Abstract

Growth of a wall-less, L-form of Escherichia coli specifically requires calcium, and in its absence, cells ceased dividing, became spherical, swelled, developed large vacuoles, and eventually lysed. The key cell division protein, FtsZ, was present in the L-form at a concentration five times less than that in the parental strain. One interpretation of these results is that the L-form possesses an enzoskeleton partly regulated by calcium.

Numerous roles for calcium in bacteria are now becoming apparent (10, 12, 19). We have proposed that calcium has a role as a “general reset” in cells (12) and that it participates in the regulation of the putative bacterial “enzoskeleton” (14). This enzoskeleton would comprise proteins such as the tubulin-like protein, FtsZ, which is the key player in cell division and which in vitro has a calcium-stimulated polymerization and GTPase activity (24). L-forms are wall-less derivatives of bacteria that grow and divide despite their lack of a normal peptidoglycan sacculus (7, 8, 15, 18, 22). This means that the morphology and progress through the cell cycle of L-forms must result from forces acting via some structure other than the sacculus. Membrane domains have been considered candidates for such structures (7), and these probably result from the coupled transcription, translation, and insertion (transertion) of proteins into and through membranes (1), processes that generate sufficient force to hold L-forms together (13). The L-form NC-7, which is a derivative of an Escherichia coli K-12 strain (16), possesses a secondary calcium/proton antiporter (17) and reveals a general inhibition of growth following addition of the calcium chelator EGTA (15 [but also see reference 23]). NC-7 is therefore an ideal model system for exploring the hypothesis of an enzoskeleton controlled by calcium.

Effects of divalent ions on growth.

First, the identity of the L-forms derived from E. coli (16) was confirmed by PCR amplification of ftsZ, hisS, and orf80 to obtain products of the expected Mr (20), sequencing of 210 bp of the glnA gene (cloned at random), and N-terminal sequencing of Dps, YfiD, and the E1 component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (4). Then, to study the effects of divalent ions, cells were preincubated in modified Na-Davis medium plus 1 mM EGTA and 2 μM ionophore A23187 (to equilibrate internal and external calcium levels) for 3 h, harvested in the exponential phase of growth by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 10 min), washed once with growth medium, and resuspended in modified Na-Davis medium containing either 0.2 or 0.5 mM BAPTA [1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid]. Modified Na-Davis medium contains 0.7 g of K2HPO4, 0.2 g of KH2PO4, 1 g of (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g of sodium succinate, 2 g of peptone, 1 g of yeast extract, 2 g of glucose, 0.34 M NaCl, 105 U of penicillin G, and 50 μM (each) FeCl2, ZnCl2, MgCl2, CaCl2, and MnCl2. Cells were agitated at 45 rpm and 32°C, and plastic tubes were used throughout. Following preincubation, cells were transferred to fresh medium containing 0.5 mM metal chelator BAPTA and 50 μM concentrations of Fe, Zn, Mg, and Mn. Under these conditions, growth was inhibited, and only addition of a higher concentration of 1.2 mM calcium was sufficient to restore growth (Table 1). Similar results were obtained in other experiments using 0.2 mM BAPTA and a 1 mM concentration of single ion species as well as in experiments with iron, cobalt, copper, and zinc chloride (data not shown). Addition of only 50 μM calcium, sufficient to release a trace element, was not sufficient to restore normal growth (data not shown). It should be noted that preincubation of cells in both A23187 and EGTA is essential if growth inhibition by EGTA is to be reversed specifically by calcium (rather than divalent ions in general). These experiments strongly indicate that calcium is required for the growth of L-forms.

TABLE 1.

Effects of divalent ions on L-form growth yieldsa

| Ion addition (1.2 mM) |

L-form growth yield (OD600) |

|---|---|

| None | 0 |

| CaCl2 | 0.21 |

| FeCl2 | 0.01 |

| ZnCl2 | 0.01 |

| MgCl2 | 0.00 |

| MnCl2 | 0.01 |

Cells were precultured in modified Na-Davis medium containing 1 mM EGTA and 2 μM A23187 and then transferred to fresh medium (containing 0.5 mM BAPTA, 1.2 mM the ion shown, and 50 μM the other divalent ions for 24 h). Optical densities at 600 nm (OD600) were determined.

Effect of EGTA on morphology.

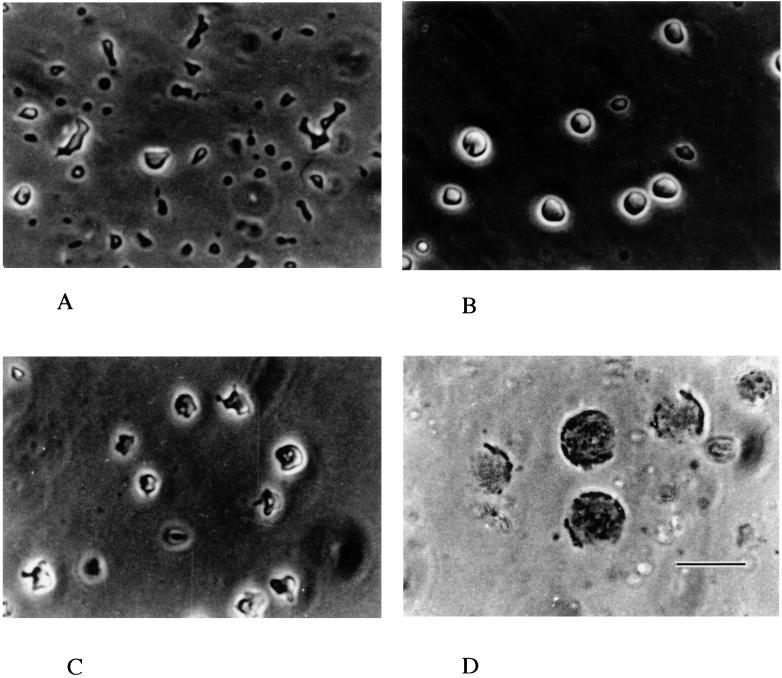

L-forms were grown in NaPY medium containing per liter: 10 g of peptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 2 g of glucose, 0.34 M NaCl, and 105 U of penicillin G. NaPY medium contains 0.12 mM Ca2+, 12.7 μM Fe2+, 8.1 μM Zn2+, and 1.5 μM Mn2+, as determined by flame spectrophotometry. The pH in the medium was adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. Phase-contrast microscopy revealed that cells are different shapes and sizes (Fig. 1A). Some images may simply correspond to deformations that have no functional role, while others must also correspond to cell division, which is often asymmetric and involves budding (Fig. 1A). On transfer to medium containing 1 mM EGTA, most cells became spherical, and the average volume increased 1.5 times during incubation (Fig. 1B). This increase is not due to fusion of cells, since the numbers of CFU did not reveal a concomitant decrease during this period (data not shown) and since fusing and dividing cells were not observed. Up to 6 h, these morphological changes were completely reversible, and the 1 mM EGTA-treated, spherical cells reverted to the polymorphic form 1 to 2 h after addition of 2 mM calcium (Fig. 1C). In the absence of calcium, however, continued incubation in 1 mM EGTA led to the formation of what appeared to be vacuoles inside cells, reduced viability, and, finally, lysis (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Phase-contrast micrographs of the L-form treated with EGTA. Cells growing exponentially in NaPY medium containing 1 mM calcium were harvested and transferred to fresh medium with the following additions: none (A), 1 mM EGTA for 6 h (B), 1 mM EGTA for 6 h followed by 2 mM calcium for 1.5 h (C), or 1 mM EGTA for 36 h (D). The bar represents 5 μm.

The structure of the L-forms.

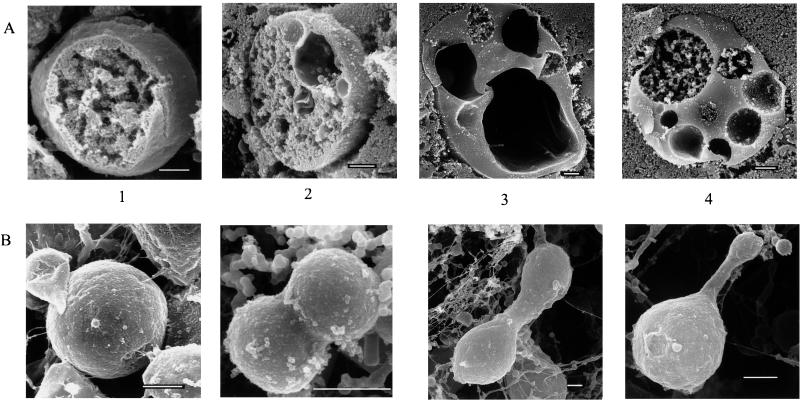

To investigate further the structure of the L-forms and the morphological changes resulting from EGTA addition, L-forms growing exponentially in NaPY medium containing 1 mM calcium were harvested, preincubated in NaPY medium containing 1 mM EGTA and 2 μM A23187 for 1 h, and then transferred to fresh medium containing 1 mM EGTA. Scanning electron microscopy was performed on freeze-fractured cells (Fig. 2A). At the times indicated, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min and washed once with 0.067 M phosphate buffer containing 0.75 M KCl. Washed cells were resuspended in a small amount of 0.067 M phosphate buffer containing 0.75 M KCl, transferred to a paper filter (Whatmann 3MM; 5 by 5 mm) and fixed by the osmium-tannic acid-osmium method (21). Specimens were dehydrated with ethanol in increasing concentrations, dried in a critical point dryer (Hitachi HCP-2), coated with Pt-Pd in an ion spatter device (Hitachi H102), and analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S-800). Intracellular structures were observed by a combination of the chitosan embedding and the osmium dimethyl sulfoxide-osmium methods (5). In cells at the start of the experiment, a coralline structure with a dense, granular surface filled the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A, panel 1). Cell division appeared to occur in a variety of symmetrical and asymmetrical ways. Buds of sometimes very different sizes were observed separated by long necks in which no clear septum was visible (Fig. 2B). In some dividing cells, the first stage of budding could be seen, and this often appeared to involve a future daughter about 1 μm in diameter forming from a parental cell about 3 μm in diameter (Fig. 2B). There are many small spherical objects around 300 nm in diameter that are probably the lysed remains of membranes (Fig. 2B). After 12 h in EGTA medium (Fig. 2A, panels 2, 3, and 4), the structure of the cells was different, and as suggested by light microscopy (Fig. 1D), large vacuoles had formed. These vacuoles, which were up to 5 μm in diameter at the 12-h stage, were much larger than those that were sometimes seen in the cells grown in the presence of free calcium, and there were often several of them in each cell. The formation of vacuoles (6, 8) and structures resembling microtubules (3) have been reported in L-forms of E. coli and other bacteria as well as paracrystalline inclusion bodies adjacent to the membrane and “stiff, nontubular cores” (6). While such cytoplasmic cores were not observed in this study, a network of filaments, possibly adjacent to the membrane, did appear to be present in some cells at the start of the experiment (data not shown). The polymerization of FtsZ into a ring-like structure associated with the cytoplasmic membrane is considered the key step in cell division in bacteria. In vitro, this polymerization can be stimulated by calcium. FtsZ is an evident component of an enzoskeleton, and we speculated that a substantial increase in the level of FtsZ in the L-form might confer a structural stability that would be dependent on calcium. The L-form and its parental strain were therefore grown under identical conditions, and immunoblot experiments were performed at a range of protein concentrations using a 1:4,000 dilution of anti-FtsZ polyclonal antibodies (generously given by Miguel Vicente), a 1:4,000 dilution of antirabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma), and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) with typical exposure times of 1 min. L-form extracts were not centrifuged after sonication, since significant amounts of FtsZ are associated with L-form membrane. Surprisingly, densitometry revealed that FtsZ levels were fivefold lower per unit of protein in the L-form than in the parental strain (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron micrographs of the L-form. (A) Freeze-fractured cells after growth in NaPY medium (panel 1) and after a 12-h incubation in NaPY medium containing 1 mM EGTA (panels 2, 3, and 4). (B) Cells after growth in NaPY medium. Each bar represents 1 μm.

It has been proposed that the peptidoglycan sacculus has been replaced in L-forms by the macromolecular components of the cytoplasm that can act as structural components (7). Indeed, L-forms offer the possibility of revealing an enzoskeleton that is masked in wild-type bacteria by the sacculus. This enzoskeleton would comprise equilibrium and nonequilibrium hyperstructures, some of which would be regulated by calcium (9). In the latter case, hyperstructures are assemblies of proteins, membranes, and nucleic acids, each responsible for a particular function such as sugar transport or cell division (11), as others have also proposed (2). It is therefore conceivable that the absence of a normal wall in the L-form leads to a general reduction in expression in the 2-min cluster where ftsZ lies, perhaps via a reduction in transertion. The consequently low level of FtsZ may be too low for division to occur efficiently in the L-form, as evidenced perhaps by its varied patterns of cell division.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nanne Nanninga for FtsZ protein, Miguel Vicente for antibodies to FtsZ, Kathryn Lilley and Janette Maley for technical assistance, and Susan Grant and Istvan Toth for encouragement.

We also thank the BBSRC and the EU for support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binenbaum Z, Parola A H, Zaritsky A, Fishov I. Transcription- and translation-dependent changes in membrane dynamics in bacteria: testing the transertion model for domain formation. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1173–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buddelmeijer N, Aarsman M E G, Kolk A H J, Vicente M, Nanninga N. Localization of cell division protein FtsQ by immunofluorescence microscopy in dividing and nondividing cells of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6107–6116. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6107-6116.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eda T, Kanda Y, Kimura S. Membrane structures in stable L-forms of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1564–1567. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1564-1567.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freestone P, Grant S, Trinei M, Onoda T, Norris V. Protein phosphorylation in Escherichia coli L-form NC-7. Microbiology. 1998;144:3289–3295. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukudome H, Tanaka K. A method for observing intracellular structures of free cells by scanning electron microscopy. J Micros. 1986;141:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1986.tb02713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gumpert J. Ultrastructural characterization of core structures and paracrystalline inclusion bodies in L-form cells of streptomycetes. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1983;23:625–633. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3630231004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumpert J. Cellular growth without a murein sacculus—the nucleoid-associated compartmentation concept. In: de Pedro M A, Holtje J-V, Loffelhardt W, editors. Bacterial growth and lysis. Metabolism and structure of the bacterial sacculus. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 453–463. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lederberg J, St. Clair J. Protoplasts and L-type growth of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1958;75:143–160. doi: 10.1128/jb.75.2.143-160.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris V, Alexandre S, Bouligand Y, Cellier D, Demarty M, Grehan G, Gouesbet G, Guespin J, Insinna E, Le Sceller L, Maheu B, Monnier C, Grant N, Onoda T, Orange N, Oshima A, Picton L, Polaert H, Ripoll C, Thellier M, Valleton J-M, Verdus M-C, Vincent J-C, White G, Wiggins P. Hypothesis: hyperstructures regulate bacterial structure and the cell cycle. Biochimie. 1999;81:915–920. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris V, Chen M, Goldberg M, Voskuil J, McGurk M, Holland I B. Calcium in bacteria: a solution to which problem? Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:775–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris V, Gascuel P, Guespin-Michel J, Ripoll C, Saier M H., Jr Metabolite-induced metabolons: the activation of transporter-enzyme complexes by substrate binding. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1592–1595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norris V, Grant S, Freestone P, Canvin J, Sheikh N F, Toth I, Trinei M, Modha K, Norman R I. Calcium signalling in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3677–3682. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3677-3682.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris V, Onoda T, Pollaert H, Grehan G. The mechanical origins of life. Biosystems. 1999;49:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0303-2647(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris V, Turnock G, Sigee D. The Escherichia coli enzoskeleton. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:197–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.373899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onoda T, Oshima A. Effects of Ca2+ and a protonophore on growth of an Escherichia coli L-form. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:3071–3077. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-11-3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onoda T, Oshima A, Nakano S, Matsuno A. Morphology, growth and reversion in a stable L-form of Escherichia coli K12. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:527–534. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onoda T, Shinjou H, Oshima A. Cation/proton antiport systems in Escherichia coli K12, L-form NC-7. Mem Fac Sci Shimane Univ. 1989;20:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paton A M. L-forms: evolution or revolution? J App Bacteriol. 1987;63:365–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1987.tb04856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith R J. Calcium and bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1995;37:83–103. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweeney S T, Freestone P, Norris V. Identification of novel phosphoproteins in Escherichia coli using the gene-protein database. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;127:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi G. OsO4-tannin-OsO4 fixation and staining of biological specimens for electron microscopy. J Electron Microsc. 1978;27:66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waterhouse R N, Buhariwalla H, Bourn D, Rattray E J, Glover L A. CCD detection of lux-marked Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola L-forms associated with Chinese cabbage and the resulting disease protection against Xanthomonas campestris. Lett App Microbiol. 1996;22:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youatt J. The toxicity of metal chelate complexes of EGTA precludes the use of EGTA buffered media for the fungi Allomyces and Achlya. Microbios. 1994;79:171–185. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu X-C, Margolin W. Ca2+-mediated GTP-dependent assembly of bacterial cell division protein FtsZ into asters and polymer networks in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:5455–5463. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]