SUMMARY

The first domain of modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) is most commonly a ketosynthase (KS)-like enzyme, KSQ, that primes polyketide synthesis. Unlike downstream KSs that fuse α-carboxyacyl groups to growing polyketide chains, it performs an extension-decoupled decarboxylation of these groups to generate primer units. When Pik127, a model triketide synthase constructed from modules of the pikromycin synthase, was studied by cryo-EM, the dimeric didomain comprised of KSQ and the neighboring methylmalonyl-selective acyltransferase (AT) dominated the class averages and yielded structures at 2.48-Å and 2.77-Å resolution, respectively. Comparisons with ketosynthases complexed with their substrates revealed the conformation of the (2S)-methylmalonyl-S-phosphopantetheinyl portion of KSQ and KS substrates prior to decarboxylation. Point mutants of Pik127 probed the roles of residues in the KSQ active site, while an AT-swapped version of Pik127 demonstrated that KSQ can also decarboxylate malonyl groups. Mechanisms for how KSQ and KS domains catalyze carbon-carbon chemistry are proposed.

eTOC blurb

For many years, the mechanism employed by the ketosynthase domains of modular polyketide synthases to forge carbon-carbon bonds has remained mysterious. The 2.48-Å resolution, cryo-electron microscopy structure of the priming ketosynthase (KSQ) from the pikromycin synthase reveals how the decarboxylation step of carbon-carbon bond-forming ketosynthases is catalyzed.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Microbes often rely on modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) for the synthesis of biologically active polyketides (Figure 1) (Keatinge-Clay, 2017b). Modular PKSs, in turn, rely on the coordinated action of tens to hundreds of domains. The modular unit of these assembly lines most often contains an acyltransferase (AT) domain that selects malonyl- or methylmalonyl extender units, an acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain that acquires these extender units through an ~18-Å phosphopantetheinyl arm, and a ketosynthase (KS) domain that performs an extension reaction to form a carbon-carbon bond between an ACP-bound extender unit and a growing polyketide. Recently, the boundary of the module was redefined such that KS is the most downstream rather than the most upstream domain, in agreement with how sets of domains evolutionarily co-migrate (Keatinge-Clay, 2017a; Zhang et al., 2017). At the final position of the module, KSs can serve as gatekeepers to ensure that processing enzymes, such as ketoreductases (KRs), dehydratases (DHs), and enoylreductases (ERs), perform their chemistry before passing the polyketide intermediate to the next module (Hirsch et al., 2021a). At the most upstream position of the assembly line, a KS-like enzyme is most commonly present to generate primer units that initiate polyketide synthesis. This enzyme is known as KSQ since a glutamine is at the same position as the reactive cysteine that is acylated by polyketide intermediates in chain-extending KSs (Hirsch et al., 2021a). Despite its importance to polyketide biosynthesis, the carbon-carbon chemistry catalyzed by KSQs and KSs remains mysterious.

Figure 1.

The priming of polyketide assembly lines. a) Schematics of the natural synthase that produces the pikromycin precursor, narbonolide, as well as the engineered synthase, Pik127, that produces a triketide lactone are colored using the updated module boundary. Unlabeled circles are ACPs, and unlabeled half-circles are docking domains. KR0 mediates epimerization rather than reduction, and thioesterase (TE) cyclizes mature polyketides. b) KSQ is the KS-like enzyme that contains a glutamine instead of a reactive cysteine and collaborates with AT and ACP in the first pikromycin module to convert a (2S)-methylmalonyl group into a propionyl primer unit. See also Figure S1 and Tables S1–2.

Historically, the divide-and-conquer approach has been the most successful in studying the architectures of modular PKSs (Keatinge-Clay, 2012). Since most PKS polypeptides contain thousands of residues and are not amenable to crystallography, well-folded portions of these polypeptides, such as domains and didomains, have been individually studied with the hope that the overall architectures of synthases could be assembled from their parts. Even with the plethora of structures that have been obtained, the puzzle has not been solved. Eight years ago, cryo-EM studies were conducted on the third polypeptide of the pikromycin synthase that houses a traditionally-defined module (Dutta et al., 2014; Whicher et al., 2014). The data suggested that the KS+AT portion was arched relative to the extended conformation crystallographically observed for KS+AT didomains, although the maximal resolution of 7 Å was insufficient to explain the clashes expected between the KS and AT domains. Higher resolution cryo-EM reconstructions have since shown KS+AT didomains in both the extended and a newly-observed flexed conformation (Bagde et al., 2021; Cogan et al., 2021).

Ideally, assembly line modules would be studied in the context of intact synthases; however, few natural synthases are small enough to be of practical utility. With the resolution revolution of cryo-EM, we sought to engineer model triketide synthases from the pikromycin assembly line and visualize them (Miyazawa et al., 2021). Pik127 is composed of the first, second, and seventh updated pikromycin modules (Figure 1). This readily-purifiable, ~410 kDa polypeptide was flash-frozen on grids as it was synthesizing its triketide product. The class averages were dominated by its first two domains, KSQ and AT (Bisang et al., 1999). While a small hinge motion of the AT domain results in conformations that are relatively shifted up to 5 Å, all are in the extended conformation. The resolutions of the reconstructions (2.48 Å for KSQ and 2.77 Å for AT) are equivalent to the resolutions of crystallographically-determined assembly line KS+AT didomains (Li et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2006; Whicher et al., 2013). Comparisons with 3 related ketosynthases crystallographically observed bound to their cognate acyl carrier proteins reveal atomic-resolution details for how decarboxylation reaction proceeds in both KSQs and chain-extending KSs (Brauer et al., 2020; Du et al., 2020; Milligan et al., 2019). Swapping the malonyl-specific AT domain from the third pikromycin module into Pik127 demonstrated that the pikromycin KSQ can decarboxylate a malonyl extender unit (Yuzawa et al., 2017), while point mutants of the KSQ active site support a general mechanism for decarboxylation in KSQ and KS enzymes.

RESULTS

Structural determination of Pik(KSQ+AT)1

Pik127 was expressed in Escherichia coli K207-3, an engineered strain harboring the promiscuous Bacillus subtilis Sfp that phosphopantetheinylates ACP domains (Murli et al., 2003). Although this ~410 kDa triketide synthase contains decahistidine tags at both termini, it does not purify well by nickel chromatography. Instead, a potassium phosphate precipitation protocol was developed for the first purification step. Subsequent ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography yielded >95% pure protein (Figure S1). After incubating Pik127 in a potassium phosphate solution containing its substrates, (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA and NADPH, it was applied to a grid and plunged into liquid ethane.

The class averages were dominated by particles resembling crystallographically-determined assembly line KS+AT didomains [Ery(KS3+AT4), PDBs 2QO3 (Tang et al., 2007) and 6C9U (Li et al., 2018); Ery(KS5+AT6), PDB 2HG4 (Tang et al., 2006); Cur(KS8+AT9), PDB 4MZ0 (Whicher et al., 2013)] (Figures 2–3 and S2–S3, Table 1). While the initial three-dimensional reconstruction was unambiguously of the first two domains of Pik127, Pik(KSQ+AT)1 (92 kDa as a monomer, 184 kDa as a dimer), the density for PikAT1 was relatively weak. Variability analysis revealed a conformational ensemble due to a slight hinge motion between the flanking subdomain (FSD) and AT (Videos S1–2). This hinge motion is distinct from that observed between the small and large subdomains of AT in related synthases in the presence of substrates (Brauer et al., 2020; Rittner et al., 2020; Rittner et al., 2018). While PikKSQ1 and its FSD could be reconstructed at 2.48-Å resolution, local refinement was necessary to reconstruct PikAT1 to 2.77-Å resolution. No density is observed for the 88 residues upstream of PikKSQ1, a surface loop in PikKSQ1 (residues 448–492), the 21 residues connecting PikKSQ1 and PikAT1 (residues 518–538), repetitive loop residues in the FSD (residues 565–580) (Hirsch et al., 2021b), or the loop connecting the FSD to the LPTYxFxxxxxW motif (residues 953–959). Extra density is observed for the PikAT1 catalytic serine, Ser724, but is insufficient to accurately model the (2S)-methylmalonyl group likely responsible for it. No significant sequence or structural differences are apparent between PikAT1 and methylmalonyl-selective ATs located downstream of chain-extending KSs; the FSD also appears equivalent to those downstream of chain-extending KSs (Tables S1–S2).

Figure 2.

The Pik(KSQ+AT)1 dimer. PikKSQ1 and the flanking subdomain (FSD) were reconstructed at 2.48-Å resolution, while PikAT1 was locally refined at 2.77-Å resolution. Variability analysis revealed a hinge motion between PikAT1 and the FSD that results in an ~5-Å displacement at the distal ends of the ATs. Viewed along the twofold axis of Pik(KSQ+AT)1, the conformational extrema show the PikAT1 domains hinged in (beige) toward the axis and hinged out (green) away from the axis. See also Figure S2 and Videos S1–2.

Figure 3.

Features in the active sites. a) A stereodiagram of the PikKSQ1 active site (map contoured at 2.0 r.m.s.d.) shows the invariant histidines (H395 and H435) and eponymous glutamine (Q260). The glutamine side chain carbonyl coordinates with backbone NHs, equivalently to a thioester carbonyl in an acylated KS. Its oxygen is positioned in the primary oxyanion hole, while water molecule Wat1 is positioned in the secondary oxyanion hole that aids in the decarboxylation reaction. b) A stereodiagram of the PikAT1 active site (map contoured at 1.0 r.m.s.d.) shows density attached to the serine that transfers (2S)-methylmalonyl groups from (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA to PikACP1, S724. See also Figure S3.

Table 1.

Acquisition parameters and model validation.

| Microscope | UT Austin Titan Krios G3 | |

| Imaging system | Gatan K3 | |

| Illumination mode | Nanoprobe, 1.2 μm parallel | |

| High tension | 300 kV | |

| Pixel size (counting) | 0.81 Å pix−1 | |

| Underfocus range | 0.8 – 1.5 μm | |

| Fluence | 70 e− Å−2 | |

| Dose rate on the camera | 10 e− pix−1 s−1 | |

| Exposure time | 5 s | |

| Frames per movie | 100 | |

| Movies collected | 7196 | |

| Acquisition software | SerialEM | |

| Acquisition method | 3×3 hole beam-image shift with beam tilt and astigmatism compensation | |

| PikKSQ1+FSD dimer | PikAT1 monomer | |

| Map to model FSC (0.5 threshold, masked/unmasked) (Å) | 2.45/2.47 | 2.90/2.93 |

| Model composition | ||

| No. Atoms | 7711 | 2325 |

| No. Residues | 1044 | 315 |

| No. Water | 55 | 0 |

| No. Ligands | 0 | 0 |

| Bonds (RMSD) | ||

| Length (Å) (# > 4 σ) | 0.005 (0) | 0.006 (1) |

| Angles (°) (# > 4 σ) | 1.131 (2) | 1.008 (0) |

| MolProbity score | 1.48 | 2.53 |

| Clash score | 6.13 | 10.40 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Outliers | 0.39 | 0.32 |

| Allowed | 2.35 | 8.63 |

| Favored | 97.25 | 91.05 |

| Rama-Z (Rama. Plot Z-score, RMSD) | ||

| Whole (n = 1020, 313) | −0.37 (0.24) | −2.56 (0.45) |

| Helix (n = 370, 139) | −0.40 (0.23) | −0.98 (0.41) |

| Sheet (n = 118, 34) | 1.42 (0.45) | −1.66 (0.82) |

| Loop (n = 532, 140) | −0.43 (0.26) | −2.42 (0.52) |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.53 | 4.26 |

| Cβ outliers (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Peptide plane (%) | ||

| Cis-proline/general | 0.0/0.0 | 0.0/0.0 |

| Twisted proline/general | 0.0/0.0 | 0.0/0.0 |

| CaBLAM outliers (%) | 1.41 | 2.57 |

Comparison between KSQ and chain-extending ketosynthases

Comparisons can be made between PikKSQ1 and chain-extending KSs from the erythromycin, curacin, and lasalocid assembly lines - EryKS3, EryKS5, CurKS8, and LsdKS7 (PDBs 6C9U, 2HG4, 4MZ0, 7S6B) (Bagde et al., 2021; Li et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2007; Whicher et al., 2013). Several features near the active site are more similar to those of CurKS8 than those of EryKS3, EryKS5, or LsdKS7 [e.g., the YVR motif (residues 321–323) instead of the TGW motif, the KTNIGHLE motif (residues 430–437) instead of the KSNIGHTQ motif]. Sequence alignments support this observation, revealing a closer relationship between KSQs and KSs from cyanobacterial/myxobacterial PKSs than between KSQs and KSs from actinomycete PKSs (Tables S1–S2). KSQs can also be compared to the ketosynthases of Type II synthases (unlike the domain-fused Type I modular PKSs, each domain in Type II PKSs is a separate polypeptide; “ketosynthase” and “acyl carrier protein” are spelled out to refer to both Type I and Type II synthases, whereas the acronyms “KS” and “ACP” refers to domains within Type I synthases). Three Type II ketosynthases have been structurally observed complexed with their cognate acyl carrier proteins [E. coli FabB, PDB 5KOF (2.40-Å resolution) (Milligan et al., 2019); anthraquinone ketosynthase/chain length factor, PDB 6SMP (2.90-Å resolution) (Brauer et al., 2020); ishigamide ketosynthase/chain length factor, PDB 6KXF (1.98-Å resolution) (Du et al., 2020)]. While these ketosynthases are from diverse pathways, the interactions they make with the phosphopantetheinyl arm are highly conserved.

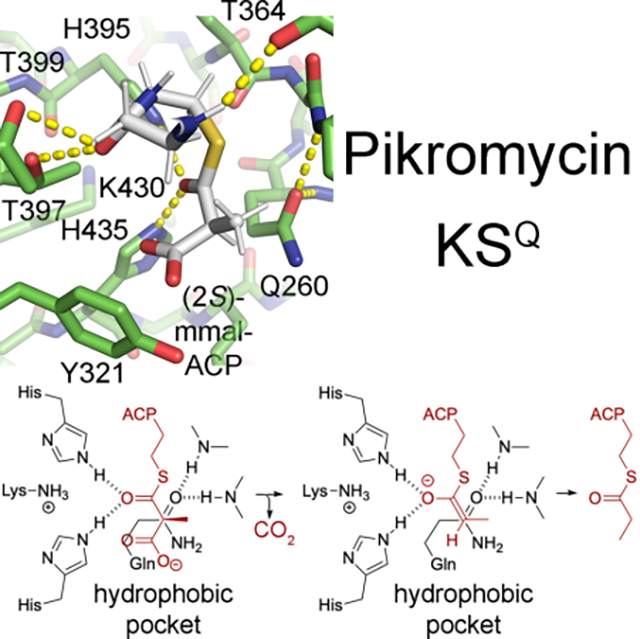

Since KSQs and chain-extending ketosynthases decarboxylate α-carboxyacyl groups, investigating the features shared between these enzymes could help reveal how decarboxylation is mediated (Figures 4 and S4) (Bisang et al., 1999). The catalytic histidines of PikKSQ1, H395 and H435, are in the same positions and orientations as in the FabB and ishigamide complexes, in which they coordinate the equivalent of the thioester carbonyl of an acylated acyl carrier protein. Two nearly invariant threonines in PikKSQ1, T397 and T399, are in the same positions as in the FabB, anthraquinone, and ishigamide complexes, in which they coordinate the most distal carbonyl of the phosphopantetheinyl arm. A conserved TxP motif in PikKSQ1 (residues 364–366) forms a loop that possesses the same structure as loops formed by the equivalent residues in the FabB, anthraquinone, and ishigamide complexes, in which the backbone carbonyl of the first residue coordinates the proximal NH of the phosphopantetheinyl arm. A SPREA motif present on the surface of PikKSQ1 (residues 166–170) and highly conserved in KSQs and KSs, helps form the condensation site that interfaces with the downstream ACP, as observed in recent cryo-EM reconstructions from the erythromycin and lasalocid PKSs (PDBs 7M7F & 7S6C) (Bagde et al., 2021; Cogan et al., 2021).

Figure 4.

Carbon-carbon chemistry performed by KSQ and KS. A (2S)-methylmalonyl-S-pantetheinyl group was equivalently positioned into PikKSQ1 and an acylated EryKS5 by placing the phosphopantetheinyl group as in complexed ketosynthases (PDBs 5KOF, 6KXF, 6SMP) and the thioester in its lowest-energy cis-geometry (Figure S4). Stereodiagrams (same view as in Figure 3a) and schematics show the similarities between the active sites of KSQ and KS as well as the reactions they catalyze. In KSQs, the residue represented by Y321 has only been observed to be tyrosine or phenylalanine (Table S1). In KSs, the residue represented by F260 is most commonly a threonine; the threonine methyl group and a tryptophan two residues downstream usually form the hydrophobic environment encountered by the carboxylate, as in LsdKS7 (PDB 7S6B). See also Figure S4.

Since KSQs do not catalyze transacylation and condensation like chain-extending ketosynthases, investigating the features that differ between these enzymes could help reveal how these reactions are mediated by chain-extending ketosynthases. Of the many differences between PikKSQ1 and chain-extending ketosynthases (Figures S4–S5, Table S2), the most prominent is the eponymous glutamine. As hypothesized, this residue (Q260) mimics an acylated cysteine, with its carbonyl coordinating the NH of the residue upstream of the GGTNCH motif (M504) as well as its own NH (Rittner et al., 2020; Witkowski et al., 1999). The oxygen is located in the same position as the oxyanion hole of chain-extending ketosynthases thought to aid in both the transacylation and condensation reactions (Du et al., 2020). Within PikKSQ1, several large side chains occupy what is the acyl chain binding tunnel of KSs: the second and third residues of the dimer interface loop (I210 and W211) are usually large hydrophobes in KSQs, while the fourth residue of this motif (D212) and an arginine (R236) form a salt bridge conserved in KSQs but not KSs (Hirsch, 2021). Another deviation from actinomycete KSs in this region is a hydrogen-bond network between YVR motif (residues 321–323 in PikKSQ1, equivalent to the TGW motif), a glutamate (E437 in PikKSQ1, equivalent to the glutamine of the KSNIGHTQ motif), and asparagines from an NLN motif (residues 288–290 in PikKSQ1, equivalent to the TVM motif) (Hirsch, 2021).

The KSQ dimer interface is better packed than KS interfaces (5923 vs. 4536 Å2 buried surface area for PikKSQ1 vs. EryKS5), containing glycines (G237 and G505) rather than serines, a methionine upstream of the xGTNxH motif (M504) instead of an isoleucine/valine, a phenylalanine (F302) or leucine instead of a glutamine, and a hydrogen bond network (N241, S253, N356’, and G505’) not present in KSs. Differences between surface residues near the active site entrances of KSQs and KSs also exist, with unconserved amino acids (residues 361, 401, 408, and 471) instead of a highly-conserved asparagine, leucine, glutamine, and aspartate in KSs, and a glycine (G303) instead of a conserved arginine. Facing the downstream module, an unconserved and often shorter loop (residues 130–147) is present in KSQs rather than a conserved structured loop in KSs recently observed to interface with downstream KR domains (Bagde et al., 2021; Cogan et al., 2021).

PikKSQ1 possesses an active site equivalent in shape and chemistry to those of KSs as well as Type II ketosynthases observed either covalently bound to a phosphopantetheinyl arm or chemically-reactive mimic (PDBs 5KOF, 6SMP, 6KXF) (Figures 4 and S4) (Brauer et al., 2020; Du et al., 2020; Milligan et al., 2019). Using these complexed structures and the lowest energy cis-geometry for the thioester, (2S)-methylmalonyl-S-phosphopantetheine was modeled in both PikKSQ1 and an acylated EryKS5 (Hirsch, 2021; Nagy et al., 2004). The conserved interactions between the distal phophopantetheinyl carbonyl and the threonine pair (T397 and T399 in PikKSQ1) as well as the thioester carbonyl with the histidine pair (H395 and H435 in PikKSQ1) place the α-carboxyacyl group in a hydrophobic pocket in which the carboxylate is closest to an aromatic sidechain (Y321 in PikKSQ1). The alignment of the Cα-carboxylate σ orbital with the thioester carbon p orbital would enable a decarboxylation that generates the cis-enolate intermediate anticipated for KSs, since their products possess an inverted configuration at the α-carbon (Bach and Canepa, 1996; Keatinge-Clay, 2016). The orientation that would generate a trans-enolate is sterically inaccessible (due to the Q260 and M504 sidechains in PikKSQ1).

Probing PikKSQ1 through mutagenesis and AT swapping

To learn more about how residues in the active site of PikKSQ1 contribute to its activity, several were selected for mutagenesis within a 2-polypeptide version of Pik127 (Miyazawa et al., 2021). Each of the threonines proposed to coordinate the distal phosphopantetheinyl carbonyl (T397 and T399) were mutated to alanine. The tyrosine that may play the largest role in desolvating and orienting the carboxylate (Y321) was mutated to methionine and leucine. The eponymous glutamine (Q260) was mutated to alanine, serine, and cysteine. The contribution of the eponymous glutamine to KSQ activity has not been accurately measured. When this residue was mutated to alanine in a monensin/erythromycin hybrid synthase (the first 3 domains of the monensin assembly line swapped for the first 2 domains of the engineered triketide synthase DEBS1+TE), the point mutant was reported to be >10-fold less active (Bisang et al., 1999). After the Pik127 point mutants were constructed, their productivities were compared to the unmutated Pik127 in E. coli K207–3 (Figures 5 and S5, Data S1) (Miyazawa et al., 2021). Each Pik127 point mutant showed decreased activity, with the most deleterious mutations being Q260A, Q260C, Y321L, and Y321M.

Figure 5.

Probing KSQ activity. a) Polyketide production of 2-polypeptide Pik127 compared with point mutants of active site residues. b) Polyketide production of 2-polypeptide Pik127 in which PikAT1 was swapped for PikAT3, which naturally selects for malonyl extender units. Data points represent LC/MS measurements of ethyl acetate extracts from the E. coli K207-3 cultures. Top panel measurements are from duplicate experiments, and bottom panel measurements are from triplicate experiments. See also Figure S5 and Data S1.

Since no sequence differences between KSQs that decarboxylate methylmalonyl groups and those that decarboxylate malonyl groups are apparent, we hypothesized that if PikAT1 were swapped with the malonyl-selective PikAT3 in 2-polypeptide Pik127 then PikKSQ1 would be able to convert malonyl extender units into acetyl primer units (Table 1). This swap was performed using established boundaries for AT swapping (Miyazawa et al., 2021; Yuzawa et al., 2017). The AT-swapped 2-polypeptide Pik127 produced both the anticipated acetyl-primed triketide lactone as well as the propionyl-primed product, albeit at 6% the overall titer of 2-polypeptide Pik127 (Figures 5 and S5).

DISCUSSION

Modular PKSs are challenging to examine through traditional structural biology methods primarily due to their size. However, the resolution revolution of cryo-EM has opened new avenues to explore these synthetic machines (Bagde et al., 2021; Cogan et al., 2021; Herbst et al., 2018; Wang, 2021). We were thus motivated to engineer the trimodular synthase Pik127, which is smaller but easier to study than microbial PKSs, and observe it using modern electron microscopy instruments and methods (Miyazawa et al., 2021). Surprisingly, the only portion of Pik127 apparent in the class averages is the homodimeric Pik(KSQ+AT)1. The reconstruction of PikKSQ1 at 2.48-Å resolution enabled us to propose how it converts an α-carboxyacyl group into a primer unit to initiate polyketide synthesis.

Recent structural investigations of 3 Type II ketosynthases complexed with their acyl carrier proteins reveal that the phosphopantetheinyl arm is equivalently bound by diverse ketosynthases (Brauer et al., 2020; Du et al., 2020; Milligan et al., 2019). In each complex, the distal carbonyl of the arm coordinates with a threonine/serine pair. In the FabG and ishigamide complexes, the equivalents of thioester carbonyls coordinate with a histidine pair thought to stabilize the enolate produced by the decarboxylation reaction (Heath and Rock, 2002). Comparisons with substrate-bound biosynthetic thiolases (PDB 1DM3) were not made, even though they share the thiolase fold (Keatinge-Clay, 2016; Modis and Wierenga, 2000) - these enzymes catalyze a decarboxylation-independent condensation, do not contain the distal histidine or the threonines, and oppositely orient the thioester enolate intermediate. As the tunnels in KSQ and KS that bind the phosphopantetheinyl arm are equivalent to those of Type II chain-extending ketosynthases, the (2S)-methylmalonyl-S-phosphopantetheinyl group was modeled into both PikKSQ1 and an acylated EryKS5 (Figures 4 and S4) (Tang et al., 2006). Hydrogen bonds coordinate the proximal NH of the phosphopantetheinyl arm with the first carbonyl of the TxP motif (T364-P366 in PikKSQ1, T303-P305 in EryKS5), the distal carbonyl of the phosphopantetheinyl arm with the nearly invariant threonines (T397 and T399 in PikKSQ1, T336 and T338 in EryKS5), and the thioester carbonyl with the invariant histidines (H395 and H435 in PikKSQ1, H334 and H374 in EryKS5). That the T397A and T397A Pik127 point mutants showed comparable activities (42% and 31%, respectively) matches their proposed equivalent roles in coordinating the distal carbonyl of the phosphopantetheinyl arm.

In the model for PikKSQ1, the methylmalonyl carboxylate is adjacent to the highly conserved Y321 (a sequence alignment of KSQs from all of the characterized PKSs only shows phenylalanine substituting for this tyrosine) (Figures 4 and S4, Table S1). Y321 is equivalent to F229 in E. coli FabB, proposed to play a key role in decarboxylating malonyl-bound acyl carrier proteins (Heath and Rock, 2002). Although the residue in this position in EryKS5 is also aromatic (F260), in LsdKS7 and most other KSs it is a threonine. A superposition of LsdKS7 (PDB 7S6B) reveals that the threonine methyl group as well as the side chain of a highly-conserved tryptophan two residues downstream interact with the carboxylate. In each of these models, the carboxylate-Cα σ-bond is ~30° from alignment with the p-orbital of the thioester carbon, enabling the decarboxylation reaction to yield the anticipated cis-enolate (Bach and Canepa, 1996). The reduced activities of the Y321L and Y321M point mutants of Pik127 (13% for Y321L, 15% for Y321M) are consistent with the important roles hypothesized for the tyrosine of desolvating and orienting the carboxylate. While the proposed mechanism agrees with known ketosynthase structures, it does conflict with an experimental result from the mammalian fatty acid synthase (FAS) in which bicarbonate, rather than carbon dioxide, was detected from the condensation reaction (Witkowski et al., 2002).

Studies of the mammalian FAS also showed that its decarboxylase activity increases when the reactive KS cysteine is acylated, modified by iodoacetamide, or mutated to other residues (Witkowski et al., 1999). As the glutamine mutant possesses 2–3 orders of magnitude greater activity than the corresponding alanine, asparagine, serine, glycine, and threonine mutants, the glutamine side chain was hypothesized to mimic an acylated cysteine (Witkowski et al., 1999). Here we show that mutating the glutamine of KSQ to alanine within the triketide synthase Pik127 decreases its activity 12-fold (Figure 5) (Bisang et al., 1999). In the Q260A mutant an ordered water molecule would need to substitute for the glutamine side chain oxygen to coordinate with the A260 and M504 NHs and may not function as well in ordering the active site for the decarboxylation reaction. Some enzymes with the same catalytic role as KSQ contain a serine rather than glutamine in their active sites (Table S1). An AlphaFold-generated model of such an enzyme (the malonyl-decarboxylating amphotericin KSS) shows the serine in position to stabilize a water molecule coordinated between the aforementioned backbone NHs (Figure S4) (Jumper et al., 2021). Indeed, the Q260S point mutant of Pik127 is 80% as active as Pik127. That FAS KSs gain decarboxylase activity when the cysteine is mutated and KSQs retain significant activity when the glutamine is mutated indicates that the cysteine thiolate inhibits the binding of α-carboxyacyl groups. This is supported by the large loss in activity observed for the Q260C point mutant of Pik127.

An atomic-level schematic can be drawn for how ketosynthases mediate catalysis in a sequential manner (Figure 4). In the unacylated state, the negatively-charged cysteine thiolate and the proximal histidine (H374 in EryKS5) form a hydrogen bond. In the acylated state, the cysteine thioester oxygen is coordinated in the primary oxyanion hole (between the C199 and V441 NHs in EryKS5) and the proximal histidine is liberated. After acyl chain transfer to the ketosynthase, but not before, both the distal and proximal histidines (H334 and H374 in EryKS5) are available to coordinate the thioester carbonyl oxygen of the second substrate, an α-carboxyacylated acyl carrier protein, in a secondary oxyanion hole. Following the decarboxylation reaction, the enolate acquires the acyl chain and the elongated product is released. A hydrogen bond again forms between the cysteine thiolate and the proximal histidine, enabling a subsequent reaction cycle.

The generation of the acetyl-primed product by AT-swapped Pik127 demonstrates that the pikromycin KSQ can decarboxylate malonyl groups. Why this synthase shows only 6% the productivity of the unswapped synthase and propionyl-primed product is still generated is not clear. One possibility is that the AT domain loses its activity in its new location. Even using established boundaries, swapped ATs do not always work properly in engineered assembly lines (Kalkreuter et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Another possibility is that PikKS1 does not accept an acetyl group as efficiently as a propionyl group - acetyl-accepting KSs possess a different set of substrate tunnel residues from those that accept propionyl groups (Hirsch et al., 2021a).

Recently, the KSQ+AT didomain from the FD-891 PKS was solved to 2.55-Å resolution by x-ray crystallography (Chisuga et al., 2022). Although its AT possesses differences related to its specificity for malonyl-CoA, the KSQ is very similar to PikKSQ1 (Cα r.m.s.d. = 0.64 Å). While the FD-891 KSQ decarboxylates malonyl substrates, its active site residues are both equivalently positioned and conserved (Figure S4, Table S1). In an attempt to determine how the malonyl-S-phosphopantetheinyl portion of the substrate associates with KSQs and KSs, the authors soaked nitroacetyl pantetheinamide into the crystals. This compound was observed with its nitro group, designed to mimic the malonyl carboxylate, bound between the invariant histidines and the carbonyl of its amide, designed to mimic the thioester, bound between the threonines. If a malonyl-S-phosphopantetheinyl moiety yields an enolate from this conformation in a KS, the enolate would need to make an unlikely shift of more than 3 Å to attack the acylated cysteine. Substrates and their analogs may need to be linked to ACP domains to be properly positioned for the decarboxylation reaction. Perhaps the reason (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA is not a good substrate for KSQs or KSs is because it is not held in register by an ACP. Interactions between ACP and KS could help overcome the energetic barrier of desolvating the carboxylate group (Stunkard et al., 2019).

In this study, cryo-EM helped elucidate how chemistry is mediated by KSQs and KSs. That electron microscopy methods can now be applied to examine the intricate details of how carbon-carbon bonds are broken and formed within these enormous synthases speaks to the large advances in this area of structural biology. Many more cryo-EM investigations of polyketide assembly lines are warranted to further our understanding of the chemistry they catalyze as well as our ability to harness them.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Adrian Keatinge-Clay (adriankc@utexas.edu).

Materials availability

Plasmids generated in this study are available upon request.

Data and code availability

Data.

The coordinates and associated maps for Pik(KSQ+AT)1 dimer have been deposited in EMDB and PDB under accession codes EMD-26839 and 7UWR, respectively. The coordinates and associated map for the PikAT1 monomer have been deposited in EMDB and PDB under accession codes EMD-27094 and 8CZC, respectively.

Code.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

E. coli DH5α (standard lab strain)

E. coli K207-3 (strain engineered by Murli et al., 2003)

METHOD DETAILS

Sample preparation

E. coli K207-3 cells transformed with pTM1, the expression plasmid for 1-polypeptide Pik127 (Miyazawa et al., 2021), were grown in 4 L of LB media with 50 mg L−1 kanamycin at 37 °C at 240 rpm. When OD600 = 0.6 the temperature was decreased to 15 °C and both 0.1 mM IPTG and 2 mM sodium propionate were supplied. After 16 h the cells were collected (4000 × g, 10 min) and resuspended in 50 mL of 1.5 M potassium phosphate, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. Following sonication the lysed cells were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 10 min) and the pellet was resuspended in 200 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. After centrifuging again (30,000 × g, 30 min) the supernatant was applied to an anion exchange column (5 mL HiTrap Q HP, GE Healthcare) and a gradient was run from 200 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5 to 800 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. Fractions containing Pik127 were collected, concentrated to 10 mg/mL, and 1 mL was applied to a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column with 200 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM TCEP pH 7.5 as the mobile phase. A fraction containing Pik127 was concentrated to 1.5 mg/mL (Figure S1).

Grid preparation

Purified Pik127 was incubated with 3 mM (2RS)-methylmalonyl-CoA and 1 mM NADPH at 25 °C. After 30 min, 3.5 μL was vitrified on Quantifoil holey carbon copper grids (R2/2 200 mesh, Quantifoil Micro Tools) that were plasma treated for 30 s using a Gatan Solarus plasma cleaner with an equal mixture of H2 and O2. The sample had been allowed to absorb for 5 s before blotting with 0 blot force for 3 s with a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) operating at 10 °C and 100% relative humidity prior to plunge-freezing in liquid nitrogen-cooled liquid ethane.

Data acquisition

All movies were collected on a FEI Titan Krios G3 (Thermo Fisher) equipped with a Gatan K3 detector at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV and an underfocus range of 0.8–1.5 μm. Imaging was performed at 29,000x nominal magnification, corresponding to a 0.81 Å pix−1 counting pixel size. A 70 e− dose per movie was fractionated evenly across 100 frames, using 2x hardware binning, and a dose on the camera of 10 e− pix−1s−1. A total of 7196 movies were collected semi-automatedly in SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2005), with 4284 at 0° tilt and 2912 at 30° tilt to alleviate a mild preferred orientation bias.

Image processing

All image processing was performed in cryoSPARC v3.2 (Punjani et al., 2017) (Table 1, Figures S2–S3). Movies were patch motion corrected and dose weighted using algorithms in cryoSPARC. Contrast transfer function (CTF) estimation was performed in patches. Particles were first picked using a blob (Gaussian) template and subjected to 2D classification, from which two classes were selected as particle-picking templates. 2,350,020 newly picked particles, extracted with a 300-pixel box size, were subjected to 2D classification. Three classes containing 312,075 particles were used to calculate an ab initio volume using stochastic gradient descent, and that volume was subsequently used as a reference for homogeneous refinement, applying C2 symmetry. Heterogeneous refinement was performed to split the particles into 4 classes. One of these classes, containing 184,737 particles, was homogenously refined, applying C2 symmetry. Density modification in Phenix produced a map with an estimated 2.48-Å resolution (Liebschner et al., 2019). Methylmalonyl-CoA and NADPH are likely unnecessary to obtaining high resolution maps since samples without these substrates also yielded reconstructions of Pik(KSQ+AT)1. As the density surrounding PikAT1 was weak, the particles were C2 symmetry expanded, and local refinement was performed using a mask surrounding one of the PikAT1 domains, penalizing rotations and shifts with standard deviations of 4° and 2 Å. Density modification in Phenix produced a map with an estimated 2.77-Å resolution. The C2 symmetry expanded particles were also subjected to 3D variability analysis with a filter resolution of 4 Å and a mask encompassing the Pik(KSQ+AT)1 dimer. One of the 3 component trajectories revealed the PikAT1 hinge motion (Figures 2 and S2, Supplementary Videos 1–2).

Model building

The initial model was generated by homology modeling Pik(KSQ+AT)1 with ProtMod using Ery(KS3+AT4) (PDB 2QO3) as a reference (Jaroszewski et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2007) (Table 1, Figures S2–S3). The PikKSQ1+FSD portion of the model was fit into the C2-consensus density in ChimeraX (Pettersen et al., 2021) and subsequently built and refined using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010), ISOLDE (Croll, 2018), and Phenix (Liebschner et al., 2019). The PikAT1 portion of the model was similarly fit into the map derived from the local refinement of the AT domain in ChimeraX and subsequently built and refined using Coot, ISOLDE, and Phenix.

Construction and analysis of Pik127 variants

PCR and Gibson assembly were used to modify the first of two expression plasmids that encode 2-polypeptide Pik127 (pTM2 & pTM3) to generate 2-polypeptide Pik127 point mutants and 2-polypeptide AT-swapped Pik127 (Miyazawa et al., 2021)(Table S3). To mutate residues in PikKSQ1, two halves of the first plasmid were amplified with mutagenic primers. These amplicons were assembled and transformed into E. coli DH5α. To replace PikAT1 with PikAT3 a 3-piece Gibson assembly was performed that included an PikAT3-encoding amplicon obtained using Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC 15439 gDNA. The expression plasmids encoding 2-polypeptide Pik127, 2-polypeptide Pik127(Q260A), and 2-polypeptide AT-swapped Pik127 were co-transformed into E. coli K207-3. Cells were shaken at 240 rpm in 50 mL LB media containing 50 mg L−1 kanamycin and 50 mg L−1 streptomycin in 250 mL flasks at 37 °C. From these precultures, 3 mL was used to inoculate 300 mL of production media (5 g L−1 yeast extract, 10 g L−1 casein, 15 g L−1 glycerol, 10 g L−1 NaCl, and 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.6 with 50 mg L−1 kanamycin and 50 mg L−1 streptomycin) in each 2.8 L non-baffled Fernbach flask. Cells were shaken at 240 rpm at 37 °C until OD600 = 0.6. They were then cooled to 19 °C, supplied with 0.1 mM IPTG and 20 mM sodium propionate, and cultured for 6 d. Time points were obtained by adding 5 μL concentrated HCl to 500 μL culture broth, extracting twice with the same volume of ethyl acetate, and concentrating in vacuo. The extract was resuspended in 500 μL of water, and 1 μL was analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) [6230 TOF LC/MS equipped with a Microsorb-MV 300–5 C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 (solvent A, water with 0.1 % formic acid; solvent B, acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. 5– 100% B for 15 min, 100% B for 3 min), positive mode].

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Measurements illustrated in Figure 5 are derived from data in Data S1. Duplicate experiments were performed for panel a, and triplicate experiments were performed for panel b. The averages are plotted along with error bars indicating standard deviations.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. Triketide lactone measurements for Pik127 variants, Related to Figure 5.

Table S1. Multiple sequence alignment of KSQ+AT+ACP and related sequences, Related to Figure 1.

Table S2. Differences between KSQ+AT+ACP and KS+AT+ACP, Related to Figure 1.

Table S3. Primers, templates, and cloning methods used to obtain fragments and assemble expression plasmids for the 2-polypeptide Pik127 variants, Related to STAR Methods.

Video S1. Pik(KSQ+AT)1 hinge motion from variability analysis (top view), Related to Figure 2.

Video S2. Pik(KSQ+AT)1 hinge motion from variability analysis (bottom view), Related to Figure 2.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | NEB | C2987H |

| E. coli K207-3 | Kosan Biosciences | K207-3 |

| Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC 15439 | ATCC | ATCC: 15439 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| kanamycin | VWR | 97061-598 |

| streptomycin | Millipore-Sigma | S6501 |

| methylmalonyl-CoA | Millipore-Sigma | M1762 |

| NADPH | Oriental Yeast Company | 44332900 |

| LB media | Fisher Scientific | BP9723-2 |

| IPTG | Carbosynth | EI05931 |

| sodium propionate | Alfa Aesar | A17440 |

| potassium phosphate | Fisher Scientific | BP362-500 |

| TCEP | UBPBio | P1020 |

| PCR reagents | Roche | KK2602 |

| Gibson reagents | NEB | E5520S |

| genome extraction reagents | Promega | A2920 |

| yeast extract | Fisher Scientific | 210929 |

| casein | Alfa Aesar | A13707 |

| glycerol | Fisher Scientific | G33-1 |

| sodium choride | Fisher Scientific | S271-500 |

| HCl (aq.) | Fisher Scientific | A144-212 |

| ethyl acetate | Fisher Scientific | AA31344M4 |

| formic acid | Fisher Scientific | A117-50 |

| acetonitrile | Fisher Scientific | AC615140025 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Pik(KSQ+AT)1 dimer | This paper | EMDB: EMD-26839 |

| Pik(KSQ+AT)1 dimer | This paper | PDB: 7UWR |

| PikAT1 monomer | This paper | EMDB: EMD-27094 |

| PikAT1 monomer | This paper | PDB: 8CZC |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for Pik127 mutations & AT swap, see Table S3 | Millipore-Sigma | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pTM1 (1-plasmid Pik127) | Miyazawa et al., 2021 | N/A |

| pTM2 & pTM3 (2-plasmid Pik127) | Miyazawa et al., 2021 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| SerialEM | Mastronarde et al., 2005 | https://bio3d.colorado.edu/SerialEM/ |

| cryoSPARC v3.2 | Punjani et. al., 2017 | https://cryosparc.com/ |

| Phenix | Liebschner et al., 2019 | https://phenix-online.org/ |

| ProtMod | Jaroszewski et al., 2011 | https://protmod.godziklab.org/protmod-cgi/protModHome.pl |

| ChimeraX | Pettersen et al., 2021 | https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| Excel | Microsoft | version 16.57 |

| Photoshop | Adobe | 21.1.2 release |

| Other | ||

| Quantifoil R2/2 200 mesh, copper | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Q2100CR2 |

| Vitrobot Mark IV | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| Titan Krios | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| 6230 TOF LC/MS | Agilent Technologies | G6230BA |

| Microsorb-MV C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) | Agilent Technologies | AG-R0086200C5 |

Highlights.

A single-polypeptide triketide lactone synthase is studied by cryo-EM

Pikromycin KSQ and downstream AT are reported at 2.48- and 2.77-Å resolution

The methylmalonyl-S-phosphopantetheinyl group of KSQ substrate is confidently modeled

Structural and functional data support a general mechanism for KSQ and KS enzymes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH (GM106112) and the Welch Foundation (F-1712). We acknowledge the Sauer family for their generous support of the cryo-EM facility.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY STATEMENT

The author list of this paper includes contributors from the location where the research was conducted who participated in the data collection, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of the work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bach RD, and Canepa C (1996). Electronic Factors Influencing the Decarboxylation of beta-Keto Acids. A Model Enzyme Study. J Org Chem 61, 6346–6353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagde SR, Mathews II, Fromme JC, and Kim CY (2021). Modular polyketide synthase contains two reaction chambers that operate asynchronously. Science 374, 723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisang C, Long PF, Cortes J, Westcott J, Crosby J, Matharu AL, Cox RJ, Simpson TJ, Staunton J, and Leadlay PF (1999). A chain initiation factor common to both modular and aromatic polyketide synthases. Nature 401, 502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer A, Zhou Q, Grammbitter GLC, Schmalhofer M, Ruhl M, Kaila VRI, Bode HB, and Groll M (2020). Structural snapshots of the minimal PKS system responsible for octaketide biosynthesis. Nat Chem 12, 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisuga T, Nagai A, Miyanaga A, Goto E, Kishikawa K, Kudo F, and Eguchi T (2022). Structural Insight into the Reaction Mechanism of Ketosynthase-Like Decarboxylase in a Loading Module of Modular Polyketide Synthases. ACS Chem Biol 17, 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan DP, Zhang K, Li X, Li S, Pintilie GD, Roh SH, Craik CS, Chiu W, and Khosla C (2021). Mapping the catalytic conformations of an assembly-line polyketide synthase module. Science 374, 729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll TI (2018). ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D, Katsuyama Y, Horiuchi M, Fushinobu S, Chen A, Davis TD, Burkart MD, and Ohnishi Y (2020). Structural basis for selectivity in a highly reducing type II polyketide synthase. Nat Chem Biol 16, 776–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Whicher JR, Hansen DA, Hale WA, Chemler JA, Congdon GR, Narayan AR, Hakansson K, Sherman DH, Smith JL, et al. (2014). Structure of a modular polyketide synthase. Nature 510, 512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RJ, and Rock CO (2002). The Claisen condensation in biology. Natural Product Reports 19, 581–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst DA, Huitt-Roehl CR, Jakob RP, Kravetz JM, Storm PA, Alley JR, Townsend CA, and Maier T (2018). The structural organization of substrate loading in iterative polyketide synthases. Nat Chem Biol 14, 474–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch M, Fitzgerald BJ, and Keatinge-Clay AT (2021a). How cis-Acyltransferase Assembly-Line Ketosynthases Gatekeep for Processed Polyketide Intermediates. ACS Chem Biol 16, 2515–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch M, Kumru K, Desai RR, Fitzgerald BJ, Miyazawa T, Ray KA, Saif N, Spears S, and Keatinge-Clay AT (2021b). Insights into modular polyketide synthase loops aided by repetitive sequences. Proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch MF, B. J.; Keatinge-Clay AT (2021). How cis-acyltransferase assembly line ketosynthases gatekeep for processed polyketide intermediates. ACS Chem Biol, under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroszewski L, Li ZW, Cai XH, Weber C, and Godzik A (2011). FFAS server: novel features and applications. Nucleic Acids Res 39, W38–W44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Zidek A, Potapenko A, et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkreuter E, CroweTipton JM, Lowell AN, Sherman DH, and Williams GJ (2019). Engineering the Substrate Specificity of a Modular Polyketide Synthase for Installation of Consecutive Non-Natural Extender Units. J Am Chem Soc 141, 1961–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay AT (2012). The structures of type I polyketide synthases. Natural Product Reports 29, 1050–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay AT (2016). Stereocontrol within polyketide assembly lines. Natural Product Reports 33, 141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay AT (2017a). Polyketide Synthase Modules Redefined. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 56, 4658–4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay AT (2017b). The Uncommon Enzymology of Cis-Acyltransferase Assembly Lines. Chem Rev 117, 5334–5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Sevillano N, La Greca F, Deis L, Liu YC, Deller MC, Mathews II, Matsui T, Cane DE, Craik CS, et al. (2018). Structure-Function Analysis of the Extended Conformation of a Polyketide Synthase Module. J Am Chem Soc 140, 6518–6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Baker ML, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Croll TI, Hintze B, Hung LW, Jain S, McCoy AJ, et al. (2019). Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75, 861–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN (2005). Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol 152, 36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JC, Lee DJ, Jackson DR, Schaub AJ, Beld J, Barajas JF, Hale JJ, Luo R, Burkart MD, and Tsai SC (2019). Molecular basis for interactions between an acyl carrier protein and a ketosynthase. Nat Chem Biol 15, 669–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa T, Fitzgerald BJ, and Keatinge-Clay AT (2021). Preparative production of an enantiomeric pair by engineered polyketide synthases. Chem Commun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, and Wierenga RK (2000). Crystallographic analysis of the reaction pathway of Zoogloea ramigera biosynthetic thiolase. J Mol Biol 297, 1171–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murli S, Kennedy J, Dayem LC, Carney JR, and Kealey JT (2003). Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for improved 6-deoxyerythronolide B production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 30, 500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy PI, Tejada FR, Sarver JG, and Messer WS (2004). Conformational analysis and derivation of molecular mechanics parameters for esters and thioesters. J Phys Chem A 108, 10173–10185. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CRC, Meng EEC, Couch GS, Croll TI, Morris JH, and Ferrin TE (2021). UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Science 30, 70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, and Brubaker MA (2017). cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14, 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittner A, Paithankar KS, Himmler A, and Grininger M (2020). Type I fatty acid synthase trapped in the octanoyl-bound state. Protein Sci 29, 589–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittner A, Paithankar KS, Huu KV, and Grininger M (2018). Characterization of the Polyspecific Transferase of Murine Type I Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS) and Implications for Polyketide Synthase (PKS) Engineering. ACS Chem Biol 13, 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard LM, Dixon AD, Huth TJ, and Lohman JR (2019). Sulfonate/Nitro Bearing Methylmalonyl-Thioester Isosteres Applied to Methylmalonyl-CoA Decarboxylase Structure-Function Studies. Journal of the American Chemical Society 141, 5121–5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Chen AY, Kim CY, Cane DE, and Khosla C (2007). Structural and mechanistic analysis of protein interactions in module 3 of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Chem Biol 14, 931–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Kim CY, Mathews II, Cane DE, and Khosla C (2006). The 2.7-Angstrom crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric fragment of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 11124–11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liang J, Yue Q, Li L, Shi Y, Chen G, Li YZ, Bian X, Zhang Y, Zhao G, et al. (2021). Engineering the acyltransferase domain of epothilone polyketide synthase to alter the substrate specificity. Microb Cell Fact 20, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, J.; Chen L; Zhang W; Kong L; Peng C; Su C; Tang Y; Deng Z; Wang Z (2021). Structural basis for the biosynthesis of lovastatin. Nat Commun 12, 867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whicher JR, Dutta S, Hansen DA, Hale WA, Chemler JA, Dosey AM, Narayan AR, Hakansson K, Sherman DH, Smith JL, et al. (2014). Structural rearrangements of a polyketide synthase module during its catalytic cycle. Nature 510, 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whicher JR, Smaga SS, Hansen DA, Brown WC, Gerwick WH, Sherman DH, and Smith JL (2013). Cyanobacterial polyketide synthase docking domains: a tool for engineering natural product biosynthesis. Chem Biol 20, 1340–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski A, Joshi AK, Lindqvist Y, and Smith S (1999). Conversion of a beta-ketoacyl synthase to a malonyl decarboxylase by replacement of the active-site cysteine with glutamine. Biochemistry 38, 11643–11650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski A, Joshi AK, and Smith S (2002). Mechanism of the beta-ketoacyl synthase reaction catalyzed by the animal fatty acid synthase. Biochemistry 41, 10877–10887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa S, Deng K, Wang G, Baidoo EE, Northen TR, Adams PD, Katz L, and Keasling JD (2017). Comprehensive in Vitro Analysis of Acyltransferase Domain Exchanges in Modular Polyketide Synthases and Its Application for Short-Chain Ketone Production. ACS Synth Biol 6, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hashimoto T, Qin B, Hashimoto J, Kozone I, Kawahara T, Okada M, Awakawa T, Ito T, Asakawa Y, et al. (2017). Characterization of Giant Modular PKSs Provides Insight into Genetic Mechanism for Structural Diversification of Aminopolyol Polyketides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 56, 1740–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Triketide lactone measurements for Pik127 variants, Related to Figure 5.

Table S1. Multiple sequence alignment of KSQ+AT+ACP and related sequences, Related to Figure 1.

Table S2. Differences between KSQ+AT+ACP and KS+AT+ACP, Related to Figure 1.

Table S3. Primers, templates, and cloning methods used to obtain fragments and assemble expression plasmids for the 2-polypeptide Pik127 variants, Related to STAR Methods.

Video S1. Pik(KSQ+AT)1 hinge motion from variability analysis (top view), Related to Figure 2.

Video S2. Pik(KSQ+AT)1 hinge motion from variability analysis (bottom view), Related to Figure 2.

Data Availability Statement

Data.

The coordinates and associated maps for Pik(KSQ+AT)1 dimer have been deposited in EMDB and PDB under accession codes EMD-26839 and 7UWR, respectively. The coordinates and associated map for the PikAT1 monomer have been deposited in EMDB and PDB under accession codes EMD-27094 and 8CZC, respectively.

Code.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.