Abstract

A gene cluster composed of nine open reading frames (ORFs) involved in Ni2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ sensing and tolerance in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 has been identified. The cluster includes an Ni2+ response operon and a Co2+ response system, as well as a Zn2+ response system previously described. Expression of the Ni2+ response operon (nrs) was induced in the presence of Ni2+ and Co2+. Reduced Ni2+ tolerance was observed following disruption of two ORFs of the operon (nrsA and nrsD). We also show that the nrsD gene encodes a putative Ni2+ permease whose carboxy-terminal region is a metal binding domain. The Co2+ response system is composed of two divergently transcribed genes, corR and corT, mutants of which showed decreased Co2+ tolerance. Additionally, corR mutants showed an absence of Co2+-dependent induction of corT, indicating that CorR is a transcriptional activator of corT. To our knowledge, CorR is the first Co2+-sensing transcription factor described. Our data suggest that this region of the Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 genome is involved in sensing and homeostasis of Ni2+, Co2+, and Zn2+.

At above critical concentrations, essential transition metal ions such as Ni2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ are toxic, being, for example, potent inhibitors of processes such as respiration and photosynthesis (see, for example, references 4, 22, 28, and 39). In addition, transition metals are required for the catalytic activity of a number of enzymes because of their redox activity and their high charge density, which allows the polarization of substrates and the stabilization of transition state intermediates. Bacteria have evolved sensing, sequestering, and transport systems that allow a precise homeostasis for these metals.

During the last years it has became clear that microbial Ni2+, Zn2+, and Co2+ uptake is mediated by nonspecific transport systems for divalent cations (33) and by high-affinity specific systems. Two types of high-affinity transporters have been identified: (i) multicomponent ATP-binding cassette transport systems (such as NikABCDE for Ni2+ or ZnuABC for Zn2+) (31, 37) and (ii) one-component transporters (such as NixA, UreH, HupN, and HoxN for Ni2+ and NhlF for Co2+) (12, 16, 23, 27, 29) which are integral membrane proteins with eight transmembrane-spanning helices.

Most of the studies on Co2+, Zn2+, and Ni2+ export and resistance have been carried out with the soil chemolithotrophic Alcaligenes strains (now designed Ralstonia), where three sequence-related divalent cation efflux operons, called czc (for Cd2+, Zn2+, and Co2+ resistance) (32), cnr (for Co2+ and Ni2+ resistance) (25), and ncc (for Ni2+, Co2+, and Cd2+ resistance) (47), have been described. Zn2+-dependent efflux ATPases have been recently characterized for Escherichia coli (zntA) (3) and for the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (ziaA) (51). ZntA and ZiaA belong to the P-type ATPase family (recently reviewed in reference 40), which includes the bacterial Cd2+ transporter CadA (34) and bacterial Cu2+ transporters (20, 35, 38).

Much less is known about how Ni2+, Zn2+, and Co2+ are sensed and how metal binding provokes protein conformational changes that determine regulatory responses. Two types of Zn2+-responsive regulators have been recently described. ZntR is a MerR-like transcriptional activator of zntA expression in E. coli (7). In contrast, Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 SmtB (19), Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 ZiaR (51), and Staphylococcus aureus ZntR (49) are transcriptional repressors that belong to the ArsR-SmtA family of helix-turn-helix DNA binding proteins. Although the overall ternary structure for these repressors is conserved, the metal binding site may be unique for each specific member of the family (9). Regulation of the czc efflux operon of Ralstonia eutropha is currently under active study, and at least three proteins, CzcD, CzcR, and CzcS, seem to be involved in metal sensing (55). The only nickel-specific responsive regulator reported is NikR, a Fur-related DNA binding protein that represses the transcription of the E. coli nikABCDE operon in the presence of high Ni2+ concentrations (11). Finally, no Co2+-specific sensor proteins have been reported so far.

We report in the present work the identification and characterization of a metal-regulated gene cluster in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. The cluster comprises nine open reading frames (ORFs) organized into five transcriptional units and seems to be responsible for Ni2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ homeostasis in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was grown photoautotrophically at 30°C in BG11 medium (43) supplemented with 1 g of NaHCO3 per liter (BG11C) and bubbled with a continuous stream of 1% (vol/vol) CO2 in air under continuous illumination (50 μmol of photons per m2 per s; white light from fluorescent lamps). For plate cultures, BG11C liquid medium was supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) agar. Kanamycin was added to a final concentration of 50 to 200 μg/ml when required. BG11C medium was supplemented with different concentrations of ZnSO4, CdCl2, CoCl2, CuSO4, NiSO4, and MgCl2 when indicated.

E. coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) grown in Luria broth medium as described previously (46) was used for plasmid construction and replication. E. coli BL21 grown in Luria broth medium supplemented with 2% glucose was used for expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–C-NrsD or GST proteins. E. coli strains were supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml when required.

Insertional mutagenesis of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 genes.

Loci slr0794, slr0796, slr0797, and sll0794 were inactivated by interruption with a kanamycin resistance cassette (C.K1) (14). For this, DNA fragments containing loci slr0794, slr0796, slr0797, and sll0794 were amplified by PCR from the cosmid CS1377 (provided by Kazusa DNA Research Institute) and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega). slr0794 was amplified by using oligonucleotides nit1 and nit2 (Table 1) and cloned into pGEM-T to generate pNIQ7. Targeting vectors were generated by inserting the C.K1 cassette into the EcoRI site of slr0794 in the same orientation as the nrs operon [pNIQ8(+)] or in the inverse orientation [pNIQ8(−)]. slr0796 was amplified by using oligonucleotides nrp1 and nrp2 (Table 1) and cloned into pGEM-T to generate pNIQ1. Targeting vectors were generated by inserting the C.K1 cassette into the BstEII site of slr0796 in the same orientation as the nrs operon [pNIQ2(+)] or in the inverse orientation [pNIQ2(−)]. slr0797 was amplified by using oligonucleotides cor1 and cor2 (Table 1) and cloned into pGEM-T to generate pNIQ10. The targeting vector was generated by inserting the C.K1 cassette into the EcoNI site of slr0797 in the opposite orientation to the slr0797 gene (pNIQ12). sll0794 was amplified by using oligonucleotides mr1 and mr2 (Table 1) and cloned into pGEM-T to generate pNIQ3. The targeting vector was generated by inserting the C.K1 cassette into the HindIII site of sll0794 in the same orientation as the sll0794 ORF [pNIQ4(+)]. All targeting vectors were used to transform Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 strain as previously described (15).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| nia3 | 5′CCCAATTTGAGGTGGTGTGATG3′ |

| nia4 | 5′ATAAAGGCAAGGGCTAGAGCAG3′ |

| nrp1 | 5′CCCATATGGGCAAACTACCGCCTATC3′ |

| nrp2 | 5′CGGGTAGTTTAAGGACTCGCC3′ |

| mr1 | 5′AGAAGGGGGAGTTACAACCATGC3′ |

| mr2 | 5′AGGCGAGTCCTTAAACTACCG3′ |

| cor1 | 5′GATCATCCCGATGCAGTGGCG3′ |

| cor2 | 5′GCACAGGGAGAAGCCACCACG3′ |

| nit1 | 5′CGGTGCGCTCTTCTTCTAAGG3′ |

| nit2 | 5′TTAGTGCGTAGTCCCCGATAG3′ |

| nrh1 | 5′GATGGAATTCAGGATTTTGGCACGAACATTC3′ |

| nrh2 | 5′AAAGCTCGAGAGGGAAAGGATGGTGAAAG3′ |

Correct integration and complete segregation of the mutant strains were tested by Southern blotting. For this, total DNA from cyanobacteria was isolated as previously described (8). DNA was digested and electrophoresed in 0.7% agarose gels in a Tris-borate-EDTA buffer system (46), and then DNA was transferred to nylon Z-probe membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). DNA probes were 32P labeled with a random-primer kit (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) using [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol).

RNA isolation and Northern blot hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated from 25-ml samples of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 cultures at the mid-exponential growth phase (3 to 5 μg of chlorophyll/ml). Extractions were performed by vortexing cells in the presence of phenol-chloroform and acid-washed baked glass beads (0.25- to 0.3-mm diameter; Braun, Melsungen, Germany) as previously described (17).

For Northern blot analyses, 15 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane and electrophoresed in 1.2% agarose denaturing formaldehyde gels. Transfer to nylon membranes (Hybond N-Plus; Amersham), prehybridization, hybridization, and washes were in accordance with Amersham instruction manuals. Probes for Northern blot hybridization were PCR synthesized using the following oligonucleotides pairs: nia3-nia4, probe a; nrp1-nrp2, probe b; mr1-mr2, probe c; and cor1-cor2, probe d (Table 1). DNA probes were 32P labeled with a random-primer kit (Pharmacia) using [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol). All of the filters were stripped and reprobed with a HindIII-BamHI 580-bp probe from plasmid pAV1100 that contains the constitutively expressed RNase P RNA gene (rnpB) from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (56). To determine counts per minute of radioactive areas in Northern blot hybridizations, an InstantImager Electronic Autoradiography apparatus (Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, Conn.) was used.

Purification of GST–C-NrsD and metal affinity chromatography.

The last 126 bp of the nrsD ORF, which encodes the last 42 amino acids of NrsD, was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides nrh1 and nrh2 (Table 1). The resulting DNA fragment was digested with EcoRI and XhoI and cloned into pGEX-4T-3 in phase with the GST gene to generate pGEX-C-NrsD. GST–C-NrsD fusion protein and GST were expressed in E. coli BL21 from the plasmids pGEX-C-NrsD and pGEX-4T-3, respectively. One liter of culture was grown in Luria broth medium supplemented with 2% glucose to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 2.5 h, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in 20 ml of phosphate-buffered saline buffer (150 mM NaCl, 16 mM Na2HPO4, 4 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.2) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cells were broken by sonication, and insoluble debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was then applied to a glutathione-agarose bead column (Pharmacia) (1-ml bed volume). After extensive washing with phosphate-buffered saline buffer, GST or GST–C-NrsD proteins were eluted with 3 ml of 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM reduced glutathione. Glutathione was then removed by gel filtration in a Sephadex G-25 column. Interaction of GST–C-NrsD or GST with Ni2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, or Mg2+ was investigated by metal ion affinity chromatography. A 0.5-ml portion of His-bind resin (Novagen) was loaded with 0.5 ml of 0.5 M ZnSO4, CoCl2, CuSO4, NiSO4, or MgCl2 in water and then equilibrated in 0.5 M sodium chloride–50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0) (buffer A). About 30 μg of purified GST–C-NrsD or GST proteins were applied to the columns. Unbound proteins were removed by washing with buffer A. Bound polypeptides were eluted with 0.5 ml of 0.4 M imidazole in buffer A. Proteins were then analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (24) and Coomassie blue staining. Quantities of bound and unbound proteins were determined by the method of Bradford (5).

Computer methods.

The BLAST program (1) was used to screen the translated nucleotides databases. The CLUSTAL X program was used to generate sequence alignments (53). Putative membrane-spanning regions were identify using different algorithms (18, 57).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A metal-regulated gene cluster in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

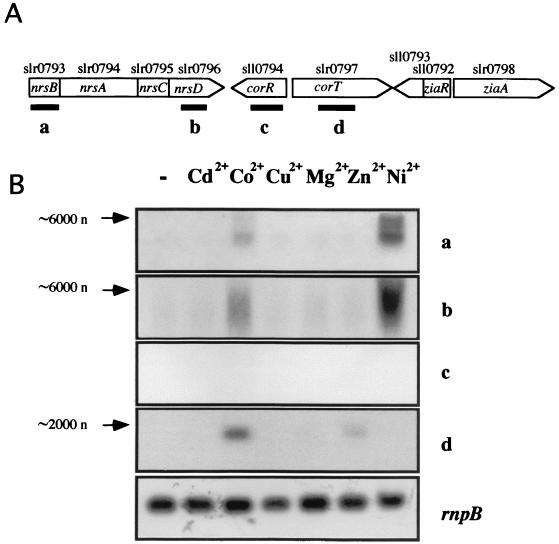

Analysis of the fully sequenced Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 genome (21) allowed us to identify a region of the chromosome containing three ORFs whose deduced amino acid sequences are clearly related to metal transport proteins (see below). The region extends 12 kb and comprises nine genes organized into five putative transcription units (Fig. 1A). ORF slr0798 has been reported to encode a Zn2+-dependent efflux ATPase (ZiaA) whose expression is Zn2+ dependent (51). A putative operon composed of two ORFs, sll0793 and sll0792, separated by 11 bp appears upstream from the ziaA gene and in the opposite orientation. sll0792 encodes ZiaR, the transcriptional repressor of ziaA. sll0793 is a putative membrane protein that does not share significant homology with any other protein in the EMBL-GenBank database (51). Metal-dependent expression of the remaining three putative transcriptional units was analyzed by Northern blotting. For this, four probes were used to hybridize total RNA obtained from mid-log-phase Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 cells grown in BG11C medium and exposed during 1 h to a 15 μM concentration of either ZnSO4, CdCl2, CoCl2, CuSO4, NiSO4, or MgCl2 (Fig. 1B). Control cells were not exposed to added metals. Probes a (internal to slr0793) and b (internal to slr0796) hybridized strongly with RNA obtained from Ni2+-exposed Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 cells and weakly with RNA from Co2+-exposed cells. Probe c (ORF sll0794) showed no hybridization with RNA from any of the conditions tested. Probe d, corresponding to ORF slr0797, hybridized strongly with RNA from Co2+-exposed cells and weakly with RNA from Zn2+-exposed cells. Transcript levels of the RNase P RNA (rnpB gene) (56) remained unchanged under all tested conditions (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Metal-dependent expression of the Synechocystis transition metal-resistant cluster. (A) ORF organization of the metal-regulated cluster from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. (B) Total RNA was isolated from mid-log-phase Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 cells exposed for 1 h to a 15 μM concentration of the indicated metal ions. Control cells were not exposed to added metals (−). Fifteen micrograms of total RNA was denatured, separated by electrophoresis in a 1.2% agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized with probes a to d as indicated in panel A (see Materials and Methods). The filters were stripped and rehybridized with an rnpB gene probe as a control. Estimated sizes of the transcripts (in nucleotides [n]) are indicated.

These results demonstrate the metal-dependent expression of two of the transcription units of the region. These data, together with the results of Thelwell et al. (51) about ziaA and ziaR genes, allow us to define the existence of a metal-regulated gene cluster in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

nrs is a nickel resistance operon.

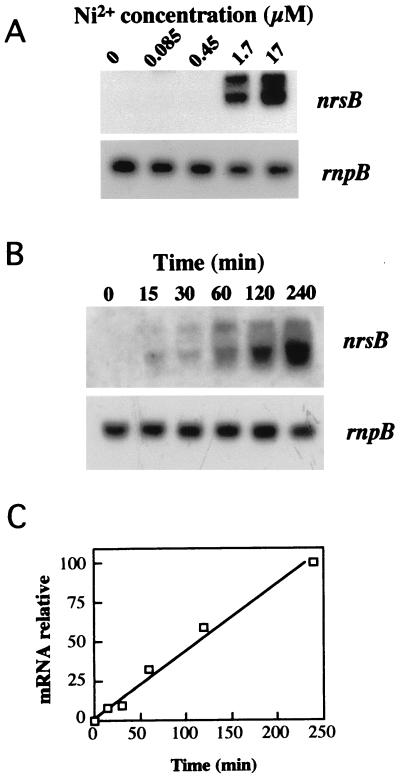

As shown above, a similar pattern of induction was found using probes from ORFs slr0793, and slr0796 (Fig. 1B). The fact that both probes hybridized with RNA of about 6 kb, together with the structure of the region, suggests that ORFs slr0793, slr0794, slr0795, and slr0796 form a transcriptional unit. Since Ni2+ provoked the highest induction of this transcription unit, the genes were named nrs for Ni2+ response system. The nrs induction dependence on concentration was studied by using Northern blot experiments. The operon was induced at Ni2+ concentrations of above 0.45 μM. An Ni2+ concentration of above 17 μM did not provoke higher accumulation of the nrs mRNA (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Time course analysis indicated that nrs mRNA was already induced 15 min after metal addition and increased almost linearly, at least during the first 4 h of treatment (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG. 2.

Ni2+ concentration dependence and time course of the expression of nrs. (A) The indicated concentration of NiSO4 was added to mid-log-phase Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 cells grown in BG11C medium. After 1 h, cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated, processed, and hybridized as described for Fig. 1, using an nrsB gene probe (probe a [Fig. 1]). (B) A 17 μM concentration of NiSO4 was added to mid-log-phase Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 cells grown in BG11C medium. Samples for total RNA isolation were taken at the indicated times. RNA was processed and hybridized as for Fig. 1, using an nrsB gene probe. (C) Radioactive signals of the time course experiment were quantified with a InstantImager Electronic Autoradiography apparatus. Levels of nrs operon mRNA were normalized with the rnpB signal, and plots of relative mRNA levels versus time were drawn.

In order to get information about the function of nrs genes, we have analyzed their deduced amino acid sequences. The ORF slr0793 (nrsB) and slr0794 (nrsA) products showed clear sequence similarity with the R. eutropha czcB and czcA gene products, respectively (32). While NrsA displays 35% identity and 55% similarity with CzcA throughout the entire amino acid sequence, NrsB and CzcB show significant similarity (34% identity and 45% similarity) only in a central 80-amino-acid region (from amino acid 54 to 132 of the NrsB sequence). The czcABC gene products form a membrane-bound protein complex catalyzing Co2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ efflux by a proton/cation antiporter in R. eutropha. CzcA is thought to be the inner membrane protein responsible for the efflux activity (48). CzcB is a periplasmic protein probably involved in membrane fusion that bridges the inner and the outer cell membranes of gram-negative bacteria (41). The protein encoded by ORF slr0795 (nrsC) is not homologous to proteins encoded by the czc or related operons. Interestingly, the NrsC carboxy-terminal (C-terminal) region shares significant similarity (26 to 30% identity in about 140 amino acids) with Neisseria gonorrhoeae autolysin A and bacteriophage-encoded lysozymes. In addition, computer analysis of the NrsC sequence indicated the existence of two putative transmembrane helices in the amino-terminal region of the protein (amino acids 24 to 47 and 70 to 89 from the NrsC sequence). Finally, the slr0796 (nrsD) product is a 445-amino-acid protein which shows significant amino acid sequence identity to the nreB gene product. The nre locus was identified as a low-level Ni2+ resistance determinant in Alcaligenes xylosoxidans 31A (47), different from the high-level Ni2+ resistance determinant (ncc) homologous to the czc system.

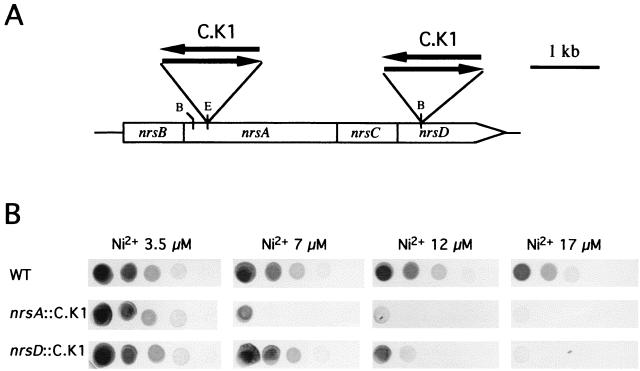

The homologies displayed by the Nrs proteins together with the pattern of expression of their genes suggested that the Nrs system is involved in Ni2+ and Co2+ tolerance in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. In order to verify this hypothesis, two different nrs mutants were generated by insertion of kanamycin resistance cassettes (C.K1) (14) into the nrsA and nrsD genes (Fig. 3A). In order to abolish polar effects, C.K1 cassettes were inserted in both orientations. Since the C.K1 cassette is lacking a transcription terminator (J. C. Reyes, unpublished observation), insertional mutagenesis in the same orientation as the nrs operon does not suppress transcription of the genes downstream of the insertion point. Similar results were obtained for both orientations, and therefore only mutants with the npt gene in the same orientation as the nrs genes are shown. nrsA::C.K1 and nrsD::C.K1 Synechocystis strains were viable, and their growth rates in BG11C medium were comparable to those of the wild-type strain (data not shown). Growth of nrsA::C.K1 and nrsD::C.K1 mutants was also examined in Zn2+-, Ni2+-, and Co2+-supplemented BG11C medium. Normal growth was observed in Zn2+- or Co2+-containing medium (data not shown); however, a reduced tolerance to Ni2+ was clearly observed for both nrs mutants (Fig. 3B). Interestingly the level of Ni2+ tolerance of the nrsA::C.K1 strain was lower than that of the nrsD::C.K1 strain. While nrsA::C.K1 mutants were unable to grow in medium containing 7 μM Ni2+, nrsD::C.K1 mutant cells were sensitive only to concentrations of above 12 μM Ni2+. These data suggest that NrsD and NrsA might form part of two independent systems for Ni2+ tolerance. This is in good agreement with the data reported for A. xylosoxidans, where the ncc and nre loci form two independent systems for Ni2+ resistance (47). Since nrsB- and nrsA-homologous genes has been found to be involved in heavy-metal efflux, it seems logical to speculate that the NrsB and NrsA proteins form an Ni2+ efflux system in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. A difference between the Nrs system from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and the Czc system from R. eutropha is the lack of a CzcC homolog in the cyanobacterial Ni2+ response system. Deletion of the czcC gene results in a loss of Cd2+ and Co2+ resistance, but not Zn2+ resistance, suggesting that CzcC is involved in substrate specificity but not in the transport activity of the complex (32).

FIG. 3.

Ni2+ tolerance of Synechocystis nrsA::C.K1 and nrsD::C.K1 mutants. (A) Schematic representation of the nrs genomic region in the wild-type strain and sites of insertion of the C.K1 cassette in the nrsA::C.K1 and nrsD::C.K1 mutants. The C.K1 cassette was inserted in both orientations, as indicated. B, BstEII; E, EcoRI. (B) Ni2+ tolerance of wild-type Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (WT) and Synechocystis nrsA::C.K1 and nrsD::C.K1 mutants. Mutants with the C.K1 cassette in the same orientation as the nrs genes are shown. Tenfold serial dilutions were spotted on BG11C plates, supplemented with the indicated concentrations of NiSO4, and photographed after 10 days of growth.

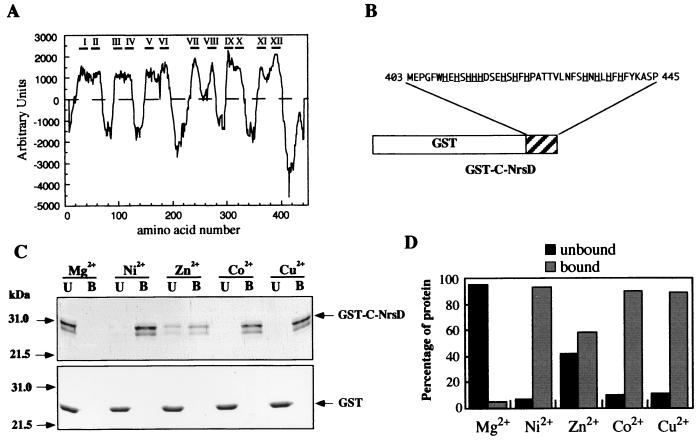

The amino-terminal part of NrsD is a metal binding domain.

As previously mentioned, the closest NrsD homolog is the product of the A. xylosoxidans nreB gene, which has not been characterized. NrsD shows also very significant sequence similarity to several members of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) (36). MFS transporters are single polypeptides, containing 12 to 14 transmembrane-spanning regions, capable of transporting small solutes in response to a chemiosmotic gradient. Computer analysis of the NrsD amino acid sequence indicated the existence of 12 putative transmembrane helices distributed along the first 400 amino acids of the protein (Fig. 4A). These data, taken together with the phenotype of the nrsD mutants, suggest that NrsD is a member of the MFS of permeases involved in Ni2+ export. Interestingly, the NrsD protein does not show sequence similarity with a family of well-characterized Ni2+ permeases including UreH, HupN, and HoxN (12, 16, 27). These proteins show a common topology, with eight membrane-spanning segments. The second transmembrane helix includes a putative Ni2+ binding motif (HX4DH) whose mutation completely abolishes transport activity (13). This motif is not present in the putative transmembrane helices of NrsD. The strongly hydrophilic C-terminal part of NrsD contains a remarkably high number of histidine residues (12 out of 40 amino acids), which are generally considered to be potential metal ligands. In order to test whether this domain of NrsD is involved in metal binding, a chimeric protein comprising amino acids 403 to 445 of NrsD (C-NrsD) fused to the GST was expressed in E. coli (Fig. 4B). The GST–C-NrsD fusion protein was purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione-agarose. One major band of about 31 kDa (fusion protein between the GST [26 kDa] and the C-NrsD domain [5 kDa]) was visible after SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Interaction of GST or GST–C-NrsD with Ni2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, and Mg2+ was evaluated by metal affinity chromatography. For this, GST or GST–C-NrsD fusion proteins were loaded into His-bind resin chelating columns charged with the appropriate ions. About 90% of the GST–C-NrsD fusion protein was retained by the Ni2+-, Co2+-, and Cu2+-containing columns (Fig. 4C and D). About 60% of the GST–C-NrsD protein was also retained in the Zn2+-containing column. In contrast, GST–C-NrsD was not retained in the Mg2+-charged column (Fig. 4C and D). GST protein was not retained by any of the metal columns (Fig. 4C). These results support a role for the hydrophilic C-terminal part of NrsD as a metal binding domain. Our data suggest that this domain has a low specificity for metal binding, which has been previously shown for histidine-rich proteins (58). Histidine-rich domains have been found in UreE, HypB, and CooJ, which are small soluble proteins that are involved in processing Ni2+ for urease and hydrogenases (30, 42, 58). Interestingly, it has been shown that a truncated version of UreE which lacks the histidine-rich C-terminal region still binds Ni2+ and functions in vivo (6). Organisms with high-affinity uptake systems for Ni2+ have UreE-like proteins lacking the histidine-rich region (26), leading to the suggestion that the histidine-rich region functions to store Ni2+ ions (6). One possibility is that the histidine-rich C-terminal region of NrsD is used to store metal ions that are going to be transported.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of NrsD protein. (A) Prediction of NrsD membrane-spanning regions. The probability of transmembrane regions was calculated by using the TM-pred program (18). (B) Schematic representation of GST–C-NrsD protein. The chimeric protein comprises amino acids 403 to 445 of NrsD (C-terminal domain, C-NrsD) fused to GST. Histidine residues are underlined. (C and D) The interaction of GST or GST–C-NrsD proteins with metals was analyzed by metal chromatography. His-bind resin columns were loaded with either Mg2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Co2+, or Cu2+. About 30 μg of purified GST–C-NrsD or GST was applied to the columns. Unbound (lanes U) (flowthrough) and bound (lanes B) (imidazole-eluted) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and Coomassie blue staining (C), and protein was quantified by the method of Bradford (5). (D).

A MerR-related transcription activator involved in Co2+ sensing.

The nrs operon was induced by Co2+ (Fig. 1), suggesting that it might be involved in Co2+ tolerance. However, nrsD::C.K1 and nrsA::C.K1 mutant cells did not show reduced tolerance for Co2+. These data together with the pattern of hybridization obtained with probe d in Fig. 1 suggested the existence of an alternative system involved in Co2+ homeostasis. The ORF slr0797 product shares clear homology with cation-transporting P-type ATPases, such as the bacterial Cd2+ transporter CadA or the bacterial Cu2+ transporters CtaA, PacS, CopA, and CopB (reviewed in reference 40). The closest homolog to the slr0797 product is ZiaA (slr0798), the Zn2+-dependent ATPase from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (51), encoded by another gene of the cluster (Fig. 1A). Induction of slr0797 mRNA by Co2+ suggested that the slr0797 gene product might be involved in the homeostasis of this cation. This hypothesis was investigated by interrupting the slr0797 gene with a kanamycin resistance cassette (Fig. 5A) and testing the metal tolerance of the resulting mutant strain. Growth of slr0797::C.K1 mutants in Zn2+-, Ni2+-, and Co2+-supplemented BG11C medium was examined. Normal growth was observed in Zn2+- or Ni2+-containing medium (data not shown); however, a reduced tolerance to Co2+ was detected (Fig. 5B). This result indicates that the slr0797 ORF is involved in Co2+ tolerance. Since the slr0797 product shows clear homology with cation-transporting P-type ATPases, our data point to the slr0797 product as a Co2+ efflux pump. Based on this role in Co2+ transport, the slr0797 ORF was designed corT (for cobalt response transporter). The fact that corT is also weakly induced by Zn2+ suggests that this ATPase might be involved in Zn2+ tolerance. However, the corT mutant cells did not show reduced Zn2+ tolerance. A probable reason for this result is the existence of a Zn2+-specific ATPase, ZiaA, able to control Zn2+ homeostasis (51). Another possibility is that Zn2+ is a gratuitous inducer for corT gene expression.

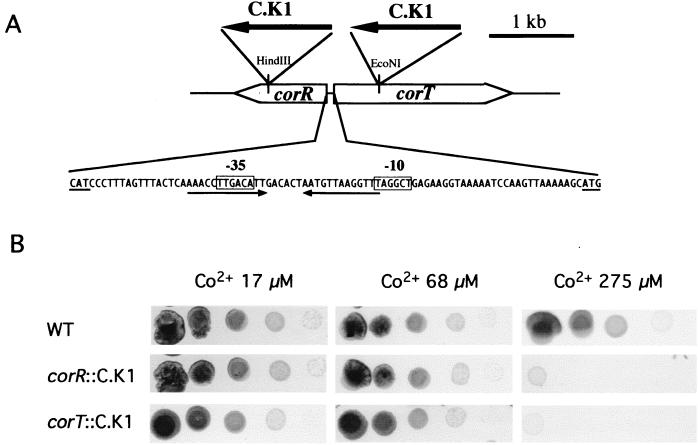

FIG. 5.

Co2+ tolerance of Synechocystis corT::C.K1 and corR::C.K1 mutants. (A) Schematic representation of the corR-corT genomic region. The sites of insertion of the C.K1 cassette in the corT::C.K1 and corR::C.K1 mutants are shown. The nucleotide sequence of the corR-corT intergenic region is also shown. Putative −10 and −35 boxes of the corT promoter are boxed. A hyphenated inverted repeat (13-6-13) with one mismatch is marked with arrows. The start codons of corT and corR are underlined. (B) Co2+ tolerance of wild-type Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (WT) and the corT::C.K1 and corR::C.K1 mutants. Tenfold serial dilutions were spotted on BG11C plates, supplemented with the indicated concentrations of CoCl2, and photographed after 10 days of growth.

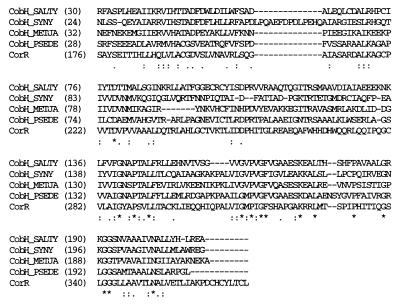

At 81 bp upstream of corT and in the opposite orientation appears the ORF sll0794 (Fig. 1A). Sequence analysis revealed that sll0794 encodes a 370-amino-acid protein with two different domains. Thus, the amino-terminal domain (amino acids 10 to 70) shares strong similarity with the DNA binding domains of components of the MerR family of DNA binding proteins (50). In contrast, the C-terminal region, from amino acid 170 to 358, shows significant similarity (30% identity in 180 amino acids) to precorrin isomerases (precorrin-8x methylmutases) from different origins (Fig. 6) (10, 52). Precorrin isomerase, the product of the gene cobH, is involved in the biosynthetic pathway of cobalamin. In cobalamin a cobalt atom is held by coordination bonds to the nitrogen atoms of the four pyrrole rings of corrin (reviewed in reference 44). Precorrin isomerase catalyzes the synthesis of hydrogenobyrinic acid from precorrin-8x by transferring a methyl group from C-11 to C-12. It has been shown that precorrin isomerase is able to tightly bind hydrogenobyrinic acid, a class of corrinoid ring (52). It is also known that corrinoids are able to bind cobalt under certain conditions (54). The fact that the sll0794 gene product contains a domain homologous to precorrin isomerase and another domain involved in DNA binding suggested the attractive hypothesis that this protein was involved in transcriptional regulation mediated by Co2+. We have been unable to detect the corR mRNA (Fig. 1B), indicating that CorR is expressed at very low levels, consistent with its possible regulatory role. Because of this regulatory role, sll0794 was named corR (for cobalt response regulator).

FIG. 6.

Sequence alignment of the CorR C-terminal domain with precorrin isomerase (CobH) amino acid sequences from different origins. COBH_SALTY, CobH from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium; COBH_SYNY, CobH from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803; COBH_METJA, CobH from Methanococcus jannaschii; COBH_PSEDE, CobH from Pseudomonas denitrificans. Identical amino acids are marked with asterisks; conservative changes are marked with colons or dots (as defined by CLUSTAL X [53]).

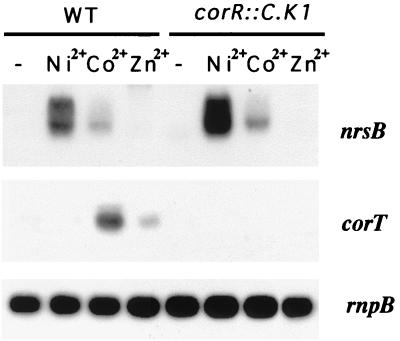

In order to verify this hypothesis, the corR gene was interrupted by a kanamycin resistance cassette (Fig. 5A). The resulting Synechocystis mutant strain (corR::C.K1) was viable and grew normally in BG11C medium. Growth of the corR::C.K1 mutant strain was also examined in Zn2+-, Ni2+-, and Co2+-supplemented BG11C medium. Normal growth was observed in Zn2+- or Ni2+-containing medium (data not shown); however, a reduced growth in Co2+-containing medium was observed (Fig. 5B). These data, together with the results of the sequence analysis commented on above, suggested a role of CorR as a positive regulator of a Co2+ response element. One obvious candidate to be regulated by CorR was the corT gene. Expression of different transcriptional units of the cluster was analyzed in the corR::C.K1 mutant. Northern blot experiments showed that Co2+- and Zn2+-dependent induction of the corT mRNA was absent in corR::C.K1 cells (Fig. 7). In contrast, Ni2+- or Co2+-dependent induction of the nrs operon was not affected in this strain (Fig. 7). These data indicate that CorR is a transcriptional activator of corT expression, which responds both to Co2+ and, to a lesser extent, to Zn2+. Our data also indicate that the low Co2+ tolerance of the corR::C.K1 strain is a consequence of the absence of corT induction.

FIG. 7.

Loss of corT induction in the corR::C.K1 mutant. Total RNA was isolated from mid-log-phase wild-type Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (WT) or from Synechocystis corR::C.K1 mutant cells exposed for 1 h to a 15 μM concentration of the indicated metal ions. Control cells were not exposed to added metals (−). RNA was isolated, processed, and hybridized as described for Fig. 1, using an nrsB or a corT gene probe (probes a and d, respectively [Fig. 1A]). The filters were stripped and rehybridized with an rnpB gene probe as a control.

Promoters dependent on MerR-like proteins have an unusual structure (2, 50). Unlike regular sigma-70-dependent prokaryotic promoters, in which the −35 and −10 consensus elements are separated by 16- to 18-bp-long spacers, the promoters regulated by MerR-type proteins have 19- to 20-bp-long spacers. In typical MerR-like-dependent promoters this spacer region contains long inverted-repeat sequences which are the DNA binding sites for the MerR-like proteins. Sequence analysis of the corR-corT intergenic region revealed a putative MerR-type promoter with a 20-bp spacer and a 13-bp–13-bp inverted repeat in the form AAACCTTGACATT-N6-AATGTTAAGGTTT (Fig. 5A). Our present hypothesis is that this inverted repeat is the DNA target for CorR, which in the presence of Co2+ is able to promote transcriptional activation of corT. While this article was under review Rutherford et al. reported experiments that confirm that CorR binds to the corR-corT intergenic region (45). How is CorR able to sense Co2+? One obvious possibility is that the precorrin isomerase-homologous domain of CorR binds some class of corrinoid ring. Co2+ binding to the corrinoid ring would provoke a change in the transcriptional function of the protein. However, Rutherford et al. show data suggesting that the metal and the corrinoid ring bind to different domains (45). Their model predicts that the binding of hydrogenobyrinic acid to the precorrin isomerase domain of CorR prevents cobalt-mediated conformational change required for activation. The protein CorR is an interesting example of how an enzymatic protein domain (precorrin isomerase) has been adapted during evolution to a sensing and regulatory function.

In conclusion, we have described the existence in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 of a gene cluster composed of nine ORFs involved in heavy-metal tolerance. While five of the gene products seem to carry out functions related to metal export, two other genes encode proteins involved in metal sensing and regulation. The remaining two proteins encoded by the cluster show no clear homologs in the databases, and their role in metal resistance is an open question. Finally, how and why nine genes with related functions have been clustered in a region of the Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 genome are interesting questions that remain to be addressed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Kazusa DNA Research Institute and S. Tabata for providing CS1377 cosmid DNA. We are grateful to E. Santero for critical reading of the manuscript.

M. García-Domínguez was the recipient of a fellowship from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Cultura. This work was supported by grant PB97-0732 from DGESIC and by Junta de Andalucía (group CV1-0112).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari A Z, Bradner J E, O'Halloran T V. DNA-bend modulation in a repressor-to-activator switching mechanism. Nature. 1995;374:371–375. doi: 10.1038/374370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard S J, Hashim R, Membrillo-Hernandez J, Hughes M N, Poole R K. Zinc(II) tolerance in Escherichia coli K-12: evidence that the zntA gene (o732) encodes a cation transport ATPase. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard S J, Hughes M N, Poole R K. Inhibition of the cytochrome bd-terminated NADH oxidase system in Escherichia coli K-12 by divalent metal cations. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brayman T G, Hausinger R P. Purification, characterization, and functional analysis of a truncated Klebsiella aerogenes UreE urease accessory protein lacking the histidine-rich carboxyl terminus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5410–5416. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5410-5416.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brocklehurst K R, Hobman J L, Lawley B, Blank L, Marshall S J, Brown N L, Morby A P. ZntR is a Zn(II)-responsive MerR-like transcriptional regulator of zntA in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y, Wolk C P. Use of a conditionally lethal gene in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 to select for double recombinants and to entrap insertion sequences. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3138-3145.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook W J, Kar S R, Taylor K B, Hall L M. Crystal structure of the cyanobacterial metallothionein repressor SmtB: a model for metalloregulatory proteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:337–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crouzet J, Cameron B, Cauchois L, Rigault S, Rouyez M C, Blanche F, Thibaut D, Debussche L. Genetic and sequence analysis of an 8.7-kilobase Pseudomonas denitrificans fragment carrying eight genes involved in transformation of precorrin-2 to cobyrinic acid. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5980–5990. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5980-5990.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Pina K, Desjardin V, Mandrand-Berthelot M A, Giordano G, Wu L F. Isolation and characterization of the nikR gene encoding a nickel-responsive regulator in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:670–674. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.670-674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eitinger T, Friedrich B. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and heterologous expression of a high-affinity nickel transport gene from Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3222–3227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eitinger T, Wolfram L, Degen O, Anthon C. A Ni2+ binding motif is the basis of high affinity transport of the Alcaligenes eutrophus nickel permease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17139–17144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elhai J, Wolk C P. A versatile class of positive-selection vectors based on the nonviability of palindrome-containing plasmids that allows cloning into long polylinkers. Gene. 1988;68:119–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90605-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferino F, Chauvat F. A promoter-probe vector-host system for the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis PCC6803. Gene. 1989;84:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90499-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu C, Javedan S, Moshiri F, Maier R J. Bacterial genes involved in incorporation of nickel into a hydrogenase enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5099–5103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Domínguez M, Florencio F J. Nitrogen availability and electron transport control the expression of glnB gene (encoding PII protein) in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:723–734. doi: 10.1023/a:1005846626187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. TMbase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1993;347:166. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huckle J W, Morby A P, Turner J S, Robinson N J. Isolation of a prokaryotic metallothionein locus and analysis of transcriptional control by trace metal ions. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanamaru K, Kashiwagi S, Mizuno T. A copper-transporting P-type ATPase found in the thylakoid membrane of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus species PCC7942. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiner D. Inhibition of the respiratory system in Azotobacter vinelandii by divalent transition metal ions. FEBS Lett. 1978;96:364–366. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komeda H, Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. A novel transporter involved in cobalt uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:36–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liesegang H, Lemke K, Siddiqui R A, Schlegel H G. Characterization of the inducible nickel and cobalt resistance determinant cnr from pMOL28 of Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:767–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.767-778.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lutz S, Jacobi A, Schlensog V, Bohm R, Sawyers G, Bock A. Molecular characterization of an operon (hyp) necessary for the activity of the three hydrogenase isoenzymes in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:123–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeda M, Hidaka M, Nakamura A, Masaki H, Uozumi T. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of thermophilic Bacillus sp. strain TB-90 urease gene complex in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:432–442. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.432-442.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallick N, Rai L C. Metal induced inhibition of photosynthesis, photosynthetic electron transport chain and ATP content of Anabaena doliolum and Chlorella vulgaris: interaction with exogenous ATP. Biomed Environ Sci. 1992;5:241–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mobley H L, Garner R M, Bauerfeind P. Helicobacter pylori nickel-transport gene nixA: synthesis of catalytically active urease in Escherichia coli independent of growth conditions. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulrooney S B, Hausinger R P. Sequence of the Klebsiella aerogenes urease genes and evidence for accessory proteins facilitating nickel incorporation. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5837–5843. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5837-5843.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro C, Wu L F, Mandrand-Berthelot M A. The nik operon of Escherichia coli encodes a periplasmic binding-protein-dependent transport system for nickel. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1181–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nies D H, Nies A, Chu L, Silver S. Expression and nucleotide sequence of a plasmid-determined divalent cation efflux system from Alcaligenes eutrophus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7351–7355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nies D H, Silver S. Metal ion uptake by a plasmid-free metal-sensitive Alcaligenes eutrophus strain. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4073–4075. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.4073-4075.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nucifora G, Chu L, Misra T K, Silver S. Cadmium resistance from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258 cadA gene results from a cadmium-efflux ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3544–3548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odermatt A, Suter H, Krapf R, Solioz M. Primary structure of two P-type ATPases involved in copper homeostasis in Enterococcus hirae. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12775–12779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pao S S, Paulsen I T, Saier M H., Jr Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patzer S I, Hantke K. The ZnuABC high-affinity zinc uptake system and its regulator Zur in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1199–1210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phung L T, Ajlani G, Haselkorn R. P-type ATPase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus 7942 related to the human Menkes and Wilson disease gene products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9651–9654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rai P K, Mallick N, Rai L C. Effect of Cu and Ni on growth, mineral uptake, photosynthesis and enzyme activities of Chlorella vulgaris at different pH values. Biomed Environ Sci. 1994;7:56–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rensing C, Ghosh M, Rosen B P. Families of soft-metal-ion-transporting ATPases. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5891–5897. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5891-5897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rensing C, Pribyl T, Nies D H. New functions for the three subunits of the CzcCBA cation-proton antiporter. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6871–6879. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.6871-6879.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rey L, Imperial J, Palacios J M, Ruiz-Argueso T. Purification of Rhizobium leguminosarum HypB, a nickel-binding protein required for hydrogenase synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6066–6073. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6066-6073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J B, Herdman M, Stanier R Y. Genetics assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roth J R, Lawrence J G, Bobik T A. Cobalamin (coenzyme B12): synthesis and biological significance. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:137–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rutherford J C, Cavet J S, Robinson N J. Cobalt-dependent transcriptional switching by a dual-effector MerR-like protein regulates a cobalt-exporting variant CPx-type ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25827–25832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt T, Schlegel H G. Combined nickel-cobalt-cadmium resistance encoded by the ncc locus of Alcaligenes xylosoxidans 31A. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7045–7054. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7045-7054.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silver S, Phung L T. Bacterial heavy metal resistance: new surprises. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:753–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh V K, Xiong A, Usgaard T R, Chakrabarti S, Deora R, Misra T, Jayaswal R K. ZntR is an autoregulatory protein and negatively regulates the chromosomal zinc resistance operon znt of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:200–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Summers A O. Untwist and shout: a heavy metal-responsive transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3097–3101. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3097-3101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thelwell C, Robinson N J, Turner-Cavet J S. An SmtB-like repressor from Synechocystis PCC 6803 regulates a zinc exporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10728–10733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thibaut D, Couder M, Famechon A, Debussche L, Cameron B, Crouzet J, Blanche F. The final step in the biosynthesis of hydrogenobyrinic acid is catalyzed by the cobH gene product with precorrin-8x as the substrate. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1043–1049. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.1043-1049.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tolls. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toohey J I. A vitamin B12 compound containing no cobalt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:934–942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.3.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van der Lelie D, Schwuchow T, Schwidetzky U, Wuertz S, Baeyens W, Mergeay M, Nies D H. Two-component regulatory system involved in transcriptional control of heavy-metal homoeostasis in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:493–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.d01-1866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vioque A. Analysis of the gene encoding the RNA subunits of ribonuclease P from cyanobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6331–6337. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.23.6331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Heijne G. Membrane protein structure prediction, hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90934-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watt R K, Ludden P W. The identification, purification, and characterization of CooJ. A nickel-binding protein that is co-regulated with the Ni-containing CO dehydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10019–10025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.10019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]