Abstract

Background:

Incidence rates of gastric cancer are increasing in young adults (age <50 years), particularly among Hispanic persons. We estimated incidence rates of early-onset gastric cancer (EOGC) among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White persons by census tract poverty level and county-level metro/non-metro residence.

Methods:

We used population-based data from the California and Texas Cancer Registries from 1995–2016 to estimate age-adjusted incidence rates of EOGC among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White persons by year, sex, tumor stage, census tract poverty level, metro vs. non-metro county, and state. We used logistic regression models to identify factors associated with distant stage diagnosis.

Results:

Of 3047 persons diagnosed with EOGC, 73.2% were Hispanic White. Incidence rates were 1.29 (95% CI 1.24, 1.35) and 0.31 (95% CI 0.29, 0.33) per 100,000 Hispanic White and non-Hispanic White persons, respectively, with consistently higher incidence rates among Hispanic persons at all levels of poverty. There was no statistically significant associations between ethnicity and distant stage diagnosis in adjusted analysis.

Conclusion:

There are ethnic disparities in EOGC incidence rates that persist across poverty levels.

Impact:

EOGC incidence rates vary by ethnicity and poverty; these factors should be considered when assessing disease risk and targeting prevention efforts.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the 5th most common cancer and 4th leading cause of cancer related deaths worldwide.(1) Recently, incidence rates of non-cardia gastric cancer have increased in younger (age < 50 years) adults.(2–8) Early-onset non-cardia gastric cancer (EOGC) is clinically and morphologically distinct from non-cardia gastric cancer in older adults.(4,6–9) Young adults diagnosed with gastric cancer are more likely to have tumors with signet-ring cell or diffuse histology, present with metastatic disease, and have germline mutations in CDH1 compared to older adults.(4,6–12)

EOGC occurs more frequently in Hispanic White persons and two in every five persons diagnosed with EOGC are Hispanic. Notably, Hispanic persons account for almost 40% of the population in both California and Texas.(8,10,13–15) Incidence rates, risk factors, and anatomic location of gastric cancer have historically differed by ethnicity.(3,16) For example, non-Hispanic White persons typically have cancer in the cardia, related to gastroesophageal reflux, whereas Hispanic White persons more often have non-cardia gastric cancers related to Helicobacter pylori (H. Pylori) infection.(3,14,16) However, few studies have evaluated whether these differences persist in those with EOGC.

Social determinants of health (SDOH), including socioeconomic status and residential neighborhood poverty, are also increasingly recognized as important factors that may play a role in cancer incidence and outcomes.(15,17,18) Among Hispanic persons, lower neighborhood socioeconomic status is associated with increased risk of non-cardia cancers, but not cardia cancers.(16) The young Hispanic population is growing in the U.S.(19), and Hispanics are more likely than non-Hispanic White persons to live in neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status.(20) Despite the alarming trend of EOGC in this population, and the impact that SDOH may have on disparities in cancer incidence, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies examining the relationship between SDOH and EOGC among Hispanic persons.

To address these gaps, we aimed to: 1) estimate incidence rates of EOGC by ethnicity, census tract poverty level, and county-level metro/non-metro residence; and 2) examine the association between ethnicity, SDOH, and tumor stage. We used population-based data from the Texas Cancer Registry and California Cancer Registry, together representing 45% of the U.S. Hispanic population.(13,21) We hypothesized that incidence rates of EOGC are higher in Hispanic White compared to non-Hispanic White persons, and that the changing landscape of EOGC is associated with SDOHs, such as neighborhood poverty.

Methods

Study Population

We used population-based data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR) and Texas Cancer Registry (TCR), two of the largest cancer registries in the U.S, to derive incident cases of EOGC during 1995 – 2016. Both registries collect demographic and clinical information of cancers diagnosed in their respective states and in accordance with the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries Gold Certification standards (NAACR).(22) Persons were included if they were identified as Hispanic White (hereafter, “Hispanic”) or non-Hispanic White (hereafter, “White”) based on the NAACR Hispanic Identification Algorithm (NHIA) and race variable. Persons were included if they had a non-cardia gastric cancer and an International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3) histology code for adenocarcinoma, linitis, intestinal, diffuse, signet, as well as those missing histology information (Figure 1).(16)

Figure 1:

Eligible Patients in the Texas and California Cancer Registry

Covariates

We included the following covariates in our analysis: stage at diagnosis, metro vs. non-metro county, census tract poverty level, histology, grade, and insurance type. Stage at diagnosis was based on the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) summary stage, defined as in situ/local, regional, and distant. Metro vs. non-metro county was defined using Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), a classification scheme distinguishing counties by population size, commuting flow, and proximity to metro areas.(23–25) Census tract poverty level was defined using the proportion of the population living below the federal poverty line as low (0-<10%), middle (10%–19%), and high poverty (≥ 20%). Tumor grade was defined as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, undifferentiated, or unknown. Insurance status was defined as uninsured, private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, or other insurance, which includes Tricare/VA, Indian/public health, insurance NOS, unknown, and county insurance (CCR only). Insurance status at the time of diagnosis was collected in TCR after 2006 and in CCR starting in 1988.

Incidence Rates of Early-onset Gastric Cancer

For both Hispanic and White persons, we estimated age-adjusted (to the 2000 US standard population) incidence rates of EOGC as rates per 100,000 persons. Corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as modified gamma intervals using the Tiwari method.(26) We compared incidence rates between Hispanic and White persons, overall and by 10-year age group, year of diagnosis (1995 – 2005 vs. 2006 – 2016), sex, stage at diagnosis, census tract poverty level, metro vs. non-metro county, and state (California vs. Texas).

Incidence rates per 100,000 persons were calculated as the number of new cancer cases divided by the size of the population. Currently, cancer registries do not provide population denominators by poverty level; therefore, in order to calculate the incidence rate of EOGC by census tract poverty level, we generated population denominators in a multi-step process. First, for each individual, we defined poverty at the time of the EOGC diagnosis defined at the census tract level as low, middle, or high. The Texas Cancer Registry provided poverty data for all individuals; for California, we obtained the equivalent data from the U.S. Census and merged those data to the California Cancer Registry. Census tracts are relatively homogenous small areas with respect to population characteristics and economic status, with an average size of 4,000 residents. Next, for each year, we calculated annual, poverty-relevant tract-level denominators using SEER county-level population denominator data and Census data on the number of census tract residents (for each county) living below the federal poverty line. The census data used include the 2000 Decennial US Census and American Community Survey data (1995–2016). Denominators were calculated by multiplying the total population living in a county (SEER denominator data) by the ratio of the number of people living in low/middle/high poverty tracts to the total denominator for whom poverty data were available (Census data). This process ensured that the denominators used to calculate incidence rate for census tract poverty were comparable to those created by SEER and used to calculate incidence rate by other characteristics. All population-level poverty data were stratified by age (5-year increments), sex, ethnicity, and year.

To illustrate changes in incidence rates over time, we plotted age-adjusted incidence rates by ethnicity and census tract poverty level, county type, and stage at diagnosis in two different time periods (1995 – 2005 and 2006 – 2016) between Hispanic and Whites persons. A cut-off of 2005 was selected a priori to create two equal 10-year time periods.

We also conducted a joinpoint analysis to estimate annual percent change (APC) in incidence rates by ethnicity, census tract poverty level, and county-level metro/non-metro residence. The joinpoint model uses permutation analysis to fit a series of joined straight lines on a logarithmic scale to observed rates, whereby the slope of the line segment between joinpoints is equivalent to the APC. Two-sided p-values <.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance, whereby the APC is significantly different from 0.

Factors Associated with Distant Stage at Diagnosis

We used logistic regression models to estimate associations of stage at diagnosis (distant stage vs. in-situ/local or regional stage) and ethnicity, age at diagnosis, county type, state, and census tract poverty level. We report crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs; the adjusted model included sex, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, and tumor histology.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics between Hispanic and White persons were compared using Pearson Chi-Square test for categorical variables. We used SEER*Prep Version 2.6.0 to prepare data for use in SEER*Stat Version 8.3.9.2 (Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD). We used STATA Version 15.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) to calculate incidence rates and fit regression models. We used SAS (Cary, NC) to prepare the poverty level denominators.

Data Availability

Cancer data have been provided by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services, 1100 West 49th Street, Austin, TX 78756 (www.dshs.texas.gov/tcr) and the California Cancer Registry, California Department of Public Health (https://www.ccrcal.org/learn-about-ccr/).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

We identified 1,985 and 1,062 Hispanic and White persons diagnosed with EOGC in California and Texas, respectively, during 1995 – 2016 (Figure 1). Most persons diagnosed with EOGC were Hispanic (73.2%), with several notable differences in characteristics by ethnicity (Table 1). For example, a higher proportion of Hispanic persons were uninsured (17.5% vs. 2.8%) or had Medicaid (31.2% vs. 14.8%) and lived in high poverty neighborhoods (46.4% vs. 15.4%) or metro countries (94.7% vs. 92.0%) compared to White persons (Table 1). Hispanic persons were also more likely to have signet ring cell histology (44.4 % vs. 40.5%) and poorly differentiated grade (76.5 % vs. 66.7 %) than White persons (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of 3047 Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites diagnosed with early-onset gastric cancer by ethnicity, Texas Cancer Registry and California Cancer Registry, 1995 – 2016

| Hispanic White n=2,233 | Non-Hispanic White n=814 | p-value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (percent) | |||

| Sex | 0.44 | ||

| Male | 1,173 (52.5) | 444 (54.6) | |

| Female | 1,058 (47.4) | 370 (45.5) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Age at Diagnosis | <0.01 | ||

| 20–29 | 162 (7.3) | 22 (2.7) | |

| 30–39 | 682 (30.5) | 187 (23.0) | |

| 40–49 | 1389 (62.2) | 605 (74.3) | |

| State | 0.01 | ||

| Texas | 749 (33.5) | 313 (38.5) | |

| California | 1,484 (66.5) | 501 (61.6) | |

| Years of Diagnosis | <0.01 | ||

| 1995–2005 | 938 (42.0) | 424 (52.1) | |

| 2006–2016 | 1295 (58.0) | 390 (47.9) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 | 974 (43.6) | 416 (51.1) | <0.01 |

| 1–2 | 295 (13.2) | 119 (14.6) | |

| >=3 | 53 (2.4) | 21 (2.6) | |

| Missing | 911 (40.8) | 258 (31.7) | |

| Histology | <0.01 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 718 (32.2) | 302 (37.1) | |

| Linitis | 33 (1.5) | 14 (1.7) | |

| Intestinal | 77 (3.5) | 33 (4.1) | |

| Diffuse | 188 (8.4) | 41 (5.0) | |

| Signet | 992 (44.4) | 330 (40.5) | |

| Missing | 225 (10.1%) | 94 (11.6) | |

| Grade | <0.01 | ||

| Well Differentiated | 30 (1.3) | 25 (3.1) | |

| Moderately Differentiated | 140 (6.3) | 87 (10.6) | |

| Poorly Differentiated | 1,709 (76.5) | 545 (66.7) | |

| Undifferentiated | 55 (2.4) | 19 (2.3) | |

| Missing | 299 (13.4) | 138 (17.0) | |

| Stage | 0.01 | ||

| In Situ/Local | 281 (12.6) | 136 (16.7) | |

| Regional | 754 (33.8) | 277 (34.0) | |

| Distant | 1,108 (49.6) | 355 (43.6) | |

| Missing | 90 (4.0) | 46 (5.7) | |

| Received Chemo | 1,360 (60.9) | 463 (56.9) | 0.05 |

| Received Surgery | 1058 (47.4) | 444 (54.6) | 0.01 |

| Insurance* | <0.01 | ||

| Uninsured | 209 (17.5) | 10 (2.8) | |

| Private | 443 (37.1) | 220 (60.4) | |

| Medicaid | 372 (31.2) | 54 (14.8) | |

| Medicare | 28 (2.4) | 18 (5.0) | |

| Other** | 141 (11.8) | 62 (4.0) | |

| Census tract poverty level | <0.01 | ||

| 0–<10% | 486 (21.8) | 426 (52.3) | |

| 10–19% | 712 (31.9) | 262 (32.2) | |

| ≥20% | 1035 (46.4) | 125 (15.4) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.1) | |

| County type | <0.01 | ||

| Metro | 2115 (94.7%) | 749 (92.0%) | |

| Non-Metro | 118 (5.3%) | 65 (8.0%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Insurance collected from year 2007 and on (n=1557)

Other includes Tricare/VA, Indian/public health, insurance NOS, unknown, and county.

p-values obtained using Pearson chi-square test

Characteristics by State

We identified 749 Hispanic and 313 White persons with EOGC in Texas from 1995–2016. The majority of EOGC was diagnosed among the 40- to 49-year age group (Table 2). A greater proportion of Hispanic persons were uninsured (33.7% vs. 6.1%, p<0.01), lived in a high poverty census tract (52.9 vs. 14.7%, p<0.01), and diagnosed with distant disease (44.3% vs. 36.4%, p<0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Characteristics of Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites diagnosed with early-onset gastric cancer by ethnicity and state, Texas Cancer Registry and California Cancer Registry, 1995–2016

| Texas Hispanic White n=749 | Texas Non-Hispanic White n=313 | California Hispanic White n=1484 | California Non-Hispanic White n=501 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (percent) | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 387 (51.7) | 166 (53.0) | 786 (53.0) | 278 (55.5) |

| Female | 362 (48.3) | 147 (47.0) | 696 (46.9) | 223 (44.5) |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Age at Diagnosis+# | ||||

| 20–29 | 59 (7.9) | 8 (2.6) | 103 (6.9) | 14 (2.8) |

| 30–39 | 215 (28.7) | 68 (21.7) | 467 (31.5) | 119 (23.8) |

| 40–49 | 475 (63.4) | 237 (75.7) | 914 (61.6) | 368 (73.5) |

| Years of Diagnosis+# | ||||

| 1995–2005 | 321 (42.9) | 154 (49.2) | 617 (41.6) | 270 (53.9) |

| 2006–2016 | 428 (57.1) | 159 (50.8) | 867 (58.4) | 231 (46.1) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index# | ||||

| 0 | 179 (23.9) | 75 (24.0) | 795 (53.6) | 341 (86.1) |

| 1–2 | 43 (5.7) | 13 (4.2) | 252 (17.0) | 106 (21.2) |

| >=3 | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 49 (3.3) | 21 (4.2) |

| Missing | 523 (69.8) | 225 (71.9) | 388 (26.2) | 33 (6.6) |

| Histology# | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 296 (39.5) | 123 (39.3) | 422 (28.4) | 179 (35.7) |

| Linitis | 5 (0.7) | 4 (1.3) | 28 (1.9) | 10 (2.0) |

| Intestinal | 16 (2.1) | 12 (3.8) | 61 (4.1) | 21 (4.2) |

| Diffuse | 36 (4.8) | 16 (5.1) | 152 (10.2) | 25 (5.0) |

| Signet | 321 (42.9) | 121 (38.7) | 671 (45.2) | 209 (41.7) |

| Missing | 75 (10.0) | 37 (11.8) | 150 (10.1) | 57 (11.4) |

| Grade+# | ||||

| Well Differentiated | 14 (1.9) | 5 (1.6) | 16 (1.1) | 20 (4.0) |

| Moderately Differentiated | 61 (8.1) | 39 (12.5) | 79 (5.3) | 48 (9.6) |

| Poorly Differentiated | 546 (72.9) | 191 (61.0) | 1163 (78.4) | 354 (70.7) |

| Undifferentiated | 14 (1.9) | 10 (3.2) | 41 (2.8) | 9 (1.8) |

| Missing | 114 (15.2) | 68 (21.7) | 185 (12.5) | 70 (14.0) |

| Stage+ | ||||

| In Situ/Local | 103 (13.8) | 59 (18.9) | 178 (12.0) | 77 (15.4) |

| Regional | 270 (36.1) | 110 (35.1) | 484 (32.6) | 167 (33.3) |

| Distant | 332 (44.3) | 114 (36.4) | 776 (52.3) | 241 (48.1) |

| Missing | 44 (5.9) | 30 (9.6) | 46 (3.1) | 16 (3.2) |

| Received Chemo+ | 410 (54.7) | 148 (47.3) | 950 (64.0) | 315 (32.9) |

| Received Surgery+# | 325 (43.4) | 149 (47.6) | 733 (49.4) | 295 (58.9) |

| Insurance*+# | ||||

| Uninsured | 130 (33.7) | 9 (6.1) | 141 (9.5) | 10 (2.0) |

| Private | 124 (32.1) | 87 (58.8) | 577 (38.9) | 294 (58.7) |

| Medicaid | 56 (14.5) | 9 (6.1) | 509 (32.3) | 95 (19.0) |

| Medicare | 14 (3.6) | 10 (6.8) | 33 (2.2) | 22 (4.4) |

| Other** | 62 (16.1) | 33 (22.3) | 224 (15.1) | 80 (16.0) |

| Census tract poverty level+# | ||||

| 0-<10% | 119 (15.9) | 164 (52.4) | 367 (24.7) | 262 (52.3) |

| 10-<20% | 234 (31.2) | 102 (32.6) | 478 (32.2) | 160 (31.9) |

| >=20% | 396 (52.9) | 46 (14.7) | 639 (43.1) | 79 (15.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| County type# | ||||

| Metro | 654 (87.3) | 271 (86.6) | 1461 (98.5) | 478 (95.4) |

| Non-Metro | 95 (12.7) | 42 (13.4) | 23 (1.6) | 23 (4.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Insurance collected starting year 2007 (n=534)

Other includes Tricare/VA, Indian/public health, insurance NOS, unknown, and county.

p-values obtained using Pearson chi-square test are <0.05, Texas Cancer Registry

p-values obtained using Pearson chi-square test are <0.05, California Cancer Registry

We identified 1484 Hispanic and 501 White persons with EOGC in California. Similar to Texas, the majority of EOGC was diagnosed among the 40- to 49-year age group (Table 2). Compared to White persons, a greater proportion of Hispanic persons in California were on Medicaid (32.3% vs. 19.0%, p<0.01), and lived in a high poverty census tract (43.1% vs. 15.8%, p<0.01) (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in stage of disease between Hispanic and White persons. Notably, a smaller proportion of Hispanic persons in California were uninsured as compared to Texas (9.5% vs. 33.7%).

Incidence Rates of Early-onset Gastric Cancer

Overall, incidence rates of EOGC were 1.29 per 100,000 Hispanic persons (95% CI 1.24, 1.35) and 0.31 per 100,000 White persons (95% CI 0.29, 0.33) (Table 3). Incidence rates were consistently higher among Hispanic persons compared to White persons by age, year, sex, stage at diagnosis, county type, census tract poverty level, and state. For example, incidence rates of EOGC within high poverty neighborhoods ( ≥ 20%) were 1.49 per 100,000 Hispanics persons (95% CI 1.40, 1.59) versus 0.40 per 100,000 Whites persons (95% CI 0.34, 0.48) (Table 3). The incidence rate of distant disease was 0.63 per 100,000 Hispanic persons (0.59, 0.67) and 0.14 per 100,000 White persons (95% CI 0.12, 0.15).

Table 3:

Age-adjusted incidence rates of early-onset gastric cancer by ethnicity, Texas Cancer Registry and California Cancer Registry, 1995 – 2016

| Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic White | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate per 100,000 | 95% CI | Rate per 100,000 | 95% CI | ||

| Overall | 1.29 | 1.24, 1.35 | 0.31 | 0.29, 0.33 | |

| Age at diagnosis | |||||

| 20–29 | 0.21 | 0.18, 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.04 | |

| 30–39 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.06 | 0.22 | 0.19, 0.26 | |

| 40–49 | 2.52 | 2.39, 2.66 | 0.63 | 0.58, 0.69 | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 1995 – 2005 | 1.35 | 1.27, 1.44 | 0.31 | 0.28, 0.34 | |

| 2006 – 2016 | 1.34 | 1.27, 1.41 | 0.33 | 0.29, 0.36 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1.34 | 1.27, 1.42 | 0.33 | 0.30, 0.37 | |

| Female | 1.24 | 1.17, 1.32 | 0.29 | 0.26, 0.32 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||

| Local | 0.17 | 0.15, 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.04, 0.06 | |

| Regional | 0.44 | 0.41, 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.09, 0.12 | |

| Distant | 0.63 | 0.59, 0.67 | 0.14 | 0.12, 0.15 | |

| County type | |||||

| Metro | 1.22 | 1.17, 1.28 | 0.28 | 0.26, 0.31 | |

| Non-Metro | 0.07 | 0.06, 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.03 | |

| Census tract poverty level | |||||

| <10% | 1.10 | 1.00, 1.20 | 0.28 | 0.26, 0.31 | |

| 10–19% | 1.36 | 1.26, 1.47 | 0.35 | 0.31, 0.39 | |

| >=20% | 1.49 | 1.40, 1.59 | 0.40 | 0.34, 0.48 | |

| State | |||||

| California | 1.48 | 1.41, 1.56 | 0.33 | 0.30, 0.36 | |

| Texas | 1.14 | 1.05, 1.22 | 0.29 | 0.26, 0.33 | |

We evaluated the change in incidence rates over two time periods: 1995–2005 to 2006–2016 by stage at diagnosis, census tract poverty level, and metro vs. non-metro county. Incidence confidence intervals overlapped for most groups, which suggests a lack of statistical significance. From 1995 – 2005 to 2006 – 2016, incidence rates of EOGC increased in low (<10%) poverty neighborhoods from 1.00 (95%CI 0.87, 1.20) per 100,000 Hispanic persons to 1.20 (95%CI 1.01, 1.30) per 100,000 Hispanic persons (Table 4). For both middle (10–19%) and high (≥ 20%) poverty neighborhoods, incidence rates of EOGC decreased for Hispanic persons (Table 4). Among White persons, incidence rates of EOGC increased for middle (10–19%) poverty neighborhoods but decreased among high (≥ 20%) poverty neighborhoods (Table 4). There were no changes in incidence rates of EOGC among both Hispanic and White persons by county type (Table 4). Incidence rates of distant stage disease increased from 1995 – 2005 to 2006 – 2016 for both Hispanic and White persons. The incidence rate of distant disease from 1995–2005 was 0.60 per 100,00 Hispanic persons (95% CI 0.55, 0.66) and 0.69 per 100,000 Hispanic persons (95% CI 0.64, 0.75) from 2006–2016. In contrast, the incidence rate of distant disease from 1995–2005 was 0.13 per 100,000 White persons (95% CI 0.11, 0.15) and 0.15 per 100,000 White persons (95% CI 0.13, 0.17) from 2006–2016 (Table 4).

Table 4:

Point Estimates and Confidence Intervals for early-onset gastric cancer for 1995–2005 and 2006–2016 among Hispanic White and non-Hispanic White persons

| 1995–2005 | 2006–2016 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Adjusted Incidence Rate | 95% Confidence Interval | Age-Adjusted Incidence Rate | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value* | |

| Low Poverty (<10%) | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.00 | 0.87, 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.00, 1.30 | 0.021 |

| White | 0.26 | 0.23, 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.26, 0.35 | 0.167 |

| Medium Poverty (10–19%) | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.40 | 1.20, 1.60 | 1.30 | 1.20, 1.50 | 0.376 |

| White | 0.34 | 0.28, 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.30, 0.43 | 0.922 |

| High Poverty (≥ 20%) | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.60 | 1.40, 1.70 | 1.40 | 1.30, 1.60 | 0.654 |

| White | 0.47 | 0.36, 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.26, 0.45 | 0.056 |

| Metro County | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.26 | 1.18, 1.35 | 1.28 | 1.21, 1.35 | 0.824 |

| White | 0.28 | 0.26, 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.27, 0.33 | 0.571 |

| Non-Metro County | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.09 | 0.07, 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.05, 0.08 | 0.051 |

| White | 0.02 | 0.02, 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.04 | 0.397 |

| In-Situ Stage | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.15 | 0.12, 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.16, 0.22 | 0.140 |

| White | 0.04 | 0.03, 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06, 0.09 | 0.003 |

| Local/Regional | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.54 | 0.48, 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.37, 0.45 | 0.003 |

| White | 0.13 | 0.11, 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07, 0.10 | 0.007 |

| Distant Stage | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.60 | 0.55, 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.64, 0.75 | 0.029 |

| White | 0.13 | 0.11, 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13, 0.17 | 0.137 |

p-value comparing incidence rates from 1995–2005 to 2006–2016

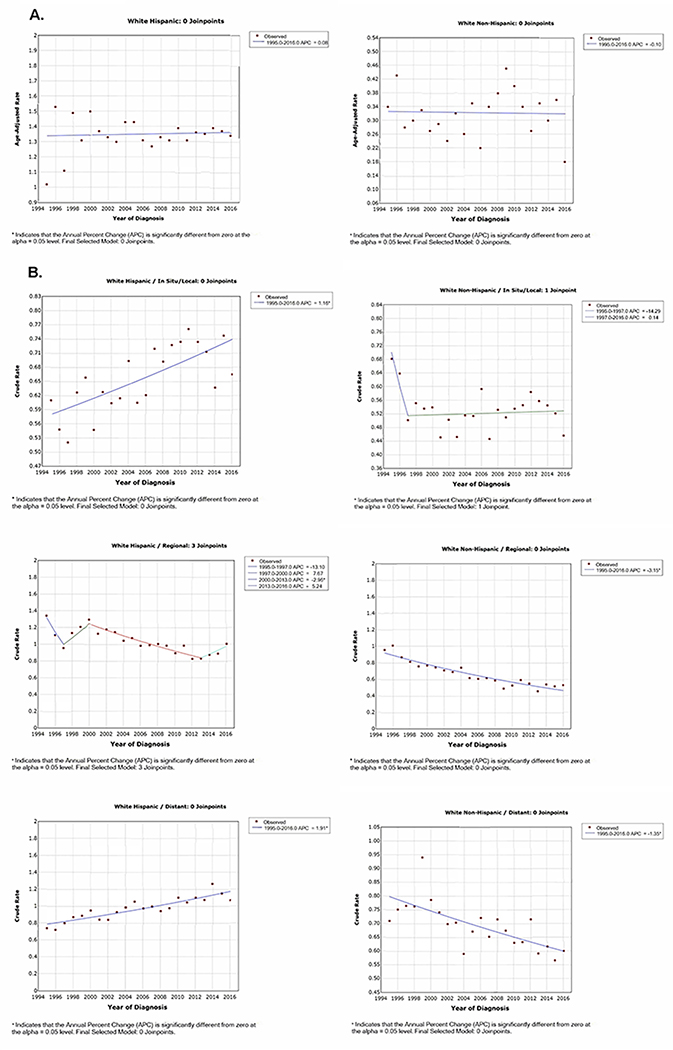

APC was evaluated by ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, census tract poverty level, and metro vs. non-metro county. Although not statistically significant, the APC suggested −0.1 for White persons and 0.08 for Hispanic persons (Figure 2). Among Hispanic persons, distant disease increased by 1.91% per year but decreased by 1.35% per year among White persons (p<0.05, Figure 2). Changes in APC by census tract poverty level and metro vs. non-metro county were similar to our findings over two time periods. For example, the APC for White persons living among high (≥ 20%) poverty neighborhoods decreased by 2.28% per year (p<0.05) and the APC for Hispanic persons living in low (<10%) poverty neighborhoods increase by 2.04% per year (p<0.05).

Figure 2:

Annual Percent Change Among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whites with Early-Onset Gastric Cancer (EOGC)

A. Annual Percent Change of EOGC from 1995–2016 by Ethnicity

B. Annual Percent Change of EOGC from 1995–2016 by Ethnicity and Stage of Disease

Stage at Diagnosis

In unadjusted analyses, a higher proportion of Hispanic persons were diagnosed with distant disease compared to White persons (49.6% vs. 43.6%, p= 0.01) (Table 1). However, in the multivariable logistic regression model, distant stage was associated with living in California (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.47, 95% CI 1.24, 1.75) but not with ethnicity (aOR 1.06, 95% CI 0.87, 1.29) or census tract poverty level (aOR 1.13, 95% CI 0.93–1.39 for middle poverty and aOR 1.06, 95% CI 0.86–1.30 for high poverty) (Table 5).

Table 5:

Crude and adjusted odds ratios assessing association of distant (vs. local or regional) stage at diagnosis by ethnicity, county type, state, and census tract poverty level. Texas Cancer Registry and California Cancer Registry, 1995 – 2016

| Crude (n=3047) | Adjusted (n=2615)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odd Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | ||

| Hispanic White | 1.25 | 1.06, 1.47 | 1.06 | 0.87, 1.29 |

| County type | ||||

| Metro | Ref | Ref | ||

| Non-Metro | 1.11 | 0.82, 1.51 | 1.13 | 0.80, 1.59 |

| State | ||||

| Texas | Ref | Ref | ||

| California | 1.36 | 1.17, 1.59 | 1.47 | 1.24, 1.75 |

| Census tract poverty level | ||||

| 0–<10% | Ref | Ref | ||

| 10–<20% | 1.16 | 0.97, 1.40 | 1.13 | 0.93, 1.39 |

| >=20% | 1.16 | 0.97, 1.40 | 1.06 | 0.86, 1.30 |

The adjusted multivariable model adjusted from sex, histology, age at diagnosis (continuous), and year of diagnosis (continuous) and excluded those with missing data [stage (n=111) histology (n=294), stage & histology (n=24), histology & poverty (n=1), and sex (n=2)].

We conducted a sensitivity of persons diagnosed with EOGC from 2007 to 2016 to estimate the association of payer type and stage of diagnosis. Distant stage remained associated with residence in California (aOR 1.68, 95% CI 1.26, 2.24) and having either no insurance (aOR 2.15, 95% CI 1.48, 3.14) or Medicaid (aOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.42, 2.55) as compared to private insurance. The association between Hispanic ethnicity and tumor stage was unchanged and was not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this population-based study in Texas and California, we observed differences in the burden of EOGC among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White persons. Three out of every four patients diagnosed with EOGC were Hispanic, who were more likely to live in high poverty neighborhoods, metro counties, and be either uninsured or have Medicaid compared to Non-Hispanic White persons with EOGC. Differences in incidence rates between the two groups persisted across multiple domains, including age, year, sex, stage, county type, census tract poverty level, and state.

We observed in bivariate analyses that a higher proportion of Hispanic persons were diagnosed with distant disease and had signet ring cell histology, although our adjusted regression model showed no statistically significant association between ethnicity and stage of disease. Prior population-based gastric cancer studies have demonstrated that signet ring cell carcinoma occurs more commonly in Hispanic persons.(27,28) While signet ring cell carcinoma is not associated with worse survival, it often presents at higher tumor stage than adenocarcinoma.(27,28) Future studies should compare the proportion of signet ring cell histology in Hispanic persons from all-age groups to evaluate whether signet-ring cell carcinoma occurs more commonly in younger Hispanics.

Incidence rates were higher in Hispanic persons compared to Non-Hispanic White persons across all levels of poverty. Higher poverty and lower socioeconomic status among Hispanic persons (of all ages) have been linked to higher incidence rates of certain cancers, including gastric cancer. Specifically, prior studies have found higher overall and histology-specific incidence rates among Hispanic persons who are foreign-born, lower socioeconomic status, and reside in ethnic enclaves.(5,16) These higher incidence rates have been at least partially attributed to the higher prevalence of H.Pylori infection, which increases the risk of developing both diffuse and intestinal-type gastric cancer.(5,29) For example, higher household crowding, lower education level, and lower socioeconomic status, which are common features of Hispanic enclaves in the US, are associated with H.Pylori infection.(5,30,31) Other potential explanations include the increasing incidence of obesity among young Hispanics, which is often associated with lower socioeconomic status.(32,33) Our findings underscore the need to identify drivers of ethnic disparities that persist even within similar-poverty neighborhoods. These drivers may be due to both structural and cultural factors and can be used to develop interventions to prevent EOGC in higher risk communities.(34,35)

We observed geographic disparities in tumor stage. Persons living in California were more likely to be diagnosed with distant stage disease EOGC as compared to Texas, although reasons for this finding are not clear. The composition of ethnic populations in Texas and California are similar, with ~39% of the population of Hispanic ethnicity, and most Hispanic persons are of Mexican origin. While Texans with EOGC are more likely to be uninsured (Texas 25.9% vs. California 7.6%), a higher proportion of patients with EOGC in California are on Medicaid (California 30.4% vs. Texas 12.2%); sensitivity analyses demonstrated both insurance types were associated with distant disease. The association between distant disease and living in California may also be due to an unmeasured confounder, such as nativity. A larger share of the population in California is foreign-born (27%) compared to Texas (17%)(36,37) and tumor etiology or aggressiveness may differ by birthplace. For example, a California study found that foreign-born persons ages 25–39 years had a higher incidence rate of non-cardia gastric cancer as compared to those born in the US.(5) Unfortunately, analyses evaluating nativity are often limited due to high proportions of missing data and misclassification of birthplace in cancer registries.(38) Additionally, there may be differences in degree of urbanicity that we could not capture using county-level RUCC codes, or differences in ethnic enclaves, which could be associated with a higher or lower risk of metastatic EOGC.(22) Future studies should evaluate the role that birthplace, census tract degree of urbanicity, ethnic enclaves, and other environmental or lifestyle factors may play in EOGC incidence and tumor stage.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to combine population-based cancer registry data from California and Texas to examine ethnic disparities in EOGC. The combined data represent nearly 50% of the U.S. Hispanic population. In addition, our study is the first to estimate incidence rates of EOGC by poverty level, and we observed higher incidence rates among Hispanic persons living across all poverty levels. Poverty is consistently associated with worse cancer incidence and mortality for many cancer types.(39,40) However, estimating cancer incidence rates by poverty level at the census tract level can be difficult and labor intensive because cancer registries do not typically provide the denominator data necessary for this calculation to researchers. A strength of our study is not only the incorporation of population denominator data by ethnicity, age, and census tract poverty, but also highlighting the need for this denominator data to be more readily available to researchers interested in SDOH.41

Our study has some limitations that should be noted. First, although we combined cancer registry data from Texas and California, some of our analyses may have been limited by the small number of cases. For example, only 6% of the EOGC population in California and Texas lived in non-metro areas. This likely decreased our ability to detect a difference in incidence rates by non-metro/metro areas. Second, our study did not assess factors such as ethnic enclaves or nativity. Understanding the role of neighborhood enclaves or nativity could potentially clarify some of our findings and inform interventions to improve observed ethnic disparities in EOGC. Third, since most Texans and Californians are of Mexican origin, our results may not be generalizable to other Hispanic populations. For example, 86% of Hispanic persons in Florida are non-Mexican origin, and their risk of EOGC may differ from Hispanic persons in California and Texas.(41) Fourth, we evaluated incidence rates over two time periods (1995–2005 and 2006–2016. However, for most of our covariates of interest, the confidence intervals overlapped among the two time periods. As a result, we cannot definitively conclude that the incidence rates are statistically different in the two time periods except for stage of disease. However, these results are consistent with our APC results and likely is a reflection of the small number of cases. Finally, the extent of missing data differed between the states and this may introduce bias into our analyses. For example, there was more missing stage data in Texas as compared to California, and these differences in missing data may contribute to the lack of an association between stage and ethnicity.

In conclusion, our study found marked ethnic disparities in incidence rates of EOGC, with the highest incidence rates among Hispanic persons, particularly those in metro areas and higher poverty neighborhoods. Future studies are needed to identify risk factors that may be unique to Hispanic populations to guide interventions that can decrease incidence, morbidity, and mortality of this deadly disease.

Acknowledgements

A. Tavakkoli’s effort was supported by the UTSW ACS-IRG (IRG-17-174-13) and Simmons Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA142543; recipient UTSW Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center).

The collection of California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP006344; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201800032I awarded to the University of California, San Francisco, contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201800009I awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the State of California, Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors. Texas cancer data have been provided by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services, 1100 West 49th Street, Austin, TX 78756 (www.dshs.texas.gov/tcr).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

1. Dr. Caitlin C. Murphy discloses consulting fees for Freenome.

2. The remaining authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merchant SJ, Kim J, Choi AH, Sun V, Chao J, Nelson R. A rising trend in the incidence of advanced gastric cancer in young Hispanic men. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2017;20:226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson WF, Camargo MC, Fraumeni JF, Correa P, Rosenberg PS, Rabkin CS. Age-Specific Trends in Incidence of Noncardia Gastric Cancer in US Adults. Jama. 2010;303:1723–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergquist JR, Leiting JL, Habermann EB, Cleary SP, Kendrick ML, Smoot RL, et al. Early-onset gastric cancer is a distinct disease with worrisome trends and oncogenic features. Surgery. 2019;166:547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang ET, Gomez SL, Fish K, Schupp CW, Parsonnet J, DeRouen MC, et al. Gastric cancer incidence among Hispanics in California: patterns by time, nativity, and neighborhood characteristics. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2012;21:709–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holowatyj AN, Ulrich CM, Lewis MA. Racial/Ethnic Patterns of Young-Onset Noncardia Gastric Cancer. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa). 2019;12:771–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nassour I, Mokdad A, Khan M, Mansour JC, Yopp AC, Minter RM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities among young patients with gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:25–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra R, Balachandar N, Wang S, Reznik S, Zeh H, Porembka M. The changing face of gastric cancer: epidemiologic trends and advances in novel therapies. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021;28:390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson WF, Rabkin CS, Turner N, Fraumeni JF, Rosenberg PS, Camargo MC. The Changing Face of Noncardia Gastric Cancer Incidence Among US Non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2018;110:608–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Setia N, Wang CX, Lager A, Maron S, Shroff S, Arndt N, et al. Morphologic and molecular analysis of early-onset gastric cancer. Cancer. 2021;127:103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SY, Park JW, Liu Y, Park YS, Kim JH, Yang H, et al. Sporadic Early-Onset Diffuse Gastric Cancers Have High Frequency of Somatic CDH1 Alterations, but Low Frequency of Somatic RHOA Mutations Compared With Late-Onset Cancers. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:536–549.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Refaie WB, Hu C-Y, Pisters PWT, Chang GJ. Gastric Adenocarcinoma in Young Patients: a Population-Based Appraisal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2800–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Texas, California, and U.S. Hispanic population estimate [Internet]; c2021. [cited 2022 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221.

- 14.Dong E, Duan L, Wu BU. Racial and Ethnic Minorities at Increased Risk for Gastric Cancer in a Regional US Population Study. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2017;15:511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, Wender RC. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2020;70:31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, Tao L, Murphy JD, Camargo MC, Oren E, Valasek MA, et al. Race/Ethnicity-, Socioeconomic Status-, and Anatomic Subsite-Specific Risks for Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:59–62.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Social Determinants of Health: Key Concepts [Internet]; c2013. [ cited 2022 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

- 18.Gomez SL, Shariff-Marco S, DeRouen M, Keegan THM, Yen IH, Mujahid M, et al. The impact of neighborhood social and built environment factors across the cancer continuum: Current research, methodological considerations, and future directions. Cancer. 2015;121:2314–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060, current population reports, P25–1143 [Internet]; c2015. [cited 2022 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- 20.Lichter DT. Immigration and the New Racial Diversity in Rural America*. Rural Sociol. 2012;77:3–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Where the U.S. Hispanic population grew most, least from 2010 to 2019 | Pew Research Center; [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 5]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/10/hispanics-have-accounted-for-more-than-half-of-total-u-s-population-growth-since-2010/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shariff-Marco S, Gomez SL, Canchola AJ, Fullington H, Hughes AE, Zhu H, et al. Nativity, ethnic enclave residence, and breast cancer survival among Latinas: Variations between California and Texas. Cancer. 2020;126:2849–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett KJ, Borders TF, Holmes GM, Kozhimannil KB, Ziller E. What Is Rural? Challenges And Implications Of Definitions That Inadequately Encompass Rural People And Places. Health Affair. 2019;38:1985–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.USDA ERS - Rural-Urban Continuum Codes [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

- 25.Smith ML, Dickerson JB, Wendel ML, Ahn S, Pulczinski JC, Drake KN, et al. The Utility of Rural and Underserved Designations in Geospatial Assessments of Distance Traveled to Healthcare Services: Implications for Public Health Research and Practice. J Environ Public Heal. 2013;2013:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates: Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2016;15:547–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taghavi S, Jayarajan SN, Davey A, Willis AI. Prognostic Significance of Signet Ring Gastric Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3493–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theuer CP, Nastanski F, Brewster WR, Butler JA, Anton-Culver H. Signet ring cell histology is associated with unique clinical features but does not affect gastric cancer survival. Am Surg. 1999;65:915–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polk DB, Peek RM. Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:403–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark WAV, Deurloo MC, Dieleman FM. Housing Consumption and Residential Crowding in U.S. Housing Markets. J Urban Aff. 2000;22:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres J, Leal-Herrera Y, Perez-Perez G, Gomez A, Camorlinga-Ponce M, Cedillo-Rivera R, et al. A Community-Based Seroepidemiologic Study of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Mexico. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1089–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, Freedman DS, Carroll MD, Gu Q, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence by Race and Hispanic Origin—1999–2000 to 2017–2018. Jama. 2020;324:1208–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong MS, Chan KS, Jones-Smith JC, Colantuoni E, Thorpe RJ, Bleich SN. The neighborhood environment and obesity: Understanding variation by race/ethnicity. Prev Med. 2018;111:371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang RJ, Koh H, Hwang JH, Leaders S, Abnet CC, Alarid-Escudero F, et al. A Summary of the 2020 Gastric Cancer Summit at Stanford University. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epplein M, Signorello LB, Zheng W, Peek RM, Michel A, Williams SM, et al. Race, African Ancestry, and Helicobacter pylori Infection in a Low-Income United States Population. Cancer Epidemiology Prev Biomarkers. 2011;20:826–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Research P. PH_2016-Foreign-Born-Statistical-Portraits_Current-Data_45_Nativity-by-state.png (471×1457) [Internet]. Foreign Born Statistical Portrait by State, 2016. [cited 2022 Jan 27]. Available from: https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/09/12103811/PH_2016-Foreign-Born-Statistical-Portraits_Current-Data_45_Nativity-by-state.png [Google Scholar]

- 37.Research P. Statistical Portrait: 2016 Foreign-Born Population in United States | Pew Research Center; [Internet]. Statistical Portrait: 2016 Foreign-Born Population in United States. [cited 2022 Jan 27]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2018/09/14/2016-statistical-information-on-foreign-born-in-united-states/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez SL, Glaser SL. Quality of cancer registry birthplace data for Hispanics living in the United States. Cancer Cause Control. 2005;16:713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss JL, Pinto CN, Srinivasan S, Cronin KA, Croyle RT. Persistent Poverty and Cancer Mortality Rates: An Analysis of County-Level Poverty Designations. Cancer Epidemiology Prev Biomarkers. 2020;29:1949–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegel RL, Ahmedin Jemal, Thun Michael J, Yongping Hao, Ward Elizabeth M. Trends in the Incidence of Colorectal Cancer in Relation to County-Level Poverty among Blacks and Whites. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1441–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Research P. Demographic and Economic Profiles of Hispanics by State and County, 2014. | Pew Research Center; [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/states/state/fl [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Cancer data have been provided by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services, 1100 West 49th Street, Austin, TX 78756 (www.dshs.texas.gov/tcr) and the California Cancer Registry, California Department of Public Health (https://www.ccrcal.org/learn-about-ccr/).