Abstract

Background

Every year, an estimated one million children and young adolescents become ill with tuberculosis, and around 226,000 of those children die. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Xpert Ultra) is a molecular World Health Organization (WHO)‐recommended rapid diagnostic test that simultaneously detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and rifampicin resistance. We previously published a Cochrane Review 'Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assays for tuberculosis disease and rifampicin resistance in children'. The current review updates evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra in children presumed to have tuberculosis disease. Parts of this review update informed the 2022 WHO updated guidance on management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents.

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra for detecting: pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis, lymph node tuberculosis, and rifampicin resistance, in children with presumed tuberculosis.

Secondary objectives

To investigate potential sources of heterogeneity in accuracy estimates. For detection of tuberculosis, we considered age, comorbidity (HIV, severe pneumonia, and severe malnutrition), and specimen type as potential sources.

To summarize the frequency of Xpert Ultra trace results.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, MEDLINE, Embase, three other databases, and three trial registers without language restrictions to 9 March 2021.

Selection criteria

Cross‐sectional and cohort studies and randomized trials that evaluated Xpert Ultra in HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative children under 15 years of age. We included ongoing studies that helped us address the review objectives. We included studies evaluating sputum, gastric, stool, or nasopharyngeal specimens (pulmonary tuberculosis), cerebrospinal fluid (tuberculous meningitis), and fine needle aspirate or surgical biopsy tissue (lymph node tuberculosis). For detecting tuberculosis, reference standards were microbiological (culture) or composite reference standard; for stool, we also included Xpert Ultra performed on a routine respiratory specimen. For detecting rifampicin resistance, reference standards were drug susceptibility testing or MTBDRplus.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and, using QUADAS‐2, assessed methodological quality judging risk of bias separately for each target condition and reference standard. For each target condition, we used the bivariate model to estimate summary sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We stratified all analyses by type of reference standard. We summarized the frequency of Xpert Ultra trace results; trace represents detection of a very low quantity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA. We assessed certainty of evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We identified 14 studies (11 new studies since the previous review). For detection of pulmonary tuberculosis, 335 data sets (25,937 participants) were available for analysis. We did not identify any studies that evaluated Xpert Ultra accuracy for tuberculous meningitis or lymph node tuberculosis. Three studies evaluated Xpert Ultra for detection of rifampicin resistance. Ten studies (71%) took place in countries with a high tuberculosis burden based on WHO classification. Overall, risk of bias was low.

Detection of pulmonary tuberculosis

Sputum, 5 studies

Xpert Ultra summary sensitivity verified by culture was 75.3% (95% CI 64.3 to 83.8; 127 participants; high‐certainty evidence), and specificity was 97.1% (95% CI 94.7 to 98.5; 1054 participants; high‐certainty evidence).

Gastric aspirate, 7 studies

Xpert Ultra summary sensitivity verified by culture was 70.4% (95% CI 53.9 to 82.9; 120 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and specificity was 94.1% (95% CI 84.8 to 97.8; 870 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Stool, 6 studies

Xpert Ultra summary sensitivity verified by culture was 56.1% (95% CI 39.1 to 71.7; 200 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and specificity was 98.0% (95% CI 93.3 to 99.4; 1232 participants; high certainty‐evidence).

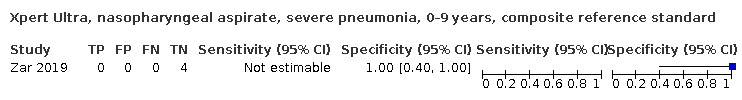

Nasopharyngeal aspirate, 4 studies

Xpert Ultra summary sensitivity verified by culture was 43.7% (95% CI 26.7 to 62.2; 46 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), and specificity was 97.5% (95% CI 93.6 to 99.0; 489 participants; high‐certainty evidence).

Xpert Ultra sensitivity was lower against a composite than a culture reference standard for all specimen types other than nasopharyngeal aspirate, while specificity was similar against both reference standards.

Interpretation of results

In theory, for a population of 1000 children:

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in sputum (by culture):

‐ 101 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 26 (26%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 899 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 25 (3%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in gastric aspirate (by culture):

‐ 123 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 53 (43%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 877 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 30 (3%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in stool (by culture):

‐ 74 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 18 (24%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 926 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 44 (5%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in nasopharyngeal aspirate (by culture):

‐ 66 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 22 (33%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 934 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 56 (6%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

Detection of rifampicin resistance

Xpert Ultra sensitivity was 100% (3 studies, 3 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), and specificity range was 97% to 100% (3 studies, 128 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

Trace results

Xpert Ultra trace results, regarded as positive in children by WHO standards, were common. Xpert Ultra specificity remained high in children, despite the frequency of trace results.

Authors' conclusions

We found Xpert Ultra sensitivity to vary by specimen type, with sputum having the highest sensitivity, followed by gastric aspirate and stool. Nasopharyngeal aspirate had the lowest sensitivity. Xpert Ultra specificity was high against both microbiological and composite reference standards. However, the evidence base is still limited, and findings may be imprecise and vary by study setting. Although we found Xpert Ultra accurate for detection of rifampicin resistance, results were based on a very small number of studies that included only three children with rifampicin resistance. Therefore, findings should be interpreted with caution. Our findings provide support for the use of Xpert Ultra as an initial rapid molecular diagnostic in children being evaluated for tuberculosis.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Humans; Antibiotics, Antitubercular; Antibiotics, Antitubercular/therapeutic use; Cross-Sectional Studies; HIV Infections; HIV Infections/drug therapy; Microbial Sensitivity Tests; Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Mycobacterium tuberculosis/genetics; Rifampin; Rifampin/pharmacology; Sensitivity and Specificity; Sputum; Sputum/microbiology; Tuberculosis, Lymph Node; Tuberculosis, Lymph Node/diagnosis; Tuberculosis, Lymph Node/drug therapy; Tuberculosis, Meningeal; Tuberculosis, Meningeal/cerebrospinal fluid; Tuberculosis, Meningeal/diagnosis; Tuberculosis, Meningeal/drug therapy; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/diagnosis; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/drug therapy; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary/microbiology

Plain language summary

Xpert Ultra for diagnosing tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in children

Why is improving the diagnosis of tuberculosis important?

Every year, an estimated one million children and young adolescents become ill with tuberculosis, and around 226,000 die from the disease. Tuberculosis is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and mostly affects the lungs (pulmonary tuberculosis), though it can affect other sites in the body (extrapulmonary tuberculosis). Signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis include cough, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Signs and symptoms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis depend on the site of disease. When detected early and treated effectively, tuberculosis is largely curable.

Not recognizing tuberculosis (false negative) early may result in delayed diagnosis and treatment, severe illness, and death. An incorrect tuberculosis diagnosis (false positive) may result in anxiety, unnecessary treatment (which can involve medication side effects), and the possibility of missing alternative diagnoses which warrant treatment.

What was the aim of this review?

To determine the accuracy of Xpert Ultra in children with symptoms of tuberculosis for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis (affecting membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord), lymph node tuberculosis (a painful swelling of one or more lymph nodes, which are bean‐shaped structures that help fight infection), and rifampicin resistance.

What did this review study?

Xpert Ultra, a World Health Organization‐recommended rapid test that simultaneously detects tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults and children with tuberculosis symptoms. Rifampicin is an important medicine used to treat tuberculosis. For tuberculosis diagnosis, we assessed results against two different benchmarks: tuberculosis culture (a method used to grow bacteria on nutrient‐rich media) and a composite definition based on symptoms, chest X‐ray, sputum microscopy (examination under a microscope of mucus and other matter coughed up from the lungs), and culture. For rifampicin resistance detection, we assessed results against drug susceptibility testing or line probe assay (a rapid laboratory‐based test for detecting tuberculosis bacteria).

What were the main results in this review?

We included 14 studies. For pulmonary tuberculosis, we analysed 335 data sets (around 26,000 participants). No studies evaluated Xpert Ultra accuracy for tuberculous meningitis or lymph node tuberculosis. Three studies evaluated Xpert Ultra accuracy for detection of rifampicin resistance.

For a population of 1000 children:

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in sputum according to culture results:

‐ 101 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 26 (26%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 899 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 25 (3%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in gastric aspirate (collection of lung and oral secretions from the stomach) according to culture results:

‐ 97 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 27 (28%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 903 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 30 (3%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in stool according to culture results:

‐ 74 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive and of these, 18 (24%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 926 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 44 (5%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

• where 100 have pulmonary tuberculosis in nasopharyngeal aspirate (secretions from the uppermost part of the throat, behind the nose) according to culture results:

‐ 66 would be Xpert Ultra‐positive, and of these, 22 (33%) would not have pulmonary tuberculosis (false positive); and ‐ 934 would be Xpert Ultra‐negative, and of these, 56 (6%) would have tuberculosis (false negative).

Xpert Ultra accurately detected rifampicin resistance, but there were few studies and only three children with rifampicin resistance included.

How confident are we in the results of this review?

For pulmonary tuberculosis, we are fairly confident because we included studies from different countries and used two different benchmarks, though neither is perfect. However, the evidence base is still limited and there were few studies with few children for one of the specimen types (nasopharyngeal aspirate).

For rifampicin resistance, we identified few studies with very few children with rifampicin resistance, so we are less confident.

What children do the results of this review apply to?

Children and young adolescents (birth to 14 years) who are HIV‐positive or HIV‐negative, with signs or symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis. The results also apply to children with severe pneumonia or malnutrition and tuberculosis symptoms. In this review, we did not identify any studies that evaluated Xpert Ultra accuracy for tuberculous meningitis or lymph node tuberculosis.

What are the implications of this review?

The results suggest that Xpert Ultra in sputum, gastric aspirate, stool, and nasopharyngeal aspirate is an accurate method for detecting pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in children.

Using Xpert Ultra in sputum, gastric aspirate, stool, and nasopharyngeal aspirate, the risk of missing a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis (confirmed by culture) is low, suggesting that only a small number of children will not receive treatment. The risk of incorrectly diagnosing a child as having pulmonary tuberculosis is slightly higher. This may result in some children receiving unnecessary treatment.

How up to date is this review?

This review updates our previous review and includes evidence published up to 9 March 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Xpert Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis in childrena.

| Review question: what is the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis in children with signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis? | |||||||

|

Patients/population: children with presumed pulmonary tuberculosis Index tests: Xpert Ultra Role: an initial test Threshold for index tests: an automated result is provided Reference standard: culture Types of studies: cross‐sectional and cohort studies Setting: primary care facilities and local hospitals | |||||||

| Specimen | Effect (95% Cl) | Number of participants (studies) | Test result | Number of results per 1000 patients tested(95% CI)b | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | ||

| Prevalence 1% | Prevalence 10% | Prevalence 20% | |||||

| Sputum | Summary sensitivity 75.3% (64.3 to 83.8) | 127 (5) | True positive | 8 (6 to 8) |

75 (64 to 84) |

151 (129 to 168) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| False negative | 2 (2 to 4) |

25 (16 to 36) |

49 (32 to 71) |

||||

| Summary specificity 97.1% (94.7 to 98.5) | 1054 (5) | True negative | 961 (938 to 975) |

874 (852 to 887) |

777 (758 to 788) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

|

| False positive | 29 (15 to 52) |

26 (13 to 48) |

23 (12 to 42) |

||||

| Gastric aspirate | Summary sensitivity 70.4% (53.9 to 82.9) | 120 (7) | True positive | 7 (5 to 8) |

70 (54 to 83) |

141 (108) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| False negative | 3 (2 to 5) |

30 (17 to 46) |

59 (34 to 92) |

||||

| Summary specificity 94.1% (84.8 to 97.8) | 870 (7) | True negative | 932 (840 to 968) |

847 (763 to 880) |

753 (678 to 782) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderated |

|

| False positive | 58 (22 to 150) |

53 (20 to 137) |

47 (18 to 122) |

||||

| Stool | Summary sensitivity 56.1% (39.1 to 71.7) | 200 (6) | True positive | 6 (4 to 7) |

56 (39 to 72) |

112 (78 to 143) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| False negative | 4 (3 to 6) |

44 (28 to 61) |

88 (57 to 122) |

||||

| Summary specificity 98.0% (93.3 to 99.4) | 1232 (6) | True negative | 970 (924 to 984) |

882 (840 to 895) |

784 (746 to 795) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

|

| False positive | 20 (6 to 66) |

18 (5 to 60) |

16 (5 to 54) |

||||

| Nasopharyngeal aspirate | Summary sensitivity 43.7% (26.7 to 62.2) |

46 (4) | True positive | 4 (3 to 6) |

44 (27 to 62) |

87 (53 to 124) |

⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowe,f |

| False negative | 6 (4 to 7) |

56 (38 to 73) |

113 (76 to 147) |

||||

| Summary specificity 97.5 (93.6 to 99.0) |

489 (4) | True negative | 965 (927 to 980) |

878 (842 to 891) |

780 (749 to 792) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

|

| False positive | 25 (10 to 63) |

22 (9 to 58) |

20 (8 to 51) |

||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

CI: confidence interval. aThe results presented in this table should not be interpreted in isolation from the results of individual included studies contributing to each summary test accuracy measure. bPrevalence levels were suggested by the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme. cDowngraded one level for imprecision due to wide 95% CI. dDowngraded one level for inconsistency as specificity ranged from 78% to 100%, and several 95% CIs did not overlap. eDowngraded one level for indirectness as only two studies (50%) were of low concern regarding applicability (patients enrolled from outpatient or non‐referral settings). fDowngraded two levels for imprecision due to wide 95% CI and because a small number of participants contributed to the analysis for sensitivity.

Summary of findings 2. Xpert Ultra for rifampicin resistancea.

| Review question: what is the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra for rifampicin resistance in children with signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis? | |||||||

|

Patients/population: children with presumed pulmonary tuberculosis Index tests: Xpert Ultra Role: an initial test Threshold for index tests: an automated result is provided Reference standard: culture‐based phenotypic drug susceptibility testing and MTBDRplus Types of studies: cross‐sectional and cohort studies Setting: primary care facilities and local hospitals Limitations: the findings are based on 3 studies. Each study included only 1 participant with rifampicin resistance | |||||||

| Specimen | Effect (95% Cl) | Number of participants (studies) | Test result | Number of results per 1000 patients tested(95% CI)b | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | ||

| Prevalence 2% | Prevalence 10% | Prevalence 15% | |||||

| All specimens | Sensitivity range 100% to 100% | 3 (3) | True positive | 20 to 20 | 100 to 100 | 150 to 150 | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowc,d,e |

| False negative | 0 to 0 | 0 to 0 | 0 to 0 | ||||

| Specificity range 97% to 100% | 128 (3) | True negative | 951 to 980 | 873 to 900 | 825 to 850 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowc,d |

|

| False positive | 0 to 29 | 0 to 27 | 0 to 25 | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

CI: confidence interval. aThe results presented in this table should not be interpreted in isolation from the results of individual included studies contributing to each summary test accuracy measure. bPrevalence levels were suggested by the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme. cDowngraded one level for risk of bias because in one study the manner of participant selection was unclear, and in another, not all participants were included in the analysis. dDowngraded one level for indirectness because thethree included studies took place in China, Italy, and South Africa, and applicability to other settings is uncertain. eDowngraded two levels for imprecision because only three participants with rifampicin resistance contributed to this analysis for the observed sensitivity.

Background

Tuberculosis is the 13th leading cause of death and the second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent after COVID‐19 (WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2021). Globally, in 2020, an estimated 10 million people developed tuberculosis disease, including around 1.1 million children younger than 15 years of age, and 226,100 children (205,000 HIV‐negative and 21,100 HIV‐positive children) died from the disease (WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2021). Globally, in 2020, 53% of HIV‐negative people who died from tuberculosis were men, 32% were women, and 16% were children younger than 15 years of age. The higher proportion of children who die from tuberculosis compared with their estimated share of cases (11%) suggests poorer access to diagnosis and treatment (WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2021). The toll on younger children is especially tragic. One systematic review that investigated tuberculosis mortality in children found higher case fatality ratios in children from birth to four years of age compared with children aged five to 14 years (Jenkins 2017). Recent epidemiological models that have been accepted and supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) suggest that there is substantial under‐reporting as well as underdiagnosis of tuberculosis in children (Dodd 2017).

Tuberculosis treatment for children follows the same principles as for adults, and the same drugs are used in most cases. The standard treatment for drug‐susceptible tuberculosis – both pulmonary and extrapulmonary forms – is a four‐drug combination regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol given daily for two months, followed by isoniazid and rifampicin given daily for an additional two to four months. Central nervous system and osteoarticular tuberculosis constitute an exception in that treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin is extended for a total of 12 months. The introduction of paediatric fixed‐dose combinations with optimized dosing and taste masking has improved the efficiency of treatment (Wademan 2019). Treatment of drug‐resistant tuberculosis in children generally has better outcomes than in adults (Harausz 2018). Of note, in 2020, the WHO released consolidated guidelines on the treatment of drug‐resistant tuberculosis in children and adults, containing new recommendations for the treatment of child drug‐resistant tuberculosis, including the use of all‐oral regimens (Furin 2019; WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 4) 2020).

The diagnosis of child tuberculosis relies on a mix of clinical, epidemiological, radiological, and laboratory information. Child tuberculosis is typically paucibacillary (tuberculosis disease caused by a smaller number of bacteria), and young children cannot voluntarily produce sputum specimens (Marais 2005; Theart 2005). Hence, even under ideal clinical and laboratory conditions, only 30% to 40% of children with tuberculosis have bacteriological confirmation of disease (Dunn 2016). The probability of microbiological confirmation is increased in children with more severe or advanced disease (Marais 2006a; Marais 2006b). However, the diagnostic gap is perpetuated because conventional smear microscopy, which is of limited value in diagnosing child tuberculosis and is no longer recommended by the WHO for diagnosis, remains the most used and most widely available tuberculosis diagnostic method in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Further, the clinical skills and equipment needed for sputum induction and gastric aspiration are often not available in peripheral (subdistrict and community level) health clinics (Reid 2012). Compared with microscopy, tuberculosis culture methods have shown greater, yet highly variable, sensitivity in child tuberculosis (Chiang 2017; Frigati 2015). Unfortunately, tuberculosis culture to support diagnosis is not widely available in high‐burden settings.

The development of Xpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), a rapid molecular diagnostic test that simultaneously detects Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M tuberculosis) complex and rifampicin resistance), was a major step towards improving detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance worldwide. However, Xpert MTB/RIF sensitivity is suboptimal in people with smear‐negative tuberculosis, and particularly in children, people living with HIV, and people with extrapulmonary tuberculosis (Horne 2019;Kay 2020; Kohli 2021; Zifodya 2021). To overcome these limitations, Cepheid developed Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Xpert Ultra), a re‐engineered assay using a newly developed cartridge that is run on the same device (GeneXpert) after a software upgrade (see Index test(s)).

This Cochrane Review update assessed the accuracy of Xpert Ultra for detecting pulmonary tuberculosis, specific forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (i.e. tuberculous meningitis and lymph node tuberculosis), and rifampicin resistance in children presumed to have tuberculosis, using sputum, gastric aspirate, nasopharyngeal aspirate, or stool specimens.

Current WHO recommendations on the use of Xpert Ultra related to this review update are presented in Table 3 and the WHO Consolidated Guidelines (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 3) 2021; WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 5) 2022).

1. Current World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic recommendations in children.

| WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 3) 2021a |

| In children with signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, Xpert Ultra should be used as the initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis and detection of rifampicin resistance in sputum or nasopharyngeal aspirate, rather than smear microscopy/culture and phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (strong recommendation, low certainty of evidence for test accuracy in sputum; very low certainty of evidence for test accuracy in nasopharyngeal aspirate). |

| In children with signs and symptoms of tuberculous meningitis, Xpert MTB/RIF or Xpert Ultra should be used in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as an initial diagnostic test for tuberculous meningitis rather than smear microscopy/culture (strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence for test accuracy for Xpert MTB/RIF; low certainty of evidence for test accuracy for Xpert Ultra). |

| In children with signs and symptoms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Xpert Ultra may be used in lymph node aspirate and lymph node biopsy as the initial diagnostic test rather than smear microscopy/culture (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence). |

| In children with presumed pulmonary tuberculosis and an initial Xpert Ultra‐negative result, in settings with a pretest probability of 5% or more, the WHO recommends a repeat Xpert Ultra test (for a total of two tests). Sputum and nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens may be used (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence for test accuracy). |

| WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 5) 2022b |

| In children aged below 10 years with signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra should be used in gastric aspirate or stool specimens as the initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis and the detection of rifampicin resistance, rather than smear microscopy/culture and phenotypic drug susceptibility testing. |

aThe findings from Kay 2020 informed development of the guidelines. bThe findings from this review update informed development of the guidelines.

Target condition being diagnosed

There are four target conditions: active pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis, lymph node tuberculosis, and rifampicin resistance.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by bacteria within the M tuberculosis complex, most commonly M tuberculosis. Typically disseminated through the air, M tuberculosis predominantly affects the lungs, causing pulmonary tuberculosis, and less typically can cause disease in other organs of the body in extrapulmonary tuberculosis forms. For this review, we limited evaluation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis to lymph node tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis. Lymph node tuberculosis is the most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in children (Marais 2006e), and tuberculous meningitis results in the highest morbidity and mortality (Marais S 2010).

The natural history of tuberculosis in children is distinct from that in adults, due to more frequent progression to primary tuberculosis disease (Marais 2004). Children younger than five years of age are at particularly high risk of progression to tuberculous disease following infection, but the risk for older children and adolescents is also higher than in adults. Overall, it is estimated that 90% of tuberculous disease in young children occurs within one year of infection (Marais 2014). In addition to age, factors such as nutritional status, immune‐compromising conditions (e.g. HIV infection), bacillus Calmette‐Guérin (BCG)‐vaccination status, and genetic susceptibility contribute to children's risk of disease progression. Immediately following infection with M tuberculosis in a child, haematogenous spread (by way of the bloodstream) can occur. The period of highest risk for presentation with tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis is one to three months following primary infection. Children between six months and two years of age are at particularly high risk of these severe forms of tuberculous disease. Approximately 50% of children in this age range progress to tuberculous disease following infection, and 20% to 40% of those children will present with disseminated disease (Marais 2004; Marais 2014). Children younger than five years of age most commonly present with hilar lymph node forms of intrathoracic tuberculous disease. Older children and adolescents more commonly manifest adult‐type disease, including pleural tuberculosis and upper lobe consolidations (Marais 2004).

Laboratory confirmation of tuberculosis in children is challenging for two reasons. First, child tuberculosis most commonly represents as a primary disease process, without the formation of cavities (Marais 2006c). The number of acid‐fast bacilli (the presence of acid‐fast bacilli on a sputum smear or other specimen usually indicates tuberculous disease) present in forms of primary tuberculosis such as hilar lymph node or bronchial tuberculosis is substantially lower than the number present in a pulmonary cavity. Consequently, child tuberculosis is often referred to as 'paucibacillary', and it is more difficult to obtain the organisms needed to confirm disease via conventional smear (no longer recommended) or culture (Dunn 2016). Second, most children younger than six years of age lack the ability to expectorate sputum and are unable to voluntarily produce good‐quality specimens. Therefore, respiratory specimens are often obtained through sputum induction. As children swallow respiratory secretions, early‐morning gastric aspiration is another well‐established (yet still invasive) approach to specimen collection. In one study, the yield of three consecutive morning gastric aspirates was similar to the yield of one induced sputum specimen (Zar 2005). Nasopharyngeal aspiration for respiratory specimens is a less invasive mode of specimen collection (Zar 2012). Stool has also been studied as a child tuberculosis diagnostic specimen; although sensitivity has been lower than with traditional specimens, this specimen has great appeal because collection is non‐invasive and requires no training (Nicol 2014). Because laboratory diagnostics for tuberculosis perform poorly in children, algorithms involving signs, symptoms, tuberculosis exposure, HIV status, laboratory tests, and radiographic findings are commonly used to make a clinical diagnosis of child tuberculosis. However, these algorithms have been shown to perform differently across settings, and their sensitivity and specificity may be site‐specific (David 2017).

Rifampicin resistance

Rifampicin‐resistant tuberculosis is caused by M tuberculosis strains resistant to rifampicin, a critical first‐line tuberculosis drug (see Index test(s)). These strains may be susceptible or resistant to isoniazid (i.e. multidrug‐resistant (MDR) tuberculosis), or resistant to other first‐line or second‐line tuberculosis drugs (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 4) 2020). People with drug‐resistant tuberculosis can transmit the infection to others. The drugs used to treat drug‐resistant tuberculosis are less potent and more toxic than the drugs used to treat drug‐susceptible tuberculosis. The WHO has issued recommendations that all individuals with MDR or rifampicin‐resistant tuberculosis, including those who are also resistant to fluoroquinolones, may benefit from all‐oral treatment regimens (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 4) 2020).

Index test(s)

The index test is Xpert Ultra (Cepheid Inc, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Xpert Ultra is a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) that functions as an automated closed system that performs real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Specimens are processed using Xpert Sample Reagent and are incubated for 15 minutes, after which the processed samples are pipetted into the cartridge. These tests can be run by operators (such as laboratory technicians and nurses) with minimal technical expertise. Within two hours, the test detects both live and dead M tuberculosis complex DNA and simultaneously recognizes mutations in the M tuberculosis gene encoding the beta subunit of the ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase (rpoB) gene, which is the most common site of M tuberculosis mutations leading to rifampicin resistance. Xpert Ultra uses the same platform (GeneXpert) as Xpert MTB/RIF. Xpert Ultra requires an uninterrupted and stable electrical power supply, temperature control, and yearly calibration of the cartridge modules. The WHO has published extensive guidance and practical information on implementing the test (WHO Operational handbook on tuberculosis 2021).

Xpert Ultra was designed to improve the sensitivity to detect M tuberculosis complex and reliability for detection of rifampicin resistance (WHO Operational handbook on tuberculosis 2021). To improve tuberculosis detection, Xpert Ultra incorporates two different multicopy amplification targets (IS6110 and IS1081) and a larger chamber for the PCR reaction. To improve rifampicin resistance detection, Xpert Ultra is based on melting temperature analysis. These revisions have resulted in an approximately 1‐log improvement in the lower limit of detection compared with Xpert MTB/RIF, as well as improved differentiation of certain silent mutations and improved detection of rifampicin resistance in mixed infections (Chakravorty 2017; WHO Operational handbook on tuberculosis 2021). At very low bacterial loads, Xpert Ultra can give a trace result (considered a positive bacteriologic result in children and people living with HIV), though trace does not provide a result for rifampicin susceptibility or resistance. Studies have found that the increase in Xpert Ultra sensitivity for tuberculosis detection has been accompanied by a decrease in specificity, and that Xpert Ultra may be more likely to identify M tuberculosis DNA from prior episodes of tuberculosis, particularly in people with a trace result (Dorman 2018; Mishra 2020). Despite clear guidance in children, Xpert Ultra trace results can complicate decision‐making, and clinical management of trace results is rarely straightforward.

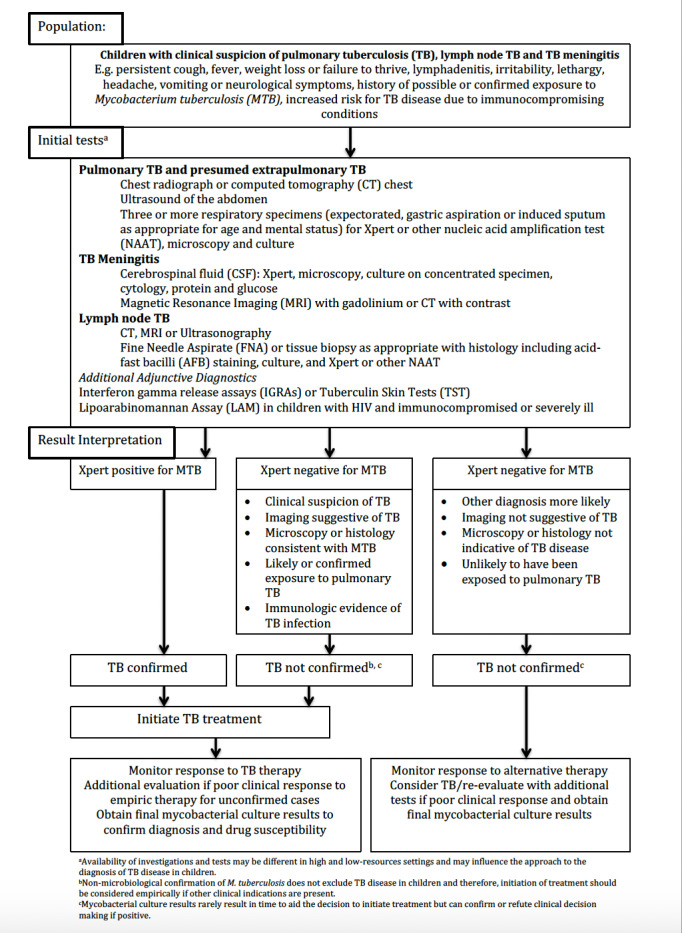

Clinical pathway

Figure 1 presents an example of the clinical pathway and placement of the index test. A careful clinical history of tuberculosis exposure and symptoms is the first step in the diagnostic pathway for child tuberculosis. Children with household or other close and persistent exposure to a person with tuberculosis are at increased risk of tuberculosis infection and resultant progression to tuberculosis disease. All children with recent exposure to tuberculosis must be evaluated for clinical symptoms and for examination findings consistent with tuberculous disease. Additional testing depends on the context but may include chest radiography and a test of tuberculosis infection. Symptoms of tuberculosis disease generally persist for longer than two weeks and are unremitting (Marais 2005). The most common symptoms are cough, fever, decreased appetite, weight loss or failure to thrive, and fatigue or reduced playfulness. Symptoms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis are typically localized, and diagnostic findings are generally obtained from the site of disease (Figure 1). However, no symptom‐based diagnostic algorithms have been validated or shown to be reliable in multiple contexts. Symptom‐based diagnostic algorithms tend to perform poorly in children younger than three years of age and in HIV‐positive children: two populations at high risk for disease progression (Marais 2006d).

1.

Clinical pathway of Xpert Ultra in children presumed to have tuberculosis

Unfortunately, no clinical examination features are specific to pulmonary tuberculosis in children. However, examination findings in extrapulmonary tuberculosis can be quite specific when identified. Clinicians should consider medical comorbidities that increase the risk for tuberculous disease, and should modify diagnostic algorithms accordingly. HIV infection not only significantly increases risk of tuberculosis in children, it also raises the risk of increased disease severity. HIV‐positive children, especially before effective antiretroviral therapy is established, often present with advanced tuberculosis, such as disseminated disease, and have high levels of immunosuppression, further complicating diagnosis and management.

Additional diagnostic imaging studies can assist in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis and nearly all forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tests for tuberculosis infection, such as interferon gamma release assays or tuberculin skin tests, can also aid in establishing the probability of tuberculosis (disease) in a child but are not necessary to make the diagnosis. Diagnostic recommendations strongly suggest collecting appropriate specimens from suspected sites of involvement in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis for microbiological examination. The preferred specimen in pulmonary tuberculosis is sputum; however, in young children who cannot expectorate, the specimen is commonly obtained via a gastric aspirate or induced sputum, and stool is increasingly used. To diagnose extrapulmonary tuberculosis, sample collection targets the affected site of disease.

The purpose of Xpert Ultra testing is diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis and detection of rifampicin resistance. Results of Xpert Ultra can be used as a decision‐making tool in the following ways.

M tuberculosis detected and rifampicin resistance not detected: child would start treatment for drug‐sensitive tuberculosis.

M tuberculosis detected and rifampicin resistance detected: child would need further testing for drug resistance and would start treatment for drug‐resistant tuberculosis according to country guidelines.

M tuberculosis not detected: a negative Xpert Ultra result does not rule out tuberculosis disease; therefore, clinicians should still consider initiation of tuberculosis treatment in children with history and clinical or radiological features suggestive of tuberculosis disease despite a negative Xpert Ultra result. A negative Xpert Ultra result may also represent a true negative.

Possible consequences of a false‐positive and a false‐negative result may include the following.

False positive: children (and their families) would likely experience anxiety and morbidity caused by additional testing, unnecessary treatment, and possible adverse effects; as well as missed time from school, possible stigma associated with tuberculosis or a diagnosis of drug‐resistant tuberculosis, and the chance that a false‐positive may halt further diagnostic evaluation for other causes of illness. Families also experience unnecessary expense, as well as the risk of missing an important alternative diagnosis.

False negative: would imply increased risk of morbidity and mortality and delayed start of treatment.

Role of index test(s)

For tuberculosis detection, the index test would be used as an initial test, replacing standard practice (i.e. smear microscopy or culture). For detection of rifampicin resistance, the index test would replace culture‐based drug susceptibility testing as the initial test.

Alternative test(s)

Here we summarize selected alternative tests.

Truenat technologies (Molbio Diagnostics, Goa, India) are rapid molecular assays that can detect tuberculosis (Truenat MTB and MTB Plus assays) and rifampicin resistance (Truenat MTB‐RIF Dx assay) from sputum specimens with results reported in less than one hour (WHO Operational handbook on tuberculosis 2021). Truenat MTB and MTB Plus assays use chip‐based PCR for detection of M tuberculosis complex; if a result is positive, a sample of the already extracted DNA may be run on the chip‐based Truenat MTB‐RIF Dx assay to detect mutations associated with rifampicin resistance (WHO Operational handbook on tuberculosis 2021). The assays use portable, battery‐operated devices. The WHO includes Truenat assays in the category 'molecular WHO‐recommended rapid diagnostic tests that can detect tuberculosis (mWRD)' and recommends their use as follows (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 3) 2021).

In adults and children with signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, the Truenat MTB or MTB Plus may be used as an initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis rather than smear microscopy/culture (conditional recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence for test accuracy).

In adults and children with signs and symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis and a Truenat MTB or MTB Plus positive result, Truenat MTB‐RIF Dx may be used as an initial test for rifampicin resistance rather than culture and phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence for test accuracy).

Additional alternative approaches for diagnosis of tuberculosis are still used extensively world. Main tests include examination of smear for acid‐fast bacilli (tuberculosis bacteria) under a microscope (light microscopy, using the classical Ziehl‐Neelsen staining technique), fluorescence microscopy, and light‐emitting diode (LED)‐based fluorescence microscopy (no longer recommended by the WHO for diagnosis but used for monitoring in adults). The sensitivity of smear microscopy ranges from 0% to 10% in children (Kunkel 2016). Examination of histology specimens under a microscope following a tissue biopsy targets acid‐fast bacilli and granulomatous inflammation, frequently with caseous necrosis (necrotizing granulomas); however these options are seldom pursued to diagnose child tuberculosis in low‐resource settings due to the invasive nature of the procedures and the technical expertise required.

Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) antigen is a lipopolysaccharide present in the mycobacterial cell wall that can be detected in the urine of people with tuberculous disease (Bjerrum 2019). This urine test offers potential advantages over sputum‐based testing due to ease of sample collection. The accuracy of urinary LAM detection is improved among people living with HIV with advanced immunosuppression (Bjerrum 2019;; Nicol 2014; Shah 2016a). One Cochrane Review found that in inpatient settings, the use of lateral flow (LF)‐LAM as part of a tuberculosis diagnostic testing strategy likely reduces mortality and probably results in a slight increase in tuberculosis treatment initiation in people living with HIV (Nathavitharana 2021). The WHO recommends that LF‐LAM (Alere Determine™ TB LAM Ag, Alere Inc, Waltham, MA, USA), the only product available at the time of this recommendation, should be used to assist in the diagnosis of tuberculosis disease in HIV‐positive adults, adolescents, and children. The full recommendations, which differ for inpatients and outpatients, are described in the WHO Consolidated guidelines for rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 3) 2021). However, the evidence for LF‐LAM in children is limited and is primarily extrapolated from adults. A new urinary, point‐of‐care LAM test, Fujifilm SILVAMP TB LAM (FujiLAM, co‐developed by FIND, Geneva, Switzerland, and Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), for diagnosis of tuberculosis, is currently under investigation and has the potential to increase sensitivity in children (Broger 2019).

Line probe assays are a category of molecular tests for drug‐resistant tuberculosis that offer speed of diagnosis (one or two days), standardized testing, and potential for high through‐put. Drawbacks are that line probe assays require skills and infrastructure only available in intermediate and central laboratories. Line probe assays for first‐line drugs (which include rifampicin) include GenoType MTBDRplus assay (MTBDRplus, Bruker‐Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany), and the Nipro NTM+MDRTB detection kit 2 (Nipro, Tokyo, Japan). These assays detect the presence of mutations associated with drug resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin. MTBDRplus is the most widely studied line probe assay. The WHO recommends that for people with a sputum smear‐positive specimen or a culture isolate of M tuberculosis complex, commercial molecular line probe assays may be used as the initial test instead of phenotypic drug susceptibility testing to detect resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid (conditional recommendation, moderate certainty in the evidence for the test's accuracy; WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 3) 2021).

The quest for novel and more efficient technologies for diagnosis of tuberculosis is a cornerstone of current efforts to reduce the burden of disease worldwide. Over the past decade, unprecedented activity has focused on the development of new tools for diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, largely supported by the engagement of global agencies. As a result, a strong pipeline of new tools for diagnosis of tuberculosis will complement the use of existing ones and will offer improved options. 'The Tuberculosis Diagnostics Pipeline Report: Advancing the Next Generation of Tools' describes tuberculosis tests in development (Branigan 2021).

Rationale

Timely and reliable diagnosis of tuberculosis in children remains challenging due to both difficulties in collecting sputum samples and the paucibacillary nature of the disease. Under‐diagnosis may lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and disease transmission in this key group.

Our previously published Cochrane Review assessed the accuracy of both Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert Ultra (Kay 2020). We limited the current review update to the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra for several reasons. Xpert Ultra has superseded Xpert MTB/RIF, and the manufacturer will be discontinuing Xpert MTB/RIF in most countries in 2023. Given the available evidence about Xpert MTB/RIF from our previous review, we therefore only updated Xpert Ultra as requested by the WHO. The Xpert MTB/RIF text and analyses are available in the last published version of the review (Kay 2020).

Regarding Xpert Ultra, in the original Cochrane Review, we identified few published studies: three studies on Xpert Ultra in sputum (697 participants) and no studies in gastric aspirate and stool specimens. In addition, we had limited data in children younger than 10 years of age, an area of considerable interest for the WHO.

In the current review update, we aimed to determine the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculosis meningitis, lymph node tuberculosis, and rifampicin resistance in children. Parts of the review update, particularly the analyses of gastric aspirate and stool specimens, were used to inform the 2022 WHO updated guidance on the management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 5) 2022; see Table 3).

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of Xpert Ultra for detecting: pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis, lymph node tuberculosis, and rifampicin resistance, in children with presumed tuberculosis.

Secondary objectives

To investigate potential sources of heterogeneity in accuracy estimates. For detection of tuberculosis, we considered age, comorbidity (HIV, severe pneumonia, and severe malnutrition), and specimen type as potential sources.

To summarize the frequency of Xpert Ultra trace results.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included cross‐sectional studies, cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from all settings. We included RCTs that evaluated use of the test for patient health outcomes but also reported sensitivity and specificity. Although we utilized RCTs for the purpose of determining the impact of the test versus a comparator (e.g. usual practice, another test) on health outcomes, the study design was interpreted as a cross‐sectional design for the purpose of determining diagnostic accuracy for the index tests in this review. We included only studies from which we could extract or derive data on the index test giving true positives, false positives, true negatives, or false negatives, as assessed against the reference standards specified below. We included abstracts with sufficient data. In addition, we included ongoing studies that helped us to address the review objectives (see Data collection and analysis). For each of the ongoing studies, we recorded the stage of the study at the time of data extraction for this review (e.g. recruitment completed, recruitment completed and data cleaned, or recruitment ongoing and number (%) of the target sample size recruited) in the Characteristics of included studies table. We excluded case‐control studies and case reports.

Participants

We included studies that evaluated the index tests for pulmonary or extrapulmonary tuberculosis in HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative children and young adolescents aged 0 to 14 years (collectively referred to as children), presumed to have tuberculosis. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they described the use of Xpert Ultra on routine respiratory specimens such as expectorated or induced sputum and gastric and nasopharyngeal specimens. Gastric specimens could be obtained via gastric aspiration, lavage, or washing, as described by study authors. In addition, we included studies evaluating stool specimens, because tuberculosis bacilli are present in swallowed sputum and are recoverable from stool samples using Xpert Ultra. We also included studies that assessed several different specimen types.

Index tests

The index test was Xpert Ultra.

Index test results are automatically generated, and the user is provided with a printable test result as follows.

MTB (M tuberculosis) DETECTED HIGH; RIF (rifampicin) Resistance DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED MEDIUM; RIF Resistance DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED LOW; RIF Resistance DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED VERY LOW; RIF Resistance DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED HIGH; RIF Resistance NOT DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED MEDIUM; RIF Resistance NOT DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED LOW; RIF Resistance NOT DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED VERY LOW; RIF Resistance NOT DETECTED.

MTB DETECTED HIGH; RIF Resistance INDETERMINATE.

MTB DETECTED MEDIUM; RIF Resistance INDETERMINATE.

MTB DETECTED LOW; RIF Resistance INDETERMINATE.

MTB DETECTED VERY LOW; RIF Resistance INDETERMINATE.

MTB Trace DETECTED; RIF Resistance INDETERMINATE.

INVALID (the presence or absence of MTB cannot be determined).

ERROR (the presence or absence of MTB cannot be determined).

NO RESULT (the presence or absence of MTB cannot be determined).

Xpert Ultra incorporates a semi‐quantitative classification for results: trace, very low, low, moderate, and high. Trace corresponds to the lowest bacterial burden for detection of M tuberculosis (Chakravorty 2017). Although no rifampicin resistance results are available for people with trace results, a trace‐positive result is sufficient to initiate tuberculosis therapy in children or people living with HIV, according to the WHO (WHO Consolidated Guidelines (Module 3) 2021). Hence, we considered a trace result to mean M tuberculosis DETECTED.

Target conditions

The target conditions were active pulmonary tuberculosis; two forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis and lymph node tuberculosis; and rifampicin resistance.

Reference standards

For detection of pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis, and lymph node tuberculosis, we included two reference standards (see below regarding stool samples).

Culture: tuberculosis was defined as a positive culture on solid or liquid medium from a respiratory sample.

Composite reference standard: tuberculosis was defined as a positive culture or a clinical decision, based on clinical features, to initiate treatment for tuberculosis (i.e. clinically diagnosed tuberculosis). Clinical features might include cough longer than two weeks, fever, or weight loss; pneumonia that did not improve with antibiotics; or a history of close contact with an adult who had tuberculosis.

For the composite reference standard, in the absence of information on tuberculosis treatment, we accepted a study‐specific definition (i.e. a standardized definition of tuberculosis defined by the primary study authors), if available. We also accepted the uniform research definition (Graham 2012; Graham 2015). In these situations, for the older definition (Graham 2012), we defined tuberculosis as 'confirmed, probable, and possible' and not tuberculosis as 'unlikely and not tuberculosis'. For the newer definition (Graham 2015), we defined tuberculosis as 'confirmed and unconfirmed' and not tuberculosis as 'unlikely'.

We included children with unconfirmed tuberculosis in the true‐negative population when evaluating results against a culture reference standard. In contrast, we included children who were not treated for tuberculosis, or who did not meet the study research definition for tuberculosis, in the true‐negative population when evaluating results against a composite reference standard.

Regarding stool specimens (used for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis), we defined the reference standard similar to MacLean 2019: (1) culture, or (2) Xpert Ultra performed on a routine respiratory specimen, such as sputum or gastric aspirate specimen. We did not include stool Xpert Ultra results in the definition of the reference standard. In addition, none of the included studies used stool culture to verify pulmonary tuberculosis. For these reasons, we thought bias due to incorporation of the index test was unlikely. Hence, tuberculosis was defined as a positive culture or a positive Xpert Ultra on a routine respiratory specimen.

Regarding stool specimens, we also included a composite reference standard as defined above.

Culture is generally considered the best reference standard for tuberculosis diagnosis. However, particularly in children with paucibacillary disease, tuberculosis is verified by culture in only 15% to 50% of cases, depending on disease severity, challenges of obtaining specimens, and resources (Graham 2015). Evaluation of multiple specimens, of the same or different types, may increase the yield of culture for confirming tuberculosis (Cruz 2012;Zar 2012). Therefore, we considered a higher‐quality reference standard to be one in which more than one specimen was used to confirm tuberculosis. We considered a lower‐quality reference standard to be one in which only one specimen was used for tuberculosis diagnosis. We reflected these considerations in the Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy – Revised (QUADAS‐2) reference standard domain.

For rifampicin resistance, the reference standards were phenotypic drug susceptibility testing and MTBDRplus. MTBDRplus is a molecular line probe assay designed to detect the presence of multiple mutations causing resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin.

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases up to 9 March 2021 using the search terms and strategy described in Appendix 1.

Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register.

MEDLINE (Ovid, from 1966).

Embase (Ovid, from 1974).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL (EBSCOHost), from 1982).

Science Citation Index – Expanded (from 1900), Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI‐S, from 1990), from the Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics).

Scopus (Elsevier, from 1970).

We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform), and the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) Registry (www.isrctn.com) for trials in progress, up to 9 March 2021.

Searching other resources

We contacted researchers and experts in the field to identify additional eligible studies. This included sharing the list of included and excluded studies with the WHO Guideline Development Group on the management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents prior to a preparatory webinar for input and feedback. We also checked the references of relevant reviews and studies to identify additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used Covidence to manage the selection of studies (Covidence). Two review authors (AWK and TN, or AWK and LFG) independently screened all titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. We then obtained the full‐text articles of potentially eligible studies, and two review authors (AWK and TN, or AWK and LFG) independently assessed whether they should be included based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by consulting a third review author (AMM or KRS), if necessary. We contacted primary study authors for clarification of methods and other information, as needed. We recorded and summarized reasons for excluding studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We illustrated the study selection process in a PRISMA diagram (Page 2021).

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction form and piloted it on two included studies (Appendix 2). We then finalized the form based on the pilot test. Two review authors (AWK and TN or AWK and LFG) independently extracted data using this data extraction form and discussed inconsistencies to achieve consensus. We consulted a third review author (AMM or KRS) to resolve discrepancies, as needed. We entered abstracted data into Google sheets on password‐protected computers. We secured the data set in a cloud storage workspace and we stored extracted data for future review updates. Selected details of data extraction are listed below.

Study details

Number of participants after screening for exclusion and inclusion criteria

Total number of children included in the analysis

Specimen collection methods

Unit of sample collection: one specimen, multiple specimens, unknown, or unclear

Target condition(s)? – pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis, lymph node tuberculosis, rifampicin resistance

For ongoing studies, we recorded the stage of the study at the time of data extraction for this review (e.g. recruitment completed, recruitment completed and data cleaned, or recruitment ongoing and number (%) of the target sample size recruited) in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Patient characteristics and setting

Description of study population

Age: median, mean, range

Sex

HIV status

Percentage and number of HIV‐positive or HIV‐negative participants, if both were included in the study

Type of respiratory specimen included: sputum, gastric aspirate or lavage, stool, nasopharyngeal aspirate

Type of non‐respiratory specimen included: cerebrospinal fluid, fine‐needle aspirate, lymph node biopsy, multiple types, other, unknown

Number of cultures performed per child to exclude tuberculosis

Data on culture performance: number of contaminated cultures with respect to total cultures performed

Clinical setting: outpatient, inpatient, or both

Description of radiographic findings

Information on tuberculosis burden in the country

We classified countries as being high‐burden or not high‐burden for tuberculosis, HIV‐associated tuberculosis, and MDR or rifampicin‐resistant tuberculosis based on the WHO classification for 2021 to 2025 (WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2021). A country may be classified as high‐burden for one, two, or all three of the high‐burden categories.

We contacted the authors of all included studies for data on specific age ranges and subpopulations and for clarification on study characteristics.

Index test

Pretreatment processing procedure for specimens used for Xpert Ultra

Specimen condition: fresh, frozen, or both

Numbers of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives by age group (all ages, under one year, one to four years, five to nine years, 10 to 14 years, and birth to 9 years; (see example tables in Appendix 3)

Uninterpretable results for tuberculosis detection (invalid, error, or no result)

Indeterminate results for detection of rifampicin resistance

Xpert Ultra trace results

Reference standards

Details of culture: solid or liquid

Composite reference standard

Rifampicin resistance: phenotypic drug susceptibility testing or MTBDRplus

For each target condition and specimen type, we considered one index test result per child. Hence, the primary unit of analysis was the child. If studies evaluated more than one specimen type, we extracted data for each specimen. Hence, a study may have contributed more than one 2 × 2 table (data set): one for each type of specimen evaluated.

Assessment of methodological quality

We assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the QUADAS‐2 instrument, which we adapted for this review (Whiting 2011). The QUADAS‐2 tool consists of four domains:

patient selection;

index test(s);

reference standard(s); and

flow and timing.

All domains are assessed for risk of bias, and the first three domains are assessed for concerns regarding applicability. We first developed guidance on how to appraise each signalling question within the domains and how to make the overall judgement for each domain. One review author piloted the tool with two of the included studies. We finalized the guidance based on experience gained from the pilot. Appendix 4 presents the QUADAS‐2 tool with signalling questions tailored to this review. Two review authors (AK and LFG or AK and TN) independently completed QUADAS‐2. We resolved disagreements through discussion or by arbitration with a third review author (KRS or AMM), when necessary. We presented results of the quality assessment in the text, in tables, and in graphs.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We performed descriptive analyses of the included studies and presented their key characteristics in the Characteristics of included studies table. We stratified all analyses by type of specimen and type of reference standard. We presented individual study estimates of sensitivity and specificity graphically in forest plots and in receiver operating characteristics (ROC) space using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020).

When data were sufficient, we performed meta‐analyses to estimate average sensitivities and specificities using a bivariate model (Chu 2006; Reitsma 2015). We used the bivariate model because the index test, Xpert Ultra, applies a common positivity criterion (Macaskill 2010). When we were unable to fit a bivariate model due to sparse data, few studies, or limited variability in specificity, we simplified the model to a univariate random‐effects or fixed‐effect logistic regression model to pool sensitivity and specificity separately, as appropriate given the observed data (Takwoingi 2015). We performed meta‐analyses using the meqrlogit command for models that included random effects and the blogit command for fixed‐effect meta‐analyses in Stata version 16 (Stata 16). Meta‐analysis using univariate fixed‐effect or random‐effects logistic regression models is not possible when all studies in a meta‐analysis report 100% specificity. For such analyses, we calculated summary specificity by dividing the total number of non‐cases by the total number of true negatives, and we computed the 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Wilson method (Newcombe 1998).

Approach to non‐determinate and trace index test results

Non‐determinate Xpert Ultra test results include 'Error', 'Invalid', and 'No Result', and may be due to an operator error, instrument, or cartridge issue. For each included study that reported the number of non‐determinate results for tuberculosis detection, we estimated the proportion of non‐determinate Xpert Ultra results. As recommended by the WHO, trace results were included in the primary analyses as Xpert Ultra‐positive results. For each included study that provided data on trace results, we calculated the percentage of test positives that were trace results (i.e. number of trace results/number of test positives).

Investigations of heterogeneity

We visually inspected forest and summary ROC (SROC) plots for heterogeneity. When data allowed, we evaluated sources of heterogeneity using subgroup analyses. We were unable to perform meta‐regression because of the number of studies available. For tuberculosis detection, we investigated key subgroups of children: aged under 1 year, aged 1 to 4 years, aged 5 to 9 years, aged 10 to 14 years, HIV‐positive, HIV‐negative, with severe pneumonia, and with severe malnutrition.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses excluding data from ongoing studies in the primary analyses.

Assessment of reporting bias

We did not formally assess reporting bias using funnel plots or regression tests because these have not been reported as helpful for diagnostic test accuracy studies (Macaskill 2010).

Assessment of certainty of the evidence

We assessed certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach for diagnostic studies (Balshem 2011; Schünemann 2008; Schünemann 2016). As recommended, we rated certainty of the evidence as high (not downgraded), moderate (downgraded one level), low (downgraded two levels), or very low (downgraded more than two levels) based on five domains: risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, and publication bias. For each outcome, certainty of the evidence started as high when high‐quality studies (cross‐sectional or cohort studies) enrolled participants with diagnostic uncertainty. If we found a reason for downgrading, we used our judgement to classify the reason as serious (downgraded one level) or very serious (downgraded two levels).

Three review authors (AWK, TN, and KRS) discussed judgements and applied GRADE (Schünemann 2020a; Schünemann 2020b).

Risk of bias

We used QUADAS‐2 to assess risk of bias.

Indirectness

We assessed indirectness in relation to the population (including disease spectrum), setting, interventions, and outcomes (accuracy measures). We also used prevalence (proportion) of the target condition in the included studies as a guide to whether there was indirectness in the population.

Inconsistency

GRADE recommends downgrading for unexplained inconsistency in sensitivity and specificity estimates. We carried out pre‐specified analyses to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity and downgraded when we could not explain inconsistency in accuracy estimates. We looked at the individual point estimates in the forest plots and judged whether they were more or less the same, as well as the CIs to see if they overlapped.

Imprecision

We considered the width of the 95% CI. In addition, we determined projected ranges for two categories of test results that have the most important consequences for patients – the number of false negatives and the number of false positives – and made judgements on imprecision from these calculations. Imprecision also depends on the number of participants included to determine sensitivity and specificity. We took note of the uncertainty around point estimates along with the number of participants providing those data. We acknowledge the judgement of imprecision is subjective.

Publication bias

We considered the comprehensiveness of the literature search and outreach to researchers in tuberculosis, the presence of only studies that produce precise estimates of high accuracy despite small sample size, and knowledge about studies that were conducted but not published.

The summary of findings tables include the following details:

The review question and its components, population, setting, index test, and reference standards.

Summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity with 95% CIs.

The number of included studies and participants contributing to the estimates of sensitivity and specificity.

Prevalences of the target condition with an explanation of why the prevalences have been chosen.

An assessment of the certainty of the evidence (GRADE).

Explanations for downgrading, as needed.

Results

Results of the search

We identified 2174 records through database searches conducted up to 29 April 2019. An updated search to 9 March 2021 identified 115 records. We found one additional record by contacting researchers at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND). After removing duplicates, we screened 51 records by title and abstract. We excluded 35 of these, leaving 16 reports, which we retrieved for full text review. We identified 14 unique studies (including one from a source outside of our database searches), integrating 11 new studies since publication of the Cochrane Review (Kay 2020). All studies were written in English. Figure 2 shows the flow of studies in the review. We recorded the excluded studies, including those listed in the previous Cochrane Review (Kay 2020), with reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

2.

Study flow diagram. aKay 2020. bStudies only evaluated Xpert MTB/RIF and other reasons: not a diagnostic study; study did not include children; case‐control study; abstract; index test not studied.

Description of included studies

We describe key characteristics in the Characteristics of included studies table and Table 4. All were cross‐sectional or cohort studies, with the exception of one, which had an unclear study design. The studies were conducted in both inpatient and outpatient settings; seven took place in tuberculosis high‐burden countries.

2. Key characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Reference standard | Study design | HIV status | Clinical setting | High tuberculosis burden | Type of specimens | Xpert Ultra non‐determinatea% (number/total) | Xpert Ultra traceb% (number) |

| Barcellini 2019 | Culture | Cross‐sectional | Negative | Outpatient | No | Sputum | None | None |

| Jaganath 2021 | Culture, composite |

Cohort | Both | Both | No | Sputum, gastric, nasopharyngeal | Not reported | Sputum: 12% (2); gastric: 67% (2); nasopharyngeal: 40% (2) |

| Kabir 2020 | Culturec, composite |

Cross‐sectional | Yes | Inpatient | Yes | Sputum, stool | < 1% (1/446) | Sputum: 39% (11); stool: 80% (48) |

| Liu 2021 | Culturec | Cohort | Negative | Both | Yes | Sputum, gastric, stool, nasopharyngeal | Not reported | Sputum: 0%; gastric: 30% (8); stool: 38.% (16); nasopharyngeal: 0% |

| NCT04121026 | Culture | Cohort | Positive | Both | Yes | Sputum, gastric, stool, nasopharyngeal | 4% (5/114) | Sputum: 0%; gastric: 25% (1); nasopharyngeal: 0%; stool: 0% |

| NCT04203628 | Culture | Cohort | Both | Both | Yes | Stool | 3% (2/76) | Stool: 40% (2) |

| NCT04240990 | Culture | Cohort | Both | Inpatient | Yes | Gastric, stool, nasopharyngeal | 1% (2/237) | Stool: 60% (3) |

| NCT04899076 | Culturec | Cohort | Both | Both | Yes | Stool | 10% (42/434) | Stool: 39% (12) |

| Nicol 2018 | Culture, composite |

Cohort | Both | Inpatient | Yes | Sputum | 11% (50/453) | Sputum: 26% (8) |

| Parigi 2021 | Culture, composite | Unclear | Not reported | Inpatient | No | Gastric | Not reported | NA |

| Sabi 2018 | Culture, composite |

Cohort | Both | Both | Yes | Sputum | 0% (0/215) | Sputum: 19% (3) |

| Ssengooba 2020 | Culture | Cohort | Both | Unclear | No | Sputum, gastric | Not reported | Sputum: 67% (4); gastric: 57% (13) |

| Sun 2020 | Culture, composite |

Cohort | Not reported | Unclear | Yes | Gastric | Not reported | Gastric: 26% (20) |

| Zar 2019 | Culture, composite |

Cohort | Both | Inpatient | Yes | Nasopharyngeal | Not reported | Nasopharyngeal: 45% (9) |

aNon‐determinate results are Error, Invalid, or No Result. bCalculated as percentage of total number of positive tests. cFor stool, Xpert on respiratory specimens was accepted as part of the reference standard.

For pulmonary tuberculosis, 108 data sets (20,407 participants) were available for analysis; for rifampicin resistance, three data sets (131 participants) were available.

We did not identify any studies that evaluated Xpert Ultra accuracy for tuberculous meningitis or lymph node tuberculosis.

Methodological quality of included studies

Pulmonary tuberculosis

Figure 3 and Appendix 5 show risk of bias and applicability concerns for 14 studies that evaluated Xpert Ultra for detection of pulmonary tuberculosis.

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study.

In the patient selection domain, we considered 13 studies (93%) at low risk of bias because they enrolled a consecutive or random sample of eligible participants and avoided inappropriate exclusions. We considered one study (7%) at unclear risk of bias because the manner of patient sampling was unclear (Parigi 2021). With respect to applicability, we considered 10 studies (71%) of low concern because participants in these studies were evaluated in primary care facilities, in local hospitals, or in both settings (Barcellini 2019; Jaganath 2021; Liu 2021; NCT04121026; NCT04203628; NCT04240990; NCT04899076; Nicol 2018; Sabi 2018; Ssengooba 2020). We considered three studies (21%) of high concern because participants were evaluated exclusively as inpatients in tertiary care centres (Kabir 2020; Parigi 2021; Zar 2019). We considered one study of unclear concern because we were unsure about the clinical setting (Sun 2020).

In the index test domain, we considered all studies at low risk of bias. With respect to applicability, we considered eight studies (73%) to of low concern (Barcellini 2019; Jaganath 2021; Nicol 2018; Parigi 2021; Sabi 2018; Ssengooba 2020; Sun 2020; Zar 2019). We considered all studies that evaluated stool specimens of unclear concern because of the absence of an established protocol for stool processing before Xpert Ultra testing.

In the reference standard domain, we considered 13 studies (93%) at low risk of bias and one study at unclear risk of bias because the ability of the reference standard to appropriately classify child tuberculosis was uncertain (Kabir 2020). With respect to applicability, we considered nine (64%) studies of low concern because speciation was performed, confirming M tuberculosis instead of other mycobacterial species (Barcellini 2019; Jaganath 2021; NCT04121026; NCT04203628; NCT04899076; Nicol 2018; Sabi 2018; Ssengooba 2020; Zar 2019, and five studies of unclear concern because we could not tell whether speciation was performed (Kabir 2020; Liu 2021; NCT04240990; Parigi 2021; Sun 2020).

In the flow and timing domain, we considered 13 studies (93%) at low risk of bias because all participants were included in the analysis. We considered one study at high risk of bias (Liu 2021) because most enrolled children were not included in the analysis.

Rifampicin resistance

In the patient selection domain, we judged two studies at low risk of bias (Liu 2021; Parigi 2021), and one study at unclear risk of bias because the manner of patient selection was not reported (Parigi 2021). Regarding applicability, in the patient selection domain we had low concern for one study (Liu 2021), and high concern for two studies because all patients were recruited from an inpatient setting (Parigi 2021; Zar 2019). In the index test and reference standard domains, we judged all studies at low risk of bias and of low concern regarding applicability. In the flow and timing domain, we judged one study at high risk of bias because not all participants were included in the analysis (Liu 2021).

Findings

I. Detection of pulmonary tuberculosis

Due to little observed variability in specificity and in the volume of analyses, we chose to present only forest plots, as such plots were more informative than corresponding SROC plots.

Xpert Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis

Xpert Ultra in sputum specimens

Culture reference standard