Keywords: deafness, kcnj16, kcnj10, SIDS

Abstract

Inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channels are broadly expressed in many mammalian organ systems, where they contribute to critical physiological functions. However, the importance and function of the Kir5.1 channel (encoded by the KCNJ16 gene) have not been fully recognized. This review focuses on the recent advances in understanding the expression patterns and functional roles of Kir5.1 channels in fundamental physiological systems vital to potassium homeostasis and neurological disorders. Recent studies have described the role of Kir5.1-forming Kir channels in mouse and rat lines with mutations in the Kcnj16 gene. The animal research reveals distinct renal and neurological phenotypes, including pH and electrolyte imbalances, blunted ventilatory responses to hypercapnia/hypoxia, and seizure disorders. Furthermore, it was confirmed that these phenotypes are reminiscent of those in patient cohorts in which mutations in the KCNJ16 gene have also been identified, further suggesting a critical role for Kir5.1 channels in homeostatic/neural systems health and disease. Future studies that focus on the many functional roles of these channels, expanded genetic screening in human patients, and the development of selective small-molecule inhibitors for Kir5.1 channels, will continue to increase our understanding of this unique Kir channel family member.

INTRODUCTION

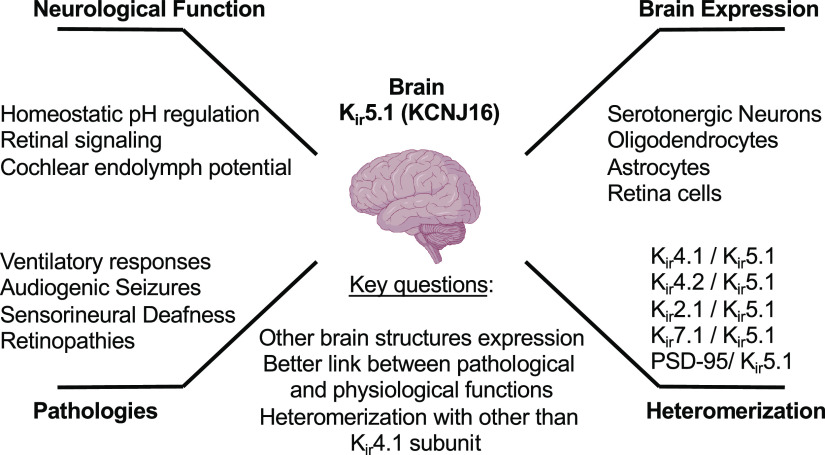

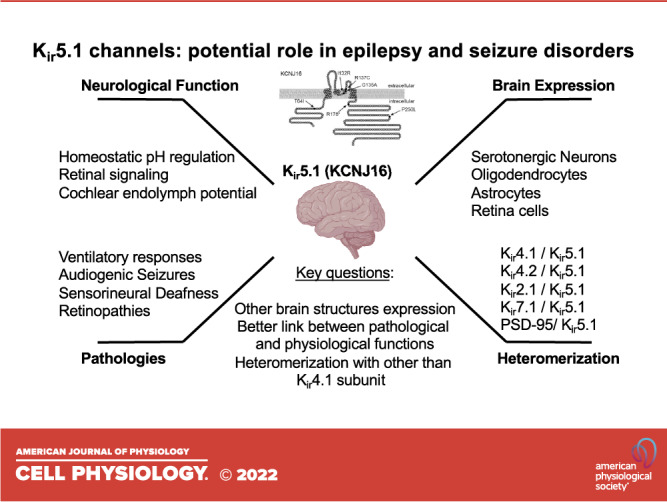

Inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir or IRK) channels are critical elements determining the overall electrical stability of the cell and play a vital function in vertebrate physiology (1–3). These channels contribute a significant potassium conductance from extracellular to intracellular space when cells are not electrically excited and rapidly silence the activity in response to depolarization. In the brain cells, Kir channels are not only responsible for the resting membrane and action potential duration in neurons but may strongly modulate neuronal network activity by the control of glial and astrocytic network function. In particular, Kir5.1 is known to be involved in several brain physiological functions, like homeostatic pH regulation, retinal signaling, and auditory transduction in the cochlea (Fig. 1). However, despite the recent advances and our progress in describing Kir5.1-forming channels, there are still a lot of unresolved questions regarding the expression pattern, heteromerization, and the functional links leading from mutations in Kir5.1 protein to severe pathological conditions like deafness and epilepsy.

Figure 1.

Inwardly rectifying potassium Kir5.1 (KCNJ16) expression and function in the brain. Despite the recently accumulated evidence about the role of Kir5.1 in several pathologies, the knowledge about the expression, functional heteromerization, and physiological function is largely unresolved.

The phylogenetic and developmental analyses of K+ channels indicate that the Kir group is closely related to prokaryotic homologs KirBac (4). The genomic and evolutionary survey of the Kir family genes and their relationship between the genome and the expressed protein structure was described in detail (5). There are four major groups of Kir family members, ATP-regulated (or K+ transport), elementary (or classical), G-protein-activated, and ATP-sensitive (2, 6). Potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 16, or Kir5.1, is related to the elementary/classical group (together with Kir2.1, Kir2.2, Kir2.3, Kir2.4, and Kir2.6) and functionally heteromerized with other Kir members, presumably from ATP-regulated family, like Kir4.1 and Kir4.2 (7, 8). Four pore-forming subunits coded by Kcnj genes are necessary to comprise a functional Kir channel. Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heteromer is the most functionally established and well-described Kir5.1-forming channel highly expressed in the kidney tubules and brain (6, 9–14). Other Kir5.1 heteromerization complexes with Kir4.2 (7), Kir2.1 (15), and Kir7.1 (16) are highly probable but not proven on the level of specific cell expression and physiological function. Homomeric assembly of Kir5.1 is believed to be nonfunctional; however, it was proposed that Kir5.1/PSD-95 complex may exist (17). Kir channels are regulated by multiple factors, including protein kinase C (PKC), phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), nitric oxide synthases (NOS), insulin, pH, and CO2, and may significantly change their properties depending on heteromerization (18–23). As we describe later, there is strong evidence that Kir5.1 did not coassemble with Kir4.1 in some brain cells like neurons and fibrocytes; thus, further studies are needed to elucidate the diversity of Kir5.1-forming channels.

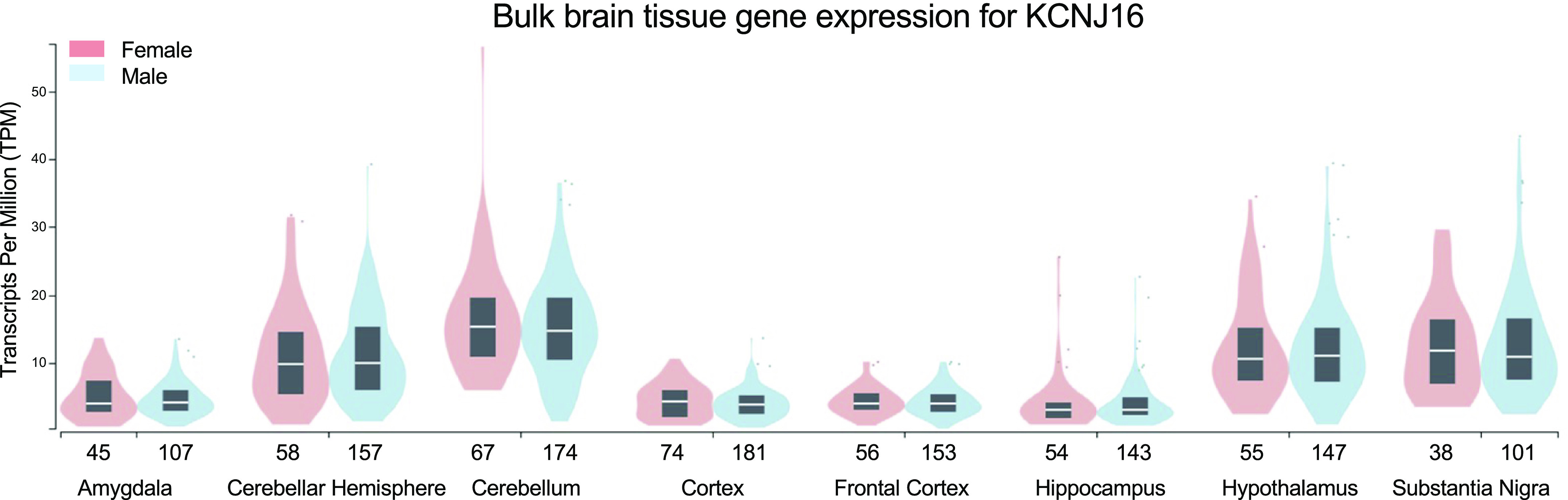

Kir5.1 EXPRESSION

As aforementioned, despite an extensive awareness of the Kir cellular physiology in the brain and other organs, our knowledge about Kir5.1 expression and function is still limited. It was shown that Kir5.1 is predominantly expressed in the thyroid gland (24, 25), kidney (26, 27), and brain (15, 19, 28). In addition, the expression of Kir5.1 was shown in the stomach, liver, testis (29), cochlea (30, 31), and some other organs (32). Correspondingly, these expression patterns are associated with thyroid cancer, abnormalities in cardiorenal function, hearing impairment, and chemosensory control of ventilation. It was initially reported that Kir5.1 is restricted to the evolutionarily older parts of the hindbrain, midbrain, and diencephalon (15). Recent analyses suggest the diverse expression and localization of this protein in the brain cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum (Fig. 2), and essential properties of Kir5.1-forming channels are summarized in recent review articles (12, 13). However, the presence and functional role of specific heteromeric channel complexes in brain cells is mostly unresolved and require extensive investigation. The current review is focused on the potential role of Kir5.1 channels in epilepsy and seizure disorders. Therefore, we mainly focused on the recent studies relevant to the function of these channels in the brain and relative pathological conditions associated with Kir5.1 mutations. The specific role and expression of Kir5.1 in retina, brainstem, and myelinating glia are described in this section below. In addition, due to the potential audiogenic seizures identified in KCNJ16 knockout rats and observed deafness in patients with KCNJ16 mutations, which are discussed Human Diseases and Mutations in KCNJ16, we briefly describe the expression of Kir5.1 in the cochlea.

Figure 2.

Bulk brain tissue gene expression for KCNJ16. The transcripts per million (TPM) values are generated from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) mapping of KCNJ16 expression in the human brain (sample size for female and male groups are reflected in the x-axis) (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/gene/KCNJ16).

Expression in Retinal Müller Cells and Amacrine Neurons

The decrease in potassium transport after downregulation of Kir channels was observed in various retinopathies. Muller cells are the principal radial glial cells of the retina interacting with neurons and act as optical fibers for image transfer through the vertebrate retina with minimal distortion and low scattering (33). They impact synaptic activity by neurotransmitter recycling and may be involved in pathological processes of the retina (34). It was reported that several Kir subunits, including Kir2.1, Kir4.1, and Kir5.1, are expressed and play a vital role in the control of membrane conductance and function of Müller cells (35). Interestingly, Kir5.1 was shown to be expressed in Müller cells and GABAergic-amacrine neurons. The latter is the vertebrate retina interneurons that interact with the ganglion cells and contribute to the generation of transient responses and visual processing within the central nervous system (CNS) (36). The existence of the Kir4.1/Kir5.1 heterotetramer in the retina was confirmed by immunoprecipitation, where this channel is located in the cell body and distal portion of Müller cells. In contrast, homomeric Kir4.1 channels are clustered in the end feet of Müller cells, which form the inner limiting membrane of the retina and surrounding blood vessels (37). K+ channel blockade or gene deletion may result in neuronal hyperexcitability, one of the main factors in progressive retinal degeneration (38). The direct impact on neuronal function can trigger excessive activity and interfere with the transmission of normal signals through the changes in outward potassium flux during action potential or alteration in glial homeostasis (39, 40). The changes in Kir5.1-forming channel activity may control K+ homeostasis in both neuronal and glial cells in the retina and correspondingly contribute to the pathological changes from different angles. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of functional Kir5.1 channels modulating physiological processes in the retinal cells for optimizing future therapies to forestall visual loss or restore sight.

Expression in Brainstem 5-HT Neurons

Serotonergic or 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine) neurons in the CNS modulate arousal, chemoreception, autonomic function, upper airway reflexes, and thermoregulation (41). The neural network of brainstem cells serves as an important regulator of ventilation by the tide control of blood gases and pH. It was suggested that CO2-sensitive neurons in locus coeruleus, raphe nucleus, and medullary raphe express Kir5.1 and could play an important role in central chemoreception (3, 42, 43). The expression of pH-sensitive ion channels in brainstem serotonergic neurons is particularly essential for their cellular CO2/pH and ventilatory sensitivity (44). Accordingly, it was proposed that Kir5.1 is responsible for modulating peripheral chemosensory information to the CNS and corresponding control of the phrenic nerve that activates the diaphragm contraction and air inhalation (45). The recent data indicate that pH-sensitive Kir5.1-forming channels are highly expressed and underlie cellular CO2/pH chemosensitivity in the brainstem (42). Interestingly, immunofluorescence labeling with 5-HT neuron-specific tryptophan hydroxylase (Tph2) gene shows Kir5.1 but not Kir4.1 subunit colocalization to brainstem 5-HT neurons (42). The astrocytes network may also control breathing through the pH-dependent ATP release (46). It was proposed that the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN), a brainstem nucleus that mediates the effect of brain acidification on breathing (47), may sense CO2/H+ by inhibition of Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels in astrocytes, further providing an excitatory purinergic drive to pH-sensitive neurons (48). The involvement of Kir5.1 in RTN astrocytes’ sensitivity to H+ and CO2 was later confirmed using a Kir5.1 knockout rat (49). It is possible that different Kir5.1-forming channels in astrocytes and neurons contribute to the complex mechanisms of central respiratory chemoreception and may provide a basis for developing new respiratory therapy.

Expression in Oligodendrocytes

The neuroglial cells maintain insulation to axons of the CNS neurons and regulate potential propagation. It was suggested that the Kir channels function is essential for axon integrity and the development of neuronal networks (50). In particular, this critical role is contributed to the heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels, which are possibly responsible for maintaining myelin integrity in the face of large ionic shifts associated with action potential propagation along myelinated axons (51). The specific deletion of Kir4.1 in oligodendrocytes is associated with the reduction in Kir5.1 expression and suggests the functional presence of heteromeric channels in these cells (50). It should be noted that the knockout of Kir5.1 in rodents does not confirm this role, and the main function in oligodendrocytes maturation and function can be attributed to Kir4.1 homomeric channels (52).

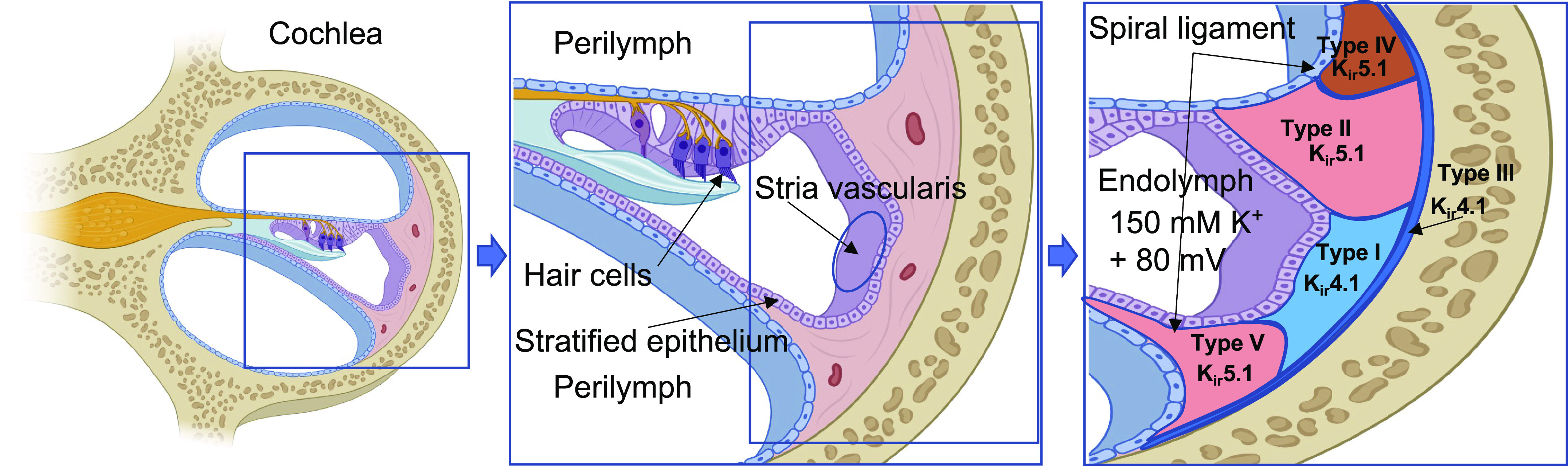

Expression in the Cochlea

The ionic currents are mediated by an electrical potential in the perilymph and endolymph of the cochlear duct regulating the electrical signaling of hair cells. The mechanoreceptive activation of auditory hair cells transfers signals to the brainstem and is responsible for the primary brain hearing function. The cochlea in the inner ear is formed by stratified epithelium and filled with high potassium concentration endolymph fluid (around 150 mM) (53). The high potassium concentration and corresponding potential are mediated by the stria vascularis basal cells involved in the regulation of potassium transport and corresponding hair cell sensitivity. Structural and functional damage caused by the stria vascularis or the spiral ligament of the cochlear wall causes hearing loss, but the mechanism underlying this is unclear (54). Immune gold labeling and fluorescent antibody staining of rat cochlea show that Kir5.1 is expressed in specific types of fibrocytes located in the spiral ligament of the cochlear wall, suggesting its direct functional importance in the establishment of endocochlear potential (31). Type I and II spiral ligament fibrocytes are the major cells in this part of the cochlea (Fig. 3). Type I fibrocytes are adjusted to the stria vascularis and highly express Kir4.1 subunit. Similarly, Type III fibrocytes forming a line on the bony otic capsule express Kir4.1. Type II and V fibrocytes are structurally very similar to each other, and are known to play an important role in K+ recycling and specifically express Kir5.1 channels (31, 55). It was reported that low threshold noise-induced loss of Type IV fibrocytes in humans might account for unexplained hearing losses (56). This type of cell also highly expresses Kir5.1, but not Kir4.1 subunit (31). In addition, immunoreactivity suggests that the spiral ganglion region neurons show strong expression of Kir5.1. In contrast, the satellite cells wrapping the neurons are Kir4.1 positive, indicating that these two subunits are differentially expressed in various types of cells in the cochlea (31). Kir5.1 protein expression in the cochlea decreased with age (57), suggesting that Kir5.1 might play an important role in the pathogenesis of age-related hearing loss. Interestingly, no significant difference in auditory function was identified in the Kcnj16−/− mice (30).

Figure 3.

The expression of inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir)5.1 subunit in the cochlea lateral wall. The circulation of K+ in cochlear endolymph is essential for hair cells function. K+ is transported to the spiral ligament of the cochlear wall, a connective tissue comprising several types of fibrocytes, and recycled through the basal cells of stria vascularis. Kir5.1 is specifically expressed in type II, IV, and V fibrocytes of the spiral ligament. In contrast, Kir4.1 expression is limited to either type I or III fibrocytes. Created with BioRender.com.

HUMAN DISEASES AND MUTATIONS IN KCNJ16

Human genetic diseases have provided critical insights into the physiological function of many organs and pathophysiologies associated with various diseases. This is particularly relevant to ion channel control, including potassium homeostasis. For instance, hypokalemia is common in the Gitelman and the SeSAME/EAST syndromes, whereas hyperkalemia is a feature of familial hyperkalemic hypertension (FHHt or Gordon syndrome) (58–62). Mutations in Kir channels have been known to cause debilitating diseases ranging from neurological abnormalities to renal and cardiac failures (1, 63). Kir channels, including Kir4.1 and Kir5.1, are major players in the control of membrane potential. In humans, loss-of-function mutations in the KCNJ10 gene have been shown to cause SeSAME/EAST syndrome (58, 64, 65). It is thought that mutations in Kir4.1 (KCNJ10) impair the function of heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels, at least in the kidney. In addition to renal tubulopathy, patients with SeSAME/EAST syndrome experienced epilepsy, limitations in cognitive functioning and skills, ataxia, and sensorineural deafness (58, 64). It should be noted that ataxia is not associated with Kir5.1 mutations in humans and deletion of this protein in rodent genetic models (66, 67). However, it was shown that specific deletion of Kir4.1 in oligodendrocytes promotes progressive neurological symptoms, including abnormal gait and ataxia in mice (50). Both renal and neurological phenotypic outcomes of mutations identified in the KCNJ10 gene are described in a number of excellent review articles (11, 12, 68–71) and outside the scope of this review.

Targeted disruption of the Kcnj16 gene (Kir5.1) in mice resulted in hypokalemic, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis with hypercalciuria (67). In contrast to homozygous Kcnj10−/− mice, which are not able to survive more than 2 wk after birth (58, 72, 73), Kcnj16−/− mice are viable. Not much was known until recently about human mutation in KCNJ16. Thus, mutations in the KCNJ16 gene were reported to cause nonfamilial Brugada syndrome associated with sudden cardiac death (74). Furthermore, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of metabolite quantitative traits identified KCNJ16 as one of the candidates (75). As it was reported in this GWAS, the overdominant model for KCNJ16 resulted in the strongest association among the models tested.

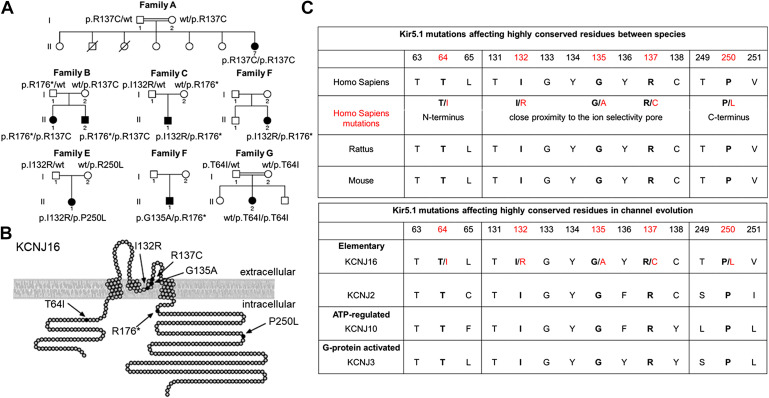

The recent seminal study identified and described the first human mutations in KCNJ16. Recently discovered recessive mutations in KCNJ16 revealed the important function of this protein in both neurological and renal function (76). Shown in Fig. 4 are family pedigrees of identified variants in KCNJ16 and localization of associated Kir5.1 mutations. The mutation could be roughly separated into two groups: mutations close to the ion selectivity pore and mutations in intracellular domains (Fig. 4B). It is known that Kir intracellular domain mutations can be associated with PIP2 binding and promote strong changes in the channel function (77). Genetic analyses revealed KCNJ16 variants in seven individuals from six families. Most patients revealed compulsory heterozygous KCNJ16 mutations in both ion selectivity pore and intracellular domains. Two female patients were identified with only one homozygous mutation either in the ion selectivity pore or intracellular domain. It should be noted that relatively young age of tested individuals ranged from 5 days to 26 years old. Despite the described difference, all patients presented with relatively uniform pathological characteristics like the presence of sensorineural deafness and the absence of seizures or ataxia. In addition, experiments with heterologous expression systems revealed strong relation of all identified variants to cell membrane depolarization and decline in Kir5.1-forming channels expression. The alignments to homologous sequences and residue similarity between the species or different groups of Kir channels (Fig. 4C) suggest that identified human mutations located in highly conserved residues are critical for Kir5.1-forming channels function. Overall, these data suggest that all identified mutations have a similar brain phenotype directly related to the Kir5.1-forming channel function and not to the location of the mutation in the protein sequence. The tubulopathy in these patients included severe hypokalemia together with polyuria, salt craving, and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). It was further proposed that mutations in KCNJ16 result in abnormalities in acid-base homeostasis. However, findings were variable, with either metabolic alkalosis or acidosis. Moreover, one patient changes status from metabolic alkalosis in infancy to acidosis later in childhood. Hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria, typical findings in Gitelman syndrome, were present in single individuals, whereas urinary concentrating ability was largely intact (76). Notably, a Gitelman-like phenotype and abnormalities in RAAS hormone levels seen in these patients contrast the phenotype of Kcnj16−/− mice (67) and are more consistent with the phenotype observed in Dahl salt-sensitive rats with Kcnj16 knockout [SSKcnj16−/− rats, (66, 78, 79)]. Another uniform phenotypic feature of all studied patients was sensorineural hearing impairment diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. Audiograms of individuals with KCNJ16 variants demonstrated a moderate hearing loss, especially at higher frequencies (76). The functional analysis of identified mutants revealed that coinjection of mutant Kir5.1 subunits with either Kir4.1 or Kir4.2 (encoded by KCNJ10 or KCNJ15, respectively) resulted in significant changes in the K+ current and surface expression of the studied channels (76).

Figure 4.

Family pedigrees and localization of identified variants in KCNJ16. A: pedigrees of seven families with eight affected individuals and homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in KCNJ16. Parental consanguinity is indicated by double bars in families A and G. Compound heterozygosity for KCNJ16 variants was analyzed by segregation analysis in the parents. B: localization of variants p.T64I, p.I132R, p.G135A, p.R137C, p.R176*, and p.P250L in the inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir)5.1 channel. Missense variants p.I132R, p.G135A, and p.R137C are located in the pore-forming domain near the selectivity filter of the ion channel. p.T64I is located in the N-terminus near the first transmembrane domain, p.R176* and p.P250L are located in the C-terminus. Adapted from Ref. 76 with permission. C: the identified Kir5.1 mutations are located in highly conserved residues between the species (rodent and human comparisons are shown) and between different evolution groups of Kir channels. Amino acids and corresponding sequence number indicated (Q9NPI9 human isoform, UniProtKB). Red shows mutated human variants represented at B.

Another study also reported a patient identified to have biallelic loss-of-function variants in KCNJ16 who presented with chronic metabolic acidosis with exacerbations triggered by minor infections (80). This 2-yr-old female patient experienced hypokalemic metabolic acidosis. A homozygous variant Lys48, located in the C-terminus before the first transmembrane domain, was identified. This variant was heterozygous in both parents, consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance (80). No functional analysis of identified mutant was performed.

In another recent study, the exome data of 155 sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) cases were screened for variants within 11 genes described in chemoreception. Two mutations (R137S/A188S) were identified in the KCNJ16 gene along with other genes encoding proteins involved in respiratory chemoreception (81). Electrophysiologic analysis of these KCNJ16 variants revealed a loss-of-function for the R137S variant but no obvious impairment for the A188S variant. Although gene variants encoding proteins involved in respiratory chemoreception play a role only in a minority of SIDS cases, this study is highly important since it revealed a potential link between KCNJ16 and SIDS.

THE POTENTIAL ROLE OF KCNJ16 MUTATIONS IN EPILEPSY AND SEIZURES

The potential pathophysiological contributions to human diseases of Kir5.1-forming channels can also be informed by experiments in rodents with Kcnj16 mutations and/or deletions. Mice with a null mutation in the Kcnj16 gene (Kcnj16−/− mice) are viable and do not demonstrate any gross abnormalities other than being ∼15% smaller in weight (67). However, Kcnj16−/− mice show disrupted renal electrolyte balance characterized by a chronic hypokalemic, hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis with high urinary calcium and magnesium (67). These phenotypes appear to contrast the salt-wasting metabolic alkalosis seen in SeSAME/EAST syndrome in humans (58, 65), a disease that has been most directly linked to KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) mutations (58, 64). Dysregulated electrolytes in Kcnj16−/− mice could result from a lack of Kir5.1 subunit-containing Kir channels that possess abnormally high K+ conductance and/or channel activity in the DCT and CCD, and these Kir5.1-lacking channels have blunted pH-sensitive K+ conductance (67) presumably from a loss of heteromultimerization mostly with Kir4.1 or other subunits (82).

We have previously studied a Kcnj16 mutant rat line that was generated in the Dahl Salt-sensitive (SS) genetic background (SSKcnj16−/− rats (66)). Renal Kir5.1 protein was not detectable by immunohistochemistry or Western blots, indicating that the 18 bp deletion in exon 1 of the Kcnj16 gene resulted in a null mutation, which we have confirmed by patch-clamp recordings in renal tubules from SSKcnj16−/− rats. Like Kcnj16−/− mice, the SSKcnj16−/− rats appear outwardly normal other than having a smaller body (−38%) and kidney mass, plasma, and urinary electrolyte disruption, including hypokalemia, and hypotension. However, SSKcnj16−/− rats also showed increased fractional excretion of Na+ in addition to K+ and Mg2+, indicative of a salt-wasting phenotype absent in Kcnj16−/− mice.

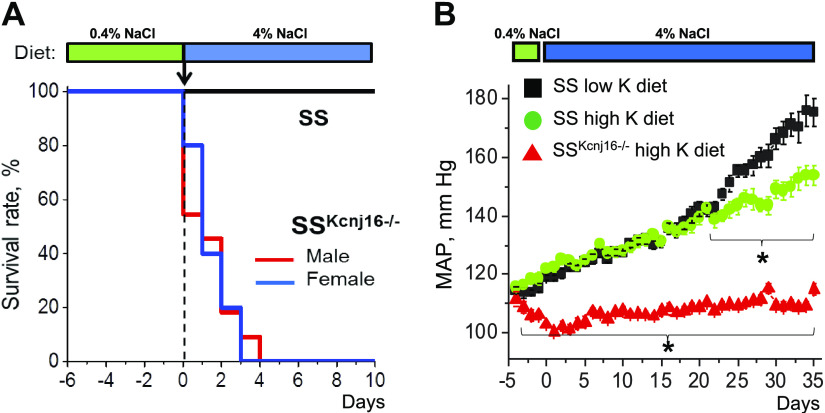

High-salt diets promote substantial hypertension in SS rats (83) over a period of weeks and months. Remarkably, high-salt diets fed to SSKcnj16−/− rats cause rapid mortality within a few days, which was not due to salt-induced hypertension in this model (Fig. 5A). This rapid salt-induced death was eliminated when SSKcnj16−/− rats were fed the diet supplemented with high K+ (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the mortality may be driven by more severe hypokalemia during this salt-induced challenge. Indeed, plasma [K+] in SSKcnj16−/− rats shifts from already low values of ∼2.1 mM on normal salt (0.4% NaCl) to ∼1.3 mM on high salt (4% NaCl) diet in 24 h, making them extremely hypokalemic and therefore subject to sudden cardiac death. Interestingly, SSKcnj16−/− rats fed high-salt diets supplemented with increased K+ not only survive the high-salt load but also maintain normal blood pressures for several weeks despite a massive increase in urinary K+ excretion (Fig. 5B). Deletion of Kir5.1 in mice also revealed that Kir5.1 channel is involved in maintaining the renal ability of K+ excretion during high salt intake (10). Thus, data from mouse and rat models suggest Kir5.1 channels are important for chronic, steady-state electrolyte balance but play a crucial role during high-salt dietary conditions. Overall, the SSKcnj16−/− rats have phenotypes reminiscent of SeSAME/EAST syndrome in humans. It is logical to start the next step and create recently identified human mutations (76, 80, 81) in rodent models. The phenotyping of specific mutations in these novel models and comparison with observed human pathologies will provide a foundation of basic concepts and will advance our knowledge to direct research and clinical strategies in the understanding of Kir5.1-forming channel function in the brain.

Figure 5.

Effects of dietary supplementation on mortality and blood pressure in Dahl salt-sensitive rats with Kcnj16 knockout (SSKcnj16−/−) rats. A: the survival rate of Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) and SSKcnj16−/− rats on a 4% NaCl diet. High-salt intake triggers rapid mortality of SSKcnj16−/− rats. B: the combination of a high-potassium diet and Kir5.1 channel deletion mediate the protective effects on the development of SS hypertension. Shown is the summary of mean arterial pressure (MAP) in SS and SSKcnj16−/− rats. Animals were switched from a 0.4% to a 4% NaCl diet at day 0. Then, SS rats were fed either a standard 4% NaCl diet (black) or a 4% NaCl diet supplemented with high K+ (2% KCl; green). SSKcnj16−/− rats were fed a 4% diet supplemented with high K+ (red). Adapted from Ref. 66 with permission.

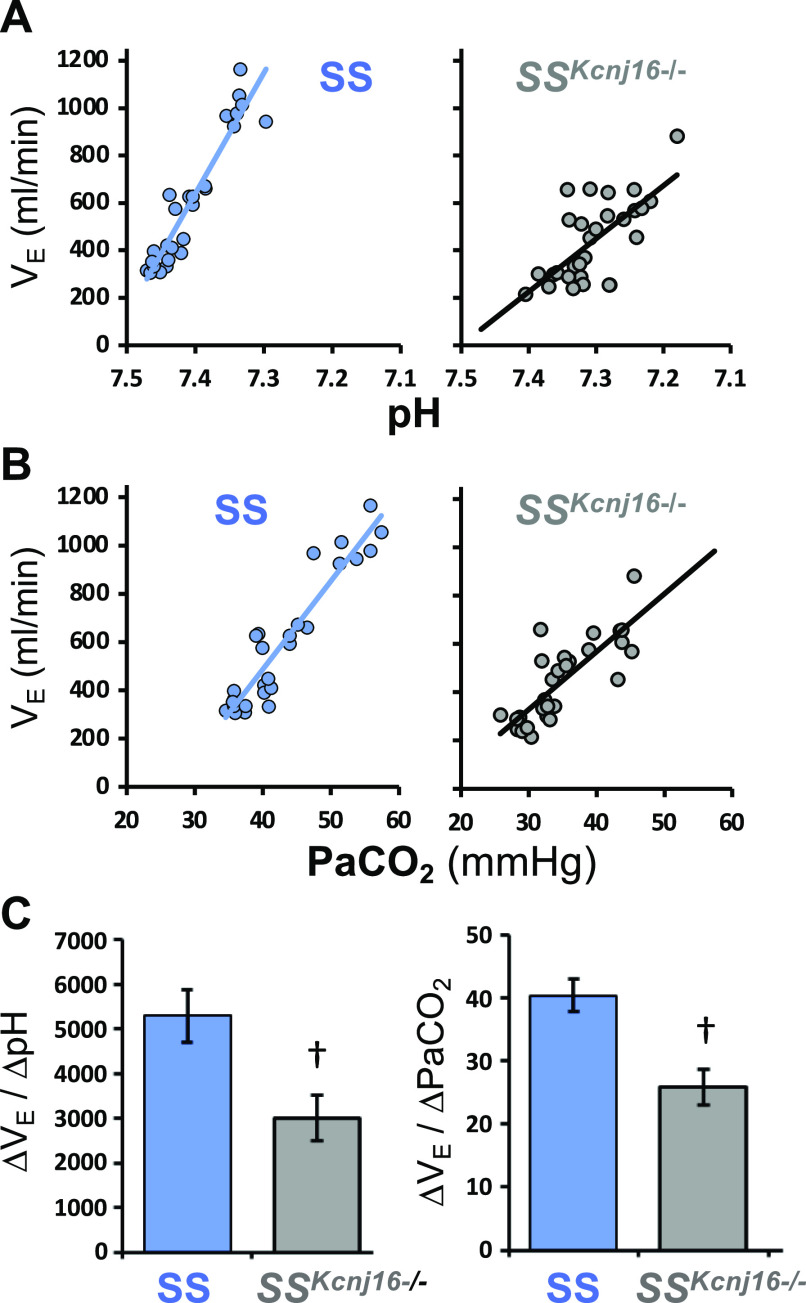

In addition to the contributions to renal electrolyte balance, it has been hypothesized that Kir5.1 subunit-containing heteromeric Kir channels may contribute to cellular pH/CO2 sensitivity in the context of the neural regulation of breathing and acute pH homeostasis through changes in pulmonary ventilation (the ventilatory CO2 chemoreflex). This hypothesis stems from the unique biophysical properties and relative extreme intracellular pH sensitivity in the physiological range (pKa ∼ 7.4) of heteromeric Kir5.1-containing Kir channels compared with other homomeric channels, such as Kir1.1, Kir2.3, Kir4.1, and Kir4.2. Loss of Kir5.1 in mice disrupts the cellular pH sensitivity of neurons in the locus coeruleus, a brainstem nucleus that is known to influence acute pH regulation through the modulation of ventilation. Furthermore, transcriptomic and other data from brainstem serotonergic neurons suggested that Kcnj16 transcript levels increase from early postnatal life into adulthood in parallel with the cellular sensitivity to hypercapnic acidosis in these neurons (42). Therefore, we tested a role for Kir5.1 channels in the CO2 ventilatory chemoreflex in SSKcnj16−/− rats and found that SSKcnj16−/− rats hyperventilated at rest (low ) due to a chronic metabolic acidosis [low arterial [HCO3−] (79)]. Shown in Fig. 6 is total ventilation plotted against arterial pH or arterial Pco2 in SS control and SSkcnj16−/− rats, which allowed for the direct determination of a CO2 sensitivity. When SSKcnj16−/− rats are acutely challenged with increasing levels of inspired CO2 to create respiratory acidosis, the slope of the relationship between ventilation and arterial Pco2 and pH (an index of ventilatory pH sensitivity) was dramatically reduced by ∼45%. Normalizing arterial pH with HCO3− in drinking water or with hydrochlorothiazide treatment [which alkalizes the blood via inhibition of the apical NaCl cotransporter (NCC) in the distal convoluted tubules (67, 84)] further exacerbated the blunted ventilatory response to hypercapnic acidosis. These data highlighted yet another critical role of Kir5.1-containing Kir channels in chronic (renal) and acute (respiratory) pH regulation and suggested a larger role for Kir5.1 in neurological function than previously recognized.

Figure 6.

Ventilatory CO2/pH sensitivity is reduced in Dahl salt-sensitive rats with Kcnj16 knockout (SSKcnj16−/−) rats. Individual data and best-fit plots for the relationship between arterial pH (A) or (B) and ventilation during room air breathing or 3%, 5%, or 7% inspired CO2 in SS controls (blue) and SSKcnj16−/− rats (gray). C: mean data for the slope of the ventilatory responses from individual animals presented in (A) and (B). Adapted from Ref. 79 with permission.

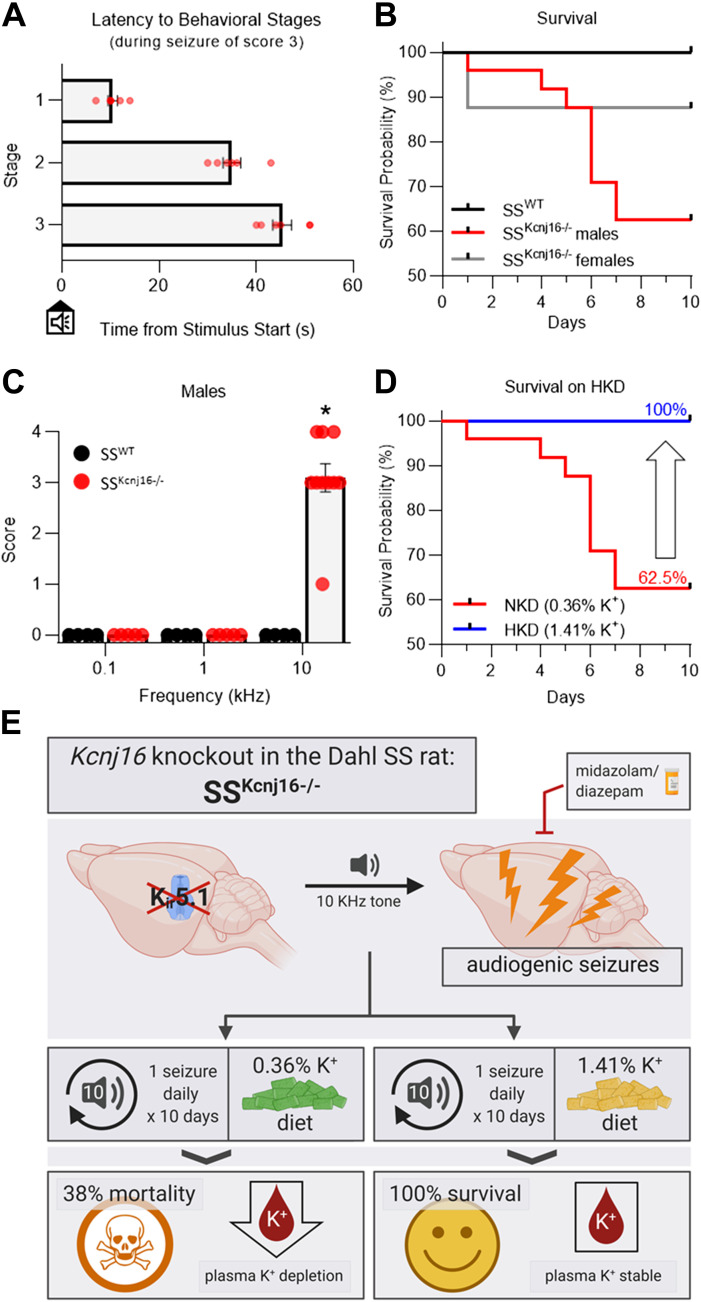

During our work with SSKcnj16−/− rats, we noted that under certain circumstances, these rats exhibited a seizure-like behavior when near running water or exposed to “windy” noises. The seizure-like behavior was reminiscent of other rodent models of audiogenic seizure (85, 86). Based on these observations, we began testing specific tones at various intensities and found that SSKcnj16−/− rats exhibited sound-induced seizure behaviors in response to a specific sound frequency (10 kHz) at a relatively modest intensity (∼75 dB) (Fig. 7, A–C) (87). Telemetric EEG recordings confirmed that these sound-induced seizure behaviors were bona fide seizures with cortical involvement. The behaviors were very stereotypic and followed a behavioral progression from increased running activity (88) to a generalized tonic-clonic seizure with or without an apparent loss of ambulation and/or consciousness. The seizure phenotype was 1) apparent in males and females (males tended to have more severe seizures) from as early as 3 wk of age; 2) sound frequency-specific; 3) readily reproducible; 4) blocked by benzodiazepines such as midazolam and diazepam; 5) associated with a robust (∼1.4°C) increase in body temperature; and 6) was rescued by dietary K+ supplementation (Fig. 7, D and E) (87). Age-matched wild-type SS rats failed to respond to audio stimuli, suggesting that the unique genetic background alone is not sufficient to induce the seizure phenotype observed in SSKcnj16−/− rats. These observations indicated that Kir5.1 subunit mutations were sufficient to induce a seizure disorder in rats, which to our knowledge represents the first model of audiogenic seizure disorder in rats with a known molecular cause.

Figure 7.

Dahl salt-sensitive rats with Kcnj16 knockout (SSKcnj16−/−) rats exhibit audiogenic seizures. A: latency from the start of the acoustic stimulus (10 kHz) to each behavioral stage in seizures that were given a score of 3. B: Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of SSWT and SSKcnj16−/− rats during once daily exposure to the 10 kHz acoustic tone. C: summary of seizure severity scores in response to acoustic stimuli (0.1, 1, and 10 kHz; 2 min each) in male SSWT and SSKcnj16−/− rats. D: average seizure severity (scores averaged over the 10 days for each animal) of SSKcnj16−/− rats during the 10× protocol is compared between rats fed a normal-K+ diet (NKD, 0.36% K+) vs. a high-K+ diet (HKD, 1.41% K+). E: graphical abstract summarizing audiogenic seizures in SSKcnj16−/− rats. Adapted from Ref. 87 with permission.

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) remains the leading cause of death in patients with epilepsy (89), and SUDEP risk is particularly high in patients with intractable, drug-resistant epilepsy (90). SUDEP has been defined as “a sudden, unexpected death in a person with epilepsy, with or without evidence for a seizure preceding the death, in which there is no evidence of other disease, injury, or drowning that caused the death” (91). SUDEP risk factors include persistent or poorly controlled seizures (92, 93) and male sex (94). Our understanding of the events that lead to sudden death in those suffering from epilepsy was dramatically enhanced by the seminal work by Ryvlin et al. (93) in 2013 in the so-called “MORTEMUS” study. This critical study demonstrated that suppression of the ventilatory and cardiovascular systems was prominent during intraictal and postictal periods before death. The events leading to death began with a generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) followed by postictal generalized EEG suppression, transient apnea, bradycardia, respiratory arrest, and then asystole. Importantly, the suppression of respiratory rate and heart rate was maximal within 1–3 min, but cardiorespiratory failure did not occur until 10 to 180 min after seizure termination. Even after successful restoration of cardiac function with CPR, breathing often fails to restart, leading to death. The current hypothesis is that repeated “spread” of the epileptiform activity from cortical epileptic foci to the brainstem leads to cardiorespiratory dysfunction. It is important to point out that most rodent models of audiogenic seizures invariably result in sudden death resulting from cardiorespiratory failure (although some can be resuscitated), which in some ways recapitulates some of the key features of human SUDEP. These models of seizure-induced cardiorespiratory arrest have been used as valuable models for investigating and defining mechanistic insights into the events leading to sudden death.

But humans with epilepsy rarely succumb to their first seizure and in fact, recover from the vast majority of seizures. This is also the case with audiogenic seizures in SSKcnj16−/− rats, where within minutes to hours following each sound-induced seizure, the animals recover to full ambulation (87). Acutely during an audiogenic seizure, SSKcnj16−/− rats demonstrated ictal apnea (87) and ictal asystole, and in the immediate postictal period show suppressed breathing frequency and heart rate (unpublished observations). These vital systems do however recover after 20–30 min, and the animals become ambulatory. However, subjecting SSKcnj16−/− rats to repeated seizures (1/day for up to 10 days) led to spontaneous mortality in approximately one-third of the rats. Importantly, male SSKcnj16−/− rats were more susceptible to repeated seizure-induced mortality than females, which may stem in part from more severe seizures in the males. In addition to high mortality rates, repeated seizures in SSKcnj16−/− rats appear to result in progressive and greater acute effects on breathing and heart rate, and the vital ventilatory responses to respiratory acidosis (hypercapnia) become even more impaired. The mechanisms by which repeated seizures blunt vital cardiorespiratory control systems remain unclear, but maybe the key to thwarting SUDEP-like deaths in this rat model.

Spontaneous death events following repeated seizures in SSKcnj16−/− rats occurred well after the animals had recovered, and thus it remains unclear exactly when or how they succumb following repeated seizures. We hypothesize that repeated seizures may have led to even more severe hypokalemia (87), which could cause arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Alternatively, repeated seizures in this model may also serve as a sort of “priming,” which may lead to spontaneous, more severe seizures from which they cannot recover. These hypotheses and others are still the subject of the current investigation, but nonetheless, the SSkcnj16+ model may be a valuable model to study the mechanisms of human SUDEP in that 1) no pharmacological or painful stimuli are required to repeatedly induce tonic-clonic seizures; 2) repeated seizures lead to a progressive deterioration of acute and chronic cardiorespiratory function (unpublished observations); and 3) repeated seizures lead to spontaneous mortality particularly in males, like that observed in human SUDEP.

The important question is, why does Kir5.1 knockout in rats induce susceptibility to audiogenic seizures? Global Kir5.1 mutations in this model certainly disrupt renal functions leading to dysregulation of electrolytes and pH—both of which could influence general neuronal excitability and potentially lower seizure thresholds. However, normalization of plasma [K+] via dietary supplementation in SSKcnj16−/− rats prevented both high-salt diet-induced and repeated seizure-induced mortality but did not prevent audiogenic seizures (Figs. 5B and 7D), suggesting that the underlying cause of neuronal hyperexcitability remained. In our repeated seizure experiment, high-potassium diet dramatically increased survival and lowered severity score; however, it did not change the probability of the seizures in response to sound stimulation (87). The later critical findings suggest that in some cases, electrolyte disorders may aggravate or trigger seizures in a person with epilepsy but could not be the root of the problem. We speculate that there is a more direct effect of Kir5.1 channel subunit loss on neuronal (and/or glial) function in the brain leading to the seizure phenotype; however, as we discussed earlier, the particular Kir5.1-forming channels responsible for this modulation are still not established. Kir5.1 subunit loss in neurons would be predicted to reduce both single-channel and whole cell K+ conductance to drive resting membrane voltages to a more depolarized state. Consistent with this hypothesis, our previous data showed via fMRI imaging of the brain in SSKcnj16−/− rats an increased light activation of multiple cortical regions suggesting baseline hyperexcitability in the brain (87). Kir5.1 loss may also fundamentally alter glial K+ buffering and thus modulate neuronal excitability indirectly. Distinguishing which of these hypotheses (or others) are valid will require additional experimentation. Still, it could also be further clarified by definitive data on cell type-specific expression, subcellular localization, and heteromerization with other Kir subunits of Kir5.1 in the brain and other organs, which remains elusive.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Recent research efforts focused on Kir5.1-forming channels have demonstrated significant contributions of these channels to several physiological functions, notably in the kidney and brain. Human mutations in KCNJ16 have only recently been identified, and many of these known mutations lead to phenotypes in humans that correlate well with those in knockout rodent models. These recent studies collectively identified a new clinical entity comprising a hypokalemic tubulopathy and sensorineural deafness associated with biallelic mutations in KCNJ16 (76, 80), suggesting that genetic screening for mutations in KCNJ16 should be included in the diagnostic workup for patients presenting with overlapping phenotypes. We hypothesize that other mutations in KCNJ16 in the human population will be uncovered in the near future, particularly in the context of epilepsy and other seizure disorders, given the data in the SSkcnj16−/− rat model. Our further understanding of the specific Kir5.1 heteromerization, functional presence, and relation to the pathology of Kir5.1-forming channels in the brain will require the creation of new animal models with the cell-specific deletion of the Kir5.1 subunit. Thus, the combination of human genetics and animal research should further provide a breakthrough in our knowledge about the role of Kir5.1 in the brain. As the functional roles of these and other Kir channels continue to be revealed, the development of the small molecules targeting specific Kir channels (27, 95–98), including potent and selective pharmacological agents targeting heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels (95), will provide potential therapeutic strategies with translational potential.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R35 HL135749 (to A. Staruschenko), R01 DK126720 (to O. Palygin), R01 HL122358 (to M. R. Hodges), as well as US Department of Veteran Affairs Grant I01 BX004024 (to A. Staruschenko).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

This article is part of the special collection "Inward Rectifying K+ Channels." Jerod Denton, PhD, and Eric Delpire, PhD, served as Guest Editors of this collection.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.S., M.R.H., and O.P. prepared figures; A.S., M.R.H., and O.P. drafted manuscript; A.S., M.R.H., and O.P. edited and revised manuscript; A.S., M.R.H., and O.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hibino H, Inanobe A, Furutani K, Murakami S, Findlay I, Kurachi Y. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev 90: 291–366, 2010. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cui M, Cantwell L, Zorn A, Logothetis DE. Kir channel molecular physiology, pharmacology, and therapeutic implications. Handb Exp Pharmacol 267: 277–356, 2021. doi: 10.1007/164_2021_501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sepulveda FV, Pablo Cid L, Teulon J, Niemeyer MI. Molecular aspects of structure, gating, and physiology of pH-sensitive background K2P and Kir K+-transport channels. Physiol Rev 95: 179–217, 2015. [Erratum in Physiol Rev 96: 1665, 2016]. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durell SR, Guy HR. A family of putative Kir potassium channels in prokaryotes. BMC Evol Biol 1: 14, 2001. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanaka-Kunishima M, Ishida Y, Takahashi K, Honda M, Oonuma T. Ancient intron insertion sites and palindromic genomic duplication evolutionally shapes an elementally functioning membrane protein family. BMC Evol Biol 7: 143, 2007. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palygin O, Pochynyuk O, Staruschenko A. Distal tubule basolateral potassium channels: cellular and molecular mechanisms of regulation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 27: 373–378, 2018. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lam HD, Lemay AM, Briggs MM, Yung M, Hill CE. Modulation of Kir4.2 rectification properties and pHi-sensitive run-down by association with Kir5.1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1758: 1837–1845, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanemoto M, Kittaka N, Inanobe A, Kurachi Y. In vivo formation of a proton-sensitive K+ channel by heteromeric subunit assembly of Kir5.1 with Kir4.1. J Physiol 525: 587–592, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xiao Y, Duan XP, Zhang DD, Wang WH, Lin DH. Deletion of renal Nedd4-2 abolishes the effect of high K(+) intake on Kir4.1/Kir5.1 and NCC activity in the distal convoluted tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 321: F1–F11, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00072.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duan X-P, Wu P, Zhang D-D, Gao Z-X, Xiao Y, Ray EC, Wang W-H, Lin D-H. Deletion of Kir5.1 abolishes the effect of high Na+ intake on Kir4.1 and Na+-Cl− cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 320: F1045–F1058, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00004.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Manis AD, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A, Palygin O. Expression, localization, and functional properties of inwardly rectifying K(+) channels in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 318: F332–F337, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00523.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lo J, Forst AL, Warth R, Zdebik AA. EAST/SeSAME syndrome and beyond: the spectrum of Kir4.1- and Kir5.1-associated channelopathies. Front Physiol 13: 852674, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.852674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Han J, Li L, Zhang Q, Feng Y, Jiang Y, Deng F, Zhang Y, Wu Q, Chen B, Hu J. Inwardly rectifying potassium channel 5.1: structure, function, and possible roles in diseases. Genes Dis 8: 272–278, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palygin O, Pochynyuk O, Staruschenko A. Role and mechanisms of regulation of the basolateral Kir4.1/Kir5.1 K+ channels in the distal tubules. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 219: 260–273, 2017. doi: 10.1111/apha.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Derst C, Karschin C, Wischmeyer E, Hirsch JR, Preisig-Muller R, Rajan S, Engel H, Grzeschik K, Daut J, Karschin A. Genetic and functional linkage of Kir5.1 and Kir2.1 channel subunits. FEBS Lett 491: 305–311, 2001. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papanikolaou M, Lewis A, Butt AM. Glial and neuronal expression of the inward rectifying potassium channel Kir7.1 in the adult mouse brain. J Anat 235: 984–996, 2019. doi: 10.1111/joa.13048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanemoto M, Fujita A, Higashi K, Kurachi Y. PSD-95 mediates formation of a functional homomeric Kir5.1 channel in the brain. Neuron 34: 387–397, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hyndman KA, Isaeva E, Palygin O, Mendoza LD, Rodan AR, Staruschenko A, Pollock JS. Role of collecting duct principal cell NOS1β in sodium and potassium homeostasis. Physiol Rep 9: e15080, 2021. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu H, Cui N, Yang Z, Qu Z, Jiang C. Modulation of kir4.1 and kir5.1 by hypercapnia and intracellular acidosis. J Physiol 524: 725–735, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rapedius M, Paynter JJ, Fowler PW, Shang L, Sansom MS, Tucker SJ, Baukrowitz T. Control of pH and PIP2 gating in heteromeric Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels by H-bonding at the helix-bundle crossing. Channels (Austin) 1: 327–330, 2007. doi: 10.4161/chan.5176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rojas A, Cui N, Su J, Yang L, Muhumuza JP, Jiang C. Protein kinase C dependent inhibition of the heteromeric Kir4.1-Kir5.1 channel. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768: 2030–2042, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zaika OL, Mamenko M, Palygin O, Boukelmoune N, Staruschenko A, Pochynyuk O. Direct inhibition of basolateral Kir4.1/5.1 and Kir4.1 channels in the cortical collecting duct by dopamine. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1277–F1287, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00363.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaika O, Palygin O, Tomilin V, Mamenko M, Staruschenko A, Pochynyuk O. Insulin and IGF-1 activate Kir4.1/5.1 channels in cortical collecting duct principal cells to control basolateral membrane voltage. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F311–F321, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00436.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramos HE, da Silva MR, Carré A, Silva JC Jr, Paninka RM, Oliveira TL, Tron E, Castanet M, Polak M. Molecular insights into the possible role of Kir4.1 and Kir5.1 in thyroid hormone biosynthesis. Horm Res Paediatr 83: 141–147, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000369251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Di Palma T, Conti A, de Cristofaro T, Scala S, Nitsch L, Zannini M. Identification of novel Pax8 targets in FRTL-5 thyroid cells by gene silencing and expression microarray analysis. PLoS One 6: e25162, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lachheb S, Cluzeaud F, Bens M, Genete M, Hibino H, Lourdel S, Kurachi Y, Vandewalle A, Teulon J, Paulais M. Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channel forms the major K+ channel in the basolateral membrane of mouse renal collecting duct principal cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1398–F1407, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00288.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isaeva E, Bohovyk R, Fedoriuk M, Shalygin A, Klemens CA, Zietara A, Levchenko V, Denton JS, Staruschenko A, Palygin O. Crosstalk between epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) and basolateral potassium channels (Kir 4.1/Kir 5.1) in the cortical collecting duct. Br J Pharmacol 179: 2953–2968, 2022. doi: 10.1111/bph.15779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ou M, Kuo FS, Chen X, Kahanovitch U, Olsen ML, Du G, Mulkey DK. Isoflurane inhibits a Kir4.1/5.1-like conductance in neonatal rat brainstem astrocytes and recombinant Kir4.1/5.1 channels in a heterologous expression system. J Neurophysiol 124: 740–749, 2020. doi: 10.1152/jn.00358.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salvatore L, D'Adamo MC, Polishchuk R, Salmona M, Pessia M. Localization and age-dependent expression of the inward rectifier K+ channel subunit Kir 5.1 in a mammalian reproductive system. FEBS Lett 449: 146–152, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lv J, Fu X, Li Y, Hong G, Li P, Lin J, Xun Y, Fang L, Weng W, Yue R, Li GL, Guan B, Li H, Huang Y, Chai R. Deletion of Kcnj16 in mice does not alter auditory function. Front Cell Dev Biol 9: 630361, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.630361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hibino H, Higashi-Shingai K, Fujita A, Iwai K, Ishii M, Kurachi Y. Expression of an inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir5.1, in specific types of fibrocytes in the cochlear lateral wall suggests its functional importance in the establishment of endocochlear potential. Eur J Neurosci 19: 76–84, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu Y, McKenna E, Figueroa DJ, Blevins R, Austin CP, Bennett PB, Swanson R. The human inward rectifier K(+) channel subunit kir5.1 (KCNJ16) maps to chromosome 17q25 and is expressed in kidney and pancreas. Cytogenet Cell Genet 90: 60–63, 2000. doi: 10.1159/000015662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franze K, Grosche J, Skatchkov SN, Schinkinger S, Foja C, Schild D, Uckermann O, Travis K, Reichenbach A, Guck J. Muller cells are living optical fibers in the vertebrate retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 8287–8292, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611180104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coughlin BA, Feenstra DJ, Mohr S. Müller cells and diabetic retinopathy. Vision Res 139: 93–100, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bringmann A, Wiedemann P. Müller glial cells in retinal disease. Ophthalmologica 227: 1–19, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000328979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park SJ, Borghuis BG, Rahmani P, Zeng Q, Kim IJ, Demb JB. Function and circuitry of VIP+ interneurons in the mouse retina. J Neurosci 35: 10685–10700, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0222-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ishii M, Fujita A, Iwai K, Kusaka S, Higashi K, Inanobe A, Hibino H, Kurachi Y. Differential expression and distribution of Kir5.1 and Kir4.1 inwardly rectifying K+ channels in retina. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C260–C267, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00560.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stasheff SF. Clinical impact of spontaneous hyperactivity in degenerating retinas: significance for diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment. Front Cell Neurosci 12: 298, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Binder DK, Steinhäuser C. Astrocytes and epilepsy. Neurochem Res 46: 2687–2695, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11064-021-03236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mohapatra DP, Misonou H, Pan SJ, Held JE, Surmeier DJ, Trimmer JS. Regulation of intrinsic excitability in hippocampal neurons by activity-dependent modulation of the KV2.1 potassium channel. Channels (Austin) 3: 46–56, 2009. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.1.7655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu Rev Med 60: 355–366, 2009. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Puissant MM, Mouradian GC Jr, Liu P, Hodges MR. Identifying candidate genes that underlie cellular pH sensitivity in serotonin neurons using transcriptomics: a potential role for Kir5. Front Cell Neurosci 11: 34, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huckstepp RT, Dale N. Redefining the components of central CO2 chemosensitivity–towards a better understanding of mechanism. J Physiol 589: 5561–5579, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Corcoran AE, Hodges MR, Wu Y, Wang W, Wylie CJ, Deneris ES, Richerson GB. Medullary serotonin neurons and central CO2 chemoreception. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 168: 49–58, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Trapp S, Tucker SJ, Gourine AV. Respiratory responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia in mice with genetic ablation of Kir5.1 (Kcnj16). Exp Physiol 96: 451–459, 2011. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gourine AV, Kasymov V, Marina N, Tang F, Figueiredo MF, Lane S, Teschemacher AG, Spyer KM, Deisseroth K, Kasparov S. Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP. Science 329: 571–575, 2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1190721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Souza G, Stornetta RL, Stornetta DS, Abbott SBG, Guyenet PG. Contribution of the retrotrapezoid nucleus and carotid bodies to hypercapnia- and hypoxia-induced arousal from sleep. J Neurosci 39: 9725–9737, 2019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1268-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wenker IC, Kréneisz O, Nishiyama A, Mulkey DK. Astrocytes in the retrotrapezoid nucleus sense H+ by inhibition of a Kir4.1-Kir5.1-like current and may contribute to chemoreception by a purinergic mechanism. J Neurophysiol 104: 3042–3052, 2010. doi: 10.1152/jn.00544.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Patterson KC, Kahanovitch U, Gonçalves CM, Hablitz JJ, Staruschenko A, Mulkey DK, Olsen ML. K(ir) 5.1-dependent CO2/H(+)-sensitive currents contribute to astrocyte heterogeneity across brain regions. Glia 69: 310–325, 2021. doi: 10.1002/glia.23898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schirmer L, Möbius W, Zhao C, Cruz-Herranz A, Ben Haim L, Cordano C, Shiow LR, Kelley KW, Sadowski B, Timmons G, Pröbstel AK, Wright JN, Sin JH, Devereux M, Morrison DE, Chang SM, Sabeur K, Green AJ, Nave KA, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Oligodendrocyte-encoded Kir4.1 function is required for axonal integrity. eLife 7: e36428, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brasko C, Hawkins V, De La Rocha IC, Butt AM. Expression of Kir4.1 and Kir5.1 inwardly rectifying potassium channels in oligodendrocytes, the myelinating cells of the CNS. Brain Struct Funct 222: 41–59, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1199-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Neusch C, Rozengurt N, Jacobs RE, Lester HA, Kofuji P. Kir4.1 potassium channel subunit is crucial for oligodendrocyte development and in vivo myelination. J Neurosci 21: 5429–5438, 2001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05429.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nin F, Yoshida T, Sawamura S, Ogata G, Ota T, Higuchi T, Murakami S, Doi K, Kurachi Y, Hibino H. The unique electrical properties in an extracellular fluid of the mammalian cochlea; their functional roles, homeostatic processes, and pathological significance. Pflugers Arch 468: 1637–1649, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1871-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu W, Zong S, Du P, Zhou P, Li H, Wang E, Xiao H. Role of the stria vascularis in the pathogenesis of sensorineural hearing loss: a narrative review. Front Neurosci 15: 774585, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.774585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Peeleman N, Verdoodt D, Ponsaerts P, Van Rompaey V. On the role of fibrocytes and the extracellular matrix in the physiology and pathophysiology of the spiral ligament. Front Neurol 11: 580639, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.580639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adams JC. Immunocytochemical traits of type IV fibrocytes and their possible relations to cochlear function and pathology. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 10: 369–382, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pan C-C, Chu H-Q, Lai Y-B, Sun Y-B, Du Z-h, Liu Y, Chen J, Tong T, Chen Q-G, Zhou L-Q, Bing D, Tao Y-L. Downregulation of inwardly rectifying potassium channel 5.1 expression in C57BL/6J cochlear lateral wall. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 36: 406–409, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11596-016-1600-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, Bandulik S, Zdebik AA, Reichold M, Tobin J, Lieberer E, Sterner C, Landoure G, Arora R, Sirimanna T, Thompson D, Cross JH, van't HW, Al MO, Tullus K, Yeung S, Anikster Y, Klootwijk E, Hubank M, Dillon MJ, Heitzmann D, Rcos-Burgos M, Knepper MA, Dobbie A, Gahl WA, Warth R, Sheridan E, Kleta R. Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med 360: 1960–1970, 2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Simon DB, Lifton RP. The molecular basis of inherited hypokalemic alkalosis: Bartter’s and Gitelman’s syndromes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 271: F961–F966, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.5.F961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 104: 545–556, 2001. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Castañeda-Bueno M, Ellison DH, Gamba G. Molecular mechanisms for the modulation of blood pressure and potassium homeostasis by the distal convoluted tubule. EMBO Mol Med 14: e14273, 2022. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202114273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wieërs MLAJ, Mulder J, Rotmans JI, Hoorn EJ. Potassium and the kidney: a reciprocal relationship with clinical relevance. Pediatr Nephrol, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05494-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Silic MR, Murata SH, Park SJ, Zhang G. Evolution of inwardly rectifying potassium channels and their gene expression in zebrafish embryos. Dev Dyn 251: 687–713, 2022. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reichold M, Zdebik AA, Lieberer E, Rapedius M, Schmidt K, Bandulik S, Sterner C, Tegtmeier I, Penton D, Baukrowitz T, Hulton SA, Witzgall R, Ben-Zeev B, Howie AJ, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D, Warth R. KCNJ10 gene mutations causing EAST syndrome (epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, and tubulopathy) disrupt channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 14490–14495, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003072107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Scholl UI, Choi M, Liu T, Ramaekers VT, Hausler MG, Grimmer J, Tobe SW, Farhi A, Nelson-Williams C, Lifton RP. Seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance (SeSAME syndrome) caused by mutations in KCNJ10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5842–5847, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Palygin O, Levchenko V, Ilatovskaya DV, Pavlov TS, Pochynyuk OM, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A. Essential role of Kir5.1 channels in renal salt handling and blood pressure control. JCI Insight 2: e92331, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Paulais M, Bloch-Faure M, Picard N, Jacques T, Ramakrishnan SK, Keck M, Sohet F, Eladari D, Houillier P, Lourdel S, Teulon J, Tucker SJ. Renal phenotype in mice lacking the Kir5.1 (Kcnj16) K+ channel subunit contrasts with that observed in SeSAME/EAST syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10361–10366, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101400108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Freudenthal B, Kulaveerasingam D, Lingappa L, Shah MA, Brueton L, Wassmer E, Ognjanovic M, Dorison N, Reichold M, Bockenhauer D, Kleta R, Zdebik AA. KCNJ10 mutations disrupt function in patients with EAST syndrome. Nephron Physiol 119: p40–p48, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000330250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cross JH, Arora R, Heckemann RA, Gunny R, Chong K, Carr L, Baldeweg T, Differ AM, Lench N, Varadkar S, Sirimanna T, Wassmer E, Hulton SA, Ognjanovic M, Ramesh V, Feather S, Kleta R, Hammers A, Bockenhauer D. Neurological features of epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 55: 846–856, 2013. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Celmina M, Micule I, Inashkina I, Audere M, Kuske S, Pereca J, Stavusis J, Pelnena D, Strautmanis J. EAST/SeSAME syndrome: review of the literature and introduction of four new Latvian patients. Clin Genet 95: 63–78, 2019. doi: 10.1111/cge.13374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Su XT, Wang WH. The expression, regulation, and function of Kir4.1 (Kcnj10) in the mammalian kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 311: F12–F15, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00112.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kofuji P, Ceelen P, Zahs KR, Surbeck LW, Lester HA, Newman EA. Genetic inactivation of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir4.1 subunit) in mice: phenotypic impact in retina. J Neurosci 20: 5733–5740, 2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05733.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhang C, Wang L, Zhang J, Su X-T, Lin D-H, Scholl UI, Giebisch G, Lifton RP, Wang W-H. KCNJ10 determines the expression of the apical Na-Cl cotransporter (NCC) in the early distal convoluted tubule (DCT1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 11864–11869, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411705111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Juang JM, Lu TP, Lai LC, Ho CC, Liu YB, Tsai CT, Lin LY, Yu CC, Chen WJ, Chiang FT, Yeh SF, Lai LP, Chuang EY, Lin JL. Disease-targeted sequencing of ion channel genes identifies de novo mutations in patients with non-familial Brugada syndrome. Sci Rep 4: 6733, 2014. doi: 10.1038/srep06733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Demirkan A, Henneman P, Verhoeven A, Dharuri H, Amin N, van Klinken JB, Karssen LC, de Vries B, Meissner A, Göraler S, van den Maagdenberg AMJM, Deelder AM, C 't Hoen PA, van Duijn CM, van Dijk KW. Insight in genome-wide association of metabolite quantitative traits by exome sequence analyses. PLoS Genet 11: e1004835, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schlingmann KP, Renigunta A, Hoorn EJ, Forst AL, Renigunta V, Atanasov V, Mahendran S, Barakat TS, Gillion V, Godefroid N, Brooks AS, Lugtenberg D, Lake J, Debaix H, Rudin C, Knebelmann B, Tellier S, Rousset-Rouvière C, Viering D, de Baaij JHF, Weber S, Palygin O, Staruschenko A, Kleta R, Houillier P, Bockenhauer D, Devuyst O, Vargas-Poussou R, Warth R, Zdebik AA, Konrad M. Defects in KCNJ16 cause a novel tubulopathy with hypokalemia, salt wasting, disturbed acid-base homeostasis, and sensorineural deafness. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 1498–1512, 2021. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020111587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hansen SB, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature 477: 495–498, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Manis AD, Palygin O, Khedr S, Levchenko V, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A. Relationship between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and renal Kir5.1 channels. Clin Sci (Lond) 133: 2449–2461, 2019. doi: 10.1042/CS20190876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Puissant MM, Muere C, Levchenko V, Manis AD, Martino P, Forster HV, Palygin O, Staruschenko A, Hodges MR. Genetic mutation of Kcnj16 identifies Kir5.1-containing channels as key regulators of acute and chronic pH homeostasis. FASEB J 33: 5067–5075, 2019. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802257R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Webb BD, Hotchkiss H, Prasun P, Gelb BD, Satlin L. Biallelic loss-of-function variants in KCNJ16 presenting with hypokalemic metabolic acidosis. Eur J Hum Genet 29: 1566–1569, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00883-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Neubauer J, Forst AL, Warth R, Both CP, Haas C, Thomas J. Genetic variants in eleven central and peripheral chemoreceptor genes in sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatr Res, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41390-021-01899-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Casamassima M, D'Adamo MC, Pessia M, Tucker SJ. Identification of a heteromeric interaction that influences the rectification, gating, and pH sensitivity of Kir4.1/Kir5.1 potassium channels. J Biol Chem 278: 43533–43540, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rapp JP. Dahl salt-susceptible and salt-resistant rats. A review. Hypertension 4: 753–763, 1982. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pickkers P, Garcha RS, Schachter M, Smits P, Hughes AD. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase accounts for the direct vascular effects of hydrochlorothiazide. Hypertension 33: 1043–1048, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.4.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Brennan TJ, Seeley WW, Kilgard M, Schreiner CE, Tecott LH. Sound-induced seizures in serotonin 5-HT2c receptor mutant mice. Nat Genet 16: 387–390, 1997. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Faingold CL, Randall M, Mhaskar Y, Uteshev VV. Differences in serotonin receptor expression in the brainstem may explain the differential ability of a serotonin agonist to block seizure-induced sudden death in DBA/2 vs. DBA/1 mice. Brain Res 1418: 104–110, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Manis AD, Palygin O, Isaeva E, Levchenko V, LaViolette PS, Pavlov TS, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A. Kcnj16 knockout produces audiogenic seizures in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. JCI Insight 6: e143251, 2021. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.143251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hawkins NA, Nomura T, Duarte S, Barse L, Williams RW, Homanics GE, Mulligan MK, Contractor A, Kearney JA. Gabra2 is a genetic modifier of Dravet syndrome in mice. Mamm Genome 32: 350–363, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00335-021-09877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Nobili L, Proserpio P, Rubboli G, Montano N, Didato G, Tassinari CA. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) and sleep. Sleep Med Rev 15: 237–246, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ficker DM. Sudden unexplained death and injury in epilepsy. Epilepsia 41, Suppl 2: S7–S12, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nashef L, So EL, Ryvlin P, Tomson T. Unifying the definitions of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia 53: 227–233, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Richerson GB, Buchanan GF. The serotonin axis: shared mechanisms in seizures, depression, and SUDEP. Epilepsia 52, Suppl 1: 28–38, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ryvlin P, Nashef L, Lhatoo SD, Bateman LM, Bird J, Bleasel A, Boon P, Crespel A, Dworetzky BA, Høgenhaven H, Lerche H, Maillard L, Malter MP, Marchal C, Murthy JM, Nitsche M, Pataraia E, Rabben T, Rheims S, Sadzot B, Schulze-Bonhage A, Seyal M, So EL, Spitz M, Szucs A, Tan M, Tao JX, Tomson T. Incidence and mechanisms of cardiorespiratory arrests in epilepsy monitoring units (MORTEMUS): a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 12: 966–977, 2013. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Monté CP, Arends JB, Tan IY, Aldenkamp AP, Limburg M, de Krom MC. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy patients: risk factors. A systematic review. Seizure 16: 1–7, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. McClenahan SJ, Kent CN, Kharade SV, Isaeva E, Williams JC, Han C, Terker A, Gresham R 3rd, Lazarenko RM, Days EL, Romaine IM, Bauer JA, Boutaud O, Sulikowski GA, Harris R, Weaver CD, Staruschenko A, Lindsley CW, Denton JS. VU6036720: The first potent and selective in vitro inhibitor of heteromeric Kir4.1/5.1 inward rectifier potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol 101: 357–370, 2022. doi: 10.1124/molpharm.121.000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Weaver CD, Denton JS. Next-generation inward rectifier potassium channel modulators: discovery and molecular pharmacology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 320: C1125–C1140, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00548.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kharade SV, Kurata H, Bender AM, Blobaum AL, Figueroa EE, Duran A, Kramer M, Days E, Vinson P, Flores D, Satlin LM, Meiler J, Weaver CD, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR, Denton JS. Discovery, characterization, and effects on renal fluid and electrolyte excretion of the Kir4.1 potassium channel pore blocker, VU0134992. Mol Pharmacol 94: 926–937, 2018. doi: 10.1124/mol.118.112359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Swale DR, Kurata H, Kharade SV, Sheehan J, Raphemot R, Voigtritter KR, Figueroa EE, Meiler J, Blobaum AL, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR, Denton JS. ML418: the first selective, sub-micromolar pore blocker of Kir7.1 potassium channels. ACS Chem Neurosci 7: 1013–1023, 2016. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]