Abstract

Dystonia in cerebral palsy (DCP) is a common, debilitating, but understudied condition. The CP community (people with CP and caregivers) is uniquely equipped to help determine the research questions that best address their needs. We developed a community-driven DCP research agenda using the well-established James Lind Alliance methodology. CP community members, researchers, and clinicians were recruited through multiple advocacy, research, and professional organizations. To ensure shared baseline knowledge, participants watched webinars outlining our current knowledge on DCP prepared by a Steering Group of field experts (cprn.org/research-cp-dystonia-edition). Participants next submitted their remaining uncertainties about DCP. These were vetted by the Steering Group and consolidated to eliminate redundancy to generate a list of unique uncertainties, which were then prioritized by the participants. The top-prioritized uncertainties were aggregated into themes through iterative consensus-building discussions within the Steering Group. 166 webinar viewers generated 67 unique uncertainties. 29 uncertainties (17 generated by community members) were prioritized higher than their randomly matched pairs. These were coalesced into the following top 10 DCP research themes: (1) develop new treatments; (2) assess rehabilitation, psychological, and environmental management approaches; (3) compare effectiveness of current treatments; (4) improve diagnosis and severity assessments; (5) assess the effect of mixed tone (spasticity and dystonia) in outcomes and approaches; (6) assess predictors of treatment responsiveness; (7) identify pathophysiologic mechanisms; (8) characterize the natural history; (9) determine the best treatments for pain; and (10) increase family awareness. This community-driven research agenda reflects the concerns most important to the community, both in perception and in practice. We therefore encourage future DCP research to center around these themes. Furthermore, noting that community members (not clinicians or researchers) generated the majority of top-prioritized uncertainties, our results highlight the important contributions community members can make to research agendas, even beyond DCP.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common childhood motor disability (affecting 2–3/1,000 children) and is the most common cause of childhood dystonia,1,2 a debilitating, under-recognized, and often treatment refractory disorder.3,4 Dystonia is the predominant form of tone in 15% of people with CP, but up to 70% experience some dystonia.2,4 Although dystonia in CP (DCP) is classically associated with acute injuries at term gestation, any cause of CP can yield dystonia.2 Unlike spasticity (the most common hypertonia type in CP), dystonia is characterized by variability and worsens with voluntary movement. Differentiation between dystonia and spasticity is difficult but critical: dystonia responds to distinct treatments and is a relative contraindication for some spasticity treatments (e.g., selective dorsal rhizotomy).5,6 Despite the need for DCP treatment development, dystonia research has largely focused on rare genetic adult-onset dystonias. As a result, the unique needs of people with DCP remain largely uncharacterized and unaddressed.

To identify research questions that directly benefit those with DCP, people with CP and their caregivers should be involved in setting the research agenda. The 2017 NIH “Strategic Plan for Cerebral Palsy Research” called for enhanced communication between patients and researchers to generate and share data.7 The CP Research Network (CPRN), a nonprofit network of community members and clinicians/researchers collaborating to improve CP health outcomes, responded to this statement with the 2018 “Research CP” initiative, which created a community-centered research agenda for CP at large. Input was garnered from across the CP community: people with CP, caregivers, advocates, clinicians, and researchers.8 While that priority list provided a road map for numerous research initiatives, the prioritization process favored research ideas for which the community had the greatest baseline awareness. Consequently, under-recognized CP features, such as DCP, were left out of the top research ideas.

At the request of its community advisory panel of people with CP and caregivers, the CPRN next focused on setting a community-centered research agenda for DCP to prioritize research ideas that could improve the lives of people with DCP. We aimed to build relationships among members of the CP community who share a common goal of advancing DCP research.

To perform this, we used the well-established James Lind Alliance (JLA) methodology for patient partnership priority setting9 to delineate the top 10 research themes for DCP. We recommend these themes as a guide to those interested in the highest impact concerns for people with DCP.

Methods

This project was reviewed by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and considered exempt.

Steering Group and Recruitment

The CPRN convened a “Research CP: Dystonia Edition” Steering Group in 2019 comprising experts in DCP (M.C.K., D.L.F., J.W.M., and B.R.A.) and CP community members (P.G. and M.S.). The CPRN and Steering Group promoted the opportunity to participate in this process through social media, the CPRN community registry (MyCP), the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM), the Child Neurology Society, and the American Academy of Neurology.

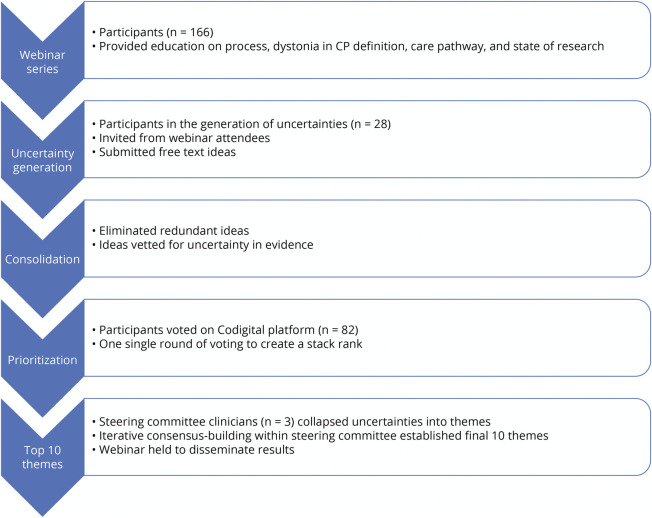

Webinars

The Steering Group produced 3 educational webinars in 2019 discussing current DCP knowledge among all participants. Webinars covered the following: (1) an overview of the study and definition of DCP,10,11 (2) a review of the AACPDM DCP care pathway12 including personal vignettes from the Steering Group CP community members, and (3) a description of existing and ongoing DCP research. These webinars remain publicly viewable.13

Uncertainty Generation

The JLA defines uncertainty using the following principles:9

“…no up-to-date, reliable systematic reviews of research evidence addressing the uncertainty about the effects of treatment exists…” or “…up-to-date systematic reviews of research evidence show that uncertainty exists.”

“…include other health care interventions, including prevention, testing, and rehabilitation.”

Community members, clinicians, and researchers who participated in at least 2 of the 3 webinars were invited to contribute uncertainties for consideration in the research agenda. This inclusion criterion promoted knowledge equity among participants by establishing a shared knowledge base, upholding the James Lind Alliance methodology for Priority Setting Partnerships. Uncertainties were gathered as free-text fields in a web survey with an unlimited number of entries allowed per participant.

Consolidation and Validation of Uncertainties

The Steering Group reviewed uncertainties using the abovementioned criteria and eliminated redundancies.

Prioritization of Uncertainties

The final list of uncertainties was loaded into Codigital, an online collaborative voting tool (Codigital Limited, London, United Kingdom). All participants who viewed at least 2 of the 3 webinars were invited to prioritize uncertainties. Voting participants were presented with pairwise choices of uncertainties and asked to pick which of the 2 uncertainties, if addressed, would have greater effect on people with DCP.

Organization of Uncertainties

On completion of voting, the Steering Group reviewed the 29 uncertainties that received priority votes more than 50% of the time when compared head-to-head with other uncertainties. Three Steering Group clinician members (M.C.K., D.L.F., and B.R.A.) independently grouped each prioritized uncertainty by theme and consolidated and refined these themes through iterative discussion with the full Steering Group to create a final list of the top 10 research themes. The themes were ranked in order of the highest ranked uncertainty that contributed to the theme to preserve the underlying rank order of the uncertainties after voting.

Dissemination

The Steering Group organized a final live webinar to share the results with the community.14 The Figure demonstrates the methodology described earlier.

Figure. Methods Flowchart.

CP = cerebral palsy.

Results

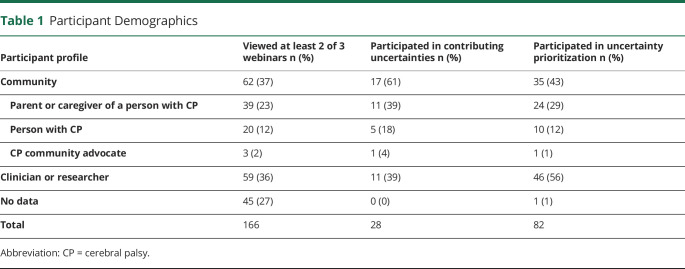

One hundred sixty-six participants viewed at least 2 of the 3 webinars; 28 participated in the generation of uncertainties, and 82 participated in prioritization. Participant demographics are described in Table 1. Seventeen community members and 11 clinicians/researchers generated uncertainties. Of the 82 participants in the voting, 35 were community members, 41 were clinicians, and 5 were researchers. Of the voting community participants (people with CP or parents/caregivers representing them), 14 of the 35 were independently ambulatory (Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] levels I–III), and 21 of the 35 relied on a wheelchair for mobility (GMFCS levels IV–V). The average age of community participants with CP was 44.1 years (95% CI 36.60–51.59), and the average age of people with CP represented by a parent/caregiver was 7.9 years (95% CI 5.87–9.93). Most of the voting clinician participants were neurologists (16/41) or physical therapists (16/41). Other specialties included developmental pediatrics (3/41), physical medicine and rehabilitation (4/41), occupational therapy (1/41), and orthopedic surgery (1/41).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

Initially, 113 uncertainties were proposed, and after consolidation of redundant items, 70 unique uncertainties remained. Of these, only 3 uncertainties were thought by the Steering Group to have already been addressed in the literature, yielding 67 unique uncertainties. Of these, 29 were prioritized above their paired uncertainties more than 50% of the time.

Community members' ideas were well-represented. The top 2 ranked uncertainties were generated by a parent, and 55% of the top-ranked uncertainties were contributed by caregivers, people with CP, or advocates, with the remainder contributed by clinicians (31%) or researchers (14%). The Steering Group subsequently consolidated these top-prioritized uncertainties into 10 research themes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 10 Research Themes for DCP

Discussion

By leveraging community, clinician, and researcher participation, we have identified the top 10 research themes believed to have the greatest effect on people with DCP.

Community engagement in research agenda setting has multiple advantages. First, clinical and translational research should focus on what most helps the community affected by the condition and community members are best equipped to describe their needs. Second, when research questions are prioritized based on importance to the community, community engagement in research may rise. This can increase study recruitment, mobilization of research funding, and greater uptake of new research findings. Finally, it is important to study any condition in the context of the population it is affecting. Because past dystonia research tended to focus on rarer genetic etiologies, inclusion of people with CP and their caregivers when setting a DCP research agenda is critical for prioritizing CP-specific research questions.

Our results support the value of a community-driven research agenda. Most of the top-prioritized uncertainties (55%) were proposed by community members, including the top 2 ranked uncertainties that contributed to the top 2 research themes.

We have summarized the top 10 themes below, exploring the likely rationale behind prioritization of each theme, the current state of the research, and potential next steps. We envision these themes can generate research questions with the highest potential to benefit the DCP community.

Theme 1: Develop New Treatments for Individuals With DCP

Rationale

Currently available treatments for DCP are associated with incomplete dystonia control and often functionally limiting side-effect profiles.5

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

Potential new treatments extend beyond oral medications to neuromodulation15 and improved deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting.16 Community members expressed interest in investigating a possible role for medical marijuana/cannabidiol in treating dystonia.5 Exploratory work also suggests that neural precursor cells may be leveraged to augment innate neural repair mechanisms, which could provide potential disease-modifying options for DCP treatment.17

Potential Next Steps

An improved understanding of the fundamental changes in the brain that cause dystonia (theme 7) may be intimately related to our ability to develop new treatments. Dystonia, regardless of etiology, may have shared common mechanisms or circuit pathophysiology,18,19 which can facilitate the identification of broadly applicable treatment targets. As the genetic causes of CP become more codified, N-of-1 therapies addressing the underlying mechanism of an individual's DCP may become increasingly possible.20

Theme 2: Assess Rehabilitation, Psychological, and Environmental Approaches to Manage Dystonia

Rationale

Noting that dystonia is triggered by heightened arousal (including pain and extreme emotion),11 therapies and environmental interventions reducing stress, pain, and emotional lability could improve dystonia (see also theme 9). Environmental interventions could include ensuring comfortable and supportive seating in the workplace or providing a consistent school aide familiar with the person with CP and their dystonia triggers. Rehabilitation and psychological approaches could include strengthening exercises to reduce pain with weight-bearing and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to develop coping strategies for anxiety triggers.

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

Rehabilitation and psychological approaches have been assessed in CP, but primarily regarding hand and gross motor function.21 Environmental interventions are less well studied. There is a lack of high-quality studies assessing these interventions for DCP.

Potential Next Steps

Prospective randomized controlled trials should assess the effects of these interventions in people with functionally limiting dystonia. N-of-1 studies can also be used to evaluate individualized nonmedical interventions tailored to a person's primary functional concerns.

Theme 3: Compare Effectiveness of Pharmacologic and Surgical Treatments for Dystonia

Rationale

Incremental dystonia severity reduction may not necessarily improve the functional abilities of the person with CP and thus may not justify an extensive side-effect profile. Therefore, comparative effectiveness studies of DCP treatments should take side-effect profiles, overall functional improvements, and quality of life into account.

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

A recent systematic review summarized results from 4 randomized and 42 nonrandomized studies consisting of 915 participants with DCP evaluating pharmacologic and neurosurgical interventions. The evidence favoring any intervention was deemed to be of low or very low certainty.5

Potential Next Steps

Well-designed prospective trials evaluating comparative effectiveness across interventions are needed. These trials should include outcomes focused on dystonia severity, achievement of individualized goals, motor function, pain/comfort, sleep duration and quality, ease of caregiving, quality of life, and adverse events (including emergency care).

Theme 4: Improve the Clinical Consistency of Dystonia Diagnosis and Severity Assessments

Rationale

Dystonia is under-recognized, resulting in inconsistent diagnosis and care.3 Dystonia, by definition, is variable in appearance making its recognition difficult.10 Even expert assessors may disagree on dystonia diagnosis during a single motor task.22

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

There are several rating scale assessments and diagnostic tools available for people with DCP.1,23-28 These rating scales and tools are valuable, but each has limitations, including lengthiness, poor clinical sensitivity, deficient differentiation of dystonia from other dyskinesias or tone patterns, and variable measurements of dystonia characteristics (e.g., amplitude, duration, and severity). Reliable assessments for dystonia are valuable both clinically and as clinical trial outcome measures.

Potential Next Steps

To improve diagnostic consistency, we must address the following barriers: (1) awareness, (2) comprehension, (3) reliability, (4) feasibility, (5) mixed movement disorder differentiation, and (6) identification of what is important to both the clinician and the person directly affected by DCP. Providing greater education on current rating scales and tools may prove beneficial, but new standardized assessments addressing these barriers are also needed. Future directions could, in addition, investigate quantitative video and motion analysis as diagnostic assessments.

Theme 5: Assess the Effect of Mixed Tone (Spasticity and Dystonia) in CP in Outcomes and Approaches

Rationale

More than 70% of people with CP exhibit mixed tone patterns.4 Therefore, addressing dystonia in the context of coexisting spasticity is vital.

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

The Hypertonia Assessment Tool is a validated tool that can be used by both clinicians and researchers to identify mixed tonal patterns of spasticity and dystonia.26 Few studies describe the research subjects' mixed tone patterns or treatment responses. Those that do have not compared the response of patients with mixed tone with the response of patients with either dystonia-only or spasticity-only patterns.29

Potential Next Steps

Moving forward, knowledge implementation research to encourage clinicians and clinical researchers to identify mixed tone patterns will be helpful. Mixed tone patterns commonly coexist with mixed movement patterns. Thus, a new tool to quantify subcomponents of different tone or movement patterns in an individual person is needed. Movement disorder video databases could be mined for this purpose. Intervention research in CP should also include a baseline description of tone patterns in participants and rigorously assess how mixed tone affects response to different therapeutic modalities.

Theme 6: Assess Predictors of Treatment Responsiveness in Individuals With DCP

Rationale

There is some evidence that earlier treatment of dystonia in people with CP may improve outcomes,30 although this needs to be corroborated in prospective studies across treatment options. To treat DCP, it first needs to be recognized by clinicians (theme 4) or brought to their attention by families (theme 10).

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

Dystonia treatment response can be influenced by individual factors,31 concurrent conditions,32 and the quality of the individual's purposeful movement.33 The etiology of dystonia may also be important in determining how an individual with DCP responds to treatment.34

Potential Next Steps

Stratifying people with DCP into those with similar etiologies, brain injury patterns, involved body regions, functional limitations, dystonia patterns, or a combination may help elucidate shared treatment response characteristics. Structural and functional neuroimaging techniques hold promise for identifying features predictive of DCP treatment response and are already being used for decision-making related to DBS.35 Potential blood-based or genetic biomarkers may also ultimately be found to help predict response to treatment.

Theme 7: Identify What Causes DCP

Rationale

Although there is value in identifying the etiology of an individual's dystonia, there is the potential for even greater therapeutic impact if the shared brain pathophysiology that leads to DCP across cohorts of individuals was better understood.

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

Many risk factors for dystonia have been identified, ranging from traumatic brain injury to hypoxia-ischemia to genetic variations, but the final common pathway by which all of these insults lead to dystonia is poorly understood. Previous studies based on anatomic and functional connectivity suggest that changes in both brain circuit connections19 and function36 seem to be involved, although a unifying mechanism has yet to emerge.

Potential Next Steps

A systems neuroscience approach (integrating findings from multiple fields across multiple model systems) could enable the distillation of the essential elements of dystonia down to a causal pathway. Characterization of such a causal pathway could enable parallel advances in theme 1, the development of new therapeutics.

Theme 8: Characterize the Natural History of DCP

Rationale

CP by definition is nonprogressive, but that does not mean that the clinical phenotype is unchanging.37 The evolution of dystonia in people with CP should be characterized to benchmark longitudinal treatment trials and provide prognostication.

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

One retrospective cohort study reported that approximately 60% of families perceived a worsening of dystonia in their children with CP over time with approximately 8% of families perceiving improvement.3 This study focused solely on dystonia in childhood, but most individuals with CP are adults.38 We know that adult patients with DCP are at an increased risk of myelopathy perhaps related to cervical dystonia,38 but it is vital that we learn other risks that affected individuals may face over time.

Potential Next Steps

To characterize the natural history of DCP, we must longitudinally follow-up affected individuals through adulthood. This becomes challenging with the significant decline in surveillance of these individuals once they transition to adult medical care providers. Supporting large longitudinal patient registries and cultivating adult practitioners with a specific interest in DCP to follow-up these individuals long-term can help in establishing the natural history of this population.

Theme 9: Determine the Best Treatments for Pain due to DCP

Rationale

Dystonia was identified as the second most common cause of moderate to severe pain in children with DCP, second to pain from hip subluxation.39 Chronic pain, including pain from dystonia, can induce a neuroplastic response that heightens the individual's sensitivity to pain. This then contributes to a negatively reinforced pain cycle in the individual, further highlighting the importance of finding effective treatments.40

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

People with dystonia often have communication limitations that can make subjective assessments (such as pain) difficult. Even beyond the challenges of assessment, there is limited evidence for effective treatments to reduce pain in DCP.5 A recent systematic review5 found no evidence for pain reduction for many oral medications used to manage DCP. A single retrospective study identified that clonidine may enhance sleep and comfort in seating for individuals with severe generalized dystonia.41 No studies have been completed on medical marijuana and cannabidiol in DCP. Low-certainty evidence for the more invasive dystonia treatments (botulinum toxin A, intrathecal baclofen, and DBS) does support a reduction in pain.5 There are no studies evaluating CBT for chronic pain management in individuals with DCP.

Potential Next Steps

There is clearly a need for controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of medical/psychological and surgical interventions to reduce pain in DCP. Outcome measures in all clinical trials of DCP should include patient-reported pain outcomes.

Theme 10: Increase Awareness of DCP Among Families

Rationale

Underdiagnosis of DCP by medical practitioners can be approached in 2 ways: by improving dystonia recognition by practitioners (theme 4) and by empowering people with CP and their families with an increased knowledge of DCP.

Current State of the Research/Research Gaps

Dystonia diagnosis in people with CP can be delayed by years.3 This delays targeted treatment, which may worsen outcomes.30 A lack of awareness can also prove dangerous if families do not have a medical home or “dystonia action plan” if a movement disorder emergency such as status dystonicus occurs.1

Potential Next Steps

Publicly available webinars on DCP (as prepared for this study) and educational materials that can be handed out in the clinic such as the “CP Toolkit”42 can help increase family awareness of DCP. Future research can focus on the development of dystonia screening questionnaires that can both increase family and practitioner awareness of dystonia in people with CP.

Limitations

Participants were recruited from different organizations and represented the community, researchers, and clinicians. Clinician recruitment entailed 2 neurologic medical associations leading to greater neurologist involvement than other physicians, but there were an equal number of voting neurologists and therapists (39%) representing important allied professionals in the care of individuals with CP. There is likely self-selection bias in this population, which merits future assessment (including education level, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors). In addition, access issues may have limited participation (noting that our webinars and promotional efforts were online).

Half of all participants who viewed the webinar ultimately participated in prioritizing uncertainties. This could be viewed as substantial participant attrition. However, it is possible that there were 2 populations of participants: those committed to developing a research agenda for DCP and those who were only interested in learning more about DCP. To that end, conducting this study may have begun satisfying theme 10 of the ultimate research agenda (to increase awareness of DCP among families).

The webinars led by the expert authors of this study attempted to summarize existing research and views without naming potential research questions. However, we acknowledge that this was not a systematic review and that the webinars likely reflect gaps prioritized by the authors. This may have biased the listeners and therefore biased the generated uncertainties to align with the priorities of the authors. However, it is reassuring that the top uncertainties were generated by the community and not by researchers and clinicians (including the authors of this study).

We have generated a community-driven research agenda outlining the top 10 research themes for DCP. These research themes could have high impact for the CP community and therefore merit consideration by clinicians and researchers. Noting that the top research themes and uncertainties were generated by community members, these results support the involvement of the community in the generation of research ideas, not just in DCP but across the medical field.

Glossary

- AACPDM

American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine

- CBT

cognitive behavioral therapy

- CP

cerebral palsy

- CPRN

CP Research Network

- DBS

deep brain stimulation

- DCP

dystonia in CP

- GMFCS

Gross Motor Function Classification System

- JLA

James Lind Alliance

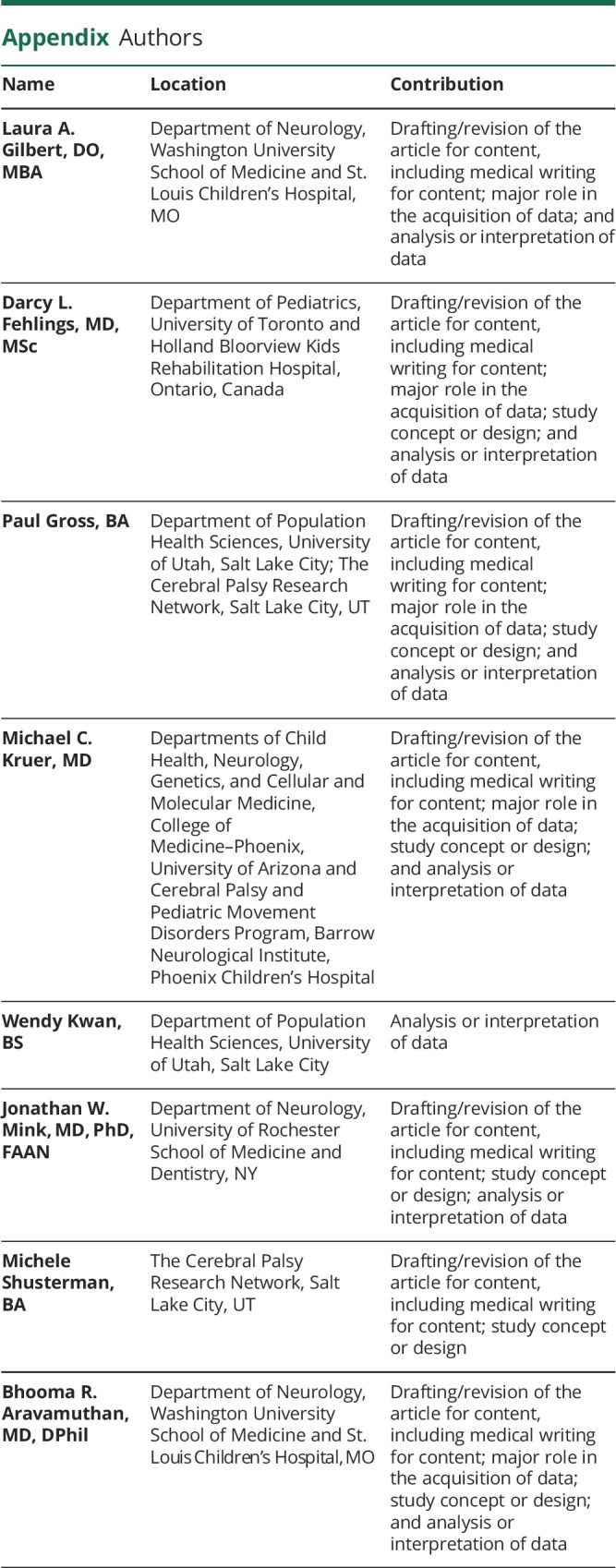

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

P. Gross has received research support from the University of Utah and is a site principal investigator for a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–funded study (5R01NS106298-03). M.C. Kruer serves as a consultant for Aeglea, PTC Therapeutics, CoA Therapeutics, and Merz, reviews grants for the US Department of Defense, and receives grant funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01-NS106298-02). J.W. Mink serves on an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board for a study in “Dyskinetic CP” sponsored by TEVA. B.R. Aravamuthan serves as a consultant for Neurocrine Biosciences and receives grant funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5K12NS098482-02 and 1K08NS117850-01A1). All other authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Monbaliu E, Himmelmann K, Lin JP, et al. Clinical presentation and management of dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(9):741-749. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Himmelmann K. Dyskinetic cerebral palsy: a population-based study of children born between 1991 and 1998. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(12):921-926. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.144014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin JP, Lumsden DE, Gimeno H, Kaminska M. The impact and prognosis for dystonia in childhood including dystonic cerebral palsy: a clinical and demographic tertiary cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(11):1239. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumsden DE, Crowe B, Basu A, et al. Pharmacological management of abnormal tone and movement in cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(8):775-780. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohn E, Goren K, Switzer L, Falck-Ytter Y, Fehlings Y. Pharmacological and neurosurgical interventions for individuals with cerebral palsy and dystonia: a systematic review update and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(9):1038-1050. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas SP, Addison AP, Curry DJ. Surgical tone reduction in cerebral palsy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2020;31(1):91-105. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). NINDS/NICHD Strategic Plan for Cerebral Palsy Research. 2017. Accessed June 9, 2021. ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NINDS_NICHD_2017_StrategicPlanCerebralPalsyResearch_508C.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross PH, Bailes AF, Horn SD, Hurvitz EA, Kean J, Shusterman M. Setting a patient-centered research agenda for cerebral palsy: a participatory action research initiative. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(12):1278-1284. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health Research. The James Lind Alliance Guidebook: Version 10. 2021. Accessed June 9, 2021. jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/downloads/JLA-Guidebook-Version-10-March-2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28(7):863-873. doi: 10.1002/mds.25475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanger TD, Chen D, Fehlings DL, et al. Definition and classification of hyperkinetic movements in childhood. Mov Disord. 2010;25(11):1538-1549. doi: 10.1002/mds.23088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine Dystonia Care Pathway Team. Dystonia in Cerebral Palsy. 2016. Accessed June 9, 2021. aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/dystonia. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerebral Palsy Research Network. Research CP Dystonia Edition. Accessed October 21, 2021. cprn.org/research-cp-dystonia-edition/.

- 14.Cerebral Palsy Research Network. Research CP: Dystonia Edition Results. Accessed October 21, 2021. cprn.org/portfolio-item/mycp-webinar-research-cp-dystonia-edition-results/.

- 15.Latorre A, Rocchi L, Berardelli A, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. The use of transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for movement disorders: a critical review. Mov Disord. 2019;34(6):769-782. doi: 10.1002/mds.27705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanger TD. Deep brain stimulation for cerebral palsy: where are we now? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(1):28-33. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith MJ, Paton MCB, Fahey MC, et al. Neural stem cell treatment for perinatal brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10(12):1621-1636. doi: 10.1002/sctm.21-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Scarduzio M, Ehrlich ME, McMahon LL, Standaert DG. Diverse mechanisms lead to common dysfunction of striatal cholinergic interneurons in distinct genetic mouse models of dystonia. J Neurosci. 2019;39(36):7195-7205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0407-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vo A, Sako W, Niethammer M, et al. Thalamocortical connectivity correlates with phenotypic variability in dystonia. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25(9):3086-3094. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller AR, Brands MMMG, van de Ven PM, et al. Systematic review of N-of-1 studies in rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorders: the power of 1. Neurology. 2021;96(11):529-540. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(2):3. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aravamuthan BR, Ueda K, Miao H, Gilbert L, Smith SE, Pearson TS. Gait features of dystonia in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(6):748-754. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monbaliu E, Ortibus E, de Cat J, et al. The Dyskinesia Impairment Scale: a new instrument to measure dystonia and choreoathetosis in dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(3):278-283. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battini R, Sgandurra G, Menici V, et al. Movement Disorders—Childhood Rating Scale 4–18 revised in children with dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56(3):272-278. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart K, Harvey A, Johnston LM. A systematic review of scales to measure dystonia and choreoathetosis in children with dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(8):786-795. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jethwa A, Mink J, Macarthur C, Knights S, Fehlings T, Fehlings D. Development of the Hypertonia Assessment Tool (HAT): a discriminative tool for hypertonia in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(5):e83-e87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart K, Lewis J, Wallen M, Bear N, Harvey A. The dyskinetic cerebral palsy functional impact scale: development and validation of a new tool. Devel Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(12):1469-1475. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monbaliu E, Ortibus E, Roelens F, et al. Rating scales for dystonia in cerebral palsy: reliability and validity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(6):570-575. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel Ghany WA, Nada M, Mahran MA, et al. Combined anterior and posterior lumbar rhizotomy for treatment of mixed dystonia and spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. Neurosurgery. 2016;79(3):336-344. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lumsden DE, Kaminska M, Gimeno H, et al. Proportion of life lived with dystonia inversely correlates with response to pallidal deep brain stimulation in both primary and secondary childhood dystonia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(6):567-574. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girach A, Vinagre Aragon A, Zis P. Quality of life in idiopathic dystonia: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2019;266(12):2897-2906. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zurowski M, McDonald WM, Fox S, Marsh L. Psychiatric comorbidities in dystonia: emerging concepts. Mov Disord. 2013;28(7):914-920. doi: 10.1002/mds.25501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore RD, Gallea C, Horovitz SG, Hallett M. Individuated finger control in focal hand dystonia: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2012;61(4):823-831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aravamuthan BR, Pearson TS. Treatable movement disorders of infancy and early childhood. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(2):177-191. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okromelidze L, Tsuboi T, Eisinger RS, et al. Functional and structural connectivity patterns associated with clinical outcomes in deep brain stimulation of the globus pallidus internus for generalized dystonia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41(3):508-514. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burciu RG, Hess CW, Coombes SA, et al. Functional activity of the sensorimotor cortex and cerebellum relates to cervical dystonia symptoms. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38(9):4563-4573. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haak P, Lenski M, Hidecker MJC, Li M, Paneth N. Cerebral palsy and aging. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(suppl 4):16-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith SE, Gannotti M, Hurvitz EA, et al. Adults with cerebral palsy require ongoing neurologic care: a systematic review. Ann Neurol. 2021;89(5):860-871. doi: 10.1002/ana.26040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penner M, Xie WY, Binepal N, Switzer L, Fehlings D. Characteristics of pain in children and youth with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e407-e413. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuner R. Central mechanisms of pathological pain. Nat Med. 2010;16(11):1258-1266. doi: 10.1038/nm.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayer C, Lumsden DE, Kaminska M, Lin JP. Clonidine use in the outpatient management of severe secondary dystonia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21(4):621-626. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.CP NOW. The Cerebral Palsy Toolkit: From Diagnosis to Understanding. 2015. Accessed June 9, 2021. cprn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Toolkit-Preview.pdf. [Google Scholar]