Abstract

The concentration of calprotectin in feces (fCal) is a clinically useful marker of chronic gastrointestinal inflammation in humans and dogs. No commercial assay is widely available to measure fCal in small animal medicine, to date. Thus, we verified the immunoturbidimetric fCAL turbo assay (Bühlmann) of fCal for canine and feline fecal extracts by determining linearity, spiking and recovery, and intra-assay and inter-assay variability. We determined RIs, temporal variation over 3 mo, and effect of vaccination and NSAID treatment. Observed:expected (O:E) ratios (x̄ ± SD) for serial dilutions of feces were 89–131% (106 ± 9%) in dogs and 77–122% (100 ± 12%) in cats. For spiking and recovery, the O:E ratios were 90–118% (102 ± 11%) in dogs and 83–235% (129 ± 42%) in cats. Intra- and inter-assay CVs for canine samples were ≤19% and ≤7%, and for feline samples ≤22% and ≤21%. Single-sample RIs were <41 μg/g for dogs and <64 μg/g for cats. With low reciprocal individuality indices, using population-based fCal RIs is appropriate, and moderate fCal changes between measurements (dogs 44.0%; cats: 43.2%) are considered relevant. Cats had significant (but unlikely relevant) fCal increases post-vaccination. Despite individual fCal spikes, no differences were seen during NSAID treatment. The fCAL turbidimetric assay is linear, precise, reproducible, and sufficiently accurate for measuring fCal in dogs and cats. Careful interpretation of fCal concentrations is warranted in both species during the peri-vaccination period and for some patients receiving NSAID treatment.

Keywords: calgranulin, calprotectin, canine, chronic inflammatory enteropathy, feline, inflammation, S100A8/A9

Chronic inflammatory enteropathies (CIEs) comprise an important group of conditions in dogs and cats,2,3,8,24–26,40 and have similarities with human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). 25 The diagnosis and subclassification of CIE in veterinary patients requires extensive evaluation of the patient, including invasive testing, such as gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy to obtain mucosal biopsy samples, or laparotomy for surgical full-thickness biopsies. Monitoring the response to treatment in dogs or cats with CIE is limited to clinical and clinicopathologic parameters. 25

Calprotectin (S100A8/A9) is a highly sensitive marker for intestinal inflammation in people,11,31,32 and is used routinely in human medicine for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of patients with IBDs (Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis). 1 Calprotectin is a calcium and zinc-binding protein complex of the S100/calgranulin family that plays an important role in innate immune responses and is released primarily from activated macrophages and neutrophils.1,7,10,21 The calprotectin protein complex belongs to the group of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules, also referred to as alarmins, and can be measured reliably in several biological samples, including serum and fecal specimens. Unlike the calprotectin concentration in serum, fecal calprotectin (fCal) concentrations are more specific for GI disease processes.18,19,30 In addition, calprotectin appears to resist degradation by intestinal enzymes and bacteria; fCal concentrations were stable in human stools and canine fecal samples for up to one week at room temperature.16,31,34,35

Improved mucosal healing is associated with a better patient outcome in people with chronic intestinal inflammation, and the monitoring of treatment success plays a key role in managing affected patients.13,28 Studies evaluating fCal concentrations in dogs and cats15,19,20,21,30 suggest that fCal is a clinically useful and sensitive biomarker of intestinal inflammation in dogs19,36,21,30 and potentially cats.19,36 However, the clinical utility of fCal concentrations requires further study, particularly in cats with GI disease.

fCal is a noninvasive and relatively inexpensive biomarker that could aid in the diagnosis, subclassification, and potentially prediction of treatment response in canine CIE.15,19–36 Two canine immunoassays used in these former studies appear reliable for measuring fCal concentrations in cats.16,20 However, the assays are not widely available for use in small animal medicine to further study fCal as a biomarker, particularly in cats with chronic enteropathies (CE), including CIE and intestinal lymphoma.20,26

Successful quantification of fCal in fecal extracts from dogs and cats using human calprotectin immunoassays has failed in previous investigations, presumably because these assays use monoclonal antibodies against recombinant human calprotectin. The fCAL turbo assay (Bühlmann) is a polyclonal antibody particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay (PETIA) for the measurement of calprotectin in fecal extracts using common clinical chemistry analyzers. 5 A small-scale study by our group showed promise for the fCAL turbo assay to determine fCal concentrations in dogs and cats. 36

We aimed to analytically verify the automated fCAL turbo in vitro test to measure fCal concentrations in dogs and cats. Our analytical verification as a xenospecies assay included determining the temporal variability, reference change value (minimum critical difference), and the effect of potential confounding factors on fCal concentration in both species. We hypothesized that 1) the fCAL turbo assay reliably measures calprotectin concentrations in fecal extracts from dogs and cats, 2) using population-based RIs is appropriate for both species, and 3) confounding factors (e.g., vaccination, NSAID administration) are to be considered when interpreting canine and feline fCal concentrations.

Materials and methods

Animals

We obtained 589 fecal samples for our study from 78 dogs and 54 cats recruited at the Department for Small Animals, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Leipzig (CVM-UL), Germany in 2018–2021 (Table 1). Written consent was obtained from the owner of each patient enrolled in our study. As per the German Animal Welfare Act, ethics approval was not required to collect naturally passed fecal samples for our investigation.

Table 1.

Summary of all 172 dogs and cats included in our study of fecal calprotectin.

| Study part | n | Age, y* | Sex, female (spayed), n/male (neutered), n | Mixed/purebred (dogs), n | Breeds | Body weight, kg* | Body condition score* | Waltham feces score* | fCal concentration, µg/g* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed/DSH/purebred (cats), n | |||||||||

| Analytical verification | |||||||||

| Dogs | 18 | 7 (0.3–12) | 10 (2)/8 (6) | 7/11 | American Staffordshire (2), German Shepherd dog (2), Cocker Spaniel (1), English Setter (1), Goldendoodle (1), Papillon (1), Parson Russel Terrier (1), Rottweiler (1), Whippet (1) | NA | NA | NA | 398 (10–5,320) |

| Cats | 22 | 10 (0.3–19) | 12 (10)/10 (9) | 2/15/5 | BSH (3), Maine Coon (1), Thai cat (1) | NA | NA | NA | 175 (22–7,040) |

| RI | |||||||||

| Dogs | 57 | 6 (1–14) | 26 (16)/31 (24) | 17/40 | Berger des Pyrenees (3), Chihuahua (3), Malinois (3), Airedale Terrier (2), Dalmatian (2), German Shepherd dog (2), JRT (2), YT (2), Appenzeller Mountain dog(1), Australian Shepherd dog (1), Bavarian Mountain Hound (1), Bernese Mountain dog (1), Bolonka (1), Border Terrier (1), Boxer (1), Coton de Tulear (1), Dachshund (1), Dandie Dinmont Terrier (1), Flat-Coated Retriever (1), Giant schnauzer (1), Greater Swiss Mountain dog (1), Labrador retriever (1), Maltipoo (1), Miniature Bull Terrier (1), Pinscher (1), Rhodesian Ridgeback (1), Shi Tzu (1), Spanish Waterdog (1), Weimaraner (1) | 21 (1.7–59.8) | 5 (4–9) | 2 (1.5–3) | 7 (0–42) |

| Cats | 48 | 6 (0.75–16) | 26 (23)/22 (22) | 6/37/5 | Abyssinian (1), BSH (1), Carthusian (1), Maine Coon (1), Siamese (1) | 4.2 (3.1–11) | 5 (3.5–8) | 2 (1–3) | 12 (0–64) |

| Temporal variability | |||||||||

| Dogs | 12 | 5.5 (1–13) | 4 (3)/8 (6) | 5/7 | German Shepherd dog (2), Australian Cattle dog (1), Dalmatian (1), Flat-Coated Retriever (1), Miniature Bull Terrier (1), Pinscher (1) | 21 (6–41) | 5 (4–7) | 2 (1–4) | 7 (0–322) |

| Cats | 10 | 6 (1–16) | 3 (2)/7 (7) | 1/7/2 | Siamese (1), Scottish Fold (1) | 4.2 (3.1–5) | 5 (4–6) | 2 (1–4.5) | 15 (0–345) |

| Effect of vaccination | |||||||||

| Dogs | 16 | 5 (1–9) | 7 (4)/9 (5) | 9/7 | Dalmatian (1), Eurasian (1), Flat-Coated Retriever (1), Greater Swiss Mountain dog (1), Miniature Bull Terrier (1), Pinscher (1), Standard Poodle (1) | 27 (6–49.5) | 5 (4–7) | 2 (1–3.5) | 6 (0–229) |

| Cats | 10 | 5 (0.8–9) | 4 (3)/6 (6) | 1/8/1 | Siamese (1) | 4.2 (3–5.4) | 5 (4–6) | 2 (1–4) | 7 (0–94) |

| Effect of NSAID administration | |||||||||

| Dogs | 14 | 3.3 (0.5–11) | 8 (5)/6 (3) | 6/8 | Briard (1), Dachshund (1), Dalmatian (1), Irish Setter (1), JRT (1), Maltipoo (1), Standard Poodle (1), YT (1) | 13.8 (3–49.5) | 4 (3.5–7) | 2 (1.5–3.5) | 2 (0–61) |

| Cats | 11 | 4 (0.6–8) | 6 (2)/5 (4) | 1/10/0 | NA | 4.1 (2.6–6) | 5 (3.5–6) | 2 (1–4.5) | 5 (0–452) |

Note that some patients were included in more than one part of the study but counted only once for the total number of animals investigated, rendering 40 animals included in the analytical verification and 132 animals in the preclinical verification.

BSH = British shorthair cat; DSH = domestic shorthair cat; JRT = Jack Russell Terrier; NA = not applicable or not available; YT = Yorkshire Terrier.

Median (range).

For inclusion in the reference sampling population, dogs and cats were clinically healthy, ≥6-mo-old, with no GI signs and not receiving medications known to affect the GI tract (GIT), had normal routine bloodwork (CBC and serum biochemistry profile), regular vaccination (considering local epidemiology status and regulatory requirements), and negative fecal parasitology or regular deworming (if performed). Patients not fulfilling these criteria were excluded from this group.

Animals included in studying the effect of vaccination on fCal concentrations were clinically healthy, >9-mo-old, with unremarkable routine test results and without any clinical signs of GI disease and not receiving any medication potentially affecting the GIT. Patients not fulfilling these inclusion criteria were excluded.

Patients included in testing the effect of NSAID treatment on fCal concentrations were receiving an NSAID as part of their treatment plan for a disease process not primarily localized to the GIT (esophagus, stomach, small and/or large intestine). We excluded patients with GI signs from our study, but receiving concurrent antimicrobial therapy was not an exclusion criterion for this group.

Surplus fecal material from dogs and cats of various breeds, sex, and ages undergoing diagnostic investigations at the CVM-UL was used for the assessment of assay analytical performance (i.e., not applying any specific inclusion or exclusion criteria).

Sample collection and processing

Fecal samples were collected (from ≥5 different aliquots of each fecal sample) in a specially designed sampling tube containing proprietary extraction buffer (Calex Cap; Bühlmann), yielding a final dilution of 1:500. Following shaking incubation at room temperature (~23°C) for 20 min, fecal extracts were stored refrigerated at 4°C for up to 24 h and were then stored frozen at −20°C until further processing and/or analysis. Fecal extracts were then thawed, adjusted to room temperature, centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was used for the fCal assay.

Immunoassay procedure

Calprotectin was measured in all samples using the fCAL turbo test on a Cobas 311 chemistry analyzer (Roche). This assay has been validated and is available for human patients.5,33 Briefly, fecal extracts are incubated with a proprietary reaction buffer and mixed with polystyrene nanoparticles pre-coated with polyclonal anti-human calprotectin antibodies (immunoparticles). Binding of fCal extracts mediates the agglutination of immunoparticles, which increases sample turbidity measured as absorbance at 546 nm (main wavelength) and 800 nm (tributary signal). The absorbance increases proportionally with the number of calprotectin-immunoparticle complexes reflecting the fCal concentration, which is determined by comparison to the calibration curve. 5 The assay uses calibrators of 0–2,000 µg/g, with assay reliability being highest at 19–2,000 µg/g, and with no hook effect guaranteed until ≥8,000 µg/g (fCAL turbo, Bühlmann; https://www.buhlmannlabs.ch/products-solutions/clinical-chemistry/calprotectin).

Assessment of the immunoassay performance

Our analytical verification of the assay comprised the assessment of the limit of detection (LOD) of the assay, dilutional linearity, accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. Several specimens from cats and dogs spanning a wide range of low (20–100 µg/g), moderate (100–600 µg/g), and high (1,000–7,040 µg/g) fCal concentrations were included in this part of our study (Table 1). The LOD was determined by testing 37 replicates of the blank (assay buffer) on the same assay run, calculating the x̄ + 3SD, and transposing this value onto the calibrator curve (4-parameter logistic curve fit).

Assay dilutional linearity was determined by evaluating dilutional parallelism for 6 fecal extracts each from dogs and cats at serial 2-fold dilutions from 1:2–1:32 and was calculated as the observed:expected (O:E) ratio [observed fCal concentration (µg/g)/expected fCal concentration (µg/g) × 100%]. O:E ratios for fCal concentrations were further investigated by calculating a Spearman ρ correlation coefficient and performing a Deming regression analysis (regression formula: y = f(x) = a × x + b) with a runs test.

Accuracy of the assay was tested by mixing 10 different canine fecal samples (after their fCal concentrations were determined using the assay) at 50%:50% or 25%:75%, followed by measuring fCal concentrations in the resulting 20 mixed (spiked) samples. The same procedure was followed for feline fecal samples; 24 mixed (spiked) feline samples were prepared by mixing 16 different fecal extracts with previously analyzed fCal concentrations (at 50%:50% or 25%:75%). Expected fCal concentrations were compared with the measured (observed) concentrations, and the O:E ratio was calculated as detailed above.

Precision of the assay was evaluated by assaying fecal samples from 6 dogs and 6 cats, each 10 times within the same assay run. The intra-assay CV was then calculated as [(SD/x̄ fCal concentration) × 100%]. Assay reproducibility was evaluated by assaying fecal samples from 6 dogs and 6 cats each in 10 consecutive assay runs (over a total of 8.5 wk, using aliquots stored at −20°C) followed by calculating the inter-assay CVs as [(SD/x̄ fCal concentration) × 100%].

Immunoassay preclinical assessment

The preclinical evaluation of the fCAL turbo assay consisted of establishing RIs and assessing the temporal variability, effect of vaccination, and NSAID administration on fCal concentrations in dogs and cats. Fecal samples from 78 dogs and 54 cats of various breeds, sex, and ages were included in this part of our study (Table 1), applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined for each part of the study. Feces quality was evaluated prior to fecal extraction using a 5-point fecal scoring system.6,29,39 Owners were asked to complete a standard questionnaire including questions about the general health and vaccination and deworming status of the patient, feeding plan, type of diet, activity of the patient, travel abroad, fecal consistency, presence of vomiting, and medication history (including any supplements given) within the last 4 wk.

RIs and temporal variability

Single-sample RIs were determined using feces from 65 healthy pet dogs and 50 cats. The nonparametric RIs were calculated 14 after severe outliers (defined as fCal concentrations outside the outer Tukey fences) had been excluded from the dataset. Temporal variability was determined using repeated fecal samples from 12 healthy dogs and 10 healthy cats (Table 1) collected over 3 mo (daily sampling during the first week, weekly sampling in weeks 2–7, followed by 1 sample 1 mo later). Concentrations of fCal were determined in the same assay run in all serial fecal specimens from the same patient to reduce the between-run analytical variation and ensure that the same lots of reagents, standards, and quality controls were used. Following tests for outliers carried out at 2 levels (intra- and inter-individual variation), a nested ANOVA was performed to estimate the intra- (CVI) and inter-individual (CVG) CVs.12,41 The analytical variation (CVA) was set at the mean intra-assay CV% derived from the analytical verification part of our study. Temporal variation was expressed as the reciprocal index of individuality (rII) and the index of heterogeneity (IH), which were used to calculate the minimum critical difference (MCD0.05) using the 90th percentile of the observed distribution of within-subject variances. 12

Effect of vaccination

Fecal samples were obtained from 16 dogs and 10 cats during the peri-vaccination period. Samples were collected immediately prior to vaccination, followed by sampling on days 1, 3, and 7 post-vaccination.

Effect of NSAID administration

Fecal samples were collected from 14 canine and 11 feline patients receiving an NSAID as part of their treatment plan (5 dogs received an NSAID for orthopedic disease and/or after orthopedic surgery, 4 dogs following castration, 3 dogs after the extraction of retained deciduous teeth and/or dental cleaning, and 1 dog each after lipoma removal and treatment of anal sacculitis; 6 cats received an NSAID after neutering, 4 cats after dental procedures, and 1 cat for mild dermatitis). Fecal samples were collected from these patients immediately prior to NSAID administration, 1 sample during NSAID treatment (given for ≥3 d), and another sample 1 wk after NSAID discontinuation.

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution and equality of variances for continuous data were tested using a Shapiro–Wilk and Brown–Forsythe test, respectively. Summary statistics are presented as medians and ranges (continuous and ordinal data) or counts and percentages (nominal data). A nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) was calculated to test the relationship between continuous variables, and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for nonparametric 2-group comparisons. A Friedman test with Dunn post hoc test for multiple comparisons served to test the possibility of an effect of vaccination and NSAID administration on fCal concentrations. Excel (Office 2016; Microsoft), JMP (v.13.0; SAS Institute), and Prism (v.9.3; GraphPad Software) were used for all calculations and statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Assay analytical assessment

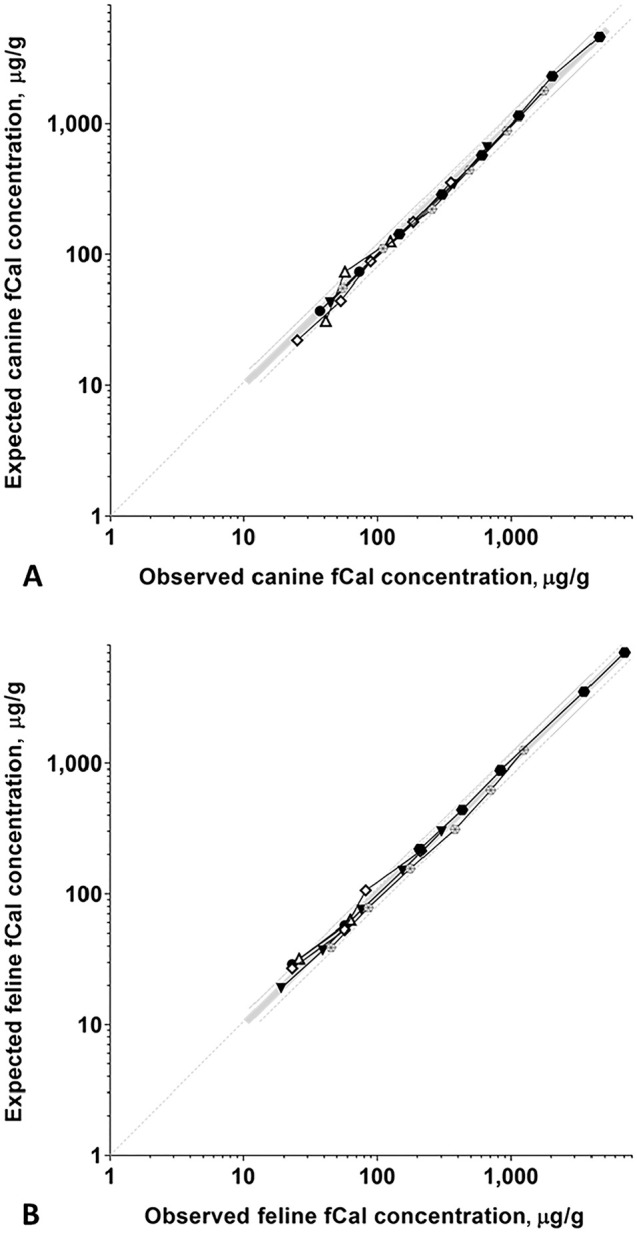

The LOD was determined as 2.7 µg/g, reported as 3 µg/g. The O:E ratios for fecal extracts from dogs were 89–131% (x̄ ± SD: 105 ± 9%), and for samples from cats were 77–122% (x̄ ± SD: 100 ± 12%; Fig. 1, Suppl. Table 1), indicating dilutional linearity of the assay for fecal samples from both species. Linear regression testing resulted in the formulas: y = f(x) = 1.081x – 28.318 (p = 0.552, runs test) and y = f(x) = 1.016x – 3.043 (p = 0.783), respectively. Observed and expected values for spiking recovery of the assay were closely correlated in 20 spiked canine samples, with O:E ratios of 90–118% (x̄ ± SD: 102 ± 11%). The O:E ratios were 83–235% (x̄ ± SD: 129 ± 42%) in 24 feline samples (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Dilutional linearity of the fCAL turbo assay for A. canine and B. feline fecal extracts. Observed and expected fCal concentrations for serially 2-fold diluted samples from A. 6 dogs and B. 6 cats were closely correlated, demonstrating linearity of the fCAL turbo assay for canine and feline specimens (for further detail, see Suppl. Table 1). Measured (observed, O) fCal concentrations are plotted on the x-axis, expected (E) concentrations are on the y-axis. Each symbol indicates a specific fecal extract, the bold gray line indicates perfect linearity (O:E ratio = 100%), and the thin broken gray lines indicate the acceptance criteria for assay linearity (lower line, O:E ratio = 80%; upper line, O:E ratio = 120% 37 ).

Table 2.

Accuracy (spiking and recovery) of the fCAL turbo assay for canine and feline fecal extracts. The percentage observed:expected ratios (O:E) for the spiking and recovery of fCal for 20 spiked fecal extracts from dogs (C1–C20) and 25 spiked fecal extracts from cats (F1–F25).

| Dogs | Cats | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | O, µg/g | E, µg/g | Mix ratio, % | O:E, % | Sample | O, µg/g | E, µg/g | Mix ratio, % | O:E, % |

| C1 | 49 | 49 | 25:75 | 100 | F1 | 53 | 45 | 50:50 | 118 |

| C2 | 70 | 73 | 50:50 | 95 | F2 | 69 | 81 | 50:50 | 85 |

| C3 | 76 | 72 | 75:25 | 105 | F3 | 72 | 53 | 50:50 | 135 |

| C4 | 232 | 208 | 50:50 | 111 | F4 | 116 | 66 | 50:50 | 176 |

| C5 | 251 | 254 | 50:50 | 99 | F5 | 136 | 146 | 50:50 | 93 |

| C6 | 262 | 231 | 50:50 | 114 | F6 | 143 | 78 | 75:25 | 185 |

| C7 | 286 | 251 | 50:50 | 114 | F7 | 148 | 82 | 75:25 | 181 |

| C8 | 301 | 274 | 50:50 | 110 | F8 | 239 | 148 | 50:50 | 161 |

| C9 | 482 | 421 | 50:50 | 115 | F9 | 260 | 173 | 50:50 | 151 |

| C10 | 842 | 718 | 50:50 | 117 | F10 | 353 | 315 | 50:50 | 112 |

| C11 | 871 | 740 | 50:50 | 118 | F11 | 367 | 334 | 50:50 | 110 |

| C12 | 1,064 | 931 | 50:50 | 114 | F12 | 424 | 384 | 50:50 | 110 |

| C13 | 1,077 | 1,197 | 50:50 | 90 | F13 | 478 | 224 | 75:25 | 213 |

| C14 | 1,238 | 1,378 | 50:50 | 90 | F14 | 569 | 242 | 75:25 | 235 |

| C15 | 1,255 | 1,370 | 50:50 | 92 | F15 | 770 | 881 | 50:50 | 87 |

| C16 | 1,274 | 1,392 | 50:50 | 91 | F16 | 971 | 891 | 50:50 | 109 |

| C17 | 1,284 | 1,402 | 50:50 | 92 | F17 | 1,012 | 878 | 50:50 | 115 |

| C18 | 1,439 | 1,539 | 50:50 | 93 | F18 | 1,024 | 919 | 50:50 | 111 |

| C19 | 1,463 | 1,583 | 50:50 | 92 | F19 | 1,056 | 928 | 50:50 | 114 |

| C20 | 1,931 | 2,049 | 50:50 | 94 | F20 | 1,066 | 905 | 50:50 | 118 |

| F21 | 1,258 | 1,511 | 50:50 | 83 | |||||

| F23 | 1,340 | 1,520 | 50:50 | 88 | |||||

| F24 | 1,794 | 1,675 | 50:50 | 107 | |||||

| F25 | 2,823 | 2,876 | 50:50 | 98 | |||||

Intra-assay CVs were ≤19% in 6 canine fecal extracts and ≤22% in 6 feline samples (Table 3), demonstrating precision of the assay. The inter-assay CVs were 6–7% in 6 dogs and 5–21% in 6 cats (Table 4).

Table 3.

Precision of the fCAL turbo assay for canine and feline fecal extracts. The intra-assay CVs for 6 fecal extracts from dogs (C1–C6) and 6 fecal extracts from cats (F1–F6), each tested 10 times on the same assay run.

| Dogs | Cats | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | x̄, µg/g | SD | CV% | Sample | x̄, µg/g | SD | CV% |

| C1 | 75 | 7 | 9 | F1 | 57 | 11 | 19 |

| C2 | 98 | 7 | 7 | F2 | 60 | 13 | 22 |

| C3 | 355 | 13 | 4 | F3 | 206 | 9 | 4 |

| C4 | 697 | 8 | 1 | F4 | 402 | 70 | 18 |

| C5 | 2,022 | 21 | 1 | F5 | 1,656 | 57 | 3 |

| C6 | 5,132 | 953 | 19 | F6 | 6,895 | 51 | 1 |

Table 4.

Reproducibility of the fCAL turbo assay for canine and feline fecal extracts. The inter-assay CVs for 6 different fecal extracts from dogs (C1–C6) and 6 different fecal extracts from cats (F1–F6), each measured in 10 consecutive assay runs (over a total of 8.5 wk, using aliquots stored at −20°C).

| Dogs | Cats | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | x̄, µg/g | SD | CV% | Sample | x̄, µg/g | SD | CV% |

| C1 | 80 | 6 | 7 | F1 | 52 | 11 | 21 |

| C2 | 99 | 7 | 7 | F2 | 53 | 5 | 9 |

| C3 | 356 | 20 | 6 | F3 | 204 | 12 | 6 |

| C4 | 673 | 43 | 6 | F4 | 331 | 18 | 5 |

| C5 | 1,910 | 107 | 6 | F5 | 1,418 | 115 | 8 |

| C6 | 4,808 | 301 | 6 | F6 | 6,834 | 408 | 6 |

Assay preclinical evaluation

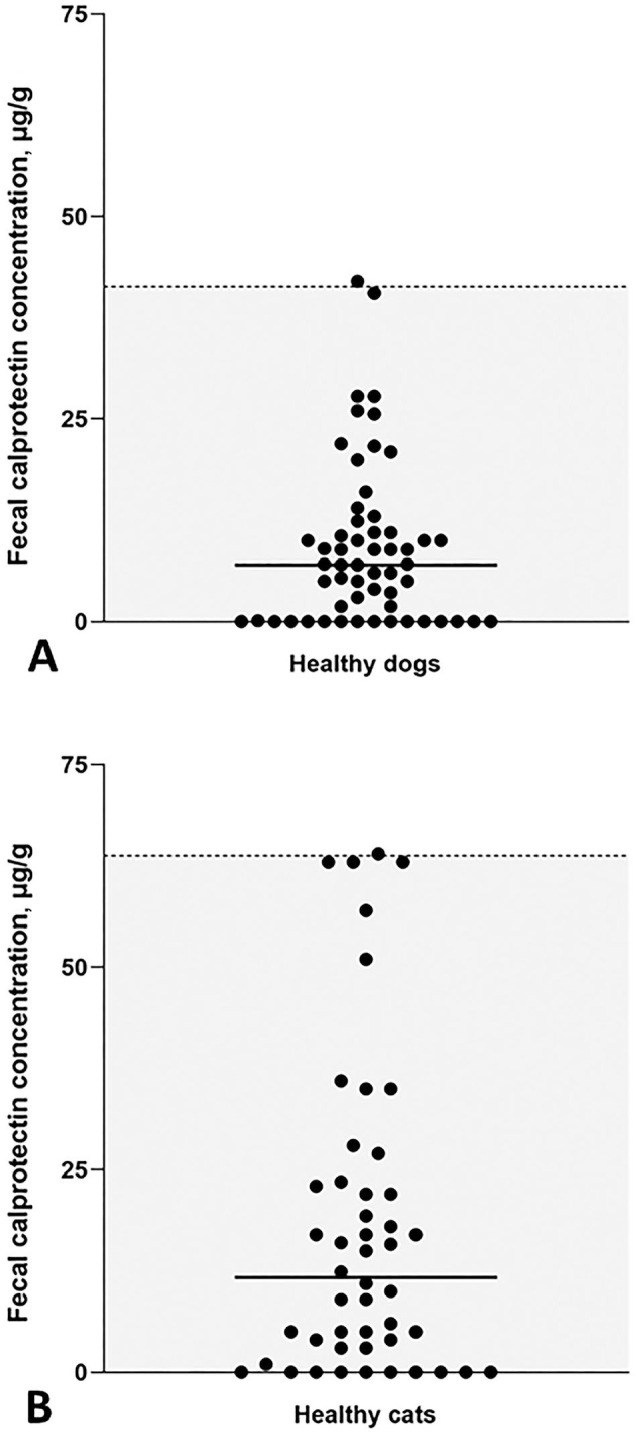

fCal concentrations in samples from 65 healthy dogs covering a wide range of different breeds, sex, and ages (Table 1) were 3–226 µg/g (median: 9 µg/g). Eight severe outliers (above the upper outer Tukey fence) were removed from the reference population, and the canine fCal RI was established from 57 dogs as <41 µg/g (Fig. 2A). Age, sex, breed (purebred vs. mixed breed), body weight, and body condition score (BCS) were not correlated with fCal concentrations (all p > 0.05), but lower feces scores were weakly associated with higher fCal concentration (ρ = −0.34, p = 0.014).

Figure 2.

RIs for canine and feline fCal concentrations using the fCAL turbo assay. Scatter plots of fCal concentrations measured in the reference populations of A. 57 healthy dogs and B. 48 healthy cats. Each symbol represents the concentration of a specific dog or cat sample. Median fCal concentrations (solid horizontal lines) and RIs (gray shaded portion below the dashed horizontal line) were calculated.

fCal concentrations in samples from 50 healthy cats were 3–152 µg/g (median: 14 µg/g). Two severe outliers (above the upper outer Tukey fence) were removed from the dataset, and the RI for feline fCal established from 48 cats was <64 µg/g (Fig. 2B). The reference population included cats of various sex and ages, but cats of the domestic shorthair breed (DSH) were overrepresented (Table 1). Age, sex, breed (purebred vs. DSH vs. mixed breed), body weight, BCS, and the Waltham feces score were not correlated with fCal concentrations (all p > 0.05).

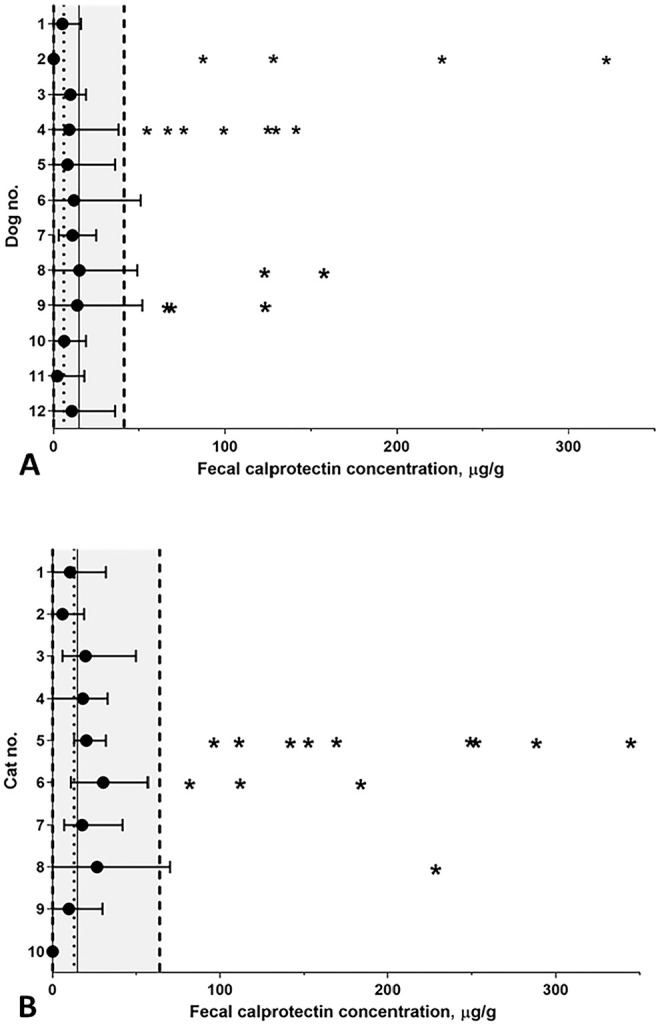

For determining the long-term temporal variability in dogs, 15 serial fecal samples were obtained from 4 dogs, 14 samples from 4 dogs, 13 samples from 3 dogs, and 6 samples from 1 dog. Sixteen within-subject outliers were detected (4, 7, 2, and 3 in samples from dogs 2, 4, 8, 9, respectively; Cochrane test) and excluded from further analysis, yielding 145 samples included in the dataset and slightly right-skewed data (Fig. 3A). No outliers among mean concentrations of subjects (extreme minus next highest concentration = 14% of the concentration range; Reed criterion) were detected. With CVA set at 6.8%, CVI was calculated as 119% and CVG as 16.7% resulting in a CVT of 143%. The rII was 0.14, IH was 23.7, and the 1-sided MCD0.05 44.0%.

Figure 3.

Temporal variation over 3 mo of fCal concentrations in A. 12 healthy dogs and B. 10 healthy cats. The mean (circles) and range (horizontal bars) of fCal concentrations are shown for each dog or cat. The gray shaded areas (to the left of the dashed vertical lines) indicate the RIs; the overall mean fCal concentrations are shown by the dotted vertical lines (dogs: 9 μg/g; cats: 16 μg/g). Three dogs and 1 cat had at least 1 measurement above the respective upper reference limit (dogs: 41 μg/g; cat: 64 μg/g). Asterisks indicate outlying observations (level II outliers) removed from the dataset.

For evaluation of the temporal variability of feline fCal, 14 serial samples were obtained from 6 cats, 13 samples from 1 cat, 12 samples from 2 cats, and 10 samples from 1 cat. Thirteen within-subject outliers were detected (9, 3, and 1 in samples from cats 5, 6, 8, respectively) and excluded from further analysis, yielding 118 measurements included in the dataset and slightly right-skewed data (Fig. 3B). No outliers were detected among the cats’ mean fCal concentrations (extreme minus next highest concentration = 20% of the concentration range). With CVA set at 11.2%, CVI was calculated as 71.8% and CVG as 7.2%, resulting in a CVT of 90.1%. The rII was 0.10, IH was 25.5, and the 1-sided MCD0.05 43.2%.

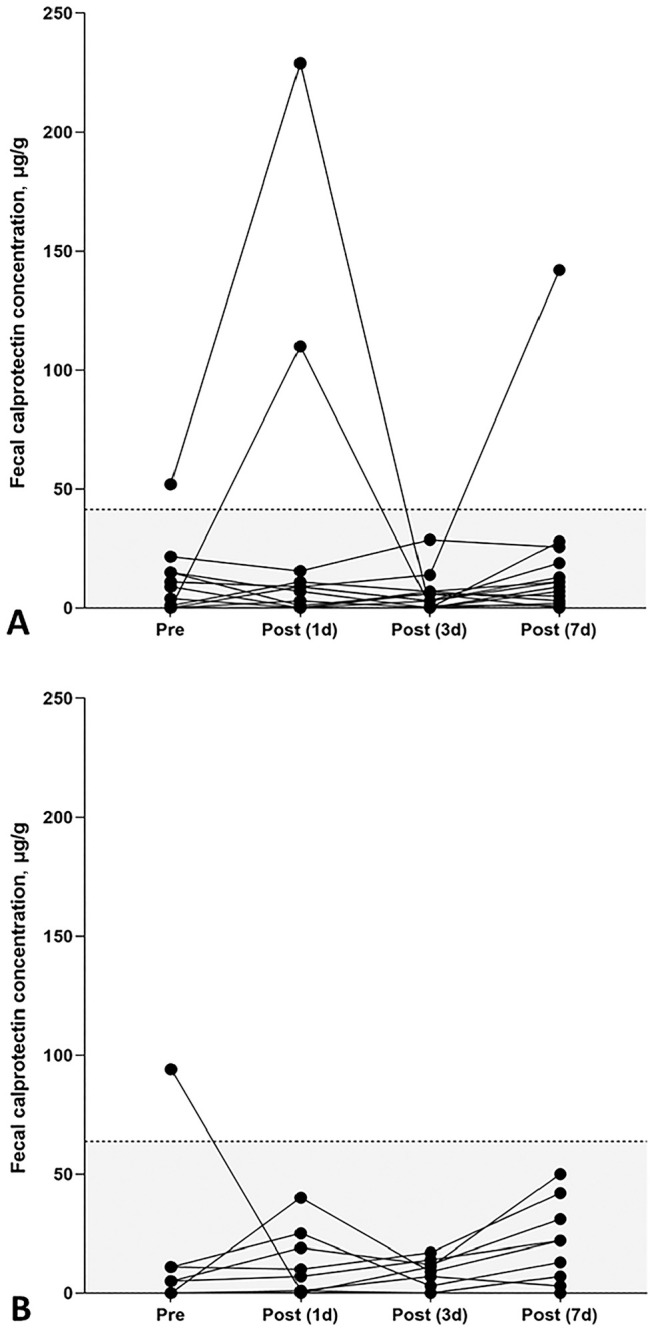

Of the 16 dogs included in testing the effect of vaccination (Table 1), 11 dogs (69%) received a parenteral vaccine that included a canine parvovirus 2 (CPV2; Carnivore protoparvovirus 1) modified-live virus (MLV) vaccine. The concentration of fCal was increased above the RI (i.e., >41 µg/g) in 5 of the 63 fecal samples from healthy dogs (7-d post-vaccination sample missing in 1 dog) in the peri-vaccination period: in 1 dog prior to vaccination (52 µg/g), in 3 dogs the day after vaccine administration (49 µg/g, 110 µg/g, 229 µg/g), and in 1 dog a week post-vaccination (142 µg/g). Despite these individual fCal increases, there were no significant differences in fCal concentrations among the 4 peri-vaccination times in all 16 dogs sampled (p = 0.220; Fig. 4A), neither were any differences detected in only the 11 dogs that received a CPV2 vaccine (p = 0.513).

Figure 4.

Peri-vaccination fCal concentrations in dogs and cats. A. No statistically significant differences in fCal concentrations were observed in 16 healthy pet dogs prior to vaccination (median: 7 µg/g; range: 3–52 µg/g) and 1 d (median: 8 µg/g; range: 3–229 µg/g), 3 d (median: 3 µg/g; range: 3–29 µg/g), and 7 d (median: 9 µg/g; range: 3–142 µg/g) post-vaccination (p = 0.220). B. In cats, peri-vaccination fCal concentrations differed significantly (p = 0.018). A significant increase in fCal concentrations was detected 7 d post-vaccination (median 18 µg/g; range: 3–50 µg/g) compared to pre-vaccination concentrations (median: 3 µg/g, range: 0–94 µg/g; p = 0.013) but no differences compared to days 1 (median: 4 µg/g; range: 3–40 µg/g) or 3 (median: 8 µg/g, range: 3–17 µg/g; both p > 0.05) after vaccination. Each symbol represents the fCal concentration for a specific dog or cat and time. RIs are indicated by the gray shaded portions below the dashed horizontal lines.

All 10 healthy pet cats included in this part of our study (Table 1) received a parenteral feline panleukopenia (feline parvovirus, FPV; Carnivore protoparvovirus 1) vaccine. One cat had a fCal concentration above the feline fCal RI (i.e., >64 µg/g) in the pre-vaccination fecal sample (94 µg/g). The 3 post-vaccination samples of this cat and all samples from the remaining cats yielded fCal concentrations within the RI. However, fCal concentrations differed significantly in the peri-vaccination period in cats (p = 0.018), with a significant increase 7 d after vaccine administration (median 18 µg/g) compared to pre-vaccination concentrations (median: 3 µg/g, p = 0.013; Fig. 4B).

Of the 14 canine patients included (Table 1), 2 dogs (17%) received a classical NSAID (1 dog each meloxicam 0.1 mg/kg and metamizole 33 mg/kg) and the remaining 12 dogs (83%) a coxib NSAID (robenacoxib) at the recommended dose (1.1–2.0 mg/kg) for 5–14 d. Additional antimicrobial therapy was administered to 4 dogs (amoxicillin–clavulanate: 3 dogs; cefalexin: 1 dog). None of the patients received a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or probiotic during NSAID treatment. Two dogs had a slightly increased fCal concentration at baseline (48 µg/g, 61 µg/g), but fCal concentrations were within the canine fCal RI in all other samples. There were no significant differences in fCal concentrations among the 3 different times around NSAID treatment (p = 0.337; Fig. 5A).

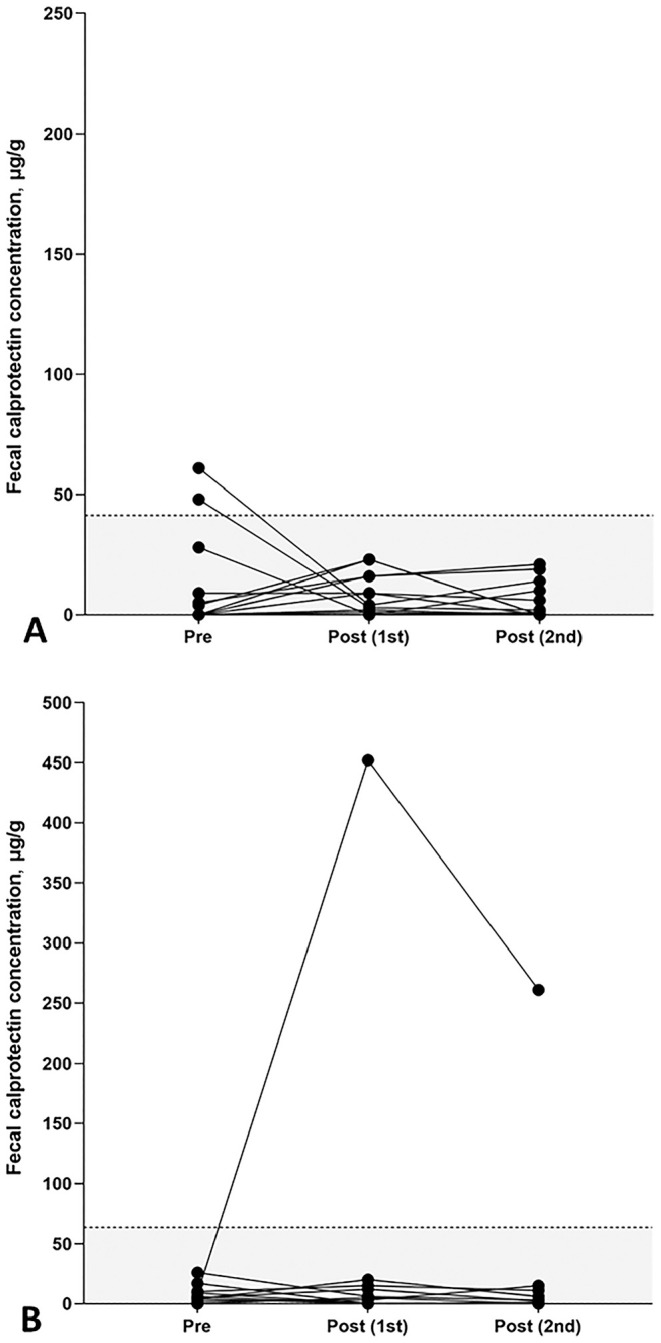

Figure 5.

Serial fCal concentrations in NSAID-treated dogs and cats. A. No statistically significant changes in fCal concentrations were detected in 14 canine patients during (post 1st; median: 4 µg/g, range: 3–23 µg/g) or after (post 2nd; median: 1 µg/g, range: 3–21 µg/g) NSAID treatment compared to pretreatment fCal concentrations (median: 3 µg/g, range: 3–61 µg/g; p = 0.337). B. In cats, no significant changes in fCal concentrations were detected during (post 1st; median: 5 µg/g, range: 0–452 µg/g) or after (post 2nd; median: 3 µg/g, range: 0–261 µg/g) NSAID treatment compared to pretreatment fCal concentrations (median: 6 µg/g, range: 3–26 µg/g; p = 0.483), but a marked increase in fCal concentrations during (452 μg/g) and after (261 μg/g) NSAID treatment was seen in 1 cat. Each symbol represents the fCal concentration for a specific dog or cat and time. RIs are indicated by the gray shaded portions below the dashed horizontal lines.

All 11 cats included (Table 1) were given standard-dose meloxicam (0.05 mg/kg). One cat also received antimicrobial therapy (amoxicillin–clavulanate); another cat received neuroanalgesia (gabapentin). No significant changes in fCal concentrations were seen among the 3 times around NSAID treatment (p = 0.483; Fig. 5B). However, 1 cat had a marked increase in fCal concentrations during (452 μg/g) and after (261 μg/g) NSAID treatment compared to pretreatment (9 μg/g).

Discussion

Assay dilutional linearity, demonstrated by serial 2-fold dilutions of fecal extracts, showed very good agreement between observed and expected fCal concentrations. The O:E ratios were, except for a single fecal extract from 1 dog (with an O:E ratio of 131% at a 1:4 dilution), within the acceptable range (80–120%).4,37 A slightly larger inaccuracy of fCal measurements towards the LOD of the assay working range is to be expected and might explain the higher variation in one sample. There is no obvious explanation for a slight inaccuracy in the serial dilution experiment with 2 other feline samples—a 1:2 diluted fecal extract (77%) and a 1:4 diluted sample (122%); the remaining dilution steps of the same samples had good O:E correlations. In addition, the results of the runs tests and Deming regression analyses indicated dilutional parallelism in the serial dilutions of fecal extracts from dogs and cats.

Assay accuracy was demonstrated by spiking and recovery for all fecal extracts included from dogs, with all O:E ratios in the acceptable range.4,37 Some assay inaccuracy was observed for feline fecal extracts wherein 8 of 24 of the spiked samples yielded O:E ratios above the acceptable range (135–235%; x̄: 180%). This over-recovery was independent of the mixing ratio used to prepare the spiked samples (25%:75% or 50:50%) but was predominantly seen in fecal extracts with low-to-moderate fCal concentrations. A possible explanation is that certain fecal samples from cats contained material (e.g., undigested dietary components, fiber) or had a variable composition (e.g., urea, calcium, and/or zinc content affecting S100A8/A9 heteropolymer formation) interfering with antibody binding to fCal in the assay, and a carryover of this effect was observed when samples were used for several spikes. Fecal extracts were stored frozen until analysis, and a temperature-dependent effect (e.g., affecting the binding between S100A8 and S100A9) cannot be ruled out, but appears less likely given that all other fecal extracts (including those from dogs) underwent the same storage conditions.

Reliable performance of a xenospecies assay crucially depends on antibody binding to the homologous antigen. Hence, the fCAL turbo assay might be more accurate in dogs than in cats given the different homology of the amino acid sequence of the S100A8/A9 proteins conferring structural similarity of the antigenic sites between human and canine or feline calprotectin. 16 Protein sequence alignment analyses for canine and feline S100A8 with the human protein using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) revealed homologies of 76.4% and 75.3%, respectively, whereas identity of the canine and feline S100A9 protein with the human analog is 65.8% and 63.7%. In addition, different isoforms of S100A8 and S100A9—known to exist in humans but not reported in dogs or cats—resulting in variable antibody avidity might contribute to the (unexpected) inaccuracy of the fCAL turbo assay in some feline samples.

The CV for intra- and inter-assay variation should be <15%,4,37 except for samples with very low or very high concentrations wherein CVs up to 20% are acceptable. This performance criterion was fulfilled for all canine fecal extracts included in the intra-assay variation testing, indicating precision of the assay. The assay was also sufficiently precise for fecal extracts from cats, with 2 samples having CVs of 15–20% and 1 sample of 22%. Inter-assay CVs demonstrated reproducibility of the assay for fecal extracts from dogs (all <10%) and cats (<10% in 5 of 6 samples).

The single-sample RIs for fCal concentration in dogs and cats were <41 µg/g and <64 µg/g, respectively. These upper reference limits agree with previous studies in dogs15,16,23 and cats. 20 The first canine study reported a higher RI with a 3-d mean sample RI of <138 µg/g, but this was determined using a radioimmunoassay, and the healthy dogs included were not subjected to routine bloodwork, in addition to some of them living in a research colony. 16 Nonetheless, ~75% of that reference population had a fCal concentration within the singe-sample RI calculated in our study. The second study’s 3-d-sample RI, including 52 clinically healthy dogs, was 3.2–65.4 µg/g, 17 showing closer agreement with our findings. In another study, fCal concentrations (measured by radioimmunoassay) were 2.9–110 µg/g in 69 healthy dogs. 15 Similar to our results, there was no association of the dogs’ age, sex, breed, body weight, or BCS with fCal concentrations in another study. 23 A feline study evaluating fCal concentrations (samples collected on 3 consecutive days) by radioimmunoassay yielded a similar RI of 1.5–66.5 µg/g. 20

Our study shows that some healthy dogs and cats can occasionally have high fCal concentrations. This might be a transient phenomenon, but we did not perform a more invasive assessment of health (including abdominal ultrasound, urinalysis, and endoscopy to exclude subclinical GI disease). In the absence of a pathophysiologic explanation for the outliers observed, repeating fCal testing appears a reasonable suggestion in such cases. We determined the LOD of the assay as 2.7 µg/g, which agrees with that of the canine RIA (2.9 µg/g), 16 but the manufacturer reports that fCal concentrations <19 µg/g are prone to some inaccuracy (https://www.buhlmannlabs.ch/products-solutions/clinical-chemistry/calprotectin), which we confirmed as LOD with a linear curve fit. Given the established RIs in our study and the working range of the fCAL turbo assay, the fCAL turbo assay appears suitable for use with canine and feline fecal samples.

Variation of fCal concentrations within fecal samples from the same defecation was noted in another study 16 and led to the initial recommendation to collect fecal samples from 3 consecutive days to counterbalance that physiologic variation. It was speculated that the within-sample variation resulted from patchy emigration of calprotectin-expressing cells into the GI mucosa. 16 Our study, similar to others, included only single fecal samples from dogs and cats, and future studies will determine whether single-sample fCal determinations are sufficient to distinguish disease from health.

Serial fCal measurements in dogs and cats over time showed some within- and inter-individual variability. Long-term evaluation of canine fCal concentration to assess temporal variation showed that some clinically healthy dogs can have individual fCal spikes without GI signs. However, none of the dogs had a marked increase in fCal, and only a few samples had moderately increased fCal concentrations. Our data indicate that mild fCal increases absent any GI signs can also occur occasionally in cats. However, marked increases in fCal concentrations are more likely to be expected to be associated with clinical signs and/or potential underlying causes.

Although fCal concentrations vary to some extent in individual dogs and cats, individuality was low in both species, with both rIIs ≤0.14. As indicated by the MCD0.05, moderate changes in fCal between sequential measurements in a dog (44.0%) or cat (43.2%) are to be considered clinically relevant rather than reflecting temporal and/or analytical variation.12,41 Thus, using a conventional population-based RI to detect increased fCal concentrations appears appropriate in both species.12,41 The analytical goal of CVA ≤ ½ × CVI12,41 was also satisfied in our study.

In dogs, we did not detect a significant effect of vaccination on fCal concentration. However, 2 dogs without any GI signs during fecal sample collection had a moderately increased fCal concentration the day after vaccination. One of these dogs received a vaccine including CPV2, which can cause transient subclinical GI inflammation and increased fecal S100-calgranulin concentrations in dogs. 23 A third dog had a moderately increased fCal concentration with simultaneously soft stool consistency 7 d after receiving a vaccine including CPV2. In contrast, significant differences among the times tested around vaccination were seen in cats, with significantly increased fCal concentrations 7 d post-vaccination. However, all fCal levels remained within the RI. These findings are rather unexpected given the previous finding of higher fCal concentrations in dogs sampled within 4 wk of receiving a CPV2 MLV vaccine. 23 However, transient subclinical intestinal inflammatory responses to CPV2 MLV vaccination might be mild and/or take >7 d to develop post-vaccination. 9

No significant differences in fCal concentrations were seen among the times of NSAID (classical NSAID or coxib) administration in either species. This agrees with the results of a study in which fCal (and fecal dysbiosis index) increased in dogs co-administered a classical NSAID (carprofen) and PPI but not if given an NSAID alone, 27 suggesting that PPI prophylaxis can induce dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation. 38 All cats and a few dogs in our study received a classical NSAID (meloxicam), most dogs a coxib (robenacoxib), but none of the animals received a PPI concurrently. Only one cat had a moderate fCal increase during and again 1 wk after cessation of NSAID treatment. This cat had wounds and inflammation in the neck area requiring additional analgesia (gabapentin). Nevertheless, fCal concentrations should be carefully interpreted in patients receiving NSAID treatment. The treatment plan for 5 animals included antimicrobial therapy, which can also cause dysbiosis, but this did not appear to affect fCal.

Our study had some limitations, including the minimally invasive determination of health (physical examination, routine bloodwork) in the reference populations and those dogs and cats sampled to assess temporal variation. Given ethical constraints, more invasive testing (e.g., ultrasound-guided cystocentesis for urinalysis, GI endoscopy) was not performed. Also, dogs and cats included in evaluating potential confounding effects of vaccination and NSAID therapy on fCal concentrations yielded heterogeneous groups of clinical patients with different underlying primary disease processes. Last, given the lack of a gold standard test for fCal determination in canine and feline specimens, fCal concentrations obtained in our study could not be verified or compared to another assay system.

The results of our analytical assessment suggest that the fCAL turbo assay performs satisfactorily with canine fecal extracts and produces reliable fCal measurements in cats.4,37 Use of this assay appears to be a reasonable option for measuring fCal concentrations in dogs and, pending further research, in cats. Clinical evaluation of the assay is now needed to determine whether the test is clinically useful and sufficiently accurate to differentiate diseased cats from healthy cats, 20 despite being slightly less precise in cats than dogs. Careful interpretation of fCal concentrations is warranted in dogs and cats during the peri-vaccination period and some patients receiving NSAID treatment. Our results provide an important basis for further evaluating fCal and its value in dogs and cats with GI disease.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-vdi-10.1177_10406387221114031 for Verification of the fCAL turbo immunoturbidimetric assay for measurement of the fecal calprotectin concentration in dogs and cats by Lena L. Enderle, Gabor Köller and Romy M. Heilmann in Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation

Acknowledgments

We thank Carola Näther and Annekathrin Ruhland (Department for Large Animals, University of Leipzig, Germany) and Ines Müller and Julia Schwippel (Department for Small Animals, University of Leipzig, Germany) for their assistance with the processing of clinical samples.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: Our study was performed with the generous support of Bühlmann Laboratories, Schönenbuch, BL, Switzerland. The company provided analyzer reagents, expertise in the application, and assay-specific materials.

Funding: Part of our study (evaluation of fCal in healthy cats) was supported by the EveryCat Health Foundation (W21-030). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of EveryCat.

ORCID iD: Romy M. Heilmann  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3485-5157

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3485-5157

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Lena L. Enderle, Department for Small Animals, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Leipzig, Saxony, Germany

Gabor Köller, Department of Large Animal Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Leipzig, Saxony, Germany.

Romy M. Heilmann, Department for Small Animals, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Leipzig, Saxony, Germany.

References

- 1. Abej E, et al. The utility of fecal calprotectin in the real-world clinical care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;2016:2483261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allenspach K, et al. Chronic enteropathies in dogs: evaluation of risk factors for negative outcome. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allenspach K, et al. Long-term outcome in dogs with chronic enteropathies: 203 cases. Vet Rec 2016;178:368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnold JE, et al. ASVCP guidelines: principles of quality assurance and standards for veterinary clinical pathology (version 3.0). Vet Clin Pathol 2019;48:542–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bühlmann Laboratories AG. BÜHLMANN fCAL® turbo Calprotectin turbidimetric assay for professional use: reagent kit. Revised 2017. Dec 19. [cited 2019 May 28]. https://www.buhlmannlabs.ch/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/KK-CAL_IFU-CE-Reagent_2017-12-19.pdf

- 6. Cavett CL, et al. Consistency of faecal scoring using two canine faecal scoring systems. J Small Anim Pract 2021;62:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dale I, et al. Distribution of a new myelomonocytic antigen (L1) in human peripheral blood leukocytes. Immunofluorescence and immunoperoxidase staining features in comparison with lysozyme and lactoferrin. Am J Clin Pathol 1985;84:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dandrieux JRS. Inflammatory bowel disease versus chronic enteropathy in dogs: are they one and the same? J Small Anim Pract 2016;57:589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Decaro N, et al. Long-term viremia and fecal shedding in pups after modified-live canine parvovirus vaccination. Vaccine 2014;32:3850–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ehrchen JM, et al. The endogenous Toll-like receptor 4 agonist S100A8/S100A9 (calprotectin) as innate amplifier of infection, autoimmunity, and cancer. J Leukoc Biol 2009;86:557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fagerhol MK. Calprotectin, a faecal marker of organic gastrointestinal abnormality. Lancet 2000;356:1783–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fraser CG, Harris EK. Generation and application of data on biological variation in clinical chemistry. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 1989;27:409–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frøslie KF, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology 2007;133:412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geffré A, et al. Reference values: a review. Vet Clin Pathol 2009;38:288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grellet A, et al. Fecal calprotectin concentrations in adult dogs with chronic diarrhea. Am J Vet Res 2013;74:706–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heilmann RM, et al. Development and analytic validation of a radioimmunoassay for the quantification of canine calprotectin in serum and feces from dogs. Am J Vet Res 2008;69:845–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heilmann RM, et al. Development and analytic validation of an immunoassay for the quantification of canine S100A12 in serum and fecal samples and its biological variability in serum from healthy dogs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011;144:200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heilmann RM, et al. Serum calprotectin concentrations in dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Vet Res 2012;73:1900–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heilmann RM, et al. Association of fecal calprotectin concentrations with disease severity, response to treatment, and other biomarkers in dogs with chronic inflammatory enteropathies. J Vet Intern Med 2018;32:679–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heilmann RM, et al. Preanalytical validation of an in-house radioimmunoassay for measuring calprotectin in feline specimens. Vet Clin Pathol 2018;47:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heilmann RM, et al. Mucosal expression of S100A12 (calgranulin C) and S100A8/A9 (calprotectin) and correlation with serum and fecal concentrations in dogs with chronic inflammatory enteropathy. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2019;211:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heilmann RM, et al. Biological variation of serum canine calprotectin concentrations as measured by ELISA in healthy dogs. Vet J 2019;247:61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heilmann RM, et al. Association of clinical characteristics and lifestyle factors with fecal S100/calgranulin concentrations in healthy dogs. Vet Med Sci 2021;7:1131–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jergens AE. Feline idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease: what we know and what remains to be unraveled. J Feline Med Surg 2012;14:445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jergens AE, et al. A clinical index for disease activity in cats with chronic enteropathy. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:1027–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jergens AE, Simpson KW. Inflammatory bowel disease in veterinary medicine. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:1404–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones SM, et al. The effect of combined carprofen and omeprazole administration on gastrointestinal permeability and inflammation in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2020;34:1886–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lobatón T, et al. A new rapid quantitative test for fecal calprotectin predicts endoscopic activity in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moxham G. Waltham feces scoring system—a tool for veterinarians and pet owners: how does your pet rate? Waltham Focus 2001;11:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Otoni CC, et al. Serologic and fecal markers to predict response to induction therapy in dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. J Vet Intern Med 2018;32:999–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Røseth AG, et al. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992;27:793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Røseth AG, et al. Normalization of faecal calprotectin: a predictor of mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1017–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sloovere MMW de, et al. Analytical and diagnostic performance of two automated fecal calprotectin immunoassays for detection of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:1435–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tibble J, et al. A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2000;47:506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tibble JA, et al. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2000;119:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Truar K, et al. Feasibility of measuring fecal calprotectin concentrations in dogs and cats by the fCAL® turbo immunoassay. J Vet Intern Med 2018;32:580. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Valentin MA, et al. Validation of immunoassay for protein biomarkers: bioanalytical study plan implementation to support pre-clinical and clinical studies. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2011;55:869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wallace JL, et al. Proton pump inhibitors exacerbate NSAID-induced small intestinal injury by inducing dysbiosis. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Waltham Petcare Science Institute. The Waltham™ Faeces Scoring System. 2020. [cited 2021. Aug 18]. https://www.waltham.com/sites/g/files/jydpyr1046/files/2020-05/waltham-scoring.pdf

- 40. Washabau RJ, et al. Endoscopic, biopsy, and histopathologic guidelines for the evaluation of gastrointestinal inflammation in companion animals. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:10–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu AHB, et al. Short- and long-term biological variation in cardiac troponin I measured with a high-sensitivity assay: implications for clinical practice. Clin Chem 2009;55:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-vdi-10.1177_10406387221114031 for Verification of the fCAL turbo immunoturbidimetric assay for measurement of the fecal calprotectin concentration in dogs and cats by Lena L. Enderle, Gabor Köller and Romy M. Heilmann in Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation