Abstract

Introduction:

Acute ischemic stroke therapy has improved in recent decades, decreasing the rates of disability and death among stroke patients. Unfortunately, all health care systems have geographical disparities in infrastructure for stroke patients. A centralized telestroke network might be a low-cost strategy to reduce differences in terms of geographical barriers, equitable access, and quality monitoring across different hospitals.

Aims:

We aimed to quantify changes in stroke patients’ geographic access to specialized evaluation by neurologists and to intravenous acute stroke reperfusion treatments following the rapid implementation of a centralized telestroke network in the large region of Andalusia (8.5 million inhabitants).

Methods:

We conducted an observational study using spatial and analytical methods to examine how a centralized telestroke network influences the quality and accessibility of stroke care for a large region.

Results:

In the pre-implementation period, 5,005,477 (59.72% of the Andalusian population) had access to specialized stroke care in less than 30 min. After the 5-month process of implementing the telestroke network, 7,832,988 (93.5%) inhabitants had an access time of less than 30 min, bridging the gap in acute stroke care in rural hospitals.

Conclusions:

A centralized telestroke network may be an efficient tool to reduce the differences in stroke care access and quality monitoring across different hospitals, especially in large regions with low population density.

Keywords: Stroke, telestroke, network

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of disability and the second leading cause of death worldwide. Additionally, the prevalence of stroke is expected to increase. 1 Currently, stroke accounts for approximately 3%–4% of total health care expenditures in Western countries, and this percentage may increase in the years to come. 2 Stroke care disparities are found in all health care systems, and geographical disparities are one of the most important causes. 3 In fact, geographic differences in stroke incidence, mortality, and case fatality have been described within the same country and even between rural and urban areas of the same region. 4

According to data published by the WHO, the overall 30-day mortality rate after stroke is 32%, although it varies depending on several factors, such as age, type of stroke, sex, premorbid condition, treatment in the acute phase, and complications. 5 Acute care for ischemic stroke has evolved considerably in recent decades, generating noteworthy decreases in the rates of disability and death. However, the efficacy and safety of these treatments are time dependent. Therefore, efforts must be made to shorten the time from symptom onset to treatment. These treatments and other aspects of the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke are well established in different guidelines. They should be led by a stroke specialist, with telemedicine being a practical way to facilitate access to stroke specialists for patients in remote areas.6–9

In Spain, stroke mortality has decreased at least 7% in recent years, but even so, it remains substantial, at 33.6 per 100,000 inhabitants. 10 Andalusia is a region of Spain in southern Europe with an area of 87,597 km2 and a population of 8,381,944 inhabitants, similar in size to Portugal, Austria, or Hungary. Andalusia has been called the “Spanish Stroke Belt” on account of its extremely high stroke mortality rate, which is as high as 54 per 100,000 inhabitants and exceeds those of other Spanish regions by up to 50%. 11 In addition to the classical factors such as patient age and type of stroke, another factor contributing to this increased mortality rate might be the geographic dispersion of the region, with 3 million inhabitants (36% of the population) living outside urban areas in villages with small populations.

To treat these problems, Andalusia’s Public Health Service has recently developed a specialized stroke network, which includes a telestroke program (Centro Andaluz de Teleictus, CATI) to support acute stroke treatment decisions in remote areas (http://ictus-andalucia.com).

Aims

From a provider perspective, we aimed to examine the accessibility of specialized evaluation by a neurologist and the possibility of intravenous acute stroke treatment and quantify the changes in geographic stroke care accessibility after a centralized telestroke network was implemented in Andalusia.

Materials and methods

We conducted an observational study to compare the accessibility of specialized acute stroke care before and after the implementation of a telestroke network. Two phases were defined: the pre-implementation phase (12 months before January 2019) and the post-implementation phase (12 months after the whole network was implemented). Three types of centers were identified. In the pre-implementation stage, there were Comprehensive Stroke Centers (CSCs) and Stroke Units (SUs), and in the post-implementation phase, Telestroke Hospitals (THs) were added to the network.

With this aim, we conducted a geographic information system (GIS)-based network analysis using a geodatabase built from different sources. The unit of geographic analysis was the population nucleus (a set of at least ten buildings, forming streets, squares, and other urban roads, with a minimum of 50 people).

We used data from the Unified Digital Street Map of Andalucía (CDAU), which reflects the region’s road network, and we considered the priority given to ambulances in traffic circulation. We created vector layers for the map in GIS format to illustrate both the population centers and the hospital network, and we also associated each geographic nucleus with the population residing in it to discover how the population is spatially distributed. All these resources were imported into GIS to generate data and calculations of travel times and distances from the population centers to the THs.

To analyze the clinical impact of the change in accessibility of stroke care in these regions, data have been collected from different sources: For the pre-implementation phase, we collected retrospective data from the Minimum Basic Data Set (CMBD). The CMBD is an anonymized administrative record that contains a minimum set of clinical, demographic, and administrative variables that summarize what happens to a patient during a hospital visit. 12 For the post-implementation phase, we used data from the prospective monitoring registry on all teleconsultations received.

To calculate population access, we conducted a GIS-based network analysis using the Origin-Destination (OD) Cost Matrix method in the Network Analysis Extension of Esri ArcGIS software (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). The “New Service Area” method was used to create maps of the areas of influence according to preselected time intervals (less than 30 min, between 30 and 45 min, from 45 to 60 min, from 60 to 90 min, and more than 90 min) to a TH. We used spreadsheet software (Excel, Microsoft Office 365, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) to process the data generated in the network analysis and to compare the results before and after the implementation of the telestroke network.

In our region, picture archiving communication systems (PACS) and medical records are centralized 13 ; thus, the ease of granting access privileges to the neurologist was an advantage to creating a centralized network. A vascular neurologist was hired to coordinate the program and provide consultations in the morning shift. A pool of vascular neurologists from the different stroke centers was created to be on call for the remaining shift. As a result of this system, there is a vascular neurologist dedicated exclusively to providing 24/7 assistance in all teleconsultations for all THs. In addition to recommending the most appropriate treatment for each patient, the neurologist decides whether the patient should be transferred to an SU or CSC based on the patient’s individual needs and the resources available at each center at that time.

Owing to the convenience of having the entire population’s medical records already centralized, the requirements were minimal, consisting mainly of a videoconferencing system to allow communication between professionals. We provide a smartphone with a 4G connection to each center and on-call neurologist so that a neurological examination and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scoring could be performed by videoconference.

The study was approved by the regional ethical committee, PEIBA (Portal de Ética de la Investigación Biomédica de Andalucía) (protocol number: 1818-N-19).

Results

The development of the telestroke network started in December 2018.

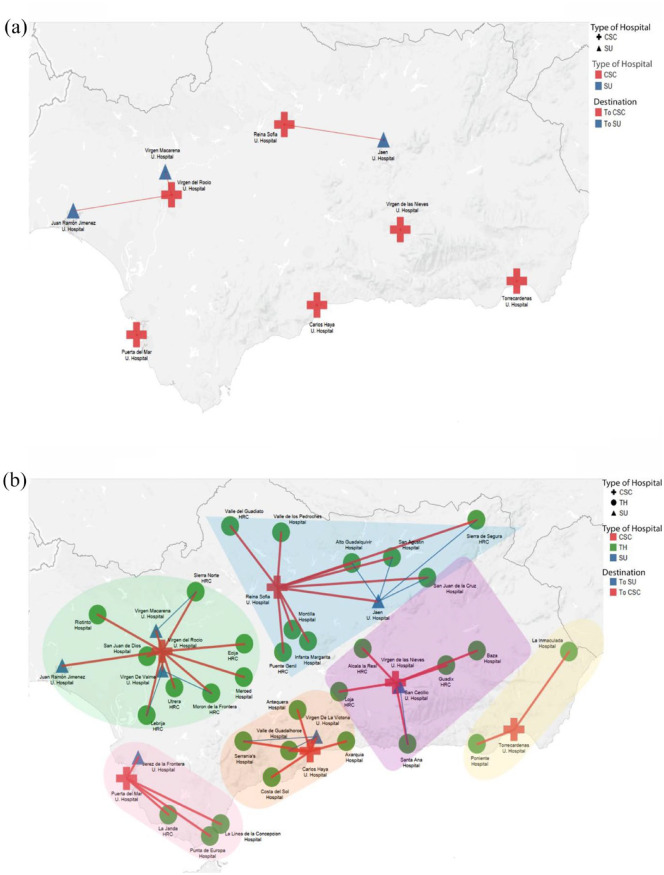

In the pre-implementation phase, there were three SUs with neurologists on call 24/7 and six CSCs that acted as thrombectomy hubs with the added possibility of endovascular treatment (EVT) 24/7, organized into six endovascular treatment nodes (Figure 1(a)). In summary, at this stage, Andalusia had 64 hospitals, of which only nine could provide neurologist-guided reperfusion treatments. To reorganize the stroke care network, we first carried out a GIS-based spatial analysis of the accessibility of specialized evaluation by a vascular neurologist for patients in our region to define how the centralized network could affect stroke care quality and access (Figure 2(a)). Forty-two centers capable of performing at least a simple CT and an emergency evaluation were identified, but they did not perform acute specialized stroke assessment routinely. With these data, we selected 30 hospitals to be included in the telestroke network. During the implementation phase, four of the centers that were originally THs established their own stroke units. Ultimately, the network encompassed a total of 40 centers with the capacity to indicate reperfusion treatments under the guidance of expert vascular neurologists.

Figure 1.

Organization in the (a) pre- and (b) post-implementation phases of telestroke network.

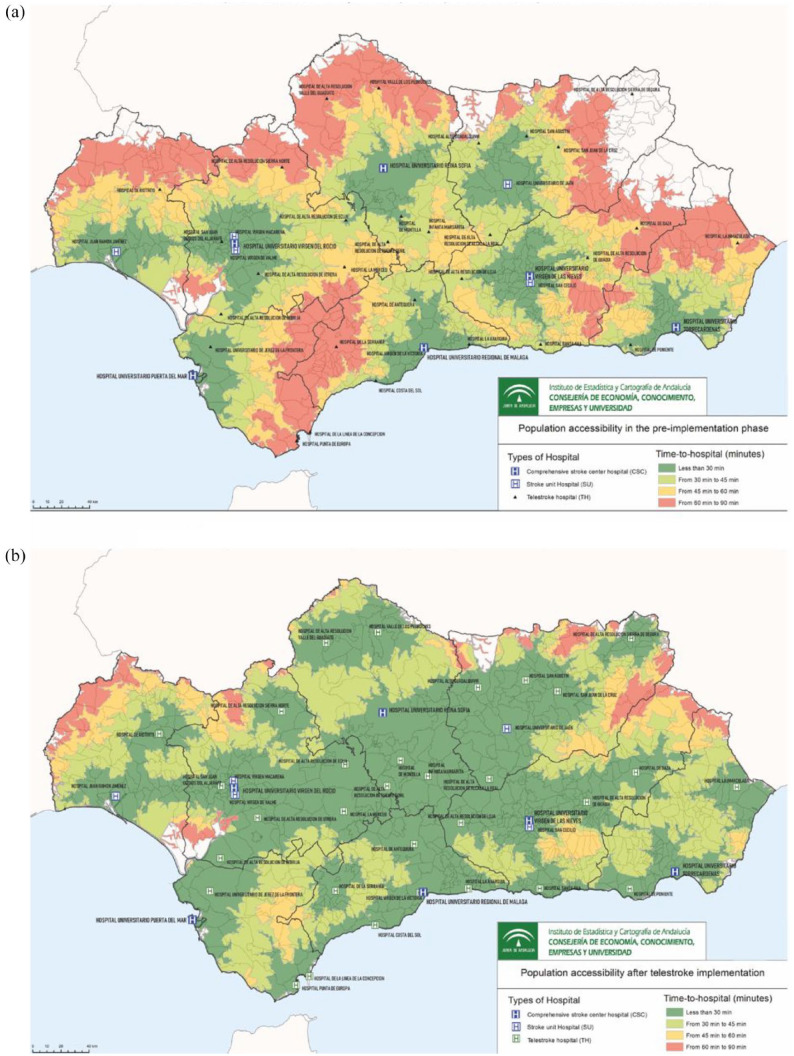

Figure 2.

Population access to specialized stroke care before and after the implementation of the telestroke network: (a) population accesibilty in the pre-implementation phase of telestroke network and (b) population accesibilty in the post-implementation phase of telestroke network.

In the pre-implementation period, based on all of the above data, 5,005,477 inhabitants (59.72% of the Andalusian population) had access to specialized stroke care within less than 30 minutes. In other words, 40% of the region’s population would take more than half an hour to reach a center where a stroke neurologist could attend them if a stroke was suspected, and 12% would take more than 90 min (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of population access to specialized stroke care in the pre- and post-implementation phases.

| Population | Pre-implementation Stage | Post-implementation Stage | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Less than 30 min | 5,005,477 (59.72%) | 7,832,988 (93.45%) | <0.001 |

| Less than 45 min | 6,335,019 (75.58%) | 8,306,080 (99.09%) | <0.001 |

| Less than 60 min | 7,302,781 (87.13%) | 8,374,660 (99.91) | <0.001 |

| Less than 90 min | 8,275,280 (88.58%) | 8,381,944 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Total | 8,381,944 (100%) | 8,381,944 (100%) |

In December 2018, a telestroke network based on the endovascular nodes was designed. The telestroke network has six mechanical thrombectomy nodes. Each node is composed of one CSC, one SU, and several telestroke spoke centers (THs). In this way, we expanded rapid access (<30 min) to an additional 3 million inhabitants (Figure 1(b)). The workflow of patient care in the final stroke network was established based on proximity and the pre-established relationships between centers.

The implementation stage lasted 5 months, beginning in January 2019. It included a gradual expansion by thrombectomy nodes. Each month, a new node was added while on-site training and rigorous quality monitoring were carried out.

After the implementation of the telestroke network, 7,832,988 (93.45%) inhabitants were located less than 30 min from a hospital capable of offering reperfusion therapies; this coverage represented a significant improvement in the field of influence (compared to 59.72% in the pre-implementation stage at less than 30 min, p < 0.001) (Figure 2(b)), bridging the gap of stroke care in rural hospitals. We also analyzed the technical equipment and human resources of THs at this stage to design our telestroke network.

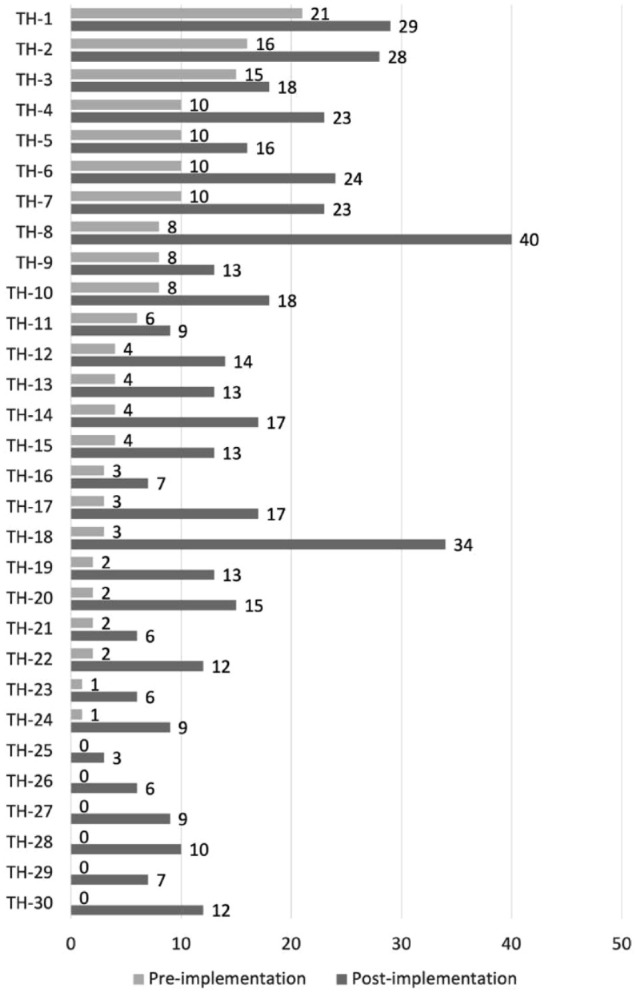

This improved access to evaluation by a vascular neurologist in the acute phase of stroke translated into clinical results. The total number of suspected strokes in the emergency departments (EDs) of all THs remained stable (2034 in the pre-implementation phase vs 1881 in the post-implementation phase). The telestroke consultations were performed in the case of previously non-disabled patients (mRS < 3) who were last seen well (LSW) less than 6 h prior (in some patients up to 24 h) or had an unknown onset time. A total of 1143 consultations were performed, of which 76% were ischemic strokes, 3% were hemorrhagic strokes, and 21% were stroke mimics. The mean number of yearly reperfusion treatments per TH significantly increased, from 7 in the pre-implementation period versus 15 in the post-implementation period (p < 0.001) (Figure 3). For all centers combined, the average number of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) procedures increased by 142% (92 vs 223), and the mean number of EVT procedures increased by 244% (65 vs 224). Additionally, EVTs of patients from THs in the pre-implementation period comprised 7% of all EVTs performed in the region, and this proportion rose to 20% after the complete network was implemented.

Figure 3.

Reperfusion treatments performed by THs per year before and after the implementation of the telestroke network.

Currently, the telestroke network is in a sustainable state. It provides approximately 1000 consultations per year, with a reperfusion treatment rate of almost 30% of all telestroke consultations. With the purpose of maintaining the best stroke care possible, a structure to provide monthly feedback has been created, continuous education and training for TH staff, and improved coordinating protocols and strategies have also been put in place.

Discussion

Recent advances in acute stroke therapy, such as endovascular treatment, new fibrinolytic drugs, and extended time windows, require individualized patient selection informed by specialized clinical knowledge and advanced neuroimaging techniques.6–8 These advances have led the scientific community to refocus on appropriate and timely patient transportation for evaluation and treatment. 14

Including geospatial variables such as patient location and travel times to treatment centers has many potential advantages in analyzing performance or modeling stroke treatment pathways. 15 The implementation phase of a stroke workflow requires support and planning in terms of government policy. 16 Our analysis has assisted our regional policy-makers with critical decisions by providing deep knowledge of the population-level situation regarding stroke care, answering questions such as where the new centers should be placed to serve a specified area, and breaking administrative barriers in the region to enable faster and better transportation of patients.

Ensuring very rapid access to acute stroke treatment for a whole population necessarily requires some administrative intervention. Our region contains some very large areas with low population density, under 50 persons per square kilometer; thus, one possible solution for our region would require a large number of hospitals. In contrast, providing 24/7 consultant-led services for stroke requires limits to be placed on the number of providers in order for each hospital to maintain the target admissions required to sustain a specialist service that operates 24/7. These two targets will always conflict, requiring careful evaluation to obtain the best balance between them. 17 We have found a solution to this problem with exclusive and centralized personnel assigned to attend the regional stroke network. In this way, the overload of care that can result from an increase in consultations is avoided, and unnecessary transfers to tertiary hospitals are reduced.

In Andalusia, the stroke code protocol states that the Emergency Prehospital Services should deliver any acute stroke patients to the nearest hospital at which a neurologist can perform an evaluation. There were four primary stroke centers with neurologists on call 24/7 and six CSCs with 24/7 EVT capabilities. In January 2018, the telestroke network was implemented, adding 30 centers capable of performing IVT after a specialized telemedicine evaluation by a vascular neurologist. Since then, the stroke code protocol has changed, and acute stroke patients are now delivered to the nearest hospital with the capacity to administer IVT.

Prior to the development of the telestroke network, only 87.13% of the Andalusian population was less than an hour from a center with the capacity for assessment by a vascular neurologist. After implementation, the percentage increased to 99.91%.

In recent years, this type of network analysis has been extended to the design of territorial planning strategies in public health. In some of these studies, the proportion of the population with access times of less than 30 min has improved by as much as 21%18–21; however, with our system, it has been possible to expand ultrafast access by 34% through the establishment of this centralized regional network.

This expansion of accessibility has been achieved in a short period and with few resources, consisting only of the cost of a vascular neurologist to coordinate the network in the morning shift (US$60,557 per year), an on-call vascular neurologist (US$152,169 per year), and the expenses of 4G smartphone connections and maintenance of the devices (US$2,087 per year). These costs add up a total fixed cost of US$214,813 per year. Having a dedicated neurologist enabled a rapid expansion of services, with an implementation phase of only 6 months until full operation across all 30 hospitals, as well as close monitoring of the results. With the whole network functioning, an average of 1000 consultations were performed each year. Based on data from the literature, 22 this program translates into savings of more than a million dollars a year.

The Spanish health care system is public, universal, and financed through taxes. Funding is transferred to regions; therefore, in this case, the hospitals and telestroke network, along with both the costs and the savings that can be generated by quality stroke care, are shared with the regional government of Andalusia.

Moreover, the centralized nature of the system allows specialized stroke neurologists rather than general neurologists to attend to patients. We expect this measure to result in better patient selection, greater adherence to protocols, higher rates of reperfusion treatment, fewer complications, and fewer unnecessary transfers than the previous system achieved.

To the best of our knowledge, our network has higher reperfusion rates than other established networks. 23 Although these data should be interpreted with caution, since the reperfusion rates reported in the literature refer to IVT rates a centralized telestroke network like CATI could be an efficient measure that might be considered for export to other regions with a similar demographic composition to break stroke access barriers and advance regional equity.

Other indirect potential benefits include the homogenization of stroke code care throughout the community, including indications for treatment even in controversial situations such as large vessel occlusions with low NIHSS or medium vessel occlusion; the homogenization of access to urgent neuroimaging examinations and their interpretation according to clinical examinations; and an increase in training in acute stroke care for general practitioners in rural areas.

Our study also has another strength: since the data to generate our model come from the regional government, they are updated regularly. Furthermore, in other studies, the analysis has been performed by ZIP code or municipality18–21; in our study, by using the population nucleus as the level of analysis, we achieve considerably better precision in that we can practically reach the residences of the inhabitants. As recommended by some studies,15,24 we use travel time calculations based on road networks and the actual speed limit of each road segment, which provide more realistic estimates of travel times and therefore help to more accurately identify neighborhoods that do not have timely access to stroke care. 25

Our study has some limitations. In the network analysis, we did not consider the possibility of air transport, as its use depends on factors such as weather and time of day. Additionally, we did not contemplate the possibility of delays in road transport, such as traffic jams, although the areas with the most problematic access do not usually have such traffic problems.

The focus of the study was how the access of the population to acute stroke care has improved with the establishment of the network; therefore, while mention is made of the annual cost of the network, we have not performed a robust analysis of the costs, since it would be necessary to take into account other factors that were far from the main objective of the study.

One of the main limitations of our analysis of how improved access impacts the population is that we had only aggregate data available in the regional CMBD rather than detailed data on stroke code patients in hospitals; accordingly, it was necessary to use different registries for the two groups. This makes it difficult to analyze the effect in each individual hospital. In fact, the lack of data on the absolute number of total strokes in each telestroke hospital regardless of telestroke activation implied that we could not provide data on real reperfusion rates. However, these aggregated data did allow us to see an overall improvement in reperfusion treatment rates over time.

Conclusion

A centralized telestroke network might be a low-cost tool to reduce differences in terms of barriers, resource needs, equitable access, and quality monitoring across different hospitals. Multidisciplinary work by clinicians, statisticians, and cartographers allows the development of new projects and tools to improve public health services—in this case, to modify the treatment of stroke, which is the main cause of mortality in the region for some segments of the population.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from PEIBA (Portal de Ética de la Investigación Biomédica de Andalucía) (protocol number: 1818-N-19).

Guarantor: JM.

Contributorship: AB, JM, and AG conceptualized and designed the study; AB and JM drafted the intellectual content of the manuscript; AB, JM, and SPS analyzed and interpreted the data; JMC and JMM performed the statistical analysis; all authors participated in data collection, reviewed, and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

ORCID iDs: Ana Barragán-Prieto  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9348-4643

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9348-4643

Inmaculada Villegas  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9243-1048

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9243-1048

Carlos de la Cruz Cosme  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5389-5106

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5389-5106

Joan Montaner  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4845-2279

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4845-2279

Data availability: Additional information or datasheets are available for other authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res 2017; 120: 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Struijs JN, van Genugten ML, Evers SM, et al. Future costs of stroke in the Netherlands: the impact of stroke services. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2006; 22: 518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aguiar de Sousa D, von Martial R, Abilleira S, et al. Access to and delivery of acute ischaemic stroke treatments: a survey of national scientific societies and stroke experts in 44 European countries. Eur Stroke J 2019; 4: 13–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kapral MK, Austin PC, Jeyakumar G, et al. Rural-urban differences in stroke risk factors, incidence, and mortality in people with and without prior stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2019; 12: e004973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021; 143: e254–e743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019; 50: e344–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turc G, Bhogal P, Fischer U, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) – European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) guidelines on mechanical thrombectomy in Acute Ischaemic StrokeEndorsed by Stroke Alliance for Europe (SAFE). Eur Stroke J 2019; 4: 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J 2021; 6: I–LXII. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hubert GJ, Santo G, Vanhooren G, et al. Recommendations on telestroke in Europe. Eur Stroke J 2019; 4: 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cayuela A, Cayuela L, Escudero-Martínez I, et al. Analysis of cerebrovascular mortality trends in Spain from 1980 to 2011. Neurología 2016; 31: 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montaner J, Jiménez-Hernández MD, López-Barneo J. How to unfasten the Spanish stroke belt? Andalusia chooses research. Int J Stroke 2014; 9: 946–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matías-Guiu J. Epidemiological research on stroke in Spain. Population-based studies or use of estimates from the minimum basic data set? Rev Esp Cardiol 2007; 60: 563–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muñoyerro-Muñiz D, Goicoechea-Salazar JA, García-León FJ, et al. Health record linkage: Andalusian health population database. Gac Sanit 2020; 34: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lima FO, Mont’Alverne FJA, Bandeira D, et al. Pre-hospital assessment of large vessel occlusion strokes: implications for modeling and planning stroke systems of care. Front Neurol 2019; 10: 955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Padgham M, Boeing G, Cooley D, et al. An introduction to software tools, data, and services for geospatial analysis of stroke services. Front Neurol 2019; 10: 743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Adeoye O, Nyström KV, Yavagal DR, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: a 2019 update: a policy statement from the American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019; 50: e187–e210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Allen M, Pearn K, Villeneuve E, et al. Planning and providing acute stroke care in England: the effect of planning footprint size. Front Neurol 2019; 10: 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kapral MK, Hall R, Gozdyra P, et al. Geographic access to stroke care services in rural communities in Ontario, Canada. Can J Neurol Sci 2020; 47: 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bray JE, Denisenko S, Campbell BCV, et al. Strategic framework improves access to stroke reperfusion across the state of Victoria Australia: improved access to stroke reperfusion. Intern Med J 2017; 47: 923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adeoye O, Albright KC, Carr BG, et al. Geographic access to acute stroke care in the United States. Stroke 2014; 45: 3019–3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kazley AS, Wilkerson RC, Jauch E, et al. Access to expert stroke care with telemedicine: REACH MUSC. Front Neurol 2012; 3: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Demaerschalk BM, Switzer JA, Xie J, et al. Cost utility of Hub-and-Spoke telestroke networks from societal perspective. Am J Manag Care 2013; 19: 976–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Müller-Barna P, Hubert GJ, Boy S, et al. TeleStroke units serving as a model of care in rural areas: 10-year experience of the TeleMedical Project for Integrative Stroke Care. Stroke 2014; 45: 2739–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Freyssenge J, Renard F, Schott AM, et al. Measurement of the potential geographic accessibility from call to definitive care for patient with acute stroke. Int J Health Geogr 2018; 17: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Busingye D, Pedigo A, Odoi A. Temporal changes in geographic disparities in access to emergency heart attack and stroke care: are we any better today? Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol 2011; 2: 247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]