Abstract

Background/aims:

Efficient recruitment of eligible participants, optimizing time and sample size, is a crucial component in conducting a successful clinical trial. Inefficient participant recruitment can impede study progress, consume staff time and resources, and limit quality and generalizability or the power to assess outcomes. Recruitment for disease prevention trials poses additional challenges because patients are asymptomatic. We evaluated candidates for a disease prevention trial to determine reasons for nonparticipation and to identify factors that can be addressed to improve recruitment efficiency.

Methods:

During 2001–2009, the Tuberculosis Trials Consortium conducted Study 26 (PREVENT TB), a randomized clinical trial at 26 sites in four countries, among persons with latent tuberculosis infection at high risk for tuberculosis disease progression, comparing 3 months of directly observed once-weekly rifapentine plus isoniazid with 9 months of self-administered daily isoniazid. During March 2005–February 2008, non-identifying demographic information, risk factors for experiencing active tuberculosis disease, and reasons for not enrolling were collected from screened patients to facilitate interpretation of trial data, to meet Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials standards, and to evaluate reasons for nonparticipation.

Results:

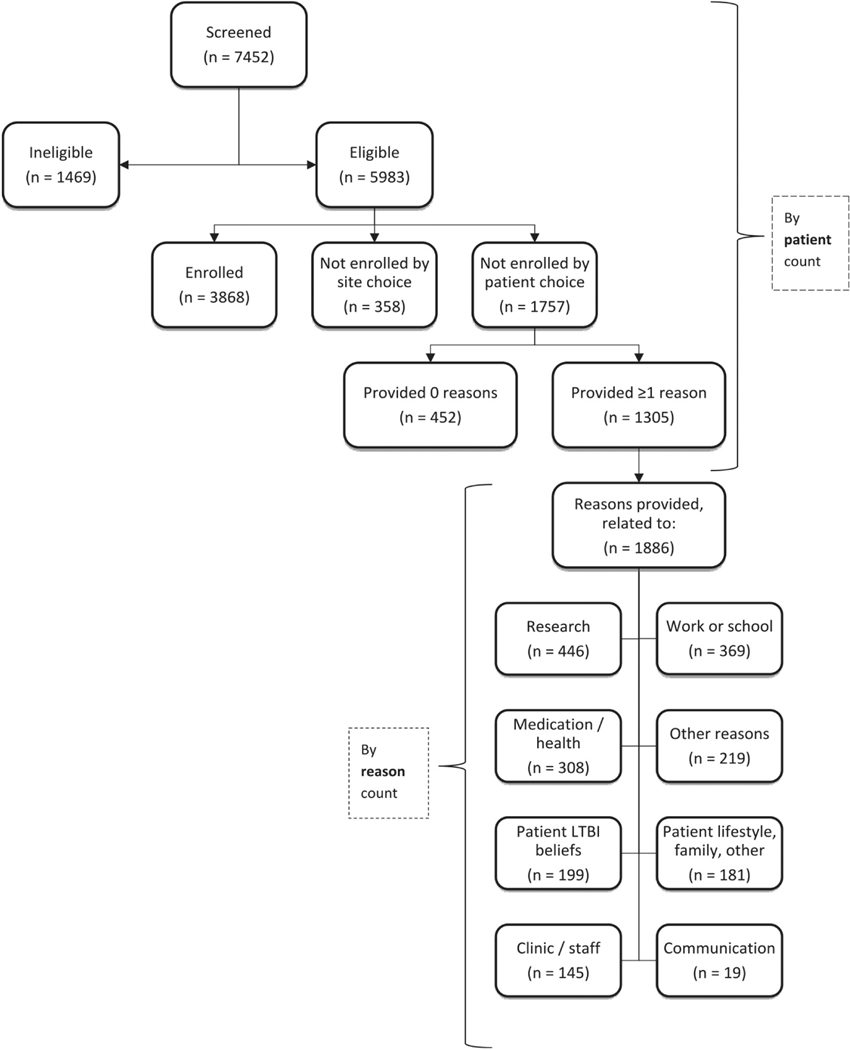

Of the 7452 candidates screened in Brazil, Canada, Spain, and the United States, 3584 (48%) were not enrolled, because of ineligibility (41%), site decision (10%), or patient choice (49%). Among those who did not enroll by own choice, and for whom responses were recorded on whether they would accept treatment outside of the study (n = 1430), 68% reported that they planned to accept non-study latent tuberculosis infection treatment. Among 1305 patients with one or more reported reasons for nonparticipation, study staff recorded a total of 1886 individual reasons (reason count: median = 1/patient; range = 1–9) for why patients chose not to enroll, including grouped concerns about research (24% of 1886), work or school conflicts (20%), medication or health beliefs (16%), latent tuberculosis infection beliefs (11%), and patient lifestyle and family concerns (10%).

Conclusion:

Educational efforts addressing clinical research concerns and beliefs about medication and health, as well as study protocols that accommodate patient-related concerns (e.g. work, school, and lifestyle) might increase willingness to enter clinical trials. Findings from this evaluation can support development of communication and education materials for clinical trial sites at the beginning of a trial to allow study staff to address potential participant concerns during study screening.

Keywords: Latent tuberculosis, clinical trials, patient selection, recruitment

Background/aims

Persons can be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium causing tuberculosis, for years without becoming ill. Treating latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) reduces the risk for progression to disease. Starting in 2000, recommended LTBI treatment in the United States has included 9 months of daily self-administrated isoniazid.1 However, also in 2000, the Institute of Medicine called for shorter, less-toxic treatment options for LTBI among persons at high risk for experiencing active tuberculosis.2 In response to these needs, Tuberculosis Trials Consortium (TBTC) Study 26 (PREVENT TB), a multicenter Phase III LTBI trial, enrolled >8000 persons and found non-inferior efficacy and safety for a 3-month once-weekly combined isoniazid (H) and rifapentine (P) regimen (3HP), given as directly observed therapy, compared to 9 months of H (9H) in prevention of tuberculosis, while demonstrating increased treatment completion rate and decreased hepatotoxicity of 3HP.3Based largely on the results of the PREVENT TB trial, several national and international guidelines have incorporated 3HP as a recommended option for treatment of LTBI.4–6

Recruiting adequate numbers of study participants is vital for a successful trial. Securing patient participation remains a substantial challenge, and slow or inefficient recruitment is costly.7 Low rates of enrollment can result in trial delays, sampling biases, increased costs,8 premature trial termination,9,10 or failure to address the study question. One review of 114 multicenter trials reported that only 31% reached their intended recruitment goal, and another study reported that, in the United States, 34% of trials recruited <75% of their intended sample sizes.10,11 Without a sufficient number of participants, the statistical power of a clinical trial is decreased, which can lead to inconclusive results and difficulties interpreting data.12–15

Clinical trial results are most widely applicable if findings are generalizable and participants are representative of the eventual target patient population. The 2001 and revised 2010 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for reporting of randomized clinical trials stipulate that the characteristics of persons screened but not enrolled should be described.16,17 This allows for more robust interpretation of trial data and recognition of its limitations.16,17 Thorough recording and reporting of challenges to trial recruitment can also help in developing strategies for improving recruitment.

Recruitment for participation in prevention trials, typically involving persons who are asymptomatic, can be particularly challenging. Understanding reasons for nonparticipation in a clinical trial and identifying those that can be addressed might allow investigators to engage persons with similar concerns in future trials. In a previous study, we assessed nonparticipation in a phase 2b trial of a novel tuberculosis therapy for active tuberculosis disease.18 In the present report, we evaluate reasons for nonparticipation in TBTC Study 26 (PREVENT TB), a phase 3 trial of a 12-dose (once-weekly) treatment-shortening regimen for LTBI.3 These two populations offer different perspectives for the reasons for nonparticipation. Patients with active tuberculosis disease are generally symptomatic, require treatment, and receive multiple medications in their treatment. Those with LTBI are asymptomatic, treatment is according to risk of progression, and one to two medications are used. Understanding of specific impediments to recruitment of patients for tuberculosis prevention trials is crucial, as trials for shorter treatments are needed for national and international campaigns for tuberculosis elimination. Some of the results in this study have been previously reported in a presentation to the American Thoracic Society.19

Methods

Setting and participants

TBTC Study 26 was an open-label, randomized, controlled, clinical trial among persons treated for LTBI to prevent active tuberculosis. It compared 3 months of directly observed once-weekly rifapentine plus isoniazid to 9 months of self-administered daily isoniazid.3 Persons were screened for enrollment if they had an LTBI diagnosis and one or more of four factors that increased their risk for developing active tuberculosis disease: household or similar close contact with a person with infectious tuberculosis, recent tuberculin skin test conversion from a negative to a positive result, fibrosis consistent with prior tuberculosis on chest radiograph, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and provided written informed consent were enrolled and randomized at 26 TBTC sites in Brazil (1 site), Canada (3), Spain (1), and the United States (21). The main trial results, including a description of participants, have been published elsewhere.3 This analysis focuses only on the enrollment and non-enrollment data collected during the second half of the trial.

Measures and data analysis

For the present analysis, our outcome was nonparticipation in an LTBI treatment trial, as a proportion of persons screened. Among persons not participating, we studied factors associated with nonparticipation.

During the second half of TBTC Study 26 (March 2005–February 2008), following adoption by the study team of the CONSORT guidelines,16 information was recorded for patients screened but not enrolled. Study staff at TBTC sites were asked to record non-identifying demographic and clinical information in a standardized, internet-based nonparticipation log (see Figure E1 in online data supplement). Study staff screened patients for enrollment who initially appeared eligible. Definitive determination of eligibility required detailed evaluation.3 Nonparticipation reasons were assessed by screening staff, without administering a questionnaire, on the basis of information volunteered by the patient. Screened patients were analyzed in three age groups: 2–17 years, 18–35 years, and ≥36 years. Birthplace was categorized on the basis of World Health Organization regions.20 We also evaluated association of nonparticipation with the tuberculosis risk factors required for eligibility (contact of infectious tuberculosis, tuberculin skin test conversion, HIV infection, and fibrosis on chest radiograph).

We classified each screened but not enrolled patient into one of three primary categories of nonparticipation: (1) ineligibility (failure to meet protocol-specified inclusion or exclusion criteria), (2) site staff choice (e.g. if the patient had a previous history of nonadherence or lived too far away to permit directly observed therapy), or (3) patient choice. More detailed information about patients who were determined to be ineligible or who were not enrolled because of site choice was not collected. However, for the third group (nonparticipation by patient choice), site study staff recorded reasons for nonparticipation for the majority of potential candidates. For each patient, all applicable reasons on a decline log form (Supplemental Figure E1) were reported on the basis of information volunteered at the screening encounter. The reporting form included a space for entering reasons for non-participation other than those available on the form. On review, manually entered reasons were reclassified and counted among the listed reasons when applicable. All nonparticipation data were collected prospectively. Site-specific consent forms for the parent trial were also reviewed for details regarding participant compensation to analyze whether compensation, in US$100 increments, might have been associated with enrollment.

In this secondary analysis, simple frequencies were calculated for sociodemographic data for all screened patients and reasons for nonparticipation. Unadjusted bivariate logistic regression analyses and Wald chi-square tests were used to generate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) to measure association of sociodemographic factors with nonparticipation.21 Missing and unknown values were excluded from analysis. Analyses were conducted with SAS®, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, United States). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Ethics statement

TBTC Study 26 was approved by institutional review boards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Protocol ID 3041) and the other participating institutions. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Study 26: NCT00023452). Implementation of the nonparticipation database was approved by all institutional review boards as part of a protocol amendment.

Results

Study population

During March 2005–February 2008, a total of 7452 candidates were screened for participation in TBTC Study 26 (Figure 1). Table 1 lists selected patient characteristics, classified according to enrolled versus non-enrolled status. Approximately half of screened patients (54.3%) were male and aged ≥36 years (51.2%). Patients were screened at trial sites in Brazil (n = 546; 7%), Canada (n = 420; 6%), Spain (n = 275; 4%), and the United States (n = 6211; 83%). Seventy percent (n = 5192) had been born in the Americas, including 32% (n = 2368) in the United States or Canada. Race was reported for the majority of those screened: 18% (n = 1357) were Asian/Pacific Islanders, 22% (n = 1660) were black, and 53% (n = 3938) were white. Of the patients screened in the United States or Canada (the only countries for this variable), 41% (n = 2732) were of Hispanic ethnicity. Being a contact of a person with infectious tuberculosis was the most frequently reported indication for LTBI treatment, both for the 3868 enrolled participants (n = 2602; 67%) and for the 3584 not enrolled (n = 2115; 59%).

Figure 1.

Overall screened and enrolled versus not enrolled. LTBI = latent tuberculosis infection.

Table I.

Characteristics of patients screened (March 2005-February 2008).

| Total | Total | Enrolled | Ineligible | Eligible but not enrolled, by site or patient choice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| No. (Col %) 7452 | No. (Row %) 3868 (51.9) | No. (Row %) 1469 (19.7) | No. (Row %) 2115 (28.4) | OR (95% Cl) − (−) | |

|

| |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 4046 (54.3) | 2119(52.4) | 791 (19.6) | 1 136 (28.1) | 1.0 (−) |

| Female | 3406 (45.7) | 1749 (51.4) | 678 (19.9) | 979 (28.7) | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) |

| Age group (years)a | |||||

| 2–17 | 757 (10.2) | 480 (63.4) | 101 (13.3) | 176 (23.2) | 1.0 (−) |

| 18–35 | 2878 (38.6) | 1567 (54.4) | 492 (17.1) | 819 (28.5) | 1.43 ( 1.18–1.73)b |

| ≥36 | 3816 (51.2) | 1821 (47.7) | 876 (23.0) | 1 1 19 (29.3) | 1.68 ( 1.39–2.02)b |

| Unknown | 1 (0) | – (−) | – (−) | 1 (100) | – (−) |

| Birthplacec | |||||

| Canada and United States | 2368 (31.8) | 1391 (58.7) | 383 (16.2) | 594 (25.1) | 1.0 (−) |

| Africa | 261 (3.5) | 104 (39.8) | 50 (19.2) | 107 (41.0) | 2.41 ( 1.81–3.21 )b |

| Americas—other | 2824 (37.9) | 1758 (62.3) | 358 (12.7) | 708 (25.1) | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 153 (2.1) | 66 (43.1) | 27 (17.6) | 60 (39.2) | 2.13 ( 1.48–3.06)b |

| Europe | 282 (3.8) | 151 (53.5) | 56 (19.9) | 75 (26.6) | 1.16 (0.87–1.56) |

| South-East Asia | 207 (2.8) | 92 (44.4) | 41 (19.8) | 74 (35.7) | 1.88 ( 1.37–2.6)b |

| Western Pacific | 1008 (13.5) | 303 (30.1) | 418 (41.5) | 287 (28.5) | 2.22 (l.84–2.68)b |

| Non-WHO region | 3 (0) | 2 (66.7) | – (−) | 1 (33.3) | – (−) |

| Unknown | 346 (4.6) | 1 (0.3) | 136 (39.3) | 209 (60.4) | – (−) |

| Screening countryd | |||||

| United States | 6211 (83.3) | 3164 (50.9) | 1324 (21.3) | 1723 (27.7) | 1.0 (−) |

| Brazil | 546 (7.3) | 403 (73.8) | 24 (4.4) | 1 19 (21.8) | 0.54 (0.44–0.67)b |

| Canada | 420 (5.6) | 119 (28.3) | 87 (20.7) | 214 (51.0) | 3.30 (2.62–4.16)b |

| Spain | 275 (3.7) | 182 (66.2) | 34 (12.4) | 59 (21.5) | 0.60 (0.44–0.8)b |

| Racee | |||||

| White | 3938 (52.8) | 2418 (61.4) | 545 (13.8) | 975 (24.8) | 1.0 (−) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 33 (0.4) | 14 (42.4) | 6 (18.2) | 13 (39.4) | 2.30 ( 1.08–4.92)b |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1357 (18.2) | 443 (32.6) | 503 (37.1) | 411 (30.3) | 2.30 (l.97–2.68)b |

| Black | 1660 (22.3) | 878 (52.9) | 280 (16.9) | 502 (30.2) | 1.42 (1.24–l.62)b |

| Other | 124 (1.7) | 98 (79.0) | 14 (11.3) | 12 (9.7) | – (−) |

| Unknown | 340 (4.6) | 17 (5.0) | 121 (35.6) | 202 (59.4) | – (−) |

| Ethnicityf | |||||

| Hispanic | 2732 (36.7) | 1648 (60.3) | 368 (13.5) | 716 (26.2) | 1.0 (−) |

| Non-Hispanic | 3602 (48.3) | 1635 (45.4) | 930 (25.8) | 1037 (28.8) | 1.46 (1.3-1.64)b |

| Non-US/Canadian | 821 (11.0) | 585 (71.3) | 58 (7.1) | – | –(−) |

| Unknown | 297 (4.0) | –(−) | 113 (38.0) | 184 (62.0) | –(−) |

| Indications for LTBI treatmentg | |||||

| Contact | 4717 (63.3) | 2602 (55.2) | 710 (15.1) | 1405 (29.8) | 1.0 (−) |

| Contact and TST converter | 342 (4.6) | 239 (69.9) | 29 (8.5) | 74 (21.6) | 0.57 (0.44–0.75)b |

| TST converter | 1861 (25.0) | 855 (45.9) | 458 (24.6) | 548 (29.4) | 1.19 (1.05–1.35)b |

| Fibrosis | 333 (4.5) | 74 (22.2) | 206 (61.9) | 53 (15.9) | 1.33 (0.93–1.9) |

| HIV-positive | 150 (2.0) | 80 (53.3) | 42 (28.0) | 28(18.7) | 0.65 (0.42–1.0) |

Birthplace: Americas-other (Americas, not Canada or the United States); Cl: confidence interval; fibrosis: fibrosis on chest radiograph; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; LTBI: latent tuberculosis infection; LTBI treatment indications—contact: contact with infectious tuberculosis case; contact and TST converter: contact with infectious tuberculosis case and TST converter; OR: odds ratio; TST: tuberculin skin test; WHO: World Health Organization.

Age group: “Unknown” (total, n = I; not enrolled, n = I): among those not enrolled and not included in univariate analysis.

Logistic regression and Wald chi-square tests were used to generate ORs and 95% CIs, compared not enrolled categories with enrolled. All overall P-values (not shown) for variables were significant except for “Sex: Total”; significant variable categories are indicated with footnoteb.

Birthplace: “Non-WHO Region” (total, n = 3; not enrolled, n = I) and “Unknown” include not reported (total, n = 346; not enrolled, n = 345): not included in univariate analysis.

Screening country: one site only in Canada enrolled (n = 6) and did not provide information about patients who were screened but not enrolled.

Race: “Other” includes multiracial (total, n = 124, not enrolled, n = 26), and “Unknown” includes not reported (total, n = 340; not enrolled, n = 323): not included in univariate analysis.

Ethnicity: for the main PREVENT TB (Sterling et al.3), ethnicity was evaluated only among patients screened in the United States and Canada. “Unknown” includes not reported (total, n = 297; not enrolled, n = 297): not included in univariate analysis.

indications for LTBI treatment: participants who had other combinations of risk factors (n = 49), not shown because of limited numbers.

Demographics of enrolled versus non-enrolled screened patients

The 3584 patients not enrolled were grouped into three categories3: 41% (n = 1469) failed to meet eligibility criteria, 10% (n = 358) were eligible but not enrolled because of site choice, and 49% (n = 1757) were eligible but not enrolled because of patient choice (Table 2). Those not enrolled because of ineligibility were more commonly male, aged ≥36 years, and born in the Western Pacific region. (Note: In the Supplement of the main study, n = 359 were reported as not enrolled because of “Other Reasons” (not enrolled by site choice); however, upon further analysis and data cleaning, one patient was reclassified as “not enrolled by patient’s choice.”)

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients screened: not enrolled by site choice or patient choice.

| Total | Total | Enrolled | lneligible | Not enrolled | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| By site choice | By patient choice | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| No. (Col %) 7452 | No. (Row %) 3868 (51.9) | No. (Row %) 1469 (19.7) | No. (Row %) (Col %) 358 (4.8) | OR (95% Cl) − (−) | No. (Row %) (Col %) 1757 (23.6) | OR (95% Cl) − (−) | |

|

| |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 4046 (54.3) | 2119 (52.4) | 791 (19.6) | 225 (5.6) (62.8) | 1.0 (−) | 911 (22.5) (51.8) | 1.0 (−) |

| Female | 3406 (45.7) | 1749 (51.4) | 678 (19.9) | 133 (3.9) (37.2) | 0.72 (0.57–0.90)b | 846 (24.8) (48.2) | 1.13 ( 1.01–1.26)b |

| Age group (years)a | |||||||

| 2–17 | 757 (10.2) | 480 (63.4) | 101 (13.3) | 29 (3.8) (8.1) | 1.0 (−) | 147 (19.4) (8.4) | 1.0 (−) |

| 18–35 | 2878 (38.6) | 1567 (54.4) | 492 (17.1) | 140 (4.9) (39.1) | 1.48 (0.98–2.23) | 679 (23.6) (38.6) | 1.42(1.15–1.74)b |

| ≥36 | 3816 (51.2) | 1821 (47.7) | 876 (23.0) | 189 (5.0) (52.8) | 1.72 (I.l5–2.57)b | 930 (24.4) (52.9) | 1.67 ( 1.36–2.04)b |

| Unknown | 1 (0) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) (−) | − (−) | 1 (100) (0.1) | − (−) |

| Birthplacec | |||||||

| Canada and United States | 2368 (31.8) | 1391 (58.7) | 383 (16.2) | 125 (5.3) (34.9) | 1.0 (−) | 469 (19.8) (26.7) | 1.0 (−) |

| Africa | 261 (3.5) | 104 (39.8) | 50 (19.2) | 10 (3.8) (2.8) | 1.07 (0.55–2.10) | 97 (37.2) (5.5) | 2.77 (2.06–3.72)b |

| Americas—other | 2824 (37.9) | 1758 (62.3) | 358 (12.7) | 120 (4.2) (33.5) | 0.76 (0.59–0.99)b | 588 (20.8) (33.5) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 153 (2.1) | 66 (43.1) | 27 (17.6) | 29 (19.0) (8.1) | 4.89 (3.05–7.85)b | 31 (20.3) (1.8) | 1.39 (0.9–2.16) |

| Europe | 282 (3.8) | 151 (53.5) | 56 (19.9) | 8 (2.8) (2.2) | 0.59 (0.28–1.23) | 67 (23.8) (3.8) | 1.32 (0.97–1.79) |

| South-East Asia | 207 (2.8) | 92 (44.4) | 41 (19.8) | 7 (3.4) (2.0) | 0.85 (0.38–1.87) | 67 (32.4) (3.8) | 2.16 (1.55–3.01)b |

| Western Pacific | 1008 (13.5) | 303 (30.1) | 418 (41.5) | 34 (3.4) (9.5) | 1.25 (0.84–1.86) | 253 (25.1) (14.4) | 2.48 (2.03–3.02)b |

| Non-WHO region | 3 (0) | 2 (66.7) | − (−) | − (−) (−) | − (−) | 1 (33.3) (0.1) | − (−) |

| Unknown | 346 (4.6) | 1 (0.3) | 136 (39.3) | 25 (7.2) (7.0) | − (−) | 184 (53.2) (10.5) | − (−) |

| Screening countryd | |||||||

| United States | 621 1 (83.3) | 3164 (50.9) | 1324 (21.3) | 304 (4.9) (84.9) | 1.0 (−) | 1419 (22.8) (80.8) | 1.0 (−) |

| Brazil | 546 (7.3) | 403 (73.8) | 24 (4.4) | 8 (1.5) (2.2) | 0.21 (0.1–0.42)b | 111 (20.3) (6.3) | 0.61 (0.49–0.77)b |

| Canada | 420 (5.6) | 119 (28.3) | 87 (20.7) | 15 (3.6) (4.2) | 1.31 (0.76–2.27) | 199 (47.4) (11.3) | 3.73 (2.95–4.72)b |

| Spain | 275 (3.7) | 182 (66.2) | 34 (12.4) | 31 (11.3) (8.7) | 1.77 ( 1.19–2.64)b | 28 (10.2) (1.6) | 0.34 (0.23–0.51)b |

| Racee | |||||||

| White | 3938 (52.8) | 2418 (61.4) | 545 (13.8) | 177 (4.5) (49.4) | 1.0 (−) | 798 (20.3) (45.4) | 1.0 (−) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 33 (0.4) | 14 (42.4) | 6 (18.2) | 6 (18.2) (1.7) | 5.86 (2.22– 15.43)b | 7 (21.2) (0.4) | 1.52 (0.61–3.77) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1357 (18.2) | 443 (32.6) | 503 (37.1) | 55 (4.1) ( 15.4) | 1.70 ( 1.23–2.33)b | 356 (26.2) (20.3) | 2.44 (2.07–2.86)b |

| Black | 1660 (22.3) | 878 (52.9) | 280 (16.9) | 87 (5.2) (24.3) | 1.35 ( 1.04– 1.77)b | 415 (25.0) (23.6) | 1.43 (1.24–1,65)b |

| Other | 124 (1.7) | 98 (79.0) | 14 (11.3) | 3 (2–4) (0.8) | –(−) | 9 (7.3) (0.5) | –(−) |

| Unknown | 340 (4.6) | 17 (5.0) | 121 (35.6) | 30 (8.8) (8.4) | –(−) | 172 (50.6) (9.8) | –(−) |

| Ethnicityf | |||||||

| Hispanic | 2732 (36.7) | 1648 (60.3) | 368 (13.5) | 130 (4.8) (36.3) | 1.0 (−) | 586 (21.4) (33.4) | 1.o(−) |

| Non-Hispanic | 3602 (48.3) | 1635 (45.4) | 930 (25.8) | 173 (4.8) (48.3) | 1.34 (1.06–l.70)b | 864 (24.0) (49.2) | 1.49 (1.31–1.68)b |

| Non-US/Canadian | 821 (11.0) | 585 (71.3) | 58 (7.1) | 39 (4.8) (10.9) | –(−) | 139 (16.9) (7.9) | –(−) |

| Unknown | 297 (4.0) | –(−) | 113 (38.0) | 16 (5.4) (4.5) | –(−) | 168 (56.6) (9.6) | –(−) |

| Indications for LTBI treatmentg | |||||||

| Contact | 4717 (63.3) | 2602 (55.2) | 710 (15.1) | 195 (4.1) (54.5) | 1.0 (−) | 1210 (25.7) (68.9) | 1.0 (−) |

| Contact and TST converter | 342 (4.6) | 239 (69.9) | 29 (8.5) | 18 (5.3) (5.0) | 1.01 (0.61–1.66) | 56 (16.4) (3.2) | 0.50 (0.37–0.68) |

| TST converter | 1861 (25.0) | 855 (45.9) | 458 (24.6) | 122 (6.6) (34.1) | 1.90 ( 1.5–2.42)b | 426 (22.9) (24.2) | 1.07 (0.94–1.23) |

| Fibrosis | 333 (4.5) | 74 (22.2) | 206 (61.9) | 10 (3.0) (2.8) | 1.80 (0.92–3.55) | 43 (12.9) (2.4) | 1.25 (0.85–1.83) |

| HIV-positive | 150 (2.0) | 80 (53.3) | 42 (28.0) | 12 (8.0) (3.4) | 2.00 ( 1.07–3.74)b | 16 (10.7) (0.9) | 0.43 (0.25–0.74) |

Birthplace: Americas-other (Americas, not Canada or the United States); Cl: confidence interval; fibrosis: fibrosis on chest radiograph; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; LTBI: latent tuberculosis infection; LTBI treatment indications—contact: contact with infectious tuberculosis case; contact and TST converter: contact with infectious tuberculosis case and TST converter; OR: odds ratio; TST: tuberculin skin test; WHO: World Health Organization.

Age group: “Unknown” (total, n = I; not enrolled, n = I): among those not enrolled and not included in univariate analysis.

logistic regression and Wald chi-square tests were used to generate ORs and 95% CIs, compared not enrolled categories with enrolled. All overall P-values (not shown) for variables were significant except for “Sex: Total”; significant variable categories are indicated with footnoteb.

Birthplace: “Non-WHO Region” (total, n = 3; not enrolled, n = I) and “Unknown” include not reported (total, n = 346; not enrolled, n = 345): not included in univariate analysis.

Screening country: one site only in Canada enrolled (n = 6) and did not provide information about patients who were screened but not enrolled.

Race: “Other” includes multiracial (total, n = 124, not enrolled, n = 26), and “Unknown” includes not reported (total, n = 340; not enrolled, n = 323): not included in univariate analysis.

Ethnicity: for the main PREVENT TB (Sterling et al.3), ethnicity was evaluated only among patients screened in the United States and Canada. “Unknown” includes not reported (total, n = 297; not enrolled, n = 297): not included in univariate analysis.

indications for LTBI treatment: participants who had other combinations of risk factors (n = 49); not shown because of limited numbers.

Among the 7452 screened patients, 80% (n = 5983) were eligible for participation (Table I). Age was significantly associated with nonparticipation. Compared with those enrolled, nonparticipants were older. The odds of both young adults (aged 18–35 years) and those aged ≥36 years to be nonparticipants were 43% and 68% higher, respectively, (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.18–1.73 and OR = 1.68; 95% CI = 1.39–2.02, respectively) compared with children aged 2–17 years. The country where screening occurred was associated with the likelihood of not enrolling. The odds of potential participants screened in Canada were over three times higher to not participate (OR = 3.30; 95% CI = 2.62–4.16), compared with those screened in the United States. A significant association existed between race and study enrollment. The odds of Asian/Pacific Islanders being non-participants were over two times higher (OR = 2.30; 95% CI = 1.97–2.68), compared with whites. Among those screened in the United States and Canada, nonparticipation was higher among non-Hispanic candidates (OR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.30–1.64), compared with Hispanic candidates.

LTBI treatment indication was significantly associated with nonparticipation in the trial. The odds of potential participants with a recent tuberculin skin test conversion were higher not to participate, compared with those who were recent contacts of a person with infectious tuberculosis (tuberculin skin test converter: OR = 1.19; 95% CI = 1.05–35).

Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and nonparticipation by site choice

Table 2 lists selected patient characteristics, stratified by enrolled versus non-enrolled by site choice and patient choice. Among those not enrolled by site choice, compared with the enrolled population, statistically significant differences were identified. The odds of patients aged ≥36 years were 72% higher (OR = 1.72; 95% CI = 1.15–2.57) not to be enrolled compared to those aged 2–17 years. The odds of non-Hispanics (OR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.06–1.70) not being enrolled due to site choice was 34% higher than Hispanics. Those reported as being HIV-positive were two times higher not to be enrolled (OR = 2.00; 95% CI = 1.07–3.74) by site choice, compared with those who were a contact of a person with infectious tuberculosis.

Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and nonparticipation by patient choice

Compared with the TBTC Study 26 enrolled population, differences were also identified among those not enrolled by patient choice (Table 2). Compared with those screened in the United States, patients screened in Canada were nearly four times higher to decline to participate (OR = 3.73; 95% CI = 2.95–4.72). Screened candidates who had been born in Africa (OR = 2.77; 95% CI = 2.06–3.72), South-East Asia (OR = 2.16; 95% CI = 1.55–3.01), and the Western Pacific region (OR = 2.48; 95% CI = 2.03–3.02) had a higher odds of being non-participants, compared with those born in Canada or the United States. The odds of Asian/Pacific Islanders (OR = 2.44; 95% CI = 2.07–2.86) being nonparticipants was over two times higher, compared with whites.

Reasons for nonparticipation

Table 3 displays reasons volunteered by patients who declined to enroll by patient choice. For the 1757 patients not enrolled by their own choice, 1305 patients were recorded with one or more reasons for not enrolling; 27% (n = 348) of the 1305 patients were recorded with two or more reasons per patient (range = 2–9 reasons per patient). Study staff documented a total of 1886 reasons classified into eight categories for nonparticipation, the most common of which indicated general concerns about engaging in research (24%). The two main concerns about research reported by screened patients declining to enroll were enrolling in any clinical research study and apprehension about the efficacy of the experimental arm. The next most frequently reported concern focused on work or school conflicts (20%), followed by medication or impact to health (16%), LTBI beliefs (11%), and patient lifestyle and family concerns (10%). Concerns about work or school were among the top two categories cited among participants screened at study sites in Brazil, Spain, and the United States. Among all study sites, concern about medication and health ranked second or third. Communication challenges ranked lowest among patient concerns. Approximately one quarter (n = 482; 26%) of the recorded reasons for which patients did not participate were related to the logistics of patients undergoing LTBI therapy. This category was created post hoc by combining reasons under the main categories listed in Table 3 and included the number of visits being inconvenient (n = 212; 11%), the problem of missing work or school (n = 114; 6%), the duration of medication required (n = 42; 2%), and travel to or parking at the clinic being inconvenient (n = 114; 6%).

Table 3.

Reasons patients did not partipate, by reason and count patient.

| Not enrolled because of patient choice, by reason counta | Total | Brazil | Canada | Spain | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No. (Col %) | No. (Col %) | No. (Col %) | No. (Col %) | No. (Col %) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1886 | 167 | 250 | 59 | 1410 | |

|

| |||||

| Research | 446 (23.6) | 56 (33.5) | 34 (13.6) | 7 (11.9) | 349 (24.8) |

| Worried about enrolling in any clinical research studies | 180 (9.5) | 23 ( 13.8) | 3 (1.2) | 5 (8.5) | 149 (10.6) |

| Worried about efficacy of experimental arm | 153 (8.1) | 19 (11.4) | 19 (7.6) | 1 (1.7) | 114 (8.1) |

| Worried about directly observed therapy in one study arm | 93 (4.9) | 13 (7.8) | 12 (4.8) | − (−) | 68 (4.8) |

| Worried about blood draw | 10 (0.5) | − (−) | − (−) | 1 (1.7) | 9 (0.6) |

| Length or complexity of informed consent | 10 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | − (−) | − (−) | 9 (0.6) |

| Work/school | 369 (19.6) | 60 (35.9) | 35 (14.0) | 23 (39.0) | 251 (17.8) |

| Number of visits not convenient | 212 (11.2) | 17 (10.2) | 26 (10.4) | 8 (13.6) | 161 (11.4) |

| Missing work or school could otherwise be a problem | 114 (6.0) | 29 (17.4) | 9 (3.6) | 9 (15.3) | 67 (4.8) |

| Worried about supervisor’s/teacher’s response to missed work/school | 27 (1.4) | 13 (7.8) | − (−) | 5 (8.5) | 9 (0.6) |

| Worried about losing income | 10 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | − (−) | 1 (1.7) | 8 (0.6) |

| Only wants work clearance | 6 (0.3) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 6 (0.4) |

| Medication/health | 308 (16.3) | 38 (22.8) | 39 (15.6) | 15 (25.4) | 216 (15.3) |

| Patient worried about medication side effects | 118 (6.3) | 22 (13.2) | 15 (6.0) | 2 (3.4) | 79 (5.6) |

| Worried about number of pills required per dose | 74 (3.9) | − (−) | 14 (5.6) | 4 (6.8) | 56 (4.0) |

| Worried about impact on other medical problems or medications | 50 (2.7) | 3 (1.8) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (3.4) | 41 (2.9) |

| Worried about duration of medication required | 42 (2.2) | 1 O (6.0) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (8.5) | 26 (1 8) |

| Does not take any medicine in general | 17 (0.9) | 3 (1.8) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (3.4) | 8 (0.6) |

| Primary care or other physician’s concerns about TB in this patient | 7 (0.4) | − (−) | 1 (0.4) | − (−) | 6 (0.4) |

| Other reasons1b | 219 (11.6) | 1 (0.6) | 92 (36.8) | 2 (3.4) | 124 (8.8) |

| Wants regular medication/treatment | 67 (3.6) | − (−) | 59 (23.6) | − (−) | 8 (0.6) |

| Moved/moving | 48 (2.5) | − (−) | 6 (2.4) | − (−) | 42 (3.0) |

| Traveling | 23 (1.2) | − (−) | 9 (3.6) | 2 (3.4) | 12 (0.9) |

| Patient might become or wants to get pregnant or is breastfeeding | 14 (0.7) | − (−) | 3 (1.2) | − (−) | 11 (0.8) |

| Additional ”Other”c | 67 (3.6) | 1 (0.6) | 15 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 51 (3.6) |

| Patient’s LTBI beliefs | 199 (10.6) | 7 (4.2) | 11 (4.4) | 3 (5.1) | 178 (12.6) |

| No risk, of active tuberculosis perceived | 56 (3.0) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (2.4) | 2 (3.4) | 46 (3.3) |

| Infected with TB. but not interested in LTBI/TB therapy | 52 (2.8) | 5 (3.0) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (1 7) | 42 (3.0) |

| BCG caused positive TST | 33 (1.7) | − (−) | 1 (0.4) | − (−) | 32 (2.3) |

| Not infected with TB | 26 (1.4 | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 26 (1.8) |

| Everyone In patient’s country has positive TST; do not need medicine | 20 (1 1) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 20 (1.4) |

| BCG will protect patient from TB | 12 (0.6) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 12 (0.9) |

| Patient lifestyle, family, other | 181 (9.6) | 2 (1.2) | 30 ( 12.0) | 5 (8.S) | 144 (10.2) |

| Family member against enrollment | 98 (5.2) | 2 (1.2) | 19 (7.6) | − (−) | 77 (5.5) |

| Too much stress now | 29 (1.5) | − (−) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (5.1) | 24 (1.7) |

| Worried about use of barrier methods of birth control | 24 (1.3) | − (−) | 5 (2.0) | 1 (1.7) | 18 (1.3) |

| Children or dependents make clinic attendance difficult | 9 (O.5) | − (−) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.7) | 7 (0.5) |

| Worried about stigmatization with TB medicine | 7 (0.4) | − (−) | 3 (1.2) | − (−) | 4 (0.3) |

| Perceived potential conflict with recreational drug use | 5 (0.3) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 5 (0.4) |

| Worried about impact on Immigration status | 5 (0.3) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 5 (0 4) |

| Displeased with recornrnendation not to drink alcohol during TB treatment | 4 (0.2) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 4 (0.3) |

| Clinic/staff | 145 (7.7) | 3 (18) | 5 (2.0) | 4 (6.8) | 133 (9.4) |

| Travel to/parking at clinic not convenient | 114 (6.0) | 3 (1.8) | 5 (2.0) | 2 (3.4) | 104 (7.4) |

| Does not trust information from staff | 12 (0.6) | − (−) | − (−) | 1 (1.7) | 11 (0.8) |

| Has trouble keeping medical appointments in general | 11 (0.6) | − (−) | − (−) | 1 (1.7) | 10 (0.7) |

| Negative interaction with staff | 8 (0.4) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 8 (0.6) |

| Communication | 19 (1 0) | − (−) | 4 (1.6) | − (−) | 15 (1.1) |

| Understands English, but does not understand Study | 10 (0.5) | − (−) | 3 (1.2) | − (−) | 7 (0.5) |

| Unable to communicate for other reasons | 6 (0.3) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | 6 (0.4) |

| Does not understand language available for translation | 3 (0.2) | − (−) | 1 (0.4) | − (−) | 2 (0.1) |

| Not enrolled because of patient choice, by patient count | 1757 | l11 | 199 | 28 | 1419 |

| Recorded with 0 reason (s) for not participating | 452 (25.7) | 8 (7.2) | 28 (14.1) | 5 (17.9) | 411 (29.0) |

| Recorded with ≥ 1 reason(s) for not participating | 1305 (74.3) | 103 (92.8) | 171 (85.9) | 23 (82.1) | 1008 (71.0) |

| Recorded with 1 reason for not participating | 957 (73.3) | 73 (70.9) | 117 (68.4) | 12 (52.2) | 755 (74.9) |

| Recorded with 2 reasons for not participating | 219 (16.8) | 15 (14.6) | 40 (23.4) | 4 (17.4) | 160 ( 15.9) |

| Recorded with 3 reasons for not participating | 79 (6.1 ) | 5 (4.9) | 9 (5.3) | 2 (8.7) | 63 (6.3) |

| Recorded with >3 reasons for not participating (range: 4–9) | 50 (3.8) | 10 (9.7) | 5 (2.9) | 5 (21.7) | 30 (3.0) |

BCG: bacillus Calmette-Guérin; LTBI: latent tuberculosis infection; TB: tuberculosis; TST: tuberculin skin test.

Site staff could record one or more reasons why the patient did not enroll.

Site staff could enter reasons into an open-text field; entries were recorded into existing or new categories.

Additional “Others” included unsure/undecided about treatment plans (n = 9), response unclear (n = 8), lack of documentation (n = 7), patient does not want to take medication (n = 7), current/prior LTBI/TB treatment/therapy/diagnosis (n = 6), prefers alternative therapy/treatment (e.g. with another doctor, medical facility, or different drug regimen) (n = 6), wants same medication as family (n = 6), only wants experimental regimen (n = 4), homeless (n = 3), patient has concerns about randomization (n = 3), error (n = 2), lack of incentive (n = 2), patient does not want to be followed at medical center (n = 2), patient at high risk for hepatotoxicity (n = 1), or religion (n = 1).

Acceptance of treatment outside of study among patients not enrolled

Sixty-nine percent (3868/5625) of screened patients who were eligible and not excluded by site choice actually enrolled in the study. Of the 3584 patients screened but not enrolled, 83% (n = 2989) were recorded with a response on whether they would accept treatment outside the study (Table 4). Of those 2989, 66% (n = 1979) reported that they planned to accept non-study–related LTBI treatment. Among patients who did not enroll by their own choice and for whom responses were recorded regarding non-study–related treatment, 68% (972/1430) indicated they would accept treatment outside of the study. Among those planning to accept non-study–related treatment, the most commonly recorded reasons for nonparticipation were concerns about research (32%), whereas those who did not accept any treatment were most often recorded as not enrolling because of their beliefs about LTBI (35%). Looking at treatment indication, among persons who were screened but not enrolled, 77% of HIV-positive persons, 61% of contacts, 43% of persons with fibrosis, and 28% of tuberculin skin test converters planned to accept treatment for LTBI outside the study (Table 5).

Table 4.

Patients accepting treatment outside of study.

| Total | Yes | No | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No. (Col %) | No. (Row %) (Col %) | No. (Row %) (Col %) | No. (Row %) (Col %) | |

|

| ||||

| Total patients not enrolled because of | 3584 (−) | 1979 (55.2) (−) | 1010 (28.2) (−) | 595 (16.6) (−) |

| Ineligibility | 1469 (41.0) | 742 (50.5) (37.5) | 508 (34.6) (50.3) | 219 (14.9) (36.8) |

| Site choice | 358 (10.0) | 265 (74.0) (13.4) | 44 (12.3) (4.4) | 49 (13.7) (8.2) |

| Patient choice | 1757 (49.0) | 972 (55.3) (49.1) | 458 (26.1) (45.3) | 327 (18.6) (55.0) |

| Total reasons patients did not enroll | 1886 | 1 164 (61.7) (−) | 454 (24.1) (−) | 268 (14.2) (−) |

| Research | 446 (23.6) | 371 (83.2) (31.9) | 40 (9.0) (8.8) | 35 (7.8) (13.1) |

| Work/school | 369 (19.6) | 244 (66.1) (21.0) | 69 (18.7) (15.2) | 56 (15.2) (20.9) |

| Medication/health | 308 (16.3) | 193 (62.7) (16.6) | 74 (24.0) (16.3) | 41 (13.3) (15.3) |

| Other reasons | 219 (11.6) | 148 (67.6) (12.7) | 25 (11.4) (5.5) | 46 (21.0) (17.2) |

| Patient LTBI beliefs | 199 (10.6) | 14 (7.0) (1.2) | 1 60 (80.4) (35.2) | 25 (12.6) (9.3) |

| Patient lifestyle, family, other | 181 (9.6) | 1 19 (65.7) (10.2) | 31 (17.1) (6.8) | 31 (17.1) (11.6) |

| Clinic/staff | 145 (7.7) | 58 (40.0) (5.0) | 55 (37.9) (12.1) | 32 (22.1) (11.9) |

| Communication | 19 (1.0) | 17 (89.5) (1.5) | − (−) (−) | 2 (10.5) (0.7) |

LTBI = latent tuberculosis infection.

Table 5.

Patients accepting treatment outside of study compared to LTBI treatment indication.

| Risk factor a | Total | Yes | No | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3584 | 1979 (55) | 1010 (28) | 595 (17) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No. (Col %) | No. (Row %) (Col %) | No. (Row %) (Col %) | No. (Row %) (Col %) | |

|

| ||||

| Contact | 2115 (59) | 1213 (57) (61) | 604 (29) (60) | 298 (14) (50) |

| Contact and TST converter | 103 (3) | 64 (62) (3) | 19 (18) (2) | 20 (19) (3) |

| TST converter | 1006 (28) | 522 (52) (26) | 247 (25) (24) | 237 (24) (40) |

| Fibrosis | 259 (7) | 112 (43) (6) | 122 (47) (12) | 25 (10) (4) |

| HIV-positive | 70 (2) | 54 (77) (3) | 9 (13) (1) | 7 (10) (1) |

LTBI = latent tuberculosis infection; TST: tuberculin skin test; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

indications for LTBI treatment: participants who had other combinations of risk factors (n = 49), not shown because of limited numbers.

Influence of incentives

Of the 26 sites, 23 sites in Canada (2 sites) and the United States (21 sites) (6277 total participants screened) offered compensation to patients who participated in the study (Supplemental Table E2). Nine sites offered US$100–US$199 to 1708 screened patients, with 29% (n = 495) choosing not to enroll. Four sites offered US$200–US$299 to 833 screened patients, with 40% (n = 330) deciding not to participate. Seven sites offered US$300–US$399 to 1388 screened patients, with 36% (n = 505) declining participation. The amount of compensation did not appear to influence participation.

Discussion

In complying with the guidelines of the CONSORT statement,16,17 study staff implemented a nonparticipation log approximately half-way through TBTC Study 26. This study provided unique, robust data on reasons for nonparticipation in a large LTBI prevention trial that could inform methods to improve recruitment efficiency. Our study demonstrates the feasibility of evaluating specific reasons patients choose not to enroll in a clinical trial. Among LTBI patients screened for the study for whom intentions were recorded and chose to decline to participate, two-thirds planned to accept treatment outside of the trial. When examining the reasons eligible candidates chose not to participate, concerns about research were the primary reason for nonparticipation. Beliefs about LTBI, medications, and health also were common barriers to enrollment. These concerns and beliefs can potentially be addressed and allayed to improve the efficiency of recruitment into a clinical trial.

Interventions such as developing and using targeted educational materials based on the specific findings in this study might help increase patients’ interest in clinical trials, recruitment efficiency, and acceptance of LTBI treatment. In addition to focusing on addressing overall concerns about research, educational efforts should be culturally appropriate; the geographical differences we identified in patient reasons for nonparticipation likely represent cultural and site-specific differences. Differences in beliefs regarding LTBI prevalence, bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination, and risks from treatment or of participation in research are important considerations, and these differences can guide proposed interventions. In one study comparing knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of United States– and foreign-born participants, foreign-born persons were more likely to believe that they were protected from tuberculosis disease without treatment for LTBI. Those authors indicated that that belief is perhaps attributable to prior bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination,22 although Table 3 does not reveal evidence of this belief among our study population. More detailed evaluation of patient knowledge regarding clinical trials research can help guide these efforts. Brintnall-Karabelas et al.23 recommended offering existing educational materials about research and clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health (http://www.nih.gov/health/clinicaltrials/) and ClinicalTrials.gov to participants and investigators.

The two main concerns about research reported by screened patients declining to enroll were enrolling in any clinical research study and apprehension about the efficacy of the experimental arm. The first might be attributed to a lack of knowledge among the patient population about clinical research and its value, as well as insufficiently emphasizing the protections for research subjects, including the right to withdraw, and steps to minimize the burden on subjects. These are potentially amenable to educational interventions. Results similar to our study findings were identified by Brintnall-Karabelas et al.,23 who reported that patients did not enroll primarily because of protocol concerns (similar to concerns regarding research, health, and medication in our analysis), inconvenience, and conflicts with lifestyle (stated as concerns over work, school, and lifestyle in our analysis). Our conclusion supports the feasibility for designing specific, targeted interventions for improving recruitment of subjects for tuberculosis prevention trials. Potentially, trial enrollment efficiency can be improved up to a quarter (24% of patients screened did not enroll because of their own choice in this trial), if the enrolling sites were aware in advance of major reasons for nonparticipation and were prepared to address those reasons with the patients during the screening process.

With 34% of the recorded reasons for patient decline related to potentially modifiable beliefs about LTBI and concerns about research, an opportunity exists for addressing beliefs and possible misconceptions and thus to increase the proportion of screened patients who choose to enroll in clinical trials. Development of specific educational materials about LTBI should address patients’ potential misconceptions. Educational interventions about the risk for experiencing active tuberculosis, including addressing perceptions about differences in risk according to indication for LTBI treatment, can help inform patients about the value of LTBI preventive therapy. In our study, persons born in the Western Pacific, South-East Asia, and Africa regions were two times more likely not to participate than those born in Canada or the United States; culturally appropriate educational materials might help increase participation and the likelihood of a more representative sample in future trials.

Considering indications for LTBI treatment, among persons not enrolled, most with HIV and most contacts indicated that they would accept outside treatment, while minorities of persons with fibrosis and tuberculin skin test converters planned to accept outside treatment. Persons with HIV and contacts might best appreciate the importance of treatment, even when they either are not chosen to participate in research or are themselves skeptical of participating in research. More detailed analysis of these groups might help to develop appropriate targeted interventions to increase recruitment efficiency.

Enrollment and treatment logistics (e.g. the number of visits not being convenient, missing work or school, and concerns about the duration of the treatment and the number of pills per dose) were all recorded as reasons patients chose not to enroll. Allaying concerns about logistics might increase the number of persons treated for LTBI. However, because these barriers were cited less often, these interventions might be less influential. Shorter treatment regimens, simpler modes of administration, fixed dose combination regimens, and flexible research schedules might make treatment more acceptable for patients.

This study had several limitations. Nonparticipation data were not collected until approximately halfway through the trial; as such, this analysis only focused on enrollment and non-enrollment data from that point forward and is not representative of the entire population screened (enrolled and non-enrolled) for TBTC Study 26. However, there is no reason to believe that bias resulted. Therefore, the resulting total sample size of this analysis is about half of what it would have been if nonparticipation data had been collected from the beginning of the clinical trial and raising the possibility that findings might have been different during the first half of the clinical trial. Recruitment of patients was not uniformly distributed across all geographic sites, and enrollment was particularly concentrated in the United States. Differences in language, study staff availability, styles for presenting the study, when and how patients were screened, and social and cultural differences related to staff and patients also existed. Although a standardized form was used to record patients’ reasons for declining, it was completed by site staff only after the patient encounter; therefore, differences among screeners in evaluating patients’ reasons for declining might have yielded inconsistencies. Study candidates were not directly administered questionnaires about participation because this would have required separate informed consent, possibly further reducing the response rate, imposing an extra burden on patients with newly diagnosed LTBI, and possibly introducing response bias into the findings. Bias might have been introduced by staff recording perceived reasons for declining study participation rather than by patients providing such reasons directly, even if anonymously.

Because these factors limit data precision, we did not conduct multivariate analyses. We also did not confirm acceptance of treatment outside of the study for non-participants. Finally, although the amount of compensation available did not seem to influence the rate of patients declining to participate, available data do not support clear conclusion. According to the information abstracted from the site-specific informed consent forms, the majority of sites provided compensation to study participants; however, the methods of compensation administration and amounts were too variable for meaningful analysis of influence on trial participation. Whether screened participants were provided with compensation information before they decided whether to enroll is unknown. Variability in standards-of-living among the sites might also make drawing conclusion on the basis of participant compensation difficult.

This study provides useful information about study participation and about acceptance of standard therapy from a substantial number of persons screened for participation in an LTBI treatment clinical trial. Evaluation and analysis of the reasons for nonparticipation in a clinical trial of treatment for LTBI provides considerable data for guiding development of interventions to increase efficiency of recruitment into subsequent clinical trials. Interventions might differ for study candidates who decline trial enrollment but accept non-study treatment, for whom it might be most effective to focus on concerns related to research, compared to study candidates who decline both trial participation and non-study treatment, for whom it might be most effective to address beliefs about LTBI.

Recent national and international program emphasis on tuberculosis elimination highlights the importance of widespread application of short LTBI treatment regimens and the need to execute more trials in an increasingly efficient manner to further identify even shorter regimens.24 Modeling has demonstrated that LTBI testing and treatment for new immigrants and increased uptake of LTBI screening and treatment among high-risk populations, including the 3-month isoniazid–rifapentine regimen tested in the PREVENT TB trial, would accelerate tuberculosis elimination in the United States, and probably in other countries with low tuberculosis incidence.25 As new, shorter regimens become available, the possibility of eliminating tuberculosis in low-incidence settings could become a reality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the study participants and those screened but not enrolled in TBTC Study 26. The authors would also like to thank the TBTC site staff who contributed their time to this study. In addition, we greatly value the contributions of Pei-Jean Feng and Erin Sizemore for their outstanding statistical and epidemiologic support. We appreciate the technical and editorial review provided by Andrew Vernon and C. Kay Smith.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding support for this trial was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. Sanofi (Paris, France, and Bridgewater, NJ, United States) donated rifapentine and provided funding support for pharmacokinetic testing. From 2007 until 2016, Sanofi donated a total of US$2.9 million to the CDC Foundation to supplement CDC funding for rifapentine research; these funds provided salary support for KNCH and NAS from 2013 to 2017.

Footnotes

Clinical trials registration

The main trial, TBTC Study 26-PREVENT TB, was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Study 26: NCT00023452).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Sanofi commercial interests did not influence the study design; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the preparation of this article; or the decision to submit this article for publication.

Disclaimer

The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161: S221–S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Ending neglect: the elimination of tuberculosis in the United States. (ed Geiter L). Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, et al. Threemonths of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 2155–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borisov AS, BamrahMorris S, Njie GJ, et al. Update of recommendations for use of once-weekly isoniazid-rifapentine regimen to treat latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(25): 723–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Latent tuberculosis infection: updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for use of an isoniazid-rifapentine regimen with direct observation to treat latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60(48): 1650–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gul RB and Ali PA. Clinical trials: the challenge ofrecruitment and retention of participants. J Clin Nurs 2010; 19(1–2): 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams B, Irvine L, McGinnis AR, et al. When “no”might not quite mean “no”; the importance of informed and meaningful non-consent: results from a survey of individuals refusing participation in a health-related research project. BMC Health Serv Res 2007; 7: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardez-Pereira S, Lopes RD, Carrion MJM, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and predictors of early termination of cardiovascular clinical trials due to low recruitment: insights from the ClinicalTrials.gov registry. Am Heart J 2014; 168(2): 213–219.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, et al. What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials 2006; 7: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlson ME and Horwitz RI. Applying results of randomised trials to clinical practice: impact of losses before randomisation. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984; 289(6454): 1281–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Easterbrook PJ and Matthews DR. Fate of research studies. J R Soc Med 1992; 85: 71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holden G, Rosenberg G, Barker K, et al. The recruitmentof research participants: a review. Soc Work Health Care 1993; 19: 1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunninghake DB, Darby CA and Probstfield JL. Recruitment experience in clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials 1987; 8(4 Suppl.): 6S–30S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sood A, Prasad K, Chhatwani L, et al. Patients’ attitudes and preferences about participation and recruitment strategies in clinical trials. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84(3): 243–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, et al. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152: 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamunu D, Chapman KN, Nsubuga P, et al. Reasons for non-participation in an international multicenter trial of a new drug for tuberculosis treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012; 16(4): 480–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman KN, Borisov AS, Hecker EJ, et al. Reasons for non-participation in an international multicenter trial of a new regimen for latent tuberculosis infection. San Francisco, CA: American Thoracic Society and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Strategies for TB Control, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. WHO regional offices. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018, http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/index.html (2018, accessed 6 December 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M and Pryor ER. Logistic regression: a self-learning text (Statistics in the health sciences). 3rd ed. New York: Springer, 2010, p. xvii, 701. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colson PW, Franks J, Sondengam R, et al. Tuberculosis knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in foreign-born and US-born patients with latent tuberculosis infection. J Immigr Minor Health 2010; 12(6): 859–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brintnall-Karabelas J, Sung S, Cadman ME, et al. Improving recruitment in clinical trials: why eligible participants decline. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2011; 6(1): 69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill AN, Becerra J and Castro KG. Modelling tuberculosis trends in the USA. Epidemiol Infect 2012; 140(10): 1862–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menzies NA, Cohen T, Hill AN, et al. Prospects for tuberculosis elimination in the United States: results of a transmission dynamic model. Am J Epidemiol 2018; 187: 2011–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.