Abstract

Flavobacterium johnsoniae is a gram-negative bacterium that exhibits gliding motility. To determine the mechanism of flavobacterial gliding motility, we isolated 33 nongliding mutants by Tn4351 mutagenesis. Seventeen of these mutants exhibited filamentous cell morphology. The region of DNA surrounding the transposon insertion in the filamentous mutant CJ101-207 was cloned and sequenced. The transposon was inserted in a gene that was similar to Escherichia coli ftsX. Two of the remaining 16 filamentous mutants also carried insertions in ftsX. Introduction of the wild-type F. johnsoniae ftsX gene restored motility and normal cell morphology to each of the three ftsX mutants. CJ101-207 appears to be blocked at a late stage of cell division, since the filaments produced cross walls but cells failed to separate. In E. coli, FtsX is thought to function with FtsE in translocating proteins involved in potassium transport, and perhaps proteins involved in cell division, into the cytoplasmic membrane. Mutations in F. johnsoniae ftsX may prevent translocation of proteins involved in cell division and proteins involved in gliding motility into the cytoplasmic membrane, thus resulting in defects in both processes. Alternatively, the loss of gliding motility may be an indirect result of the defect in cell division. The inability to complete cell division may alter the cell architecture and disrupt gliding motility by preventing the synthesis, assembly, or functioning of the motility apparatus.

Gliding motility, the movement of cells over surfaces without the aid of flagella, is a common form of motility exhibited by bacteria belonging to different branches of the eubacterial phylogenetic tree (45). Numerous models have been proposed to explain gliding motility, but the mechanism responsible for cell movement is not known (8, 30, 45).

Recently, genetic techniques, including cosmid complementation and transposon mutagenesis, were developed to manipulate Flavobacterium johnsoniae (formerly Cytophaga johnsonae [5]) (25). These techniques have been used to identify two genes (gldA and gldB) that are required for gliding motility in F. johnsoniae (2, 23). GldA appears to be an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter protein. GldB exhibits weak, but potentially significant, similarity to proteins that function in carbohydrate or polysaccharide synthesis or metabolism. The exact function of either protein in gliding motility is not known.

In this paper, we report that transposon insertions in F. johnsoniae ftsX disrupt gliding motility and cell division. ftsX is one of a number of fts (filamentation temperature-sensitive) genes. fts mutants of Escherichia coli grow normally at 30°C but stop dividing and rapidly lose viability when shifted to the nonpermissive temperature of 41°C. E. coli ftsX is cotranscribed with ftsE, and it has been demonstrated that FtsX and FtsE interact (12). FtsE appears to be the ATP-binding component of an ABC transporter. FtsX is anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane and is thought to interact with FtsE at the cytoplasmic face of the membrane to form the ABC transporter complex. It is not known how FtsX and FtsE are involved in cell division. They may use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to perform the work needed to complete cell separation (14, 15). Alternatively, they may act indirectly on cell division. For example, they may translocate proteins involved in cell division into the cytoplasmic membrane. Several lines of evidence implicate FtsX and FtsE in such protein translocation (48). The results described in this paper indicate that F. johnsoniae ftsX is required for cell division and gliding motility and suggest that there may be a connection between these two processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and bacteriophage strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

F. johnsoniae UW101 (ATCC 17061, obtained from J. Pate) was the wild-type strain used in these studies, and all mutants were derived from this strain. The 39 nongliding mutants of F. johnsoniae that were obtained from J. Pate were previously described (10, 50). The strain designations for each of these nongliding mutants carry the prefix UW102. The strain designations are UW102-21, -25, -33, -34, -39, -40, -41, -48, -52, -53, -55, -56, -57, -61, -64, -66, -68, -69, -75, -77, -78, -80, -81, -85, -86, -92, -94, -95, -96, -98, -100, -101, -108, -140, -141, -300, -301, -302, and -348. The bacteriophage active against F. johnsoniae that were used in this study (φCj1, φCj7, φCj13, φCj23, φCj28, φCj29, φCj42, and φCj54) have been previously described (10, 32, 50). The E. coli strains used were DH5αMCR (Gibco BRL Life Technologies), HB101 (6), BW19851 (27), KW251 (Promega), and S17-1 (43). Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference of source |

|---|---|---|

| pBC SK+ | ColE1 ori; Cmr | Stratagene |

| pSPORT1 | ColE1 ori; Apr | Gibco BRL |

| pCR-Script Cam SK+ | ColE1 ori; Cmr | Stratagene |

| pCP11 | ColE1 ori; (pCP1 ori); Apr (Emr); E. coli-F. johnsoniae shuttle plasmid | 25 |

| pCP23 | ColE1 ori; (pCP1 ori); Apr (Tcr); E. coli-F. johnsoniae shuttle plasmid | 2 |

| pFD351 | ColE1 ori; Spr (Cfr Emr); E. coli-Bacteroides shuttle plasmid carrying cfxA | Obtained from C. J. Smith |

| pDH1 | 2.1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment containing cfxA in pBC SK+; Cmr | This study |

| pCP29 | ColE1 ori; (pCP1 ori); Apr (Cfr Emr); E. coli-F. johnsoniae shuttle plasmid | This study |

| R751::Tn4351Ω4 | IncP; Tpr Tcr (Emr); vector used for Tn4351 mutagenesis | 41 |

| pEP4351 | pir requiring R6K oriV; RP4 oriT; Cmr Tcr (Emr); vector used for Tn4351 mutagenesis | 11 |

| pMK102 | HindIII fragment from CJ101-207 containing 3.5 kb of Tn4351 and 0.35 kb of ftsX in pSPORT1; Apr Tcr | This study |

| pMK120 | 6.1-kb EcoRI fragment containing ftsX in pBC SK+; Cmr | This study |

| pMK121 | 6.1-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment of pMK120 cloned into pCP23; Apr (Tcr) | This study |

| pMK122 | 2.3-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment containing ftsX in pBC SK+; Cmr | This study |

| pMK123 | 2.3-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment of pMK122, containing ftsX, cloned into pCP23; Apr (Tcr) | This study |

| pMK127 | 1.7-kb fragment containing truncated ftsX, in pBC SK+; Cmr | This study |

| pMK128 | 1.7-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment of pMK127 in pCP23; Apr (Tcr) | This study |

| pMK132 | 2.5-kb PCR product containing ftsX, in pCR-Script Cam SK+; Cmr | This study |

| pMK133 | 2.5-kb NotI-SalI fragment of pMK132 in pSPORT1; Apr | This study |

| pMK134 | 2.5-kb KpnI-SphI fragment of pMK133 in pCP29; Apr (Cfr Emr) | This study |

| pMK135B | 1.6-kb PCR product, containing ftsX, in pCR-Script Cam SK+; Cmr | This study |

| pMK136 | 1.6-kb KpnI fragment of pMK135B in pCP29; Apr (Cfr Emr) | This study |

Unless indicated otherwise, antibiotic resistance phenotypes and origins of replication are those expressed in E. coli. Antibiotic resistance phenotypes and other features listed in parentheses are those expressed in F. johnsoniae but not in E. coli.

E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C, and F. johnsoniae strains were grown in Casitone yeast extract (CYE) medium at 30°C, as previously described (25). To observe colony spreading, F. johnsoniae was grown on PY2 agar at 25°C (2). Antibiotics were used at the given concentrations when needed: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), cefoxitin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), erythromycin (100 μg/ml), streptomycin (30 μg/ml), tetracycline (12 μg/ml for E. coli and 20 μg/ml for F. johnsoniae), and trimethoprim (200 μg/ml).

Construction of the E. coli-F. johnsoniae shuttle vector pCP29.

pFD351, which contains the cfxA gene from Tn4555 cloned into pFD288 (44), was obtained from C. J. Smith. cfxA confers resistance to cefoxitin on F. johnsoniae. pFD351 was digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and the 2.1-kb fragment containing cfxA was ligated with pBC SK+, which had been cut with the same enzymes, to generate pDH1. pDH1 was digested with BamHI and SalI, and the cfxA-containing fragment was ligated with pCP11 (an F. johnsoniae-E. coli shuttle vector) which had been cut with the same enzymes, to generate pCP29.

Tn4351 mutagenesis of F. johnsoniae.

Tn4351 was introduced into wild-type F. johnsoniae by conjugation from E. coli HB101 as described elsewhere (25), except that 5 mM CaCl2 was added to the CYE agar conjugation medium. In some experiments, pEP4351 was used instead of R751::Tn4351Ω4 as the vector for Tn4351 mutagenesis since this resulted in an increased efficiency of transposition. pEP4351 was transferred to F. johnsoniae from E. coli BW19851. Erythromycin-resistant colonies of Tn4351-induced mutants of F. johnsoniae appeared after 2 to 3 days of incubation at 25°C. Nonspreading mutants were examined for movement over glass and agar surfaces by phase-contrast microscopy, as described previously (2).

Cloning of Tn4351-disrupted ftsX.

Genomic DNA was isolated from the filamentous nongliding mutant CJ101-207 by standard procedures (39). The DNA was digested with HindIII and ligated into pSPORT1 which had been digested with the same enzyme. The recombinant plasmids were transferred by electroporation into E. coli DH5αMCR and plated on Luria-Bertani medium containing tetracycline to select for clones carrying the Tn4351 tetX gene. pMK102, which contained 3.5 kb of Tn4351 DNA and 0.35 kb of adjacent F. johnsoniae DNA, was isolated from one such colony.

Cloning of ftsX and surrounding DNA from wild-type F. johnsoniae.

F. johnsoniae DNA was partially digested with Sau3AI and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Fragments between 9 and 23 kb in size were cut from the gel, purified using GELase (Epicentre Technologies), and ligated into LambdaGEM-11 (Promega) that had been digested with BamHI and treated with alkaline phosphatase. The DNA was packaged into phage particles with MaxPlax packaging extract (Epicentre Technologies) and introduced into E. coli KW251. Lambda clones containing the regions of interest were detected by hybridization with radiolabeled DNA prepared using the 3.85-kb HindIII fragment of pMK102 and the Prime-a-Gene labeling kit (Promega).

DNA from one of the lambda clones was isolated, and a 6.1-kb EcoRI fragment, which contained ftsX and upstream genes, was subcloned into pBC SK+ to generate pMK120. For complementation of CJ101-207, the 6.1-kb fragment was isolated from pMK120 as a KpnI-XbaI fragment and cloned into the shuttle vector pCP23 to generate pMK121. In addition, a 2.3-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment from pMK120, spanning fjo12 and ftsX, was cloned into pBC SK+ to generate pMK122 and transferred as a KpnI-XbaI fragment into pCP23, to generate pMK123. To construct a clone carrying a truncated ftsX gene, the 0.6-kb EcoRV fragment was removed from pMK122 to generate pMK127 and the 1.7-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment of pMK127 was inserted into pCP23 to generate pMK128.

PCR amplification was used to obtain a clone containing just ftsX. The ftsX gene was amplified from pMK122 using the primers 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′ (T7 promoter primer [Promega]) and 5′-GCCAAAATCAGACAAAACGG-3′. The PCR product was cloned into the SrfI site of pCR-Script Cam SK+ to generate pMK135B. pMK135B was digested with KpnI, and the fragment containing ftsX was cloned into the E. coli-F. johnsoniae shuttle plasmid pCP29 to generate pMK136.

PCR amplification was also used to obtain a clone containing ftsX and the two genes immediately upstream and downstream of ftsX. The 2.5-kb region containing fjo12, ftsX, and fjo13 was amplified from genomic DNA using the primers 5′-TTCACTAAATTAATTTAGCCGC-3′ and 5′-AACTACAGCCGGAATAAAAGCG-3′ and cloned into the SrfI site of pCR-Script Cam SK+ to generate pMK132. To generate convenient restriction sites, the 2.5-kb fragment was transferred as a NotI-SalI fragment from pMK132 into pSPORT1, resulting in pMK133. Finally, the 2.5-kb KpnI-SphI fragment of pMK133 was introduced into pCP29, to generate pMK134.

Introduction of plasmids isolated from E. coli into filamentous mutants of F. johnsoniae by conjugation was extremely inefficient. Similarly, electroporation of plasmids isolated from E. coli into wild-type or mutant F. johnsoniae has not been successful, presumably due to restriction barriers. For this reason, the following multistep procedure was used to introduce plasmids into the filamentous mutants of F. johnsoniae. Plasmids were first introduced into E. coli S17-1 by electroporation. Next, they were transferred by conjugation into wild-type F. johnsoniae. Finally, plasmid DNA was isolated from wild-type F. johnsoniae and introduced by electroporation into the F. johnsoniae filamentous mutants. Transformants were plated on PY2 medium containing the appropriate antibiotics.

Nucleic acid sequencing and analysis.

Nucleic acid sequencing was performed by the dideoxynucleotide procedure using an automated (Applied Biosystems) sequencing system. Sequences were analyzed with the MacVector and AssemblyLign software (Oxford Molecular Group Inc.), and comparisons to database sequences were made using the BLAST (3) and FASTA (33) algorithms. Sequence alignments were performed with the ClustalW program (47).

PCR analysis to identify the Tn4351 insertion sites in ftsX.

A primer specific for Tn4351 (5′-GCTTATTATCCGCACCC-3′) was paired with each of the primers 5′-TTCACTAAATTAATTTAGCCGC-3′, 5′-CGCTTCGCATTACAAAAGGC-3′, and 5′-AACTACAGCCGGAATAAAAGCG-3′, to amplify the regions spanning the Tn4351 insertion sites in ftsX.

Negative staining of CJ101-207.

Cells were grown to mid- to late exponential phase in CYE broth containing erythromycin and deposited on carbon-coated Formvar films on 200-mesh copper grids. Cells were negatively stained with 0.8% phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.5) and examined using a Hitachi H600 transmission electron microscope operating at 75 kV.

Microscopic observations of cell movement, movement of latex spheres, and cell division.

Wild-type and mutant cells of F. johnsoniae were examined for movement over glass and agar surfaces by phase-contrast microscopy as previously described (2). Cultures were grown to late exponential phase (about 3 × 109 cells/ml for wild-type cells) in CYE broth. We examined the ability of cells to bind and propel 0.5-μm polystyrene latex spheres (Seradyn, Indianapolis, Ind.) as previously described (2).

The relationship between cell division and gliding motility was examined by monitoring movement of individual cells during growth and division on agar media. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (about 109 cells/ml) in CYE broth at 30°C and were spotted on a thin layer of agar medium on a microscope slide. Cells were covered with an oxygen-permeable membrane (Yellow Springs Instruments) and examined by time-lapse video microscopy at 30°C to observe cell division and gliding motility. Cells were examined on the following media (each of which contained 7 g of agar/liter): CYE (25), AOE (25), PY2 (2), and 2× PY2 (4 g of peptone and 1 g of yeast extract per liter [pH 7.3]).

Measurements of phage sensitivity.

Sensitivity to F. johnsoniae phage was determined by spotting 1, 10, and 50 μl of phage lysates (approximately 5 × 107 phage/ml) onto lawns of cells in CYE overlay agar (50). The plates were incubated for 24 h at 25°C to observe lysis.

Treatment of wild-type F. johnsoniae with antibiotics to induce filamentation.

F. johnsoniae was grown in CYE medium containing various antibiotics in an attempt to induce filamentation. The antibiotics tested were 6-aminopenicillanic acid, ampicillin, cefoxitin, cephalexin, nalidixic acid, and penicillin G. Antibiotics were used at final concentrations of 2.5, 5, 20, 100, and 250 μg/ml. Cell morphology, motility, and movement of latex spheres were examined using both mid-exponential- and stationary-phase cultures.

Genetic nomenclature.

Open reading frames (ORFs) that exhibited strong sequence similarity to genes of known function were named after the corresponding genes. ORFs of unknown function that did not exhibit strong similarity to previously described genes were given the provisional name fjo (F. johnsoniae ORF) followed by a number.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF169967.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Tn4351 mutagenesis of F. johnsoniae.

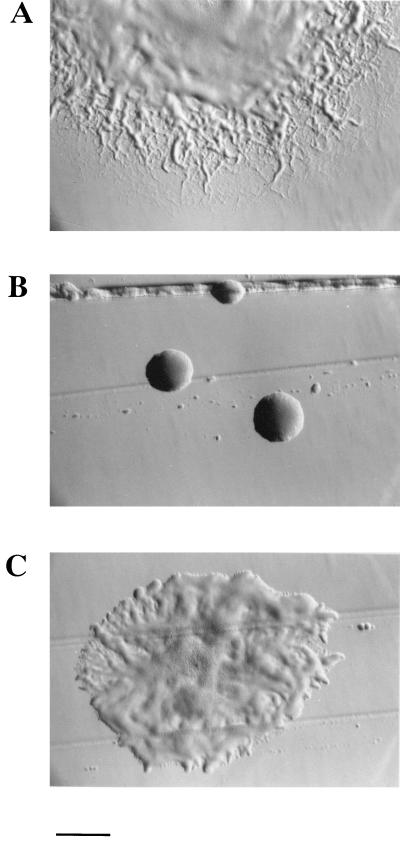

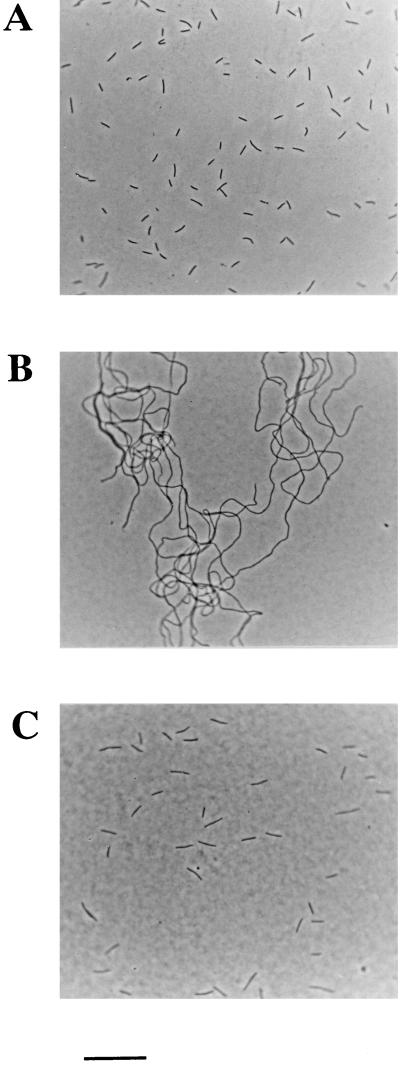

F. johnsoniae was mutagenized with Tn4351, and 123 erythromycin-resistant, nonspreading mutants were isolated. These were screened by phase-contrast microscopy to identify motility defects. Ninety of the mutants had defects in colony spreading but retained some ability to glide. Individual cells of these mutants exhibited gliding motility when examined by phase-contrast microscopy. The amount of movement ranged from vigorous gliding by nearly all cells in a population to weak movement exhibited by a small number of cells. The remaining 33 mutants exhibited no noticeable gliding motility. Seventeen of these mutants exhibited filamentous morphology. Individual cells reached lengths in excess of 300 μm. (Wild-type cells are approximately 5 μm in length.) One filamentous mutant, CJ101-207 (Fig. 1B and 2B), was chosen for further study.

FIG. 1.

Photomicrographs of F. johnsoniae colonies. Colonies were grown for 2 days on PY2 agar medium. Photomicrographs were taken with an Olympus OM-4T camera mounted on a Nikon Diaphot inverted phase-contrast microscope. (A) Wild-type F. johnsoniae. (B) Tn4351-induced, filamentous nongliding mutant CJ101-207. (C) CJ101-207 complemented with pMK136. Bar = 1 mm.

FIG. 2.

Morphology of F. johnsoniae cells. Photomicrographs were taken with an Olympus OM-4T camera mounted on an Olympus BH-2 phase-contrast microscope. (A) Wild-type F. johnsoniae. (B) Tn4351-induced filamentous, nongliding mutant CJ101-207. (C) CJ101-207 complemented with pMK136. Bar = 20 μm.

Subcloning and sequencing of ftsX.

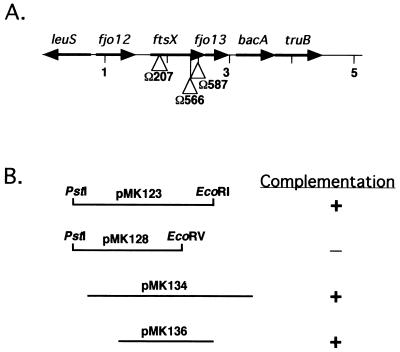

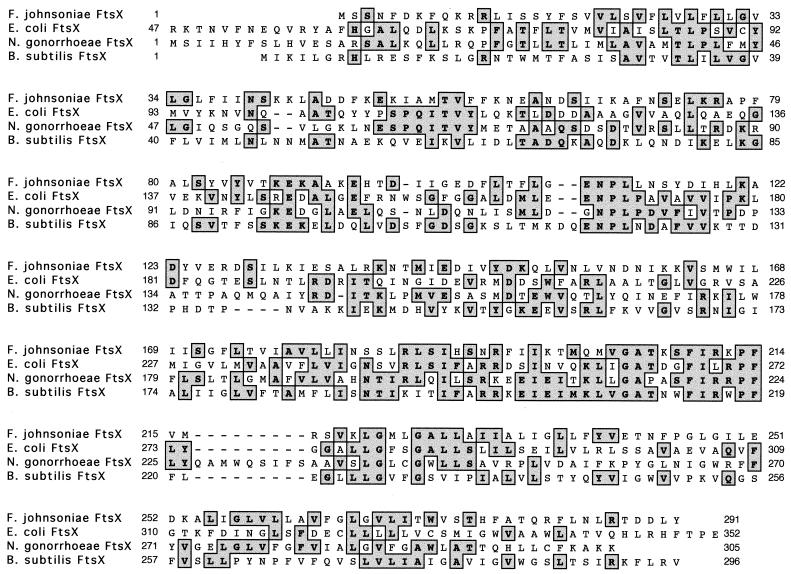

We cloned a 3.85-kb HindIII fragment that contained a portion of Tn4351 and adjacent F. johnsoniae DNA from CJ101-207. This fragment was used to probe a λ library of wild-type F. johnsoniae DNA, and several hybridizing clones were isolated. These clones were used to determine the nucleotide sequence of a 5.0-kb region that spans the site of the original Tn4351 insertion. Analysis of this region identified six ORFs (Fig. 3). The gene that was disrupted in CJ101-207 (ftsX) is predicted to code for a protein of 291 amino acids with a molecular mass of 33 kDa. Hydrophobicity analyses of FtsX predict the presence of four transmembrane regions, suggesting that FtsX may reside in the cytoplasmic membrane. F. johnsoniae FtsX exhibits weak similarity to FtsX proteins of other bacteria (Fig. 4). F. johnsoniae FtsX was most similar to E. coli FtsX (24% amino acid identity over 282 residues).

FIG. 3.

Map of the region of DNA surrounding ftsX. (A) Map of the 5-kb fragment that contains ftsX. The sites of the Tn4351 insertions in the mutants CJ101-207, CJ566, and CJ587 are indicated by triangles. (B) Complementation of Tn4351-induced, filamentous nongliding mutants CJ101-207, CJ566, and CJ587 by fragments cloned into pCP23 or pCP29.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence of F. johnsoniae FtsX with those of other proteins. Amino acid residues that are identical are shaded.

In E. coli, ftsX is part of an operon that contains two other genes, ftsY and ftsE (14). Point mutations in the E. coli ftsX gene result in a conditional (temperature-sensitive) defect in cell division (14). FtsX is located in the inner membrane of E. coli (14, 15). FtsE and FtsX appear to form a complex in the inner membrane of E. coli and may constitute an ABC transporter (12, 13, 15) that functions in protein translocation (12, 48). This complex may also have other roles associated more directly with cell division. We have not yet identified an ftsE homolog in F. johnsoniae. GldA is the putative ATP-binding component of an ABC transporter and is required for gliding motility (2). It is unlikely, however, that GldA and FtsX interact to form a transporter complex since mutations in gldA have no effect on cell division.

Complementation of strains carrying Tn4351 insertions in ftsX.

pMK121, which carries a 6.1-kb EcoRI fragment spanning the ftsX gene, was introduced into E. coli S17-1 by electroporation and transferred into the F. johnsoniae filamentous mutant CJ101-207 as described in Materials and Methods. After 3 days at 25°C, spreading colonies were observed. The cells in these complemented colonies were examined by phase-contrast microscopy and were found to exhibit wild-type cell morphology and gliding motility. Electroporation of pMK121 into the other 16 filamentous mutants identified two additional mutants (CJ566 and CJ587) that were also complemented by pMK121.

In order to determine the minimal region needed for complementation, we constructed pMK136 (Fig. 3B), which contains ftsX plus a short stretch of adjacent DNA (490 bp upstream of the predicted ftsX start codon and 134 bp downstream of the ftsX stop codon). Introduction of pMK136 into CJ101-207 restored colony spreading and cell motility (Fig. 1C). Colonies of CJ101-207 carrying pMK136 did not spread as well as those of wild-type cells, but individual cells moved as well as wild-type cells in wet mounts and on agar slides. Introduction of pMK136 into CJ101-207 also restored wild-type cell morphology (Fig. 2C). Similarly, pMK136 restored colony spreading, cell motility, and wild-type cell morphology to CJ566 and CJ587 (data not shown). Another plasmid, pMK123 (Fig. 3B), was constructed which carried a 2.3-kb fragment of DNA spanning fjo12 and ftsX. This clone also restored wild-type morphology, colony spreading, and motility to the three mutants. In contrast, the plasmid pMK128 (Fig. 3B), which carried a 1.7-kb fragment spanning fjo12 and the first 434 nucleotides of ftsX, did not restore normal cell morphology or gliding motility to CJ101-207, CJ566, or CJ587.

The fact that pMK136, which carries just ftsX, was sufficient to complement the filamentous mutants suggests that fjo12 and ftsX are not part of an operon. We do not know whether ftsX and fjo13 are cotranscribed. We have previously demonstrated that Tn4351 has promoters that read out of each end (23), so transposon mutations in ftsX may not be polar on downstream genes. We cloned a region of DNA spanning fjo12, ftsX, and fjo13 (pMK134 [Fig. 3B]) in order to determine if any additional filamentous mutants could be complemented by the genes flanking ftsX. pMK134 complemented the filamentous mutants CJ101-207, CJ566, and CJ587, as expected, but did not complement any of the other 14 Tn4351-induced, filamentous nongliding mutants.

Identification of the Tn4351 insertion sites in ftsX.

The sites of insertion of Tn4351 in CJ101-207, CJ566, and CJ587 were determined by cloning or amplifying the disrupted genes and determining the nucleotide sequence of the junction between the transposon and chromosome. Each mutant contained a single Tn4351 insertion in ftsX (Fig. 3). The sites of insertion of Tn4351 within ftsX were different for each of the three mutants.

Analysis of the region of DNA surrounding ftsX.

The ORFs near ftsX were examined to determine their possible functions. At the left end of the sequenced region in Fig. 3, and in the opposite orientation from all of the other genes analyzed, is an ORF, which we refer to as leuS. We do not have the complete sequence of leuS, but analysis of the predicted product of the first 468 bp reveals 57% identity over 156 amino acids to the leucyl-tRNA synthetase, LeuS, of Bacillus subtilis. fjo12, which lies between leuS and ftsX, exhibits 40% amino acid identity over 139 residues to a predicted protein of unknown function from Chlorobium tepidum (preliminary sequence data for C. tepidum was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org). fjo12 is separated by 241 bp from ftsX. Two inverted repeat sequences are present within this region. The larger of the inverted repeats starts 13 nucleotides after the fjo12 stop codon (5′-TTTAACCGCAAAGTACGCAAGGTTT-3′) and ends 135 nucleotides after the fjo12 stop codon (5′-AAACCTTGCGTACTTTGCGGTTAAA-3′). The smaller inverted repeat lies between the sequences mentioned above. It starts 44 nucleotides after the fjo12 stop codon (5′-AGTTCGCAAAGCTTT-3′) and ends 81 nucleotides after the fjo12 stop codon (5′-AAAGCTTTGCGAACT-3′). The function of these inverted repeats is not known, but they may have roles in transcription termination or RNA stabilization for fjo12. The transcriptional start site for ftsX is also likely to reside in the region between fjo12 and ftsX. The region between the inverted repeats described above and the start codon of ftsX is AT rich (82% AT over 106 nucleotides) as is often observed in promoter regions of other bacteria (38). Immediately downstream of the ftsX stop codon is the direct repeat sequence TTTTAGATTGCAGATTTTAGATTGCAGATTTTAGATT (repeated sequence underlined). The function of this sequence is not known. At 83 bp downstream of the ftsX stop codon is the predicted start codon of fjo13. fjo13 is a small ORF (256 bp), and its predicted protein product exhibits no significant sequence similarity to proteins in the databases. Downstream of fjo13 is an ORF, designated bacA. The predicted protein product of F. johnsoniae bacA is similar to E. coli BacA (44% identical over 259 amino acids) and to the putative BacA proteins of other bacteria, such as Aquifex aeolicus (47% identical over 246 amino acids). E. coli BacA is an undecaprenol kinase which confers resistance to bacitracin (9). The stop codon of F. johnsoniae bacA overlaps the predicted start codon of the next ORF, truB. These ORFs are likely to be cotranscribed as part of an operon. The predicted protein product of truB exhibits 37% identity over 212 amino acids with Mycobacterium tuberculosis TruB (20) and 34% identity over 219 amino acids with E. coli TruB (40). E. coli TruB is a tRNA pseudouridine synthase (29). We have no evidence that the genes described above, which flank F. johnsoniae ftsX, play any role in cell division or gliding motility.

Attempted complementation of nongliding, nonfilamentous mutants with pMK134.

There are several possible explanations for the finding that Tn4351 insertions in ftsX disrupt both gliding motility and cell division. (i) FtsX may be directly involved in both gliding motility and cell division. (ii) FtsX may be indirectly involved in both processes. For example, FtsX may be needed for translocation of proteins involved in these processes into or through the cytoplasmic membrane. (iii) Mutations in ftsX may cause a primary defect in cell division, and the altered architecture of the cell may prevent the synthesis, assembly, or functioning of the motility apparatus. Other explanations are also possible.

If FtsX is directly involved in gliding motility and cell division, we might predict that point mutations in ftsX would be found that would prevent gliding motility while allowing normal cell division. In order to provide a partial test of this hypothesis, we attempted to complement nongliding mutants with normal cell morphology by introducing wild-type ftsX on the plasmid pMK134. The nongliding mutants were obtained from J. Pate and were previously described (10, 50). We have 50 mutants in this collection that are completely lacking in gliding motility. Some of the mutants were spontaneous, and others were isolated following chemical mutagenesis. Four of the mutants have mutations in gldA (2), four have mutations in gldB (23), and three have mutations in gldD (M. J. McBride and D. W. Hunnicutt, unpublished data). Since the mutations responsible for lack of motility have already been characterized for these 11 mutants, they were not considered further in this study and we focused on the remaining 39 mutants. pMK134 did not complement the motility defects of any of these 39 mutants. While this does not prove that FtsX is not directly involved in gliding motility, it provides some support for an indirect role.

Phage resistance of ftsX mutants.

Many nongliding mutants of F. johnsoniae are resistant to infection by a number of F. johnsoniae bacteriophage (49). These phage may be able to infect only cells which have an actively moving surface (10). The moving components of the cell surface may be needed directly for adsorption of phage, or for uptake of phage nucleic acid into the cell. Alternatively, movement of cell surface molecules may be needed to expose phage adsorption sites that lie beneath. We tested the sensitivity of F. johnsoniae strains UW101, CJ101-207, and CJ636 (CJ101-207 carrying pMK123) to the F. johnsoniae bacteriophage φCj1, φCj7, φCj13, φCj23, φCj28, φCj29, φCj42, and φCj54. F. johnsoniae UW101 was readily lysed by these phage, whereas the filamentous, nongliding mutant CJ101-207 was resistant to infection by each of them. Introduction of pMK123 into CJ101-207 restored sensitivity to each of these phage in addition to restoring gliding motility and normal cell morphology. These results are similar to those previously reported for cells with mutations in the gliding motility genes gldA and gldB (2, 23).

Movement of latex spheres by ftsX mutants.

Wild-type cells of F. johnsoniae in liquid suspension bind latex spheres on their surfaces and propel these along the length of the cells (24, 31). The spheres appear to move along multiple tracks. The direction of movement of a sphere may change rapidly, and two spheres near each other on the same cell may move in the same direction or in different directions. Movement of spheres occurs at approximately the same speed as movement of cells over surfaces.

We examined the ability of cells of the F. johnsoniae strains UW101, CJ101-207, and CJ636 (CJ101-207 carrying pMK123) to bind and propel latex spheres. Wild-type cells bound and propelled the spheres. Cells of the ftsX mutant CJ101-207 rarely bound the spheres and were never observed to propel them. Cells of CJ636, carrying pMK123, bound and propelled the spheres as well as wild-type cells. These results are similar to those previously reported for gldA and gldB mutants of F. johnsoniae (2, 23).

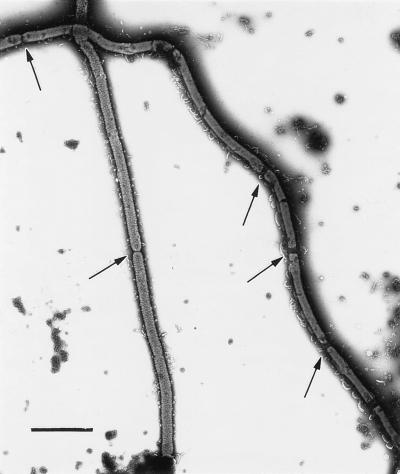

Electron microscopic analysis of the ftsX mutant CJ101-207.

Electron microscopic analyses were performed to determine the stage at which cell division was blocked in the ftsX mutant CJ101-207. Examination of cells that had been negatively stained with 0.8% phosphotungstic acid showed the presence of multiple septa in the filamentous cells (Fig. 5). This suggests that disruption of ftsX in F. johnsoniae blocks cell division or cell separation at a late step.

FIG. 5.

Electron micrograph of CJ101-207. Cells were stained with 0.8% phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.5). Arrows indicate sites of septation. Bar = 2 μm.

Addition of NaCl or KCl did not rescue the ftsX mutant CJ101-207.

It has been suggested that the FtsE-FtsX complex may have a direct or indirect role in salt transport in E. coli (12). ftsE null mutations, which are presumably polar on ftsX, result in extreme filamentation and eventually in cell death when E. coli cells are cultured on media containing low levels of salt. Addition of NaCl, or other salts, to the growth medium eliminates the lethality of the ftsE null mutation and also results in the production of shorter filaments (12). Apparently, the cell division and growth defects of E. coli ftsEX mutants are partially rescued by the addition of salt to the growth medium. Similarly, Ukai et al. have found a dramatic effect of KCl addition on some E. coli ftsE mutants (48). These mutants are nonviable at 41°C on medium containing 10 mM KCl. Addition of 200 mM KCl to the growth medium allows growth to occur. Cells grow to form extremely long filaments under these conditions, resembling those produced by F. johnsoniae ftsX mutants. Some of these salt effects may be explained by the finding that mutations in E. coli ftsE disrupt translocation of three K+ transporters into the cytoplasmic membrane (48).

To determine the effect of NaCl and KCl on cell morphology and motility of wild-type F. johnsoniae and of the filamentous nongliding mutant CJ101-207, cultures of mid-exponential-phase and stationary-phase cells grown in CYE with different concentrations of these salts (0 to 340 mM) were examined by phase-contrast microscopy. The highest concentration tested that allowed growth was 260 mM NaCl or KCl. Addition of NaCl or KCl to 171 mM had no obvious effect on growth, morphology, or motility of F. johnsoniae cells. Wild-type cells of F. johnsoniae maintained normal cell morphology and exhibited normal gliding motility when grown in the presence of up to 171 mM NaCl or KCl. Cells of the mutant CJ101-207 remained filamentous and nongliding whether they were grown in unsupplemented medium or in medium containing up to 171 mM NaCl or KCl. Addition of 260 mM NaCl or KCl partially inhibited growth of F. johnsoniae cells but had no dramatic effect on cell morphology or motility. Wild-type cells maintained normal cell morphology and exhibited gliding motility, whereas cells of the mutant CJ101-207 remained filamentous and nongliding.

Treatment with cephalexin causes cell filamentation without disrupting gliding motility.

It is possible that ftsX mutants fail to glide simply as a consequence of cell filamentation. We attempted to artificially convert wild-type cells into long filaments to determine the effect on motility. Exposure of bacterial cells to sublethal doses of certain antibiotics can result in the formation of filamentous cells (37). We tested several antibiotics to determine their effects on F. johnsoniae cell morphology and motility. Ampicillin, cefoxitin, nalidixic acid, and cephalexin each caused some degree of filamentation. Cephalexin (5 μg/ml) had the most dramatic effect on cell morphology. Individual cells reached lengths of up to 140 μm. (Untreated wild-type F. johnsoniae cells were 5 to 10 μm in length.) The cephalexin-induced filamentous cells exhibited gliding motility and were able to move latex spheres over their surfaces. Since these filamentous cells were able to glide, the lack of gliding motility in the ftsX mutants is probably not merely the result of an increase in cell length. This is not surprising, since many gliding bacteria naturally produce long filaments which are actively motile. Individual cells of Flexibacter FS-1 (a distant relative of F. johnsoniae within the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides group) reach lengths of 400 μm and exhibit active gliding motility (42). The results mentioned above indicate that, under some circumstances, production of filamentous F. johnsoniae cells is compatible with gliding motility. It is possible, however, that the inability of ftsX mutants to glide is a direct result of the block in cell division. Treatment of cells with cephalexin, and disruption of ftsX by Tn4351 insertion, may block cell division at different stages and may therefore have different effects on gliding motility. Cephalexin inactivates FtsI (21, 46), which is thought to act at an early to intermediate stage of cell division (4, 7). In contrast, ftsX mutants of F. johnsoniae appear to be blocked at a late stage of cell division, since completed septa are evident in the filaments (Fig. 5).

Video-microscopic analysis of cell division and motility.

The fact that ftsX mutants are defective in both cell division and gliding motility suggests that there may be a connection between the two processes. We examined wild-type cells of F. johnsoniae growing on CYE agar, AOE agar, PY2 agar, and 2× PY2 agar by time-lapse video microscopy in order to determine if gliding motility was affected by cell growth and division. We repeatedly observed (more than 100 examples) that dividing cells of wild-type F. johnsoniae stopped gliding for approximately 1 to 5 min just prior to cell separation. Once the cells had separated, they quickly resumed their normal rate of gliding. Similar observations have been made for several genera of gliding myxobacteria (26, 28, 34–36). The reason for the cessation of gliding during cell division is not known. One possibility is that the architecture of the cell during some stage of the division process is incompatible with gliding motility. Cell division requires major reconstruction of the cell envelope. Components of the gliding motility machinery are likely to be embedded in this envelope, so it would not be surprising that cell division would affect gliding. This could explain the nongliding phenotype of ftsX mutants. Transposon insertions in ftsX appear to block cell division at a late step of cell division. It is possible that the filamentous nongliding cells of the ftsX mutants are locked in a state of cell division that is incompatible with gliding motility. Alternatively, the gliding motility and cell division machineries may share some components that are critical to each process. There may be a stage of cell division at which these components are not available for gliding motility, so cell movement may temporarily cease. Other explanations, such as cell cycle expression of motility genes, are also possible.

Why are so many Tn4351-induced nongliding mutants filamentous?

In this paper, we describe 33 Tn4351-induced nongliding mutants of F. johnsoniae. Seventeen of these exhibited defects in cell division resulting in filamentous cell morphology. Three of these 17 mutants had insertions in ftsX. Other investigators have isolated hundreds of nongliding mutants of F. johnsoniae but have only rarely reported the isolation of filamentous nongliding mutants (10, 19, 50). Chang et al. isolated 51 nongliding mutants and reported that two of these mutants exhibited filamentous morphology (10). These two mutants were conditional (temperature sensitive). Cells were filamentous and nongliding at 34°C but displayed normal morphology and gliding motility when grown at 25°C. We do not know why filamentous mutants were so rare among the nongliding mutants isolated by these investigators or why all of their filamentous mutants were temperature sensitive. The mutants isolated by Chang et al. were spontaneous mutants or were isolated following chemical mutagenesis. Of the 51 nongliding mutants isolated by Chang et al., 42 were obtained by selection for phage resistance. None of these 42 mutants were filamentous. Tn4351 mutagenesis may favor the isolation of filamentous mutants, but the reason for this is not clear.

What is the role of F. johnsoniae FtsX in gliding motility?

Mutations in E. coli ftsX result in a conditional (temperature-sensitive) defect in cell division (14). In F. johnsoniae, transposon insertions in ftsX result in a cell division defect that is not dependent on growth temperature. In addition to their filamentous morphology, these mutants lack the ability to glide. The fact that so many Tn4351-induced nongliding mutants are also filamentous suggests that there may be a connection between gliding motility and cell division. One possibility, mentioned above, is that the cell division apparatus and the gliding motility apparatus share some components. FtsX could be one of those components. The exact role of E. coli FtsX in cell division is not known, but it is thought to function in protein translocation (48). F. johnsoniae FtsX may function as part of a translocation apparatus that inserts proteins involved in cell division, and proteins involved in gliding motility, into the cytoplasmic membrane. Mutations in ftsX would thus affect both processes. Alternatively, the inability to complete cell division may alter the cell architecture and indirectly disrupt the assembly or functioning of the gliding motility apparatus.

A number of models have been proposed to explain gliding motility of F. johnsoniae and related bacteria. F. johnsoniae gliding motility is thought to be powered by proton motive force (31). It is also known that exocellular or cell surface polysaccharides are important for gliding motility of F. johnsoniae (16, 18, 30). These may play a passive role in mediating productive contact of cells with the substratum. Sulfonolipids, which are localized in the outer membrane, have also been implicated in F. johnsoniae gliding motility (1, 17). One model of F. johnsoniae motility involves the movement of molecules in or on the outer membrane along tracks that may be fixed to the peptidoglycan (24). Additional components in the periplasm and cell membrane are postulated to harvest the proton motive force and perform the work necessary to move these molecules. The outer membrane molecules may be proteins or glycoproteins. It has also been suggested that extrusion of polysaccharide could propel cells (22). A number of other models to explain gliding motility of F. johnsoniae, or of other bacteria, have also been proposed (8, 30, 45, 51).

Disruption of gliding motility by mutations in ftsX is compatible with most models of gliding motility. Each model has one or more proteins associated with the cell envelope as components of the motility machinery. If FtsX is required for insertion of membrane proteins involved in gliding motility, mutations in ftsX would be expected to disrupt gliding motility. Alternatively, alterations to the cell envelope architecture, caused by a defect in cell division, could indirectly disrupt the gliding motility machinery. The observation that wild-type cells appear to cease gliding movement briefly during cell division may have implications regarding the mechanism of cell movement. It is obvious how a major restructuring of the cell envelope during cell division could disrupt continuous tracks or fibers that function in gliding motility and temporarily stop gliding movement. It is less clear why a process like polysaccharide export, which has also been proposed as a mechanism for cell movement, would be affected by cell division.

The exact function(s) of FtsX in cell division and gliding motility of F. johnsoniae remains to be determined. Further analysis of FtsX, and of the proteins that interact with FtsX, should help to elucidate its roles in these processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-9418308 and MCB-9727825) and by a Shaw Scientist Award to M.J.M. from The Milwaukee Foundation. Preliminary sequence data for C. tepidum was obtained by The Institute for Genomic Research (http://www.tigr.org) with support from the U.S. Department of Energy.

Some of the Tn4351-induced mutants were isolated by S. Agarwal, D. Hunnicutt, S. McDaniel, H. Hyung, and M. Jetzer. D. Hunnicutt constructed pCP29. DNA sequencing was performed by the Automated DNA Sequencing Facility of the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee Department of Biological Sciences. We thank H. Owen for assistance with the electron microscopy, W. Shi for the suggestion to use cephalexin to induce cell filamentation, and D. Saffarini for careful reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbanat D R, Leadbetter E R, Godchaux III W, Escher A. Sulphonolipids are molecular determinants of gliding motility. Nature. 1986;324:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal S, Hunnicutt D W, McBride M J. Cloning and characterization of the Flavobacterium johnsoniae (Cytophaga johnsonae) gliding motility gene, gldA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12139–12144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begg K J, Donachie W D. Cell shape and division in Escherichia coli: experiments with shape and division mutants. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:615–622. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.615-622.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernardet J-F, Segers P, Vancanneyt M, Berthe F, Kersters K, Vandamme P. Cutting a gordian knot: emended classification and description of the genus Flavobacterium, and proposal of Flavobacterium hydatis nov. (basonym, Cytophaga aquatilis Strohl and Tait 1978) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolivar F, Backman K. Plasmids of E. coli as cloning vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:245–267. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botta G A, Park J T. Evidence for involvement of penicillin-binding protein 3 in murein synthesis during septation but not during cell elongation. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:333–340. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.333-340.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchard R P. Gliding motility of prokaryotes: ultrastructure, physiology, and genetics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1981;35:497–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cain B D, Norton P J, Eubanks W, Nick H S, Allen C M. Amplification of the bacA gene confers bacitracin resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3784–3789. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3784-3789.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang L Y E, Pate J L, Betzig R J. Isolation and characterization of nonspreading mutants of the gliding bacterium Cytophaga johnsonae. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:26–35. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.26-35.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper A J, Kalinowski A P, Shoemaker N B, Salyers A A. Construction and characterization of a Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron recA mutant: transfer of Bacteroides integrated conjugative elements is RecA independent. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6221–6227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6221-6227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Leeuw E, Graham B, Phillips G J, ten Hagen-Johnman C M, Oudega B, Luirink J. Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli FtsE and FtsX. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:983–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs T W, Gill D R, Salmond G P C. Localised mutagenesis of the ftsYEX operon: conditionally lethal missense substitutions in the FtsE cell division protein of Escherichia coli are similar to those found in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein (CFTR) of human patients. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00272353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill D R, Hatfull G F, Salmond G P C. A new cell division operon in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:134–145. doi: 10.1007/BF02428043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill D R, Salmond G P C. The Escherichia coli cell division proteins FtsY, FtsE and FtsX are inner membrane-associated. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:504–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00327204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godchaux W, III, Gorski L, Leadbetter E R. Outer membrane polysaccharide deficiency in two nongliding mutants of Cytophaga johnsonae. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1250–1255. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1250-1255.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godchaux W, III, Leadbetter E R. Sulfonolipids are localized in the outer membrane of the gliding bacterium Cytophaga johnsonae. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godchaux W, III, Lynes M A, Leadbetter E R. Defects in gliding motility in mutants of Cytophaga johnsonae lacking a high-molecular-weight cell surface polysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7607–7614. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7607-7614.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorski L, Godchaux III W, Leadbetter E R, Wagner R R. Diversity in surface features of Cytophaga johnsonae motility mutants. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1767–1772. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu X, Yu M, Ivanetich K M, Santi D V. Molecular recognition of tRNA by tRNA pseudouridine 55 synthase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:339–343. doi: 10.1021/bi971590p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedge P J, Spratt B G. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics by re-modeling the active site of an E. coli penicillin-binding protein. Nature. 1985;318:478–480. doi: 10.1038/318478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoiczyk E, Baumeister W. The junctional pore complex, a prokaryotic secretion organelle, is the molecular motor underlying gliding motility in cyanobacteria. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunnicutt D W, McBride M J. Cloning and characterization of the Flavobacterium johnsoniae gliding-motility genes gldB and gldC. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:911–918. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.911-918.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapidus I R, Berg H C. Gliding motility of Cytophaga sp. strain U67. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:384–398. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.384-398.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McBride M J, Kempf M J. Development of techniques for the genetic manipulation of the gliding bacterium Cytophaga johnsonae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:583–590. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.583-590.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCleary W R, McBride M J, Zusman D R. Developmental sensory transduction in Myxococcus xanthus involves methylation and demethylation of FrzCD. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4877–4887. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4877-4887.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalf W W, Jiang W, Daniels L L, Kim S-K, Haldimann A, Wanner B L. Conditionally replicative and conjugative plasmids carrying lacZα for cloning, mutagenesis, and allele replacement in bacteria. Plasmid. 1996;35:1–13. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer-Pietschmann K. Lebendbeobachtungen an Myxococcus rubescens. Arch Mikrobiol. 1951;16:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurse K, Wrzesinski J, Bakin A, Lane B G, Ofengand J. Purification, cloning, and properties of the tRNA psi 55 synthase from Escherichia coli. RNA. 1995;1:102–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pate J L. Gliding motility. Can J Microbiol. 1988;34:459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pate J L, Chang L-Y E. Evidence that gliding motility in prokaryotic cells is driven by rotary assemblies in the cell envelopes. Curr Microbiol. 1979;2:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pate J L, Petzold S J, Chang L-Y E. Phages for the gliding bacterium Cytophaga johnsonae that infect only motile cells. Curr Microbiol. 1979;2:257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson W R. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:63–98. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichenbach H. Chondromyces apiculatus (Myxobacteriales)-Schwarmentwiklung und morphogenese. Publ Wiss Filmen Gottingen Sekt Biol. 1974;7:245–263. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichenbach H. Myxococcus spp. (Myxobacteriales). Schwarmentwicklung und bildung von protocysten. Publ Wiss Filmen Gottingen. 1966;1A:557–578. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichenbach H. Untersuchungen an Archangium violaceum. Arch Mikrobiol. 1965;52:376–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolinson G N. Effect of β-lactam antibiotics on bacterial cell growth rate. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;120:317–323. doi: 10.1099/00221287-120-2-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross W, Gosink K K, Salomon J, Igarashi K, Zou C, Ishahama A, Severinov K, Gourse R L. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science. 1993;262:1407–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.8248780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sands J F, Regnier P, Cummings H S, Grunberg-Manago M, Hershey J W. The existence of two genes between infB and rpsO in the Escherichia coli genome: DNA sequencing and S1 nuclease mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10803–10816. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoemaker N B, Getty C, Gardner J F, Salyers A A. Tn4351 transposes in Bacteroides spp. and mediates the integration of plasmid R751 into the Bacteroides chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:929–936. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.929-936.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon G D, White D. Growth and morphological characteristics of a species of Flexibacter. Arch Mikrobiol. 1971;78:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00409084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;2:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith C J, Parker A C. Identification of a circular intermediate in the transfer and transposition of Tn4555, a mobilization transposon from Bacteroides spp. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2682–2691. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2682-2691.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spormann A M. Gliding motility in bacteria: insights from studies of Myxococcus xanthus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:621–641. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.621-641.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spratt B G. Properties of the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem. 1977;72:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ukai H, Matsuzawa H, Ito K, Yamada M, Nishimura A. ftsE(Ts) affects translocation of K+-pump proteins into the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3663–3670. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3663-3670.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolkin R H, Pate J L. Phage adsorption and cell adherence are motility-dependent characteristics of the gliding bacterium Cytophaga johnsonae. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:355–367. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolkin R H, Pate J L. Selection for nonadherent or nonhydrophobic mutants co-selects for nonspreading mutants of Cytophaga johnsonae and other gliding bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:737–750. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Youderian P. Bacterial motility: secretory secrets of gliding bacteria. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R408–R411. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]