Abstract

Objective

As ‘critical illness’ and ‘critical care’ lack consensus definitions, this study aimed to explore how the concepts’ are used, describe their defining attributes, and propose potential definitions.

Design and methods

We used the Walker and Avant approach to concept analysis. The uses and definitions of the concepts were identified through a scoping review of the literature and an online survey of 114 global clinical experts. We used the Arksey and O’Malley framework for scoping reviews and searched in PubMed and Web of Science with a strategy including terms around critical illness/care and definitions/etymologies limited to publications in English between 1 January 2008 and 1 January 2020. The experts were selected through purposive sampling and snowballing, with 36.8% in Africa, 25.4% in Europe, 22.8% in North America, 10.5% in Asia, 2.6% in South America and 1.8% in Australia. They worked with anaesthesia or intensive care 59.1%, emergency care 15.8%, medicine 9.5%, paediatrics 5.5%, surgery 4.7%, obstetrics and gynaecology 1.6% and other specialties 3.9%. Through content analysis of the data, we extracted codes, categories and themes to determine the concepts’ defining attributes and we proposed potential definitions. To assist understanding, we developed model, related and contrary cases concerning the concepts, we identified antecedents and consequences to the concepts, and defined empirical referents.

Results

Nine and 13 articles were included in the scoping reviews of critical illness and critical care, respectively. A total of 48 codes, 14 categories and 4 themes were identified in the uses and definitions of critical illness and 60 codes, 13 categories and 5 themes for critical care. The defining attributes of critical illness were a high risk of imminent death; vital organ dysfunction; requirement for care to avoid death; and potential reversibility. The defining attributes of critical care were the identification, monitoring and treatment of critical illness; vital organ support; initial and sustained care; any care of critical illness; and specialised human and physical resources. The defining attributes led to our proposed definitions of critical illness as, ‘a state of ill health with vital organ dysfunction, a high risk of imminent death if care is not provided and the potential for reversibility’, and of critical care as, ‘the identification, monitoring and treatment of patients with critical illness through the initial and sustained support of vital organ functions.’

Conclusion

The concepts critical illness and critical care lack consensus definitions and have varied uses. Through concept analysis of uses and definitions in the literature and among experts, we have identified the defining attributes of the concepts and proposed definitions that could aid clinical practice, research and policy-making.

Keywords: adult intensive & critical care, accident & emergency medicine, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This concept analysis is the first study to systematically describe the uses and definitions of the concepts critical illness and critical care.

The study uses a scoping review of the literature and input from over 100 clinical experts from diverse settings globally to identify the defining attributes and provide proposed definitions of the concepts.

Some uses and definitions of the concepts in languages other than English, in unpublished grey literature and from clinical experts not included in the study may have been missed.

As current usage of the concepts is diverse, the proposed definitions may not be universally accepted and are aimed to stimulate further discussion.

Introduction

The concepts critical illness and critical care are commonly used in healthcare. In PubMed, both concepts are Medical Subject Headings terms, and searches for ‘critical illness’ or ‘critical care’ return 40 000 and 220 000 articles, respectively. While it may seem evident that the concepts concern patients with very serious illness and their care, there is a lack of consensus around their precise definitions.

Critical illness is a concept concerning a patient’s condition that is distinct from the disease diagnosis. It has been argued that clinical practice is overly guided by diagnoses rather than prognoses.1 We postulate that the lack of consensus around prognostic concepts such as critical illness may be one factor in this and could cause problems for clinical practice, research and policy-making. For the clinician, discordant interpretations of when a patient is critically ill could lead to differing clinical assessments and treatments despite similar states: for example, Doctor A interprets Patient B’s low blood oxygen level as critical illness, triggers an alarm and admits the patient to an intensive care unit (ICU), only for Doctor C to reverse the decision and discharge the patient as she interprets the illness as non-critical. For the researcher, it could be difficult to design a study or interpret findings: for example, studies into the effect of dexamethasone for critical COVID-19, or of another treatment for all patients with critical illness, require clear eligibility criteria and translating the findings to another patient group requires that the groups have similar clinical conditions. For the policy-maker, prioritising programmes and investments designed to improve care for very sick patients relies on comparisons between similar groups and clearly defined interventions.

Even quantifying the total global burden of critical illness has been challenging due to the lack of an agreed definition.2 Proxies have been used instead, for example, summing up syndromes considered to comprise critical illness such as sepsis and acute lung injury—resulting in estimates of up to 45 million critical illness cases each year.2 Low-income and middle-income countries are suspected to have the highest burden,3 but the lack of a definition has hampered comparisons across settings.4

Studying the care for critically ill patients has also been problematic. Studies have focused on care provided in hospital locations such as in intensive care or emergency units, which exclude both the care provided in hospitals lacking such units, and the care of critically ill patients in general hospital wards.5–7 In the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been great efforts to describe, scale-up and improve care for critically ill patients throughout the world,5 7 and a lack of agreement around the concept of critical care has hampered these efforts.8 9

These examples illustrate how important concepts are as the building blocks of theories and communication. Ideally, concepts are clearly defined and their uses well described for unambiguous communication and an understanding about exactly what is being described or explained.10 Concept analysis is a method for investigating how concepts are used and understood. Concept analyses have been conducted in diverse fields such as in teamwork,11 postoperative recovery12 and bioterrorism preparedness,13 all with the aim of providing basic conceptual understanding and facilitating communication. In this paper, we have used concept analysis, following the stepwise approach described by Walker and Avant.10 The first two steps in the approach are to choose the concept and determine the aim of the analysis. Our chosen concepts are critical illness and critical care and our aims are to explore the uses and definitions of the concepts in published sources and by global clinical experts, leading to a description of the defining attributes of the concepts and to proposed definitions.

Methods

Concepts are the basic building blocks in theory construction, research and communication. A concept analysis aims to define the concept’s attributes and facilitate decisions about which phenomena match the concept, and which do not. In this study, Walker and Avant’s method for concept analysis was chosen as a systematic approach used previously in similar studies.10 The approach consists of eight steps: (1) select the concept; (2) determine the aim of analysis; (3) identify all uses of the concept that you can discover; (4) determine the defining attributes; (5) identify a model case; (6) identify borderline, related, contrary, invented and illegitimate cases; (7) identify antecedents and consequences; (8) define empirical referents. In this paper, steps 1 and 2 are described in the Introduction section, step 3 in the Method section and steps 4–8 in the Results section. Thus, the continuation of this article addresses steps 3–8 in Walker and Avant’s method.10

Step 3: identifying the uses of the concepts

We identified the uses of the concepts of critical illness and critical care through a scoping review of the literature and a web-based survey of global experts.

Scoping review

We used the Arksey and O’Malley framework for scoping reviews.14 Relevant studies published in English between 1 January 2008 and 1 January 2020 were identified in the PubMed and Web of Science databases. We began the search in 2018 and deemed that articles published prior to 2008 were more than 10 years old and would have less relevance. To include publications that were not found through the database searches, we hand-searched publication lists and grey literature of intensive care medicine and emergency medicine societies. Duplicates were removed using the software Rayyan.15 The publications were examined through title, then abstract review and lastly by full-text review. The scoping review protocols were published in advance on the www.protocols.io database.

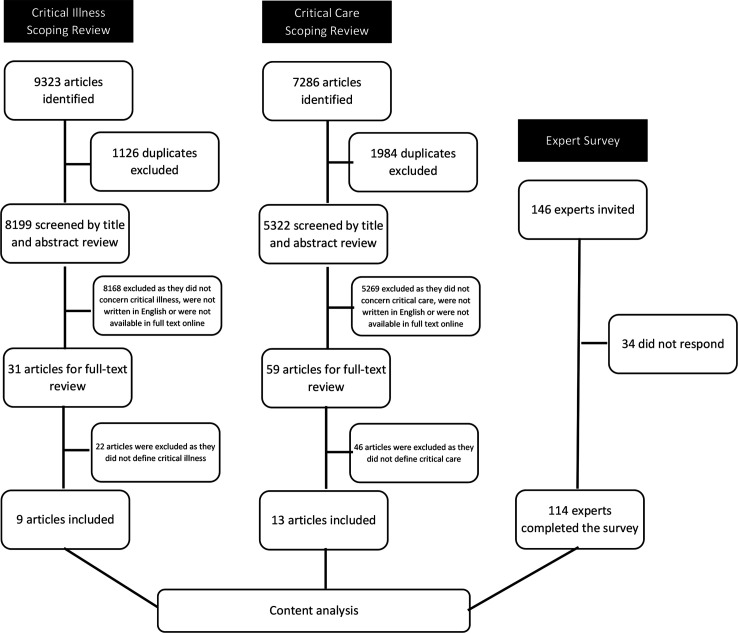

Critical illness

The search strategy used the terms terminolog*, etymolog*, nomenclatur*, OR definition*, AND emergency, critical*, acute*, OR sever*, AND ill OR illness. A total of 9323 articles were identified using these critical illness terms in the databases and an additional two articles were identified through hand searching. Of these, 1126 articles were identified as duplicates and the remaining 8199 articles were screened by title and abstract review by two of the authors (TT and HM). Eight thousand one hundred sixty-eight articles were excluded as they did not concern critical illness, were not written in English or were not available in full text online, leaving 31 articles for inclusion for full-text review. In the full-text review, 22 articles were excluded as they did not define critical illness, and so 9 articles were included in the analysis (figure 1 and online supplemental table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

bmjopen-2022-060972supp001.pdf (53.4KB, pdf)

Critical care

The search strategy used the terms terminolog*, etymolog*, nomenclatur*, OR definition*, AND critical care, intensive care, emergency care, OR acute care. A total of 7286 articles were identified using these critical care terms in the databases and an additional 6 articles were identified through hand searching. Of these, 1964 were identified as duplicates and the remaining 5322 articles were screened by title and abstract review by two of the authors (TT and HM). Five thousand two hundred sixty-nine articles were excluded as they were not concerning critical care, not written in English or not available in full text online, leaving 59 articles for inclusion for full-text review. In the full-text review, 46 articles were excluded as they did not define critical care and so 13 articles were included in the analysis (figure 1 and online supplemental table 2).

bmjopen-2022-060972supp002.pdf (63KB, pdf)

Expert survey

The survey used open-ended questions to gather information about the experts’ definitions of critical illness and critical care, and how they see the relationship of the concepts to connected concepts in order to provide context. The survey included the questions: (1) How would you define critical illness? (2) How would you define critical care? (3) Do critical care and intensive care differ? If yes, in what way? (4) Do critical care and emergency care differ and if yes, in what way? (5) Do critical care and acute care differ and if yes, in what way?

The inclusion criterion for an expert to be invited to participate in the survey was experience in any medical specialty that includes care of patients with acute, severe illness. Experts were identified from a stakeholder mapping of global critical care done by one of the authors (TB, unpublished), and those known to the researchers to be global experts in the field of critical care. Purposive sampling was used to invite experts with the aim of including 100 experts with a balance between specialties, geographical locations, health worker cadres and gender. In total 146 experts were invited to take part, and 114 completed the survey (78% response rate) (figure 1 and table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the experts who participated in the survey

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

| All | 114 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 80 (70.2) |

| Female | 34 (29.8) |

| Continent | |

| Africa | 42 (36.8) |

| Europe | 29 (25.4) |

| North America | 26 (22.8) |

| Asia | 12 (10.5) |

| South America | 3 (2.6) |

| Australia | 2 (1.8) |

| Cadres* | |

| Physician | 93 (53.1) |

| Researcher | 62 (35.4) |

| Nurse | 12 (6.9) |

| Policy-maker | 5 (2.9) |

| Other | 3 (1.7) |

| Specialty* | |

| Anaesthesia/intensive care | 75 (59.1) |

| Emergency care | 20 (15.8) |

| Medicine | 12 (9.5) |

| Paediatrics | 7 (5.5) |

| Surgery | 6 (4.7) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 2 (1.6) |

| Other | 5 (3.9) |

*As the experts were asked to select all that apply, the sum may exceed 100%.

Step 4: analysis and determining the defining attributes

All the definitions and usages of critical illness and critical care from the scoping reviews and the expert survey were charted and analysed using a content analysis based on methods developed by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz.16 First, the data from any parts of the literature and from the expert survey that concerned the uses or definitions of the concepts were extracted. The data were coded, and the codes analysed iteratively by the study team. Repeated and redundant codes were removed and similar codes were arranged into categories. The data were revisited when new categories arose or when diverse opinions with contrasting attributes were identified. Through the process, themes emerged that captured the defining attributes of the concepts. Using the defining attributes, definitions of the concepts were constructed by the research team to be coherent and useful.

Steps 5–8: presenting a model case, related and contrary cases, identifying antecedents and consequences, and defining empirical referents

The model cases, related and contrary cases were developed by the researchers to provide examples to illustrate the defining attributes of the concepts that emerged from the concept analysis. Model cases were developed to be clinically realistic and to include all the defining attributes. Related cases were developed that include some, but not all, of the defining attributes, and contrary cases that are clearly ‘not the concept’, containing none of the defining attributes. For simplicity in this study, we limited our cases to examples of patients with respiratory disease. Antecedents and consequences were identified as events that occur prior to the occurrence of each concept and as the outcomes of each concept, respectively. Empirical referents were identified as phenomena that demonstrate the occurrence of each concept ‘in real life’.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was provided by all of the experts. The Research Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine approved the study (reference number 22661).

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

The results relate to steps 4–8 in the Walker and Avant approach, as steps 1–3 have been described in the Introduction and Methods.

Critical illness

Step 4: the defining attributes

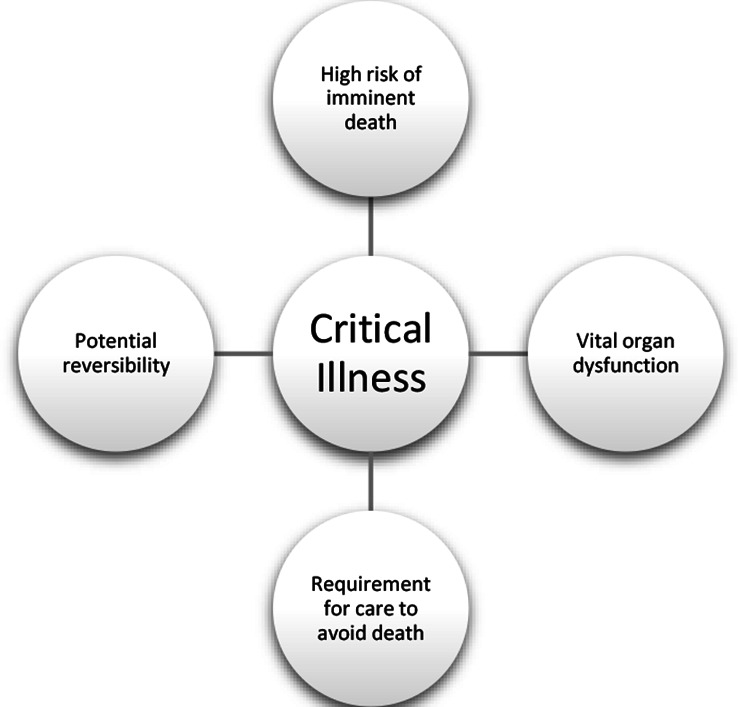

A total of 48 codes were identified from the uses and definitions of critical illness from the scoping review and expert survey. The codes were analysed into 14 categories and 4 themes. (table 2). The themes represent the defining attributes of critical illness: high risk of imminent death; vital organ dysfunction; requirement for care to avoid death; and potential reversibility (figure 2).

Table 2.

Content analysis for the concept critical illness

| Code | Category | Theme |

| Severe illness | Severe illness | High risk of imminent death |

| Process of increasing severity | ||

| Imminent risk of death | High risk of imminent death | |

| Enough severity to lead to death rapidly | ||

| Can kill within a short time | ||

| Medical condition that results in short-term mortality | ||

| Sudden onset illness or acute deterioration | Acute onset or deterioration | |

| Acute life-threatening illness | ||

| An episode of acute illness | ||

| Increased risk of death | Life-threatening | |

| Continuous threat to life and well-being | ||

| Life-threatening or potentially life-threatening disease | ||

| High probability of life-threatening deterioration | ||

| Acutely life-threatening injury or illness | ||

| At least one and often multiple organ dysfunction | Organ dysfunction or failure | Vital organ dysfunction |

| Failure in one or more organ systems that needs support | ||

| Haemodynamic instability, respiratory failure, seizure, disorders of consciousness | ||

| Diseases with vital organ failures as complications | ||

| Threatened organ failure | Threatened organ dysfunction | |

| Potential disturbances of vital organ functions | ||

| Threatened end-organ damage | ||

| Deranged vital parameters | Vital signs derangements | |

| Physiologic reserve is diminished, as manifested by abnormal vital signs | ||

| NEWS2≥7 | ||

| Associated with significant morbidities if untreated | Treatment needed to avoid death | Requirement for care to avoid death |

| Decline in a patient’s ability to survive on their own | ||

| Conditions requiring rapid intervention to avert death or disability | ||

| An illness which without rapid treatment would result in death or disability. | ||

| Needs prompt and sustained intervention to avert death or lifelong disability | ||

| If no intervention is made, death is certain | ||

| Requiring minute-by-minute nursing and/or medical care | Requirement for immediate treatment | |

| Requires a rapid diagnosis and response to ensure good outcomes | ||

| Illnesses where timely care can reduce the chances of death and disability | ||

| Requires immediate intervention | ||

| The illness needs close monitoring and prompt management | ||

| Treatment delays of hours or less make interventions less effective | ||

| Requiring organ support | Requirement for organ support | |

| Requiring vital organ support | ||

| Requiring intensified patient monitoring and organ support | ||

| Critical care services | Requires critical care | |

| ICU admission | ||

| Illness that results in need for more than standard of care | Need for specific care | |

| Acute disease that needs specific treatment alongside the disease itself | ||

| Some element of treatability | Reversible with treatment | Potential reversibility |

| Any treatable life-threatening reversible illness | ||

| Reversible life-threatening organ failure | Potentially reversible | |

| Life-threatening situation, illness or disease that is potentially reversible | ||

| Acute potentially reversible illness |

NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

Figure 2.

The defining attributes of critical illness.

Proposed operational definition

The proposed definition for critical illness is ‘Critical illness is a state of ill health with vital organ dysfunction, a high risk of imminent death if care is not provided and the potential for reversibility’

Cases

Step 5: a model case of critical illness (a case including all the defining attributes)

A woman has a viral pneumonia. She is breathless and hypoxic with a low oxygen level in her blood (oxygen saturation) of 74%. Her lungs are dysfunctional, and she has a life-threatening condition that is likely to lead to her death in the next few hours. She requires care to support her lungs (oxygen therapy) and if she receives that care, she has a chance of recovery.

Step 6: a related case for critical illness (a case including some of the defining attributes but not the attribute of ‘imminently life-threatening’)

A man has a chest infection. He has a fever, is coughing up green sputum and feels short-of-breath when walking. He has an oxygen saturation of 91%. He has a serious condition, but it is not imminently life-threatening. He requires treatment, likely with antibiotics, but it is uncertain whether he requires any organ support such as oxygen. His condition is potentially reversible, and he can recover.

A contrary case for critical illness (a clear example of ‘not the concept’)

A woman has lung cancer. She is coughing up small amounts of blood but is able to walk to the hospital. She has an oxygen saturation of 94%. She is sick and she requires treatment. However, her illness is not imminently life-threatening, she has no dysfunctional vital organ and she does not require immediate care. Her condition may or may not be reversible.

Step 7: antecedents and consequences of critical illness

The antecedents of critical illness are the onset of illness, in mild or moderate form, with progressing severity. The consequences of critical illness are either recovery or death.

Step 8: empirical referents

There are an estimated 30–45 million cases of critical illness globally each year.2 Many patients are cared for in hospitals with illnesses that are causing vital organ dysfunction and that are imminently life-threatening. There is much work done to identify patients with critical illness such as the use of single severely deranged vital signs,17 or compound scoring systems such as the National Early Warning Score and The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score.18 19 In hospitals, the severity of patients’ conditions can be assessed using tools such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation20 and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score.21

Critical care

Step 4: the defining attributes

A total of 60 codes were identified from the definitions of critical care from the scoping review and expert survey. The codes were analysed into 13 categories and 5 themes (table 3). The themes represent the concept’s defining attributes: identification, monitoring, and treatment of critical illness; vital organ support; initial and sustained care; any care of critical illness; and specialised human and physical resources (figure 3).

Table 3.

Content analysis for the concept critical care

| Codes | Category | Theme |

| Identifying and addressing critical illness | Identification and monitoring of critical illness | Identification, monitoring and treatment of critical illness |

| Medical care with timely monitoring | ||

| Appropriate monitoring of critical illness | ||

| Management of critically ill patients | Treatment of critical illness | |

| Treat critical illness | ||

| Care given to the critically ill | ||

| Services required to stabilise critical illness | ||

| Reduce the risk of death from a critical illness | ||

| Care dedicated to patients with severe illness or potentially severe condition | ||

| Managing life-threatening condition | Addressing life-threatening condition | |

| Preventing the occurrence of life-threatening conditions | ||

| Treatment and management due to the threat of imminent deterioration | ||

| Medical care required to reduce the risk to the patient’s life | ||

| Care to sustain cardiopulmonary functions | Supporting vital functions | Vital organ support |

| Support the patient’s haemodynamic or cardiorespiratory status | ||

| Supportive care in critical illness to enable body’s systems to continue functioning before definitive treatment can work | ||

| Care of vital organ failure | ||

| Focus of care on supporting vital organs until improvement | ||

| Providing organ support | Organ support | |

| Main focus on organ-supporting treatment. | ||

| Support of vital organ function, or reverse specific organ dysfunctions | ||

| Supportive care for organs that are failing | ||

| Provision of support to dysfunctional body systems | ||

| Early management for saving and maintaining life | Timely care | Initial and sustained care |

| Rapid and timely intervention that is administered in critical illness | ||

| From admission until the course of illness ends, either in full recovery or death | From start of critical illness until the patient is no longer critically ill | |

| From home through to discharge from hospital | ||

| From the time of first contact with healthcare services through to stabilisation | ||

| To the point where the illness or injury is no longer acutely life-threatening | ||

| Critical care could be over days to weeks | Sustained care | |

| Constant monitoring | ||

| Irrespective of the location of the patient within the health system | Any location | Any care of critical illness |

| Anywhere in the emergency or inpatient setting | ||

| Any care provided to critically ill patients | Any care provided to critically ill patients | |

| Can be specialised care but depends on the level of resources | ||

| Usually located in an area with infrastructure to support these activities | Specific area | Specialised human and physical resources |

| Inside a healthcare facility, outside the emergency department | ||

| High dependency care | ||

| Care in ICU or critical care unit | ||

| A place where equipment, staff and environment is ready to save patients with life-threatening disease | ||

| Multidisciplinary care | Multidisciplinary and specialist staff | |

| Specially trained staff | ||

| Essentially a team based and multiprofessional care | ||

| Requires the grouping of special facilities and specially trained staff | ||

| Higher level of care than is available on a general ward | High-intensity care | |

| Minute-by-minute nursing and/or medical care | ||

| Advanced respiratory support/mechanical ventilation | ||

| Nursing 24/7 | ||

| High nurse: patient ratio no lower than 1:2 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 3.

The defining attributes of critical care.

Proposed operational definition of critical care

The proposed definition for critical care is “Critical care is the identification, monitoring, and treatment of patients with critical illness through the initial and sustained support of vital organ functions.”

Cases

Step 5: a model case of critical care (a case including all the defining attributes)

A woman with a viral pneumonia is rapidly identified as critically ill when she arrives at the hospital. She is immediately admitted to a unit with supplies for managing critically ill patients and treatment is started. Nurses and doctors who have been trained in the care of critical illness monitor her regularly, and provide continuous care, titrating the treatments as needed. Continuous oxygen therapy is provided for her life-threatening hypoxia, supporting her respiratory dysfunction, until she has recovered and is no longer critically ill.

Step 6: a related case of critical care (a case including some of the defining attributes but not the attribute of ‘vital organ support’)

Care in a hospital is provided to a man with a chest infection. A nurse assesses him at arrival to hospital. A doctor admits him to the ward, prescribes antibiotics and decides he is not critically ill and does not require support for any of his vital organs. After 4 days, the doctor discharges him from hospital.

A contrary case of critical care (a clear example of ‘not the concept’)

In the outpatient department, care is provided to a woman with lung cancer. A doctor and a nurse do some investigations and prescribe some medications. She is sent home with a follow-up appointment 2 weeks later.

Step 7: antecedents and consequences of critical care

The antecedents of critical care are the contact of the patient with the healthcare system and may include other care of a patient who has not deteriorated to the point of becoming critically ill. The consequences of critical care are either the patient’s recovery or death.

Step 8: empirical referents

Many hospitals have wards or units for the provision of critical care, such as emergency units, high dependency units or ICUs.22 Critical care can also be provided in general wards, and a recent global consensus specified the care that should be included for all patients with critical illness in any hospital location.23 Rapid Response Teams or Medical Emergency Teams have been introduced into some hospitals, often consisting of staff from the ICU responding to calls from the wards when a critically ill patient has been identified, and providing either critical care on the ward, or transferring the patient to the ICU.24

Discussion

We have described how the concepts critical illness and critical care are used and defined in the literature and by a selection of global experts using a concept analysis approach.

Our proposed definition for critical illness of, “a state of ill health with vital organ dysfunction, a high risk of imminent death if care is not provided and the potential for reversibility”, is similar to those in some key publications. Chandrashekar et al state that, “Critical illness is any condition requiring support of failing vital organ systems without which survival would not be possible”.25 Painter et al write that, “A critically ill or injured patient is defined as one who has an illness or injury impairing one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition”.26 Indeed, we found widespread agreement in the literature and expert sources that critical illness concerns the attributes ‘life-threatening illness’ and ‘organ dysfunction’.

However, we found diverse and varied usage of the concept concerning the attribute of reversibility and the interface between critical illness and the natural process of dying. Some uses included only illness that was potentially reversible—these sources regarded that for critical illness there should be a possible chance of recovery. Without this, critical illness would be a concept that encompasses the dying process—everyone would be critically ill immediately before death—which would conflict with many clinical uses and understandings of the term. Others had a wider interpretation including all life-threatening illness and did not include reversibility in the definition as it is difficult to identify in the clinical setting, and the concept risks becoming context dependent (high-resource interventions may reverse some critical illness which would not be possible in low-resource healthcare). Our iterative content analysis method led to our interpretation that reversibility should be included as one of the defining attributes and to make a distinction between critical illness and illness at the end of life.27 This conclusion should be seen as one possible interpretation that can stimulate further discussion.

It is hoped that the proposed definition of critical illness assists communication in the field. Previously, studies about critical illness have focused on patients in certain hospital units, or with diseases or syndromes as proxies for critical illness that exclude some critically ill patients.2 5 Our definition of critical illness is not diagnosis or syndrome specific and can be due to any underlying condition. The definition could facilitate the specification of clinical criteria for the identification of critical illness, estimates of the overall burden of critical illness, assessments of outcomes for patients with critical illness across centres and settings, and interventions to improve outcomes.

For critical care, there was greater diversity around its use and definition. There was widespread agreement that critical care included the attributes of, ‘care of critically ill patients’, and the ‘support of vital organs’. However, there were differing uses around the location of the care and the need for specialised resources. Some sources considered critical care to be only the care provided in certain locations (such as ICUs or critical care units) or to be care that is always highly specialised or resource intensive. The World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine have suggested that critical care is synonymous with intensive care and is, “a multidisciplinary and interprofessional specialty dedicated to the comprehensive management of patients having, or at risk of developing, acute, life-threatening organ dysfunction. [Critical care] uses an array of technologies that provide support of failing organ systems, particularly the lungs, cardiovascular system, and kidneys.”22 In contrast, other sources used critical care to be inclusive of any care for patients with critical illness, irrespective of location or resources. The Joint Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine of Ireland state that critical care units are those that, “provide life sustaining treatment for critically ill patients with acute organ dysfunction due to potentially reversible disease”,28 and in Belgium, critical care beds have been defined as any beds “for patients with one or more organ functions compromised”4 Hirshon et al strike a balance between these two contrasting views, “[Critical care is] the specialized care of patients whose conditions are life-threatening and who require comprehensive care and constant monitoring, usually in intensive care units.”29

Our proposed definition of, “the identification, monitoring, and treatment of patients with critical illness through the initial and sustained support of vital organ functions”, aims to be inclusive. Critical care may include the use of specialised resources, but it is not a requirement. We see this as a strength in the definition, as it maintains a patient-centred rather than setting-dependent focus. Critical care when defined in this way can be provided anywhere, and does not have to be resource intensive—it includes both high-resource care in ICUs and lower resource care in other settings. Indeed, critical care can be provided in general wards, in small health facilities, in the community or in ambulances. High-resource intensive care may not be possible in low-resource settings, but such settings care for many critically ill patients who require critical care.6 30 31 The proposed definition focuses on supporting vital organ functions, emphasising that critical care’s primary focus is treating the critical condition of the patient rather than definitive care for the underlying condition.9 32 Critical care, as we have defined it, can be seen as a system of care of patients with critical illness throughout the course of their illness, from the time of their first contact with healthcare through to resolution of the critical illness or death. Critical care is part of the wider concept of acute care which also includes prehospital care, emergency care, trauma and surgery care, as well as inpatient care in medical, surgical, paediatric, obstetric and other wards.29

The word ‘crisis’ is the root for the word critical and has its origin from the Greek word ‘krisis’ referring to a ‘turning point’ or ‘act of separation’, and later in English in a medical context when a crisis refers to the decisive point at which a patient either improves or deteriorates.33 The concepts critical illness and critical care could be regarded as remaining true to these origins as they refer to the point in a patient’s ‘journey’ through their illness where they are so severely ill that the situation has become a crisis, and managing the crisis is necessary to direct the patient towards improvement rather than towards deterioration.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study attempting to describe the uses and definitions of the concepts critical illness and critical care, and to identify the defining attributes leading to proposed definitions of the concepts. A strength is the use of both a scoping review of the literature and the inclusion of over one hundred clinical experts as sources. The findings of the analysis should be seen as a first step towards consensus and we recognise that the use of concepts is fluid and changes over time.10 We were limited to including literature in English between 2008 and 2019 and to published studies and guidelines and we may have missed relevant publications in other languages or in other grey literature. Our sample of experts was purposively selected and had global representation but was not perfectly symmetrical to continents, specialty, cadre or gender. There are many more experts than we were able to include, and we are likely to have missed experts who could have provided valuable contributions. Our proposed definitions, while based on a content analysis of scoping reviews and an expert survey, are the outputs of one possible interpretation of the data and may not be universally accepted. We hope our analysis and findings move the conversation forwards, providing input about how to communicate and collaborate around these vitally important concepts, and ultimately how to improve the care and outcomes for critically ill patients.

Conclusion

The concepts critical illness and critical care lack consensus definitions and are used in varied ways in the literature and among global experts. Through a concept analysis of scoping reviews and an expert survey we identify common themes in the uses and understandings of the concepts. We propose definitions for the concepts: “Critical illness is a state of ill health with vital organ dysfunction, a high risk of imminent death if care is not provided and the potential for reversibility” and “Critical care is the identification, monitoring, and treatment of patients with critical illness through the initial and sustained support of vital organ functions.” The proposed definitions could aid clinical practice, research and policy-making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the experts who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @MatsHolmberg9

Contributors: TB and COS designed the study. RKK, TT, HM and TB collected and analysed the data. COS, HMA, MH and MGW contributed to analysing the data. TB is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. RKK and TB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (Reference number 22661). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Croft P, Altman DG, Deeks JJ, et al. The science of clinical practice: disease diagnosis or patient prognosis? Evidence about “what is likely to happen” should shape clinical practice. BMC Med 2015;13:20. 10.1186/s12916-014-0265-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhikari NKJ, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, et al. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010;376:1339–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vukoja M, Riviello ED, Schultz MJ. Critical care outcomes in resource-limited settings. Curr Opin Crit Care 2018;24:421–7. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, et al. Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2787–8. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.African COVID-19 Critical Care Outcomes Study (ACCCOS) Investigators . Patient care and clinical outcomes for patients with COVID-19 infection admitted to African high-care or intensive care units (ACCCOS): a multicentre, prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet 2021;397:1885–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00441-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy S, Leligdowicz A, Adhikari NKJ. Intensive care unit capacity in low-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116949. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arabi YM, Azoulay E, Al-Dorzi HM, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic will change the future of critical care. Intensive Care Med 2021;47:282–91. 10.1007/s00134-021-06352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hvarfner A, Al-Djaber A, Ekström H, et al. Oxygen provision to severely ill COVID-19 patients at the peak of the 2020 pandemic in a Swedish district hospital. PLoS One 2022;17:e0249984. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker T, Schell CO, Petersen DB, et al. Essential care of critical illness must not be forgotten in the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet 2020;395:1253–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30793-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 5th Edition. Pearson, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xyrichis A, Ream E. Teamwork: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2008;61:232–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allvin R, Berg K, Idvall E, et al. Postoperative recovery: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2007;57:552–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebmann T. Defining bioterrorism preparedness for nurses: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2006;54:623–32. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med 2017;7:93–9. 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schell CO, Castegren M, Lugazia E, et al. Severely deranged vital signs as triggers for acute treatment modifications on an intensive care unit in a low-income country. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:313. 10.1186/s13104-015-1275-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis. JAMA 2016;315:762. 10.1001/jama.2016.0288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith GB, Redfern OC, Pimentel MAF, et al. The National early warning score 2 (NEWS2). Clin Med 2019;19:260. 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. Apache II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno RP, Metnitz PGH, Almeida E, et al. SAPS 3--From evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: Development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:1345–55. 10.1007/s00134-005-2763-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall JC, Bosco L, Adhikari NK, et al. What is an intensive care unit? A report of the task force of the world Federation of societies of intensive and critical care medicine. J Crit Care 2017;37:270–6. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schell CO, Khalid K, Wharton-Smith A, et al. Essential emergency and critical care: a consensus among global clinical experts. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006585. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maharaj R, Raffaele I, Wendon J. Rapid response systems: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandrashekar M, Shivaraj BM, Krishna VP. A study on prognostic value of serum cortisol in determining the outcome in the critically ill patients. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences 2015;4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Painter JR. Critical care in the surgical global period. Chest 2013;143:851–5. 10.1378/chest.09-0359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sallnow L, Smith R, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Report of the Lancet Commission on the value of death: bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022;399:837–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02314-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joint Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine of Ireland . National standards for adult critical care services 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirshon JM, Risko N, Calvello EJB, et al. Health systems and services: the role of acute care. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:386–8. 10.2471/BLT.12.112664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prin M, Wunsch H. International comparisons of intensive care. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18:700–6. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835914d5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manda-Taylor L, Mndolo S, Baker T. Critical care in Malawi: the ethics of beneficence and justice. Malawi Med J 2017;29:268. 10.4314/mmj.v29i3.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schell CO, Gerdin Wärnberg M, Hvarfner A, et al. The global need for essential emergency and critical care. Crit Care 2018;22:284. 10.1186/s13054-018-2219-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merriam-Webster . Merriam Webster Dictionary [Internet], 2022. Available: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/crisis [Accessed 11 Apr 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-060972supp001.pdf (53.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-060972supp002.pdf (63KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.