Summary

Hormonal disorders in the menstrual cycle can affect labyrinthine fluid homeostasis, causing balance and hearing dysfunctions.

Study Design

Clinical prospective.

Aim

compare the results from vestibular tests in young women, in the premenstrual and postmenstrual periods.

Materials and Methods

twenty women were selected with ages ranging from 18 to 35 years, who were not using any kind of contraceptive method for at least six months, and without vestibular or hearing complaints. The test was carried out in each subject before and after the menstrual period, respecting the limit of ten days before or after menstruation.

Results

there was a statistically significant difference in the menstrual cycle phases only in the following vestibular tests: calibration, saccadic movements, PRPD and caloric-induced nystagmus. We also noticed that age; a regular menstrual cycle; hearing loss or dizziness cases in the family; and premenstrual symptoms such as tinnitus, headache, sleep disorders, anxiety, nausea and hyperacusis can interfere in the vestibular test.

Conclusion

there are differences in the vestibular tests of healthy women when comparing their pre and postmenstrual periods.

Keywords: hearing, menstrual cycle, electronystagmography, dizziness

INTRODUCTION

Levels of ovarian steroid hormones (estrogen and progesterone) vary according to each phase of the regular menstrual cycle; this variation is controlled by the hypothalamic-hypophyseal-ovarian system.1

The menstrual cycle may be divided into the follicular and luteal phases. The follicular phase (or early follicular or menstrual phase) is characterized by low estrogen and progesterone levels. In the luteal phase (or late luteal or pre-menstrual phase), estrogen and progesterone levels are decreased.2

Most of the changes in women take place in the luteal phase; these changes include fluid retention, weight gain, increased energy demands, changes in glucose uptake, a slower gastrointestinal transit time, altered lipid profiles, altered vitamin D, calcium, magnesium and iron metabolism, emotional hypersensitivity, generalized pain, and changes in dietary habits.3 Other findings in this phase are hydrops of the labyrinth (due to sodium retention and the resulting endolymphatic hypertension) noise intolerance, and an “empty head” feeling.4

Hormone alterations in the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and menopause may compromise the homeostasis of labyrinthic fluids, since they act directly on enzymatic processes and in neurotransmitter effects; these changes may alter balance or hearing.5

A study of premenstrual dizziness has suggested that peripheral vestibular alterations may occur due to fluid retention in the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle6 resulting from increased estrogen, progesterone and aldosterone release.7 Other findings may be vertigo or dizziness a few days before menstruation, due to increased levels of estrogen, progesterone and aldosterone in the inner ear. The effect of such increased hormone levels is hydrops of the labyrinth and symptoms similar to those encountered in Ménière's disease.7

Because of this possible influence of ovarian hormones in different phases of the menstrual cycle on the vestibular function, there has been interest in seeking vestibular signs that might demonstrate such effects.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to verify whether vestibular examination results differed in women during the pre- and postmenstrual period.

METHOD

All participants were informed about the aims of this study and were invited to take part after signing a free informed consent form. This study complied with the principles of ethics in research on human beings contained in the resolution 196/96 (Ministry of Health, 1996) and the guidelines of the Research Ethics Committee (protocol 02/06).

Twenty females aged from 18 to 35 years were selected for this study.

Inclusion criteria were females that:

-

1)

had not used any hormonal contraceptives within the last 6 months;

-

2)

had audibility thresholds from 0.25 kHz to 8 kHz, speech recognition threshold of up to 25 dBHL, and speech recognition of monosyllables of at least 88%.

-

3)

had intact external acoustic meatuses (demonstrated by meatoscopy);

-

4)

had no vestibular complaints, verified by a questionnaire consisting of: identification, otological history, auditory complaints, vestibular complaints, and information about the menstrual cycle.

After confirming the inclusion criteria, vestibular testing was done as follows: Positional Nystagmus Test (PN), Calibration (CAL), Spontaneous Nystagmus Test with Open Eyes (SNOE) and with Close Eyes (SNCE), Semi-spontaneous Nystagmus with Open Eyes (SSNOE), Saccadic Movements (SMs), Pendular Tracking (PT), Optokinetic Nystagmus Test (ON), Damped Pendular Rotating Test (DPRT), and Air Caloric Test (CT) at 42°C and 18°C.

Each participant was asked not to consume chocolate, coffee, black tea, mate, green tea, and alcoholic beverages, and to avoid smoking during the three days before testing.

All tests were recorded in a computer; automatic calculation of gain, latency, precision, and angular velocity of the slow component of nystagmus and all other necessary calculations for each test.

The computer of the digital vectoelectronystagmography device includes a specific software, a lighted bar and an air otocalorimeter (type NGR 07 - Neurograff Eletromedicina Ind. & Com. Ltda).

Audiological testing was done in an acoustically treated booth. An Interacoustics model AC 40 audiometer and TDH 39P Telephonics headphones were used. Acoustic immittance measurements were tested using an Interacoustics model AZ7R immittance testing device.

A 5% significance level was adopted for statistical purposes. The SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software, version 13.0, was used for applying Wilcoxon's signed rank test and Spearman's correlation analysis.

RESULTS

The results of vestibular testing were within normal limits.

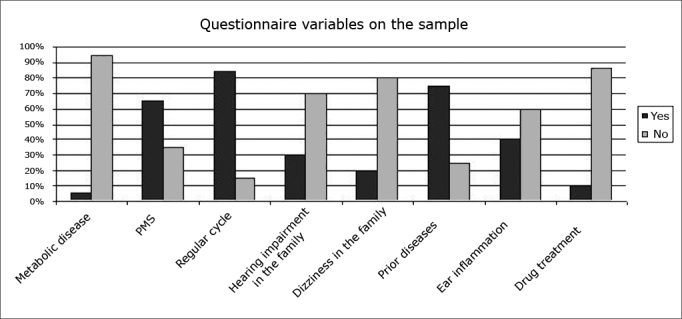

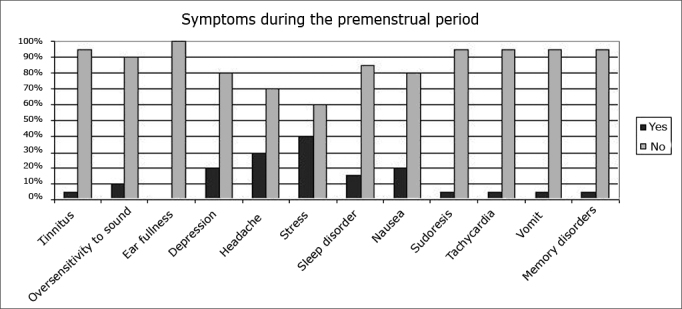

The questionnaire revealed the main variables for characterizing the sample and the symptoms occurring across the menstrual phase of the cycle (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of occurrence of questionnaire variables in the sample.

Figure 2.

Percentage of symptoms occurring during the premenstrual period in the sample.

Wilcoxon's signed rank test demonstrated possible differences between the two points we took into account (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences among the phases of the menstrual cycle in the following tests: CAL latency in the right eye, SM precision in the left eye, DPRT (superior canal) directional preponderance (DPN) of nystagmus, and in CAL, slow component angular velocity (SCAV) at 42°C.

Table 1.

Comparison of results of menstrual cycle phases in vestibular testing.

| Pair of Variables | Mean | Standard deviation | Significance (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAL Latency RE pre | 179,54 | 56,70 | 0,042 * |

| CAL Latency RE post | 148,99 | 35,54 | |

| SM Precision LE pre | 0,98 | 0,11 | 0,048 * |

| SM Precision LE post | 1,06 | 0,19 | |

| DPRT DPNS pre | 0,11 | 0,06 | 0,017 * |

| DPRT DPNS post | 0,15 | 0,08 | |

| CT 42° SCAV RE pre | 5,86 | 1,75 | 0,050 * |

| CT 42° SCAV RE post | 7,12 | 2,89 |

Key:

RE = Right ear

LE = Left ear

CAL = calibration

SMs = Saccadic movements

DPRT = Damped pendular rotation test

DPNS = Directional preponderance of nystagmus of the superior canal

CT = Caloric test

SCAV = Slow component angular velocity

significant p-values in Wilcoxon's signed rank test.

Spearman's correlation analysis showed the relation among questionnaire variables and vestibular test results.

Table 2, Table 3 describe the significant p-values among the questionnaire variables and the symptoms in the menstrual phase, and vestibular tests.

Table 2.

Result of statistically significant p-values in vestibular tests and questionnaire variables, for the pre- and postmenstrual phases.

| Pre-menstrual | Duration of cycle | Deafness in family | Dizziness in family | Previous disease | Treatment with medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAL Velocity | LE = 0,006 | ||||

| SM Latency | LE = 0,019 | ||||

| PT Type | 0,002 | ||||

| ON DPN | 0,008 | 0,023 | |||

| DPRT Velocity PSC | LE = 0,034 | ||||

| DPRT DPNS | 0,025 | ||||

| Postmenstrual | Age | Regulated cycle | Deafness in family | Previous disease | Treatment with medication |

| CAL Latency | LE = 0,004 | ||||

| CAL Velocity | LE = 0,035 | RE = 0,028 | |||

| SM Latency | RE = 0,035 | ||||

| PT 0.40 Hz | 0,027 | ||||

| ON DPN | 0,006 | 0,019 |

Key:

RE = Right ear

LE = Left ear

CAL = calibration

SMs = Saccadic movements

PT = Pendular tracking

ON = Optokinetic nystagmus

DPN = Directional preponderance of nystagmus

DPRT = Damped pendular rotation test

DPNS = Directional preponderance of nystagmus of the superior canal

PSC = Posterior semicircular canal

Table 3.

Result of statistically significant p-values in vestibular tests and pre- and postmenstrual cycle symptoms

| Premenstrual | Tinnitus | Headache | Sleep disorder | Anxiety | Nausea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT Type | 0,013 | ||||

| PT 0.20 Hz | 0,016 | ||||

| PT 0.40 Hz | 0,001 | ||||

| ON SCAV | RE = 0,049 | ||||

| ON Gain | RE = 0,040 | ||||

| DPRT Velocity LSC | RE = 0,038 | ||||

| DPRT Velocity PSC | LE = 0,044 | RE = 0,026 | LE = 0,010 | ||

| DPRT Velocity SSC | RE = 0,049 | LE = 0,012 | RE = 0,038 | ||

| CT SCAV 18° | LE = 0,028 | ||||

| Post-menstrual | Hypersensitivity to loud sounds | Headache | Anxiety | Sleep disorder | Nauseas |

| CAL Precision | RE = 0,009 | ||||

| SM Precision | RE = 0,040 | RE = 0,013 | |||

| LE = 0,009 | |||||

| PT 0.10 Hz | 0,013 | ||||

| PT 0.20 Hz | 0,035 | 0,013 | |||

| PT 0.40 Hz | 0,004 | ||||

| ON SCAV | RE = 0,026 | RE = 0,018 | |||

| LE = 0,027 | LE = 0,013 | ||||

| ON Gain | RE= 0,012 | ||||

| DPRT Velocity PSC | RE = 0,026 | ||||

| LE = 0,013 | |||||

| DPRT Velocity SSC | RE = 0,026 | ||||

| LE = 0,013 | |||||

| DPRT DPNL | 0,021 | ||||

| DPRT DPNS | 0,040 | 0,003 | 0,002 | ||

| CT SCAV 42° | LE = 0,029 | RE = 0,004 | |||

| LE = 0,030 | |||||

| CT SCAV 18° | RE = 0,021 | RE = 0,023 | RE = 0,013 | ||

| LE = 0,006 |

Key:

RE = Right ear

LE = Left ear

CAL = calibration

PT = Pendular tracking

ON = Optokinetic nystagmus

SCAV = Slow component angular velocity

DPN = Directional preponderance of nystagmus

DPRT = Damped pendular rotation test

DPNL = Directional preponderance of nystagmus do canal lateral

DPNS = Directional preponderance of nystagmus of the superior canal

LSC = Lateral semicircular canal

PSC = Posterior semicircular canal

SSC = Superior semicircular canal

SM = Saccadic movements

CT = Caloric test

DISCUSSION

The menstrual cycle may be defined as the interval between the first day of a menstruation and the first day of the next menstruation. Premenstrual tension (PMT) is a set of symptoms that arise between 10 and 14 days before menstruation and disappears after it begins. Over 150 symptoms have been catalogued; their incidence varies and is not constant. When these symptoms become intense to the point of interfering with daily activities, they compose the severe form of PMT, the Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS). PMT affects about 75% of women in the reproductive age.8, 9, 10

A decreased CAL latency and an increased SM precision during the postmenstrual period diverge from the findings of a study11 that monitored two menstrual cycles of 12 subjects and concluded that hormone changes within the cycle had no significant effect on the optokinetic function, and that only lateral postural stability was affected.

It is important to note that estrogen and progesterone levels in the premenstrual phase may affect central nervous system functioning, indirectly altering the optokinetic function. This may occur especially in those areas related to the visual-vestibular interaction, such as GABAA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) receptors, which is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that binds to specific receptors. Progesterone metabolism may modulate these receptors, altering the transmission in the vestibular nuclei that are involved with the optokinetic, vestibuloocular and vestibulospinal reflexes.11

Increased DPN values in the upper semicircular canals in the DPRT test during the postmenstrual phase were statistically significant. We may assume that this occurred due to a possible effect of sex hormones on bodily fluids.12 Thus, as the volume and pressure of endolymph and perilymph increased during the premenstrual phase, stimulation during the test would have a milder effect when we positioned the head for the DPRT of the vertical canals to the right and left.

In the CT at 42°C, an increased postmenstrual SCAV value was also statistically significant. We may assume that this occurred in the premenstrual period because the baseline temperature of the female body increases as a results of increased sexual hormone levels.13 Thus, the effect on the labyrinth would be dampened when stimulating the ear at 42°C in the premenstrual period, compared to the postmenstrual period.

Crossing the questionnaire variables and the symptoms demonstrated in the results of vestibular tests during the premenstrual phase allowed us to raise some hypotheses about such correlations.

Age may affect CAL latency due to the natural reduction of bodily muscle movements and degeneration of hair cells, otoliths, ganglion cells and nerve endings in the peripheral and central vestibular system, all of which may be observed in the elderly.14 The menstrual cycle being regulated or not may affect the CAL velocity; the more regulated the cycle, the more regulated will be the sex hormone levels, which would cause fewer changes in the inner ear.

Cases of deafness and dizziness in the family may suggest a genetic predisposition to develop labyrinthic and cochlear alterations;15 which could also affect the vestibular tests. A history of diseases such as measles and chickenpox, and treatment with certain mediations may affect the results of the CAL velocity and latency, SM latency, PT type and frequency and DPN, ON DPN, and DPRT velocity and DPN, since these are risk factors for the presence of inner ear alterations. Viral diseases may cause endolymphatic labyrinthitis or neuritis of the VIII cranial nerve, which may cause sensorineural hearing loss. Otitis media and medication therapy may injure the base of cochlea.15

Tinnitus, headaches, sleep disorders, anxiety, nausea, and hypersensitivity to sound may alter the vestibular tests (PT type and frequency, ON gain and SCAV, DPRT velocity and DPN, and CT SCAV), since the premenstrual period alters perilymph and endolymph pressure and blood viscosity.12 Additionally, some studies have shown that there are psychic symptoms in the PMS that decrease the concentration ability,16 which also reduces attention during testing.

Female sex hormones thus alter the vestibule physically - changing the endolymphatic pressure - and blood viscosity. The most significant changes, however, are those that result from the effects of progesterone and estrogen on the central nervous system (neurotransmitters and their interactions).

CONCLUSION

Based on these data we concluded that:

In different phases of the menstrual cycle the following tests are altered: CAL, SMs, DPRT and CT SCAV at 42°C.

Footnotes

Paper submitted to the BJORL-SGP (Publishing Management System – Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology) on December 5, 2007; and accepted on January 2, 2008. cod. 5609

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunha F. Porque as mulheres menstruam. Femina. 2003;31(7):627–630. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders D, Warner P, Backström T, Bancroft J. Mood, sexuality, hormones and the menstrual cycle. I - Changes in mood and physical state. Description of subjects and methods. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:487–501. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampaio HAC. Aspectos nutricionais relacionados ao ciclo menstrual. Rev Nutr Campinas. 2002;15(3):309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribeiro KMX, Testa JRG, Weckx LLM. Labirintopatias na mulher. Rev Bras Med. 2000;57(5):456–462. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bittar RSM. Sintomatologia auditiva secundária a ação dos hormônios. Femina. 1999;27(9):739–741. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez MVSG, Caovilla HH, Ganança MM. Tonturas prémenstruais:avaliação otoneurológica. Femina. 1993;21:437–444. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel Nabi EA, Motawee E, Lasheen N, Taha A. A study of vertigo and dizziness in the premenstrual period. J Laryngol Otol. 1984;98:273–275. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100146559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nogueira CW, Silva JLP. Prevalência dos sintomas da síndrome pré-menstrual. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2000;22(6):347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cota AMM, Sousa EBA, Caetano JPJ, Santiago RC, Marinho RM. Tensão pré-menstrual. Femina. 2003;31(10):897–902. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva da CML, Gigante DP, Carret MLV, Fassa AG. Estudo populacional da síndrome pré-menstrual. Rev Saúde Pública. 2006;40(1):47–56. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darlington CL, Ross A, King J, Smith PF. Menstrual cycle effects on postural stability but not optokinetic function. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;307:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres Larrosa T, Pérez L, Guerrero M, Redondo F, Lopez Aguado D. High-frequency audiometry: variations in auditory thresholds in the premenstrual period. Acta otorrinolaryngol esp. 1999;50(8):603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeliin MW, Stillman RD. Otoacoustic emissions in normal-cycling females. J Am Acad Audiol. 1999;10(7):400–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caovilla HH, Ganança MM, Munhoz MSL, Silva da MLG, Ganança FF. In: da Silva MLG, Munhoz MSL, Ganança MM, Caovilla HH, editors. Vol. 3. Atheneu; São Paulo: 2000. Presbivertigem, presbiataxia, presbizumbido e presbiacusia; pp. 153–158. (Quadros clínicos otoneurológicos mais comuns). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginsberg IA, White TP. In: Tratado de audiologia clínica. 4th ed. Katz J, editor. Manole; São Paulo: 1999. Considerações otológicas em audiologia; pp. 6–23. [Google Scholar]

Uncited Reference

- 16.Approbato MS, Silva CDA, Perini GF, Miranda TG, Fonseca TD, de Freitas VC. Síndrome pré-menstrual e desempenho escolar. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2001;23(7):459–462. [Google Scholar]