Abstract

Objective

Being the next of kin of a person with a brain tumour is a stressful experience. For many, being a next of kin involves fear, insecurity and overwhelming responsibility. The purpose of this study was to identify and synthesise qualitative original studies that explore coping in the role as next of kin of a person with a brain tumour.

Methods

A qualitative metasynthesis guided by Sandelowski and Barroso’s guidelines was used. The databases Medline, CHINAL and PsycINFO were searched for studies from January 2000 to 18 January 2022. Inclusion criteria were qualitative original studies that aimed to explore coping experience by the next of kin of a person with brain tumour. The next of kin had to be 18 years of age or older.

Results

Of a total of 1476 screened records data from 20 studies, including 342 participants (207 females, 81 males and 54 unclassified) were analysed into metasummaries and a metasynthesis. The metasynthesis revealed that the next of kin coping experiences were characterised by two main themes: (1) coping factors within the next of kin and as a support system, such as their personal characteristics, perceiving the role as meaningful, having a support system, and hope and religion; (2) coping strategies—control and proactivity, including regaining control, being proactive and acceptance.

Conclusion

Next of kin of patients with brain tumours used coping factors and coping strategies gathered within themselves and in their surroundings to handle the situation and their role. It is important that healthcare professionals suggest and facilitate these coping factors and strategies because this may reduce stress and make the role of next of kin more manageable.

Keywords: MEDICAL ETHICS, ONCOLOGY, Head & neck tumours

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The qualitative approach makes an important contribution to the research field by providing a deeper understanding of coping factors and strategies used by the next of kin of a person with a brain tumour.

Most of the included studies in this metasynthesis were high-quality studies.

Our sample is highly multicultural with different geographical origins represented and includes different welfare and healthcare systems, and different cultures and religions.

The majority of the sample were women, and a more heterogeneous sample might have revealed more nuanced findings regarding the role of next of kin.

Introduction

In 2020, 308 102 people with cancer in the central nervous system were registered worldwide.1 The diagnosis of brain tumour is very confronting, with 56% of patients experiencing one or more symptoms. Hemiparesis and cognitive challenges are most frequently reported but also headaches, nausea and vomiting, vision challenges, epileptic seizures and personality changes are considered common symptoms.2–5 Changes in behaviour and personality are considered particularly challenging, both for the patient and for the next of kin, as these may include apathy, loss of initiative and empathy, indifference, selfishness, physical and mental aggression, impaired emotional control and social skills, and tendencies toward childish behaviour, among others.3 5 6 Studies show that the disease can be more challenging and stressful for the next of kin than for the patients. The next of kin have high rates of depression, anxiety, various physical pain, adjustment difficulties, loneliness and high work absence, as well as a reduced quality of life.7–11 Studies also show that both patients and next of kin miss additional follow-up, support and information from healthcare providers, family, friends and the community in their struggle to cope with everyday life.12 13

All these strains can lead to next of kin experiencing stress and lack of coping. Lazarus and Folkman define coping as a cognitive and behavioural endeavour under constant change, dealing with external and/or internal demands that a cognitive assessment indicates as stressful or exceeding personal resources. When dealing with these demands, the next of kin has to review available coping strategies to be able to make the situation more manageable, meaning active actions the next of kin use to cope in the situation.9 13 14

There are some original qualitative studies that have explored coping in the role as next of kin of a person with a brain tumour. To our knowledge, this research has not been synthesised. Such information is of great importance, especially for healthcare providers working with this group of caregivers. With improved understanding, they may be better equipped to facilitate a more manageable everyday life among the next of kin. Previous quantitative research directed at these aspects exists,8–11 15 but we were interested in studies that were personal and focused on the lived experience of next of kin, hence the choice of qualitative studies. Therefore, the purpose of this metasynthesis was to identify and synthesise evidence from original qualitative studies regarding the experience of coping in the role as next of kin of a person with a brain tumour. The findings are discussed in the context of Lazarus and Folkman’s stress theory14 and their approach to coping with stress in order to interpret our findings in a theoretical context.

Methods

Design

The study is a metasynthesis within the interpretative paradigm. It was inspired by a phenomenological–hermeneutic design because the aim was to identify and synthesise qualitative original studies that explored next of kin attitudes and experiences.16 The metasynthesis process consisted of five steps: (1) formulating the purpose and rationale of the study; (2) searching for and retrieving relevant qualitative research studies; (3) critically appraising the included studies; (4) classifying the findings, and finally; (5) synthesising the findings.

Search strategy

In collaboration with an experienced librarian, we conducted a systematic search in the PsycINFO, OVID, CHINAL and Medline databases via the EBSCO host from January 2000 until 18 January 2022. For search strategy see online supplemental material 1.

bmjopen-2021-052872supp001.pdf (58.3KB, pdf)

The inclusion criteria were qualitative original studies published in English, Norwegian, Swedish or Danish that aimed to explore coping experience by the next of kin of a person with a brain tumour, regardless of tumour type and stage which enhanced their role as next of kin. The next of kin had to be 18 years of age or older. The exclusion criteria were studies that did not clearly identify coping, coping that included the participants’ experiences in the role of bereaved and not next of kin, and studies including diagnoses other than a brain tumour.

Search outcome

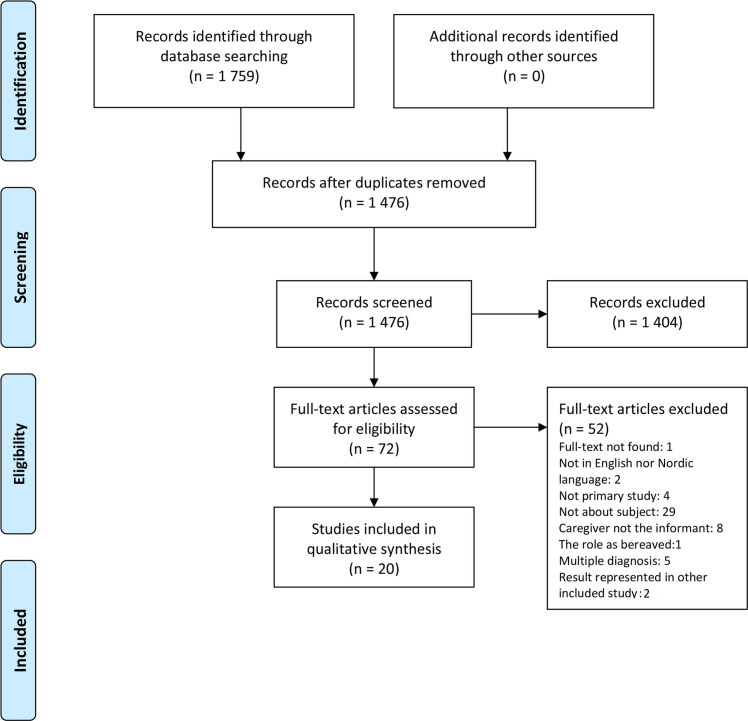

The search strategy generated 1476 unique citations. Titles and abstracts were screened by the authors using Rayyan, a systematic review management software.17 A final consensus regarding the eligible articles was obtained through a group discussion between the authors. Seventy-two papers were read in full and evaluated against the inclusion criteria by both authors; twenty of these were included in the metasynthesis. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart with a full overview of the screening process. The search output is presented in the PRISMA flowchart. The authors read the full text of the eligible articles and independently extracted data from the included studies; this process is also illustrated in figure 1. Consensus for data extraction was obtained as part of a group discussion between the authors. Online supplemental material 2 lists the title, author(s), study country, year of publication, aim, analysis and study participants of all included studies. Most studies were from Europe: Sweden (3), Great Britain (3), Denmark (1), Belgium (1) and Turkey (1); seven were from Canada (3) and the USA (4), two from Australia and two from Taiwan. The tumour type and stage varied. For details, see online supplemental material 2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the inclusion process. Source: Moher et al.51

bmjopen-2021-052872supp002.pdf (77.8KB, pdf)

Quality appraisal

The quality of the 20 papers was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for qualitative studies. The first evaluation was conducted blinded and independently by AWL and GR whose CASP evaluations were then compared. Using the criteria in CASP for independent assessment, the authors mutually agreed on a final quality evaluation. For details, see table 1.

Table 1.

Critical appraisal of the included studies

| Author | 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate? | 5. Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 10. How valuable is the research? | Impact factor |

| Arber et al2 | Y | Y | C | C | Y | N | Y | C | Y | V | Not found |

| Arber et al24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | V | 1.697 |

| Coolbrandt et al23 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | V | 2.022 |

| Cutillo et al30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | C | V | 2.170 |

| Edvardsson and Ahlström25 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | V | 3.470 |

| Janda et al22 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | V | 2.754 |

| Huang et al27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | V | 2.592 |

| Lipsman et al37 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | V | 2.922 |

| Lou et al34 | C | Y | Y | C | Y | N | N | C | Y | V | 2.022 |

| Ownsworth et al35 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | C | Y | Y | V | 4.137 |

| Piil et al21 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | V | 1.096 |

| Russell et al10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | V | 1.197 |

| Schmer et al31 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | V | 1.096 |

| Schubart et al20 | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | V | 3.470 |

| Hricik et al36 | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | N | Y | N | V | 1.438 |

| Shortman et al29 | Y | Y | Y | C | C | N | Y | N | Y | V | 1.918 |

| Strang and Strang28 | C | C | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | V | 4.956 |

| Tastan et al32 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | V | 1.096 |

| Wideheim et al26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | C | Y | Y | V | 2.022 |

| Zelcer et al33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | C | Y | Y | V | 5.731 |

Criterion: Y=yes; N=no; C=can’t tell; V=valuable; NV=not valuable.

The included studies that were appraised according to CASP are listed in table 2. All studies had clearly stated the study aim and the qualitative methodologies were considered appropriate. Furthermore, several of the studies had been published in highly ranked journals. The most poorly addressed issue (criteria number 6 in the CASP list) was the influence of the researcher on the research and vice versa.

Table 2.

Thematic overview showing the studies’ contribution to the different themes and subthemes

| Author | Coping factors within the next of kin and as a support system | Coping strategies—control and proactivity | |||||

| Personal characteristics | Perceiving the role as meaningful | Having a support system | Hope and religion | Regain control | Proacitivity | Acceptance | |

| Arber et al2 | V | V | |||||

| Arber et al24 | V | ||||||

| Coolbrandt et al23 | V | V | V | V | |||

| Cutillo et al30 | V | V | V | V | |||

| Edvardson and Ahlström25 | V | V | V | V | V | V | |

| Janda et al22 | V | V | V | ||||

| Huang et al27 | V | V | V | ||||

| Lipsman et al37 | V | V | V | ||||

| Lou et al34 | V | V | V | V | V | ||

| Ownsworth et al35 | V | V | V | ||||

| Piil et al21 | V | V | V | V | V | ||

| Russell et al10 | V | V | V | V | V | ||

| Schmer et al31 | V | V | V | ||||

| Schubart et al20 | V | V | V | V | |||

| Hricik et al36 | V | V | V | ||||

| Shortman et al36 | V | V | V | V | |||

| Strang and Strang28 | V | V | V | ||||

| Tastan et al32 | V | V | |||||

| Wideheim et al26 | V | V | V | V | |||

| Zelcer et al33 | V | V | V | V | |||

V=valuable.

Data abstraction and analyses

As suggested by Sandelowski and Barroso,16 two approaches to qualitative synthesis were used. The first of these involved qualitative metasummaries of qualitative findings from the original studies. This method is defined as qualitative, but the findings are presented quantitatively. The second involved a metasynthesis that developed new interpretations of the target findings from the original studies.16 The narrative analysis was inspired by Lindseth and Norberg’s phenomenological–hermeneutic methods.18 Three steps were followed. First, the empirical materials were read several times. Second, after extraction, the target findings were imported into NVivo V.11 data management software for further analysis.19 The text was read line-by-line to identify meaning units, subthemes and themes. Third, the researchers aimed to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the empirical materials, meaning units and themes, and to relate these to the aim and research question of the metasynthesis.18 The analytic themes were identified by AWL and discussed with GR. The process of deriving the themes was inductive. The contribution of targeted findings from each of the included papers is outlined, and quotations are used to illustrate and support the findings, something which increases the trustworthiness of the study. To validate the findings, both authors participated in discussions of the empirical analysis and in writing up the findings.

Qualitative metasynthesis enables researchers to identify specific research questions, search for, appraise, summarise and combine qualitative evidence to address the research question. Metasynthesis provides novel interpretations of the target findings from the original studies.16 In our methasynthesis we identified two main themes: (1) coping factors within the next of kin themselves and as a support system and (2) coping strategies—control and proactivity, each comprising 3–4 subthemes. For a list of the studies that generated findings regarding the main themes and subthemes, see table 2. When analysing and organising the results into themes and subthemes we chose to be in line with the content and meaning of coping in the original included studies, although some of the results could have been considered to also contributed and organised differently. The results will be elaborated below.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or patient organisations were involved in the planning of the study, the analyses or the writing of the metasynthesis. These were based on published original studies some of which included patient involvement.

Results

The results are presented as metasummaries supported by tables and figures, and as a metasynthesis containing two main themes. The themes are supported by illustrative quotes from the included original studies.

Metasummaries

The 20 studies that were included comprised 342 participants (207 women, 81 men and 54 not classified). The focus was on the following themes: the needs of the next of kin2 20–24; their overall experiences as next of kin10 25–27; coping and coping strategies28–30; postoperative caregiving31 32; being a next of kin in the palliative phase33 34; experienced support factors35; how the caregiving changed over time36 and factors influencing treatment choice in the palliative phase.37 Three of the studies were undertaken 6 months after diagnosis,27 30 31 36 and three in the patients’ palliative phase or postmortem.33 34 37 In six studies the patients were children of the informants.10 29 30 33 34

Metasynthesis

Main theme 1: coping factors within the next of kin and as a support system

Nineteen of the included studies provided data regarding the first main theme; coping factors within the next of kin and as external support (see table 2). This main theme comprised the following four subthemes: personal characteristics, perceiving the role as meaningful, having a support system, and hope and religion.

Personal characteristics such as a strong and positive personality were important coping factors for next of kin in new challenging situations.25 29 37 Being able to show empathy for the patient and the health professionals was important, if not the situation could easily engender feelings such as discouragement and reproach.25 A positive mood and a sense of humour were also emphasised for the same reasons.29

To perceive the role as next of kin as meaningful was important, as it made the next of kin feel needed and productive in the situation.23 25 28 31 Engagement and commitment in the care of their relatives were highlighted as important by many next of kin, especially when the patients appreciated the help.23 The engagement was even stronger when the emotional bond between patient and next of kin was strong.20 21 29 35

But caring for him is something I will do—it is not a burden.31 (p81)

However, other studies revealed less engagement and commitment, and underlined anger and reluctance with the new role as the heavy responsibility and sacrifice impacted the next of kin’s own needs and wishes.21 22 25 31 33

Having a support system made the role of next of kin easier to cope with. The support was given by family, friends, neighbours, colleagues and workplaces, health personnel, schools, the religious community, people in the local community and even strangers.2 10 20–35 The support from healthcare professionals was especially important. This support included emotional support and assistance during patient care and treatment.2 10 20–27 29–35 The importance of assistance such as medical supervision and nursing care was emphasised,10 22 29 with next of kin noting that this made it possible to feel like a partner again,23 while at the same time allowing for anticipated time alone.24 A familiar healthcare professional was crucial in making this possible, because it implied that the patient would receive the best care as they were known to the healthcare professional, and also because the assistance was considered to be less intrusive.23 24 To experience the assistance with care as a coping factor, it was crucial that the care was compassionate and of the best quality. These qualities emphasised the health professionals genuine care and gave the patients and the next of kin hope and a desire to fight the disease.10 21 23 26 27 29

She (neurosurgeon) had to give us some bad news some of the time … and you couldn’t ask for a better manner in her delivery of that bad news, or her support in what we were going through.35 (p8)

When next of kin experienced that their loved ones received a low quality of care or suffered malpractice it caused mistrust of the healthcare system and weakened the experience of healthcare professionals as a support factor.10 20 23 24 Emotional support from healthcare professionals implied an acknowledgement that the disease affected not only the patients, but also their next of kin. It also implied that the healthcare professionals recognised and met the wishes of the next of kin for active participation in monitoring the patients disease course.23 25 26 34 Next of kin who did not have such involvement felt ignored, useless and helpless.25 29 Supportive conversations with healthcare professionals were highly appreciated by many next of kin. However, this required the healthcare professional’s understanding and empathy for the situation of the patient as well as of their next of kin, and preferably that they should be always available.21 23 26 30 31 37

Support from family and friends was invaluable in the care tasks and in coping with the role of next of kin.

Just support from family and friends, that was important to me, and just knowing that I could call on them …22 (p1098)

Social, practical and emotional support was emphasised and included such things as economic help, childcare, transport and housekeeping.10 22 24 25 29–32 34 35 Some next of kin would have appreciated even more support and help from family and friends, preferably given on the family and friends’ own initiative.20 22 24 25 35 36

Discussions with family and friends were also important,21 24 25 27 and could even create a stronger bond.25 Such a bond required families and friends to understand and recognise the challenges faced by the next of kin.24 Support groups and conversations with other next of kin were also highlighted as important,2 22 24 30 34 35 37 as they might broaden the next of kin’s understanding of the tumour and what they might expect in the future.27 These conversations could be face-to-face or via the internet.2 22 24 30 34 35 37

From time to time, I need to be able to talk to someone. Because when I lay down in the evening, then it starts to work in the inside.23 (p411)

On the other hand, support groups were also considered demanding because it was difficult to listen to other families’ stories. Furthermore, for some it was considered a waste of time to spend valuable hours with people other than their closest family members.10 22 31

Hope and religion were emphasised as important coping factors. The next of kin hoped that a miraculous treatment would be developed so that their loved ones could survive the disease or just have a better quality of life.2 10 20–23 26 33 34

You see a positive evolution, and everything that goes better is good for her. (…) Nobody can forbid us to have hope. And miracles happen. Whether we believe it or not, that’s not the point, it is the only thing to focus on.23 (p409)

Hope gave a reason to fight, although it weakened in the palliative phase.21 26 34 Faith strengthened the hope of healing during the treatment period and gave some form of peace in the final palliative phase. In most cases, hope was related to faith.25–27 30 34 37

Main theme 2: coping strategies—control and proactivity

Eighteen of the included studies provided data regarding the second main theme; coping strategies—control and proactivity (see table 2). This main theme comprised three subthemes: regaining control, being proactive and acceptance.

Regaining control of the situation was a frequent coping strategy, and for most this included gathering enough information to allow an overview of what to expect, something which implied some form of security.10 20–23 27 30 35 37

So it’s a, it’s a roller coaster of emotion but for the most part I’ve been, ‘What do we need to do? Where do we need to be?’ And then just read, read, read whatever I can find out, whatever information because I feel like whatever I know, I can ask for.30 (p34)

The information that was gathered and provided should preferably be adapted to the situation and the disease trajectory, and had been given by healthcare professionals.20 22 23 25 27 29 37 The next of kin often hid this information from the patients to protect them and not diminish their hope.10 26 30 31 34

To regain control meant not only control of the diagnosis, but also personal control and control over own reactions. In some cases, the next of kin denied their feelings. Some even denied the entire diagnosis,20 25 29 30 and instead focused on being strong for the patient and the entire family.23 25 30 32–34 36 One next of kin in Edvardsson and Ahlström’s (2008) study25 reported:

I’ve sort of stowed it all away, I suppose. It is as if I’d experienced it from the outside or seen it on TV. It’s often that way with sorrowful things. (p588)

Being proactive, facilitating and encouraging the patient to fight the disease were also important coping strategies, as it felt better than accepting the morbid situation and not do anything.10 21 25 26 34

People ask you how you cope. But what if you were to give up? You’ve got to cope—and we do have each other! (…).25 (p588)

This implied adopting a healthier lifestyle, including a change in diet and exercise habits, hoping that this would improve the effects of medical treatment21 26 or trying alternative treatments.10 34 However, an increasing feeling of powerlessness was emphasised if the fight, in the form of these actions and treatments, did not meet the hope of a cure.21 23 26 34

As the disease progressed and life went on there was a strive for normality, particularly in families with children. This lead most next of kin into a strategy of acceptance, as everyday life continued. This involved work, school for children and hobbies.10 10 26 26 28 28 30 30 31 33 34 34 36 Although this was an important and expected strategy, accepting disease progression or a bad diagnosis was challenging, especially when the patient was a child.34

Discussion

This metasynthesis aimed to explore coping in the role as next of kin of a person with a brain tumour. This generated two main themes: (1) coping factors within the next of kin and as a support system, (2) and coping strategies—control and proactivity. Valuable coping factors included personal characteristics, perceiving the role as next of kin as meaningful, having a support system, and hope and religion. Active strategies to manage the situation involved regaining control, being proactive and acceptance.14 38

Being the next of kin to a person with a brain tumour is considered to be a negative stressor because of the challenging life situation and care tasks. Nevertheless, several next of kin who were included in the metasynthesis expressed a desire to be proactive, fight the disease and to gain control over the situation. This is described by Lazarus and Folkman14 as a secondary assessment of the situation, in which the next of kin decide which measures to implement. One such measure could be to gain personal control—one of the most important and stress-reducing personal strategies available.14

A possible explanation for the proactive attitude of next of kin toward the disease may be their obligation and commitment to the patient. Commitment is an expression of something of great importance and can cause some to be willing to meet threats and challenges that he or she would otherwise avoid.14 However, our findings revealed that the experience of contributing to something meaningful, not the obligation to do so, promoted coping in the situation. We consider that this is caused by the fact that obligation does not automatically make an action meaningful, but rather that it can be experienced as a compulsion. This assumption is strengthened by the findings that the tasks as next of kin may arouse emotions such as anger and aversion towards the patient and the diagnosis, rather than coping. Several studies refer to the same ambivalent experience regarding commitment and attitudes toward being a next of kin.39 40

Having a support system was the factor that most relatives emphasised as promoting coping. It was described as invaluable something which was also confirmed in other studies,41 42 and in Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional stress theory.14 At the same time, in both this metasynthesis and in other studies, next of kin voiced a strong desire and longing for even greater external support.41 42 The findings of the metasynthesis also showed that the configuration and arrangement of the support, especially that given by healthcare providers are of great importance. An explanation for the next of kin’s experience of unmet needs might be lack of knowledge among healthcare providers about how to assist at the right time. This may indicate that in some cases healthcare providers should pay more attention to offering support in line with the individual needs of the next of kin and the care situations.

The findings of this metasynthesis show that several next of kin considered hope to be an important coping factor, especially during the disease trajectory. Hope has also been shown to be a strengthening coping factor in several studies,43 44 and transactional stress theory states that faith and hope are two of the most important personal factors in the cognitive assessment of stressors.14 38 Furthermore, according to Lazarus and Folkman,14 the two factors are strongly related, which is consistent with the findings in our metasynthesis. For several next of kin, hope was strongly grounded in religion. This was especially prominent in the studies conducted in the palliative phase, which indicated that faith is strengthened when there is no hope of curative treatment. The same pattern has also been reported in other studies describing cancer patients’ experiences of palliative care.45 46

As the disease progressed, several next of kin chose an acceptance strategy toward the diagnosis and its burden. Their fight against the disease diminished to some extent, and instead the relatives tried to ‘normalise’ everyday life as much as possible. A similar strategy is also reported by next of kin of other cancer patients, especially in the palliative phase.47 48 Lazarus and Folkman describe this as a reassessment, referring to a changed cognitive assessment of the stressor based on new information from the environment and/or the person himself or herself.14

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this metasynthesis is that the primary search in the databases was conducted with the assistance of an experienced librarian in an attempt to ensure that as many as possible of the relevant studies were included.49 Furthermore, most of the included studies were of high methodological quality (see table 2). Our sample was also highly multicultural (see table 1). This attribute strengthens the validity of the metasynthesis since geographical origin might have affected the study sample because of different participant backgrounds related to different welfare and healthcare systems, cultures and/or religions.

A limitation of our metasynthesis is that one of the 72 articles that was intended to be read in full text could not be obtained.50 The formation of the subthemes is also a possible limitation. Some of the subthemes, or parts of their content, could also have been categorised in the other main theme. Both main themes and subthemes overlap in several cases, and we have read similar studies26 30 where the findings are categorised differently than in our metasynthesis. We chose to be true to the informants’ statements, the organisation and meaning of the original studies that were included, and allocated the findings based on the informants’ way of speaking and description of the experience. Another possible limitation is that our sample consisted mainly of women (see online supplemental material 2). A more heterogeneous sample might have revealed more nuanced findings and different experiences of the role of the next of kin.

Conclusion

The findings of this metasynthesis show that next of kin experience and use a range of coping factors and strategies in their role. Their experience is marked by individual differences. It is of great importance that healthcare providers offer assistance which is individually adapted to these coping factors and strategies because this may reduce stress among the next of kin. The coping experience seems to go through phases, and further information is needed to fully understand how and when the various factors and strategies are used as the disease progresses. Longitudinal studies would therefore be of particular interest in this field.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AWL and GR designed the research project and developed the research plan. AWL was responsible for the literature search, while AWL and GR were responsible for the analysis. Both authors were involved in the screening and inclusion of the studies, reviewed the manuscript, and contributed to the revision of the paper. Both authors read and approved the final version of the paper. The guarantor of the work is GR.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data are secondary analyses from primary qualitative studies.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not required for the study.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund . Worldwide cancer data, 2018. Available: https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/cancer-trends/worldwide-cancer-data

- 2.Arber A, Faithfull S, Plaskota M, et al. A study of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour and their carers: symptoms and access to services. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010;16:24–30. 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.1.46180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voß H, Scholz-Kreisel P, Richter C, et al. Development of screening questions for doctor-patient consultation assessing the quality of life and psychosocial burden of glioma patients: an explorative study. Qual Life Res 2021;30:1513–22. 10.1007/s11136-021-02756-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong TS, Dirven L, Arons D, et al. Glioma patient-reported outcome assessment in clinical care and research: a response assessment in neuro-oncology collaborative report. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:e97–103. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30796-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noll K, King AL, Dirven L, et al. Neurocognition and health-related quality of life among patients with brain tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2022;36:269–82. 10.1016/j.hoc.2021.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rv H, Holt MH, Bjerva J. Dagpost-basert multidisciplinær tilbud for pasienter Med høygradig gliom: første erfaringer ved Senter for kreftbehandling (SFK), Kristiansand. ONKONYTT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Applebaum AJ, Kryza-Lacombe M, Buthorn J, et al. Existential distress among caregivers of patients with brain tumors: a review of the literature. Neurooncol Pract 2016;3:232–44. 10.1093/nop/npv060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng H-M, Chuang D-M, Yang F, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018;97:e11863. 10.1097/MD.0000000000011863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SE, et al. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. CMAJ 2012;184:E373–82. 10.1503/cmaj.111622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell B, Collins A, Dowling A, et al. Predicting distress among people who care for patients living longer with high-grade malignant glioma. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:43–51. 10.1007/s00520-015-2739-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasner M, Paal P, Borasio GD. Psychosocial care for the caregivers of primary malignant brain tumor patients. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2013;9:74–95. 10.1080/15524256.2012.758605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Applebaum AJ, Buda K, Kryza-Lacombe M, et al. Prognostic awareness and communication preferences among caregivers of patients with malignant glioma. Psychooncology 2018;27:817–23. 10.1002/pon.4581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SC, et al. Adjustment and support needs of glioma patients and their relatives: serial interviews. Psychooncology 2013;22:1299–305. 10.1002/pon.3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus RS, Folkman S, Stress FS. Appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crooms RC, Goldstein NE, Diamond EL, et al. Palliative care in high-grade glioma: a review. Brain Sci 2020;10. 10.3390/brainsci10100723. [Epub ahead of print: 13 10 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z. Systematic reviews; 2016. https://rayyan.qcri.org/welcome [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lindseth A, Norberg A. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci 2004;18:145–53. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NVIVO, QSR International , 2020. Available: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- 20.Schubart JR, Kinzie MB, Farace E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro Oncol 2008;10:61–72. 10.1215/15228517-2007-040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piil K, Juhler M, Jakobsen J, et al. Daily life experiences of patients with a high-grade glioma and their caregivers: a longitudinal exploration of rehabilitation and supportive care needs. J Neurosci Nurs 2015;47:271–84. 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janda M, Eakin EG, Bailey L, et al. Supportive care needs of people with brain tumours and their carers. Support Care Cancer 2006;14:1094–103. 10.1007/s00520-006-0074-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coolbrandt A, Sterckx W, Clement P, et al. Family caregivers of patients with a high-grade glioma: a qualitative study of their lived experience and needs related to professional care. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:406–13. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arber A, Hutson N, de Vries K, et al. Finding the right kind of support: a study of carers of those with a primary malignant brain tumour. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:52–8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edvardsson T, Ahlström G. Being the next of kin of a person with a low-grade glioma. Psychooncology 2008;17:584–91. 10.1002/pon.1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wideheim A-K, Edvardsson T, Påhlson A, et al. A family's perspective on living with a highly malignant brain tumor. Cancer Nurs 2002;25:236–44. 10.1097/00002820-200206000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang T-Y, Mu P-F, Chen Y-W. The lived experiences of parents having a child with a brain tumor during the shared decision-making process of treatment. Cancer Nurs 2022;45:201–10. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strang S, Strang P. Spiritual thoughts, coping and 'sense of coherence' in brain tumour patients and their spouses. Palliat Med 2001;15:127–34. 10.1191/026921601670322085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shortman RI, Beringer A, Penn A, et al. The experience of mothers caring for a child with a brain tumour. Child Care Health Dev 2013;39:743–9. 10.1111/cch.12005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cutillo A, Zimmerman K, Davies S, et al. Coping strategies used by caregivers of children with newly diagnosed brain tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2018;23:30–9. 10.3171/2018.7.PEDS18296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmer C, Ward-Smith P, Latham S, et al. When a family member has a malignant brain tumor: the caregiver perspective. J Neurosci Nurs 2008;40:78–84. 10.1097/01376517-200804000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tastan S, Kose G, Iyigun E, et al. Experiences of the relatives of patients undergoing cranial surgery for a brain tumor: a descriptive qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs 2011;43:77–84. 10.1097/jnn.0b013e31820c94da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AEL, et al. Palliative care of children with brain tumors: a parental perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:225–30. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lou H-L, Mu P-F, Wong T-T, et al. A retrospective study of mothers' perspectives of the lived experience of anticipatory loss of a child from a terminal brain tumor. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:298–304. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ownsworth T, Goadby E, Chambers SK. Support after brain tumor means different things: family caregivers' experiences of support and relationship changes. Front Oncol 2015;5:33. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hricik A, Donovan H, Bradley SE, et al. Changes in caregiver perceptions over time in response to providing care for a loved one with a primary malignant brain tumor. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011;38:149–55. 10.1188/11.ONF.149-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipsman N, Skanda A, Kimmelman J, et al. The attitudes of brain cancer patients and their caregivers towards death and dying: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2007;6:7. 10.1186/1472-684X-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazarus RS. Stress OG følelser: en syntese. København: Akademisk Forlag, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin I-F, Fee HR, Wu H-S. Negative and positive caregiving experiences: a closer look at the intersection of gender and relatioships. Fam Relat 2012;61:343–58. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00692.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniela Doulavince A, Altamira PdS R, Regina AGd L. Conceptions of care and feelings of the caregiver of children with cancer/concepções de cuidado E sentimentos do cuidador de crianças CoM câncer. Acta paulista de enfermagem 2013;26:542. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicklin E, Velikova G, Hulme C, et al. Long-term issues and supportive care needs of adolescent and young adult childhood brain tumour survivors and their caregivers: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2019;28:477–87. 10.1002/pon.4989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sterckx W, Coolbrandt A, Dierckx de Casterlé B, et al. The impact of a high-grade glioma on everyday life: a systematic review from the patient's and caregiver's perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:107–17. 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holtslander LF, Duggleby W, Williams AM, et al. The experience of hope for informal caregivers of palliative patients. J Palliat Care 2005;21:285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leite ACAB, Garcia-Vivar C, Neris RR, et al. The experience of hope in families of children and adolescents living with chronic illness: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:3246–62. 10.1111/jan.14129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lina Mahayati S, Allenidekania, Happy H. Spirituality in adolescents with cancer. Enferm Clin 2018;28:31–5. 10.1016/S1130-8621(18)30032-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alidina K, Tettero I. Exploring the therapeutic value of hope in palliative nursing. Palliat Support Care 2010;8:353–8. 10.1017/S1478951510000155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang S-C, Wu L-M, Yang Y-M, et al. The experience of parents living with a child with cancer at the end of life. Eur J Cancer Care 2019;28:e13061. 10.1111/ecc.13061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hisamatsu M, Niwa S. Support factors of coping with anxiety in families of patients with terminal cancer. J Jpn Acad Nurs Sci 2011;31:58–67. 10.5630/jans.31.1_58 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aromataris EM Z, ed. Joanna Briggs Institue Reviewer's Manual, 2017. https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/JBI+Reviewer%27s+Manual [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salander P. Brain tumor as a threat to life and personality: The spouse’s perspective. J Psychosoc Oncol 1996;14:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-052872supp001.pdf (58.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-052872supp002.pdf (77.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data are secondary analyses from primary qualitative studies.