Abstract

Background

The underutilization of immunization services remains a big public health concern. Pharmacists can address this concern by playing an active role in immunization administration.

Objective

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the impact of pharmacist-involved interventions on immunization rates and other outcomes indirectly related to vaccine uptake.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases from inception to February 2022 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies in which pharmacists were involved in the immunization process. Studies were excluded if no comparator was reported. Two reviewers independently completed data extraction and bias assessments using standardized forms. Meta-analyses were performed using a random-effects model.

Results

A total of 14 RCTs and 79 observational studies were included. Several types of immunizations were provided, including influenza, pneumococcal, herpes zoster, Tdap, and others in a variety of settings (community pharmacy, hospital, clinic, others). Pooled analyses from RCTs indicated that a pharmacist as immunizer (risk ratio 1.14 [95% CI 1.12–1.15]), advocator (1.31 [1.17–1.48]), or both (1.14 [1.12–1.15]) significantly increased immunization rates compared with usual care or non–pharmacist-involved interventions. The quality of evidence was assessed as moderate or low for those meta-analyses. Evidence from observational studies was consistent with the results found in the analysis of the RCTs.

Conclusion

Pharmacist involvement as immunizer, advocator, or both roles has favorable effects on immunization uptake, especially with influenza vaccines in the United States and some high-income countries. As the practice of pharmacists in immunization has been expanded globally, further research on investigating the impact of pharmacist involvement in immunization in other countries, especially developing ones, is warranted.

Key Points.

Background

-

•

The underutilization of immunization services remains a big public health concern.

-

•

Evidence shows a favourable impact of pharmacist involvement on immunization uptake. However, the existing literature is not comprehensive because of several limitations.

Findings

-

•

A systematic review of the literature identified fourteenth randomized controlled trials and seventy-nine observational studies from a range of country settings.

-

•

The findings demonstrated that the pharmacist involvement as immunizers or advocators or both significantly increased the immunization uptake, especially strong evidence for influenza vaccine in the United States and some high-income countries.

-

•

The findings pose a potential benefit of exploring and expanding the scope of pharmacist practice in immunization in other countries, especially low-and-middle-income countries.

Background

Immunizations are considered one of modern medicine’s greatest achievements and are estimated to save up to 2.5 million lives every year.1 Despite that, according to the World Health Organization, vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines—is one of the top 10 global health threats that result in the underutilization of immunization services.2 Apart from that, inaccessibility to vaccines or lack of understanding regarding vaccine benefits is also a potential contributor. Consequently, vaccine-preventable diseases continue to be a major concern. Worldwide, seasonal influenza has caused an estimated 3-5 million cases of severe illness and approximately 290,000-650,000 respiratory deaths annually.3,4

In the United States, pharmacists are one of the most accessible health professionals.5 In other countries, especially developing ones, pharmacists are often one of the first health professionals sought for care,6 especially with individuals who do not have access to a primary health care provider. The underutilization of vaccines along with previous influenza pandemics, such as swine flu, has led to an increased demand for immunizations. This has created opportunities for pharmacists to play a role in improving immunization rates and advancing public health.7 Stakeholders have identified 3 roles for pharmacists in immunization: pharmacists as facilitators (hosting others who vaccinate), pharmacists as advocates (educating and motivating patients), and pharmacists as immunizers (vaccinating patients).7 In the past few decades, pharmacists have been authorized to administer vaccines in all 50 U.S. states since the American Pharmacists Association established its Pharmacy-Based Immunization Delivery Program in 1996.8 Statewide protocols are methods to expand pharmacist immunization authority and provide standardized procedures for consistency and safety. These protocols are established by state laws and regulations governing the practice of pharmacy and applicable to qualified immunizing pharmacists. Despite the fact that pharmacist training and guidelines are standardized, there is large variation among statewide protocols.9 Immunization administration regulations differ by the types of vaccinations allowed, eligible patient age for administration, and allowance of prescriptive authority.9 Although all states allow pharmacists to administer vaccinations, many do so through statewide protocols, whereas some states do not have such protocols. In this case, these states have chosen to pass laws that allow pharmacists to administer vaccines without a protocol or prescription.9 The trend in the United States and increasingly in other developed countries (United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland, etc.)10,11 has been to grant greater autonomy to pharmacists in the prescribing and administering of vaccinations,12 which correlates with improved health outcomes and reduced health care costs.13 In developing countries, the pharmacists’ role in patient care, including immunization, is still limited.14 The provision of immunizations by pharmacists has had a positive effect in the United States and other developed countries13,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and may have potential applicability to other countries.

With the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has called on and highlighted the essential role of pharmacists as part of the response to the pandemic. As a result of it, pharmacist standard operating procedures were expanded to allow pharmacists to administer COVID-19 vaccines. Since then, pharmacists have played a key role in the vaccination process. As of April 2022, pharmacists have administered more than 240 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines. The federal government has recognized the key role they can play and has made them a key part of their COVID-19 vaccination plan.23

Several studies have investigated the impact pharmacist-based vaccine administration may have on influenza, pneumococcal, and herpes zoster vaccination rates.16, 17, 21, 24, 25, 26 Previous meta-analyses demonstrated pharmacist involvement in vaccine administration has a statistically significant impact on immunization rates.27,28 However, most of the studies included in these meta-analyses used weak designs, including controlled before-after, retrospective cohort, and quasi-experimental, which potentially overestimates the impact on immunization rates. Those analyses also had a large amount of heterogeneity. Moreover, the meta-analyses conducted only included a small number of trials with high risk of bias (ROB) or focused on single outcomes such as immunization uptake27 or pharmacists as immunizers.28

Objective

The purpose of this study is to conduct an updated systematic review and meta-analysis with the most recent trials to explore the impact of pharmacist involvement (i.e., as immunizer or advocator or both) on the immunization rate and other outcomes indirectly related to vaccine uptake. Other outcomes include confidence of pharmacists in vaccine recommendation/administration, perception of patients about vaccination, patient satisfaction, vaccine compliance, etc.

Methods

This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline. The systematic review protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021251119).

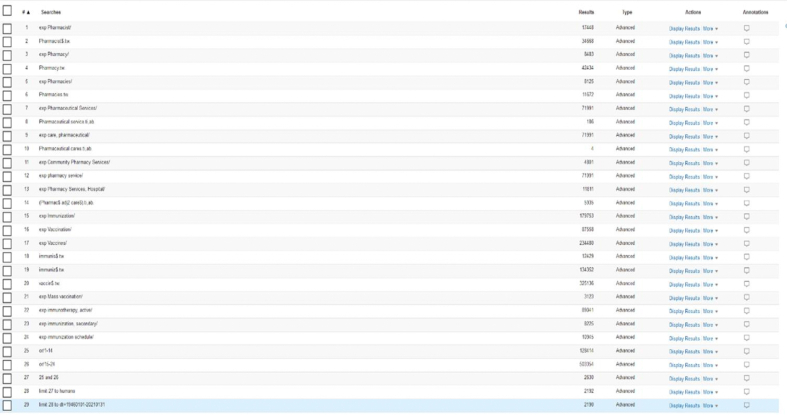

Search strategy

We performed a systematic search via MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to February 28, 2022. Search terms used were immunization, vaccination, pharmacist, pharmacy, pharmaceutical services, and pharmaceutical care. The search strategy is provided in Supplemental Materials, Supplement I. We also searched reference lists of previous systematic reviews. Duplicate studies from multiple sources were removed. Title and abstract screening and full-text screening were performed by 2 reviewers (L.M.L. and D.D.) based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify eligible studies to include in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Included studies were either randomized controlled trials (RCTs)/cluster RCTs or observational studies with a comparison group that measured immunization rate and other related outcomes that indirectly improve vaccine uptake such as improvement in vaccine hesitancy and resistance rate, vaccine appropriateness, vaccine compliance, patient’s awareness and attitude toward vaccination, patient satisfaction, etc. Immunization rate is defined as the number of people that have received vaccines divided by the target population.29 Observational studies included in this review were classified as non-RCTs, controlled before and after studies, before and after studies, retrospective cohorts, and cross-sectional surveys.30,31 Interventions needed to involve pharmacists in the immunization process as facilitators, advocators, immunizers or both advocators and immunizers.7 Comparisons of interest included usual care (defined as routine or standard of care received by patients) or other interventions without pharmacist involvement.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by 2 reviewers (D.D. and K.W.) independently using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation) to record the screening processes and decisions. In cases of discrepancy, a third reviewer (L.M.L.) was consulted to reach a consensus for the inclusion of discrepant studies. Data were extracted using standard data extraction forms. For each included study, data extracted included author name, publication year, study design, setting (community, hospital, clinic, others), population, types of vaccine, intervention, comparators, the role of pharmacists in vaccination (facilitators, immunizers, educators, etc.), number of participants in each arm, total number of cases and participants, follow-up period (mean or median), and country of each study. Data on primary outcomes were extracted using the intention-to-treat analysis principle.

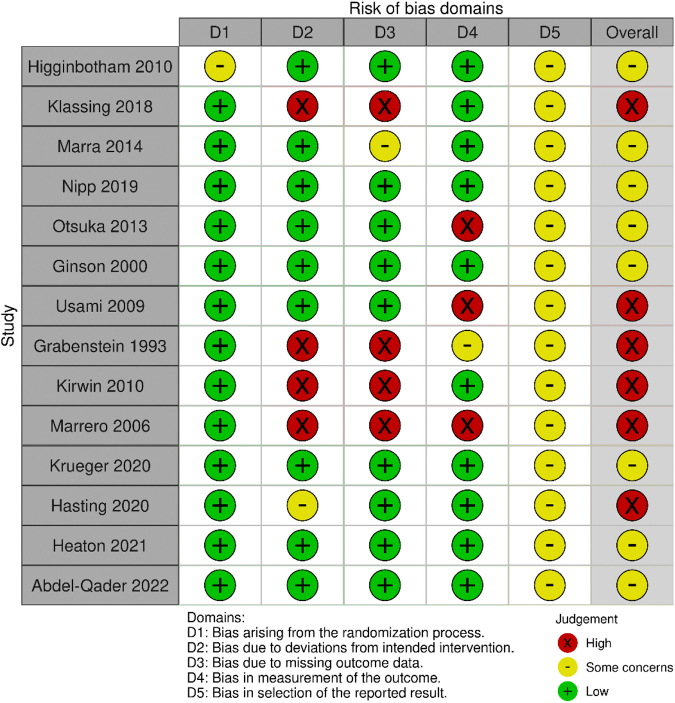

ROB assessment

For RCTs, we used the Cochrane ROB (ROB 2.0) tool (Cochrane)32 as the framework for assessing the ROB in a signal estimate of an intervention effect. Studies were judged as low ROB, some concern, and high ROB. We used the Cochrane ROB (ROBINS-I) tool (Cochrane) for nonrandomized studies.33 Studies were judged as low, moderate, serious, or critical ROB or no information.

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach was used to rate the quality of evidence (high, moderate, low, and very low) of estimates derived from meta-analyses.34,35 Two reviewers (L.M.L. and S.V.) independently assessed the confidence in effect estimates for all outcomes using the following categories: ROB, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

Data analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model under DerSimonian and Laird method.36 We estimated pooled risk ratios (RRs) of pharmacists as immunizers, advocators, or both compared with usual care or intervention without pharmacist involvement and 95% CIs incorporating heterogeneity within and between studies. The intention-to-treat principle was used for all analyses. Statistical heterogeneity between trials was assessed using I2 statistics and Q-statistics. I2 with values > 50% and Q-statistics with P value < 0.05 indicate substantial levels of heterogeneity. We assessed publication bias using funnel plot asymmetry testing and the Egger regression test. Subgroup analyses based on settings and vaccine type were also performed. To assess the robustness of the findings of our primary outcome, we performed multiple sensitivity analyses based on the following assumptions: (1) exclusion of studies with high ROB, (2) exclusion of studies reporting pharmacists with multiple roles, and (3) using the per-protocol principle (adherence to treatment). All analyses were performed with Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the designing, conducting, reporting, or disseminating of the plans for this research.

Results

Study selection

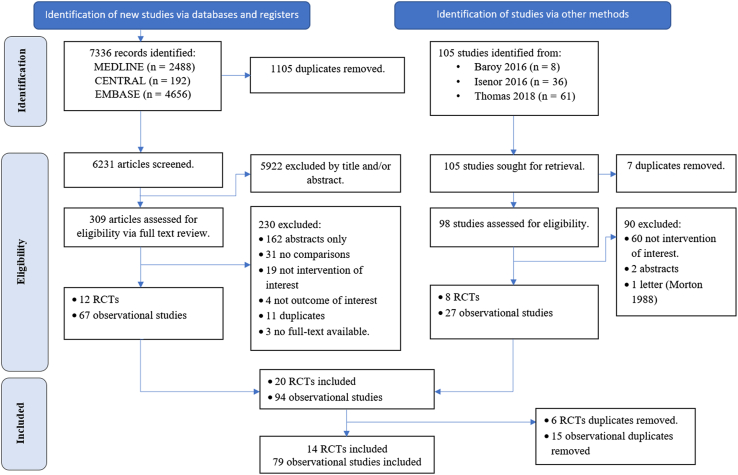

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 7336 records were identified from our literature search. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 309 studies were assessed for eligibility. We excluded a total of 230 studies for the following reasons: abstract only publications (n = 162), no comparator group (n = 31), not intervention of interest (n = 19), not outcome of interest (n = 4), duplicate reports (n =11), or no full-text available (n =3). In total, our initial search yielded 12 RCTs and 67 observational studies.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart. Abbreviations used: CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

After searching the reference lists of previous meta-analyses, we found 8 eligible RCTs and 27 observational studies. After combining the 2 sources and removing duplicates, we had a total of 14 RCTs and 79 observational studies. Of these, we included 4 RCTs37, 38, 39, 40 that were not included in previous systematic reviews.27,28

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the included RCTs. Eleven RCTs15, 16, 17,29,38,40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 assessed the impact of pharmacist involvement on immunization uptake; 1 study37 in United States investigated the change in the confidence of pharmacists in pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccine recommendation and administration after tailored training for pharmacists. Another study39 evaluated the impact of different advocating strategies in a community pharmacy setting using electronic messages and the impact on attitude of patients toward the pneumococcal vaccine in the United States. A study46 in Jordan evaluated the impact of pharmacist-physician coaching intervention about COVID-19 vaccines via Facebook lives sessions on the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis

| Author and year | Country | Study design | Setting | Intervention and comparison | Type(s) of immunization | Pharmacist role | Outcome | Duration of interventional practice | Age groups | n, treatment/control | Bias assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginson et al.,15 2000 | Canada | Cluster RCT | Hospital | Written or verbal information of vaccines from a pharmacist Comparison: usual care |

Influenza and pneumococcal | Educator/Advocator | Immunization rate | 3 mo | ≥ 65 | 50/52 | Some concerns |

| Higginbotham et al.,16 2012 | United States | RCT | Primary health care center | Compare 3 protocols: P1: administered INA only (comparison); P2: identified patients not current on immunization using INA, pharmacist recommended and administered the needed vaccines; P3: INA results and a vaccine education sheet were given to the patients | Influenza, pneumococcal, tetanus, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, MMR, varicella, meningococcal, HPV, and shingles | Immunizer | Immunization rate | 4 mo | 18–79 | P1: P2: 28 P3: 36 |

Some concerns |

| Klassing et al.,38 2018 | United States | RCT | Community pharmacy | Personal phone call, standardized mail letter Comparison: usual care |

Influenza and pneumococcal | Advocator | Immunization rate | 4 mo | ≥ 18 | Phone call: 276 Letter: 277 Control: 278 |

High risk of bias |

| Marra et al.,29 2014 | Canada | Cluster RCT | Community pharmacy | Personalized invitation letters to the eligible clients inviting them to be vaccinated at the pharmacy clinics, pharmacist educate patients on the benefits of vaccination Comparison: usual care |

Influenza | Immunizer/Educator/Advocator | Immunization rate | 2 y | ≥ 65 and < 65 | 61,623/73,626 | Some concerns |

| Nipp et al.,40 2019 | United States | RCT | Pharmacy | Pharmacists perform medication and vaccination history review, evaluate medication indications and recommend medications/vaccination Comparison: usual care |

Influenza and pneumococcal | Advocator | Immunization rate | 2 mo | ≥ 65 | 29/31 | Some concerns |

| Otsuka et al.,44 2013 | United States | RCT | General internal medicine clinic | Information on herpes zoster vaccine by electronic message or letter to personal and nonpersonal health record users, respectively. Pharmacist performed medical record review to confirm herpes zoster vaccine indication Comparison: usual care |

Herpes zoster | Advocator | Immunization rate | 6 mo | ≥ 60 | 500/2089 | Some concerns |

| Usami et al.,17 2009 | Japan | Cluster RCT | Community pharmacy | Pharmacists provide information on the risk of influenza and benefits of influenza vaccination, display posters and leaflet Comparison: usual care |

Influenza | Educator/Advocator | Immunization rate | 5 mo | ≥ 65 | 911/952 | High risk of bias |

| Grabenstein et al.,41 1993 | United States | RCT | Community pharmacy | Letters explaining the risk of influenza, and availability of vaccine Comparison: Letters advising 'poison-proof' their home and return expired or unwanted medications |

Influenza | Advocator | Immunization rate | 6 mo | ≥ 65 | 299/299 | High risk of bias |

| Kirwin et al.,42 2010 | United States | RCT | Hospital-based primary care | Personalized letter from pharmacists to physicians containing treatment recommendation for patients Comparison: usual care |

Pneumococcal | Advocator | Immunization rate | 1 mo | ≥ 65 | 171/175 | High risk of bias |

| Marrero et al.,43 2006 | Puerto Rico | RCT | Community pharmacy | Educational session about influenza and vaccination clinic in a pharmacy Comparison: usual care |

Influenza | Educator | Immunization rate | 12 mo | ≥ 65 | 40/42 | High risk of bias |

| Hasting et al.,37 2020 | United States | RCT | Community pharmacy | Immunization training for pharmacists with educational intervention and tailored feedback Comparison: 1-h immunization update |

Pneumococcal, Herpes zoster | Immunizer/Advocator | Confidence, Perceived external support, Perceived influence | 6 mo | ≥18 | 37/30 | High risk of bias |

| Krueger et al.,39 2020 | United States | RCT | Community pharmacy | Message to customers about information on pneumonia prevention, pneumococcal vaccine costs, vaccine safety, community and family duty. Comparison: usual care |

Pneumococcal | Advocator | Patients’ attitude toward vaccine | NR | ≥18 | 2211/397 | Some concerns |

| Heaton et al.,45 2022 | United States | RCT | Community pharmacy | Pharmacists are provided access to ImmsLink portal to review patient’s immunization history and recommendation. Comparison: usual care |

Influenza, Pneumococcal, Herpes zoster, Tdap | Advocator | No. vaccinations | 3 mo | ≥18 | 16,750/17,062 | Some concerns |

| Abdel-Qader et al.,46 2022 | Jordan | RCT | NA | Pharmacist-physicians coaching intervention about COVID-19 vaccines via Facebook lives Comparison: no intervention |

COVID-19 | Advocator | Vaccine hesitancy/reistance | 2 mo | ≥18 | 154/151 | Some concerns |

Abbreviations used: RCT, randomized controlled trial; INA, immunization needs assessment; MMR, measles, mumps and rubella; HPV, human papillomavirus vaccine; NR, not reported; NA, not applicable; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Two studies16,37 assessed the role of pharmacists as immunizers only, whereas 11 studies15,17,38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 assessed pharmacists as advocators only and 1 study29 for both. No eligible study was found with pharmacists as facilitators. Ten studies16,37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44,46 were RCTs; 415,17,29,45 were cluster randomized trials. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries: 9 studies16,37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42,44,45 from the United States, 215,29 from Canada, one17 from Japan, and another one43 from Puerto Rico. Only one study was conducted in an upper-middle-income economy (Jordan).46

From these studies, 17 different kinds of comparator interventions were made against pharmacist-involved interventions. Comparator strategies included pharmacists reviewing medication indication and vaccination history and recommending vaccines to patients/physicians (4 studies,16,40,42,45 23.5%), patient education (4 studies,15,17,43,46 23.5%), personalized letters (5 studies,29,38,41,42,44 29.4.%), phone calls (1 study,38 5.9%), electronic messages (2 studies,38,39 11.8%), and trainings (1 study,37 5.9%). Studies assessed a variety of different vaccines administered in adult population including influenza (9 studies15, 16, 17,29,38,40,41,43,45), pneumococcal (8 studies15,16,37, 38, 39, 40,42,45), herpes zoster (3 studies37,44,45), Td/Tdap (1 study45), and COVID-19 (1 study46). These studies were conducted primarily in 3 settings: community pharmacy (8 studies,17,29,37, 38, 39,41,43,45 57.1%), hospital (4 studies,15,40,42,44 28.6%), and a primary health care center (1 study,16 7.1%).

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the 79 included observational studies. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries: a total of 64 were conducted in the United States (81.0%), 6 in Canada (7.6%), 3 in the Australia (3.8%), 2 in United Kingdom (2.5%), and 1 in Germany (1.3%). Two studies were conducted in upper-middle-income countries: 2 from Turkey (2.5%) and 1 from Jordan (1.3%). The different study designs consisted of 31 before-after studies (39.2%), 18 retrospective cohort studies (22.8%), 17 controlled before-after studies (21.5%), 12 nonrandomized trials (15.2%), and 1 cross-sectional survey (1.3%). There were 15 studies assessing the impact of pharmacists as immunizers (19.0%), 35 as advocators (44.3%), and 2 as facilitators (2.5%). A total of 27 studies (34.1%) investigated the effect of intervention in which pharmacists served more than one role.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included observational studies

| Category | No. studies (N = 79), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| United States | 64 (81.0) |

| Canada | 6 (7.6) |

| Australia | 3 (3.8) |

| United Kingdom | 2 (2.5) |

| Turkey | 2 (2.5) |

| Germany | 1 (1.3) |

| Jordan | 1 (1.3) |

| Study design | |

| Before-after study28 | 31 (39.2) |

| Retrospective cohort study29 | 18 (22.8) |

| Controlled before-after study28 | 17 (21.5) |

| Nonrandomized trial28,29 | 12 (15.2) |

| Cross-sectional survey29 | 1 (1.3) |

| Pharmacist role | |

| Immunizer | 15 (19.0) |

| Facilitator | 2 (2.5) |

| Advocator | 35 (44.3) |

| Immunizer/advocator | 23 (29.1) |

| Facilitator/advocator | 2 (2.5) |

| Immunizer/facilitator/advocator | 2 (2.5) |

| Study setting | |

| Community pharmacy | 25 (31.6) |

| Hospital | 16 (20.3) |

| Medical center | 10 (12.7) |

| Clinic setting | 17 (21.5) |

| Other | 7 (8.9) |

| Unspecified | 4 (5.1) |

| Interventiona | |

| Patient education and motivation (pharmacist counseling, letter, phone call) | 32 (40.5) |

| Immunization eligibility/need assessment | 26 (32.9) |

| Pharmacists authorized to administer vaccine | 12 (15.2) |

| Pharmacist training | 9 (11.4) |

| Pharmacist immunization service | 8 (10.1) |

| Others | 2 (2.5) |

| Type of vaccineb | |

| Influenza | 40 (50.6) |

| Pneumococcal | 42 (53.2) |

| Herpes zoster | 12 (15.2) |

| Tdap | 10 (12.7) |

| Other | 12 (15.2) |

| Unspecified | 1 (1.3) |

| Outcomec | |

| Immunization rate | 64 (81.0) |

| Knowledge/awareness/perception | 8 (10.1) |

| Vaccine errors/appropriateness/failure | 4 (5.1) |

| Satisfaction/barrier | 8 (10.1) |

| Completion of dose/structure | 2 (2.5) |

| Cost | 3 (3.8) |

Some studies incorporated several interventions (for example: medication review was performed together with patient education).

Some studies assessed more than 1 vaccine.

Some studies reported more than 1 outcome.

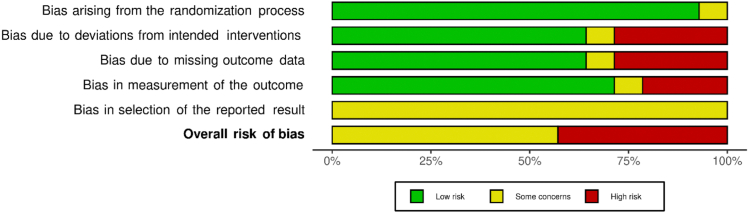

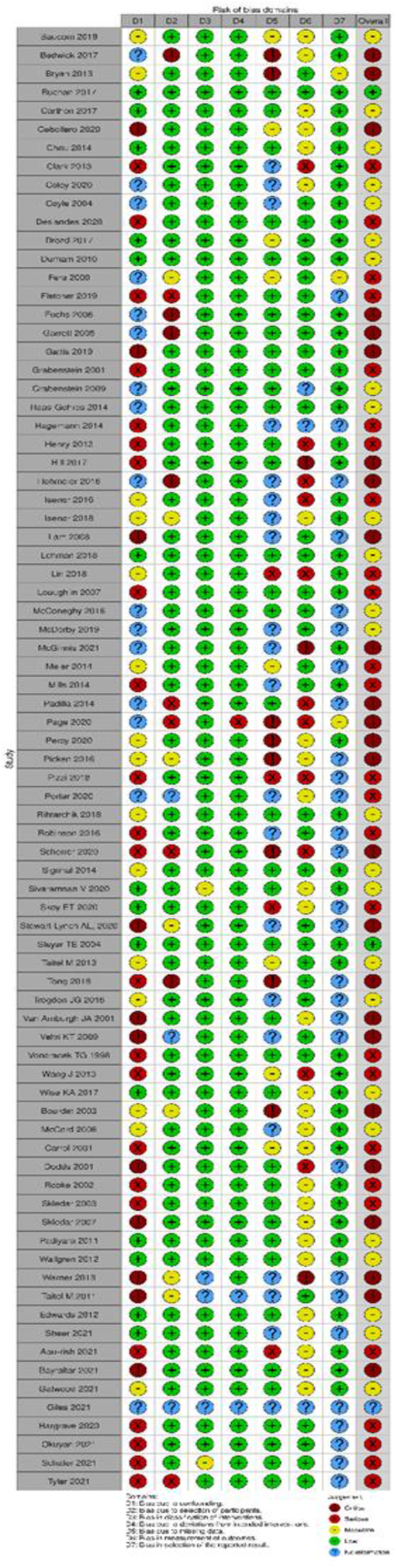

ROB assessment

A detailed description of the ROB assessment among included RCTs is presented in Supplemental Materials, Supplement II. Six studies17,37,38,41, 42, 43 were found to have an overall high ROB and 8 studies15,16,29,39,40,44, 45, 46 had some concerns. No studies were at low ROB. ROB related to the generation of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment was low for most studies except one,16 which used an alternative randomization method. By the nature of the intervention, it was impossible to blind the participants or pharmacists to the assigned intervention group. However, we did not think that it affected the deviations from the intended interventions for 7 studies.15, 16, 17,29,39,40,44 Five other studies37,38,41, 42, 43 had a loss to follow-up, so we assessed them as high ROB. Five studies29,38,41, 42, 43 had high or some concerns of ROB on missing outcome data given that their analyses were performed for the sample size after exclusion of loss to follow-up. Three studies17,41,43 were concerned about the bias of measurement of the outcome given that the outcome accessors were not blinded. All the studies had unclear risk about the selective reporting bias (Table 1; Supplemental Materials, Supplement II).

ROB assessment for observation studies is presented in Supplemental Materials, Supplements III and IV. Overall ROB was assessed as low, moderate, serious, and critical for 2 studies (2.8%), 25 studies (31.6%), 26 studies (32.9%), and 25 studies (31.6%), respectively. One study (1.3%) did not have sufficient information to assess ROB.

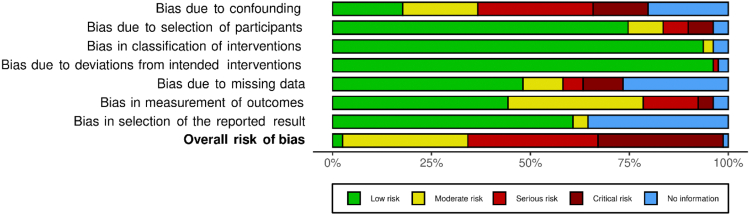

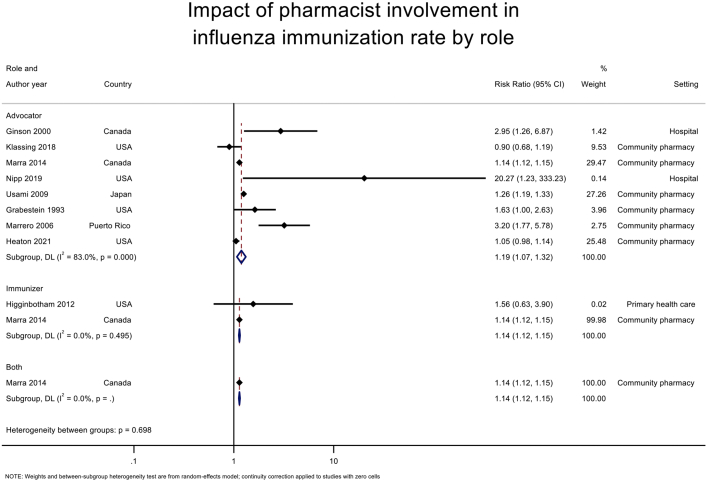

Evidence from RCTs

Pharmacists as immunizers

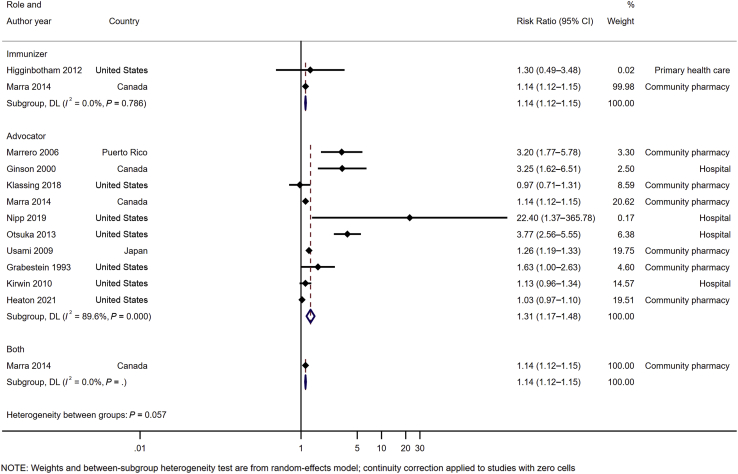

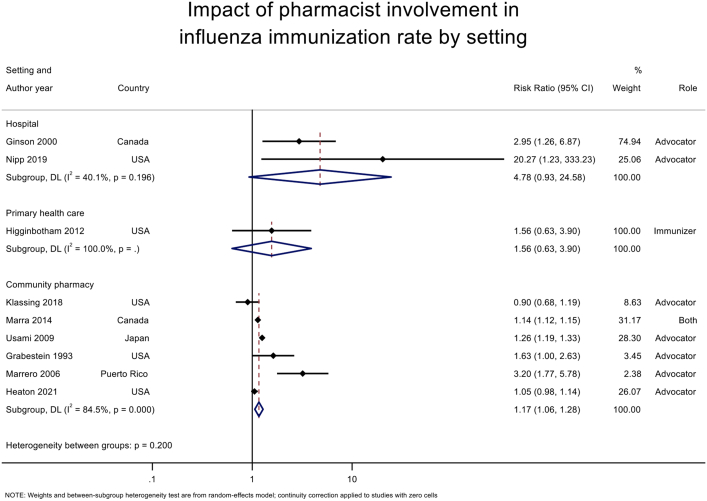

Pooled analysis of 2 RCTs16,29 (n = 135,350) (Figure 2) for pharmacists as immunizers demonstrated a statistically significant increase in immunization rate (RR 1.14 [95% CI 1.12–1.15]), favoring the intervention compared with usual care or other intervention without pharmacist involvement. No heterogeneity (P = 0.786, I2 = 0%) was observed in this analysis owing to the small number of studies included.

Figure 2.

Impact of pharmacist involvement in immunization rate of all types of vaccine by role. Abbreviation used: DL, DerSimonian and Laird method.

Pharmacists as advocators

Pooled analysis of 10 RCTS15,17,29,38,40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 (n = 175,550) (Figure 2) for pharmacists as advocators demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the immunization rate (RR 1.31 [95% CI 1.17–1.48]) compared with usual care or other intervention without pharmacist involvement. However, a high heterogeneity was observed in this analysis (P < 0.001, I2 = 89.6%).

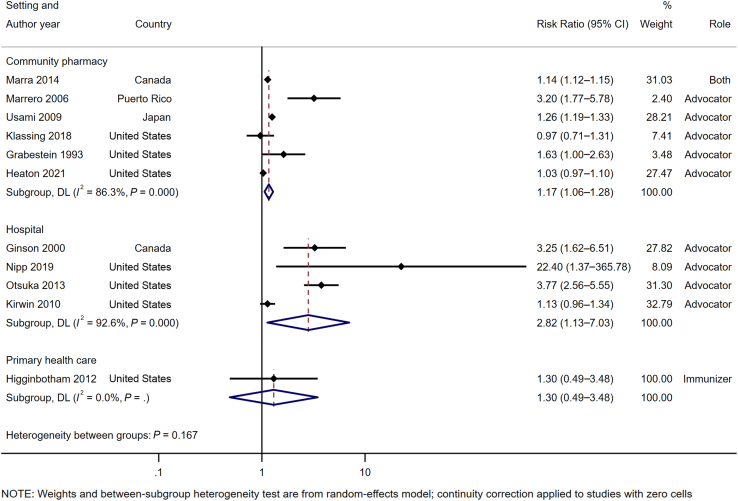

Subgroup analyses

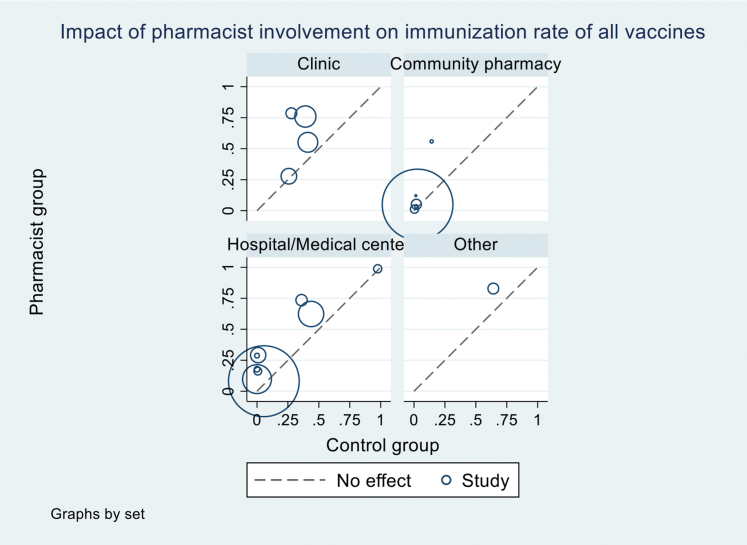

For influenza vaccine, pharmacist involvement as immunizer (RR 1.14 [95% CI 1.11–1.17], I2 = 0%) or advocator (1.19 [1.07–1.32], I2 = 83.0%) also significantly increased the immunization rates (Table 3; Supplemental Materials, Supplement V). For community pharmacy setting, pooled analysis of 6 studies17,29,38,41,43,45 (n = 172,453) (Figure 3) demonstrated that immunization intervention programs with pharmacist involvement as advocators or both advocators and immunizers significantly increased the immunization rate (1.17 [1.06–1.28], I2 = 86.3%). Subgroup analysis for influenza vaccine in community setting based on 6 RCTs17,29,38,41,43,45 also demonstrated a statistically significant increase in vaccine rate (1.17 [1.06–1.28], I2 = 84.5%) (Table 4; Supplemental Materials, Supplement VI). For hospital setting, pooled analysis of 4 RCTs15,40,42,44 (n = 3097) (Figure 3) with pharmacists as advocators demonstrated a statistically significant increase in immunization rate (2.82 [1.13–7.03], I2 = 92.6%). High heterogeneity was observed in this analysis attributed to the inclusion of a study42 with high ROB. The removal of this study42 resulted in statistically significant results (3.74 [2.67–5.22], I2 = 0%) with no evidence of heterogeneity. A similar finding was observed for influenza vaccine rate at a hospital setting (4.78 [0.93–24.58], I2 = 40.1%) (Table 4). There was only one study16 at primary health care center, and no statistically significant impact was found for this setting.

Table 3.

Summary of meta-analyses by pharmacist role

| Role of pharmacist | Primary analysis |

Sensitivity analyses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1—excluding high ROB trial |

#2—excluding trial with both role |

#3—adherence to treatment |

||||||

| # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | |

| All vaccines | ||||||||

| Immunizer | 2 | (1.14 [1.12–1.15]; 0%) | 2 | (1.14 [1.12–1.15]; 0%) | 1 | NAa | NAb | NAb |

| Advocator | 10 | (1.31 [1.17–1.48]; 89.6%) | 5 | (1.47 [1.19– 1.81]; 93.3%) | 9 | (1.52 [1.25–1.85]; 90.5%) | 6 | (1.28 [1.05–1.56]; 79.1%) |

| Influenza vaccines | ||||||||

| Immunizer | 2 | (1.14 [1.12–1.15]; 0%) | 2 | (1.14 [1.12–1.15]; 0%) | 1 | NAa | NAb | NAb |

| Advocator | 8 | (1.19 [1.07–1.32]; 83.0%) | 4 | (1.13 [1.0–1.28]; 76.5%) | 7 | (1.31 [1.08–1.59]; 84.2%) | 5 | (1.37 [1.01–1.85]; 89.3%) |

Abbreviations used: RR, risk ratio; ROB, risk of bias.

Meta-analysis was not performed owing to limited number of studies.

No available data for adherence-to-treat principle.

Figure 3.

Impact of pharmacist involvement in immunization rate of all types of vaccine by study setting. Abbreviation used: DL, DerSimonian and Laird method.

Table 4.

Summary of meta-analyses by study setting

| Study setting | Primary analysis, # studies |

Sensitivity analyses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1—excluding high ROB trial |

#2—excluding trial with both role |

#3—adherence to treatment |

||||||

| # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95% CI]; I2) | |

| All vaccines | ||||||||

| Community pharmacy | 6 | (1.17 [1.06–1.28]; 86.3%) | 2 | (1.09 [0.99–1.2]; 89.1%) | 5 | (1.24 [1.03–1.50]; 88.9%) | 3 | (1.19 [0.95–1.48]; 77.8%) |

| Hospital | 4 | (2.82 [1.13–7.03]; 92.6%) | 3 | (3.74 [2.67–5.22]; 0%) | 4 | (2.82 [1.13–7.03]; 92.6%) | 3 | (2.59 [0.81–8.21]; 86.5%) |

| Primary health care center | 1 | NAa | 1 | NAa | 1 | NAa | NAb | NAb |

| Influenza vaccines | ||||||||

| Community pharmacy | 6 | (1.17 [1.06–1.28]; 84.5%) | 2 | (1.11 [1.03–1.19]–73.8%) | 5 | (1.23 [1.02–1.47]; 86.5%) | 3 | (1.16 [0.88–1.53]; 92%) |

| Hospital | 2 | (4.78 [0.93–24.58]; 40.1%) | 2 | (4.78 [0.93–24.58]; 40.1%) | 2 | (4.78 [0.93–24.58]; 40.1%) | 2 | (5.16 [1.38–19.20]; 26.2%) |

| Primary health care center | 1 | NAa | 1 | NAa | 1 | NAa | NAb | NAb |

Abbreviations used: NA, not applicable; RR, risk ratio; ROB, risk of bias.

Meta-analysis was not performed owing to limited number of studies.

No available data for adherence-to-treat principle.

Sensitivity analyses

For pharmacists as immunizers, when excluding the study29 with pharmacists serving as both immunizers and advocators, no sensitivity analyses were performed because of a limited number of studies. For pharmacists as advocators, sensitivity analyses by excluding the high ROB trials15,17,38,41,42 and a study29 with pharmacists as both immunizers and advocators resulted in statistically significant findings (RR, 21.47 [95% CI, 1.19–1.81], 93.3%) and (1.52 [1.25–1.85], 90.5%) respectively that continued to favor the intervention with pharmacists as advocators (Table 3). Sensitivity analysis by applying adherence-to-treatment principle to 6 RCTs15,17,38,40, 41, 42 also demonstrated an increase in immunization rate (1.28 [1.05–1.56], 79.1%) (Table 3).

The effects of pharmacist involvement on other outcomes

One RCT37 assessed the impact of a 6-month tailored training program for pharmacists in community pharmacies on confidence of pharmacists in pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccine recommendation and administration and pharmacists' perceived support for these vaccines. The study indicated that the intervention had a positive impact on the outcomes which in turn may increase the immunization activities within the community setting. Another RCT39 assessed the effect of different messaging strategies (pneumonia prevention, pneumonia vaccine costs, vaccine safety, community, and family duty) for the pneumococcal vaccination to the population on the patients’ favorable attitude toward vaccines and intent to consult with the pharmacist about them. Results indicated that the message on fatality, safety, and duty to family and community increased the intent to vaccinate by 25%. A study46 assessed impact of a pharmacist-physician online coaching intervention about COVID-19 vaccines on vaccine hesitancy and resistance. Findings demonstrated that the intervention improved participants’ attitude and knowledge toward COVID-19 vaccines and reduced significantly the vaccine hesitancy and resistance rate.

Quality of evidence from RCT

Overall, the quality of evidence was low to moderate (Table 5). The quality of evidence for pharmacists as immunizers was graded as moderate quality. We also found a moderate quality of evidence for pharmacists as advocators in the community setting but only for the influenza vaccine.

Table 5.

GRADE for primary and subgroup analyses

| Outcome | Pharmacist role | Illustrative comparative risksa |

RR (95% CI) | No participants, (No studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed riska |

Corresponding riska |

|||||

| Usual care | Pharmacist intervention | |||||

| Primary analysis by pharmacist role at any setting for all vaccines | ||||||

| Immunization rate of all vaccines | Immunizer | 34 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 | RR 1.14 (1.12–1.15) | 135,350 (2 studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯b MODERATE |

| Advocator | 69 per 1000 | 90 per 1000 | RR 1.31 (1.17–1.48) | 175,550 (10 studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯c LOW | |

| Subgroup analysis by pharmacist role at community pharmacy | ||||||

| Immunization rate of all vaccines | Immunizer | NAd | NAd | NAd | NAd | NAd |

| Advocator | 43 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 | RR 1.17 (1.06–1.28) | 172,453 (6 studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯e MODERATE | |

| Immunization rate of influenza vaccines | Immunizer | NAd | NAd | NAd | NAd | NAd |

| Advocator | 49 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 | RR 1.17 (1.06–1.28) | 150,946 (6 studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯e MODERATE | |

| Subgroup analysis by pharmacist role at hospital | ||||||

| Immunization rate of all vaccines | Immunizer | NAd | NAd | NAd | NAd | NAd |

| Advocator | 7 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 | RR 2.82 (1.13–7.03) | 3097 (4 studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯e MODERATE | |

| Immunization rate of influenza vaccines | Immunizer | NAa | NAa | NAa | NAa | NAd |

| Advocator | 7 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 | RR 4.78 (0.93–24.58) | 162 (2 studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯f LOW | |

Abbreviations used: GRADE, Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR, risk ratio; NA, not applicable.

The basis for the assumed risk (eg. the median or mean of control group risk across studies). The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention.

Moderate-quality evidence is caused by indirectness (different study setting – community pharmacy and primary health care).

Low-quality evidence is caused by inconsistency (high heterogeneity) and publication bias.

Meta-analysis was not performed owing to limited number of studies.

Moderate-quality evidence is caused by inconsistency (high heterogeneity).

Low-quality evidence is caused by imprecision (very small sample size).

Evidence from observational studies

Vaccination rate was increased in all 64 studies comparing the pharmacists’ involvement with usual care or other intervention without pharmacists. We performed pooled analyses from observational studies to investigate the impact of pharmacists in immunization activities on vaccine uptake and found consistent findings with meta-analyses from RCTs (Supplemental Materials, Supplement VII). Pooled analysis of 9 observational studies47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 (n = 2,676,385) for pharmacists as immunizers demonstrated a statistically significant increase in immunization rate (RR 2.17 [95% CI 1.71–2.75], I2 = 97.7%), favoring the intervention compared with usual care or other intervention without pharmacist involvement. Pooled analysis of 17 studies25,47,48,50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 (n = 2,643,385) for pharmacists as advocators demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the immunization rate (2.01 [1.66–2.44], I2 = 99%) compared with usual care or other intervention without pharmacist involvement. A similar finding was observed for influenza vaccine rate with pharmacists as immunizers (3 studies49, 50, 51, n =5561) (2.15 [1.16–4.02], I2 = 98.2%) and advocators (6 studies50,56,60,61,63,64, n = 11,331) (2.02 [1.37–2.98], I2 = 92.1%). Pooled analyses by study setting indicated that pharmacist participation in immunization at any setting significantly increased the immunization rate of all type of vaccines (Supplemental Materials, Supplement VIII). The quality of evidence was assessed from low to very low (Supplemental Materials, Supplement IX). For other outcomes, interventions with the participation of pharmacists had an impact on the improvement of vaccine appropriateness (selection of vaccine based on individual patient criteria), vaccine compliance, patients’ awareness and attitude toward vaccination, and patients’ satisfaction. A study65 estimating cost per vaccine administration indicated that the average direct costs per adult immunization were lower in pharmacies compared with physician offices or other medical settings by 16%-26% and 11%-20%, respectively. A reference list of included observational studies can be found at Supplemental Materials, Supplement X.

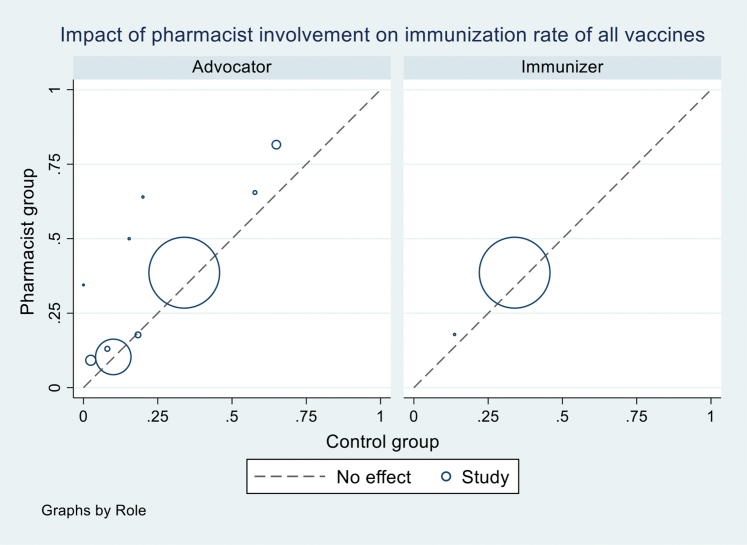

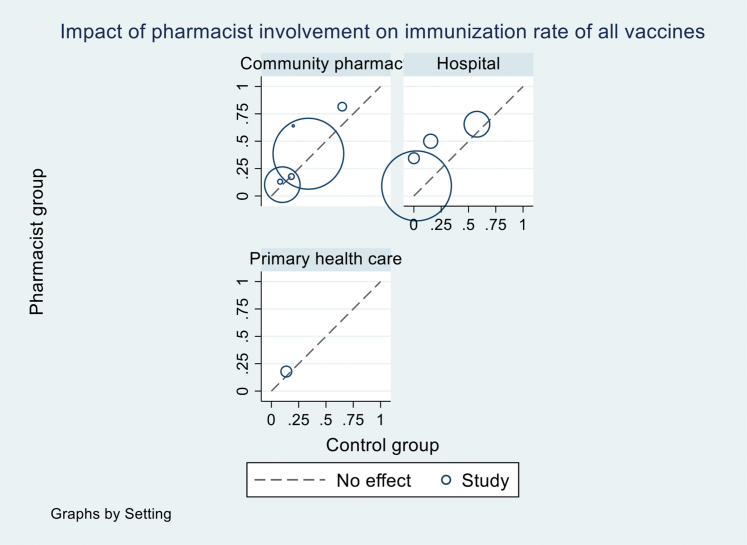

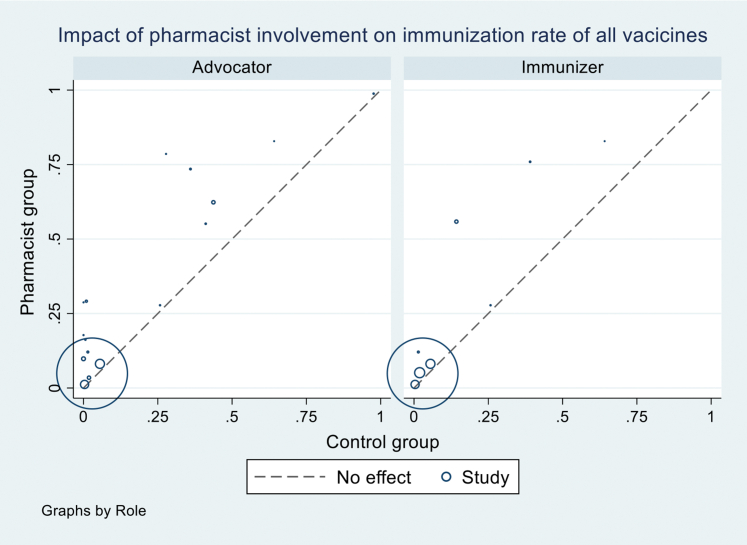

Heterogeneity exploration

We explored the source of heterogeneity by conducting subgroup analyses by vaccine types (all vaccines vs. influenza vaccines) and study settings (Tables 3 and 4; Supplemental Materials, Supplements VII and VIII) but could not identify the reasons. Sources of heterogeneity were also explored using univariate meta-regression for RCTs and observational studies of the following variables: pharmacist role, intervention, comparison, study setting, type of vaccines, number of vaccines investigated, country, and ROB. None of them were found to explain heterogeneity with the I2 ranging from 97%-99% in meta-regressions (Supplemental Materials, Supplements XI and XII). We also generated a L’Abbé plot (Supplemental Materials, Supplements XIII and XIV) and found that differences in the relative effect of intervention across studies were not associated with differences across control groups.

Discussion

Vaccination is one of the most effective public health interventions to mitigate the burden of disease and saves millions of lives per year.1 Several studies have demonstrated the favorable impact of pharmacists, one of the most accessible health professionals, on immunization.16,27,28,44,66, 67, 68, 69 We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacist involvement in immunization rates (facilitators, advocators, or immunizers) compared with usual care or other intervention/services without pharmacists. Findings from both RCTs and observational studies indicated that the involvement of pharmacists in the immunization process regardless of their roles or vaccine provided had a substantial impact on immunization rate. Evidence from RCTs demonstrated that pharmacist participation in vaccination activity in both community and hospital settings had a positive impact on immunization rate, particularly for influenza vaccine in community settings. Evidence from observational studies indicated that pharmacist interventions improved the immunization uptake of all vaccines including influenza vaccine at any setting. We performed a series of sensitivity analyses for both RCTs and observational studies and observed that our results were robust. All sensitivity analyses indicated statistically significant impact of pharmacist involvement on immunization rate that were in line with the main finding (Tables 3 and 4; Supplemental Materials, Supplements VII and VIII). Pharmacist involvement also had a favorable effect on other outcomes such as vaccine appropriateness, vaccine compliance, vaccine hesitancy, patient awareness and attitude toward immunization, and patient satisfaction, which in turn may increase the vaccine uptake.

The results of this study using data from the most recent trials were consistent with the findings from previous meta-analyses26,28 and addressed the importance of pharmacists’ participation in improving public health issues such as immunization. Although the evidence was from high-income countries, mostly from the United States, the positive impact of pharmacists on vaccine uptake suggested the benefit of expanding the scope of pharmacist practice in terms of vaccine administration and immunization advocating activities at a variety of settings at the global scale. The global shifting trend from providing product-centered services to patient-centered services such as immunization has been happening in pharmacist practice for years.6

Pharmacist involvement in immunization process varies globally. The United States is advanced in involving pharmacists in immunization process such as hosting patients (which means providing venue for patients coming for vaccination), storing vaccines, or communicating with physicians and nurses since the mid-1800s,5 but it was more than a decade that pharmacists’ role has progressed from being vaccine facilitator and advocator to becoming vaccine immunizers.70 Today, all states allow trained pharmacists to administer vaccines.8 Following the United States, some developed countries, including Canada, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Portugal, Ireland, and Australia, have authorized pharmacists to administer vaccines.71 Recently, in 2018, health professionals from 20 countries gathered in a conference on “Pharmacy-based interventions to increase vaccine uptake” in Venice to present evidence-based review of vaccination administration authorization for pharmacists and discuss opportunities for further expansion of pharmacist role in immunization globally.72 They reported higher immunization rates in countries that authorized pharmacists to administer vaccines such as United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, and Portugal compared with countries that did not authorize. Other countries such as Estonia, Croatia, Spain, and Malta shared their benefits from the additional participation of pharmacists in immunization activities.72, 73, 74 These countries are accompanied with the high visibility and accessibility of community pharmacies, and pharmacists are one of the first health professionals individuals turn to when seeking health care.75 Thus, in these countries, pharmacists can play a critical role in the prevention, control, and management of high-incidence vaccine-preventable infections and to assist during disease outbreaks and pandemics. They can easily identify patients at higher risk and specific target groups for vaccination, providing necessary counseling and actively participating in reminder and recall systems to ensure that vaccination schedules are met.6,71 Although such services have been provided by community pharmacists in these high-income countries, other countries, especially low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), have started to explore and expand the scope of pharmacist practice in public health, especially in immunization. In these LMICs, although pharmacists have participated in patient management care in community pharmacy or primary health care settings, the role of pharmacists in immunization has not been well defined as yet, mostly owing to regulatory obstacles, financial shortage, and lack of professional training programs on immunization for pharmacists.6,72 This finding favors the implementation of pharmacy-based immunization in other countries, especially ones in low-resource settings where immunization programs rely on public health institutions (hospitals, medical centers or clinics, etc.) or individual physicians to deliver vaccines.23 Although providing immunization services at public health institutions is effective in reaching children, older people, or people with chronic diseases within their medical visits, adult populations in remote areas who do not receive routine health care services are likely to have poor accessibility to immunization services.23 A lack of coordination between vaccination and curative health services and incomplete vaccination during vaccination visits were reported as the causes of missed opportunities for vaccines in public health facilities.76 Fees for immunizations create an important barrier to vaccinations in public facilities in low-resource setting.77 Moreover, in these developing countries, hospitals and clinics are often overburdened leading to long waits and missed opportunities for vaccination.77 Those countries would benefit from additional participation by pharmacists in the immunization process.73,74

The 2021-2025 Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization 5-year strategy has 4 goals, in which the equity goal focus is to “help countries extend immunization services to regularly reach under-immunized and zero-dose children to build a stronger primary health care platform.”78 Based on our review, given their accessibility, qualification, and experience in patient management care, pharmacists, especially those who work in community pharmacies or primary health care settings in developing countries, would play the critical role to achieve this global immunization effort.

In the context of COVID-19 pandemic, pharmacies worldwide are one of the few places that are kept open for public service even during the strict lockdowns. Community pharmacists are a vital health care provider during the outbreak and are highlighted the essential role of pharmacists as part of the response to the pandemic. To addressing the vaccination efforts, pharmacists were the first profession targeted for expanded scope of practice in the United States. The Federal Retail Pharmacy Program for COVID-19 Vaccination is a collaboration among the federal government, states and territories, and 21 national pharmacy partners and independent pharmacy networks to increase access to COVID-19 vaccination across the United States.79

Strengths of this review include the comprehensive search strategy with the inclusion of studies in previous meta-analyses and the most data from recent trials and evidence from observational studies to provide updated findings. Moreover, besides the main outcome, which was immunization uptake, this study assessed the impact of pharmacist involvement in the immunization process on other related outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. Owing to a small number of RCTs for other related outcomes, we were unable to pool the findings. Another limitation was the high heterogeneity of the advocating interventions. We explored the source of inconsistency by the study setting, type of vaccine, or type of intervention. Heterogeneity was affected by these factors but, overall, it was still high for pharmacist as advocators. In addition, there were several studies that were graded as having a high or critical ROB. However, we do not think it affected our findings given that all sensitivity analyses excluding these studies resulted in statistically significant findings that continued to favor the intervention with pharmacists for both RCTs and observational studies. Finally, the findings may not apply for all health care systems given that the data for this study were mostly from the United States and some high-income and upper-middle-income countries. The impact may vary for different countries, but it poses the potential benefit of the implementation of pharmacy-based immunization for other countries, especially low-resource ones.

Conclusion

Pharmacist involvement as immunizer, advocator, or both roles has favorable effects on immunization uptake, especially strong evidence for influenza vaccine. In addition, interventions with pharmacist involvement also had an impact on other related outcomes (patient attitude toward vaccines, pharmacist confidence in vaccine recommendation and administration, vaccine compliance and appropriateness, and patient satisfaction), which indirectly improves the vaccine coverage. Pharmacists could play a key role in public health responses, such as what they have demonstrated with the COVID-19 epidemic, help address concerns with vaccine hesitancy, and have a positive impact on immunization uptake during any future pandemics. Pharmacists have the potential to play an important role in increasing access to vaccines and improving coverage, yet evidence of their role in vaccinations remains limited in LMICs. LMICs should try to expand the role of pharmacists as advocators or immunizers to offer vaccination services based on the present findings. Greater documentation of pharmacist involvement in vaccination services in LMICs is needed to demonstrate the value of successful integration of pharmacists in immunization programs.

Biographies

Le My Lan, PhD, Research Fellow, Department of Pharmacotherapy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Sajesh K. Veettil, PhD, Research Fellow, Department of Pharmacotherapy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Daniel Donaldson, PharmD, Student Pharmacist, Department of Pharmacotherapy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Warittakorn Kategeaw, PharmD, Research Assistant, Department of Pharmacotherapy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Raymond Hutubessy, PhD, MSc, Team Lead, Value of Vaccines, Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals (IVB), World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Philipp Lambach, MD, PhD, MBA, Team Lead, Value of Vaccines, Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals (IVB), World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Nathorn Chaiyakunapruk, PharmD, PhD, Professor, Department of Pharmacotherapy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

Footnotes

Disclosures: Philipp Lambach and Raymond Hutubessy work for the World Health Organization. The authors declare no other relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the World Health Organization.

Funding: This study is funded by the World Health Organization (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization Initiative for Vaccine Research [U50CK000431]).

Registration: The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews registration number is CRD42021251119.

Ethics approval statement: This study does not involve human participants and animal subjects.

Data transparency: Data were extracted from published articles, all of which are available and accessible.

Data sharing statement: Review protocol has been available via the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews website. All extracted and calculated data are available upon appropriate requests by emailing to the co-corresponding author.

Supplementary materials

Supplement I: Search results and updated search results

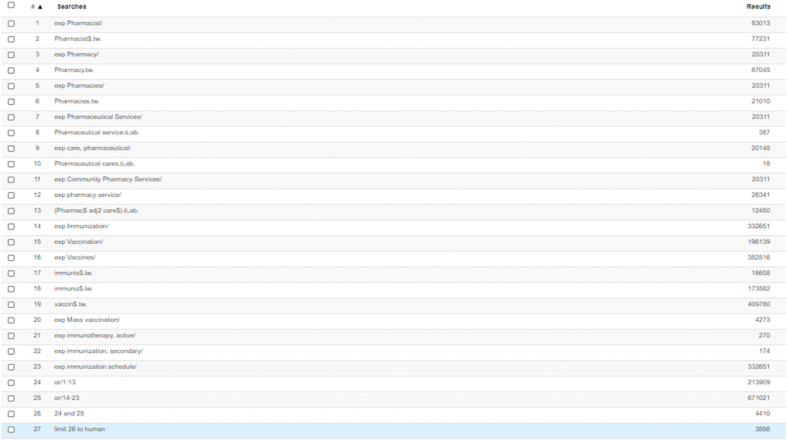

Database: Ovid Medline, Embase (conducted 27 Feb 2021)

Inception to 31 Jan 2021

| No | Search term | Ovid Medline | Embase |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Pharmacist/ | 17448 | 83013 |

| 2 | Pharmacist$.tw. | 34668 | 77231 |

| 3 | exp Pharmacy/ | 8483 | 20311 |

| 4 | Pharmacy.tw. | 42434 | 87045 |

| 5 | exp Pharmacies/ | 8125 | 20311 |

| 6 | Pharmacies.tw. | 11672 | 21010 |

| 7 | exp Pharmaceutical Services/ | 71991 | 20311 |

| 8 | (Pharmaceutical service).ti,ab. | 186 | 387 |

| 9 | exp care, pharmaceutical/ | 71991 | 20148 |

| 10 | (Pharmaceutical cares).ti,ab | 4 | 18 |

| 11 | exp Community Pharmacy Services/ | 4801 | 20311 |

| 12 | exp pharmacy service/ | 71991 | 26341 |

| 13 | exp Pharmacy Services, Hospital/ | 11811 | |

| 14 | (Pharmac$ adj2 care$).ti,ab. | 5935 | 12450 |

| 15 | exp Immunization/ | 179753 | 332651 |

| 16 | exp Vaccination/ | 87558 | 196139 |

| 17 | exp Vaccines/ | 234480 | 382516 |

| 18 | immunis$.tw. | 12429 | 16608 |

| 19 | immuniz$.tw. | 134352 | 173562 |

| 20 | vaccin$.tw. | 325136 | 409780 |

| 21 | exp Mass vaccination/ | 3123 | 4273 |

| 22 | exp immunotherapy, active/ | 89041 | 270 |

| 23 | exp immunization, secondary/ | 8225 | 174 |

| 24 | exp immunization schedule/ | 10945 | 332651 |

| 25 | or/1-14 | 128414 | 213909 |

| 26 | or/15-24 | 503354 | 671021 |

| 27 | 25 AND 26 | 2630 | 4410 |

| 28 | Limit 27 to humans | 2192 | 3856 |

| 29 | Limit 28 to (dt=19460101-20210131) | 2190 |

Search results

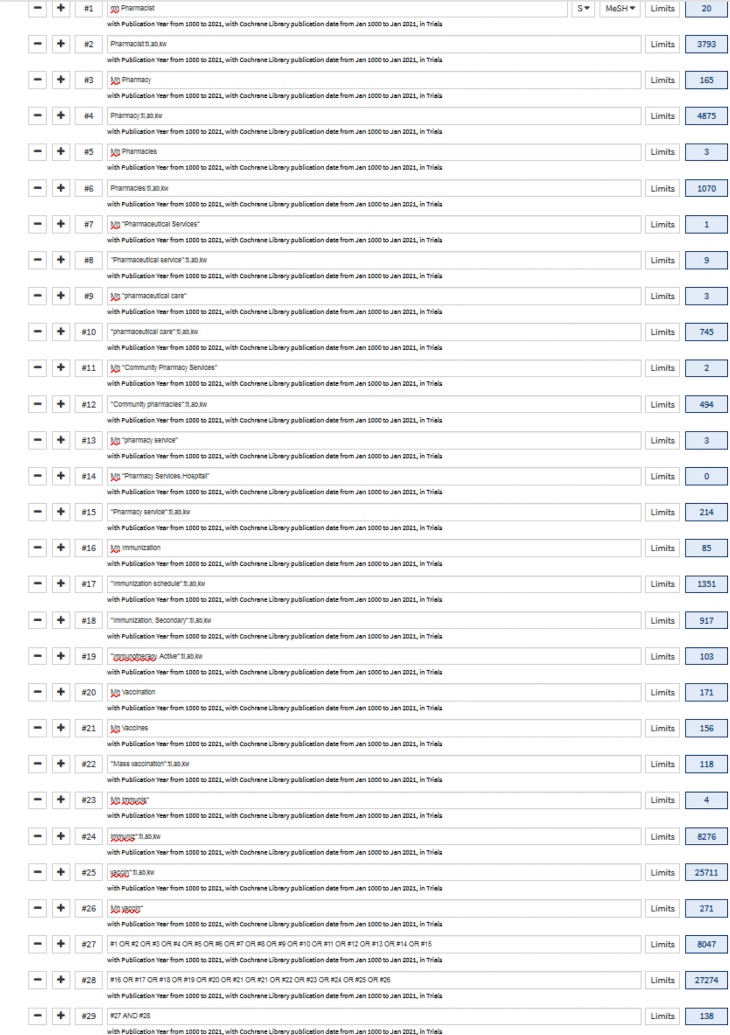

Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (conducted 27 Feb 2021)

Inception to 31 Jan 2021

| No. | Search term | CENTRAL |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mh Pharmacist | 20 |

| 2 | Pharmacist:ti,ab,kw | 3793 |

| 3 | Mh Pharmacy | 165 |

| 4 | Pharmacy:ti,ab,kw | 4875 |

| 5 | Mh Pharmacies | 3 |

| 6 | Pharmacies:ti,ab,kw | 1070 |

| 7 | Mh “Pharmaceutical Services” | 1 |

| 8 | “Pharmaceutical service”:ti,ab,kw | 9 |

| 9 | Mh “pharmaceutical care” | 3 |

| 10 | “pharmaceutical care”:ti,ab,kw | 745 |

| 11 | Mh “Community Pharmacy Services” | 2 |

| 12 | “Community pharmacies”:ti,ab,kw | 494 |

| 13 | Mh “pharmacy service” | 3 |

| 14 | Mh “Pharmacy Services,/Hospital” | 0 |

| 15 | “Pharmacy service”:ti,ab,kw | 214 |

| 16 | Mh Immunization | 85 |

| 17 | “Immunization schedule”:ti,ab,kw | 1351 |

| 18 | “Immunization, Secondary”:ti,ab,kw | 917 |

| 19 | “Immunotherapy, Active”:ti,ab,kw | 103 |

| 20 | Mh Vaccination | 171 |

| 21 | Mh Vaccines | 156 |

| 22 | “Mass vaccination”:ti,ab,kw | 118 |

| 23 | Mh immunis∗ | 4 |

| 24 | immuniz∗:ti,ab,kw | 8276 |

| 25 | vaccin∗:ti,ab,kw | 25711 |

| 26 | Mh vaccin∗ | 171 |

| 27 | or/1-15 | 8047 |

| 28 | or/16-26 | 27274 |

| 29 | 27 AND 28 | 138 |

Search results – Ovid Medline

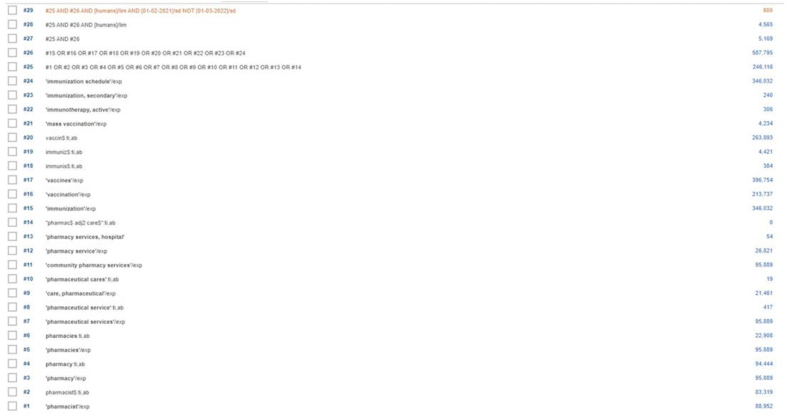

Search results – Embase

Search results – CENTRAL

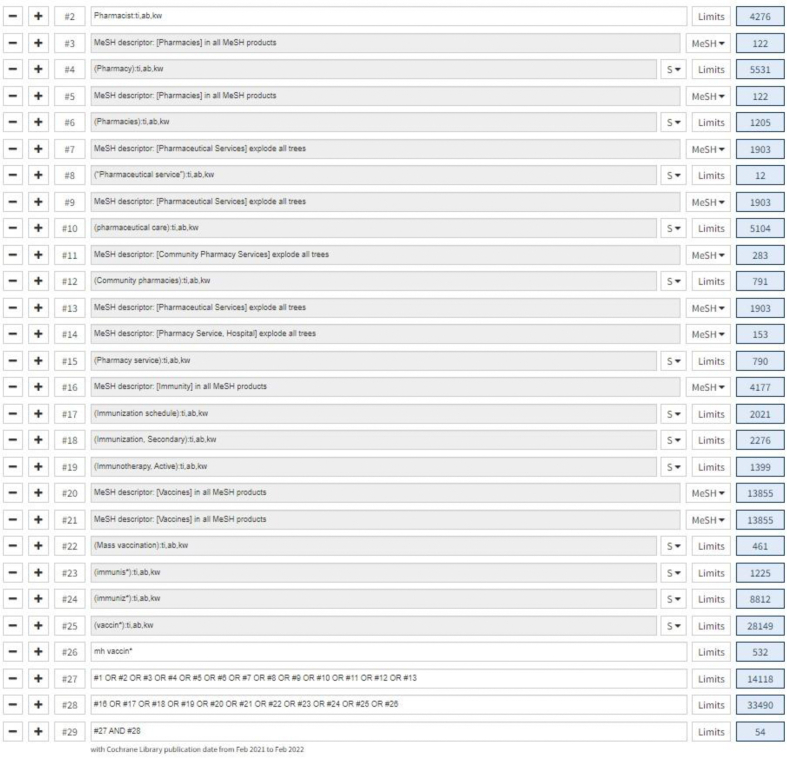

Updated search results Supplement XV: Updated search results Search results – MEDLINE from 01 Feb 2021 – 28 Feb 2022

Search results – EMBASE from 01 Feb 2021 – 28 Feb 2022

Search results – CENTRAL from 01 Feb 2021 – 28 Feb 2022

Supplement II: Risk of bias assessment for RCTs according to intention-to-treat analysis

Supplement III.

Risk of bias assessment for observational studies according to intention-to-treat analysis.

Supplement IV.

Summary plot of risk of bias assessment for observational studies according to intention-to-treat analysis.

Supplement V.

Forest plot of Impact of Pharmacist involvement on Immunization rate of influenza vaccine by pharmacist role.

Supplement VI.

Forest plot of Impact of Pharmacist involvement on Immunization rate of influenza vaccine by study setting.

Supplement VII.

Summary of meta-analyses of observational studies by pharmacist role

| Role of pharmacist | Primary analysis |

Sensitivity analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1- excluding critical ROB studies |

#2 - excluding studies with both role |

|||||

| # studies | (RR [95%CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95%CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95%CI]; I2) | |

| All vaccines | ||||||

| Immunizer | 9 | (2.17 [1.71, 2.75]; 97.7%) | 6 | (2.19 [1.47, 3.26]; 98%) | 3 | (2.74 [1.77,4.23]; 97%) |

| Advocator | 17 | (2.01 [1.66, 2.44]; 99%) | 12 | (1.86 [1.50, 2.31]; 96.8%) | 11 | (2.15 [1.65, 2.81]; 97.1%) |

| Both | 6 | (1.78 [1.47,2.15]; 92.4%) | 3 | (1.73 [1.02,2.93]; 93.7%) | - | - |

| Influenza vaccines | ||||||

| Immunizer | 3 | (2.15 [1.16, 4.02]; 98.2%) | 2 | (2.76 [1.39, 5.49]; 98.5%) | 2 | (2.76 [1.39,5.49]; 98.5%) |

| Advocator | 6 | (2.02 [1.37, 2.98]; 92.1%) | 3 | (1.97 [1.03, 3.75]; 91.5%) | 5 | (2.37 [1.45, 3.82]; 93.2%) |

| Both | 1 | NA | 0 | NA | - | - |

Note: ROB, risk of bias; NA, insufficient data

Supplement VIII.

Summary of meta-analyses of observational studies by study setting

| Study setting | Primary analysis |

Sensitivity analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1- excluding critical ROB studies |

#2 - excluding studies with both role |

|||||

| # studies | (RR [95%CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95%CI]; I2) | # studies | (RR [95%CI]; I2) | |

| All vaccines | ||||||

| Community pharmacy | 6 | (2.97 [1.92, 4.58]; 98.4%) | 4 | (2.91 [2.18, 3.88]; 88.6%) | 3 | (2.79 [1.93, 4.03]; 92.4%) |

| Hospital/Medical center | 9 | (2.04 [1.53, 2.72]; 97.7%) | 7 | (1.75 [1.31, 2.35]; 97.6%) | 8 | (2.37 [1.67, 3.36]; 97.6%) |

| Clinic | 4 | (1.67 [1.21, 2.31]; 89.2%) | 4 | (1.67 [1.21, 2.31]; 89.2%) | 3 | (1.89 [1.33, 2.68]; 89.9%) |

| Other | 1 | NA | 1 | NA | 0 | NA |

| Influenza vaccines | ||||||

| Community pharmacy | 2 | (3.32 [2.11, 5.22]];65.5% | 2 | (3.32 [2.11, 5.22]];65.5% | 2 | (3.32 [2.11, 5.22]];65.5% |

| Hospital/Medical center | 3 | (3.84 [1.66, 8.88]; 91.3%) | 1 | NA | 3 | (3.84 [1.66, 8.88]; 91.3%) |

| Clinic | 2 | (1.53 [0.95, 2.46]; 95.6%) | 2 | (1.53 [0.95, 2.46]; 95.6%) | 2 | (1.53 [0.95, 2.46]; 95.6%) |

| Other | 1 | NA | 1 | NA | 0 | NA |

Note: ROB, risk of bias; NA, insufficient data

Supplement IX.

Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) for analyses of observational studies

| Outcome | Pharmacist role | Illustrative comparative risks1 |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Number of participants (No. of studies) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed risk1 Usual care |

Corresponding risk1 Pharmacist intervention |

|||||

| Primary analysis by pharmacist role at any setting for all vaccines | ||||||

| Immunization rate of all vaccines | Immunizer | 16 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 | 2.17 (1.71, 2.75) |

2,676,385 (9 studies) |

⨁⨁◯◯2LOW |

| Advocator | 15 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 | 2.01 (1.66, 2.44) |

2,643,474 (17 studies) |

⨁⨁◯◯2LOW | |

| Subgroup analysis by pharmacist role at any setting for influenza vaccine | ||||||

| Immunization rate of influenza vaccines | Immunizer | 104 per 1000 | 223 per 1000 | 2.15 (1.16, 4.02) |

5,561 (3 studies) |

⨁⨁◯◯2LOW |

| Advocator | 22 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 | 2.02 (1.37, 2.98) |

11,331 (6 studies) |

⨁◯◯◯3VERY LOW | |

Note: CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

The basis for the assumed risk (eg. the median or mean of control group risk across studies). The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention.

Low quality evidence is due to inconsistency (high heterogeneity) and large effect size.

Very low quality evidence is due to inconsistency (high heterogeneity & risk of bias).

Supplement X: List of references of observational studies

-

1.

Baucom A, Brizendine C, Fugit A, Dennis C. Evaluation of a Pharmacy-to-Dose Pneumococcal Vaccination Protocol at an Academic Medical Center. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2019;53(4):364-70.

-

2.

Bedwick BW, Garofoli GK, Elswick BM. Assessment of targeted automated messages on herpes zoster immunization numbers in an independent community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(3S):S293-S7.e1.

-

3.

Bourdet SV, Kelley M, Rublein J, Williams DM. Effect of a pharmacist-managed program of pneumococcal and influenza immunization on vaccination rates among adult inpatients. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2003;60(17):1767-71.

-

4.

Bryan AR, Liu Y, Kuehl PG. Advocating zoster vaccination in a community pharmacy through use of personal selling. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53(1):70-7.

-

5.

Buchan SA, Rosella LC, Finkelstein M, Juurlink D, Isenor J, Marra F, et al. Impact of pharmacist administration of influenza vaccines on uptake in Canada. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2017;189(4):E146-E52.

-

6.

Carthon CE, Hall RC, Maxwell PR, Crowther BR. Impact of a pharmacist-led vaccine recommendation program for pediatric kidney transplant candidates. Pediatric transplantation. 2017;21(6).

-

7.

Cebollero J, Walton SM, Cavendish L, Quairoli K, Cwiak C, Kottke MJ. Evaluation of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination After Pharmacist-Led Intervention: A Pilot Project in an Ambulatory Clinic at a Large Academic Urban Medical Center. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2020;135(3):313-21.

-

8.

Chou TIF, Lash DB, Malcolm B, Yousify L, Quach JY, Dong S, et al. Effects of a student pharmacist consultation on patient knowledge and attitudes about vaccines. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(2):130-7.

-

9.

Clarke C, Wall GC, Soltis DA. An introductory pharmacy practice experience to improve pertussis immunization rates in mothers of newborns. American journal of pharmaceutical education. 2013;77(2):29.

-

10.

Coley KC, Gessler C, McGivney M, Richardson R, DeJames J, Berenbrok LA. Increasing adult vaccinations at a regional supermarket chain pharmacy: A multi-site demonstration project. Vaccine. 2020;38(24):4044-9.

-

11.

Coyle CM, Currie BP. Improving the rates of inpatient pneumococcal vaccination: impact of standing orders versus computerized reminders to physicians. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2004;25(11):904-7.

-

12.

Deslandes R, Evans A, Baker S, Hodson K, Mantzourani E, Price K, et al. Community pharmacists at the heart of public health: A longitudinal evaluation of the community pharmacy influenza vaccination service. Research in social & administrative pharmacy : RSAP. 2020;16(4):497-502.

-

13.

Dodds E, Drew RH, May DB, Gouveia-Pisano JA, Washam JB, Rumley K, et al. Impact of a Pharmacy Student-Based Inpatient Pneumococcal Vaccination Program. American journal of pharmaceutical education. 2001;65:258-60.

-

14.

Drozd EM, Miller L, Johnsrud M. Impact of Pharmacist Immunization Authority on Seasonal Influenza Immunization Rates Across States. Clinical therapeutics. 2017;39(8):1563-80.e17.

-

15.

Durham MJ, Goad JA, Neinstein LS, Lou M. A comparison of pharmacist travel-health specialists' versus primary care providers' recommendations for travel-related medications, vaccinations, and patient compliance in a college health setting. Journal of travel medicine. 2011;18(1):20-5.

-

16.

Edwards HD, Webb Rd Fau - Scheid DC, Scheid Dc Fau - Britton ML, Britton Ml Fau - Armor BL, Armor BL. A pharmacist visit improves diabetes standards in a patient-centered medical home (PCMH). Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(6):529-34.

-

17.

Fera T, Bluml BM, Ellis WM. Diabetes Ten City Challenge: final economic and clinical results. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(3):383-91.

-

18.

Fletcher M, Rankin S, Sarangarm P. The Effect of Pharmacy-Driven Education on the Amount of Appropriately Administered Tetanus Vaccines in the Emergency Department. Hospital Pharmacy. 2019;54(1):45-50.

-

19.

Fuchs J. The provision of pharmaceutical advice improves patient vaccination status. Pharmacy Practice. 2006;4(4):163-7.

-

20.

Garrett DG, Bluml BM. Patient self-management program for diabetes: first-year clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45(2):130-7.

-

21.

Gattis S, Yildirim I, Shane AL, Serluco S, McCracken C, Liverman R. Impact of Pharmacy-Initiated Interventions on Influenza Vaccination Rates in Pediatric Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2019;8(6):525-30.

-

22.

Grabenstein JD. Daily versus single-day offering of influenza vaccine in community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(5):628-31.

-

23.

Grabenstein JD, Guess HA, Hartzema AG, Koch GG, Konrad TR. Effect of vaccination by community pharmacists among adult prescription recipients. Medical care. 2001;39(4):340-8.

-

24.

Haas-Gehres A, Sebastian S, Lamberjack K. Impact of pharmacist integration in a pediatric primary care clinic on vaccination errors: a retrospective review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(4):415-8.

-

25.

Hagemann TM, Johnson EJ, Conway SE. Influenza vaccination by pharmacists in a health sciences center: A 3-year experience. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(3):295-301.

-

26.

Henry T, Smith S, Hicho M. Treat to goal: Impact of clinical pharmacist referral service primarily in diabetes management. Hospital Pharmacy. 2013;48(8):656-61.

-

27.

Hill JD, Anderegg SV, Couldry RJ. Development of a pharmacy technician-driven program to improve vaccination rates at an academic medical center. Hospital Pharmacy. 2017;52(9):617-22.

-

28.

Hohmeier KC, Randolph DD, Smith CT, Hagemann TM. A multimodal approach to improving human papillomavirus vaccination in a community pharmacy setting. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4: 2050312116682128.

-

29.

Isenor JE, Alia TA, Killen JL, Billard BA, Halperin BA, Slayter KL, et al. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on influenza vaccination coverage in Nova Scotia, Canada. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2016;12(5):1225-8.

-

30.

Isenor JE, O'Reilly BA, Bowles SK. Evaluation of the impact of immunization policies, including the addition of pharmacists as immunizers, on influenza vaccination coverage in Nova Scotia, Canada: 2006 to 2016. BMC public health. 2018;18(1):787.

-

31.

Lam AY, Chung Y. Establishing an on-site influenza vaccination service in an assisted-living facility. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(6):758-63.

-

32.

Lehman N, Koenigsfeld CF, Wall GC, Renner C, Hahn D, Sheesley B, et al. A collaborative program to increase adult pneumococcal vaccination rates among a high-risk patient population receiving care at urgent care clinics. American journal of infection control. 2018;46(8):952-3.

-

33.

Lin JL, Bacci JL, Reynolds MJ, Li Y, Firebaugh RG, Odegard PS. Comparison of two training methods in community pharmacy: Project VACCINATE. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2018;58(4S):S94-S100.e3.

-

34.

Loughlin SM, Mortazavi A, Garey KW, Rice GK, Birtcher KK. Pharmacist-managed vaccination program increased influenza vaccination rates in cardiovascular patients enrolled in a secondary prevention lipid clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(5):729-33.

-

35.

McConeghy KW, Wing C. A national examination of pharmacy-based immunization statutes and their association with influenza vaccinations and preventive health. Vaccine. 2016;34(30):3463-8.

-

36.

McCord AD. Clinical Impact of a Pharmacist-Managed Diabetes Mellitus Drug Therapy Management Service. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2006;26(2):248-53.

-

37.

McDerby NC, Kosari S, Bail KS, Shield AJ, MacLeod T, Peterson GM, et al. Pharmacist-led influenza vaccination services in residential aged care homes: A pilot study. Australasian journal on ageing. 2019;38(2):132-5.

-

38.

McGinnis JM, Jones R, Hillis C, Kokus H, Thomas H, Thomas J, et al. A pneumococcal pneumonia and influenza vaccination quality improvement program for women receiving chemotherapy for gynecologic cancers at a major tertiary cancer Centre. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161(1):236-243.

-

39.

Meier-Stephenson V, McNeil S, Kew A, Sweetapple J, Thompson K, Slayter K. Effects of a pharmacy-driven perisplenectomy vaccination program on vaccination rates and adherence to guidelines. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2014;67(4):262-7.

-

40.

Mills B, Fensterheim L, Taitel M, Cannon A. Pharmacist-led Tdap vaccination of close contacts of neonates in a women's hospital. Vaccine. 2014;32(4):521-5.

-

41.

Noped J, Schomberg R. Implementing an inpatient pharmacy-based pneumococcal vaccination program. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2001;58:1852-5.

-

42.

Padilla ME, Jiang S, Barner JC, Rivera JO. A comparison of national immunization rates to immunization rates of Latino diabetic patients receiving clinical pharmacist interventions in a federally qualified community health centre (FQHC). Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 2014;5(3):175-80.

-

43.

Padiyara RS, D'Souza Jj Fau - Rihani RS, Rihani RS. Clinical pharmacist intervention and the proportion of diabetes patients attaining prevention objectives in a multispecialty medical group. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(6):456-62.

-

44.

Page A, Harrison A, Nadpara P, Goode JVR. Pharmacist impact on pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination rates in patients with diabetes in a national grocery chain pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(3 Supplement):S51.

-

45.

Percy JN, Crain J, Rein L, Hohmeier KC. The impact of a pharmacist-extender training program to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates within a community chain pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(1):39-46.

-

46.

Pickren E, Crane B. Impact on CDC guideline compliance after incorporating pharmacy in a pneumococcal vaccination screening process. Hospital Pharmacy. 2016;51(11):894-900.

-

47.

Pizzi LT, Prioli KM, Fields Harris L, Cannon-Dang E, Marthol-Clark M, Alcusky M, et al. Knowledge, Activation, and Costs of the Pharmacists' Pneumonia Prevention Program (PPPP): A Novel Senior Center Model to Promote Vaccination. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2018;52(5):446-53.

-

48.

Porter AM, Fulco PP. Impact of a pharmacist-driven recombinant zoster vaccine administration program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(2):e136-e139.

-

49.

Rihtarchik L, Murphy CV, Porter K, Mostafavifar L. Utilizing pharmacy intervention in asplenic patients to improve vaccination rates. Research in social & administrative pharmacy : RSAP. 2018;14(4):367-71.

-

50.

Robison SG. Impact of pharmacists providing immunizations on adolescent influenza immunization. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56(4):446-9.

-

51.

Robke JT, Woods M, Heitz S. Pharmacist impact on pneumococcal vaccination rates through incorporation of immunization assessment into critical pathways in an acute care setting. 2002;37(10):1050-4.

-

52.

Scherrer LA, Benns MV, Frick C, Pentecost K, Broughton-Miller K, Wojcik J, et al. Impact of a pharmacist-led intervention on post-splenectomy vaccination adherence among trauma patients. Trauma (United Kingdom). 2020;22(4):273-7.

-

53.

Singhal PK, Zhang D. Costs of adult vaccination in medical settings and pharmacies: an observational study. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy. 2014;20(9):930-6.

-

54.

Sivaraman V, Wise KA, Cotton W, Barbar-Smiley F, AlAhmed O, MacDonald D, et al. Previsit Planning Improves Pneumococcal Vaccination Rates in Childhood-Onset SLE. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1).

-

55.

Skledar SJ, Hess MM, Ervin KA, Gross PR, Nowalk MP, Carter H, Zimmerman RK, et al. Designing a hospital-based pneumococcal vaccination program. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(14):1471-6.

-

56.

Skledar SJ, McKaveney TP, Sokos DR, Ervin KA, Coldren M, Hynicka L, Lavsa S, et al. Role of student pharmacist interns in hospital-based standing orders pneumococcal vaccination program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2007;47(3):404-9.

-

57.

Skoy ET, Kelsch M, Hall K, Choi BJ, Carson P. Increasing adult immunization rates in a rural state through targeted pharmacist education. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(6):e301-e6.

-

58.

Stewart-Lynch AL, Albert B, Bryan C, Graveno M, Roper RI, Schneider S, et al. The impact of clinical pharmacy services on pneumococcal vaccine frequency and appropriateness in a family medicine clinic. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2020;60(2):362-7.

-

59.

Steyer TE, Ragucci KR, Pearson WS, Mainous AG, 3rd. The role of pharmacists in the delivery of influenza vaccinations. Vaccine. 2004;22(8):1001-6.

-

60.

Taitel M, Cohen E Fau - Duncan I, Duncan I Fau - Pegus C, Pegus C. Pharmacists as providers: targeting pneumococcal vaccinations to high risk populations. 2011(1873-2518 (Electronic)).

-

61.

Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE, Cannon AE, Cohen ES. Improving pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccination uptake: expanding pharmacist privileges. The American journal of managed care. 2013;19(9):e309-13.

-

62.

Tong EY, Mitra B, Roman CP, Yip G, Olding S, Joyce C, et al. Improving influenza vaccination among hospitalised patients in General Medicine and Emergency Short Stay units - a pharmacist-led approach. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2018;48(3):231-5.

-

63.

Trogdon JG, Shafer PR, Shah PD, Calo WA. Are state laws granting pharmacists authority to vaccinate associated with HPV vaccination rates among adolescents? Vaccine. 2016;34(38):4514-9.

-

64.

Van Amburgh JA, Waite NM, Hobson EH, Migden H. Improved influenza vaccination rates in a rural population as a result of a pharmacist-managed immunization campaign. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(9):1115-22.

-

65.

Veltri KT, Ferguson-Myrthil N, Currie B. The STanding orders protocol (STOP): A pharmacy driven pneumococcal and influenza vaccination program. Hospital Pharmacy. 2009;44(10):874-80.

-

66.

Vondracek TG, Pham TP, Huycke MM. A hospital-based pharmacy intervention program for pneumococcal vaccination. Archives of internal medicine. 1998;158(14):1543-7.

-

67.

Wallgren S, Berry-Cabán CS, Bowers L. Impact of clinical pharmacist intervention on diabetes-related outcomes in a military treatment facility. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(3):353-7.

-

68.

Wang J, Ford LJ, Wingate LM, Uroza SF, Jaber N, Smith CT, et al. Effect of pharmacist intervention on herpes zoster vaccination in community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc 2013;53(1):46-53.

-

69.

Warner JG, Portlock J, Smith J, Rutter P. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination uptake using community pharmacies: experience from the Isle of Wight, England. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(6):362-7.

-

70.

Wise KA, Sebastian SJ, Haas-Gehres AC, Moore-Clingenpeel MD, Lamberjack KE. Pharmacist impact on pediatric vaccination errors and missed opportunities in the setting of clinical decision support. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(3):356-61.

-

71.

Abu-Rish EY, Barakat NA. The impact of pharmacist-led educational intervention on pneumococcal vaccine awareness and acceptance among elderly in Jordan. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2021;17(4):1181-1189. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1802973

-

72.

Bayraktar-Ekincioglu A, Kara E, Bahap M, Cankurtaran M, Demirkan K, Unal S. Does information by pharmacists convince the public to get vaccinated for pneumococcal disease and herpes zoster? Article in Press. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02778-x

-

73.

Gatwood J, Renfro C, Hagemann T, et al. Facilitating pneumococcal vaccination among high-risk adults: Impact of an assertive communication training program for community pharmacists. Article. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(5):572-580.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.04.011

-

74.

Giles ML, Khai K, Krishnaswamy S, et al. An evaluation of strategies to achieve greater than 90% coverage of maternal influenza and pertussis vaccines including an economic evaluation. Article. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021;21(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04248-9

-

75.

Hargrave K. Interprofessional Collaboration Improves Uptake of Flu Vaccines on a College Campus. Journal of Christian nursing. 2020;37(4):221-227. https://doi.org/10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000756

-

76.

Okuyan B, Ozcan V, Balta E, et al. The impact of community pharmacists on older adults in Turkey. Article. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(6):e83-e92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.06.009

-

77.

Schafer JJ, McRae J, Prioli KM, et al. Exploring beliefs about pneumococcal vaccination in a predominantly older African American population: the Pharmacists' Pneumonia Prevention Program (PPPP). Ethnicity & health. 2021;26(3):364-378. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1514450

-

78.