Abstract

Objective

The induction of immunity against cancer stem cells (CSCs) can boost the efficiency of cancer vaccines. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are required for the successful activation of anti-tumor immune responses. Glycoprotein 96 (gp96) is a well-known HSP that promotes the cross-presentation of tumor antigens. The aim of the present study was to optimize the temperature for induction of gp96 in grade 3 breast cancer spheres.

Materials and Methods

In the experimental study, CSCs were enriched from breast tumor tissue samples and cultured in DMEM-F12 with epidermal growth factor (EGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), B27, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 22 days. The expression level of CD24 and CD44 as CSC markers was measured by flow cytometry in secondary mammospheres, and the expression of NANOG, SOX2, and OCT4 genes in CSCs was also analyzed using the real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). To find the optimal temperature regulation of gp96, the mammosphere was incubated at different temperatures for 1 hour, and gp96 expression was measured using the western blotting assay.

Results

Primary mammospheres were obtained after seven days of culture, and secondary spheres formed 22 days after passage. Flow cytometry analysis showed that cells with CD24-CD44+phenotype were enriched in the culture period (from 2.6% on day 1 to 32.6% on day 22). Real-time PCR indicated that OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 expression in mammospheres were increased by 3.8 ± 0.6, 17.8 ± 0.6, and 7.7 ± 0.8 fold respectively in comparison to the MCF-7 cell line. Western blot analysis showed that gp96 production was significantly upregulated when mammospheres were incubated at both 42°C and 43°C in comparison to the control group.

Conclusion

Altogether, we found that heat-induced upregulated expression of gp96 in CSCs enriched mammospheres from breast tumor tissue might be used as a complementary procedure to generate more immunogenic antigens in immunotherapy settings.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Cancer Stem Cells, Cellular Spheroid, Heat Shock Proteins

Introduction

Four decades ago, the cancer stem cell (CSC) concept was proposed. It was stated that tumor growth, like the renewal of healthy tissues, is fueled by small numbers of so-called stem cells. It has gradually become clear that many tumors harbor CSCs in dedicated niches, and their identification has not been as obvious as was initially hoped. Recently developed lineage tracing has provided insights into CSC therapeutic response.

Breast cancer is the most common female neoplastic malignancy and the most important cause of female mortality in the world (1). Although this malignancy’s highest incidence is in developed countries, studies showed that its incidence in developing countries has an increasing trend, and patients have a shorter life expectancy (2). Most of the deaths associated with breast cancer are due to metastasis and multiple drug resistance (3). Studies on the tumor microenvironment have revealed a rare cancer cell population with stemness features that seems to be the leading cause of the malignancy. This population is called CSCs, and they have the ability to self-renewal and differentiation into other progenies of cancer cells (4).

CSCs first were detected in acute myeloid leukemia (5), however, their footprint was discovered in all types of cancers later (6-9). They are assumed to be responsible for a tumor’s main malignant characteristics, including invasion, metastasis, drug resistance, and relapse. Although CSCs can be distinguished by surface markers (e.g. CD24) and expression of stemness genes (e.g. OCT4, NANOG, SOX2), efforts to derivate a pure cell line of CSCs from tumor specimens have failed till now (10). Nevertheless, it has been proved that the culture of tumor cells in non-adherent vessels would form spheroids, which are CSCs enriched, so, currently, tumor-derived spheres would prepare the most available models for CSCs examinations (11).

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are necessary molecular chaperones that play an essential role in cells. They also play a crucial role in immunizing against tumors by interfering with the function of professional antigenpresenting cells (APCs), T lymphocytes, and NK cells (12-16). Hsp90B1 (gp96) is a type of HSP that plays a vital role in directing and delivering antigens through MHC class 1 and inducing CD8+ T cells response. This role of HSPs has been used as a basis for clinical trials to develop anticancer vaccines (17, 18).

Despite the efforts that have been made to develop the cancer vaccines, reaching therapeutic success still is still far-fetched. In recent years, immunotherapy methods have hopefully increased the survival of patients (19). To improve the efficacy of these new treatments, boosting the immune response against cancer cells, specifically CSCs, is of the utmost importance. Therefore, upregulating the expression of HSPs in CSCs seems to increase the immunogenicity of these cells, and HSP-upregulated CSCs would be a better tumor antigen source for immunization and cancer vaccine production. In this study, we tried to set up an optimized protocol for the derivation of CSCsenriched spheres from tumor tissue of breast cancer (which is called mammospheres) and upregulation of glycoprotein 96 (gp96) in these cells.

Materials and Methods

In the experimental study, the optimal temperature for induction of gp96 in grade 3 breast cancer spheres was investigated using mammosphere generation, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and western blot techniques.

Preparing tumor sample and generation of mammospheres

Several biopsy samples of tumor tissue were obtained from a female patient with breast cancer during mastectomy and stored in sterile containers containing DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, USA) with streptomycin-penicillin antibiotics (Sigma, USA), then delivered to the lab. Written consent was obtained from three patients before the surgery for using their tissue samples in the research. Approval of the ethics committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences was obtained in advance (P6/97/4/25493). At least three tumor samples were applied to successfully generate mammospheres and the gp94 induction process as described below.

Breast tumor tissues were first minced mechanically by a scalpel and then digested enzymatically using collagenase type IV for 18 hours. Cells obtained from the digested tissue were cultured in 24-well plates (Biofil, China) coated with a thin layer of 1.5% agarose solution, in a low glucose DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) medium supplemented with epidermal growth factor (EGF, 20 ng/ml), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, 20 ng/ml), B27 (2%), bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.5 mg/ml) and penicillin-streptomycin at 37ºC and 5% CO2 (20). The culture medium was refreshed every two days, and primary spheres were harvested on day 7, single cells of each sphere were then transferred into new 24-well plates to form secondary spheres which were then used to perform relevant tests on day 22.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis tissue sections were cut at 6 µm thickness, mounted on slides, and antigen retrieval was performed. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing the slides in 1.0% H2 O2 , and 0.1% NaN3 in tris-buffered saline (TBS, Sigma, Germany) for 10 minutes. Nonspecific antibody binding was inhibited by incubating the sections in 4% commercial nonfat skim milk powder (Sigma, Germany) in TBS for 15 minutes; the slides were transferred to a humidified chamber and incubated with primary anti ER (2.5 µg/ml), PR (2.5 µg/ml) and Herr-2/neu (5 µg/ml) antibodies (Abcam, UK) overnight at room temperature. The sections were washed by TBS and incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins (Abcam, UK) for 45 minutes and then with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Abcam, UK) for 15 minutes. Antigenic sites were identified using 0.05% 3,3-diaminobenzidine with H2 O2 (Sigma, Germany) as substrate and were then lightly counterstained with hematoxylin before being examined with light microscopy (21).

Flow cytometry

To confirm CSCs enrichment in mammospheres, the flow cytometry technique was used to determine the percentage of CSCs population in trypsinized secondary mammospheres on the 22nd day of culture. For this assessment, CD44+ CD24- cells were considered as CSCs, and the percentage of this population was compared with single cells isolated from digested tumor tissue on the first day of culture.

Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Real-time RT-PCR was carried out according to the method described by Park et al. (22). Briefly, single cells of trypsinized secondary mammospheres were used for total RNA extraction by a commercially available kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Realtime RT-PCR was then performed on the synthesized cDNA to evaluate the expression level of stemness genes including OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2, resultant cDNA amplified by Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Germany) in a Rotor-gene 3000 thermal cycler device (Corbett, Australia). The Syber Green probe (Qiagen, Germany) was used for the detection of DNA amplification signals. The expression level of each gene was normalized to the GAPDH expression as a housekeeping gene, and breast cancer cell line (MCF7) as a control to calculate the relative expression (2-ΔΔCt) of stemness genes.

Western blot

To induce upregulation of gp96 expression, mammospheres were incubated for 60 minutes at 42ºC and 43ºC in experimental groups and at 37ºC in the control group; these spheres were then trypsinized, and single cells were used for Western blot analysis. Cells were lysed with lysing buffer (50 mM TrisHCl, pH=7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40) supplemented with complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Cell lysates (20 mg) were separated by electrophoresis on 10% sodium dodecyl-sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The blot was blocked with TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH=7.6, 136 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% skim milk and then incubated with primary antibody against gp96 (2 µg, ml) and Actin (as a housekeeping protein, Santa Cruz, USA) at 4ºC overnight. The next day, after washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. The bands were amplified using a chemiluminescent solution and photographed with the ECL kit (GE/Amersham Healthcare, UK) and Documentation Gel (SYNGENE, UK) (23).

Statistical analysis

Data from at least three independent experiments were expressed as means ± standard deviation, SD. Each data point of real-time PCR was run at least in triplicates and independent experiments were performed at least three times. Student’s t tests or ANOVA (SPSS, version 21, IBM, USA) were used to determine statistically significant differences and P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

Results

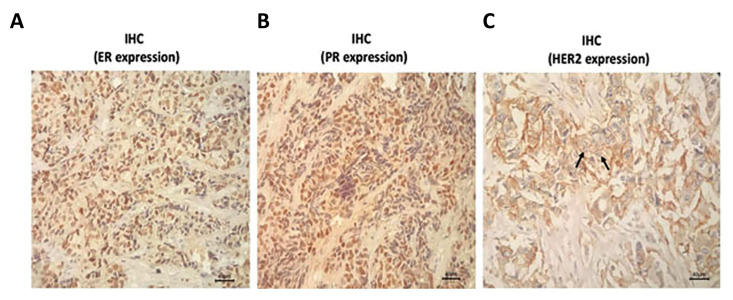

Immunohistochemistry characteristics of the tumor sample

The histopathology report of the tumor biopsy indicated that the patients had undergone a stage IV, grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma breast cancer (data not shown). Tumor size was 3.5×2cm and involvement of axillary lymph node was reported. IHC study showed that the tumor was triple positive for Estrogen, Progesterone, and Her2-neu receptors (Fig .1).

Fig.1.

Immunohistochemical analysis. Tumor specimen was stained immunohistochemically using anti ER, PR and Her-2/neu monoclonal antibodies. From left to right presents the expression of ER, PR, and Her2/neu receptors respectively (scale bar: 100 µm).

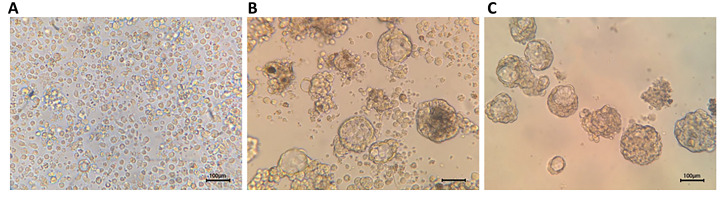

Tumor-derived mammospheres generation

The culture of tumor single cells with described protocol led to the formation of spheres after 7 days. The morphology of spheres was similar to what has been previously reported. The sphere trypsinized and passaged into subsequent plates, which led to the formation of secondary mammospheres on day 22 (Fig .2).

Fig.2.

Mammospheres derived from tumor tissue. A. Cells isolated from digestion of tumor tissue samples on the first day of culture, B. Primary mammospheres on the 7th day of culture, and C. Secondary mammospheres formed from the passage of primary mammospheres on the 22nd day of culture (scale bar: 100 µm).

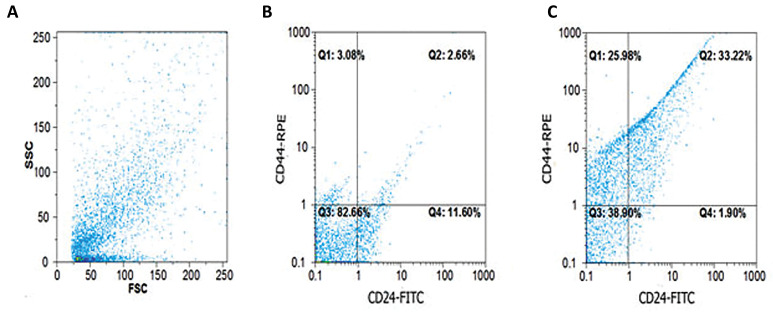

Flow cytometric analysis of cancer stem cells in tumorderived spheres

To determine the percentage of CSCs among other cancer cells, the population of CD44+ CD24- cells as CSC phenotype was measured with flow cytometry. The percentage of CSCs on the first day of culture was 2.6%, whereas this population on the 22nd day of culture was 33.2% in trypsinized mammospheres (Fig .3).

Fig.3.

Phenotypic characterization of cancer stem cells (CSCs) enriched mammospheres. A. Flow cytometric analysis of CSCs was carried out using anti CD24 and anti CD44 monoclonal antibodies. Forward and side scatter analysis of cells are shown. B. Cells with CD44+ CD24- phenotype had a low percentage on the first day of culture, and C. But the population of these cells considerably increased in the 22nd day of culture in mammospheres.

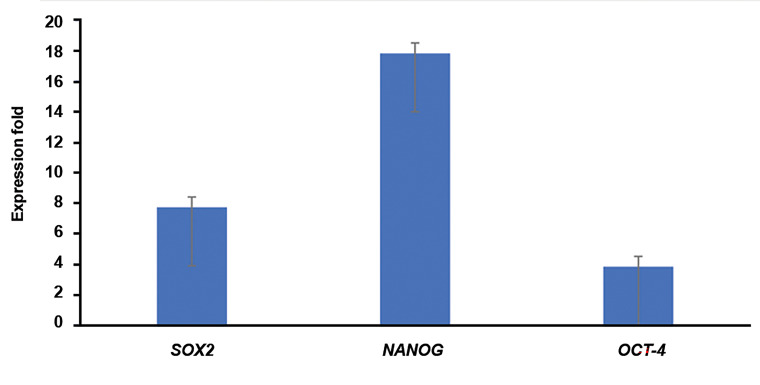

Stemness genes expression

Relative expression of stemness genes, including OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 were measured in trypsinized mammospheres in comparison with the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line as the control by real-time RT-PCR. Relative expression of these genes was significantly higher in mammospheres, which was 3.83 ± 0.62 fold for OCT-4, 17.83 ± 0.6 fold for NANOG, and 7.73 ± 0.78 fold for SOX2 (P≤0.001, Fig .4).

Fig.4.

Stemness genes expressioin. Expression of OCT-4, NANOG, and SOX2 was meassured in single cells of mammospheres in comparison to MCF-7 cell line. The expression level of genes in the MCF-7 cells was considered as 1 and the expression fold of them in single cells of cultured mammospheres was reported (P<0.001).

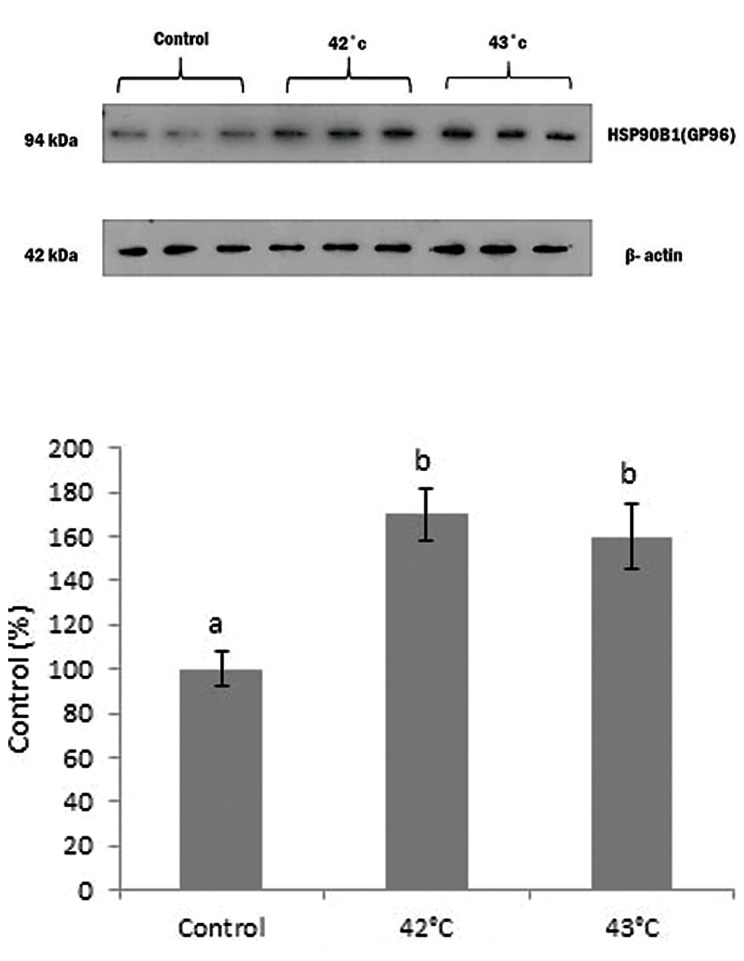

Glycoprotein 96 expression

Incubation of mammospheres for a short time (60 minutes) at 42°C and 43°C led to the upregulation of gp96 protein expression detected by Western blot. However, the viability of mammospheres did not decline after such incubation conditions. The sharpness of gp96 bands at 42°C and 43°C incubated mammospheres were significantly higher than 37°C (P≤0.001), but they have no considerable difference from each other (Fig .5).

Fig.5.

Expression levels of gp96 protein. Mammospheres were incubated in 42°C and 43°C as well as 37°C (control) for 1 hour and the expression of gp96 protein was measured using Western bloting test. Different letters indicate significant differences between mean values (P=0.03).

Discussion

CSCs are a group of cancerous cells within the tumor bulk with stem cell-like characteristics, including selfrenewal properties, due to which the term Tumor Initiating Cells (TIC) has been used for them (11). It seems that the stemness properties of CSCs could be an explanation for cancer recurrence and chemoresistance. Among the other described characteristics for CSCs, the expression of some markers like CD44, CD133, and CD24, and on the transcription level, the expression of SOX2, NANOG, and OCT4 is crucial (24).

One of the assays that can be applied to isolate CSCs, besides surface markers, is the Spheroid formation assay, which is based on the capability of these cells to generate multicellular three-dimensional (3D) spheres in vitro (25). So far, culture methods, including organotypic multicellular spheroid model, multicellular tumor spheroids, tissue-derived tumorspheres, and tumorspheres assay, have been developed (26). In this study, the tumorspheres assay was applied, which is based on dissociating tumor tissue to the suspension of single cells and culturing the obtained cellular suspension in a low adherent surface in a serum-free media which is supplemented with EGF and b-FGF growth factors to enrich CSCs. This condition can provide the establishment of spherical colonies. However, the formation of tumor structure cannot be fully mimicked by using this method (27).

In the present study, we successfully achieved mammospheres from breast tumor tissue. Our tumorderived mammospheres were typical in morphology. We also passaged primary mammospheres to form secondary ones by trypsinization. The CSC population was enriched in mammospheres, which were 2.6% on the first day of culture compared to 33.2% on the 22nd day of culture.

SOX2 gene belongs to the family of SRY-related high mobility group (HMG) which is located on chorormose 3 and implicated in the cell development process by determining their fate and preserving stemness phenotype. It is well-known that SOX2 takes part in different molecular mechanisms and states of diseases including cancer. It has been shown that dysregulated and increased expression of SOX2 can impact proliferation, migration, invasion, resistance to apoptosis, and colony formation features in CSCs and tumor cells (28). NANOG is another master transcription factor of embryogenesis, located on chromosome 12, and engaged in conserving pluripotency and self-renewal potential in stem cells through the Insulin-like growth factor1 receptor (IGF1R) pathway. Overexpression of this transcription factor has been detected in different cancers, leading to inhibiting apoptosis and establishing chemoresistance (29). OCT4, also recognized as POU5F1, belongs to the POU family of transcription factors on chromosome 6, and along with NANOG and SOX2, plays a vital role in developmental pathways and tumorigenesis. Since the enhanced expression of these genes has been linked to poor prognosis in patients with cancer and resistance to chemotherapy (30), in the present study, we analyzed their expression levels in ex vivo generated mammospheres and found that stemness genes, including OCT-4, NANOG, and SOX2, overexpressed in mammospheres compared to a regular breast cancer cell line (MCF-7).

Another purpose of this study was to optimize incubation conditions for the upregulation of HSPs in mammospheres, which would lead to an increase in the immunogenicity of CSCs for immunotherapy settings. We showed that incubation of mammospheres for 60 minutes at 42-43°C upregulated GP96 protein expression (a member of the HSP90 family) without affecting the viability of mammospheres cells.

Homologous members of the HSP family are found in all parts of the cytosol, nucleus, mitochondria, endosomes, lysosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, intracellular membranes, and plasma membrane (31). Thus, HSPs isolated from tumor cells are potentially rich in tumor antigens (32). Given the role of HSP-peptide complexes in the activation and maturation of APCs, this complex may activate the polyclonal T lymphocyte response against tumor antigens. Under these conditions, even if the tumor loses some antigens under the selective pressure of the immune system, multiple T-cell clones will still be available to destroy the tumor cells (32, 33). The application of this approach makes it unnecessary to find tumor-specific antigens for each patient. Among the most critical tumor-derived HSPs facilitating the entry of antigenic peptides into MHC class I molecules are HSP70, and gp96 (17, 34, 35), however, the distribution of HSP molecules within the cell follows different prototypes. Gp96 molecules are typically present in the endoplasmic reticulum (36). Studies have shown that targeting HSPs, including HSP90, induces apoptosis in cancer cells (37), thus, it is necessary to evaluate the optimal conditions causing induction of these molecules to obtain the maximum potential of tumor antigenicity.

According to our findings, the best temperature and incubation time to induce maximal gp96 in breast cancer mammospheres were 42-43°C for 1 hour. In 1998, Madersbacher et al. (38) indicated that expression of HSP27 in LNCaP cells treated with heat shock from 43- 49° C for 60min could increase in a temperature-dependent manner, though this study was performed on a cell line and expression of HSP27 was the primary purpose. Schueller et al. in 2001 showed that in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2, treating cells at 41.8° C for 60 minutes, increased the expression level of HSP70 and HSP90, which could substantially escalate the immunogenicity of the tumor, as well as the immune response to heat-shocked HepG2 cells Although the cell lines used in these two studies, were different, both of them had an epithelial origin and applying almost the same temperature resulted in rising expression levels of HSP70 and HSP90, which was consistent with the result of our study (39, 40).

This study had some limitations; first, the difficulty of preserving mammospheres for a more extended period without causing differentiation to investigate long term effects of heat treatment on the gp96 expression, Second, in this study, the samples were from the same patients of the same stage while obtaining tissue samples from patients of different stages could impact the percentage of the presence of CSCs and expression of gp96. Moreover, we did not study the influence of higher temperatures than 43°C on the structure and the expression of gp96.

Conclusion

In this study, we showed that tumor-derived mammospheres are CSCs-enriched, and the expression level of stemness genes is higher than regular breast cancer cell lines. It was also revealed that incubation of these mammospheres at a temperature between 42-43° C for 60 minutes would upregulate gp96 protein expression and make mammospheres a potent tool for preparing more immunogenic tumor antigens for use in immunotherapy modalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Institute of Biotechnology of Urmia University for the discussions. In particular, they would like to thank Samira, Zand, Razieh Pak Tarmani, and Ashkan Basirnia for technical assistance and give special gratitude to Dr. Hamid Mehdizadeh for helpful comments on the manuscript. The study was funded by the Vice President of Research and Technology, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran (Grant no. 3.PD.462).The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

N.D.; Designed this study and reviewed the manuscript. A.H.I.; Carried out laboratory management and technical procedures as well as statistical analysis. R.M.; Provided the clinical data and samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. The Lancet. 2019;394:1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31709-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naser Al Deen N, Nassar F, Nasr R, Talhouk R. Cross-roads to drug resistance and metastasis in breast cancer: miRNAs regulatory function and biomarker capability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1152:335–364. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sousa B, Ribeiro AS, Paredes J. Heterogeneity and plasticity of breast cancer stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1139:83–103. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14366-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capp JP. Cancer Stem Cells: from historical roots to a new perspective. J Oncol. 2019;2019:5189232–5189232. doi: 10.1155/2019/5189232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammareri P LY, Francipane MG, Bonventre S, Todaro M, Stassi G. Isolation and culture of colon cancer stem cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;86:311–324. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Yang K, Yu J, Meng W, Yuan D, Bi F, et al. Identification and expansion of cancer stem cells in tumor tissues and peripheral blood derived from gastric adenocarcinoma patients. Cell Res. 2012;22(1):248–258. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017;23(10):1124–1134. doi: 10.1038/nm.4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbaszadegan MR, Bagheri V, Razavi MS, Momtazi AA, Sahebkar A, Gholamin M. Isolation, identification, and characterization of cancer stem cells: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(8):2008–2018. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li R, Qian J, Zhang W, Fu W, Du J, Jiang H, et al. Human heat shock protein-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes display potent antitumour immunity in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(5):690–701. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shevtsov M, Pitkin E, Ischenko A, Stangl S, Khachatryan W, Galibin O, et al. Ex vivo Hsp70-activated nk cells in combination with pd-1 inhibition significantly increase overall survival in preclinical models of glioblastoma and lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2019;10:454–454. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Chen J, Liu Y, Luo W. Dendritic-tumor fusion cells derived heat shock protein70-peptide complex has enhanced immunogenicity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126075–e0126075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu BX, Hong F, Zhang Y, Ansa-Addo E, Li Z. GRP94/gp96 in Cancer: Biology, Structure, Immunology, and Drug Development. Adv Cancer Res. 2016;129:165–90. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Sedlacek AL, Pawaria S, Xu H, Scott MJ, Binder RJ. Cutting Edge: the heat shock protein gp96 activates inflammasomesignaling platforms in APCs. J Immunol. 2018;201(8):2209–2214. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strbo N, Garcia-Soto A, Schreiber TH, Podack ER. Secreted heat shock protein gp96-Ig: next-generation vaccines for cancer and infectious diseases. Immunol Res. 2013;57(1-3):311–25. doi: 10.1007/s12026-013-8468-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, Fan H, Li Y, Zheng H, Li X, Li C, et al. CD133 epitope vaccine with gp96 as adjuvant elicits an antitumor T cell response against leukemia. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 2017;33(6):1006–1017. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.160481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanmamed MF, Chen L. A Paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy: from enhancement to normalization. Cell. 2018;175(2):313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17(10):1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruan S, Liu Y, Tang X, Yang Z, Huang J, Li X, et al. HER-2 status and its clinicopathologic significance in breast cancer in patients from southwest China: re-evaluation of correlation between results from FISH and IHC. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10(7):7270–7276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park HS, Han HJ, Lee S, Kim GM, Park S, Choi YA, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients using cytokeratin- 19 real-time RT-PCR. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58(1):19–26. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simsek BC, Turk BA, Ozen F, Tuzcu M, Kanters M. Investigation of telomerase activity and apoptosis on invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast using immunohistochemical and Western blot methods. Eur Rev Med Pharma Sci. 2015;19(16):3089–3099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao W, Li Y, and Zhang X. Stemness-related markers in cancer. Cancer Transl Med. 2017;3(3):87–95. doi: 10.4103/ctm.ctm_69_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amaral RLF, Miranda M, Marcato PD, Swiech K. Comparative analysis of 3D bladder tumor spheroids obtained by forced floating and hanging drop methods for drug screening. Front Physiol. 2017;8:605–605. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiswald LB, Bellet D, Dangles-Marie V. Spherical cancer models in tumor biology. Neoplasia. 2015;17:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akbarzadeh M, Maroufi NF, Tazehkand AP, Akbarzadeh M, Bastani S, Safdari R, et al. Current approaches in identification and isolation of cancer stem cells.J Cell Physiol. J Cell Physiol; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novak D, Huser L, Elton JJ, Umansky V, Altevogt P, Utikal J. SOX2 in development and cancer biology.Semin Cancer Biol. Semin Cancer Biol; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gawlik-Rzemieniewska N, Bednarek I. The role of NANOG transcriptional factor in the development of malignant phenotype of cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1121348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villodre ES, Kipper FC, Pereira MB, Lenz G. Roles of OCT4 in tumorigenesis, cancer therapy resistance and prognosis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;51:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Maio A, Vazquez D. Extracellular heat shock proteins: a new location, a new function. Shock. 2013;40(4):239–246. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182a185ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly M, McNeel D, Fisch P, Malkovsky M. Immunological considerations underlying heat shock protein-mediated cancer vaccine strategies. Immunol Lett. 2018;193:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yun CW, Kim HJ, Lim JH, Lee SH. Heat shock proteins: agents of cancer development and therapeutic targets in anti-cancer therapy. Cells. 2019;9(1):60–60. doi: 10.3390/cells9010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng Y, Graner MW, Katsanis E. Chaperone-rich cell lysates, immune activation and tumor vaccination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0694-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Binder RJ, Srivastava PK. Peptides chaperoned by heat-shock proteins are a necessary and sufficient source of antigen in the cross-priming of CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:593–599. doi: 10.1038/ni1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ansa-Addo EA, Thaxton J, Hong F, Wu BX, Zhang Y, Fugle CW, et al. Clients and oncogenic roles of molecular chaperone gp96/ grp94. Curr Top Med Chem. 2016;16(25):2765–2778. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160413141613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoter A, El-Sabban ME, Naim HY. The HSP90 family: structure, regulation, function, and implications in health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9):2560–2560. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madersbacher S, Groble M, Kramer G, Dirnhofer S, Steiner GE, Marberger M. Regulation of heat shock protein 27 expression of prostatic cells in response to heat treatment. Prostate. 1998;37(3):174–181. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19981101)37:3<174::aid-pros6>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schueller G PP, Friedl J, Stift A, Dubsky P, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, Jakesz R, et al. Heat treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma cells: increased levels of heat shock proteins 70 and 90 correlate with cellular necrosis. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(1A):295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaimoku R, Miyashita T, Tajima H, Takamura H, Harashima AI, Munesue S, et al. Monitoring of heat shock response and phenotypic changes in hepatocellular carcinoma after heat treatment. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(10):5393–5401. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]