Abstract

Background

Menstrual irregularity is defined as any differences in the frequency, irregularity of onset, duration of flow, or volume of blood from the regular menstrual cycle. It is an important medical issue that many medical students suffer from. The study aimed to determine the menstrual cycle abnormalities women experienced during exams and to investigate the most common types of irregularities among female medical students at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among female medical students between September and October 2021 at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. For this study, the estimated sample size (n = 450) was derived from the online Raosoft sample size calculator. Thus, 450 female medical students from second to sixth year were selected through stratified random sampling. A validated online questionnaire collected data about demographics, menstrual irregularities during exams, type of irregularities, menstrual history, family history of menstrual irregularities, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, medical and family consultations, and absenteeism. The chi-squared test (χ2) was used to analyze the associations between variables.

Results

A total of 48.2% of participants had menstrual irregularities during exams. The most common irregularity was dysmenorrhea (70.9%), followed by a lengthened cycle (45.6%), and heavy bleeding (41.9%). A total of 93% of medical students suffered from premenstrual symptoms and 60.4% used medication such as herbal medication and home remedies to relieve menstrual irregularities, and 12.1% of the students missed classes due to menstrual irregularities. A non-significant relationship was found between menstrual irregularities during exams and students’ demographics, academic year, and age at menarche, while oligomenorrhea, a heavier than normal bleed, a longer than normal cycle, and missing classes due to menstrual irregularities were significantly higher among single students as opposed to married students.

Conclusion

The results showed that female medical students have a significant frequency of menstruation abnormalities during exams period. Colleges should raise awareness among medical students about coping with examination stress and seeking medical care for menstrual abnormalities.

Keywords: Menstrual irregularities, Dysmenorrhea, Exam, Medical student

Introduction

The menstrual cycle is the most important measure of female reproductive health [1, 2]. It is a normal physiological process where the uterus eliminates the endometrium (innermost lining layer) and allows a regulated loss of endometrial tissue, mucus, and blood through the vagina every month [3]. Menstruation lasts 2 to 6 days and occurs between every 21 and 35 days (counting from the start of one cycle to the start of the next cycle), but this can vary from month to month depending on the woman [4].

Menstrual cycle irregularity is one of the most common reasons for women to see gynecologists and family physicians [5]. The menstrual cycle is considered to be irregular if there are any changes in frequency and irregularity of onset, duration of flow, and volume of blood from the regular menstrual cycle [6]. It can have significant implications for women's health and can lead to major health consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, infertility, Type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis [7–12].

There are many risk factors in an irregular menstrual cycle. A study conducted in Korea on 4,788 women found that irregular menstruation is strongly associated with important factors, such as body mass index, perceived level of stress, and smoking status [13].Also, some evidence suggests that the risk of an irregular menstrual cycle tends to increase with mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression [14]. Another study in 2020 found that females who use nicotine are at a five-times higher risk of an irregular menstrual cycle. Other factors include marriage, having a cesarean section, and using contraception [5]. A 2019 study found that the prevalence of irregular menstruation is 11.83%; however, women with longer working hours have double the risk for irregular menstruation compared to women working shorter hours [11]. In recent years, nutrition and lifestyle have been linked to menstrual disorders. This has been primarily attributed to the effects of specific meals and practices on vascular irrigation or the amount of estrogens and prostaglandins—the hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle [15–19]. A study conducted in India found that irregular menstruation is the third most common menstrual disorder among Indian medical students, accounting for 29% of the total. An irregular menstrual cycle was most common among Lebanese nursing students (80.7%) [20]. A study completed in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, found that 91% of female students studying health sciences had menstrual disorders, including an irregular menstrual cycle (27%) [21]. A study in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, among medical students at King Abdulaziz University, found that that 60.9% of students suffered from dysmenorrhea [22], and a study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, among female medical students in King Saud University found the prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea was 80.1% [23]. Menstrual issues have a detrimental influence on women's quality of life, resulting in a variety of constraints, absenteeism, and poor academic performance [24–26]. Although menstrual cycle irregularity is a major public health issue among females, little research has been undertaken on this critical issue among medical students in Jeddah. This study was conducted to identify menstrual cycle irregularities during exams among female medical students at King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study was completed at KAU in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia between September and October 2021. KAU is a public university in Jeddah Which consider the largest city after Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, with student enrolment over 80,000. It is considered one of the top institutions of higher education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [27], and has been ranked as the top Arab university by Times Higher Education [28].

Study participants

Female medical students (n = 450) at KAU participated in the study. Medical education in KAU is about 6 years divided into two stages after freshman year. 2nd and 3rd year are basic sciences medicine. 4th, 5th, and 6th are clinical, and students learn by attending with physicians in a hospital setting. Participants were all female medical students, in their second to sixth years, including basic sciences and clinical medicine. The exclusion criteria included any female with chronic illness, gynecological diseases, or breastfeeding that might affect their period.

Sample size determination

For this study, the estimated sample size was derived from the online Raosoft sample size calculator [29].The sample size was calculated based on a response rate of 50%, a confidence interval of 98%, and a margin of error of 5%, with a total population of about 1,390. Counting after freshman year, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th year female medical students at KAU, the largest required sample size is 400. Accordingly, this study included a randomized sample of 450 students.

Data collection

Data collection was done using a pretested, structured and validated self-administered English questionnaire. After an evaluation of literature review, the questionnaire was changed and adjusted for the purpose of this study. The questionnaire was distributed between July to August 2021 among female medical students at KAU [30]. The questionnaire consisted of four parts. The first part included questions about socio-demographic data including age, marital status, academic year, weight and height, and age at menarche. The second part included questions about types of menstrual irregularities during exams. Amenorrhea was explained to students as absence of menstrual periods; oligomenorrhea was explained as infrequent menstrual periods (fewer than six to eight periods per year); and dysmenorrhea was explained as painful menstruation. Premenstrual symptoms were mentioned to students as mood swings, tender breasts, and food cravings. Questions were included on the type of medication used to relieve menstrual irregularities (allopathic, herbal medication, or home remedies) and whether the participant thought it was effective or not. The third part included questions about history of being diagnosed with chronic medical conditions such as (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, fibroids, polycystic ovary syndrome and others) and about family history of menstrual irregularities. The fourth part included questions about the impact of menstrual irregularities on the student such as missing classes during menstrual irregularities, seeking any medical help from a clinician, and discussing this problem with a family member or a friend.

The experts rated each item on a 4-point scale based on its suitability and relevance as follows: adequate (simple, relevant and clear) equal 4 point, adequate but needs minor revision equal 3 point, needs major modification equal 2 point ,or not so adequate (can be omitted) equal 1 point. The percentage of all items with a 3 or 4 rating from experts is known as the content validity index (CVI). With a 4-rating 80 percent of the time, a score is thought to have good validity. The CVI of the planned questionnaire was established. To assess the reliability, Cronbach's alpha value was determined as 0.82.

Research ethics

This study was approved by King Abdulaziz University Hospital, biomedical ethical committee (Ref No. 384-21). All study participants were notified about the research objectives, and informed consent was obtained.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2016 was used for data entry, and SPSS version 26 was used to analyze the data. To assess the relationship between variables, qualitative data was expressed as numbers and percentages, and the chi-squared test (χ2) was used. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was done to assess the risk factors of menstrual irregularities. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

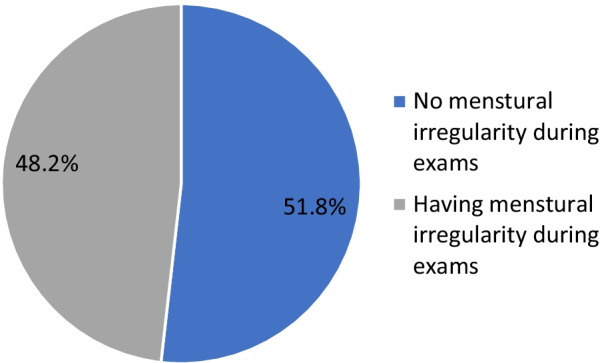

Table 1 shows that 96% of studied students had an age ranging from 18 to 24 years; 98.2% were single, and 28.7% were fourth-year students. Figure 1 illustrates that 217 (48.2%) of participants had menstrual irregularities during exams.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants according to their demographic data, academic year and age at menarche (N = 450)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 432 (96) |

| 25–31 | 18 (4) |

| Marital status | |

| Divorced | 2 (0.4) |

| Married | 6 (1.3) |

| Single | 442 (98.2) |

| Academic year | |

| 2nd | 117 (26) |

| 3rd | 73 (16.2) |

| 4th | 129 (28.7) |

| 5th | 72 (16) |

| 6th | 59 (13.1) |

| Age at menarche (mean ± SD) | 12.79 ± 1.55 |

Fig. 1.

Percentage distribution of participants according to presence of menstrual irregularity during exams

Table 2 shows that the most common menstrual irregularity during exams was dysmenorrhea (70.9%), followed by normal cycle lengthened (45.6%), and heavier than normal bleed (41.9%). Of these, 93% suffered from premenstrual symptoms, and 60.4% used medication to relieve menstrual irregularities—both herbal medication and home remedies, and 82.4% reported the effectiveness of these. According to students' answers, we found that most of the participants have more than one type of menstrual irregularity. Family history of menstrual irregularities was present among 43.8% of students with menstrual irregularities during exams, and only 26.8% reported seeking medical help from a clinician. Of these, 76% discussed this problem with a family member or a friend, and 12.1% missed classes due to menstrual irregularities. A non-significant relationship was found between menstrual irregularities during exams and students’ demographics, academic year, or age at menarche (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Distribution of participants with menstrual irregularities during exams according to menstrual history (N = 217)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of menstrual irregularities (N = 217) (more than one answer was allowed) | |

| Amenorrhea | 86 (39.6) |

| Oligomenorrhea | 56 (25.8) |

| Dysmenorrhea: painful menstruation | 154 (70.9) |

| Heavy bleed than normal bleed | 91 (41.9) |

| Normal cycle lengthened | 99 (45.6) |

| Normal cycle shortened | 73 (33.6) |

| Do you suffer from premenstrual symptoms? (N = 217) | |

| No | 15 (7) |

| Yes | 202 (93) |

| Do you use medication to relieve menstrual irregularities? (N = 217) | |

| No | 86 (39.6) |

| Yes | 131 (60.4) |

| If yes, which of the following medication do you need? (N = 131) | |

| Allopathic | 22 (16.7) |

| Allopathic and herbal medication | 16 (12.2) |

| Allopathic, herbal medication and home remedies | 16 (12.2) |

| Allopathic and home remedies | 5 (3.8) |

| Herbal medication | 24 (19) |

| Herbal medication and home remedies | 35 (26.7) |

| Home remedies | 13 (2.2) |

| Do you think that this medication is effective? (N = 131) | |

| No | 23 (17.6) |

| Yes | 108 (82.4) |

| Is there a family history of menstrual irregularities? (N = 217) | |

| No | 122 (56.2) |

| Yes | 95 (43.8) |

| Did you seek any medical help from any clinician? | |

| No | 159 (73.2) |

| Yes | 58 (26.8) |

| Did you discuss this problem with a family member or a friend? | |

| No | 52 (24) |

| Yes | 165 (76) |

| Did you miss classes when you had menstrual irregularities? | |

| No | 99 (45.6) |

| Sometimes | 92 (42.3) |

| Yes | 26 (12.1) |

Table 3.

Relationship between menstrual irregularities during exams and students’ demographics, academic year and age at menarche

| Variable | Menstrual irregularities | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |||

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 223 (51.6) | 209 (48.4) | 0.1 | 0.743 |

| 25–31 | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100) | 5.19 | 0.074 |

| Married | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||

| Single | 232 (52.5) | 210 (47.5) | ||

| Academic year | ||||

| 2nd | 58 (49.6) | 59 (50.4) | 2.34 | 0.673 |

| 3rd | 36 (49.3) | 37 (50.7) | ||

| 4th | 73 (56.6) | 56 (43.4) | ||

| 5th | 34 (47.2) | 38 (53.8) | ||

| 6th | 32 (54.2) | 27 (45.8) | ||

| Age at menarche (mean ± SD) | 12.86 ± 1.49 | 12.72 ± 1.61 | 0.77* | 0.436 |

* = U test

A non-significant relationship was found between students’ age and type of menstrual irregularities, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, medical and family consultation, or missing classes due to menstrual irregularities (p > 0.05) (Table 4). A non-significant relationship was found between academic year and type of menstrual irregularities, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, medical and family consultation, or missing classes due to menstrual irregularities (p > 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Relationship between students’ age and type of menstrual irregularities, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, medical and family consultation and missing classes due to menstrual irregularities

| Variable | Age (years) | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–30 | |||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |||

| Type pf menstrual irregularities (N = 217) | ||||

| Amenorrhea: absence of menstrual periods | 84 (97.7) | 2 (2.3) | 0.79 | 0.672 |

| Oligomenorrhea | 55 (98.2) | 1 (1.8) | 0.81 | 0.665 |

| Dysmenorrhea | 147 (95.5) | 7 (4.5) | 1.12 | 0.569 |

| Heavy bleed than normal bleed | 87 (95.6) | 4 (4.4) | 0.31 | 0.855 |

| Normal cycle lengthened | 93 (93.9) | 6 (6.1) | 2.77 | 0.249 |

| Normal cycle shortened | 71 (97.3) | 2 (2.7) | 0.36 | 0.834 |

| Do you suffer from premenstrual symptoms? (N = 217) | ||||

| No | 15 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0.67 | 0.713 |

| Yes | 194 (96) | 8 (4) | ||

| Do you use medication to relieve menstrual irregularities? (N = 217) | ||||

| No | 83 (96.5) | 3 (3.5) | 0.12 | 0.941 |

| Yes | 126 (96.2) | 5 (3.8) | ||

| Do you think that this medication is effective? (N = 131) | ||||

| No | 23 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 1.06 | 0.588 |

| Yes | 103 (95.4) | 5 (4.6) | ||

| Did you seek any medical help from any clinician? | ||||

| No | 153 (96.2) | 6 (3.8) | 0.11 | 0.942 |

| Yes | 56 (96.6) | 2 (3.4) | ||

| Did you discuss this problem with a family member or a friend? | ||||

| No | 48 (92.3) | 4 (7.7) | 2.96 | 0.227 |

| Yes | 161 (97.6) | 4 (2.4) | ||

| Did you miss classes when you had menstrual irregularities? | ||||

| No | 97 (98) | 2 (2) | 5.04 | 0.169 |

| Sometimes | 89 (96.7) | 3 (3.3) | ||

| Yes | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | ||

Table 5.

Relationship between students’ academic year and type of menstrual irregularities, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, medical and family consultation and missing classes due to menstrual irregularities

| Variable | Academic year | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic years (2nd, 3rd) No. (%) | Clinical years (4th, 5th, 6th) No. (%) | |||

| Type pf menstrual irregularities (N = 217) | ||||

| Amenorrhea | 42 (48.8) | 44 (51.2) | 1.93 | 0.38 |

| Oligomenorrhea | 26 (46.4) | 30 (53.6) | 0.84 | 0.655 |

| Dysmenorrhea: painful menstruation | 66 (42.9) | 88 (57.1) | 1.11 | 0.573 |

| Heavy bleed than normal bleed | 43 (47.3) | 48 (52.7) | 1.28 | 0.527 |

| Normal cycle lengthened | 51 (51.5) | 48 (48.5) | 4.65 | 0.098 |

| Normal cycle shortened | 38 (52.1) | 35 (47.9) | 3.45 | 0.178 |

| Do you suffer from premenstrual symptoms? (N = 217) | ||||

| No | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 0.73 | 0.691 |

| Yes | 89 (44.1) | 113 (55.9) | ||

| Do you use medication to relieve menstrual irregularities? (N = 217) | ||||

| No | 37 (43) | 49 (57) | 0.78 | 0.675 |

| Yes | 59 (45) | 72 (55) | ||

| Do you think that this medication is effective? (N = 131) | ||||

| No | 9 (39.1) | 14 (60.9) | 1.25 | 0.533 |

| Yes | 51 (46.8) | 57 (53.2) | ||

| Did you seek any medical help from any clinician? | ||||

| No | 75 (47.2) | 84 (52.8) | 2.79 | 0.247 |

| Yes | 21 (36.2) | 37 (63.8) | ||

| Did you discuss this problem with a family member or a friend? | ||||

| No | 20 (38.5) | 32 (61.5) | 1.63 | 0.442 |

| Yes | 76 (46.1) | 89 (53.9) | ||

| Did you miss classes when you had menstrual irregularities? | ||||

| No | 45 (45.5) | 54 (54.5) | 0.82 | 0.844 |

| Sometimes | 40 (43.5) | 52 (56.5) | ||

| Yes | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.7) | ||

Oligomenorrhea, a heavier than normal bleed, a longer normal cycle, using medications to relieve pain and missing classes due to menstrual irregularities were significantly higher among single students (p < 0.05) (Table 6). However, a non-significant relationship was found between students’ marital status and amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, shortening of the normal cycle, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, and medical or family consultations (p > 0.05).

Table 6.

Relationship between students’ marital status and type of menstrual irregularities, premenstrual symptoms, medication use, medical and family consultation and missing classes due to menstrual irregularities

| Variable | Marital status | χ2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divorced No. (%) |

Married No. (%) |

Single No. (%) |

|||

| Type of menstrual irregularities (N = 217) | |||||

| Amenorrhea | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 84 (97.7) | 7.93 | 0.094 |

| Dysmenorrhea | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 149 (96.8) | 7.4 | 0.116 |

| Normal cycle shortened | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.1) | 96 (94.5) | 8.44 | 0.077 |

| Type pf menstrual irregularities (N = 217) | |||||

| Oligomenorrhea | |||||

| No | 2 (1.2) | 5 (3.1) | 154 (95.7) | 9.72 | 0.045 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (100) | ||

| No Heavy bleed than normal bleed | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.2) | 122 (96.8) | 12.65 | 0.013 |

| Yes | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | 88 (96.7) | ||

| No Normal cycle lengthened | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 116 (98.3) | 10.92 | 0.027 |

| Yes | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 94 (94.9) | ||

| Do you suffer from premenstrual symptoms? (N = 217) | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) | 14 (93.3) | 7.82 | 0.098 |

| Yes | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 196 (97) | ||

| Do you use medication to relieve menstrual irregularities? (N = 217) | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.7) | 82 (95.3) | 13.83 | 0.008 |

| Yes | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 128 (97.7) | ||

| Do you think that this medication is effective? (N = 131) | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (100) | 6.86 | 0.143 |

| Yes | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 105 (97.2) | ||

| Did you seek any medical help from any clinician? | |||||

| No | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 154 (96.9) | 7.49 | 0.112 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | 56 (96.6) | ||

| Did you discuss this problem with a family member or a friend? | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 51 (98.1) | 6.59 | 0.159 |

| Yes | 2 (1.2) | 4 (2.4) | 159 (96.4) | ||

| Did you miss classes when you had menstrual irregularities? | |||||

| No | 1 (1) | 5 (5.1) | 93 (93.9) | 16.22 | 0.013 |

| Sometimes | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 91 (98.9) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (100) | ||

Table 7 shows that on doing the multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the risk factors of menstrual irregularities, none of the independent variables had a significant relationship (p ≥ 0.05).

Table 7.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors of menstrual irregularities

| B | Wald | p-value | Odds Ratio (CI: 95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.534 | 0.01 (0.13–1.02) |

| Marital status | 0.5 | 0.61 | 0.132 | 0.2 (0.6–0.13) |

| Academic year | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.142 | 0.3 (0.3–1.09) |

| Age at menarche (mean ± SD) | 0.9 | 0.86 | 0.073 | 0.98 (1.5–1.09) |

Discussion

Excessive stress during exams is one of the most common concerns among university students around the world. It can lead to physiological, hormonal, immunological, psychological, and behavioral changes, which can lead to menstrual cycle irregularity [31]. The purpose of our study was to evaluate menstrual cycle irregularities at the time of exams among female medical students at KAU in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Most of the sample were single young women with a mean age of menarche at 12.79. Almost half the sample presented with menstrual cycle irregularity. Medical students are at increased risk of menstrual disorders due to lifestyles that include lack of sleep, irregular diet, and exercise habits [32]. A previous study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, among different university colleges found that four out of 10 female students suffered from menstrual cycle disturbance [31]. This could be the result of psychological stress, which may lead to an imbalance between estrogen and progesterone ratios [31–33]. In contrast, another study in India found that the level of stress among medical students was above average, or the stress level was higher compared to non-medical students, but this stress did not, in general, affect the regularity of the women’s periods among their sample [33].

The most prevalent menstrual irregularities reported by the students in the current study were dysmenorrhea, followed by cycle lengthening, and heavy bleeding. These results support a study done in Saudi Arabia that found that dysmenorrhea was the most common irregularity [34]. The majority of participants in this study had dysmenorrhea during the exam period, and this supports findings by Kollipaka et al. which found that dysmenorrhea was the most common menstrual abnormalities reported by students [35]. A study in Nigeria also found that dysmenorrhea was the most common problem associated with female medical students [36].

The current study showed that most students with any form of irregularity can be assisted with medication, especially herbal medication and home remedies, and this reduced the number of classes skipped due to menstrual irregularity. A study done in 2018 also found that herbal medication can play a significant role in treating menstrual irregularity [37].

Several studies discuss the relationship between the academic level and menstrual cycle irregularity. In this study, a non-significant relationship indicated that most students with menstrual changes were in the first 3 years of study. On the other hand, a study done in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia, found that students in clinical years had high levels of stress and were two times more likely to suffer from menstrual changes [34]. A study in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, found that many students exposed to similar levels of stress had normal menstruation [21]. However, the current study suggests that there is a high prevalence of dysmenorrhea among medical students, most of whom were in the clinical years. Previous literature showed that the most frequent gynecological condition among female medical students is dysmenorrhea [20, 38]. In contrast, a study by Ibrahim et al. found that the prevalence of dysmenorrhea was considerably greater among students in the basic years which is the first 3 years in medical school compared to those in the clinical years which Is the last 3 years [22]. This may be due to the pressure of adapting to a new location, which may put a psychological burden on medical students in the clinical years who have recently entered hospital settings.

In addition, the menstrual cycle lengthened in almost half of students in this study. In contrast, a study in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, found that the majority of participants had a normal length cycle [21]. The current study showed that more than one-third of participants reported that their periods were heavier than usual, compared with a cross‐sectional study done among medical students that found almost two-thirds of students reported normal blood loss [21].

In this study, almost half the students had premenstrual symptoms. A study in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, reported a strong positive relationship between both premenstrual symptoms and stress levels [39]. A study in South-Eastern Nigeria found that less than half of students had premenstrual symptoms [40]. Also, more than half the students used medication to relieve the pain, similar to a study in India that found that minorities use painkillers to relieve menstrual pain [33].

The current study found no significant relationship between the age of the students and type of menstrual irregularities, similar to a study in South-Eastern Nigeria that found no relationship between age and menstrual changes (p = 0.901). This may be because the ages were very close to each other [40].

Limitations

This study has several limitations, despite using a validated questionnaire with a large sample size. A limitation was that it was a cross-sectional study. The study was limited to students in one university, which may not represent the general population of women. The menstrual patterns were based on students’ self-reports, rather than clinical examinations or hormone measurements, which may have led to skewing of the results. Some factors that may be confounders were not assessed in this study such as the usual menstrual pattern of the participant, use of oral contraceptive pills, and other habits during the exams period that may have effects on the normal cycle such as sleep deprivation, caffeine intake, physical activity, quality of food, smoking, and level of psychological stress. Future research could be conducted in other colleges and include questions about these factors.

Recommendations

This study showed that female medical students have a significant frequency of menstruation abnormalities during exams. Based on these results, and to minimize the negative effects of the educational process, it is recommended that universities educate female students about relaxation techniques, such as yoga, before the exams. Also, females should have a better understanding of menstrual pain and perceptions of treatment choices could be improved.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to detect menstrual cycle irregularities during exam among female medical students in King Abdulaziz University. According to that, we find significant frequency of menstruation abnormalities during exams. Which indicate that exam can disturb the menstrual cycle. Consequently, we recommend universities to educate female students about relaxation techniques, such as yoga. Also, they should have a better understanding of menstrual pain and their treatment choices.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all medical students who participated in the research.

Author contributions

MA, AA, MA, FF and BS participated in writing the original draft of this manuscript. Also, all authors listed have sufficiently contributed to the development, editorial changes, and final approval of the final manuscript. Data collection was performed by MA, AA, MA, FF and BS. Dr. SA edited the main manuscript text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The corresponding author can provide access to the datasets generated and analyzed during the current investigation based on request at any time.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before completing the questionnaire, all study participants were informed about the objectives of the study, they were assured of the confidentiality of information, and then written informed consent was obtained from the individuals. The Ethics Committee of King Abdulaziz University Hospital confirmed the ethics of that study; (Ref No. 384-21). The research study has been approved by KAU Research Ethics Committee (Ref No. 384-21) and all the methods done following the relevant guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maisam H. Alhammadi, Email: MaisamAlhammadi@gmail.com

Afaf M. Albogmi, Email: Afaf.albogmi18@gmail.com

Manar K. Alzahrani, Email: M.khalidz188@gmail.com

Bashayer H. Shalabi, Email: Bshalabi0005@stu.kau.edu.sa

Fatma A. Fatta, Email: Fatmahfatta@gmail.com

Samera F. AlBasri, Email: albasri@kau.edu.sa

References

- 1.Small CM, Manatunga AK, Klein M, Feigelson HS, Dominguez CE, McChesney R, et al. Menstrual cycle characteristics: associations with fertility and spontaneous abortion. Epidemiology. 2006;17(1):52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000190540.95748.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolstad HA, Bonde JP, Hjøllund NH, Jensen TK, Henriksen TB, Ernst E, et al. Menstrual cycle pattern and fertility: a prospective follow-up study of pregnancy and early embryonal loss in 295 couples who were planning their first pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(3):490–496. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins SM, Matzuk MM. The menstrual cycle: basic biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1135:10–18. doi: 10.1196/annals.1429.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ussher JM, Chrisler JC, Perz J. Routledge international handbook of women's sexual and reproductive health. London: Routledge; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafar M. Risk factors associated with irregular menstrual cycle among young women. Fertil Sci Res. 2020;7(1):54. doi: 10.4103/2394-4285.288716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS. The FIGO systems for nomenclature and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: who needs them? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowland AS, Baird DD, Long S, Wegienka G, Harlow SD, Alavanja M, et al. Influence of medical conditions and lifestyle factors on the menstrual cycle. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):668–674. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan JR, Manuck SB. Ovarian dysfunction, stress, and disease: a primate continuum. Ilar J. 2004;45(2):89–115. doi: 10.1093/ilar.45.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harlow SD, Ephross SA. Epidemiology of menstruation and its relevance to women's health. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(2):265–286. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich-Edwards JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):2013–2017. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ok G, Ahn J, Lee W. Association between irregular menstrual cycles and occupational characteristics among female workers in Korea. Maturitas. 2019;129:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich-Edwards J, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, et al. Long or highly irregular menstrual cycles as a marker for risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(19):2421–2426. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bae J, Park S, Kwon JW. Factors associated with menstrual cycle irregularity and menopause. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0528-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu M, Han K, Nam GE. The association between mental health problems and menstrual cycle irregularity among adolescent Korean girls. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balbi C, Musone R, Menditto A, Di Prisco L, Cassese E, D'Ajello M, et al. Influence of menstrual factors and dietary habits on menstrual pain in adolescence age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91(2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(99)00277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Cintio E, Parazzini F, Tozzi L, Luchini L, Mezzopane R, Marchini M, et al. Dietary habits, reproductive and menstrual factors and risk of dysmenorrhoea. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13(8):925–930. doi: 10.1023/A:1007427928605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajalan Z, Alimoradi Z, Moafi F. Nutrition as a potential factor of primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review of observational studies. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2019;84(3):209–224. doi: 10.1159/000495408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavallaee M, Joffres MR, Corber SJ, Bayanzadeh M, Rad MM. The prevalence of menstrual pain and associated risk factors among Iranian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(5):442–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu Helwa HA, Mitaeb AA, Al-Hamshri S, Sweileh WM. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea and predictors of its pain intensity among Palestinian female university students. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0516-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karout N, Hawai S, Altuwaijri S. Prevalence and pattern of menstrual disorders among Lebanese nursing students. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(4):346–352. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rafique N, Al-Sheikh MH. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their association with psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med J. 2018;39(1):67. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.1.21438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibrahim NK, AlGhamdi MS, Al-Shaibani AN, AlAmri FA, Alharbi HA, Al-Jadani AK, et al. Dysmenorrhea among female medical students in King Abdulaziz University: prevalence, predictors and outcome. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31(6):1312. doi: 10.12669/pjms.316.8752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashim RT, Alkhalifah SS, Alsalman AA, Alfaris DM, Alhussaini MA, Qasim RS, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its effect on the quality of life amongst female medical students at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J. 2020;41(3):283. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.3.24988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández-Martínez E, Onieva-Zafra MD, Abreu-Sánchez A, Fernández-Muñóz JJ, Parra-Fernández ML. Absenteeism during menstruation among nursing students in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(1):53. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armour M, Parry K, Manohar N, Holmes K, Ferfolja T, Curry C, et al. The prevalence and academic impact of dysmenorrhea in 21,573 young women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28(8):1161–1171. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Martínez E, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Fernández ML. The impact of dysmenorrhea on quality of life among Spanish female university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(5):713. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Our history KING ABDULAZIZ UNUVERSITY 2021. https://www.kau.edu.sa/Content-0-EN-2384.

- 28.Arab University Rankings 2021; 2021. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-univ%C3%A9rsity-rankings/2021.

- 29.Raosoft Inc. RaoSoft® sample size calculator; 2004. Cited 2020. http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html

- 30.Natt AM, Khalid F, Sial SS. Relationship between examination stress and menstrual irregularities among medical students of Rawalpindi Medical University. J Rawalpindi Med Coll. 2018;22(S-1):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gezira KB, AbdulRaheem EM. Pre-examination stress among university students at Western Riyadh. Int J Curr Res. 2014;6(12):11076–11078. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sood M, Devi A, Daher AAM, Razali S, Nawawi H, Hashim S, et al. Poor correlation of stress levels and menstrual patterns among medical students. J Asian Behav Stud. 2017;2(5):73–78. doi: 10.21834/jabs.v2i5.221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh R, Sharma R, Rajani H. Impact of stress on menstrual cycle: a comparison between medical and non medical students. Saudi J Health Sci. 2015;4(2):115. doi: 10.4103/2278-0521.157886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aljadidi M, Almutrafi O, Bamousa R, Alshehri S, AlRashidi A. The Influence of exam stress on menstrual dysfunctions in Saudi Arabia. J Health Educ Res Dev. 2016;4(04):196. doi: 10.4172/2380-5439.1000196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kollipaka R, Arounassalame B, Lakshminarayanan S. Does psychosocial stress influence menstrual abnormalities in medical students? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(5):489–493. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.782272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amaza DS, Sambo N, Zirahei JV, Dalori MB, Japhet H, Toyin H. Menstrual pattern among female medical students in University of Maiduguri, Nigeria. J Adv Med Med Res. 2012;2:327–337. doi: 10.9734/BJMMR/2012/1018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moini Jazani A, Hamdi K, Tansaz M, Nazemiyeh H, Sadeghi Bazargani H, Fazljou SMB, et al. Herbal medicine for oligomenorrhea and amenorrhea: a systematic review of ancient and conventional medicine. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–22. doi: 10.1155/2018/3052768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh A, Kiran D, Singh H, Nel B, Singh P, Tiwari P. Prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhea: a problem related to menstruation, among first and second year female medical students. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;52(4):389–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alaskar B, Alhunaif S, Shaheen MA, Alkadri H. Menstrual abnormalities and their association with stress and quality of life among females studying health sciences. 2021.

- 40.Ekpenyong CE, Davis K, Akpan U, Daniel N. Academic stress and menstrual disorders among female undergraduates in Uyo, South Eastern Nigeria-the need for health education. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2011;26(2):193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author can provide access to the datasets generated and analyzed during the current investigation based on request at any time.