Summary

The COVID19 pandemic highlighted the need for remote diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia. Telephone screening for dementia may facilitate prompt diagnosis and optimisation of care. However, it is not clear how accurate telephone screening tools are compared with face-to-face screening. We searched Cochrane, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, PubMed and Scopus for all English language papers published between January 1975 and February 2021 which compared telephone screening for dementia/ mild cognitive impairment and an in-person reference standard, performed within six-weeks. We subsequently searched paper reference lists and contacted authors if data were missing. Three reviewers independently screened studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed study quality using an adapted version of the Joanna Briggs Institute's critical appraisal tool. Twenty-one studies including 944 participants were found. No one test appears more accurate, with similar validities as in-person testing. Cut-offs for screening differed between studies based on demographics and acceptability thresholds and meta-analysis was not appropriate. Overall the results suggest telephone screening is acceptably sensitive and specific however, given the limited data, this finding must be treated with some caution. It may not be suitable for those with hearing impairments and anxiety around technology. Few studies were carried out in general practice where most screening occurs and further research is recommended in such lower prevalence environments.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Health informatics, NON-CLINICAL, Memory disorders (neurology), Neurology, CLINICAL

Introduction

The progressive cognitive deterioration associated with dementia restricts an individual's capacity to complete routine tasks and retain novel information, and may cause behavioural change.1,2 Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) presents similar symptoms but, unlike dementia, does not significantly affect activities of daily living (ADL). Approximately half of patients with MCI develop dementia; both can be screened for using the same tests. 1

From 2015 to 2030, dementia cases are projected to increase globally by nearly 60%. 3 Prompt dementia diagnosis provides clarity for patients and the opportunity to optimise care, for example by commencing medications to delay progression or arranging power of attorney to help with financial planning. Despite these benefits, in England, nearly a third (31.3%) of cases are undiagnosed. 4

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted dementia diagnosis. In England, diagnostic rates fell from 67.6% (January 2020) to 61.4% (January 2021) in those over 65 years. 5 Similarly secondary care referrals for dementia reduced: presumed reasons being delayed patient help seeking possibly through fear of infection, restructuring of general practice services (primarily offering remote consultation) and healthcare reprioritisation. 6

Screening is one approach to improve the timeliness of dementia diagnosis. Traditionally screening is carried out in a face-to-face general practice consultation using validated tools such as Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), GPCOG and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). However the COVID-19 pandemic has transformed interactions between clinicians and patients, with remote consultation for a time becoming the predominant model in the UK. Remote initial assessment for dementia requires rapid, comprehensive and effective telephone screening tools. Many of these have been available for several decades (e.g. the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) was developed in 1988), 7 but their validity in screening remains uncertain.

Remote consultation is likely to remain a routine part of healthcare beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Home-based tele-assessment may be convenient, 8 time saving and less anxiety-inducing for patients, and may improve access for some patients where there are geographical, mobility and financial barriers to face-to-face clinic assessment.9,10

Despite these advantages, telephone screening is inappropriate for those without a telephone, or apprehensive using them or with hearing, speech or language problems. 9 Absence of non-verbal cues limits physicians’ capacity to assess wellbeing, comprehension and consider alternative aetiologies, 11 although video consultation may be more informative and personable. 12

Previous systematic reviews recognised that telephone screening has utility in identifying high-risk patients, but inclusion of a broad range of tools in the reviews limited their focus and some could be considered outdated due to literature growth.13–15 One review suggested that despite benefits in mitigating geographical inaccessibility, telephone screening was time-consuming and impacted by informational inconsistencies and patient technological engagement. 8

This review adds to previous reviews, providing appraisal of five telephone tools recommended for identifying dementia patients16–18: Telephone Mini-Mental State Examination (T-MMSE), Telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA), Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) and modified (TICSm), and Tele-Test-Your-Memory (Tele-TYM).

Objectives

To assess the validity of telephone cognitive screening tools for MCI and dementia, compared to traditional in-person assessments.

Methods

Inclusion/ exclusion criteria

Studies were included if: the titles and abstracts indicated the evaluation of one of the named telephone screening tools (above) including administration within a test battery or of a culturally modified version; and the telephone screen was validated against a named in-person cognitive assessment, within a maximum timescale of six-weeks in a minimum of 95% of patients (to avoid clinically significant cognitive deterioration between assessments). Assessments were limited to adults but not to specific healthcare setting or participant numbers.

Studies requiring particular software, video or virtual reality, or app based were excluded.

Search methods

We searched six databases: Embase, Cochrane, MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, between 31/01/21–02/02/21. This was limited to English language papers published post-1975 (when the MMSE was developed). The same search strategy (Appendix A) was utilised throughout, conducted by the same researcher.

Title/ abstract screening

Titles and abstracts were initially screened by the first author (CR), and a random 20% of papers were considered by a second and third author (KF, BM), there were no discrepancies between reviewers on decisions to exclude.

Full-Text review

Of the papers which met the title/ abstract screening 25% had a full-text review by a second author (KF) to establish whether they continued to meet criteria, there were no discrepancies.

Data extraction

Study data were extracted and tabulated by CR and cross-checked by KF and BM. Where data was missing authors were contacted. The following data was extracted from each study (Table 2):

Author(s), date

Sample size (included in study data analysis)

Exclusion/ inclusion criteria

Sample characteristics: age, educational level and sex (if provided)

Telephone screening tool (including maximum score and language adaptations)

The reference in-person diagnostic tool

Time interval between screening and diagnostic tests

Major findings

Study limitations

Table 2.

Summary of included studies.

| Author | Number of participants | Recruitment | Accuracy of Telephone screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) and modified versions (TICSm) | |||

| Zietemann et al. 22 | 105 | DEDEMAS study | Sensitivity = 73% Specificity = 61% *Cut-off 36 for MCI post stroke |

| Dal Forno et al. 29 | 109 | Outpatients with suspected cognitive impairment | Sensitivity = 84% Specificity = 86% *Cut-off 28 for Alzheimer's disease |

| Konagaya et al. 30 | 135 | Memory clinic |

Sensitivity 98.0% Specificity 90.7% *Cut-off 33 for Alzheimer's disease |

| Desmond et al. 33 | 72 | Stroke patients | Sensitivity = 100% Specificity = 83% * Cut-off of <25 for dementia post stroke |

| Barber & Stott 39 | 64 | Stroke outpatients |

Sensitivity = 88% Specificity = 85% *Cut-off 28 for post stroke dementia (TICS) Sensitivity = 92% Specificity = 80%) *Cut-off 20 for post stroke dementia (TICSm) |

| Seo et al. 25 | 230 | Geriatric patients registered in early detection programme for dementia |

Sensitivity = 87.1% Specificity = 90.0% * Cut-off 24/5 for dementia (TICS) Sensitivity = 88.2% Specificity = 90.0% * Cut-off 23/4 for dementia (TICSm) |

| Cook et al. 27 | 71 | ≥65 years olds in community with memory concerns | Sensitivity = 82.4% Specificity 87.0% *Cut-off 33/4 for amnestic MCI |

| Baccaro et al. 28 | 61 | Stroke mortality and morbidity study (EMMA study) | Sensitivity = 91.5% Specificity = 71.4% *Cut-off 14/5 for cognitive impairment post-stroke |

| Vercambre et al. 32 | 120 | Etude epidemiologique de femmes de l’education nationale |

Sensitivity = 68% Specificity = 89% * Cut-off 30 for cognitive impairment Sensitivity = 86% Specificity = 60% * Cut-off 33 cognitive impairment |

| Graff-Radford et al. 37 | 128 | Community by ZIP code | Sensitivity = 68% Specificity = 75% *Cut-off <31 for dementia |

| Duff et al. 38 | 123 | Community | |

| Lines et al. 41 | 676 | PRAISE study | |

| Telephone Mini-Mental State Examination (T-MMSE) | |||

| Naharci et al. 21 | 104 | Geriatric Outpatient Clinic |

Sensitivity = 96.8% Specificity = 90.2% *Cut-off 22 for Alzheimer's disease |

| Camozzato et al. 23 | 133 | Community |

Sensitivity = 95% Specificity = 84% *Cut-off 15 for Alzheimer's disease |

| Wong & Fong 26 | 65 | Acute regional hospital |

Sensitivity = 100% Specificity = 96.7% *Cut-off 16 for dementia |

| Newkirk et al. 31 | 46 | Alzheimer's Center | |

| Metitieri et al. 34 | 104 | Alzheimer's unit | |

| Roccaforte et al. 36 | 100 | Geriatric Assessment centre |

ALFI-MMSE sensitivity = 67%; specificity = 100% (compared to in-person MMSE sensitivity = 68%; specificity = 100%) |

| Kennedy et al. 40 | 402 | University of Alabama Birmingham Study of Ageing II | |

| Telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA) | |||

| Zietemann et al. 22 | 105 | DEDEMAS study (Determinants of Dementia After Stroke) | Sensitivity = 81% Specificity = 73% * Cut off <19 for MCI post-stroke |

| Wong et al. 35 | 104 | STRIDE study | |

| Tele-Test-Your-Memory (Tele-TYM) | |||

| Brown et al. 24 | 81 | Memory clinic |

Optimal cut-off at ≥43 for screening for

cognitive impairment Sensitivity = 78% Specificity = 69% *Cut-off ≥43 for cognitive impairment |

Statistical analysis

Studies were categorised by screening tool. Subsequently their scoring system, baseline characteristics, diagnostic criteria and relevant cognitive condition were compared to minimise clinical baseline and study heterogeneity.

The outcome measures - sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) - were extracted by study. Positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR) were calculated with fixed and random-effects models applied for comparison of heterogeneity. It was determined the studies were too heterogenous for meta-analysis.

Study quality

Quality and risk of bias were examined using an adapted and combined version of the Joanna Briggs Institute's critical appraisal tools. Checklists for diagnostic accuracy and cross-sectional studies were integrated for comprehensive analysis of quality (Appendix B).19,20 Critical analysis was conducted from 06/02/21- 04/03/21, with a quality assessment table produced (Table 1).

Table 1.

Joanna briggs institute quality assessment table.

| Selection bias | Confounders | Test Accuracy | Performance/detection bias | Attrition bias |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Naharci et al. 21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Zietemann et al. 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Camozzato et al. 23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Brown et al. 24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seo et al. 25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wong & Fong 26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cook et al. 27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Baccaro et al. 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dal Forno et al. 29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Konagaya et al. 30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Newkirk et al. 31 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vercambre et al. 32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Desmond et al. 33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Metitieri et al. 34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wong et al. 35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Roccaforte et al. 36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Graff-Radford et al. 37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Duff et al. 38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Barber & Stott 39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kennedy et al. 40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lines et al. 41 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Risk of bias | Low risk of bias |

|

High risk of bias |

|

Unclear |

|

||||

| ||||||||||

Results

Search results

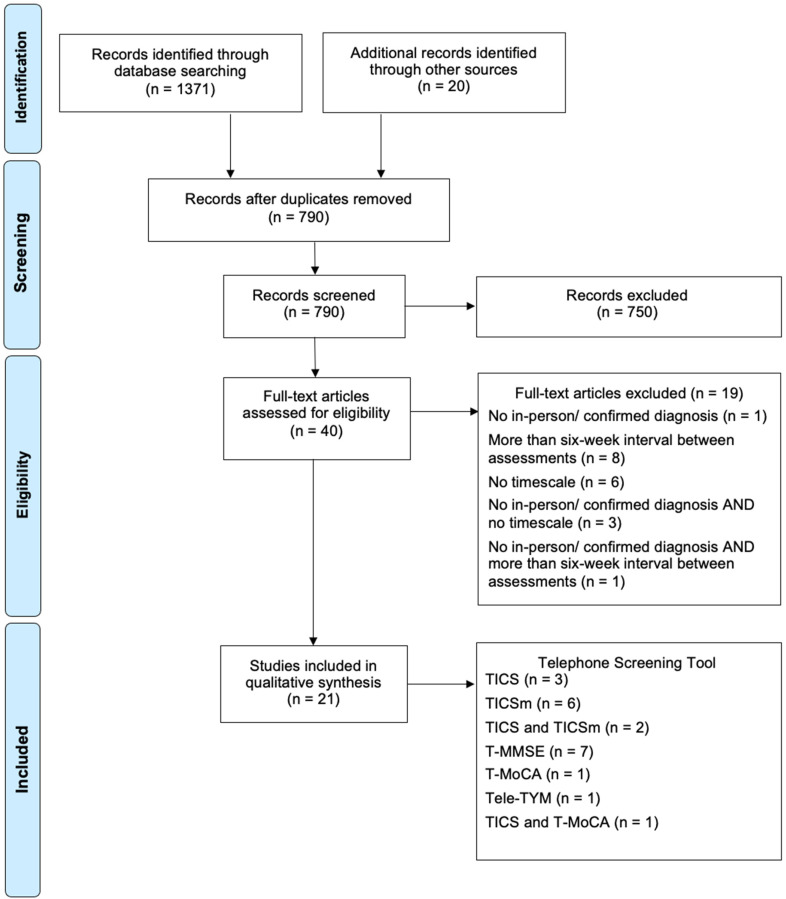

The search strategy returned 1371 papers: 327 Embase, 447 Cochrane, 150 MEDLINE, 147 PubMed, 119 Scopus, and 181 Web of Science. Papers were checked for retractions (none). Removing duplicates, 770 studies remained. A further 20 papers were included from the recommendations of experts within Memory Assessment Services, and references from prominent papers.

Subsequently, 790 records’ titles and abstracts were screened.

750 records were then excluded, not fulfilling criteria. Two other authors (KF and BM) checked 20% of these inclusions and exclusions and reported full agreement.

Of the 40 included papers, 25% were also screened by a second examiner (KF) without disputation.

Post full-text examination, a further 19 papers were excluded (Appendix C). Five papers had no in-person comparison test or diagnosis; nine were outside the time limit. Fourteen failed to mention a timescale between assessments; follow-up emails were sent, allowing three weeks to respond, resulting in exclusion of a further nine papers. Five responses were recorded, all meeting the six-week criteria.

In total, 21 papers were included for data-analysis and synthesis.

Quality of included studies

The quality of the 21 studies was appraised using a modified Joanna Briggs Institute checklist (Appendix B); each received a score out of ten (Table 1). Two studies achieved the optimum score of 100%, the lowest being 60%. Eight were deemed to have inappropriate exclusions and consequently high-risk of selection bias. Lack of clarity was also found regarding detection bias, with 11 studies failing to comment on blinding of assessors.

Findings

Of the studies included post-full-text review, three exclusively considered the TICS; six the modified TICS; two both the TICS and TICSm; seven the T-MMSE; one exclusively the T-MoCA; one the Tele-TYM. One study evaluated both the TICS and T-MoCA. 22

The tools were used to distinguish between a range of cognitive conditions. Four studies focussed on Mild Cognitive Impairment, nine on dementia (including Alzheimer's disease) and two considered both diagnoses. Five studies evaluated their use in detecting cognitive impairment post-stroke. One study examined unspecified cognitive impairment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al. 2009).

A mean of 144 individuals participated in each study, the majority recording a mean participant age between 70–75 years old. Female participation was higher than male, and there was high variability in years of education. These three variables are considered confounders, with elderly female uneducated patients being most at-risk of dementia. 42 Patients were recruited from several settings, nine studies enrolling patients from existing research, nine from hospital clinics and three using advertisements. The method for dementia diagnosis also varied. The majority used a well-established standard, such as The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), or a neuropsychological testing battery. However, a small proportion referenced tests such as the MMSE as a ‘gold standard’, despite more limited accuracy. Follow-up time between screening and diagnostic tests varied, with the maximum falling at six-weeks and the minimum being the same-day; the majority (13 studies) occurred within a fortnight.

Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)

There is high variation between the six studies’ optimal cut-offs for dementia and MCI screening. For example three studies thresholds for dementia were 24/25, 25 28, 29 and 33. 30 The extent of this discrepancy is witnessed through Seo et al.'s cut-off for MCI (28/29), 25 being less than Konagaya et al.'s dementia threshold of 33, 30 despite lower scores indicating greater severity. This may be explained through differences in educational level, Konagaya et al.'s dementia sample having a mean education level >11 years - over double Seo et al.'s group.25,30 It is understood that highly educated individuals perform better on cognitive assessments, and resultantly cut-off scores need not be as extreme.

The TICS has been considered for identifying post-stroke MCI and dementia. Zietemann et al. reported a cut-off of 36 most appropriate for MCI detection post-stroke; 22 with a corresponding specificity of 0.61 and PPV of 0.34, resulting in a high false-positive rate. In contrast, Barber & Stott and Desmond et al. used cut-off values of 28 and 25 respectively for dementia post-stroke.33,39 Sensitivity was 0.88 and 1.00, and specificity 0.85 and 0.83 respectively. Desmond et al.'s ‘perfect’ sensitivity score exceeds the in-person MMSE result of 0.83, 33 however the latter test has a better specificity and thus lower proportion of false-positive results.

Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICSm)

A modified 50-point version of the TICSm was examined by Cook et al. and Seo et al. which found,25,27 at thresholds of 34 and 28/9, sensitivities of 82.4% and 73.3% respectively for identifying MCI. Similarly to above, Cook et al.'s mean years of education doubled Seo et al.'s study,25,27 and again the thresholds are lower for Seo et al.

Other modified versions of the TICS have been examined. Baccaro et al., 28 maximum score of 39, considered validity of the TICSm in screening for unspecified cognitive impairment post-stroke. Using in-person MMSE as the reference standard the AUC was 0.89. In contrast, Vercambre et al., 32 maximum score of 43, using the same reference standard, reported the TICSm outperformed the MMSE for MCI, probable and possible dementia screening with an AUC of 0.83 and 0.72 respectively.

Telephone Mini-Mental State Examination (T-MMSE)

There are two versions of the MMSE, the 26-point T-MMSE and the 22-point telephone Adult Lifestyles and Function Interview MMSE (ALFI-MMSE). The difference is the addition of a three-step instruction and recall of the patient's telephone number in the 26-point version. 31

Naharci et al. and Wong et al. both examined the 26 point T-MMSE as a means of screening for Alzheimer's disease,21,26 reporting high sensitivities of 96.8% and 100% respectively.

The correlation between overall T-MMSE and in-person MMSE scores is significant, exceeding 0.85 in most studies, except Kennedy et al.'s moderate correlation of 0.688 (p < 0.001) in the 22 common questions. 40 Looking less broadly, agreeability between remote and in-person assessments, comparing Kappa Coefficients, also varied considerably in the answers to specific test questions. For the ‘recall of apple’ test, a similar agreeability between the three studies of fair to moderate was recorded, with Kappa Coefficient ranging from <0.4 to 0.480.3140 However, in other domains there was high inter-study variation. For example, the ‘orientation - season’ question Kappa scores were fair (<0.4), 31 substantial (0.770), 26 and excellent (0.924). 40 Poor agreement between in-person and telephone scores may indicate administrative or comprehensive problems with some questions.

Telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA)

Two papers examined the T-MoCA, both acknowledging its validity in identifying cognitive impairment post-stroke. They used alternative scoring systems, Wong et al. used a 5-min protocol consisting of 4 subtests rather than the longer 8 subtest tool utilised by Zietemann et al.22,35 Zietemann et al.'s study encompassed participants from the ‘Determinants of Dementia After Stroke’ (DEDMAS) study and Wong et al. ‘Stroke Registry Investigating Cognitive Decline’ (STRIDE) participants.22,35 The reported AUCs for identifying cognitive impairment post-stroke were excellent at 0.82 for MCI screening in Zietemann et al.'s study and acceptable at 0.78 for unspecified cognitive impairment in Wong et al.'s study.22,35

Telephone – Test – Your – Memory (Tele-TYM)

Brown et al. considered a telephone version of the TYM cognitive test. 24 This is likely due to the self-administrative basis of the Test-Your-Memory screen, requiring patients to complete 10 written tasks on a double-sided worksheet, which arguably may not require telephone input. At the optimal cut-off point a sensitivity of 0.78 is achieved meaning 22% of patients with cognitive impairment are uncaptured by this screening technique.

Discussion

Remote screening for dementia or cognitive impairment is established, with approximately twenty cognitive telephone tests available in clinical settings. 43 Telephone screening is considered useful for triage to Memory Assessment Services, particularly for people with access problems due to mobility problems or geographical isolation. This became important during the COVID pandemic to reduce disease transmission.

This review focusses on five tools deemed appropriate for dementia screening in the community, and is the first to consider these assessments in parallel.

Several studies compared the validity of telephone and in-person testing to determine if mode of administration influenced accuracy. Vercambre et al. reported a better AUC for the TICSm than the in-person MMSE. 32 In comparison, Seo et al. found no significant difference in validity for the TICS and TICSm compared to the MMSE, 25 achieving outstanding AUC for dementia screening of >0.9 for each test. This is supported by Dal Forno et al. who, despite finding a greater AUC for the MMSE than the TICS, found no significant difference in accuracy. 29 Similarities in AUCs of telephone and in-person assessments are common within literature, indicating these methods may be used interchangeably without compromising accuracy.

There is disagreement regarding whether patients perform better in-person or over the telephone. Newkirk et al. found participants had better MMSE scores by telephone, 31 with Roccaforte et al. concluding the converse. 36 In both these studies, higher scores were on subsequent tests, and thus learning-effects bias through repetition may be responsible. More recently, Camozzato et al. tested this theory in a Brazilian community sample by randomising the procedural order, finding in-person MMSE performance better. 23

Roccaforte et al. analysed potential differences in telephone and in-person MMSE scores by subdividing individuals based on clinical dementia rating (CDR) score. 36 They reported increasingly strong Pearson's correlation coefficients with greater impairment, between telephone and in-person administration. For example, at a CDR score of 0 (normal functioning) Pearson's r = 0.54, and a CDR of 2 (moderate dementia) r = 0.85. Wilson et al. also found differences associated with cognitive impairment severity. 44 A battery of seven telephone cognitive tests was administered to 495 people from 18 Alzheimer's disease centres across the United States. After accounting for confounders, the study found no difference in scores within the dementia group, but marginal overestimation in the cognitively healthy group, due to ‘working memory’ scores. However, this was responsible for less than 1% variation in overall scores. This overestimation was also found in a study exploring the TICSm in healthy individuals. 45

Hence, differences in the performance of telephone testing may be influenced by the setting and order of administration, in addition to cognitive status.

Optimal cut-off scores are not exclusively influenced by specific cognitive conditions, but also by population demographics, contextual setting and an institution's organisational structure. 46 A balance must be made between using high cut-offs and thus more false-positives (causing unnecessary distress, patient harm and financial burden), or low cut-offs with more false-negatives (resulting in under-diagnosis with subsequently more severe presentations).

Hearing impairment is of consideration when determining whether allowances in telephone screening cut-off scores should be made, especially where comprehensive issues could usually be gauged through physical cues in-person. Several studies considered whether hearing impairment negatively influences telephone scores, with no general consensus reached. Roccaforte et al. found with that these patients had significantly lower scores (p < 0.05), approximately one-point less, on the T-MMSE. 36 Naharci et al. similarly speculated that poorer cognitive performance on the Turkish version of the T-MMSE may have been due to auditory impairment. 21 However, when Graff-Radford et al. incorporated phonetically alike responses into the marking criteria there was no significant difference in the TICSm scores. 37 Thus, more evidence is required before concluding to what level, if at all, hearing impairment exacerbates or invalidates cognitive scores.

This review found no definitive hierarchy for the validity of telephone tools. Therefore, other factors such as training, completion time, and patient/ practitioner preferences should be gauged. Telephone assessment is double-edged in regard to patient accessibility. For example, necessity of travel may disadvantage those with mobility issues, but reliance on technological competency and hearing may be challenging for others. Therefore, the offer of telephone screening should be evaluated case-by-case.

Strengths and weaknesses

There were some methodological limitations. The order and timing of tests may influence results for example those studies with fewer than 72 hours between index and reference standard,23,39 risk participant learning-effect bias through memorisation of repeated questions. Of the 21 studies included for qualitative analysis, 15 failed to mention or apply blinding of assessors,22,24–26,28–31,33,35,36,38–41 risking detection bias. Harsh exclusion criteria (e.g. Lines et al. excluded those taking certain hormone therapies), 41 and those conducted in one region/ setting, limited generalisability to wider screening. The international coverage of this review meant there were cultural/ language modifications. All studies were conducted within secondary care settings (with high prevalence of cognitive impairment), for example Memory Assessment Services. This limits applicability to General Practice populations (with lower prevalence of cognitive impairment) but where most screening is conducted.

Home assessments are not standardised, which risks participants ‘cheating’ (e.g. by writing down questions), albeit unintentionally, and thus more false-negative results. Several studies excluded people with hearing problems and language barriers, where telephone consulting is challenging. 47 Lack of in-person contact risks some cognitive domains being unmeasured, such as motor skills, meaning some dementia subtypes, such as Parkinsonian dementia, are not effectively recorded.

The exclusion criteria narrowed the volume of data, in particular the six-week time limit. This decision could have disproportionally impacted larger studies where shorter timescales are unfeasible, such as Manly et al.'s study which breached the six-week criteria but was otherwise strong. 48 However, its inclusion would not have changed the conclusion that the TICS appears valid for dementia screening.

Strengths of the review include a standardised search strategy for a range of electronic databases, facilitating reproducibility and accessing a wide scope of material. All papers used for qualitative analysis post-full-screen review were quality assessed, using pre-defined criteria, modelled from reputable Joanna Briggs Institute tools.19,20 Therefore, individual study bias could be determined enabling contextualisation in analysis of results. Cross-validation was conducted by a second or third author at each stage of exclusion, preventing selection bias.

Conclusion

Telephone screening for MCI and dementia appears useful in clinical practice in combination with subsequent diagnostic tests. Compared to existing in-person screening tools, telephone cognitive assessments perform well, with similar validities. Neither modality appears superior at a population level; however, suitability must be considered individually.

Most patients with dementia and cognitive impairment present in family practice and following screening are referred to specialist services. More quantitative research is required, looking at screening accuracy that focuses exclusively on this setting using larger sample sizes, with lower prevalence. Moreover, as patients often present to general practice with milder cognitive impairment, tools that can detect and distinguish these from dementia are important.

Appendix A: Search strategy

| Step in strategy | Search Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | TITLE(Dement* OR “cognitive disorder” OR “cognitive impairment” OR Alzheimer*) |

| 2 | ABSTRACT/TOPIC/TITLE(tele* OR remote OR phone OR virtual) |

| 3 | ABSTRACT/TOPIC/TITLE(TICS OR “telephone interview for cognitive status” OR “MMSE” OR “T-MMSE” OR “mini-mental state exam*” OR “MoCA” OR “T-MoCA” OR “Montreal cognitive” OR “test* batter*” OR TYM OR “test your memory”) |

| 4 | ABSTRACT/TOPIC/TITLE(“virtual reality” OR game OR monitor* OR rehab) |

| 5 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 |

| 6 | 5 NOT 4 |

| 7 | LIMIT 6 TO ENGLISH LANGUAGE |

Appendix B: JBI tool

Assessment of risk of bias – JBI tool modified

- 1. Selection bias

- Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled?

- Consecutive and random sampling are least likely to cause selection bias, studies should record their method of recruitment. This is inclusive of using advertisements whereby the patient then enrols themselves, contacting patients from a pool of participants in an ongoing/ previous study, or including all patients attending a clinic between two stated dates.

- Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions?

- Inclusion/ exclusion criteria should be clearly stated, studies failing to meet this will be marked as unclear. Exclusion criteria are deemed acceptable only where there is cognitive impairment of an alternative aetiology for example brain tumour, an inability to communicate for example aphasia, incomplete data, or there is another factor that compromises testing procedures for example lack of a reliable informant if necessary.

- 2. Confounders

- Were confounding factors stated?

- Confounders include age, education, gender, and hearing impairment as these variables impact on telephone cognitive screening scores. At least one of these confounders should be mentioned with reference to baseline characteristics.

- Were strategies to deal with confounders stated?

- Confounders can be dealt with through design of studies and in statistical analysis. If there are two groups then confounders can be matched at baseline, statistical tests can also be performed to measure if there is a significant difference between the groups. Regression analysis is another tool for dealing with confounders through measurement of association.

- 3. Test accuracy

- Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target conditions?

- Ideally the reference standard should be considered a ‘gold standard’ or meet established criteria such as DSM, but if not then it should be a reputable tool with high accuracy in determining cognitive diagnoses.

- Was there an appropriate interval between the index and reference standard?

- The index and reference standard should be completed by a minimum of 95% of the participants within a timeframe of six-weeks. This is to prevent significant cognitive deterioration between index and reference standard which would render the tests incomparable.

- Did all the patients receive the same reference standard?

- All patients should receive the same reference standard which is used for the comparison with the telephone screening test.

- 4. Performance/ detection bias

- Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of results of the reference standard?

- Generally, it is not feasible to blind patients to their diagnosis of cognitive impairment. To minimise detection bias assessors should be blinded to confirmed diagnoses or patient cognitive test scores. Where blinding is not mentioned studies should be marked as unclear.

- Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test?

- Generally, it is not feasible to blind patients to their diagnosis of cognitive impairment. To minimise detection bias assessors should be blinded to confirmed diagnoses or patient cognitive test scores. Where blinding is not mentioned studies should be marked as unclear.

- 5. Attrition bias

- Were all patients included in the analysis?

- Loss to follow-up should be explained, with statistical measures completed to determine impact if >20% of the participants, post first cognitive test, withdraw as this threatens validity. Where studies are vague about losses, or only give partial reasoning, mark as unclear.

Appendix C: Excluded studies

Characteristics of excluded studies post full-text review (ordered by first author and date)

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baker et al. 49 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. Absence of cognitive diagnosis with no comparison to a face-to-face assessment tool. |

| Beeri et al. 50 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

| Benge & Kiselica 11 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

| Bentvelzen et al. 51 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Crooks et al. 52 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

| de Jager et al. 53 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. Absence of cognitive diagnosis |

| Gallo & Breitner 54 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

| Järvenpää et al. 9 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Kiddoe et al. 55 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

| Knopman et al. 56 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Lacruz et al. 57 | No comparison to a face-to-face assessment |

| Lindgren et al. 58 | Absence of cognitive diagnosis with no comparison to a face-to-face assessment tool. Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

| Lipton et al. 59 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Manly et al. 48 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Muñoz-García et al. 60 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Pendlebury et al. 61 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Rankin et al. 62 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments Absence of cognitive diagnosis |

| Welsh et al. 63 | More than a six-week time interval between in-person and telephone assessments |

| Yaari et al. 64 | Study did not record a time interval between in-person and telephone assessments. |

Appendix D: Data Extraction Table

| Study: Author (date) | Sample size | Exclusion/ Inclusion criteria | Sample Characteristics | Screening tool | Diagnostic tool | Interval between tests | Major findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) and modified versions (TICSm) | ||||||||

| Zietemann et al. 22 | 105 | Inclusion:

|

From the DEDEMAS study (Determinants of Dementia After Stroke) Mean age (years) = 69.4 (±9.0) Female (%) = 31.4 <12 years of education (%) = 36.2 |

TICS (maximum score 41) | Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Comprehensive Neuropsychological Testing (CNT) – 18 cognitive tests |

2 weeks | Optimum cut off for diagnosis of MCI post-stroke is at <36. At this cut-off using CNT as the reference standard, sensitivity = 73%; specificity = 61%; PPV = 34%, NPV = 89% Educational or mood disorder adjustments do not significantly influence AUC; justification for not adding on points for these patient groups AUC for any MCI using CNT as the reference standard = 0.76 (95% CI 0.63–0.88) AUC for any MCI using CDR as the reference standard = 0.78 (95% CI 0.64–0.93) Considered a valid screening tool but should not be used alone for diagnosis |

Small sample size Highly educated participants, with only 31.4% female may not be representative of the true population Harsh exclusion criteria: acute neurological stroke within 5 days, available informant No blinding mentioned |

| Dal Forno et al. 29 | 109 | Inclusion:

|

Recruited outpatients with suspected cognitive impairment undergoing neurological and neuro-psychological evaluation at the University Campus BioMedico Dementia Research Clinic between 2002 and 2004. Controls were cognitively healthy demographically matched individuals. Alzheimer's group (N = 45): Mean age (years) = 73.9 (± 8.8) Mean years of education = 7.9 (± 3.9) Female (%) = 62 Controls (N = 64): Mean age (years) = 74.4 (± 8.1) Mean years of education = 7.5 (± 4.2) Female (%) = 64 |

TICS (maximum score 41) Italian adaptation |

All groups: MMSE, NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's group: Physical and neurological examination Laboratory testing to exclude treatable causes of dementia Neuroimaging (CT/MRI) Electro-encephalography Complete battery of neuropsychological tests – MMSE, 15 word Rey verbal learning test, Prose recall, Digit span (WAIS-R), Corsi test, Raven's progressive matrices 47, Phonological and semantic word fluency, Attentional matrices, Test for constructional apraxia Geriatric Depression Scale Control group: Clinical interview on medical and neurological history Additional information obtained by relative or spouse |

Less than 6 weeks | Optimum cut-off score was 28 for Alzheimer's disease screening (sensitivity = 84%; specificity = 86%) The TICS correlates highly with the MMSE, with Pearson's r = 0.904 AUC of the TICS according to NINCDS-ADRDA diagnosis = 0.894 (95% CI, 0.831–0.957) Internal consistency is high with Cronbach's alpha = 0.91 Each month a decrease in 0.35 points could be expected (t = 2.664 p = 0.018) in AD patients. |

Small sample size No confounder examination, for example regression analysis Loss to follow-up not explained Excluded all other dementia types except Alzheimer's disease No medical examination on the control group – cannot fully conclude they are cognitively ‘healthy’ Unclear if blinding occurred |

| Konagaya et al. 30 | 135 | Inclusion:

|

Patients with Alzheimer's were recruited from the memory clinic of the National Hospital for geriatric medicine, the control group being urban residents Alzheimer's group (N = 49): Mean age (years) = 75.2 (± 6.8) Mean years of education = 11.0 (± 3.0) Female (%) = 61 Control group (N = 86): Mean age (years) = 74.3 (± 7.2) Mean years of education = 11.4 (± 2.2) Female (%) = 83 |

TICS (maximum score 41) Japanese adaptation |

All groups: MMSE and category fluency test Alzheimer's group: Diagnosis based on DSM-IV and NINCDS-ADRDA General Medical examination Neurological examination Laboratory tests MRI SPECT Neuropsychological examination |

2 weeks | Optimal cut off for distinguishing between Alzheimer's and healthy individuals is 33 (sensitivity 98.0%; specificity 90.7%) The mean testing time for Alzheimer's disease patients was significantly longer (473.1 s ± 121.9) compared to the controls (328.8 s ± 60.4) p < 0.001 Area under the curve for the TICS was 98.7% Test re-test reliability using ICC = 0.946 |

Same interviewer used for both face-to-face and telephone testing – no blinding Risk of selection bias as patients not randomly or consecutively recruited No limitations noted by the authors risks bias in presentation of results Well educated subjects with active social life, limits generalisability Control group did not receive battery of tests, cognitive impairment cannot be truly ruled out Gender of participants significantly different between the two groups (p < 0.001) |

| Desmond et al. 33 | 72 | Not mentioned | Stroke group (N = 36): Mean age (years) = 72.3 (± 8.9) Mean years of education = 9.7 (± 4.7) Female (%) = 61.1 White (%) = 25 Primary language English (%) = 58.3 Control group (N = 36): Mean age (years) = 71.8 (± 6.8) Mean years of education = 13.1 (± 4.1) Female (%) = 75 White (%) = 66.7 Primary language English (%) = 83.3 |

TICS (maximum score 41) English or Spanish version |

Neuropsychological and functional assessment MMSE |

1 week | At a cut-off of <25 for diagnosing dementia after stroke the TICS sensitivity = 100%; specificity = 83%, in comparison to the MMSE sensitivity = 83%; specificity = 87% Only a moderate correlation between the TICS and MMSE in the control sample (r = 0.44, p = 0.008). High correlation in the stroke patients (r = 0.86, p < 0.001) |

Significant difference between education, race and primary language between the two groups Small sample size No clear exclusion/ inclusion criteria – limits comparability No blinding mentioned Highly educated patients limits generalisability Correlation in the control sample only moderate – likely due to a ceiling effect |

| Barber & Stott 39 | 64 | Inclusion: • Suffered from an acute stroke (meeting the WHO definition) within the past six months Exclusion • Unable to complete the AMT for reasons of dysphasia or deafness • Refused to give written, informed consent | Stroke outpatients from the Cerebro Vascular Clinic or Geriatric Day Hospital Median age (years) = 72 (range 63-80) Time from stroke onset to assessment (days) = 118 (range 84–142) |

TICS (maximum score 41) & TICSm (maximum score 50) | R-CAMOG (cut off 33) Geriatric Depression Scale Rankin Scale Abbreviated Mental Test Score |

Same day | Using the R-CAMCOG cut off of 33, the Area Under the Curve for the TICS & TICSm = 0.94 for identifying post-stroke dementia Optimal cut off for the TICS in screening for post-stroke dementia is at 28 (sensitivity = 88%; specificity = 85%), and for the TICSm is 20 (sensitivity = 92%; specificity = 80%) The R-CAMCOG and TICS/ TICSm scores are highly correlated, with Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.833 (95% CI 0.74–0.90) for the TICS and 0.855 (95% CI 0.77–0.91) for the TICSm. |

Small sample size Half of the subjects were from a Geriatric Day Hospital – potentially frail, elderly, with higher risk of cognitive impairment Very few patients with severe cognitive impairment R-CAMCOG used as a gold standard (sensitivity = 91%; specificity = 90%, at cut off 33), limited diagnostic quality No regression analysis performed for confounders, nor confounders such as sex stated Not blinded and only one observer used – high risk of detection bias Tests performed on the same day, risk of learning effects bias with similar questions, attempt was made to counteract this by randomising the order |

| Seo et al. 25 | 230 | Inclusion:

|

From a pool of geriatric patients registered in a nationwide programme for early detection and management of dementia in Seoul and six provinces Mild Cognitive Impairment group (N = 75): Mean age (years) = 73.39 (± 5.75) Mean years of education = 6.79 (±4.33) Female (%) = 56.0 aMCI (%) = 81.3 Dementia group (N = 85): Mean age (years) = 75.00 (± 6.57) Mean years of education = 5.23 (±4.44) Female (%) = 60.0 Possible Alzheimer's disease (%) = 75.3 Cognitively normal group (N = 70): Mean age (years) = 70.03 (± 5.17) Mean years of education = 8.09 (±4.61) Female (%) = 58.6 |

TICS (maximum score 41) & TICSm (maximum score 50) Korean adaptation |

DSM-IV CERAD clinical assessment battery - CDR, blessed dementia scale activities of daily living, Short blessed test, General Medical examination, neurological examination, laboratory tests, MRI, CT Cognitive impairment assessments: word list memory, word list regal, word list recognition, constructional recall, verbal fluency, 15 item Boston naming test, constructional praxis. |

4 weeks | Optimal cut-off for cognitively normal vs dementia for the TICS is 24/25 (sensitivity = 87.1%; specificity = 90.0%) & for the TICSm is 23/24 (sensitivity = 88.2%; specificity = 90.0%) Optimal cut-off for cognitively normal vs MCI for the TICS is 28/29 (sensitivity = 69.3%; specificity = 68.6%) & for the TICSm is 28/29 (sensitivity = 73.3%; specificity = 67.1%) Optimal cut-off for MCI vs dementia for the TICS is 21/22 (sensitivity = 75.3%; specificity = 81.3%) & for the TICSm is 20/21 (sensitivity = 75.3%; specificity = 78.7%) No significant difference in the accuracy of dementia discrimination between the TICS and TICSm. Considered as valid as the MMSE for cognitive impairment screening Both the TICS and TICSm demonstrated excellent test re-test reliability with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.95 (p < 0.001), and high internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 |

Blinding not mentioned |

| Cook et al. 27 | 71 | Inclusion:

|

Non-MCI (N = 54): Mean age (years) = 74.3 (± 5.0) Mean years of education = 16.1 (± 2.6) Female (%) = 64.8 White (%) = 92.6 aMCI (N = 17): Mean age (years) = 77.0 (± 7.4) Mean years of education = 16.29 (± 3.1) Female (%) = 29.4 White (%) = 94.1 |

TICSm (maximum score 50) | Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Neuropsychological battery - Hopkins verbal learning test revised. Rivermead behavioural memory test paragraph. Recall subtest. Brief visuospatial memory test. MMSE North American Adult reading test. Boston naming test. Controlled oral word association test. Trailmaking tests part A and B. Everyday problems test. GDS. Center for epidemiological studies depression scale. Memory functioning questionnaire |

2 weeks | Optimal cut-off score for detecting amnestic MCI is at 33/34 (sensitivity = 82.4%; specificity 87.0%; PPV = 66.7%; NPV = 94.0%) At a cut-off of 33/34 the AUC is 93.3% + SE 3.2% Splitting the sample into two groups based on those over and under 75 years old found that younger patients (<75) should have a higher cut off (36) than older (>75) patients (33) in detecting aMCI |

Small sample size Harsh exclusion criteria – risk of selection bias Highly educated sample which may not be generalisable Lack of medical or neurological examination to rule out other causes of memory impairment Levels of hearing issues in the sample not recorded, this affects ability to understand telephone test questions Significant difference between sex of the two groups p = 0.01 |

| Baccaro et al. 28 | 61 | Inclusion:

|

Recruited from the Stroke mortality and morbidity study (EMMA study) Cognitive impairment (N = 14): Mean age (years) = 69.6 (± 10.5) Female (%) = 57.1 Education ≥ 11 years (%) = 21.4 White (%) = 35.7 No cognitive impairment (N = 47): Mean age (years) = 59.7 (± 11.9) Female (%) = 29.8 Education ≥ 11 years (%) = 23.4 White (%) = 46.8 |

TICSm (maximum score 39) Brazilian – Portuguese translation |

MMSE HDRS scale for depressive symptoms Rankin scale for functional disability |

Two tests at 1 and 2 weeks | Optimal cut-off point for screening for cognitive impairment post-stroke in comparison to the MMSE was 14/15 points (sensitivity = 91.5%; specificity = 71.4%) The AUC for the TICSm in detecting cognitive impairment post-stroke compared to the MMSE is 0.89 (95% CI 0.80–0.98) High internal consistency between scores, Cronbach alpha = 0.96 |

Small sample size Unclear if blinding occurred Loss to follow-up not clearly explained MMSE used as a ‘gold standard’ despite being limited in its diagnostic accuracy Stroke severity not evaluated using National Stroke Association NIH stroke scale Educational level statistically significantly different between the two groups (p < 0.001) |

| Vercambre et al. 32 | 120 | Inclusion

|

Participating in the etude epidemiologique de femmes de l’education nationale Cognitively normal (N = 92): Percentage of participants <80yrs (%) = 68 Percentage of participants with less than 12 years of education (%) = 17 Mild cognitive impairment (N = 18): baseline information not mentioned Possible/ probable dementia (N = 10): baseline information not mentioned |

TICSm (maximum score 43) French version |

Neuropsychological examination - MMSE, FCSRT, Trailmaking test A and B, Clock drawing test, IADL, GDS, French picture naming test, Wechsler adult intelligence scale III | 2 weeks | No optimal cut off stated for identifying cognitive impairment. At a cut-off of 30 (sensitivity = 68%; specificity = 89%) and at a cut-off of 33 (sensitivity = 86%; specificity = 60%) TICSm outperformed the TICS and MMSE with higher sensitivity and specificity values for the majority of cut-off scores for cognitive impairment screening Satisfactory internal consistency for the TICSm, Cronbach's alpha = 0.69 Area under the curve of the TICSm compared to the gold standard classification was 0.83, this was higher than the TICS (0.78) and MMSE (0.72) |

Small sample size Women only and highly educated limits generalisability Low response and completion rate Low prevalence of cognitive impairment |

| Graff-Radford et al. 37 | 128 | Inclusion:

|

MCI group (N = 8): Median age (years) = 86 (range 80-92) Median years of education = 16 (range 12-19) Female (%) = 50 Cognitively normal (N = 120): Median age (years) = 86 (range 76-98) Median years of education = 13 (range 6-20) Female (%) = 55 50% of participants had trouble hearing, 36% use a hearing aid, and 58% reported problems with hearing on the telephone test |

TICSm (maximum score 50) | NINCDS-ADRDA criteria WRAT-3 reading Free and Cued selective reminding test Logical memory I and II Boston naming test Controlled oral word association test Category fluency test Trail making tests parts A and B Digit span Block design |

4 weeks | The ability of the TICSm to identify cognitively normal patients compared to healthy individuals is best at a cut-off of <31 (sensitivity = 68%; specificity = 75%; PPV = 98%; NPV = 13%) Hearing impairment was not an obstacle to administering the telephone screening tools (with 58% admitting hearing difficulties), as inclusion of phonetically similar responses on the delayed recall did not alter TICSm overall scores |

Small sample size Harsh exclusion criteria of variables that do not impact cognitive functioning for example those without a sibling No strategies to deal with confounders noted, or statistical comparison of baseline characteristics Used for identifying people for a clinical trial and therefore is limited in its real world applicability for aMCI screening |

| Duff et al. 38 | 123 | Inclusion:

|

Community dwelling individuals aMCI group (N = 61): Mean age (years) = 82.43 (± 6.43) Mean years of education = 15.34 (± 2.82) Female (%) = 78.6 Control group (N = 62): Mean age (years) = 77.18 (± 7.80) Mean years of education = 15.45 (± 2.57) Female (%) = 80.6 |

TICSm (maximum score 50) | Brief clinical interview Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) form A Wide Range Achievement Test-3 (WRAT-3) Geriatric Depression Scale Symbol digit modalities test Hopkins verbal learning test revised Brief visuospatial memory test-revised (BVMT-R) Controlled oral word association test Animal fluency Modified MMSE spatial and temporal items Trailmaking test parts A and B |

1-3 weeks | Mean difference in the scores of the aMCI and control groups had a large effect size, with Cohen's d >0.8 Memory factor best discriminates between aMCI and healthy subjects (immediate/ delayed recall and serial 7's tests on the TICSm most effective) |

Small sample Age is significantly different between the aMCI and control groups Excluded those with more severe cognitive impairment (≥19) Exclusively Caucasian – limits generalisability No neuroimaging ot lab work for diagnosis, can't fully exclude other aetiologies for impairment or that the control group is truly ‘healthy’ Blinding not mentioned – risk of detection bias |

| Lines et al. 41 | 676 | Inclusion

|

Patients taking part in the PRAISE study aMCI group (N = 324): Mean Age (years) = 76 (range 64-93) Female (%) = 33 Family history of Alzheimer's disease (%) = 25 Non-aMCI group (N = 352): Mean Age (years) = 74 (range 64-90) Female (%) = 44 Family history of Alzheimer's disease (%) = 25 |

TICSm (maximum score 50) | Category fluency test MMSE RAVLT Clinical Dementia Rating Blessed Dementia Rating Scale |

Within 6 weeks | Memory score is most significant (p < 0.05) in clinical determination of aMCI, with the delayed recall section being most discriminative |

For identifying patients for inclusion in a trial so not necessarily generalisable to a clinical screening Harsh exclusion criteria from the PRAISE study limited sample size Blinding not mentioned |

| Telephone Mini-Mental State Examination (T-MMSE) | ||||||||

| Naharci et al. 21 | 104 | Inclusion:

|

Recruited people visiting the Geriatric Outpatient Clinic of the University of Health Sciences in Ankara Alzheimer's disease group (N = 63): Mean age (years) = 81.2 (± 6.0) Mean years of education = 5.6 (± 4.2) Female (%) = 60.3 Hearing aid use (%) = 20.6 Control group (N = 41): Mean age (years) = 75.2 (± 6.3) Mean years of education = 6.6 (± 3.9) Female (%) = 68.3 Hearing aid use (%) = 4.9 |

T-CogS (Turkish adaptation of the 26 point ALFI-MMSE) | DSM-V and National Institute On Ageing And The Alzheimer's Association Criteria Neuropsychological tests - MMSE, clock drawing test, Clinician Dementia Rating, Instrumental Activities Of Daily Living, Clinical history Brain imaging CDR score of 1 or 2 MMSE score between 10-23 GDS score <6 |

3 days | Optimal cut-off of 22 given for detecting Alzheimer's disease vs controls (sensitivity = 96.8%; specificity = 90.2%; PPV = 93.9%, NPV = 94.9%) Internal consistency in scoring was acceptable, with a Cronbach's alpha score os 0.763 Test-retest reliability conducted 4 weeks after the initial telephone call was excellent with a value of 0.990 (95% CI 0.985-0.993) |

Small sample size Significant differences in age and hearing aid use between control and Alzheimer's disease groups, with these variables being greater in the latter group Unclear whether the recruitment of patients was consecutive or selective Harsh exclusion critera |

| Camozzato et al. 23 | 133 | Inclusion:

|

Community sample from a Southern Brazilian City Alzheimer's disease group (N = 66): Mean age (years) = 73.9 Mean years of education = 5.00 Female (%) = 54.5 Control group (N = 67): Mean age (years) = 71.4 Mean years of education = 5.28 Female (%) = 64.2 |

Braztel-MMSE (Brazilian version of the T-MMSE, maximum score 22) | NINCDS-ADRDA criteria used for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis Blessed information memory concentration test Clinical Dementia Rating Those with CDR 0.5, performed below expectation on testing and had a history consistent with AD were referred for neuroimaging and blood tests |

2-3 days | Optimal cut-off for distinguishing between healthy controls and Alzheimer's patients is 15 (sensitivity = 95%; specificity = 84%; PPV = 85%; NPV = 93%) T-MMSE strongly correlated with the MMSE (r = 0.92, p = 0.01) Test-retest reliability for the T-MMSE was strong r = 0.92 Participants performed slightly better on the in-person MMSE- this may be due to better capability in answering questions, familiarity with consultation style, visual clues |

Sample population of low educational level, which impacts cognitive test scoring and may limit generalisability No reasoning for loss to follow-up given Excluded those with hearing complaints or severe dementia |

| Wong & Fong 26 | 65 | Inclusion:

|

Recruited from an acute regional hospital in Hong Kong Dementia group (N = 34): Mean age (years) = 74.1 (±7.2) Mean years of education = 3.1 (±3.5) Female (%) = 61.8 Control group (N = 31): Mean age (years) = 81.2 (±7.0) Mean years of education = 1.8 (±2.9) Female (%) = 58.1 |

T-CMMSE (Cantonese version of the MMSE, maximum score 26) | Diagnosed according to DSM-IV CMMSE |

1 week | Optimal cut-off for the T-MMSE in screening for dementia is 16 (sensitivity = 100%; specificity = 96.7%) Strong correlation between the in-person MMSE and the T-MMSE, with Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.991 (p < 0.001) High inter- and intra-rater reliability, with an ICC of 0.99 |

Small sample size Statistically significant difference between the ages of individuals in the two groups Very low number of patients with severe dementia Convenience sampling used which risks selection bias Principle investigator was one of the assessors, risk of detection bias, this is further amplified through lack of blinding of assessors |

| Newkirk et al. 31 | 46 | Inclusion:

|

Recruited from Stanford / VA Alzheimer's Center Mean age (years) = 76.5 Percentage of individuals with >12 years education (%) = 71.7 Female (%) = 52.2 White (%) = 87.0 More than a third of participants reported hearing impairment |

T-MMSE (maximum 26 points) | NINCDS-ADRDA criteria MMSE |

Within 35 days | TMMSE correlated strongly with the MMSE (r = 0.88 p < 0.001) for total scores in the Alzheimer's disease patients Participants performed slightly better on the telephone version Hearing impairment and level of education did not significantly affect telephone score. More than one third of patients reported hearing difficulties. Substantial agreement in the scoring of the MMSE and T-MMSE for the categories year, month, name watch, with a kappa coefficient of 0.61-0.8 |

Small sample size No blinding, assessor “familiar with patient” Mainly a white, highly educated cohort, limits generalisability Loss to follow-up lacks explanation |

| Metitieri et al. 34 | 104 | Exclusion:

|

Recruited from the Alzheimer's unit at the IRCCS San Giovanni de Dio Mean age (years) = 77.2 (±8.1) Mean years of education = 5.2 (±2.3) Female (%) = 76 Probable Alzheimer's disease = 50%, vascular dementia = 25% |

Itel-MMSE (Italian version of the T-MMSE, maximum score 22) | Known diagnosis Clinical Dementia Rating MMSE |

1 week | Inter-rater reliability high = 0.82–0.90 High test re-test reliability = 0.90-0.95 |

Small sample size Inpatients which limits generalisability Study failed to record any of its own limitations, bias in presentation of findings All Alzheimer's disease patients, no cognitively healthy participants |

| Roccaforte et al. 36 | 100 | Inclusion:

|

Recruited by attendance to the University of Nebraska Geriatric Assessment centre Mean age (years) = 79 Mean years of education = 11.5 Female (%) = 76 White (%) = 95 Approximately 50% of participants experienced hearing difficulties |

ALFI-MMSE (maximum 22 points) | DSMIII Clinical Dementia Rating Extensive history Physical examination Pertinent laboratory and radiologic studies Completion of cognitive status, functional status and mood measures MMSE Brief neuropsychological screening test (BNPS) - Trail making A, word fluency, Wechsler memory scale mental control and logical memory |

Mean of 8.7 days | No significant differences in the scores of the 22 items of the in-person and T-MMSE, with a trend towards higher in-clinic scores Relative to the brief neuropsychological screening test the ALFI-MMSE had a sensitivity = 67%; specificity = 100%, compared to the in-person MMSE with a sensitivity = 68%; specificity = 100% Strong correlation in scores between the same 22 questions on the telephone and in-person MMSE (r = 0.85, p < 0.0001) Lower score for the ALFI-MMSE compared to the in-person MMSE for the same 22 items (14.6 for the ALFI-MMSE and 15.1 for the MMSE) Hearing impairment patients reported significantly lower scores on the ALFI-MMSE |

Small sample size Low response rate (62%) No clear exclusion criteria noted Reason for participant loss not given Confounder strategy not stated Blinding not mentioned |

| Kennedy et al. 40 | 402 | Inclusion:

|

Participants of the University of Alabama Birmingham Study of Ageing II Mean age (years) = 81.6 (±4.8) Percentage of college graduates (%) = 10 Female (%) = 58 Caucasian (%) = 65 |

T-MMSE (maximum 22 points) | Diagnosis in medical records/ patient has been told they have dementia MMSE Six item screen Instrumental activities of daily living |

(95%) within 6 weeks | For the 22 common questions in the T-MMSE and the MMSE there was 0.688 (p < 0.001) correlation in scores The Area Under the Curve for the T-MMSE in classifying dementia was 0.73 Higher internal consistency for the telephone version compared to the in-person MMSE, with Cronbach alpha scores of 0.845 and 0.763 respectively |

Process of identifying dementia may lead to under-reporting (especially in milder forms) Very small proportion of participants have a dementia diagnosis Limited variation in race – Caucasians and African Americans Blinding not mentioned |

| Telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment (T-MoCA) | ||||||||

| Zietemann et al. 22 | 105 | Inclusion:

|

From the DEDEMAS study (Determinants of Dementia After Stroke) Mean age (years) = 69.4 (±9.0) Female (%) = 31.4 <12 years of education (%) = 36.2 |

T-MoCA (maximum score 22) | Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Comprehensive Neuropsychological Testing (CNT) – 18 cognitive tests |

2 weeks | Optimum cut off for diagnosis of MCI post-stroke is at <19. At this cut-off using CNT as the reference standard, sensitivity = 81%; specificity = 73%; PPV = 45%, NPV = 94% Educational or mood disorder adjustments do not significantly influence AUC; justification for not adding on points for these patient groups AUC for any MCI using CNT as the reference standard = 0.82 (95% CI 0.71-0.94) AUC for any MCI using CDR as the reference standard = 0.73 (95% CI 0.59-0.87) Considered a valid screening tool but should not be used alone for diagnosis |

Small sample size Highly educated participants, with only 31.4% female may not be representative of the true population Harsh exclusion criteria No blinding mentioned |

| Wong et al. 35 | 104 | Inclusion:

|

Participants from the STRIDE study Cognitively impaired group (N = 51): Mean age (years) = 70.8 (±9.2) Mean years of education (years) = 6.0 (±4.5) Female (%) = 37 Cognitively normal group (N = 53): Mean age (years) = 68.9 (±10.1) Mean years of education (years) = 6.3 (±4.4) Female (%) = 51 |

T-MoCA 5 min protocol (maximum score 30) Cantonese version | MMSE Clinical Dementia Rating MoCA |

4 weeks | Scores were on average 1.8 points higher on the T-MoCA 5 min protocol than on the in-person MoCA The T-MoCA 5 min protocol Area Under the Curve was 0.78 compared to 0.74 for the in-person MoCA for assessing cognitive impairment after stroke The test-retest reliability was 0.89 (p < 0.001) for the T-MoCA, with an internal consistency measure using Cronbach's alpha of 0.79 |

Small sample size Participants had pre-exposure to MoCA and the order was not counter-balanced, risks learning effect bias No patients with severe dementia included Unclear whether blinding occurred From an existing study which has inclusion/ exclusion criteria that may not be generalisable to the whole patient population |

| Tele-Test-Your-Memory (Tele-TYM) | ||||||||

| Brown et al. 24 | 81 | Exclusion:

|

Recruited patients due to be seen at a specialised memory clinic Organic dementia/ MCI group (N = 38): Mean age (years) = 69.7 Subjective memory complaints group (N = 43): Mean age (years) = 60.5 |

Tele-TYM (maximum score 50) | Addenbrooke's cognitive examination (ACE-R) MMSE Imaging |

2 weeks | Optimal cut-off at ≥43 for screening for cognitive impairment (sensitivity = 78%; specificity = 69%) Strong correlation between scores of the telephone-TYM and in-person ACE-R, with r = 0.83 for organic cognitive impairment and r = 0.60 subjective memory complaints |

Unclear recruitment strategy Harsh exclusion criteria Unclear if blinding occurred, which risks detection bias Confounders not stated limits comparability between groups and reproducibility Failed to reflect on any limitations of the study |

Appendix E: List of abbreviations

- ACE

Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living

- ALFI-MMSE

Adult Lifestyles and Function Interview MMSE

- AMT

Abbreviated Mental Test

- aMCI

Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- CAMCOG

Cambridge Cognition Examination

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CERAD

The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease

- CNT

Comprehensive Neuropsychological Testing

- CT

Computed Tomography

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- FCSRT

Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test

- GDS

Geriatric Depression Scale

- HDRS

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- IADL

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- ICC

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

- LR

Likelihood Ratio

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- NINCDS-ADRDA

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- MCI

Mild Cognitive Impairment

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- PPV

Positive Predictive Value

- RAVLT

Rey's Auditory Verbal Learning Test

- SE

Standard Error

- SPECT

Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- Tele-TYM

Telephone Test-Your-Memory

- TIA

Transient Ischaemic Attack

- TICS

Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status

- TICSm

Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status

- WAIS

Wechsler Intelligence Scales

- WHO

World Health Organisation

- WRAT

Wide Range Achievement Test Reading

Footnotes

Declaration

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Charlotte Olivia Riley https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7655-178X

Brian McKinstry https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9581-0468

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Dementia. 2020. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/dementia/.

- 2.World Health Organisation. Dementia 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- 3.World Health Organisation. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017-2025. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487-eng.pdf;jsessionid=D684D2A563E5DD2D50C71D1E36C570CE?sequence=1.

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. NICE impact dementia . 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/Into-practice/measuring-uptake/dementia-impact-report/nice-impact-dementia.pdf.

- 5.NHS Digital. Recorded Dementia Diagnoses, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/recorded-dementia-diagnoses.

- 6.Robinson E. Alzheimer's Society comment on how coronavirus is affecting dementia assessment and diagnosis. 2020. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2020-08-10/coronavirus-affecting-dementia-assessment-diagnosis.

- 7.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herr M, Ankri J. A critical review of the use of telephone tests to identify cognitive impairment in epidemiology and clinical research. J Telemed Telecare 2013;19:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Järvenpää T, Rinne JO, Räihä I, et al. Characteristics of two telephone screens for cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002;13:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens AP, Ballard C, Beigi M, et al. Implementing remote memory clinics to enhance clinical care during and after COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benge JF, Kiselica AM. Rapid communication: preliminary validation of a telephone adapted Montreal cognitive assessment for the identification of mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropsychol 2021;35:133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai FH-Y, Yan EW-H, Yu KK-Y, Tsui W-S, Chan DT-H, Yee BK. The protective impact of telemedicine on persons with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020;28:1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MM, Tremont G, Ott BR. A review of telephone-administered screening tests for dementia diagnosis. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Dementias 2009;24:58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Khan M, Wootton R, Gray L. A systematic review of the reliability of screening for cognitive impairment in older adults by use of standardised assessment tools administered via the telephone. J Telemed Telecare 2010;16:422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott E, Green C, Llewellyn DJ. Accuracy of telephone-based cognitive screening tests: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Alzheimer Res 2020;17:460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Dementia: a NICE-SCIE guideline on supporting people with Dementia and their carers in health and social care. BPS 2007;148–154. https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/misc/dementia/dementia-fullguideline.pdf?res=true. [PubMed]

- 17.NHS England. Dementia diagnosis and management - A brief pragmatic resource for general practitioners. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp- content/uploads/2015/01/dementia-diag-mng-ab-pt.pdf.

- 18.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97. [PubMed]

- 19.Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: Critical Appraisal Tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews. 2020. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-08/Checklist_for_Diagnostic_Test_Accuracy_Studies.pdf.

- 20.Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies: Critical Appraisal Tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews. 2020. URL: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-08/Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies.pdf

- 21.Naharci MI, Celebi F, Oguz EO, Yilmaz O, Tasci I. The turkish version of the telephone cognitive screen for detecting cognitive impairment in older adults. Am J Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementias 2020;35:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zietemann V, Kopczak A, Müller C, Wollenweber FA, Dichgans M. Validation of the telephone interview of cognitive Status and telephone Montreal cognitive assessment against detailed cognitive testing and clinical diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment after stroke. Stroke 2017;48:2952–2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camozzato AL, Kochhann R, Godinho C, Costa A, Chaves ML. Validation of a telephone screening test for Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Neuropsychol Cognit 2011;18:180–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown JM, Wiggins J, Dawson K, Rittman T, Rowe JB. Test your memory (TYM) and test your memory for mild cognitive impairment (TYM-MCI): a review and update including results of using the TYM test in a general neurology clinic and using a telephone version of the TYM test. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo EH, Lee DY, Kim SG, et al. Validity of the telephone interview for cognitive status (TICS) and modified TICS (TICSm) for mild cognitive imparment (MCI) and dementia screening. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;52:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong SS, Fong KNK. Reliability and validity of the telephone version of the cantonese Mini-mental state examination (T-CMMSE) when used with elderly patients with and without dementia in Hong Kong. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook SE, Marsiske M, McCoy KJ. The use of the modified telephone interview for cognitive Status (TICS-M) in the detection of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2009;22:103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baccaro A, Segre A, Wang YP, et al. Validation of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the modified telephone interview for cognitive status among stroke patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:1118–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dal Forno G, Chiovenda P, Bressi F, et al. Use of an Italian version of the telephone interview for cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konagaya Y, Washimi Y, Hattori H, Takeda A, Watanabe T, Ohta T. Validation of the telephone interview for cognitive Status (TICS) in Japanese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newkirk LA, Kim JM, Thompson JM, Tinklenberg JR, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL. Validation of a 26-point telephone version of the Mini-mental state examination. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004;17:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vercambre M-N, Cuvelier H, Gayon YA, et al. Validation study of a French version of the modified telephone interview for cognitive status (F-TICS-m) in elderly women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:1142–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desmond DW, Tatemichi TK, Hanzawa L. The telephone interview for cognitive Status (TICS): reliability and validity in a stroke sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994;9:803–807. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metitieri T, Geroldi C, Pezzini A, Frisoni GB, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M. The itel-MMSE: an Italian telephone version of the Mini-mental state examination. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:166–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong A, Nyenhuis D, Black SE, et al. Montreal Cognitive assessment 5-min protocol is a brief, valid, reliable, and feasible cognitive screen for telephone administration. Stroke 2015;46:1059–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roccaforte WH, Burke WJ, Bayer BL, Wengel SP. Validation of a telephone version of the Mini-mental state examination. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graff-Radford NR, Ferman TJ, Lucas JA, et al. A cost effective method of identifying and recruiting persons over 80 free of dementia or mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duff K, Beglinger LJ, Adams WH. Validation of the modified telephone interview for cognitive Status in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and intact elders. Alzheimer Disease Assoc Disord 2009;23:38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barber M, Stott DJ. Validity of the telephone interview for cognitive Status (TICS) in post-stroke subjects. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kennedy RE, Williams CP, Sawyer P, Allman RM, Crowe M. Comparison of in-person and telephone administration of the Mini-mental state examination in the university of alabama at Birmingham study of aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1928–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]