Keywords: androgen, autonomic balance, chronic stress, estrogen, glucocorticoid

Abstract

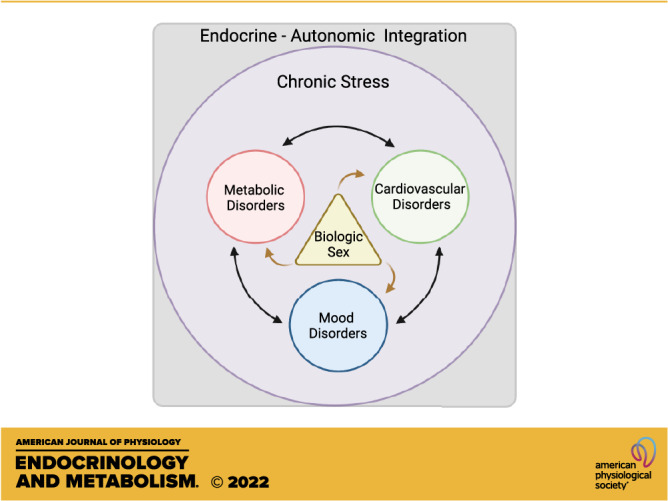

Chronic stress is a significant risk factor for negative health outcomes. Furthermore, imbalance of autonomic nervous system control leads to dysregulation of physiological responses to stress and contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic and psychiatric disorders. However, research on autonomic stress responses has historically focused on males, despite evidence that females are disproportionality affected by stress-related disorders. Accordingly, this mini-review focuses on the influence of biological sex on autonomic responses to stress in humans and rodent models. The reviewed literature points to sex differences in the consequences of chronic stress, including cardiovascular and metabolic disease. We also explore basic rodent studies of sex-specific autonomic responses to stress with a focus on sex hormones and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation of cardiovascular and metabolic physiology. Ultimately, emerging evidence of sex differences in autonomic-endocrine integration highlights the importance of sex-specific studies to understand and treat cardiometabolic dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic stress exposure is increasingly prevalent in modern society. Whether interpersonal, economic/occupational, sociocultural, environmental, or a combination of these, stress is a fundamental part of daily life for many people. Subsequently, chronic stress is a significant contributor to cardiometabolic and psychiatric disorders including the global leading causes of death, cardiovascular disease (1, 2), and years lived with disability, depression (3). Although the detrimental effects of stress are well documented, the majority of physiological studies have been conducted in males. Emerging evidence indicates that females respond to stress differently (4); therefore, this review focuses on the current understanding of how sex impacts stress-related physiological outcomes.

Stress can be operationally defined as a stimulus that signals real or perceived challenges to homeostasis or well-being (5), resulting in both neural and physiological responses (6). Exposure to acute stress initiates a homeostatic response that promotes adaptation (5, 7). However, chronic stress, defined as long-term exposure to real or perceived threats leading to repeated activation of physiological systems, can tax adaptive capacity (8, 9). Although chronic exposure to stressors and subsequent allostatic load have increased in society (10), certain populations are impacted to a greater extent than others. In particular, socioeconomic disadvantage associates with increased perceived stress (11, 12), higher allostatic load (13), flattened diurnal cortisol profiles (14), inflammation (15), changes in DNA methylation (16), and, consequently, increased risk of psychiatric (17), cardiovascular (18, 19), and metabolic disease (20).

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by a set of clinical signs including insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, abdominal obesity, and hypertension that creates predispositions for type two diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (21). Although the development of metabolic disease is multifactorial, stress is widely recognized as a causative agent (22). Specifically, chronic stress positively correlates with the development of metabolic syndrome in both children (20, 23) and adults (24). Similarly, chronic stress worsens the progression of cardiovascular disease (25).

Cardiometabolic disorders are frequently comorbid with mood disorders (3). In addition, the reciprocal relationship between cardiometabolic and depressive disorders further contributes to years lived with disability (3, 26). Although depressive disorders are also complex and multifactorial, chronic stress commonly exacerbates mood symptoms (27). In addition, depression has inflammatory and immunomodulatory components related to increased cortisol (28, 29). Importantly, mood and cardiometabolic comorbidity disproportionately affect females (30). However, basic physiological investigations into the consequences of chronic stress have only recently taken female subjects into account.

AUTONOMIC AND ENDOCRINE STRESS RESPONSES

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) modulates the physiology of organ systems to maintain homeostasis through the integration of sympathetic norepinephrine and vagal parasympathetic acetylcholine signaling (31). In response to stressors, the ANS prepares the body to respond to real or perceived threats. The prototypical acute stress response is characterized by rapid activation of the sympathetic nervous system to prime the body for action, resulting in a wide range of physiological changes including epinephrine and norepinephrine release, increased heart rate and respiration, glucose mobilization, peripheral vasodilation, and visceral vasoconstriction (32).

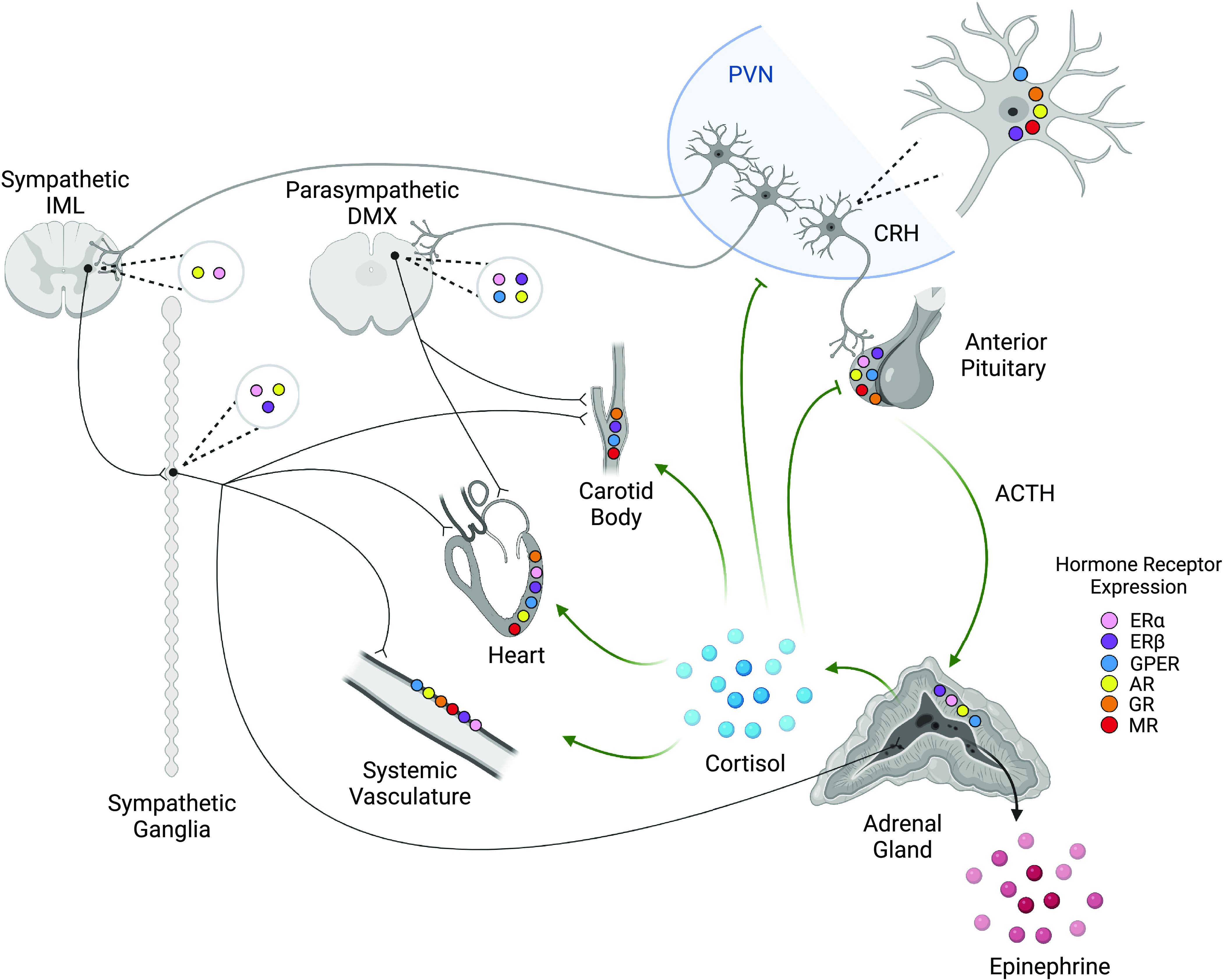

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis aids in homeostatic regulation of stress responses over a longer timeframe through the release of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rats and mice) from the adrenal cortex (9). Broadly, glucocorticoids increase gluconeogenesis and lipolysis, promoting catabolic energy mobilization (5). The HPA axis response is initiated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons in the paraventricular hypothalamus. CRH then acts on the anterior pituitary to cause the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates synthesis and release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex into systemic circulation. Glucocorticoids then bind mineralocorticoid (MR) and glucocorticoid receptors (GR) to inhibit further release of CRH via negative feedback. Furthermore, HPA axis activity is regulated through multiple mechanisms including descending neural inputs (33), the recruitment and synchronicity of CRH neurons during acute stress (34), and rhythmicity on both ultradian and circadian timescales (35). Importantly, acute autonomic and endocrine stress responses dynamically interact to integrate physiological states and promote adaptation.

In contrast to adaptive acute stress responses, chronic stress produces different physiological outcomes, both autonomically and hormonally. Chronic stress leads to prolonged sympathetic stimulation, vagal withdrawal, and subsequent autonomic imbalance. Dysregulation of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance results in cardiovascular changes including baroreflex blunting (36), reduced heart rate variability (37), decreased blood pressure variability (38), and diminished neurovascular coupling (39). Importantly, chronic stress-induced autonomic imbalance is impacted by hormonal signaling. For example, inhibition of CRH receptors 1 and 2 in the limbic bed nucleus of the stria terminalis increases arterial pressure and impairs baroreflex (40). Chronic stress also leads to prolonged HPA axis activation, which can manifest in adrenal hyperplasia and hypertrophy, suggesting greater cumulative exposure to glucocorticoids and epinephrine (41). Although chronic stress disrupts glucocorticoid rhythmicity, multiple studies have reported differing effects on diurnal cortisol profiles. A flattening of diurnal cortisol curves is common (42); however, a study of chronic stress in adolescents found that those with the highest genetic risk for HPA axis-linked disease, such as mood disorders, had a pattern of lower morning cortisol coupled with a flatter diurnal curve. Those with lower genetic risk had elevated morning cortisol and a steep diurnal curve. Ultimately, these variable outcomes indicate a genetic component to the consequences of chronic stress (43).

GONADAL HORMONES: ESTROGENS AND PROGESTERONE

Historically, rodent stress research has focused largely on male subjects or has not considered the effect of sex on physiological outcomes. Therefore, sex-dependent autonomic regulation during chronic stress is an emerging area for understanding sex differences in disease incidence, as well as potential clinical targets. Although the rate of metabolic syndrome is similar in males and females (44), females are at greater risk for depressive disorders and cardiovascular disease has a higher female prevalence after menopause (45, 46). In addition to cardiovascular disease being the primary cause of death in women (47), women are at twice the risk for developing major depressive disorder (48). Underscoring these disease predilections are a number of uniquely female experiences including pregnancy, parturition, and conditions, like polycystic ovarian syndrome, that affect female reproductive physiology (30, 49).

Although female sex hormones, centrally estrogens and progesterone, are not unique to females, they are cyclically variable due to menstrual or estrous cycling and change with age. Evidence suggests that female-specific responses to stress are cycle phase-dependent with greater HPA axis reactivity in early proestrus, a period characterized by high estrogens and low progesterone (50). The effects of estrogens are primarily mediated by three estrogen receptors (ERs): ERα, ERβ, and g-protein-coupled ER (GPER). Although there are several estrogens that bind ERs, estradiol predominates in cycling females and estrone predominates following reproductive senescence (51). The production of estradiol primarily occurs through the aromatization of testosterone. Progesterone effects are mediated by intracellular and membrane-bound progesterone receptors (PRs) and GABAA receptors. Importantly, ERs and PRs are found throughout the body (Fig. 1) and have wide-reaching effects on most physiological systems (79–83). Generally, estrogens are thought to convey protective cardiometabolic effects in females (84–91), as well as males (92, 93). Although many of these effects are activational and life-stage dependent, there is also evidence of sex-dependent organizational effects of steroid hormones (94). Sex steroid receptors are also found in select cells throughout the brain and gonadal hormone action in the central nervous system is an ongoing field of study.

Figure 1.

Stress and gonadal hormone receptor expression across neuroendocrine and cardiovascular organs. Neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus initiate both autonomic and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responses to stress. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) acts on anterior pituitary corticotropes to cause the release of ACTH and the subsequent synthesis and release of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rats and mice) from the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoids have systemic action on cardiovascular responses and provide negative feedback on the PVN and anterior pituitary. PVN neurons also synapse in the sympathetic intermediolateral nucleus (IML) and the parasympathetic dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMX). Efferents of the DMX innervate both the carotid body and heart to influence cardiac and baroreflex activity but are generally not found in the systemic vasculature. Efferents of the IML act through sympathetic ganglia to stimulate cardiovascular activity and the release of epinephrine from the adrenal medulla, which acts systemically. In addition, stress and gonadal hormone receptors regulate activity in a tissue-dependent manner. It is important to note that receptor distribution has not been completely characterized and further study is warranted. Thus, the absence of reports on expression does not indicate that receptors are not present. CRH neurons express estrogen receptors β (ERβ), G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) (52), and androgen receptors (AR) (53), as well as glucocorticoid receptors (GR) (54) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) (55). Similarly, the anterior pituitary expresses ERα, ERβ (56), GPER (57), AR (58), GR, and MR (59). The adrenal cortex expresses ERα, ERβ, GPER, and AR (60). The IML is known to express ERα (61) and AR (62). The DMX shows ERα, ERβ (63), GPER (64), and AR (62) expression. Sympathetic ganglia express ERα, ERβ (65), and AR (66). Cardiac tissue (67–69) and systemic vasculature (70–74) express ERα, ERβ, GPER, and AR, as well as GR and MR. The carotid body shows ERβ (75), GPER (76), GR (77), and MR expression (78). While many of the mechanistic interactions are yet to be elucidated, the integration of these systems modulates stress responses in sex-, age-, and tissue-dependent manners that impact the physiological outcomes of chronic stress. Created with BioRender.com.

Importantly, neurons that activate autonomic and endocrine stress responses are regulated by a network of cortical and limbic structures, allowing for emotional-regulatory regions to modulate stress responses (95). Ovarian hormones have widespread effects on the activity of these corticolimbic regions, potentially accounting for sex differences in stress physiology (96, 97). In fact, estradiol administration in ovariectomized female rats mediates chronic stress-induced morphological plasticity (98) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in the prefrontal cortex (99), a region that has sexually divergent modulatory effects on HPA axis, cardiovascular, and glucoregulatory stress responses (100). Interestingly, a study of gonadectomized and intact rats found that chronically stressed ovariectomized females had increased plasma estradiol compared with unstressed controls (101), suggesting that extra-ovarian estradiol synthesis may be recruited by chronic stress. Furthermore, aromatase-dependent ERα signaling in the prefrontal cortex of ovariectomized female rodents prevents neurobehavioral changes following repeated stress (102).

The hippocampus, a key limbic structure that moderates stress responding (103), is also a site of estrogen action. Hippocampal ERα agonism is protective against chronic stress-induced depressive behaviors in female rats (104). Thus, potential protective effects of central nervous system ERα signaling against the negative outcomes associated with chronic stress require further exploration. There is also sexual dimorphism in the hypothalamic rostral anteroventral periventricular nucleus which expresses CRH receptor 1 in female but not male mice (105). These cells also coexpress both ERα and GR, indicating the presence of a sex-specific stress hormone-responsive nucleus in female mice that may contribute to sexually-divergent homeostatic responses (105). In addition, injection of estradiol into the nucleus of the solitary tract or rostral ventrolateral medulla, brainstem preautonomic nuclei, of ovariectomized rats enhances baroreflex sensitivity and reduces arterial pressure (106). Furthermore, in both the paraventricular nucleus and rostral ventrolateral medulla, ER β, but not ERα, contributes to protection against aldosterone/salt-induced hypertension in female rats (107). Thus, ovarian hormones act in multiple brain regions in a receptor-specific manner to modulate cardiovascular physiology.

The sexually dimorphic distribution of gonadal steroid receptors and their activation by circulating estrogens impacts the development of hypertension, likely through sympathoinhibitory effects (108). This is supported by the increase in hypertension seen in postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women which is, in part, due to a loss of the protective effects of estrogens, centrally estradiol (109). These protective effects are also seen following chronic stress. Chronically stressed cycling female rats maintain vasoactive metabolite profiles, higher NO and lower H2O2, and vascular reactivity compared with both chronically stressed ovariectomized female and male rats. Thus, ovarian hormones mitigate the proinflammatory and prooxidant effects of chronic stress that mediate vascular dysfunction (110).

Taken together, sex-specific physiological responses to chronic stress are impacted by the organizational and activational actions of sex steroids. These responses are integrated across neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular systems. This places additional importance on determining how these interactions are mediated and how they affect long-term health outcomes in both females and males.

GONADAL HORMONES: TESTOSTERONE

Although testosterone is not unique to males, it plays an important role in male-specific responses to chronic stress. The central effects of androgens are mediated by androgen receptors (AR) by binding either testosterone or dihydrotestosterone. Generally, androgens are protective against the development of metabolic syndrome, while male testosterone deficiency associates with signs of metabolic dysfunction such as insulin resistance (111). Furthermore, hypotestosteronemia in rats, via orchidectomy, leads to a progressive rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure that is reduced by the administration of exogenous androgens (112). The antihypertensive effects of endogenous testosterone in male rats are mediated by estrogen-independent genomic and nongenomic mechanisms that reduce kidney renin-angiotensin expression and subsequently reduce fluid retention and increase systemic vasodilation (113). In addition, androgen deficiency is thought to increase the risk of hypertension through increased visceral adiposity, which promotes chronic inflammation that contributes to endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. This cardiometabolic susceptibility is seen in both men and postmenopausal women, who have a reduction in adrenal and ovarian androgens (114). Similarly, testosterone prevents the development of depressive-like symptoms. For instance, testosterone treatment following chronic variable stress reduces passive coping behaviors as well as basal corticosterone and adrenal mass (115). However, research on the mechanistic consequences of AR signaling during chronic stress is limited with more work needed to determine the basis for cardiometabolic regulation.

Although causal effects of androgens on autonomic stress regulation are not well understood, chronic stress decreases expression of the cytochrome P450 protein CYP11A1, subsequently reducing testosterone (116). The reduction in testosterone may play a role in male neuroendocrine regulation, including glucocorticoid secretion, as testosterone inhibits HPA axis stress responses in male rats. Specifically, implantation of testosterone in the hypothalamic medial preoptic area reduces ACTH responses to acute stress, an effect that may be mediated through AR or ER due to the presence of aromatase. In addition, elevated testosterone increases GR binding in the medial preoptic area, possibly contributing to negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis (117). Taken together, reduced testosterone following chronic stress likely factors into HPA axis dysregulation. However, it is unclear how cardiovascular outcomes may be impacted.

SEX DIFFERENCES IN AUTONOMIC INTEGRATION

In addition to the acute actions of gonadal hormones, sex differences in stress responding may also arise from organizational and/or chromosomal effects that lead to variations in autonomic signaling. This is particularly evident in cardiovascular physiology. Although blood pressure and muscle sympathetic nerve activity are directly related in males, these two physiological measures are unrelated in actively cycling young women (118). This is attributed to increased β-adrenergic relative to α-adrenergic activity. However, postmenopausal women show a positive relationship between blood pressure and muscle sympathetic nerve activity observed in males. Furthermore, premenopausal women undergoing an acute stress event such as maximal exercise have cardioprotective effects that originate from lower resting sympathetic tone and a more rapid vagal response compared with age-matched males (119). In addition, women have increased parasympathetic activity in response to acute painful stimuli compared with men (120).

Generally, vagal activity increases heart rate variability and lowers both heart rate and blood pressure. However, this regulation varies across sex, cycle, and life stage. In females, cycle phases characterized by low estrogens are associated with increased basal heart rate and arterial pressure, as well as decreased baroreflex sensitivity (121). Conversely, high estrogenic phases are associated with increased cardiovascular autonomic modulation (121). Postmenopausal women also show decreased vagal responses and heart rate variability (122, 123) that are reversed by estrogen replacement therapy (124). Interestingly, vagal activity influences β-adrenergic signaling in the rat hippocampus (125), indicating that interplay of both central and peripheral neural activation may contribute to the cognitive and vascular protective effects of estrogens. It remains to be determined how these protective effects impact responses to chronic stress; although, recent studies found cycling female rats were resilient to cardiac hypertrophic remodeling (100) and baroreflex impairment following chronic stress (126). In addition, cycling female rodents were resistant to chronic stress-induced conduit artery and resistance arteriole endothelial-dependent vascular dysfunction and inflammation (127). It is important to note that not all studies have found beneficial effects for ovary-intact females exposed to chronic stress. In fact, ovarian factors are necessary for the cardiovascular consequences of witnessing social defeat including increased blood pressure, arrhythmias, and reduced heart rate variability (128).

Autonomic imbalance also impacts immune regulation. Importantly, inflammatory cytokines have been proposed to link cardiovascular and mood outcomes (129). Furthermore, the regulation of interleukin-1β during chronic stress, an inflammatory cytokine elevated in depressive disorders (130) and chronic stress (131), is influenced by β-adrenergic signaling in male, but not female rats (132). Moreover, chronic stress enhances immune reactivity in a sex-dependent manner whereby male rats have excessive innate immune signaling and females show excessive hippocampal immune reactivity (133). In addition, intact, but not OVX, female rats that witnessed social defeat also have increased interleukin-1β in the central amygdala (128). These sex-dependent changes, among others, are indicative of broad differences in HPA axis activity and sympathovagal balance, likely accounting for sex differences in behavior and physiology.

Although a large body of literature indicates that chronic stress sensitizes male HPA axis stress responses to promote glucocorticoid hypersecretion (9), recent studies in female rodents have yielded equivocal results. A study focusing on the effects of chronic stress in adolescent rats found that female rats had enhanced HPA axis stress reactivity in adulthood that was attenuated by a GR modulator (134). However, a similar adolescent chronic stress study found decreased HPA axis activation in adult female rats (135). More recently, a longitudinal rodent study found that, compared with male littermates, chronically-stressed female rats have increased HPA axis responses to both psychological and glycemic stressors, as well as impaired glucose tolerance (4). Furthermore, the enhanced glucocorticoid responses to glycemic stress persisted into late adulthood. Taken together, the data to date suggest that chronic stress results in numerous sex-specific physiological changes linked to endocrine and autonomic dysregulation that impact long-term health and disease susceptibility. Conflicting results across studies indicate that our current understanding of female endocrine regulation during and after chronic stress is incomplete. Additional studies to parse organizational, reproductive cycle, and life-stage effects are likely to uncover significant new information about basic stress biology.

IMPLICATIONS

The study of sex-specific autonomic responses to stress is a developing area with many unanswered questions. Determining the underlying mechanisms that promote sex-specific differences in disease occurrence is essential for improving clinical outcomes and may lead to targeted sex-specific preventative care. In addition, these physiological processes have broad implications for aging pre-, peri-, and postmenopausal women, particularly those with higher allostatic loads due to adverse life events. The higher female incidence of comorbid cardiometabolic and mood disorders, coupled with sexually dimorphic responses to stress, are hypothesized to contribute to increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, which also disproportionately affects women (136). Thus, understanding how the endocrine and autonomic consequences of chronic stress affect health across the lifespan is highly important for improving cardiovascular, metabolic, emotional, and cognitive outcomes.

GRANTS

This study was supported by NIH grants F30 OD032120 (to C.D.), R01 DK105826 (to R.J.H.), and R01 HL150559 (to B.M.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.D., R.J.H., and B.M. conceived and designed research; C.D. prepared figures; C.D. drafted manuscript; B.M. edited and revised manuscript; C.D. and B.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Stuart Tobet and Taben Hale for helpful comments. Graphical abstract and Fig. 1 were created using BioRender.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anand SS, Yi Q, Gerstein H, Lonn E, Jacobs R, Vuksan V, Teo K, Davis B, Montague P, Yusuf S; Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal Peoples Investigators. Relationship of metabolic syndrome and fibrinolytic dysfunction to cardiovascular disease. Circulation 108: 420–425, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080884.27358.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Isfort M, Stevens SCW, Schaffer S, Jong CJ, Wold LE. Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev 19: 35–48, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10741-013-9377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McIntyre RS, Rasgon NL, Kemp DE, Nguyen HT, Law CWY, Taylor VH, Woldeyohannes HO, Alsuwaidan MT, Soczynska JK, Kim B, Lourenco MT, Kahn LS, Goldstein BI. Metabolic syndrome and major depressive disorder: co-occurrence and pathophysiologic overlap. Curr Diab Rep 9: 51–59, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dearing C, Morano R, Ptaskiewicz E, Mahbod P, Scheimann JR, Franco-Villanueva A, Wulsin L, Myers B. Glucoregulation and coping behavior after chronic stress in rats: sex differences across the lifespan. Horm Behav 136: 105060, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2021.105060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Myers B, McKlveen JM, Herman JP. Glucocorticoid actions on synapses, circuits, and behavior: implications for the energetics of stress. Front Neuroendocrinol 35: 180–196, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dhabhar FS. The power of positive stress–a complementary commentary. Stress 22: 526–529, 2019. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2019.1634049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chrousos G, Gold P. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA 267: 1244–1252, 1992. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480090092034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sudheimer K, Keller J, Gomez R, Tennakoon L, Reiss A, Garrett A, Kenna H, O'Hara R, Schatzberg AF. Decreased hypothalamic functional connectivity with subgenual cortex in psychotic major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 40: 849–860, 2015. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Herman JP, Mcklveen JM, Ghosal S, Kopp B, Wulsin A, Makinson R, Scheimann J, Myers B. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr Physiol 6: 603–621, 2016. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150015.Regulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Langellier BA, Fleming PJ, Kemmick Pintor JB, Stimpson JP. Allostatic load among U.S.- and foreign-born whites, blacks, and Latinx. Am J Prev Med 60: 159–168, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Algren MH, Ekholm O, Nielsen L, Ersbøll AK, Bak CK, Andersen PT. Associations between perceived stress, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 18: 1–12, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5170-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ursache A, Merz E, Melvin S, Meyer J, Noble K. Socioeconomic status, hair cortisol and internalizing symptoms in parents and children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 78: 142–150, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.020.Socioeconomic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graves KY, Nowakowski ACH. Childhood socioeconomic status and stress in late adulthood: a longitudinal approach to measuring allostatic load. Glob Pediatr Health 4: 1–12, 2017. doi: 10.1177/2333794x17744950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen S, Schwartz JE, Epel E, Kirschbaum C, Sidney S, Seeman T. Socioeconomic status, race, and diurnal cortisol decline in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Psychosom Med 68: 41–50, 2006. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195967.51768.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmeer K, Yoon A. SES inequalities in low-grade inflammation during childhood. Arch Dis child 101: 1043–1047, 2016. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310837.SES. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stringhini S, Polidoro S, Sacerdote C, Kelly RS, Van Veldhoven K, Agnoli C, Grioni S, Tumino R, Giurdanella MC, Panico S, Mattiello A, Palli D, Masala G, Gallo V, Castagné R, Paccaud F, Campanella G, Chadeau-Hyam M, Vineis P. Life-course socioeconomic status and DNA methylation of genes regulating inflammation. Int J Epidemiol 44: 1320–1330, 2015. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sullivan AD, Benoit R, Breslend NL, Vreeland A, Compas B, Forehand R. Cumulative socioeconomic status risk and observations of parent depression: are there associations with child outcomes? J Fam Psychol 33: 883–893, 2019. doi: 10.1037/fam0000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Avan A, Digaleh H, Di Napoli M, Stranges S, Behrouz R, Shojaeianbabaei G, Amiri A, Tabrizi R, Mokhber N, Spence JD, Azarpazhooh MR. Socioeconomic status and stroke incidence, prevalence, mortality, and worldwide burden: an ecological analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMC Med 17, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1397-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams J, Allen L, Wickramasinghe K, Mikkelsen B, Roberts N, Townsend N. A systematic review of associations between non-communicable diseases and socioeconomic status within low- and lower-middle-income countries. J Glob Health 8: 020409, 2018. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.020409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hostinar C, Ross K, Chen E, Miller G. Early-life socioeconomic disadvantage and metabolic health disparities. Psychosom Med 79: 514–523, 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saklayen M. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 20: 12, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Picard M, Juster RP, McEwen BS. Mitochondrial allostatic load puts the “gluc” back in glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10: 303–310, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pervanidou P, Chrousos GP. Stress and obesity/metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Int J Pediatr Obes 6: 21–28, 2011. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.615996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chandola T, Brunner E, Marmot M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: prospective study. BMJ, 332: 521–524, 2006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38693.435301.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case–control study. Lancet 364: 937–952, 2004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petrie JR, Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can J Cardiol 34: 575–584, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fiksdal A, Hanlin L, Kuras Y, Gianferante D, Chen X, Thoma MV, Rohleder N. Associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety and cortisol responses to and recovery from acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 102: 44–52, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.11.035.Associations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kohler O, Krogh J, Mors O, Benros ME. Inflammation in depression and the potential for anti-inflammatory treatment. Curr Neuropharmacol 14: 732–742, 2016. doi: 10.2174/1570159x14666151208113700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leonard BE. Inflammation and depression: a causal or coincidental link to the pathophysiology? Acta Neuropsychiatr 30: 1–16, 2018. doi: 10.1017/neu.2016.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldstein JM, Hale T, Foster SL, Tobet SA. Sex differences in major depression and comorbidity of cardiometabolic disorders: impact of prenatal stress and immune exposures. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0146-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCorry LK. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Am J Pharm Educ 71: 78, 2007. doi: 10.5688/aj710478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tank AW, Lee Wong D. Peripheral and central effects of circulating catecholamines. Compr Physiol 5: 1–15, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Myers B, McKlveen JM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of the stress response: the many faces of feedback. Cell Mol Neurobiol 32: 683–694, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9801-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vom Berg-Maurer CM, Trivedi CA, Bollmann JH, De Marco RJ, Ryu S. The severity of acute stress is represented by increased synchronous activity and recruitment of hypothalamic CRH neurons. J Neurosci 36: 3350–3362, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3390-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Focke CMB, Iremonger KJ. Rhythmicity matters: circadian and ultradian patterns of HPA axis activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 501: 110652, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Firmino EMS, Kuntze LB, Lagatta DC, Dias DPM, Resstel LBM. Effect of chronic stress on cardiovascular and ventilatory responses activated by both chemoreflex and baroreflex in rats. J Exp Biol 222, 2019. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sgoifo A, Carnevali L, Grippo AJ. The socially stressed heart. Insights from studies in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 39: 51–60, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Farah VMA, Joaquim LF, Bernatova I, Morris M. Acute and chronic stress influence blood pressure variability in mice. Physiol Behav 83: 135–142, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Han K, Min J, Lee M, Kang BM, Park T, Hahn J, Yei J, Lee J, Woo J, Lee CJ, Kim SG, Suh M. Neurovascular coupling under chronic stress is modified by altered GABAergic interneuron activity. J Neurosci 39: 10081–10095, 2019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oliveira LA, Gomes-de-Souza L, Benini R, Wood SK, Crestani CC. Both CRF1 and CRF2 receptors in the bed nucleus of stria terminalis are involved in baroreflex impairment evoked by chronic stress in rats. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 105: 110009, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ulrich-Lai YM, Figueiredo HF, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Engeland WC, Herman JP. Chronic stress induces adrenal hyperplasia and hypertrophy in a subregion-specific manner. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E965–E973, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00070.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 83: 25–41, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Starr LR, Dienes K, Li YI, Shaw ZA. Chronic stress exposure, diurnal cortisol slope, and implications for mood and fatigue: moderation by multilocus HPA-Axis genetic variation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 100: 156–163, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz W. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 287, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rodgers JL, Jones J, Bolleddu SI, Vanthenapalli S, Rodgers LE, Shah K, Karia K, Panguluri SK. Cardiovascular risks associated with gender and aging. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 6, 2019. doi: 10.3390/jcdd6020019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Burt VK, Stein K. Epidemiology of depression throughout the female life cycle. J Clin Psychiatry 63: 9–15, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 Update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 115: e69–e171, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang A, Rovner B, Casten R. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289: 3095–3105, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00132578-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zeng X, Xie Y-J, Liu Y-T, Long S-L, Mo Z-C. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: correlation between hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance and obesity. Clin Chim Acta 502: 214–221, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Viau V, Meaney MJ. Variations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress during the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinology 129: 2503–2511, 1991. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davis SR, Martinez-Garcia A, Robinson PJ, Handelsman DJ, Desai R, Wolfe R, Bell RJ; ASPREE Investigator Group. Estrone is a strong predictor of circulating estradiol in women age 70 years and older. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105: E3348–E3354, 2020. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Contoreggi NH, Mazid S, Goldstein LB, Park J, Ovalles AC, Waters EM, Glass MJ, Milner TA. Sex and age influence gonadal steroid hormone receptor distributions relative to estrogen receptor β-containing neurons in the mouse hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Comp Neurol 529: 2283–2310, 2021. doi: 10.1002/cne.25093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bao AM, Fischer DF, Wu YH, Hol EM, Balesar R, Unmehopa UA, Zhou JN, Swaab DF. A direct androgenic involvement in the expression of human corticotropin-releasing hormone. Mol Psychiatry 11: 567–576, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Evans AN, Liu Y, MacGregor R, Huang V, Aguilera G. Regulation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone transcription by elevated glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol 27: 1796–1807, 2013. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Han F, Ozawa H, Matsuda KI, Nishi M, Kawata M. Colocalization of mineralocorticoid receptor and glucocorticoid receptor in the hippocampus and hypothalamus. Neurosci Res 51: 371–381, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Manoranjan B, Salehi F, Scheithauer BW, Rotondo F, Kovacs K, Cusimano MD. Estrogen receptors α and β immunohistochemical expression: clinicopathological correlations in pituitary adenomas. Anticancer Res 30: 2897–2904, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hu P, Liu J, Yasrebi A, Gotthardt JD, Bello NT, Pang ZP, Roepke TA. Gq protein-coupled membrane-Initiated estrogen signaling rapidly excites corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in female mice. Endocrinology 157: 3604–3620, 2016. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maejima Y, Aoyama M, Ookawara S, Hirao A, Sugita S. Distribution of the androgen receptor in the diencephalon and the pituitary gland in goats: co-localisation with corticotrophin releasing hormone, arginine vasopressin and corticotrophs. Vet J 181: 193–199, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Keller-Wood M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-feedback control. Compr Physiol 5: 1161–1182, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Trejter M, Jopek K, Celichowski P, Tyczewska M, Malendowicz LK, Rucinski M. Expression of estrogen, estrogen related and androgen receptors in adrenal cortex of intact adult male and female rats. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 53: 133–144, 2015. doi: 10.5603/FHC.a2015.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. VanderHorst VGJM, Terasawa E, Ralston HJ. Estrogen receptor-α immunoreactive neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord of the female rhesus monkey: species-specific characteristics. Neuroscience 158: 798–810, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Coolen RL, Cambier JC, Spantidea PI, van Asselt E, Blok BFM. Androgen receptors in areas of the spinal cord and brainstem: a study in adult male cats. J Anat 239: 1–11, 2021. doi: 10.1111/joa.13407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schlenker EH, Hansen SN. Sex-specific densities of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the subnuclei of the nucleus tractus solitarius, hypoglossal nucleus and dorsal vagal motor nucleus weanling rats. Brain Res 1123: 89–100, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brailoiu E, Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Mizuo K, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ. Distribution and characterization of estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 in the rat central nervous system. J Endocrinol 193: 311–321, 2007. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zoubina EV, Smith PG. Distributions of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in sympathetic neurons of female rats: enriched expression by uterine innervation. J Neurobiol 52: 14–23, 2002. doi: 10.1002/neu.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Young WJ, Chang C. Ontogeny and autoregulation of androgen receptor mRNA expression in the nervous system. Endocrine 9: 79–88, 1998. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:9:1:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mahmoodzadeh S, Dworatzek E. The role of 17β-estradiol and estrogen receptors in regulation of Ca2+ channels and mitochondrial function in cardio myocytes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10: 1–15, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lizotte E, Grandy SA, Tremblay A, Allen BG, Fiset C. Expression, distribution and regulation of sex steroid hormone receptors in mouse heart. Cell Physiol Biochem 23: 075–086, 2009. doi: 10.1159/000204096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Oakley RH, Cruz-Topete D, He B, Foley JF, Myers PH, Xu X, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Chambon P, Willis MS, Cidlowski JA. Cardiomyocyte glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors directly and antagonistically regulate heart disease in mice. Sci Signal 12: eaau9685, 2019. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau9685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gros R, Ding Q, Liu B, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. Aldosterone mediates its rapid effects in vascular endothelial cells through GPER activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C532–C540, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00203.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yeap BB. Androgens and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 17: 269–276, 2010. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283383031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med 340: 1801–1811, 1999. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Faulkner JL, Belin de Chantemèle EJ. Mineralocorticoid receptor and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 21, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11906-019-0981-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kornel L, Nelson WA, Manisundaram B, Chigurupati R, Hayashi T. Mechanism of the effects of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids on vascular smooth muscle contractility. Steroids 58: 580–587, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0039-128X(93)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Joseph V, Doan VD, Morency CE, Lajeunesse Y, Bairam A. Expression of sex-steroid receptors and steroidogenic enzymes in the carotid body of adult and newborn male rats. Brain Res 1073-1074: 71–82, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Broughton BRS, Miller AA, Sobey CG. Endothelium-dependent relaxation by G protein-coupled receptor 30 agonists in rat carotid arteries. Am J Physiol—Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1055–H1061, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00878.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Falvey A, Duprat F, Simon T, Hugues-Ascery S, Conde SV, Glaichenhaus N, Blancou P. Electrostimulation of the carotid sinus nerve in mice attenuates inflammation via glucocorticoid receptor on myeloid immune cells. J Neuroinflammation 17: 1–12, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lombès M, Oblin ME, Gasc JM, Baulieu EE, Farman N, Bonvalet JP. Immunohistochemical and biochemical evidence for a cardiovascular mineralocorticoid receptor. Circ Res 71: 503–510, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ikeda K, Horie-Inoue K, Inoue S. Functions of estrogen and estrogen receptor signaling on skeletal muscle. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 191: 105375, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chen C, Gong X, Yang X, Shang X, Du Q, Liao Q, Xie R, Chen Y, Jingyu XU. The roles of estrogen and estrogen receptors in gastrointestinal disease (Review). Oncol Lett 18: 5673–5680, 2019. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hutson DD, Gurrala R, Ogola BO, Zimmerman MA, Mostany R, Satou R, Lindsey SH. Estrogen receptor profiles across tissues from male and female Rattus norvegicus. Biol Sex Differ 10: 4–13, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13293-019-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Arias-Loza PA, Jazbutyte V, Pelzer T. Genetic and pharmacologic strategies to determine the function of estrogen receptor α and estrogen receptor β in cardiovascular system. Gend Med 5: 34–45, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Taraborrelli S. Physiology, production and action of progesterone. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94: 8–16, 2015. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Li W, Li D, Sun L, Li Z, Yu L, Wu S. The protective effects of estrogen on hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by downregulating the Ang II/AT1R pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 503: 2543–2548, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bing LS, Gao ZM. Neuroprotective effect of estrogen: role of nonsynaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Brain Res Bull 93: 27–31, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Liu R, Yang SH. Window of opportunity: estrogen as a treatment for ischemic stroke. Brain Res 1514: 83–90, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhao Z, Mai Z, Ou L, Duan X, Zeng G. Serum estradiol and testosterone levels in kidney stones disease with and without calcium oxalate components in naturally postmenopausal women. PLoS One 8: 1–6, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lagranha CJ, Silva TLA, Silva SCA, Braz GRF, da Silva AI, Fernandes MP, Sellitti DF. Protective effects of estrogen against cardiovascular disease mediated via oxidative stress in the brain. Life Sci 192: 190–198, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zhou Z, Ribas V, Rajbhandari P, Drew BG, Moore TM, Fluitt AH, Reddish BR, Whitney KA, Georgia S, Vergnes L, Reue K, Liesa M, Shirihai O, Van Der Bliek AM, Chi NW, Mahata SK, Tiano JP, Hewitt SC, Tontonoz P, Korach KS, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Hevener AL. Estrogen receptor alpha protects pancreatic beta cells from apoptosis by preserving mitochondrial function and suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem 293: 4735–4751, 2018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.805069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Steagall RJ, Yao F, Shaikh SR, Abdel-Rahman AA. Estrogen receptor α activation enhances its cell surface localization and improves myocardial redox status in ovariectomized rats. Life Sci 182: 41–49, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mann V, Huber C, Kogianni G, Collins F, Noble B. The antioxidant effect of estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators in the inhibition of osteocyte apoptosis in vitro. Bone 40: 674–684, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cho JJ, Cadet P, Salamon E, Mantione KJ, Stefano GB. The nongenomic protective effects of estrogen on the male cardiovascular system: clinical and therapeutic implications in aging men. Med Sci Monit 9: 63–68, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ghimire A, Howlett SE. An acute estrogen receptor agonist enhances protective effects of cardioplegia in hearts from aging male and female mice. Exp Gerontol 141: 111093, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.111093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sheng JA, Bales NJ, Myers SA, Bautista AI, Roueinfar M, Hale TM, Handa RJ. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: development, programming actions of hormones, and maternal-fetal interactions. Front Behav Neurosci 14: 601939–601921, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.601939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Myers B. Corticolimbic regulation of cardiovascular responses to stress. Physiol Behav 172: 49–59, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Handa RJ, Weiser MJ. Gonadal steroid hormones and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Front Neuroendocrinol 35: 197–220, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Handa RJ, Mani SK, Uht RM. Estrogen receptors and the regulation of neural stress responses. Neuroendocrinology 96: 111–118, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000338397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Garrett JE, Wellman CL. Chronic stress effects on dendritic morphology in medial prefrontal cortex: sex differences and estrogen dependence. Neuroscience 162: 195–207, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Karisetty BC, Joshi PC, Kumar A, Chakravarty S. Sex differences in the effect of chronic mild stress on mouse prefrontal cortical BDNF levels: a role of major ovarian hormones. Neuroscience 356: 89–101, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wallace T, Schaeuble D, Pace SA, Schackmuth MK, Hentges ST, Chicco AJ, Myers B. Sexually divergent cortical control of affective-autonomic integration. Psychoneuroendocrinology 129: 105238, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Guo L, Chen YX, Hu YT, Wu XY, He Y, Wu JL, Huang ML, Mason M, Bao AM. Sex hormones affect acute and chronic stress responses in sexually dimorphic patterns: consequences for depression models. Psychoneuroendocrinology 95: 34–42, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wei J, Yuen EY, Liu W, Li X, Zhong P, Karatsoreos IN, McEwen BS, Yan Z. Estrogen protects against the detrimental effects of repeated stress on glutamatergic transmission and cognition. Mol Psychiatry 19: 588–598, 2014. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Jacobson L, Sapolsky R. The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocr Rev 12: 118–134, 1991. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Qu N, Wang X-M, Zhang T, Zhang S-F, Li Y, Cao F-Y, Wang Q, Ning L-N, Tian Q. Estrogen receptor α agonist is beneficial for young female rats against chronic unpredicted mild stress-induced depressive behavior and cognitive deficits. J Alzheimers Dis 77: 1077–1093, 2020. doi: 10.3233/jad-200486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Rosinger Z, Jacobskind J, Bulanchuk N, Malone M, Fico D, Justice N, Zuloaga D. Characterization and gonadal hormone regulation of a sexually dimorphic corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1 cell group. J Comp Neurol 527: 1056–1069, 2019. doi: 10.1002/cne.24588.Characterization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Saleh MC, Connell BJ, Saleh TM. Autonomic and cardiovascular reflex responses to central estrogen injection in ovariectomized female rats. Brain Res 879: 105–114, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Xue B, Zhang Z, Beltz TG, Johnson RF, Guo F, Hay M, Johnson AK. Estrogen receptor-β in the paraventricular nucleus and rostroventrolateral medulla plays an essential protective role in aldosterone/salt-induced hypertension in female rats. Hypertension 61: 1255–1262, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Sabbatini AR, Kararigas G. Estrogen-related mechanisms in sex differences of hypertension and target organ damage. Biol Sex Differ 11: 1–17, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00306-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Brahmbhatt Y, Gupta M, Hamrahian S. Hypertension in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Curr Hypertens Rep 21: 1–10, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11906-019-0979-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Brooks SD, Hileman SM, Chantler PD, Milde SA, Lemaster KA, Frisbee SJ, Shoemaker JK, Jackson DN, Frisbee JC. Protection from vascular dysfunction in female rats with chronic stress and depressive symptoms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 314: H1070–H1084, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00647.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Morford J, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences in the effects of androgens acting in the central nervous system on metabolism. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 18: 415–424, 2016. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.4/fmauvais. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Perusquía M, Contreras D, Herrera N. Hypotestosteronemia is an important factor for the development of hypertension: elevated blood pressure in orchidectomized conscious rats is reversed by different androgens. Endocrine 65: 416–425, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-01978-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hanson AE, Perusquia M, Stallone JN. Hypogonadal hypertension in male Sprague-Dawley rats is renin-angiotensin system-dependent: role of endogenous androgens. Biol Sex Differ 11: 1–13, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Moretti C, Lanzolla G, Moretti M, Gnessi L, Carmina E. Androgens and hypertension in men and women: a unifying view. Curr Hypertens Rep 19: 44, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wainwright SR, Workman JL, Tehrani A, Hamson DK, Chow C, Lieblich SE, Galea LAM. Testosterone has antidepressant-like efficacy and facilitates imipramine-induced neuroplasticity in male rats exposed to chronic unpredictable stress. Horm Behav 79: 58–69, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Arun S, Burawat J, Sukhorum W, Sampannang A, Maneenin C, Iamsaard S. Chronic restraint stress induces sperm acrosome reaction and changes in testicular tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in rats. Int J Reprod Biomed 14: 443–452, 2016. doi: 10.29252/ijrm.14.7.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Viau V, Meaney MJ. The inhibitory effect of testosterone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress is mediated by the medial preoptic area. J Neurosci 16: 1866–1876, 1996. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.16-05-01866.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Joyner MJ, Wallin BG, Charkoudian N. Sex differences and blood pressure regulation in humans. Exp Physiol 101: 349–355, 2016. doi: 10.1113/EP085146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kappus RM, Ranadive SM, Yan H, Lane-Cordova AD, Cook MD, Sun P, Harvey IS, Wilund KR, Woods JA, Fernhall B. Sex differences in autonomic function following maximal exercise. Biol Sex Differ 6: 28, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Nahman-Averbuch H, Dayan L, Sprecher E, Hochberg U, Brill S, Yarnitsky D, Jacob G. Physiology & behavior sex differences in the relationships between parasympathetic activity and pain modulation. Physiol Behav 154: 40–48, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ferreira MJ, Sanches IC, Jorge L, Llesuy SF, Irigoyen MC, De Angelis K. Ovarian status modulates cardiovascular autonomic control and oxidative stress in target organs. Biol Sex Differ 11: 1–10, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00290-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Yang SG, Mlček M, Kittnar O. Estrogen can modulate menopausal women’s heart rate variability. Physiol Res 62: S165–S171, 2013. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Brockbank CL, Chatterjee F, Bruce SA, Woledge RC. Heart rate and its variability change after the menopause. Exp Physiol 85: 327–330, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445X.2000.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Virtanen I, Polo O, Polo-Kantola P, Kuusela T, Ekholm E. The effect of estrogen replacement therapy on cardiac autonomic regulation. Maturitas 37: 45–51, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(00)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Shen H, Fuchino Y, Miyamoto D, Nomura H, Matsuki N. Vagus nerve stimulation enhances perforant path-CA3 synaptic transmission via the activation of β-adrenergic receptors and the locus coeruleus. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 523–530, 2012. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Vieira JO, Duarte JO, Costa-Ferreira W, Morais-Silva G, Marin MT, Crestani CC. Sex differences in cardiovascular, neuroendocrine and behavioral changes evoked by chronic stressors in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 81: 426–437, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Stanley SC, Brooks SD, Butcher JT, d’Audiffret AC, Frisbee SJ, Frisbee JC. Protective effect of sex on chronic stress- and depressive behavior-induced vascular dysfunction in BALB/cJ mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 959–970, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00537.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Finnell JE, Muniz BL, Padi AR, Lombard CM, Moffitt CM, Wood CS, Wilson LB, Reagan LP, Wilson MA, Wood SK. Essential role of ovarian hormones in susceptibility to the consequences of witnessing social defeat in female rats. Biol Psychiatry 84: 372–382, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Finnell JE, Wood SK. Neuroinflammation at the interface of depression and cardiovascular disease: evidence from rodent models of social stress. Neurobiol Stress 4: 1–14, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry 13: 717–728, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Wang YL, Han QQ, Gong WQ, Pan DH, Wang LZ, Hu W, Yang M, Li B, Yu J, Liu Q. Microglial activation mediates chronic mild stress-induced depressive- and anxiety-like behavior in adult rats. J Neuroinflammation 15: 1–14, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Barnard DF, Gabella KM, Kulp AC, Parker AD, Dugan PB, Johnson JD. Sex differences in the regulation of brain IL-1β in response to chronic stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 103: 203–211, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Bekhbat M, Howell PA, Rowson SA, Kelly SD, Tansey MG, Neigh GN. Chronic adolescent stress sex-specifically alters central and peripheral neuro-immune reactivity in rats. Brain Behav Immun 76: 248–257, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Cotella EM, Morano RL, Wulsin AC, Martelle SM, Lemen P, Fitzgerald M, Packard BA, Moloney RD, Herman JP. Lasting impact of chronic adolescent stress and glucocorticoid receptor selective modulation in male and female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 112: 104490, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Wulsin AC, Wick-Carlson D, Packard BA, Morano R, Herman JP. Adolescent chronic stress causes hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical hypo-responsiveness and depression-like behavior in adult female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 65: 109–117, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Yan Y, Dominguez S, Fisher DW, Dong H. Sex differences in chronic stress responses and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Stress 8: 120–126, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]