strategies. Oncol Nurs Forum 2016;43:505–12. 10.1188/16.ONF.505-512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deshpande AD, Sanders Thompson VL, Vaughn KP, et al. The use of sociocultural constructs in cancer screening research among African Americans. Cancer Control 2009;16:256–65. 10.1177/107327480901600308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radha Krishna LK, Alsuwaigh R. Understanding the fluid nature of personhood - the ring theory of personhood. Bioethics 2015;29:171–81. 10.1111/bioe.12085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Lim YX, et al. A systematic scoping review on patients’ perceptions of dignity. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21:118. 10.1186/s12904-022-01004-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho CY, Kow CS, Chia CHJ, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:1–16. 10.1186/s12909-020-02411-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ong RSR, Wong RSM, Chee RCH, et al. A systematic scoping review moral distress amongst medical students. BMC Med Educ 2022;22:466. 10.1186/s12909-022-03515-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan NPX, Chia JL. Extending the ring theory of personhood to the care of dying patients in intensive care units. Asian Bioeth Rev 2021;14:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang H, Toh RQE, Chiang CLL, et al. Impact of dying neonates on doctors' and nurses' personhood: a systematic scoping review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:e59–74. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho CY, Lim N-A, Ong YT, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of senior nurses at the National cancer centre Singapore (NCCS): a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21:83. 10.1186/s12904-022-00974-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei SS, Krishna LKR. Respecting the wishes of incapacitated patients at the end of life. Ethics & Medicine 2016;32:15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radha Krishna LK, Jia Yu Lee R, Shin Wei Sim D, et al. Perceptions of quality-of-life advocates in a Southeast Asian Society. Divers Equal Health Care 2017;14. 10.21767/2049-5471.100095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loh AZH, Tan JSY, Jinxuan T, et al. Place of care at end of life: what factors are associated with patients' and their family members' preferences? Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:669–77. 10.1177/1049909115583045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishna L. Palliative care imperative: a framework for holistic and inclusive palliative care. Ethic Med 2013;29:41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radha Krishna LK, Murugam V, Quah DSC. The practice of terminal discharge: is it euthanasia by stealth? Nurs Ethics 2018;25:1030–40. 10.1177/0969733016687155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:1–17. 10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:1–10. 10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2020;7:2382120520957649 10.1177/2382120520957649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, et al. Impact of caring for terminally ill children on physicians: a systematic scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38:1049909120950301:396–418. 10.1177/1049909120950301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pring R. The ‘false dualism’ of educational research. J Philos Educat 2000;34:247–60. 10.1111/1467-9752.00171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. SAGE, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ford K. Taking a narrative turn: possibilities, challenges and potential outcomes. OnCUE J 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, et al. What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health 2016;3:172–215. 10.3934/publichealth.2016.1.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kamal NHA, LHE T, Wong RSM. Enhancing education in palliative medicine: the role of systematic scoping reviews. Palliat Med Care 2020;7:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW. A systematic scoping review of narrative reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care 2020;7:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW. A systematic scoping review of systematic reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care 2020;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong DZ, Lim AJS, Tan R, et al. A systematic scoping review on Portfolios of medical educators. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2021;8:23821205211000356 10.1177/23821205211000356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tay KT, Ng S, Hee JM, et al. Assessing professionalism in medicine–a scoping review of assessment tools from 1990 to 2018. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2020;7:2382120520955159 10.1177/2382120520955159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tay KT, Tan XH, LHE T. A systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of interprofessional mentoring in medicine from 2000 to 2019. J Interprof Care 2020:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou YC, Tan SR, Tan CGH, et al. A systematic scoping review of approaches to teaching and assessing empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ 2021;21:1–15. 10.1186/s12909-021-02697-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, McInerney P. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osama T, Brindley D, Majeed A, et al. Teaching the relationship between health and climate change: a systematic scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020330. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. springer Publishing Company, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:72–8. 10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.YX N, ZYK K, Yap HW, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. (1932-6203 (electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Chua WJ, Cheong CWS, Lee FQH, et al. Structuring mentoring in medicine and surgery. A systematic scoping review of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2019. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2020;40:158–68. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232511. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med 2013;11:20. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme version 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Voloch K-A, Judd N, Sakamoto K. An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho'ola Post-Baccalaureate students at the University of Hawai'i John A. Burns School of Medicine. Hawaii Med J 2007;66:102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193001. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neal JW, Neal ZP, Lawlor JA, et al. What makes research useful for public school educators?. Adm Policy Ment Health 2018;45:432–46. 10.1007/s10488-017-0834-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wagner-Menghin M, de Bruin A, van Merriënboer JJG. Monitoring communication with patients: analyzing judgments of satisfaction (JOS). Adv in Health Sci Educ 2016;21:523–40. 10.1007/s10459-015-9642-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Elo S, Kyngäs H, HJJoan K. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mayring PJActqr . Qualitative content analysis 2004;1:159–76. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Humble ÁMJIJoQM . Technique triangulation for validation in directed content analysis 2009;8:34–51. [Google Scholar]

- 83.France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:35. 10.1186/s12874-019-0670-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Larson CP, Dryden-Palmer KD, Gibbons C, et al. Moral distress in PICU and neonatal ICU practitioners: a cross-sectional evaluation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:e318–26. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Janvier A, Nadeau S, Deschênes M, et al. Moral distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: caregiver's experience. J Perinatol 2007;27:203–8. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, et al. Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: an interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:627–35. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Neumann JL, Mau L-W, Virani S, et al. Burnout, moral distress, work-life balance, and career satisfaction among hematopoietic cell transplantation professionals. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018;24:849–60. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abbasi M, Nejadsarvari N, Kiani M, et al. Moral distress in physicians practicing in hospitals affiliated to medical sciences universities. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014;16:e18797. 10.5812/ircmj.18797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nejadsarvari N, Abbasi M, Borhani F, et al. Relationship of moral sensitivity and distress among physicians. Trauma Mon 2015;20:e26075. 10.5812/traumamon.26075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Førde R, Aasland OG. Moral distress among Norwegian doctors. J Med Ethics 2008;34:521–5. 10.1136/jme.2007.021246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cullati S, Cheval B, Schmidt RE, et al. Self-rated health and sick leave among nurses and physicians: the role of regret and coping strategies in difficult Care-Related situations. Front Psychol 2017;8:623. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dzeng E. Navigating the liminal state between life and death: clinician moral distress and uncertainty regarding new life-sustaining technologies. Am J Bioeth 2017;17:22–5. 10.1080/15265161.2016.1265172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanderson C, Sheahan L, Kochovska S, et al. Re-defining moral distress: a systematic review and critical re-appraisal of the argument-based bioethics literature. Clin Ethics 2019;14:195–210. 10.1177/1477750919886088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eves MM, Danziger PD, Farrell RM, et al. Conflicting values: a case study in patient choice and caregiver perspectives. Narrat Inq Bioeth 2015;5:167–78. 10.1353/nib.2015.0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Beck J, Randall CL, Bassett HK, et al. Moral distress in pediatric residents and pediatric hospitalists: sources and association with burnout. Acad Pediatr 2020;20:1198–205. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hancock J, Witter T, Comber S, et al. Understanding burnout and moral distress to build resilience: a qualitative study of an interprofessional intensive care unit team. Can J Anaesth 2020;67:1541–8. 10.1007/s12630-020-01789-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, et al. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2019;10:113–24. 10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, et al. Moral distress among healthcare professionals: report of an institution-wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015;47:117–25. 10.1111/jnu.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vincent H, Jones DJ, Engebretson J. Moral distress perspectives among interprofessional intensive care unit team members. Nurs Ethics 2020;27:1450–60. 10.1177/0969733020916747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sajjadi S, Norena M, Wong H, et al. Moral distress and burnout in internal medicine residents. Can Med Educ J 2017;8:e36–43. 10.36834/cmej.36639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rushton CH, Kaszniak AW, Halifax JS. A framework for understanding moral distress among palliative care clinicians. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1074–9. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Neo HY, Khoo HS, Hum A. Preliminary data from studying moral distress amongst trainees in a residency programme. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2016;45:S42. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carse A, Rushton CH. Harnessing the promise of moral distress: a call for re-orientation. J Clin Ethics 2017;28:15–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bader CS, Herschkopf MD. Trainee moral distress in capacity consultations for end-of-life care. Psychosomatics 2019;60:508–12. 10.1016/j.psym.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Green MM, Wicclair MR, Wocial LD, et al. Moral distress in rehabilitation. Pm R 2017;9:720–6. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pergert P, Bartholdson C, Blomgren K, et al. Moral distress in paediatric oncology: contributing factors and group differences. Nurs Ethics 2019;26:2351–63. 10.1177/0969733018809806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jones GAL, Colville GA, Ramnarayan P, et al. Psychological impact of working in paediatric intensive care. A UK-wide prevalence study. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:470–5. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Prentice TM, Gillam L, Janvier A, et al. How should neonatal clinicians act in the presence of moral distress? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2020;105:348–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Green M, Carter B, Lasky A. Difficult discharge in pediatric rehabilitation medicine causing moral distress. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil 2016;15:42–51. 10.1080/1536710X.2016.1124253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zimmermann CJ, Taylor LJ, Tucholka JL, et al. The association between factors promoting Nonbeneficial surgery and moral distress: a national survey of surgeons. Ann Surg 2022;276:94–100. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dodek PM, Cheung EO, Burns KE. Moral distress and other wellness measures in Canadian critical care physicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brown-Saltzman K. The gift of voice. Narrat Inq Bioeth 2013;3:139–45. 10.1353/nib.2013.0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Howe EG. Fourteen important concepts regarding moral distress. J Clin Ethics 2017;28:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Trotochaud K, Coleman JR, Krawiecki N, et al. Moral distress in pediatric healthcare providers. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:908–14. 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.de Boer JC, van Rosmalen J, Bakker AB, et al. Appropriateness of care and moral distress among neonatal intensive care unit staff: repeated measurements. Nurs Crit Care 2016;21:e19–27. 10.1111/nicc.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lamiani G, Dordoni P, Vegni E, et al. Caring for critically ill patients: clinicians' empathy promotes job satisfaction and does not predict moral distress. Front Psychol 2019;10:2902. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Henrich NJ, Dodek PM, Alden L, et al. Causes of moral distress in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. J Crit Care 2016;35:57–62. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Henrich NJ, Dodek PM, Gladstone E, et al. Consequences of moral distress in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Am J Crit Care 2017;26:e48–57. 10.4037/ajcc2017786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lamiani G, Setti I, Barlascini L, et al. Measuring moral distress among critical care clinicians: validation and psychometric properties of the Italian moral distress Scale-Revised. Crit Care Med 2017;45:430–7. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Johnson-Coyle L, Opgenorth D, Bellows M, et al. Moral distress and burnout among cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit healthcare professionals: a prospective cross-sectional survey. Can J Crit Care Nurs 2016;27:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hamric AB. Moral distress and nurse-physician relationships. Virtual Mentor 2010;12:6–11. 10.1001/virtualmentor.2010.12.1.ccas1-1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dodek P, Norena M, Ayas N, et al. Moral distress in intensive care unit personnel is not consistently associated with adverse medication events and other adverse events. J Crit Care 2019;53:258–63. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dodek PM, Wong H, Norena M, et al. Moral distress in intensive care unit professionals is associated with profession, age, and years of experience. J Crit Care 2016;31:178–82. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dodek PM, Norena M, Ayas N, et al. Moral distress is associated with general workplace distress in intensive care unit personnel. J Crit Care 2019;50:122–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fujii T, Katayama S, Nashiki H. Moral distress, burnout, and coping among intensive care professionals in Japanese ICUs. Intens Care Med Experiment 2018;6. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wocial L, Ackerman V, Leland B, et al. Pediatric ethics and communication excellence (peace) rounds: decreasing moral distress and patient length of stay in the PICU. HEC Forum 2017;29:75–91. 10.1007/s10730-016-9313-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Moskop JC, Geiderman JM, Marshall KD, et al. Another look at the persistent moral problem of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2019;74:357–64. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dzeng E, Colaianni A, Roland M, et al. Moral distress amongst American physician trainees regarding futile treatments at the end of life: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:93–9. 10.1007/s11606-015-3505-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wocial LD, Slaven JE, Montz K, et al. Factors associated with physician moral distress caring for hospitalized elderly patients needing a surrogate decision-maker: a prospective study. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:1–8. 10.1007/s11606-020-05652-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rosenwohl-Mack S, Dohan D, Matthews T, et al. Understanding experiences of moral distress in end-of-life care among US and UK physician trainees: a comparative qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36:1890–7. 10.1007/s11606-020-06314-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.McLaughlin SE, Fisher H, Farrell C. Moral distress in internal medicine residents. J GenInt Med 2019;34:S288. [Google Scholar]

- 133.McLaughlin SE, Fisher H, Lawrence K. Moral distress among physician trainees: contexts, conflicts, and coping mechanisms in the training environment. J Gen Int Med 2020;35:S201. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hlubocky FJ, Taylor LP, Marron JM, et al. A call to action: ethics committee roundtable recommendations for addressing burnout and moral distress in oncology. JCO Oncol Pract 2020;16:191–9. 10.1200/JOP.19.00806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.DeBoer RJ, Fadelu TA, Shulman LN, et al. Applying lessons learned from low-resource settings to prioritize cancer care in a pandemic. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1429–33. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Flood D, Wilcox K, Ferro AA, et al. Challenges in the provision of kidney care at the largest public nephrology center in Guatemala: a qualitative study with health professionals. BMC Nephrol 2020;21:71. 10.1186/s12882-020-01732-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ducharlet K, Philip J, Gock H, et al. Moral distress in nephrology: perceived barriers to ethical clinical care. Am J Kidney Dis 2020;76:248–54. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mullin J, Bogetz J. Point: moral distress can indicate inappropriate care at end-of-life. Psychooncology 2018;27:1490–2. 10.1002/pon.4713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Weissman DE. Moral distress in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2009;12:865–6. 10.1089/jpm.2009.9956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Close E, White BP, Willmott L, et al. Doctors' perceptions of how resource limitations relate to futility in end-of-life decision making: a qualitative analysis. J Med Ethics 2019;45:373–9. 10.1136/medethics-2018-105199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.St Ledger U, McAuley DF, Reid J. Doctors' experiences of moral distress in end-of-life care decisions in the intensive care unit. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2017;195. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Deep KS, Wilson JF, Howard R. Thanks for letting me vent": Moral distress in physicians. J Gen Int Med 2008;23:232. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Cervantes L, Richardson S, Raghavan R, et al. Clinicians' perspectives on providing Emergency-Only hemodialysis to Undocumented immigrants: a qualitative study. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:78–86. 10.7326/M18-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Oliver D. David Oliver: moral distress in hospital doctors. BMJ 2018;360:k1333. 10.1136/bmj.k1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Dzeng E, Weiss R, Vergnaud S. Physician trainees' experiences of moral distress regarding potentially futile treatments at the end of life in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. J Gen Int Med 2017;32:S274–5. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Dunham AM, Rieder TN, Humbyrd CJ. A bioethical perspective for navigating moral dilemmas amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2020;28:471–6. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Salehi PP, Jacobs D, Suhail-Sindhu T, et al. Consequences of medical hierarchy on medical students, residents, and medical education in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;163:906–14. 10.1177/0194599820926105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tigard DW. Rethinking moral distress: conceptual demands for a troubling phenomenon affecting health care professionals. Med Health Care Philos 2018;21:479–88. 10.1007/s11019-017-9819-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bruce CR, Miller SM, Zimmerman JL. A qualitative study exploring moral distress in the ICU team: the importance of unit functionality and intrateam dynamics. Crit Care Med 2015;43:823–31. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Berger JT, Hamric AB, Epstein E. Self-Inflicted moral distress: opportunity for a fuller exercise of professionalism. J Clin Ethics 2019;30:314–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol 2017;22:51–67. 10.1177/1359105315595120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Martin LP. An ethics refresher for doctors in moral distress: theory and practice. Br J Hosp Med 2019;80:C39–41. 10.12968/hmed.2019.80.3.C39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Aultman J, Wurzel R. Recognizing and alleviating moral distress among obstetrics and gynecology residents. J Grad Med Educ 2014;6:457–62. 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00256.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Thomas TA, Thammasitboon S, Balmer DF, et al. A qualitative study exploring moral distress among pediatric resuscitation team clinicians: challenges to professional integrity. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17:e303–8. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Redmann AJ, Smith M, Benscoter D, et al. Moral distress in pediatric otolaryngology: a pilot study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2020;136:110138. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Johnston K, Holm S, Aquino V. Assessing moral distress in trainees on a pediatric hematology-oncology rotation. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 2020;67. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Grady C. Surgical medicine: imperfect and extraordinary. Narrat Inq Bioeth 2015;5:37–43. 10.1353/nib.2015.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Mills M, Cortezzo DE. Moral distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: what is it, why it happens, and how we can address it. Front Pediatr 2020;8:581. 10.3389/fped.2020.00581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Colville GA, Dawson D, Rabinthiran S, et al. A survey of moral distress in staff working in intensive care in the UK. J Intensive Care Soc 2019;20:196–203. 10.1177/1751143718787753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lamiani G, Ciconali M, Argentero P, et al. Clinicians' moral distress and family satisfaction in the intensive care unit. J Health Psychol 2020;25:1894–904. 10.1177/1359105318781935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Prim Res 2012;3:1–9. 10.1080/21507716.2011.65233726137345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Epstein EG. End-of-life experiences of nurses and physicians in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinatol 2008;28:771–8. 10.1038/jp.2008.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Traudt T, Liaschenko J. What should physicians do when they disagree, clinically and ethically, with a surrogate's wishes? AMA J Ethics 2017;19:558–63. 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.ecas4-1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Jacobs B, Manfredi RA. Moral distress during COVID-19: residents in training are at high risk. AEM Educ Train 2020;4:447–9. 10.1002/aet2.10488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Morris SE, Tarquini SJ, Yusufov M. Burnout in psychosocial oncology clinicians: a systematic review. Palliative Supportive Care 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Miljeteig I, Defaye F, Desalegn D, et al. Clinical ethics dilemmas in a low-income setting - a national survey among physicians in Ethiopia. BMC Med Ethics 2019;20:63. 10.1186/s12910-019-0402-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, et al. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:701–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Davidson JE, Agan DL, Chakedis S, et al. Workplace blame and related concepts: an analysis of three case studies. Chest 2015;148:543–9. 10.1378/chest.15-0332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Dombrecht L, Cohen J, Cools F, et al. Psychological support in end-of-life decision-making in neonatal intensive care units: full population survey among neonatologists and neonatal nurses. Palliat Med 2020;34:430–4. 10.1177/0269216319888986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Dodek PM, Norena M, Ayas N. The relationship between moral distress and adverse safety events in intensive care units. Am J Resp Crit Med 2013;187. [Google Scholar]

- 171.Alwadaei S, Almoosawi B, Humaidan H, et al. Waiting for a miracle or best medical practice? End-of-life medical ethical dilemmas in Bahrain. J Med Ethics 2019;45:367–72. 10.1136/medethics-2018-105297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Daniel M. Bedside resource stewardship in disasters: a provider's dilemma practicing in an ethical gap. J Clin Ethics 2012;23:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Litleskare LA, Strander MT, Førde R, et al. Refusals to perform ritual circumcision: a qualitative study of doctors' professional and ethical Reasoning. BMC Med Ethics 2020;21:5. 10.1186/s12910-020-0444-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Aguilera D, Castellino R, Kim S. Moral distress in pediatric hematology/oncology physicians. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 2014;61:S32. [Google Scholar]

- 175.Grauerholz KR, Fredenburg M, Jones PT, et al. Fostering vicarious resilience for perinatal palliative care professionals. Front Pediatr 2020;8:572933. 10.3389/fped.2020.572933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Siddiqui S, Alyssa CW-L, Soh K. Having it all-Burnout and moral distress in working female physicians in a developed Asian country, 2017. [Google Scholar]