Abstract

Background and Objectives

This study investigated the cutaneous small fiber pathology of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) and its clinical significance, that is, the NOTCH3 deposition in cutaneous vasculatures and CNS neurodegeneration focusing on cognitive impairment.

Methods

Thirty-seven patients with CADASIL and 59 age-matched healthy controls were enrolled to evaluate cutaneous small fiber pathology by quantitative measures of intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), sweat gland innervation, and vascular innervation. Cognitive performance of patients with CADASIL was evaluated by a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, and its association with small fiber pathology was tested using multivariable linear regression analysis adjusted for age and diabetes mellitus. We further assessed the relationships of IENFD with cutaneous vascular NOTCH3 ectodomain (NOTCH3ECD) deposition and biomarkers of neurodegeneration including structural brain MRI measures, serum neurofilament light chain (NfL), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), tau, and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1.

Results

Patients with CADASIL showed reduced IENFD (5.22 ± 2.42 vs 7.88 ± 2.89 fibers/mm, p = 0.0001) and reduced sweat gland (p < 0.0001) and vascular (p < 0.0001) innervations compared with age-matched controls. Reduced IENFD was associated with impaired global cognition measured by Mini-Mental State Examination (B = 1.062, 95% CI = 0.370–1.753, p = 0.004), and this association remained after adjustment for age and diabetes mellitus (p = 0.043). In addition, IENFD in patients with CADASIL was associated with mean cortical thickness (Pearson r = 0.565, p = 0.0023) but not white matter hyperintensity volume, total lacune count, or total microbleed count. Reduced IENFD was associated with cutaneous vascular NOTCH3ECD deposition amount among patients harboring pathogenic variants in exon 11 (mainly p.R544C) (B = −0.092, 95% CI = −0.175 to −0.009, p = 0.031). Compared with those with normal cognition, patients with CADASIL with cognitive impairment had an elevated plasma NfL level regardless of concurrent small fiber denervation, whereas only patients with both cognitive impairment and small fiber denervation showed an elevated plasma GFAP level.

Discussion

Cutaneous small fiber pathology correlates with cognitive impairment and CNS neurodegeneration in patients with CADASIL, indicating a peripheral neurodegenerative process related to NOTCH3ECD aggregation.

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is the most common monogenetic cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) that causes early-onset lacunar infarct and vascular dementia.1 CADASIL is caused by variations in the NOTCH3 gene that encodes a large transmembrane protein with restricted expression on smooth muscle cells.2,3 The pathognomonic feature of the CADASIL brain is the deposition of extracellular granular osmiophilic material (GOM) around the vascular smooth muscle cells,4 which is due to the deposition of the NOTCH3 ectodomain (NOTCH3ECD) cleaved from the mutant NOTCH3 receptor.3 NOTCH3ECD depositions are detectable not only in the brain vasculature but also in systemic vessels, including dermal vessels.5 Hence, skin biopsy to demonstrate NOTCH3ECD deposition serves as a surrogate marker before genetic confirmation of pathogenic NOTCH3 variants.6

Although the major clinical manifestations of CADASIL reside in the brain, circumstantial evidence suggests the involvement of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Nerve fiber densities are variably reduced in sural nerve biopsies of CADASIL,7 and intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD) is reduced in skin biopsies of CADASIL.8 However, the studies on this topic were limited, and the results were variable, for example, in relation to nerve conduction studies.9,10 These observations raised intriguing issues of (1) the peripheral innervation in CADASIL and (2) the clinical significance of these changes. IENFD in skin biopsies is an established measure to quantify small fiber pathology,11,12 and it has been applied to demonstrate peripheral nerve involvement in a variety of neurodegenerative disorders.13,14

Cognitive impairment is one of the core clinical features and the major cause of disability for patients with CADASIL. However, the cognitive performance in patients with CADASIL correlated poorly with white matter hyperintensity volume,15,16 which is the imaging hallmark for cerebral SVD. Neuroimaging features of SVD burden may not be satisfactory to reflect the neurodegenerative process in the CNS for CADASIL. Given that vascular pathology is present not only in the cerebrovascular system but also in systemic vessels for CADASIL, it is worth exploring whether there is a degenerative process in the PNS that parallels neurodegeneration in the CNS. We aimed to quantitatively inquire into the extent of small fiber pathology in skin biopsies and further investigate its association with cognitive impairment and NOTCH3ECD deposition associated vasculopathy.

Methods

Study Participants and Clinical Measures

We enrolled patients with genetically confirmed CADASIL and age-matched controls from the Neurology Department of National Taiwan University Hospital between June 21, 2018, and November 11, 2020. The diagnosis of CADASIL was made based on the presence of both (1) clinical and/or imaging evidence of cerebral SVD and (2) pathogenic cysteine-altering NOTCH3 variant. For enrolled patients with CADASIL, we used a structured questionnaire to assess demographic data, risk factors associated with cerebral SVD, and relevant clinical symptoms. Additional details can be found in the eMethods (links.lww.com/WNL/C42).

The small fiber pathology of patients with CADASIL was compared with that of 59 age-matched healthy controls. Controls were recruited by advertisement and screened by an experienced neurologist for the following inclusion criteria: (1) absence of major systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes or other metabolic diseases) and neuropsychiatric disorders according to detailed history taking and neurologic examination performed by an experienced neurologist and (2) exclusion of diseases causing or risk factors for peripheral neuropathies according to relevant laboratory tests including blood chemistry of glucose, metabolic profiles, autoimmune profile, endocrine profile, and kidney function.17

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Taiwan University Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Neuropsychological Evaluation

Patients with CADASIL received a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment performed by experienced neuropsychologists. Global cognitive performance was measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). We used the processing speed index subscale from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition (WAIS-III) to measure processing speed. Working memory index subscales from the WAIS-III, digit span test, and verbal fluency test were used to measure the working memory and executive function of participants. Neuropsychological batteries used for each cognitive domain are summarized in eTable 1 (links.lww.com/WNL/C42). The diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) was based on the 2018 Vascular Impairment of Cognition Classification Consensus Study guidelines.18 Patients with CADASIL were divided into 2 groups based on the neuropsychological assessment: (1) the normal cognition (NC) group and (2) the cognitive impaired (CI) group for patients who had impairment in at least one cognitive domain.

Skin Biopsy and Quantification of Cutaneous Small Fiber Innervation

A 3-mm-diameter skin punch biopsy was taken from the distal leg 10 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. Skin tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and sectioned perpendicular to the dermis with a 50-µm thickness using a sliding microtome. Immunohistochemistry staining for quantification of IENFD was performed following a previously reported protocol.19 In brief, skin sections were quenched in 1% H2O2 in methanol and blocked with 0.5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.5 mol/L Tris buffer. Skin sections were incubated with antisera against the neural marker protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5) (1:1,000; UltraClone, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom) overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour followed by incubation with the avidin-biotin complex (Vector). The reaction product was demonstrated using chromogen SG (Vector). IENFD was quantified according to the established criteria.20 An experienced observer (S.-T.H.) who was blinded to the clinical information counted PGP 9.5-stained nerves in the epidermis at a 40× magnification with a BX40 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The length of the epidermis along the upper margin of the stratum corneum in each skin section was measured with Image-Pro PLUS (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). The IENFD was presented as the number of fibers/mm of epidermal length. The normative values, derived from the fifth percentile values of IENFD in our laboratory, were above 5.88 fibers/mm for those aged less than 60 years and 2.50 fibers/mm for those aged 60 years and older.12

Quantification of sweat gland innervation and vascular innervation was performed by multichannel immunofluorescence staining. Skin sections were immunostained with CD31 for endothelial cells, smooth muscle actin (SMA) for smooth muscle cell of vessels and myoepithelial cells of sweat gland coil, and PGP9.5 for nerve fibers. Images of the skin sections were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope under a 20× objective, and the images were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.52a; NIH, Bethesda, MD).21 Three separate sweat gland coils were sampled for each subject. The same threshold and area selection method (using the Analyze particles command) was applied to all pictures. The sweat gland innervation index (SGII) was defined as the ratio of the PGP9.5-stained nerve area to the SMA-stained sweat gland area (eFigure 1, links.lww.com/WNL/C42). For vascular (arteriole) innervation, images were obtained under a 40× objective. Three innervated arterioles with diameters between 15 and 40 μm were sampled for each subject. The vascular(arteriole) innervation index (VII) was defined as the ratio of the PGP9.5-stained nerve area to the SMA-stained vessel area (eFigure 2). The primary antibodies used were anti-PGP 9.5 (1:1,000; UltraClone), anti-SMA (1:1,000; A5228; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and anti-CD31 (1:500, M0823; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) antibodies. The secondary antibodies used included Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a, and Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG1 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA).

Quantification of Cutaneous Vascular NOTCH3ECD Deposition

To quantify NOTCH3ECD deposition amount on cutaneous arterioles, skin sections were immunostained with anti-NOTCH3ECD antibody (1:100; clone 2G8, MABF937; Millipore, Temecula, CA) and anti-SMA antibody for vessel walls. Images of the arterioles were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope under a 40× objective, and the images were analyzed using ImageJ software. Single optical sections for arterioles with diameters between 15 and 60 μm were obtained for NOTCH3ECD quantification, and at least 10 arteriole sections were sampled for each subject (median of 14 vessels sampled per subject, range 10–20). The NOTCH3ECD index was defined as the ratio of the NOTCH3 ECD-stained area to the SMA-stained vessel area and averaged over the highest 10 arteriole sections for each subject. The same area selection method (using the Analyze particles command) was applied to all pictures.

Peripheral Neurophysiologic Evaluation

Nerve conduction studies (NCSs) and quantitative sensory testing (QST) were performed for patients with CADASIL. The NCS was performed with a Nicolet Viking IV Electromyographer (Madison, WI) following a standardized protocol. Latency, amplitude, and nerve conduction velocity of motor and sensory nerves (including median, ulnar, peroneal, tibial, and sural nerves) and latency of F-wave and H-reflex studies were measured. QST was performed with a Thermal Sensory Analyzer (Medoc, Ramat Yishai, Israel). The warm threshold and cold threshold temperatures at the thenar, index finger, dorsal foot, and toe were measured. The results of NCSs and QST were compared with our normative database of corresponding age and sex.

Brain MRI Acquisition and Quantification of Gray Matter and White Matter Pathology

All patients with CADASIL underwent a brain MRI. The scanning protocols included axial T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR), susceptible-weighted imaging (SWI), and coronal T1-weighted image (T1WI) or a 3D T1WI. For each brain MRI, we calculated the total lacune count and the total microbleed count and quantified white matter lesion volume using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM12; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, University College London, United Kingdom, fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) and mean cortical thickness using FreeSurfer software (version 5.3, surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). Lacune was defined as a round or ovoid fluid-filled (similar signal as CSF) cavity with a diameter of approximately 3–15 mm.22 The number of lacunes in each patient was counted. Cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) were defined as areas of homogeneous round signal loss with a size less than 10 mm in diameter on SWI.22 The distribution and number of CMBs were documented using the Microbleed Anatomical Rating Scale.23 To measure white matter hyperintensity volume, we use the lesion prediction algorithm (Schmidt, 2017, Chapter 6.1) as implemented in the Lesion Segmentation Tool toolbox version 3.0.0 (statistical-modelling.de/lst.html) for SPM to segment white matter lesions from T2-FLAIR images. T1WIs were used as the reference images. To measure gray matter atrophy, the mean cortical thickness was quantified on T1-weighted structural MRI scans using FreeSurfer. The Desikan-Killiany cortical atlas was used for cortical parcellation.24

Plasma Biomarker Measurements for Neurodegeneration

We collected 10 mL of venous blood from all participants on enrollment. Blood samples were centrifuged, and the plasma aliquots were stored at −80°C before biochemical analysis. Quantification of plasma biomarkers including neurofilament light chain (NfL), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), tau, and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1) was performed using the Neurology 4-plex assay kit established by the Simoa platform (Quanterix Corp., Lexington, MA). The analyses were blinded to the clinical information and the diagnosis groups.

Statistical Analysis

We used independent t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables to compare the between-group differences in demographic variables. Analysis of variance was used to compare IENFD between diagnostic groups, and the p value for between-group differences was derived from the Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference test in post hoc analysis. To determine factors that were associated with MMSE, we performed multivariable linear regression analysis using the forward stepwise selection method (p value <0.05 for entry and p value >0.1 for removal). The association between IENFD and individual cognitive and imaging measurements and NOTCH3ECD deposition amount was tested using linear regression models adjusted for age and diabetes mellitus. To adjust for multiple comparisons, we used the false discovery rate (FDR) method.25 Comparisons of the distributions of plasma biomarkers between groups were performed using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Data Availability

Anonymized data will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Clinical Profiles of Participants

The present study recruited 37 patients with genetically confirmed CADASIL. The initial presentations of patients with CADASIL that led to genetic diagnosis were stroke (n = 20), cognitive impairment (n = 3), headache (n = 3), advanced leukoaraiosis (n = 7), and asymptomatic carriers with a positive family history (n = 3). The demographic data of patients with CADASIL are shown in Table 1. Among the enrolled patients with CADASIL, 14 had NC performance, and 23 had CI. Compared with the NC group, patients in the CI group were older (67.0 ± 7.4 vs 54.3 ± 8.4 years, p < 0.0001), had a more advanced cerebral SVD burden, and had thinner mean cortical thickness (2.3605 ± 0.1186 vs 2.4776 ± 0.0670 mm, p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in the incidence of vascular risk factors between the 2 groups, except for a trend toward more frequent diabetes in the CI group (8/23 vs 1/14, p = 0.057).

Table 1.

Demographics, Cognitive Performance, and Imaging Characteristics of Enrolled CADASIL Patients

Cutaneous Small Fiber Denervation in CADASIL

Small fiber pathology of patients with CADASIL was compared with that of 59 age-matched controls (age 60.1 ± 9.3 years, 53% male), with the results shown in Figure 1. Pathology signs of nerve degeneration, including reduced epidermal innervation, swelling of the varicosity in the IENF, and reduced abundance of the subepidermal nerve plexus were observed in skin sections of patients with CADASIL (Figure 1B). The frequency of pathologic IENFD below the normative values was 5/14 (36%), 8/23 (34%), and 7/59 (12%) among patients with CADASIL with NC, patients with CADASIL with CI, and controls, respectively. Quantitatively, patients with CADASIL showed reduced IENFD compared with controls (5.22 ± 2.42 vs 7.88 ± 2.89 fibers/mm, p < 0.0001; Figure 1C). We used a linear regression model to estimate the effect of age on IENFD. Similar to controls, IENFD was reduced with age among patients with CADASIL (r2 = 0.392, p < 0.0001). The slope of IENFD decline for age did not differ significantly between patients with CADASIL and controls (slope estimate = −0.154 vs −0.088, p = 0.231). In addition to sensory denervation, patients with CADASIL showed significantly reduced innervation both on sweat glands (SGII 0.161 ± 0.100 vs 0.357 ± 0.121, p < 0.0001) and on dermal arterioles (VII 0.148 ± 0.054 vs 0.244 ± 0.070, p < 0.0001) compared with controls (eFigure 3, links.lww.com/WNL/C42).

Figure 1. Reduced IENFs in Patients With CADASIL.

Skin sections from controls and patients with CADASIL were immunohistochemically stained with protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5), a neuronal protein labeling all nerve fibers for quantification of the IENFs density. (A) In this representative section from a control, IENFs (arrows) in the epidermis (epi) had typical varicose appearances arising from the subepidermal nerve plexus (snp) which was located in the dermis (derm). (B) The innervation of the epidermis in patients with CADASIL was reduced and fragmented (arrow), with prominent swelling of the varicosity (arrowhead). (C) IENFD was significantly lower in patients with CADASIL (5.22 ± 2.42 fibers/mm) compared with age-matched controls (7.88 ± 2.89 fibers/mm). IENF = intraepidermal nerve fiber; IENFD = IENF density.

Fifteen (41%) of the enrolled patients with CADASIL had focal neuropathy during NCSs. The most frequent neurophysiologic diagnoses were median entrapment neuropathy (n = 8) and lumbosacral radiculopathy (n = 8). None of them presented sensorimotor polyneuropathy. QST was performed for 34 patients with CADASIL. Abnormal QST was found in 20 (59%) patients, including 14 (41%) with an increased warm threshold, 10 (29%) with an increased vibratory threshold, and 1 with a reduced cold threshold. The warm threshold on the index finger (Pearson r = −0.4573, p = 0.049) and vibratory threshold (Pearson r = −0.4497, p = 0.049) on the lateral malleolus were associated with a lower IENFD (eTable 2, links.lww.com/WNL/C42).

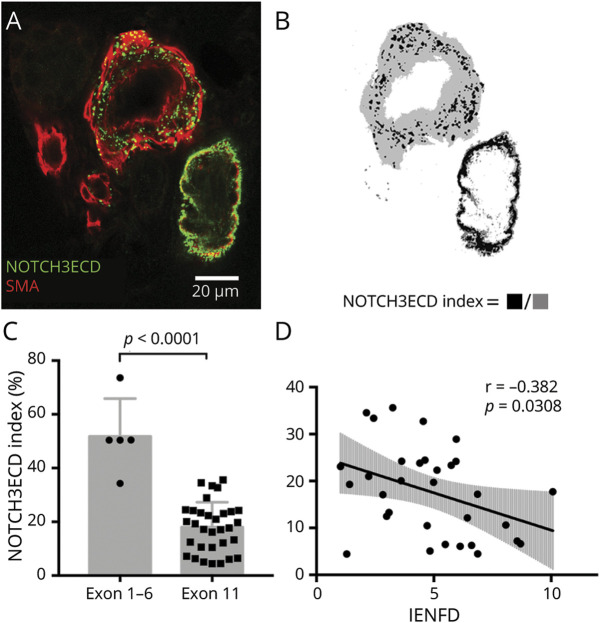

Small Fiber Pathology Correlates With Vascular NOTCH3ECD Deposition

To explore the mechanism underlying small fiber degeneration in CADASIL, we assessed the relationship of IENFD with cutaneous vascular NOTCH3ECD deposition quantified from immunofluorescence staining of NOTCH3ECD on skin sections. The NOTCH3ECD deposition index, defined as the ratio of the NOTCH3ECD-stained area to the SMA-stained vessel area (Figure 2, A and B), was much higher for patients with CADASIL harboring NOTCH3 variants located in exon 1 to exon 6, compared with those harboring NOTCH3 variants located in exon 11 (mainly the p.R544C variant) (Figure 2C). Given (1) the difference in NOTCH3ECD deposition between genotypes and (2) the majority of patients in our cohort having pathogenic NOTCH3 variants in exon 11, only the subgroup of patients harboring variants in exon 11 was analyzed (n = 32). Reduced IENFD was associated with a higher NOTCH3ECD index (B = −0.092, 95% CI = −0.175 to −0.009, p = 0.03) among patients with CADASIL harboring NOTCH3 variants in exon 11 (Figure 2D), and this association remained significant after adjustment for age and concurrent diabetes mellitus (B = −0.106, 95% CI = −0.173 to −0.039, p = 0.0032). The association between NOTCH3ECD and IENFD for pathogenic variants located in exons 1–6 was not statistically assessed because of its small sample size.

Figure 2. Skin NOTCH3 Ectodomain (NOTCH3ECD) Depositions and Its Association With Small Fiber Pathology in Patients With CADASIL.

(A) To quantify vascular NOTCH3ECD deposition amount, skin sections were immunostained with anti-NOTCH3ECD antibody (green) and anti-smooth muscle actin (SMA, red) to define the vessel wall area. Punctate aggregates of NOTCH3ECD depositions on cross-sections of skin vessels were shown on the representative skin section of a patient with CADASIL. (B) The extent of NOTCH3ECD deposition on vessels was measured by the NOTCH3ECD index, defined as the ratio of the NOTCH3ECD-stained area (black) to the SMA-stained vessel area (gray). (C) The NOTCH3ECD index was much higher for patients harboring pathogenic NOTCH3 variants located in exons 1–6, compared with variants in exon 11. (D) In the subgroup of patients harboring NOTCH3 variants located in exon 11 (n = 32), IENFD was associated with a lower NOTCH3ECD deposition index (p = 0.0308). IENFD = intraepidermal nerve fiber density; NOTCH3ECD = NOTCH3 ectodomain; r = correlation coefficient; SMA = smooth muscle actin.

Clinical Significance of Skin Innervation: Correlation With Cognitive Impairment in CADASIL

Patients with CADASIL in the CI group had significantly reduced IENFD compared with the NC group (4.35 ± 2.30 vs 6.65 ± 1.92 fibers/mm, p = 0.0031; Figure 3A). IENFD did not differ significantly between patients with CADASIL in the NC group and controls (6.65 ± 1.92 vs 7.88 ± 2.89 fibers/mm, p = 0.257). Unlike IENFD, sweat gland and vascular(arteriole) innervation did not differ between patients with CADASIL with CI and patients with NC. To identify clinical predictors for global cognitive performance of patients with CADASIL, we performed linear regression analysis (eTable 3, links.lww.com/WNL/C42). In the univariate analysis, IENFD was the only clinical predictor that was significantly correlated with MMSE (B = 1.062, 95% CI = 0.370–1.753, p = 0.004, Figure 3B). There were trends toward an association between age and a lower MMSE (B = −0.176, p = 0.065) and toward an association between education level and MMSE (B = 3.829, p = 0.079). In the multiple regression model constructed using the stepwise selection method, IENFD remained the only statistically significant predictor for MMSE. Considering the potential confounding effect of age and concurrent diabetes mellitus, we constructed a second multiple regression model that adjusted for age and diabetes mellitus. In this model, IENFD remained associated with MMSE (B = 0.691, 95% CI = 0.025–1.356, p = 0.043).

Figure 3. Association Between IENFD and Cognitive Performance in Patients With CADASIL.

(A) Reduced IENFD was associated with cognitive impairment in patients with CADASIL. Patients with CADASIL who had cognitive impairment (CI group, IENFD = 4.35 ± 2.30 fibers/mm) had significantly reduced IENFD compared with patients with CADASIL with normal cognition (NC group, IENFD = 6.65 ± 1.92 fibers/mm). IENFD was correlated with global cognitive performance (measured by Mini-Mental State Examination, B), executive function (measured by the verbal fluency test, C), and processing speed (measured by the processing speed index, D). CI = cognitive impaired; IENFD = intraepidermal nerve fiber density; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NC = normal cognition; r = correlation coefficient.

Given that executive dysfunction and processing speed were impaired at an early stage in patients with CADASIL,26,27 we also tested the association of IENFD with executive function and processing speed measurements. IENFD was associated with verbal fluency (Pearson r = 0.572, FDR-adjusted p = 0.001; Figure 3C), processing speed index (Pearson r = 0.404, FDR-adjusted p = 0.014; Figure 3D), forward digit span (Pearson r = 0.499, FDR-adjusted p = 0.004), and backward digit span (Pearson r = 0.396, FDR-adjusted p = 0.014). The association between IENFD and working memory index was not statistically significant (FDR-adjusted p = 0.235). Because diabetes is a well-established risk factor for small fiber neuropathy,28 we performed a subgroup analysis that includes only those patients with CADASIL without diabetes mellitus (n = 28). The subgroup analysis showed the same pattern of IENFD and clinical association with vascular cognitive impairment as in the total patients with CADASIL (eFigures 4 and 5, links.lww.com/WNL/C42).

Clinical Significance of Skin Innervation: Associations With Neuroimaging Characteristics

To further explore the clinical significance of skin innervation, we tested the association of IENFD with imaging characteristics in patients with CADASIL (Figure 4). Reduced IENFD was significantly associated with thinner mean cortical thickness (Pearson r = 0.565, FDR-adjusted p = 0.003; Figure 4A). There was no statistically significant association between IENFD and cerebral SVD burden, including white matter hyperintensity volume (Pearson r = −0.230, FDR-adjusted p = 0.203; Figure 4B), total lacune count (Pearson r = −0.230, FDR-adjusted p = 0.214; Figure 4C), and total cerebral microbleed count (Pearson r = −0.270, FDR-adjusted p = 0.203; Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Association Between IENFD and Neuroimaging Hallmarks of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden in Patients With CADASIL.

Reduced IENFD was significantly associated with gray matter atrophy (A). There was no statistically significant association between IENFD and cerebral small vessel disease burden, including white matter lesion (WML) volume (B), total lacune count (C), and total cerebral microbleed count (D). CMB = cerebral microbleed; IENFD = intraepidermal nerve fiber density; r = correlation coefficient; WML = white matter lesion.

Small Fiber Pathology Correlates With Plasma Neurodegeneration Biomarkers

Plasma levels of NfL, GFAP, tau, and UCHL1 were measured and compared among patients with CADASIL grouped according to their cognitive performance and skin INEFD as follows: (1) the NC group; (2) the CI–normal innervation (CI-NI) group, defined as patients in the CI group and with IENFD above the median; and (3) the CI–skin denervation (CI-SD) group, defined as patients in the CI group and with IENFD below the median. Figure 5 summarizes the results of the plasma biomarker levels among the different groups. Both the CI-SD and CI-NI groups showed significantly elevated plasma NfL levels compared with the NC group (NfL = 72.10 ± 89.71, 21.61 ± 11.74, and 7.77 ± 4.35 pg/mL for CI-SD, CI-NI, and NC groups, separately; p = 0.0005 for CI-SD vs NC; p = 0.0033 for CI-NI vs NC). Only the CI-SD group showed elevated plasma GFAP levels compared with the NC group (GFAP = 222.5 ± 288.4 vs 94.7 ± 43.4 pg/mL, p = 0.0143). To limit the possible bias caused by one outliner (GFAP = 1,081.464 pg/mL) in the CI-SD group, we also analyzed the differences of distributions of GFAP between groups after exclusion of the outliner. The difference of GFAP levels between the CI-SD group and the NC group remained significant after exclusion of the outliner in the CI-SD group (p = 0.0298). There were no significant differences in either the plasma UCHL1 or the tau levels among the 3 groups.

Figure 5. Plasma Biomarkers in Relation to Cognitive Performance and Small Fiber Involvement in Patients With CADASIL.

Plasma biomarker levels were compared between patients with CADASIL stratified according to their cognitive performance and small fiber involvement: (A) The plasma NfL level was elevated in the CI-SD and the CI-NI groups compared with the NC group. (B) The plasma GFAP level was elevated in the CI-SD group compared with the NC group. (C) There was no significant difference in the plasma UCHL1 levels between the 3 groups. (D) There was no significant difference in the plasma tau levels between the 3 groups. CI-NI = cognitive impaired–normal innervation; CI-SD = cognitive impaired–skin denervation; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; NC = normal cognition; ns = nonsignificant; NfL = neurofilament light chain; UCHL1 = ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate a robust association between cutaneous small fiber denervation and vascular cognitive impairment, one of the core manifestations in CADASIL. Moreover, small fiber pathology was associated with vascular NOTCH3ECD deposition. Small fiber pathology in CADASIL was evident on multiple quantitative measurements of skin biopsies, including epidermal innervation measured with IENFD, sweat gland innervation, and vascular innervation. Reduced IENFD was inversely correlated with age among patients with CADASIL, suggesting that an age-dependent degenerative process underlies small fiber pathology in CADASIL. Consistent with this finding, age is one of the most important factors that predicts cerebral SVD severity and clinical severity for patients with CADASIL.29 Although NOTCH3ECD depositions on skin vessels were known to be the pathognomonic feature on skin biopsy of patients with CADASIL, its clinical significance remained unclear given that vascular NOTCH3ECD deposition load was associated with NOTCH3 variant positions.30 In this study, NOTCH3ECD deposition amount was much higher in patients harboring NOTCH3 variants located in exon 1 to exon 6 compared with those harboring NOTCH3 variants located in exon 11. This observation raised an issue of different genotype on NOTCH3ECD deposition and significance. Thus, the correlation between small fiber pathology and NOTCH3ECD deposition may need to be assessed separately for patients with different NOTCH3 variants. We demonstrated that the extent of NOTCH3ECD deposition amount was associated with reduced IENFD in the subgroup of patients harboring pathogenic NOTCH3 variants in exon 11 (mainly p.R544C). For patients who had other NOTCH3 variants, we were unable to assess the association statistically because of the small sample size. The observed association between small fiber pathology and NOTCH3ECD deposition supports the hypothesis of a pathogenic role of the NOTCH3ECD aggregates.31

The association between small fiber pathology and the CNS neurodegeneration was substantiated by multiple lines of evidence, including neuropsychological measurements and structural MRI changes. Of interest, reduced IENFD was associated with cortical thinning but not imaging markers of cerebral SVD burden. Although previous imaging studies have shown that cognitive impairment in CADASIL is associated with lacunar infarct load32,33 and cerebral microbleed,33,34 these studies failed to demonstrate an association between cognitive performance and white matter hyperintensity volume, the hallmark of cerebral SVD. Global gray matter atrophy, which may represent the final consequence of neurodegeneration, correlates better with cognitive impairment or disability.15,16 Extending these findings, this study demonstrated that IENFD correlated better with cortical thinning, but not cerebral SVD burden. Although vasculopathy may be the initiator of neurodegeneration, other genetic and environmental factors potentially modify the final degenerative process and contribute to the large phenotype variability among patients with CADASIL.1

Although small fiber pathology was evident according to histopathologic evidence, large fiber involvement was questionable. In our cohort, 41% of the patients with CADASIL had focal neuropathy, whereas none of the patients had polyneuropathy on NCSs. Another cohort that included 43 patients with CADASIL showed that only 7 patients had abnormal NCS.10 Different fiber types may have differential vulnerability to chronic ischemia. For example, in a rat model of induced partial nerve infarction, small unmyelinated fibers are more vulnerable to ischemia than larger fibers.35

Plasma biomarker analysis further supported parallel CNS and PNS degeneration in CADASIL. Although plasma NfL was elevated in patients with CADASIL who had cognitive impairment regardless of small fiber involvement, GFAP was elevated only in patients with CADASIL with both cognitive impairment and evident small fiber involvement. NfL is a subunit of neurofilaments, and its concentration in the blood is elevated in response to axonal injuries in either the CNS36 or the PNS.37-40 In CADASIL, NfL has been found to be associated with brain MRI lesion load, cognitive impairment,41 and incident stroke.42 On the other hand, a few studies have reported elevated plasma NfL in response to hereditary37,39 and acquired peripheral neuropathies.38 Elevated plasma NfL in the present CADASIL cohort may reflect the combined effect of injuries involving both the CNS and the PNS, and hence, the individual contribution of the PNS and CNS on the elevation of NfL cannot be discriminated. GFAP is the main intermediate filament protein in astrocytes.43 Elevation of GFAP has been observed in CNS diseases including Alzheimer disease,44 multiple sclerosis,45 and hemorrhagic stroke.46 In the present CADASIL cohort, GFAP was elevated only in patients who had cognitive impairment and lower IENFD, which may reflect more advanced central degeneration in this group of patients.

The present study also had some limitations. First, whether small fiber pathology represents a primary degenerative process associated with pathogenic NOTCH3ECD aggregates or was it secondary to systemic vasculopathy remained unanswered. Although the exact mechanisms leading to vasculopathy in CADASIL remain unclear, a toxic gain of function of the mutant NOTCH3ECD that dysregulates extracellular matrix proteins has been proposed.47,48 Dysregulated extracellular matrix proteins may contribute not only to vasculopathy but also to small fiber degeneration. Recent studies using corneal confocal microscopy have demonstrated associations between corneal fiber denervation and white matter hyperintensity and the risk of recurrence in patients with ischemic stroke.49,50 Although healthy controls were included in the present study, this study did not include disease controls consisting of another type of cerebrovascular disease, such as sporadic cerebral SVD. To elucidate the role of vasculopathy in small fiber neuropathy, future studies that include diseased controls of other types of cerebrovascular disease are needed. Second, cognitive performance and small fiber pathology were cross-sectionally evaluated in the present study. Further longitudinal studies that sequentially assess the progression of small fiber pathology and its association with cognitive changes will help clarify the relationship between small fiber pathology and the central degenerative process in CADASIL. Third, the clinical consequence of small fiber pathology in patients with CADASIL was not assessed in the present study. In clinical practice, patients with CADASIL rarely report significant positive sensory symptoms associated with small fiber neuropathy. However, negative symptoms, such as impaired sensitivity to thermal and noxious stimuli, can easily be masked by parallel cognitive and cerebrovascular disease burden and thus overlooked in the clinical setting. The functional consequence of small fiber denervation in patients with CADASIL should be implemented in future systemic investigations. Finally, this study mainly focused on NOTCH3 p.R544C, the most frequent genotype in Taiwanese patients with CADASIL. It would be important to test such pathology and clinical significance in other genotypes systematically.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a strong association between peripheral small fiber pathology and vascular cognitive impairment among patients with CADASIL. Small fiber pathology may represent a PNS degenerative process related to NOTCH3ECD aggregation.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the participants in the study. They also thank the staff of the imaging core at the First Core Labs, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, for technical assistance in imaging optimization for small fiber pathology quantification.

Glossary

- CADASIL

cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

- CI

cognitive impaired

- CI-NI

CI–normal innervation

- CI-SD

CI–skin denervation

- CMB

cerebral microbleed

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GOM

granular osmiophilic material

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- IENFD

intraepidermal nerve fiber density

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NC

normal cognition

- NCS

nerve conduction study

- NfL

neurofilament light chain

- NOTCH3ECD

NOTCH3 ectodomain

- PNS

peripheral nervous system

- QST

quantitative sensory testing

- SGII

sweat gland innervation index

- SMA

smooth muscle actin

- SVD

small vessel disease

- SWI

susceptible-weighted imaging

- T1WI

T1-weighted image

- T2-FLAIR

T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- UCHL1

ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1

- VCI

vascular cognitive impairment

- VII

vascular(arteriole) innervation index

- WAIS-III

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (107-2320-B-002-043-MY3 and 109-2320-B-002-025), the Ministry of Education, Taiwan (107L9014-2), National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan (UN110-014), and National Taiwan University Hospital, Hsin-Chu Branch, Taiwan (108-HCH025, 109-HCH033).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Di Donato I, Bianchi S, De Stefano N, et al. Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) as a model of small vessel disease: update on clinical, diagnostic, and management aspects. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0778-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, et al. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature. 1996;383(6602):707-710. doi: 10.1038/383707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joutel A, Andreux F, Gaulis S, et al. The ectodomain of the Notch3 receptor accumulates within the cerebrovasculature of CADASIL patients. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(5):597-605. doi: 10.1172/jci8047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baudrimont M, Dubas F, Joutel A, et al. Autosomal dominant leukoencephalopathy and subcortical ischemic stroke. A clinicopathological study. Stroke. 1993;24(1):122-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joutel A, Favrole P, Labauge P, et al. Skin biopsy immunostaining with a Notch3 monoclonal antibody for CADASIL diagnosis. Lancet. 2001;358(9298):2049-2051. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)07142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tikka S, Mykkanen K, Ruchoux MM, et al. Congruence between NOTCH3 mutations and GOM in 131 CADASIL patients. Brain. 2009;132(pt 4):933-939. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroder JM, Zuchner S, Dichgans M, et al. Peripheral nerve and skeletal muscle involvement in CADASIL. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110(6):587-599. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolano M, Provitera V, Donadio V, et al. Cutaneous sensory and autonomic denervation in CADASIL. Neurology. 2016;86(11):1039-1044. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sicurelli F, Dotti MT, De Stefano N, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in CADASIL. J Neurol. 2005;252(10):1206-1209. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang SY, Oh JH, Kang JH, et al. Nerve conduction studies in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2009;256(10):1724-1727. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polydefkis M, Hauer P, Sheth S, et al. The time course of epidermal nerve fibre regeneration: studies in normal controls and in people with diabetes, with and without neuropathy. Brain. 2004;127(pt 7):1606-1615. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shun CT, Chang YC, Wu HP, et al. Skin denervation in type 2 diabetes: correlations with diabetic duration and functional impairments. Brain. 2004;127(pt 7):1593-1605. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Üçeyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain. 2013;136(pt 6):1857-1867. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atherton DD, Facer P, Roberts KM, et al. Use of the novel contact heat evoked potential stimulator (CHEPS) for the assessment of small fibre neuropathy: correlations with skin flare responses and intra-epidermal nerve fibre counts. BMC Neurol. 2007;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viswanathan A, Godin O, Jouvent E, et al. Impact of MRI markers in subcortical vascular dementia: a multi-modal analysis in CADASIL. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(9):1629-1636. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Sullivan M, Ngo E, Viswanathan A, et al. Hippocampal volume is an independent predictor of cognitive performance in CADASIL. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(6):890-897. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao CC, Tseng MT, Lin YJ, et al. Pathophysiology of neuropathic pain in type 2 diabetes: skin denervation and contact heat-evoked potentials. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2654-2659. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skrobot OA, Black SE, Chen C, et al. Progress toward standardized diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment: guidelines from the Vascular Impairment of Cognition Classification Consensus Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):280-292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chien HF, Tseng TJ, Lin WM, et al. Quantitative pathology of cutaneous nerve terminal degeneration in the human skin. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102(5):455-461. doi: 10.1007/s004010100397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh ST, Chiang HY, Lin WM. Pathology of nerve terminal degeneration in the skin. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(4):297-307. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671-675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822-838. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregoire SM, Chaudhary UJ, Brown MM, et al. The Microbleed Anatomical Rating Scale (MARS): reliability of a tool to map brain microbleeds. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1759-1766. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968-980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, et al. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125(1-2):279-284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buffon F, Porcher R, Hernandez K, et al. Cognitive profile in CADASIL. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):175-180. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.068726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dichgans M. Cognition in CADASIL. Stroke. 2009;40(3 suppl):S45-S47. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oaklander AL, Nolano M. Scientific advances in and clinical approaches to small-fiber polyneuropathy: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10):1240-1251. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, et al. CADASIL. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):643-653. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gravesteijn G, Hack RJ, Mulder AA, et al. NOTCH3 variant position is associated with NOTCH3 aggregation load in CADASIL vasculature. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2022;48(1):e12751. doi: 10.1111/nan.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joutel A. The NOTCH3ECDcascade hypothesis of cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy disease. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2015;3(1):1-6. doi: 10.1111/ncn3.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liem MK, van der Grond J, Haan J, et al. Lacunar infarcts are the main correlate with cognitive dysfunction in CADASIL. Stroke. 2007;38(3):923-928. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257968.24015.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akoudad S, Wolters FJ, Viswanathan A, et al. Association of cerebral microbleeds with cognitive decline and dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(8):934-943. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nannucci S, Rinnoci V, Pracucci G, et al. Location, number and factors associated with cerebral microbleeds in an Italian-British cohort of CADASIL patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parry GJ, Brown MJ. Selective fiber vulnerability in acute ischemic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(2):147-154. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(8):870-881. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ticau S, Sridharan GV, Tsour S, et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Neurology. 2021;96(3):e412-e422. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayashi T, Nukui T, Piao JL, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Brain Behav. 2021;11(5):e02084. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandelius A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain concentration in the inherited peripheral neuropathies. Neurology. 2018;90(6):e518-e524. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mariotto S, Farinazzo A, Magliozzi R, et al. Serum and cerebrospinal neurofilament light chain levels in patients with acquired peripheral neuropathies. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2018;23(3):174-177. doi: 10.1111/jns.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gravesteijn G, Rutten JW, Verberk IMW, et al. Serum neurofilament light correlates with CADASIL disease severity and survival. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(1):46-56. doi: 10.1002/acn3.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen CH, Cheng YW, Chen YF, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain and glial fibrillary acidic protein predict stroke in CADASIL. J Neuroinflamm. 2020;17(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01813-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hol EM, Pekny M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the astrocyte intermediate filament system in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;32:121-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elahi FM, Casaletto KB, La Joie R, et al. Plasma biomarkers of astrocytic and neuronal dysfunction in early- and late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(4):681-695. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Axelsson M, Malmestrom C, Nilsson S, et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: a potential biomarker for progression in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2011;258(5):882-888. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katsanos AH, Makris K, Stefani D, et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein in the differential diagnosis of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2017;48(9):2586-2588. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan R, Traylor M, Rutten-Jacobs L, et al. New insights into mechanisms of small vessel disease stroke from genetics. Clin Sci. 2017;131(7):515-531. doi: 10.1042/cs20160825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zellner A, Scharrer E, Arzberger T, et al. CADASIL brain vessels show a HTRA1 loss-of-function profile. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(1):111-125. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1853-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamran S, Khan A, Salam A, et al. Cornea: a window to white matter changes in stroke; corneal confocal microscopy a surrogate marker for the presence and severity of white matter hyperintensities in ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(3):104543. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khan A, Akhtar N, Kamran S, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy identifies greater corneal nerve damage in patients with a recurrent compared to first ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.