Abstract

The therapeutic adherence to drug therapies is a crucial aspect for the proper management of chronicity. Over time, we are witnessing the evolution of the concept of adherence: today the patient must play an increasingly active role in the entire process in order for the pharmacological therapy to be fully successful. Poor therapeutic adherence can cause a bad success of the treatment path and, at the same time, lead to higher expenses. In this regard, it is necessary that each health company must undertake dedicated and organized paths. At the Asl Napoli 3 Sud an analysis of adherence in the year 2020 was carried out regarding the major pharmacological classes prescribed: anti-hypertensives, antidepressants, statins, anti-diabetes, and drugs for bpco and osteoporosis. The results show a very poor adherence where, at best, we have an adherence of about 50% of the therapies dispensed. This analysis shows how it is necessary to share actions with doctors and patients themselves to try to stem this phenomenon that is harmful both therapeutically and economically. Thus, it becomes essential to search for possible strategies for improvement and include them in the Diagnostic-Therapeutic-Assistance Pathways (PDTA).

Keywords: adherence, compliance, drugs, treatment, pharmacology

Introduction

Therapeutic adherence is a primary and critically important aspect of achieving clinical efficacy of drug administrations that are prescribed by physicians and dispensed by pharmacists. 1 This is defined and established by numerous literature studies that correlate adherence with pharmacological efficacy of many categories of drugs. 2 The achievement of therapeutic adherence is unfortunately not an easy goal to achieve and to realize: many health companies in analyzing the data of prescription and dispensing have understood how patients are not very active in implementing the prescribed therapies. This leads, both to the non-achievement of the pharmacological need, and, following therapeutic failure, to increased spending toward newer treatments that often have much higher costs than traditional treatments.3,4 Today, all therapeutic classes present different pharmacological alternatives thanks to the continuous research and marketing of new drugs that have a higher cost-effectiveness ratio. However, this does not mean that traditional first-line therapies no longer have therapeutic value. For these reasons it is necessary to raise awareness so that clinicians, pharmacists and patients themselves have an active role in the path toward clinical efficacy without therapeutic failures that lead to clinical complications with simultaneous increase in costs. This is especially evident in chronic diseases where the patient takes a given therapy for life. 5

The Experience of Asl napoli 3 Sud

In the year 2020, prescription and dispensing data for the main therapeutic classes were extrapolated. This was done so that it would be possible to assess the patient’s adherence to treatment by withdrawing his or her therapy at the right time. All prescriptions made by general practitioners were analyzed. The prescription data for each individual patient are present in the company database. These data were cross-referenced with the dispensations made by the pharmacies in the territory of the Asl Napoli 3 Sud. This has made it possible to verify both the correct prescribing periodicity by the doctors and the correct withdrawal of the therapy by the patient. These two pieces of information, together with the evaluation of the timing, has allowed to carry out an evaluation of adherence.

A 550 000 prescriptions were examined in the year 2020 covering 6 categories of drugs: antihypertensives, antidiabetics, antidepressants, statins, bpco drugs, osteoporosis drugs. The prescriptions concerned 45 830 patients, all of whom were Caucasian and resident in the area south of Naples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stratification of Patients Analyzed.

| N involved patients | 45 830 |

| Age classes | |

| 0-25 | 2320 |

| 26-50 | 12 758 |

| 51-75 | 23 654 |

| 76-100 | 7098 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 20 760 |

| Female | 25 050 |

| Undefined | 20 |

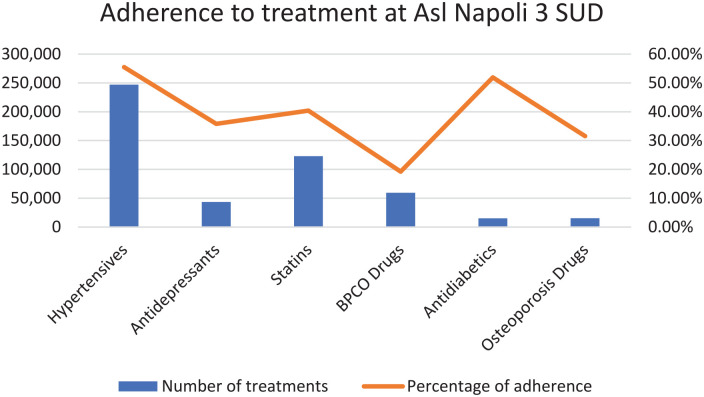

This analysis highlighted the very low adherence to prescribed treatments. Only antihypertensives and drugs used in diabetes achieved a 50% adherence. Other drug classes even showed adherence below this percentage (Figure 1). The drugs with the lowest adherence were found to be those for COPD, a category of drugs with a fairly high healthcare cost. These data have raised alarm bells. Any planned action must be taken to limit this incidence, which leads to treatment failures and increased costs of chronic disease management. Such government action is essential to ensure sustainability and appropriateness of care.

Figure 1.

The chart shows the main drug treatments. It highlights the correlation between adherence and number of treatments.

Discussion

A strategic success, as suggested by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, could be to share the care pathway through all the actors involved in the process, including the patient. The patient, who is aware of his disease and the treatment to be undertaken, will certainly be more involved and, therefore, compliant. In fact, today the term “compliance” is increasingly being replaced by “adherence” because we want to underline how there is a therapeutic alliance between patient and health personnel: a cooperation in reaching the therapeutic target that goes beyond the patient’s comfort in passively taking a given therapy. Two concepts that can however coexist: a therapy can have a greater compliance, related to the patient’s comfort in taking it, and, at the same time, have a good adherence profile, that is the possibility that the patient is constant in following his prescriptions.4,5 In any case it is crucial to define the fact that the patient is not an outsider but cooperates together with the health care staff to establish the right pharmacological strategy. Obviously this presupposes a responsible patient, which is not always possible. Therefore this approach may not be sufficient. Other factors that may limit adherence may be: complex treatment schedules (by the treating physician) and access to care hampered by complex healthcare systems (limited time and healthcare support by corporate organizations).6,7 Improving adherence is therefore a multifactorial process that must have rational solutions. The Ministry of Health has highlighted the need, especially in the field of chronicity, for organizational solutions aimed at promoting adherence to prescriptions, especially in the case of poly-pharmacy, with the inclusion of such strategies in the Diagnostic-Therapeutic-Assistance Pathways (PDTA). 8

Conclusion

The extrapolated data from health care providers should guide strategies to break down existing barriers to adherence. A series of corrections must be implemented to improve the accessibility of treatment and to facilitate the therapeutic schemes of taking polytherapies that are often too complex for patients. Last but not least, the behavioral and educational aspect must not be ignored. Doctors and all healthcare staff must cooperate with the patient in order to involve him/her in the process and agree together on the right therapeutic strategy to achieve the clinical target. These are the objectives accepted at Asl Napoli 3 SUD with the aim of improving the adherence rate in the coming years. The constant analysis of the data in the next few years will indicate whether these actions can be decisive in the slow process leading to adherence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the corporate health management and the pharmaceutical department for authorizing access and use of company data for scientific purposes.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions: FF: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology. LN: Writing – original draft. EN:Validation. UT: Validation. AV: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Availability of Data and Materials: Full availability of data and materials.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Consent to Publish: The authors consent to the publication of the manuscript

ORCID iD: Francesco Ferrara  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9298-6783

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9298-6783

References

- 1. Aronson JK. Compliance, concordance, adherence. Br J ClinPharm. 2007;63:383-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J ClinPharmacol. 2012;73:691-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. From compliance to concordance: towards shared goals in medicine taking. RPS, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministry of Health. National Chronicity Plan. 2016. Accessed November, 2021. www.salute.gov.it/

- 6. Cross AJ, Elliott RA, Petrie K, Kuruvilla L, George J. Interventions for improving medication-taking ability and adherence in older adults prescribed multiple medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD012419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elseviers M, Wettermark B, Almarsdottir AB, et al. Drug utilization research: methods and applications. John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ministry of Health. The New Guarantee System (NSG) – Experimentation of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Assistance Pathways (PDTA) indicators. Pathways – PDTA. Accessed November, 2021. www.salute.gov.it/ [Google Scholar]