Abstract

This article is based on a report presented at the Scientific Session of the RAS General Meeting (Moscow, December 15, 2021). The reaction of society to the pandemic in Russia and other countries of the world is analyzed from an anthropological point of view. The features of the behavior and psychological reaction of residents of different regions, professional groups, and ethnocultural communities are considered with account for gender, age, and cultural characteristics (collectivism‒individualism, looseness‒tightness, power distance). Particular attention is paid to phobias and social activity during the pandemic; the growing role of nation-states in overcoming the consequences of the pandemic is discussed. The results presented can be used as an additional source of information for taking effective measures finally to overcome the pandemic and, most importantly, its negative social and political consequences.

Keywords: coronavirus pandemic, Russia, anxiety and distress, empathy, cross-cultural studies, pandemic phobias, social activism, the role of the state

Although the global coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic continues, more than two years of fighting this evil have made it clear that the key to success, in addition to specific medical measures, is an adequate response of people to government instructions to prevent the spread of the disease, as well as the culturally determined perception of such global challenges by a particular society. Confidence in the effectiveness of measures taken at the state level, a sense of personal risk, a stronger sense of social responsibility, and many other social phenomena contribute to improving the conditions for preventing the spread of the infection. The current experience of combating the pandemic in Russia and abroad has shown that achieving civil support for the measures taken is as important as the key goal as the creation of antiepidemic drugs.

The sociocultural consequences of the pandemic will obviously be longer than the epidemic itself. They will change the tactics and strategy of the authorities relative to preventive measures and vaccinations against various diseases, public prejudices about vaccination of adults and children, sanitary rules when crossing state borders, requirements on precautions in crowded places, and the practice of everyday communication at the personal and collective professional levels. No doubt, the experience of social behavior against the background of the pandemic, as well as the policy of nation-states in overcoming it, must be studied carefully to prevent biological and other threats on a global scale.

This study analyzes the public reaction to the pandemic in Russia and other countries from an anthropological standpoint, as well as the features of perceiving the new situation by representatives of different regions, age and professional groups, and ethnocultural communities. The growing role of nation-states in overcoming the negative social and political consequences of the pandemic is discussed. We have summarized the results of several studies conducted by sociocultural anthropologists at different stages of the pandemic. In 2019–2020, the studies were focused on behavioral features and psychological reactions of the population in the conditions of its first wave in four regions of Russia and at the cross-cultural level in 23 countries of the world. Then, in the last months of 2021, that is, during the unprecedented increase in the epidemic load, the situation in the regions of Russia associated with the formation of public fears and phobias was analyzed and assessed.

ANXIETY UNDER THE PANDEMIC IN RUSSIA: FIRST WAVE

Data on the first coronavirus wave testify to regional differences in the response to the epidemic. The psychological state and reaction of people to its spread and the restrictions imposed by local authorities during the first wave were analyzed on the example of four Russian regions—Moscow, Tatarstan, Rostov oblast, and the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug [1]. These regions were chosen as examples because they differed from each other in terms of the dynamics of the measures taken by the regional authorities. While Moscow was introducing more and more new bans and restrictions gradually, up to a complete lockdown three weeks after the first patient with COVID-19 was detected, the authorities in other regions acted more decisively. Despite much lower incidence statistics in general, Tatarstan, Rostov oblast, and the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug established a self-isolation regime earlier. The Republic of Tatarstan introduced the lockdown two weeks after the first case of the disease had been detected; the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, after 12 days; and Rostov oblast, after a week.

The data were obtained in the interval from April 29 to June 21, 2020, the total sample being 1903 people, including 232 in Moscow, 362 in Tatarstan, 1023 in Rostov oblast, and 286 in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug. Most of the respondents were university students. Note that, at the time of the study, Moscow had the largest number of detected cases and deaths due to COVID-19 and thus stood out against the backdrop of the other three regions, while the lowest rates were noted in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug. To assess the level of anxiety, the GAD-7 questionnaire [2] in an adapted version (GAD-7 questionnaire, 2013) was used. It included seven items describing symptoms of anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) based on the respondents’ personal experiences over the preceding 14 days. Anxiety was assessed on the four-point Likert scale (from 0 meaning “not at all” to 3 meaning “almost every day”), and the scores for all items were subsequently summed up, which made it possible to get an idea of the level of anxiety: minimal, 0–4; moderate, 5‒9; medium, 10‒14; and high, 15‒21.

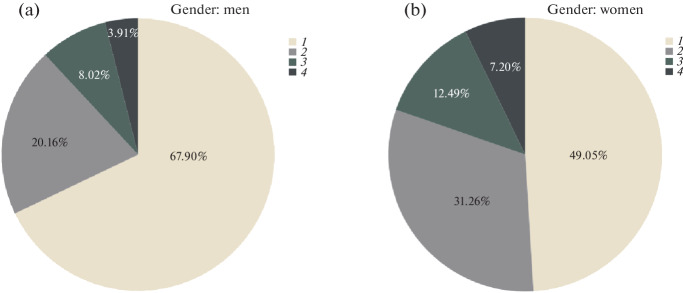

Overall, according to the generalized Russian sample, men demonstrated a significantly lower level of anxiety compared to women (χ2 = 52.079, df = 3, p = 0.0001, n = 1901) (Figs. 1a, 1b). High and medium levels of anxiety were found in 20% of women and only in 12% of men. The norm (low level of anxiety) for this indicator was noted in 68% of men and 49% of women. Comparison of the four samples showed that the most significant proportion of respondents with a high level of anxiety was in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug (10.49%) and the lowest was in Rostov oblast (4.50%). The most respondents with a minimal level of anxiety were found in Rostov oblast (59.82%), and the fewest respondents with minimal anxiety were in Moscow (34.91%). Significant gender differences in the GAD-7 were determined for each region, and everywhere the level of anxiety among women was consistently higher than among men.

Fig. 1.

The level of anxiety according to the GAD-7 questionnaire for (a) men and (b) women. (1) Minimal level of anxiety, (2) moderate level of anxiety, (3) average level of anxiety, (4) high level of anxiety.

Cross-cultural data for 23 countries of the world (the total sample was 15 375 people), collected using an identical method [3], also showed that women were more anxious than men (χ2 = 258.53, df = 3, р = 0.0001, n = 15 342). The highest rates of anxiety were reported in Brazil, Iraq, Canada, and the United States. Note that, in general, anxiety indicators during the pandemic turned out to be higher than in the previous period [4]. A significant factor in the level of anxiety is age; the older the person, the lower the level of anxiety was in both sexes.

EMPATHY AND COMPASSION UNDER THE PANDEMIC IN RUSSIA: FIRST WAVE

Of exceptional interest for researchers is the problem of empathy and the readiness to help each other under the pandemic [4, 5]. Empathy is a response to the experiences of another person. To measure it, three scales of the multifactorial questionnaire of empathy by M. Davis (Interpersonal Reactivity Index, IRI) (decentration, empathic concern, and empathic distress) [6], adapted by Budagovskaya et al. [7], were used. The “decentration” scale assesses the ability to perceive, understand, and consider the point of view of another person; the “empathic concern” scale evaluates feelings of empathy directed at another person (sympathy, pity, desire to help); and the “empathic distress” scale assesses negative feelings arising in response to the suffering and experiences of the other and the desire to get rid of them in any way for the sake of one’s peace of mind. The three scales were analyzed as dependent variables using the method of multivariate analysis of covariance within the framework of a general linear model, where gender and region were used as independent variables, and the age of the respondents was used as a covariate.

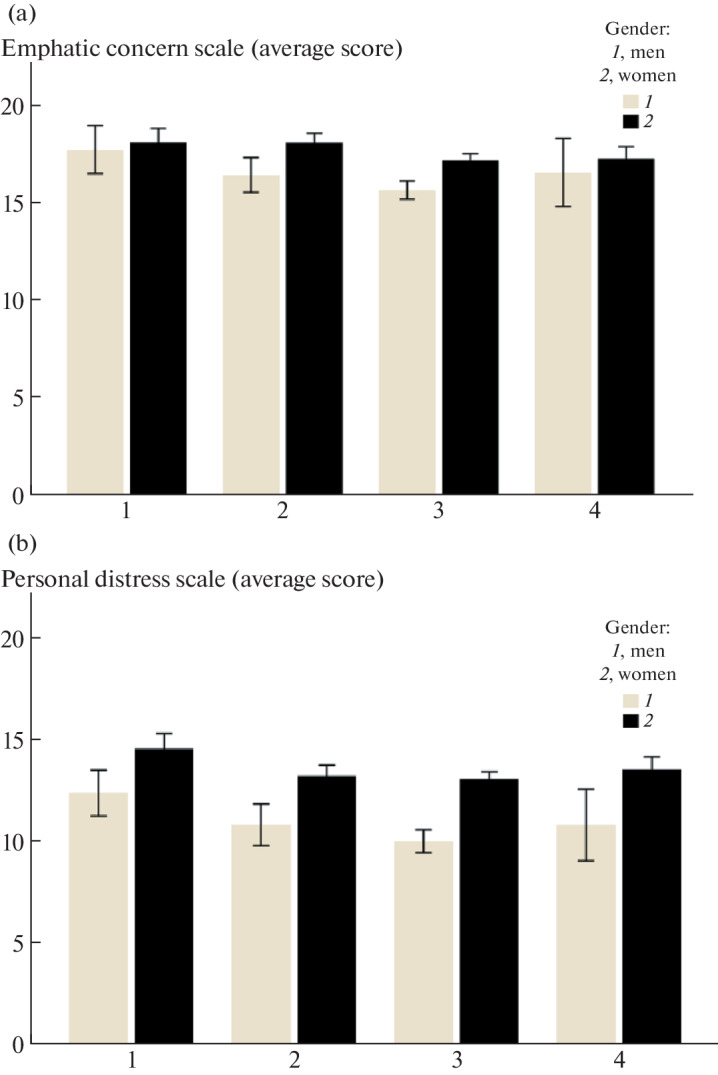

The results of the analysis show that the relationship between the independent variables and the values on the decentration scale is negligibly small, which makes it possible to ignore the data on this scale. The mean scores on the empathic concern scale were significantly associated with gender (F = 32.848, p = 0.0001, η = 0.02, n = 1903), but these differences were found only in two regions (Tatarstan and Rostov oblast) (Fig. 2a). The scores on the empathic distress scale were associated with gender (F = 118.307, p = 0.0001, η = 0.06, n = 1902) and region (F = 10.185, p = 0.0001, η = 0.02, n = 1902) (Fig. 2b). Although the effects on this scale were small, the findings suggest that women demonstrate higher levels of empathic concern than men during the pandemic and are more responsive to the suffering of others. In addition, our results suggest that the level of empathic distress depends on cultural attitudes and motivations. It is noteworthy that female Muscovites gave significantly higher marks on the empathic distress scale than women from other regions. Muscovite men in terms of empathic distress significantly exceeded the residents of Tatarstan and Rostov oblast but did not differ from men from the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

Fig. 2.

Average scores on (a) the empathic concern scale and (b) the empathic distress scale of the M. Davis empathy questionnaire for men and women from four regions of Russia. (1) Moscow, (2) Tatarstan, (3) Rostov oblast, (4) Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

The data of a cross-cultural study in 23 countries of the world [5] also showed a significantly higher self-image on all three scales of empathy in women compared to men. The maximum ratings on the decentration scale were obtained for the United States, Brazil, Italy, and Croatia; on the empathic concern scale during the lockdown of the first wave of the pandemic, for the United States, Brazil, Hungary, Italy, and Indonesia; and on the empathic distress scale, for Brazil, Turkey, Italy, and Indonesia.

THE ROLE OF CULTURE AND MORAL ATTITUDES IN OVERCOMING THE NEGATIVE CONSEQUENCES OF THE PANDEMIC AT THE PSYCHOLOGICAL LEVEL

Cultural dimensions, particularly those assessed on the scales of individualism‒collectivism and power distance (the index describes the presence of a social hierarchy and its impact on the interaction between people and on the functioning of social institutions) [8], as well as on the “tightness‒looseness” scale of Gelfand [9], have had a significant impact on the psychological state of people during the pandemic. A 23-country project [3, 5] showed that respondents from countries with a high level of individualism were the most anxious (Canada, Italy). On the contrary, collectivist countries (Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria) showed significantly lower levels of anxiety during the first wave of COVID-19. Respondents from highly “loose” countries (Canada, Italy) reported severe symptoms of anxiety, in contrast to survey participants from “tighter” countries (Indonesia, Jordan, Nigeria).

Countries that are characterized by a high level of individualism (Italy, the United States, Hungary) received the highest scores on the scales of empathic decentration and empathic concern, which distinguishes them from collectivist countries (Malaysia, Tanzania, Jordan, Brazil). Collectivist Turkey demonstrated the maximum level of empathic distress. Countries with high power distance scores (Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Russia, Belarus) showed relatively lower levels of empathic decentration and empathic concern compared to countries with lower power distance (Canada, the United States, Hungary, Italy).

Another area-wide study, conducted by American researchers in the 50 US states, as well as data from a cross-cultural study covering 67 countries, also point to the important role of cultural factors, measured on the “collectivism‒selfishness” scale, in accepting or resisting government measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic [10].

THE REACTION OF RUSSIAN SOCIETY: A MODEL OF PUBLIC FEARS

To assess the state of public relations during the pandemic in October‒November 2021, when there was an unprecedented increase in the number of cases, we conducted a survey of experts in more than 40 regions of Russia, including all federal districts. The number of interviewed experts amounted to more than 1200 and included scientists and representatives of regional and local authorities and public and religious organizations in equal proportion. To comply with research ethics, we deliberately did not interview medical workers. The research tools were based on a single questionnaire for all regions developed by the RAS Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology and the Ethnological Monitoring Network. The questionnaire provided not only a choice of standard answer options but also the opportunity for the respondents to express their opinion on each question in a free form.

The questions addressed to the experts concerned the presence or absence of fears, apprehensions, and prejudices associated with the epidemic among the residents of the respective Russian regions. Opinions were asked about the impact of the mass media and social networks, as well as political parties and public and religious organizations, on public sentiment in the context of the pandemic. The problems of well-being and employment of the residents of the regions under survey and their fears about rising prices and loss of jobs were also touched upon. The risks of social conflicts provoked by protest activity and the changing attitude of the local population towards labor migrants were also discussed. Note that, at the design stage of this study, an interesting fact came to light: it turned out that it was easier to obtain a more adequate picture of Covid-associated social phobias not from population surveys but proceeding from a sociological generalization of the experts’ opinions since, owing to their professional and official positions, they regularly encounter public reactions to the pandemic.

The experts assessed the composition and spread of fears caused by the pandemic in society. The presence and a wide spread of such phobias were reported by 79.3% of the experts; 12.3% said that they were absent, and 8.3% were undecided. In all Russian regions surveyed, the most massive was the fear of contracting the coronavirus. This conclusion is confirmed by the data of the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM): in 2021, 60% of adult Russians experienced fears of contracting the coronavirus, and during the surge in incidence in October and November, these fears became even stronger. Only a very small share of the population was not concerned about the danger of catching the virus, and those who denied the existence of the virus as such were extremely few.

Anxiety about coronavirus infection decreased during the summer periods, when many people went on vacation. Then the fears returned, especially intensified under the influence of information about the emergence of new strains, as well as measures to ban movement and social contacts introduced by governments of different countries and regions.

Against the background of total fears, the behavioral reaction of Russians, as well as residents of other countries, turned out to be extremely contradictory. On the one hand, the territorial mobility of the population was declining; in particular, the number of trips over long distances was reduced, but not only due to targeted restrictions on the part of regional authorities but also because of the unwillingness of people themselves to make regular trips. At the same time, there was no decrease in the number of those wishing to make episodic trips to another region and other countries for recreation. Significant turnover of domestic tourism, as well as the stability of foreign tours, was confirmed by official statistics. During 2021, Turkish Antalya alone was visited by more than 3.5 million Russians, that is, several percent of the Russian population. In 2020, during the nationwide lockdown in spring, the number of tourist trips abroad decreased several times, but at the end of the year it amounted to an impressive figure, 12.4 million. In 2021, the decrease in the number of foreign trips was insignificant, if any.

Despite reports of the bankruptcy of travel companies, this form of economic activity remained in great demand; in the Russian tourist industry, as before, more than one million people were employed at the height of the pandemic, without considering small businesses. Paradoxically, it is the desire to make tourist trips, which objectively contribute to the spread of coronavirus, that stimulates many Russians to vaccinate themselves. Thus, on the one hand, tourism activity is fraught with epidemic threats, while on the other, it serves as a conductor of preventive measures and strengthens public ideas about socially responsible behavior.

Nevertheless, it should be recognized that patterns of responsible behavior have not become a social norm. Not only skeptics (obviously, a minority) but also those who were concerned about the danger of the epidemic often indulged in traveling and many other forms of the prepandamic lifestyle; they continued frequent contacts with others, did not use masks, and did not observe other sanitary and hygienic requirements. Fearing illness, people at the same time did not want to change their habitual way of life. It is generally assumed that young people ignored preventive restrictions more than others. However, the study showed that representatives of the middle-aged cohorts often showed irresponsibility. The exception was the elderly, who tried to follow the preventive rules. It can be concluded that the personal interests of the majority of the population opposed not only antiepidemic requirements but also personal phobias. This paradoxical contradiction in a number of cases has become a source of mass neuroticism, social tension, and sporadic manifestations of aggression.

The model of social fears generated by the pandemic is not just a conglomeration of highly contradictory beliefs but also their clear subordination. As was already mentioned, the fear of contracting the infection dominates in the public consciousness. It is often the case that the lower the incidence in a particular region, the stronger such fears are. This is especially true for small regional communities in the provinces, where access to medical care is difficult.

However, the availability of medical institutions does not alleviate fears, although of a slightly different kind. Phobias related to medicine were in second place in terms of frequency. Public confidence in medicine declined especially noticeably in the first months and during periods when the epidemic somewhat weakened. Therefore, people bought various drugs, sometimes for a lot of money, to help themselves on their own. Not only in provincial towns and rural areas but also in large agglomerations, rumors circulated that, as the epidemic intensified, medical care would be unavailable. The topic of vaccination became the most discussed, and here the average Russian nonprofessional was not much different from that from France, England, the Netherlands, and other countries. Opposite opinions were in circulation, fears of the type “if we do not vaccinate, we will all die” arose. At first, they were moderate, almost nowhere did they reach a panic level, but they intensified as it became clear that the epidemic could become a constant companion of humankind, that more and more dangerous strains would appear.

However, phobias about the dangers of the vaccine itself were spreading even more intensively. In the regions of the Far North, these fears manifested themselves in a bizarre way: instead of vaccination, people sought self-isolation. In the remote uluses of Yakutia, residents who previously had advocated for more frequent visits by helicopter teams of doctors now did not want to see them. In Kamchatka, during the population census, which coincided with the pandemic, people tried to register as quickly as possible and go to a remote area for traditional crafts, “where there are no other people and no infection.”

In the formation of antivaccination sentiment, one can, of course, see the intent associated with unfair competition in the international vaccine market. However, one cannot deny the public susceptibility to antivaccine propaganda. Since the second half of 2021, when an active vaccination campaign began in Russia, many have been vaccinated not of their own free will but to receive a vaccination certificate, often under pressure from their employers. Not trusting medicines, as some interviewed experts reported, “municipalities’ employees and public servants applied for a fictitious vaccination, simply buying a certificate.” Surprisingly, when the infection rate began to rise rapidly after the summer holidays, antivaccine sentiment also intensified. A significant part of the population began to fear vaccination more than the danger of becoming infected. The experts explained this phenomenon by insufficient education of various groups of the population. Yet the broad “awareness” of people, obviously, also played a negative role. Recall that, by the time the vaccines were widely introduced, the epidemic had lasted for almost two years and many people had directly encountered the disease. Those who had had a mild case, as well as those who had been in contact with the sick without being infected, believed that the disease would no longer threaten them. Disbelief in the danger of the coronavirus was also facilitated by media reports that the new infection would soon turn into a common seasonal disease.

Opponents of vaccination are obsessed with various prejudices, which sometimes outweigh fears of contracting coronavirus infection. Rumors circulated on the Internet that, they say, “vaccination will worsen immunity.” However, this is a mild form of antivaccination. More radical ideas were also spread: the anti-COVID vaccine allegedly poses a threat to health, it “can infect one” with the same coronavirus, “cause other diseases,” or “provoke not only complications but also death.” Rumors circulated in Dagestan that imminent death would come two years after vaccination. A negative role was played not only by rumors but also by some electronic media, which reported on the alleged general resistance to the vaccination campaign on the part of residents of certain Russian regions. There are domestic and foreign studies that shed light on the technologies used to impose the load of excessive and false information on the population in the context of global risks to achieve political and military goals [11]. Conspiracy “theories” were also spread, not only about the allegedly intentional restriction of childbearing through the vaccine but also about its impact on human genetics. Vaccination was endowed with eschatological properties; some tried to assert that “it is evil in itself” and “a harbinger of the end of the world.”

Some of the experts interviewed see the cause of vaccine phobias in Russia’s overly liberal immunization policy. In their opinion, the state should carry out vaccination on a directive basis, as it was in the Soviet years, and not exaggerate the topic of voluntariness.

THE PROBLEM OF DENIAL AND LIMITATIONS OF THE HABITUAL LIFESTYLE

Despite the easily accessible data on the spread of the epidemic in Russia and abroad, even at the peak of the incidence, when statistics was unnecessary to verify the scale of the disaster, some people continued to deny the very existence of the epidemic. Some nihilists sought to convince others that there was no coronavirus at all; others, that there was no epidemic; and still others, that you could protect yourself from the disease if you did not listen to doctors. It was on this wave that enterprising bloggers, healers of all sorts, political and social activists, religious figures, and representatives of show business were reaping the fruits of public attention and making money. Political criticism of Russia was also linked to the denial of the danger of COVID-19 and doubts about the effectiveness and safety of the Russian vaccine.

Some of the experts interviewed specified that such nihilism was due to the general decline in the level of education in the country. This can be considered true, but only in part since the denial of the epidemic and the vaccine was also found among people with higher education, as well as among some medical workers. The problem of denial turned out to be complex because its adherents represented different segments of the population and different cultural and religious communities. Also note the influence of the religious factor, which, in particular, manifested itself in the mass denial of the danger of the pandemic in the North Caucasian regions.

The problem of the public denial of the epidemic and opposition to preventive measures leads to something more than just the need to overcome specific prejudices. An eclectic and seemingly unsystematic cloud of social phobias manifested itself at different stages of the epidemic as a surprisingly stable social phenomenon, quickly and resourcefully generating “contras” against watertight “pros.” It would seem that the dissemination of official information on the number of cases and Covid-caused deaths was bound to convince the population of the need for preventive measures. Yet such information, however widely known it was, did not have a decisive impact on people, which is confirmed by official figures of a slow increase in the number of the vaccinated. TV reports from the so-called red zones of intensive care units in hospitals, stories of doctors and patients about the danger of the disease, and active public service announcements under the slogan “Get vaccinated!” were supposed to shake public prejudices. However, sometimes they did not work.

This study has shown that, in the conglomerate of epidemic phobias, an integral and significant part falls on phobias of a sociocultural nature; they form the basis of motivation to maintain the habitual way of life. Their presence to a certain extent explains the irrationality of the actions and judgments of representatives of various strata of society. The fact is that the epidemic and the related regulatory measures have disrupted the daily routine of almost every person, generated many prescriptions and restrictions, and narrowed everyday contacts. According to the experts interviewed, it is the likelihood of disunity that the population sees as one of the strongest threats. People have become afraid of another quarantine not only because of the possible loss of livelihood but also because of the loss of ties with others, although many residents actively use electronic means of communication even in small Russian towns and villages.

The epidemic has shown in practice that electronic communication cannot replace live communication. Moreover, it has turned out that not only older people are afraid of disunity but also young people who actively use computer networks. Many opposed the full transition to the new mode of communication during epidemic lockdowns; students spoke out against distance learning and interaction with teachers and fellow students in a purely electronic format. Teachers also reacted with hostility to the requirements of university administrations to observe the antiepidemic regime in classrooms and dormitories. Naturally, conjectures emerged that after the online methods have been tested, “live” learning would allegedly disappear altogether.

This study has shown that prejudices and propaganda aimed at accusing the authorities of “useless,” “weak,” and even “malicious” actions are a particular problem. Distrust of the authorities is based on various grounds, often not related to the epidemic itself, but in everyday consciousness it is linked with it. According to one of the experts, “people like to scold the government and any of its actions,” and this philistine property inevitably manifests itself during such a global disaster as the coronavirus infection. Often the topic of the epidemic is just a pretext for claims and accusations.

However, surveys of experts in various Russian regions have revealed that antigovernment phobias are mostly moderate: for example, that during the epidemic people were allegedly left to their own devices, that the authorities do not want to deal seriously with the problem, that there are no real actions to regulate the situation, that alternative vaccines are not available, and that the authorities do not control the situation and are powerless. It is noteworthy that such phobias irrationally remain stable, although state support measures are widely known: the free for the population and unprecedented increase in the volume and pace of medical infrastructure, various means of protection against the epidemic, the expansion of social payments to various categories of citizens, the implementation of state assistance to the most vulnerable regions, introduction of measures to support the economy and private business, etc. The experts interviewed draw attention to the fact that, with an abundance of the mass media, many people tend to use unverified information about the epidemic and show no interest in official sources. Obviously, in addition to the official ones, it is necessary to use informal channels of informing the population.

More severe phobias in relation to the authorities are less widespread. However, attention should be paid to their concentration in some regions, for example, in the republics of the North Caucasus and large metropolitan areas of the country, where myths were propagating that the pandemic was a kind of maneuver to distract citizens from more serious problems of the country. Due to provocations through social networks, the epidemic was linked to the state policy of digitalization, which, as is sometimes claimed, seeks total control over the population.

In connection with the periodically imposed restrictions on access to public places, rumors spread about discrimination against entire social groups, including the elderly, as well as speculation about passes, Covid passports, vaccination certificates, and QR codes, in which critics saw not restrictive measures but methods of spying on the lives of citizens. There was the opinion that, as a result of the epidemic, “the state controls the people more and more” and “authoritarian tendencies in power” would inevitably strengthen. The topic of infringement of the rights and freedoms of unvaccinated people was promoted, and fears were circulating that epidemic discrimination would become real in hiring and moving up the career ladder.

The epidemic intensified rumors about a reduction in income, the deterioration of working conditions, and the loss of jobs. VTsIOM polls revealed that Russians’ anxiety about a decrease in income in 2021 grew, especially in the second half of the year, in October and November, when 45–48% of the respondents stated such fears [12]. According to a study carried out in the same year by the RAS Federal Center of Theoretical and Applied Sociology, the expenses of Russians were forced to increase, “every fifth respondent stating that he/she had to spend most of his/her savings over the past year” [13, p. 742].

The experts we interviewed also pointed out that the fear of being left without a livelihood due to inflation had affected various strata, primarily pensioners. From the first months of the pandemic, rumors spread about the upcoming rise in prices and a shortage of essential goods, including medicines, and when quarantine measures were introduced, people began to fear that employers, using the situation, would cut employee benefits to their advantage, that paid working hours would also be reduced, and that jobs would be cut. Fear of unemployment, loss of income, the need for expensive treatment, financial problems, and the inability to pay utility bills became rather common phobias during the pandemic.

The experts interviewed assessed the impact of the epidemic on migration activity, employment, and the level of well-being of the population in their regions. Most of them saw primarily negative effects, but some also pointed to positive trends, such as positively changing attitudes of local residents towards migrants. Some experts noted the emergence of positive changes in the field of employment, in particular, the possibility of switching to flexible working hours.

PUBLIC ACTIVITY DURING THE PANDEMIC

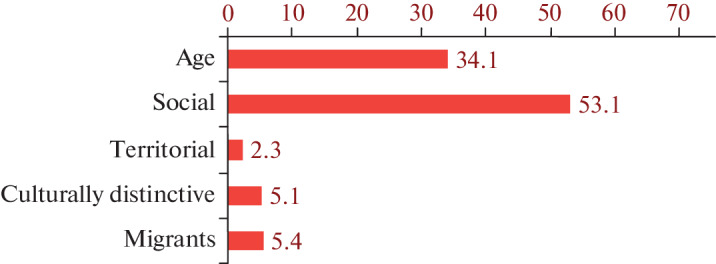

The experts assessed protest activity in connection with the epidemic as moderate. Also note that in November 2021, VTsIOM recorded an aggravation of the protest potential, when up to a quarter of the respondents indicated the possibility of protests in their places of residence, and a fifth reported their personal readiness to take part in such actions [14]. Within our study, half of the experts surveyed did not see such activity in their regions at all. Others stated that such activity did exist, shown primarily by people in certain forms of employment who found themselves in the most vulnerable position (Fig. 3). Experts pointed to the unvaccinated as a category of protesters, as well as to medical personnel, whose representatives demanded compensation for work under the pandemic. According to the respondents, there were many dissatisfied people among representatives of small and medium-sized businesses in the service sector and nonfood trade. In a number of regions, individual entrepreneurs had to wind down their activities. Although the protests are mostly online, there are examples of open action. In the spring of 2020, during the lockdown in North Ossetia, protesters demanded the lifting of the self-isolation regime; several people accused of rioting were convicted.

Fig. 3.

Population groups with increased protest activity during the pandemic, % of surveyed experts who noted the presence of protest activity.

According to the experts, representatives of different age groups, both pensioners and young people, are experiencing stress under the yoke of the epidemic. Accidental conflicts occur in public places—in shops, on transport, in universities, and in large and small cities. According to one observation, in Dagestan, the police “fined everyone” for violating the mask regime, “people are embittered” and wear a mask just to avoid getting a fine and not to protect themselves from the virus. Protest activity in an open form was mainly shown by young people and the unemployed, while the bulk of the dissatisfied limited themselves to complaints to authorities, anonymous discussions of the situation on social networks, and private communication. In second place in terms of the level of protest activity are the parents of schoolchildren, who made claims against the administrations of educational institutions and local authorities due to changed forms of education and a decrease in its quality.

The experts pointed to the dissatisfaction of labor migrants, who were forbidden to come to work. The experts also included shift workers who go to work in the eastern and northern regions of the country from other Russian regions in potentially conflict categories in connection with the restriction of movement. According to the experts, the epidemic had no obvious impact on interethnic and religious relations. At the same time, destructive activity in social networks has increased markedly during the pandemic.

The duration of the epidemic has given rise to people’s anxiety about the future—their own, their family, region, country, and even the world as a whole. It is, one might say, a new social phenomenon. Mass anxiety is dictated by the fear of uncertainty—what tomorrow will be like and what will happen in a year or two. Although people have got somewhat used to the epidemic, there are still widespread fears like “what if it is forever” and “we will never return to our old life.” Opinions are circulating that “the pandemic will continue for many years,” “distance learning and work will become mainstream,” and “life will move online.” People are concerned about the health and future of their children. The feeling of insecurity convinces them that it is impossible to make long-term plans. The coverage of the population with fears of the future is a serious social challenge for society and the state. Previously, pessimism was about current difficulties, and the future inspired optimism, while now it is the future that often seems a vague threat.

The experts interviewed lay the blame for mass phobias primarily on social networks and the mass media (44.3%). They described the activities of the federal and local media as a source of aggravating the situation, creating a negative background, and increasing the level of anxiety. Social psychologist Nestik called the modern media a “factory of anxiety” [15]. The activity of the blogosphere was defined by some of the experts interviewed as “an instrument for the formation of distrust of the authorities and the state.”

The respondents negatively assessed the activities of some political parties (14.8%) and religious organizations (9.8%), indicating that they had become a source of antivaccination sentiments and antiscientific ideas about the pandemic and worsened the situation with their meetings, especially in the first epidemic year. At the same time, the activities of political parties and religious organizations during the acute phase of the pandemic were seen by the mass audience as weakly positive. The experts emphasized that, in their regions, it was the major Russian confessions, primarily the Orthodox and Muslim communities, who began to call on their parishioners for vaccination and explained things. Volunteer organizations showed creative activity, proactively providing assistance to the population, especially to the elderly and large families.

THE ROLE OF NATION-STATES UNDER THE PANDEMIC

Our position is that, despite the talk of the crisis of nation-states and their replacement by civilizations or world governments, there is no more significant and all-encompassing social coalition of people on the horizon of the evolution of human communities than nation-states, understood as communities of citizens under one sovereign authority, having a common identity based on a common historical, social, and cultural experience, regardless of race, ethnicity, and religious affiliation. Russia, for all its historical originality and cultural complexity of the civil Russian nation, is one of the largest nations of the world and has certain common patterns in the organization and existence of modern states [16]. The pandemic once again and very vividly shows that it is the states that provide the most important existential needs and rights of modern man—from territorial‒resource and organizational‒economic life support to the organization and maintenance of social institutions, the legal norms of the community, education, enlightenment, and cultivation of the population through state-supported systems.

States provide civil solidarity, prevent conflicts and violence, and protect against external threats and global challenges. Moreover, in the context of such global cataclysms as the coronavirus pandemic, discussions about the crisis and disappearance of nation-states appear naive and self-destructive. According to the British anthropologist Gellner [17, p. 270],

The events of 2020 are a powerful demonstration that the decline of the nation-state in the age of hyper-globalization or ‘overheating’ has … been greatly exaggerated. Throughout the world (with interesting local contrasts in North America, East Asia, Scandinavia, and South Asia) a massive cross-national social-science experiment is being carried out in real time as different strategies are adopted by neighboring countries.

According to the scientist, “we are living through a radical turning point. In the face of an existential threat, the old gods of neoliberalism are being thrown on a bonfire.” Ignoring the laws of the market, which, it was believed, should govern everything and everyone, it is the states that take the main responsibility. In Britain, for example, £15 bln was allocated at a stroke to solve the problems of COVID-19 [17, pp. 270, 271].

Little can be added to this conclusion other than hundreds of similar examples illustrating the increased role of the state during the pandemic, including in Russia. Nevertheless, the main trends and forms of the regulatory influence of the Russian state during this period deserve at least a brief enumeration.

The reaction of the top leadership, including the President and the Head of the Government of the Russian Federation, was quite timely, open, and meaningful, although the details of informing the population were delegated to relevant members of the government. The Coordinating Council under the Russian Government to combat the spread of coronavirus infection on the territory of Russia was established in a timely manner. At the same time, the federal subjects were authorized to determine independently the sanitary and epidemic regime for the population of the region and other measures to combat the pandemic. The main efforts and financial resources were directed to the field of medicine, including the development and production of vaccines and medicines and the deployment of a large-scale hospitalization program and other forms of medical care for the population. Several hundred billion rubles were spent on the construction or conversion of hospitals and clinics, and the capabilities of the military department were involved in this work. The government allocated more than ₽7.3 billion to the regions to support polyclinics, about ₽100 billion for Covid hospitals, and more than ₽200 billion for targeted social payments to medical workers. Funds were allocated to purchase medical supplies, as well as for free medicines for patients with coronavirus. Then came into action a program of free rehabilitation of patients with this disease. Add also financial and other support for scientific institutions engaged in the study of coronavirus strains and the production of vaccines. Finally, a campaign of free vaccination of the population was organized throughout the country, as well as testing, including on a commercial basis. Industrial structures ensured the production and delivery of equipment and oxygen concentrators to the regions.

On January 18, 2020, a mass vaccination campaign against COVID-19 started. At the beginning of 2022, about 120 million citizens were vaccinated in the country. In general, in accordance with international standards, state-supported Russian medicine and science have successfully coped with the challenges of the pandemic, as evidenced by the dynamics of morbidity, recovery, and mortality from Covid and its consequences.

Large-scale efforts were made by the state in the field of the economy and ensuring the vital needs of the country’s population, overcoming the crisis, and minimizing the damage from epidemic restrictions, reduction in population mobility, closure of a number of enterprises, etc. We primarily mean tax incentives, support for the poor, a moratorium on the payment of loans and subsidies, exemption from customs duties, and many other actions in the field of regulating economic activity, employment, and trade. The total amount of resources allocated for the needs of health care and the economy is estimated at trillions of rubles, to say nothing of the funds and efforts that were spent by business structures and civil society institutions (religious and public organizations, volunteer groups, support funds, etc.).

Only the state managed to take measures to ensure public safety and counter the pandemic in terms of international regulation to provide a barrier to infection from abroad. This concerned restrictions on international communication and special regulation of foreign tourism. The state has implemented a number of important measures in the field of social life, education, and culture, including free urgent telephone communication, correspondence forms of meetings, distance learning in schools and universities, preferential gadget software, a new service on public service portals, and much more. Almost ₽30 billion was allocated to support federal cultural institutions, as well as educational, scientific, and medical institutions.

All the above allows us to re-evaluate the place and role of the modern state in the life of the country and the world as a whole. The well-known political scientist A. Lieven wrote about the return of nation-states to the world stage against the backdrop of global crises, as well as crises of interstate and bloc formations, about their tough upholding of national interests and sovereignty, and about the return of nationalism in its civil-state form. He emphasized the importance of social motivations and mobilization based on the ideas of the nation, which ensure the success of modern states. According to him, the greatest source and guarantee of the strength of the state is neither the economy nor the size of the armed forces but legitimacy in the eyes of the population and universal recognition of the moral and legal right of the state to power, on the execution of its laws and regulations, on the ability to call on the people to sacrifice, be it taxes or, if necessary, military service. A state without legitimacy is doomed to weakness and collapse; or else it will have to resort to cruelty and establish rule based on fear [18].

The Russian state, with its developed and multifunctional healthcare system and fundamental scientific research, which is able to “discipline” the population, that is, to pursue a policy of persuasion, directly or indirectly prescribing the behavior of institutions and citizens, has generally proved itself capable of overcoming such a formidable attack as a pandemic. As one of the researchers of this topic noted, “the system of measures taken by the state during the pandemic and the strict control over their observance convinced the majority of the population of the advantages of centralized administrative power, historically traditional for the Russian political system.” We can agree with her general conclusion that “only a strong state based on the unity of the people and state power, the activities of which are focused on social trust, providing conditions for human development, can solve the problems caused by the pandemic” [19].

* * *

The results of several of our studies in the framework of sociocultural anthropology made it possible to assess the psychological state of the Russian population against the backdrop of the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, as well as the role of cultural factors in overcoming stress in the face of the restrictions and challenges using the example of 23 countries of the world. The data obtained indicate that demographic components, including gender, age, and marital status, as well as personality traits, play an extremely important role in the individual choice of behavioral strategies in these conditions. Individual mobility and readiness to be in self-isolation depended significantly on gender and the level of individual anxiety during the lockdown of the first wave of coronavirus. Women reported higher levels of anxiety than men, and their distances from home were significantly shorter. Gender differences were also traced in relation to the factor that causes the greatest fear. Women saw the main danger for themselves and their loved ones in the infection itself, while men were focused on economic and financial challenges (fear of losing a job, reduced earnings, limited opportunities to conduct and expand a business).

Equally important are our conclusions regarding public reactions and behavioral norms that have become widespread among Russians, as well as a kind of model of public fears and phobias, which were formed not only due to the insufficient level of education of the population but also under the influence of the extreme heterogeneity of the modern media, including social networks and distributors of various conspiracy theories and esoteric views that contribute to the emergence of panic. This study has revealed the adherence of our compatriots to the usual way of life, the fear of radical changes, the uncertainty of the future, the collapse of social security, and other forms of collective and personal fears.

Among public reactions, protest manifestations were of a moderate nature, but forms of collective solidarity were active, especially in the field of medicine and volunteer activity. Religious and public organizations showed themselves positively; political parties, noticeably less positively; and the mass media had a negative impact on the situation.

During the pandemic, the state showed itself as the key institution of public mobilization, as the only legitimate form of organization and coercion in emergency conditions. It was the experience of state institutions and the resources of the state that allowed Russia and other sovereign states to counteract the coronavirus pandemic effectively without interrupting the solution of pressing social and economic tasks.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

RAS Academician Valerii Aleksandrovich Tishkov is Academician-Secretary of the RAS Department of Historical and Philological Sciences and Director for Science of the Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, RAS (RAS IEA). RAS Corresponding Member Marina L’vovna Butovskaya is Head of the IEA Center for Cross-Cultural Psychology and Human Ethology. Valerii Vladimirovich Stepanov, Cand. Sci. (Hist.), is a Leading Researcher at the same institute.

Translated by B. Alekseev

Contributor Information

V. A. Tishkov, Email: valerytishkov@mail.ru

M. L. Butovskaya, Email: marina.butovskaya@gmail.com

V. V. Stepanov, Email: eawarn@mail.ru

REFERENCES

- 1.V. N. Burkova, M. L. Butovskaya, Yu. N. Fedenok, et al., “Anxiety and aggression during COVID-19: The case of four regions of Russia,” Sibir. Ist. Issled. (2022) (in press).

- 2.Spitzer R. L., Kroenke K., Williams J. B., Löwe D. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Int. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkova V. N., Butovskaya M. L., Randall A. K. Predictors of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic from a global perspective: Data from 23 countries. Sustainability. 2021;13:1–23. doi: 10.3390/su13074017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butovskaya M. L., Burkova V. N. Anthropology and Ethnology: A Modern View. Moscow: Polit. Entsiklopediya; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butovskaya M. L., Burkova V. N., Randall A. K. Cross-cultural perspectives on the role of empathy during COVID-19’s first wave. Sustainability. 2021;13:1–35. doi: 10.3390/su13137431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. H. Davis, “A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy,” JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol., No. 10, 85 (1980).

- 7.N. A. Budagovskaya, S. V. Dubrovskaya, and T. D. Karyagina, “Adaptation of the M. Davis multifactorial empathy questionnaire,” Konsul’tativnaya Psikhol. Psikhoter., No. 1, 202–227 (2013).

- 8.Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfand M. J., Raver J. L., Nishii L. Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science. 2011;332:1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. G. Lu, P. Jin, and A. S. English, “Collectivism predicts mask use during COVID-19,” Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118 (23), e2021793118 (2021). 10.1073/pnas.2021793118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.E. A. Mikheev and T. A. Nestik, “Psychological mechanisms of infodemic and personal attitude to disinformation about COVID-19 in social networks,” Sots. Ekon. Psikhol., No. 1, 37–64 (2021).

- 12.VTSIOM: Index of fears. https://wciom.ru/ratings/indeks-strakhov

- 13.M. K. Gorshkov and I. O. Tyurina, “State and dynamics of mass consciousness and behavioral practices of Russians in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Vestn. RUDN, Ser. Sotsiol., No. 4, 739–754 (2021).

- 14.VTsIOM: Protest potential. https://wciom.ru/ratings/protestnyi-potencial

- 15.T. A. Nestik, “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on society: A sociopsychological analysis,” Sots. Ekon. Psikhol., No. 2, 47–83 (2020).

- 16.Tishkov V. A. National Idea of Russia: The Russian People and Their Identity. Moscow: AST; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gellner D. N. The nation-state, class, digital divides, and social anthropology. Soc. Anthropol. 2020;28:270–271. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A. Lieven, “Progressive nationalism: Why national motivation is needed for the development of reforms,” Russ. Glob. Aff., No. 5, 25–42 (2020).

- 19.O. D. Garanina, “Russian realities in the context of the pandemic,” Kronos: Obshchestv. Nauki, No. 1, 28–31 (2021).