Abstract

As the current COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting crew change crisis exacerbates the mental health problem faced by seafarers, various maritime stakeholders have mobilised their resources and strengths to provide a variety of supportive measures to address the issue. This paper aims to find out what measures have been adopted in the industry and how widely they have been experienced/received by seafarers and evaluate their effectiveness. To achieve this aim, this research employed a mixed methods design involving qualitative interviews with 26 stakeholders and a quantitative questionnaire survey of 817 seafarers. The research identified a total number of 22 mental health support measures, all of which were perceived to have contributed positively to seafarers’ mental health. However, not all of them were widely available to or utilised by seafarers. The findings also highlighted the importance of family, colleagues, shipping companies, and government agencies, as they are associated with the most effective support measures, namely communication with family, timely crew changes, being prioritised for vaccination, being vaccinated, and a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board. Based on the findings, recommendations are provided.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Crew change crisis, Depression and anxiety, Mental health, Seafarer well-being, Seafarers’ welfare

1. Introduction

Seafarers working at sea encounter various occupational stressors, such as long-term separation from home, social isolation, work intensification, harsh working and living conditions, unstable employment opportunities, pressure from frequent inspections, bullying and harassment, and a lack of adequate rest, which can result in mental health problems [6], [20], [23]. The latter not only are detrimental to seafarers’ well-being but also increase injury and illness rates at sea and lead to attrition [16], [24]. As a result, the industry and the research community have started to pay attention to the mental health of seafarers since the late 2000s. At the same time, seafarers’ welfare organisations have taken initiatives to improve seafarers’ mental health, such as the SeafarerHelp line operated by the International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN), and the Wellness at Sea mobile application (app) developed by the Sailors’ Society.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated seafarers’ mental health problems by forcing many countries to impose travel restrictions and resulting in a crew change crisis. At its peak, the crisis resulted in 400,000 seafarers being trapped on their vessels beyond their employment contracts [11]. Uncertainties associated with crew changes, the lack of shore leaves, and the risk of being infected with the virus added to existing occupational stressors and caused serious mental health issues among seafarers and even drove some to suicide [7], [8], [9], [10]. To date, there are still seafarers unable to join or sign off a ship on time due to the pandemic.

In response, stakeholders have adopted various measures to address the crisis and other pandemic-induced problems, and to support seafarers’ psychological wellbeing. However, it is unclear so far what measures have been adopted in the industry, and perhaps more importantly, what seafarers’ experiences and opinions of these measures are. This paper examines these two questions, and through this examination, it provides the industry and stakeholders with insights into the availability of mental health support to seafarers during the pandemic and their perceived effectiveness. These insights in turn will help the stakeholders formulate and implement more targeted and effective mental health policy interventions.

2. Literature review

A large body of literature has explored various risk factors affecting seafarers’ mental health, demonstrating that the working environment at sea exposes seafarers to stress and psychological harm [3], [2], [13], [14], [20]. Nevertheless, due to the stigma associated with mental health problems, it is suggested that seafarers are reluctant to acknowledge them and seek support. The UK Chamber of Shipping [25] pointed out:

It’s difficult to know how many people have been affected by mental health issues while working at sea – it's still an issue ‘hidden’ behind stigma. This might be explained by a certain culture of ‘machismo’ among seafarers, where any form of illness is perceived as weakness.

In this context, questionnaire studies of active seafarers may have captured some of the unreported mental health problems. Sampson et al. [21] conducted two surveys of seafarers’ health, one in 2011 with a sample of 1026 active seafarers and the more recent in 2016 with 1523 seafarers. In the 2011 survey, 28 % of the respondents indicated the presence of a ‘psychiatric disorder’, while in 2016, 37 % of the respondents did so. Andrei et al. [4] surveyed 1026 seafarers from a sample of ships regularly visiting Australian ports. In this survey, about 40 % of the respondents reported experiencing mental health problems (depression and anxiety) at least sometimes, and around 10 % of them reported experiencing these problems often. Furthermore, this survey found that seafarers were more likely to experience mental health problems when they were suffering from chronic fatigue and sleep problems and working in demanding roles; and conversely, they were less likely to experience mental health problems in the presence of a stable crew (i.e. regularly working with the same crew members). These studies indicated that mental health problems among seafarers are prominent. This concern is further confirmed by Lefkowitz and Slade’s [16] survey of 1572 seafarers, in which a quarter of the respondents reported suffering from depression, 17 % from anxiety, and 20 % had suicidal ideation. Lefkowitz and Slade’s [16] analysis further highlighted three issues. First, compared with other working populations, seafarers had higher rates of depression. Second, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation were likely to increase the likelihood of injury and illness at sea. Third, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation may increase the attrition rate of seafarers.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent crew change crisis have raised further concerns about seafarers’ mental health. Industry reports suggested that due to the crew change crisis and their never-ending contracts, seafarers suffered from anxiety, panic attacks, depression, loneliness, frustration, fatigue, and burnout [8], [9], which significantly increased the instances of seafarers calling mental health support hotlines about suicidal thoughts and other concerns [7], [8]. This trend has been confirmed by the research literature. Qualitative studies [15], [22] showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic seafarers at sea endured fatigue and crew change related uncertainties, which caused stress, anxiety, depression, and even suicidal thoughts. In the survey conducted by Baygi et al. [5] during the pandemic with 439 seafarers, 42.6 % of the respondents reported general psychiatric disorders, higher than that in Sampson et al.’s [21] study before the pandemic mentioned above. Pauksztat et al. [19] compared two samples of seafarers surveyed before and during the pandemic, and they found that the pandemic and the resulting crew change crisis contributed to significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety.

Before the pandemic, a number of measures to safeguard seafarers’ mental health were proposed [6]. Based on their survey findings, Lefkowitz and Slade [16] made a few recommendations, such as putting in place clear and effective anti-bullying and anti-harassment procedures, encouraging seafarers to exercise frequently, and improving seafarers’ sleeping quality and duration. In another questionnaire study of 1507 seafarers, Sampson and Ellis [20] proposed a number of specific measures that could be taken by shipping companies. Such measures included providing free and unlimited internet access on all cargo ships; making both group (swimming, basketball, BBQ, etc.) and solitary (gym, reading, listening to music) recreational activities available onboard; providing comfortable mattresses and furnishing within cabins to facilitate quality rest and sleep; facilitating shore-leave; providing good quality food; making available self-help guidance on improving mental resilience; limiting contract lengths; putting in place anti-bullying and anti-harassment policies; providing training to officers in creating a positive atmosphere on board; and making available counselling services.

During the pandemic, Pauksztat, Grech, and Kitada [19] noted that while the pandemic increased seafarers’ fatigue and mental health problems, the negative impact could be mitigated by support from fellow crew members on board, availability of external support, and availability of fast and reliable Internet access. They also found that seafarers received support from a variety of stakeholders, including shipping companies, family members, government authorities, welfare organisations, and unions.

The above discussion suggests that to safeguard and improve seafarers’ mental health, especially during the pandemic, the stakeholders have been mobilised to leverage their resources and strengths to provide a variety of measures, and that seafarers did seek support from various stakeholders. This is not surprising since shipping companies and seafarers by themselves do not have the full capacity to address the issues related to the pandemic induced crew change crisis. They need support from governments as well as inter-governmental agencies. As such, the International Labour Organization (ILO), International Maritime Organization (IMO), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have recently jointly called for continued collaboration among all relevant stakeholders to address the crew change crisis, safeguard seafarer health and safety, and avoid supply chain disruptions during the pandemic [12].

Given that a range of measures have been taken by various stakeholders to address seafarers’ well-being and mental health issues during this testing time, it is also important to develop a good understanding of these measures by finding out what measures have been adopted and how widely they have been experienced/received by seafarers and evaluating their effectiveness.

3. Research methods

This research employed a mixed methods design, consisting of two stages. In the first stage (from March to June 2021), the qualitative interview method was employed. In line with a stakeholder approach, interviews with various key stakeholders were conducted by four researchers based in different physical locations (i.e., two in the Philippines, one in the UK, and one in Sweden). Three of the researchers, including two ex-seafarers, were experienced in conducting maritime-related research. They relied on their existing research network to recruit a convenience sample of 26 participants for interviews, including 14 seafarers of various ranks, five ship/crewing managers, two maritime school trainers, two port chaplains, two seafarers’ wives, and one maritime authority official. They were from eight different countries, the Philippines (10), China (9), Japan (2), Brazil (1), Jamaica (1), Nigeria (1), India (1), UK (1). Due to the pandemic, the majority (20) of the interviews were conducted remotely, and only six of them were done face-to-face. Ethical approval was granted by the World Maritime University Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was sought from the participants, and anonymity of participants and confidentiality of data was guaranteed.

These interviews aimed to identify what mental health supportive measures to seafarers were provided or received. Informed by the literature [16], [19], [20], the research team asked seafarer interviewees if they knew or experienced any mental health support from various stakeholders (such as companies, welfare organisations, crew members, family, medical professionals, and trade unions) and how they perceived these services or support. Regarding other interviewees, the team asked what mental health they provided and if they knew any other support provided in the industry. In line with the interpretivist perspective, the data were analysed thematically to identify a list of supportive measures provided to or used by seafarers (see Table 2 for the themes).

Table 2.

Categories and themes identified from the interviews and the literature.

| Categories | Themes |

|---|---|

| Monetary support provided directly by companies | overtime/extended service bonus pay |

| increase in food allowances | |

| increase in recreational allowances | |

| COVID-19 specific support provided directly by companies | updates on crew change and COVID-19 information |

| facilitating timely crew changes | |

| provision of sufficient and high-quality personal protective equipment (PPE) for infection control | |

| Welfare & OHS (Occupational Health and Safety) support provided directly by companies | increase in Wi-Fi data allowances |

| provision of immediate family support | |

| outsourced professional counselling services | |

| *reduction of overtime hours | |

| *provision of mental health self-support videos, books, or other materials on board | |

| Mutual support provided by family and crew members (may need to be facilitated by company policy and support) | communication with family |

| group recreational activities | |

| a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board | |

| casual counselling or support among crewmembers | |

| Government vaccination policy support | being prioritized for vaccination |

| being vaccinated | |

| Support provided by welfare organisations | pastoral and spiritual care from port chaplains |

| *seafarers’ mental health helplines | |

| *seafarers’ mental health applications or ‘apps’ | |

| *Self-support | *physical exercise |

| *meditation |

Note: The categories and themes with an asterisk (*) mark are derived from the literature, and the remaining are from the interview data.

In the second stage of the research, an online survey of seafarers who served on ships during the pandemic was carried out. The design of the survey questionnaire was informed by the literature and the findings from the interviews. Apart from the demographic questions, the questionnaire contained a list of 22 mental health support measures and participants were asked if they experienced or were aware of these measures and whether they perceived these measures to be helpful. The survey was available in four languages (English, Chinese, Tagalog, and Japanese) and was hosted online using a paid licensed version of QuestionPro, web-based software for online surveys. The online survey was designed to be simple to navigate and took approximately 10–15 min to complete. Data collection lasted for two and half months from early July to mid-September 2021.

The online survey used convenience sampling. It was promoted in various countries by maritime schools, training centres, seafarers' unions, and other organisations. Social media platforms (such as Facebook, Messenger, and Twitter) were also utilised to disseminate information and recruit participants. Participants were requested to provide informed consent before participation. All responses were completely anonymous to ensure confidentiality and reliability of data. A total number 817 seafarers of various nationalities completed and returned the questionnaire. The data from the completed questionnaires were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0. The demographic information of the 817 participants is provided in Table 1. While in terms of nationality, Filipino seafarers were over-represented, in terms of vessel types, the sample was loosely in line with the UNCTAD [26] statistics on the world merchant fleet which consists of dry bulk 42.8 %, tanker 29.0 %, container 13.2 %, general cargo 3.6 %, and others 11.4 %. Next, the research findings from each stage will be presented in turn.

Table 1.

demographic information of the survey participants.

| Descriptions | Cases/Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | In years | Average age: 31 |

| In years | Age range: 18–69 | |

| Nationality | Filipino | 695 (85.1 %) |

| Chinese | 70 (8.6 %) | |

| Undeclared Nationality | 34 (4.1 %) | |

| Bangladeshi | 7 (0.9 %) | |

| Indian | 5 (0.6 %) | |

| Jamaican | 3 (0.4 %) | |

| British | 1 (0.1 %) | |

| Indonesian | 1 (0.1 %) | |

| Australian | 1 (0.1 %) | |

| Gender | Male | 790 (96.7 %) |

| Female | 15 (1.8 %) | |

| Prefer not to say | 12 (1.5 %) | |

| Rank | Officers | 547 (67 %) |

| Other | 145 (17.7 %) | |

| Ratings | 125 (15.3 %) | |

| Types of vessels | Dry bulk | 259 (32.7 %) |

| Tankers (oil product tankers, chemical tankers, LNG/LPG tankers, and others) | 253 (31 %) | |

| Container ships | 142 (17.4 %) | |

| Other/Unknown (ro-ro, dredger, refrigerated cargo, tug, etc.) | 91 (11.1 %) | |

| General Cargo | 47 (5.7 %) | |

| Car carriers | 25 (3.1 %) |

4. Interview findings and discussion

Before the pandemic, Sampson and Ellis [20] called shipping companies to step up efforts and adopt various support measures to safeguard seafarers’ mental health (for the list of measures see the literature review section). In response to the pandemic and the crew change crisis, shipping companies did ramp up their effort. Apart from the measures recommended by Sampson and Ellis, some shipping companies also took specific measures to alleviate the impact of the crew change crisis. One shipping company manager mentioned four measures they had taken:

First, we provide a certain amount of free internet traffic to contact family. Second, we increase the monthly entertainment allowance. Third, we encourage the crew to have a dinner party twice a month. Four, we provide weekly notifications of the epidemic and crew change situation in different countries.

The fourth item dealt specifically with the crew change crisis. Another shipping company manager reported another three measures they had taken to help seafarers cope with the pandemic and crew change pressure:

-

1.

Stabilize the crew on board by increasing meal allowance for pandemic prevention, crew overtime service allowance (over 8 months of service), and crew extra overtime service allowance (over 10 months of service).

-

2.

Provide sufficient PPE and anti-pandemic supplies for the ship to make the crew feel safe and secure

-

3.

The company helps carry out mutual help and assistance for seafarers’ family members through family liaison stations and other forms, and the company helps solve family difficulties for crew members on board and stabilises the crew members on board by means of helping their families.

A third shipping company manager reported having contracted a professional mental health service provider to provide direct point-to-point professional counselling service to their seafarers when the latter need counselling on board.

In relation to professional counselling services, a Filipino Chief Engineer shared that when a rating on their vessel had a mental breakdown whilst on transit to a port in Southeast Asia, their company was instrumental in seeking professional help for the seafarer even before they reached their port of destination. In fact, one seafarer mental health service provider reported that the cases of seafarers calling their hotline continued to increase since the pandemic started [8], [9].

From the perspective of seafarers, the measures most commonly mentioned were frequent communication with family, frequent social events on board, such as parties, BBQ, timely crew changes, and adequate crew sizes. One Chinese seafarer stated in the interview:

My company had improved the quality of meals. We regularly organise group activities, during which small prizes are awarded. My family often has video chats with me to share news and stories.

Similarly, one Filipino seafarer reported that good relationships with colleagues were helpful:

My crewmates act as my second family. Interacting with them lightens my everyday mood and helps me avoid the negative effects of social isolation on my mental health.

Filipino seafarers were also likely to mention port chaplains who offered valuable support. This theme was corroborated by the interview with a port chaplain, who explained the support they provided:

We provide face-to-face chaplaincy, which is pastoral and spiritual care, and we provide counselling. All our chaplains are trained in post-trauma care and mental health awareness. We also provide a 24-h digital chaplaincy service that seafarers can access via our website so that they can speak to someone online at any time. We also provide the ‘We Care’ programme. It is an exciting new initiative designed to promote positive mental health and well-being for seafarers across the world.

When asked what support they thought was important but had not been provided, Filipino seafarers emphasized being vaccinated against COVID-19. In contrast, Chinese seafarers were more likely to mention that they were vaccinated already.

The above discussion reveals the themes identified from the interview data (the 16 themes not marked with an asterisk (*) symbol in Table 2). These 16 themes can be grouped into six categories. The first three categories are support directly provided by shipping companies. The remaining three categories are support offered by other stakeholders, such as family members, crew members, government authorities/agencies, and seafarer welfare organisations. It should be noted that ‘mutual support provided by family and crew members’ may need to be facilitated by policies and supportive measures from companies. For example, the frequency of ‘family communication’ may depend on the communication facilities available on-board the ship. Nevertheless, these types of support are directly provided by other stakeholders, and as a result, they are grouped into a separate category.

There may seem to be an overlap between ‘group recreational activities’ and ‘increase in recreational allowances’. The former is mutual support between crew members, and it can take place with or without monetary and/or policy support from the company. From a different perspective, companies’ increase in recreational allowances does not necessarily lead to more ‘group recreational activities’ since this fund can be used to buy recreational equipment, for example, computer-based games, which tend to be played alone or only by those few who are into these types of entertainment. Therefore, these two themes are separate. Similarly, ‘a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board’ and ‘casual counselling or support among crewmembers’ are also separate themes because the former could reduce the need for counselling, and the latter can take place between two or a few friendly crewmembers even if the overall atmosphere on-board is not positive.

5. Survey findings and discussion

Apart from the 16 themes drawn from the interview data, six additional support measures (those marked with an asterisk symbol in Table 2) were identified from the policy recommendations in the existing literature [6], [17], [20]. It should be noted that ‘outsourced professional counselling services’ and ‘seafarers’ mental health helplines’ are different. While the former are paid services provided by shipping companies, the latter are free services provided by maritime charities. Half of these 22 mental health supportive measures are provided directly by companies (the first three categories in Table 2), and the remaining half are provided by other stakeholders.

Understandably, seafarers experienced different types of support measures and their views on these measures varied. How widely each of these measures was adopted in the industry and how seafarers perceived them were explored in the second stage of the research, the findings of which are presented next.

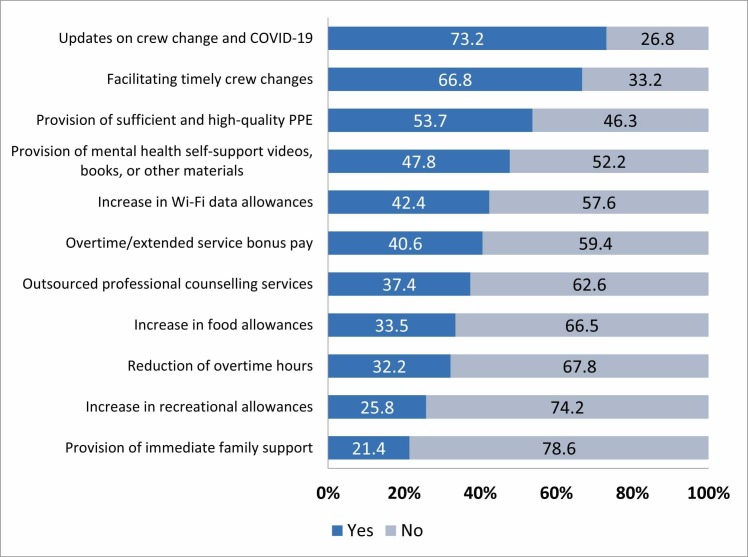

5.1. Support measures provided

Fig. 1 shows the results of whether the respondents received or experienced the 11 forms of support directly provided by companies. The most widely provided support measures were updates on crew change and COVID-19 information (73.2 %) and facilitating timely crew changes (66.8 %), which indicated the priority given by companies to address the crew change crisis. With respect to safety and health, provision of sufficient and high-quality PPE for infection control was reported by over half of the respondents (53.7 %)1, provision of mental health self-support videos, books, or other materials on board was experienced by nearly half of the respondents (47.8 %), and outsourced professional counselling services were offered to over a third of the respondents (37.4 %). Overall, support in the area of safety and health was less prioritized by companies. Pauksztat, Grech et al. [19] emphasised the importance of internet access onboard for the crew’s wellbeing. However, in this survey, the company’s support to increase Wi-Fi data allowances was experienced by only 42.4 % of the respondents. The least provided was the provision of support to the family. This may suggest that as most seafarers worked on short-term contracts nowadays [23], companies were less concerned about seafarers’ families.

Fig. 1.

Provision of support by companies.

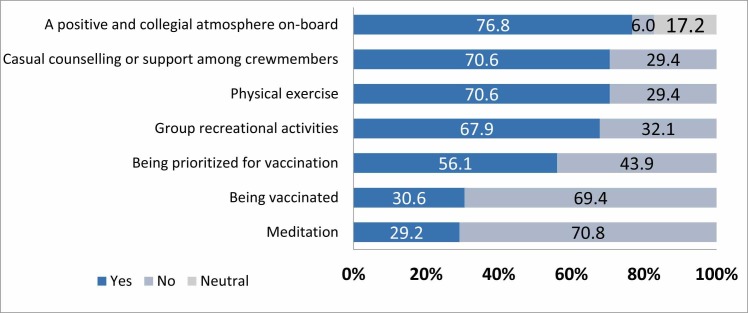

Fig. 2 shows the results of whether the respondents have received/experienced seven types of support provided by other stakeholders. On the one hand, the results showed that for most seafarers (76.8 %), the atmosphere in the workplace was positive, crew members supported each other (70.6 %), and they had collective recreational activities (67.9 %). Generally, it is evident that seafarers themselves found a way to support each other on board. On the other, the data indicated that the vaccination rate was quite low (30.6 %) at the time of this research, which was also validated by the interview data, indicating that States’ interventions to vaccination for seafarers were often ineffective. Finally, meditation was not widely practiced (29.2 %).

Fig. 2.

Provision of seven types of support by other stakeholders.

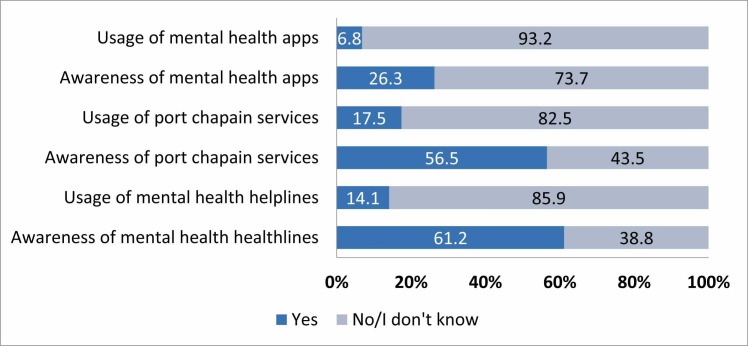

Concerning three types of support provided by other stakeholders – pastoral and spiritual care from port chaplains, seafarers’ mental health helplines, and seafarers’ mental health applications or apps, the respondents were asked not only whether they (or their colleagues) used such services but also whether they were aware of the existence of these services. Fig. 3 shows the results, which indicate that these services were not widely used by seafarers and that only a small percentage of them (26.3 %) were aware of mental health apps.

Fig. 3.

Awareness and usage of three types of support provided by other stakeholders.

The interview data as well as the literature [19], [20] highlighted the importance of frequent communication with family. Needless to say, seafarers do keep in touch with their families while working at sea, but how often they do so is likely to vary. The majority of the survey respondents (58.9 %) reported communicating daily with family, another 18.9 % weekly, 7.2 % on a bi-weekly basis, and the remaining 14.9 % monthly. As this question – How often they communicate with their families – cannot be transformed into a question of whether the support is provided or not, the result is not included in Fig. 2.

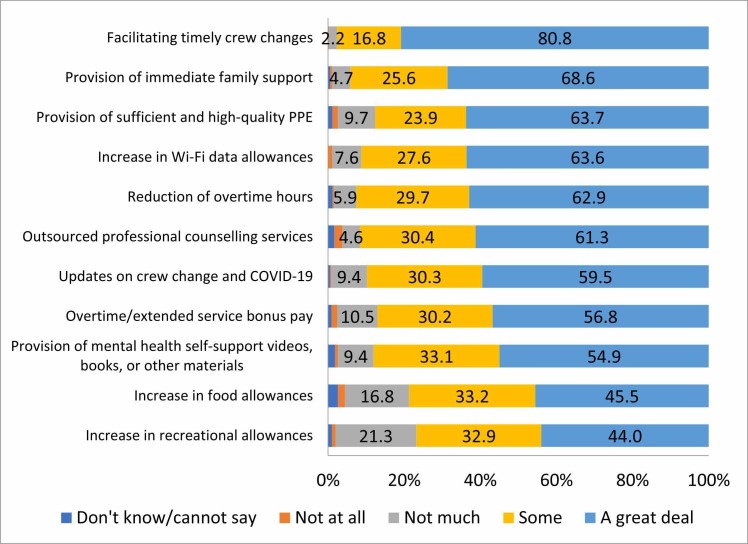

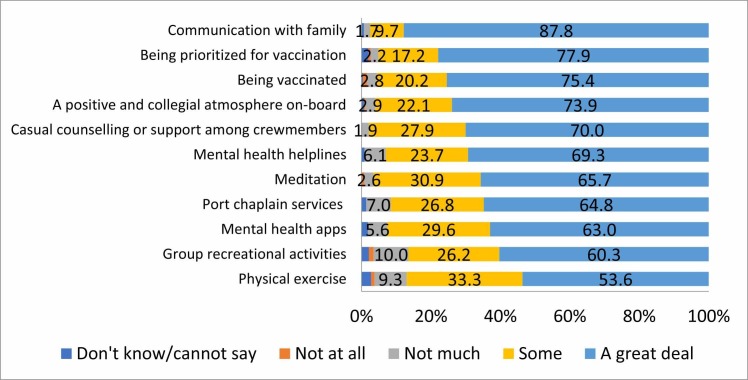

5.2. Perceived usefulness of the support measures

The respondents who indicated having made use of, received, or experienced a type of mental health support were also asked to answer a follow-up question, ‘How much help does it bring in terms of improving your mental health?’ Figs. 4 and 5 show respectively the results of company support and support from other stakeholders. Overall, the results indicate that all the 22 types of support were perceived to be helpful.

Fig. 4.

Perceived usefulness of support provided by companies.

Fig. 5.

Perceived usefulness of support provided by other stakeholders.

The five most effective support were communication with family, timely crew changes, being prioritised for vaccination, being vaccinated, and a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board. These findings highlighted the importance of four stakeholders, family, crew members, shipping companies, and government agencies. While social relations with family and other crew members have been duly highlighted in the previous research [6], [20], the pandemic has made crew change and vaccination issues come to the fore. The latter two issues require not only efforts from companies but perhaps more importantly facilitation of government agencies.

Interestingly, measures related to monetary support provided directly by companies (i.e. increase in recreational allowances, increase in food allowances, and overtime/extended services bonus pay) were perceived to be less effective than most of the other measures. This may indicate that such luxuries to their onboard work and life were not their urgent needs compared to measures directly relating to the safety and health of seafarers.

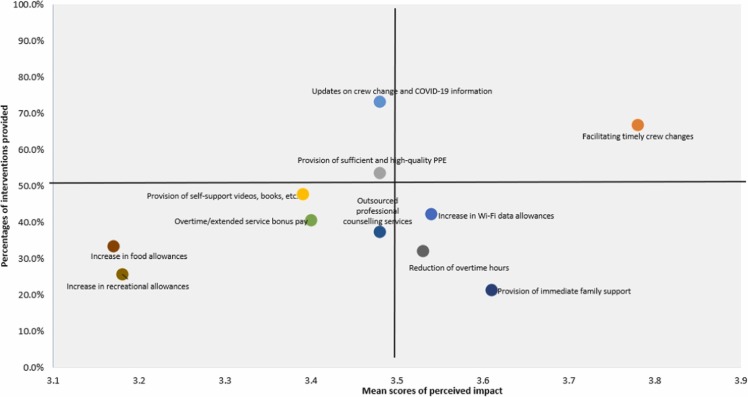

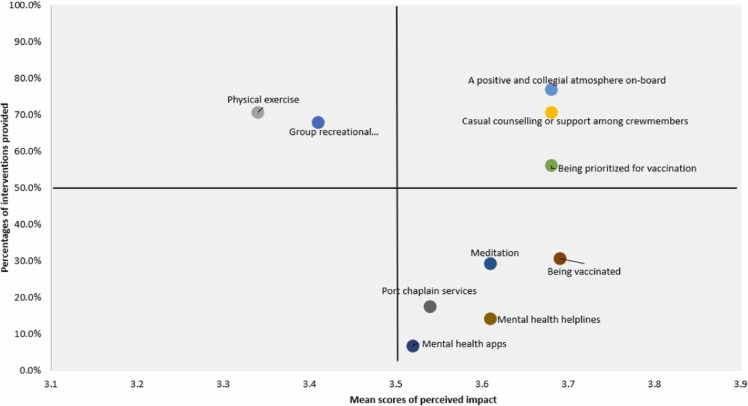

5.3. Discussion

To facilitate further analysis and discussion, findings related to whether seafarers received or made use of the various forms of support and the perceived usefulness are combined into two scatter plot graphs. Fig. 6 shows support provided directly by companies, and Fig. 7 relates to support provided by other stakeholders. In the questionnaire, five answers are provided to the questions ‘How much help does it bring in terms of improving your mental health?’ To generate the scatter plot graphs, the answers were assigned values as follows: not at all = 0, not much = 1, don’t know/cannot say = 2, some = 3, and a great deal = 4. As can be seen in Fig. 6, Fig. 7, all forms of support were perceived positively. Their mean values (the term ‘mean score’ or MS is used below) of perceived usefulness range from 3.17 (increase in food allowances) to 3.84 (communication with family).

Fig. 6.

Support provided by companies and their perceived effectiveness.

Fig. 7.

Support related to other stakeholders and their perceived effectiveness.

To aid the analysis, each scatter plot graph is divided into a 4-part quadrant graph. It is necessary to note that, although MS 3.5 is used as the midline, it is not a division line between negative and positive perceptions. Any MS above 2 can be regarded as positive, and since all types of support received an MS of more than 3, they are deemed to be positive. In this context, the forms of support on the left side of the MS 3.5 mid-line should not be understood as non-effective. It is worth noting that Fig. 7 does not include ‘communication with family’ because the question – How often they communicate with their families – cannot be transformed into a question of whether the support is provided or not.

The graphs can be used as a ‘decision matrix’ to inform companies and other stakeholders as to what types of interventions that they might prioritise to improve the mental health and wellbeing of seafarers in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. From the perspective of companies, if resources are limited, they should prioritise the forms of support on the right side of the MS 3.5 mid-line, such as ‘facilitating timely crew changes’, ‘provision of immediate family support’, ‘increase in Wi-Fi data allowance’, and ‘reduction of overtime hours’ (see Fig. 6). Additionally, they can enact company policies to encourage the creation of ‘a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board’ ships, and ‘casual counselling or support among crewmembers’ (see Fig. 7). While some of these measures have been repeatedly recommended in the literature, such as free Internet access, positive social relations, and reducing work hours [6], [19], [20], provision of support to immediate family when needed was also seen to be highly effective by the respondent in this study. This was understandable since it would be an added stress factor to the seafarer at sea if their family is not in a good state.

The support shown in the lower right quadrant should be of specific concern to the industry due to their high impact but low levels of provision or uptake such as ‘provision of immediate family support’, ‘increase in Wi-Fi data allowance’, ‘reduction of overtime hours’ (see Fig. 6) and ‘being vaccinated’ (see Fig. 7).

In Fig. 7, ‘mental health helplines’ and ‘port chaplain services’ are in the lower right quadrant, meaning that they are perceived to be highly effective but are not widely used. This may be due to cultural reasons or the respondents might not feel the need to use them. The strict quarantine policies in place in various ports around the world may have also limited the services provided by port chaplains to transitting ships. In the interviews, Chinese seafarers did not mention port chaplain services. As Fig. 3 shows, only slightly more than half of the respondents were aware of these services. As such, service providers may need to reconsider how they promote these services in collaboration with other stakeholders, emphasising the beneficial impact that seafarers reported from using them. Fig. 7 also reflected vaccination issues. At the time of research, the majority of the respondents had not been vaccinated and many of them were not prioritized for vaccination. As such, the national and international health authorities may need to step up their effort.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Seafarers working at sea face numerous occupational stressors, negatively affecting their mental health [6], [20], [23]. The current COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting crew change crisis further exacerbated the problem. In this context, the mental health of seafarers has been highlighted by the industry stakeholders [7], [8], [9], [10], and received significant attention from the maritime research community (e.g. [15]; [18]; [19]; [22]. While this body of literature unanimously pointed out that seafarers’ mental health is a serious concern during the current pandemic and made some policy recommendations, it remains unknown what support is available in the industry and how seafarers perceive the available support. This paper fills the knowledge gap.

Based on the literature [6], [19], [20] and interviews with seafarers and stakeholders, a total number of 22 mental health support measures were identified, including 11 measures directly provided by shipping companies and the remaining 11 related to other stakeholders. All the 11 support measures directly provided by companies were perceived to positively contribute to seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing, but only 3 of them (updates on crew change and COVID-19 information, facilitating timely crew changes, and provision of sufficient and high-quality PPE for infection control) were provided to more than half of the respondents. Among the 11 types of support related to other stakeholders, all of them were perceived to positively contribute to seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing, and six of them were experienced by more than half of the respondents. While all the stakeholders have a vital role to play in safeguarding seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing, the findings highlighted the importance of family, crew members, shipping companies, and government agencies, as they are associated with the most effective support measures, namely communication with family, timely crew changes, being prioritised for vaccination, being vaccinated, and a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board.

Given that although all the identified measures were positively received, some of them were not widely adopted or utilised, the following recommendations are proposed to companies and other stakeholders:

-

•

Overall, companies should improve their efforts to support seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing on board and be flexible in their provisions to adapt to the needs of seafarers during crises.

-

•

Companies prioritise the provision of ‘facilitating timely crew changes’, ‘provision of immediate family support’, ‘increase in Wi-Fi data allowance’, and ‘reduction of overtime hours’.

-

•

Companies make sure that sufficient and high-quality PPE for infection control are provided to seafarers.

-

•

Governments prioritise the inoculation of seafarers as essential workers or front-line workers

-

•

NGOs and other seafarer welfare organisations might revisit their communication strategies in relation to the ways of providing spiritual, pastoral, or guidance counselling services either via face-to-face encounters or virtual platforms, especially the poor subscription of the latter among seafarers.

-

•

NGOs find creative and robust strategies to improve the awareness of, access to and use of mobile mental health apps.

It should be acknowledged that this research has limitations. Firstly, the use of an online web-based survey limits the sample to respondents who are literate and comfortable with inputting information using computers or smartphones. The respondents in this study were generally young, with half of the sample population being under the age of 32. Younger people are generally perceived to be more tech-savvy, which may account for the higher response rates in this age group. Secondly, those without internet access or with very limited access either could not participate or would be hindered in participating in the study, thereby favouring respondents with access to a stable internet connection. Thirdly, data collection occurred a year and a half after the start of the pandemic. As a result, there may be a recall bias, and respondents' perceptions of, or experiences with, psychosocial interventions may have changed throughout the pandemic. Fourthly, because the study used a convenience sampling design, it is very difficult to determine whether those who chose to participate in the survey may be different from those who did not. Finally, there was a disproportionate frequency of respondents according to nationality, with the majority being Filipino seafarers.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the study offers further opportunities for research on seafarers’ mental health. Future research can, for example, explore the role of technology to support the mental health of seafarers. The application of behavioral science to improve seafarers’ mental health would be also an area of research in terms of empowering vulnerable groups of workers, such as seafarers. Mental health and psychological resilience education and training for cadets and seafarers may also be worth exploring (see [1].

Notes.

-

1.

It should be noted that in relation to ‘provision of sufficient and high-quality PPE for infection control’, five possible responses were provided instead of the binary ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. The 53.7 % positive responses in Fig. 1 were those who answered ‘Sufficient and high-quality PPE is provided’. The remaining 46.3 % negative responses included 11.3 % of the respondents indicating that high-quality PPE was provided but not sufficient for all crew, 25.3 % reporting sufficient PPE being provided but not high-quality, 8.2 % reporting being provided low-quality PPE and insufficient for all crew, and 1.3 % indicating no PPE for infection control provided at all.

-

2.

Again it should be noted that in relation to the three questions, the answers given were not simple ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Regarding group recreational activities, 33.4 % of the respondents reported having such activities ‘once in a month’, 15 % ‘once in two weeks’, 16.6 % ‘once in a week’, and 2.9 % ‘twice or more in a week’. Together, they constituted 67.9 % of the respondents who provided positive answers as shown in Fig. 2. In relation to physical exercise, the 70.6 % positive answers consisted of 16.7 % of the respondents who exercised ‘daily’, 24.7 % ‘once in two or three days’, 20.8 % ‘once every week’, and 8.4 % ‘once every two weeks’. The question related to ‘a positive and collegial atmosphere on-board offered five options: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree. In Fig. 2, the first two options (chosen by 24.8 % and 52 % of the respondents respectively) are combined into the ‘Yes’ response, the last two options (5.1 % and 0.9 % respectively) are combined into the ‘No’ response, and the remaining 17.2 % who answered ‘neither agree nor disagree’ were re-categorised into the ‘Neutral’ group.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lijun Tang: Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Sanley Abila: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Momoko Kitada: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Serafin Malecosio: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Karima Krista Montes: Data curation, Formal analysis.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the Lloyd's Register Foundation in the UK for funding this research (grant number: Sg2\100046). We would also like to thank the Chinese seafarers’ website (https://54seaman.com/) and maritime academies in the Philippines and Bangladesh for helping us distribute the questionnaire and thank all the seafarers and other key maritime stakeholders for participating in this research.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Abila S.S. Minding the gap: mental health education and standards of seafarer education. Handb. Res. Future Marit. Ind. 2022:69–90. (IGI Global) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abila S.S., Tang L. Trauma, post-trauma, and support in the shipping industry: The experience of Filipino seafarers after pirate attacks. Mar. Policy. 2014;46:132–136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abila S.S., Acejo I.L. Mental health of Filipino seafarers and its implications for seafarers’ education. Int. Marit. Health. 2021;72(3):183–192. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2021.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrei, D., Grech, M., Crous, R., Ho, R., McIlroy, T., Griffin, M., & Neal, A. (2018). Assessing the determinants and consequences of safety culture in the maritime industry. https://www. amsa. gov. au/safety-navigation/seafarer-welfare/research ….

- 5.Baygi F., Mohammadian Khonsari N., Agoushi A., Hassani Gelsefid S., Mahdavi Gorabi A., Qorbani M. Prevalence and associated factors of psychosocial distress among seafarers during COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03197-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackburn, P. (2020). Mentally Healthy Ships: Policy and Practice to Promote Mental Health on Board. ISWAN. https://www.seafarerswelfare.org/seafarer-health-information-programme/good-mental-health/mentally-healthy-ships.

- 7.Bush, D. (2021). Suicides at sea go uncounted as crew change crisis drags on. Lloyd’s List. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1135870/Suicides-at-sea-go-uncounted-as-crew-change-crisis-drags-on.

- 8.Clayton, R. (2021b). Seafarer mental health issues on the rise, study finds. Lloyd’s List. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1136047/Seafarer-mental-health-issues-on-the-rise-study-finds.

- 9.Clayton, R. (2021a). Seafarer mental health is not just a pandemic panic. Lloyd’s List. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1138465/Seafarer-mental-health-is-not-just-a-pandemic-panic.

- 10.Human Rights at Sea. (2021). Stamping on Seafarers’ Rights during the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.humanrightsatsea.org/news/new-independent-review-explores-violations-seafarers-rights-during-covid-19-and-calls-action.

- 11.IMO. (2020). 400,000 seafarers stuck at sea as crew change crisis deepens. https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/32-crew-change-UNGA.aspx.

- 12.IMO. (2022). UN agencies renew call to collaboratively support seafarers. https://imopublicsite.azurewebsites.net/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/UNJointStatementFeb2022.aspx.

- 13.Iversen R.T. The mental health of seafarers. Int. Marit. Health. 2012;63(2):78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonglertmontree W., Kaewboonchoo O., Morioka I., Boonyamalik P. Mental health problems and their related factors among seafarers: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12713-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaptan M., Olgun Kaptan B. The investigation of the effects of COVID-19 restrictions on seafarers. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2021:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefkowitz, R.Y., & Slade, M.D. (2019). Seafarer mental health study. ITF Seafarers’ Trust & Yale University.

- 17.McVeigh J., MacLachlan M., Kavanagh B. The positive psychology of maritime health. J. Inst. Remote Health Care. 2016;7(2):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauksztat B., Andrei D.M., Grech M.R. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of seafarers: a comparison using matched samples. Saf. Sci. 2022;146 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauksztat B., Grech M.R., Kitada M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on seafarers’ mental health and chronic fatigue: Beneficial effects of onboard peer support, external support and Internet access. Mar. Policy. 2022;137 doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampson H., Ellis N. Stepping up: the need for proactive employer investment in safeguarding seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021;48(8):1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampson, H., Ellis, N., Acejo, I., & Turgo, N. (2017). Changes in seafarers’ health 2011–2016: A summary report. Seafarers International Research Centre.

- 22.Slišković A. Seafarers’ well-being in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Work. 2020;67(4):799–809. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang, L., & Zhang, P. (2021). Human Res–ource Management in Shipping: Issues, Challenges, and Solutions. Routledge.

- 24.The Maritime Executive. (2022). Survey: Rising Sense of Dissatisfaction May Lead to Seafarer Attrition. The Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/survey-rising-sense-of-dissatisfaction-may-lead-to-seafarer-attrition.

- 25.UK Chamber of Shipping. (2017). Online mental health support is helping seafarers. https://www.ukchamberofshipping.com/latest/online-mental-health-support-helping-uk-seafarers/.

- 26.UNCTAD. (2021). Merchant fleet – UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics 2021. https://hbs.unctad.org/merchant-fleet/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.