Abstract

Rural Latinx immigrants experienced disproportionately negative health and economic impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic. They contended with the pandemic at the intersection of legal status exclusions from the safety net and long-standing barriers to health care in rural regions. Yet, little is known about how rural Latinx immigrants navigated such exclusions. In this qualitative study, we examined how legal status stratification in rural contexts influenced Latinx immigrant families’ access to the safety net. We conducted interviews with first- and second-generation Latinx immigrants (n = 39) and service providers (n = 20) in four rural California communities between July 2020 and April 2021. We examined personal and organizational strategies used to obtain economic, health, and other forms of support. We found that Latinx families navigated a limited safety net with significant exclusions. In response, they enacted short-term strategies and practices – workarounds – that met immediate, short-term needs. Workarounds, however, were enacted through individual efforts, allowing little recourse beyond immediate personal agency. Some took the form of strategic practices within the safety net, such as leveraging resources that did not require legal status verification; in other cases, they took the form of families opting to avoid the safety net altogether.

Keywords: COVID-19, Immigrant, Legal status, Rural, Safety net, Latinx health

1. Background

Latinx immigrants and their families experienced disproportionately negative health and economic impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic (Martinez et al., 2021; Romano et al., 2021). Both foreign- and US-born Latinxs experienced high rates of COVID-19 and job loss and financial hardship in the first year of the pandemic (Krogstad and Lopez, 2020; Orozco Flores et al., 2020; Orozco Flores and Padilla, 2020). Evidence suggests that Latinx immigrants in rural and agricultural communities were uniquely vulnerable to these negative health and economic impacts (Kaufman et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2020). Immigrant inequities, such as exclusionary immigration policy and legal status stratification, contributed to conditions which put Latinx immigrants in a vulnerable position during the pandemic (Gil et al., 2020; Kiester and Vasquez-Merino, 2021). Latinx immigrants entered the pandemic with limited access to health care and other resources, exclusions from various safety net programs, and little economic security (Broder et al., 2021; Fox, 2016; Mueller et al., 2021). In rural regions, these conditions were likely compounded by the long-standing barriers to health and social services due to provider shortages and disinvestment in the safety net (Lahr et al., 2021). Yet, little is known about the experiences of rural Latinx immigrants during the pandemic and how they contended with these inequities as they sought resources and relief. In this paper, we examine how legal status stratification within rural contexts influenced Latinx immigrant families’ access to and exclusion from the health and economic safety net. Through our findings, we discuss the concept of workarounds, showing that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Latinx families and safety net providers in rural communities were largely left to enact individual strategies and practices to meet their basic needs. Despite enacting individual agency, families and organizations were unable to alter the structural conditions of rural safety nets and legal status exclusions from the safety net.

1.1. Experiencing the pandemic within rural communities

During the pandemic, Latinx immigrants and other residents of rural communities experienced unique health and economic vulnerabilities (Lahr et al., 2021; Mueller et al., 2021). Compared to urban and metropolitan residents, all rural residents were at greater risk of experiencing severe COVID-19 outcomes due to factors such as limited hospital capacity and existing health inequities (Cuadros et al., 2021; Henning-Smith et al., 2020; Kaufman et al., 2020). The persistent healthcare provider shortages and underfunded safety nets meant that rural residents had access to fewer resources to weather the health and economic impacts of the pandemic. For example, rural areas had limited access to COVID-19 testing and vaccine supply (Murthy et al., 2021; Souch and Crossman, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, Latinx immigrants who lived in rural communities contended with immigration-related exclusions from the safety net (Broder et al., 2021). They were also more likely to live in poverty, be employed in agriculture, and experience under-employment compared to their rural US born or urban Latinx counterparts (Jensen et al., 2009; Ramirez and Don, 2012). Understanding the pandemic's health and economic impact on rural Latinx immigrant families requires examination of the contexts of rural communities and their safety nets, as well as the exclusions produced by legal status stratification.

1.2. Rural communities as contexts of reception for Latinx immigrants

Foreign- and US-born Latinxs are the fastest growing demographic group in rural communities across the US (Crowley et al., 2015). Rural communities are critical “contexts of reception” for many Latinx immigrants, where the implications of legal status are shaped by local policies, institutions, and social attitudes (Golash-Boza and Valdez, 2018; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001). Immigrant legal status constitutes a social determinant of health that stratifies individuals along legal, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic lines of exclusion (Menjivar, 2013). Immigrants' legal status formally influences their rights, such as eligibility for publicly-funded social safety net programs (Castañeda et al., 2015; Wallace et al., 2019). For example, the undocumented are ineligible for Medicaid and unemployment insurance (Broder et al., 2021). The immediate social and economic implications of these formal exclusions are shaped by the contexts of reception in the US’ diverse rural communities (Miller and Vasan, 2021).

Rural communities possess unique economic, social, and political characteristics (Lichter and Brown, 2011). They have agricultural labor markets in which Latinx immigrants have historically been exploitable labor (Barcus and Simmons, 2013; Cheney et al., 2018; Ramirez and Don, 2012). In rural labor sectors, such as agriculture, Latinx immigrants may not receive paid time off to seek care (Kiester and Vasquez-Merino, 2021). Attitudes in rural communities towards immigrants' “deservingness” of public benefits shape immigrants’ willingness to seek health care (Cheney et al., 2018; Willen, 2012). As a result, for example, Latinx immigrants in rural communities have long had high uninsured rates (Miller and Vasan, 2021). These rural factors can result in inequitable experiences receiving needed care (Van Natta et al., 2019), as well as distrust of health care and other social services institutions (Saadi et al., 2020; Yang and Hwang, 2016).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, legal status remained a critical determinant of access to health and economic resources for immigrants and their families, and likely compounded existing rural barriers to safety net resources (Kiester and Vasquez-Merino, 2021; Obinna, 2021). In federal and state policies, legal status was a criterion for pandemic aid eligibility. Table 1 describes select federal and state financial, health, and nutrition programs for citizens and eligible noncitizens. Although legal status is an individual-level category, many programs disqualified entire households if one household member was ineligible (i.e., if they lacked a Social Security Number (SSN)). As a result, during the pandemic, legal status also functioned as a family-level determinant of access to resources. In California, some cash aid was made available to undocumented residents, but funds were limited (Garcia, 2020). In addition, in 2019, the Homeland Security Department expanded the criteria for designating permanent residency applicants inadmissible on public charge grounds. Under the 2020 public charge rule, some non-cash safety net resources were considered in determining whether a permanent resident applicant may become a public charge (USCIS, 2021). Although these changes were rescinded in 2021 shortly after going into effect, the original announcement of the public charge rule already had chilling effects among Latinx families (Barofsky et al., 2020). For example, while rental and utility assistance programs generally did not require legal status verification, (Bernstein et al., 2021, Clark et al., 2020), over 25% of low-income immigrants avoided these programs due to public charge concerns. Little is known, however, about how these legal status exclusions influenced Latinx immigrant families as they navigated limited rural safety nets.

Table 1.

Select COVID-19 federal and state pandemic relief programs, 2020–2021.

| Pandemic relief program | Description | Implications for mixed status families |

|---|---|---|

| Federal Aid | ||

| Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, 2020 |

|

|

| Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 |

|

|

| American Rescue Plan, 2021 |

|

|

| California | ||

| California Golden State Stimulus |

|

|

| Coronavirus (COVID-19) Disaster Relief Assistance for Immigrants |

|

|

| Pandemic EBT |

|

|

Sources.

Garcia, J. Financial help for California's undocumented immigrants starts Monday. Cal Mattershttps://calmatters.org/california-divide/2020/05/financial-help-available-californias-undocumented-immigrants-monday/(2020).

Immigrant Eligibility for Public Programs During COVID-19. Protecting Immigrant Familieshttps://protectingimmigrantfamilies.org/immigrant-eligibility-for-public-programs-during-covid-19/(2021).

USDA Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP Policy on Non-Citizen Eligibility. Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP)https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility/citizen/non-citizen-policy (2013).

What to know about all three rounds of coronavirus stimulus checks. Peter G. Peterson Foundationhttps://www.pgpf.org/blog/2021/03/what-to-know-about-all-three-rounds-of-coronavirus-stimulus-checks (2021).

Federal Provisions for Unemployment. Employment Development Departmenthttps://edd.ca.gov/about_edd/coronavirus-2019/cares-act.htm#MEUC (2021).

State of California Franchise Tax Board. Golden State Stimulus Ihttps://www.ftb.ca.gov/about-ftb/newsroom/golden-state-stimulus/gss-i.html (2021).

Merced County Office of Education. Documenting P-EBT Implementation in California. (2020).

1.3. Study objectives and context

The impact of how safety net policies and legal status exclusions unfolded in rural contexts can be observed in California where, as of September 2021, Latinxs constituted less than half of the state's population but accounted for over half of the state's coronavirus-2 infections and nearly half of COVID-19 related deaths (Despres, 2021). California has led the nation in policies to extend the safety net to noncitizens (Wallace et al., 2019). Yet, undocumented immigrants throughout the state continue to have lower levels of access and utilization of health care (Bustamante et al., 2019) and the implementation of federal and state policies may vary in rural regions due to their distinct political environments (Cheney et al., 2018; Martin and Calvin, 2010; Miller and Vasan, 2021). For example, agricultural counties like Merced and Tulare – included in the current study – resisted compliance with state policies to limit law enforcement collaboration with immigration officials (Romani, 2022). There is less known about how rural contexts may influence the implementation of safety net policies.

In this qualitative study, we used the intersecting lenses of rurality and legal status to examine how Latinx immigrant families navigated the rural economic, health, and social safety net as they attempted to weather financial precarity, sought critical resources, and contended with exclusions and barriers during the pandemic. We sought multiple perspectives to understand the intersecting implications of rural contexts and legal status. We conducted in-depth interviews with first-generation Latinx immigrants, who experienced immediate impacts from their legal status; second-generation US Latinx adults who, as members of mixed-status families, may have experienced the “spillover effects” of family members’ legal status; and safety net service providers in rural communities who worked to enroll and provide resources to Latinx immigrant families.

2. Methodological considerations in conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic

This study unfolded over the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our approach was informed by the circumstances of the time: rapidly rising infection rates, major economic downturn, and a sense of both urgency to understand the consequences of the pandemic and caution in conducting research among an impacted population. The study, therefore, was not guided by a single epistemological framework but aimed to capture authentic descriptions of the phenomenon and interpretations of these descriptions in the context of the pandemic in rural communities (Kahlke, 2014). We sought to embrace inconsistencies across narratives and deprioritize analytical outcomes, allowing a flexible approach that prioritized organic descriptions of the phenomenon (Sandelowski, 1993).

Our research team members lived and worked in rural California counties during the time of the study and had personal and professional connections to rural Latinx immigrant communities. Five team members were first- or second-generation bilingual Latina/e/o/x. The three senior researchers were experts on immigrant health, health policy, and mental health. They had expertise in community-engaged research with Spanish-speaking Latinxs which informed the study design; and possessed established collaborative relationships with community-based organizations in the regions who were invited to join a study advisory board. Three student researchers were born and raised in and had family who worked in the study counties, allowing us to connect and recruit from their personal networks and build trust and rapport with study participants.

3. Study methods

We conducted and analyzed semi-structured interviews with first- and second-generation Latinx adults and representatives from immigrant-serving safety net organizations in four rural counties in California from July 2020–April 2021. The research received approval from the University of California, Merced Institutional Review Board.

3.1. Sampling and recruitment in rural communities

We selected four California counties (Merced, Fresno, Tulare, Imperial), located in the San Joaquin or Imperial Valleys, as study sites (Table 2 ). Because the concept of “rurality” encompasses multiple types of regions (Bennett et al., 2019), we selected counties from which we could sample respondents living in areas defined as rural based on both social and demographic characteristics. First, our advisory board provided input to select four counties because they encompassed Latinx communities that identified as rural. Some of these counties contained urban cores (e.g., City of Fresno) from which we did not want to sample. Therefore, we then reviewed county demographic data to verify that each county had numerous non-metropolitan areas using the Census' Urban Areas and Office of Management and Budget's definitions of “rural” as communities with under 50,000 residents.

Table 2.

Characteristics of selected counties, 2020

| Merced | Fresno | Tulare | Imperial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 281,202 | 1,008,654 | 473,117 | 179,702 |

| % of county Latinx | 53.7% | 52.7% | 65.2% | 82.8% |

| % of county noncitizen | 11.4% | 3.6% | 22.0% | 8.9% |

| % of county below 100% Federal Poverty Level | 31.1% | 28.6% | 25.0% | 17.9% |

| % of county that ever had or thought had COVID-19 | 4.9% | 10.7% | 5.9% | 13.3% |

Sources: 2020 US Census 2020; 2020 California Health Interview Survey.

We used a two-tiered sampling strategy to recruit respondents and key informants from these counties. Respondents (ages 18 years or older) from each county were eligible if they (1) lived in a non-metropolitan area (i.e., under 50,000 residents), (2) identified as Latino, and (3) themselves or a parent were foreign-born. Key informants were eligible to participate if they were personnel at a safety net organization (e.g., food bank, community health center) that served the study counties.

Respondents were recruited through referrals and some advertising. To obtain referrals, advisory board members shared study information with clients to identify interested individuals. Research team members shared study information with friends and family and invited them to refer interested individuals in their networks. In a few cases, following the interview, respondents offered to refer a friend or family member. Finally, we posted some advertisements on social media (e.g., Facebook) and one team member appeared on a podcast in Imperial County. After obtaining contact information, research team members contacted potential respondents by phone, described the study, and screened for eligibility. A pseudonym was assigned to all respondents and identifying information was destroyed.

Key informants were recruited from a list of immigrant-serving agencies and referrals. Through professional networks and internet searches, research team members generated a list of community-based organizations that provided health care, nutrition, legal, employment and other services in the selected counties. After each interview, they also asked key informants to suggest additional organizations. Key informants were emailed and a research team member followed up to describe the study and schedule an interview.

3.2. Data collection

We developed semi-structured interview guides designed to facilitate conversations driven by respondents' and key informants' experiences and concerns. The respondent interview guide was organized around topics related to safety net policy sectors (e.g., employment, economic resources, public benefits, and health care). The key informant interview guide was organized around topics related to safety service provision (e.g., organizations' roles in implementing programs). All interviews began with an open-ended question (e.g., tell me about yourself; describe your organizations' mission) to allow respondents' or key informants’ most salient experiences to emerge. Based on what emerged, the interviewer started the interview with the corresponding topic in the interview guide, moving to other topics as they arose organically during the conversation. For example, if a respondent first spoke about their job, open-ended questions regarding employment were used; if the respondent then mentioned health care, the interviewer moved to health care questions.

Due to pandemic restrictions, all interviews were conducted remotely. Respondent interviews were completed by phone in English or Spanish, July–August 2020 and February–April 2021, and audio recorded (duration: 60–90 min). Respondents answered a brief survey with immigration, socio-demographic, and public benefit use questions and received an electronic $25 gift card. Audio recordings were uploaded to a secure cloud folder and transcribed by an outside vendor. Key informant interviews were conducted in English on Zoom using the program's automatic transcription function (duration: 45–60 min). Transcripts were uploaded to a secure cloud folder and edited by a team member. Following each interview, research team members prepared a memo and met as a group to discuss emerging themes. We conducted interviews until we observed that additional interviews were not yielding new topics or insights, our criteria for achieving saturation of themes.

3.3. Data analysis

We conducted an iterative and sequential process to analyze interview transcripts. We first developed a respondent interview codebook using a purposive selection of 6 transcripts. We reviewed the memos to select interviews encompassing numerous topics and compelling, diverse examples. This sample included four females and two males ages 33–46 who worked in various labor sectors and of which four were undocumented, one was a lawful permanent resident, and one was a U.S. citizen. The team conducted iterative, line-by-line coding of these transcripts to develop an initial list of codes. These were iteratively tested on additional transcripts to refine the codes and group codes into related topics that captured emerging themes. Three team members independently coded all respondent transcripts and met on a weekly basis to discuss discrepancies. We then developed the key informant interview codebook through a top-down approach in which we used the respondent code book as a framework to develop codes for corresponding topics in the key informant interviews. Coding was conducted by a single team member who met weekly with the PI to discuss questions. As coding continued, all team members met to discuss emerging themes and identify the emerging relationships across codes related to job and financial insecurity, limitations of the rural safety net, and leveraging resources in and outside the safety net.

4. Results

The sample included 39 first- and second-generation Latinx immigrant respondents and 20 key informants (Table 3 ). All respondents, except one, were members of extended mixed-status families and about one third were undocumented (n = 14). 68% (n = 25) had ever used Medi-Cal, 54% (n = 20) food stamps, and 27% (n = 10) unemployment insurance. Among key informants, 4 were from food banks, 2 from legal service organizations, 2 from health centers, 2 from employment opportunity agencies, 4 from community engagement agencies, and 6 from civic and advocacy organizations.

Table 3.

Respondent and key informant characteristics.

| Respondents | N = 39 |

|

|---|---|---|

| % or mean (range) | n | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 67% | 26 |

| Male | 33% | 13 |

| Age | 40 (19–70) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 21% | 8 |

| Married or living with partner | 67% | 26 |

| Divorced | 5% | 2 |

| Refused or unknown | 8% | 3 |

| Immigration characteristics | ||

| Country of birth | ||

| Mexico | 72% | 28 |

| United States | 23% | 9 |

| Unknown | 5% | 2 |

| Years living in the U.S. (foreign-born only) | 22 (2–51) | |

| Legal status | ||

| Undocumented | 36% | 14 |

| Lawful permanent resident (LPR) | 10% | 4 |

| U.S. born citizen | 23% | 9 |

| Naturalized | 15% | 6 |

| Refused to answer/unknown | 15% | 6 |

| Have family members or friends who are undocumented | ||

| Yes | 72% | 28 |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 39% | 15 |

| High school or higher | 56% | 22 |

| Unknown | 5% | 2 |

| Household size | 5 (1–8) | |

| Language of interview | ||

| English | 18% | 7 |

| Spanish | 79% | 31 |

| English and Spanish | 3% | 1 |

| Ever used … | ||

| CalWORKS | 8% | 3 |

| Food stamps | 54% | 20 |

| Medi-Cal | 68% | 25 |

| Unemployment insurance | 27% | 10 |

| Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) | 13% | 5 |

| Worker's compensation | 16% | 6 |

| County of residence | ||

| Fresno County | 28% | 11 |

| Imperial County | 26% | 10 |

| Merced County | 21% | 8 |

| Tulare County | 26% | 10 |

| Key Informant Organizations | (N = 20) | |

| Regions served | ||

| Imperial County | 5% | 1 |

| Merced County | 40% | 8 |

| Tulare County | 25% | 5 |

| Multiple | 30% | 6 |

| Sector | ||

| Advocacy | 30% | 6 |

| Community engagement | 20% | 4 |

| Employment | 10% | 2 |

| Food bank | 20% | 4 |

| Health care | 10% | 2 |

| Legal services | 10% | 2 |

1Respondents were screened for the following chronic conditions: asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, lung disease, and obesity.

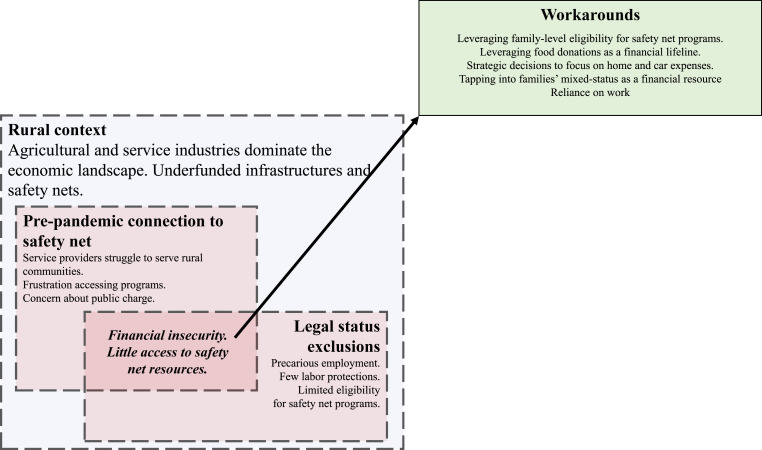

As illustrated in Fig. 1 , the rural context, such as work in agriculture and families' pre-pandemic connections to the safety net, and legal status exclusions from state and federal resources contributed to respondents’ need for safety net resources and how they and key informants navigated limited rural safety nets. In the context of limited safety nets, respondents and key informants enacted agency through individual-, family-, and organizational-level short-term strategies and practices that we refer to as workarounds. While workarounds met immediate, short-term needs, they did not alter the structural barriers and exclusions of the rural safety net.

Fig. 1.

Workarounds: Short-term strategies in and outside of the safety net to overcome the barriers to resources produced by rural contexts and legal status exclusions.

4.1. Navigating financial precarity with limited options for financial relief

Respondents’ need for safety net resources stemmed from employment insecurity and lack of financial resources. Respondents who were undocumented were the most likely to work in agriculture, the service sector, or domestic work – rural labor sectors with significant layoffs in the early months of the pandemic. Agricultural workers said they were laid off due to reductions in exportations and those in restaurant and service jobs lost hours due to decreased client volume. Domestic workers negotiated employment terms with individual clients, and several reported job losses due to COVID-19 cases among clients.

Respondents' described that their financial insecurity was related to exclusion because they were immigrants. For example, after being laid off, numerous respondents reported feeling cast aside when employers failed to follow-up with them. Maria C (Tulare, Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR)), who worked in agriculture through an employment contracting agency, reported: “They never called me back to work.” This was a common experience. After a being told not to come in due to a COVID-19 case at work, Francisco (Merced, undocumented) described: “I was waiting for [my employer's] call for two weeks, three weeks, waiting for their call and they never called.”

Undocumented respondents were acutely aware of their exclusion from financial resources, such as unemployment insurance and the stimulus. Many reported feeling discriminated against. Lily (Fresno, unknown) stated: “They never gave us any of [the stimulus], because we are immigrants. There isn't any financial assistance for us.” No respondents who sought California's one-time financial assistance for undocumented individuals successfully obtained it, describing busy phone lines at every call.

While not excluded due to their legal status, documented respondents still struggled to access sufficient financial resources. The federal stimulus payments provided important but insufficient relief. The application processes for unemployment insurance or employer sick pay was often cumbersome and difficult for monolingual Spanish-speakers to navigate. Alex (Imperial, U.S. born) described helping obtain her father's sick pay, “I was the one that was helping [my dad] because he doesn't really know English or read and write English.” Her family exhausted their savings waiting.

4.2. Navigating safety net policies in a limited rural safety net

Financial precarity and formal exclusions from financial resources led respondents to seek local resources. Key informants, however, faced structural limitations that hindered their ability to meet the needs of Latinx immigrant families in their rural communities. As a result, respondents’ previous connections to local safety net emerged as a salient determinant of their access to resources.

A greater burden to providing and accessing services for immigrants in rural communities. Key informants described that their organizations’ missions were to support underserved populations in rural communities; however, they consistently reported challenges to meeting community needs. It was difficult to serve small, remote communities on limited budgets, resulting in an unequal distribution of resources across service areas. A key informant from a food bank explained:

Trying to make sure that we're getting out to the rural communities and serving them like they need is almost impossible. It takes us extra gas, extra wear and tear on our vehicles, extra staff time to be able to go out to those communities. We try to be equitable about the ways that we serve the communities.

Respondents described this lack of resources in their rural communities. They said that public transportation services were absent or unreliable, resulting in the financial burden of maintaining a car. For example, residents in Imperial County often had to travel to San Diego for health care. Adriana (Imperial, undocumented) was able to obtain medical transportation to specialty services for her daughter, whereas Choco (Imperial, U.S.-born) relied on family members for rides to cancer treatments.

Respondents, such as Claudia (Imperial, U.S.-born), were aware that programs existed in urban counties that were unavailable in their own: “My cousin told me about Renters Assistance or whatever, but she's from Los Angeles. We don't have that.” Rosa A (Merced, LPR) only found mental health services for her sister through a faith-based organization in Los Angeles County conducting online support groups.

Confusion and frustration with the complexity of accessing overwhelmed safety net programs. As respondents sought to access services, they grappled with complex legal status eligibility requirements that limited resource options and time-consuming enrollment processes that often deterred them from continuing to seek resources. Respondents commonly expressed frustration or disappointment when unable to access programs after multiple attempts. They had difficulty reaching agencies by phone and, even after speaking with someone or submitting an application, did not receive follow-up information. Maria A (Merced, undocumented), describing the state's cash aid program for undocumented residents, lamented: “The agencies are giving out money, but they never get your call. You call, call, call … When I called, they said, ‘If you are calling for economic relief during the pandemic, we no longer have funds available.’” Because of negative experiences with enrollment processes, many ceased further attempts or avoided programs altogether.

Legal status eligibility requirements and enrollment processes detracted from key informants’ already limited resources. Legal status eligibility requirements from governmental and private funding restricted who they could serve. A legal services provider described, they often had to refer undocumented clients to other providers:

It’s heart wrenching sometimes. Then we never know if that person is going to follow up. We can help set the appointment. We can remind them about that appointment. That's what we refer to as a warm handoff. But we can't make them go, right?

A key informant stated that “‘immigrant’ pretty much covers everybody we serve,” reflecting that most key informants dedicated limited resources to supporting immigrant clients navigate enrollment processes. A key informant from Merced County described:

It is ends up being a lot more work and a lot more bureaucracy … You're helping that family and 10 more people have called … If the real goal of this legislation is get the economy moving and get this money on the ground and help all these people, then why can't we trust people more?

The policies that rendered respondents ineligible due to legal status also posed a bureaucratic burden to key informants, who dedicated resources to implement enrollment protocols, but further limited their ability to serve additional clients.

Pre-pandemic connections to the health care safety net. Prior to the pandemic, numerous respondents of all legal statuses had a source of health care or received nutrition assistance. Respondents with established safety net connections faced barriers to resources, but these stemmed from the challenges of disruptions in existing services. They encountered office closures and cancelled appointments. Adriana (Imperial, undocumented) shared that her daughter's cleft palate treatment was delayed when the only surgeon closed their office. Both respondents and key informants described the new challenges posed by virtual services, such as virtual medical appointments, that often lead to delayed or foregone care. These respondents, however, had overcome legal status exclusions or concerns about using safety net services prior to the pandemic.

In contrast, respondents not previously connected to safety net programs faced insurmountable barriers to establishing new connections or services. Concerns about their legal status resulted in hesitancy to initiate health services or nutrition assistance. For example, Juana, (Fresno, undocumented), refused to enroll in a nutrition assistance program over public charge concerns:

Well up until now I haven’t used the stamps. I say no, not because I don’t want to, but because we are trying to see if there's an opportunity for my son to help us submit an application [for residency]. And now you see Trump saying that everything is a public charge, right?

Key informants identified public charge as a major barrier to serving clients. One described their clients' confusion: “I don't think our immigrant population ever really understood what makes you a public charge … because they get all [the same services] at the same office. Public charge did not help us.” Numerous key informants sought to educate the community about the rules:

We invite different partners help educate our residents … and to empower them and to not be afraid to speak up and to connect them with resources that they will need. One of them is public charge and how CalFresh is not part of what we call the welfare system, so that people will not starve.

While all respondents faced limited options for safety net resources in rural communities, legal status posed a central concern specifically for those not previously connected to these programs.

4.3. Working around the exclusions in rural financial, health, and social services safety nets

When faced with barriers, confusion or frustrations within these systems, both respondents and key informants engaged in workarounds (Fig. 1), including strategic practices within the safety net to access resources, tapping into resources outside the safety net to cover family expenses, and opting to avoid specific services altogether.

Leveraging family-level eligibility for safety net programs. Strategic practices within the safety net allowed respondents and key informants to connect to resources through families' mixed-status legal statuses. Many respondents leveraged an eligible spouse's or child's access to resources to meet household expenses. For example, Rogelio (Tulare, undocumented) shared that his children received pandemic EBT which was “a huge help, considering that the famous stimulus check didn't give us anything.” Respondents described family decision-making to patch together resources based on each family members' eligibility. Daniel's (Tulare, undocumented) description illustrates the patchwork that families juggled:

[The Pandemic EBT] was $360 for each child under 18 years; because [my wife and I] don’t qualify for the other help of $1200 or that of $500 for each child from the state, and since we are undocumented and the kids were born here, but they didn’t qualify for the $500. The only one who did qualify was my 21-year-old daughter who is in school and has DACA.

Similarly, key informants reported efforts to connect entire households to resources through eligible family members:

When [clients] come in for utility assistance and their child has a social security number, we only need it for one person in the household. We operate very broadly, don't ask, don't tell kind of situation. Where the programs that do require some form of citizenship, we only do that for one person in the household.

While this widespread strategy provided families with a needed infusion of resources, it further reinforced how Latinx immigrant families were left to make do with limited resources.

Leveraging food donations as a financial lifeline. Respondents reported prioritizing low-barrier safety net resources that did not have legal status eligibility requirements. They sought food resources like donation boxes because they were available with minimal eligibility requirements. As Rosa B (Tulare, naturalized citizen) describes, “There, they don't ask you for anything. You only go in your car and they put it in there. You just put down your name and where you live, how many in the family. They don't ask for anything else.”

Maria B (Merced, undocumented) described how her family used food boxes instead of food stamps because of public charge concerns:

It seems to me [my husband] has always had that fear, so we’ve never gotten food stamps. We only go where they don’t ask for documentation and they only ask for the basics. I know there are means by which my kids could eat better, but I don’t risk it, since everything is in [my husband’s] name and I’d have to give his information.

A key informant described their process for food distributions

[Clients] sign their name, but they can write whoever they want to like, Mickey Mouse. We're not the food police. We don't care. They self-certify that they're low income … that makes them eligible to receive that food from the USDA.

Because many food programs offered this accessibility, food resources emerged as a key resource that gave families flexibility to redirect cash to their financial priorities. Respondents described food resources as means to save money. Juana (Fresno, undocumented) explained: “I go out to look for [food boxes] to help me a bit and that way I save my money for bills.” Choco (Imperial, U.S. born) similarly, shared: “They give you cans with fruit, cheese, beans, and lots of things. There you save $20, $30 off the shopping list.” As a result, respondents were able to enact agency to strategically access some resources and pursuing options outside the safety net.

Strategic decisions to focus on home and car expenses. Respondents were only able to obtain relatively small and nominal amounts of support through safety net programs – and only after contending with eligibility requirements and enrollment processes. As a result, workarounds also took the form of families opting to avoid specific programs altogether. In some cases, this was out of a desire to show independence or demonstrate their ability to preserve their financial reputation. Adriana B (Imperial, undocumented) was offered informal rent flexibility by her landlord but described with pride that she and her husband opted to make timely payments: “For the rent, our landlord told us not to worry if we paid a bit late, but we always made our payments.” Others decided to prioritize paying utility bills out of concern that there would be consequences from late payments, even from utility companies were offering payment plans. For example, Juan (Fresno, LPR) expressed concern that his utilities would be cut, even if enrolled in a payment program: “If I don't pay, they'll cut services.”

In most cases, however, respondents chose not to seek safety net programs simply because there were too many barriers to programs that, ultimately, failed to provide sufficient resources to meet respondents’ greatest expenses: paying rent and maintaining a car. Almost all respondents reported rent and car payments constituted their largest expenses. Respondents reported that rents were high, despite living in more affordable rural communities. Because they lived in remote, rural communities, they needed cars to get to work and healthcare. As Adriana (Merced, undocumented) put it, “If we lose the truck, how will [my husband and son] get to work?” These financial obligations far surpassed the limited resources that could obtained through safety net programs, making it a burden to navigate complex enrollment processes or to risk being a public charge. Absent an infusion of financial support from the federal stimulus payments, respondents made strategic decisions to focus on maintaining their standing as renters and creditors and maintaining cars over seeking out additional safety net resources.

Tapping into families' mixed-status as a financial resource. Because many financial needs could not be addressed through safety net programs, respondents sought financial resources through family members whose legal status permitted them to make credit card purchases or take out loans, as well as have access to stable employment options. For example, because of their reliance on cars, numerous respondents arranged for family members with SSNs to take out a loan. This gave them access to lower interest rates, but resulted in stress about making payments and not harming a family member's credit. Adriana's (Merced, undocumented) describes her experience:

Because we don’t have legal status here, we got the truck with my sister-in-law’s credit. And the one I drive, my son got it because a cousin has the loan and we pay her. It’s a big pressure to not leave them bad off. If we don’t make the payment, it affects their credit.

Multiple respondents turned to U.S.-born, young adult children for assistance. Luis's (Fresno, naturalized citizen) household stayed afloat because a son began contributing income. Similarly, Karina (Fresno, naturalized citizen) described: “Right now it's my son who just graduated who helps me a bit. He helps with the water and other bills. Without him, imagine—I'd have been unable to pay rent.” Many of the U.S.-born respondents reported making careful decisions about personal finances so they could contribute to family expenses. In Randy's (Imperial, U.S. born) case, supporting his family required meticulous budgeting. He explained:

Basically, it’s come down to rationing my meals. I have this much coming in this month for food stamps, and I have this much left from my money. How much do I spend on my own food? And how much do I give to my parents?

By leveraging access to financial resources and employment opportunities, respondents found options for meeting needs that could not be addressed by safety net programs. This resulted, however, in additional family pressures and financial responsibility on documented family members, who were often younger members of the family.

Reliance on work. While the above strategies provided some relief, returning to work was the most reliable workaround for respondents. As agriculture and service sector activities resumed, returning to the very jobs that had contributed to their financial insecurity was often the primary means by which respondents could exert person agency to meet their family's financial needs. This meant returning to industries with limited COVID-19 protections. Juan (Fresno, LPR) weighed his safety concerns against financial pressures:

These are major concerns, because, firstly, due to [COVID] illness, one wants to protect their health. But one also worries, wondering ‘How am I going to pay this? How am I going to pay that?’ For example, if you don’t pay the car payment, they take it from you. If you don’t pay the rent, they kick you out, onto the street.

Rosa A (Merced, LPR) discussed why her husband needed to return to his job at a beverage import warehouse:

“Well, yes, work is important, [my husband] contributes more to rent and payments. I only work part time and it’s not enough to pay for everything, right? I’ve always told him ‘God willing, nothing will happen to you.’”

Maria C (Tulare, LPR) summed up families’ difficult options: “You either die of hunger or you die of the virus.”

Because working was a critical strategy, respondents described their own health and access to health care in the context of maintaining their well-being as a financial resource. Adriana (Merced, undocumented) shared: “Since we arrived to the US, I've told my kids ‘You can't get sick, I forbid you from getting sick.’ It's so expensive here.” Engaging in prevention through social distancing and personal protective equipment (PPE), was perceived as a strategy to stay healthy for work, not simply for the sake of personal well-being. Numerous respondents reported that using PPE on the job provided them a sense of safety when they were compelled to work. Many reported their employers did not provide PPE and they distrusted their co-workers’ engagement in prevention practices.

As they attempted to stay healthy, respondents personally absorbed the cost of PPE. Jovi (Tulare, unknown) describes how her family balanced existing and new, pandemic-related, expenses: “If we get soap, we use a bit and try not to waste it. But while we've cut back on some items, we now have to get antibacterial gel, cleaning wipes, bleach. Our expenses have gone up.” Respondents had to prioritize their health in order to work, but protecting their health was costly. These costs contributed to the financial challenges they were already facing, continuing a cycle in which they turned to workarounds to overcome legal status exclusions and limited resources in their rural communities.

5. Discussion

In this qualitative study we interviewed first- and second-generation Latinx immigrants and safety net service providers in rural California communities. Through their experiences, we examined the strategies that Latinx immigrant families engaged in to work around limited rural economic and health safety nets and legal status exclusions. Consistent with numerous studies and reports, the pandemic had negative economic and health costs for rural Latinx immigrant communities (Cheng et al., 2020; Young et al., 2020; van Dorn and Sabin, 2020). Both respondents and key informants engaged in workarounds by leveraging family-level eligibility for safety net resources; while many respondents also sought resources outside of the safety net, and, ultimately, returned to workplaces that had limited COVID-19 protections. Our study contributes to knowledge regarding the impacts of the pandemic on rural Latinx immigrant families. As we discuss here, our findings show how rural contexts and legal status stratification reinforced the circumstances that shaped Latinx families’ financial precarity and their exclusion from safety net resources. They also show how Latinx families and safety net providers were left to enact workarounds, individual- and family-level strategies to obtain resources, that could not alter the very conditions that produced their exclusion from the safety net.

First, consistent with research showing that rural communities face barriers to health care and that exclusionary immigration policies also produce barriers (Mueller et al., 2021; Van Natta et al., 2019; Young et al., 2020), we observed numerous cases in which respondents were ineligible for resources directly due to legal status (e.g., federal stimulus) and where key informants struggled to meet needs due to rural factors (e.g., geographic distance). Our findings, however, highlight the importance of understanding immigrant and legal status exclusions in the context of local rural factors. For respondents, what it meant to possess a specific legal status was shaped by living and working in a rural community; while for key informants, what it meant to provide safety net services in a rural community was shaped by their clients' legal status exclusions. For example, many respondents who were undocumented primarily had employment opportunities in agriculture, making them vulnerable to layoffs at the beginning of the pandemic. As they returned to work, the structural conditions of agricultural work then placed them at risk of infection. As evidence mounts that agricultural workers experienced some of the highest COVID-19 mortality rates (Mora et al., 2021), future research should consider how rural contexts and legal status shaped their and other rural workers' vulnerability. The intersections of rural safety nets and legal status exclusions could also be observed in how respondents’ pre-pandemic connections with local safety services shaped their access to resources. For those who had already enrolled in programs, such as Medicaid or nutrition assistance programs, the limitations of the rural safety net was their primary concern, rather than their legal status. In contrast, those who were not connected to such programs had to contend with limited resources and their concern about their legal status. These disconnected families were the most vulnerable to barriers, such as the public charge rule. The intersection of rural contexts and legal status shapes inequities within Latinx immigrant populations. Future research should examine such inequities, such as between those already connected to the safety net and those not connected. Finally, these dynamics were also evident among service providers who experienced the tension between continuing to serve existing clients, particularly in remote rural communities, and the complexity of administering pandemic relief programs with different legal status eligibility criteria. As highlighted in this study, their perspectives help to understand the impacts of exclusionary immigrant policy and should be included in future research.

In response to these exclusions, workarounds offered short-term strategies, but were enacted through individual or organizational efforts, allowing for little recourse beyond individual, family, or staff practices. Workarounds provide important insights into how Latinx immigrant families experienced and made decisions during the pandemic, but also reveal how structural factors continue to produce exclusions from needed resources. One interpretation of our findings is that when the rural safety net is limited and immigration policies are exclusionary, legal status becomes the most salient factor in making decisions about accessing resources and becomes a family-level strategy – used both by families and service providers. Respondents viewed the resources that eligible family members obtained as critical, albeit limited support. This is consistent with research that shows how mixed-status families are excluded from many resources (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2021), but also highlights the need for further understanding of how families make decisions regarding legal status eligibility. For example, through key informants we learned how providers work with clients to connect families to resources via a family member with legal status. These findings align with research on the role of intermediary actors in the health care system, individuals (i.e., friends and family) who distribute the resources they are able to obtain (e.g., medication, medical equipment) to those who encounter barriers to access (Raudenbush, 2020). Our findings show that legal status (or possession of an SSN), similarly, serves as a resource leveraged among Latinx social networks to contend with formal exclusions from safety net programs.

In other cases, workarounds took the form of families opting to avoid specific safety net programs altogether. Another interpretation of our findings is that, left out from limited rural safety nets and explicitly excluded due to legal status, Latinx immigrant families' agency and autonomy are critical resources, but that carry risk for their well-being. Programs with no or limited eligibility requirements ended up serving as a strategy that gave respondents agency to prioritize their needs. For example, food boxes were perceived as a financial, as much as a nutritional, resource. When respondents opted out of other programs, it was often expressed as a desire to show independence or frustration that contending with enrollment or bureaucratic processes were not worth the limited support that could be obtained. While a growing body of literature highlights that immigrants often avoid services out of fear of public charge or immigration enforcement (Barofsky et al., 2020; Touw et al., 2021), our findings also point to a need for further research on how Latinx immigrants intentionally opt in and out of relationships with safety net institutions, enacting agency to strategically access some resources and pursuing other options outside the safety net. Finally, returning to work was a critical, but fraught workaround. Reliance on work revealed that respondents’ ultimate resource was their health and COVID-19 prevention was a strategy to avoid income loss. While “essential work” has been lionized throughout the pandemic, our study reveals the tensions that individuals face between health and financial security (Bonilla-Silva, 2020). Future research can explore the long-term impact of these workarounds for individuals and families.

Our findings are subject to some limitations. First, we focused on regions within California, a state with relatively pro-immigrant policies, and findings may not be generalizable to other rural Latinx immigrants. However, as we found, immigrants, as well as safety net providers, were still subject to federal immigration exclusions. Therefore, similar dynamics of workarounds may exist in other regions. Second, our respondents had long resided in a region with established immigrant communities. As a result, this sample may have had stronger existing relationships with the safety net. Given the diversity of Latinx immigrants settling in newer communities across the rural U.S., future research is needed in other regions and among more recently arrived populations. Finally, these interviews were conducted in the first 12 months of the pandemic. The long-term impacts of the pandemic will likely appear in years to come; future research should continue to monitor and assess how exclusions and workarounds influence Latinx immigrant health.

The COVID-19 pandemic will end but its effects will be felt for years. Inequities related to rurality and legal status should be understood in relation to their intersections with one another. Ongoing and future safety net policies and programs should be tailored to meet rural community needs and be inclusive regardless of citizenship status. Further, health crisis and disaster preparation must consider the growing immigrant populations in rural communities and address the inequities related to immigration policy and rural context that may put them at risk.

Funder

This study was supported by funding from the University of California Office of the President; Health Sciences Research Institute at UC Merced; and California Initiative For Health Equity and Action at UC Berkeley.

Credit author statement

Maria-Elena De Trinidad Young: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft. Fabiola Perez-Lua: Formal analysis; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft, Hannah Sarnoff: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing, Vivianna Plancarte: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing, Sidra Goldman-Mellor: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Writing – review & editing. Denise Diaz Payán: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the participants who provided their time and perspectives. They also thank the CLIMA Community Advisory Board (ACLU of Northern California, California Immigrant Policy Center, Pesticide Reform, Comite Civico Del Valle Inc., Faith in the Valley, Farmworker Justice, Pan Valley Institute, UC Merced Community and Labor Center, and others) who helped with data collection efforts during the pandemic.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia Dolores, Joshi Pamela K., Ruskin Emily, Walters Abigail N., Sofer Nomi. Restoring an inclusionary safety set for children in immigrant families: a review of three social policies. Health Aff. 2021;40(7):1099–1107. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcus Holly R., Simmons Laura. Ethnic restructuring in rural America: migration and the changing faces of rural communities in the great plains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;65(1):130–152. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.658713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barofsky Jeremy, Vargas Ariadna, Rodriguez Dinardo, Anthony Barrows. Spreading fear: the announcement of the public charge rule reduced enrollment in child safety-net programs. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1752–1761. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Kevin J., Borders Tyrone F., Holmes George M., Kozhimannil Katy Backes, Ziller Erika. What is rural? Challenges and implications of definitions that inadequately encompass rural people and places. Health Aff. 2019;38(12):1985–1992. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein H., Gonzalez D., Karpman M. Adults in Low-Income Immigrant Families Were Deeply Affected by the COVID-19 Crisis yet Avoided Safety Net Programs in 2020. Urban Institute; 2021. p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. Color-blind racism in pandemic times. Sociology Race Ethnicity. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2332649220941024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broder Tanya, Lessard Gabrielle, Moussavian Avideh. National Immigration Law Center; 2021. Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante Arturo Vargas, Chen Jie, McKenna Ryan M., Ortega Alexander N. Health care access and utilization among U.S. Immigrants before and after the affordable care act. J. Immigr. Minority Health. 2019;21(2):211–218. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Heide, Holmes Seth M., Madrigal Daniel S., Young Maria-Elena DeTrinidad, Beyeler Naomi, Quesada James. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 2015;36(1):375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney Ann M., Newkirk Christine, Rodriguez Katheryn, Montez Anselmo. Inequality and health among foreign-born latinos in rural borderland communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;215:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.011. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Kent Jason G., Sun Yue, Monnat Shannon M. COVID-19 death rates are higher in rural counties with larger shares of blacks and hispanics. J. Rural Health. 2020;36:602–608. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E., Fredricks K., Woc-Colburn L., Bottazzi M.E., Weatherhead J. Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020;14(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley Martha, Lichter Daniel T., Turner Richard N. Diverging fortunes? Economic well-being of latinos and african Americans in new rural destinations. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015;51:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros Diego F., Branscum Adam J., Mukandavire Zindoga, Miller F. DeWolfe, MacKinnon Neil. Dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in urban and rural areas in the United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 2021;59:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despres Cliff. 2021. Update: Coronavirus Case Rates and Death Rates for Latinos in the United States.” Salud America! Retrieved ( https://salud-america.org/coronavirus-case-rates-and-death-rates-for-latinos-in-the-united-states/ [Google Scholar]

- Fox Cybelle. Unauthorized welfare: the origins of immigrant status restrictions in American social policy. J. Am. Hist. 2016;102(4):1051–1074. doi: 10.1093/jahist/jav758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Jacqueline. 2020. Financial Help for California's Undocumented Immigrants Starts Monday.” Cal Matters. Retrieved ( https://calmatters.org/california-divide/2020/05/financial-help-available-californias-undocumented-immigrants-monday/ [Google Scholar]

- Gil Raul Macias, Marcelin Jasmine R., Zuniga-Blanco Brenda, Marquez Carina, Mathew Trini, Damani A., Piggott COVID-19 pandemic: disparate health impact on the hispanic/latinx population in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;222(10):1592–1595. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza Tanya, Valdez Zulema. Nested contexts of reception: undocumented students at the university of California, central. Socio. Perspect. 2018;61(4):535–552. doi: 10.1177/0731121417743728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith Carrie, Tuttle Mariana, Kozhimannil Katy B. Unequal distribution of COVID-19 risk among rural residents by race and ethnicity. J. Rural Health. 2020;37(1):224–226. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Leif, Yang Tse-Chuan, Jentsch Birgit, Simard Myriam. International Migration and Rural Areas: Cross-National Comparative Perspectives. Ashgate; England: 2009. Taken by surprise: new immigrants in the rural United States. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlke Renate M. Generic qualitative approaches: pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2014;13(1):37–52. doi: 10.1177/160940691401300119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman Brystana G., Whitaker Rebecca, George Pink, Mark Holmes G. Half of rural residents at high risk of serious illness due to COVID-19, creating stress on rural hospitals. J. Rural Health. 2020;36(4):584–590. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiester Elizabeth, Vasquez-Merino Jennifer. A virus without papers: understanding COVID-19 and the impact on immigrant communities. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2021;9(2):80–93. doi: 10.1177/23315024211019705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad Jens Manuel, Lopez Mark Hugo. Pew Research Center; 2020. Coronavirus Economic Downturn Has Hit Latinos Especially Hard. [Google Scholar]

- Lahr Megan, Henning-Smith Carrie, Rahman Adrita, Hernandez Ashley. University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center; 2021. Barriers to Health Care Access for Rural Medicare Beneficiaries: Recommendations from Rural Health Clinics. Policy Brief. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., Brown David L. Rural America in an urban society: changing spatial and social boundaries. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011;37(1):565–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Philip, Calvin Linda. Immigration reform: what does it mean for agriculture and rural America? Appl. Econ. Perspect. Pol. 2010;32(2):232–253. doi: 10.1093/aepp/ppq006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Maria Elena, Nodora Jesse N., Carvajal-Carmona Luis G. The dual pandemic of COVID-19 and. Systemic Inequities US Lat. Communities. 2021;127(10):1548–1550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar Cecilia. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2013. Constructing Immigrant “Illegality”: Critiques, Experiences, and Responses. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Charlotte E., Vasan Ramachandran S. The southern rural health and mortality penalty: a review of regional health inequities in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021;268 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora Ana M., Lewnard Joseph A., Kogut Katherine, Rauch Stephen A., Hernandez Samantha, Wong Marcus P., Huen Karen, Chang Cynthia, Jewell Nicholas P., Holland Nina, Harris Eva, Cuevas Maximiliano, Eskenazi Brenda, CHAMACOS-Project-19 Study Team Risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among farmworkers in monterey county, California. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller Tom, McConnell Kathryn, Berne Paul Burow, Pofahl Katie, Merdjanoff Alexis A., Farrell Justin. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118(1) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019378118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy B.P., Sterrett N., Weller D. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage between urban and rural counties — United States, december 14, 2020–april 10, 2021. MMWR (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.) 2021;70(20):759–764. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e3. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e3external icon. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obinna Denise N. Confronting disparities: race, ethnicity, and immigrant status as intersectional determinants in the COVID-19 era. Health Educ. Behav. 2021;48(4):397–403. doi: 10.1177/10901981211011581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco Flores Edward, Ana Padilla . Community and Labor Center at the University of California; Merced: 2020. Persisting Joblessness Among Non‐Citizens during COVID‐19. Policy Report. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A., Rumbaut R.G. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2001. Legacies : the Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Sarah M., Don Villarejo. Poverty, housing, and the rural slum: policies and the production of inequities, past and present. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2012;109(2):1664–1675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Danielle T. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2020. Health Care off the Books Poverty, Illness, and Strategies for Survival in Urban America. [Google Scholar]

- Romani Maria. ACLU of Northern California; Fresno: 2022. Collusion in California's Central Valley: the Case for Ending Sheriff Entanglement with ICE. [Google Scholar]

- Romano Sebastian D., Blackstock Anna J., Taylor Ethel V., Felix Suad El Burai, Adjei Stacey, Christa-Marie Singleton, Fuld Jennifer, Bruce Beau B., Boehmer Tegan K. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations, by region — United States, march–december 2020. MMWR (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.) 2021;70(15):560–565. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7015e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadi Altaf, Molina Uriel Sanchez, Franco-Vazquez Andree, Inkelas Moira, Gery W., Ryan Assessment of perspectives on health care system efforts to mitigate perceived risks among immigrants in the United States: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. ANS. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1993;16(2):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souch Jacob M., Crossman Jeralynn S. A commentary on rural-urban disparities in COVID-19 testing rates per 100,000 and risk factors. J. Rural Health. 2020;37(1):188–190. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touw Sharon, McCormack Grace, Himmelstein David U., Woolhandler Steffie, Zallman Leah. Immigrant essential workers likely avoided Medicaid and SNAP because of A change to the public charge rule. Health Aff. 2021;40(7) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USCIS . 2021. Public Charge Fact Sheet. Retrieved ( https://www.uscis.gov/archive/public-charge-fact-sheet. [Google Scholar]

- van Dorn Aaron, Cooney Rebecca E., Sabin Miriam L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Natta Meredith, Burke Nancy J., Yen Irene H., Fleming Mark D., Hanssmann Christoph L., Rasidjan Maryani Palupy, Shim Janet K. Stratified citizenship, stratified health: examining Latinx legal status in the U.S. Healthcare safety net. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;220:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace Steven P., Young Maria-Elena De Trinidad, Rodriguez Michael A., Brindis Claire D. vol. 7. 2019. (A Social Determinants Framework Identifying State-Level Immigrant Policies and Their Influence on Health). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willen Sarah S. How is health-related ‘deservingness’ reckoned? Perspectives from unauthorized im/migrants in tel aviv. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(6):812–821. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Philip Q., Hwang Shann Hwa. Explaining immigrant health service utilization: a theoretical framework. Sage Open. 2016;6(2):1–15. doi: 10.1177/2158244016648137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young Maria-Elena De Trinidad, Beltrán-Sánchez Hiram, Wallace Steven P. States with fewer criminalizing immigrant policies have smaller health care inequities between citizens and noncitizens. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20(1):1460. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]