Keywords: heat therapy, intermittent claudication, peripheral artery disease

Abstract

Few noninvasive therapies currently exist to improve functional capacity in people with lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD). The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that unsupervised, home-based leg heat therapy (HT) using water-circulating trousers perfused with warm water would improve walking performance in patients with PAD. Patients with symptomatic PAD were randomized into either leg HT (n = 18) or a sham treatment (n = 16). Patients were provided with water-circulating trousers and a portable pump and were asked to apply the therapy daily (7 days/wk, 90 min/session) for 8 wk. The primary study outcome was the change from baseline in 6-min walk distance at 8-wk follow-up. Secondary outcomes included the claudication onset-time, peak walking time, peak pulmonary oxygen consumption and peak blood pressure during a graded treadmill test, resting blood pressure, the ankle-brachial index, postocclusive reactive hyperemia in the calf, cutaneous microvascular reactivity, and perceived quality of life. Of the 34 participants randomized, 29 completed the 8-wk follow-up. The change in 6-min walk distance at the 8-wk follow-up was significantly higher (P = 0.029) in the group exposed to HT than in the sham-treated group (Sham: median: −0.9; 25%, 75% percentiles: −5.8, 14.3; HT: median: 21.3; 25%, 75% percentiles: 10.1, 42.4, P = 0.029). There were no significant differences in secondary outcomes between the HT and sham group at 8-wk follow-up. The results of this pilot study indicate that unsupervised, home-based leg HT is safe, well-tolerated, and elicits a clinically meaningful improvement in walking tolerance in patients with symptomatic PAD.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This is the first sham-controlled trial to examine the effects of home-based leg heat therapy (HT) on walking performance in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD). We demonstrate that unsupervised HT using water-circulating trousers is safe, well-tolerated, and elicits meaningful changes in walking ability in patients with symptomatic PAD. This home-based treatment option is practical, painless, and may be a feasible adjunctive therapy to counteract the decline in lower extremity physical function in patients with PAD.

INTRODUCTION

Lower-extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis that is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1), diminished quality of life (2), and impaired physical functioning (3). Referral to a supervised exercise training (SET) program remains the most effective noninterventional therapy to restore lower-extremity function in PAD (4). However, SET is rarely prescribed (5), very few structured programs are available (6), and patients often refuse to participate because of comorbidities, the inconvenience of traveling to a clinical exercise facility, and presence of leg pain during high-intensity walking (7, 8). Home-based exercise programs may be an effective alternative to SET, but only if patients visit the medical center regularly to meet with a coach (9, 10). As a consequence of these multiple barriers, the vast majority of patients with PAD fail to engage in structured exercise programs (11) and experience an accelerated decline in walking ability (12). A pressing need remains for novel therapies that are widely available, painless, and amenable for application in an unsupervised setting.

A growing number of studies indicate that regular exposure to heat stress is a potent noninvasive therapeutic tool to improve cardiovascular health in patients with overt cardiovascular disease (13–17) and endocrine disorders (18, 19). Foundational studies conducted by Tei and coworkers (20, 21) in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia revealed that repeated episodic exposure to heat stress using a far-infrared dry sauna system increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) protein expression, blood flow, and capillary density in the ischemic hindlimb. The same group demonstrated in subsequent clinical studies that daily treatment with far infrared sauna for 6–10 wk reduced leg symptoms, improved 6-min walk distance, and increased serum nitrate and nitrite levels in patients with PAD (22, 23). More recently, Akerman et al. (24) showed that spa bathing combined with calisthenics for 12 wk lowered mean arterial blood pressure and improved 6-min walk distance in patients with symptomatic PAD. Although encouraging, these previous studies did not include a sham-treated group and utilized heating modalities (sauna and spa) that are largely inaccessible to most patients with PAD. Indeed, the availability and accessibility to fitness centers and other facilities that offer sauna and hydrotherapy options to people with disabilities are poor (25).

One alternative heat therapy (HT) solution that is practical for home use and applicable to individuals with restricted locomotion is the use of water-circulating garments (26–28). These garments are made of a tight-fitting elastic fabric and have an extensive network of tubing sewn onto the lining. With the aid of a portable pump, heated water is circulated through the tubing, enabling an increase in the temperature of a limb or body segment (29). We recently demonstrated that a single 90-min session of leg HT using water-circulating trousers perfused with heated water elicited a marked increase in leg blood flow and a reduction in blood pressure in patients with symptomatic PAD (28). We also reported that leg HT in a supervised setting (3 times weekly for 90 min) promoted a significant increase in perceived physical functioning when compared with a sham treatment in patients with symptomatic PAD (26). It remains unclear, nonetheless, whether unsupervised, home-based leg HT is feasible, safe, and has a meaningful impact on walking performance in people with PAD.

Accordingly, the main goal of this randomized, sham-controlled, pilot clinical trial was to establish the effects of 8 wk of home-based leg HT on walking performance, vascular function, and perceived quality of life in patients with symptomatic PAD. Individuals randomized to the leg HT group were asked to apply the treatment daily for 90 min using water-circulating trousers perfused with water heated to 43°C (27). In the sham group, water at 33°C was circulated through the trousers (28). The primary study outcome was the change in 6-min walk distance from baseline to 8 wk. We hypothesized that home-based leg HT would be safe, well-tolerated, and would improve 6-min walk distance at 8-wk follow-up, compared with the sham treatment. Secondary outcomes included the claudication onset-time (COT), peak walking time (PWT), peak pulmonary oxygen consumption (V̇o2peak) and peak blood pressure during a graded treadmill test, resting blood pressure, the ankle-brachial index (ABI), reactive hyperemia in the calf, cutaneous microvascular reactivity during local heating, and perceived quality of life (QOL). Building upon previous findings that leg heating enhances blood flow and shear rate in the popliteal artery in patients with PAD (28, 30), our secondary hypothesis was that repeated HT for 8 wk would enhance leg vascular function. In addition, in an exploratory experiment, we tested whether serum from patients treated with HT would augment endothelial cell tube formation in a Matrigel assay relative to the control group, as demonstrated previously in young individuals (31).

METHODS

Trial Overview

The study was a parallel-design, single-blinded, randomized clinical trial performed at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana. Patients with symptomatic PAD were randomized to either a sham treatment or HT. The home-based intervention consisted of daily (90 min/day) treatment sessions for 8 consecutive weeks. The first participant was randomized on January 14, 2019. Final follow-up occurred on June 21, 2021. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University (No. 1801755556A009), and registered with the United States Library of Medicine on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03763331). Written, informed consent was obtained, and all procedures adhere to the requirements of the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR, Part 46), and support the general ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. An independent clinical research monitor, affiliated with the Indiana Clinical Translational Science Institute (CTSI), performed in-depth routine evaluations to ensure the trial was conducted, recorded, and reported in accordance with the protocol, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and good clinical practice (GCP). In addition, a data safety and monitoring board periodically reviewed the study progress and safety data. Data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request.

Participants

Participants were recruited by referral from the peripheral vascular disease clinic at the Department of Vascular Surgery at Indiana University’s Methodist Hospital, the Non-Invasive Vascular Laboratory at Methodist Hospital, and direct participant contact by the Indiana CTSI Research Network (ResNet) office. The inclusion criteria were age between 40 and 80 yr, an ABI below 0.90 in either leg, and claudication pain during exercise in one or both legs for greater than 6 mo before enrolling in the study. The exclusion criteria were 1) a hemoglobin A1C value above 8.5% within 3 mo of screening; 2) use of a walking aid or wheelchair; 3) critical limb ischemia; 4) impaired thermal sensation in the legs; 5) exercise-limiting comorbidity; 6) chronic heart failure (classes C and stage D); 7) a body mass index >35, 8) inability to fit into water-circulating trousers; 9) open wounds or ulcers on the lower extremity; 10) prior amputation; 11) lower extremity revascularization, major orthopedic surgery, cardiovascular event, or coronary revascularization in the 3 mo preceding screening; 12) planned revascularization or major surgery; 13) plans to change medical therapy during the duration of the study; 14) active treatment for cancer; 15) chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 by MDRD or Mayo or Cockcroft-Gault formula); 16) HIV positive, active HBV or HCV disease; 17) presence of any clinical condition that made the patient not suitable to participate in the trial; and 18) inability to walk on the treadmill. Patients with cardiovascular or other implants not compatible with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were allowed to participate in the study, but were excluded from undergoing the MRI measurements. The ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier is NCT03763331.

Experimental Protocol

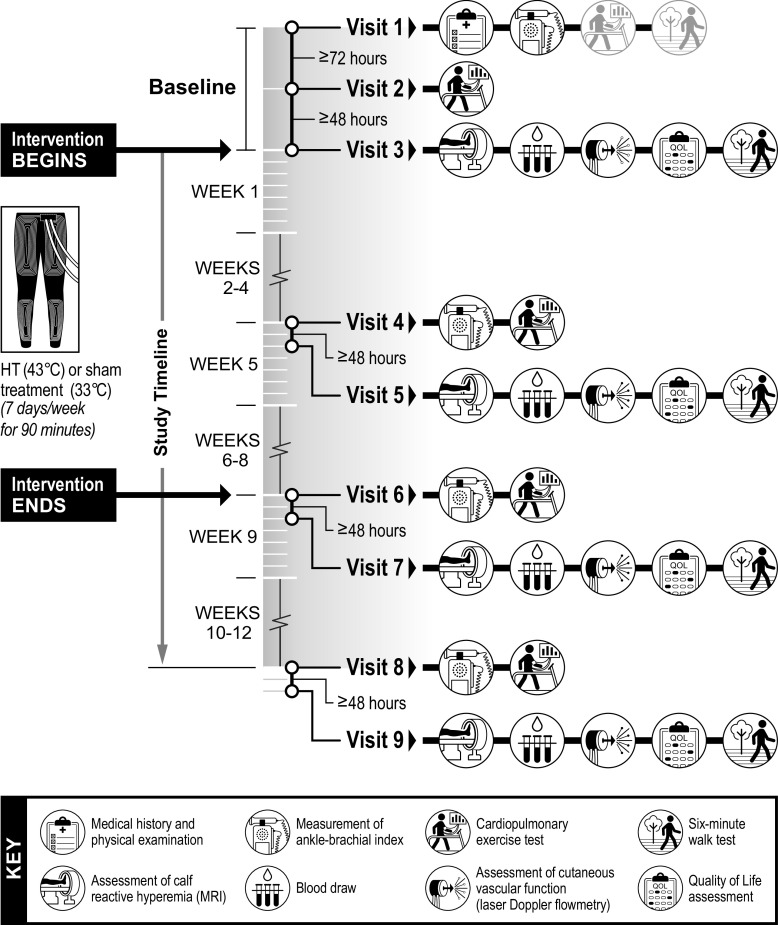

Participants were asked to report to the laboratory for a total of nine experimental visits over the course of the study as detailed in Fig. 1. On visit 1, participants underwent a resting ABI measurement and were familiarized with the symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise test on a treadmill and the 6-min walk test. At least 72 h after visit 1, participants returned for visit 2 and underwent the baseline treadmill cardiopulmonary test. Randomization occurred following completion of visit 2. Visit 3 was conducted at least 48 h after visit 2 and encompassed the following procedures: 1) assessment of reactive hyperemia in the calf using arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI, 2) a blood draw, 3) assessment of cutaneous vascular function using laser-Doppler flowmetry, 4) measurement of blood pressure using an automated BP device, 5) QOL testing, and 6) a 6-min walk test. After completion of outcome assessments, participants were familiarized with the treatment they were assigned to by undergoing a 90-min treatment session. Leg skin temperature and intestinal temperature were monitored throughout the session.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the experimental protocol. HT, heat therapy.

Outcomes were reassessed at the halfway point (end of week 4), at the completion of the intervention (end of week 8) and at a follow-up visit, 4 wk after the end of the intervention (week 12) (Fig. 1). To ensure that the chronic rather than the acute effects of HT were investigated, participants were asked to interrupt the treatment 48 h before the outcome sessions. Participants were permitted to take their usual morning medication, but were asked to fast overnight and refrain from exercise and alcohol for 24 h before attending all experimental sessions. Active smokers were also asked to refrain from cigarette smoking for at least 4 h before the experiments to minimize the acute effects of cigarette smoking on cardiovascular function (32).

Randomization

Patients were randomized (blocked and stratified by sex) using assignments generated from PROC PLAN in SAS Version 9.4 by the study statistician into one of two groups: those receiving HT or those receiving the sham treatment. Participants were informed that there were two different categories of HT, “low heat” and “high heat,” and that both might be beneficial for claudication symptoms.

Interventions

Patients in both groups were provided with identical water-circulating trousers (Med-Eng, Ottawa, ON, Canada) and a portable heating pump (Aqua Relief Systems, Akron, OH), and were instructed on how to operate the equipment. The pump given to participants in the HT group was adjusted to circulate water at 43°C through the trousers, with the goal of increasing leg skin temperature to ∼37°C–38°C (27). The pump given to patients in the sham group was adjusted to circulate water at 33°C, because this temperature is perceived as slightly warm but it is not sufficient to provoke changes in core body temperature or hemodynamic adjustments associated with leg HT (28, 33). As described previously (26), this sham intervention was designed to account for psychosocial factors that promote placebo effects. Similar to other equipment utilized in physical and rehabilitation medicine, HT devices likely elicit a higher placebo response than placebo pills, particularly when considering subjective outcomes (34).

Participants were asked to apply the therapy daily for 90 min while seated or in a semi-recumbent position as described previously (28, 33). Patients in both groups received a logbook to record their sessions. The study coordinator called patients weekly to record the dates and times in which the treatment was applied and to ask about the occurrence of symptoms and adverse reactions to the therapy. Participants that failed to complete three consecutive treatment sessions or a total of eight sessions throughout the intervention were deemed noncompliant and were excluded from the study.

Outcome Measures

Six-minute walk test (primary outcome).

The 6-min walk test was conducted in accordance with the American Thoracic Society guidelines (35). Participants were instructed to walk as far as possible for 6 min along a 100-ft corridor. The length of the corridor was marked every 10 ft with tape and the turnaround points were marked with a cone. Standardized phrases for encouragement were used during the test. We recently reported that the test-retest reliability of the 6-min walk test performed at two different experimental visits was excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.96) among participants with symptomatic PAD (33). Performance on the 6-min walk test correlates closely with physical activity levels in the community (36) and is linked to cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality risk (37) and the rate of mobility loss (12, 38) in patients with PAD.

Cardiopulmonary exercise test.

The cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) was performed on a motorized treadmill (Pro 27, Woodway, St. Paul, MN) following the Gardner–Skinner protocol, as described previously by our group (27). A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was registered continuously. Blood pressure was measured in the left arm using a stethoscope and sphygmomanometer every 2 min during exercise and for 10 min during recovery. Expired respiratory gases were collected breath-by-breath via a facemask attached to a gas analyzer (MedGraphics, CardiO2, and CPX/D system using Breeze EX Software, 142090-001, ReVia; MGC Diagnostics, St. Paul, MN). Participants received standardized instructions and were asked to indicate when they first began to feel leg pain with a “thumbs up” signal (defined as COT), and then give a “thumbs down” signal when they could no longer continue with the test (defined as PWT). Peak pulmonary oxygen uptake (V̇o2peak) was defined as the average of the last 20 s of exercise. Peak systolic (SBPpeak) and diastolic (DBPpeak) were defined as the last measurement before PWT.

Blood pressure.

Resting systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP), and mean arterial (MAP) blood pressure were defined as the average of 14 consecutive measurements performed over 70 min during the cutaneous thermal hyperemia protocol delineated in Cutaneous vascular function.

Ankle-brachial index.

The ABI was measured following the guidelines of the American Heart Association (39). Patients were allowed to rest for 10 min in the supine position before the measurements. A handheld 5-MHz Doppler ultrasound (Lumeon, McKesson) was used to obtain duplicate measurements of systolic pressures in the right posterior tibial artery, right dorsalis pedis artery, right brachial artery, left posterior tibial artery, left dorsalis pedis artery, and left brachial artery. The ABI of each leg was calculated by dividing the higher of the dorsalis pedis pressure or posterior tibial pressure by the higher of the right or left arm blood pressure (39).

Calf reactive hyperemia.

Imaging was completed on a Siemens 3 Tesla (T) Magnetom Prisma scanner (Siemens AG Healthcare Sector, Erlangen, Germany). Patients were required to rest for at least 10 min in the supine position before being transported to the imaging room on a nonmagnetic gurney. After the patient was passively transferred to the scanner, a cuff (SC12L, Hokanson) was snugly wrapped around the upper thigh and connected to a rapid cuff inflation system (Hokanson E20, Hokanson). A transmit/receive knee coil was placed around the knee of the most symptomatic leg. Postocclusive reactive hyperemia of the calf muscles was assessed using pulsed arterial spin labeling (PASL) MRI. Arterial spin labeled images were acquired using a pulsed ASL pulse sequence with single-shot echo-planar imaging readouts (TR 4,000 ms, TE 14.0 ms, flip angle 90°, FOV 160 mm, and reconstructed voxel dimensions of 2.5 × 2.5 × 10.0 mm). The tagging plane was placed immediately superior to the imaging volume to tag arterial blood entering the calf by inverting the vender’s standard neurologic ASL sequence. After baseline data acquisition for 2 min, the cuff was inflated to suprasystolic values (75 mmHg above brachial SBP, as assessed before scanning). After 5 min of occlusion, the cuff was deflated and the reactive hyperemia was monitored for 10 min. The ASL images were reconstructed and processed in Mat-Lab (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The region of interest (ROI) was manually drawn based on the anatomical reference image to cover the entire muscle region. Time-of-flight images were fitted over perfusion images and the control image was subtracted from the tagged image to quantify skeletal muscle perfusion.

Cutaneous vascular function.

Cutaneous vascular responsiveness to local heating of the skin of the dorsal leg was assessed as described previously (26). Participants rested in a semirecumbent position and were instrumented with two single-point laser-Doppler flowmetry probes (Moor Instruments, Axminster, UK) housed in the center of local heaters (SH02 Skin Heater/Temperature Monitor; Moor Instruments, Axminster, UK). Red blood cell flux, an index of skin blood flow, was recorded for 10 min with skin temperature held constant at 33°C. Next, local skin temperature at each site was raised to 39°C at a rate of 0.1°C/s and maintained for 40 min (40). Finally, local skin temperature was raised to 43.0°C at a rate of 0.1°C/s and maintained at this level for 20 min. Red blood cell flux and the temperature of the skin heaters were recorded at 40 Hz using a data acquisition system (Powerlab and LabChart, ADInstruments). An automated device (Tango+, Suntech Medical) was used to measure SBP and DBP every 5 min. MAP was calculated as DBP plus one-third of the difference between SBP and DBP. Cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) was calculated as red blood cell flux divided by MAP and was normalized as a percentage of maximal vasodilation (CVC%max). In healthy, young volunteers, rapid skin local heating to 39°C at 0.1°C/s produces a hyperemic response that is dependent on nitric oxide (40).

Quality of life.

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36v2) was used to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The SF-36v2 Health Survey was scored using proprietary software (Health Outcomes, Optum). Disease-specific health-related quality of life was assessed using the Vascular Quality of Life (VascuQoL) questionnaire (41). The total VASCUQOL score is the average score of questions answered and ranges from 1 (worst QOL) to 7 (best QOL) (42).

Endothelial tube formation assay.

The goal of this exploratory experiment was to assess the effects of serum collected at baseline and the 8-wk follow up on endothelial cell tube formation as described previously (31). Blood samples were drawn into serum separator tubes (SST) (BD Vacutainer; BD, ON, Canada), allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min, centrifuged at 1,100 g for 10 min (ST16; Thermo Scientific), aliquoted, and placed into a −80°C freezer. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC; Cell Applications, San Diego, CA) were used for the in vitro tube formation assay. Briefly, cells were amplified in endothelial cell growth medium (Cell Applications) for two passages. The tube formation assay was performed in 96-well using Cultrex reduced growth factor basement membrane extract (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Prior to the assay, 96-well plates and pipette tips were chilled at −20°C and the Cultrex gel was thawed in ice at 4°C overnight. Each well was coated with 50 μL of Cultrex and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. During incubation, HUVECs were trypsinized and counted in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were seeded onto the Cultrex-coated wells at 12,000 cells per well. Cells were treated with 10% human serum collected at the baseline and 8-wk follow-up visits. The assay was performed in triplicate. Following a 12-h incubation, cells were imaged at ×25 magnification on a Leica DMi6000 microscope. Tube formation was measured using the angiogenesis analyzer tool on ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) as previously described (43). Total tubule length and number of tubes per field of view are reported.

Sample Size Calculations

The sample size was calculated based on the ability to detect a clinically significant change in 6-min walk distance at the 8-wk follow-up in the HT-treated group as compared with the sham-treated group. Based on prior trials (9, 44), we estimated the standard deviation of change in 6-min walk distance to be 48.69 m and hypothesized that the change in 6-min walk in the sham-treated group would be nonsignificant (0 on average). When the trial was designed, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in the 6-min walk test in patients with PAD was unknown. Perera et al. (45) estimated the magnitude of clinically meaningful change in physical performance measures using data from diverse groups of older participants from observational and intervention studies and reported that a change of 50 m in the 6-min walk distance is considered a substantial meaningful change. Using this effect size [(50 − 0)/48.42 = 1.03], we determined that 16 subjects per group would be needed to detect a clinically meaningful improvement by HT therapy, with a power of 80% and based on a two-sided, two-sample t test with significance level 0.05.

Statistical Analysis

Following the aforementioned power analysis and a priori established statistical analysis plan, the primary analysis focused on the differences between baseline and the 8-wk follow-up. The 4-wk and 12-wk follow-up assessments were deemed secondary and were included in the study design to provide preliminary information about the temporal profile of study outcomes. Baseline characteristics were summarized as means and SDs, frequencies, and percentages, as appropriate. χ2 tests, Fisher’s exact tests, two-sample t tests, or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare continuous and categorical characteristics of participants between the two study groups. Two-sample two-tailed t tests were used to compare changes in each 4-, 8-, and 12-wk outcome at each follow up between HT and control when the differences were normally distributed (normality tested via Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Otherwise, Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used. Group effects estimates are defined as HT – sham, so positive values would mean heat therapy values are higher than sham. For normally distributed changes, the unstandardized difference in changes is reported. For non-normally distributed changes, the Mann–Whitney parameter (∅) is reported. The Mann–Whitney parameter ∅ can be interpreted as probability that the change for a randomly selected individual in the HT group will be larger than the change for a randomly selected individual in the sham group. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals and P values are also provided. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A repeated-measures ANOVA [using AR(1) assumption for correlation over time] was utilized to compare the changes in skin temperature and core temperature between groups during the familiarization session at the end of visit 3. When a significant interaction of time and intervention was detected, Sidak adjustment was used to adjust the group effect P value at each time point. A P < 0.0028 was considered statistically significant for the Sidak-adjusted P value. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and R version 4.1.2 wmwTest function.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

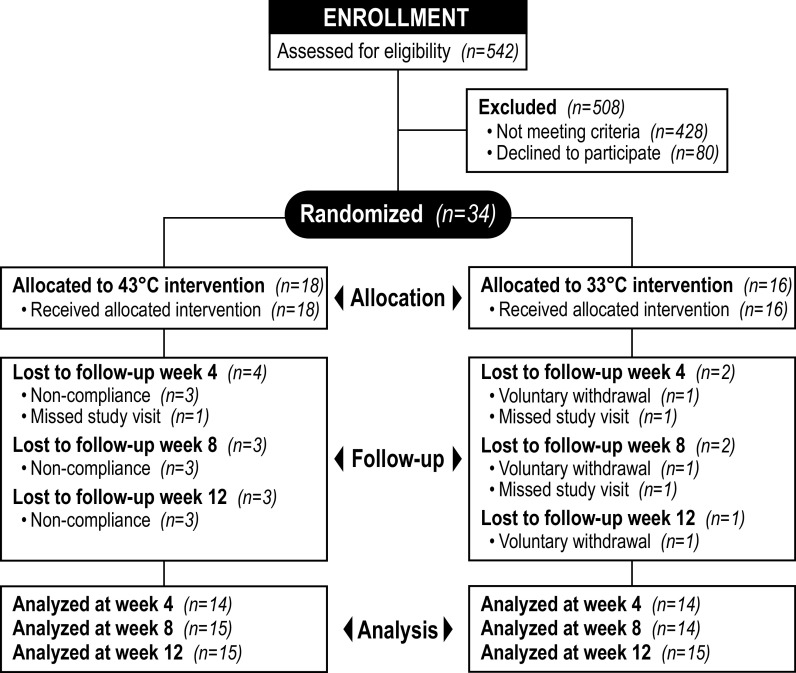

A total of 542 patients were referred and screened for the study. Four hundred twenty-eight participants were deemed ineligible and 80 refused to participate. The remaining 34 patients were randomly allocated to receive HT (n = 18) or the control treatment (n = 16) (Fig. 2). Three participants from the HT group were deemed noncompliant due to missing more than eight treatments. One participant in the control group voluntarily withdrew from the study after ∼4 wk of treatment. Another participant in the control group completed the treatment protocol but was unable to complete the 8-wk follow-up visit due to COVID-19 safety concerns. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants that completed the 8-wk intervention are shown in Table 1. Patients in the sham-treated group were older (P = 0.04) when compared with the HT group. Other baseline characteristics were comparable between groups (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of study enrollment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and data analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with PAD that completed the 8-wk intervention

| Variables | All Participants | Sham | Heat Therapy | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 30 | 15 | 15 | |

| Age yr | 65.93 ± 7.99 | 68.93 ± 5.79 | 62.93 ± 8.92 | 0.0373① |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.6817③ | |||

| Male | 22 (73.33) | 12 (80.00) | 10 (66.67) | |

| Female | 8 (26.67) | 3 (20.00) | 5 (33.33) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.6817③ | |||

| African American | 8 (26.67) | 3 (20.00) | 5 (33.33) | |

| White | 22 (73.33) | 12 (80.00) | 10 (66.67) | |

| Height, cm | 174.27 ± 9.23 | 174.87 ± 10.68 | 173.67 ± 7.86 | 0.7286① |

| Weight, kg | 86.55 ± 19.69 | 85.91 ± 17.35 | 87.20 ± 22.39 | 0.8609① |

| Body mass index | 28.30 ± 4.98 | 27.89 ± 3.83 | 28.70 ± 6.04 | 0.6655① |

| Ankle-brachial index | ||||

| Most affected leg | 0.67 ± 0.12 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.68 ± 0.13 | 0.7721① |

| Other leg | 0.90 ± 0.19 | 0.89 ± 0.21 | 0.90 ± 0.17 | 0.8820① |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.6051③ | |||

| Never smoked | 2 (6.67) | 2 (13.33) | ||

| Current smoker | 10 (33.33) | 5 (33.33) | 5 (33.33) | |

| Past smoker | 18 (60.00) | 10 (66.67) | 8 (53.33) | |

| Diabetes I, n (%) | 1.0000③ | |||

| No | 27 (90.00) | 13 (86.67) | 14 (93.33) | |

| Yes | 3 (10.00) | 2 (13.33) | 1 (6.67) | |

| Diabetes II, n (%) | 0.3295③ | |||

| No | 25 (83.33) | 11 (73.33) | 14 (93.33) | |

| Yes | 5 (16.67) | 4 (26.67) | 1 (6.67) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1.0000③ | |||

| No | 7 (23.33) | 3 (20.00) | 4 (26.67) | |

| Yes | 23 (76.67) | 12 (80.00) | 11 (73.33) | |

| Current statin use, n (%) | 0.4270③ | |||

| No | 9 (30.00) | 3 (20.00) | 6 (40.00) | |

| Yes | 21 (70.00) | 12 (80.00) | 9 (60.00) | |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 111.14 ± 26.54 | 120.93 ± 32.36 | 102.00 ± 15.85 | 0.0531① |

Values are means ± SD or n (%); n, number of participants. PAD, peripheral artery disease. Two-sample t tests (①), Wilcoxon rank sum tests χ2 tests (②), and Fisher’s exact tests (③) were used to compare continuous and categorical characteristics of participants between the two study groups.

Acute Responses to Leg HT

To characterize the heating stimulus, thermoregulatory responses to HT and the sham treatment were assessed during a single 90-min familiarization session at the end of visit 3. Perfusion of the trousers with water at 43°C for 90 min increased leg skin temperature to 38.3 ± 0.7°C (data not shown). In the sham-treated group, average leg skin temperature was 33.9 ± 0.6°C at the end of the session. As expected, the change from baseline in leg skin temperature was significantly greater in the HT group when compared with the sham group at 90 min (P < 0.01). The change from baseline to 90 min in core temperature did not differ between the sham and HT groups (Sham: 0.3 ± 0.9 vs. HT: 0.4 ± 0.4°C, P = 0.54).

Adverse Events

There were nine adverse events in the study. Five events occurred before group allocation and included: hallus valgus correction surgery (n = 1), ureterolithiasis (n = 1), worsening of arterial ischemia (n = 1), asymptomatic atrial fibrillation during the baseline treadmill test (n = 1), and hypotension during recovery from the baseline treadmill test (n = 1). The four events that occurred during the intervention were: 1) supraventricular tachycardia at the onset of treadmill test (n = 1, HT group), 2) a fall during the 6-min walk test (n = 1, HT group), 3) a knee injury (n = 1, HT group) and, 4) transient mild leg skin irritation (n = 1, HT group). In the latter case, the participant reported increased local sensation of warmth in the lateral left thigh after ∼4 wk of treatment and was advised to cover the affected area with medical gauze. The irritation resolved by the next day and did not interfere with the continuation of the HT. There were no serious adverse events related to the interventions.

Intervention Adherence

Patients were asked to document the dates and duration of each treatment session on a logbook and share the records with the study coordinator on weekly phone calls. When considering all participants, including the three individuals who were deemed noncompliant and excluded for the study, the estimated adherence to the prescribed regimen was significantly higher in the sham-treated group as compared with the HT group (Sham: 97 ± 5% vs. HT: 92 ± 9%, P = 0.02). Conversely, the adherence to the treatment was comparable between groups when taking into account only the participants that completed the 8-wk intervention (Sham: 97 ± 5% vs. HT: 96 ± 4%, P = 0.14).

Primary Outcome

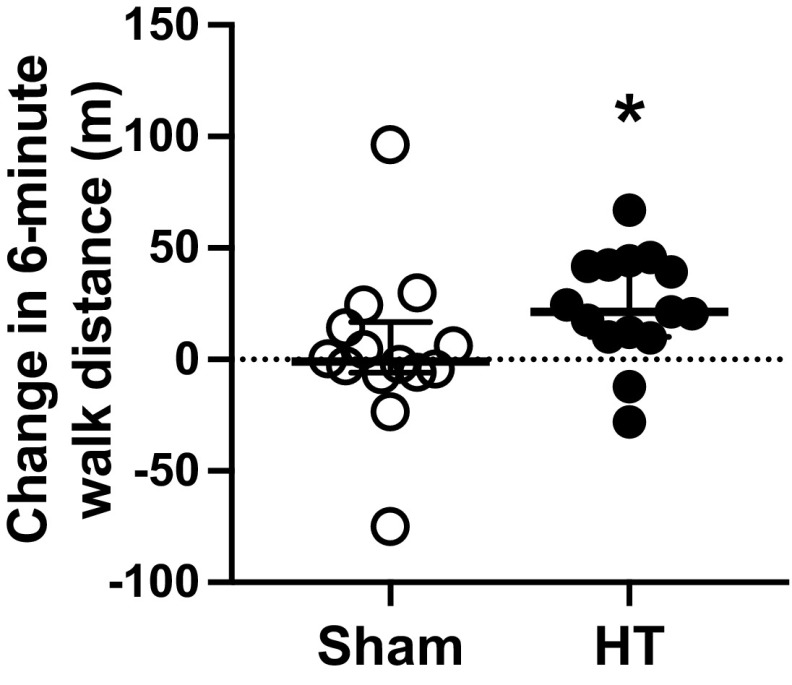

At baseline, 6-min walk distance was similar between the sham and HT groups (Sham: 396 ± 66 vs. HT: 368 ± 89 m, P = 0.34). At the 4-wk follow-up, there was no significant difference in the change from baseline in the 6-min walk distance between groups (Sham: 7.9 ± 35.0 vs. HT: 18.1 ± 32.5 m; between-group change: 10.2 m [95% CI, −17.1 to 37.6], P = 0.45). As shown in Fig. 3, the change in 6-min walk distance from baseline to the 8-wk follow-up was significantly higher (P = 0.029) in the group exposed to HT (median: 21.3; 25%, 75% percentiles: 10.1, 42.4) as compared with the control group (median: −0.9; 25%, 75% percentiles: −5.8, 14.3). One month after the completion of the treatment (i.e., at the 12-wk follow-up), the changes in 6-min walk distance in the HT group were greater, albeit not statistically significant (P = 0.09), when compared with the sham group (Sham: 0.2 ± 42.5 vs. HT: 25.0 ± 35.5 m; between-group change: 24.9 m [95% CI, −4.4 to 54.1]).

Figure 3.

Individual responses, median, and interquartile range of changes in 6-min walk distance from baseline to the 8-wk follow-up in the sham-treated group (n = 14, open circles) and the individuals exposed to heat therapy (HT; n = 15, closed circles). Data were compared between groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, since the data distribution was non-normal. *P < 0.05 Sham vs. HT.

Secondary Outcomes

Table 2 displays the responses to the treadmill cardiopulmonary exercise test. Treatment with HT had no effect on COT, PWT, V̇o2peak, SBPpeak, and DBPpeak, when compared with the sham treatment. The changes in hemodynamic and microvascular reactivity outcomes were also similar between groups (Table 3). The changes in the scores of the SF-36v2 and VascuQoL questionnaires are presented in Table 4. At the 4-wk follow-up, the sham-treated group displayed a greater change in the General Health subscale of the SF-36v2 questionnaire when compared with the HT group (Sham: 11.4 ± 11.1 vs. HT: 1.3 ± 11; between-group change: −10 [95% CI, −18.8 to −1.3], P = 0.03). There were no other statistically significant differences between the HT and sham group at 4-wk, 8-wk, and 12-wk follow-up.

Table 2.

Responses to the treadmill cardiopulmonary exercise test in the sham-treated group and the group exposed to leg HT at baseline and at 4-, 8-, and 12-wk follow-ups

| Outcomes | Sham |

Heat Therapy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | Group Effect Estimate* | (95% CI) | P value | |||

| COT, s | |||||||

| Baseline | 249.7 (178.9) | 15 | 202.5 (155.0) | 15 | −47.2 | (−172.4, 78.0) | 0.4462① |

| Δ4 wk | −6.1 (185.6) | 14 | 45.4 (84.7) | 14 | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.7) | 0.5972② |

| Δ8 wk | 12.3 (210.7) | 14 | 69.8 (119.3) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.7107② |

| Δ12 wk | −3.7 (191.0) | 13 | 47.0 (68.0) | 14 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8271② |

| PWT, s | |||||||

| Baseline | 508.0 (249.1) | 15 | 452.5 (299.8) | 15 | −55.5 | (−261.6, 150.7) | 0.5859① |

| Δ4 wk | 41.2 (155.7) | 14 | 67.1 (67.6) | 14 | 25.9 | (−69.5, 121.3) | 0.5747① |

| Δ8 wk | 61.5 (111.2) | 14 | 109.5 (85.4) | 15 | 48.0 | (−27.2, 123.3) | 0.2013① |

| Δ12 wk | 16.8 (82.3) | 13 | 84.3 (103.4) | 14 | 0.7 | (0.4, 0.8) | 0.1523② |

| SBPpeak, mmHg | |||||||

| Baseline | 176.5 (23.6) | 15 | 178.0 (31.7) | 15 | 1.5 | (−19.4, 22.4) | 0.8868① |

| Δ4 wk | 8.6 (33.0) | 14 | −6.0 (22.4) | 14 | 0.3 | (0.1, 0.5) | 0.0560② |

| Δ8 wk | 5.1 (23.0) | 14 | 2.3 (24.9) | 15 | −2.9 | (−21.2, 15.4) | 0.7497① |

| Δ12 wk | 4.9 (16.5) | 13 | −1.1 (33.8) | 14 | −6.1 | (−27.3, 15.1) | 0.5565① |

| DBPpeak, mmHg | |||||||

| Baseline | 80.0 (7.1) | 15 | 84.8 (9.3) | 15 | 4.8 | (−1.4, 11.0) | 0.1235① |

| Δ4 wk | −1.6 (9.5) | 14 | −3.3 (7.5) | 14 | −1.7 | (−8.3, 4.9) | 0.5989① |

| Δ8 wk | −1.6 (8.3) | 14 | −1.1 (7.6) | 15 | 0.5 | (−5.5, 6.5) | 0.8649① |

| Δ12 wk | −3.7 (6.6) | 13 | −1.0 (11.3) | 14 | 2.7 | (−4.7, 10.1) | 0.4620① |

| V̇o2peak, mL/min | |||||||

| Baseline | 1,099.9 (304.6) | 14 | 1,158.2 (566.9) | 15 | 58.3 | (−289.3, 405.8) | 0.7312① |

| Δ4 wk | 60.8 (173.5) | 13 | 85.7 (208.5) | 14 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.7524② |

| Δ8 wk | 12.2 (103.6) | 13 | 73.7 (228.4) | 15 | 61.6 | (−75.2, 198.4) | 0.3590① |

| Δ12 wk | −52.7 (114.1) | 13 | 48.9 (226.6) | 14 | 101.6 | (−41.1, 244.4) | 0.1529① |

| V̇o2peak, mL/kg/min | |||||||

| Baseline | 13.0 (2.9) | 14 | 13.2 (4.8) | 15 | 0.2 | (−2.8, 3.3) | 0.8822① |

| Δ4 wk | 0.7 (2.3) | 13 | 0.9 (2.1) | 14 | 0.2 | (−1.5, 1.9) | 0.8203① |

| Δ8 wk | (1.3) | 13 | 0.5 (2.4) | 15 | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.8) | 0.5960② |

| Δ12 wk | −0.6 (1.3) | 13 | 0.3 (2.5) | 14 | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.8) | 0.2067② |

Values are means (SD); n, number of participants. COT, claudication onset time; HT, heat therapy; PWT, peak walking time; SBPpeak, peak systolic pressure; DBPpeak, peak diastolic pressure; V̇o2peak, peak pulmonary oxygen uptake.

Two-sample two-tailed t tests (①) were used to compare changes between HT and sham at each follow-up when the differences were normally distributed (normality tested via Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Otherwise, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (②) were used. Group effects were estimated by the difference in changes for normally distributed changes and the Mann–Whitney parameter () for non-normally distributed changes.

Table 3.

The ABI, resting blood pressure, cutaneous vascular responsiveness, and reactive hyperemia of the calf muscles in the sham-treated group and the HT group at baseline and at 4-wk, 8-wk, and 12-wk follow-ups

| Outcomes | Sham |

Heat Therapy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | Group Effect Estimate* | (95% CI) | P value | |||

| ABI—Most symptomatic leg | |||||||

| Baseline | 0.7 (0.1) | 15 | 0.7 (0.1) | 15 | 0.1 | (−0.1, 0.1) | 0.7721① |

| Δ4 wk | 0.0 (0.1) | 14 | 0.0 (0.1) | 14 | −0.0 | (−0.1, 0.0) | 0.8838① |

| Δ8 wk | −0.0 (0.1) | 14 | 0.0 (0.1) | 15 | 0.0 | (−0.0, 0.1) | 0.3861① |

| Δ12 wk | −0.0 (0.1) | 13 | −0.0 (0.1) | 14 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.9419② |

| ABI—Least symptomatic leg | |||||||

| Baseline | 0.9 (0.2) | 15 | 0.9 (0.2) | 15 | 0.0 | (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.8820① |

| Δ4 wk | −0.0 (0.1) | 14 | −0.0 (0.1) | 13 | −0.0 | (−0.1, 0.1) | 0.7414① |

| Δ8 wk | −0.0 (0.1) | 14 | 0.0 (0.1) | 14 | 0.0 | (−0.0, 0.1) | 0.5453① |

| Δ12 wk | −0.0 (0.1) | 13 | 0.0 (0.1) | 13 | 0.1 | (−0.0, 0.1) | 0.0550① |

| Resting SBP, mmHg | |||||||

| Baseline | 143.7 (9.9) | 15 | 148.1 (17.4) | 15 | 4.4 | (−6.4, 15.1) | 0.4070① |

| Δ4 wk | −0.4 (9.7) | 14 | −3.4 (9.7) | 14 | −3.0 | (−10.5, 4.6) | 0.4244① |

| Δ8 wk | −2.8 (12.1) | 14 | 1.2 (14.3) | 15 | 4.0 | (−6.1, 14.1) | 0.4245① |

| Δ12 wk | −3.6 (12.8) | 15 | −1.1 (8.1) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.7089② |

| Resting DBP, mmHg | |||||||

| Baseline | 77.9 (7.4) | 15 | 85.7 (12.3) | 15 | 0.7 | (0.5, 0.8) | 0.1013② |

| Δ4 wk | −0.2 (9.0) | 14 | −2.2 (5.4) | 14 | −2.0 | (−7.8, 3.7) | 0.4764① |

| Δ8 wk | −1.3 (7.1) | 14 | 0.5 (6.5) | 15 | 1.8 | (−3.4, 7.0) | 0.4883① |

| Δ12 wk | −2.4 (8.6) | 15 | 0.2 (3.8) | 15 | 2.5 | (−2.5, 7.6) | 0.3106① |

| Resting MAP, mmHg | |||||||

| Baseline | 99.8 (6.8) | 15 | 106.5 (11.7) | 15 | 6.7 | (−0.5, 13.9) | 0.0657① |

| Δ4 wk | −0.3 (9.0) | 14 | −2.6 (6.5) | 14 | −2.3 | (−8.4, 3.7) | 0.4334① |

| Δ8 wk | −1.8 (8.7) | 14 | 0.7 (8.6) | 15 | 2.6 | (−4.0, 9.2) | 0.4295① |

| Δ12 wk | −2.8 (9.6) | 15 | −0.3 (4.9) | 15 | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.7) | 0.6187② |

| CVC%max | |||||||

| Baseline | 55.8 (12.9) | 15 | 52.5 (18.7) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.6) | 0.5897② |

| Δ4 wk | 0.9 (11.1) | 14 | −3.7 (11.1) | 14 | −4.7 | (−13.3, 4.0) | 0.2774① |

| Δ8 wk | −2.6 (13.9) | 14 | −0.7 (16.3) | 15 | 1.9 | (−9.7, 13.5) | 0.7406① |

| Δ12 wk | −2.2 (12.8) | 15 | −3.5 (14.3) | 15 | −1.2 | (−11.4, 8.9) | 0.8069① |

| Peak calf blood flow, mL/min/100 g | |||||||

| Baseline | 48.0 (24.6) | 12 | 43.8 (20.4) | 11 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.7582② |

| Δ4 wk | −0.9 (16.0) | 11 | −1.0 (10.5) | 9 | −0.1 | (−13.2, 13.0) | 0.9883① |

| Δ8 wk | −4.8 (21.9) | 11 | −2.8 (11.0) | 11 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8438② |

| Δ12 wk | −5.4 (20.8) | 11 | −4.4 (13.6) | 11 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.9476② |

Values are means (SD); n, number of participants. ABI, ankle-brachial index; CVC%max, cutaneous vascular conductance normalized as a percentage of maximal vasodilation; DBP, diastolic pressure; HT, heat therapy; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic pressure.

Two-sample two-tailed t tests (①) were used to compare changes between HT and sham at each follow-up when the differences were normally distributed (normality tested via Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Otherwise, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (②) were used. Group effects were estimated by the difference in changes for normally distributed changes and the Mann–Whitney parameter () for non-normally distributed changes.

Table 4.

VascuQOL and SF-36v2 scores in the sham-treated group and the HT group at baseline and at 4-, 8-, and 12-wk follow-ups

| Sham |

Heat Therapy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | n | n | Group Effect Estimate* | (95% CI) | P value | ||

| VascuQOL | |||||||

| Pain | |||||||

| Baseline | 4.2 (1.1) | 15 | 3.8 (1.6) | 15 | −0.4 | (−1.4, 0.7) | 0.4429① |

| Δ4 wk | 0.7 (0.9) | 14 | 0.3 (0.5) | 13 | −0.3 | (−0.9, 0.2) | 0.2617① |

| Δ8 wk | 0.9 (0.9) | 14 | 0.8 (0.7) | 15 | −0.1 | (−0.7, 0.6) | 0.8113① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.7 (0.9) | 15 | 0.8 (1.0) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8839② |

| Emotional | |||||||

| Baseline | 5.6 (1.2) | 15 | 5.2 (1.8) | 15 | −0.4 | (−1.5, 0.7) | 0.5022① |

| Δ4wk | 0.5 (0.8) | 14 | 0.2 (0.5) | 13 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.4799② |

| Δ8 wk | 0.6 (1.0) | 14 | 0.5 (0.7) | 15 | −0.1 | (−0.7, 0.5) | 0.7554① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.6 (1.1) | 15 | 0.3 (1.3) | 15 | −0.2 | (−1.1, 0.6) | 0.5726① |

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Baseline | 5.5 (1.1) | 15 | 4.9 (1.5) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.1886② |

| Δ4 wk | 0.2 (1.1) | 14 | 0.3 (0.9) | 13 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.6945② |

| Δ8 wk | 0.3 (0.9) | 14 | 0.5 (0.6) | 15 | 0.2 | (−0.4, 0.8) | 0.4673① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.1 (1.2) | 15 | 0.6 (0.9) | 15 | 0.5 | (−0.3, 1.3) | 0.1864① |

| Social | |||||||

| Baseline | 5.9 (1.2) | 15 | 5.3 (2.0) | 15 | −0.6 | (−1.9, 0.6) | 0.2984① |

| Δ4 wk | 0.0 (1.2) | 14 | −0.1 (0.7) | 13 | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.6) | 0.6163② |

| Δ8 wk | 0.2 (1.0) | 14 | 0.1 (1.1) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.9630② |

| Δ12 wk | 0.4 (1.4) | 15 | 0.2 (1.0) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.2452② |

| Activity | |||||||

| Baseline | 4.2 (1.0) | 15 | 4.1 (1.6) | 15 | −0.1 | (−1.1, 0.9) | 0.8628① |

| Δ4 wk | 0.8 (1.2) | 14 | 0.3 (0.4) | 13 | −0.6 | (−1.3, 0.2) | 0.1200① |

| Δ8 wk | 0.6 (1.1) | 14 | 0.6 (1.0) | 15 | −0.0 | (−0.8, 0.8) | 0.9511① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.6 (1.0) | 15 | 0.6 (1.1) | 15 | 0.0 | (−0.7, 0.8) | 0.8429① |

| Total | |||||||

| Baseline | 4.9 (0.9) | 15 | 4.6 (1.5) | 15 | −0.4 | (−1.3, 0.6) | 0.4573① |

| Δ4 wk | 0.6 (0.8) | 14 | 0.2 (0.3) | 13 | −0.3 | (−0.8, 0.2) | 0.2073① |

| Δ8 wk | 0.6 (0.8) | 14 | 0.5 (0.6) | 15 | −0.0 | (−0.6, 0.5) | 0.9446① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.5 (0.8) | 15 | 0.5 (1.0) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.9669② |

| SF-36v2 | |||||||

| Physical functioning | |||||||

| Baseline | 50.6 (19.8) | 15 | 47.8 (29.1) | 15 | −2.8 | (−21.4, 15.8) | 0.7590① |

| Δ4 wk | 3.9 (12.9) | 14 | 4.4 (13.7) | 13 | 0.5 | (−10.1, 10.9) | 0.9322① |

| Δ8 wk | 4.5 (10.8) | 14 | 4.5 (15.9) | 15 | −0.0 | (−10.4, 10.4) | 0.9983① |

| Δ12 wk | −2.1 (12.5) | 15 | 5.5 (16.2) | 15 | 7.7 | (−3.2, 18.5) | 0.1580① |

| Role physical | |||||||

| Baseline | 58.0 (30.9) | 15 | 57.9 (38.8) | 15 | −0.1 | (−26.9, 26.7) | 0.9928① |

| Δ4 wk | 10.1 (26.5) | 13 | −1.4 (15.1) | 13 | 0.4 | (0.2,0.6) | 0.2842② |

| Δ8 wk | 7.2 (20.4) | 13 | 3.8 (19.6) | 15 | −3.5 | (−19.0, 12.1) | 0.6511① |

| Δ12 wk | 10.7 (18.7) | 14 | 5.0 (18.0) | 15 | −5.7 | (−19.7, 8.3) | 0.4099① |

| Bodily pain | |||||||

| Baseline | 60.1 (26.8) | 15 | 49.4 (23.6) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.2805② |

| Δ4 wk | 1.0 (16.1) | 13 | 1.7 (8.6) | 13 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8347② |

| Δ8 wk | 9.1 (25.1) | 13 | 8.1 (12.9) | 15 | −0.9 | (−17.2, 15.3) | 0.9040① |

| Δ12 wk | −1.4 (19.8) | 14 | 8.6 (20.5) | 14 | 0.7 | (0.4, 0.8) | 0.1629② |

| General health | |||||||

| Baseline | 59.3 (18.3) | 15 | 61.7 (17.8) | 15 | 2.4 | (−11.1, 15.9) | 0.7187① |

| Δ4 wk | 11.4 (11.1) | 14 | 1.3 (11.0) | 13 | −10.0 | (−18.8, −1.3) | 0.0265① |

| Δ8 wk | 4.6 (11.1) | 14 | −2.7 (14.0) | 15 | −7.4 | (−17.1, 2.3) | 0.1295① |

| Δ12 wk | 8.2 (11.5) | 15 | 1.3 (13.1) | 15 | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.5) | 0.1069② |

| Vitality | |||||||

| Baseline | 64.3 (22.3) | 15 | 63.3 (26.9) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8433② |

| Δ4 wk | 2.9 (7.0) | 13 | −7.2 (20.2) | 13 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.2195② |

| Δ8 wk | 5.0 (10.7) | 13 | −3.5 (17.2) | 15 | −8.4 | (−19.8, 2.9) | 0.1385① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.9 (15.9) | 14 | −1.3 (20.1) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 1.0000② |

| Social functioning | |||||||

| Baseline | 86.7 (21.4) | 15 | 71.7 (35.8) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.2228② |

| Δ4 wk | 0.0 (23.0) | 14 | −1.0 (22.5) | 13 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.9166② |

| Δ8 wk | 1.8 (18.3) | 14 | 0.8 (23.4) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8290② |

| Δ12 wk | 2.5 (20.2) | 15 | 7.1 (25.8) | 14 | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.7) | 0.4700② |

| Role emotional | |||||||

| Baseline | 77.4 (29.3) | 15 | 76.4 (32.0) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.8894② |

| Δ4 wk | 7.1 (24.3) | 13 | −3.2 (15.4) | 13 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.4590② |

| Δ8 wk | 10.9 (21.1) | 13 | −0.3 (13.0) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.2060② |

| Δ12 wk | 10.1 (18.0) | 14 | 6.9 (12.6) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.6) | 0.5210② |

| Mental health | |||||||

| Baseline | 83.9 (12.9) | 15 | 76.3 (26.8) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 1.0000② |

| Δ4 wk | 2.3 (5.6) | 13 | −0.8 (13.5) | 13 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.4428② |

| Δ8 wk | 0.8 (8.6) | 13 | 2.0 (11.3) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 1.0000② |

| Δ12 wk | 2.5 (12.0) | 14 | −1.0 (19.2) | 15 | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.5062② |

| Physical component | |||||||

| Baseline | 39.6 (8.5) | 15 | 39.3 (10.7) | 15 | −0.3 | (−7.9, 7.3) | 0.9347① |

| Δ4 wk | 3.2 (5.2) | 12 | 1.1 (5.3) | 13 | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.2012② |

| Δ8 wk | 2.3 (6.0) | 12 | 1.7 (6.1) | 15 | −0.6 | (−5.5, 4.2) | 0.7945① |

| Δ12 wk | 0.9 (4.3) | 13 | 2.6 (5.7) | 14 | 1.6 | (−2.4, 5.6) | 0.4053① |

| Mental component | |||||||

| Baseline | 56.5 (9.1) | 15 | 53.5 (14.9) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.7124② |

| Δ4 wk | 0.8 (5.1) | 12 | −2.1 (5.4) | 13 | −2.9 | (−7.3, 1.4) | 0.1781① |

| Δ8 wk | 2.2 (3.3) | 12 | −0.7 (4.6) | 15 | −2.9 | (−6.1, 0.4) | 0.0801① |

| Δ12 wk | 2.9 (5.1) | 13 | 0.6 (7.3) | 14 | −2.4 | (−7.4, 2.7) | 0.3450① |

Values are means (SD); n, number of participants. HT, heat therapy; SF-36v2, the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; VascuQoL, Vascular Quality of Life questionnaire.

Two-sample two-tailed t tests (①) were used to compare changes between HT and sham at each follow-up when the differences were normally distributed (normality tested via Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Otherwise, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (②) were used. Group effects were estimated by the difference in changes for normally distributed changes and the Mann–Whitney parameter () for non-normally distributed changes.

Exploratory Outcomes

The results of the endothelial cell tube formation assay are displayed in Table 5. The changes from baseline in total tubule length and number of tubes per field of view were similar between the HT and sham groups.

Table 5.

Endothelial tube formation following exposure to serum from patients treated with HT or the sham treatment

| Outcomes | Sham |

Heat Therapy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | Group Effect Estimate* | (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Number of tubes per field of view, n | |||||||

| Baseline | 73.1 (14.7) | 15 | 72.1 (14.7) | 15 | −1.0 | (−12.0, 10.0) | 0.8533① |

| Δ8 wk | 2.3 (12.1) | 15 | 2.8 (12.7) | 15 | 0.5 | (−8.8,9.7) | 0.9187① |

| Total tubule length, mm/field | |||||||

| Baseline | 5779.8 (567.3) | 15 | 5788.1 (684.8) | 15 | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.9010② |

| Δ8 wk | 127.1 (627.5) | 15 | 119.5 (609.8) | 15 | −7.6 | (−470.4, 455.1) | 0.9733① |

Values are means (SD) or n (number of participants). HT, heat therapy.

Two-sample two-tailed t tests (①) were used to compare changes between HT and sham at each follow-up when the differences were normally distributed (normality tested via Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Otherwise, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (②) were used. Group effects were estimated by the difference in changes for normally distributed changes and the Mann–Whitney parameter () for non-normally distributed changes.

DISCUSSION

In prior studies that examined the therapeutic effects of HT in PAD, participants were required to attend supervised sessions in clinical or laboratory settings (22, 23, 26). The need for supervision and the requirement of frequent commuting to a clinical facility to receive the treatment are obstacles to the widespread accessibility to HT modalities, particularly for elderly individuals with impaired physical function. Aiming to overcome these critical barriers, we assessed the feasibility and safety of home-based, unsupervised leg HT. Our findings revealed that repeated leg heating using water-circulating trousers coupled with a water pump was safe and well-tolerated by elderly patients with symptomatic PAD. In agreement with our earlier studies (26–28), no serious adverse reactions to treatment were observed. Furthermore, participants assigned to the leg HT group reported that they completed 92% of the required sessions, indicating that the uptake and adherence to the treatment was satisfactory.

The group exposed to daily HT for 8 wk displayed a mean change in 6-min walk distance relative to baseline of 24 m, whereas the sham-treated group exhibited a mean change of 4 m. The relevance of these findings is clear when considering recent estimates of MCID in 6-min walk distance in people with PAD. In an exploratory analysis of data from a clinical trial that involved 156 participants with symptomatic PAD and examined changes in walking performance following a home‐exercise program, a supervised exercise program, and an attention‐control intervention, Gardner et al. (46) estimated that MCIDs for small, moderate, and large changes in the 6-min walk distance were 12, 32, and 34 m, respectively. More recently, McDermott et al. (47) combined data from 777 individuals with PAD that had participated in three large longitudinal observational studies and reported that an 8-m increase corresponds to a small meaningful improvement in the 6-min walk distance, whereas an increase of 20 m represents a large improvement. Based upon these data, the changes in 6-min walk distance displayed by participants treated with leg HT for 8 wk may be considered clinically meaningful. Nonetheless, prior studies with both far infrared sauna (i.e., Waon therapy) (22, 23) and spa bathing combined with calisthenics (24) in patients with PAD reported much greater improvements in 6-min walk distance, ranging from 47 to 81 m. These larger changes may be explained by differences in the experimental design, heating modality, treatment regimen, and disease severity of patients with PAD (22–24).

In our previous randomized clinical trial, we reported that supervised leg HT for 6 wk promoted a significant increase in perceived physical functioning, as assessed using the Short-Form 36 Questionnaire, in patients with symptomatic PAD (26). However, 6-min walk distance did not improve when compared with the control group (26). In sharp contrast, the current study revealed that 8 wk of unsupervised leg HT improved 6-min walk distance but had no significant impact on perceived quality of life relative to the sham treatment. These discrepancies strengthen the notion that objective measures of walking performance are dissociated from perceived walking improvement in patients with PAD (48). The results from the recently completed LITE trial revealed that patients assigned to undergo 12 mo of home-based low-intensity exercise reported an improvement in the scores of Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ) despite exhibiting no changes in 6-min walk distance (49). Conversely, individuals that underwent high-intensity exercise improved 6-min walk distance by 34.5 m at the 12-mo follow-up but reported similar changes in the WIQ score compared with the low-intensity exercise group (49). Among other reasons, it has been proposed that increases in walking ability following therapeutic interventions for PAD may translate into enhanced habitual physical activity levels and a consequent increased occurrence of ischemic leg symptoms (48). The resulting exacerbation of leg pain may mask the improvement in perceived walking performance and quality of life, thus explaining the discordance between objective and subjective measures of functional capacity (48).

The improvements in 6-min walk distance in the group exposed to HT were paralleled by an increase of 109.5 s in peak walking time on the treadmill test. However, of particular importance, the maximal treadmill walking time increased by 61.5 s at the 8-wk follow-up in participants treated with the sham regimen, despite negligible changes in 6-min walk distance. This latter observation is not unique to the current study. In a multicenter trial that evaluated the effect of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor NM-702 on treadmill walking performance in claudicants, patients assigned to the placebo group displayed an increase in peak walking time of 25 s at the 12-wk follow-up and of 34 s at the 24-wk follow-up (50). Similarly, a comprehensive analysis of data from four randomized trials of therapeutic interventions in participants with PAD revealed that participants randomized to a control and/or placebo group significantly improved maximal treadmill walking distance by 35 m (48). This phenomenon has been largely ascribed to learning and/or placebo effects, including a potential optimization of gait during repeated testing (51). The implications of this concept to the current study are clear when considering that the placebo effect of medical devices, such as the pump and trousers utilized herein, may be particularly enhanced when compared with inert pills (52, 53).

Contrary to our hypothesis, HT had no significant impact on cutaneous and calf microvascular function or the serum-mediated growth of cultured endothelial cells. It has been hypothesized that the benefits associated with HT derive, in part, from improvements in nitric-oxide availability and a consequent increase in vascular reactivity and angiogenesis (54). However, the majority of the few controlled interventional studies that examined changes in vascular function following HT focused on healthy, young individuals (31, 55–57). When coupled with our previous findings (26) and those of Akerman et al. (24), the current study challenges the notion that HT has a meaningful effect on vascular health in patients with symptomatic PAD. One alternative hypothesis is that the salutary effects of HT arise from the mitigation of leg muscle abnormalities. In a mouse model of PAD induced by ligation of the femoral artery, we first showed that repeated HT increased relative muscle mass and maximal strength of the soleus muscle (58). In a subsequent study in a model of combined diet-induced obesity and PAD, we showed that repeated HT prevented an increase in body mass induced by high-fat feeding due to reduced fat accrual and increased both muscle mass relative to body mass and maximal absolute force of the extensor digitorum longus muscle (59). These findings are in agreement with previous reports that HT attenuates skeletal muscle atrophy during immobilization and unloading (60, 61) and rescues denervation-induced atrophy (62, 63). In young individuals, we showed that 5 days of local HT application hastens the recovery of muscle fatigue resistance following muscle damage (64). We also documented that daily exposure to local HT for 8 wk enhances the strength of knee extensors and increases the skeletal muscle content of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in young adults (65). Additional studies are warranted to define whether these findings hold true for patients with symptomatic PAD.

Limitations

This pilot trial has several limitations. First, our findings are restricted to patients that exhibit intermittent claudication, which is prevalent in about one-third of patients with PAD (66). Asymptomatic patients and those that experience atypical leg pain symptoms also display exercise intolerance and accelerated functional decline (66) and may possibly benefit from HT. Second, the intervention lasted only 8 wk, which is shorter than the recommended minimal duration of supervised exercise training interventions (12 wk), the gold standard treatment for PAD (67). A longer program duration has the potential to magnify the benefits of HT. Third, the sham device utilized in the present study does not induce the same sensation as the active treatment, raising the possibility that patients may become unblinded to the treatment allocation (34). Fourth, compliance with the prescribed regimen was estimated based upon patient reports obtained during weekly phone calls. Direct assessment methods, such as timers built in the HT system and inaccessible to patients, can provide more accurate rates of compliance. Fifth, following our study protocol, participants that failed to complete three consecutive treatment sessions or a total of eight sessions throughout were excluded. Predictably, the overall adherence rate to the prescribed regimen would be lower if these participants were not excluded. Sixth, although our estimated sample size was of 16 subjects per group, the final analysis of the primary study outcome included data from 14 participants in the sham-treated group and 15 patients from the group exposed to HT. Seventh, study participants were instructed to stop the treatment 48 h before the outcome sessions to minimize the confounding influence of acute and subacute adjustments to leg HT on the long-term adaptations to repeated treatment. Nonetheless, the time required to enable a complete “washout” of the acute effects of leg HT in people with PAD is unknown. Finally, the CVC responses to local heating to 39°C were normalized as a percentage of the value obtained after heating the skin to 43°C for 20 min. It is possible that local heating to 43°C is insufficient to produce maximal cutaneous vasodilation. A combination of local heating with another challenge, such as locally applied sodium nitroprusside or reactive hyperemia, may be required to elicit maximal cutaneous vasodilation (68).

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

The results of this pilot study indicate that unsupervised, repeated leg heating may improve walking performance in patients with symptomatic PAD. However, the physiological mechanisms by which HT enhances functional capacity in PAD remain undefined. A larger, definitive trial is needed to firmly establish the effects of unsupervised leg HT on lower extremity functioning in people with PAD. A critical advantage of water-circulating trousers as a heating modality is the portability, which makes this option amenable for use in the home setting by individuals with restricted mobility. Furthermore, the heating stimulus utilized herein produces small increases in core body temperature (i.e., ∼0.5°C) and may be better tolerated than sauna and hot water immersion. Nonetheless, future implementation of this new approach will require the development of clinical-grade leg HT systems that are inexpensive, safe, and practical for elderly patients with PAD.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant 1R21AG053687-01A1 (to B. T. Roseguini and R. L. Motaganahalli).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.C.M., R.L.M., and B.T.R. conceived and designed research; J.C.M., C.K., J.K., and B.T.R. performed experiments; J.C.M., B.J.P., C.K., J.P., S.M.P., Y.H., and B.T.R. analyzed data; J.C.M., B.J.P., C.K., T.P.G., S.M.P., Y.H., and B.T.R. interpreted results of experiments; J.C.M. and B.T.R. prepared figures; J.C.M. and B.T.R. drafted manuscript; J.C.M., B.J.P., C.K., T.P.G., J.P., S.M.P., Y.H., R.L.M., and B.T.R. edited and revised manuscript; J.C.M., B.J.P., C.K., T.P.G., J.P., S.M.P., Y.H., J.K., R.L.M., and B.T.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Kevin Pasciak and Carson Shupe from the Indiana University Methodist Hospital Cardiology Department for assistance in conducting the cardiopulmonary exercise tests. We also thank Dave Rollins and staff from the IU Health Vascular Diagnostics Center for their contribution to the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration; Fowkes FG, Murray GD, Butcher I, Heald CL, Lee RJ, et al. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA 300: 197–208, 2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR, Coll JR, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Hirsch AT. The impact of peripheral arterial disease on health-related quality of life in the Peripheral Arterial Disease Awareness, Risk, and Treatment: New Resources for Survival (PARTNERS) program. Vasc Med 13: 15–24, 2008. doi: 10.1177/1358863X07084911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Celic L, Criqui MH, Chan C, Martin GJ, Schneider J, Pearce WH, Taylor LM, Clark E. The ankle brachial index is associated with leg function and physical activity: the Walking and Leg Circulation Study. Ann Intern Med 136: 873–883, 2002. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-12-200206180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Bronas UG, Campia U, Collins TC, Criqui MH, Gardner AW, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG, Rich K; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Optimal exercise programs for patients with peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association . Circulation 139: e10–e33, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saxon JT, Safley DM, Mena-Hurtado C, Heyligers J, Fitridge R, Shishehbor M, Spertus JA, Gosch K, Patel MR, Smolderen KG. Adherence to guideline-recommended therapy-including supervised exercise therapy referral-across peripheral artery disease specialty clinics: insights from the International PORTRAIT Registry. J Am Heart Assoc 9: e012541, 2020. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larsen RG, Thomsen JM, Hirata RP, Steffensen R, Poulsen ER, Frøkjær JB, Graven‐Nielsen T. Impaired microvascular reactivity after eccentric muscle contractions is not restored by acute ingestion of antioxidants or dietary nitrate. Physiol Rep 7: e14162, 2019. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harwood AE, Smith GE, Cayton T, Broadbent E, Chetter IC. A systematic review of the uptake and adherence rates to supervised exercise programs in patients with intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg 34: 280–289, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whipple MO, Schorr EN, Talley KMC, Lindquist R, Bronas UG, Treat-Jacobson D. A mixed methods study of perceived barriers to physical activity, geriatric syndromes, and physical activity levels among older adults with peripheral artery disease and diabetes. J Vasc Nurs 37: 91–105, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Spring B, Tian L, Domanchuk K, Ferrucci L, Lloyd-Jones D, Kibbe M, Tao H, Zhao L, Liao Y, Rejeski WJ. Home-based walking exercise intervention in peripheral artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310: 57–65, 2013. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDermott MM, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Ferrucci L, Zhao L, Liu K, Domanchuk K, Spring B, Tian L, Kibbe M, Liao Y, Lloyd Jones D, Rejeski WJ. Home-based walking exercise in peripheral artery disease: 12-month follow-up of the GOALS randomized trial. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e000711, 2014. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Regensteiner JG. Exercise rehabilitation for the patient with intermittent claudication: a highly effective yet underutilized treatment. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord 4: 233–239, 2004. doi: 10.2174/1568006043336195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Chan C, Pearce WH, Schneider JR, Ferrucci L, Celic L, Taylor LM, Vonesh E, Martin GJ, Clark E. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA 292: 453–461, 2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Imamura M, Biro S, Kihara T, Yoshifuku S, Takasaki K, Otsuji Y, Minagoe S, Toyama Y, Tei C. Repeated thermal therapy improves impaired vascular endothelial function in patients with coronary risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 1083–1088, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01467-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kihara T, Biro S, Imamura M, Yoshifuku S, Takasaki K, Ikeda Y, Otuji Y, Minagoe S, Toyama Y, Tei C. Repeated sauna treatment improves vascular endothelial and cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 754–759, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01824-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohori T, Nozawa T, Ihori H, Shida T, Sobajima M, Matsuki A, Yasumura S, Inoue H. Effect of repeated sauna treatment on exercise tolerance and endothelial function in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 109: 100–104, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sobajima M, Nozawa T, Fukui Y, Ihori H, Ohori T, Fujii N, Inoue H. Waon therapy improves quality of life as well as cardiac function and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Int Heart J 56: 203–208, 2015. doi: 10.1536/ihj.14-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sobajima M, Nozawa T, Ihori H, Shida T, Ohori T, Suzuki T, Matsuki A, Yasumura S, Inoue H. Repeated sauna therapy improves myocardial perfusion in patients with chronically occluded coronary artery-related ischemia. Int J Cardiol 167: 237–243, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ely BR, Clayton ZS, McCurdy CE, Pfeiffer J, Needham KW, Comrada LN, Minson CT. Heat therapy improves glucose tolerance and adipose tissue insulin signaling in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 317: E172–E182, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00549.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ely BR, Francisco MA, Halliwill JR, Bryan SD, Comrada LN, Larson EA, Brunt VE, Minson CT. Heat therapy reduces sympathetic activity and improves cardiovascular risk profile in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 317: R630–R640, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00078.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akasaki Y, Miyata M, Eto H, Shirasawa T, Hamada N, Ikeda Y, Biro S, Otsuji Y, Tei C. Repeated thermal therapy up-regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase and augments angiogenesis in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Circ J 70: 463–470, 2006. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miyauchi T, Miyata M, Ikeda Y, Akasaki Y, Hamada N, Shirasawa T, Furusho Y, Tei C. Waon therapy upregulates Hsp90 and leads to angiogenesis through the Akt-endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway in mouse hindlimb ischemia. Circ J 76: 1712–1721, 2012. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shinsato T, Miyata M, Kubozono T, Ikeda Y, Fujita S, Kuwahata S, Akasaki Y, Hamasaki S, Fujiwara H, Tei C. Waon therapy mobilizes CD34+ cells and improves peripheral arterial disease. J Cardiol 56: 361–366, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tei C, Shinsato T, Miyata M, Kihara T, Hamasaki S. Waon therapy improves peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 2169–2171, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Akerman AP, Thomas KN, van Rij AM, Body ED, Alfadhel M, Cotter JD. Heat therapy vs. supervised exercise therapy for peripheral arterial disease: a 12-wk randomized, controlled trial. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 316: H1495–H1506, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00151.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Calder A, Sole G, Mulligan H. The accessibility of fitness centers for people with disabilities: A systematic review. Disabil Health J 11: 525–536, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monroe JC, Lin C, Perkins SM, Han Y, Wong BJ, Motaganahalli RL, Roseguini BT. Leg heat therapy improves perceived physical function but does not enhance walking capacity or vascular function in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 129: 1279–1289, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00277.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Monroe JC, Song Q, Emery MS, Hirai DM, Motaganahalli RL, Roseguini BT. Acute effects of leg heat therapy on walking performance and cardiovascular and inflammatory responses to exercise in patients with peripheral artery disease. Physiol Rep 8: e14650, 2021. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neff D, Kuhlenhoelter AM, Lin C, Wong BJ, Motaganahalli RL, Roseguini BT. Thermotherapy reduces blood pressure and circulating endothelin-1 concentration and enhances leg blood flow in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R392–R400, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00147.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crandall CG, Wilson TE. Human cardiovascular responses to passive heat stress. Compr Physiol 5: 17–43, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas KN, van Rij AM, Lucas SJ, Cotter JD. Lower-limb hot-water immersion acutely induces beneficial hemodynamic and cardiovascular responses in peripheral arterial disease and healthy, elderly controls. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R281–R291, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00404.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brunt VE, Weidenfeld-Needham KM, Comrada LN, Francisco MA, Eymann TM, Minson CT. Serum from young, sedentary adults who underwent passive heat therapy improves endothelial cell angiogenesis via improved nitric oxide bioavailability. Temperature (Austin) 6: 169–178, 2019. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2019.1614851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Messner B, Bernhard D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 509–515, 2014. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.300156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Monroe JC, Lin C, Perkins SM, Han Y, Wong BJ, Motaganahalli RL, Roseguini BT. Leg heat therapy improves perceived physical function but does not enhance walking capacity or vascular function in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 129: 1279–1289, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00277.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fregni F, Imamura M, Chien HF, Lew HL, Boggio P, Kaptchuk TJ, Riberto M, Hsing WT, Battistella LR, Furlan A, International Placebo Symposium Working Group. Challenges and recommendations for placebo controls in randomized trials in physical and rehabilitation medicine: a report of the international placebo symposium working group. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89: 160–172, 2010. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181bc0bbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 111–117, 2002. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDermott MM, Ades PA, Dyer A, Guralnik JM, Kibbe M, Criqui MH. Corridor-based functional performance measures correlate better with physical activity during daily life than treadmill measures in persons with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 48: 1231–1237, 1237e1231, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morris DR, Rodriguez AJ, Moxon JV, Cunningham MA, McDermott MM, Myers J, Leeper NJ, Jones RE, Golledge J. Association of lower extremity performance with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with peripheral artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e001105, 2014. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McDermott MM, Ferrucci L, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Tian L, Liao Y, Criqui MH. Leg symptom categories and rates of mobility decline in peripheral arterial disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 1256–1262, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, Diehm C, Fowkes FG, Hiatt WR, Jonsson B, Lacroix P, Marin B, McDermott MM, Norgren L, Pande RL, Preux PM, Stoffers HE, Treat-Jacobson D; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease;Council on Epidemiology and Prevention;Council on Clinical Cardiology;Council on Cardiovascular Nursing;Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 126: 2890–2909, 2012. [Erratum in Circulation 127: e264, 2013]. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choi PJ, Brunt VE, Fujii N, Minson CT. New approach to measure cutaneous microvascular function: an improved test of NO-mediated vasodilation by thermal hyperemia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 277–283, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01397.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mehta T, Venkata Subramaniam A, Chetter I, McCollum P. Assessing the validity and responsiveness of disease-specific quality of life instruments in intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 31: 46–52, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morgan MB, Crayford T, Murrin B, Fraser SC. Developing the Vascular Quality of Life Questionnaire: a new disease-specific quality of life measure for use in lower limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 33: 679–687, 2001. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.112326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carpentier G, Berndt S, Ferratge S, Rasband W, Cuendet M, Uzan G, Albanese P. Angiogenesis Analyzer for ImageJ—A comparative morphometric analysis of “Endothelial Tube Formation Assay” and “Fibrin Bead Assay”. Sci Rep 10: 11568, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67289-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Blevins SM. Step-monitored home exercise improves ambulation, vascular function, and inflammation in symptomatic patients with peripheral artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e001107, 2014. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 54: 743–749, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Wang M. Minimal clinically important differences in treadmill, 6-minute walk, and patient-based outcomes following supervised and home-based exercise in peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med 23: 349–357, 2018. doi: 10.1177/1358863X18762599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McDermott MM, Tian L, Criqui MH, Ferrucci L, Conte MS, Zhao L, Li L, Sufit R, Polonsky TS, Kibbe MR, Greenland P, Leeuwenburgh C, Guralnik JM. Meaningful change in 6-minute walk in people with peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg 73: 267–276.e1, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McDermott MM, Tian L, Criqui MH, Ferrucci L, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, Kibbe MR, Li L, Sufit R, Zhao L, Polonsky TS. Perceived versus objective change in walking ability in peripheral artery disease: results from 3 randomized clinical trials of exercise therapy. J Am Heart Assoc 10: e017609, 2021. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McDermott MM, Spring B, Tian L, Treat-Jacobson D, Ferrucci L, Lloyd-Jones D, Zhao L, Polonsky T, Kibbe MR, Bazzano L, Guralnik JM, Forman DE, Rego A, Zhang D, Domanchuk K, Leeuwenburgh C, Sufit R, Smith B, Manini T, Criqui MH, Rejeski WJ. Effect of low-intensity vs. high-intensity home-based walking exercise on walk distance in patients with peripheral artery disease: the LITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 325: 1266–1276, 2021. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brass EP, Anthony R, Cobb FR, Koda I, Jiao J, Hiatt WR. The novel phosphodiesterase inhibitor NM-702 improves claudication-limited exercise performance in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 2539–2545, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hiatt WR, Rogers RK, Brass EP. The treadmill is a better functional test than the 6-minute walk test in therapeutic trials of patients with peripheral artery disease. Circulation 130: 69–78, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]