Abstract

Background: Rare diseases-related services, care, and drugs (Orphan Drugs) in a lower-middle-income country such as Iran with international limitations due to the sanctions is a challenging issue in terms of their financing and providing. This study aims to address financing issues related to rare diseases in a lower-middle-income country that is under international sanctions.

Methods: This is a qualitative study that has been conducted through 14 interviews with experts from different stakeholders in the country to find the challenges of financing rare diseases and orphan drugs in Iran through a content analysis according to Mayring’s approach. We accomplished this study based on the World Health Organization’s universal health coverage model.

Results: We achieved four themes and 12 sub-themes. The themes are the unstable and sanctioned economy including 4 sub-themes; extending the covered population by the social security net in the country including 2 sub-themes; reducing the cost-sharing for the covered population including 4 sub-themes; including more orphan drugs and services including 2 sub-themes.

Conclusion: The financing of rare diseases and orphan drugs in Iran is challenged by several contextual and internal factors. The political issues seem to have the main contribution of the challenge to develop an efficient and effective financing mechanism for rare diseases and orphan drugs. This is especially can be related to the politicians’ commitments and pursuing an effective plan to allocate the financial resources to rare diseases. However, the country’s economic situation, especially at the macro level because of international limitations, has intensified the problem.

Keywords: Rare Diseases, Orphan Drugs, Resource Allocation, Health Care Financing, Universal Health Coverage

Introduction

↑What is “already known” in this topic:

Protecting RDs and ODs through taking them in policymaking priority agenda, especially in terms of financing, have been addressed in high-income countries and some middle-income countries.

→What this article adds:

Give a snapshot from what types of challenges are limiting the country to taking the RDs and ODs in policymaking and financing agenda, especially regarding the limited economic context of the country over the recent years.

Rare Diseases (RDs) are taking place as a priority agenda in developed nations. However, the case does not look the same in the low and middle-income countries (LMICs), where there are several interrelated barriers to achieving better goals (1). The most prohibitive contributors in this regard are financial and budgetary shortages (2). These factors then can be followed by their dependency on the developed countries for having advanced diagnostic technologies alongside the drugs (3,4). In addition, in these countries, it looks like the policymakers' commitments on the RDs and their needed ODs is not a national priority and they tend to have more attractions on the more prevalent diseases (5). The public awareness about the RDs and their needs and public and social bodies in favor of these patients’ rights are among other prominent challenges for developing an established structure for pursuing the RDs patients’ demands (6).

Accessibility to the ODs, especially in terms of financial concerns, has always been a heated debate in the nations. The very costly Research and Development (R&D) process for manufacturing the ODs on one side and the small market size on the demand side mean that the context is not an interesting one for investment (7,8). It seems the theory of market failure is more apparent about the RDs services and ODs than other health illnesses and disorders. Therefore, the governments' intervention to direct both supply and demand sides to an optimum equilibrium point is inevitable.

One crucial part of that intervention is financing the ODs, care, and services for RDs patients. Financing of health care services is typically an important function of the governments in all health systems (9). It implies collecting the money from different economic sections, accumulating them through designated funds, and then purchasing the needed health services for the ill-health population (10). The money collections include general or earmarked (specific) taxes, users’ fees (out-of-pocket payments, deductions schemes, …), and health insurance premiums. The governments can use the cumulative revenues from these sources to purchase the services from the health care providers (11). However, there are some limitations in place, those financial resources are constrained, and the population health needs are relatively assumed to be unlimited. Therefore, the government needs to have a convincing trade-off between efficiency and equity (12). Thus, the first point in the mind is that prioritize the financial resources for the more common diseases. This approach could be known as the utilitarian perspective that sees the health care systems in a pure cost-benefit analysis as the basis for decision making and prioritizing the health care services (13).

However, there are still other views on the agenda that have been known as the egalitarians approach, and they believe the societies cannot achieve the maximum level of social welfare without giving space to interpersonal and between communities’ equality concerns (14). Therefore, the rarity could not be the sole reason for ignoring a part of a population.

In Iran, as a lower-middle-income country with a GDP per capita (constant 2010) of US$ 5,843.6 in 2020 (15) and imposed limitations to have accessibility to the international exchanges, the problem is deepened, and meeting the RDs needs especially in terms of the ODs is highly challenged. The current macroeconomic challenges and reduced financial abilities of the government and people alongside the international imposed political barriers harm the general population health and the RDs patients even more. The country does not have an explicit structure and program for supporting the RDs patients' needs.

The country’s major health system financing for secondary and tertiary health services comes from people's out-of-pocket payments, and the public (mandatory) health insurers have a lower contribution to the health care financing (16). There are three public health insurance funds in the country and several commercial insurers. The charities have limited space in financing the health care services however they are providing the health services as well (17). In recent years a national document has been developed through an intersectoral contribution from different stakeholders. It includes the actions and works that should be done by each part to manage the RDs and ODs issues in the country (18). Regarding the lack of an explicitly defined program for addressing the issue of financing RDs services and ODs in the country, we aimed to find what is the challenges and probable solutions for developing such a financing mechanism for covering RDs and ODs in the country.

Methods

Design

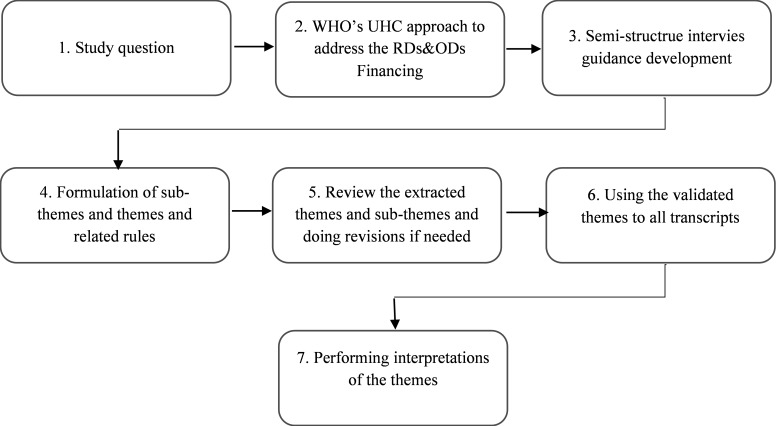

This is a qualitative study to find out the challenges and possible solutions for addressing the challenges of bringing the RDs and ODs in the financing agenda in a low-middle income country that has been faced with substantial international embargos due to sanctions. The study used Mayring’s content analysis method (Fig. 1) (19,20).

Fig. 1.

Mayring’s content-analysis procedural model

We conducted 14 interviews with experts who are representatives of different stakeholders of financing for RDs and ODs in the country. The study takes a conductive qualitative approach as we have used the World Health Organization framework for achieving the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and financial protection for health care services (21). This study is aligned with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) as a good qualitative research practice (22).

Conceptual Framework

The WHO’s UHC framework is based on a cube including three dimensions (23): the covered population (as the breadth of the cube), the cost-sharing situation as the height of the cube, and the covered services/care and drugs as the depth of it. Each dimension also contains a set of actions that should be accomplished to make sure nobody has been left behind the health system door. they encompass all aspects that are needed for developing a financing mechanism for RDs and ODs as well (Fig. 1). It assesses the current situation of the country in terms of RDs, and ODs financing has three main dimensions with their related actions. Figure 2 provides the conceptual framework for the study, and explanations about the dimensions of the UHC for RDs can be summarised as below:

Fig. 2.

The WHO’s UHC cube and its associated dimension

The number of people who are living with RDs in the country, the eligible population of RDs for benefiting any financing mechanisms, the enrolling/registry mechanism in this regard, monitoring the changes in the registry/enrolling mechanism (deaths, births, finding new cases,…), the characteristics of the registered/enrolled patients (demographical and socio-economic characteristics), the referral pattern of the patients (especially to the diagnostic, hospitalized, and pharmacies to get their needed services and drugs).

The proportion of the covered costs: This implies the cost-sharing arrangements when the patients utilize the services and drugs. The included aspects can be the share of the patients/or their households from the expenditures for services, care, and drugs, the share of the government/health insurer (either public or private) from the expense on the services and drugs, the availability of prepayment schemes for benefiting from the services and drugs, the sustainability of funds to the services and drugs, the availability of mechanisms for purchasing the needed services and drugs, availability of mechanisms of coordination in funding between different stakeholders. Mitigating the exchange rates instability and in a broader view the macroeconomic condition on the preparing and providing the services and drugs.

The covered services, care, and drugs (benefit package): This includes a range of topics. The availability of appropriate assessment mechanisms (e.g., Health Technology Assessment (HTA) to define the benefits package, who should take the governing role? What will be the contributions of the other stakeholders? Who is responsible for taking the claims about the drugs and services for RDs into the policy agenda?

All these dimensions are surrounded by macro or meso contextual factors. The country's political, social, and economic context surrounds the other dimensions of the UHC. This context implies the economic and political stability in the country, the political commitments, the social preferences in terms of having a financial space for supporting less or very fewer common diseases, social movements, and establishments for pursuing the RDs patients’ rights, the economic growth and sustainability of financial resources in this term.

Setting and sampling

We used a purposeful sampling approach to include experts from the Iran Ministry of Health (IMoH), Iran Health Insurance Organization (IHIO), Iran Social Security Organization (ISSO), Rare Disease Foundation of Iran (RDFI), Iran Food and Drugs Administration (IFDA), Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation (IKRF), Plan and Budget Organization of Iran (PBOI), and the Iran Ministry of Labour, Cooperative and Welfare (IMLCW). The team of the study knew all stakeholders’ interviewees except experts from RDFI and IMLCW that were introduced to the team of the study by the other interviewees. We included experts who can meet the following criteria: having experience in the RDs and ODs policy making, managing or conducting research projects, and having knowledge on the health care financing, pricing, and reimbursement. The participants' characteristics have been presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants .

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 10 (71) |

| Famele | 4 (29) | |

| Age | 35-40 | 2 (14) |

| 41-45 | 2 (14) | |

| 45-50 | 4 (29) | |

| ≥50 | 6 (43) | |

| Working Experiences | ≤10 | 2 (14) |

| 10-19 | 6 (43) | |

| ≥20 | 6 (43) | |

| Educational Qualification |

Undergraduate | 2 (14) |

| Postgraduate | 8 (57) | |

| MD/Pharmacists/Dentist | 4 (29) | |

| Employers | IMoH and affiliated bodies | 5 (36) |

| IHIO | 2 (14) | |

| SSO | 1 (7) | |

| IKRF | 1 (7) | |

| IMLCW | 1 (7) | |

| PBOI | 1 (7) | |

| RDFI | 3 (22) | |

The participants were approached by E-mail in the first instance. However, if no answer was received after two weeks, they were contacted by telephone.

Data Collection tool and method

We developed interview guidance according to the UHC dimensions and the contextual contributors in the field. The initial edition of the guidance was presented by SN to the other member of the team, and the final approved edition was tested through two pilot interviews with two participants. The first participant has raised some comments on the questions, and we made a few adjustments to them. The guidance includes a brief background on the importance and necessity of the issue of financing of RDs services and ODs in the country, the title of the study objectives, the study funder, ethics approval source, study team, and confidentiality of participants details. It included the demographical details of the interviewees and then 13 open-ended questions for interviewees according to the conceptual framework, which can be found in Additional file 1 in the Appendix.

Before arranging the interviews, a reference letter was issued by the Funder to be sent to the interviewees. Because of the COVID19 pandemic, three of the interviews were done through telephone, and for the rest of the interviews, we used Google Hangouts and WhatsApp desktop version. The interviews were recorded, and at the same time, the interviewer (SN) took notes. SN is a Ph.D. candidate of the Health Policy, has been working on three qualitative studies before this, and had a good background in performing the interviews. She also passed several courses about qualitative research conduction. All interviews were done between 10 July 2021 to 08 Sep. 2021. The shortest interview was about 32 minutes, and the longest was 1 hour and 20 minutes. The mean time for interviews was 52 minutes. After the 12th interview, there were no new or additional thoughts, and the data collection reached saturation.

Data analysis and processing

SN transcribed interviews in MS Word 2019, then checked them with SV to validate them. The transcriptions were sent to the interviewees to be approved. Nine participants returned the approvals of transcriptions approvals. Based on the theoretical framework and a meeting with SV, the sub-themes and themes were developed, and additional non-relevant sub-themes were removed. The results on themes and associated sub-themes have been quoted from Persian to English and tabulated by SN and SV, and MRM. Finally, four themes and 12 sub-themes were extracted.

Trustworthiness

Two professors and qualitative research experts (MRM and SV) approved the credibility of the data through the accurate and stepwise control of the research process. Interview transcription was also sent to the participants with the initial codes extracted to enhance the transferability of the extracted data. The confirmability of the data was ensured by interviewing a very different selection of participants and also through the frequent review of the data. The dependability of the data was verified by the audit trail. For this purpose, meaning units, codes, sub-themes, and themes were reviewed by an independent researcher.

Results

Initially, 16 invitations were sent to the participants; of them, 14 participants attended the interviews. The rate of participation was 87.5% that is still considered a high rate. Males were the major participants of the interviews (n=10); 12 participants had postgraduate qualifications. The majority of the interviewees had more than 10 years of experience in the field of policymaking, managing, and academic research working for RDs and ODs. The participants' mean of age and Standard Deviation were 51 and 6 years. Table 1 provides the characteristics of the participants.

Sub-themes and Themes

This part of the results provides the extracted themes and associated sub-themes regarding what interviewees have quoted and the theoretical framework. For each quotation, we have provided the organizational affiliation of the interviewees and added a number to identify the code for keeping the anonymity of the participants.

The macro and meso contextual conditions of the country:

-

The unstable and sanctioned economy: All interviewees asserted the degenerative impact of the current economic difficulties on giving an effective financing mechanism to preparing and providing services to the RD patients in the country. This is more apparent about the ODs purchasing and delivery. As the country is highly dependent on the ODs import, then the international sanction has imposed a very challenging situation in financial transactions and purchasing the drugs for the patients.

1.1. International sanctions issues:A manager at IMoH (I5) stated:” The sanctions are available, I think the only way to get rid of them is to die (he laughs), so for me, we need to find some humanitarian ways to secure the ODs for these poor patients, for example, we can use the current humanitarian channel between Switzerland and Iran [The Swiss Humanitarian Trade Arrangement (SHTA)]”.

1.2. The macr oeconomic instabilities and hyperinflati on: This is because the increasing exchange rate in the country is an important driver to the very costly ODs. The government has adopted this policy to amend the exchange rates fluctuations and could allocate the exchange to essential goods and commodities more effectively. However, it seems the classification system to define the necessity of a good/commodity is criticized by many importers and domestic producers.

An expert from IHIO (I1) stated:” About the ODs, fortunately, the government has recognized them as essentials. However, it is allocating the lower exchange rate to ODs we still observe discrepancies between stakeholders, and this harms the RD patients”.

1.3. The government’s misunderstanding of its role: political issues are among contextual factors that have been identified as an inhibitor of achieving a financing mechanism for RDs and ODs. A manager at RDFI (I7) believed:” I think we observe a swapped role between government and non-Governmental Organization (NGO) [he sighed] it is a pain that we as RDFI try to do somethings for these deprived people [RDs patients] instead of the government”.

Against this statement, on the other side, an expert from IMLCW (I4) mentioned:” charities in RDs and ODs [she insisted that doesn’t want to name any specific charity, however, from her indirect hints it was quite obvious which one she means!] think that we as policymakers [IMoH, IHIO, SSO, PBOI, in addition to IMLCW she means] need to be coordinated with them not them with us! [telling this with a sense of surprise]

1.4. The politicians’ commitments: The politicians’ thoughts about developing financing mechanisms for RDs and ODs is another heated debate that has been highlighted in 4 interviews. This issue is risen especially in terms of forgottenness of RDs problems and victimized it because of the small population of the country who are suffering from RDs. It seems the politicians and budget allocating bodies are not aware of what is happening for the RDs patients and their families because there are not sufficient financial resources for tackling the problem.

An interviewee (I12)from PBOI that is the top responsible budget allocating in the country says:” well, I think as the in-charge body for allocating the money to the different sections of the country, we are doing well [he looks very confidently], … we have more common and prevalent priorities… we are responsible for improving the social welfare as a whole with our limited financial resources… the sum up all individual welfare…”

-

Extending the covered population by the social security net in the country: As per the UHC framework, the breadth of the cube includes the number of populations that are benefiting from one or more of the current social welfare and security network(s) of a country. In the context of the RDs, this implies the number of OD patients who are covered by the current program (s) for receiving a service or care. For this theme, experts from IMoH, IHIO, SSO, RDFI, and IMLCW have raised concerns as below.

2.1. Registry system and infrastructure:A middle-level manager at IMoH (I5) says:” Identifying the eligible population and then enrolling them is the easiest forgotten ring in the chain of service delivery to the RD disease. Nowadays, we have lots of fragmented databases and information platforms in the country, … the only needed thing is to establish the link between them to include RDs, as well”.

However, this is not completely in line with the statement of an expert from RDFI (I3), as he says:” The RDFI (his affiliated foundation) is the most reliable way to make a linkage between RDs patients and families with the public/governmental bodies… you know I think we have more than two decades experiences in doing this work… IMoH as the health governor in the country has just come across the issue recently… We have good potential in identifying the targeted population and leading them to any designed health care financing schemes in the country,… but they [IMoH] always like to ignore us [RDFI]… [he looks very upset].

2.2. Unavailability of a national definition for RDs: In addition to these two comments, the head of a relevant office at IMLCW (I4) raised a comment in this regard: “This makes me surprised that we have not a nationally accepted definition for the RDs in this country… how we can speak about the financing of RDs and ODs in a country when we do not have a definition for it yet?! IMoH and RDFI are struggling with population coverage, and at the same time, none of them has a definition for the problem! [he has a combined sense of joking and regretting].

-

Reducing the cost-sharing for the covered population:For the RDs patients taking the services, care and ODs; necessarily means incurring financial shock. This is mostly from the cost attributed to the ODs. In the absence of a comprehensive and effective financing mechanism, it can cause catastrophic and impoverishing expenditures for RDs patients. This theme is thoroughly highlighted by all participants however there are some discrepancies about it:

3.1. The patients’ contributions to the payments for ODs and services: ODs are usually characterized as very costly drugs. In countries such as Iran that highly depend on the ODs import, and due to economic instability, the issue is more crucial. There are some drugs for managing RDs that are common with the other more prevalent drugs. However, there are still many drugs with specific indication for RDs that cannot be afforded by patients and their families. Providing ODs should be at a very high discount level or a full waive to make patients able to benefit from them. This has been asserted by all participants. Some highlights are as below:

A middle manager at SSO (I8) says:” Almost of policymakers only expect SSO [his affiliated organization] reimburses all costs for these patients [RDs patients], but I’m seriously wondering from which sources?... I think this is not ethical! They misuse these patients and their families' emotions and provoke them without providing any specific plan… just try to throw their responsibilities in this regard on our shoulders… I would like to thank Mr. President or Minister, could you please let us know regarding which financial resources you promise on behalf of us? [he looks upset].

3.2. The problems of prevention of ODs smuggling:Another problem in cost-sharing is related to concern about how to control the probable moral hazard from patients' families when they receive free, very expensive drugs. Four interviewees asserted this.

An expert from IMoH (I9) says: “Well! It is interesting! [he feels regret when speaking] families know these drugs might not be as effective as they expect, and their patient is not probably getting well; so, they go to unethical choice… and sell the drugs in the black market to those families who are from wealthier classes… simply we are observing an unpredicted underground market…”

Another expert from IMoH (I11) states:” [I] agree ODs are very expensive but proving them freely only means opening new doors of smuggling… I believe if we had stronger controlling mechanisms and track the usage of the drugs subsequently, we were able to provide them free… but you know, under the current condition we have some reports that the provided ODs for some patients are emerged in our neighboring countries”.

3.3. The sources of financial resources for RDs and ODs expenditure: Although about the RDs, the prevalence of the diseases is not high. However, the ODs are highly costly and should be prescribed for the lifetime of the patients. This has a considerable budget impact on the public/governmental expenditure. Therefore, there are two problems; first providing sufficient financial resources to them and then ensuring their sustainability. 8 participants asserted this as below:

An interviewee from RDFI (I13) says:” We can rely on charities financing… it is an important source though… but the fact is that the government is the main player in this field… especially if we want sustainable financial resources”.

Another one from IMoH (I6) says: “This is government’s commitment in the first instance… it might be done through an independent budget row in annual public and government’s budget… it is also important to identify which body should be responsible for taking the budget? for how many patients? and how it should be used to purchase the ODs?”

In this regard, a participant (I2) from IHIO says:” this is wrong that people think we (health insurer) must finance the RDs and ODs, we are an insurer and follow the insurance logic, simply it means we should cover more frequent diseases with reasonable and customary costs, ODs must be supported from other routes, I mean from protective and relieving ways”.

3.4. Purchasing ODs and other services:Purchasing is a process to answer what services? For what people? should be purchased from which providers? In recent years we have observed evolving of purchasing from traditional one to strategic and recently value-based purchase. Six interviewees believed that this is a real matter because of the specific needs of the RD patients.

A director of a department at IHIO (I2): “As a public health insurer we have gained very good experiences through signing contracts with a broader scale of medical centers, hospitals, [medical] laboratories, pharmacies/drug stores around the country, so we have a strong background in performing the administrative/executive affairs related to purchasing services and ODs for these patients [RD patients] on behalf of the financing bodies.”

A participant from IMoH (I14) states:” As we have defined the number of patients with clear needs, arranging effective purchasing mechanism for them is not hard to reach…however about the ODs as there is the limited number of suppliers we potentially are not in a superior position for negotiations”.

-

Including more ODs and services: The third dimension of UHC is the benefits package and including the services and ODs to meet the needs of patients. In this dimension, we face the following issues:

4.1. Developing and implementing rational criteria f or designing the benefit package: Generally, in designing the health care and services benefit package, the principle of Health Technology Assessment and economic evaluation is important. Budget impact analysis is another important aspect in this regard.

An interviewee from IKRF (I10) says:” as experts of the field [health care financing] we would like to build decisions about ODs and other cares and services for RDs for policymakers in line with equity-oriented criteria, not efficiency criteria that are traditionally used HTA methods”.

Another interviewee from SSO (I8) says:” to my knowledge it is as bright as sunshine that ODs and RDs related services are not cost-effective [he is very decisive], so what we need here is multiple criteria for decision making it can be a combination of budget impact analysis, the catastrophic and impoverishing impact of disease, the socio-economic distribution of patients, … I think this is not limited to mentioned criteria cost-effectiveness analysis…”

4.2. Reimbursement of the services and ODs: Reimbursement mechanism varies from fee-for-services to Diagnostic Related Groups (DRG), and according to the disease’s nature and characteristics of the services, it could be chosen. Each of these mechanisms has its advantages and disadvantages. For the RDs and ODs, these mechanisms may be fit as well. This helps to have more efficient and effective resource allocation in response to the needs of the patients.

A participant from IMoH (6) states:” I think as the patients’ needs to the ODs and services in terms of the types and quantities are clear, probably the DRGs as a classified reimbursement mechanism is a good choice [she doesn’t look like certain]”.

Another interviewee from IHIO (I1) mentions:” In my thoughts, this doesn’t seem the main matter. Because you know any key parameters in this regard… the number of patients by each disease, their needs to ODs and services over time, and the outcomes of them are more predictable; of course, if we have a comprehensive and updated registry and monitoring information platform”.

Discussion

The RDs and ODs financing in a country such as Iran seems a complicated one. The country’s limitations on international financial transactions itself cause a deprivation for availability and accessibility to a major part of the ODs. This is also a driver for the price jumping of ODs because of high exchange rates. Therefore, one temporary solution is to be relied on the humanitarian channels for transferring the money to buy the ODs. The high exchange rate is another problem that causes an excessive burden on the country’s ability to provide the ODs without enduring high costs.

In addition, the problems about the domestic political issue can be considered as another prohibitive factor to financing the ODs and RDs, the politicians’ approaches have not been aligned with the needs of the patients in this regard, so the country does not have an approved decree or act for supporting the patients. In the USA, some European countries, Turkey, and China, the legal frameworks for policymaking and planning of the RDs have been approved over the past years and this has given a better venue to the patients to have accessibility to their needs. In addition, this is a sign of the politicians’ commitment to the issue (24-26).

In many developing and developed countries, there are established registry systems that are working to identify and enroll the patients, and they also have their definitions of RDs as the first point for identifying the patients. China has launched it in 2016 (27). Latvia, Romania, and Ukraine are other lower-middle-income countries with established national registry systems (24).

In Iran, as previously mentioned, the definition has not been provided by any of the authorities, and they are still seeking consensus about it. Many countries have their definition of RDs or a reference definition from the other international or global identities such as the World Health Organization (WHO), or the European Union (EU). Based on the WHO’s definition RDs are recognized by a prevalence of 5 out of 10,000 population (28). EU defines RDs as health disorders that are diagnosed in 1 per 2,000 population (29).

However, in Iran, experts believe these definitions are not fitted for the context of the country, as there are a high rate of familial marriages and subsequently a high probability of genetic and other hereditary disorders that might lead to having an expanded list of the RDs that are not rare.

Extending the cost-sharing and financing of the RDs and ODs have been targeted in the different countries’ current health care financing schemes. The current situation in Iran for financing the RDs services and ODs is not well-defined as the national plan for the problem has not been developed so far. Anyway, the country’s national document for the RDs has been recently developed and approved by the government. Currently, IMoH receives financial resources from the government to provide services and drugs under its supervision to registered patients. The budget is limited and can be used for a very low proportion of the targeted patients. The IMoH also sends any confirming tests for diagnosing the RDs to Germany, and this needs a considerable financial resource as well. In addition, OHIO receives a limited marked budget for providing services and ODs for RDs patients. This budget is also not enough to extend the coverage to the other RDs patients. In Chile, a list of RDs and their related tests and services are financed based on both public and private health insurance (29). In Japan and Australia, there is a full waive for utilizing the services and ODs. In Taiwan, there is a co-payment by the patients that can be waived (1).

The other main problem regarding the financing of RDs, and ODs is about designing the benefit package. Now the Higher Health Insurance Council (HHIC) is responsible for deciding about health insurance commitments in the country it is expected this Council takes the responsibility of RDs and ODs decisions. In recent years, it has been some debates on principle for making decisions and policies on RDs in the country. Such as many of the other countries, Iran needs a comprehensive decision-making criterion (e.g., multiple criteria decisions making) to develop a benefits package for RDs and ODs. However, the problem is about the availability of convincing real-world data on RDs. In many EU countries, the governments use a set of criteria including the level of rarity of the disease, the unmet need, the budget impact, the catastrophic and impoverishing effects, and other relevant factors to decide about including a service or OD in the country’s benefits package (30).

Limitation of the Study

Because of the COVID19 pandemic, three of the interviews were done through telephone, and for the rest of the interviews, we used Google Hangouts and WhatsApp desktop version. However, due to the nature of qualitative studies, the results of in-person interviews can be more reliable. Furthermore, this study has provided the first consideration of the challenges about financing and reimbursing of ODs and RDs in Iran. Further research is required to track the progress of the ODs and RDs policy as it unfolds over time.

Conclusion

The financing of RDs and ODs in Iran is challenged by several contextual and internal factors. The political issues seem to have the main contribution of the challenge to develop an efficient and effective financing mechanism for RDs and ODs. This is especially can be related to the politicians’ commitments and pursuing an effective plan to allocate the financial resources to RDs and ODs. However, the country’s economic situation, especially at the macro level because of international limitations, has intensified the problem. The country needs a domestic definition from RDs and then a national multisectoral registry system including all stakeholders. It seems the most favored way to RDs financing is a marked or specific budget from the government. It can be completed by charities but for maintaining the sustainability of the resources, it is necessary to keep the main contribution for the government. The criteria for developing the benefits package through an equitable approach is another important factor in this context.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all people who participated this study.

Ethics approval

This study has been approved by the research and technology Deputy of Iran University of medical sciences with the ethics code: IR.IUMS.RCE.1398.711.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix. Semi-structure interview guidance for conducting dissertation entitled ‘Developing a model for rare diseases financing in Iran’

Dear Expert

Accessibility to the ODs, especially in terms of financial concerns, has always been a heated debate in the nations. The very costly Research and Development (R&D) process for manufacturing the ODs on one side and the small market size on the demand side mean that the context is not an interesting one for investment. Rare diseases-related services, care, and drugs (Orphan Drugs) in a lower-middle-income country such as Iran with international limitations due to the sanctions is a challenging issue in terms of their financing and providing. This study aims to address the financing issues related to a rare disease in Iran and provide a model of financing and reimbursement of orphan drugs and rare diseases.

I hope it gives a snapshot of what types of challenges are limiting the country to taking the RDs and ODs in policymaking and financing agenda, especially regarding the limited economic context of the country over the recent years, and I also hope it would be placed in policy-making priority agenda to Protect RDs and ODs.

Many thanks for taking the time and answering the questions precisely.

Best regards

Seyran Naghdi

Ph.D. candidate in Health Policy at Iran University of Health Sciences

Part 1. The demographic characteristics of participants .

| Full name | Gender |

| Organization | Qualification |

| Place of interview | Major |

| Years of experience | Date of interview |

| Position |

Part 2. The questions

From your view, is there any financing mechanism for rare diseases and orphan drugs in the country?

Do you think that the people who live with a rare disease have to contribute to the expenditure of treatment by considering either insurance mechanism or public found for stance with tax sources?

From your view, how can be used of non-governmental bodies for the financial protection of people who live with a rare disease?

From your view, which one of the current organizations such as the Iran Ministry of Health (IMoH), Iran Health Insurance Organization (IHIO), etc … is more appropriate to make policies for identifying the rare diseases and benefits package, enrolling criterion, monitoring the policy implementation? And why?

From your view, which one of the authorities is much more eligible to provide a list of rare diseases and orphan drugs? What kind of contribution can they have?

From your view, is the way rare disease identified is appropriate? Why?

From your view, what are the challenges regarding the orphan drugs pricing mechanism? How it should be?

From your view, what are the challenges regarding orphan drugs and health care services purchasing mechanisms? How it should be?

From your view, is it possible to identify enrolling criteria for rare diseases by considering health economics analysis solely?

From your view, which mechanisms of health care provider reimbursement for the rare disease are appropriate?

From your view, how can be mitigated exchange rate fluctuation has the minimum effect?

From your view, how the role of the providers of health care both of private and public sector should be to deliver rare diseases services?

Are there any other issues in this regard?

Cite this article as: Naghdi S, Maleki MR, Vatankhah S. Financing of Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs in A Sanctioned Country: A Qualitative Study. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2022 (11 May);36:48. https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.36.48

References

- 1.Khosla N, Valdez R. A compilation of national plans, policies and government actions for rare diseases in 23 countries. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2018;7(4):213–22. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2018.01085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song P, Gao J, Inagaki Y, Kokudo N, Tang W. Rare diseases, orphan drugs, and their regulation in Asia: Current status and future perspectives. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2012;1(1):3–9. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2012.v1.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajasimha HK, Shirol PB, Ramamoorthy P, Hegde M, Barde S, Chandru V, et al. Organization for rare diseases India (ORDI)–Addressing the challenges and opportunities for the Indian rare diseases' community. Genet Res 2014;96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Iskrov G, Miteva-Katrandzhieva T, Stefanov R. Challenges to orphan drugs access in Eastern Europe: the case of Bulgaria. Health Policy. 2012;108(1):10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shafie AA, Supian A, Ahmad Hassali MA, Ngu LH, Thong MK, Ayob H, et al. Rare disease in Malaysia: Challenges and solutions. PloS One. 2020;15(4):e0230850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Liu M, Lin J, Li B, Zhang X, Zhang S, et al. A questionnaire-based study to comprehensively assess the status quo of rare disease patients and care-givers in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01954-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morgan SG, Bathula HS, Moon S. Pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems. BMJ 2020;368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cheng A, Xie Z. Challenges in orphan drug development and regulatory policy in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Andrés-Nogales F, Cruz E, Calleja MÁ, Delgado O, Gorgas MQ, Espín J, et al. A multi-stakeholder multicriteria decision analysis for the reimbursement of orphan drugs (FinMHU-MCDA study) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01809-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Organization WH. Health financing [Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-financing#tab=tab_2.

- 11. Davaki K, Mossialos E. Financing and delivering health care. Social Policy Developments in Greece: Routledge; 2017. p. 286-318.

- 12.Myint CY, Pavlova M, Thein KNN, Groot W. A systematic review of the health-financing mechanisms in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries and the People’s Republic of China: lessons for the move towards universal health coverage. PloS One. 2019;14(6):e0217278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fernandez RM. From a Utilitarian Universal Health Coverage to an Inclusive Health Coverage. 1st ed. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 214-23.

- 14.Gustavsson E, Tinghög G. Needs and cost-effectiveness in health care priority setting. Health Technol. 2020;10(3):611–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15. The World Bank [homepage on the Internet]. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Groups. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=IR.

- 16.Harirchi I, Hajiaghajani M, Sayari A, Dinarvand R, Sajadi HS, Mahdavi M, et al. How health transformation plan was designed and implemented in the Islamic Republic of Iran? Int J Prev Med. 2020;11 doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_430_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doshmangir L, Sajadi HS, Ghiasipour M, Aboutorabi A, Gordeev VS. Informal payments for inpatient health care in post-health transformation plan period: evidence from Iran. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8432-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rare Diseases Foundation of Iran [homepage on the Internet]. Tehran: Rare Diseases National Document Rare Diseases Foundation of Iran Available from: https://radoir.org/fa/.

- 19.Schaaf J, Prokosch HU, Boeker M, Schaefer J, Vasseur J, Storf H, et al. Interviews with experts in rare diseases for the development of clinical decision support system software-a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01254-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt, Austria: SSOAR; 2014.

- 21. WHO. Universal Health Coverage Geneva World Health Organization [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc).

- 22.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovanella L, Mendoza-Ruiz A, Pilar AdCA, Rosa MCd, Martins GB, Santos IS, et al. Universal health system and universal health coverage: assumptions and strategies. Cienc Saude Colet. 2018;23:1763–76. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232018236.05562018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czech M, Baran-Kooiker A, Atikeler K, Demirtshyan M, Gaitova K, Holownia-Voloskova M, et al. A review of rare disease policies and orphan drug reimbursement systems in 12 Eurasian countries. Front Public Health. 2020;7:416. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranjini D, Basha GS, Prabakaran N. Regulatory Strategies for Orphan drug Development in USA–Europe. Res J Pharm Technol. 2021;14(6):3449–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbas A, Vella Szijj J, Azzopardi LM, Serracino Inglott A. Orphan drug policies in different countries. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2019;10(3):295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng S, Liu S, Zhu C, Gong M, Zhu Y, Zhang S. National rare diseases registry system of china and related cohort studies: vision and roadmap. Hum Gene Ther. 2018;29(2):128–35. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koçkaya G, Atalay S, Oğuzhan G, Kurnaz M, Ökçün S, Gedik ÇS, et al. Analysis of patient access to orphan drugs in Turkey. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01718-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Encina G, Castillo-Laborde C, Lecaros JA, Dubois-Camacho K, Calderón JF, Aguilera X, et al. Rare diseases in Chile: challenges and recommendations in universal health coverage context. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annemans L, Aymé S, Le Cam Y, Facey K, Gunther P, Nicod E, et al. Recommendations from the European working Group for Value Assessment and Funding Processes in rare diseases (ORPH-VAL) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0601-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]