Overview

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive cutaneous tumor that combines the local recurrence rates of infiltrative non-melanoma skin cancer along with the regional and distant metastatic rates of thick melanoma.1–16 Several large reviews document the development of local recurrence in 25% to 30% of all cases of MCC, regional disease in 52% to 59%, and distant metastatic disease in 34% to 36%.1,16,17 MCC has a mortality rate that exceeds that of melanoma;18 overall 5-year survival rates range from 30% to 64%.3,19 A history of extensive sun exposure is a risk factor for MCC. Older white men (≥ 65 years) are at higher risk for MCC, which tends to occur on the areas of the skin that are exposed to sun.20

The NCCN Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer Panel has developed guidelines outlining treatment of MCC to supplement the squamous cell and basal cell skin cancer guidelines (see NCCN Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers Guidelines [to view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit the NCCN Web site at www.nccn.org]).21 MCC is a rare tumor; therefore, no prospective, statistically significant data are available to verify the validity of any prognostic features or treatment outcomes. The panel relied on trends that are documented in smaller, individual studies and in meta-analyses and their own collective experiences.

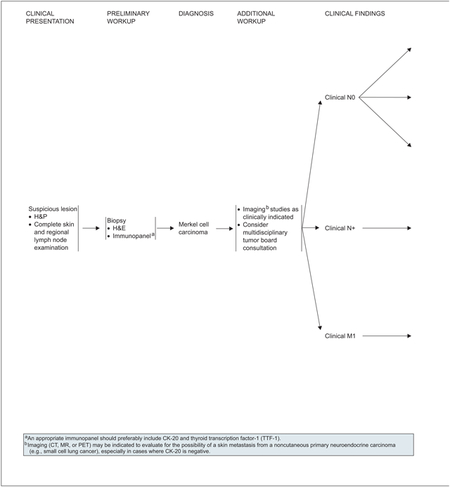

Diagnosis and Workup

Initial workup of a suspicious lesion starts with a complete examination of skin and regional lymph nodes followed by biopsy (see page 324). The primary goal in biopsy of an MCC is to confirm the diagnosis. The tumor rarely presents clinically as a classic lesion when MCC is expected to be the main diagnosis. The histologic diagnosis may be challenging, because MCC is similar to various other widely recognized small, round, blue cell tumors. The most difficult differentiation is often between primary MCC and metastatic small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Initial diagnosis of MCC in the primary lesion by hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) should be further confirmed by performing immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

An appropriate immunopanel should preferably include cytokeratin 20 (CK-20) and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), which often provide the greatest sensitivity and specificity to exclude small cell lung cancer (SCLC).22–24 CK-20 is a very sensitive marker for MCC, because it is positive in 89% to 100% of tumors. TTF-1 is expressed in 83% to 100% of SCLC but is consistently absent in MCC. Other immunohistochemical markers, including chromogranin A, synaptophysin, neurofilament protein, neuron-specific enolase, leukocyte common antigen (CD45), S-100 protein, and pancytokeratin (panCK), may be used in addition to CK-20 and TTF-1 to exclude other diagnostic considerations.5 Most primary and metastatic MCCs also express KIT receptor tyrosine kinase (CD117).25

Additional workup of patients with MCC includes imaging studies as clinically indicated, which parallels most suggested approaches to these patients in the biomedical literature.5,6,13 Imaging (radiograph, CT, MRI, or PET scan) may be indicated to evaluate for the possibility of a skin metastasis from a non–cutaneous carcinoma (e.g., small cell carcinoma of the lung), especially in cases where CK-20 is negative. One diagnostic test to consider is a radiolabeled scan using a somatostatin analogue.5,6

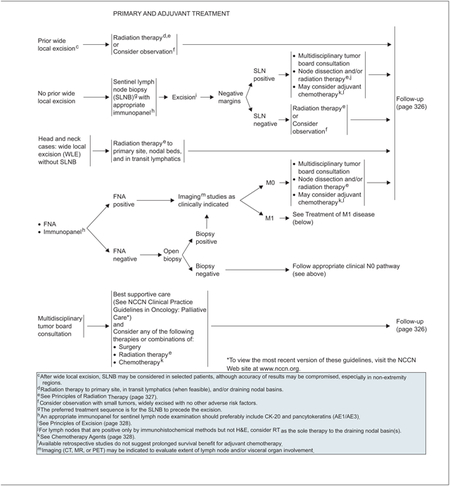

Treatment primarily depends on accurate histopathologic interpretation and microstaging of the primary lesion. Thus, excisional biopsy of the entire lesion with narrow clear surgical margins is preferred, whenever possible, to obtain the most accurate diagnostic and microstaging information. Then, definitive excision with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) can best be performed. IHC analysis has been shown to be effective in detecting more lymph node metastases in patients with MCC.3,26 CK-20 immunostaining in the pathologic assessment of sentinel lymph nodes removed from patients is a valuable diagnostic adjunct, because it allows accurate identification of micrometastases.27,28 An appropriate immunopanel for SLNB should include CK-20 and pancytokeratins. Performing a wide local excision initially, especially in the head, neck, and trunk regions, may potentially interfere with the accuracy of subsequent SLNB.

Staging

In biomedical literature, the most consistently reported adverse prognostic feature is tumor stage followed by tumor size.1,2,6,8,10,11,13,14,16 NCCN staging of MCC parallels the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines and divides presentation into local, regional, and disseminated disease.29 An MCC Web site from Seattle Cancer Care Alliance also has a useful staging table (www.merkelcell.org).

Treatment

Surgery is the primary treatment modality for MCC. The use of the following treatment options varies tremendously among individual clinicians and NCCN institutions:

SLNB or elective lymph node dissection for clinically normal regional lymph node basin(s)

Postoperative radiation therapy for the primary tumor, draining lymphatics, and/or regional lymph node basins

Adjuvant chemotherapy for local or regional disease

Therefore, the MCC guidelines are suitably broad to reflect all the approaches taken by participating NCCN institutions.

Excision

Local wide excision is the recommended primary treatment for clinically localized (N0) disease (see page 328). Because of the high historic risk for local recurrence in MCC, the panel’s tenets for surgical excision emphasize complete extirpation of tumor at initial resection to achieve clear surgical margins when clinically feasible. Surgical techniques include excision with wide margins to the investing fascia layer with complete peripheral margin examination, and Mohs or modified Mohs surgery.30 Mohs micrographic surgery is superior to conventional surgical excision in basal and squamous cell carcinoma. In MCC, it is primarily used to ensure complete tumor removal and clear margins, while secondarily sparing surrounding healthy tissue.31

SLNB

SLNB is important in the staging and treatment of MCC.32 Studies suggest that elective lymph node dissection decreases regional recurrence rates and improves survival.2,8 Most studies examining the use of SLNB in MCC suggest a positive benefit but have only short-term follow-up.33–36 One review found that pathologic nodal staging was associated with improved survival and decreased nodal recurrence. Evidence suggests the incidence of a positive sentinel lymph node is independent of primary tumor size.19 Essentially all participating NCCN institutions use the SLNB technique routinely for MCC, as they do for melanoma. SLNB is offered for staging purposes to patients who are otherwise healthy; a positive sentinel lymph node is followed up with a completion lymph node dissection and/or radiation therapy if appropriate. The panel believes that identifying patients with positive microscopic nodal disease and then performing full lymph node dissections can maximize the care of regional disease in these patients. Finally, as with melanoma, SLNB is best performed before definitive local excision.

Radiation Therapy

Although reports on the benefits of radiation therapy have been mixed, recent studies provide increasing support for using postoperative radiation in MCC to minimize locoregional recurrence. According to a meta-analysis comparing surgery alone with surgery plus adjuvant radiation, local adjuvant radiation after complete excision lowered the risk for local and regional recurrences.37 In a review of 82 cases diagnosed between 1992 and 2004, administering radiotherapy to the primary site or regional lymph nodes was associated with a prolonged time to recurrence and survival.38 The panel included radiation as a treatment option for all stages of MCC. Specifications on radiation dosing for different MCC sites (head and neck vs. extremity and torso) are detailed on page 327.

Chemotherapy

Most NCCN institutions only use chemotherapy with or without surgery and/or radiation therapy for stage IV distant metastatic disease (M1). A few member institutions suggest considering adjuvant chemotherapy for selected cases of regional (N+) disease. Available data from retrospective studies do not suggest prolonged survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy.39,40 Data are insufficient to assess whether chemotherapeutic regimens improve either relapse-free or overall survival in patients with MCC who have distant metastatic disease.41–44 If it is used, the panel recommends etoposide in combination with cisplatin or carboplatin, or cyclophosphamide in combination with doxorubicin and vincristine (see page 328). Topotecan has also been used in some instances (e.g., older patients).

Metastatic Disease

The panel recommends multidisciplinary tumor board consultation for patients with metastatic disease to consider any or a combination of radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy (see page 325). Full imaging workups are recommended for all patients with clinically proven regional or metastatic disease. In general, the care of patients with distant metastasis must be individualized.

Follow-up

Finally, the panel’s recommendations for close clinical follow-up of patients immediately after diagnosis and treatment of MCC (see page 326) parallel the recommendations in the biomedical literature. The schedule is the same regardless of whether patients are N0, N+, or clinical M1. The physical examination should include a complete skin and regional lymph node examination every 1 to 3 months for the first year, every 3 to 6 months in the second year, and annually thereafter. The panel’s recommendations also reflect the fact that the median time to recurrence in patients with MCC is approximately 8 months, with 90% of the recurrences occurring within 24 months.3,10,19 Self-examination of the skin is useful for patients with MCC because they are likely at greater risk for other non-melanoma skin cancers.

Principles of Radiation Therapy

| Dose Recommendations for Radiation Therapy: | |

|---|---|

| Primary site: | |

| • Negative resection margins | 50–56 Gy |

| • Microscopic (+) resection margins | 56–60 Gy |

| • Gross (+) resection margins or unresectable | 60–66 Gy |

| Nodal bed: | |

| • No SLNB or LN dissection | |

| • Clinically (−) but at risk for subclinical disease | 46–50 Gy |

| • Clinically evident adenopathy: head and neck | 60–66 Gy |

| • Clinically evident adenopathy: axilla or groin1 | --1 |

| • After SLNB without LN dissection | |

| • Negative SLNB: axilla or groin | Radiation not indicated2 |

| • Negative SLNB: head and neck, if at risk for false-negative biopsy | 46–50 Gy2 |

| • Microscopic N+ on SLNB: axilla or groin | 50 Gy3 |

| • Microscopic N+ on SLNB: head and neck | 50–56 Gy |

| • After LN dissection | |

| • Lymph node dissection: axilla or groin | 50–54 Gy4 |

| • Lymph node dissection: head and neck | 50–60 Gy |

| |

Lymph node dissection is the recommended initial therapy for clinically evident adenopathy in the axilla or groin, followed by postoperative radiation if indicated.

Consider RT when there is a potential for anatomic (e.g., previous history of surgery including WLE), operator, or histologic failure (e.g., failure to perform appropriate immunohistochemistry on SLNs) that may lead to a false-negative SLNB.

Microscopic N+ is defined as single-node involvement that is neither palpable clinically nor abnormal by imaging criteria, which microscopically consists of small metastatic foci without extracapsular extension.

RT may be omitted after axillary/groin LN dissection for microscopic disease. Postoperative radiation is indicated for multiple involved nodes and/or presence of more than focal extracapsular extension.

PRINCIPLES OF EXCISION

Goal:

|

Varied Approaches:

|

Reconstruction:

|

Mohs technique is used primarily in MCC to insure complete removal and clear margins, and secondarily for its tissue-sparing capabilities.

CHEMOTHERAPY AGENTS2

Local disease:

|

Regional disease:

|

Disseminated disease:

|

When available and clinically appropriate, enrollment in a clinical trial is recommended. The literature is not directive regarding the specific chemotherapeutic agent(s) offering superior outcomes, but the literature does provide evidence that Merkel cell carcinoma is chemosensitive, although the responses are not durable, and the agents listed above have been used with some success.

Individual Disclosures for the NCCN Merkel Cell Carcinoma Panel

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support | Advisory Boards, Speakers Bureau, Expert Witness, or Consultant | Patent, Equity, or Royalty | Other | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murad Alam, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/15/08 |

| James Andersen, MD | None | None | None | None | 7/25/08 |

| Daniel Berg, MD | None | None | None | None | 11/7/08 |

| Christopher K. Bichakjian, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/9/08 |

| Glen Bowen, MD | None | None | None | None | 11/7/08 |

| Richard T. Cheney, MD | None | None | None | None | 11/21/08 |

| L. Frank Glass, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/15/08 |

| Roy C. Grekin, MD | Genentech, Inc.; and DUSA | None | None | None | 9/10/08 |

| Dennis E. Hallahan, MD | Genentech, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Pfizer Inc. | Cumberland Pharmaceuticals | Cumberland Pharmaceuticals; and Genvec | None | 11/21/08 |

| Anne Kessinger, MD | Pharmacyclics; and sanofi-aventis U.S. | None | None | None | 12/15/08 |

| Nancy Y Lee, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/15/08 |

| Nanette Liegeois, MD, PhD | None | None | None | None | 12/15/08 |

| Daniel D. Lydiatt, DDS, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/22/08 |

| Jeff Michalski, MD, MBA | None | None | None | None | 7/23/08 |

| Stanley J. Miller, MD | None | None | None | None | 11/21/08 |

| William H Morrison, MD | None | None | None | Merck & Co., Inc.; Schering-Plough Corporation; and Varian Medical Systems, Inc. | 9/8/08 |

| Kishwer S. Nehal, MD | None | None | None | None | 7/26/08 |

| Kelly C. Nelson, MD | None | None | None | None | 9/5/08 |

| Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD | None | None | None | None | 6/20/08 |

| Thomas Olencki, DO | Amgen Inc.; and Schering-Plough Corporation | None | None | None | 6/11/08 |

| Clifford S. Perlis, MD, MBe | Lucid, Inc. | Lucid, Inc. | Lucid, Inc. | Lucid, Inc. | 11/17/08 |

| E. William Rosenberg, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/15/08 |

| Ashok R. Shaha, MD, FACS | None | None | None | None | 12/3/08 |

| Marshall M. Urist, MD | None | None | None | None | 7/23/08 |

| Linda C. Wang, MD, JD | None | None | None | None | 7/28/08 |

The NCCN guidelines staff have no conflicts to disclose.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: The recommendation is based on high-level evidence (e.g., randomized controlled trials) and there is uniform NCCN consensus.

Category 2A: The recommendation is based on lower-level evidence and there is uniform NCCN consensus.

Category 2B: The recommendation is based on lower-level evidence and there is nonuniform NCCN consensus (but no major disagreement).

Category 3: The recommendation is based on any level of evidence but reflects major disagreement.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: The NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Please Note

These guidelines are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult these guidelines is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way.

These guidelines are copyrighted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. All rights reserved. These guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the NCCN © 2009.

Disclosures for the NCCN Merkel Cell Carcinoma Guidelines Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN guidelines panel meeting, panel members disclosed any financial support they have received from industry. Through 2008, this information was published in an aggregate statement in JNCCN and on-line. Furthering NCCN’s commitment to public transparency, this disclosure process has now been expanded by listing all potential conflicts of interest respective to each individual expert panel member.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Merkel Cell Carcinoma Guidelines Panel members can be found on page 332. (To view the most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures, visit the NCCN Web site at www.nccn.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, please visit www.nccn.org.

NCCN Merkel Cell Carcinoma Panel Members

*Stanley J. Miller, MD/Chairϖ¶ζ

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

Murad Alam, MDϖ¶ζ

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

James Andersen, MD¶

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

Daniel Berg, MDϖ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

Christopher K. Bichakjian, MDϖ

University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center

Glen Bowen, MDϖ

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

Richard T. Cheney, MD≠

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

L. Frank Glass, MDϖ≠

H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute

Roy C. Grekin, MDϖ¶

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

Dennis E. Hallahan, MD§

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

Anne Kessinger, MD†

UNMC Eppley Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

Nancy Y. Lee, MD§

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Nanette Liegeois, MD, PhDϖ¶ζ

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

Daniel D. Lydiatt, DDS, MD¶

UNMC Eppley Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

Jeff Michalski, MD, MBA§

Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

William H. Morrison, MD§

The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center

Kishwer S. Nehal, MDϖ¶

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Kelly C. Nelson, MD≠

Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center

Paul Nghiem, MD, PhDϖ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

Thomas Olencki, DO‡

Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital & Richard J. Solove Research Institute at The Ohio State University

Allan R. Oseroff, MD, PhDϖ

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

Clifford S. Perlis, MD, MBeϖ¶

Fox Chase Cancer Center

E. William Rosenberg, MDϖ

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/University of Tennessee Cancer Institute

Ashok R. Shaha, MD¶

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Marshall M. Urist, MD¶

University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center

Linda C. Wang, MD, JDϖ

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Specialties: ϖDermatology; ¶Surgery/Surgical Oncology; ζOtolaryngology; ≠Pathology/Dermatopathology; §Radiotherapy/Radiation Oncology; †Medical Oncology; ‡Hematology/Hematology Oncology

References

- 1.Akhtar S, Oza KK, Wright J. Merkel cell carcinoma: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen PJ, Zhang ZF, Coit DG. Surgical management of Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Surg 1999;229:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer 2007;110:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goessling W, McKee PH, Mayer RJ. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:588–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruber SB, Wilson LD. Merkel cell carcinoma. In: Cutaneous Oncology: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Malden (MA):Blackwell Science; 1998:710–721. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haag ML, Glass LF, Fenske NA. Merkel cell carcinoma. Diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Surg 1995;21:669–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hitchcock CL, Bland KI, Laney RG III, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin. Its natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Surg 1988;207:201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokoska ER, Kokoska MS, Collins BT, et al. Early aggressive treatment for Merkel cell carcinoma improves outcome. Am J Surg 1997;174:688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawenda BD, Thiringer JK, Foss RD, Johnstone PA. Merkel cell carcinoma arising in the head and neck: optimizing therapy. Am J Clin Oncol 2001;24:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ott MJ, Tanabe KK, Gadd MA, et al. Multimodality management of Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Surg 1999;134:388–392; discussion 392–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitale M, Sessions RB, Husain S. An analysis of prognostic factors in cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma. Laryngoscope 1992;102:244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulsen M Merkel-cell carcinoma of the skin. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, Johnson TM. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;29:143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skelton HG, Smith KJ, Hitchcock CL, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of clinical, histologic, and immunohistologic features of 132 cases with relation to survival. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong KC, Zuletta F, Clarke SJ, Kennedy PJ. Clinical management and treatment outcomes of Merkel cell carcinoma. Aust N Z J Surg 1998;68:354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, et al. Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 2001;8:204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillenwater AM, Hessel AC, Morrison WH, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: effect of surgical excision and radiation on recurrence and survival. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nghiem P, McKee P, Haynes HA. Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds. Skin Cancer. Hamilton (Ontario): BC Decker Inc.; 2001:127–141. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2300–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:832–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller SJ, Alam M, Andersen J, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:704–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheuk W, Kwan MY, Suster S, Chan JK. Immunostaining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and cytokeratin 20 aids the distinction of small cell carcinoma from Merkel cell carcinoma, but not pulmonary from extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001;125:228–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanly AJ, Elgart GW, Jorda M, et al. Analysis of thyroid transcription factor-1 and cytokeratin 20 separates merkel cell carcinoma from small cell carcinoma of lung. J Cutan Pathol 2000;27:118–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott MP, Helm KF. Cytokeratin 20: a marker for diagnosing Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol 1999;21:16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feinmesser M, Halpern M, Kaganovsky E, et al. C-KIT Expression in primary and metastatic merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol 2004;26:458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen P, Busam K, Hill AD, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of sentinel lymph nodes from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 2001;92:1650–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmalbach CE, Lowe L, Teknos TN, et al. Reliability of sentinel lymph node biopsy for regional staging of head and neck Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;131:610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su LD, Lowe L, Bradford CR, et al. Immunostaining for cytokeratin 20 improves detection of micrometastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in sentinel lymph nodes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. AJCC Springer-Verlag: New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor WJ, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Merkel cell carcinoma. Comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision in eighty-six patients. Dermatol Surg 1997;23:929–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennington BE, Leffell DJ. Mohs micrographic surgery: established uses and emerging trends. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:1165–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta SG, Wang LC, Penas PF, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: the Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:685–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ames SE, Krag DN, Brady MS. Radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in Merkel cell carcinoma: a clinical analysis of seven cases. J Surg Oncol 1998;67:251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill AD, Brady MS, Coit DG. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy for Merkel cell carcinoma. Br J Surg 1999;86:518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehrany K, Otley CC, Weenig RH, et al. A meta-analysis of the prognostic significance of sentinel lymph node status in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:113–117; discussion 117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Messina JL, Reintgen DS, Cruse CW, et al. Selective lymphadenectomy in patients with Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 1997;4:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, Otley CC. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jabbour J, Cumming R, Scolyer RA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: assessing the effect of wide local excision, lymph node dissection, and radiotherapy on recurrence and survival in early-stage disease—results from a review of 82 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1992 and 2004. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:1943–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garneski KM, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma adjuvant therapy: current data support radiation but not chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tai P Merkel cell cancer: update on biology and treatment. Curr Opin Oncol 2008;20:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4371–4376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I, et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;64:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tai PT, Yu E, Winquist E, et al. Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine/Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: case series and review of 204 cases. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2493–2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voog E, Biron P, Martin JP, Blay JY. Chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 1999;85:2589–2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]