Abstract

CD133, also known as prominin-1, was first identified as a biomarker of mammalian cancer and neural stem cells. Previous studies have shown that the prominin-like (promL) gene, an orthologue of mammalian CD133 in Drosophila, plays a role in glucose and lipid metabolism, body growth, and longevity. Because locomotion is required for food sourcing and ultimately the regulation of metabolism, we examined the function of promL in Drosophila locomotion. Both promL mutants and pan-neuronal promL inhibition flies displayed reduced spontaneous locomotor activity. As dopamine is known to modulate locomotion, we also examined the effects of promL inhibition on the dopamine concentration and mRNA expression levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc), the enzymes responsible for dopamine biosynthesis, in the heads of flies. Compared with those in control flies, the levels of dopamine and the mRNAs encoding TH and Ddc were lower in promL mutant and pan-neuronal promL inhibition flies. In addition, an immunostaining analysis revealed that, compared with control flies, promL mutant and pan-neuronal promL inhibition flies had lower levels of the TH protein in protocerebral anterior medial (PAM) neurons, a subset of dopaminergic neurons. Inhibition of promL in these PAM neurons reduced the locomotor activity of the flies. Overall, these findings indicate that promL expressed in PAM dopaminergic neurons regulates locomotion by controlling dopamine synthesis in Drosophila.

Keywords: dopamine, Drosophila, locomotion, prominin-like, protocerebral anterior medial neurons

INTRODUCTION

Locomotion is a fundamental activity of most animals, including Drosophila, and is required for navigation, mating, food sourcing, and escape from predators (Jordan et al., 2007). Sensory receptors in animals transform external visual (Creamer et al., 2018), olfactory (Tao et al., 2020), and thermal (Soto-Padilla et al., 2018) stimuli into internal information, which the central nervous system converts into an appropriate motor output (Gowda et al., 2021). In Drosophila, locomotion is affected by alteration of the internal metabolic status caused by time-restricted feeding (Villanueva et al., 2019), or by high sugar (Lee et al., 2021), high fat (Huang et al., 2020), or high salt (Xie et al., 2019) levels. The relatively simple and well-characterized central nervous system of Drosophila makes it an excellent model for studying locomotion (Scheffer et al., 2020). In addition, the evolutionarily conserved biological processes of mammalian behavior (Pandey and Nichols, 2011) facilitate the dissection of this complex process.

To date, genetic studies of Drosophila have identified several molecules and pathways involved in locomotion, many of which have conserved roles in regulating mammalian locomotion. The adult Drosophila brain contains approximately 130 dopaminergic neurons, which are organized into several clusters responsible for various functions (Yamamoto and Seto, 2014). In addition to its role in locomotion (Fuenzalida-Uribe and Campusano, 2018; Mao and Davis, 2009; Riemensperger et al., 2013), dopamine signaling in Drosophila is also involved in food-seeking (Landayan et al., 2018), learning and memory (Berry et al., 2012), addiction (Perry and Barron, 2013), courtship (Alekseyenko et al., 2010), and sleep (Kim et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2012; Ueno et al., 2012). Dopamine is synthesized from tyrosine by two enzymes, namely, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) (Sekine et al., 2011; Ueno et al., 2012; Wittkopp et al., 2002). TH converts tyrosine into L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA, also known as levodopa), a well-known medication used to treat Parkinson’s disease (Poewe et al., 2010), and then Ddc converts L-DOPA into dopamine. Loss of the gene encoding TH, the rate-determining enzyme in dopamine biosynthesis, results in decreased dopamine biosynthesis and locomotor activity in Drosophila and mice (Riemensperger et al., 2011; Zhou and Palmiter, 1995). In addition, several studies have demonstrated a role of dopaminergic protocerebral anterior medial (PAM) neurons in regulating locomotion and startle-induced climbing ability in Drosophila (Bou Dib et al., 2014; Fuenzalida-Uribe and Campusano, 2018; Riemensperger et al., 2013).

CD133, also known as prominin-1, is a pentaspan membrane glycoprotein that was first identified as a cell surface marker of neuroepithelial cells (Weigmann et al., 1997) and hematopoietic stem cells (Miraglia et al., 1997). Since then, CD133 has been used widely as a biomarker of solid tumors, including pancreatic, prostate, liver, brain, and colon cancers (Keysar and Jimeno, 2010). In this regard, previous studies have focused on the functions of CD133 in cancer, and several groups have shown that CD133 is involved in metastasis induction (Ding et al., 2014) and the maintenance of stemness (Lan et al., 2013) of cancer cells. However, given that CD133 binds to cholesterol (Röper et al., 2000) and is concentrated in plasma membrane protrusions such as microvilli (Corbeil et al., 1999), it is likely to be involved in membrane organization and signal transduction. Notably, CD133 is expressed in rod and cone photoreceptor cells, and disruption of the outer segment morphogenesis of photoreceptor cells induced by CD133 mutation or knockout results in retinal degeneration in humans (Zhang et al., 2007), mice (Zacchigna et al., 2009), and Drosophila (Nie et al., 2012). In Drosophila, the prominin-like (promL) gene encodes the mammalian counterpart to CD133. The promL gene is involved in the maintenance of mitochondrial function (Wang et al., 2019) at the cellular level, as well as the regulation of glucose metabolism, longevity (Ryu et al., 2019), lipid metabolism, and body growth (Zheng et al., 2019) at the organismal level. While metabolism and locomotion are closely related, the function of promL as a metabolic regulator in locomotion is not well known.

Here, we used the Drosophila model system to investigate the role of promL in locomotion. Mutation of promL reduced both locomotion and TH immunoreactivity in PAM dopaminergic neurons, suggesting that promL in PAM neurons regulates locomotion by controlling dopamine biosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains

Flies were cultured in cornmeal-based standard food under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle, at 25°C with 40%-60% relative humidity. The w1118 (BDSC 3605), Elav-Gal4 (BDSC 458), and PAM-Gal4 (BDSC 41347) fly stocks were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (USA), and the UAS-promL RNAi (VDRC v51957) fly stock was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (Austria). The promLΔ7 and promLΔ19 mutant fly lines have been described previously (Ryu et al., 2019).

RT-qPCR

After culture under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle at 25°C for 10 days, the heads of 20 adult flies were collected and total RNA was isolated using easy-BLUE reagent. Subsequently, RNA samples were treated with RNase-free Dnase I (TAKARA, Japan), and cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed with the StepOnePlus Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA) and SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents (Applied Biosystems). Each experiment was performed at least three times, and the comparative cycle threshold was used to generate a fold-change for each specific mRNA after normalizing to rp49 levels. The primer sequences were as follows: TH-forward, 3’-CGCCTACAAGTACGGAGACC-5’; TH-reverse, 3’-AGTCGGACATCTCCTGCAAC-5’; Ddc-forward, 3’-TGGGATGAGCACACCATCT-5’; Ddc-reverse, 3’-CGCGTAGAAGGGAATCAAAC-5’; Rp49-forward, 3’-AGATCGTGAAGAAGCGCACC-5’; Rp49-reverse, 3’-CACCAGGAACTTCTTGAATC-5’.

Immunohistochemistry

Adult fly heads were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The brains were then blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X 100 (PBST) and incubated with a murine anti-TH antibody (1:200, NB300-109; Novus Biologicals, USA) for 48 h at 4°C. After washing with PBST, the samples were incubated with an antimouse secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:400, A21441; Invitrogen, USA) overnight at 4°C. After further washing, the brains were mounted using Vectashield (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and images were acquired via confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, USA). Fluorescence intensity was analyzed using ImageJ software.

Dopamine ELISA

After culture of Drosophila under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle at 25°C for 10 days, the heads of adult male flies of the indicated genotypes were collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The fly heads were homogenized in 0.01 N hydrochloric acid containing 1 mM EDTA and 4 mM sodium metabisulfite, and then the homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and the dopamine content was determined using an ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (LDN, Germany).

Locomotion analysis

Seven-day-old male flies were collected and transferred into glass tubes (3 mm diameter) containing food at one end. The flies were maintained in an incubator under a 12:12 h light-dark cycle at 25°C, and were monitored for 3 days using the Drosophila Activity Monitoring System (TriKinetics, USA). Locomotor activity was recorded at 30 min intervals during the second day, and data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

Climbing assay

A single 7-day-old male fly of each genotype was placed in a vial (1.5 cm diameter, 20 cm length) without CO2 anesthesia. The flies were gently tapped to the bottom of the vial, and the height to which each fly climbed was measured after 10 s. The data acquired were analyzed using Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, USA).

Statistics

All experiments were performed at least three times. Statistical analyses were conducted by using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft, USA) and Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Boxplots were generated using the standard style, with the exception that the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values. In bar charts, data are presented as the mean ± SD. Comparisons of two groups were conducted using a Student’s t-test, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Comparisons of multiple groups were performed via one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise t-tests using the Bonferroni method to adjust the P value threshold for significance.

RESULTS

promL regulates locomotion in Drosophila

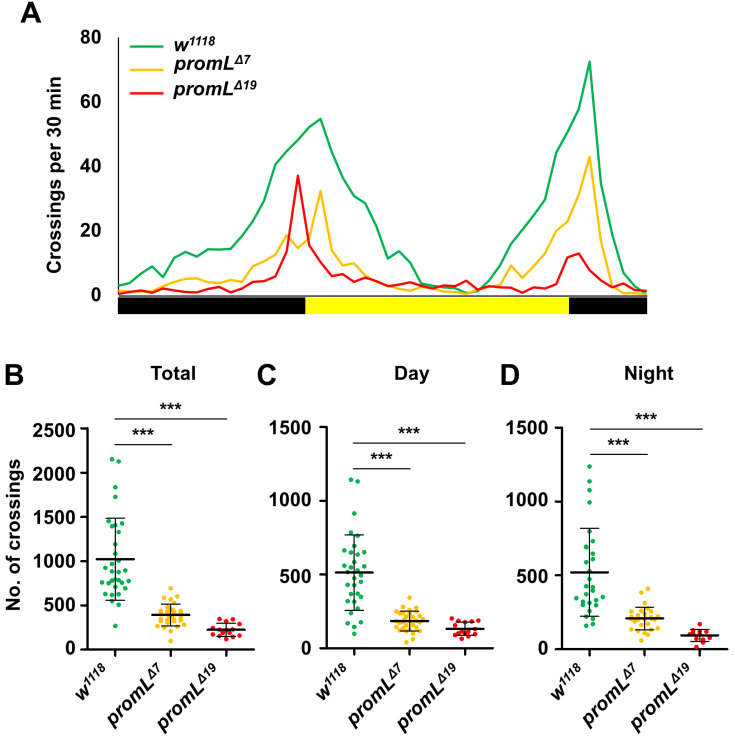

First, we analyzed the locomotion phenotypes of control (w1118) and promL mutant flies using the commercially available Drosophila Activity Monitoring System (TriKinetics), which measures the spontaneous movement of a single adult fly. Compared to that of control flies, the spontaneous locomotor activities of two promL mutants (promLΔ7 and promLΔ19) were reduced (Figs. 1A and 1B). Notably, locomotion of the promL mutants was reduced in both the daytime and night-time periods (Figs. 1C and 1D). These findings indicate that promL regulates locomotion in Drosophila.

Fig. 1. promL regulates locomotion in Drosophila.

(A) A locomotion analysis showing that the spontaneous locomotion of promLΔ7 and promLΔ19 mutants was lower than that of the w1118 control flies. (B-D) Quantification of the data shown in (A). (B) The total locomotor activities of promL mutants were lower than those of the control flies. (C and D) The daytime and night-time locomotor activities of promL mutants were lower than those of the control flies. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001.

Neuronal promL is required for locomotion

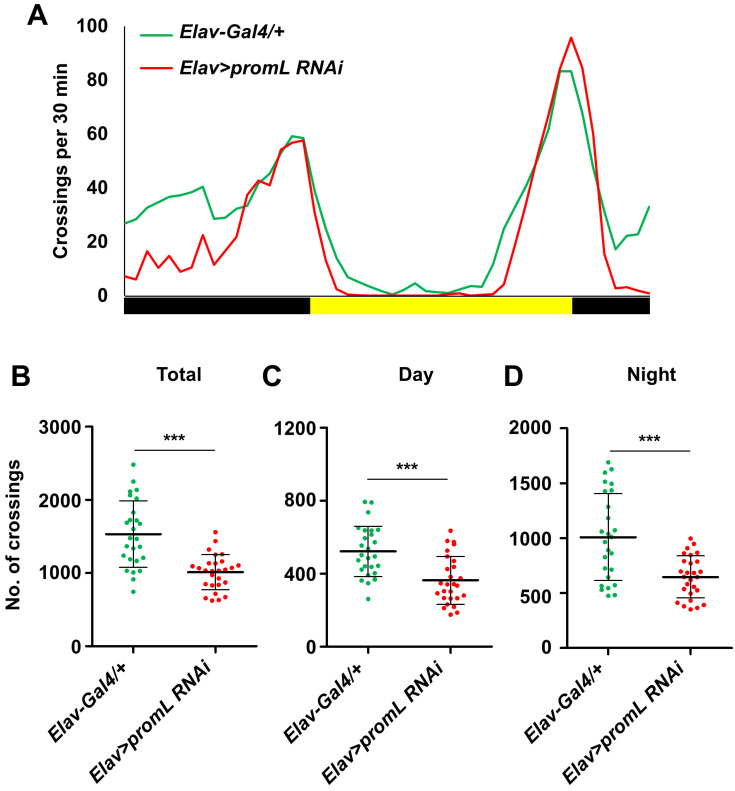

Since the brain is the control tower for various physiological processes and behaviors, including locomotion, we used the pan-neuronal Elav-Gal4 driver to determine whether neuronal promL is responsible for controlling Drosophila locomotion. RT-qPCR analyses confirmed that the expression level of promL mRNA was reduced in Elav>promL RNAi flies compared with control (Elav-Gal4/+) flies (Supplementary Fig. S1). The Elav>promL RNAi flies showed reduced total locomotion when compared to the control (Figs. 2A and 2B), and, as seen for the promL mutants, this reduction was seen in both the daytime and night-time periods (Figs. 2C and 2D). These results indicate that neuronal promL is required for locomotion in Drosophila.

Fig. 2. Neuronal promL is required for locomotion.

(A) The locomotion of Elav>promL RNAi flies was lower than that of the control (Elav-Gal4/+) flies. (B-D) Quantification of the data shown in (A). (B) The total locomotor activity of Elav>promL RNAi flies was lower than that of the control flies. (C and D) The daytime and night-time locomotor activities of Elav>promL RNAi flies were lower than those of the control flies. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001.

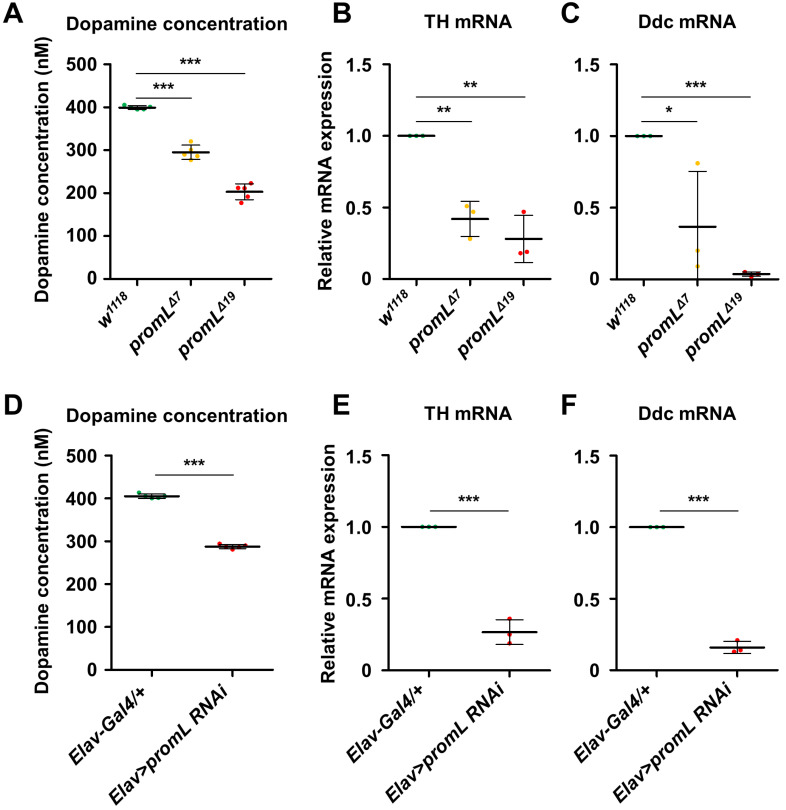

promL loss-of-function mutants show reduced dopamine biosynthesis

To determine whether the locomotion defect seen in promL mutants was due to reduced dopamine signaling, we used an ELISA to measure the dopamine concentration in adult fly heads. The dopamine concentration in both promL mutants (promLΔ7 and promLΔ19) was lower than that in the control (Fig. 3A). Since dopamine is synthesized from tyrosine by two enzymes, TH and Ddc, we examined the mRNA expression levels of these two enzymes and found that they were lower in the promL mutants than in the control flies (Figs. 3B and 3C).

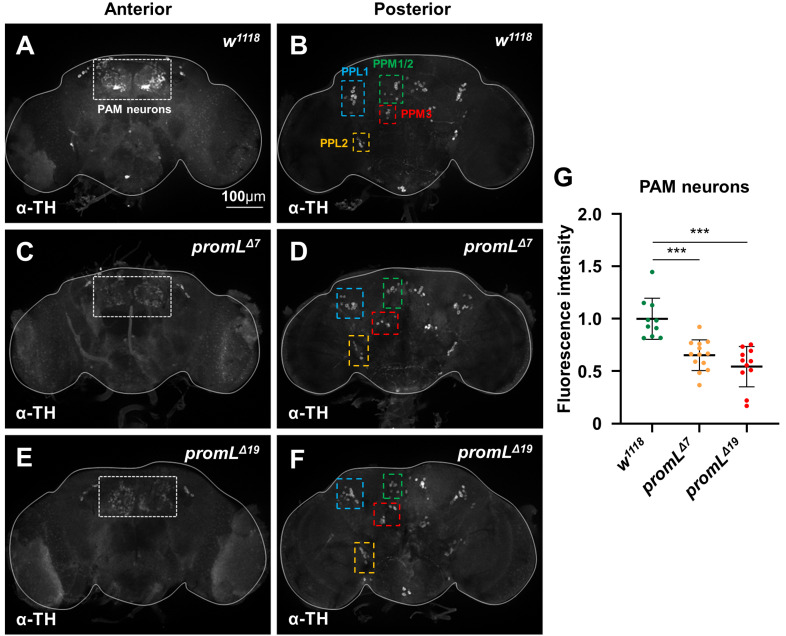

Fig. 3. promL mutants show reduced TH expression in PAM neurons.

Dopaminergic neurons in the adult fly brain were stained with an anti-TH antibody. (A, C, and E) Dashed boxes indicate PAM neurons, a subset of dopaminergic neurons. TH immunostaining of the anteriorly located PAM neurons was lower in promL mutants than in the control flies. (B, D, and F) TH immunostaining of other clusters of dopaminergic neurons located in the posterior region of the brain, showing similar patterns and intensity of TH staining between promL mutant and control flies. (G) The fluorescence intensities of PAM neurons in (A), (C), and (E) (n = 10-13). PAM, protocerebral anterior medial; PPL, protocerebral posterior lateral; PPM, protocerebral posterial medial. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001.

As seen for the promL mutants, the dopamine concentration in Elav>promL RNAi flies was lower than that in the control flies (Fig. 3D), and the mRNA expression levels of TH and Ddc were also reduced in Elav>promL RNAi flies (Figs. 3E and 3F). Overall, these findings suggest that the reduced locomotor activity in promL mutants and pan-neuronal promL inhibition flies resulted from reduced dopamine biosynthesis.

promL mutants have reduced TH expression in PAM neurons

Previous studies have shown that Drosophila dopaminergic neurons are classified into 13-15 different clusters, each of which has a different physiological role. To identify the specific dopaminergic neurons that regulate locomotion, we performed an immunohistochemical analysis of TH in the adult Drosophila brain. TH immunostaining in PAM neurons from promL mutants was significantly lower than that in PAM neurons from control flies (Figs. 4A, 4C, 4E, and 4G), while TH immunostaining in other clusters of dopaminergic neurons located in the posterior region of the brain showed similar patterns and intensity between control and promL mutant flies (Figs. 4B, 4D, and 4F). These results suggest that promL regulates dopamine biosynthesis by controlling TH production in dopaminergic PAM neurons.

Fig. 4. promL loss-of-function mutants show reduced dopamine biosynthesis.

(A) The dopamine concentration in the head was lower in promL mutants than in control flies. (B and C) The expression levels of the mRNAs encoding TH (B) and Ddc (C) were lower in promLΔ7 and promLΔ19 mutants than in w1118 control flies. (D) The dopamine concentration in Elav>promL RNAi flies was lower than that in control (Elav-Gal4/+) flies. (E and F) The expression levels of the mRNAs encoding TH (E) and Ddc (F) were lower in Elav>promL RNAi flies than in control flies. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

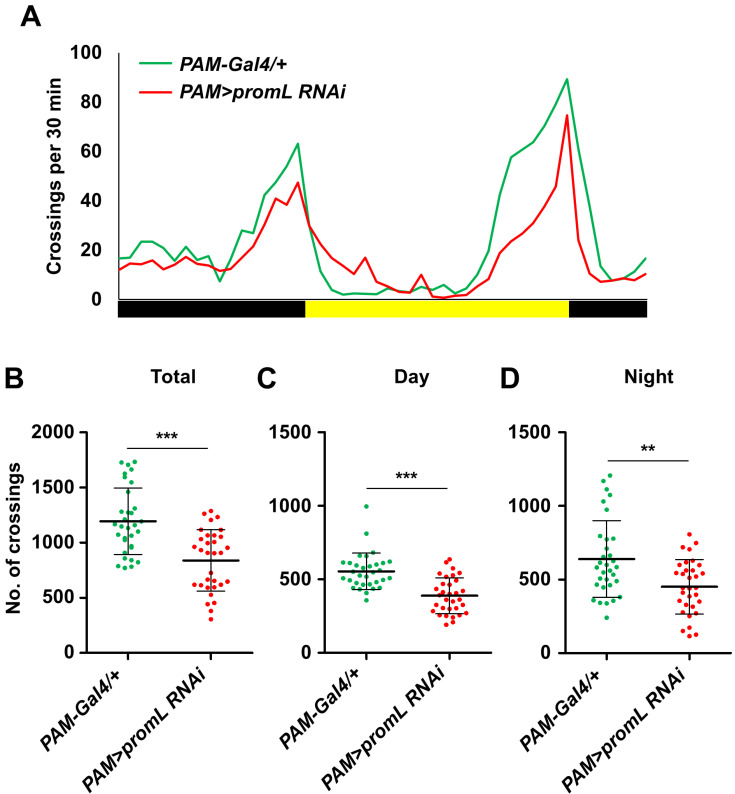

promL in PAM neurons regulates locomotion

Several studies have demonstrated that inactivation or disruption of dopaminergic PAM neurons disrupts locomotion in Drosophila. Therefore, we examined whether the reduction in locomotion seen in promL mutant flies was attributable to a dopaminergic PAM neuron-specific effect. We first confirmed expression pattern of PAM neuron-specific Gal4 by crossing PAM-Gal4 (R58E02-Gal4) with UAS-mCD8 GFP (Supplementary Fig. S2). The GFP expression pattern clearly showed that PAM-Gal4 was appropriate for the experiment.

Like the promL mutant and PAM>promL RNAi flies (displaying PAM neuron-specific promL inhibition) also showed reduced locomotion when compared with the control (Figs. 5A and 5B), and this reduction was seen in both the daytime and night-time periods (Figs. 5C and 5D).

Fig. 5. promL in PAM neurons regulates locomotion.

(A) PAM>promL RNAi flies showed reduced locomotion compared with PAM-Gal4/+ control flies. (B-D) Quantification of the data shown in (A). (B) The total locomotor activity of PAM>promL RNAi flies was lower than that of the control flies. (C and D) The daytime and night-time locomotor activities of the PAM>promL RNAi flies were lower than those of the control flies. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

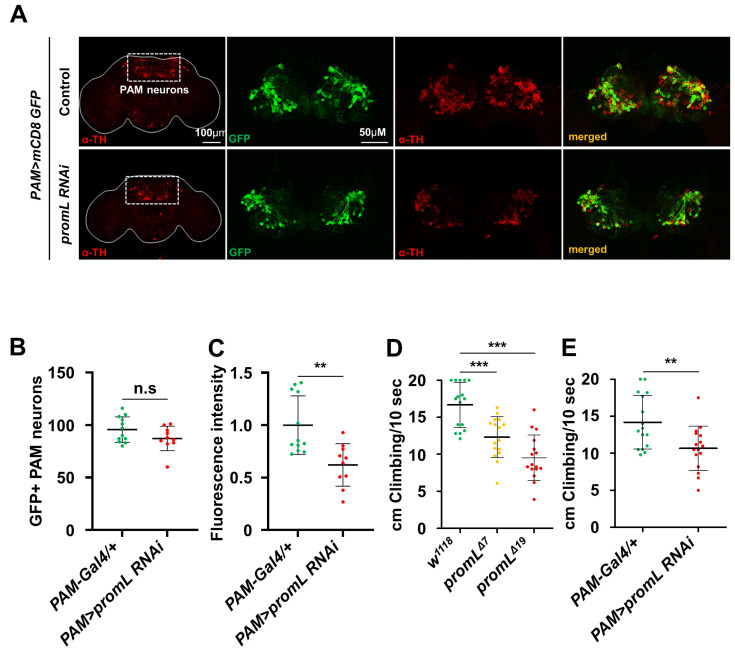

Inhibition of promL in PAM neurons reduces startle-induced climbing

First, we examined whether inhibition of promL in PAM neurons results in reduced expression of the TH protein. As seen for the promL mutants, immunostaining of TH in PAM neurons was lower in PAM>promL RNAi flies than in control flies, whereas the numbers of GFP-positive PAM neurons were similar in both groups (Figs. 6A-6C).

Fig. 6. Inhibition of promL in PAM neurons reduces startle-induced climbing.

(A) Dopaminergic PAM neurons were stained with an anti-TH antibody. (B and C) Quantification of the data shown in (A) (n = 13 and 10, respectively). (B) Immunostaining of GFP-positive PAM neurons in the brain. (C) The fluorescence intensity of the TH signal was normalized to that of the GFP signal. (D) promL mutants showed reduced startle-induced climbing ability compared with control flies. (E) PAM>promL RNAi flies showed reduced startle-induced climbing ability compared with control flies. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s, not significant.

Previous studies have shown that PAM neurons regulate startle-induced climbing ability as well as spontaneous locomotion in Drosophila. Then, we examined whether mutation or inhibition of promL in PAM neurons causes a startle-induced climbing deficit. Compared with those of the controls, the climbing abilities of both the promL mutant and PAM>promL RNAi flies were reduced (Figs. 6D and 6E). These data suggest that promL in PAM neurons regulates spontaneous locomotion and startle-induced climbing.

DISCUSSION

Since its discovery in 1997, CD133 (also known as prominin-1) has been used primarily as a stem cell biomarker. Most previous studies have focused on the functions of CD133 at the cellular level, especially in stem cells, rather than its effects on physiology and behavior at an organismal level. Recent studies in mice and Drosophila have shown that knockout of CD133 or its fly homolog, promL, results in metabolic defects. CD133-knockout mice show increased body weight and circulating glucose levels (Karim et al., 2014), and promL-knockout flies show increased lipid storage, body weight (Zheng et al., 2019), circulating glucose levels, and life span (Ryu et al., 2019). These studies on the physiological functions of CD133 have suggested that it may regulate other behaviors related to metabolism at an organismal level.

The results presented here provide evidence that promL is required for locomotion in adult Drosophila. Drosophila exhibits morning and evening peaks in locomotor activity, which are regulated by clock neurons. Previous locomotion studies in Drosophila have focused on this rhythmic behavior, and have identified several genes and neuronal networks regulating morning- or evening-specific locomotion. Here, we found that, unlike circadian rhythm regulator genes, inhibition of promL induced a locomotion defect without disrupting the bimodal peaks, suggesting that the function of promL is to regulate locomotion rather than circadian rhythmic behavior. Our findings suggest that the decreased locomotion in promL inhibition flies was caused by reduced dopamine biosynthesis in the brain.

In Drosophila, dopamine signaling in the different subsets of dopaminergic neurons regulates locomotion in different ways. Dopamine signaling in the mushroom body (Landayan et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018), fan-shaped body (Ueno et al., 2012), and PAM (Fuenzalida-Uribe and Campusano, 2018) neurons regulates locomotion by controlling startle-induced negative geotaxis, arousal, and spontaneous movement, respectively. Consistent with previous reports that PAM dopaminergic neurons are responsible for spontaneous locomotion, we found that TH protein expression in PAM neurons was reduced dramatically in promL mutants. When promL was inhibited in PAM neurons, locomotor activity was decreased, but rhythmic behavior was not affected. The latter finding may be explained by the fact that dopamine signaling was reduced in PAM neurons only, and not in the other circadian-regulating dopaminergic neurons.

Loss of dopaminergic neurons induces Parkinson’s disease (Dauer and Przedborski, 2003; Won et al., 2021), and, in humans, degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta causes serious motor dysfunctions (Shulman et al., 2011). Overexpression of human α-synuclein, a key protein involved in Parkinson’s disease, in PAM neurons results in locomotor dysfunction in Drosophila (Riemensperger et al., 2013). The lack of appropriate biomarkers has made Parkinson’s disease research difficult. Our discovery that promL regulates dopamine biosynthesis in PAM dopaminergic neurons suggests that mammalian CD133 could be used as a biomarker for motor defects of Parkinson’s disease.

Despite the evidence that promL plays a role in locomotion, additional studies are required to elucidate the mechanism underlying this phenomenon. Recent studies have demonstrated that promL regulates glucose metabolism and life span through AKT signaling. Drosophila promL mutants display reduced levels of pAKT caused by inhibition of the insulin signaling pathway (Ryu et al., 2019). In addition, studies using in vitro tumor models have shown that phosphorylation of the tyrosine 828 residue of CD133 activates AKT signaling through interaction with the p85 protein (Wei et al., 2013). AKT is involved in various signaling mechanisms and is reduced in dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease patients (Timmons et al., 2009). Since AKT was reduced in promL mutants, we speculate that promL may regulate locomotion through an AKT cascade, which in turn regulates dopamine synthesis; however, this hypothesis requires further investigation.

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate that promL, the fly homolog of the cancer stem cell biomarker CD133, plays an important role in controlling locomotion through dopamine biosynthesis in PAM dopaminergic neurons. Our work may help to elucidate the function of mammalian CD133 in dopamine signaling and Parkinson’s disease.

Supplemental Materials

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Drosophila stocks were obtained from Bloomington Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA) and Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC, Vienna, Austria). This work was supported by grants from KRIBB Research Initiative Program and National Research Foundation of Korea (2015R1A5A1009024, 2019R1A2C2004149).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.H.R. and M.S. performed the experiments, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. E.Y. discussed the results. K.Y. designed and supervised the project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Alekseyenko O.V., Lee C., Kravitz E.A. Targeted manipulation of serotonergic neurotransmission affects the escalation of aggression in adult male Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.A., Cervantes-Sandoval I., Nicholas E.P., Davis R.L. Dopamine is required for learning and forgetting in Drosophila. Neuron. 2012;74:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou Dib P., Gnägi B., Daly F., Sabado V., Tas D., Glauser D.A., Meister P., Nagoshi E. A conserved role for p48 homologs in protecting dopaminergic neurons from oxidative stress. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbeil D., Roper K., Hannah M.J., Hellwig A., Huttner W.B. Selective localization of the polytopic membrane protein prominin in microvilli of epithelial cells - a combination of apical sorting and retention in plasma membrane protrusions. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:1023–1033. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.7.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M.S., Mano O., Clark D.A. Visual control of walking speed in Drosophila. Neuron. 2018;100:1460–1473.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W., Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q., Miyazaki Y., Tsukasa K., Matsubara S., Yoshimitsu M., Takao S. CD133 facilitates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through interaction with the ERK pathway in pancreatic cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer. 2014;13:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuenzalida-Uribe N., Campusano J.M. Unveiling the dual role of the dopaminergic system on locomotion and the innate value for an aversive olfactory stimulus in Drosophila. Neuroscience. 2018;371:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda S.B.M., Salim S., Mohammad F. Anatomy and neural pathways modulating distinct locomotor behaviors in Drosophila larva. Biology (Basel) 2021;10:90. doi: 10.3390/biology10020090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., Song T., Su H., Lai Z., Qin W., Tian Y., Dong X., Wang L. High-fat diet enhances starvation-induced hyperactivity via sensitizing hunger-sensing neurons in Drosophila. Elife. 2020;9:e53103. doi: 10.7554/eLife.53103.sa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K.W., Carbone M.A., Yamamoto A., Morgan T.J., Mackay T.F. Quantitative genomics of locomotor behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R172. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim B.O., Rhee K.J., Liu G., Yun K., Brant S.R. Prom1 function in development, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal tumorigenesis. Front. Oncol. 2014;4:323. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysar S.B., Jimeno A. More than markers: biological significance of cancer stem cell-defining molecules. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2450–2457. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Jang S., Choe H.K., Chung S., Son G.H., Kim K. Implications of circadian rhythm in dopamine and mood regulation. Mol. Cells. 2017;40:450–456. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X., Wu Y.Z., Wang Y., Wu F.R., Zang C.B., Tang C., Cao S., Li S.L. CD133 silencing inhibits stemness properties and enhances chemoradiosensitivity in CD133-positive liver cancer stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013;31:315–324. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landayan D., Feldman D.S., Wolf F.W. Satiation state-dependent dopaminergic control of foraging in Drosophila. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5777. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24217-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Cho E., Yoon S.E., Kim Y., Kim E.Y. Metabolic control of daily locomotor activity mediated by tachykinin in Drosophila. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:693. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Liu S., Kodama L., Driscoll M.R., Wu M.N. Two dopaminergic neurons signal to the dorsal fan-shaped body to promote wakefulness in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:2114–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z., Davis R. Eight different types of dopaminergic neurons innervate the Drosophila mushroom body neuropil: anatomical and physiological heterogeneity. Front. Neural Circuits. 2009;3:5. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia S., Godfrey W., Yin A.H., Atkins K., Warnke R., Holden J.T., Bray R.A., Waller E.K., Buck D.W. A novel five-transmembrane hematopoietic stem cell antigen: isolation, characterization, and molecular cloning. Blood. 1997;90:5013–5021. doi: 10.1182/blood.V90.12.5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J., Mahato S., Mustill W., Tipping C., Bhattacharya S.S., Zelhof A.C. Cross species analysis of Prominin reveals a conserved cellular role in invertebrate and vertebrate photoreceptor cells. Dev. Biol. 2012;371:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey U.B., Nichols C.D. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011;63:411–436. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry C.J., Barron A.B. Neural mechanisms of reward in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013;58:543–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poewe W., Antonini A., Zijlmans J.C., Burkhard P.R., Vingerhoets F. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: an old drug still going strong. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2010;5:229–238. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemensperger T., Isabel G., Coulom H., Neuser K., Seugnet L., Kume K., Iché-Torres M., Cassar M., Strauss R., Preat T., et al. Behavioral consequences of dopamine deficiency in the Drosophila central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:834–839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010930108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemensperger T., Issa A.R., Pech U., Coulom H., Nguyễn M.V., Cassar M., Jacquet M., Fiala A., Birman S. A single dopamine pathway underlies progressive locomotor deficits in a Drosophila model of Parkinson disease. Cell Rep. 2013;5:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röper K., Corbeil D., Huttner W.B. Retention of prominin in microvilli reveals distinct cholesterol-based lipid micro-domains in the apical plasma membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:582–592. doi: 10.1038/35023524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu T.H., Yeom E., Subramanian M., Lee K.S., Yu K. Prominin-like regulates longevity and glucose metabolism via insulin signaling in Drosophila. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019;74:1557–1563. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer L.K., Xu C.S., Januszewski M., Lu Z., Takemura S.Y., Hayworth K.J., Huang G.B., Shinomiya K., Maitlin-Shepard J., Berg S., et al. A connectome and analysis of the adult Drosophila central brain. Elife. 2020;9:e57443. doi: 10.7554/eLife.57443.sa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y., Takagahara S., Hatanaka R., Watanabe T., Oguchi H., Noguchi T., Naguro I., Kobayashi K., Tsunoda M., Funatsu T., et al. p38 MAPKs regulate the expression of genes in the dopamine synthesis pathway through phosphorylation of NR4A nuclear receptors. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:3006–3016. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman J.M., Jager P.L.D., Feany M.B. Parkinson's disease: genetics and pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Padilla A., Ruijsink R., Sibon O.C.M., van Rijn H., Billeter J.C. Thermosensory perception regulates speed of movement in response to temperature changes in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2018;221:jeb174151. doi: 10.1242/jeb.174151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Xu A.Q., Giraud J., Poppinga H., Riemensperger T., Fiala A., Birman S. Neural control of startle-induced locomotion by the mushroom bodies and associated neurons in Drosophila. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2018;12:6. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2018.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L., Ozarkar S., Bhandawat V. Mechanisms underlying attraction to odors in walking Drosophila. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020;16:e1007718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons S., Coakley M.F., Moloney A.M., O' Neill C. Akt signal transduction dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;467:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T., Tomita J., Tanimoto H., Endo K., Ito K., Kume S., Kume K. Identification of a dopamine pathway that regulates sleep and arousal in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:1516–1523. doi: 10.1038/nn.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva J.E., Livelo C., Trujillo A.S., Chandran S., Woodworth B., Andrade L., Le H.D., Manor U., Panda S., Melkani G.C. Time-restricted feeding restores muscle function in Drosophila models of obesity and circadian-rhythm disruption. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2700. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10563-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zheng H., Jia Z., Lei Z., Li M., Zhuang Q., Zhou H., Qiu Y., Fu Y., Yang X., et al. Drosophila Prominin-like, a homolog of CD133, interacts with ND20 to maintain mitochondrial function. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:101. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0365-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Jiang Y., Zou F., Liu Y., Wang S., Xu N., Xu W., Cui C., Xing Y., Liu Y., et al. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway by CD133-p85 interaction promotes tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:6829–6834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigmann A., Corbeil D., Hellwig A., Huttner W.B. Prominin, a novel microvilli-specific polytopic membrane protein of the apical surface of epithelial cells, is targeted to plasmalemmal protrusions of non-epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12425–12430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp P.J., True J.R., Carroll S.B. Reciprocal functions of the Drosophila yellow and ebony proteins in the development and evolution of pigment patterns. Development. 2002;129:1849–1858. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won S.Y., You S.T., Choi S.W., McLean C., Shin E.Y., Kim E.G. cAMP response element binding-protein- and phosphorylation-dependent regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase by PAK4: implications for dopamine replacement therapy. Mol. Cells. 2021;44:493–499. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2021.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Wang D., Ling S., Yang G., Yang Y., Chen W. High-salt diet causes sleep fragmentation in young Drosophila through circadian rhythm and dopaminergic systems. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:1271. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Seto E.S. Dopamine dynamics and signaling in Drosophila: an overview of genes, drugs and behavioral paradigms. Exp. Anim. 2014;63:107–119. doi: 10.1538/expanim.63.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchigna S., Oh H., Wilsch-Bräuninger M., Missol-Kolka E., Jászai J., Jansen S., Tanimoto N., Tonagel F., Seeliger M., Huttner W.B., et al. Loss of the cholesterol-binding protein prominin-1/CD133 causes disk dysmorphogenesis and photoreceptor degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:2297–2308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Zulfiqar F., Xiao X., Riazuddin S.A., Ahmad Z., Caruso R., MacDonald I., Sieving P., Riazuddin S., Hejtmancik J.F. Severe retinitis pigmentosa mapped to 4p15 and associated with a novel mutation in the PROM1 gene. Hum. Genet. 2007;122:293–299. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Guo P., Wang X., Yuan X., Ge W., Yang R., Yan Q., Yang X., et al. Prominin-like, a homolog of mammalian CD133, suppresses dilp6 and TOR signaling to maintain body size and weight in Drosophila. FASEB J. 2019;33:2646–2658. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800123R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q.Y., Palmiter R.D. Dopamine-deficient mice are severely hypoactive, adipsic, and aphagic. Cell. 1995;83:1197–1209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.