Abstract

Introduction

The treatment of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma needs accurate risk stratification, in order to choose the most suitable therapy. The prognostic significance of resection margin is still highly debated, considering the contradictory results obtained in several studies regarding the survival rate of patients with a positive resection margin.

Objective

To evaluate the prognostic role of resection margin in terms of survival and risk of recurrence of primary tumour through survival analysis.

Methods

Between 2007 and 2014, 139 patients affected by laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma underwent partial or total laryngectomy and were followed for mean of 59.44 ± 28.65 months. Resection margin status and other variables such as sex, age, tumour grading, pT, pN, surgical technique adopted, and post-operative radio- and/or chemotherapy were investigated as prognostic factors.

Results

45.32% of patients underwent total laryngectomy, while the remaining subjects in the cohort underwent partial laryngectomy. Resection margins in 73.39% of samples were free of disease, while in 21 patients (15.1%) anatomo-pathological evaluation found one of the margins to be close; in 16 subjects (11.51%) an involved resection margin was found. Only 6 patients (4.31%) had a recurrence, which occurred in 83.33% of these patients within the first year of follow-up. Disease specific survival was 99.24% after 1 year, 92.4% after 3 years, and 85.91% at 5 years. The multivariate analysis of all covariates showed an increased mortality rate only with regard to pN (HR = 5.043; p = 0.015) and recurrence (HR = 11.586; p = 0.012). Resection margin did not result an independent predictor (HR = 0.757; p = 0.653).

Conclusions

Our study did not recognize resection margin as an independent prognostic factor; most previously published papers lack unanimous, methodological choices, and the cohorts of patients analyzed are not easy to compare. To reach a unanimous agreement regarding the prognostic value of resection margins, it would be necessary to carry out meta-analyses on studies sharing definition of resection margin, methodology and post-operative therapeutic choices.

Keywords: Laryngeal cancer, Resection margin, Local recurrence

Resumo

Introdução

O tratamento do carcinoma de células escamosas de laringe necessita de uma estratificação precisa do risco, para a escolha da terapia mais adequada. O significado prognóstico da margem de ressecção ainda é motivo de debate, considerando-se os resultados contraditórios obtidos em vários estudos sobre a taxa de sobrevida de pacientes com margem de ressecção positiva.

Objetivo

Avaliar o papel prognóstico da margem de ressecção em termos de sobrevida e risco de recorrência de tumor primário através da análise de sobrevida.

Método

Entre 2007 e 2014, 139 pacientes com carcinoma de células escamosas de laringe foram submetidos à laringectomia parcial ou total e foram acompanhados por um tempo médio de 59,44 ± 28,65 meses. O status de margem de ressecção e outras variáveis, como sexo, idade, grau do tumor, pT, pN, técnica cirúrgica adotada e radio- e/ou quimioterapia pós-operatória, foram investigados como fatores prognósticos.

Resultados

Dos pacientes, 45,32% foram submetidos à laringectomia total, enquanto os demais foram submetidos à laringectomia parcial. As margens de ressecção em 73,39% das amostras estavam livres, enquanto em 21 pacientes (15,1%) a avaliação anatomopatológica encontrou uma das margens próxima e 16 indivíduos (11,51%) apresentaram margem de ressecção comprometida. Apenas seis pacientes (4,31%) apresentaram recidiva, o que ocorreu em 83,33% desses pacientes no primeiro ano de seguimento. A sobrevida doença-específica foi de 99,24% em um ano, 92,4% em três anos e 85,91% em cinco anos. A análise multivariada de todas as covariáveis mostrou um aumento na taxa de mortalidade apenas em relação à pN (HR = 5,043; p = 0,015) e recidiva (HR = 11,586; p = 0,012). A margem de ressecção não demonstrou ser um preditor independente (HR = 0,757; p = 0,653).

Conclusões

Nosso estudo não identificou a margem de ressecção como fator prognóstico independente; a maioria dos artigos publicados anteriormente não tem escolhas metodológicas unânimes e as coortes de pacientes analisados não são fáceis de comparar. Para chegar a uma concordância unânime em relação ao valor prognóstico da margem de ressecção, seria necessário fazer metanálises em estudos que compartilham a definição da margem de ressecção, metodologia e escolhas terapêuticas pós-operatórias.

Palavras-chave: Câncer de laringe, Margem de ressecção, Recidiva local

Introduction

In Italy, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) has a yearly incidence of 7 cases per 100,000 inhabitants (AIOM 2016) and, according to data reported by ISTAT, the Italian Institute of Statistics, 1548 patients died of LSCC in 2013. Most of these patients were aged between 60 and 80 years, and the ratio of men/women ranged from 4:1 to 20:1, based on the case histories considered.1

To date, the 5 year relative survival rate in Italy is 68.9% (67.7–70.2%), higher than the European average (58.9%) which is, however, significantly affected by geographical variability, and particularly by a lower survival rate observed in Eastern European countries.

Several risk factors are involved in LSCC pathogenesis, the main two undoubtedly being cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption.2

The treatment of LSCC needs accurate risk stratification, in order to choose the most suitable therapy, foreseeing all possible clinical outcomes. Moreover, knowing post-surgical prognostic factors might positively affect post-operation strategies, increasing patients’ survival rate.3

More specifically, the prognostic significance of resection margin (RM) is still highly debated,4 considering the contradictory results obtained in several studies regarding the survival rate of patients with a positive RM, especially after undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy.5, 6, 7

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the prognostic role of RM in terms of survival and risk of recurrence of primary tumour (T) through survival analysis.

Methods

We performed a retrospective collection of data regarding 139 patients affected by LSCC, admitted and treated in our department between January 1st 2007 and April 30th 2014. Approval for this retrospective study had been obtained from the local ethical committee (Approval No. 11/2017).

All patients underwent a complete clinical evaluation, including fibre-optic video-laryngoscopy, routine blood tests, pulmonary function testing, radiography and/or CT scan of the chest, and CT scan of the neck with and without contrast.

The diagnosis of LSCC was confirmed with a biopsy performed during suspension microlaryngoscopy. Subjects excluded from our study were those either treated with transoral robotic surgery or with known distant metastasis, or with nonsquamous cell malignant tumours, or those who could not undergo the complete surgical procedure.

The cancer staging employed was the TNM criteria approved by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (2010).8

Surgical indications for open partial horizontal laryngectomies (OPHL Type I, IIa and IIb) or total laryngectomy involved patients with LSCC cT1–4aN0–2cM0, who had agreed to be surgically treated; in 134 (96.4%) patients, laryngectomy involved mono- and bilateral selective neck dissection (SND) levels II, III and IV. All patients who had undergone partial surgery, and who experienced recurrence, underwent salvage total laryngectomy. Out of 71 subjects who had indications for adjuvant therapy, 8 did not receive it because of health contraindications (e.g. heart, liver, kidney disease, etc.).

Reports on histopathological findings for each sample obtained during surgery included an accurate macroscopic description, specifying the anatomical site of sampling, dimensions and features of each sample, location of the tumour with a description of anatomical structures involved, a description of the SND procedure, if carried out, specifying number and size of lymph nodes found, and the involvement, if any, of surrounding anatomical structures, such as submandibular gland, sternocleidomastoid muscle and jugular vein.

Diagnostic/microscopic features also included histological type, grading, and size of tumour; the presence or absence of vascular perineural invasion was also marked, as well as infiltration of specific anatomical structures for the various sites.

The evaluation of RMs, suitably folded and sutured, was carried out on samples obtained through exeresis. Margins were classified as “free” (no tumour at or close to the margin), “close” (tumour less than 5 mm from the cut margin), or “involved” (tumour at the cut margin).9 An involved or close margin was considered positive; a free margin was classified as negative.

The variables reported in the dataset for each patient were sex, age, tumour grading, pT, pN, surgical technique adopted, status of RM, post-operative radio- and/or chemotherapy; dates of surgical interventions, detection of recurrence, last check-up, and death caused by the tumour under observation were also included.

Age was used as mean and standard deviation. Other categorical variables were expressed as figures and percentages. Disease specific survival (DSS) was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox proportional hazard ratio models were used to assess independent prognostic factors and for DSS. Significant factors obtained using univariate Cox proportional hazard ratio model were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazard ratio model, except for T, which was excluded due to multicollinearity. A value of p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using STATA.

Results

We carried out a retrospective analysis of data from a cohort of 139 patients (Table 1), 128 men and 11 women (sex ratio = 11.6:1); the age of subjects included ranged between 42 and 87 years (mean age = 63.49 ± 10.25), with a higher mean age (t = 2.28; p = 0.023) for men (64.07 ± 10.22 years) compared to women (56.81 ± 8.44 years).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical characteristics of the cohort.

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | ||||

| M | 128 | 92.08 | <65 | 74 | 53.23 |

| F | 11 | 7.92 | ≥65 | 65 | 46.77 |

| pT | pN | ||||

| T1 | 6 | 4.32 | N0 | 91 | 65.46 |

| T2 | 29 | 20.86 | N1 | 19 | 13.66 |

| T3 | 54 | 38.85 | N2b | 11 | 7.91 |

| T4a | 50 | 35.97 | N2c | 13 | 9.35 |

| Nx | 5 | 3.62 | |||

| Grading | RM | ||||

| G1 | 20 | 14.38 | Free | 102 | 73.39 |

| G2 | 71 | 34.53 | Close | 21 | 15.1 |

| G3 | 48 | 51.09 | Involved | 16 | 11.51 |

| Laryngectomy type | Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| OPHL Type I | 47 | 33.81 | No | 66 | 47.49 |

| OPHL Type IIa | 24 | 17.27 | RT | 10 | 7.19 |

| OPHL Type IIb | 5 | 3.6 | RT+CT | 63 | 45.32 |

| Total | 63 | 45.32 | |||

RT, radiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy.

45.32% (63/139) of the patients underwent total laryngectomy, while the remaining subjects in the cohort underwent partial laryngectomy; in particular, in 47 cases (33.81%) a OPHL Type I was performed, in 24 (17.27) a Type IIa, and a Type IIb in 5 (3.6%).

Anatomo-pathological staging showed a locally advanced tumour (T3–T4a) in 104 patients (74.82%), 6 cases (4.32%) of T1 carcinoma and 29 (20.86%) of T2 type. SND was carried out in 134 subjects; in 5 cases it was not deemed necessary, given the patients’ clinical features.

Resection margins in 73.39% of samples were free, while in 21 patients (15.1%) anatomo-pathological staging found one of the margins to be close; finally, in 16 subjects (11.51%) a microscopic presence of neoplastic cells was found on one of the margins of a sample obtained through exeresis.

Following a surgical procedure, no adjuvant therapy was given to 66 patients; 10 subjects (7.19%) underwent exclusive post-operative radiotherapy, while 63 (45.32%) followed a concomitant chemotherapy. In addition, among subjects with a close RM, 9 (42.85%) were given an adjuvant therapy; the same therapy was given to 13 (81.25%) out of 16 patients with an involved margin. All 43 N+ patients underwent post-operative radiotherapy, with only 4 cases (9.3%) not undergoing concomitant chemotherapy.

Except for 14 cases, where post-operative follow-up occurred after less than 12 months, all other patients were followed for an average period of 59.44 ± 28.65 months (range = 12–122).

Only 6 patients (4.31%) had a recurrence, which developed in 83.33% of these patients within the first year of follow-up. Of these, two had undergone total laryngectomy, 1 OPHL Type I, and 3 OPHL Type IIa. The RM was free in two cases, closes in 3 and involved in one case. Three of the patients with a localized recurrence died during the period of follow-up, 5, 11 and 23 months after diagnosis of recurrence.

Mortality in the cohort, assessed using DSS, showed 99.24% after a year, 92.4% after 3 years, and 85.91% at 5 years.

Table 2 shows the features of patients who died during our study. Six subjects (37.5%) had undergone OPHL Type I, 4 (25%) OPHL Type IIa, 6 (37.5%) total laryngectomy. In 56.25% of the cases, anatomo-pathological tests had shown lymph node metastases, while a type T4a carcinoma was observed in 87.5% of subjects; on average, death occurred within 31.93 ± 18.89 months from surgery.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients dead during follow-up.

| N | Gender | Age | Grading | pT | pN | Laryngectomy type | RM | RT/CT | Recurrence | Survival (months) | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 60 | 2 | 2 | 0 | OPHL Type IIa | Free | No | No | 28 | Distant metastasis |

| 2 | M | 62 | 3 | 3 | 2b | OPHL Type IIa | Free | Yes | No | 42 | Distant metastasis |

| 3 | M | 60 | 3 | 4a | 2b | OPHL Type IIa | Involved | Yes | No | 38 | Distant metastasis |

| 4 | M | 69 | 3 | 4a | 2b | OPHL Type IIa | Involved | Yes | No | 44 | Distant metastasis |

| 5 | F | 55 | 2 | 2 | 2b | OPHL Type 1 | Close | Yes | No | 47 | Distant metastasis |

| 6 | M | 63 | 2 | 3 | 1 | OPHL Type 1 | Free | Yes | No | 77 | Distant metastasis |

| 7 | M | 70 | 1 | 3 | 2c | OPHL Type 1 | Free | Yes | No | 13 | Distant metastasis |

| 8 | M | 51 | 3 | 3 | 0 | OPHL Type 1 | Free | Yes | No | 32 | Distant metastasis |

| 9 | M | 57 | 2 | 3 | 2c | OPHL Type 1 | Involved | Yes | No | 36 | Distant metastasis |

| 10 | M | 69 | 2 | 4a | 0 | OPHL Type 1 | Close | Yes | Yes | 33 | Distant metastasis |

| 11 | M | 84 | 1 | 4a | – | Total | Free | No | Yes | 13 | Peristomal recurrence and distant metastasis |

| 12 | M | 87 | 3 | 4a | 0 | Total | Free | No | Yes | 32 | Peristomal recurrence and distant metastasis |

| 13 | M | 70 | 3 | 4a | 2b | Total | Free | Yes | No | 14 | Distant metastasis |

| 14 | M | 64 | 2 | 4a | 2c | Total | Free | Yes | No | 2 | Distant metastasis |

| 15 | M | 75 | 2 | 4a | 1 | Total | Close | Yes | No | 36 | Distant metastasis |

| 16 | M | 72 | 3 | 4a | 2c | Total | Free | Yes | No | 12 | Distant metastasis |

With regard to pN, 37.5% of patients classified as N2b–2c, died during the follow-up period, as well as 10.52% of N1 cases and 4.39% of N0 cases. More specifically, one of the N2b–2c patients died during the 1st year of follow-up, 3 between the 2nd and 3rd year, and 5 between the 4th and 5th year.

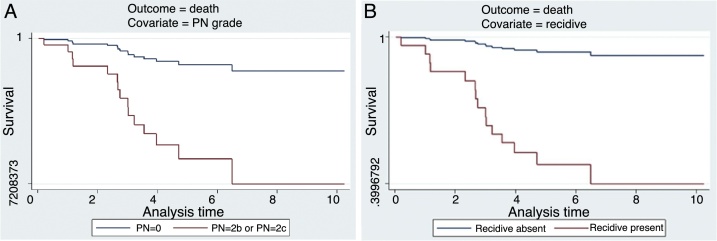

As shown in Table 3, a multivariate analysis of all covariates (sex, age, grading, pT, pN, type of surgery, RM status, adjuvant therapy and recurrence) showed an increased mortality rate (Fig. 1A and B) only with regard to pN (HR = 5.043; p = 0.015) and recurrence (HR = 11.586; p = 0.012). RM was not deemed as an independent predictor (HR = 0.757; p = 0.653); it would not, instead, appear to be linked to the risk of recurrence (p = 0.052).

Table 3.

Survival analysis of the cohort.

| Outcome = mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate (a) | Univariate analysis (HR) |

Multivariate analysis (HR) |

||

| HR | p | HR | p | |

| Gender | ||||

| M vs. F | 1.563 | 0.666 | 1.211 | 0.863 |

| Age | ||||

| 1° or 2° tertile vs. 3° tertile | 2.484 | 0.070 | 1.434 | 0.518 |

| Grading | ||||

| G3 vs. G1-2 | 1.651 | 0.321 | – | – |

| T stage | ||||

| T2–3 vs. T1 | 4.12e+08 | – | – | – |

| T4a vs. T1 | 1.09e+09 | <0.0001 | – | – |

| N stage | ||||

| N2b–2c vs. N0–1 | 7.352 | <0.0001 | 5.043 | 0.015 |

| Laryngectomy type | ||||

| OPHL Type I or OPHL Type IIa or Total vs. OPHL Type IIb | 1.69e+15 | – | – | – |

| RM | ||||

| Positive vs. negative | 1.443 | 0.477 | 0.757 | 0.653 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| RT/CT vs. no adjuvant therapy | 0.162 | 0.005 | 0.209 | 0.062 |

| Local relapse | ||||

| Recurrence vs. no recurrence | 6.591 | 0.004 | 11.586 | 0.012 |

HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Disease specific survival of patients with different pN (A) and with or without recurrence (B).

Discussion

Deeper knowledge of the embryology, anatomy and function of the larynx has allowed the development of a wider range of surgical procedures for the treatment of LSCC, but, still today, the choices made by an ENT surgeon during an operation, or the conclusions reached by multidisciplinary teams including oncologists and radiotherapists are inevitably affected by multiple factors, some of which cannot be taken into consideration in a pre-operative phase.

Resection margins are included among these factors, and have been the focus of numerous studies, which have attempted to test their reliability from an oncologic point of view. A positive RM is now generally followed, in conjunction with a patient's clinical condition, with a widening of the exeresis and/or a post-operative radio-chemotherapy treatment, aimed at reducing the risk of localized recurrence.10

Notwithstanding the above, and as a demonstration of the complexity of this subject, some studies have not identified a lower risk of recurrence and/or worse survival in patients with a negative margin, compared to patients with a positive RM who had not been given an adjuvant therapy, but who had only been closely followed up.11, 12

The potential role of RM as an independent predictor of survival is still being debated, since there are no definitive data available which takes into account the heterogeneity of LSCC cases, from a staging and bio-molecular point of view.

A close observation of the main findings from analytical studies reported in Table 4 shows, above all, that the cases presented by various authors cited do not have a common denominator, in terms of type of surgical procedure and local extension of a neoplasia. Half of the quoted studies, indeed, report both partial and total (in some cases, also through endoscopy) surgical procedures on the larynx, including samples with pT1–4. In a few cases, RM was evaluated in patients who had undergone salvage surgery after failure of radiotherapy.6

Table 4.

Literature review of the prognostic role of RM.

| Authors | Year | Sample | Laryngectomy | T | R1% | R0% | Recurrence | OS | DFS | DSS | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradford et al. | 1996 | 159 | Partial and total | T1–T4 | 15.72 | 84.28 | ns | ns | ns | – | Multi |

| Naudè et al. | 1997 | 182 | Partial and total | T1–T4 | 45.06 | 54.94 | 0.02 | – | – | ns | Uni |

| Bron et al. | 2000 | 69 | SCPL | T1–T4 | 11.59 | 88.41 | ns | – | – | <0.006 | Multi |

| Sessions et al. | 2002 | 200 | Partial and total | T3 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.04 | Uni |

| Dufour et al. | 2004 | 118 | SCPL | T3 | 2.54 | 94.92 | <0.001 | – | – | – | Uni |

| Gallo et al. | 2004 | 253 | SCPL | T1–T4 | 15.82 | 84.18 | 0.06 | ns | – | – | Multi |

| Yu et al. | 2006 | 65 | Partial and total | T3 | – | – | – | ns | – | – | – |

| Sun et al. | 2009 | 63 | SCPL e TCHEP | T1–T4 | 17.46 | 82.54 | 0.028 | ns | – | – | Multi |

| Liu et al. | 2009 | 221 | Partial and total | T1–T4 | 17.65 | 82.35 | – | 0.015 | 0.001 | – | Multi |

| Soudry et al. | 2010 | 29 | Partial and total | T1–T4 | 41.37 | 58.63 | – | 0.035 | ns | – | Multi |

| Karatzanis et al. | 2010 | 1314 | Partial and total | T1–T4 | 9.3 | 90.7 | – | <0.001 | – | – | Multi |

| Liu et al. | 2013 | 183 | Partial | – | – | – | – | <0.05 | – | – | Multi |

| Zhang et al. | 2013 | 205 | Partial and total | T1–T4 | 15.1 | 84.9 | – | <0.001 | – | – | Multi |

| Page et al. | 2013 | 175 | SCPL | T1–T3 | 9.14 | 90.86 | ns | 0.0001 | – | – | Multi |

| Basheeth et al. | 2014 | 75 | Total | T1–T4 | 16 | 84 | <0.001 | 0.03 | – | 0.05 | Multi |

| De Virgilio et al. | 2016 | 35 | Total | T1, T2 | 0.85 | 99.15 | – | – | – | ns | Multi |

| Eskiizmir et al. | 2017 | 85 | Partial and total | T3, T4 | 12.9 | 87.1 | ns | ns | ns | ns | Multi |

R1, positive margin; R0, negative margin; SCPL, supracricoid partial laryngectomy; TCHEP, tracheocricohyoidoepiglottopexy.

A prevalence of positive RM was seen between 1% and 45%, ranging, in most cases, between 10% and 17%, a percentage only a bit lower than the 26.6% found in our cohort.

Recurrence was not acknowledged by all authors as connected to RM, regardless of the type of surgical procedure adopted. Out of 9 studies where this connection was analyzed, five did not find any statistical significance, while in one case this was found only with regard to type T3–4 tumours, not in initial or intermediate stages13; analogously, our study could not find a statistically valid analysis either (p = 0.052).

It is, however, worth mentioning that, among our patients, the only two cases of a localized recurrence on a free margin occurred in patients who had undergone total laryngectomy for T4a (SND was not performed in one case), not followed by adjuvant therapy, given the patient's age, >80 years. Since it was peristomal recurrence, similar to what was described by Basheeth et al., the RM may have had no relevance.14

With regard to the survival analysis performed by many authors, calculating curves for overall survival (OS), DSS and disease free survival (DFS), again there is no unanimous interpretation regarding the prognostic significance of RM. About half of the authors found no statistically significant difference in survival curves between subjects with positive or negative RM.5, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Others, on the contrary, such as Karatzanis et al. and Page et al., as corroborated by the high statistical significance observed (p ≤ 0.0001), identified RM as an independent prognostic factor.21, 22, 23

Our study would side with the former group, even if only regarding DSS, since OS could not be assessed, as it was not possible to properly collect the information needed for this subtype of survival curve. Regarding DSS, only Bron et al. and Sessions et al. found a statistically significant difference between positive and negative RMs, even if studying two entirely different cohorts (the former consisting of patients who had undergone supracricoid partial laryngectomy (SCPL) for T1–4, the latter including also patients who had undergone total laryngectomy, but only for T3 tumours).24, 25

Some authors opted to analyze the ratio between margin and DFS, that is to say, the time elapsed between surgical procedure and neoplastic recurrence; only Liu et al. observed a significant effect (p < 0.05) of RM, related with the abovementioned survival rate.26

According to the results of our statistical analysis, coinciding with most of the studies cited, pN resulted an independent prognostic factor, with 37.5% of N2b–2c patients having died during the period of follow-up (HR = 5.043; p = 0.015).

As well as the retrospective nature of the study, which may not include certain confounders which could influence the outcomes, our work contains other weak points. First of all, the lack of significance of certain covariates could be influenced by the cohort size and the relatively few number of events (deaths) observed; however, as showed in Table 4, it appears evident that about half of the authors cited reported smaller samples size. Secondly, even if literature is full of studies which assess the role of RM as prognostic factor including patients who underwent open but also transoral laryngeal surgery, we believe that survival analysis data about a single technique need to be provided because the choice of surgery is generally influenced by TNM and might indirectly affect the prognosis.

Discrepancies observed on comparing data available from literature with the results obtained from the analysis of our cohort of patients do not allow us to draw definitive conclusions regarding the relationship of RM with the prognosis of patients affected by LSCC.

This is largely explained by a series of critical methodological points, intrinsically connected with defining and interpreting RMs. Evaluation of RMs is the arrival point of a multi-level process involving several professionals, and including several aspects in the oncological field. These aspects, in turn, may be affected by multiple variables, which might not always be taken into account, and which are not, above all, explicitly reported in scientific studies.

Conclusions

Our study did not recognize RM as an independent prognostic factor (HR = 0.757; p = 0.653); most previously published papers lack unanimous, methodological choices, and the cohorts of patients analyzed are difficult to compare, due to different staging phases, and type of laryngectomy carried out, given, unlike other authors, particularly strict selection criteria.

To reach a unanimous agreement regarding the prognostic value of RMs, therefore, it would be necessary to carry out meta-analysis on studies rigorously overlapping, with regard to definition, methodology and post-operative therapeutic choices. Another possibility which should be considered is the search for genetic markers in a margin, to help predict risk of recurrence, and/or patient survival more accurately, thus having a reliable tool, for more effective, post-operative management.27

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer Review under the responsibility of Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial.

Please cite this article as: Saraniti C, Speciale R, Gallina S, Salvago P. Prognostic role of resection margin in open oncologic laryngeal surgery: survival analysis of a cohort of 139 patients affected by squamous cell carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;85:603–10.

References

- 1.Karatzanis A.D., Waldfahrer F., Psychogios G., Hornung J., Zenk J., Velegrakis G.A., et al. Resection margins and other prognostic factors regarding surgically treated glottic carcinomas. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:131–136. doi: 10.1002/jso.21449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashibe M., Boffetta P., Zaridze D., Shangina O., Szeszenia-Dabrowska N., Mates D., et al. Contribution of tobacco and alcohol to the high rates of squamous cell carcinoma of the supraglottis and glottis in Central Europe. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:814–820. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S.Y., Lu Z.M., Luo X.N., Chen L.S., Ge P.J., Song X.H., et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors in 205 patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma who underwent surgical treatment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman H.T., Porter K., Karnell L.H., Cooper J.S., Weber R.S., Langer C.J., et al. Laryngeal cancer in the United States: changes in demographics, patterns of care, and survival. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1–13. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000236095.97947.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallo A., Manciocco V., Simonelli M., Pagliuca G., D’Arcangelo E., de Vincentiis M. Supracricoid partial laryngectomy in the treatment of laryngeal cancer: univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:620–625. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.7.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soudry E., Hadar T., Shvero J., Segal K., Shpitzer T., Nageris B.I., et al. The impact of positive resection margins in partial laryngectomy for advanced laryngeal carcinomas and radiation failures. Clin Otolaryngol. 2010;35:402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2010.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soo K.C., Carter R.L., O’Brien C.J., Barr L., Bliss J.M., Shaw H.J. Prognostic implications of perineural spread in squamous carcinomas of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:1145–1148. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198610000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edge S.B., Byrd D.R., Compton C.C., Fritz A.G., Greene F.L., Trotti A., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. Springer; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spector G.J., Sessions D.G., Lenox J., Newland D., Simpson J., Haughey B.H. Management of stage IV glottic carcinoma: therapeutic outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1438–1446. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200408000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yilmaz T., Turan E., Gürsel B., Onerci M., Kaya S. Positive surgical margins in cancer of the larynx. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:188–191. doi: 10.1007/s004050100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer W.C., Lesinski S.G., Ogura J.H. The significance of positive margins in hemilaryngectomy specimens. Laryngoscope. 1975;85:1–13. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenig B.L., Berry B.W., Jr. Management of patients with positive surgical margins after vertical hemilaryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:172–175. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890020034008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naudé J., Dobrowsky W. Postoperative irradiation of laryngeal carcinoma – the prognostic value of tumour-free surgical margins. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:273–277. doi: 10.3109/02841869709001262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basheeth N., O’Leary G., Khan H., Sheahan P. Oncologic outcomes of total laryngectomy: impact of margins and preoperative tracheostomy. Head Neck. 2015;37:862–869. doi: 10.1002/hed.23681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradford C.R., Wolf G.T., Fischer S.G., McClatchey K.D. Prognostic importance of surgical margins in advanced laryngeal squamous carcinoma. Head Neck. 1996;18:11–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199601/02)18:1<11::AID-HED2>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu W.B., Zeng Z.Y., Chen F.J., Peng H.W. Treatment and prognosis of stage T3 glottic laryngeal cancer—a report of 65 cases. Ai Zheng. 2006;25:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun D.I., Cho K.J., Cho J.H., Joo Y.H., Jung C.K., Kim M.S. Pathological validation of supracricoid partial laryngectomy in laryngeal cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:132–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Virgilio A., Greco A., Bussu F., Gallo A., Rosati D., Kim S.H., et al. Salvage total laryngectomy after conservation laryngeal surgery for recurrent laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016;36:373–380. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskiizmir G., Tanyeri Toker G., Celik O., Gunhan K., Tan A., Ellidokuz H. Predictive and prognostic factors for patients with locoregionally advanced laryngeal carcinoma treated with surgical multimodality protocol. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:1701–1711. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4411-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dufour X., Hans S., De Mones E., Brasnu D., Ménard M., Laccourreye O. Local control after supracricoid partial laryngectomy for “advanced” endolaryngeal squamous cell carcinoma classified as T3. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1092–1099. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.9.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T.R., Yang A.K., Chen F.J., Zeng M.S., Song M., Guo Z.M., et al. Survival and prognostic analysis of 221 patients with advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated by surgery. Ai Zheng. 2009;28:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karatzanis A.D., Waldfahrer F., Psychogios G., Hornung J., Zenk J., Iro H. Resection margins and other prognostic factors regarding surgically treated glottic carcinomas. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:131–136. doi: 10.1002/jso.21449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page C., Mortuaire G., Mouawad F., Ganry O., Darras J., Pasquesoone X., et al. Supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidoepiglottopexy (CHEP) in the management of laryngeal carcinoma: oncologic results. A 35-year experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1927–1932. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bron L., Brossard E., Monnier P., Pasche P. Supracricoid partial laryngectomy with cricohyoidoepiglottopexy and cricohyoidopexy for glottic and supraglottic carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:627–634. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sessions D.G., Lenox J., Spector G.J., Newland D., Simpson J., Haughey B.H. Management of T3N0M0 glottic carcinoma: therapeutic outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1281–1288. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200207000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu C., Xu Z.G. Clinical analysis of relevant factors causing postoperative recurrence of laryngeal cancer after partial laryngectomy. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2013;35:377–381. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallina S., Sireci F., Lorusso F., Di Benedetto D.V., Speciale R., Marchese D., et al. The immunohistochemical peptidergic expression of leptin is associated with recurrence of malignancy in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35:15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]