Abstract

In this Perspective, we discuss what we perceive to be the continued challenges faced in catalytic hydrophosphination chemistry. Currently the literature is dominated by catalysts, many of which are highly effective, that generate the same phosphorus architectures, e.g., anti-Markovnikov products from the reaction of activated alkenes and alkynes with diarylphosphines. We highlight the state of the art in stereoselective hydrophosphination and the scope and limitations of chemoselective hydrophosphination with primary phosphines and PH3. We also highlight the progress in the chemistry of the heavier homologues. In general, we have tried to emphasize what is missing from our hydrophosphination armament, with the aim of guiding future research targets.

Keywords: hydrophosphination, hydropnictogenation, phosphines, catalysis, P−C bond formation

1. Introduction

Catalytic hydrophosphination (HP) reactions provide an attractive route to form new P–C bonds under atom-economical conditions. This supposed synthetic simplicity has galvanized research in this area to meet the demand for phosphorus-containing ligands and substrates in the fine-chemical, pharmaceutical, and agricultural industries.1−5 Indeed, some notable (and otherwise challenging) hydrophosphination protocols have been reported in the patent literature,6 including the HP of unactivated substrates such as cyclooctadiene (COD) and limonene to generate 9-phosphabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane and 4,8-dimethyl-2-phosphabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane, respectively. The HP of these unactivated substrates requires handling of PH3 under pressure at high temperature and is often radical-mediated. However, in general a number of challenges are still pervasive in catalytic HP reactions: (i) regioselectivity in the form of Markovnikov and anti-Markovnikov products, (ii) stereoselectivity, (iii) chemoselectivity when using primary phosphines, and (iv) reactivity involving unactivated substrates and phosphines as the reagents (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Current challenges in catalytic hydrophosphination reactions.

Compared to catalytic HP, catalytic hydroamination is a more established field. Great strides have already been taken to overcome similar selectivity issues and, importantly, to produce synthetically relevant molecules.7−9 Although there are still obstacles within hydroamination chemistry, notable recent examples include work by Knowles and co-workers on intermolecular hydroamination of unactivated alkenes with cyclic and acyclic secondary amines to give exclusively anti-Markovnikov products under photocatalytic conditions.10 The seminal work by Bertrand and co-workers in 2008 synthesized imines, enamines, and allyl amines from the hydroamination of alkynes or allenes with the simplest of amines, ammonia,11 which in itself is still a very challenging avenue of hydroamination research.12

HP reactions have, thus far, not emulated similar indirect hydroamination reactions, for example, work from Baran and co-workers disclosing the hydroamination of alkenes starting from nitro(hetero)arenes13 or work by Buchwald and co-workers on asymmetric hydroamination of unactivated internal alkenes starting from hydroxylamine esters.14 In part this is due to the lack of access to analogous starting phosphine feedstocks. Simply going down the pnictogen group from nitrogen to phosphorus has proven to be nontrivial for analogous hydrofunctionalization reactions, as the chemist simply does not have access to the same chemical toolbox of reactions that hydroamination proffers.

This Perspective aims to review state of the art catalytic HP reactions that in part address the aforementioned challenges and is not a comprehensive history of HP15−22 or indeed the adjacent phosphination,23 hydrophosphinylation, and hydrophosphonylation24−27 reactions, for which there are numerous excellent reviews already. We summarize the current limitations of HP reactions, and in addition, we hope to draw parallels and highlight any lessons that can be applied from HP reactions toward the heavier hydropnictogenation reactions. However, after decades of active research into HP reactions, including work from our group,28−35 the progress in improving even regioselectivity issues has been incremental. We now must ask: is HP the most viable, atom-economical, synthetic route to obtain novel phosphorus precursors?

2. Hydrophosphination

2.1. Regioselectivity

2.1.1. Intermolecular HP

To date, there is a paucity of literature on the selective formation of the more synthetically challenging Markovnikov product from catalytic HP. Instead, the anti-Markovnikov product is almost exclusively formed irrespective of the catalytic system, i.e., different metals, different ligand scaffolds, different solvents and temperatures. In 2003, Beletskaya and co-workers reported the HP of six alkenylalkyl ether substrates with diphenylphosphine mediated by either a nickel or palladium precatalyst at 80 °C to give selectively the Markovnikov product in good yields.36 Here an activated alkene was still required, and the phosphine was limited to Ph2PH. In the same year, Mimeau and Gaumont demonstrated the switchable addition of the P–H bond of protected secondary phosphines across terminal alkynes to give either the Z-selective anti-Markovnikov product under microwave irradiation or the Markovnikov product when the HP was mediated by a Pd catalyst (Scheme 1).37 During the screening process, when diphenylphosphine-borane was reacted with 1-octyne, various Pd precatalysts were used, and all showed selective formation of the Markovnikov product, suggesting that the regioselectivity is independent of the ligand scaffold around the Pd center—although the overall yield varied from moderate to excellent. However, changing the secondary phosphine-borane to methyl(phenyl)phosphine-borane resulted in a decrease in the regioselectivity. Unfortunately, the scope of this investigation was limited, so the origin of the regioselectivity could not be elucidated further by the authors. Following up this work, Gaumont and co-workers reported the same regioselectivity for the HP of 1-ethynylcyclohexene but also installing a stereogenic P center when the reaction was mediated using a chiral Pd catalyst, with the best result giving 70% conversion and 42% e.e., representing the first example of an HP reaction forming a vinylphosphine with a stereogenic P center.38

Scheme 1. Divergent Regioselective HP of Terminal Alkynes with Phosphine-Boranes under Palladium Catalysis or Microwave Irradiation.

Moving away from the Noble metals, in 2013 Gaumont and co-workers were able to further demonstrate switchable regioselectivity for the HP of a number of alkenyl arenes using inexpensive and benign iron salts (Scheme 2).39 With FeCl2 salt (30 mol %) in acetonitrile at 60 °C, the anti-Markovnikov product was always selectively formed in excellent yield for terminal alkenyl arenes. However, for 1,1-disubstituted alkenyl arenes, poor yields were obtained even upon heating to 90 °C. Impressively, simply changing the precatalyst to FeCl3 salt (30 mol %) resulted in the formation of the complementary Markovnikov products. Furthermore, increasing the temperature to 90 °C allowed access to the desired Markovnikov products for the HP of 1,1-disubstituted alkenyl arenes in good to excellent yields. To date, this study still represents one of the most elegant and simple catalytic systems to access the Markovnikov products from the HP of styrene derivatives.

Scheme 2. Divergent Regioselective HP of Styrene Derivatives with Ph2PH Mediated by FeCl2 and FeCl3.

In 2017, we reported the HP of terminal alkynes with an iron(II) β-diketiminate precatalyst (Scheme 3).32 When HP was performed in dichloromethane at 70 °C the Z-selective anti-Markovnikov product was formed. However, when HP was performed in benzene at 50 °C, the Markovnikov product was formed. Both transformations used the same Fe(II) precatalyst. Preliminary mechanistic studies indicated that the different oxidation states of iron were the origin of the divergent selectivity, with the Markovnikov addition showing involvement of radicals and retention of the Fe(II) oxidation state.

Scheme 3. Divergent Regioselective HP of Terminal Alkynes with Ph2PH in Different Solvents.

2.1.2. Intramolecular HP

Having both the unsaturated moiety and P–H bond on the same molecule can help bias the system to undergo anti-Markovnikov or Markovnikov addition because certain ring sizes are favored (Scheme 4). Early examples by Marks and co-workers disclosed the intramolecular HP of primary and secondary phosphinoalkynes and -alkenes mediated by lanthanide complexes.40−42 Markovnikov addition was favored to give the five-membered phospholane as the major product, with the anti-Markovnikov six-membered phosphorinane product detected as the minor product that forms under noncatalytic conditions. Furthermore, in 2016 we reported the first Fe(II)-mediated HP of nonactivated primary phosphinoalkenes and -alkynes to selectively give the Markovnikov addition products.29

Scheme 4. Intramolecular HP as a Strategy to Favor Markovnikov or Anti-Markovnikov Addition.

To date, there are only a handful of reports on intramolecular HP simply because synthesizing these phosphinoalkyne and -alkene starting materials is nontrivial. However, in 2018 Waterman and co-workers demonstrated the sequential intermolecular HP of 1,4-pentadiene with PhPH2 to give the corresponding anti-Markovnikov alkenylphosphine.43 The alkenylphosphine then underwent intramolecular anti-Markovnikov HP to give the six-membered phosphorinane product (Scheme 5). This sequential inter- then intramolecular HP is an attractive route to form these P-heterocycles but is currently substrate-limited.

Scheme 5. Sequential HP of 1,4-Pentadiene.

2.2. Stereoselectivity

Product distributions due to stereoselective catalytic HP can fall into two categories; Z or E isomers from anti-Markovnikov addition of the P–H bond across alkynes or from asymmetric HP to generate products containing chiral phosphorus and/or carbon centers. As mentioned, most HP reactions give the anti-Markovnikov product, and generally for the HP of alkynes, the P–H bond is added in an anti fashion to furnish the Z isomer as the major product (vide supra).44 A rare example of syn addition was reported by Oshima and co-workers on the HP of internal and terminal alkynes using Ph2PH mediated by [Co(acac)2] (10 mol %)/BuLi (20 mol %) to give the E isomer as the major product (Scheme 6a).45 In 2018, Shanmugam, Shanmugam, and co-workers reported a well-defined [Co(PMe3)4] precatalyst to also effect the E-selective HP of internal and terminal alkynes with an emphasis on elucidating the mechanism (Scheme 6b).46

Scheme 6. Cobalt-Catalyzed HP of Alkynes.

In principle, asymmetric HP is an incredibly powerful synthetic route to access the next generation of chiral phosphine ligands. This area of HP has been dominated by palladium complexes bearing chiral chelating auxiliaries.47−66 However, there have been early examples of nickel-catalyzed67,68 and organocatalytic69−71 asymmetric HP. More recently Wang and co-workers reported the asymmetric HP of numerous azabenzonorbornadiene and oxabenzonorbornadiene substrates with different secondary biarylphosphines mediated by palladium precatalyst and Fe(OAc)2 as a substoichiometric additive (Scheme 7).72 This research deviated from the usual α,β-unsaturated substrates (ketones and imines) used in previous asymmetric HP reactions involving palladium (vide supra) and instead involved a “non-electronically-activated double bond”. The authors stipulated that the proximity of this double bond to the high angle strain associated with the cyclic heteroatom allowed access to reactivity to form the products in moderate to excellent yields with excellent enantioselectivity. A proof of concept was further demonstrated by the group using their novel chiral phosphine ligands in asymmetric addition of phenylboronic acid to aryl aldehydes.

Scheme 7. Asymmetric HP of Heterobicyclic Alkenes to Furnish Novel Chiral Phosphine Ligands.

In 2020, Yin and co-workers disclosed the Cu-catalyzed asymmetric HP of α,β-unsaturated amides with Ph2PH to furnish C-chiral products in good to excellent yields with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 8).73 More impressively, using unsymmetrical ArPhPH, six new products containing both P-chiral and C-chiral centers were formed, albeit in moderate isolated yields with moderate diastereoselectivity but high enantioselectivity.

Scheme 8. Cu-Catalyzed Asymmetric HP of α,β-Unsaturated Amides.

Furthering the progress originally reported by Glueck and co-workers on the HP of vinyl nitriles,74,75 Harutyunyan and co-workers demonstrated the Mn(I)-catalyzed asymmetric anti-Markovnikov HP of vinyl nitriles and α,β-unsaturated nitriles using Clarke’s chiral proligand (Scheme 9).76 Mechanistically, the authors suggested that the HP proceeded via metal–ligand cooperation, and the origin of the enantioselectivity was assessed by computational studies. The same group expanded the HP strategy toward α,β-unsaturated phosphine oxides to form a range of enantiopure 1,2-bisphosphine ligands.77

Scheme 9. Mn(I)-Catalyzed Asymmetric HP of Vinyl Nitriles and α,β-Unsaturated Nitriles76.

2.3. Chemoselectivity

Using secondary phosphines (R1R2PH) for HP reactions allows the formation of tertiary-phosphine-containing products with no possibility of a second hydrophosphination event occurring. However, if primary phosphines (RPH2) are used, then the secondary phosphine product that is initially formed could undergo competing HP with the unsaturated substrate. This reactivity is strictly different from the reaction of 2 equiv of phosphine (R1R2PH, where R = H or alkyl/aryl) with 1 equiv of substrate bearing a triple-bond moiety. For consistency with the literature, we will follow naming the latter reaction as double hydrophosphination (itself an elusive and challenging transformation78−81,33) and the chemoselectivity issue arising from using a primary phosphine as single and double activation, respectively (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10. Chemoselective Single Addition or Double Addition of RPH2 to an Unsaturated Substrate to Furnish the 2° or 3° Phosphine, Respectively, versus Double Hydrophosphination.

There are a few examples of HP reactions involving primary phosphines, with most of the reports restricted to styrene as the substrate and PhPH2 as the primary phosphine.82−85,30,86,87 To date, one of the best examples was reported in 2014 by Waterman and co-workers on the HP of alkenes and dienes catalyzed by a triamidoamine-supported zirconium complex under mild conditions with 2:1 PhPH2:substrate stoichiometry to selectively form the secondary phosphine product (Scheme 11a).88 Progress on Zr-catalyzed single activation of RPH2 has been made since then by Waterman and co-workers, including the use of a chiral secondary phosphine with various alkenes89 and, more recently, light-driven Zr catalysis using different secondary phosphines (RPH2, where R = cyclohexyl, phenyl, or mesityl) with much shorter reaction times and slightly expanded scope relative to the seminal work.43 There are even fewer examples of HP using primary phosphines with alkynes.90,91 One reason for this could be competitive binding of the generated vinylphosphine product (from the first activation event) to the HP catalyst over the alkyne substrate.92−97 However, Bange and Waterman expanded the Zr-catalyzed HP procedure to internal alkynes with PhPH2.98 They found that the formation of the single-activation vinylphosphine product occurs first; this product can be isolated (although with poor E/Z selectivity) or proceed to react with a second equivalent of PhPH2 (double hydrophosphination) to obtain 1,2-bis(phosphino)alkane products after a protracted time frame (Scheme 11b). The same report also disclosed the reaction of PhPH2 with acetylene to furnish 1,2-bis(phenylphosphino)ethane in 65% yield, which is impressive because the acetylene was postulated to deactivate the catalyst and the zirconium catalyst was known to have poor reactivity with terminal alkynes.99,100

Scheme 11. (a) Chemoselective Formation of 2° Phosphine from Single Addition of PhPH2 to Styrene Derivatives; (b) Sequential Single Addition of PhPH2 to Internal Alkynes Followed by a Second HP with PhPH2 to Furnish 1,2-Bis(phosphino) Substrates.

2.4. Heteroallenes and PH3

Heteroallenes as substrates have been far less explored in HP reactions due to the propensity for unwanted side reactivity such as cyclotrimerization101 and selectivity issues with either single or double insertion. The products offer novel ligand scaffolds that could be employed in catalysis.102,103 Examples include HP of carbodiimides (RN=C=NR′) and isocyanates (RN=C=O), and these transformations have been dominated by main group-,104,105 lanthanide-,106−109 and actinide-based110,111 catalysis, with some p-block catalysis112−114 being reported in the past decade (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12. Single HP of Isocyanates and Carbodiimides.

In 2017, Kays and co-workers reported the first transition-metal-catalyzed HP of isocyanate using Fe(II) precatalysts.115 The expected single insertion of RN=C=O into Ph2PH was observed as one of the products, but an unprecedented second product was also identified as the double insertion of RN=C=O into Ph2PH to form a new family of phosphinodicarboxamide products. By tailoring the steric bulk of the R groups of the isocyanates, the single-insertion product can be exclusively formed with more bulky substituents. Changing the solvent from C6D6 to THF also renders exclusively the single-insertion product. Since 2017, expansion into other transition metal complexes to achieve the successful HP of heteroallenes and heterocumulenes has been reported.116−118

More recently, Nakazawa and co-workers reported the HP of a variety of RN=C=O (R = aryl or alkyl) with Ph2PH without any solvent at room temperature and short reaction times (0.25–12 h) to afford the single-insertion products.119 In addition, the single HP of phenylisocyanate with the primary phosphine PhPH2 was also achieved to give the product in 71% yield, although this required 3 days for completion.

Catalytic HP reactions using PH3 are niche. The high toxicity and specialized equipment required to use this gas have resulted in very few examples being reported to date.120 In the 1990s, Pringle and co-workers led the way using platinum complexes to effect the HP of formaldehyde,121,122 ethyl acrylate,123 and acrylonitrile124,125 with PH3—for each substrate, the tertiary phosphine products can be selectively formed over time. Interestingly, the secondary phosphine products were observed by 31P NMR spectroscopy in these reactions, but access to these secondary phosphine products would therefore require careful monitoring of the reaction time and nontrivial separation methods. However, in 2019 Trifonov and co-workers reported the regio- and chemoselective HP of styrene with PH3 mediated by M(II) (M = Ca, Yb, Sm) bis(amido) complexes supported by N-heterocyclic carbene ligands.126 Controlling the ratio of styrene to PH3, the anti-Markovnikov secondary or tertiary phosphine could be formed selectively (Scheme 13a). The substrate scope was expanded to 2-vinylpyridine, unfortunately with a loss of chemoselectivity and longer reaction time. Other alkene substrates, including 1-nonene, 2,3-dimethylbutadiene, cyclohexene, and norbornene, did not react with PH3. Instead, the HP of phenylacetylene with PH3 was achieved to give exclusively tertiary tris(Z-styryl)phosphine regardless of the ratio of substrate to PH3 (Scheme 13b). Control experiments showed that the free N-heterocyclic carbenes were also capable of mediating these HP reactions with PH3, albeit with poorer chemoselectivity and again slower reactivity. Nevertheless, this work shows very promising results in using PH3 to form simple but synthetically useful secondary phosphine precursors with non-precious-metal catalysts.

Scheme 13. (a) Regio- and Chemoselective HP of Styrene with PH3 by Altering the Substrate:PH3 Ratio; (b) Exclusive Formation of Tris(Z-styryl)phosphine from HP of Phenylacetylene with PH3.

In 2022, Liptrot and co-workers reported the formation of secondary and primary phosphines, including PH3, from reduction of the corresponding phosphorus(III) esters with pinacolborane mediated by a Cu(I) precatalyst.127 Subsequent HP of heterocumulenes was achieved using these phosphines generated in situ with the same precatalyst to give the single-addition products in moderate to good yields.

3. Limitations

3.1. Product Diversity

The examples outlined above are the current state of the art in HP catalysis and are absolutely worthy of note. However, it is fair to say that they are not representative of the field as a whole. In general, the products of HP share very similar structural motifs, regardless of the choice of catalyst. Indeed, most reports of HP focus on diarylphosphines and activated alkenes (likely because this is necessary to avoid any issues of regio- or chemoselectivity). For example, even a brief literature search revealed >40 reports on the anti-Markovnikov HP of styrene with Ph2PH. An exciting development that moves away from Ph2PH is Benhida and Cummins’ use of bis(trichlorosilyl)phosphine, (Cl3Si)2PH, which can be used for UV-light-mediated anti-Markovnikov HP of unactivated alkenes.128 The activity of this system serves to further highlight the opportunities that still exist in HP if we move away from traditional catalyst systems or if we develop more active catalysts that can compete with a UV-light-mediated reaction. The issue of anti-Markovnikov selectivity is compounded further by the fact that the thermally induced, catalyst-free HP occurs with near-perfect anti-Markovnikov selectivity.129 Thus, many reported HP catalysts are simply lowering the barrier toward product formation rather than allowing access to difficult-to-prepare P-containing products. One could even go as far as to say that the anti-Markovnikov-selective catalysis of diarylphosphines with activated alkenes undermines the often-cited selling point of HP. Phosphorus-containing compounds are ubiquitous in chemistry, but how many times has (2-phenylethyl)diphenylphosphine been used as a ligand, for example? The answer is only a handful, and therefore, does the demand for such products reflect the abundance of HP catalysis reported?130−134

Of course, the field has been expanded to included alkynes and other hetero-unsaturated species, which allows for some increased diversity in product formation, and indeed some of the products are unique and warrant additional focus (vide supra).115,127 For example, the vinylphosphines generated from HP of alkynes can potentially be further functionalized by HP, but the products of this transformation are ultimately usually limited to functionalized 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane (dppe) derivatives.81,135,136

To build truly diverse HP products and construct molecular complexity from simple molecules, we need more potent catalysts, including catalysts that can facilitate HP of even the most unactivated substrates. The grand goal should be to use HP to expand the phosphorus pool and to access bespoke phosphines. Functionalizing a primary phosphine to generate new P*RR′R″ species would be a very powerful use of HP. However, with primary phosphines overfunctionalization becomes a problem, which then brings us to our next major stumbling block: selectivity.

3.2. Selectivity

The first and most obvious selectivity hurdle to overcome is the considerable anti-Markovnikov regioselectivity associated with HP. If any progress is to be made, we need catalysts that subvert this selectivity bias and reliably afford the Markovnikov products. Some Markovnikov-selective regimes have been reported (vide supra), but most still require activated substrates. One of the few exceptions to this comes from Marks and our own report on the HP of nonactivated primary phosphinoalkenes and alkynes, though we openly note that the intramolecular nature of the reaction necessitates the HP of the otherwise unactivated alkene.41,29 Furthermore, the elevated temperature associated with our HP catalysis means that stereoselectivity could not be achieved.

As mentioned above, controlled, chemoselective HP catalysis utilizing primary phosphines (or even PH3) is highly desirable. However, because of the propensity for overfunctionalization, this remains a considerable challenge. Very few catalysts are effective at chemoselectively affording the single-activation product; when they are effective, they typically (of course) form the anti-Markovnikov product. This then only leaves the issue of stereoselectivity—perhaps the most challenging yet desirable of all. Developing chiral variants of known HP catalysts is challenging enough, but the difficulty is often compounded by the need for elevated temperatures as well as evidence for radical mechanisms in HP.32 Notably, however, the most successful catalysts in enantioselective HP are those that can operate at low temperatures, conferring a need for more active catalysts that can operate as such. Additionally, asymmetric HP suffers from the same overarching problem discussed throughout: the need for activated substrates. The azabenzonorbornadiene and oxabenzonorbornadiene derivatives described above as asymmetric HP substrates successfully deviate from the classical unsaturated substrates (Scheme 7).72 However, the procedure is restricted to the familiar diarylphosphines and (while the double bond is not nonelectronically activated) utilizes strained double bonds.

All of these issues must be overcome individually first if there is any hope to make HP a truly useful synthetic tool. The grand goal must be generalizable HP of unactivated substrates with complete tunability of the regio-, chemo- and enantioselectivity (Scheme 14). It is an ambitious goal, but a necessary one if HP is going to be the future of P–C bond-forming chemistry. It is clear that a major breakthrough is necessary in order to use HP to access P-containing species of significant value.

Scheme 14. Hypothetical, Modular, and Effective Use of HP to Synthesize Highly Functionalized Bespoke Phosphines.

4. Heavier-Congener Hydropnictogenation

The significant advances in main-group chemistry over the last few decades have prompted interest in the heavier pnictogen congeners and their corresponding hydropnictogenation reactions.137−140 Compared to the abundance of HP reports, these heavier hydrofunctionalization endeavors are still in their infancy, and the very act of catalytic hydrobismuthation (unreported to our knowledge) would be a remarkable achievement. However, while we can make a direct link between HP and the potential for novel ligand design, a relationship to applications of the heavier homologues is less clear. Furthermore, the same limitations are already emerging, and we hope that this Perspective will assist those undertaking hydropnictogenation research into striving for more diverse reactivity than is currently observed in the field of HP.

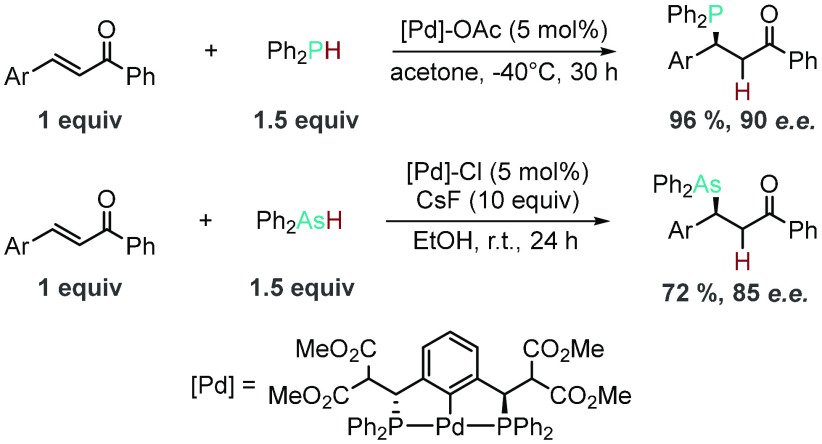

Leung and co-workers have already shown that there is transferable knowledge between HP and the heavier analogues.141 They were able to use a very similar chiral palladium catalyst to effect the HP and hydroarsination of internal alkenes with only minor catalyst alterations: changing the ancillary ligand from acetate to chloride (Scheme 15). Both transformations were optimized to give excellent yields and high enantioselectivity, albeit with the need for an activated alkene to partner with either Ph2PH or Ph2AsH.

Scheme 15. Analogous Pd-Catalyzed Hydrophosphination and Hydroarsination.

Waterman and co-workers have also achieved the single hydroarsination of phenylacetylene with Ph2AsH utilizing their triamidoamine-supported Zr catalyst (vide supra).142 Importantly, they also noted that the reaction occurs without the need for the zirconium catalyst when conducted in ambient lighting but required the catalyst in order to proceed in the dark. In this case the reaction afforded a 6.6:1 mixture of cis- and trans-vinylarsine products respectively. While this study was mainly a proof of concept of a then-rare hydroarsination, the selectivity observed is all too familiar with regard to HP.

Generally, reports of hydrostibination are fewer still, despite the fact that the first example was reported in 1965 (Scheme 16a).143 Since then, a handful of Lewis acid- or radical-initiated examples have been reported. More recently, Chitnis and co-workers reported a catalyst- and initiator-free hydrostibination by tuning the stibene backbone to stabilize the LUMO of the stibene (Scheme 16b). They later comprehensively studied the mechanism of this hydrostibination and suggested that a radical mechanism is at play.144 Finally, in the context of HP, it is important to note that all of the heavier-congener hydropnictogenations reported display near-perfect anti-Markovnikov selectivity.

Scheme 16. Catalyst-Free Hydrostibinations and an Arylbismuthation.

While there have been no reports of hydrobismuthation (likely because of the difficulty in isolating bismuth hydrides), there are reports of arylbismuthation, which we would be remiss not to highlight (Scheme 16c).145

5. Conclusions

While we understand that research progress takes time, the HP community is still plagued by the same challenges addressed in Waterman’s 2016 review.20 For HP to reach its true potential, we need a toolbox of HP catalysts that can incrementally build complexity about a P center. Ultimately, substrate scope is the most restrictive obstacle (followed closely by the regioselectivity issue), and these obstacles need to be addressed foremost before the focus is turned toward chemo- and stereoselectivity. Although HP of (for example) styrene with diphenylphosphine can be a useful test for the proficiency of a newly designed catalyst, if we cannot effectively utilize the restricted product pool of current HP or use HP to access bespoke phosphine architectures, then we must ask ourselves whether we are making enough of an advance in chemical research. A simple way to, as a minimum, offer up the potential for novel reactivity would be to include unactivated substrates in all HP studies, e.g., 1-hexene and Cy2PH in combination with Ph2PH or styrene. At the moment, the mechanism of HP is entirely limited by catalyst design, which results in oxidative addition of the HP bond across a metal center or a σ-bond-metathesis M–PR2 bond-forming step, both of which dictate anti-Markovnikov regiochemistry of the reaction.17 However, some of the most promising emerging HP catalysts (Schemes 8, 9, and 15) do not operate via these mechanisms, and while they are currently still substrate-limited, they have begun to tackle some of the most pressing limitations of HP and provide a promising direction for future research. This leaves the field in a predicament: either tangible solutions to the outstanding problems or new, innovative approaches are a necessity if we are to access novel phosphorus architectures in an atom-economical way.

Acknowledgments

The EPSRC and the Leverhulme Trust are thanked for funding.

Author Contributions

† S.L. and T.M.H. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Hartwig J. F.Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Zhang X.. Chiral Phosphines and Diphosphines. In Phosphorus(III) Ligands in Homogeneous Catalysis: Design and Synthesis; Kamer P. C. J., van Leeuwen P. W. N. M., Eds.; Wiley, 2012; pp 27–80. 10.1002/9781118299715.ch2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz R. W.; Ulrich A. E.; Eilittä M.; Roy A. Sustainable use of phosphorus: A finite resource. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461–462, 799–803. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phosphorus-Based Polymers: From Synthesis to Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry: 2014; pp P001–P004. [Google Scholar]

- Stec W. J.Phosphorus Chemistry Directed Towards Biology; Lectures presented at the International Symposium on Phosphorus Chemistry Directed Towards Biology, Burzenin, Poland, September 25–28, 1979; Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner G.; Heymer G.; Stephan H.-W.. Continuous production of organic phosphines. US 4163760 A, 1979.; Also see:; a Carreira M.; Charernsuk M.; Eberhard M.; Fey N.; Ginkel R. v.; Hamilton A.; Mul W. P.; Orpen A. G.; Phetmung H.; Pringle P. G. Anatomy of Phobanes. Diastereoselective Synthesis of the Three Isomers of n-Butylphobane and a Comparison of their Donor Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3078–3092. 10.1021/ja808807s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Abbenhuis H. C. L.; Burckhardt U.; Gramlich V.; Koellner C.; Pregosin P. S.; Salzmann R.; Togni A. Successful Application of a “Forgotten” Phosphine in Asymmetric Catalysis: A 9-Phosphabicyclo[3.3.1]non-9-yl Ferrocene Derivative as Chiral Ligand. Organometallics 1995, 14, 759–766. 10.1021/om00002a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller T. E.; Hultzsch K. C.; Yus M.; Foubelo F.; Tada M. Hydroamination: Direct Addition of Amines to Alkenes and Alkynes. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3795–3892. 10.1021/cr0306788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.; Arndt M.; Gooßen K.; Heydt H.; Gooßen L. J. Late Transition Metal-Catalyzed Hydroamination and Hydroamidation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2596–2697. 10.1021/cr300389u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge A.; Walton S. M.; Gaunt M. J. New Strategies for the Transition-Metal Catalyzed Synthesis of Aliphatic Amines. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2613–2692. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A. J.; Lainhart B. C.; Zhang X.; Naguib S. G.; Sherwood T. C.; Knowles R. R. Catalytic intermolecular hydroaminations of unactivated olefins with secondary alkyl amines. Science 2017, 355, 727–730. 10.1126/science.aal3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallo V.; Frey G. D.; Donnadieu B.; Soleilhavoup M.; Bertrand G. Homogeneous Catalytic Hydroamination of Alkynes and Allenes with Ammonia. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5224–5228. 10.1002/anie.200801136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiff S.; Jérôme F. Hydroamination of non-activated alkenes with ammonia: a holy grail in catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1512–1521. 10.1039/C9CS00873J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui J.; Pan C.-M.; Jin Y.; Qin T.; Lo J. C.; Lee B. J.; Spergel S. H.; Mertzman M. E.; Pitts W. J.; La Cruz T. E.; Schmidt M. A.; Darvatkar N.; Natarajan S. R.; Baran P. S. Practical olefin hydroamination with nitroarenes. Science 2015, 348, 886–891. 10.1126/science.aab0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Shi S.-L.; Niu D.; Liu P.; Buchwald S. L. Catalytic asymmetric hydroamination of unactivated internal olefins to aliphatic amines. Science 2015, 349, 62–66. 10.1126/science.aab3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glueck D. S. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Chiral Phosphanes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 7108–7117. 10.1002/chem.200800267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg S.; Stephan D. W. Stoichiometric and catalytic activation of P–H and P–P bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1482–1489. 10.1039/b612306f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L. Mechanisms of Metal-Catalyzed Hydrophosphination of Alkenes and Alkynes. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2845–2855. 10.1021/cs400685c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koshti V.; Gaikwad S.; Chikkali S. H. Contemporary avenues in catalytic PH bond addition reaction: A case study of hydrophosphination. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 265, 52–73. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wauters I.; Debrouwer W.; Stevens C. V. Preparation of phosphines through C–P bond formation. Belstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 1064–1096. 10.3762/bjoc.10.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bange C. A.; Waterman R. Challenges in Catalytic Hydrophosphination. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 12598–12605. 10.1002/chem.201602749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullarkat S. A. Recent Progress in Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrophosphination. Synthesis 2016, 48, 493–503. 10.1055/s-0035-1560556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzenine-Lafollée S.; Gil R.; Prim D.; Hannedouche J. First-Row Late Transition Metals for Catalytic Alkene Hydrofunctionalisation: Recent Advances in C-N, C-O and C-P Bond Formation. Molecules 2017, 22, 1901. 10.3390/molecules22111901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glueck D. S. Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis of P-Stereogenic Phosphines. Synlett 2007, 2007, 2627–2634. 10.1055/s-2007-991077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han L.-B.; Hua R.; Tanaka M. Phosphinic Acid Induced Reversal of Regioselectivity in Pd-Catalyzed Hydrophosphinylation of Alkynes with Ph2P(O)H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 94–96. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso F.; Beletskaya I. P.; Yus M. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Addition of Heteroatom–Hydrogen Bonds to Alkynes. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3079–3160. 10.1021/cr0201068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M.Homogeneous Catalysis for H-P Bond Addition Reactions. In New Aspects in Phosphorus Chemistry IV; Majoral J.-P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2004; pp 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gusarova N. K.; Chernysheva N. A.; Trofimov B. A. Catalyst- and Solvent-Free Addition of the P–H Species to Alkenes and Alkynes: A Green Methodology for C–P Bond Formation. Synthesis 2017, 49, 4783–4807. 10.1055/s-0036-1588542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher K. J.; Webster R. L. Room temperature hydrophosphination using a simple iron salen pre-catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 12109–12111. 10.1039/C4CC06526C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinal-Viguri M.; King A. K.; Lowe J. P.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. Hydrophosphination of Unactivated Alkenes and Alkynes Using Iron(II): Catalysis and Mechanistic Insight. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7892–7897. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher K. J.; Espinal-Viguri M.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. A Study of Two Highly Active, Air-Stable Iron(III)-μ-Oxo Precatalysts: Synthetic Scope of Hydrophosphination using Phenyl- and Diphenylphosphine. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 2460–2468. 10.1002/adsc.201501179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinal-Viguri M.; Mahon M. F.; Tyler S. N. G.; Webster R. L. Iron catalysis for the synthesis of ligands: Exploring the products of hydrophosphination as ligands in cross-coupling. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 64–69. 10.1016/j.tet.2016.11.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King A. K.; Gallagher K. J.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. Markovnikov versus anti-Markovnikov Hydrophosphination: Divergent Reactivity Using an Iron(II) β-Diketiminate Pre-Catalyst. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9039–9043. 10.1002/chem.201702374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles N. T.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. 1,1-Diphosphines and divinylphosphines via base catalyzed hydrophosphination. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10443–10446. 10.1039/C8CC05890C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R. L. Room Temperature Ni(II) Catalyzed Hydrophosphination and Cyclotrimerization of Alkynes. Inorganics 2018, 6, 120. 10.3390/inorganics6040120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A. N.; Sanderson H. J.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. Hydrophosphination using [GeCl{N(SiMe3)2}3] as a pre-catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13623–13626. 10.1039/D0CC05792D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazankova M. A.; Shulyupin M. O.; Beletskaya I. P. Catalytic Hydrophosphination of Alkenylalkyl Ethers. Synlett 2003, 2003, 2155–2158. 10.1055/s-2003-42092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mimeau D.; Gaumont A.-C. Regio- and Stereoselective Hydrophosphination Reactions of Alkynes with Phosphine–Boranes: Access to Stereodefined Vinylphosphine Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7016–7022. 10.1021/jo030096q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Join B.; Mimeau D.; Delacroix O.; Gaumont A.-C. Pallado-catalysed hydrophosphination of alkynes: access to enantio-enriched P-stereogenic vinyl phosphine–boranes. Chem. Commun. 2006, 3249–3251. 10.1039/B607434K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routaboul L.; Toulgoat F.; Gatignol J.; Lohier J.-F.; Norah B.; Delacroix O.; Alayrac C.; Taillefer M.; Gaumont A.-C. Iron-Salt-Promoted Highly Regioselective α and β Hydrophosphination of Alkenyl Arenes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 8760–8764. 10.1002/chem.201301417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass M. R.; Marks T. J. Organolanthanide-Catalyzed Intramolecular Hydrophosphination/Cyclization of Phosphinoalkenes and Phosphinoalkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1824–1825. 10.1021/ja993633q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass M. R.; Stern C. L.; Marks T. J. Intramolecular Hydrophosphination/Cyclization of Phosphinoalkenes and Phosphinoalkynes Catalyzed by Organolanthanides: Scope, Selectivity, and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 10221–10238. 10.1021/ja010811i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka A. M.; Douglass M. R.; Marks T. J. Homoleptic Lanthanide Alkyl and Amide Precatalysts Efficiently Mediate Intramolecular Hydrophosphination/Cyclization. Observations on Scope and Mechanism. Organometallics 2003, 22, 4630–4632. 10.1021/om030439a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bange C. A.; Conger M. A.; Novas B. T.; Young E. R.; Liptak M. D.; Waterman R. Light-Driven, Zirconium-Catalyzed Hydrophosphination with Primary Phosphines. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6230–6238. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HP of internal alkynes (e.g., 1-phenyl-1-propyne) often gives a mixture of E and Z isomers, and difficulties with separation and isolation have led to conflicting reports on the stereoisomer formed. See our recent report, which sets out our stance:Woof C. R.; Linford-Wood T. G.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. Catalytic hydrophosphination of allenes using an iron(II) β-diketiminate complex. Synthesis 2022, 10.1055/a-1902-5592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmiya H.; Yorimitsu H.; Oshima K. Cobalt-Catalyzed syn Hydrophosphination of Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2368–2370. 10.1002/anie.200500255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajpurohit J.; Kumar P.; Shukla P.; Shanmugam M.; Shanmugam M. Mechanistic Investigation of Well-Defined Cobalt Catalyzed Formal E-Selective Hydrophosphination of Alkynes. Organometallics 2018, 37, 2297–2304. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Ng J. K.-P.; Pullarkat S. A.; Liu F.; Li Y.; Leung P.-H. Asymmetric Synthesis of New Diphosphines and Pyridylphosphines via a Kinetic Resolution Process Promoted and Controlled by a Chiral Palladacycle. Organometallics 2010, 29, 3374–3386. 10.1021/om100358g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.-J.; Chen X.-F.; Shi M.; Duan W.-L. Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Addition of Diarylphosphines to Enones toward the Synthesis of Chiral Phosphines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5562–5563. 10.1021/ja100606v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Li Y.; Leung P.-H. Palladium(ii)-catalyzed asymmetric hydrophosphination of enones: efficient access to chiral tertiary phosphines. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 6950–6952. 10.1039/c0cc00925c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Yuan M.; Ding Y.; Li Y.; Leung P.-H. Palladium Template Promoted Asymmetric Synthesis of 1,2-Diphosphines by Hydrophosphination of Functionalized Allenes. Organometallics 2010, 29, 536–542. 10.1021/om900829t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M.; Pullarkat S. A.; Li Y.; Lee Z.-Y.; Leung P.-H. Novel Synthesis of Chiral 1,3-Diphosphines via Palladium Template Promoted Hydrophosphination and Functional Group Transformation Reactions. Organometallics 2010, 29, 3582–3588. 10.1021/om100505w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M.; Zhang N.; Pullarkat S. A.; Li Y.; Liu F.; Pham P.-T.; Leung P.-H. Asymmetric Synthesis of Functionalized 1,3-Diphosphines via Chiral Palladium Complex Promoted Hydrophosphination of Activated Olefins. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 989–996. 10.1021/ic9018053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D.; Duan W.-L. Palladium-catalyzed 1,4-addition of diarylphosphines to α,β-unsaturated N-acylpyrroles. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11101–11103. 10.1039/c1cc13785a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Chew R. J.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P.-H. Direct Synthesis of Chiral Tertiary Diphosphines via Pd(II)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrophosphination of Dienones. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5862–5865. 10.1021/ol202480r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.; Pullarkat S. A.; Ma M.; Li Y.; Leung P.-H. Chiral cyclopalladated complex promoted asymmetric synthesis of diester-substituted P,N-ligands via stepwise hydrophosphination and hydroamination reactions. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 5391–5400. 10.1039/c2dt12379g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.-J.; Huang M.; Lin Z.-Q.; Duan W.-L. Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric 1,4-Addition of Diarylphosphines to Nitroalkenes for the Synthesis of Chiral P,N-Compounds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 3122–3126. 10.1002/adsc.201200133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Chew R. J.; Pullarkat S. A.; Li Y.; Leung P.-H. Asymmetric Synthesis of Enaminophosphines via Palladacycle-Catalyzed Addition of Ph2PH to α,β-Unsaturated Imines. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6849–6854. 10.1021/jo300893s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Li Y.; Leung P.-H. Palladacycle-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrophosphination of Enones for Synthesis of C*- and P*-Chiral Tertiary Phosphines. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 2533–2540. 10.1021/ic202472f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D.; Lin Z.-Q.; Lu J.-Z.; Li C.; Duan W.-L. Palladium-catalyzed Asymmetric 1,4-Addition of Diarylphosphines to α,β-Unsaturated Carboxylic Esters. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2, 392–394. 10.1002/ajoc.201300021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Ye J.; Duan W.-L. Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Addition of Diarylphosphines to α,β-Unsaturated Sulfonic Esters for the Synthesis of Chiral Phosphine Sulfonate Compounds. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5016–5019. 10.1021/ol402351c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P.-H.. Chiral Metal Complex-Promoted Asymmetric Hydrophosphinations. In Hydrofunctionalization; Ananikov V. P., Tanaka M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 2013; pp 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Chew R. J.; Teo K. Y.; Huang Y.; Li B.-B.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P.-H. Enantioselective phospha-Michael addition of diarylphosphines to β,γ-unsaturated α-ketoesters and amides. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8768–8770. 10.1039/C4CC01610F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan K.; Sadeer A.; Xu C.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A. Asymmetric Construction of a Ferrocenyl Phosphapalladacycle from Achiral Enones and a Demonstration of Its Catalytic Potential. Organometallics 2014, 33, 5074–5076. 10.1021/om5007215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Ye J.; Duan W.-L. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric 1,6-addition of diarylphosphines to α,β,γ,δ-unsaturated sulfonic esters: controlling regioselectivity by rational selection of electron-withdrawing groups. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 698–700. 10.1039/C3CC46290K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.-Y.; Tay W. S.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P.-H. Asymmetric 1,4-Conjugate Addition of Diarylphosphines to α,β,γ,δ-Unsaturated Ketones Catalyzed by Transition-Metal Pincer Complexes. Organometallics 2015, 34, 5196–5201. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seah J. W. K.; Teo R. H. X.; Leung P.-H. Organometallic chemistry and application of palladacycles in asymmetric hydrophosphination reactions. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 16909–16915. 10.1039/D1DT03134A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadow A. D.; Haller I.; Fadini L.; Togni A. Nickel(II)-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Hydrophosphination of Methacrylonitrile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14704–14705. 10.1021/ja0449574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadow A. D.; Togni A. Enantioselective Addition of Secondary Phosphines to Methacrylonitrile: Catalysis and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17012–17024. 10.1021/ja0555163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlone A.; Bartoli G.; Bosco M.; Sambri L.; Melchiorre P. Organocatalytic Asymmetric Hydrophosphination of α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4504–4506. 10.1002/anie.200700754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahem I.; Rios R.; Vesely J.; Hammar P.; Eriksson L.; Himo F.; Córdova A. Enantioselective Organocatalytic Hydrophosphination of α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4507–4510. 10.1002/anie.200700916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahem I.; Hammar P.; Vesely J.; Rios R.; Eriksson L.; Córdova A. Organocatalytic Asymmetric Hydrophosphination of α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes: Development, Mechanism and DFT Calculations. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 1875–1884. 10.1002/adsc.200800277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Zhang H.; Yang Z.; Ding N.; Meng L.; Wang J. Asymmetric Hydrophosphination of Heterobicyclic Alkenes: Facile Access to Phosphine Ligands for Asymmetric Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 1457–1463. 10.1021/acscatal.8b04787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-B.; Tian H.; Yin L. Copper(I)-Catalyzed Asymmetric 1,4-Conjugate Hydrophosphination of α,β-Unsaturated Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20098–20106. 10.1021/jacs.0c09654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicht D. K.; Kourkine I. V.; Lew B. M.; Nthenge J. M.; Glueck D. S. Platinum-Catalyzed Acrylonitrile Hydrophosphination via Olefin Insertion into a Pt–P Bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 5039–5040. 10.1021/ja970355r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacik I.; Wicht D. K.; Grewal N. S.; Glueck D. S.; Incarvito C. D.; Guzei I. A.; Rheingold A. L. Pt(Me-Duphos)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrophosphination of Activated Olefins: Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral Phosphines. Organometallics 2000, 19, 950–953. 10.1021/om990882e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez J. M.; Postolache R.; Castiñeira Reis M.; Sinnema E. G.; Vargová D.; de Vries F.; Otten E.; Ge L.; Harutyunyan S. R. Manganese(I)-Catalyzed H–P Bond Activation via Metal–Ligand Cooperation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20071–20076. 10.1021/jacs.1c10756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L.; Harutyunyan S. R. Manganese(i)-catalyzed access to 1,2-bisphosphine ligands. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 1307–1312. 10.1039/D1SC06694C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani M.; Itazaki M.; Tamiya C.; Nakazawa H. Regioselective Double Hydrophosphination of Terminal Arylacetylenes Catalyzed by an Iron Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11932–11935. 10.1021/ja304818c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe A.; De Luca R.; Castarlenas R.; Pérez-Torrente J. J.; Crucianelli M.; Oro L. A. Double hydrophosphination of alkynes promoted by rhodium: the key role of an N-heterocyclic carbene ligand. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 5554–5557. 10.1039/C5CC09156J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J.; Zhu L.; Zhang J.; Li J.; Cui C. Sequential Addition of Phosphine to Alkynes for the Selective Synthesis of 1,2-Diphosphinoethanes under Catalysis. Well-Defined NHC-Copper Phosphides vs in Situ CuCl2/NHC Catalyst. Organometallics 2017, 36, 455–459. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackley B. J.; Pagano J. K.; Waterman R. Visible-light and thermal driven double hydrophosphination of terminal alkynes using a commercially available iron compound. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2774–2776. 10.1039/C8CC00847G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G.; Basuli F.; Kilgore U. J.; Fan H.; Aneetha H.; Huffman J. C.; Wu G.; Mindiola D. J. Neutral and Zwitterionic Low-Coordinate Titanium Complexes Bearing the Terminal Phosphinidene Functionality. Structural, Spectroscopic, Theoretical, and Catalytic Studies Addressing the Ti–P Multiple Bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13575–13585. 10.1021/ja064853o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basalov I. V.; Dorcet V.; Fukin G. K.; Carpentier J.-F.; Sarazin Y.; Trifonov A. A. Highly Active, Chemo- and Regioselective YbII and SmII Catalysts for the Hydrophosphination of Styrene with Phenylphosphine. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 6033–6036. 10.1002/chem.201500380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissel A. A.; Mahrova T. V.; Lyubov D. M.; Cherkasov A. V.; Fukin G. K.; Trifonov A. A.; Del Rosal I.; Maron L. Metallacyclic yttrium alkyl and hydrido complexes: synthesis, structures and catalytic activity in intermolecular olefin hydrophosphination and hydroamination. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12137–12148. 10.1039/C5DT00129C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basalov I. V.; Liu B.; Roisnel T.; Cherkasov A. V.; Fukin G. K.; Carpentier J.-F.; Sarazin Y.; Trifonov A. A. Amino Ether–Phenolato Precatalysts of Divalent Rare Earths and Alkaline Earths for the Single and Double Hydrophosphination of Activated Alkenes. Organometallics 2016, 35, 3261–3271. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapshin I. V.; Yurova O. S.; Basalov I. V.; Rad’kov V. Y.; Musina E. I.; Cherkasov A. V.; Fukin G. K.; Karasik A. A.; Trifonov A. A. Amido Ca and Yb(II) Complexes Coordinated by Amidine-Amidopyridinate Ligands for Catalytic Intermolecular Olefin Hydrophosphination. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 2942–2952. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibuzar M. P.; Dannenberg S. G.; Waterman R. A Commercially Available Ruthenium Compound for Catalytic Hydrophosphination. Isr. J. Chem. 2020, 60, 446–451. 10.1002/ijch.201900070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebreab M. B.; Bange C. A.; Waterman R. Intermolecular Zirconium-Catalyzed Hydrophosphination of Alkenes and Dienes with Primary Phosphines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9240–9243. 10.1021/ja503036z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bange C. A.; Ghebreab M. B.; Ficks A.; Mucha N. T.; Higham L.; Waterman R. Zirconium-catalyzed intermolecular hydrophosphination using a chiral, air-stable primary phosphine. Dalton Trans 2016, 45, 1863–1867. 10.1039/C5DT03544A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner M. E.; Parker B. F.; Hohloch S.; Bergman R. G.; Arnold J. Thorium Metallacycle Facilitates Catalytic Alkyne Hydrophosphination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12935–12938. 10.1021/jacs.7b08323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wang X.; Wang Y.; Yuan D.; Yao Y. Hydrophosphination of alkenes and alkynes with primary phosphines catalyzed by zirconium complexes bearing aminophenolato ligands. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 9090–9095. 10.1039/C8DT02122H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrick K.; Iggo J. A.; Mays M. J.; Raithby P. R. Transformations of a μ2-vinyl ligand at a dimanganese centre and the flexibility of μ2-acyl lignads; X-ray crystal structures of [(Ph2P)2N][Mn2(μ2-H){μ2-C(O)CPh: CHPh}(μ2-PPh2)(CO)6], [Mn2{μ2-C(O)CPh: CHPh}(μ2-PPh2)(CO)6(CNBut)2], and [Mn2{σ: η3-P(Ph)2CH:CH2}(CO)7(PEt3)]. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1984, 0, 209–211. 10.1039/C39840000209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier F.; Goff C. H.-L.; Ricard L.; Mathey F. Synthesis of η3-phosphaallyl-cobalt and -nickel complexes. Crystal structure of [η3-1-(2,4,6-tri-t-butylphenyl)-1-phosphaallyl]tricarbonylcobalt. J. Organomet. Chem. 1990, 389, 389–397. 10.1016/0022-328X(90)85433-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. L.; Nelson J. H.; Alcock N. W. Facile synthesis and structural characterization of [(Ph2PCHCH2)(μ- η 3-Ph2PCHCH2)PdI]2(BF4)2: unprecedented formation of a structurally unusual Palladium(I) complex. Organometallics 1990, 9, 1699–1700. 10.1021/om00119a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth G. Generation of a bridging ethenyl ligand at a di-iron centre via carbon–phosphorus bond cleavage. J. Organomet. Chem. 1991, 407, 91–95. 10.1016/0022-328X(91)83142-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morise X.; Green M. L. H.; McGowan P. C.; Simpson S. J. η-Cyclopentadienyltungsten compounds with vinyl- and allyl-phosphine ligands. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1994, 871–878. 10.1039/DT9940000871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acum G. A.; Mays M. J.; Raithby P. R.; Solan G. A. The reactions of tricobalt alkylidyne complexes [Co3(μ3–CR)(CO)9](R = Me, CO2Me) with the vinyl phosphine ligands PPh2CH=CH2 and cis-Ph2PCH=CHPPh2; crystal structure of [Co3(μ3–CCO2Me)(μ-Ph2PCH=CHPPh2)(CO)7]. J. Organomet. Chem. 1996, 508, 137–145. 10.1016/0022-328X(95)05774-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bange C. A.; Waterman R. Zirconium-Catalyzed Intermolecular Double Hydrophosphination of Alkynes with a Primary Phosphine. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6413–6416. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roering A. J.; Maddox A. F.; Elrod L. T.; Chan S. M.; Ghebreab M. B.; Donovan K. L.; Davidson J. J.; Hughes R. P.; Shalumova T.; MacMillan S. N.; Tanski J. M.; Waterman R. General Preparation of (N3N)ZrX (N3N = N(CH2CH2NSiMe3)33–) Complexes from a Hydride Surrogate. Organometallics 2009, 28, 573–581. 10.1021/om8008684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roering A. J.; Leshinski S. E.; Chan S. M.; Shalumova T.; MacMillan S. N.; Tanski J. M.; Waterman R. Insertion Reactions and Catalytic Hydrophosphination by Triamidoamine-Supported Zirconium Complexes. Organometallics 2010, 29, 2557–2565. 10.1021/om100216f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe H. R.; Geer A. M.; Williams H. E. L.; Blundell T. J.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Kays D. L. Cyclotrimerisation of isocyanates catalysed by low-coordinate Mn(ii) and Fe(ii) m-terphenyl complexes. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 937–940. 10.1039/C6CC07243G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamm R. J.; Day B. M.; Mansfield N. E.; Knowelden W.; Hitchcock P. B.; Coles M. P. Catalytic bond forming reactions promoted by amidinate, guanidinate and phosphaguanidinate compounds of magnesium. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14302–14. 10.1039/C4DT01097C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel R.; Schatte G.; Jessop P. G. Rh(i) and Ru(ii) phosphaamidine and phosphaguanidine (1,3-P,N) complexes and their activity for CO2 hydrogenation. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 12512–12521. 10.1039/C9DT00602H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-X.; Nishiura M.; Hou Z. Alkali-metal-catalyzed addition of primary and secondary phosphines to carbodiimides. A general and efficient route to substituted phosphaguanidines. Chem. Commun. 2006, 3812–3814. 10.1039/b609198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmin M. R.; Barrett A. G. M.; Hill M. S.; Hitchcock P. B.; Procopiou P. A. Heavier Group 2 Element Catalyzed Hydrophosphination of Carbodiimides. Organometallics 2008, 27, 497–499. 10.1021/om7011198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-X.; Nishiura M.; Mashiko T.; Hou Z. Half-Sandwich o-N,N-Dimethylaminobenzyl Complexes over the Full Size Range of Group 3 and Lanthanide Metals. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Catalysis of Phosphine P–H Bond Addition to Carbodiimides. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 2167–2179. 10.1002/chem.200701300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrle A. C.; Schmidt J. A. R. Insertion Reactions and Catalytic Hydrophosphination of Heterocumulenes using α-Metalated N,N-Dimethylbenzylamine Rare-Earth-Metal Complexes. Organometallics 2013, 32, 1141–1149. 10.1021/om300807k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X.; Zhang L.; Zhu X.; Wang S.; Zhou S.; Wei Y.; Zhang G.; Mu X.; Huang Z.; Hong D.; Zhang F. Synthesis of Bis(NHC)-Based CNC-Pincer Rare-Earth-Metal Amido Complexes and Their Application for the Hydrophosphination of Heterocumulenes. Organometallics 2015, 34, 4553–4559. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W.; Xu L.; Zhang W.-X.; Xi Z. Half-sandwich rare-earth metal tris(alkyl) ate complexes catalyzed phosphaguanylation reaction of phosphines with carbodiimides: an efficient synthesis of phosphaguanidines. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 7649–7655. 10.1039/C5NJ01136A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karmel I. S. R.; Tamm M.; Eisen M. S. Actinide-Mediated Catalytic Addition of E–H Bonds (E=N, P, S) to Carbodiimides, Isocyanates, and Isothiocyanates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12422–12425. 10.1002/anie.201502041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrice R. J.; Eisen M. S. Catalytic insertion of E–H bonds (E = C, N, P, S) into heterocumulenes by amido–actinide complexes. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 939–944. 10.1039/C5SC02746B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamm R. J.; Fulton J. R.; Coles M. P.; Fitchett C. M. Hydrophosphination-type reactivity promoted by bismuth phosphanides: scope and limitations. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 2068–2071. 10.1039/C7DT00226B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamm R. J.; Edwards A. J.; Fitchett C. M.; Coles M. P. A study of di(amino)stibines with terminal Sb(iii) hydrogen-ligands by X-ray- and neutron-diffraction. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 2953–2958. 10.1039/C8DT05113E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamm R. J.; Coles M. P. Catalytic Hydrophosphination of Isocyanates by Molecular Antimony Phosphanides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200064. 10.1002/ejic.202200064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe H. R.; Geer A. M.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Kays D. L. Iron(II)-Catalyzed Hydrophosphination of Isocyanates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4845–4848. 10.1002/anie.201701051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Qu L.; Wang Y.; Yuan D.; Yao Y.; Shen Q. Neutral and Cationic Zirconium Complexes Bearing Multidentate Aminophenolato Ligands for Hydrophosphination Reactions of Alkenes and Heterocumulenes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 139–149. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley Downie T. M.; Hall J. W.; Collier Finn T. P.; Liptrot D. J.; Lowe J. P.; Mahon M. F.; McMullin C. L.; Whittlesey M. K. The first ring-expanded NHC–copper(i) phosphides as catalysts in the highly selective hydrophosphination of isocyanates. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 13359–13362. 10.1039/D0CC05694D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Ma X.; Yan B.; Ni C.; Yu H.; Yang Z.; Roesky H. W. An efficient catalytic method for hydrophosphination of heterocumulenes with diethylzinc as precatalyst without a solvent. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 15488–15492. 10.1039/D1DT02706A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itazaki M.; Matsutani T.; Nochida T.; Moriuchi T.; Nakazawa H. Convenient synthesis of phosphinecarboxamide and phosphinecarbothioamide by hydrophosphination of isocyanates and isothiocyanates. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 443–445. 10.1039/C9CC08329D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkowius U. V.; Nogai S. D.; Schmidbaur H. The Tetra(vinyl)phosphonium Cation [(CH2CH)4P]+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1632–1633. 10.1021/ja0399019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. W.; Harrison K. N.; Hoye P. A. T.; Orpen A. G.; Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B. Water-soluble tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine complexes with nickel, palladium, and platinum. Crystal structure of [Pd{P(CH2OH)3}4]·CH3. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 3026–3033. 10.1021/ic00040a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoye P. A. T.; Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B.; Worboys K. Hydrophosphination of formaldehyde catalysed by tris-(hydroxymethyl)phosphine complexes of platinum, palladium or nickel. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1993, 269–274. 10.1039/dt9930000269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E.; Pringle P. G.; Worboys K. Chemoselective platinum(0)-catalysed hydrophosphination of ethyl acrylate. Chem. Commun. 1998, 49–50. 10.1039/a706718f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B. Platinum(0)-catalysed hydrophosphination of acrylonitrile. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1990, 1701–1702. 10.1039/c39900001701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E.; Pringle P. G.; Smith M. B.; Worboys K. Self-replication of tris(cyanoethyl)phosphine catalysed by platinum group metal complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1997, 4277–4282. 10.1039/a704655c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapshin I. V.; Basalov I. V.; Lyssenko K. A.; Cherkasov A. V.; Trifonov A. A. CaII, YbII and SmII Bis(Amido) Complexes Coordinated by NHC Ligands: Efficient Catalysts for Highly Regio- and Chemoselective Consecutive Hydrophosphinations with PH3. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 459–463. 10.1002/chem.201804549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley Downie T. M.; Mahon M. F.; Lowe J. P.; Bailey R. M.; Liptrot D. J. A Copper(I) Platform for One-Pot P–H Bond Formation and Hydrophosphination of Heterocumulenes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 8214–8219. 10.1021/acscatal.2c02199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geeson M. B.; Tanaka K.; Taakili R.; Benhida R.; Cummins C. C. Photochemical Alkene Hydrophosphination with Bis(trichlorosilyl)phosphine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14452–14457. 10.1021/jacs.2c05248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moglie Y.; González-Soria M. J.; Martín-García I.; Radivoy G.; Alonso F. Catalyst- and solvent-free hydrophosphination and multicomponent hydrothiophosphination of alkenes and alkynes. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4896–4907. 10.1039/C6GC00903D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem A. M.; Hodali H. A. Syntheses, characterization and reactions of some methyl derivatives of platinum(II). Part I. Inorg. Chim. Act. 1990, 174, 223–229. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)80304-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abele A.; Wursche R.; Klinga M.; Rieger B. Dicationic ruthenium(II) complexes containing bridged η1:η6-phosphinoarene ligands for the ring-opening metathesis polymerization. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2000, 160, 23–33. 10.1016/S1381-1169(00)00229-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa-Vizzini K.; Guzman-Jimenez I. Y.; Whitmire K. H.; Lee T. R. Synthesis, Characterization, and Thermal Stability of (η6:η1-C6H5CH2CH2PR2)Ru(CH3)2 (R = Cy, Ph, Et). Organometallics 2003, 22, 3059–3065. 10.1021/om0300070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. A.; Nile T. A.; Mahon M. F.; Webster R. L. Iron catalysed Negishi cross-coupling using simple ethyl-monophosphines. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12189–95. 10.1039/C5DT00112A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone J. P.; Mawhinney R. C.; Spivak G. J. An examination of the effects of borate group proximity on phosphine donor power in anionic (phosphino)tetraphenylborate ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 776, 153–156. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2014.10.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bookham J. L.; McFarlane W.; Thornton-Pett M.; Jones S. Stereoselective addition reactions of diphenylphosphine: meso- and rac-1,2-diphenyl-1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane and their Group 6 metal tetracarbonyl complexes. Crystal structures of the molybdenum derivatives. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1990, 3621–3627. 10.1039/dt9900003621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itazaki M.; Katsube S.; Kamitani M.; Nakazawa H. Synthesis of vinylphosphines and unsymmetric diphosphines: iron-catalyzed selective hydrophosphination reaction of alkynes and vinylphosphines with secondary phosphines. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3163–3166. 10.1039/C5CC10185A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungabong M. L.; Tan K. W.; Li Y.; Selvaratnam S. V.; Dongol K. G.; Leung P.-H. A Novel Asymmetric Hydroarsination Reaction Promoted by a Chiral Organopalladium Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 4733–4736. 10.1021/ic0701561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay W. S.; Yang X. Y.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P. H. Nickel catalyzed enantioselective hydroarsination of nitrostyrene. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6307–6310. 10.1039/C7CC02044A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay W. S.; Lu Y.; Yang X.-Y.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P.-H. Catalytic and Mechanistic Developments of the Nickel(II) Pincer Complex-Catalyzed Hydroarsination Reaction. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11308–11317. 10.1002/chem.201902138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay W. S.; Li Y.; Yang X.-Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P.-H. Air-stable phosphine organocatalysts for the hydroarsination reaction. J. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 914, 121216. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2020.121216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tay W. S.; Yang X. Y.; Li Y.; Pullarkat S. A.; Leung P. H. Investigating palladium pincer complexes in catalytic asymmetric hydrophosphination and hydroarsination. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 4602–4610. 10.1039/C9DT00221A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roering A. J.; Davidson J. J.; MacMillan S. N.; Tanski J. M.; Waterman R. Mechanistic variety in zirconium-catalyzed bond-forming reaction of arsines. Dalton Trans. 2008, 4488–4498. 10.1039/b718050k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesmeyanov A. N.; Borisov A. E.; Novikova N. V. Organometallic derivatives of ethylene. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. 1965, 14, 749–749. 10.1007/BF00846755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan J. W. M.; Marczenko K. M.; Johnson E. R.; Chitnis S. S. Hydrostibination of Alkynes: A Radical Mechanism. Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26, 17134–17142. 10.1002/chem.202003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindra D. R.; Casely I. J.; Fieser M. E.; Ziller J. W.; Furche F.; Evans W. J. Insertion of CO2 and COS into Bi-C bonds: reactivity of a bismuth NCN pincer complex of an oxyaryl dianionic ligand, [2,6-(Me2NCH2)2C6H3]Bi(C6H2(t)Bu2O). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7777–87. 10.1021/ja403133f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]