Abstract

Brazil is an emerging country with continental proportions, being one of the largest in the world. As big as its territory, are the complexities and singularities within it. Brazilian thoracic surgery reflects the picture of this unique giant, with all its virtues and problems. This peculiar framework of thoracic surgery in Brazil unfolds that the surgeons are usually well trained and can perform this specialty with technical and scientific excellence, making the country to play a true major role in Latin American thoracic surgery. Nevertheless, the chronic social imbalance present in every aspect of the Brazilian daily life hampers this ultra-specialized workforce to be equally and universally available for every citizen, in every corner of the country. Lung transplantation and minimally invasive approaches (including robotics) are performed by many surgeons with good results, comparable to those observed in high-income countries from North America, Europe and Asia. However, these procedures are still performed more often in centers of academic excellence, located at the main cities of the country, which also reflects an unequal access to these approaches within the Brazilian territory. The aim of this paper is to present a broad overview of the practice of general thoracic surgery in Brazil, as well as its main idiosyncrasies.

Keywords: Thoracic surgery, Brazil, demographics, Brazilian society, medical residency program, healthcare system, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), robotic surgery, lung cancer, lung transplantation

Introduction

Corresponding to the fifth vast country worldwide, counting with around 8,510.345 km² extension and playing one of the most influential lead-positions in Latin America, Brazil has its own space in thoracic surgery (1). Starting around the 30’s and 40’s of the 20th Century, Brazilian thoracic surgery emerged initially as a tool to treat conditions mainly related to pulmonary tuberculosis, in an era when medical antibiotic therapies were not available yet. In those early years, the specialty was closely attached to general surgery and cardiac surgery, and has markedly evolved with the inauguration of Hospital das Clínicas de São Paulo in 1944 under the coordination of Prof. Dr. Alípio Corrêa Neto (2). Since then, it has grown continuously from the classical open thoracotomies to the field of minimally invasive surgery and complex procedures, as well as progressively splitting from general and cardiac surgery to finally become recognized as an autonomous specialty.

Given the historical high prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in Brazil, since its first steps, the Brazilian thoracic surgery school has been—and still is—recognized by its large experience in the treatment of thoracic infectious and inflammatory diseases, as well as its sequelae.

Ultimately, the development of Brazilian thoracic surgery is closely related to the growth and maturation of the specialty itself as a whole, particularly in the last three to four decades. An important reflex of this evolution was the foundation of the Brazilian Society of Thoracic Surgery [Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Torácica (SBCT)], which was originally born as a department of the Brazilian Society of Pneumology and Tisiology in the late 70’s, ending up to be finally established as an independent society in 1997. Since then, the SBCT has evolved to become the biggest Society dedicated to general thoracic surgery in Latin America, counting on more than 750 active members nowadays and placing Brazil as a regional protagonist in the specialty within the continent.

Due to its innate anatomical characteristics (i.e., rigid thoracic wall and trend for the lung to naturally collapse when the pleural cavity is opened) and to the significant pain involved in open thoracotomies, general thoracic surgery is certainly among the surgical specialties that has collected the most solid benefits from the technological and technical improvements which have led the surgical practice to reach the current standards of modern minimally invasive surgery.

In this article, the authors bring to light a wide framework of the general thoracic surgery practice in Brazil, as well as focusing on its main singularities.

Demographics in the specialty

Despite its continental dimensions, Brazil accounts for approximately 1,106 active thoracic surgeons in 2020, corresponding to only 0.3% of all medical specialists (3).

Even though there is some inaccuracy in these numbers related to the type of specialty national registration and specific specialty societies accreditation, compared with its estimated population of 213.7 million in 2021, the shortage of access to these professionals (around 0.52 thoracic surgeon per 100,000 habitants) becomes evident (4,5). Hence, in several small and peripheral locations, occasionally it happens that some procedures in thoracic surgery are performed by non-specialists, mostly general surgeons.

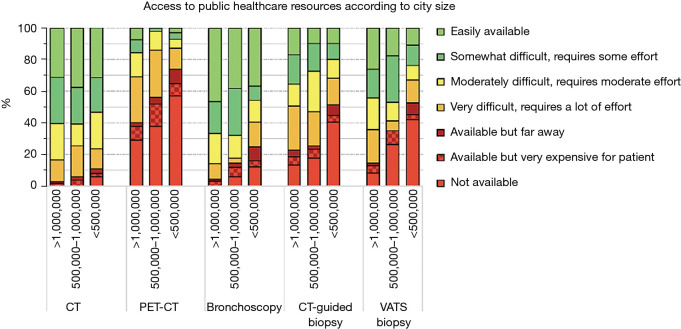

Interestingly, despite the vastness of the country and scarcity of specialists, most of these professionals mainly concentrate their practice in only 2 of 5 Brazilian macro regions: South and Southeast, which are represented by the states accounting for the highest economic incomes in the whole country (4). This disparity is also reproduced within the frame of these macro regions, their composing states and their respective main cities. The most densely populated cities in Brazil are located exactly in these more developed states and this preference of thoracic surgeons to deploy their practice in bigger centers may be related, at least in part, to the fact that—within the public healthcare system context—the easiness of access to medical infrastructure and more sophisticated resources tends to be directly proportional to the size of the cities, as clearly shown in Figure 1 (6).

Figure 1.

Degree of access to various exams in the public healthcare system by city size (population). Extracted after copyright holder permission from Tsukazan et al. (6). CT, computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

This phenomenon above described is not only observed in thoracic surgery medical assistance itself, but also in medical research. The major part of Brazilian scientific production in thoracic surgery comes from the same regions, states and cities that house the majority of thoracic surgeons in Brazil. This occurrence is not solely related to the number of professionals but is also highly dependent on the fact that the most prestigious and active academic institutions are located in these very same places.

Regarding the gender distribution in the country, according to updated data from the SBCT, its associates are mainly represented by male physicians (approximately 86%), notwithstanding the escalating numbers of women graduating in medicine in Brazil. Considering the most recent trends observed around the western world, this enormous difference is likely to change gradually in the future, perhaps towards a relative balance.

Formation of the future thoracic surgeon

Different from other countries, the professional qualification in general thoracic surgery in Brazil is completely separated from cardiovascular surgery: the former begins with 2 to 3 years of general surgery training followed by at least 2 more years of focused thoracic surgery residency program, and the latter is represented by five years of focused cardiovascular training, without previous general surgery experience (since 2020 curricular program update) (4,7,8). In Brazil, after the 2 first obligatory years in thoracic surgery, the specialization in the thoracic surgery can be extended for a third or even a fourth year in some institutions, focusing in some specific sub-areas: minimally invasive surgery, interventional bronchoscopy or lung transplantation, for example.

Overall, according to Tedde et al. in 2015 (4), the formation of a general thoracic surgeon in Brazil corresponds to 4.3±0.9 years, less than the mean ~8.5 years in cardiothoracic surgery combined training of other American countries.

There are 35 thoracic surgery residency training programs accredited by the National Medical Residency Committee [Comissão Nacional de Residência Médica (CNRM)], with a mean of 50 resident-positions per year, including some for international surgeons generally from other Latin American countries.

In general, the competencies for a thoracic surgeon in Brazil after completing the medical residency include the ability to diagnose and treat all the thoracic surgical pathologies. It embraces performing a wide range of procedures, from endoscopic to surgical interventions, in open or minimally invasive platforms. The main field of action of thoracic surgeon in Brazil involve lung, airway, chest wall, mediastinal and diaphragmatic diseases that require endoscopic and/or surgical approaches to be diagnosed and treated, as well as thoracic trauma and its complications.

It is worthwhile to mention that esophageal surgical pathologies are also included within the basic formation of thoracic surgeons in Brazil, although this area is often a field of action for general surgeons who dedicate themselves to upper gastrointestinal tract surgery. So, there are several Brazilian thoracic surgeons who perform esophageal surgery, while many others just don’t.

Another “grey zone” in which procedures are also executed by other medical specialists is flexible diagnostic bronchoscopy/endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) (also performed by some clinical pulmonologists), while interventional bronchoscopy (flexible and rigid) is usually done mostly by thoracic surgeons.

As mentioned before, cardiac surgery is considered a different specialty in Brazil, with its proper medical residency program, detached from thoracic surgery.

Healthcare system and general practice

The practice of many surgeons includes two different types of healthcare system: a public one, Unified National Healthcare System [Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS)], which provides full assistance to any Brazilian, and even foreigners, guaranteed by the Brazilian Constitution; and a supplementary/private healthcare system, including a variety of insurance modalities.

In general, the coverage of the public system encompasses nearly three-fourths of the overall population (4). Even though supporting the largest portion of the Brazilian population, the public sector generally disposes of less diagnostic and therapeutic resources, posing actual challenges to medical professionals and making the quality of care very heterogeneous across the country and even within the same city.

This heterogeneousness impacts also the types of more common diseases which the thoracic surgeon faces in his general practice: inflammatory/infectious diseases (empyema, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis active/sequelae, lung abscesses), thoracic trauma, and tracheal benign diseases (mainly subglottic/tracheal stenosis) are more often managed in the setting of the public system than in the private one, possibly due to epidemiological aspects, social vulnerability, early access and quality of care.

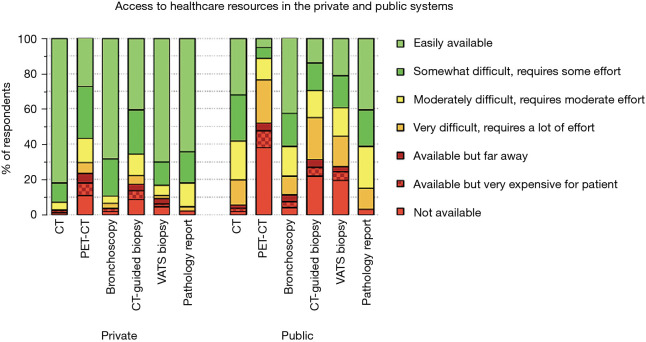

Oncological diseases are treated in both sectors, however, there are obvious disparities between the two systems. Taking the management of lung nodules as an example of this situation, important diagnostic and staging procedures according to the most updated guidelines worldwide [such as computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, image-guided or bronchoscopy/EBUS biopsies] are not universally available and are particularly more difficult to access in the public health system, leading to an increased risk of late diagnosis of malignant neoplasms in the population that depends exclusively on the public health system. This concern is usually not an issue on the private sector (6), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Degree of access to exams according to patient insurance (public healthcare system versus private healthcare system). Extracted after copyright holder permission from Tsukazan et al. (6). CT, computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Newer technologies such as EBUS, robotic surgery platforms, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) are available in the country in both systems even if in different proportions, and sometimes requiring judicialization to its access.

To our knowledge, in Brazil there are no centers exclusively dedicated to the practice of general thoracic surgery (regionalized or even in major Brazilian cities). The specialty is usually performed in general hospitals, predominantly in those that provide high-complexity medical services.

Recent surgical development in specific areas: minimally invasive approaches and lung transplantation

The first steps of minimally invasive thoracic surgery in Brazil dates to late 80’s and early 90’s of the last century. At that time, the video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) procedures were almost exclusively done for diagnostic and/or simple therapeutic purposes. The first decade of the current century marks the beginning of the era of “modern” VATS in Brazil, when more complex procedures finally became part of the armamentarium of minimally invasive thoracic surgeons. Initially, the adoption of VATS for anatomic lung resections has been slower and took place quite later than in other parts of the world (centers of excellence in USA, Europe and Asia). The reasons for that may be mostly explained by two factors: (I) cost-related issues regarding the devices needed to perform these resections; (II) lack of standardization regarding the surgical technique for these procedures (9). During the last two decades, these issues have been progressively overlapped at least in part, and the minimally invasive approach for these resections is being increasingly adopted in Brazil, as well as in other emerging countries.

In 2016, for the first time, a multi-centric study was conducted in Brazil to confirm the applicability and safety of the technique within the country (10). Terra et al. reviewed and analyzed the 649 anatomic pulmonary resections performed by video-assisted thoracoscopy in Brazil, including conversion rates (4.6%) intraoperative complications (4.3%), postoperative complications (19.1%), 30-day mortality (2.0%) and median hospital stay (4 days). The published results showed that the Brazilian experience at that time was reasonably consistent and comparable (and consequently, not inferior) to those observed in other international large databases from USA and Europe.

Since then, the database of the SBCT has been officially established in 2015 and the numbers are increasing year after year. This national registry is a data collection system controlled by the SBCT focused mainly on lung resections, where centers and surgeons are free to choose to participate and share their surgical data, as well as having them analyzed and registered every year.

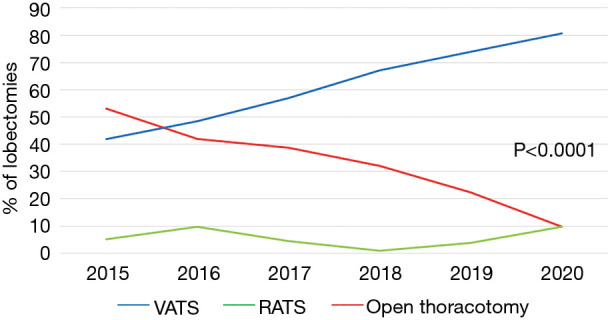

Recent data from the national database of SBCT (11) shows that the percentage of minimally invasive lobectomies for lung cancer from 2015 to 2020 is consistently increasing at the institutions that contribute to this database.

In 2015, roughly, 53% of lobectomies for lung cancer performed at the collaborating institutions which take part of the SBCT national database were done by open thoracotomy, whereas 42% were by VATS and only 5% by robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS). These numbers have been changing dramatically over the following years and in 2020, around 80% of the lobectomies were carried out by VATS and 10% by RATS, while only 10% of the lobectomies at these specific institutions were performed by open thoracotomy. Figure 3 clearly demonstrates this evolution from 2015 to 2020.

Figure 3.

Percentage of each surgical approach for lobectomies performed for lung cancer at the collaborating institutions that take part of the SBCT national database from 2015 to 2020 (11). Extracted after copyright holder permission from Tzukazan et al. (11). VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery; RATS, robotic-assisted thoracic surgery.

It is important to stress that, although the information provided by the database is a critical tool to analyze how the surgical approaches for lung resections are evolving in Brazil over the years, data must be interpreted with attention, since it may not reflect an exact overview of the whole broad Brazilian reality, considering that the participation in the database is non-compulsory and the participating institutions are essentially centers of academic excellence located in Brazilian major cities. Nowadays, the SBCT national database counts on 17 collaborating institutions and 9,167 lung resections were registered from 2015 to 2020 (11).

Indeed, the number of minimally invasive anatomic lung resections performed per year within the whole Brazilian territory, as well as in many other developing countries, still may be smaller than it actually could be and the fact that not every surgeon is in position to perform more advanced procedures by VATS is undeniable. However, time is slowly showing us that there is a trend to change this situation over the years to come, due to the gradually easier access to medical devices needed for these operations and the ongoing greater technical proficiency by thoracic surgeons in these countries.

All the challenges and difficulties faced in Brazil to establish VATS as an accessible and pervasive platform in the country in a recent past have been (and are still being) also confronted by RATS even more recently. This platform has been introduced in Brazil in the last fifteen years and is being progressively more used by a growing number of surgeons all over the country. First at the biggest centers, the robotic platforms are increasingly becoming present in more and more cities and hospitals every year. Today, there are 85 robotic systems active in Brazil and again, their distribution is quite unequal within the national territory, with most of them being located at the biggest cities of the country.

Anyway, it can be said that, thanks to these centers where RATS is more accessible, national experience in thoracic RATS is gradually rising with good results, not only for oncologic resections (12,13) but also for benign diseases as well (14). This cumulative experience allows the possibility of a wide dissemination of the knowledge by the creation of certified national robotic training programs (15,16), which is the scenario we are now currently experiencing in Brazil. This is proving to be important not only for Brazilian thoracic surgeons, but also for colleagues from other Latin American countries, who are now being able to become familiar with this new technology more easily than it would be if they had to go to North America or Europe to get trained. The lack of publications still precludes a wider look over the results of RATS in Brazil, as well in Latin America (17).

Regarding lung transplantation, it is important to say that Brazil has the largest transplantation public system in the world, with more than 95% of procedures funded by the public health system (SUS), being the second country in the world in absolute transplantation numbers (18). To date, there are eight active lung transplantation programs in Brazil, four located in the southeast states (three in São Paulo and one in Rio de Janeiro), three in south states (two in Rio Grande do Sul and one in Paraná), and one in the northeast (in the state of Ceará). Beginning in 1989 as the first lung transplantation in Latin America with the pioneering of Prof. Dr. Jose Jesus Camargo in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, the total cumulative number of lung transplants performed accounts for more than 1,300 procedures according to the 2021’s Brazilian Organ Transplantation Association (ABTO) report, initiated in 1997 (19)

Distinct from North America and some countries in Europe, Brazil’s lung allocation system respects the chronological listing time, not specific prognostic scores such as Organ Procurement Transplantation Network (OPTM) Lung Allocation Score (20). On the other hand, similarly to the worldwide tendencies, Brazilian programs are performing progressively more bilateral transplants with increasing use of ECMO technology, with comparable survival results to those reported in the international literature (21).

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic had an important impact on waitlist mortality and organ donation and even brought the possibility of lung transplantation to acute lung failure recipients after SARS-CoV2 infection, with a total of eight patients submitted to the surgery in different centers after continuous ethical discussions and definition of national specific selection criteria.

In addition to that and still taking into consideration the COVID pandemic scenario, the last 2 years in Brazil brought unprecedent dares and apprenticeship, also consolidating the concept (already well accepted in the country, even before the pandemic) that the thoracic surgeon is a paramount specialist within the intensive care unit, which must work in close contact with other key healthcare specialties in this environment. We believe this idea is also being reinforced worldwide.

Future perspectives and challenges

Being an emergent country, Brazil faces difficulties continuously. As it can be easily presumed, it wouldn’t be any different at all for the Brazilian thoracic surgery.

To minimize and neutralize the enormous disparity of the availability and excellence of the medical assistance, as well as to widespread the capacity to produce good quality scientific content within the specialty in the country is one of the biggest challenges to be defeated. To achieve that, it is necessary to invest not only on the thoracic surgeon, but also on a whole social, economic and cultural complex chain of events that could ultimately decrease the huge and dominant social inequality currently present in Brazil. It is not only a medical issue, but an everyone’s effort, probably taking an entire generation time to be accomplished.

Another important question that must be discussed is to reduce the imbalance and heterogeneousness between the thoracic surgery residence programs, as well as to amplify the number of resident positions across the country, so more qualified specialists can be prepared in the future, to be distributed more equally all over the country.

Conclusions

Brazil definitely plays a leading role in thoracic surgery within Latin America.

For a country of continental proportions, an overview of national thoracic surgery is equally complex and difficult to summarize in a single paper.

In one hand, the specialty is undoubtedly strong and mighty regarding practicing the most up-to-date techniques in minimally invasive platforms and lung transplantation, reproducing good standards of quality, comparable to those observed in the most prestigious places where thoracic surgery is also performed in the western world.

In the other hand, the specialty unfortunately still struggles with situations commonly seen in big countries with low-middle incomes, leading to regional disparities which make this qualified medical assistance non-universally available to the totality of its population.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

We would like to deeply thank the Brazilian Thoracic Surgery Society (SBCT), all the surgeons and colleagues who kindly shared experiences and data for this paper, allowing the enrichment of the debate about the national panorama of thoracic surgery in Brazil.

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: Both authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Alan D. L. Sihoe) for the series “Thoracic Surgery Worldwide” published in Journal of Thoracic Disease. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-21-1809/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-21-1809/coif). The series “Thoracic Surgery Worldwide” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. FV reports that he received 2 presentation honorariums from AstraZeneca Brazil, and he was the Former International Secretary for international affairs of Brazilian Society of Thoracic Surgery. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), Access on November 6th 2021. Available online: https://cnae.ibge.gov.br/en/component/content/article/97-7a12/7a12-voce-sabia/curiosidades/1629-o-tamanho-do-brasil.html

- 2.Costa IA. História da cirurgia cardíaca brasileira. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 1998. doi: . 10.1590/S0102-76381998000100002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheffer M, Cassenote A, Guerra A, et al. Demografia Médica no Brasil 2020. São Paulo, SP: FMUSP, CFM, 2020:312. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tedde ML, Petrere O, Jr, Pinto Filho DR, et al. General thoracic surgery workforce: training, migration and practice profile in Brazil. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;47:e19-24. 10.1093/ejcts/ezu411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Access on November 6th 2021. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/

- 6.Tsukazan MTR, Terra RM, Detterbeck F, et al. Management of lung nodules in Brazil-assessment of realities, beliefs and attitudes: a study by the Brazilian Society of Thoracic Surgery (SBCT), the Brazilian Thoracic Society (SBPT) and the Brazilian College of Radiology (CBR). J Thorac Dis 2018;10:2849-56. 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comissão Nacional de Residência Médica. Matriz de Competências Cirurgia Cardiovascular. Resolução CNRM nº2 de 04 de abril de 2019. Access on November 6th 2021. Available online: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=111191-resolucao-n-2-de-4-de-abril-de-2019-diario-oficial-da-uniao-imprensa-nacional&category_slug=abril-2019-pdf&Itemid=30192

- 8.Barbosa GV. Um novo programa de residência médica em cirurgia cardiovascular com acesso direto. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc [online]. 2006;21(4). Access on November 6th 2021. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S0102-76382006000400005 [DOI]

- 9.Vannucci F, Gonzalez-Rivas D. Is VATS lobectomy standard of care for operable non-small cell lung cancer? Lung Cancer 2016;100:114-9. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terra RM, Kazantzis T, Pinto-Filho DR, et al. Anatomic pulmonary resection by video-assisted thoracoscopy: the Brazilian experience (VATS Brazil study). J Bras Pneumol 2016;42:215-21. 10.1590/S1806-37562015000000337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzukazan MT, Schettini M, Terra RM, et al. Lobectomia por neoplasia, qual é a realidade brasileira? Análise do banco de dados da SBCT. Paper presented at: XXII Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Torácica; May 13th to 15th, 2021; Florianópolis, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terra RM, Bibas BJ, Haddad R, et al. Robotic thoracic surgery for non-small cell lung cancer: initial experience in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol 2020;46:e20190003. 10.1590/1806-3713/e20190003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terra RM, Lauricella LL, Haddad R, et al. Robotic anatomic pulmonary segmentectomy: technical approach and outcomes. Segmentectomia pulmonar anatômica robótica: aspectos técnicos e desfechos. Rev Col Bras Cir 2019;46:e20192210. 10.1590/0100-6991e-20192210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leite PHC, Mariani AW, Araujo PHXN, et al. Robotic thoracic surgery for inflammatory and infectious lung disease: initial experience in Brazil. Rev Col Bras Cir 2021;48:e20202872. 10.1590/0100-6991e-20202872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terra RM, Leite PHC, Dela Vega AJM. Robotic lobectomy: how to teach thoracic residents. J Thorac Dis 2021;13:S8-S12. 10.21037/jtd-20-1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terra RM, Haddad R, de Campos JRM, et al. Building a Large Robotic Thoracic Surgery Program in an Emerging Country: Experience in Brazil. World J Surg 2019;43:2920-6. 10.1007/s00268-019-05086-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terra RM, Leite PHC, Dela Vega AJM. Global status of the robotic thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2021;13:6123-8. 10.21037/jtd-19-3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agência Brasil, Brasil tem o maior sistema público de transplantes. Access on November 6th 2021. Available online: https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/saude/noticia/2019-09/brasil-tem-o-maior-sistema-publico-de-transplantes

- 19.Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgaõs (ABTO). Registro Brasileiro de transplantes. Ano XXVII, n2, 2021. Access on November 6th 2021. Available online: https://site.abto.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/rbt1sem-naoassociado-1.pdf

- 20.Rodrigues-Filho EM, Franke CA, Junges JR. Lung transplantation and organ allocation in Brazil: necessity or utility. Revista De Saúde Pública 2019;53:23. 10.11606/S1518-8787.2019053000445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afonso Júnior JE, Werebe Ede C, Carraro RM, et al. Lung transplantation. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13:297-304. 10.1590/S1679-45082015RW3156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as