Abstract

We report on novel mutations in the malK gene of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, encoding the ATPase subunit of the maltose transporter (MalFGK2). Biochemical analysis suggests that (i) L86 might be involved in a signaling step during substrate translocation and (ii) E306 may be critical for the structural integrity of the protein.

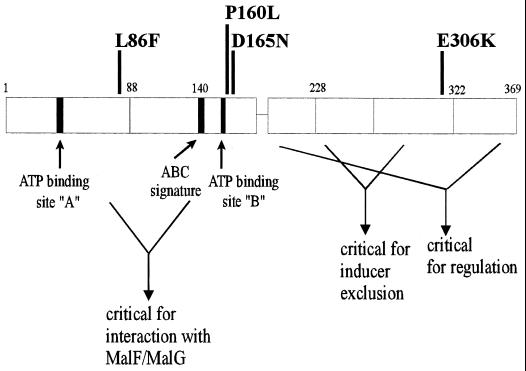

In enterobacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, the uptake of maltose-maltodextrins is mediated by the MalFGK2 transport complex, which is a member of the superfamily of ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) transport proteins (1). MalF and MalG are hydrophobic membrane-integral components, while MalK represents the ABC subunit of the complex. In addition, a soluble extracellular (periplasmic) substrate-binding protein, MalE, is also required for activity. When separated from the hydrophobic subunits, MalK displays a spontaneous ATPase activity (10, 19), while in the MalFGK2 complex ATP hydrolysis is observed only concomitantly with transport (3, 7). Thus, ligand translocation and ATP hydrolysis are dependent on a signaling mechanism initiated by the substrate-loaded binding protein and transmitted through MalF-MalG (4). Besides being indispensable for transport, MalK displays a regulatory function by phenotypically acting as a repressor of genes belonging to the maltose regulon (1). The mechanism of this activity is currently unknown, but evidence for binding of MalK to MalT, the positive regulator of the maltose regulon, has recently been presented (12). These and other functions can be separated by mutations (8, 9); this finding, together with data from the study of half molecules and chimeras (13), has led to the proposal of a domain structure as presented in Fig. 1. Accordingly, the protein is composed of two structurally distinct entities, with the regulatory functions being mostly confined to the C-terminal extension of about 100 residues by which MalK differs in length from a prototype ABC domain (15). However, recent results from this laboratory also indicated that the C-terminal domain may not simply be hooked to a consensus ABC domain to provide a regulatory activity but is an integral part of the tertiary structure (13). To further investigate the structure-function relationship between the proposed domains of MalK, we have used chemical mutagenesis to isolate novel, previously uncharacterized mutations in the malK gene of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium.

FIG. 1.

Proposed domain structure of MalK. The relative positions of mutated residues described in this communication are indicated. See text for details (modified from reference 21).

Random mutagenesis, sequencing, and characterization of mutants in vivo.

Serovar Typhimurium and E. coli strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions were previously described (13, 14, 21). Chemical mutagenesis of the malK gene was performed by treatment of plasmid pSW7 (malK under the control of the trc promoter on plasmid vector pSE380) (20) with hydroxylamine as described elsewhere (21). Purified plasmid DNA was subsequently used to transform the MalK− strain ES25 (17). Transformants were screened for mutations on MacConkey agar-maltose-ampicillin plates. Plasmid DNA from four putative candidates (white colonies) were isolated and subjected to nucleotide sequence analysis using a LiCor semiautomatic sequencer (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). Base changes translating into the following amino acid substitutions were found: L86F-R113C (malK819), P160L (malK824), D165N (malK825), and E306K (malK822). For further analysis of malK819, both changes were separately introduced into the wild-type allele (on pSW7) by means of site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange kit; Stratagene) and the resulting plasmids were used to transform ES25. While plasmid pSH17-N42, carrying the malK821 allele (R113C), gave rise to red colonies on MacConkey agar-maltose plates, expression of malK820 (L86F) from plasmid pSH17-N41 resulted in white colonies. Thus, the growth defect of malK819 was due solely to the L86F mutation (malK820), and consequently, the malK821 allele was not further considered.

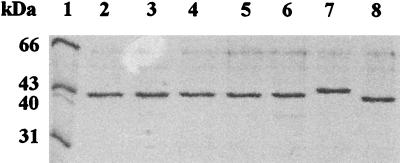

The failure of the remaining MalK mutants to support growth of strain ES25 on maltose was confirmed by transport assays that were performed as described in reference 17. The initial rates of [14C]maltose uptake never exceeded 4% of the rate measured with control cells that harbored the plasmid-borne wild-type allele (pSW7) (Table 1). All mutant proteins were stably produced as verified by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell extracts. Interestingly, the E306K mutation caused a mobility shift of the protein (not shown, but see Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Transport and regulatory properties of MalK mutants

| Plasmid | Allele | Protein synthesized | Maltose uptakea (%) | Repressing activityb (Miller units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSE380 | 0 | 159 | ||

| pSW7 | malK+ | Wild type | 100 | 11 |

| pSH17-N41 | malK820 | L86F mutant | 2 | 23 |

| pSH17-N7 | malK822 | E306K mutant | 4 | 15 |

| pSH17-N18 | malK824 | P160L mutant | 1 | 20 |

| pSH17-N24 | malK825 | D65N mutant | 2 | 16 |

Cells of strain ES25 transformed with the described plasmids were grown at 37°C in the absence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The control value (100%) corresponds to 1.3 nmol min−1 109 cells−1. Data are the averages of at least two experiments.

FIG. 2.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of purified MalK wild-type and mutant proteins. A total of 5 μg of protein was loaded in each well, electrophoresed, and stained as described in reference 17. Lanes: 1, molecular mass standards; 2, wild type, prepared as described in reference 19; 3, L86F mutant; 4, wild type, prepared as described in reference 16; 5, P160L mutant; 6, D165N mutant; 7, wild type (His6-MalK); 8, His6-E306K mutant.

None of the substitutions eliminated the repressing activity of the MalK variants on MalT-dependent gene expression, as analyzed by assaying β-galactosidase activity of strain SK1280 transformed with the plasmid-borne mutant alleles. Strain SK1280 carries a chromosomal malK-lacZ fusion that results in a maltose-negative phenotype but places the lacZ gene under the control of the pmalK promoter (8). Similar to the wild type, the mutant alleles substantially reduced expression of the lacZ fusion (Table 1).

Analysis of nucleotide-binding activity in membrane vesicles.

To further elucidate the functional defects of the mutant proteins, we first tested for their capability to bind nucleotides. To this end, inside-out membrane vesicles were prepared from cells of strain ES25 transformed with the respective derivatives of pSE380 and subjected to photo-cross-linking with the ATP analog [γ-32P]N3-ATP as described in reference 19. Results from such an experiment demonstrated that all variants reacted with the probe (not shown). Quantitation by densitometric scanning of the autoradiographs revealed that the mutant proteins incorporated between 48 and 92% of the label relative to the wild type. Preincubation of the samples with excess unlabeled ATP resulted in a substantial reduction of photo-cross-linking, indicating the specificity of the reaction. Thus, it is concluded that nucleotide-binding activity was basically retained in each mutant protein.

Biochemical properties of purified MalK variants.

Next, the effects of the mutations on ATP-induced conformational changes and on ATPase activity were investigated for the purified proteins (Fig. 2). The L86F, P160L, and D165N mutants were purified by published methods (16, 19) from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) carrying derivatives of plasmid pES67 (16). In the case of the P160L mutant, the strain additionally harbored plasmid pOFX-T7-SL1, which encodes the E. coli GroESL chaperones (2), to increase the amount of soluble protein. The E306K mutant was purified as an N-terminal hexahistidine fusion from strain BL21(DE3)(pOFX-T7-SL1) carrying the respective derivative of plasmid pGS91-1 (14) by red agarose chromatography (16), followed by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Wild-type MalK was isolated by any of these methods, using plasmids pES67 (16) and pGS91-1 (14).

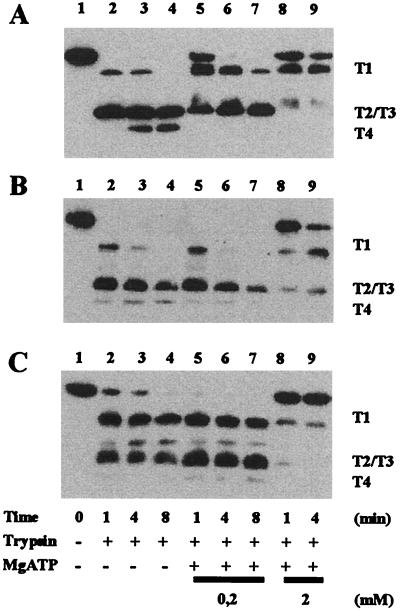

The purified proteins were subjected to limited proteolysis with trypsin to monitor a conformational change upon interaction with MgATP (18). Representative results from such an experiment are shown in Fig. 3. Typically, MalK is rapidly cleaved at R66, R146, R153, and R185 into four major, transiently occurring peptide fragments (T1 to T4) (18). Increasing concentrations of MgATP stabilize mature MalK and fragment T1 (Fig. 3A). Thus, binding of the nucleotide renders potential cleavage sites less accessible to the protease, indicating a change in protein tertiary structure. The L86F, P160L, and D165N variants displayed similar fragment patterns except that resistance to trypsin required the presence of 2 mM MgATP (Fig. 3B; data shown for L86F only), suggesting that the mutations somewhat lowered the affinity of the proteins for the nucleotide. In contrast, the peptide fragments obtained from the E306K mutant exhibited intrinsic resistance against further degradation that was unaffected by 0.2 mM MgATP. However, 2 mM MgATP substantially protected the mature form of the protein against the protease (Fig. 3C). Although the mutation created a potential new tryptic cleavage site, no change in the apparent molecular masses of the accumulated fragments was observed, indicating that the residue is rather inaccessible to the protease. Thus, the data suggest that the mutation might cause a structural alteration of the protein.

FIG. 3.

Limited proteolysis of purified MalK variants. Mutant proteins were digested with trypsin at a concentration of 48:1 (by weight) in the absence or presence of ATP. Samples were withdrawn at the indicated times and subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting as described previously (18). (A) Wild type, prepared according to reference 16; (B) L86F mutant; (C) E306K mutant. The relative positions of the previously recognized major cleavage products (T1 to T4) (18) are indicated. Fragments T2 and T3 were not separated under the conditions used here. Lane 1, undigested control. Results from representative experiments are shown.

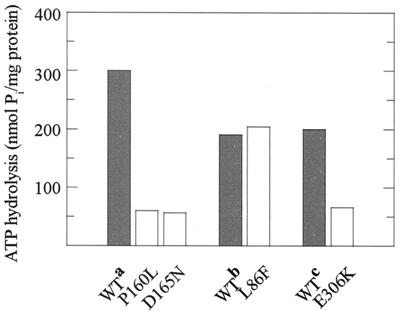

Analysis of the ATPase activities of the purified variants, carried out as described elsewhere (10), revealed reduced rates of hydrolysis for the P160L, D165N, and E306K variants relative to the corresponding wild-type preparations (Fig. 4). Thus, the data provide a reasonable explanation for the failure of these mutant proteins to support maltose transport in vivo. In contrast, the ATPase activity of the L86F protein compared favorably to that obtained with the wild type (Fig. 4), giving rise to the hypothesis that the effect of the mutation may become evident only in the assembled transport complex.

FIG. 4.

ATPase activity of purified MalK variants. Assays were performed as described previously (10). Rates of hydrolysis are compared to those recorded with wild-type (WT) proteins that were prepared by the same protocol. WT proteins were purified from the soluble fraction of strain BL21(DE3)(pLysS, pES67) (16) (a), from the insoluble fraction of the same strain by a denaturation-renaturation protocol (19) (b), and from the soluble fraction of strain BL21(DE3)(pGS91-1, pOFX-T7-SL1) by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose chromatography (c). The data are the averages of at least two independent assays.

ATPase activity of mutant transport complexes in proteoliposomes.

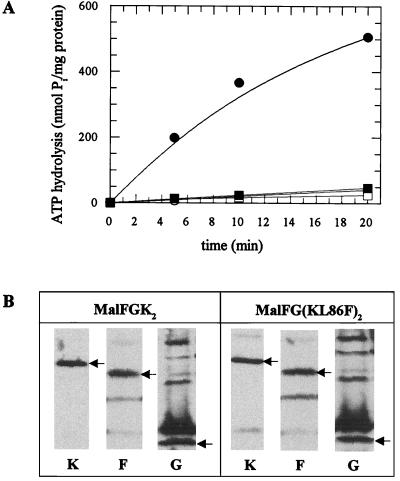

To test the above notion, we analyzed the maltose-binding protein (MalE)-maltose-stimulated ATPase activity of the mutant transport complex incorporated into liposomes. To this end, wild-type and mutant transport complexes were solubilized with octylglucoside (1.5%) from membranes of strain ES54 (ΔatpB-D), harboring pES62-97 (malF malG under the control of the trc promoter) (7) and pGS91-1 (malK+) (14) or pSH60-N41 (malK820). Subsequently, solubilized proteins were mixed with sonicated soybean phospholipids in the presence or absence of maltose and purified MalE (7) and proteoliposomes were formed by detergent dilution according to reference 3. ATPase activity of proteoliposomes was monitored as described previously (19). As shown in Fig. 5A, the mutant transport complex containing the L86F variant exhibited <10% of the enzymatic activity monitored with a wild-type complex. By immunoblot analysis using polyclonal antisera raised against MalK, MalF, and MalG, it was confirmed that comparable amounts of complex proteins were solubilized (Fig. 5B) and recovered in the proteoliposomes (not shown). These data are consistent with the above hypothesis.

FIG. 5.

(A) ATPase activity of the complex containing the MalK L86F variant incorporated into liposomes. Proteoliposomes containing wild-type or mutant transport complexes were formed in the presence (filled symbols) or absence (open symbols) of maltose and maltose-binding protein (MalE) and assayed for ATPase activity as described in reference 7. Symbols: ○ and ●, wild-type complex; □ and ■, MalFG(KL86F)2. (B) Immunochemical detection of the individual subunits in the octylglucoside-solubilized fractions from membranes containing wild-type or mutant complexes. The reactions corresponding to MalK (K), MalF (F), and MalG (G) are indicated by arrows.

In addition, mutant transport complexes containing the MalK P160L or E306K variant were analyzed by the same protocol to serve as additional controls. As expected from the results obtained with the purified subunits, the proteoliposomes displayed ATPase activities of 4% (P160L) and 17% (E306K) relative to the wild type.

Potential implications on function and domain structure of MalK.

P160 and D165 immediately succeed the Walker B motif of the nucleotide binding site encompassing the invariant aspartate 158, which is essential for ATP hydrolysis (14) (Fig. 1). While P160 is conserved only in some bacterial import systems and in both nucleotide binding domains of the mammalian CFTR protein, D165 is almost invariant in the ABC family overall (15). The crystal structure of the bacterial ABC protein HisP revealed that the corresponding residues (P180 and D185) are not involved in ATP ligation (6), which is consistent with our observation that the mutations did not eliminate nucleotide binding. Nonetheless, our data suggest that both residues are crucial for catalysis.

From the biochemical analysis of the L86F protein, it is tempting to speculate that the mutation might prevent the variant from becoming activated as a consequence of conformational changes initiated by maltose-loaded MalE. If so, this would imply that L86 and possibly neighboring residues participate in subunit-subunit interactions in the transport complex. The recent finding that A85 of MalK, when mutated to methionine, acted as a suppressor of mutations in a conserved peptide loop (“EAA loop”) in the E. coli MalF and MalG proteins is at least not contradictory to this notion (11).

E306 is localized to the C-terminal extension of the protein that is confined to the MalK subfamily of bacterial and archaeal ABC proteins (1, 5, 21). E306 is embedded within a conserved short sequence motif (consensus, vxvVExxG) of unknown function. Substitution by lysine resulted in a protein with a substantially reduced ATPase activity. Since a direct role of the residue in ATP hydrolysis is unlikely, the catalytic site might rather be affected by an altered protein structure. The tryptic cleavage pattern that differs from the wild type provides some evidence in favor of this notion. In this respect, it is also interesting that mutations (S295N and V305I) affecting residues in the same region of LacK, the MalK homolog of the ABC transporter for lactose in Agrobacterium radiobacter, improved the capability of certain LacK variants to substitute for MalK in maltose transport (21; M. Brinkmann, F. Scheffel, C. Brunkhorst, S. Hunke, and E. Schneider, unpublished results).

The finding that the E306K variant has retained the repressor-like activity of MalK on other maltose-regulated genes is somewhat unexpected, because in E. coli MalK aspartate substituting for G302 (corresponding to G300 in the serovar Typhimurium protein) abolished this function (8). Thus, the regulatory activity appears to be dependent on the presence of particular amino acid residues, while even nearby substitutions with structural implications are tolerated.

In summary, the mutations described in this report add to our knowledge of the structure-function relationship of the proposed domains of MalK and related proteins. In particular, the phenotype of a mutation, E306K, supports the notion that in the native protein the N- and C-terminal domains both affect the proper folding of the polypeptide chain (13).

Acknowledgments

We thank Birgit Sattler for excellent technical assistence, Oliver Fayet (Toulouse, France), for providing plasmid pOFXT7-SL1, and Beth Traxler (Seattle, Wash.) and Elie Dassa (Paris, France) for generous gifts of MalF and MalG antisera, respectively.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHN 271/6-1,6-2) and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boos W, Shuman H. Maltose/maltodextrin system of Escherichia coli: transport, metabolism, and regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:204–229. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.204-229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castanié M-P, Bergès H, Oreglia J, Prére M-F, Fayet O. A set of pBR322-compatible plasmids allowing the testing of chaperone-assisted folding of proteins overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Anal Biochem. 1997;254:150–152. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson A L, Nikaido H. Overproduction, solubilization and reconstitution of the maltose transport system from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4254–4260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson A L, Shuman H A, Nikaido H. Mechanism of maltose transport in Escherichia coli: transmembrane signalling by periplasmic binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2360–2364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greller G, Horlacher R, DiRuggiero J, Boos W. Molecular and biochemical analysis of MalK, the ATP-hydrolyzing subunit of the trehalose/maltose transport system of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20259–20264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hung L-W, Wang I X, Nikaido K, Liu P-Q, Ames G F-L, Kim S-H. Crystal structure of the ATP-binding subunit of an ABC transporter. Nature. 1998;396:703–707. doi: 10.1038/25393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunke S, Dröse S, Schneider E. Vanadate and bafilomycin A1 are potent inhibitors of the ATPase activity of the reconstituted bacterial ATP-binding cassette transporter for maltose (MalFGK2) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;216:589–594. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kühnau S, Reyes M, Sievertsen A, Shuman H A, Boos W. The activities of the Escherichia coli MalK protein in maltose transport, regulation, and inducer exclusion can be separated by mutations. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2180–2186. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2180-2186.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippincott J, Traxler B. MalFGK complex assembly and transport and regulatory characteristics of MalK insertion mutants. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1337-1343.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morbach S, Tebbe S, Schneider E. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter for maltose/maltodextrins of Salmonella typhimurium. Characterization of the ATPase activity associated with the purified MalK subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18617–18621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mourez M, Hofnung M, Dassa E. Subunit interactions in ABC transporters. A conserved sequence in hydrophobic membrane proteins of periplasmic permeases defines an important site of interaction with the ATPase subunits. EMBO J. 1997;16:3066–3077. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panagiotidis C H, Boos W, Shuman H A. The ATP-binding cassette subunit of the maltose transporter MalK antagonizes MalT, the activator of the Escherichia coli mal regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:535–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmees G, Schneider E. Domain structure of the ATP-binding-cassette protein MalK of Salmonella typhimurium as assessed by coexpressed half molecules and LacK′-′MalK chimeras. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5299–5305. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5299-5305.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmees G, Stein A, Hunke S, Landmesser H, Schneider E. Functional consequences of mutations in the conserved “signature sequence” of the ATP-binding-cassette protein MalK. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:420–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider E, Hunke S. ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) transport systems: functional and structural aspects of the ATP-hydrolyzing subunits/domains. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider E, Linde M, Tebbe S. Functional purification of a bacterial ATP-binding cassette transporter protein (MalK) from the cytoplasmic fraction of an overproducing strain. Protein Expr Purif. 1995;6:10–14. doi: 10.1006/prep.1995.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider E, Walter C. A chimeric nucleotide-binding protein, encoded by a hisP-malK hybrid gene, is functional in maltose transport in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1375–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider E, Wilken S, Schmid R. Nucleotide-induced conformational changes of MalK, a bacterial ATP binding cassette transporter protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20456–20461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter C, Höner zu Bentrup K, Schneider E. Large-scale purification, nucleotide binding properties and ATPase activity of the MalK subunit of S. typhimurium maltose transport complex. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8863–8869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter C, Wilken S, Schneider E. Characterization of site-directed mutations in conserved domains of MalK, a bacterial member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family. FEBS Lett. 1992;303:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80473-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilken S, Schmees G, Schneider E. A putative helical domain in the MalK subunit of the ATP-binding-cassette transport system for maltose of Salmonella typhimurium (MalFGK2) is crucial for interaction with MalF and MalG. A study using the LacK protein of Agrobacterium radiobacter as a tool. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:555–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]