Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many nursing schools limited in-person clinical instruction to lower the risk of student exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Some U.S. state boards of nursing authorized virtual learning experiences to attempt to fill this void. The effects of restricting such hands-on training are not fully understood, but we believed it could be detrimental to student development and saw partnering with local COVID-19 vaccination clinic as a promising alternative. Between January and April 2021, second semester pre-licensure nursing students assisted at the clinic and submitted reflections on the experience. The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of this educational encounter.

Methods

One hundred seventy-one students submitted reflections on their experience, which were de-identified and uploaded to a HIPAA- and FERPA-compliant cloud storage system using SAFE desktop and coded for thematic analysis.

Results

Analysis revealed five major themes: community, socializing, perceived confidence, impact, and professional role.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the viability of instruction at a COVID-19 vaccination clinic as an alternative learning experience for nursing students encountering restricted face-to-face clinical training. It suggests that schools can develop other novel clinical experiences to increase students' perceived confidence, provide opportunities to practice skills, and gain insights into nursing practice.

Keywords: Nursing students, Clinical reflections, Novel clinical experience, COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19 pandemic

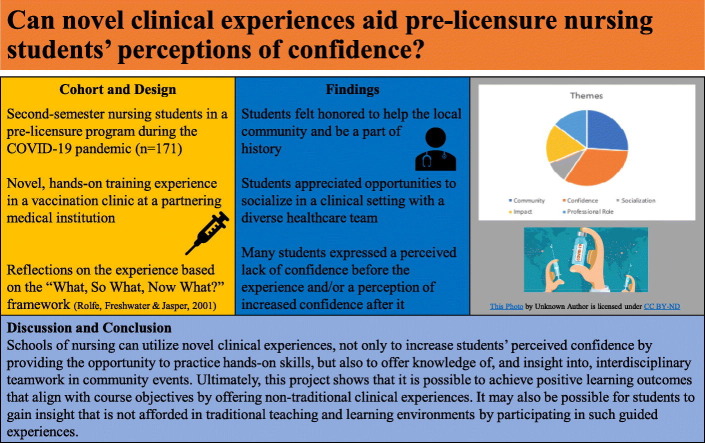

Graphical abstract

Introduction

During the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic, nursing education delivery was forced to change. Many nursing schools around the world had to reduce the number of face-to-face classes and hospital clinical rotations due to government restrictions to reduce the risk of student exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Additionally, many healthcare partner institutions stopped allowing student nurses access to their facilities for training, to attempt to reduce the risk of students inadvertently exposing their staff or patients to COVID-19.

These constraints created numerous challenges for nursing education in the United States. Due to social distancing and other restrictions, nursing students were forced to learn remotely and had limited opportunities to practice hands-on clinical skills. Some state boards of nursing authorized use of virtual learning experiences to try to fill the void of in-person learning; while some schools of nursing took advantage of this change (NCSBN, 2020, NCSBN, 2020), the effects of such training are not yet known.

Recognizing the potential implications of the pandemic for the readiness of future nurses to practice safely and effectively, the Maryland Nurses Association (MNA) called on nursing faculty to become innovative and flexible in experiences that would meet course objectives and program outcomes (Watties-Daniels, 2020). This call led our school of nursing to explore alternative educational opportunities that would permit hands-on learning in a safe, innovative fashion.

Literature review

Reflections and experiences of student nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic were limited at the time of this study's inception but suggested complex interactions between students' own lived experiences of the pandemic and their attempts to train to become nurses when faced with numerous constraints on their coursework. Savitsky et al. (2020) stated that over half of Israeli nursing students in their study screened positive for moderate to severe anxiety during the lockdown. In Sweden, Langegård et al. (2021) found that many students preferred in-person learning, with some reporting decreased motivation with the online format. Hamadi et al. (2021) reported that nursing students at a private university reported higher stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it; interestingly, the highest increase in stress was in the category “lack of professional knowledge and skills” (p. 631). Students at five schools of nursing across the U.S., meanwhile, felt that it was difficult to connect with their student peers and instructors due to the virtual learning format, with some reporting that the loss of student peer socialization was the hardest part of the pandemic. Notably, though, the authors found that these students nonetheless felt the pandemic strengthened their desire to become nurses (Michel et al., 2021).

Clinical experience in nursing education provides opportunities for students to learn critical thinking and judgement, build confidence, improve nursing skills, act as a member of the clinical team, and model the professional nurse role. When such training is lacking, recent evidence suggests that students may suffer both personally and professionally, yet when it is present—particularly during periods of great morbidity and mortality—students may find it especially gratifying. Dickel (2021), for example, expressed frustration, anger, and hopelessness that she and her fellow students were given “subpar” virtual experiences in place of contributing to the health of patients, despite the risks of infection, and wished that she and her peers could be utilized like student nurses were in Great Britain and Australia (p. 334). Indeed, Casafont et al. (2021) reported that Spanish nursing students were permitted to work in hospitals, including with COVID-19 patients; students in their study expressed feelings of helpfulness and pride from contributing to the pandemic response. Townsend (2020), meanwhile, reported that an optional, extended experience in a hospital in Great Britain during the pandemic helped him grow emotionally and mature professionally and that he felt useful, proud, and privileged to participate in nursing care during such challenging times, though he confessed that the experience created anxiety for his family, who worried about his well-being. This student reflected on feeling useful, proud and privileged to participate in providing nursing care during unprecedented times (Townsend, 2020). Limiting in-person experiences for students has the potential to slow the growth of clinical reasoning, reduce or delay skill development, and decrease confidence in pre-licensure nursing students (Noh, 2021).

These articles also suggest the benefit of searching for new educational opportunities that balance student nurses' involvement in the pandemic response with minimizing risks to students and others, to attempt to mitigate these possible barriers to their professional development. One attempt at such a solution involved the use of nursing students to assist with COVID-19 vaccination efforts. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), which oversees the examination and licensing of nurses in the U.S., encouraged partnerships between schools of nursing and medical and health institutions to assist with their COVID-19 vaccination efforts. It is unclear how many institutions heeded this suggestion, though St. Luke's University Health Network (2021) enlisted nursing students to help provide vaccinations and found that their students stressed the desires to be productive members of the healthcare team, give back to their local community, and therefore actively participate in the global effort against COVID-19. Towson University provided a similar experience for their nursing students to provide an opportunity to interact and engage with people and provide the chance to apply their injection skills (Boteler, 2021).

The project

For this project, second-semester master's entry-to-practice nursing students spent time assisting at a COVID-19 vaccination clinic as part of a foundational adult medical-surgical clinical course from January through April 2021. The purpose of this experience was to not only provide additional clinical experience and increase confidence in the skill of giving an intramuscular injection, but to give students an opportunity to promote patient education, assist in vaccination efforts, model inter-professional teamwork and to encourage self-reflection. Following the vaccine clinic, students were asked to reflect on this activity using the “What? So, what? Now what?” framework originally described by Rolfe, Freshwater & Jasper in 2001.

The occupational health vaccination clinic served students and staff at a large, metropolitan health system in the United States. The clinic stocked the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine that was granted Emergency Use Authorization in August 2020, for use in the prevention of COVID-19 in individuals 16 and older (Federal Drug Administration, 2022). The safety protocols for the vaccination clinic required face coverings and social distancing for all people at the clinic. The students and vaccinators also donned face shields. Employees and students with appointments were pre-screened for COVID-19 symptoms and were re-screened upon arrival at the clinic. If they had symptoms, they were instructed to either stay home or leave the clinic immediately and follow up with testing for COVID-19.

Small groups of students rotated through the vaccination clinic for one assigned clinical day during the semester. Prior to the clinic, students completed an educational module about SARS-CoV-2 and the newly approved vaccines, which was created by one of the course instructors. The prework activity culminated in a post-module quiz to assess content knowledge. Designated student activities at the vaccination clinic consisted of rotating through four stations to help with check-in, administer vaccines, and perform post-vaccine observation for employees and students.

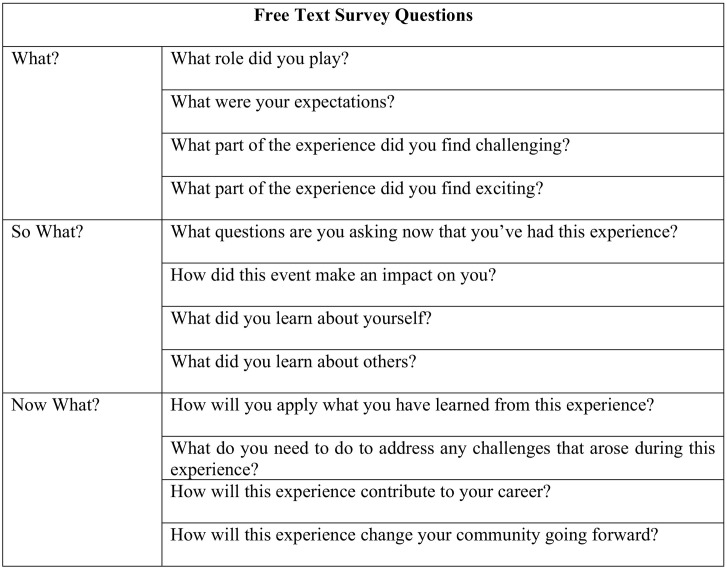

On the day of the clinic, students reviewed proper intra-muscular administration technique using an injection pad made of rolled gauze and saline in a needleless syringe. During the four-hour rotation, student responsibilities included (1) assisting with patient check-in and document verification before escorting patients to injection stations, (2) observing vaccine dosing with pharmacy and delivery of the prepared syringes to vaccinators, (3) confirming eligibility and administering vaccines under the supervision of experienced nurses, and (4) assisting Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) monitor for post-vaccination side effects. Following the experience, the students submitted a reflection on the activity by answering twelve free-text survey questions (Fig. 1 ). Reflections were submitted to a learning management system and graded by the course coordinators. The activity was created by a course coordinator and used the “What? So, what? Now what?” framework originally described by (Rolfe et al., 2001).

Fig. 1.

Free text survey questions that students answered following the clinic experience.

The unique clinical activity utilized a combination of virtual and tactile instruction to limit potential for disease exposure for students and staff. This method allowed students to learn vaccine theory content through an asynchronous, virtual format and then apply this knowledge through hands-on clinical practice. The goal of this project was to review students' reflections on their experiences participating in the vaccination effort during the pandemic. The aims were to analyze the student reflections and identify common themes.

Methods and materials

The project authors used the reflection responses to perform a retrospective analysis. These data were downloaded from a learning management platform and did not capture protected health information (PHI). No demographic data were collected, to minimize participant risk. For this reason, informed consent was not required, because no ethical concerns existed. Data collection and access were limited to the research team members. The project was awarded an IRB exemption waiver by the home institution.

One hundred seventy-one students provided reflections, which were the principal data sources. Data were de-identified by one researcher, who then exported them to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The spreadsheets were then uploaded to a HIPAA- and FERPA-compliant cloud storage system using SAFE desktop; only members of the project team had access to the data. The reflections were divided evenly among the research team, then coded using Microsoft Word. The members of the team rotated through each batch of reflections as an independent double-check. While reading responses, each reviewer made note of comments that were similar among multiple respondents. If two or more respondents had a similar response to the question, the team member noted this on a Word document and kept count of all similar responses. Once the preliminary review was conducted, all project team members deliberated to identify common themes and sub-themes. Results were coded for thematic analysis, and a quantitative approach was used to analyze the number of responses for each theme.

Results

Analysis of the data revealed 5 major themes, as well as various sub-themes (Table 1 ). The major themes that were identified are community, socializing, perceived confidence, impact, and professional role. The theme of community was discussed 157 times in the reflections, with sub-themes of local and state communities and hospital/school of nursing community. Socialization was mentioned in 56 reflections; sub-themes included employee-patient socialization as well as professional/teamwork socialization. The perception of confidence was the most common theme, with 201 comments, and it included sub-themes of perceived lack of confidence and/or gain in confidence. Impact was the third-largest theme, with 103 responses, and it included sub-themes of being a part of history and impacting the end of the pandemic. Lastly, the professional role theme was present in 87 comments and contained sub-threads of pride in nursing/choosing the right profession and professional skills as a nurse.

Table 1.

Major themes and sub-themes of students' reflections.

| Major theme with sub-themes | Total number of responses N = 171 (%) |

|---|---|

| Community | 157 |

| Local/state | 43 (25.1) |

| Hospital/school of nursing | 51 (29.8) |

| Outreach | 63 (36.8) |

| Socialization | 49 |

| Employee-patient | 14 (8.2) |

| Professional/teamwork | 35 (20.5) |

| Perceived confidence | 201 |

| Lack of | 58 (33.9) |

| Gain in | 143 (83.6) |

| Impact | 103 |

| Part of history | 68 (39.8) |

| Back to normal, end of pandemic | 35 (20.5) |

| Professional role | 87 |

| Made correct choice of profession, pride | 28 (16.4) |

| Skills | 59 (34.5) |

Discussion

Theme of community

The theme of community was represented in many responses and included sub-themes of connection to and impact on the local community, such as city and state. Many of the respondents came to the school from out of state and had limited in-person interactions with fellow students or others in the area before this experience, so it is unsurprising that the experience helped them feel more a part of the local community, while giving them the opportunity to serve. The students respondents also mentioned how this experience allowed them to feel like a member of the hospital/school of nursing community of students and healthcare workers, which had been lacking due to restricted personal and professional interactions. Community outreach was another common sub-theme throughout the reflections, including the desire to volunteer with further public health efforts throughout the region. This echoes what was present in the literature; students crave safe, innovative clinical learning experiences, even amid a global pandemic, that help provide a sense of belonging (Townsend, 2020; Casafont et al., 2021; Dickel, 2021).

Theme of socializing

Having the opportunity for socializing during the pandemic seemed to have a substantially positive impact on the participants; it was mentioned in over fifty responses. Students reflected favorably on having the ability to interact and socialize with employee-patients, peers, and other staff members at the clinic. They expressed that this opportunity to interact with others in this clinical setting helped them feel connected to the healthcare team, which was lacking prior to the experience. During the uncertainty that overwhelmed the early stages of the pandemic, respondents reported appreciating any opportunity to meet with their peers for social learning interactions.

Theme of perceived confidence

The perception of confidence was the most frequently mentioned theme in the student reflections. 33 % (n = 58) of respondents expressed a perceived lack of confidence prior to the experience regarding IM injection skills, medication administration procedures, patient interactions, multi-disciplinary interactions, and even their understanding of the nursing professional role. After completion of this experience, 83.6 % (n = 143) of respondents expressed a perceived gain in confidence. One respondent reflected that nursing school is full of first times, but this experience helped show them that they are prepared for the ever-changing profession of nursing. According to their reflections, participant perception of confidence improved not only in their understanding of the nursing professional role, but also in their decision to pursue a career in nursing.

Theme of impact

Discussion of the impact of this experience was present in many of the student reflections. The personal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was a major component in their reflections in which they discussed how the pandemic impacted them, their families, and communities in many ways. Students expressed that they, as well as their families and home communities, were negatively impacted—both emotionally and economically—by the pandemic. On the other hand, many respondents mentioned the historical impact they will have by participating in public health measures during a once-a-century pandemic (n = 68). One student reflected on how the experience will contribute to their career, and that being a part of the vaccine clinic team was life changing. Another impactful outcome mentioned by the respondent was that they appreciated being able to help the community get back to normal (n = 35). The respondents' comments expressed that they felt honored to have an impact on the health outcomes of the hospital community and in turn, the local community.

Theme of professional role

Lastly, there emerged the theme of the professional role. Of the students surveyed, over half (n = 87) expressed pride in their future profession as a nurse. Many students stated the importance of gaining competence in clinical skills to prepare for the nursing role and were worried they would not get enough practice, due to the pandemic. The experience allowed students to reflect on the nursing role in multidisciplinary community health initiatives. One shared that the experience will help the clinical group be a more cohesive and responsible members of the care team. One student commented that the experience impacted how they intend to approach the profession by striving to foster teamwork and inclusivity in their future work environment, modeled after the vaccine clinic experience. In general, this theme showed that the students felt the novel clinical experience positively contributed to their understanding of the professional role of nurses.

The results of this project show that this structured, alternate clinical learning experience helped to increase students' perception of confidence in performing fundamental nursing skills while providing a better understanding of and appreciation for interdisciplinary roles and teamwork. Students had the perception of strengthened interpersonal communication skills with the healthcare team, their peers, and employee-patients. Importantly, this clinic-based educational experience demonstrated the feasibility of a safe, effective alternative to virtual learning formats for skills development during a pandemic. Based on respondent reflections, it seems that enhanced experiences like these are what students want and expect from their nursing programs. In this setting, students were able to strengthen their skills, be important members of a major public health initiative, and feel a sense of pride in the profession of nursing.

Strengths and limitations

There were several strengths and limitations to this project. First, it was a retroactive analysis, so data were readily available from a previously submitted reflection assignment. Second was the ability to partner with a medical institution that is affiliated with the school of nursing, which meant clinical site compliance requirements were already completed. Third, the educational format has an easily reproducible design, which could motivate other schools of nursing to continue studying how student learning is affected by novel clinical experiences.

There were also three limitations to this study. The first is incomplete or incorrectly formatted reflection submissions (for example, one student in the cohort did not submit the reflection assignment and some others did not use the relevant framework). A second limitation was the short duration of time that each group spent in the vaccine clinic; this was due largely to scheduling constraints with the clinic and also to the perceived fear of a few students of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, limiting some students' participation in this activity. Third is the uniqueness of the COVID-19 pandemic; it is impossible to know if vaccines with new Emergency Use Authorization will be used in mass vaccination efforts for future pandemics, as they were during COVID-19. The use of commonly used vaccines may result in changes to themes derived from student reflections.

Overall, the student respondents expressed their desire to be an active participant in the COVID-19 pandemic response and community outreach efforts, which echoed the literature findings (Casafont et al., 2021; Dickel, 2021; Townsend, 2020). One comment noted feeling more of a part of the nursing profession and mentioned having pride in their ability to help. One participant noted they felt pride in helping on the “front lines”. Another student focused on the community impact they might have, hoping community members will recognize that the students want to be of service. These reflections suggest an area for future student nurses' involvement in projects or initiatives in the surrounding community.

Schools of nursing can utilize other novel clinical experiences, not only to increase students' perceived confidence by providing the opportunity to practice skills, but also to offer insight and knowledge of interdisciplinary teamwork in community events. One participant noted the level of teamwork that was needed to deliver exceptional patient care. Without this experience, this cohort of nursing students may not have had the opportunity to witness the impact nurses can have on individual and community health outcomes.

These findings have many implications for nursing education and practice. Ultimately, the project shows that it is possible to achieve positive learning outcomes that align with course objectives by offering non-traditional clinical experiences. It may also be possible for students to gain insight that is not afforded in traditional teaching and learning environments by participating in such guided experiences. Providing a structured activity with a medical/institutional partner allows nursing students to collaborate with other professionals to better understand their professional role. Nurse educators have an opportunity to be creative with other non-traditional opportunities that may help students achieve competence, improve perceived confidence, and further professional development while providing the opportunity to improve public health outcomes.

Conclusion

Nursing students require participation in hands-on experiences to achieve competence in clinical skills and knowledge of professional practice. The theme of confidence showed these students felt their perception of confidence improved with patient/staff interaction, and implementation of learned skills. In addition to the contribution to student development, medical institutions benefit from having nursing students assist with public health efforts. Schools of nursing play an important role in their communities, and nursing students are a valuable presence within health care systems—this is even more evident during times of crisis. The students in this study reported how important it was for them to have an impact and feel a part of an important moment in history as members of the healthcare community. It is the responsibility of schools of nursing to provide safe, effective opportunities for student learning even when the traditional methods of in-person learning are not possible.

While there have always been many challenges to providing adequate competency-based learning for nursing students, the COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented barriers. The ability of an entry-level nursing program to maintain teaching and learning standards during times of crisis is more essential now than it may have ever been before. Future students could be entering the nursing profession in times of turmoil and doubt, with circumstances that are ever-changing and seemingly unconquerable.

This study showed that providing nursing students with learning experiences that not only help strengthen skills but also facilitate their connection to the profession (and community) is vital to providing quality care with equitable access to all. The themes of community, socialization and professional role seen in this study show that nursing students continue to be stakeholders in the health and wellness of their community. They are resilient enough to prioritize their learning during the uncertainty of a global pandemic and will certainly be resilient enough to take on the next inevitable global (or local) challenges that come their way. By offering experiences outside of the typical clinical learning environment, schools of nursing can help to contribute to the resilience and endurance of future new nurses.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for extremely helpful feedback on previous versions of this paper.

Funding sources

There were no funding sources or individuals who contributed to the conduct of the manuscript. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Boteler C. Nursing students partnering in COVID-19 vaccine clinics. 2021. https://www.towson.edu/news/2021/vaccine-clinics-covid.html

- Casafont C., Fabrellas N., Rivera P., Olivé-Ferrer M.C., Querol E., Venturas M., Prats J., Cuzco C., Frías C.E., Pérez-Ortega S., Zabalegui A. Experiences of nursing students as healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A phenomenological research study. Nurse Education Today. 2021;97(1) doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickel C.L. COVID-19: Nursing students should have the option to help. American Journal of Public Health. 2021;111(3):334. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Drug Administration Comirnaty and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/comirnaty-and-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine

- Noh G.-O. In COVID-19, unmet needs of nursing students participating in limited clinical practice. Medico-Legal Update. 2021;21(4):150–155. doi: 10.37506/mlu.v21i4.3120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadi H.Y., Zakari N.M.A., Jibreel E., AL Nami F.N., Smida J.A.S., Ben Haddad H.H. Stress and coping strategies among nursing students in clinical practice during COVID-19. Nursing Reports. 2021;11(3):629–639. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11030060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langegård U., Kiani K., Nielsen S.J., Svensson P.-A. Nursing students’ experiences of a pedagogical transition from campus learning to distance learning using digital tools. BMC Nursing. 2021;20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00542-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel A., Ryan N., Mattheus D., Knopf A., Abuelezam N.N., Stamp K., Branson S., Hekel B., Fontenot H.B. Undergraduate nursing students' perceptions on nursing education during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: A national sample. Nursing Outlook. 2021;69(5):903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCSBN Changes in education requirements for nursing programs during COVID-19. 2020. https://www.ncsbn.org/Education-Requirement-Changes_COVID-19.pdf

- NCSBN Policy brief: COVID-19 Vaccine administration. 2020. https://www.ncsbn.org/COVID19VaccineAdministrationPolicyBrief.pdf

- Rolfe G., Freshwater D., Jasper M. Palgrave MacMillan; 2001. Critical reflection for nursing and the helping professions: A user's guide. [Google Scholar]

- Savitsky B., Findling Y., Ereli A., Hendel T. Anxiety and coping strategies among nursing students during the covid-19 pandemic. Nurse Education in Practice. 2020;46(1) doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Luke’s University Health Network Nursing students make history giving COVID vaccines. 2021. https://www.slhn.org/blog/2021/nursing-students-make-history-giving-covid-vaccines

- Townsend M.J. Learning to nurse during the pandemic: A student's reflections. British Journal of Nursing. 2020;29(16):972–973. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.16.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watties-Daniels D. The impact of COVID 19 on nursing student clinical practice: A time for clinical innovation. Maryland Nurse. 2020;21(5):5. https://assets.nursingald.com/uploads/publication/pdf/2146/Maryland_Nurse_11_20.pdf [Google Scholar]