Abstract

A 5-mm diameter mass developed on the nasal planum of a 4.5-y-old castrated male domestic shorthaired cat; the mass was raised ~2 mm above the surrounding skin. Histology revealed focal thickening of the epidermis with marked orthokeratosis. Many of the epidermal cells within the mass had prominent papillomavirus-induced changes. A diagnosis of a viral papilloma was made, and a DNA sequence from a novel papillomavirus type was amplified from the lesion. Although the sequence was most similar to other feline papillomavirus types, the low level of similarity was suggestive of a novel papillomavirus genus. There has been no recurrence of the mass or development of additional lesions in the 6 mo since the mass was removed. This is the third cutaneous papilloma reported in a cat; a putative feline papillomavirus type has not been identified previously within these lesions, to our knowledge. Our findings expand the range of lesions associated with papillomaviruses in cats and increase the number of papillomavirus types that infect cats.

Keywords: cats, feline papillomavirus, skin, viral papilloma, warts

To date, there are 6 fully sequenced and classified Felis catus papillomavirus (FcaPV; Papillomaviridae) types that infect domestic cats. These FcaPVs are mainly associated with neoplastic diseases, including cutaneous viral plaques, bowenoid in situ carcinoma (BISC), and a subset of squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, eyelids, and mouth. 9 Although there are numerous reports of FcaPVs causing neoplastic lesions, there are only 4 reports of papillomas (warts) in cats.3,6,7,11 Oral papillomas in cats are considered to be caused by FcaPV1,6,11 but none of the 6 FcaPV types have been detected in cutaneous papillomas from cats.3,7 We describe here a cutaneous virally induced papilloma from a cat that contained a DNA sequence from a putative novel feline PV type.

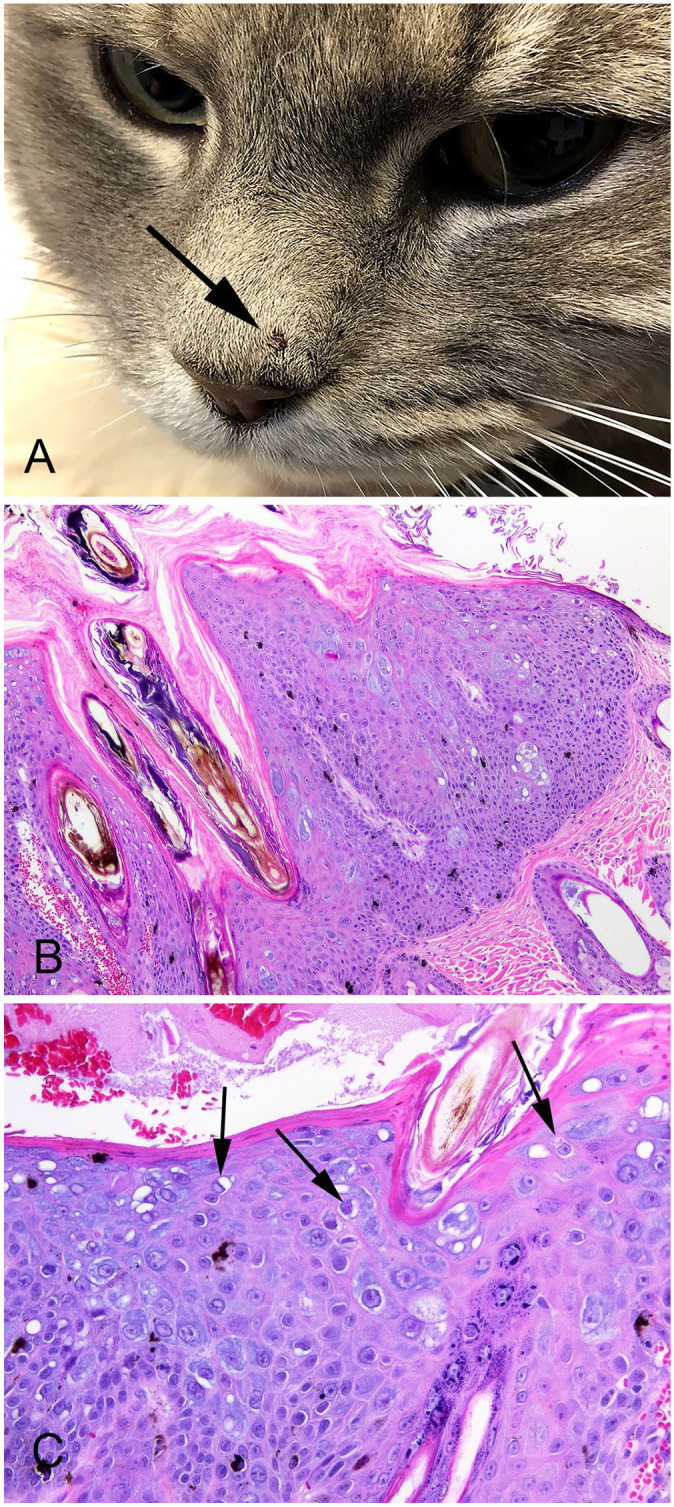

A 4.5-y-old castrated male domestic shorthaired cat was presented at a veterinary clinic for a 5-mm diameter brown mass on the nasal planum that was raised ~2 mm above the surrounding skin (Fig. 1A). The mass had first been observed 4 mo previously and had increased and decreased in size, but not fully resolved. The mass was excised surgically using a biopsy punch and submitted for histologic examination. The mass has not recurred 6 mo after surgical excision, and the cat has not developed any additional skin lesions.

Figure 1.

Feline nasal planum papilloma associated with a novel papillomavirus sequence. A. The brown, 5-mm diameter mass is well defined and raised ~2 mm above the surrounding epidermis (arrow). B. The papilloma consists of a well-demarcated focus of marked epidermal hyperplasia, with orthokeratosis. Large numbers of cells have cytoplasm that is markedly expanded by blue wispy or amorphous material. Cells containing melanin are also prominent within the thickened epidermis. H&E. 100×. C. Cells in the superficial layers of the papilloma are enlarged with irregularly shaped nuclei surrounded by a clear cytoplasmic halo (koilocytes; arrows). Keratohyalin clumping is also present within the papilloma. H&E. 400×.

Histologically, the mass consisted of a well-demarcated focus of markedly thickened epidermis, with marked orthokeratosis, that surrounded and entrapped hair shafts (Fig. 1B). The epithelium of follicular infundibula was mildly thickened; deeper regions of hair follicles were not affected. A prominent feature visible within the lesion was a large number of epidermal cells with cytoplasm that was expanded markedly by wispy or vacuolated lightly basophilic material. Other cells within the superficial layers of the papilloma were enlarged and contained dark irregular nuclei that were surrounded by a clear cytoplasmic halo (koilocytosis; Fig. 1C). Additionally, clumping of keratohyalin granules and cells containing melanin were visible within the affected epidermis. Although many cells contained large eosinophilic intranuclear bodies, whether these represented viral inclusions or nucleoli was uncertain.

DNA was extracted from a central part of the mass (NucleoSpin DNA FFPE XS kit; Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the FAP59/64, MY09/11, and CP4/5 consensus PCR primers were used to amplify PV DNA. 6 DNA extracted from a viral plaque containing FcaPV2, an oral in situ carcinoma containing FcaPV3, and an oral papilloma containing FcaPV1 were used as positive controls for the FAP59/64, MY09/11, and CP4/5 primers, respectively. Although DNA was amplified from positive controls as expected, DNA was only amplified from the feline skin papilloma by the MY09/11 primers. A 378-bp sequence of DNA was compared to other sequences in GenBank using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The sequence was most similar to FcaPV5; however, the sequence was only 61.5% similar over the 378-bp length. In comparison, the sequence was 60.1%, 58.4%, 58.1%, 57.4%, and 57.3% similar to FcaPV4, FcaPV6, FcaPV3, FcaPV1, and FcaPV2, respectively. The sequence was submitted to GenBank (ON017788).

This is the third report of a papilloma from the skin of a cat. In the cases reported previously, one papilloma developed on the eyelid whereas the other, as in our case, developed on the nasal planum.3,7 There was no detailed histologic description of the eyelid papilloma. However, consistent with our case, PV-induced cell changes and orthokeratosis were prominent features within the papilloma reported from the nasal planum. 7 Interestingly, neither the clumped keratohyalin granules nor melanin-containing epidermal cells were reported in the previous case, 7 suggesting that these features are variably present in papillomas.

The lesion in our case was classified as a viral papilloma rather than a viral plaque or BISC. Although viral plaques can contain large numbers of cells with prominent virally induced changes, the small degree of epidermal thickening within viral plaques results in a sessile lesion.9,12 In contrast, the marked epidermal thickening in our case resulted in an exophytic mass. Marked thickening of the epidermis can be present in a BISC, and these lesions can appear as raised masses. 5 However, in contrast to the papilloma in our case that contained a bland, well-differentiated population of cells, BISCs are characterized by evidence of neoplastic transformation including crowding of basal cells, loss of nuclear polarity, and loss of normal maturation of the epidermal cells.8,12 Additionally, although PV-induced cell changes can be present in BISCs, these changes tend to be rare, especially in larger neoplasms.8,12

A novel PV DNA sequence was amplified from the papilloma. Given that this sequence had the highest similarity to other FcaPV types, it is most likely from a previously undetected FcaPV type. It is not possible to definitively classify PVs without sequencing the entire L1 ORF. 2 However, because the novel sequence was only ~60% similar to the sequences of other FcaPV types, the PV appears likely to be from a different genus. 2 Currently, 3 genera of FcaPVs are recognized 9 ; the new sequence suggests that a fourth genus of PVs may be able to infect domestic cats.

PCR was used to detect PV DNA in 1 of the 2 feline skin papillomas described previously; the FAP59/64 primers amplified a DNA sequence from a human PV type. 7 PVs are typically highly species specific and, given that humans are ubiquitously and asymptomatically infected by PVs, 1 contamination of the sample during sampling or processing may be most likely. It should be noted that the FAP59/64 primers did not amplify the novel PV sequence from the papilloma in our case. Because the MY09/11 primers were not used in the previous report, 7 the novel PV sequence could have been present, but undetected.

Coinfections by multiple PV types have been reported in papillomas in other species, and it therefore may be difficult to determine the causative PV type within a papilloma. 4 In our case, coinfection by FcaPV1 could be excluded because no DNA was amplified by the CP4/5 primers, which are known to amplify FcaPV1 DNA. 6 Furthermore, infection by FcaPV1 causes characteristic cytoplasmic inclusions that were not visible in the papilloma in our case. 6 The virally induced cytopathic changes in the cells in the papilloma in our case were similar to those caused by FcaPV2 infection. 9 However, no DNA was amplified by the FAP59/64 primers, which are known to amplify sequences from FcaPV2. Coinfection by FcaPV3, 4, or 5 was also considered unlikely given the lack of DNA amplified by the CP4/5 primers and by the absence of intracytoplasmic bodies that are often seen as a result of infections by these viral types. 9 Overall, although additional cases are required, the molecular findings and the histologic features suggest that the papilloma was caused by a novel FcaPV type.

Given that papillomas have been reported very rarely in cats, and because the PV type within the papilloma in our case has not been reported previously, infection of cats by this PV type appears to be very uncommon. However, the described papilloma remained small and did not appear to irritate the cat. In other species, virally induced papillomas almost always resolve spontaneously, usually within 6 mo of first being observed. 10 If the same is true for cutaneous papillomas in cats, these lesions could occur more frequently than currently recognized, but resolve spontaneously before they become large enough for owners to seek veterinary advice.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: John S. Munday  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4769-5247

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4769-5247

Contributor Information

John S. Munday, School of Veterinary Science, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Anthony K. Wong, Wellington SPCA, Wellington, New Zealand

Alan F. Julian, Idexx Laboratories NZ, Hamilton, New Zealand

References

- 1. Antonsson A, et al. The ubiquity and impressive genomic diversity of human skin papillomaviruses suggest a commensalic nature of these viruses. J Virol 2000;74:11636–11641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernard H-U, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 2010;401:70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carpenter JL, et al. Cutaneous xanthogranuloma and viral papilloma on an eyelid of a cat. Vet Dermatol 1992;3:187–190. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daudt C, et al. How many papillomavirus species can go un- detected in papilloma lesions? Sci Rep 2016;6:36480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munday JS, et al. Bowenoid in situ carcinomas in two Devon Rex cats: evidence of unusually aggressive neoplasm behaviour in this breed and detection of papillomaviral gene expression in primary and metastatic lesions. Vet Dermatol 2016;27:215-e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munday JS, et al. Oral papillomas associated with Felis catus papillomavirus type 1 in 2 domestic cats. Vet Pathol 2015;52:1187–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munday JS, et al. Feline cutaneous viral papilloma associated with human papillomavirus type 9. Vet Pathol 2007;44:924–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Munday JS, et al. Detection of papillomaviral sequences in feline Bowenoid in situ carcinoma using consensus primers. Vet Dermatol 2007;18:241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Munday JS, Thomson NA. Papillomaviruses in domestic cats. Viruses 2021;13:1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sancak A, et al. Antibody titres against canine papillomavirus 1 peak around clinical regression in naturally occurring oral papillomatosis. Vet Dermatol 2015;26:57–59, e19–e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sundberg JP, et al. Feline papillomas and papillomaviruses. Vet Pathol 2000;37:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilhelm S, et al. Clinical, histological and immunohistochemical study of feline viral plaques and bowenoid in situ carcinomas. Vet Dermatol 2006;17:424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]